Abstract

Drawing on past research, including my own, I set forth the following propositions: (1) inequality in China has been generated and maintained by structural collective mechanisms, such as regions and work units; (2) traditional Chinese political ideology has promoted merit-based inequality, with merit being perceived as functional in improving the collective welfare for ordinary people; and (3) many Chinese people today regard inequality as an inevitable consequence of economic development. Thus, it seems unlikely that social inequality alone would lead to political and social unrest in today’s China.

Keywords: Attitude/ideology, China, economic development, inequality

Introduction

The title of this paper requires a brief clarification. The word “understanding” means a scholarly approach to knowledge, which is an end in itself. I offer my research-based observations on a politically sensitive topic in China, free of value judgment. That is, I approach inequality in this paper more as an empirical reality subject to scientific inquiry than as a social problem requiring political intervention.

China today is undergoing a dramatic social transformation comparable in historical importance to the Renaissance in early Europe or the Industrial Revolution in eighteenth and nineteenth century Britain (Xie, 2011). Involving the largest population in the world today, the social changes taking place in China have been unprecedentedly extensive in scale and far-reaching in their consequences. At an astoundingly rapid rate, many fundamental aspects of Chinese society have changed irreversibly. As scholars, contemporary social scientists are fortunate to have the opportunity to observe, document, analyze, and understand these ongoing social changes in China.

The magnitude of China’s social transformation can best be seen in terms of four aspects:

Economic development. The national economy has not only experienced rapid expansion in volume, but is also undergoing an institutional shift from central planning to a market economy.

Social changes. Many aspects of Chinese society have changed. For example, socialist social arrangements, such as the state/danwei (work unit)-controlled assignment of jobs and housing in urban China, no longer apply to most urban residents today.

Demographic transition. Although it has attracted only limited attention in social science, China’s demographic transition in recent decades created an important condition for the country’s phenomenal economic growth. The rapid decline in mortality since the 1950s and the sharp drop in fertility since the late 1970s have had far-reaching consequences for the nation.

Cultural shift. Through global contact, the Western way of life has gained more and more ground in China, while at the same time Chinese traditions have been waning. This cultural change, combined with varying sub-cultures in different social groups, has produced rich cultural dynamics in contemporary China. These changes have greatly influenced Chinese people’s daily lives and work. It is against the backdrop of these broader changes that inequality, an aspect of major social transformation, has been evolving in contemporary China.

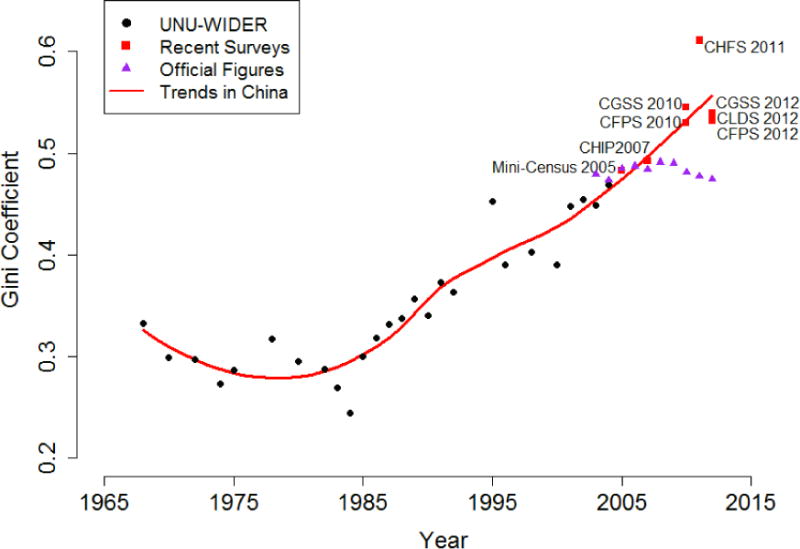

China’s rapid economic growth over an extended period since the beginning of the economic reform in 1978 has been accompanied by a sharp rise in income inequality (Han, 2004; Xie and Zhou, 2014). The measurement of economic inequality in China is rather controversial in academia. There are concerns about data authenticity, reliability, and comparability with other countries (Hvistendahl, 2013). Whether or not the Gini coefficient provides valid assessment of inequality is subject to debate, but it remains the most frequently used indicator (Wu, 2009). In Figure 1, I present a series of Gini coefficients for family income reported recently in Xie and Zhou (2014). The series came from three sources: (1) numbers for earlier years reported by UNU-WIDER (2012), (2) government statistics for recent years, and (3) estimates from recent surveys conducted by four university survey organizations (Xie and Zhou, 2014).

Figure 1.

Trends in China’s Family Income Gini Coefficients

Source: Xie and Zhou (2014).

As shown clearly in Figure 1, the trend of a rapid and large-scale rise in China’s income inequality is indisputable. The Gini coefficient rose from around 0.3 in the late 1980s to over 0.5 in the 2010s. A pressing question is: How can we properly understand the rise in income inequality in contemporary China? Some observers in journalism argue that economic inequality will lead to political and social instability in China. This possibility has raised popular concerns due to the seriousness of the consequences implied (See Wu, 2009 and Whyte, 2010 for more detailed discussions).

There is no simple answer to this question. I raise the question hoping not so much to answer it as to set an extensive research agenda. This is because I believe we should not and cannot study inequality in total isolation from other aspects of Chinese society. Unlike in the experimental sciences, where the aim of research is often to isolate confounding and contextual effects, we must understand China’s inequality within the context of the country’s history, culture, politics, and economy. With so much to be empirically studied, my current understanding of the inequality in China is preliminary. Yet, I venture to advance several tentative propositions in this article, as follows.

First, China’s inequality, to a great extent, is attributable to collective agencies such as geographic locations, household registration (hukou), work units, social networks, villages, kinship lineages, families, etc. In other words, much of the inequality exists not at the individual level but at the meso-collective level.

Second, traditional Chinese political ideology endorses merit-based inequality. Merit here refers to administrative performance that is measured by the provision of the public good to ordinary people. Leaders in Chinese society are often rewarded with various benefits and privileges for providing the public good. That is, if the privileges enjoyed by the ruling class bring about desirable outcomes for others in society, unequal treatment is accepted and even encouraged in the Chinese meritocratic tradition.

