Abstract

Context:

Obesity is a major health concern in Saudi Arabia. Uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) seems to play a major role in the regulation of human metabolism; therefore, genetic polymorphisms in the UCP2 gene might contribute to obesity.

Aim:

This study aims to establish whether 45-blood pressure (BP) insertion (I)/deletion (D) polymorphisms in UCP2 are associated with moderate and/or severe obesity in a Saudi Arabian population.

Settings and Design:

Case–control study design.

Materials and Methods:

The study enrolled 151 male and female subjects originating from the eastern province of Saudi Arabia, and assigned each to a “nonobese,” “moderately obese,” or “severely obese” group. Genomic DNA was extracted from all subjects and screened for UCP2 I/D polymorphisms using a standard polymerase chain response protocol.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Analysis of variance, Chi-squared tests, and logistic regression analysis.

Results:

The frequencies of the UCP2 45-BP I/D genotypes D/D, I/D, and I/I within the analyzed population were 58.3%, 36.4%, and 5.3%, respectively. The D/D genotype was highly prevalent within the severely obese group (82.9%) compared to the nonobese (46.2%) and moderately obese (53.3%) groups. Using a dominance model, the conducted logistic regression analysis showed a strong association between the deletion allele and severe obesity (Odds ratio = 0.18, 95% confidence interval: 0.07–0.44, P = 0.0004).

Conclusions:

The present study reported that the frequency of UCP2 45-BP I/D polymorphisms in a population originating from eastern Saudi Arabia and identified a strong association between the D/D genotype and severe obesity.

Keywords: Obesity, Saudi Arabia, uncoupling protein 2 insertion/deletion polymorphism

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is becoming a major health concern in Saudi Arabia. This become[1,2] Uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) is a member of the mitochondrial anion carrier protein subfamily that functions to increase proton influx through the inner mitochondrial membrane without adenosine triphosphate synthesis, thereby enabling efficient caloric consumption and heat generation.[3] The common 45- blood pressure (BP) insertion/deletion (I/D) polymorphism at exon 8 of the UCP2 gene has been shown to affect mRNA stability and probably protein function, resulting in lower metabolic rate and obesity.[4,5] A meta-analysis found no association between the UCP2 I/D polymorphism and obesity.[6] However, it is likely that geographical differences continue to influence the pattern of distribution of UCP2 I/D polymorphisms, as well as their relatedness to obesity. Thus, the current study investigated whether the UCP2 45-BP I/D polymorphisms are associated with moderate and/or severe obesity in a Saudi Arabian population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics

Informed consent was provided by all subjects for their participation in the study, whose design was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. The procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee and with the guidelines provided by the CPCSEA and World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (2000).

Participants

The present case–control study recruited 151 volunteer (male and female, aged 35–60 years) subjects who originated from the eastern province of Saudi Arabia and attended the out-patient blood collection service provided by the King Fahd University Hospital at Al-Khobar in February–July 2016. The subjects were divided into three groups: (1) “nonobese” (body mass index [BMI] <30 kg/m2, n = 65), (2) “moderately obese” (BMI 30–35 kg/m2, n = 45), and (3) “severely obese” (BMI ≥35 kg/m2, n = 41).

Baseline measurements

Sociodemographic and health data for each subject (including sex, age, exhibition of type II diabetes mellitus and/or hypertension, and cigarette use), were provided through a structured questionnaire. Anthropometric data (including subject weight, height, and waist circumference) were measured using a metric and a vertical weight scale, with bare feet, and only light clothing. Each subject's BMI value was indirectly calculated according to the formula below

BMI = Subject's weight (kg)/(subject's height [m])2

Blood collection and DNA extraction

Whole blood samples (5 ml) were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid vacutainer tubes through aseptic venipuncture. Genomic DNA was then extracted from the leukocytes contained in 300 μL of each of these samples using an Illustra blood genomicPrep Mini Spin Kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences Ltd., UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Genotyping analysis

