Older people with epilepsy are more likely to suffer from dementia, while individuals with dementia are at higher risk of developing epilepsy. Sen et al. consider common mechanisms that might underlie the cognitive deficits observed in both groups by examining findings from epidemiological, neuropsychological, molecular, electrophysiological and brain imaging perspectives.

Keywords: neuropsychology, cognitive function, brain imaging, electrophysiology

Abstract

With advances in healthcare and an ageing population, the number of older adults with epilepsy is set to rise substantially across the world. In developed countries the highest incidence of epilepsy is already in people over 65 and, as life expectancy increases, individuals who developed epilepsy at a young age are also living longer. Recent findings show that older persons with epilepsy are more likely to suffer from cognitive dysfunction and that there might be an important bidirectional relationship between epilepsy and dementia. Thus some people with epilepsy may be at a higher risk of developing dementia, while individuals with some forms of dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, are at significantly higher risk of developing epilepsy. Consistent with this emerging view, epidemiological findings reveal that people with epilepsy and individuals with Alzheimer’s disease share common risk factors. Recent studies in Alzheimer’s disease and late-onset epilepsy also suggest common pathological links mediated by underlying vascular changes and/or tau pathology. Meanwhile electrophysiological and neuroimaging investigations in epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia have focused interest on network level dysfunction, which might be important in mediating cognitive dysfunction across all three of these conditions. In this review we consider whether seizures promote dementia, whether dementia causes seizures, or if common underlying pathophysiological mechanisms cause both. We examine the evidence that cognitive impairment is associated with epilepsy in older people (aged over 65) and the prognosis for patients with epilepsy developing dementia, with a specific emphasis on common mechanisms that might underlie the cognitive deficits observed in epilepsy and Alzheimer’s disease. Our analyses suggest that there is considerable intersection between epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular disease raising the possibility that better understanding of shared mechanisms in these conditions might help to ameliorate not just seizures, but also epileptogenesis and cognitive dysfunction.

Introduction

Around 65 million people worldwide have epilepsy, with ∼80% living in developing regions (Birbeck, 2010; Ngugi et al., 2010). In the UK >600 000 people, i.e. almost 1 in 100 (Joint Epilepsy Council, 2011) and in the USA >3 million people or 0.84 in 100 (Helmers et al., 2015) have the disorder. Several studies have consistently shown that the peak incidence is higher in the older population, rising from the age of 65 (Annegers et al., 1999; Hussain et al., 2006). In fact ∼25% of new-onset epilepsies are diagnosed after this age (Joint Epilepsy Council, 2011). Given that the global population aged >65 will increase by ∼400 million to reach almost 1 billion by 2030, the number of older adults with epilepsy is expected to rise substantially.

The population of older adults with epilepsy (defined here as >65 years) consists of two main groups: those who have had epilepsy for many years and, owing to improvements in healthcare, are now living to older age, and those who develop epilepsy de novo in later life. While several underlying causes may contribute to new-onset epilepsy in the elderly (Stefan, 2011) cerebrovascular disease accounts for 50–70% of cases and is the single most common cause (Brodie et al., 2009; Choi et al., 2017). Recent work from the USA has reported that the incident risk for epilepsy is highest in people with cerebrovascular disease aged 75–79, with African Americans at particularly high risk (Choi et al., 2017). The incidence of epilepsy was highest of all in older patients who had experienced a stroke. Others have shown that in the first year after a stroke the risk of developing epilepsy can increase 20-fold (Brodie et al., 2009). The exact pathophysiology of stroke-related epilepsy is not established, but intracerebral haemorrhage, haemorrhagic transformation of ischaemic stroke, greater stroke severity, cortical involvement and venous sinus thrombosis all increase the risk of seizures (Conrad et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014).

