Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) epidemic—on a global scale—is a major and snowballing threat to public health, healthcare systems and economy, due to the cascade of pathologies triggered in a long-term manner after the DM manifestation. There are remarkable differences in the geographic disease spread and acceleration of an increasing DM prevalence recorded. Specifically, the highest initial prevalence of DM was recorded in the Eastern-Mediterranean region in 1980 followed by the highest acceleration of the epidemic characterised by 0.23% of an annual increase resulted in 2.3 times higher prevalence in the year 2014. In contrast, while the European region in 1980 demonstrated the second highest prevalence, the DM epidemic developments were kept much better under control compared to all other regions in the world. Although both non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors play a role in DM predisposition, cross-sectional investigations recently conducted amongst elderly individuals demonstrate that ageing as a non-modifiable risk factor is directly linked to unhealthy lifestyle as a well-acknowledged modifiable risk factor which, in turn, may strongly promote ageing process related to DM even in young populations. Consequently, specifically modifiable risk factors should receive a particular attention in the context of currently observed DM epidemic prognosed to expand significantly over 600 million of diabetes-diseased people by the year 2045. The article analyses demographic profiles of DM patient cohorts as well as the economic component of the DM-related crisis and provides prognosis for future scenarios on a global scale. The innovative approach by predictive diagnostics, targeted prevention and treatments tailored to the person in a suboptimal health condition (before clinical onset of the disease), as the medicine of the future is the most prominent option to reverse currently persisting disastrous trends in diabetes care. The key role of biomedical sciences in the future developments of diabetes care is discussed.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Epidemic, Comorbidities, Prevalence, Medical care, Costs, Economy, Health policy, Adolescence, Predictive preventive personalised medicine, Prognose, Pitfalls

Introduction

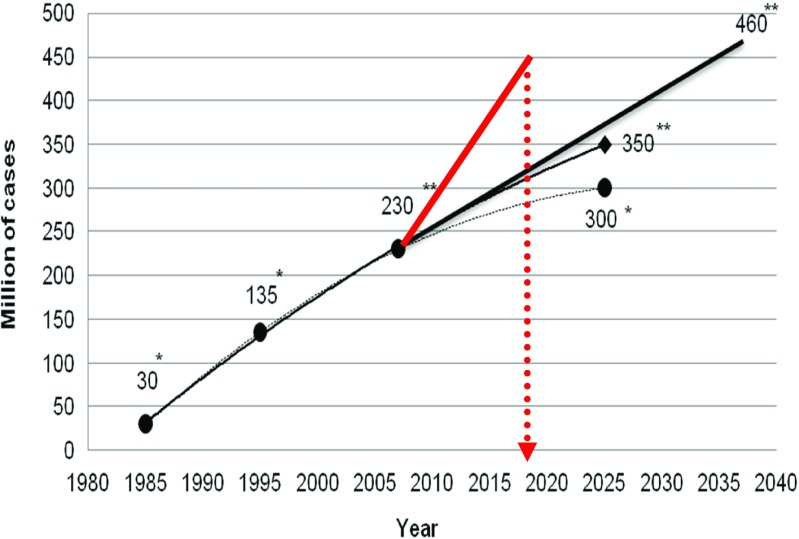

Diabetes mellitus is a widespread disease with a total number close to half a billion of patients currently registered worldwide. Indeed, the prognoses which have been made and corrected since 1980s are getting more and more pessimistic; however, actually registered diabetes prevalence sufficiently outnumbers any pessimistic prognosis provided earlier (see Fig. 1). Another problem is that the annual pool of new cases of individuals diseased on diabetes type 2 becomes enriched by patients in the teenager-age. Finally, particularly individuals diseased on diabetes early in life are particularly predisposed to a cascade of severe diabetes-related complications with poor outcomes such as cardiovarcular disease, several types of cancer and neurological disorders. Corresponding statistics and mechanisms which underlie the cascade of diabetes-related patholologies have been summarised elsewhere [1]. These actualities alert the scientific community, caregivers and society at large for predictive and preventive strategies urgently needed to be developed for and implemented in the diabetes care.