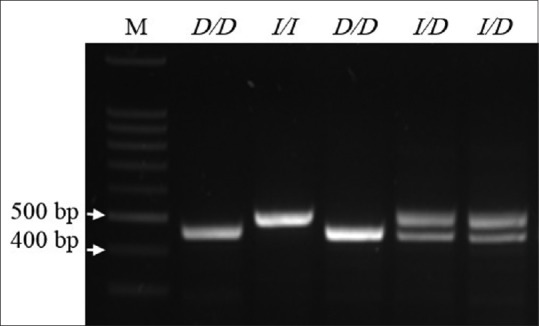

The presence/absence of the UCP2 45-BP I/D polymorphism was assessed through polymerase chain response using a 2 × master mix (Promega; Wisconsin, USA), 1 μL of extracted template DNA, and 1 μL (0.1 μg) each of forward (5’ CAG TGA GGG AAG TGG GAG G 3’) and reverse (5’ GGG GCA GGA CGA AGA TTC 3’) primer. DNA amplification was achieved using a thermal profile comprising initial denaturation for 4 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 93°C, primer binding for 30 s at 58°C, and elongation for 30 s at 72°C, and a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. The resultant products (10 μL) were then separated on a 1% agarose gel and visualized using ethidium bromide (0.5 μL/gel). D and I alleles were identified to be present by the appearance of 412-BP and 457-BP bands, respectively [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The presence/absence of the Uncoupling protein 2 45-blood pressure insertion/deletion polymorphism was confirmed by separating Polymerase chain reaction products on a 1% agarose gel. Lane 1, DNA ladder; Lane 2 and 4, D/D genotype; Lane 3, I/I genotype; Lane 5 and 6, I/D genotype

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software (California, USA). Data from all study groups were presented as either the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as percentage values. Continuous variables were assessed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA), whereas categorical variables were compared using either a Chi-squared or Fisher's exact test. Potential associations between the UCP2 I/D polymorphisms and obesity were evaluated by calculating the odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and two-sided Chi-squared test and/or Yates’ correction P values to conduct logistic regression analyses. A logistic binary regression was used to adjust all ORs for confounding parameters such as subject age and sex. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

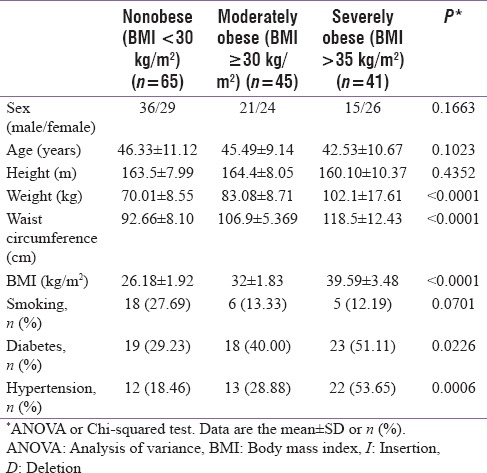

The demographic characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the study population was 44.78 ± 10.31 years, and no statistical difference in age was observed among the three study groups (P = 0.1023). The overall male/female ratio, which was 72/79 across the three study groups, was reduced in both the moderately and the severely obese subject groups compared to the nonobese group; however, these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.1663). The mean (± SD) BMI values for the non, moderately, and severely obese subject groups were 26.18 ± 1.92, 32 ± 1.83, and 39.59 ± 3.48, respectively, and significantly different in the conducted ANOVA test (P ≤ 0.0001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of the study population (n=151)

Type II diabetes mellitus and hypertension were more prevalent in the moderately (affecting 40% and 28.9% of subjects, respectively) and the severely obese (affecting 51.1% and 53.65% of subjects, respectively) groups than in the nonobese group (affecting 29.2% and 18.5% of subjects, respectively). In contrast, the frequency of cigarette use was increased in the nonobese group (27.7%) compared to the moderately (13.3%) and severely obese (12.2%) groups.