Older people who experience head trauma are also around 2.5 times more likely to develop post-traumatic epilepsy than their younger counterparts and up to 20% of epilepsy in the elderly may be attributable to head injury (Annegers et al., 1998; Bruns and Hauser, 2003). Dementia and neurodegenerative disorders account for a further 10–20% of late-onset cases of epilepsy (Stefan, 2011), with much of the research to date focusing on Alzheimer’s disease. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease aged ≥65 years have up to a 10-fold higher risk of epilepsy (Hommet et al., 2008; Pandis and Scarmeas, 2012). Other causes of dementia have received far less attention, but one large study in the UK reported that in people over 65, individuals classified as having vascular dementia had a similar likelihood of developing seizures or epilepsy as those with Alzheimer’s disease (Imfeld et al., 2013).

Importantly, some findings also suggest that older patients with epilepsy are at a higher risk of developing cognitive impairment and ultimately dementia (van Duijn et al., 1991; Breteler et al., 1995). Why should that be the case? In this review we consider whether seizures promote dementia, whether dementia causes seizures, or if common underlying pathophysiological mechanisms are responsible for both. First, we consider the evidence regarding cognitive function and the potential higher risk of dementia in older patients (aged >65 years) with epilepsy. We then turn to findings that suggest there might be a bidirectional link between epilepsy and dementia such that patients with dementia also seem to be at greater risk of developing seizures (Subota et al., 2017). We discuss the evidence for common lifestyle and vascular risk factors in epilepsy and dementia, and then consider potential shared molecular links, including new evidence for tau pathology in older patients with epilepsy (Sen et al., 2007a; Thom et al., 2011; Tai et al., 2016). Finally, we examine emerging evidence which suggests that widespread, brain network changes in Alzheimer’s disease (with our without concomitant vascular pathology) and epilepsy might contribute to cognitive dysfunction in these conditions (Wandschneider et al., 2014; Canter et al., 2016; Palop and Mucke, 2016; Chong et al., 2017), including the remote effects of interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs) (Kleen et al., 2013; Gelinas et al., 2016; Ung et al., 2017).

Our review of these disparate findings leads to the conclusion that although current data do not allow us to make definitive mechanistic inferences, they do show that this is an important area for investigation that has potential application to both patients with epilepsy and dementia. It is now well established that many patients who are diagnosed clinically to have Alzheimer’s disease have mixed pathology with concurrent cerebrovascular changes at post-mortem, and vice versa (Rahimi and Kovacs, 2014). Thus, targeting lifestyle and vascular risk factors might offer important therapeutic opportunities to modify the disease processes underlying these conditions as well as the progression of cognitive decline in people with epilepsy

Cognitive function in older patients with epilepsy

Studies of cognitive impairment in older patients with epilepsy

There are surprisingly few systematic studies that have addressed the issue of cognitive function specifically in the elderly epilepsy population (Martin et al., 2005; Griffith et al., 2006, 2007; Piazzini et al., 2006; Witt et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2016). Most of these are cross-sectional investigations that tested small samples of patients with young-onset epilepsy (Table 1), with only one study that has reported on late-onset epilepsy (Witt et al., 2014). Nevertheless, the work that has been published indicates that overall older adults with epilepsy have greater deficits compared to healthy older people across cognitive domains, but especially in short and long-term visual and verbal memory, executive functions, attention and psychomotor, or processing speed.

Table 1.

Results of studies of cognitive impairment in older patients with epilepsy

| Study and sample | Cognitive domains | Neuropsychological tests | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Global cognitive functioning | Mattis DRS |

|

| Immediate and long-term memory | Logical Memory: Immediate and Delayed recall subtests from the WMS-III | ||

| Verbal fluency | COWAT | ||

|

Global cognitive functioning | Mattis DRS |

|

| Immediate and long-term memory | Logical Memory: Immediate and Delayed recall subtests from the WMS-III | ||

| Lexical ability | CFL word fluency test | ||

|

Global cognitive functioning | Mattis DRS | General stability in neurocognitive performance for patients with epilepsy after 3 years, although their performance continued to be below that of matched healthy adults |