Fig. 1.

Permanently increasing prevalence of diabetes patients registered worldwide. With a single asterisk, the prognoses made in 1980s are marked. An expected increase in diabetes prevalence has been further updated in the early 2000s marked with a double asterisk clearly demonstrating that prognoses are getting more and more pessimistic; however, actually registered diabetes prevalence (marked in red colour) outnumbers any pessimistic prognosis provided earlier [1]

Retrospective analysis of the increasing prevalence of diabetes on a global scale

Retrospective analysis of the diabetes mellitus (DM) prevalence over the last 3.5 decades (years 1980–2014 have been considered) [2] demonstrates epidemic developments in all world regions without any exception (see Fig. 2). However, there are remarkable differences in the geographic prevalence and acceleration of the increasing rates recorded. Specifically, the highest initial prevalence of DM was recorded in the Eastern-Mediterranean region in 1980 followed by the highest acceleration of the epidemic characterised by 0.23% of an annual increase resulted in 2.3 times higher prevalence in the year 2014. Notable is that, although the African region originally demonstrated the lowest prevalence of DM, the acceleration of the DM epidemic was one of the strongest worldwide characterised by 0.12% of an annual increase resulted similarly to the leading Eastern-Mediterranean region in the 2.3 times higher prevalence in the year 2014. While originally the South-East Asian region demonstrated one of the lowest prevalences, in contrast, the acceleration was one of the highest characterised by 0.13% of an annual increase that resulted in the 2.1 times higher prevalence in the year 2014. Finally, while the European region in 1980 demonstrated the second highest prevalence, the DM epidemic developments evidently have been kept better under control compared to all other regions in the world. This achievement is clearly documented by the lowest rates of acceleration characterised by mild 0.06% of an annual increase resulting in the worldwide lowest increase of the prevalence (1.38 times) that actually corresponds to the second lowest DM prevalence in Europe amongst all other regions.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of DM on a global scale: retrospective comparative analysis in the period of time from the year 1980 till 2014 [3]

Main contributors to the DM predisposition and manifestation

DM is a multi-factorial disease, the manifestation of which is regulated by both genetic and epigenetic components. Several exogenous and endogenous risk factors are synergistically involved in the disease predisposition and clinical manifestation.

