Abstract

Objective

Our objectives were to explore the changes in the level of interest in risk-sharing agreements (RSAs) in the EU during the last 15 years and the underlying reasons for these changes.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Embase. Articles identified were divided into ‘quantitative articles’ used to establish the level of interest and ‘qualitative articles’ used to identify the underlying trends in RSAs.

Results

The literature search retrieved 2144 scientific articles. Data were extracted from 238 articles. Of these, 100 contained quantitative data and 138 contained qualitative data. The pace of articles being published about RSAs grew significantly in 2015, which related to the increase in interest in and knowledge about RSAs. The underlying reasons for the fluctuations were condensed into four overall themes: (1) push for value-based pricing, (2) economic crisis and further push to contain costs, (3) criticism of RSAs in the real world, and (4) diversification of RSAs to fit the purpose.

Conclusion

The overall level of interest in RSAs in the EU has been increasing since 2000; therefore, articles reporting the number of RSAs implemented and case studies have been steadily growing as evidence is becoming more readily available. The number of qualitative articles reporting and discussing the underlying reasons for these changes in interest has largely fluctuated over the last 15 years. Despite these fluctuations, interest in RSAs remains high.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s41669-017-0044-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| There is a high level of interest in risk-sharing agreements between payers, regulatory agencies, and companies. |

| Underlying reasons for changes in the level of interest in risk-sharing agreements include (1) push for value-based pricing, (2) economic crisis and further push to contain costs, (3) criticism of RSAs in the real world, and (4) diversification of RSAs to fit the purpose. |

| Increased reporting on pricing and reimbursement practices has led to an improved understanding of risk-sharing agreements. |

Introduction

According to “Health at a Glance: Europe 2014” [1], the aging population and longer life expectancies will increase the burden on healthcare systems in the coming years. In addition, decreasing odds of success in clinical trials as well as new but expensive technologies have increased drug prices. The increasing cost of healthcare is a major problem for most countries in the EU as they have maintained near-universal healthcare coverage [1]. New and innovative approaches to pricing and reimbursement are needed if national healthcare payers are to be able to provide patients with access to new, innovative, and effective drugs while keeping within their limited budget [1–4].

Consequently, pharmaceutical manufacturers are being pressured to demonstrate real-world value for money beyond that of the three traditional criteria of drug regulators: quality, efficacy, and safety [5, 6]. Many countries are employing health technology assessment (HTA) agencies to evaluate on their behalf the real-world worth of new medicinal products [6]. However, the data available on the cost effectiveness of many new and innovative medicines, particularly in oncology, are severely lacking at the time of product launch [7]. This can create a significant level of uncertainty around a product’s performance in the real world, which in turn can cause delays in reimbursement decisions by HTA agencies, resulting in potential revenue loss by manufacturers [7]. Conversely, payers can potentially risk reimbursing expensive medicines that have questionable benefits, and this can direct resources away from patients.

To address this issue, national healthcare payers, HTA agencies, and the pharmaceutical industry found common ground in the form of formal arrangements. The aim has been to share the financial risks associated with new and innovative medicines when the value of a product is not fully observable at the time of its launch [7, 8]. These agreements have many names and come in various forms, but the one characteristic they all have in common is the potential to enable patient access to new medicines that otherwise would not be available at the time of product launch [9]. The most common names for these formal arrangements include risk-sharing agreements (RSAs), payment by results (PbRs), patient access schemes (PAS), or performance-based risk-sharing agreements (PBRSAs), and the overarching concept is managed entry agreements (MEAs) [7, 8, 10–13]. In this article, we use the term RSA to describe all of the above as it is the most often used in the literature [14]. Years of debate and lack of consensus appear to have impeded the progress of RSAs; however, today the term is accepted and well known in various sectors of the healthcare system [15].

Over the last 15 years, several articles have reported an increase in [12, 16–21] or discussed the implications of RSAs [7, 22]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no article has evaluated the number of articles about RSAs alongside the implications of their use to discuss the overall trends in RSA development. This article addresses this issue through a systematic literature review with an aim to (1) track interest and changes in RSAs in the EU over the last 15 years and (2) analyse the ‘how’ (the processes), the ‘who’ (the stakeholders) and the ‘why’ (the circumstances) that have contributed to these changes.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature search and divided selected articles into two groups: (1) quantitative articles to explore changes in the level of interest and (2) qualitative articles to explore the underlying reasons for the changes.

Literature Search

One author (TJP) performed an initial literature search to compose a list of searchable keywords. Grey literature from Google, Google Scholar, and the official websites of international organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR), and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) were used. The decision to focus on EU member states stemmed from the OECD’s yearly evaluation of EU member states and their healthcare spending rates and because European health authorities have more leverage than authorities in other countries to deny reimbursement based on cost-effectiveness studies [1, 14, 15].

The list of keywords and relevant databases were identified in a three-step process. A number of keywords used to define RSAs were identified through the above-mentioned initial literature review. Next, a list of databases was created that only searched for peer-reviewed articles. Keywords were then entered individually into each database to validate the choice of keyword and database. With all predefined filters set (see the “Appendix” for an example), the number of ‘hits’ was taken into consideration when selecting both the keywords and the databases. The following keywords and terms were retained and used in the search: patient access scheme, pharmaceutical risk sharing, risk sharing, risk sharing scheme, risk sharing agreement, managed entry agreement, payment by result, performance based risk sharing agreement, coverage with evidence development, and price volume agreement.

The following databases were searched for peer-reviewed literature: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Embase for all years leading up to January 2016. No publication date filter was used so older articles were not overlooked. The search was limited to English-language articles. Only agreements or schemes relating to pharmaceutical products were included; medical devices and diagnostic tools were excluded because pharmaceuticals require a higher level of evidence for reimbursement. The inclusion criteria specified that the title of the article included or alluded to at least one of the searched words and was about or relevant to the objective. The article had to be related to pharmaceutical products; be conducted or published in and/or about EU member states; and/or involve the sale of pharmaceutical products (i.e. reimbursement). The exclusion criteria included articles about non-EU member states (e.g. USA, Australia, Asia, Israel, and Africa), capitation (monetary allocation to doctors, physicians, nurses, and hospitals), vaccines, medical devices, diagnostic tools, hospital financial schemes, and/or pure financial schemes. Additional exclusion criteria included Medicaid or Medicare (as these pertain to the US health system), administrative work with and without physicians, and/or needles and syringes. Abstract screening was conducted by one author (TJP) using the same filtering criteria as used in the title screening and involved a more in-depth analysis of the article’s contents.

The same author categorized articles as either quantitative or qualitative research using criteria based on Creswell’s [23] description of quantitative and qualitative methods: (1) quantitative methods “involve the process of collecting, analyzing, interpreting, and writing the results of a study,” and (2) qualitative methods “are purposeful sampling, collection of open-ended data, analysis of text or pictures, representation of information in figures and tables, and personal interpretation of the findings.” A simplified explanation of the differences between these two approaches is that quantitative articles collect and analyse data in the form of numbers and qualitative articles collect and analyse data in the form of words [24]. Some articles were described as mixed method reviews as they incorporated both qualitative and quantitative research; these articles were categorized as quantitative research.

Data Extraction and Qualitative Analysis

For each peer-reviewed article that passed both levels of initial screening, two levels of data extraction were performed by one author (TJP). First, the summary information (i.e. authors, title, abstract, and article classification) was extracted for all articles into an evidence table. Second, key concepts, data (i.e. numerical values), and summaries of findings presented for all articles were extracted, forming the basis of the final evidence table. Information extracted from quantitative articles focused on the number and/or type of RSAs investigated or tracked and the country and specific years in which the RSAs took place. Information extracted from qualitative articles focused on the reasons for a shift towards value-based healthcare systems and the need to implement RSAs. Other key concepts included recommendations on how, when, and where RSAs were implemented, examples of both successful and failed RSA attempts, and other possible debates for or against their use. At this point, a synthesis, keeping close to the original findings of each study, was created and integrated into a whole, forming a draft summary.