Third, likely due to propaganda and actual experiences in recent years, many Chinese view inequality as a necessary cost of economic development. The state propaganda organ has taken pains in driving home the message that economic development requires some people to get rich sooner, the resulting inequality being a cost that must be paid. As of now, many Chinese people may subscribe to this point of view, holding that inequality is an inevitable, albeit undesirable, outcome in the course of a country’s economic development. Below, I will provide more details to explain why I advance these three propositions to help us understand China’s inequality.

Three propositions on inequality in China

Collective agency

To understand inequality in China, it is necessary to take the distinct social, political, and cultural features of Chinese society into account, while recognizing the danger of overemphasizing differences between China and other countries. Both overemphasizing and totally denying such differences would be wrong.

To be sure, China has its own unique characteristics, though many of these are only quantitatively, rather than qualitatively, different from the characteristics of other countries. First, in China, the government plays a prominent role, from the central government to the local administration level. Second, business enterprises and the government are often allies in China, sharing mutual economic interests and maintaining close relationships. Third, multi-layered paternalism is a long and well-established Chinese tradition (Brown and Xie, 2015). A member of Chinese society has always been imbedded in multiple layers of collective entities. This stands in sharp contrast to ancient Greece, where citizens were equal and were able to participate in politics directly and independently, although not everyone was a citizen, and their society was small. Partly due to the vastness of China, the societal role of a Chinese citizen is often indirect, nested in and mediated by a relatively small locale or danwei, which, in turn is nested in a larger danwei or local government (Xie, Lai, and Wu, 2009).

Administration in China is hierarchical and nested, mediating individuals who otherwise would be isolated in society at large. Within this structure, affiliation with a danwei is important because Chinese society emphasizes common interests within a collective unit. A member or leader of a danwei is not an independent individual but derives his/her roles in society from the danwei to which he/she belongs. In this respect, there are significant differences between Chinese and western societies. By the term “multiple layers,” I mean several hierarchical layers. For example, such layers include family and social network, danwei, basic-level government, and local government. These are all different layers. In brief, Chinese society is structured on multiple levels and nested hierarchically from the top down.

For this reason, I do not believe that the Chinese economy is simply moving towards a market economy or, more specifically, an American-style market economy. It is naïve to assert that China is just another capitalist society like the U.S., or that even if it is not such a society today, it will become one eventually. I reject the prediction that China will establish a completely capitalistic economic and social system in the near future.

As a sociologist, I have discerned some distinct characteristics of China in terms of social structure, traditional culture, and mutual-interest relationships. My early paper with Hannum (Xie and Hannum, 1996) pointed out that in China the most influential factor for earned income is not individual attributes, but regional location. Later, in Hauser and Xie (2005), we further discovered that the influence of regional differences on determinants of earnings had increased. Wu and Treiman’s (2004) research shows that household registration (hukou) has a great influence on people’s social status; that is, there is a large disparity between rural and urban hukou holders (Wu and Treiman, 2004). These differences by region or hukou status cannot be attributed to personal effort and ability since they represent structural differences from which an individual has difficulty breaking away. A paper by Xie and Wu (2008) discussed the importance of danwei in contemporary China. We believe that even today danwei still plays a significant role in affecting personal income, prestige, welfare, and social network. Feng Wang’s book (Wang, 2008) also supports this perspective.

The Guardian once published an article (Vidal, 2008) based on a study conducted by the United Nations under the headline, “Wealth Gap Creating a Social Time Bomb.” Although it did not discuss China in depth, it referred to the country twice. The article first quoted research showing that Beijing is the most egalitarian place in the world, but then it claimed that there was severe inequality in China. How could these two contradictory viewpoints coexist in the same article? Actually, they are not contradictory. The level of China’s inequality is high, but a major part of it is interregional and intergroup inequality, such as the inequality between Beijing and other cities or that between the rural population and the urban population. Within a single city, for example Beijing, inequality among residents is lower than that in other metropolises such as New York or London, although it may not be the lowest in the world, as the article claimed. Relatively speaking, many other cities have higher levels of inequality. Thus, these two seemingly contradictory viewpoints tell us that regional disparity accounts for a large part of the inequality in China.

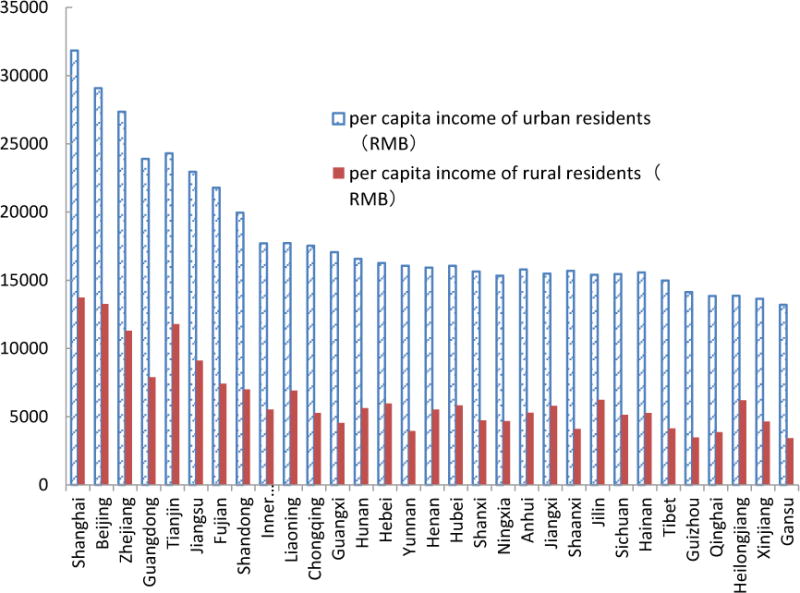

Based on official statistics for 2010, we can illustrate the importance of geographic region. In Figure 2, we can observe the prominence of regional variation in income. At the same time, the disparity between rural and urban areas is also large. The patterns shown in this statistical graph are in accordance with our general understanding: The average per capita income is high in Shanghai and Guangdong, but low in western regions such as Gansu; urban populations enjoy higher incomes than their rural counterparts. The magnitude of these disparities is greater in China than in other countries (e.g., the U.S.—see Xie and Zhou, 2014).