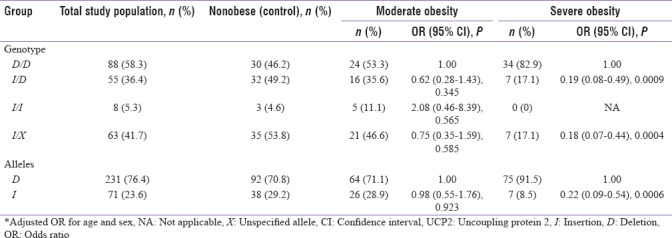

The UCP2 45-BP I/D genotypes D/D, I/D, and I/I occurred with a frequency of 58.3%, 36.4%, and 5.3% across the total study population, respectively, whereas the deletion and insertion alleles were detected in 76.4% and 23.6% of study subjects, respectively. The D/D genotype was more highly prevalent in the severely obese group (82.9%) compared to the nonobese (46.2%) and moderately obese (53.3%) groups. The logistic regression analysis showed no significant association between the I/X genotypes (where X represents a nonspecified allele) and the development of moderate obesity (OR = 0.75, 95% CI): 0.35–1.59, P = 0.585); however, a strong inverse association was found between these genotypes and severe obesity (OR = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.07–0.44, P = 0.0004) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Association of uncoupling protein 2 54-bp insertion/deletion polymorphisms with obesity

DISCUSSION

The role of the 45-BP I/D polymorphism in exon 8 of the UCP2 gene in the development of obesity is unclear. Thus, the current study investigated the frequency of this polymorphism in nonobese, moderately obese, and severely obese subjects originating from the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Although no significant association was found between either the insertion or deletion alleles and moderate obesity [Table 2], or with an “overweight” BMI (25–30 kg/m2) or type II diabetes mellitus (data not shown), a strong association was identified between the D/D genotype and severe obesity in this population. In fact, subjects with this genotype were found to experience a 5-fold greater risk for developing severe obesity than those who harbored at least one insertion allele.

Most previously conducted association studies found no direct link between the UCP2 45-BP I/D polymorphism and either obesity or various related metabolic disorders.[7,8,9,10,11,12] Notably, some previous studies showed the insertion allele to be positively associated with obesity, contradictory to the findings of the present study.[13,14,15,16] Nevertheless, various studies have produced results consistent with those presented here, suggesting that the D/D genotype may contribute to the development of obesity and its related metabolic disorders. For instance, the deletion allele has been previously associated with lower resting metabolic and energy expenditure rates in young adults, and thus postulated to contribute to the development of obesity at a later age.[4,17] Similarly, subjects carrying the insertion allele in a metabolically healthy Greek population were previously shown to exhibit improved weight loss profiles compared to those harboring the D/D genotype.[12] Previous screening of a Tongan population with a known increased the prevalence of obesity revealed the D/D genotype to be highly prevalent (97%).[18] Finally, a recent study in the region adjacent to the population analyzed by the present study reported a significant association between the D/D deletion and metabolic syndrome, for which obesity is a well-known risk factor.[19]

In Saudi Arabia, obesity is a common health concern caused by excessive caloric intake and/or low physical activity levels. The reduced metabolic and energy expenditure rates incurred by the D/D genotype likely aggravate the tendency to develop severe obesity in this population.[20] Notably, previous analysis of a western Saudi Arabian population showed the I/D polymorphism to be associated with neither obesity nor type II diabetes mellitus.[21] This discrepancy may reflect the fact that this previous study did not consider moderately and severely obese subjects separately, or alternatively, it may reflect genetic differences incurred by geographical separation of the two populations.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study showed the distribution of the UCP2 D/D, D/I, and I/I genotypes in the analyzed eastern Saudi Arabian population to be 58.3%, 36.4%, and 5.3%, respectively. Moreover, the D/D genotype was shown to be strongly associated with severe, but not moderate, obesity. These findings provide valuable insights into the genetic contribution of UCP2 to obesity and related disorders in Saudi Arabia and should be confirmed via additional research with larger and more geographically diverse cohorts.