The author TJP used a qualitative content analysis to identify recurrent themes and concepts retrieved from the draft summary. This process involved the use of inductive category development where themes and concepts were formed while summarizing and assessing the extracted information. These categories were deduced step by step within a feedback loop wherein the categories were revised, eventually filtering out the main points of analysis [24, 25]. Saturation was reached when the analysis of data showed recurring themes and no new insights. The combination of the report on healthcare expenditure rates from the OECD [1] and the time-related themes identified in the qualitative content analysis allowed for the possibility of a historical interpretation of the political and economic pressures that led to the increased interest in RSAs in the EU.

Results

Trends in the Level of Interest in Risk-Sharing Agreements (RSAs) Over Time

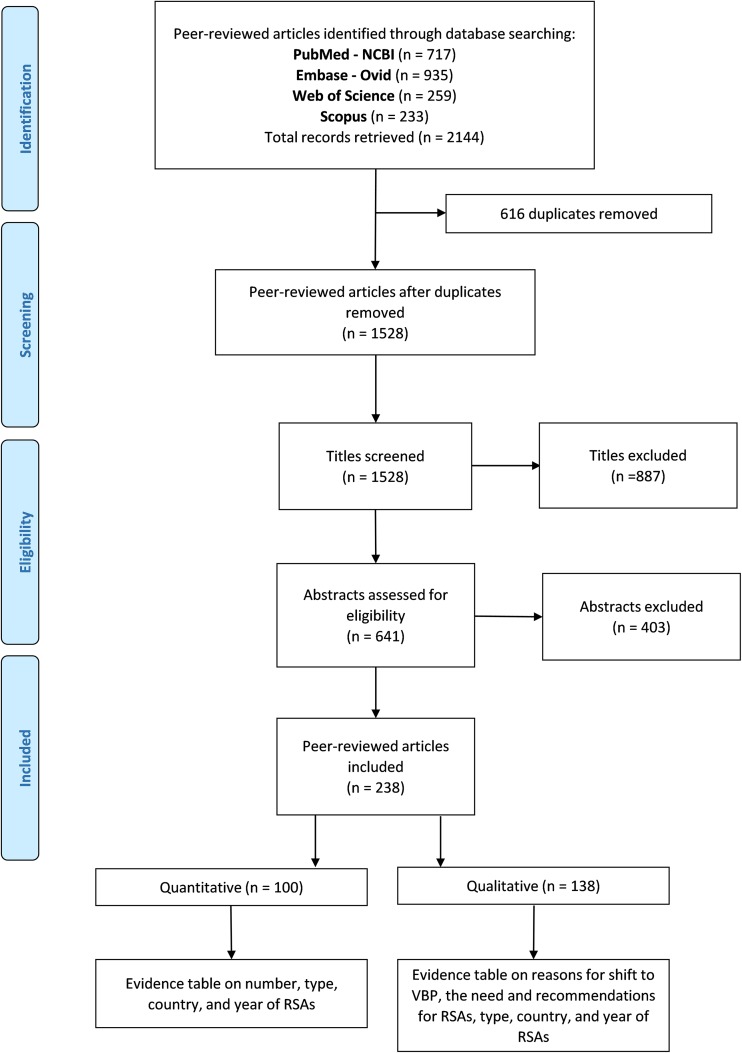

The systematic literature search retrieved 2144 scientific articles; 641 remained after title screening, and 238 remained after abstract review. Of these 238 articles, 100 contained quantitative data and 138 contained qualitative data (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of systematic literature search and data extraction using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses). RSA risk-sharing agreement, VBP value-based pricing

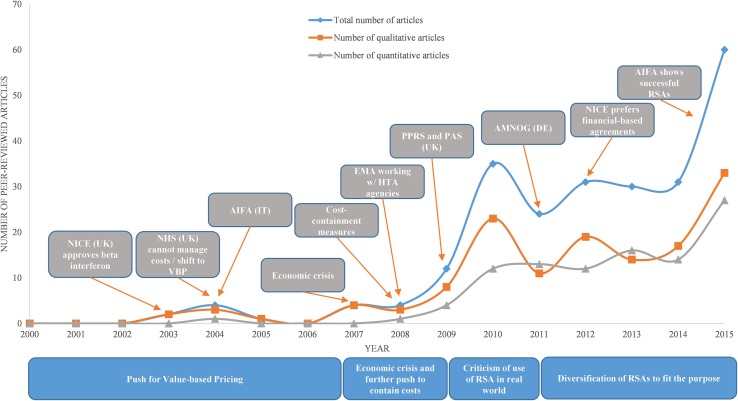

The number of articles found for each year in the systematic review was used to create Fig. 2, which illustrates how publication rates varied by year. The 100 quantitative articles were published at a steadily increasing rate between 2008 and 2015, and the 138 qualitative articles fluctuated in a succession of waves as of 2009, increasing in 2015. This quantitative analysis helped identify an increasing level of interest in RSAs in the last 15 years (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Trends in risk-sharing agreement peer-reviewed articles are shown divided into the number of total (blue diamond), qualitative (orange square), and quantitative (grey triangle) articles. Critical events for price negotiation in Europe are labelled in grey boxes and corresponding years are marked by orange arrows. The four overall themes and their corresponding timeframes are shown under the x axis in blue boxes. AIFA Italian Medicines Agency, AMNOG Pharmaceuticals Market Reorganization Act, DE Germany, EMA European Medicines Agency, NHS National Health Service, NICE National Institute for Care and Excellence, HTA health technology assessment, IT Italy, PAS patient access scheme, PBRSA performance-based risk sharing, PPRS Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme, RSA risk-sharing agreement, UK United Kingdom, VBP value-based pricing

Trends in Underlying Reasons for Change in Level of Interest Over Time

From the evidence table for all articles (see the Electronic Supplementary Material for the complete table; examples shown in Table 1), four overall time-related themes emerged from the qualitative analysis: (1) push for value-based pricing (VBP), (2) economic crisis and further push to contain costs, (3) criticism of RSAs in the real world, and (4) diversification of RSAs to fit the purpose.

Table 1.

Example summary of articles with key characteristics for inclusion in systematic review. Qualitative and quantitative articles are presented to exemplify the categorization of articles retrieved from the systematic literature search presented in Fig. 1

| References | Key findings from abstracts |

|---|---|

| Example of qualitative articles | |

| Claxton [30] | The report by the OFT on the UK PPRS recommends the reform of the current scheme, which is a combination of profit and price controls, to one where price is based on the health benefits offered by a pharmaceutical. On closer examination, some of the more commonly expressed concerns about these proposals do not seem to be well founded. In principle, the OFT’s recommendations may contribute to allocative and dynamic efficiency in the NHS. However, some dangers exist, and the details of how it will be implemented are crucial. For example, VBP with an inappropriate threshold for cost effectiveness, or an inappropriate pricing structure, could lead to technologies being adopted at prices where their benefits, in terms of health outcome, do not offset the health displaced elsewhere in the NHS, a situation in which the NHS is damaged rather than improved by innovation. A failure to account for uncertainty and the value of evidence in negotiating prices and coverage could also undermine the evidence base for future NHS practice. Whatever view is taken, the OFT report will inevitably shape the scope of future policy debates about value, guidance, price, and innovation |

| Thornton [32] | The OFT report into the PPRS called for reform of the scheme, replacing existing profit and price controls with a system of VBP. The report argued that VBP would be much more effective than the current PPRS both at providing value for money for the NHS and giving pharmaceutical companies the right incentives to invest in drugs in the future. The report has sparked a widespread debate about drug pricing in the UK and has been controversial in some quarters. However, some of the more negative responses are based on fundamental misconceptions about the OFT recommendations. In particular, contrary to some claims, the recommended system would provide strong incentives for incremental innovation and the right balance of rewards for first-in-class and follow-on products. Nor, as is sometimes argued, would VBP have an adverse effect on investment in the UK. Certainly, real challenges lie ahead if VBP is to be implemented. These concern the definition of value, particularly where patient benefits differ significantly by subgroup or indication, and the level of resource required to implement VBP. The OFT report contains proposals for addressing each of these areas. Perhaps the most difficult challenge is the political one: securing acceptance for a reform package that would create winners and losers among pharmaceutical companies according to their success in producing valuable drugs. Ultimately, however, only a scheme that does precisely this can hope to meet the needs of patients, the NHS and innovative companies in the long run |