Non-modifiable risk factors

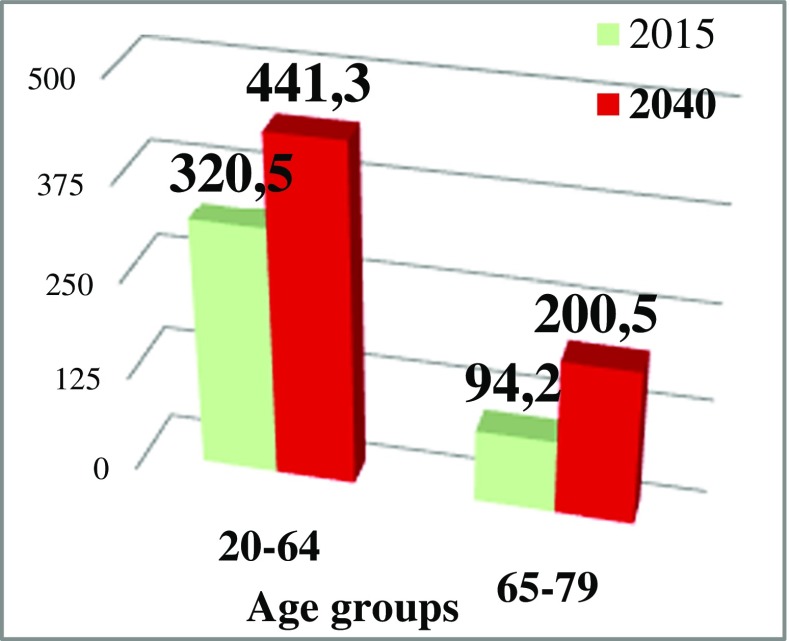

It is clearly documented that genetic predisposition plays an important role in the development of both diabetes type 1 and type 2 [4, 5]. Advanced age is another non-modifiable risk factor for diabetes manifestation. On the other hand, cross-sectional investigations recently conducted amongst elderly individuals demonstrate that ageing as a non-modifiable risk factor is directly linked to the unhealthy lifestyle as a modifiable risk factor [6] which, in turn, may strongly promote ageing processes and related diabetes onset even in young individuals as discussed in more detail below under “Modifiable risk factors”. Current versus prognosed (year 2040) distribution of diabetes-diseased people between two age-categories is presented in Fig. 3. Noteworthy, an increase (2.1 times) of DM patients aged 65–79 years is predicted to be significantly higher by the year 2040 compared to an increase (1.4 times) in the category 20–64 years old. Therefore, ageing and ageing-related processes as an eminent risk factor should be thoroughly analysed from the view point of its individualised prediction (early biologic versus chronologic ageing) followed by targeted preventive measures in the context of diabetes.

Fig. 3.

The entire DM patient’s pool (in million of patients) stratified by the age as registered in the year 2015; prognostic estimations for the corresponding age-groups are made for the year 2040 [7]

Modifiable risk factors

Sedentary lifestyle, imbalanced nutrition, overweight and obesity, and multifaceted stress factors are considered as the diabetes-related modifiable that means preventable risk factors. Contextually, current studies clearly demonstrate high relevance of individual factors synergistically contributing to the diabetes prevalence. In particular, following contributors have been recorded: irregular physical examination per year, physical inactivity, lack of attention paid to diet control, high-salt and high-fat diets, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, and regular alcohol uptake [6]. Obviously, the prevalence of the risk factor by being overweight depends not only on unhealthy lifestyle itself but also on the economic status of corresponding subgroups in the population. Specifically, the relationship between low versus high income status and overweight analysed demonstrates the highest rates of prevalence in upper middle- and high-income subpopulations—see Table 1. Noteworthy, corresponding rates differ sufficiently between men and women that should be taken into consideration for a proper stratification. In order to be implemented effectively, preventive measures should be targeted towards the most affected subgroups considering all relevant factors including economic status and demographic profiles analysed below.

Table 1.

Prevalence of overweight (BMI 25+) individuals aged over 18 years analysed in the year 2014 [2]

| Male % |

Female % |

Average in the adult population % |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-income | 15.4 | 26.9 | 21 |

| Lower middle-income | 24.2 | 31.3 | 28 |

| Upper middle-income | 43.3 | 42.7 | 43 |

| High-income | 61.5 | 52.2 | 57 |

From [2]

Demographic profiles

Patient stratification by the age demonstrated that currently, 77.3% of all diabetes patients correspond to the group 20–64 years of age, whereas the remaining 22.7% correspond to the age above 65 (see Fig. 3). Due to significant changes in demographic profiles reflected, for example, in a rapid ageing of the populations on a global scale, current patient’s age distribution is prognosed to be shifted towards elderly by the year 2040 becoming 68.8% to 31.2% for the younger and older groups, respectively [7].