Figure 2.

Cross-province Comparison of Per-Capita Income Separately for Urban/Rural Residents, 2010

Along with region, the work unit (danwei) is also a significant collective agency producing and maintaining inequality. As is widely known, before the economic reform in 1978, the danwei determined almost every aspect of an individual’s social existence, including daily life needs, political life, work, economic welfare, and so on. In those days, danwei (or linong, i.e., neighborhood) was responsible for distributing nearly all the ration coupons for things such as meat, grain, sugar, film, bathing facilities, bicycles, and sewing machines. In addition, not only would a danwei approve one’s marriage, it also provided housing. If a marriage was unhappy, the danwei was supposed to intervene to improve the couple’s relationship. If someone violated a law, others would first report it to the person’s danwei, rather than to local authorities. Some observers argue that after the economic reform in 1978, the situation changed, that the system of danwei broke down or was no longer important. In my view, these observations are incorrect and the danwei continues to play an essential role in today’s China. As a simple example illustrating this, when undergraduate students fail to deal properly with their personal matters, administrators of their departments, colleges, or universities (students’ danwei)are still held responsible.

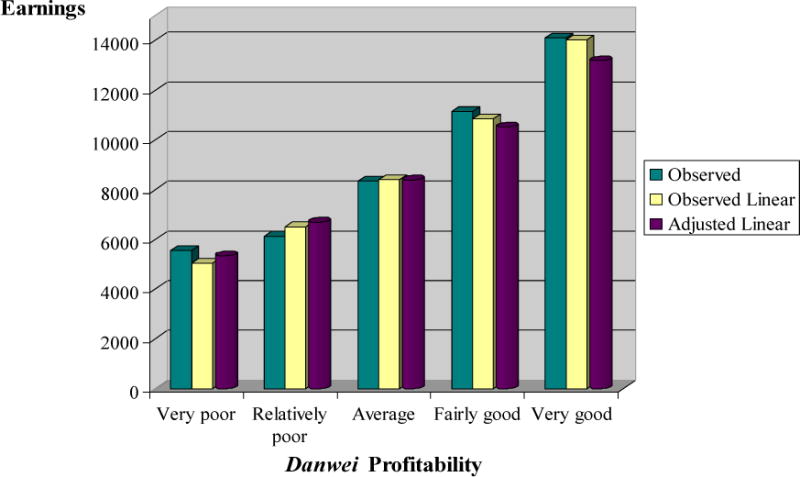

In 1999, we conducted a survey in Shanghai, Wuhan, and Xi’an. Through statistical analyses of the data, we found that danwei is the second major factor that determines people’s incomes, second only to the factor of region and city location and surpassing individual-level factors such as education level, experience, gender, cadre status, and so on (Xie and Wu, 2008) (see Table 1). In China (especially in cities), a danwei’s profitability has great influence on personal income (see Figure 3). For example, there is significant income inequality among university professors. Why do some of professors enjoy higher salaries than others in China?

Table 1.

Percent Variance Explained in Logged Earnings

| Viable | DF | R2 | ΔR2 (1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| City | 2 | 17.47*** | 19.12*** |

| Education Level | 5 | 7.82*** | 4.46*** |

| Working Years+ Working Years2 | 2 | 0.23 | 0.05 |

| Gender | 1 | 4.78*** | 3.05*** |

| Cadre Status | 1 | 3.08*** | 0.63*** |

| Working Sector | 3 | 3.54*** | 1.8*** |

| Profitability of danwei (linear) | 1 | 12.52*** | 9.3*** |

| Profitability of danwei (dummies) | 4 | 12.89*** |

Notes:

p≤0. 05;

p≤0. 01;

p≤0. 001. Based on F test.

ΔR2(1) refers to the incremental R2 after the inclusion of Danwei’s financial situation (linear).

Source: Xie and Wu (2008), based on a survey in Shanghai, Wuhan and Xi’an in 1999.

Figure 3.

Earnings Differentials by Danwei Profitability

To a large extent, inequality of professors’ salaries can be attributed to universities’ (danweis’) salary policies, rather than to the market or the amount of work measured by courses taught or research conducted. Salaries for university professors are largely determined by their affiliations with a particular university and particular college or department within the university. That is to say, danwei exert a large influence on professors’ incomes.

By extension of this logic, it is not difficult to understand why employee income of s different danwei are variable, sometimes dramatically so, although the employees do essentially the same work. Even if we control for some personal characteristics by statistical methods, for example years of education, danwei still plays a critical role in determining a worker’s earned income and economic welfare. In short, danwei is an important factor for inequality and stratification in China. Danwei can actually be considered a social boundary demarcating payment schemes. Some danwei possess more financial resources while others do not. Although one may still think that inequality resulting from danwei is unfair, many find inequality by danwei acceptable. Because there are boundaries, not everyone can be a member of a certain danwei, so entering a good one is a crucial step in attaining social status in China.

The tradition of merit-based inequality

Based on my study of historical material, I propose that inequality has been an integral part of Chinese culture since ancient times. Theoretical research about this is still preliminary (see Brown and Xie, 2015). To discuss this, I would first put forward several important characteristics of ancient China. These characteristics are not new, but rather are well accepted views among western scholars studying ancient China. Here I merely summarize them.

First, the Chinese Empire was ideally united, meaning that there was only one emperor throughout the empire. Of course, unification is an ideal and exceptions were common, for example, during the period of the Three Kingdoms. But ideally, only one emperor ruled. The ideology of unification has been dominant in China, which is quite different from Europe in that respect.