| Towse [31] | The OFT report on the UK PPRS recommends that when the current 5-year PPRS expires in 2010 it be replaced with VBP, which involves pre-launch centralized government price setting based on a cost-per-QALY threshold plus periodic ex post reviews. I examine the validity of the OFTs criticisms of the existing PPRS, review its proposals and propose an alternative way forward. I conclude that PPRS has performed well as a procurement bargain between industry and the UK government. However, it does not incentivize efficient relative prices. That is not its job. I identify a number of problems with the OFT proposals. I recommend that key elements of a reformed UK pharmaceutical environment for 2010 should include an expanded role for HTA but with companies retaining freedom to set prices at launch; HTA use targeted via a contingent value-of-information approach; a retained backstop PPRS, perhaps moving to an RPI-X type control; the use of RSAs and non-linear pricing arrangements; measures to ensure more effective therapeutic switching at local level; and measures to improve the take up of cost-effective treatments |

| Ando et al. [73] | The increasing use of risk-sharing in reimbursement decisions across major markets necessitates that key stakeholders understand the role of this concept in shaping drug development and regulatory decision making. The objective of this research was to examine global trends in RSAs since 1990 to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current and future impact of this fast-evolving concept. Primary research was conducted through 50 in-depth 45-minute telephone interviews in native languages. Subjects were carefully selected and represented payers, government agencies, and HTA organizations in nine markets (five in Europe; Australia, New Zealand, USA, and Canada) to understand their assessment of the role RSAs have or have not played in their respective markets, and whether they will do so in the future. This was complemented with secondary research of reimbursement decisions around the world based on a newly created database of RSAs around the world. In some countries such as the UK and Italy, for certain therapeutic areas such as oncology, these agreements almost act as a substitute for the normal reimbursement process, but primary research indicates that this practice faces significant resistance at many layers. Still, many other countries are seeking to understand the potential applicability of RSAs to their own market. Also, RSAs are being examined for their potential in several other therapeutic areas. While population- and patient-level agreements remain the most popular, we conclude that health outcomes-based arrangements are significantly on the rise, with 27 having been identified through the study in the markets that were studied, the majority of which were signed since 2007. Just over half were signed for oncology therapeutics. Outcomes-based agreements are becoming an increasingly important consideration to include in pricing models across the traditional development pathway for new molecules |

| Towse and Garrison [22] | This article examines performance-based RSAs for pharmaceuticals from a theoretical economic perspective. We position these agreements as a form of coverage with evidence development. New performance-based risk sharing could produce a more efficient market equilibrium, achieved by adjustment of the price post-launch to reflect outcomes combined with a new approach to the post-launch costs of evidence collection. For this to happen, the party best able to manage or to bear specific risks must do so. Willingness to bear risk will depend not only on ability to manage it but also on the degree of risk aversion. We identify three related frameworks that provide relevant insights: value of information, real option theory and money-back guarantees. We identify four categories of risk sharing: budget impact, price discounting, outcomes uncertainty and subgroup uncertainty. We conclude that a value-of-information real option framework is likely to be the most helpful approach for understanding the costs and benefits of risk sharing. A number of factors are likely to be crucial in determining whether performance-based agreements or RSAs are efficient and likely to become more important in the future: (1) the cost and practicality of post-launch evidence collection relative to pre-launch; (2) the feasibility of CED without a pre-agreed contract as to how the evidence will be used to adjust price, revenues or use, in which uncertainty around the pay-off to additional research will reduce the incentive for the manufacturer to collect the information; (3) the difficulty of writing and policing RSAs; (4) the degree of risk aversion (and therefore opportunity to trade) on the part of payers and manufacturers; and (5) the extent of transferability of data from one country setting to another to support CED in a risk-sharing framework. There is no doubt that in principle risk sharing can provide manufacturers and payers additional real options that increase overall efficiency. Given the lack of empirical evidence on the success of schemes already agreed and on the issues we set out above, it is too early to tell whether the recent surge of interest in these arrangements is likely to be a trend or only a fad |

| Example of quantitative articles | |

| Carlson et al. [12] | To identify and characterize publicly available cases and related trends for performance-based schemes, we performed a systematic review of performance-based schemes over the past 15 years (1996–2011) using publicly available databases and reports from colleagues and healthcare experts. These were categorized according to a previously published taxonomy of scheme types and assessed in terms of the underlying product and market attributes for each scheme. Macro-level trends were identified related to the timing of scheme adoption, countries involved, types of schemes, and product and market factors. Our search yielded in excess of 110 schemes. From this set, we identified 58 schemes that included a CED component, 25 that included a conditional treatment continuation component, 35 that included a performance-linked reimbursement component, and 37 that included a patient-level financial utilization component. Each type of scheme addresses fundamental uncertainties that exist when products enter the market. There has been a continued upward trend in terms of total schemes adopted per year and the number of countries with performance-based schemes in place. Despite the continued enthusiasm, challenges persist, including those related to (1) the cost and burden of implementation; (2) the need for consistent processes for scheme development, data collection, reporting, and evaluation; and (3) negotiating follow-on agreements after scheme initiation. Furthermore, the challenges faced differ by country, health system, and product. There is continued enthusiasm in many countries for using performance-based schemes for new medical products. Given the interest to date and the potential to meet the goals of interested stakeholders, these schemes may become a common element in healthcare coverage and reimbursement. However, significant challenges persist, and future studies are needed regarding the attitudes and perceptions of various stakeholders as well as evaluating the results and experiences with the schemes implemented thus far |

| Ethgen [74] | Our objective was to define an operational modelling framework intended to help the design of PBRS schemes. A time-to-event endpoint is used as a performance criterion. Such survival endpoints are commonly used in clinical studies, notably in oncology where PBRS schemes are gaining momentum. The framework is based on an open population model with a monthly cycle and 3-year time horizon from launch (i.e. when enrolment into the PBRS scheme starts). Entry into the model (i.e. the progressive arrival of new patients into the PBRS scheme) is determined by market diffusion assumptions and is modelled using a logistic function. Exit from the model (i.e. patients experiencing the event or dying from any cause) is determined by survival curves from clinical/epidemiological studies and is modelled using a Weibull function. The model accommodates different treatment dosing schedules and performance levels (i.e. minimum survival times guaranteed). Multiple PBRS scenarios can be run and compared in terms of their operational and financial implications. Additionally, the effect of potential revisions of a PBRS scheme terms and conditions can also be examined as real-life information becomes available following scheme implementation (i.e. Bayesian updating). For example, assuming 1000 patients enrolled in a PBRS scheme, with a monthly dosing schedule and given diffusion (logistic alpha = 5.0; beta = 0.4) and survival (Weibull gamma = 0.7; k = 27.0) assumptions, the model predicts that 1937 (6970), 4050 (7861), and 9282 (4420) doses will be given to non-responding (responding) patients with 12, 18, and 24 months of minimum survival time guaranteed scenarios, respectively. This framework provides both payer and manufacturer with valuable insight into the operational and financial dimensions of the potential PBRS schemes they may contemplate as they negotiate patient access conditions. Both parties can better anticipate the implications of the schemes and better plan resources, logistics, and financial arrangements accordingly |

| Morel et al. [35] | National payers across Europe have been increasingly looking into innovative reimbursement approaches, MEAs, to balance the need to provide rapid access to potentially beneficial OMPs with the requirements to circumscribe uncertainty, obtain best value for money, or ensure affordability. This study aimed to identify, describe, and classify MEAs applied to OMPs by national payers and to analyse their practice in Europe. To identify and describe MEAs, national HTAs and reimbursement decisions on OMPs across seven European countries were reviewed and their main characteristics extracted. To fill data gaps and validate the accuracy of the extraction, collaboration was sought from national payers. To classify MEAs, a bespoke taxonomy was implemented. Identified MEAs were analysed and compared by focusing on five key themes, namely by describing the MEAs in relation to drug targets and therapeutic classes, geographical spread, type of MEA applied, declared rationale for setting-up of MEAs, and evolution over time. 42 MEAs for 26 OMPs, implemented between 2006 and 2012 and representing a variety of MEA designs, were identified. Italy had the highest number of schemes (n = 15), followed by the Netherlands (n = 10), England and Wales (n = 8), Sweden (n = 5), and Belgium (n = 4). No MEA was identified for France and Germany because data were unavailable. Antineoplastic agents were the primary targets of MEAs. 55% of the identified MEAs were performance-based RSAs; the other 45% were financial-based. Nine of these 26 OMPs were subject to MEAs in two or three different countries, resulting in 24 MEAs. 60% of identified MEAs focused on conditions with a prevalence of <1 per 10,000. This study confirmed that a variety of MEAs were increasingly used by European payers to manage aspects of uncertainty associated with the introduction of OMPs in the healthcare system, and which may be of a clinical, utilization, or budgetary nature. Whether differences in the use of MEAs reflect differences in how ‘uncertainty’ and ‘value’ are perceived across healthcare systems remains unclear |