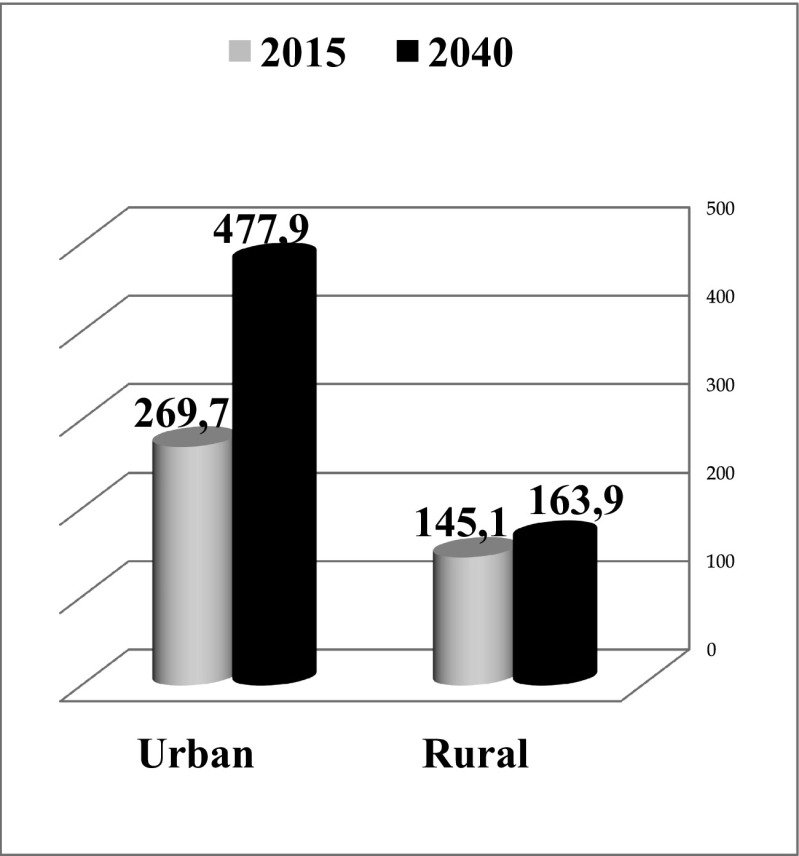

Significant changes in demographic profiles are expected to result in a shifted patients’ distribution between urban and rural areas as demonstrated in Fig. 4. Hence, the current distribution is 65% against 35% for the urban and rural areas, respectively. This difference is prognosed to grow up, further reaching the level over 74% of DM patients localised in the urban area increasing by 1.8 times versus 1.1 times in the rural area by the year 2040 compared to 2015.

Fig. 4.

DM patient distribution profiles (in million) between the urban and rural areas as documented for the year 2015 and prognosed for the year 2040 [7]

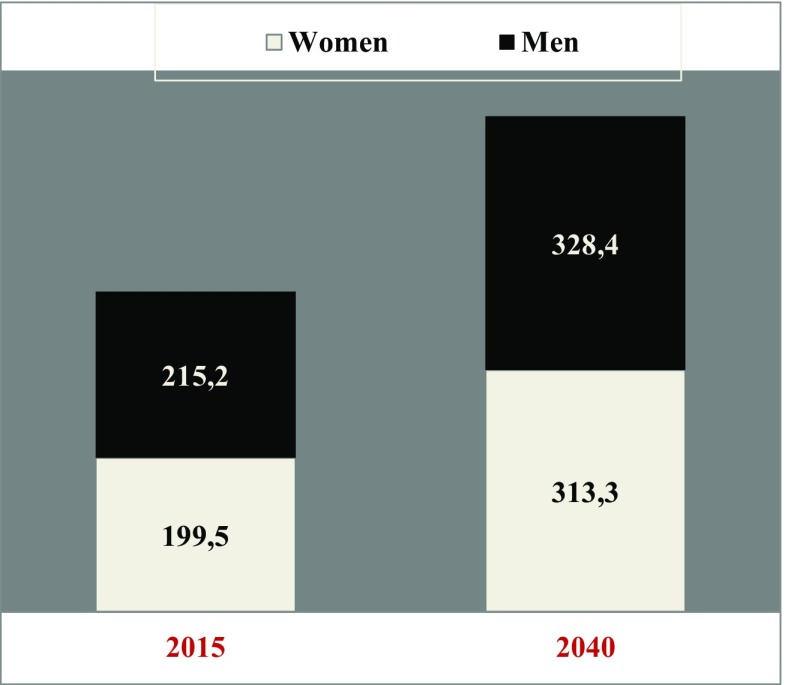

In contrast, gender-related patient distribution profiles are not expected to change significantly by the year 2040 compared to the status quo remaining slightly below 50% for women versus slightly over 50% for men, in general (see Fig. 5). However, current (year 2017) demographic DM profiles stratified by both gender and age are much more complex demonstrating higher prevalence of men younger than 65 years of age but more prevalent female diabetic patients in the groups aged 65 and older [8].

