Abstract

Recent studies have shown that most prostate cancers carry the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion. Here we evaluated the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in small cell carcinoma (SCC) of the prostate (n=12) in comparison with SCC of the urinary bladder (n=12) and lung (n=11). Florescence in situ hybridization demonstrated rearrangement of the ERG gene in 8 cases of prostatic SCC (67%), and the rearrangement was associated with deletion of the 5' ERG gene in 7 cases. But rearrangement of the ERG gene was not present in any SCC of the urinary blader or lung. Next we evaluated the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in nude mouse xenografts that were derived from two prostatic SCCs carrying the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion. Two transcripts encoded by the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion were detected by RT-PCR, and DNA sequencing demonstrated that the two transcripts were composed of fusions of exon 1 of the TMPRSS2 gene to exon 4 or 5 of the ERG gene. Our study demonstrates the specific presence of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in prostatic SCC, which may be helpful in distinguishing SCC of prostatic origin from non-prostatic origins. The high prevalence of the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in prostatic SCC as well as adenocarcinoma implies that SCC may share a common pathogenic pathway with adenocarcinoma in the prostate.

Keywords: TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion, prostate cancer, small cell carcinoma, mouse xenograft

Introduction

Primary small cell carcinoma (SCC) of the prostate is a rare variant of prostate cancer, accounting for less than 2.0% of de novo prostate cancers.1 Prostatic SCC exhibits clinicopathologic features that are significantly different from those of prostatic adenocarcinoma, which accounts for the vast majority of prostate cancers.1–3 Most prostatic adenocarcinomas are asymptomatic and are identified by an increase of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA). The disease progresses slowly and metastasis usually occurs at an advanced stage with a predilection for the bone. Prostatic adenocarcinoma generally responds well to androgen ablation. Most patients are able to achieve long life expectancy. In contrast, most prostatic SCC patients present with symptoms, such as urinary outflow obstruction, hematuria, bone pain, and renal failure, yet their PSA levels are not usually increased. The disease progresses rapidly and metastasis often develops at an early stage with a predilection for visceral organs such as the liver and lungs. Due to the lack of androgen receptor, SCC is often resistant to androgen ablation. Most prostatic SCC patients die of disease within 1 year.3

SCC can arise in various organs with the lung being the most common origin. Because lung SCC is far more common than prostatic SCC, metastasis from a primary lung SCC should be always considered when SCC is observed in the prostate. Such distinction may be difficult, because SCCs of various origins share similar histologic, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features.4–6 Furthermore, most prostatic SCC lose the prostate-specific immunohistochemical markers, such as prostatic acid phosphatase, PSA, prostate-specific membrane antigen, and prostein.5 Therefore, a specific molecular marker is needed to help establish the prostatic origin of SCC.

Recent studies have revealed a unique gene fusion in the majority of prostate cancers.7–12 This gene fusion is characterized by the translocation of the 5’ transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) gene to the ETS-related gene (ERG) gene.7 The TMPRSS2 gene is regulated by androgen in the prostate, and the ERG gene, a transcriptional factor, functions as an oncogene. The fusion of TMPRSS2-ERG leads to an aberrant function of the ERG oncogene in the prostate, which is believed to contribute to the oncogenesis of prostate cancer. Several other ETS members, such as ETV1, ETV4, and ETV5, have also been found to be fused to the TMPRSS2 gene in prostate cancer.7,8,12 However, ERG is far more common than the other ETS members, accounting for over 80% of the TMPRSS2-ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer. To understand the role of the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in prostatic SCC, we evaluated the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in prostatic SCC in comparison with SCC of non-prostatic origins, and we also investigated the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in mouse xenografts derived from prostatic SCC carrying the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion.

Materials and methods

Case Selection

Twelve cases of prostatic SCC were obtained from the pathology files at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX, USA). The specimens included prostate biopsies (n=6), radical prostatectomies (n=5), and lymph node biopsy (n=1). In addition, 12 cases of SCC of the urinary bladder and 11 cases of SCC of the lung were also obtained for comparison. The histologic slides were reviewed for pathological analysis. Clinical and follow-up information was obtained from the medical records.