| Ferrario and Kanavos [75] | MEAs are a set of instruments used to reduce the impact of uncertainty and high prices when introducing new medicines. This study develops a conceptual framework for these agreements and tests it by exploring variations in their implementation in Belgium, England, the Netherlands, and Sweden and over time as well as their governance structures. Using publicly available data from HTA agencies and survey data from the European Medicines Information Network, a database of agreements implemented between 2003 and 2012 was developed. A review of governance structures was also undertaken. In December 2012 there were 133 active MEAs for different medicine indications across the four countries. These corresponded to 110 unique medicine indications. Over time, there has been a steady growth in the number of agreements implemented, with the highest number in the Netherlands in 2012. The number of new agreements introduced each year followed a different pattern. In Belgium and England it increased over time, whereas it decreased in the Netherlands and fluctuated in Sweden. Only 18 (16%) of the unique medicine–indication pairs identified were part of an agreement in two or more countries. England uses mainly discounts and free doses to influence prices. The Netherlands and Sweden have focused more on addressing uncertainties through CED and, Sweden has focussed on monitoring use and compliance with restrictions through registries. Belgium uses a combination of the above. Despite similar reasons being cited for MEA implementation, only in a minority of cases have countries implemented an agreement for the same medicine indication; when they do, a different agreement type is often implemented. Differences in governance across countries partly explain such variations. However, more research is needed to understand whether, for example, risk perception and/or notion of what constitutes a high price differs between these countries |

| Tettamanti et al. [56] | MAAs are vital to access the Italian market. MAAs, monitored by an AIFA registry, are divided into outcome-based (cost-sharing) and non-outcome-based (risk-sharing and payment-by-results) agreements. The objective is to understand the MAA adoption, evolution, and utilization variability among therapeutic areas. The desk-based research was carried out by integrating different information sources, from AIFA and Gazzette Ufficiali to regional HTA studies. Data were gathered for all the 82 products/indications belonging to an open registry signed up to a MAA since January 2006 up until April 2015. 59% of products/indications have an outcome-based MAA, 33% a non-outcome-based and 1% both. One-third of outcome-based and one-quarter of non-outcome-based MAAs have an additional volume agreement or spending cap. A maximum peak of 30 products/indications with MAA was recorded in 2014, compared with an annual average of 8. In 2006–2007, cost-sharing MAAs were predominantly adopted; in 2008–2011, outcome-based MAAs were negotiated in approximately half of the cases (57%), becoming, since 2012, the preferred conditional reimbursement scheme (78%). Focusing on antineoplastic products, leukaemia drugs have only non-outcome-based agreements; lymphoma, melanoma, breast, colorectal, and ovary cancer drugs have a prevalence of outcome-based agreements, whereas renal cell and lung cancer drugs have both. Throughout the years, there has been an increase in the adoption of MAAs as they are considered a valuable strategy to manage payer budget impact and drug clinical benefit uncertainties. Since their introduction, the choice of MAA schemes utilized has witnessed an evolution, with an increasing preference for outcome-based MAAs, though often applied together with additional financial saving schemes. Due to the model adoption variability of MAAs within the therapeutic areas, the study of their structure plays a key role in accessing the Italian market |

AIFA Italian Medicines Agency, CED coverage with evidence development, HTA health technology assessment, MAA market access entry agreements, MEA managed entry agreement, NHS National Health Service, OFT Office of Fair Trading, OMP orphan medicinal product, PBRS performance-based risk-sharing, PPRS pharmaceutical price regulation scheme, QALY quality-adjusted life-year, RPI-X, RSA risk-sharing agreement, VBP value-based pricing

Push for Value-Based Pricing

Our results suggest increasing demands from national healthcare payers in the early 2000s to have pharmaceuticals priced according to the benefits they offered as a means to help allocate limited resources more efficiently as healthcare costs increased [26]. This approach, known as VBP, should balance the price of a new drug with the true value to patients [26]. As early as 2001, the idea of outcomes-based guarantees was beginning to be considered a viable alternative pricing and reimbursement strategy, and not merely a theory [26]. The initial idea of outcomes-based guarantees was a scheme whereby if a drug failed to meet predefined expectations, then the pharmaceutical company would have to refund the costs of the drug to the health authorities [26]. In theory, it was assumed this would encourage pharmaceutical companies to promote proper utilization by physicians, thereby ensuring that health authorities did not waste resources on treatments that did not meet expectations in the real world [26]. We found no peer-reviewed articles that provided empirical evidence on RSAs between 2000 and 2003, possibly because the discourses at the time were theoretical and therefore lacking quantitative data.

At the same time, awareness of outcomes-based schemes was growing as the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) approved beta interferon for multiple sclerosis (MS) where the base cost for the therapy ranged from £42,000 to £90,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained [27, 28]. This approval introduced one of the first novel RSAs in healthcare. However, Sudlow and Counsell [29] raised doubt in their article “Problems with UK government’s risk-sharing schemes for assessing drugs for multiple sclerosis” as beta interferon was approved without evidence of cost effectiveness. This explains the spike in the number of qualitative articles around 2003 and 2004 (Fig. 2).

The number of published articles dropped from 2005 to 2006 (Fig. 2) as data on the UK beta interferon RSA for MS were still lacking. The impact of the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) in 2004 as the national authority responsible for drug regulation in Italy is discussed further in the following sections. In 2007 (Fig. 2) the number of qualitative articles spiked as results of the UK’s RSA were anticipated. At that time, many articles were questioning whether such schemes were actually necessary [30–32].

Economic Crisis and Further Push to Contain Costs

At the end of 2007 and the beginning of 2008, RSAs and HTAs were beginning to emerge in the UK. At this point, the push for value-based healthcare and pricing had substantial backing as healthcare resources were significantly limited and budgets were cut. HTA agencies throughout Europe were tasked with measuring the cost effectiveness of new medicinal products before national healthcare payers would reimburse the product [6]. Pharmaceutical companies were now required to not only prove quality, efficacy, and safety but also to provide significant data on the cost effectiveness and budget impact of their new products, more commonly known as the ‘fourth hurdle’ [6]. The change of power from regulators to payers became even more important in 2008.

One result of the economic crisis was that many countries quickly introduced a wide variety of cost-containment strategies to help curb pharmaceutical spending [1]. These cost-containment strategies were more reactive than proactive responses to the crisis and aimed to reduce the initial cost of new pharmaceuticals [1]. Cost containment was attempted by introducing international reference pricing (IRP), price cuts, compulsory rebates, the promotion of generics, increased co-payments, a more centralized public procurement system, and, lastly, a reduction in coverage by excluding certain pharmaceuticals from reimbursement [1]. In essence, the economic crisis of 2008 helped catalyse the implementation of VBP. One example of this was the new Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) that was passed in the UK, which formally introduced PAS as part of its legal framework in 2009 and was an important shift in the UK’s pricing and reimbursement framework [33]. The UK pushed its NHS to consider the social value of medical treatments in an attempt to solve the problem of inequity and to promote innovation and a focus on underrepresented patient groups [34]. Similarly, Germany approved the Pharmaceuticals Market Reorganization Act (AMNOG) in 2011 whereby an early benefit assessment became mandatory to obtain reimbursement. This can be viewed as a formal move to VBP [35]. The policy shifts in the pricing and reimbursement practices of these two countries helped signal the end of the era of free pricing in some of Europe’s largest markets [36].