Fig. 5.

Gender-related patient distribution profiles (in million): actually (year 2015) registered patients versus prognoses for the year 2040 [7]

Global prognoses for the diabetes epidemic profiles

Due to many modifiable risk factors contributing (in both individual and synergistic manner) to DM predisposition and manifestation, any prognosis made for the next decades carries a highly speculative character. Moreover, the overall situation strongly depends on the scenario which will be systematically applied for further developments in healthcare sector and reflected in the quality of screening programmes, primary, secondary, and tertiary care, and either implemented or not innovative predictive and preventive approaches and personalisation of medical services. Therefore, significant deviations may be expected in the future against currently available prognoses. Nevertheless, a preliminary prognosis is of great importance for multifaceted aspects of the diabetes care to be considered and potentially revised in a long-term manner.

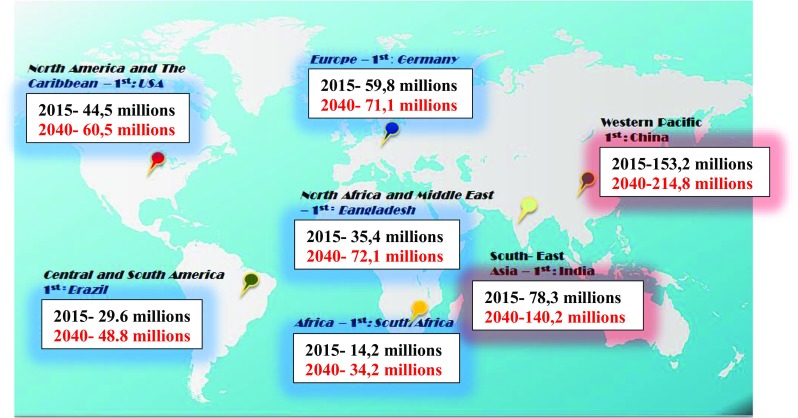

In Fig. 6, the prognostic estimations are presented for the DM prevalence against recently (year 2015) recorded numbers of patients worldwide. Absolute numbers recorded for the patients are the highest for both regions Western-Pacific and South-East ones. As summarised in Table 2, both regions are the main contributors to the epidemic of diabetes demonstrating synergistically 56% of the currently registered entire DM patients’ pool. Consequently, the prognostic estimations for the next decades are highly pessimistic for both regions demonstrating 1.4 till 1.8 times higher prevalence that corresponds to the similar level of the contribution by altogether 55.5% of entire patient’s pool by the year 2040. Currently, the third biggest contributor is Europe with 14% of the entire DM patients’ pool. However, the prognostic estimations are rather positive for the European region demonstrating the lowest increase in the DM prevalence compared to all other regions worldwide. In contrast, the highest increase in the DM prevalence is prognosed for the regions of Africa as well as North Africa & Middle-East by 2.4- and 2.0 times, respectively (see Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Current DM prevalence documented for the year 2015 versus prognostic estimations for the epidemic development over the next 2.5 decades; “1st” is used to demonstrate the country with the highest number of DM patients in corresponding regions [7]

Table 2.

Current and prognosed contribution of corresponding regions to the DM prevalence with an assumed increase till the year 2040 [6]

| Region | Current (year 2015) contribution of the region to the global prevalence of DM, % | Prognosed (year 2040) contribution of the region to the global prevalence of DM, % | Prognosed (year 2040 versus 2015) increase in the DM prevalence for the region |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western Pacific | 37 | 33.5 | 1.4-times |

| South-East | 19 | 22 | 1.8-times |

| Europe | 14 | 11 | 1.2-times |

| North America & The Caribbean | 11 | 9.5 | 1.4-times |

| North Africa & Middle-East | 9 | 11 | 2.0-times |

| Central & South America | 7 | 8 | 1.6-times |

| Africa | 3 | 5 | 2.4-times |

From [7]. The italicised entry means the lowest increase in the DM prevalence prognosed (year 2040) for the corresponding region compared to all others; in contrast, entries marked in bold demonstrate the strongest contribution of corresponding regions to the global DM prevance both - currently and prognosed (year 2040) as well as the highest increase in the DM prevalence for the region till the year 2040