Second, the Chinese empire had a very large territory and a huge population, and thus a great problem facing the empire was administration. In an age without automobiles, highways, trains, cellphones, internet, and other modern communication and transportation technology, it could easily take several days or even months for an official message or letter to travel from the central government to a local government, and thus it was very difficult to conduct efficient administration. This difficulty was not unique to China, of course, but as difficult as it was, the administration of the Chinese empire was, in effect, accomplished. Today, the U.S. is a strong country with a large territory and a huge population. However, as is well known, the U.S. administration developed under modern social conditions within just a few centuries. The U.S. enjoyed dramatically rapid industrialization and mechanization in the late nineteenth century and began to build railways and automobiles. It stepped into the ranks of the developed countries around the 1930s. After going through two world wars, the U.S. federal government became stronger and stronger, gaining more resources and power over time. In contrast, it is extraordinary, and puzzling, that the ancient Chinese empire, with its very large territory, was governed for about two thousand years without any fundamental change to its basic administrative model, despite dynastic changes.

Third, the bureaucratic system of Chinese civil officials is unique. Although the succession of dynasties depended on the military, the administration of the Chinese empire depended on civil bureaucrats over its long history. This is different from other ancient empires such as the Roman Empire, for example. Throughout Chinese history, scholars or literati could become officials, even high-level ones. Even today, Chinese people expect their children to study hard so as to start a successful administrative career. A Confucian saying states, “A good scholar can become an official.” This is a unique cultural element in China. Compared with administrations in other countries, the Chinese bureaucracy originated earlier and attained a greater scale.

Fourth, except for the emperor, aristocrats had limited privileges, and their positions were not stable. For example, among the seigniors of the early Qing Dynasty, Wu Sangui, the Pingxi Seignior, had not remained in power for one generation before he was eliminated by the central government. In fact, throughout Chinese history, most emperors did not want to give inheritance rights to aristocrats. Except for the emperor himself, no important official positions were historically inherited in China. In contrast, in medieval Europe, official posts could be passed down from one generation to the next. In Europe, an aristocratic title was traditionally passed on to the eldest son so that the family would maintain wealth and puissance. This, however, was not the case in China for several reasons. First, except for the emperor (and very few other posts), official positions were not inherited. Second, the rich usually had many wives or concubines and thus produced many sons, and the sons would then divide family wealth equally. In this way, no matter how powerful the family was, their wealth and puissance would soon be divided up, and there was not much left for direct inheritance after only a few generations. That is to say, one could not count on inheritance as a source of wealth in ancient China (see Ho, 1954). Instead of direct inheritance, a standard method of passing on family advantage was to invest as much as possible in sons so that they would be able to make money themselves in the future. It did not even matter if a young boy had no wealthy father. With family support, a son could become an accomplished scholar, enter officialdom, and then merit promotion and wealth. Therefore, in terms of culture, Chinese society emphasized social mobility, and at least some long-range social mobility did occur (see Ho, 1964), whereas in the West, aristocrats and plebeians were separated into distinct classes by birth. In China, by comparison, from the Qin Dynasty onwards or even as early as the Warring States period, feudalism was abolished. Feudalism is characterized by inherited social status and a rigid system of power succession rather than social mobility or centralized power.

Fifth, in the political system of imperial China, ideology played an important role. Since the Western Han, there has not been any fundamental change in the Chinese political system, its ideological core being based on the doctrines of Confucius and Mencius. I even see the present-day Chinese government as carrying on the tradition of the Chinese Empire from the last two millennia. That is to say, the current political system in contemporary China has been influenced by the legacy of the two-thousand-year-old Chinese political system.

Max Weber was an excellent sociologist, as evidenced by his famous book, Economy and Society (Weber, [1921] 1978). Weber was a German who had never been to China, nor did he understand the Chinese language, but he wrote a good book on the Chinese bureaucracy (Weber 1951). Although mainly based on second-hand materials, Weber analyzed the Chinese situation thoroughly and thoughtfully (see Zhao 2015). In his books, he raised two questions about traditional bureaucracy in imperial China. First, while it seems reasonable to select officials by exams, Weber wondered why the candidates were tested only for knowledge of impractical classics rather than administration skills, such as accounting or management, that were directly related to officials’ duties. Actually, this has not changed. Even now, appointments to government posts in China often require academic degrees, preferably degrees in science or engineering, even though scientific/engineering knowledge is rarely used in such administrative positions.

Weber’s second question concerned the fact that tenure of an appointed local administrator was brief, say, three years, which he regarded as inefficient. In order to work effectively, Weber said, administrators needed to learn about local situation and customs as well as how to get along with local subordinates and population, but just when they obtained this knowledge, they were transferred to another place. Therefore, he concluded that bureaucracy in imperial China was indeed inefficient.

What Weber did not understand was that efficiency was not the most important objective for a regime or dynasty in imperial China. Inefficient as it was, the empire still belonged to the imperial family. What good was high efficiency if the empire was disrupted and fell into the hands of others? Political stability, especially for the central government, was paramount. From this perspective, I argue that the ancient Chinese bureaucracy was successful because it solved the biggest problem of administration: stability. Other than this system, it would be hard to think of any other way of governing such a huge empire under the actual conditions at that time.

Why did the governance of imperial China require a bureaucracy made up of imperially appointed scholars with three-year terms? Let us suppose that a local aristocrat established his power. How could the emperor guarantee his absolute obedience to the central government? How could he make the aristocrat dispatch troops and provide financial support during wartime? How could the emperor ensure his subordinates’ collaboration in infrastructure projects such as digging a canal or building the Great Wall? The emperor could only count on his appointed administrators to go to local places and govern with loyalty to him. Of course, for the actual task of administration, the administrators used their own discretion, since the emperor was too far away to report to and had no idea of actual local situations. Hence, a local administrator in a centralized empire faced circumstances substantially different from those of an aristocrat under feudalism. On the one hand, local administrators were appointed and controlled by the central government, and their further promotion would also be decided by the central government. On the other hand, local administrators had to work for the best interests of the local people in order to be promoted (Brown and Xie 2015). Chinese bureaucracy was a useful innovation for maintaining the empire’s stability. From ancient times to the present day, most Chinese rulers realized that it would be impossible to govern such a vast amount of territory with military power, which was seen as a double-edged sword. Without sufficient power, the military could not be effective. With too much power, the military could rebel. Thus, emperors were rational in relying on civilian scholars, who might be inefficient and pedantic, but not rebellious, rather than on the dangerous military.