All these pressures on the healthcare budget forced payers to discuss how to properly balance costly medications with the population’s needs while simultaneously making coverage decisions while uncertain of the outcomes [37]. Furthermore, the evaluation of cost effectiveness with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) and/or QALYs of all new drug applicants was a costly and time-consuming task. As a remedy, national payers introduced HTA agencies to act as an intermediary and make recommendations on their behalf [30, 38].

HTA agencies became more important as authors such as McCabe et al. [4], Lucas et al. [39], and Chawla et al. [40] discussed how manufacturers increased their production of drugs that surpassed the acceptable cost-effectiveness measurements (e.g. cost per QALY or ICER) even though the main reasoning behind rejection by NICE was a drug with an ICER >£30,000 per QALY. Chawla et al. [40] reported that HTA agencies usually have two options to reach an agreement about a drug’s price and reimbursement status: (1) to reduce the initial cost of the treatment (financial discount) to meet the cost-effectiveness ratio and (2) to enter into a PBRSA (outcomes-based) to overcome any uncertainty the payer may have regarding the product’s real-world performance. Although Chawla et al. [40] suggested that RSAs do not guarantee a positive recommendation by HTA agencies, other authors agreed that the increase in the use of RSAs, especially for new oncology therapies, appeared to indicate that reimbursement was still very possible as long as both parties share the financial risks while the company has time to demonstrate the value of their drug [41–45].

Criticism of the Use of RSAs in the Real World

The shift to VBP came with its own set of problems. According to McCabe et al. [4], payers were at risk of jeopardizing their own healthcare system if medicines deemed cost effective during product launch were in fact not as cost effective in the real world. The authors raised this concern because of a lack of standardization for cost-effectiveness thresholds between and within different healthcare systems [4]. The inappropriate use of predefined thresholds such as ICERs or QALYs resulted in appraisals that were not always transparent or robust [4, 30, 38, 46]. Cohen et al. [47] questioned the use of ICERs and/or QALYs as reimbursement parameters because cost effectiveness only evaluates overall gains in health. Conversely, a budget-impact analysis with coverage with evidence development (CED) takes into account the healthcare budget as a whole; therefore, Cohen et al. [48] suggested this was more important than a cost-effectiveness analysis in reimbursement decision making.

As shown in Fig. 2, the sudden spike in qualitative articles published in 2009 and 2010 was the result of attempts by numerous authors to characterize and define RSAs. For example, McCabe et al. [11] proposed a framework for defining and evaluating risk-sharing schemes. In addition, Carlson et al. [18] attempted to categorize and examine PBRSAs by performing a review using public search databases. Their search yielded 14 performance-linked reimbursement schemes, ten conditional treatment continuation schemes, and 34 CED schemes; 36 of the 53 PBRSAs took place in the EU [18].

Confidence in the viability of PBRSAs was waning as there were still not enough concrete examples of successful schemes to fundamentally alter reimbursement policies [15, 46]. In 2010, Towse and Garrison [22] and Towse [49] acknowledged the lack of empirical evidence for successful RSAs and tried to define RSAs based on previous definitions. In 2011, the number of qualitative articles published dropped substantially. For this period, the most that could be said is that enthusiasm for the use of RSAs in many countries continued [12], as the number of quantitative articles being published grew steadily.

Diversification of RSAs to Fit the Purpose

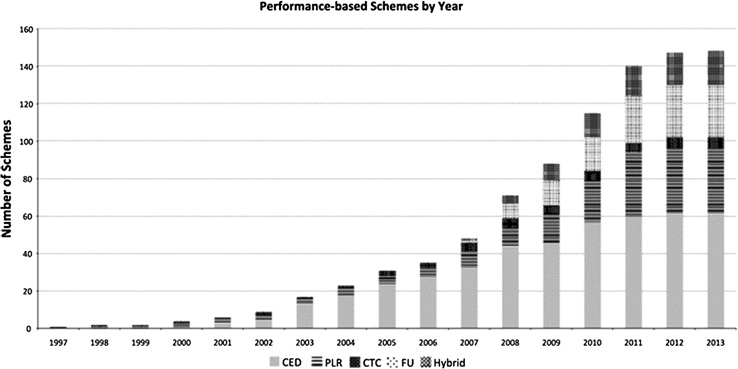

As of 2013, there were 148 identified PBRSAs, with a majority implemented between 2007 and 2011 [18]. As shown in Fig. 3 [18], the rate at which new RSAs were being implemented levelled out. Although the number of drugs with RSAs attached to them plateaued in 2012–2013, the majority of the new schemes were financial based, demonstrating a shift away from PBRSAs to minimize administrative burden [16–18].

Fig. 3.

Number of performance-based arrangements by year. Hybrid arrangements included the following: PLR|CTC: 2; PLR|FU: 1; PLR|CTC|FU: 12; CED|PLR: 2; CED|PLR|FU: 1. CED coverage with evidence development, CTC conditional treatment continuation, FU financial/utilization, PLR performance-linked reimbursement

Figure obtained from Carlson et al. [18]

According to Spoors et al. [17] and Pritchett et al. [50], it was clear that difficulties with the implementation and evaluation of PBRSAs, mostly in the UK, had shifted the focus to the more simplified financial-based RSAs. As an example of this, Briceno and Seoane-Vazquez [51] reviewed 207 NICE drug appraisals between September 2001 and September 2014 and determined that more than 45% of the appraisals published after 2010 included a confidential discount from the company to the NHS. This study highlighted that most high-cost drugs achieved a positive evaluation from NICE only if a simple discount was offered through a PAS [51, 52]. Although the UK primarily preferred discounts, PBRSAs were also successful. Sumra and Walters [53] reported on one such case in their article “A long term analysis of the clinical and cost effectiveness of glatiramer acetate from the UK multiple sclerosis risk sharing scheme.” This study involved the creation of a model for the clinical and cost effectiveness of glatiramer acetate (GA) using 6 years’ worth of data from the UK Multiple Sclerosis Risk-Sharing Scheme and a 20-year time horizon [53]. Based on their model, the authors concluded that the long-term efficacy and cost effectiveness of GA was greater than estimated during the planning of the RSA [53]. Giovannoni et al. [54] conducted a follow-up review and reported that this positive review allowed for the price to increase following the agreed upon amount at the start of the RSA 6 years prior. In light of successful PBRSAs such as this, Antonanzas et al. [55] determined that financial-based RSAs were preferred by payers when non-responding patients bore a small impact on the overall health budget but—when the cost was high—a PBRSA was preferred only if there was a low monitoring burden.

In Italy, RSAs became a standard procedure to access the Italian Market, and a recent study by Tettamanti et al. [56], the AIFA, and local resources assessed 82 therapies from 2006 to 2015. More than half of the therapies (59%) had a PBRSA, 33% were financial-based, and 1% used both schemes [56]. According to the data, PBRSAs slowly replaced financial-based RSAs over the years and constituted 78% of the total schemes [56]. The authors concluded that one reason for the change to PBRSAs was that the AIFA relied heavily on their extensive online patient-monitoring registries [50]. The AIFA monitoring registries allow for the continuous evaluation of pharmaceuticals in clinical practice and may in fact allow for quicker access to medicines and promotion of innovation at affordable prices [57]. Fasci et al. [58] presented an example of this in their article “Conditional Agreements for Innovative Therapies in Italy: The Case of Pirfenidone” when an RSA was put in place for pirfenidone in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis to gain reimbursement in 2013. By the time of price renegotiation, new data from phase III clinical trials and clinical practice were used to support the cost–benefit profile of pirfenidone [58]. According to this article, the evidence allowed the AIFA to overcome their previous uncertainties about the benefits of the drug and to remove the RSA while still covering the reimbursement costs [58].