Immunohistochemistry

Four micrometer thick sections were cut from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks and immunostaining was performed in a DAKO Auto Stainer (Carpinteria, CA, USA) using EnVision polymer (DAKO). The following primary antibodies were used: prostate-specific antigen (PSA) (1:8000, Dako), synaptophysin (1:600, Novocastra, UK), chromogranin A (1:4000, Millipore, USA), CD56 (1:50, Invitrogen, USA). To enhance immunostaining, a heat-induced epitope retrieval procedure was performed using a Black and Decker vegetable steamer (Shelton, CT, USA). The antigen antibody immunoreaction was visualized using diaminobenzidine (DAB) as a chromogen. The slides were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin.

Determination of TMPRSS2-ERG Gene Fusion

TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion was evaluated by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) using break-apart probes of the ERG gene, as previously described.13 The probes, consisting of a rhodamine-labeled 5´-ERG probe (BAC RP11-95I21) and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled 3´-ERG probe (BAC RP11-476D17), were obtained from Children’s Hospital of Oakland Research Institute (Oakland, CA, USA). Tissue pretreatment was performed using Paraffin Pretreatment Kit I (Vysis, Des Plaines, IL, USA), and hybridization and washing were performed using Vysis hybridization reagents, following the manufacturer’s protocols. In cells with no ERG rearrangement, 2 pairs of co-localized green and red signals were present. In cells with ERG rearrangement, only 1 pair of co-localized green and red signals was maintained, the other pair either broke into 1 green signal and 1 red signal or lost the red signal. A mean of 100 cells was evaluated per tumor focus. A cutoff level of 10% was set for the FISH analysis, i.e., a positive signal required at least 10% of the evaluated nuclei showing rearrangement of the ERG gene.

Mouse Xenograft Models

With the approval of the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Medical Center, fresh tumor specimens from two patients (Case No. 3 and 9, Table 1) were collected. The specimens were cut into pieces of approximately 1 mm3 and trypsinized. The disaggregated cells were washed, counted and resuspended at 4–5 × 106 cells/100 µl of growth medium. About 2 × 106 cells were injected into subcutaneous pockets of 6- to 8-week-old male CB17 SCID mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) as previously described.14 The xenograft tumors were excised 8–10 weeks after the injection. A portion of each xenograft tumor was used for RNA extraction, and the rest of the tumor was fixed in 10% formalin overnight. Serial 5-µm tissue sections were cut from each sample; one section was stained with H&E, and adjacent sections were used for immunohistochemical staining or FISH analysis as described above. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with accepted standards of animal care and were approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Table 1.

Summary of patients’ clinicopathologic features and TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion status

| Case No. |

Age (years) |

Preexisting AdenoCa GS |

Intervala (months) |

SCC specimen |

Gene fusion | Follow-upb (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 72 | N/A | N/A | RP | Neg. | DOD (7) |

| 2 | 77 | 7 (3+4) | 57 | RP | Pos. del.(80%)d | DOD (3) |

| 3c | 71 | 7 (4+3) | 43 | RP | Pos. del. (90%) | DOD (11) |

| 4 | 62 | 9 (4+5) | 8 | PBX | Pos. del. (75%) | DOD (6) |

| 5 | 48 | 7 (3+4) | 19 | PBX | Neg. | DOD (1) |

| 6 | 64 | 9 (5+4) | 27 | PBX | Pos. del. (85%) | DOD (1) |

| 7 | 85 | 6 (3+3) | 117 | RP | Neg. | DOD (20) |

| 8 | 78 | 9 (5+4) | 59 | PBX | Pos. del. (80%) | DOD (23) |

| 9c | 44 | 6 (3+3) | 144 | LNBX | Pos. del. (70%) | DOD (22) |

| 10 | 77 | N/A | N/A | PBX | Neg. | DOD (21) |

| 11 | 72 | 8 (4+4) | 66 | RP | Pos. no del. (65%) | DOD (2) |

| 12 | 69 | N/A | N/A | PBX | Pos. del. (90%) | DOD (1) |

AdenoCa, adenocarcinoma; del., deletion; DOD, died of disease; GS, Gleason score; N/A, not available; LNBX, lymph node biopsy; Neg., negative; PBX, prostate biopsy; Pos., positive; RP, radical prostatectomy; SCC, small cell carcinoma.