| Immediate and long-term memory | Logical Memory: Immediate and Delayed recall subtests from the WMS-III | ||

| Lexical ability | COWAT | ||

| Executive control. | Executive Interview Test (EXIT-25) | ||

|

Intelligence | Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices |

|

| Selected and divided attention | Trail Making Test | ||

| Abstraction | Attentional Matrices | ||

| Short and long-term verbal and visual memory |

|

||

| Learning | Digit Span | ||

| Language | Verbal Fluency Test | ||

| Aphasia | Token Test | ||

|

Executive function | EpiTrack | Objective impairment in executive functions before initiation of AEDs treatment |

| Quality of life | Quality of Life in Epilepsy (QOLIE)-31 | ||

| Subjective ratings of cognition | Portland Neurotoxicity Scale (PNS) | ||

|

Global cognition |

|

|

| Verbal memory |

|

||

| Visual memory |

|

||

| Attention / psychomotor speed | Digit symbol coding | ||

| Executive function |

|

||

| Language |

|

||

| Visuospatial |

|

||

COWAT = Controlled Oral Word Association Test; DRS = dementia rating scale; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; WMS-III = Wechsler Memory Scale.

One study has documented the severity of cognitive deficits in a large group (n = 257) of older people [mean age: 71.5, standard deviation (SD) 7.2] with new-onset focal epilepsy who were assessed before initiation of anti-epileptic drug (AED) treatment (Witt et al., 2014). Approximately one-third (n = 88) had suffered a cerebral infarct and another third (n = 99) had cerebrovascular disease. Over 80% (n = 209) suffered from focal seizures with impairment of awareness and just over 50% (n = 139) suffered generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Cognitive function was tested using a screening tool specifically designed to detect and monitor executive function in patients with epilepsy (EpiTrack). This includes tests of response inhibition, visuomotor speed, mental flexibility, visuomotor planning, verbal fluency and working memory (Lutz and Helmstaedter, 2005). Performance was compared to age-corrected norms from 689 healthy control subjects. In addition, participants also completed the Portland Neurotoxicity Scale (PNS), a patient-based survey of cognitive and somatomotor symptoms and the Quality of Life in Epilepsy (QOLIE)-31 questionnaire.

The results revealed that many older individuals with new-onset focal epilepsy were cognitively impaired before initiation of AEDs, with 43% markedly affected, 35% were unimpaired while 6% scored above average. Greater deficits were associated with cerebral infarction or cerebrovascular aetiology, neurological comorbidity and higher body mass index. Subjective performance ratings indicated limited insight into cognitive impairments. These findings underline the importance of early cognitive screening to obtain a baseline assessment allowing quantification of any decline and to evaluate effects of subsequent pharmacological treatment. Overall, the limited existing studies on this topic show that older individuals with epilepsy appear to have significant deficits in cognitive function across the board.

Accelerated long-term forgetting

In addition to systematic studies of cognitive function, there is also evidence of accelerated long-term forgetting in one group of patients with epilepsy, namely individuals with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). In this condition, memories appear to be normally encoded but are retained for only short intervals of time: weeks, days or even less (Martin et al., 1991; Elliott et al., 2014). Accelerated long-term forgetting, specifically in older patients with epilepsy, has not been characterized in great detail and is difficult to interepret in the context of the controversial literature on the effects of normal ageing on forgetting (Elliott et al., 2014). However, one group of patients in which accelerated long-term forgetting has been reported in an older age group (mean age of onset = 57 years) is those with transient epileptic amnesia (Manes et al., 2005; Butler et al., 2007; Butler and Zeman, 2008). In transient epileptic amnesia, amnestic episodes usually last less than 1 h, may be accompanied by olfactory hallucinations and automatisms and brief loss of responsiveness, and the EEG often indicates medial temporal lobe dysfunction (Butler et al., 2007).