Eastern Europe has also seen an increase in the number of published articles pertaining to their experiences with RSAs. Similar to the UK’s position on the adequate use of RSAs, a systematic literature review and expert analysis by Kolasa et al. [59] determined that PBRSAs were better suited for real-world application when dealing with uncertainties surrounding cost effectiveness, and financial-based RSAs were deemed more appropriate for budgeting and cost containment. Since cost-effectiveness and budget-impact analyses have become a requirement in most healthcare systems for setting the reimbursement of highly innovative drugs, Zizalova et al. [60] in the Czech Republic recently evaluated whether or not these costs matched those in the real world. They concluded that estimated costs were exceeded by 31–332% in five cases [60]. In six other cases, real costs did not achieve the estimations, running from 12 to 91% under the estimated costs. This study concluded that cost estimations for highly innovative drugs, although required in budget-impact analysis, did not contribute to a reasonable decision and had no real practical impact [60]. In Hungary, an analysis on the cost of treatment with new antiviral therapies for hepatitis C virus (HCV) by Kocsis et al. [61] was submitted to the HTA agency, which found that the introduction of these new drugs placed a financial strain on payers. As such, RSAs appear to be a promising solution for balancing payer uncertainty with the market access for new medicines in Eastern Europe [61, 62].

As many healthcare systems faced budget constraints and pressures by the year 2015, difficulties in making choices about what treatments to fund remained. According to Focsa [63], there is a willingness to pay a fair price for new drugs and the benefits they potentially can offer, but many current healthcare systems do not have the necessary infrastructure and evaluation processes. Patient monitoring has the potential to pave the way for accurate RSAs that directly link patient benefits with the cost of the treatment [63]. Dranitsaris et al. [64] concluded that VBP and RSAs could allow for earlier access to new treatments, improved transparency in pricing, the inclusion of multiple stakeholders, the recognition of highly innovative therapies, and a more predictable return on investments for manufacturers.

Discussion

To address the uncertainty surrounding RSAs, our study identified four time-related themes that explain the underlying reasons for the fluctuating levels of interest in RSAs over the past 15 years.

The growing interest in the use of RSAs among pharmaceutical companies and healthcare institutions in the EU over the past 15 years has emphasized the knowledge gap in the literature between what is publicly known and what is actually practiced, partially due to a lack of transparency from both parties [7, 22]. As a result, empirical evidence and validated success stories have been lacking in past years, and this has led to substantial debates about the sustainability of alternative pricing and reimbursement processes [7, 22]. However, details of and results from RSAs that were originally not publically available are now beginning to emerge [52, 65], enabling this study.

This study shows that, in the early 2000s, predominantly qualitative articles were being published because evidence for the number of RSAs implemented was essentially non-existent as no RSA scheme had been introduced at the time. Our study identified that initially, in 2000, only a few authors and healthcare institutions were discussing the use of RSAs in the EU, although a lack of articles published in this time span could have been the result of delays in the publication process. Nonetheless, it was evident that the increased need for alternative pricing and reimbursement strategies for market access has led to a significant increase in interest in RSAs. However, with this increased level of interest, our study has identified valid arguments and questions surrounding their use by both advocates and opponents of RSAs.

Our study shows that, after the economic crisis in 2007–2008, both the discussion and the implementation of RSAs increased significantly. As a result, the number of RSAs increased as more evidence was collected and presented as quantitative articles. In addition, fluctuations were seen in the number of qualitative articles published as the viability, budget impact, and sustainability of RSAs was discussed and debated. In the following years, a substantial number of both qualitative and quantitative peer-reviewed articles were published, providing invaluable data and information about how many RSAs were being put in place and the results of some older schemes. These articles also reaffirmed the issues being dealt with by national healthcare payers as pharmaceutical expenditure continued to increase significantly across many OECD countries [66]. Several articles have concluded there is no ‘one size fits all’ or perfect method of risk sharing, and it should only be used when the standard conditions of access are hindered by uncertainty about cost effectiveness [2, 5, 46]. Additional studies have shown that special considerations must be made as to the appropriateness of an RSA, its objectives, and whether or not staff and IT systems are available to support the administrative burden [2, 5, 46].

We identified several countries that have largely influenced policies surrounding RSA use. These include the UK, Italy, France, Germany, and—more recently—Eastern Europe. We would like to note that the UK has played a very important role as it was one of the first countries to implement an RSA and has maintained very detailed records. In addition, RSAs have been implemented in many countries in the EU in accordance with each countries’ own evaluation, governance, reporting, and evidence-collection practices [50]. As such, many countries have had different results and outcomes when implementing RSAs, and manufacturers must consider each country and their implementation processes as key indicators when deciding on the use of RSAs [50]. However, differences in HTA assessment criteria have led to a noticeable difference in drug benefit evaluations, recommendations, and overall access to several EU markets for each drug [67].

Although RSAs continue to emerge in many EU countries, Neumann et al. [14], Carlson et al. [15, 68], and Towse and Garrison [15] have discussed and identified some of the most notable barriers to their implementation as being (1) transaction and administrative costs; (2) limitations to online tracking systems; (3) identifying and agreeing on scheme details such as clinical endpoints, and price negotiations, etc.; (4) IRP; and (5) the lack of trust between payers, manufacturers, and healthcare providers.

Crinson [69] researched a combination of these barriers in one of the first case studies on the results of an RSA conducted in 2004 and proposed that the NHS was unsuccessful in its attempt to control the cost of beta interferon. Suggested reasons for this were the clinical needs of the patients, the prescribing activities of the doctors, and even the pharmaceutical company’s reluctance to lower its profit margin [69]. By March 2003, fewer patients than planned had entered the RSA scheme and not the thousands needed before November 2004 [70]. Many of the initial problems were delays in setting up the proper infrastructure for the RSA, securing promised funding, and a lack of specialist doctors and nurses to run the clinics [70]. However, these delays were to be expected with such a new and innovative scheme and needed to be overcome in the ensuing years [70].

Although RSAs play an important role in the collection of real-world data, improved patient tracking and monitoring technology may be required for the efficient use of risk sharing in a performance-based model. However, the limitations of digital tracking systems are becoming less of an issue in some countries, as well as for manufacturers, as they are increasing their monitoring registries and implementing new and improved tracking systems to keep pace with modern healthcare needs [71].

RSAs are now used as a means to circumnavigate cost-effectiveness barriers and IRP, when in fact HTA agencies should be viewed as business partners instead of as barriers or hurdles to overcome. Alternative pricing and reimbursement strategies such as RSAs may be the way forward as traditional pricing and reimbursement methods are no longer viable. All EU member states except for the UK and Sweden apply a form of IRP because VBP is more complicated [72]. However, IRP offers payers a means of pricing a pharmaceutical that is not in line with optimal welfare-maximizing pricing [72]. Both manufacturers and payers are now engaged in RSAs as they are trying to find payment models where the real price will differ from the list price. [72]. An RSA or confidential discount to payers can lower the cost of a product without changing the global list price, meaning that a negative impact on a company’s revenue could be avoided [68]. As an example, the PBRSA for bortezomib in the UK allows the list price to be unchanged, while the NHS can be refunded for non-responding patients [68]. This refund allows the net price per unit of drug to be less than the price listed [68]. Ultimately, it is predicted that IRP will cease to exist as the demand for VBP is increasing where payers and HTA agencies are requiring more evidence to make reimbursement decisions [68, 72].

Our review found that RSAs are continuing to emerge as many countries are engaged in new pricing and reimbursement strategies, although barriers to RSAs have been extensively documented [71]. RSAs for high-priced specialty drugs have a place in the future as more personalized medicines and better technology for identifying patient responses are being developed. RSAs have evolved and transformed immensely since their original conception and implementation in the early 2000s. It is assumed they will be primarily financial-based schemes in the coming years in the EU, but a transition back to performance-based schemes could occur in the near future. Technology for patient tracking and monitoring is improving and may match the needs of both the national healthcare payers and the pharmaceutical industry. Conversely, RSAs may no longer be viable as pharmaceutical companies become better at creating and gathering data on the value of their product. In doing so, they will build strong cases, lowering the chances of rejection by HTA agencies. A clear understanding of factors influencing the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of and learning around RSAs are necessary for further implementation strategies, while ongoing evaluation of RSAs is essential and needs to be reported in peer-reviewed articles.