Interval between the initial diagnosis of prostatic adenocarcinoma and the diagnosis of SCC.

Interval between the diagnosis of SCC and the time of death.

Prostatic SCC specimens from these two patients were used for mouse xenografts.

The number in parenthesis indicates the percentage of nuclei with positive gene fusion signal.

RT-PCR and DNA Sequencing

RNA was extracted using a Picopure RNA isolation kit (Arcturus Engineering, Mountain View, CA, USA). For cDNA preparation, the RNA was first treated with DNase I (Invitrogen), and reverse transcription was done using Superscript II (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription reactions were amplified by PCR using gene-specific primers under standard reaction conditions. The forward primer, TAGGCGCGAGCTAAGCAGGAG, matched exon 1 of the TMPRSS2 gene, and the reverse primer, CAACGGTGTCTGGGCTGCCCACC, matched exon 5 of the ERG gene. All products were resolved on 2% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide. DNA elution was performed to extract discrete PCR products from the gel, and direct PCR sequencing was performed on the purified PCR products.

Results

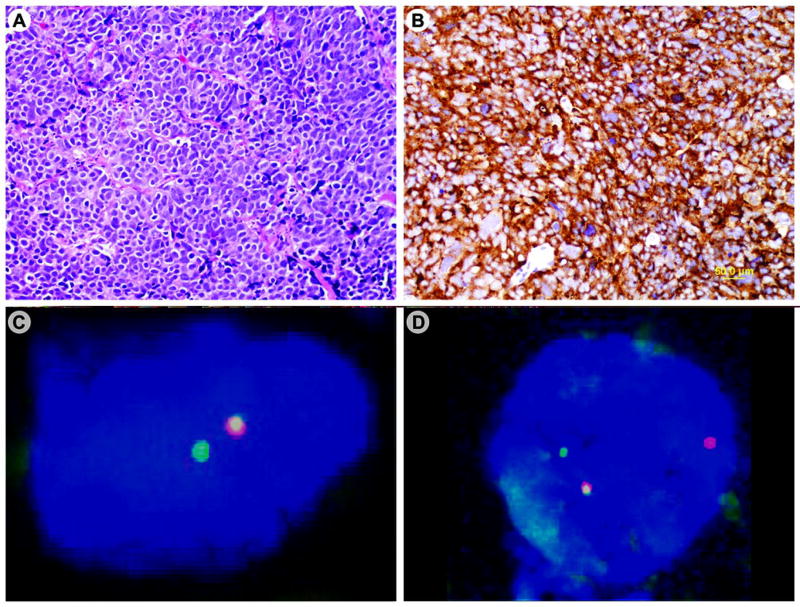

Twelve patients with prostatic SCC were selected for this study (Table 1). The mean age of patients at the diagnosis of prostatic SCC was 68 years (range, 44–77 years). Three patients had de novo prostatic SCC, and nine patients had a history of preexisting prostatic adenocarcinoma. In the latter, the mean interval between the initial diagnosis of prostatic adenocarcinoma and the diagnosis of SCC was 60 months (range, 8–144 months). The SCCs were composed of sheets of small cells with scant cytoplasm, dense nuclei, and inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 1A). In 11 cases, the neuroendocrine differentiation of the SCCs was supported by positive immunohistochemical staining for synaptophysin (Figure 1B), chromogranin, and CD56. In the remaining one case, immunostaining was not performed.

Figure 1.

Prostatic small cell carcinoma expresses the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion. The tumor shows solid sheets of poorly differentiated carcinoma cells with scant cytoplasm, dense nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli (A); the tumor cells are immunoreactive for synaptophysin (B); FISH analysis demonstrates rearrangement of the ERG gene associated with deletion of the 5’ ERG gene in one case (C) and without deletion in another case (D).

FISH analysis demonstrated rearrangement of the ERG gene, an indication of the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion, in 8 of the 12 cases (67%) of prostatic SCC. In the 8 cases with the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion, 65% to 90% of the evaluated nuclei showed positive ERG gene rearrangement signals (Table 1). In 7 cases, the rearrangement was associated with a deletion of the 5' end of the ERG gene (Figure 1C). In the remaining one case, the rearrangement was not associated with the deletion (Figure 1D). Rearrangement of the ERG gene was not observed in any SCC of the urinary bladder (Figures 2A and 2B) or the lung.