How was the Chinese empire governed? It was mainly through the doctrines of Confucius and Mencius—indispensable administrative tools for ancient Chinese emperors. Without them, the bureaucracy would not exist, and the long-term centralized empire would not last. The key point of Confucius’ and Mencius’ doctrines is benevolent governance; the person upon whom power is bestowed should work for the public good. This ideology attracted popular support. For instance, as Mencius put it, “The people are of supreme importance; the altars to the gods of earth and grain come next; last comes the ruler” (Mencius, tr. Lau, 2003 p.159). This passage implies the ultimate purpose of imperial power is to serve the people. However, Mencius believed that in order to serve the people, inequality was justified: “That things are unequal is part of their nature” (Mencius, tr. Lau, 2003 p.62). In the words of modern economics, inequality across persons is a complementary relationship that benefits different parties, while absolute equality will lead to widespread poverty of the entire society. Thus, Mencius said, “If everyone must make everything he uses, the Empire will be led along the path of incessant toil. Hence it is said, ‘There are those who use their minds and there are those who use their muscles. The former rule; the latter are ruled. Those who rule are supported by those who are ruled.’ This is a principle accepted by the whole Empire” (Mencius, tr. Lau, 2003 p.59). He argued that absolute equality requiring everyone to do farm work would not work and would trap everyone in poverty. There are differences among people that need to be taken into account. Persons who are intelligent should take up intellectual work and persons who are not intelligent but physically strong should perform manual labor. This is the division of labor in society. In China, many people have heard and approved of Mencius’ statement regarding those who use minds and those who use muscles. This statement also helps us understand inequality. In Mencius’ view, capable persons should enjoy privilege and govern others, while less capable persons should exert their physical strength and do subordinate work under the authority of the intellectually superior. This is a cooperative relationship accepted by all, even the poor.

Why would the poor also support inequality? There are two reasons in the historical context of China. First, in the political system outlined above, the rich enjoyed the privilege of acting on behalf of the public, including the poor. As a result, the poor were not absolute losers in this arrangement, since the division of labor benefited everyone. This is the ideology termed “paternalism,” which is still prevalent in China today. Second, recall that at least theoretically speaking, privilege and wealth resulted not merely from a person’s birth or ascribed characteristics but from the person’s proven performance and abilities. A person of low social origin might prove capable, or he might raise his son to be capable. Again, although his son might be incapable, his grandson might be raised to be capable; there was always some hope. Hence, Chinese culture encourages people to look forward. Rather than complaining about current conditions, they are encouraged to look towards the future, not only one’s own future, but also that of the next generation. That is to say, Chinese culture tends to push people to chase their future dreams at the expense of present interests and immediate satisfactions. This suggests that it does not matter if an individual’s current condition is not ideal because he or she can hold out hope for the next generation. This is the hope of upward social mobility and opportunities for everyone.

There is a picture book telling the stories of Ouyang Xiu. Such story books are popular in China, and most of them tell stories of successful celebrities in history. Teachers and parents narrate these stories to motivate children, teaching them that no matter how poor a person may be, if he is diligent, he can get anything except the imperial throne. As long as the person studies well, he can earn high official titles, just as Ouyang Xiu became the Minister of Defense. Moreover, the ideal image of a scholar goes beyond being just a good scholar, as he should also be a good administrator (“father and mother of the people”). Why did the public have such expectations for administrators? This was because traditional political ideology in China emphasized benevolent governance. Because officials governed their assigned regions largely independently and autonomously, the selection criteria of administrators were not about administration or management skills, but about virtues.

Of course, it was very difficult to know whether a person was virtuous or not. Many methods for measuring an individual’s qualities were implemented. Criteria included whether the candidate was filial, whether he respected his superiors, whether he obeyed rules, and so on. During the Han Dynasty, “filial and incorrupt” (xiaolian) was the primary criterion in the recommendation system of recruitment and was considered the most fundamental virtue in Confucianism. According to the Analects, “It is rare for a man whose character is such that he is good as a son and obedient as a young man to have the inclination to transgress against his superiors (Confucius, tr. Lau, 1997, p.59). After the Sui Dynasty, a person’s knowledge of the classics became the main criterion in evaluating his virtues. There is some merit in valuing a person’s knowledge of the classics, as it could reveal his basic qualities: intelligence, obedience, respect for the teacher, self-discipline and so on. It is similar to the emphasis on mathematics and scientific knowledge for appointments of administrators in today’s China. Although mathematics and scientific knowledge are not really needed in administrative work itself, persons in charge of making official appointments can draw inferences from a candidate’s education in math and science about whether or not the person is intelligent, obedient, hardworking, and aggressive. It is more a test of virtues, personalities, and non-cognitive skills than of practical knowledge.

As we discussed before, the Chinese empire possessed a vast territory, such that most appointed administrators were assigned to places far from the central capital. Administrators were given autonomous authority over the regions they governed. In such a position, it was a person’s virtue, not his practical skills, that determined whether he was a good administrator—“father and mother of the people.” Officials, especially local administrators, accepted dual accountability, being beholden to both superiors and subordinates (Brown and Xie 2015). Their work was, to a large extent, autonomous. Since the emperor was too far away to control them, the administrators could make decisions by themselves and report back only after decision-making and implementation. What gave ultimate legitimacy to the imperial power? Influenced by the doctrines of Confucius and Mencius, officials believed it was the Mandate of Heaven. Thus, middle-level officials should assist the emperor in realizing the mandate. As a result of believing in the mandate, they were working for the local population, i.e. to provide for their material needs. As substantiation of this, many ancient books contained reports of middle-level officials sometimes disobeying their superiors’ commands because they believed they should respond to their higher obligation as “father and mother of the people,” an obligation in accordance with the emperor’s Mandate of Heaven (Brown and Xie 2015).