Despite obtaining valuable data about the current use and perception of RSAs, there were limitations to this research. The systematic review may not have found all relevant sources pertaining to RSAs because, before a standardized definition and taxonomy were established, RSAs had various names that are no longer used, and many countries used their own terminology in their own language. Non-English articles were excluded because of language limitations among the people conducting the research. In addition, article publication dates are not always related to the exact year the content was written about because of publication time requirements. This may also be responsible for the lack of published articles in the years 2000–2003. Another reason for the lack of information lies in the fact that the overall process of pricing and reimbursement is classified and not transparent in many countries, and therefore it is difficult to obtain detailed reports and procedures to not only replicate but also to learn from. The number of peer-reviewed articles being published each year may not completely reflect the level of interest in RSAs because this can be considered single channel reporting and does not reflect all channels of literature. The level of interest in RSAs may vary between manufacturers and payers as they are not directly represented by peer-reviewed articles. In spite of these limitations, we feel that the depth and breadth of this study (based on valuable data) makes a considerable contribution to our knowledge of the field.

Conclusion

Information gathered in this systematic review indicates that the current level of interest in RSAs in the EU is high and has been increasing since 2000. Therefore, the number of quantitative articles reporting the number of RSAs implemented and case studies has been growing steadily as evidence is becoming more readily available. The number of qualitative articles reporting and discussing the underlying reasons for these changes in interest has generally fluctuated over the last 15 years. Despite these fluctuations, the overall level of interest in RSAs remains high and continues to grow.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Search strategy for PubMed-NCBI

((((((((“patient access scheme”[All Fields] OR ((“pharmacy”[MeSH Terms] OR “pharmacy”[All Fields] OR “pharmaceutical”[All Fields] OR “dosage forms”[MeSH Terms] OR (“dosage”[All Fields] AND “forms”[All Fields]) OR “dosage forms”[All Fields]) AND (“risk”[MeSH Terms] OR “risk”[All Fields]) AND sharing[All Fields])) OR “risk sharing scheme”[All Fields]) OR “risk sharing agreement”[All Fields]) OR “managed entry agreement”[All Fields]) OR “risk sharing”[All Fields]) OR “payment by result”[All Fields]) OR “coverage with evidence development”[All Fields]) OR (performance[All Fields] AND based[All Fields] AND (“risk”[MeSH Terms] OR “risk”[All Fields]) AND sharing[All Fields] AND agreement[All Fields])) OR “price volume agreement”[All Fields] AND ((hasabstract[text] AND “loattrfull text”[sb]) AND English[lang])

Filters: Abstract, Full text, English.

Author’s contributions

All authors (TJP, JMT, and THL) contributed to the design of the study, review of the study search protocol, analysis and interpretation of the results, and writing and review of the manuscript. TJP prepared the search protocol, performed the database searches and all screening, analysed the data, and prepared the draft of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Data availability statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Funding

No funding was provided for the completion of this study.

Conflicts of interest

TJP, JMT, and THL have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s41669-017-0044-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.OECD/EU . Health at a Glance: Europe 2014. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamski J, Godman B, Ofierska-Sujkowska G, Osinska B, Herholz H, Wendykowska K, et al. Risk sharing arrangements for pharmaceuticals: potential considerations and recommendations for European payers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:153. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duerden M, Gogna N, Godman B, Eden K, Mallinson M, Sullivan N. Current National Initiatives and Policies to Control Drug Costs in Europe: UK Perspective. J Ambul Care Manag. 2004;27(2):132–138. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200404000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCabe CJ, Bergmann L, Bosanquet N, Ellis M, Enzmann H, von Euler M, et al. Market and patient access to new oncology products in Europe: a current, multidisciplinary perspective. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(3):403–412. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cano-Chancel A, Long M, Sparrowhawk K. Risk sharing: what’s at risk and what’s being shared. Value Health. 2010;13(3):A95. doi: 10.1016/S1098-3015(10)72454-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor RS, Drummond MF, Salkeld G, Sullivan SD. Inclusion of cost effectiveness in licensing requirements of new drugs: the fourth hurdle. BMJ. 2004;329(7472):972–975. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7472.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrison LP, Jr, Towse A, Briggs A, De Pouvourville G, Grueger J, Mohr PE, et al. Performance-based risk-sharing arrangements—good practices for design, implementation, and evaluation: report of the ISPOR good practices for performance-based risk-sharing arrangements task force. Value Health. 2013;16(5):703–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook JP, Vernon JA, Manning R. Pharmaceutical risk-sharing agreements. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(7):551–556. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russo P, Mennini FS, Siviero PD, Rasi G. Time to market and patient access to new oncology products in Italy: a multistep pathway from European context to regional health care providers. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(10):2081–2087. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Pouvourville G. Risk-sharing agreements for innovative drugs: a new solution to old problems? Eur J Health Econ. 2006;7(3):155–157. doi: 10.1007/s10198-006-0386-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCabe CJ, Stafinski T, Edlin R, Menon D, Behalf Banff AEDS. Access with evidence development schemes a framework for description and evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(2):143–152. doi: 10.2165/11530850-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlson JJ, Gries K, Sullivan SD, Garrison L. Current status and trends in performance-based schemes between health care payers and manufacturers. Value Health. 2011;14(7):A359–A360. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.08.696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klemp M, Fronsdal KB, Facey K. What principles should govern the use of managed entry agreements? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27(1):77–83. doi: 10.1017/S0266462310001297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann PJ, Chambers JD, Simon F, Meckley LM. Risk-sharing arrangements that link payment for drugs to health outcomes are proving hard to implement. Health Aff. 2011;30(12):2329–2337. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson JJ, Sullivan SD, Garrison LP, Neumann PJ, Veenstra DL. Linking payment and health outcomes: a systematic review and taxonomy of performance-based health outcomes agreements between health care payers and manufacturers. Blackwell Publishing Inc.; 2009. http://www.valueinhealthjournal.com/article/S1098-3015(10)73513-0/abstract. Accessed 13 April 2015.

- 16.Ando G, Izmirlieva M, Honore AC. Global pharmaceutical risk-sharing agreement trends in 2011 and 2012: slowing down? Value Health. 2012;15(7):A322–A323. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spoors J, Brown C, Johnson N, Rietveld A. Patient access schemes in the new NHS. London: RJW and Partners; 2012. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed10&NEWS=N&AN=70915993. Accessed 13 April 2015.

- 18.Carlson JJ, Gries KS, Yeung K, Sullivan SD, Garrison LP., Jr Current status and trends in performance-based risk-sharing arrangements between healthcare payers and medical product manufacturers. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2014;12(3):231–238. doi: 10.1007/s40258-014-0093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navarria A, Drago V, Gozzo L, Longo L, Mansueto S, Pignataro G, et al. Do the current performance-based schemes in Italy really work? “Success fee”: a novel measure for cost-containment of drug expenditure. Value Health. 2014;18(1):131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morel T, Arickx F, Befrits G, Siviero PD, Van Der Meijden CMJ, Xoxi E, et al. Managed entry agreements and orphan drugs: a European comparative study (2006–2012) Value Health. 2013;16(7):A391. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrario A, Kanavos P. Managed entry agreements for pharmaceuticals: the European experience. London: London School of Economics and Political Science; 2013. p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Towse A, Garrison LP., Jr Can’t get no satisfaction? Will pay for performance help? Toward an economic framework for understanding performance-based risk-sharing agreements for innovative medical products. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(2):93–102. doi: 10.2165/11314080-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohlbacher F. The Use of qualitative content analysis in case study research. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2000;1(2):3–4.

- 26.Chapman S, Reeve E, Rajaratnam G, Neary R. Setting up an outcomes guarantee for pharmaceuticals: new approach to risk sharing in primary care. BMJ. 2003;326(7391):707–709. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7391.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayor S. Health department to fund interferon beta despite institute’s ruling. BMJ. 2001;323(7321):1087. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7321.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chilcott J, Miller DH, McCabe C, Tappenden P, Hagan A, Cooper NJ, et al. Modelling the cost effectiveness of interferon beta and glatiramer acetate in the management of multiple sclerosis. Commentary: Evaluating disease modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 2003;326(7388):522. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7388.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sudlow CLM, Counsell CE. Problems with UK government’s risk sharing scheme for assessing drugs for multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 2003;326(7385):388–392. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7385.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Claxton K. OFT, VBP: QED? Health Econ. 2007;16(6):545–558. doi: 10.1002/hec.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Towse A. If it ain’t broke, don’t price fix it: the OFT and the PPRS. Health Econ. 2007;16(7):653–665. doi: 10.1002/hec.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thornton S. Drug price reform in the UK: debunking the myths. Health Econ. 2007;16(10):9981–9992. doi: 10.1002/hec.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carroll SM, Wasiak R. Patient access schemes-the use of risk-sharing in the UK. Value in Health, 2009; 12(7):A286–A287.http://www.valueinhealthjournal.com/article/S1098-3015(10)74405-3/pdf. Accessed 13 April 2015.