Figure 2.

Bladder small cell carcinoma lacks the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion. The tumor cells are poorly differentiated with scant cytoplasm and dense nuclei (A); FISH analysis shows no rearrangement of the ERG gene (B).

Mouse xenografts from 2 patients (No. 3 and 9 in Table 1) were established by subcutaneous implant of prostatic SCC. The xenograft tumors showed typical features of prostatic SCC (Figure 3A). On immunostains, the tumor cells were negative for PSA but positive for synaptophysin (Figure 3B) and chromogranin (Figure 3C). On FISH analysis, rearrangement of the ERG gene was present in both xenografts (Figure 3D). RT-PCR analysis yielded two discrete fusion transcripts (Figure 3E). DNA sequencing demonstrated that one product was a fusion of exon 1 of TMPRSS2 and exon 4 of ERG and the other product was a fusion of exon 1 of TMPRSS2 and exon 5 of ERG (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Mouse xenograft of prostatic small cell carcinoma expresses the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion. The xenograft tumor cells are poorly differentiated with scant cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (A); the tumor cells are immunoreactive for synaptophysin (B) and chromogranin (C); FISH analysis shows rearrangement of the ERG gene associated with a deletion of the 5’ ERG gene (D); RT-PCR demonstrates two discrete transcripts of the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in two xenografts derived from Cases # 3 (a) and # 9 (b). (E); DNA sequencing demonstrates that the two transcripts are fusions of exon 1 of the TMPRSS2 gene to exon 4 or 5 of the ERG gene (F).

Clinical follow-up was available for all patients (Table 1). The patients had received chemotherapy (n = 12), hormonal therapy (n = 10), radiation therapy (n = 8), and radical prostatectomy (n = 5). All patients developed metastasis and died at an average of 10 months (range, 1–23 months) after the diagnosis of SCC.

Discussion

Although the origin of SCC in the prostate remains uncertain, several hypotheses have been proposed. Because the majority of prostatic SCCs express neuroendocrine proteins, such as synaptophysin, chromogranin, and CD56, it is suggested that prostatic SCC may be derived from malignant transformation of neuroendocrine cells, a normal component in the prostatic glands.15 Similarly, some prostatic SCCs still express prostatic epithelial markers, such as PSA, prostate-specific membrane antigen, prostatic acid phosphatase, and prostein, it is also postulated that prostatic SCC may represent a dedifferentiation of the conventional prostatic adenocarcinoma during the progression of disease.16 Recently, it has been suggested that prostatic SCC may arise from the pluripotent stem cells in the prostate, as some prostatic SCCs demonstrate an extremely active proliferation.17 In this study, we found the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in the majority of prostatic SCC including de novo and those with previous history of prostatic adenocarcinoma, which would favor the opinion that prostatic SCC may evolve from conventional prostatic adenocarcinoma.

As SCCs of various origins share similar morphologic and immunohistochemical features, it may be difficult to determine the origin of SCC, especially after metastasis. Although prostatic markers such as prostatic acid phosphatase, PSA, prostate-specific membrane antigen, and prostein may be helpful in establishing the prostatic origin, the majority of prostatic SCCs are negative for these markers.5 Prostatic SCC was initially reported to be negative for thyroid transcription factor-1,18 nonetheless subsequent studies have found that most prostatic SCCs express TTF-1.6 A recent study found that CD44 may be a unique feature of prostatic SCC, but a substantial number of lung SCCs are also positive for CD44.19 In the current study, we found that the majority of prostatic SCCs carried the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion, while all SCCs of non-prostatic origins, including the lung and urinary bladder, lacked this gene fusion. Thus the specific expression of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in prostatic SCCs suggests that the TMRSS2-ERG gene fusion may be useful in establishing the prostatic origin of SCC.