Historically, officials at and above the county level were appointed by the imperial court so that their power would come from the central government. Yet, the duty of a county administrator was mainly to serve the local population. This created a situation for potential conflicts, which called for a balance. Sometimes, execution of superiors’ commands might incur a real cost to the interests of the local population. Thus, middle-level officials were always caught in this situation of dual accountability (Brown and Xie 2015). I believe this structural problem to be the main cause for a commonly-observed phenomenon even today, which is that officials often conceal some facts from both their superiors and their subordinates. Administrators cannot disclose complete information to either side due to their structural difficulties. Officials sometimes cannot tell the truth, or they risk losing their positions. The mutually constrained bureaucratic system had a history of two thousand years in China. In it, administrators did not have much freedom, as they were squeezed by their responsibilities to both their superior and their subordinates. The primary reason for the Great Famine (1959-1961) was that this balance was broken—the officials were only accountable to their superiors, not to their subordinates.

Officialdom was, and still is, attractive to many people in China. Unfortunately, the Chinese bureaucratic structure makes it necessary for many well-meaning officials to lie. How to solve the problem? Superiors know that subordinate officials lie, so they design many rules by which to supervise subordinates. However, as a common saying goes, “Whenever there is a rule, there is a way to get around it.” Subordinates continually find ways to resist regulation and their superiors’ supervision. The cycles of deception-regulation never end, making administrative procedures more and more complex and cumbersome, and the bureaucracy inefficient.

In the traditional Chinese bureaucracy, an important criterion for evaluating officials was their accomplishments—how well they assisted the emperor in realizing the Mandate of Heaven. To put it more concretely, the criterion was how well the local population under their governance lived. The central government did not care about what officials actually did in their positions. The officials were regarded as good as long as the jurisdiction governed was prosperous, peaceful, and problem-free. Conversely, when problems occurred, even those due to natural causes, officials were to blame, no matter how well they performed or how diligently they worked. If the conditions were good, people would praise the administrator. If there were no natural disasters for years, this would be attributed to Heaven’s appreciation for the administrator. So the notion of accomplishment was important even in ancient times. The emphasis on an official’s accomplishments nowadays is a resurgence of an ancient practice in the Chinese Empire.

In 2007, we conducted a survey in Gansu, an impoverished and remote province. We asked the respondents: what are the most important factors that affect your own economic wellbeing? We provided them with five choices: central government, local government, danwei, family and individual (see Table 2). Although living in remote areas, nearly half of the Gansu respondents chose the central government as their first choice, meaning that they believed the central government was the most important factor determining their economic wellbeing. The second most important factor the respondents gave was the local government. Relatively speaking, personal factors were less important. This illustrates the fact mentioned above that in Chinese culture, the public hold very high expectations for officials and governments regarding their wellbeing.

Table 2.

Attitudes of Residents in Remote Areas on Factors Effecting Personal Economic Welfare Situation (n=633)

| First % | Second % | |

|---|---|---|

| Central Government | 41.61 | 12.03 |

| Local (City/County) Government | 8.54 | 31.33 |

| Danwei or Village Committee | 8.23 | 12.82 |

| Family Factors | 21.33 | 18.8 |

| Individual Factors | 20.38 | 25.28 |

Note: “Now, please consider your economic welfare condition in general. There are many factors influencing an individual’s economic welfare. In your viewpoint and according to your considerations, please rank the following five factors in terms of their importance (which do you think is the ‘most important’, which do you think is the ‘second important’ and so on.)”

We mentioned that a good administrator, as the “father and mother” of the people, sometimes would protect local interests instead of yielding to his superiors. How, then, did the local population encourage administrators to behave in terms of local interests? As we know, appointed administrators were never native, which meant they had few intimate or kinship relationships with local people. A special method used to encourage local accountability in ancient China was the people’s erection of stele monuments (and sometimes even temples and shrines) to record officials’ contributions to the locale, such as construction of roads and bridges, defeating bandits, and so on. In the eulogies on stele inscriptions, administrators’ achievements were praised extravagantly. People in the district could see these steles by the wayside, before crossing a bridge, or within shrines, and officials were also happy to see them. Steles were erected not only for dead administrators, but also for live ones. As a reflection of public opinion, the steles helped officials to secure promotions (Brown and Xie, 2015). In short, although ancient China was not a democracy, local groups utilized reputational mechanisms to influence administrators to serve their interests. On the one hand, this helped satisfy administrators’ own desires for promotion; on the other hand, it motivated them to conduct themselves in ways that would benefit the local population.

Inequality as a by-product of Chinese economic development

At the beginning of China’s economic reform, the Chinese government popularized the idea that economic growth requires that a small number of people to first become rich. Of course, such propaganda was intended to persuade the public to accept inequality as one cost of economic development. In my view, a large number of Chinese today have embraced this belief.

In our study on beliefs concerning the relationship between development and inequality in China, we formulated a hypothesis we called “societal projection” (Xie et al. 2012). The premise of this hypothesis was that the public in a given country generally do not know much about complex social conditions in other countries, since most have never traveled abroad, and even those who have traveled abroad have only had a cursory glance at the foreign countries they visited. To understand a society in depth is not easy, and ordinary Chinese are no exception in not knowing much about the level of inequality and other intricate features of foreign countries. They may have a rough idea about the developmental level of different countries, based on information transmitted through popular media. When asked about the level of inequality in other countries, however, ordinary people in China still show an understanding that is speculative rather than fact-based. In our survey, respondents could tell the level of development when asked which country was developed and which one was not. However, when asked about the level of inequality, although they did not know the actual answers, they would make up answers based on their own models of the relationship between economic development and inequality.

These data come from our survey of nearly 5000 respondents in six provinces (Beijing, Hebei, Qinghai, Hubei, Sichuan, and Guangdong) in 2006 (Xie and Wang, 2009; Xie et al. 2012). The interviewer asked the respondent to rate the level of development in five countries using a scale from zero to ten: China, Japan, Brazil, the United States, and Pakistan, with 10 representing the most-developed and 0 representing the least-developed country. The respondents were also asked to rate the level of inequality for the same five countries on a 0-10 scale, with 10 representing the most unequal and 0 representing the least unequal country. We then compared our survey results with statistical indicators from social science research reported by the United Nations (UN) that measure comparative levels of development and inequality across countries, as shown on Table 3. The first column shows the UN ratings of development and the second column shows our respondents’ average ratings of development. Our respondents rated the U.S. far ahead of the rest in development, with a score of 9.19, and Japan in second place. Here, the statistical results of our survey closely resemble the UN ratings, except for an underestimation by our respondents of the level of development in Japan. However, the relative pattern holds true, with the U.S. and Japan ahead of other countries. After them are China and Brazil, with similar scores according to both the respondents’ ratings and the UN indicators. In last place is Pakistan, which is also in accordance with the UN ratings. Of course, subjective ratings are never precise, so we do not expect exact matches between UN ratings and ratings of our respondents in the survey.