Economic disaster by the persistently inadequate diabetes care worldwide

Table 3 shows top ten countries, which in year 2015 have recorded the highest numbers of diabetes patients worldwide. Diabetes epidemic—on a global scale—is a major and snowballing threat to public health, healthcare systems, and economy, due to the cascade of pathologies triggered in a long-term manner after the diabetes manifestation [1, 9]. The most frequent diabetes-related pathologies are a broad spectrum of cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and several types of cancer with particularly aggressive metastatic disease and poor individual outcomes [10, 11]. Over 60% of diabetes patients develop retinopathy as the leading cause of blindness, and 40–60% of diabetics are affected by nephropathy [1]. Up to 50% of diabetic patients suffer from peripheral neuropathy, which predisposes them to impaired wound healing and chronic wounds [12–14]. In the USA alone, over 25 billion US $ are spent annually for the treatment of chronic wounds affecting around 6.5 million patients [15, 16].

Table 3.

Top ten countries which in the year 2015 have recorded the highest numbers of DM patients worldwide; corresponding position is assigned from the highest (position 1) to lowest (position 10) number of patients [6]

| Position in the list | Country | Number of adult diabetic patients, in million |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | China | 109,6 |

| 2 | India | 69,2 |

| 3 | United States of America | 29,3 |

| 4 | Brazil | 14,3 |

| 5 | Russian Federation | 12,1 |

| 6 | Mexico | 11,5 |

| 7 | Indonesia | 10,0 |

| 8 | Egypt | 7,8 |

| 9 | Japan | 7,2 |

| 10 | Bangladesh | 7,1 |

From [7]

Current annual costs per one diabetes patient divided into “direct” and “indirect” costs for selected countries (in regions: North and South America, Europe, Asia) are demonstrated in Table 4 [17]. Obviously, the budgets released per capita differ significantly from country to country, and the questions regarding the costs efficacy and justification remain open. The total diabetes-related costs in the USA, including medical expenses and lost productivity, were monitored at the level of $299.3 billion in 2010 [18]. If currently applied reactive (delayed) medical approaches will persist in diabetes care, the annual diabetes-related costs prognosed for the USA will increase to the level of 514.4 billion US $ by the year 2025 [18]. This level of expenses extrapolated to the prognosed number of individuals who may get diseased on diabetes worldwide would result in the overall budgets of about 772 billion US $ for USA alone and 8.5 trillion US $ needed to be spent for about 0.650 billion patients in total by the year 2040. These astronomic numbers clearly demonstrate an urgent necessity to reconsider currently persisting reactive and delayed services in diabetes care in favour of the cost-effective predictive and preventive medical approach.

Table 4.

Diabetes-related direct versus indirect costs monitored for selected countries

| Country | Per capita direct costs, US $ | Per capita indirect costs, US $ |

|---|---|---|

| USA | > 9000 | 4000 |

| Spain | > 4000 | > 3000 |

| Italy | > 4000 | > 1000 |

| Germany | > 3000 | > 1000 |

| Canada | 3000 | > 1000 |

| China | > 3000 | < 1000 |

| Netherlands | 3000 | < 1000 |

| Sweden | > 2000 | > 2000 |

| Mexico | < 1000 | < 1000 |

From [17]

The key role of biomedical sciences in the future scenario of diabetes care: outlook and expert recommendations

Two opposed scenarios might be considered for the future developments of diabetes care.

A pessimistic scenario will follow current trends: on the one hand demonstrating rapidly increasing numbers of diabetes-diseased people and reaching the level of a billion patients worldwide in less than 30 years from now; on the other hand persisting services based on the reactive medical approach to treat clinically manifested diabetes and cascaded complications and collateral pathologies. Corresponding astronomic costs as presented by the above subchapters will strongly compromise the overall quality of diabetes care and may lead to a crash of particularly affected healthcare systems.