Although prostatic SCC carries a unique molecular signature, the TMPSS2-ERG gene fusion, it shares similar clinical features with non-prostatic SCC.2–4 Regardless of the site of origin, all SCCs progress rapidly and have a dismal prognosis. Like non-prostatic SCC, prostatic SCC shows a favorable response to systemic chemotherapy composed of etoposide and cisplatinum.2–3 Although lung SCC is far more common than prostatic SCC, in the absence of a lung primary, the presence of SCC in a prostate specimen is most likely to be a prostatic primary.5 The involvement of prostate by lung SCC is rare and only occurs in the setting of widespread metastases. Hence, the distinction of prostatic SCC from non-prostatic origin has limited value in the prognosis and treatment of SCC patients.

Both TMPRSS2 and ERG genes are located on the long arm of chromosome 21. The TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion results from deleting the interval DNA, which includes the majority of the TMPRSS2 gene and a small portion of the 5’-ERG gene.7 On FISH analysis using the ERG break-apart probes, the interval DNA may be completely lost, which is characterized by rearrangement of the ERG gene with a deletion of the 5’ ERG gene, or the internal DNA is translocated to another chromosome, which is characterized by rearrangement of the ERG gene with no deletion. Several studies have suggested that the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion, particularly those associated with deletion of the 5’-ERG gene, is linked to an aggressive phenotype of prostate cancer.10,20–22 However, Gopalan et al found that the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion was not associated with recurrence, metastasis, or patient survival in a large scale study of more than 500 patients.23 Several factors, such as cohort selection, method of gene fusion detection, and clinical end point, may contribute to this inconsistency.

There have been limited studies of the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in prostatic SCC. A recent study by Han et al showed that 5 of the 7 cases (71%) of prostatic SCC carried the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion, which were all associated with deletion of the 5’-ERG.24 In the current study, we found that 8 of the 12 cases (67%) of prostatic SCC expressed the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion and the rearrangement was associated with deletion of the 5’-ERG gene in 7 cases. Thus the high prevalence of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in both prostatic SCC and adenocarcinoma suggests a close relationship between SCC and adenocarcinoma in the prostate. Furthermore, the presence of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in de novo prostatic SCC suggests that SCC may share a common pathogenetic pathway with adenocarcinoma in the prostate.

Mouse xenograft is a valuable model to study the regulatory mechanism of prostate cancer and to test new therapeutic modalities.25 Several mouse xenografts of metastatic prostate cancer have been established in our institution,26 and two of them were derived from metastatic prostatic SCC carrying the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion. The histologic and immunohistochemical features of prostatic SCC xenografts showed a striking resemblance to those observed in the patient’s original specimens. Furthermore, these two prostatic SCC xenografts also carried the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion. Our results suggest that mouse xenografts of prostatic SCC maintain the histologic, immunohistochemical and genetic features of the human original specimens.

Previous studies have shown that the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion gene expresses a variety of mRNA transcripts due to alternative splicing.9,11 In this study, we found that prostatic SCC expressed two different TMPRSS2-ERG transcripts, which were composed of fusion of exon 1 of TMPRSS2 to exon 4 or 5 of the ERG gene. Compared with the eight types of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion products in prostate cancer previously described by Wang et al,9 the transcripts in our prostatic SCCs represent types III and IV described in their study. Among the TMPRSS2-ERG transcripts reported in prostate cancer, type III is the most common form while type IV is the least common form.9 Interestingly, a previous study demonstrated similar findings in NCI-H660, a cell line originating from prostatic SCC.27 The TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in NCI-H660 involved the deletion of 5’-ERG and expressed two discrete transcript products, which were composed of the fusion of exon 1 of TMPRSS2 to exon 4 or 5 of the ERG gene. Although additional studies are needed, our limited studies suggest that prostate cancer carrying these two transcripts may have a predilection for the transformation to prostatic SCC.