Table 3.

Respondents’ Ratings of Five Countries on Levels of Development and Inequality, in Comparison to UN Ratings.

| Country | UN Rating of Development (0-1) | Average Rating of Development (0-10) | UN Rating of Inequality (Gini, 0-1) | Average Rating of Inequality (0-10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 0.768 | 5.56 | 0.447 | 6.25 |

| Japan | 0.949 | 7.79 | 0.249 | 5.92 |

| Brazil | 0.792 | 5.49 | 0.580 | 5.47 |

| U.S. | 0.948 | 9.19 | 0.408 | 6.81 |

| Pakistan | 0.539 | 3.80 | 0.306 | 5.07 |

Source: Xie and Wang (2009).

Before I explain the rating results on inequality from the survey, let me describe the actual condition of inequality in these countries. One of the most unequal countries in the world is Brazil. Brazil has an internationalized economy with relatively low overall educational attainment, so returns to education are high, which increases social inequality. In addition, with its large size, Brazil suffers from large regional disparity. Between China and the U.S., inequality is higher in the former than in the latter. Pakistan has a low level of inequality, and Japan has the lowest inequality in the group.

How, then, did the respondents form their rating opinions on the level of inequality in our survey? A general analysis of the subjective ratings shows that the respondents believed that inequality is higher in the United States than in China. They considered the level of inequality high in Japan but lowest in Pakistan (see Table 3). It is worth noting that the respondents rated the level of inequality in Brazil as low, which contradicts the ratings provided by the UN. As described above, the respondents were able to accurately rate the levels of development in these countries, but they were not knowledgeable about the levels of inequality, about which their ratings were clearly at odds with the UN’s objective indicators. An interesting question, however, is why ordinary Chinese rated inequality in these five countries in the particular ways that they did.

China has been undergoing multiple dramatic transformations, including a transformation from being underdeveloped to being relatively developed economically, and from being relatively equal to being unequal in the distribution of income. Before the economic reform, people were relatively poor but equal. Nowadays, as China has become more developed, inequality has also risen. Perhaps many Chinese believe a rise in inequality always accompanies economic development, and thus the current level of inequality in the U.S. represents China’s future. They believe that even at its current high level of inequality China is only halfway through development. If China ever catches up with the U.S., it will experience even more inequality. Because the U.S. is more developed than China, they believe the U.S. to be more unequal. We also asked in the survey whether developed countries have higher levels of inequality than less developed ones, and most of the respondents agreed that they do.

We then conducted a statistical analysis of the response patterns to development ratings after rank-ordering the numerical responses, that is, ranking which country is the most developed, which one is the second most developed, and so on (see Table 4). In the first prevalent pattern, the U.S. is at the top, followed by Japan, Brazil, China and Pakistan. 34.11% of the respondents chose this response pattern. The second pattern exchanged the ranks of Brazil and China and was chosen by 33.96% of the respondents. The third pattern is, in descending order, Japan, the U.S., Brazil, China and Pakistan, but only 2.18% of the respondents chose this one. The fourth pattern is similar to pattern three but with the ranks of Brazil and China switched. Of all the respondents, 71.62% fall into these four patterns. Other rank-ordered combinations are irregular and uninterpretable, which can be viewed as measurement errors. With these rank-ordered data, we hope to investigate the relationship between the response patterns in inequality ratings and response patterns in development ratings (see Table 5). Our analysis reveals that they are significantly associated. There is a positive correspondence between responses on the inequality scale and the same person’s responses on the development scale (see lines 1-4 of Table 5). There is also a negative correspondence pattern showing that some respondents’ inequality ratings correspond exactly to the opposite pattern on their development ratings for the same countries. For example, if respondents ranked the development levels as U.S., Japan, Brazil, China and Pakistan from high to low, they ranked the inequality levels in the opposite direction as Pakistan, China, Brazil, Japan and the U.S. from high to low (see lines 6-9 of Table 5).

Table 4.

Main Response Patterns of Development Rating

| Pattern Number | Description of Ranking Order | Percentage | Cumulative Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | US≧Japan≧Brazil≧China≧Pakistan | 34.11 | 34.11 |

| 2 | US≧Japan≧China≧Brazil≧Pakistan | 33.96 | 68.07 |

| 3 | Japan≧US≧Brazil≧China≧ Pakistan | 2.18 | 70.25 |

| 4 | Japan≧US≧China≧Brazil≧ Pakistan | 1.37 | 71.62 |

| 5 | All 116 Remaining Other Combinations | 28.38 | 100.00 |

Source: Xie and Wang (2009).

Table 5.

Main Response Patterns of Inequality Rating by Response Patterns to Development Rating

| No. | Inequality Response Pattern | Response Pattern to Development Rating | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Description | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | US≧Japan≧Brazil≧China≧Pakistan | 25.58 | 8.32 | 6.67 | 3.03 | 8.42 | 14.13 |

| 2 | US≧Japan≧China≧Brazil≧Pakistan | 7.43 | 31.31 | 4.76 | 16.67 | 9.96 | 16.33 |

| 3 | Japan≧US≧Brazil≧China≧ Pakistan | 0.43 | 0.67 | 8.57 | 3.03 | 0.29 | 0.69 |

| 4 | Japan≧US≧China≧Brazil≧ Pakistan | 0.30 | 0.61 | 11.43 | 4.55 | 0.44 | 0.50 |

| 6 | Reverse of Pattern 1 | 12.61 | 3.55 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.51 | 6.75 |

| 7 | Reverse of Pattern 2 | 3.59 | 10.28 | 5.71 | 4.55 | 2.20 | 5.53 |

| 8 | Reverse of Pattern 3 | 1.64 | 0.49 | 12.38 | 3.03 | 0.44 | 1.16 |

| 9 | Reverse of Pattern 4 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 9.09 | 0.37 | 0.64 |

| 10 | All 112 Remaining Combinations | 47.81 | 44.16 | 50.48 | 56.06 | 74.38 | 54.28 |

Source: Xie and Wang (2009).