- 34.Vídcárcel BGL. About Drugs: Therapeutic value, social value and market value Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2011; 109:2. https://insights.ovid.com/basic-clinical-pharmacologytoxicology/phtox/2011/10/003/drugs-therapeutic-value-social-market/21/00152251. Accessed 13 April 2015.

- 35.Morel T, Arickx F, Befrits G, Siviero P, van der Meijden C, Xoxi E, et al. Reconciling uncertainty of costs and outcomes with the need for access to orphan medicinal products: a comparative study of managed entry agreements across seven European countries. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:198. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hao Y. Health technology assessment and value-based pricing in Germany, the United Kingdom and France: recent developments and implications. Value Health. 2013;16(3):A261. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.03.1337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bishop D, Lexchin J. Politics and its intersection with coverage with evidence development: a qualitative analysis from expert interviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:88. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edlin R, Hall P, Wallner K, McCabe C. Sharing risk between payer and provider by leasing health technologies: an affordable and effective reimbursement strategy for innovative technologies? Value Health. 2014;17(4):438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucas F, Easley C, Jackson G. The usefulness and challenges of patient acess (risk sharing) schemes in the UK. Value Health. 2009;12(7):A243. doi: 10.1016/S1098-3015(10)74187-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chawla A, Oza A, Nellesen D, Brown J, Liepa AM, Price G, et al. Review of National Institute for Health And Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommendations for anti-cancer agents across multiple drug-indication combinations. Value Health. 2012;15(7):A436. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheema PK, Gavura S, Godman B, Yeung L, Trudeau ME. Global variations in reimbursement of new cancer therapeutics: Improving access through risk-sharing agreements. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28(15_suppl):6050. http://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/jco.2010.28.15_suppl.6050. Accessed 13 April 2015.

- 42.Costello S, Haynes S, Kusel J. Innovative pricing agreements in UK NICE submissions. Value Health. 2010;13(3):A96. doi: 10.1016/S1098-3015(10)72459-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barber R, Steeves S, Kusel J, Wilson T, Hamerslag L. How does the uncertainty around the expected ICER affect NICE decisions? Value Health. 2013;16(7):A481. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nijhuis T, Haigh J, Van Engen A. Confidential patient access schemes in the United Kingdom—do they affect prices in other markets? Value Health. 2013;16(7):A472–A473. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banerji L, Das S. Retrospective analysis of technology appraisals conducted by UK’s national institute for health and clinical excellence (NICE) in several cancer indications: higher evidence barriers for targeted therapies? Value Health. 2010;13(7):A245–A246. doi: 10.1016/S1098-3015(11)71874-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Espin J, Oliva J, Manuel Rodriguez-Barrios J. Innovative patient access schemes for the adoption of new technology: risk-sharing agreements. Gac Sanit. 2010;24(6):491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen JP, Stolk E, Niezen M. Role of budget impact in drug reimbursement decisions. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2008;33(2):225–247. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2007-054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen J, Looney W. What is the value of oncology medicines? Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(11):1160–1163. doi: 10.1038/nbt1110-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Towse A. Value based pricing, research and development, and patient access schemes. Will the United Kingdom get it right or wrong? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70(3):360–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03740.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pritchett L, Wiesinger A, Faria-Billinton E, Brown A, Murray G, Stoor L, et al. A review of guidelines and approaches to performance-based risk-sharing agreements across the UK, Italy and the Netherlands. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A568. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Briceno V, Seoane-Vazquez E. Analysis of nice drug technology appraisals (2001–September 2014) Value Health. 2015;18(3):A9. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.03.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walzer S, Droeschel D, Shannon R. Which risk share agreements are available and are those applied in global reimbursement decisions? Value Health. 2015;18(7):A568. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sumra M, Walters E. A long term analysis of the clinical and cost effectiveness of glatiramer acetate from the UK multiple sclerosis risk sharing scheme. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A765–A766. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.2512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giovannoni G, Brex P, Sumra M, Walters E, Schmierer K. Glatiramer acetate slows disability progression: results from a 6-year analysis of the UK Risk Sharing Scheme. Mult Scler. 2015;1:800–801. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Antonanzas F, Juarez-Castello C, Rodriguez-Ibeas R. Should health authorities offer risk-sharing contracts to pharmaceutical firms? A theoretical approach. Health Econ Policy Law. 2011;6(3):391–403. doi: 10.1017/S1744133111000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tettamanti A, Urbinati D, Noble M. Market access entry agreements in the Italian market between January 2006 and April 2015. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A552. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Montilla S, Xoxi E, Russo P, Cicchetti A, Pani L. Monitoring registries at Italian medicines agency: fostering access, guaranteeing sustainability. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2015;31(4):210–213. doi: 10.1017/S0266462315000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fasci A, Ferrario M, Ravasio R, Ena R, Angelini S, Giuliani G. Conditional agreements for innovative therapies in Italy: the case of pirfenidone. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A505. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kolasa K, Kalo Z, Hornby E. Pricing and reimbursement frameworks in Central Eastern Europe: a decision tool to support choices. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2015;15(1):145–155. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.898566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zizalova J, Rrahmaniova D, Svorcikova J, Vrubel F. The relation between real costs of drugs temporarily reimbursed in mode of coverage with evidence development and budget impact analysis submitted as a mandatory requirement of the application. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A567. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kocsis T, Papp E, Nemeth B, Juhasz J. The cost of treatment of the new antiviral therapies against the hepatitis C virus. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A689. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.2554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Petrov M, Hubenov P. Introduction of formal risk sharing agreements (RSA): a promising solution for sustainable and predictable pharmaceutical expenditures in Bulgaria. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A571–A572. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Focsa S. Can advances in health monitors lead to health being looked at as a commodity? Value Health. 2015;18(7):A730. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.2782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dranitsaris G, Dorward K, Owens RC, Schipper H. What is a new drug worth? An innovative model for performance-based pricing. Eur J Cancer Care. 2015;24(3):313–320. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Battye F. Payment by results in the UK: progress to date and future directions for evaluation. Evaluation. 2015;21(2):189–203. doi: 10.1177/1356389015577464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parkinson B, Sermet C, Clement F, Crausaz S, Godman B, Garner S, et al. Disinvestment and value-based purchasing strategies for pharmaceuticals: an international review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(9):905–924. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mycka J, Dellamano R, Lobb W, Dellamano L, Dalal N. Orphan drugs assessment in Germany: a comparison with other international HTA agencies. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A550–A551. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carlson JJ, Garrison LP, Jr, Sullivan SD. Paying for outcomes: innovative coverage and reimbursement schemes for pharmaceuticals. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):683–687. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Crinson I. The politics of regulation within the ‘modernized’ NHS: the case of beta interferon and the ‘cost-effective’ treatment of multiple sclerosis. Crit Soc Policy. 2004;24(1):30–49. doi: 10.1177/0261018304241002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Walley T. Neuropsychotherapeutics in the UK—what has been the impact of NICE on prescribing? CNS Drugs. 2004;18(1):1–12. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nazareth T, Ko JJ, Frois C, Carpenter S, Demean S, Wu EQ, et al. Outcomes-based pricing and reimbursement arrangements for pharmaceutical products in The US and EU-5: payer and manufacturer experience and outlook. Value Health. 2015;18(3):A100. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.03.586. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Persson U, Jonsson B. The end of the international reference pricing system? Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2016;14(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s40258-015-0182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ando G, Kowal S, Reinaud F. Payer roadblocks to risk-sharing agreements around the world: where, when and how? Value Health. 2010;13(7):A241. doi: 10.1016/S1098-3015(11)71855-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]