In summary, we demonstrate that most human prostatic SCCs carry the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion, confirming the involvement of this gene fusion in prostatic SCC. In addition, mouse xenografts derived from human prostatic SCC also carry the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion. The presence of the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in both prostatic SCC and adenocarcinoma suggests a close relation of oncogenesis between them. Furthermore, the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion is not present in SCC of non-prostatic origins, including the lung and the urinary bladder. Thus the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion may be used as a molecular marker to establish the prostatic origin of metastatic SCC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by an Institutional Research Grant (to CCG) and a Startup Fund (to CCG) from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- 1.Palmgren JS, Karavadia SS, Wakefield MR. Unusual and underappreciated: small cell carcinoma of the prostate. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:22–9. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiess PE, Pettaway CA, Vakar-Lopez F, et al. Treatment outcomes of small cell carcinoma of the prostate: a single-center study. Cancer. 2007;110:1729–37. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein ME, Bernstein Z, Abacioglu U, et al. Small cell (neuroendocrine) carcinoma of the prostate: etiology, diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic implications--a retrospective study of 30 patients from the rare cancer network. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336:478–88. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181731e58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholson SA, Beasley MB, Brambilla E, et al. Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC): a clinicopathologic study of 100 cases with surgical specimens. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1184–97. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W, Epstein JI. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate. A morphologic and immunohistochemical study of 95 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:65–71. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318058a96b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao JL, Madeb R, Bourne P, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate: an immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:705–12. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200606000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomlins SA, Mehra R, Rhodes DR, et al. TMPRSS2:ETV4 gene fusions define a third molecular subtype of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3396–400. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J, Cai Y, Ren C, et al. Expression of variant TMPRSS2/ERG fusion messenger RNAs is associated with aggressive prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8347–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Attard G, Clark J, Ambroisine L, et al. Duplication of the fusion of TMPRSS2 to ERG sequences identifies fatal human prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:253–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark J, Merson S, Jhavar S, et al. Diversity of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcripts in the human prostate. Oncogene. 2007;26:2667–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helgeson BE, Tomlins SA, Shah N, et al. Characterization of TMPRSS2:ETV5 and SLC45A3:ETV5 gene fusions in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:73–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo CC, Zuo G, Cao D, et al. Prostate cancer of transition zone origin lacks TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion. Mod Pathol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.57. Apr 24 [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li ZG, Mathew P, Yang J, et al. Androgen receptor-negative human prostate cancer cells induce osteogenesis in mice through FGF9-mediated mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2697–710. doi: 10.1172/JCI33093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrahamsson PA. Neuroendocrine differentiation in prostatic carcinoma. Prostate. 1999;39:135–148. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19990501)39:2<135::aid-pros9>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schron DS, Gipson T, Mendelsohn G. The histogenesis of small cell carcinoma of the prostate. An immunohistochemical study. Cancer. 1984;53:2478–80. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840601)53:11<2478::aid-cncr2820531119>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helpap B, Köllermann J. Undifferentiated carcinoma of the prostate with small cell features: immunohistochemical subtyping and reflections on histogenesis. Virchows Arch. 1999;434:385–91. doi: 10.1007/s004280050357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ordóñez NG. Value of thyroid transcription factor-1 immunostaining in distinguishing small cell lung carcinomas from other small cell carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1217–23. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon RA, di Sant'Agnese PA, Huang LS, et al. CD44 expression is a feature of prostatic small cell carcinoma and distinguishes it from its mimickers. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:252–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demichelis F, Fall K, Perner S, et al. TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion associated with lethal prostate cancer in a watchful waiting cohort. Oncogene. 2007:4596–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210237. 5; 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehra R, Tomlins SA, Yu J, et al. Characterization of TMPRSS2-ETS gene aberrations in androgen-independent metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3584–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perner S, Mosquera JM, Demichelis F, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer: an early molecular event associated with invasion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:882–8. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213424.38503.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gopalan A, Leversha MA, Satagopan JM, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion is not associated with outcome in patients treated by prostatectomy. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1400–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han B, Mehra R, Suleman K, et al. Characterization of ETS gene aberrations in select histologic variants of prostate carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.79. May 22 [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Weerden WM, Romijn JC. Use of nude mouse xenograft models in prostate cancer research. Prostate. 2000;43:263–71. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20000601)43:4<263::aid-pros5>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navone NM, Logothetis CJ, von Eschenbach AC, Troncoso P. Model systems of prostate cancer: uses and limitations. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1999;17:361–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1006165017279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mertz KD, Setlur SR, Dhanasekaran SM, et al. Molecular characterization of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in the NCI-H660 prostate cancer cell line: a new perspective for an old model. Neoplasia. 2007;9:200–6. doi: 10.1593/neo.07103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]