An optimistic scenario considers the paradigm shift from delayed medical services (disease care) to the advanced healthcare based on innovative approaches by predictive, preventive and personalised medicine (PPPM). However, this scenario might be feasible only in the case of innovative strategies applied synergistically by all stakeholders, namely researchers, caregivers, and policy-makers, amongst others. Table 5 summarises most innovative biomedical fields which are highly relevant for the development and practical application of the PPPM strategies. In the context of diabetes, notable are currently observed prompt strategical and technological developments in the fields of “risk assessment”, “prediction”, “modifiable risk factors”, “stem cells”, and “personalised medicine”.

Table 5.

Number of the topic-related articles recorded in PubMed; the search has been performed utilising “diabetes” in combination with other keywords listed below such as “prevention”, “economy”, etc

| Topic/key words | Total number of publications | 1. Number of articles published in 2000 | 2. Number of the topic-dedicated articles in years 2016-2017 | Ratio 2. to 1. (x-times) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention | 71 428 | 1 408 | 9 343 | 6,6 |

| Economy | 14 603 | 314 | 1 992 | 6,3 |

| Modifiable risk factors | 2 532 | 34 | 532 | 15,4 |

| Risk assessment | 25 798 | 255 | 4 309 | 16,9 |

| Prediction | 6 346 | 83 | 1 399 | 16,9 |

| Stem cell | 7 232 | 47 | 1 708 | 36,3 |

| Personalised medicine | 1 137 | 3 | 451 | 150 |

| Biomarker pattern | 671 | 9 | 134 | 14,9 |

| Big data | 288 | 0 | 126 | Infinity |

| Biobank | 390 | 0 | 227 | Infinity |

| Machine learning | 342 | 0 | 154 | Infinity |

| Liquid biopsy | 54 | 0 | 17 | Infinity |

| Predictive preventive personalised medicine (PPPM)* | 19 | 0 | 8 | Infinity |

| Individualised patient profile | 25 | 0 | 8 | Infinity |

| Multiomics | 2 | 0 | 2 | Infinity |

Entries in bold means significantly higher number of publications in the years 2000, 2016-2017 while entries in italics means the lowest number of publications and no publications at all in the year 2000 as recorded in PubMed.

*Note: 10 items have been found to the topic “PPPM diabetes” as published by the EPMA J. in years 2010-2017

On the other hand, specifically in diabetes research, currently underdeveloped are the below listed crucial fields, namely the following:

INDIVIDUALISED PATIENT PROFILING essential to advance personalisation of diabetes care

BIOMARKER PATTERNS both pathology- and stage-specific ones, which are essential for innovative screening programmes, e.g. in adolescent populations to identify persons at high risk for cost-effective targeted prevention by working on modifiable risk facts, as well as for patients with manifested diabetes to predict and prevent a cascade of secondary pathologies or to avoid unnecessary therapies (negative prediction)

MULTIOMICS utilising all the advantages of biomedical knowledge collected to allow advanced multilevel diagnostics

BIG DATA which would specifically support comprehensive patient data analysis, multi-professional networking in the field of diabetes research and management, more precise patient stratification increasing cost-effectiveness of treatment modalities applied

MACHINE LEARNING to maximise an efficacy of the learning processes, disease modelling and optimised treatment algorithms, creating innovative predictive screening approaches, amongst others

International BIOBANKING system for long-term retrospective analyses; it is getting more and more obvious that effectively combating diabetes needs well-organised global professional collaborations

The most comprehensive PPPM approach including predictive diagnostics, targeted prevention and treatments tailored to the person as the essential parts of the entire strategy in diabetes research and concomitant medical services is systematically promoted by the EPMA Journal, as it is evident from the statistics provided in Table 5. The greatest advantages of the PPPM against other innovative medical approaches such as “precision medicine” have been stated in the “EPMA position paper 2016” [19], as the most complex approach combining advantages of other individual medical approaches and minimising their specific disadvantages; the approach demonstrates clear concepts, with the highest level of maturity and most optimal strategies considering interests of healthy individuals, subpopulations, patient cohorts, healthcare systems, and the society as a whole.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the European Association for Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine (EPMA, Brussels) for professional and financial support of the project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Patients have not been involved in the study.