In brief, we found that the Chinese respondents’ ratings of levels of development for the five different countries closely resembled the ratings given by the United Nations with slight underratings for Japan and Brazil, particularly for Japan. However, the respondents’ ratings of inequality levels in the five countries were not at all in accordance with the inequality statistics reported by the UN, perhaps because many respondents had derived their ratings of inequality from their ratings of development. How do ordinary Chinese view the relationship between economic development and social inequality? Some see a positive relationship, but a smaller number see a negative one. In China’s own experience in its recent history, development and inequality have risen together. That is to say, increases in economic growth and social inequality have been simultaneous. Thus, the prevalent opinion is a positive correlation between the two. The result reflects the recent experience of China and the government’s propaganda. This result also supports the argument that, to many Chinese, inequality is a necessary cost for economic development.

3 Conclusion

In this paper, I set forth three propositions. First, collective agencies play a large role in generating and maintaining inequality in China. Due to the existence of collective agencies as a mechanism for generating and maintaining inequality, the boundary of inequality is structural rather than personal. As a result, the saliency of inequality is low in daily life, which helps to lessen social resentment in the general population. Second, in terms of ideology, although there is a strong moral imperative for equality in China (Wu, 2009), Chinese traditional culture is actually tolerant of inequality. Of course, in my view, people’s acceptance of inequality is conditional on the proposition that inequality should bring welfare to the general public and that everyone has the opportunity to achieve higher socio-economic status through individual effort. Influenced by Chinese traditional culture, many Chinese today find inequality acceptable. Third, some Chinese believe that economic growth itself leads to inequality, which is an inevitable byproduct of economic development. Therefore, persons unhappy with inequality in China can also tolerate it passively and reluctantly, because they still benefit personally from economic development and would favor China further developing its economy. Based on these three considerations, I conjecture that the problem of inequality itself alone will not cause social instability in China in the near future. In other words, although inequality in China has been increasing, its threat might be exaggerated. In my view, there are certain mechanisms (e.g., politics, culture, public opinion, family, social network, etc.) moderating the potential social problems created by inequality.

Acknowledgments

This article was originally published in Chinese in Shehui≪社会》, 2010, 30(3):1-20. I am grateful to Yan Bennett, Miranda Brown, Siwei Cheng, Cindy Glovinsky, Jingwei Hu, Nan Hu, Guoying Huang, Qing Lai, Zheng Mu, Sha Ni, Liguo Peng, Xi Song, Tao Tao, Xiwei Wu, and Jia Yu, for their constructive comments on the paper.

References

- Brown M, Xie Y. Between heaven and earth: Dual accountability in Han China. Chinese Journal of Sociology. 2015;1(1):56–87. [Google Scholar]

- China Statistical Information Network. 2011 Available at: http://www.tjcn.org/plus/list.php?tid=5 (accessed 1 September 2011)

- Confucius . The Analects. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1997. [Lau DC, translator] [Google Scholar]

- Han W. The evolution of income distribution disparities in China since the reform and opening-up. In: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, editor. Income Disparities in China: An OECD Perspective. Paris: OECD; 2004. pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser S, Xie Y. Temporal and regional variation in earnings inequality: Urban China in transition between 1988 and 1995. Social Science Research. 2005;34:44–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hvistendahl M. The numbers game. Science. 2013;340:1037–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.340.6136.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho P. The salt merchants of Yang-Chou: A study of commercial capitalism in eighteenth century China. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 1954;17:130–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ho P. The Ladder of Success in Imperial China: Aspects of Social Mobility, 1368-1911. New York: Columbia University Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Mencius . Mencius. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 2003. [Lau DC, translator] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal J. Wealth gap creating a social time bomb. The Guardian; 2008. Oct 23, Available at: http://www.guardiannews.com (accessed 28 March 2008) [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. Boundaries and Categories: Rising Inequality in Post-Socialist China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weber M. The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism. Glencoe, IL: Free Press; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Weber M. In: Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Roth G, Wittich C, editors. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1978. [1921] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte M. Myth of the Social Volcano: Perceptions of Inequality and Distributive Injustice in Contemporary China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Institute for Development Economics. Research of the United Nations University (UNU-WIDER) Database. Available at: http://www.wider.unu.edu/research/Database/en_GB/wiid/ (accessed 5 October 2012)

- Wu X. Income inequality and distributive justice: A comparative analysis of mainland China and Hong Kong. The China Quarterly. 2009;200:1033–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Treiman D. The household registration system and social stratification in China: 1955-1996. Demography. 2004;41:363–384. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y. Evidence-based research on China: A historical imperative. Chinese Sociological Review. 2011;44(1):14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Hannum E. Regional variation in earnings inequality in reform-era urban China. American Journal of Sociology. 1996;101:950–992. [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Lai Q, Wu X. Danwei and social inequality in contemporary urban China. Sociology of Work. 2009;19:283–306. doi: 10.1108/S0277-2833(2009)0000019013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Thornton A, Wang G, Lai Q. Societal projection: Beliefs concerning the relationship between development and inequality in China. Social Science Research. 2012;41:1069–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Wang G. Chinese people’s beliefs about the relationship between economic development and social inequality. Population Studies Center, University of Michigan; 2009. (Research Report 09-681). [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Wu X. Danwei profitability and earnings inequality in urban China. The China Quarterly. 2008;195:558–581. doi: 10.1017/S0305741008000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Zhou X. Income inequality in today’s China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 2014;111:6928–6933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403158111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D. Max Weber and patterns of Chinese history. Chinese Journal of Sociology. 2015;1:201–230. [Google Scholar]