Financial support and sponsorship

The research is funded by the deanship of scientific research University of Dammam.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

I take this opportunity to thank Mrs. Amani Al-Omairy for her great support to conduct this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.ALNohair S. Obesity in gulf countries. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2014;8:79–83. doi: 10.12816/0006074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Memish ZA, El Bcheraoui C, Tuffaha M, Robinson M, Daoud F, Jaber S, et al. Obesity and associated factors – Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E174. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brand MD, Esteves TC. Physiological functions of the mitochondrial uncoupling proteins UCP2 and UCP3. Cell Metab. 2005;2:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walder K, Norman RA, Hanson RL, Schrauwen P, Neverova M, Jenkinson CP, et al. Association between uncoupling protein polymorphisms (UCP2-UCP3) and energy metabolism/obesity in pima Indians. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1431–5. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.9.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindholm E, Klannemark M, Agardh E, Groop L, Agardh CD. Putative role of polymorphisms in UCP1-3 genes for diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2004;18:103–7. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(03)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang M, Wang M, Zhao ZT. Uncoupling protein 2 gene polymorphisms in association with overweight and obesity susceptibility: A meta-analysis. Meta Gene. 2014;2:143–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mgene.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalgaard LT, Sørensen TI, Andersen T, Hansen T, Pedersen O. An untranslated insertion variant in the uncoupling protein 2 gene is not related to body mass index and changes in body weight during a 26-year follow-up in Danish Caucasian men. Diabetologia. 1999;42:1413–6. doi: 10.1007/s001250051312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maestrini S, Podestà F, Di Blasio AM, Savia G, Brunani A, Tagliaferri A, et al. Lack of association between UCP2 gene polymorphisms and obesity phenotype in Italian Caucasians. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:985–90. doi: 10.1007/BF03348196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ochoa MC, Santos JL, Azcona C, Moreno-Aliaga MJ, Martínez-González MA, Martínez JA, et al. Association between obesity and insulin resistance with UCP2-UCP3 gene variants in spanish children and adolescents. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;92:351–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yiew SK, Khor LY, Tan ML, Pang CL, Chai VY, Kanachamy SS, et al. No association between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor and uncoupling protein gene polymorphisms and obesity in Malaysian university students. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2010;4:e247–342. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, Zhang B, Liu X, Shen Y, Li J, Zhao N, et al. A45-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism in uncoupling protein 2 is not associated with obesity in a Chinese population. Biochem Genet. 2012;50:784–96. doi: 10.1007/s10528-012-9520-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papazoglou D, Papathanasiou P, Papanas N, Papatheodorou K, Chatziangeli E, Nikitidis I, et al. Uncoupling protein-2 45-base pair insertion/deletion polymorphism: Is there an association with severe obesity and weight loss in morbidly obese subjects? Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2012;10:307–11. doi: 10.1089/met.2012.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cassell PG, Neverova M, Janmohamed S, Uwakwe N, Qureshi A, McCarthy MI, et al. An uncoupling protein 2 gene variant is associated with a raised body mass index but not type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 1999;42:688–92. doi: 10.1007/s001250051216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans D, Minouchehr S, Hagemann G, Mann WA, Wendt D, Wolf A, et al. Frequency of and interaction between polymorphisms in the beta3-adrenergic receptor and in uncoupling proteins 1 and 2 and obesity in Germans. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1239–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marti A, Corbalán MS, Forga L, Martinez-González MA, Martinez JA. Higher obesity risk associated with the exon-8 insertion of the UCP2 gene in a spanish case-control study. Nutrition. 2004;20:498–501. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YH, Kim W, Yu BC, Park BL, Kim LH, Shin HD, et al. Association of the ins/del polymorphisms of uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) with BMI in a korean population. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:767–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovacs P, Ma L, Hanson RL, Franks P, Stumvoll M, Bogardus C, et al. Genetic variation in UCP2 (uncoupling protein-2) is associated with energy metabolism in pima Indians. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2292–5. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1934-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duarte NL, Colagiuri S, Palu T, Wang XL, Wilcken DE. A 45-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism of uncoupling protein 2 in relation to obesity in Tongans. Obes Res. 2003;11:512–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashemi M, Rezaei H, Kaykhaei MA, Taheri M. A 45-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism of UCP2 gene is associated with metabolic syndrome. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:12. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-13-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeNicola E, Aburizaiza OS, Siddique A, Khwaja H, Carpenter DO. Obesity and public health in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Rev Environ Health. 2015;30:191–205. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2015-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiffri E. Association of the UCP2 45-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism with diabetes type 2 and obesity in Saudi population. Egypt J Med Hum Genet. 2012;13:257–62. [Google Scholar]