Human and animal rights

No experiments have been performed including patients and/or animals.

References

- 1.Golubnitschaja O. In: Three levels of prediction, prevention and individualised treatment algorithms to advance diabetes care: integrative approach. pp. 11–28. In book New Strategies to Advance Pre/Diabetes Care: Integrative Approach by PPPM. Mozaffari M, editor. Dordrecht: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes. 2016; ISBN 978 92 4 156525 7,http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204871/1/9789241565257_eng.pdf?ua=1 viewed on February 1st 2018.

- 3.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1513–1530. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Parkkola A, Laine AP, Karhunen M, Härkönen T, Ryhänen SJ, Ilonen J, Knip M, Register FPD. HLA and non-HLA genes and familial predisposition to autoimmune diseases in families with a child affected by type 1 diabetes. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0188402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercader JM, Florez JC. The genetic basis of type 2 diabetes in Hispanics and Latin Americans: challenges and opportunities. Front Public Health. 2017;5:329. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo B, Zhang J, Hu Z, Gao F, Zhou Q, Song S, Qin L, Xu H. Diabetes-related behaviours among elderly people with pre-diabetes in rural communities of Hunan, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e015747. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 7thedn. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2015; http://www.diabetesatlas.org viewed on February 1st 2018.

- 8.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 8th Edition, 2017. http://www.diabetesatlas.org/resources/2017-atlas.html.

- 9.Golubnitschaja O. Advanced diabetes care: three levels of prediction, prevention and personalized treatment. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2010;6:42–51. doi: 10.2174/157339910790442637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeghiazaryan K, Cebioglu M, Golubnitschaja O. In: Global figures argue in favour of preventive measures and personalised treatment to optimise inadequate diabetes care. pp. 1–13. In book New Strategies to Advance Pre/Diabetes Care: Integrative Approach by PPPM. Mozaffari M, editor. Dordrecht: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cebioglu M, Schild HH, Golubnitschaja O. Cancer predisposition in diabetics: risk factors considered for predictive diagnostics and targeted preventive measures. EPMA J. 2010;1(1):130–137. doi: 10.1007/s13167-010-0015-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adler AI, Boyko EJ, Ahroni JH, Stensel V, Forsberg RC, Smith DG. Risk factors for diabetic peripheral sensory neuropathy: results of the Seattle Prospective Diabetic Foot Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(7):1162–1167. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheehan P, Jones P, Caselli A, Giurini JM, Veves A. Percent change in wound area of diabetic foot ulcers over a 4-week period is a robust predictor of complete healing in a 12-week prospective trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(6):1879–1882. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Illigens BM, Gibbons CH. A human model of small fiber neuropathy to study wound healing. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, Kirsner R, Lambert L, Hunt TK, Gottrup F, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17(6):763–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avishai E, Yeghiazaryan K, Golubnitschaja O. Impaired wound healing: facts and hypotheses for multi-professional considerations in predictive, preventive and personalised medicine. EPMA J. 2017;8(1):23–33. doi: 10.1007/s13167-017-0081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seuring T, Archangelidi O, Suhrcke M. The economic costs of type 2 diabetes: a global systematic review. PharmacoEconomics. 2015;33(8):811–831. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0268-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute for Alternative Futures. United States’ diabetes crisis: today and future trends. Diabetes 2025 Forecasts, 2011; www.altfutures.org/diabetes2025

- 19.Golubnitschaja O, Baban B, Boniolo G, Wang W, Bubnov R, Kapalla M, Krapfenbauer K, Mozaffari M, Costigliola V. Medicine in the early twenty-first century: paradigm and anticipation—EPMA position paper 2016. EPMA J. 2016;7:23. doi: 10.1186/s13167-016-0072-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]