Patients experience a panoply of symptoms that often occur on awakening such as brief recurrent episodes of mixed anterograde and/or retrograde amnesia; difficulty in forming new memories; and in remembering events that occurred in the hours prior to the onset of the attack. Other cognitive functions have been reported as unaffected during typical episodes (Butler and Zeman, 2008). Scores on tests of general intelligence, language, executive function and visuospatial perception are also usually not significantly different from healthy people (Butler et al., 2007). Patients with transient epileptic amnesia can also experience topographical amnesia: loss of spatial memory with difficulty recalling routes or places. In addition, they typically report a remote memory impairment, in which there is loss of memories for relevant autobiographical events in the more distant past (Butler and Zeman, 2008). Whether accelerated long-term forgetting and/or remote memory impairment might predispose to development of dementia remains to be definitively determined, but data on progression of cognitive deficits are perhaps strongest for those with TLE, as discussed in the next section.

Progression of cognitive deficits in younger-onset epilepsy patients

Several investigations have now also reported that there is progression of cognitive deficits over short periods of time (3–4 years), in younger adults (<65 years old) with epilepsy (reviewed in Dodrill, 2004; Seidenberg et al., 2007). The most extensively studied group is patients with TLE in whom it is now apparent that there are widespread brain structural changes beyond the medial temporal lobes (Keller and Roberts, 2008; Bell et al., 2011; Dabbs et al., 2012; Caciagli et al., 2017) and that progression of cognitive impairment over time may occur in a significant proportion (Hermann et al., 2006). While cognitive reserve (Hermann et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2012)—indexed by baseline IQ, years of education or occupational complexity—may mitigate some of these effects, duration of epilepsy appears to be an important factor in determining progression of cognitive impairment (Hermann et al., 2006; Seidenberg et al., 2007).

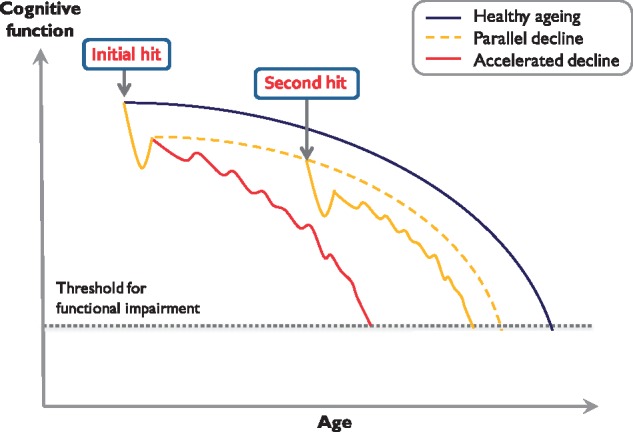

Whether the progression represents genuine accelerated ageing over time (Seidenberg et al., 2007; Sung et al., 2013) or simply the initial ‘hit’ of epilepsy having a negative neurodevelopmental impact (Helmstaedter and Elger, 2009) is a matter of considerable debate (Lin et al., 2012; Breuer et al., 2016). According to one view of accelerated ageing, the trajectory of cognitive decline with ageing in people with epilepsy deviates further from that in healthy individuals as time passes (Fig. 1). That is to say, there is continued cognitive decline over time or progression (Seidenberg et al., 2007). This might be due to chronic accrual of underlying pathology (e.g. vascular) and/or the effects of epilepsy itself (ongoing overt seizures or interictal epileptiform discharges, IEDs). However, an alternative view is that an initial insult to the brain means that, in patients with epilepsy, cognitive decline simply runs below, but parallel to, the normal trajectory of cognitive change with ageing (Fig. 1). These individuals therefore start from a lower point and therefore reach thresholds for significant cognitive and functional impairment earlier than those without seizures (Helmstaedter and Elger, 2009). Others suggest there may be a ‘second hit’. According to this latter view some disruption to the brain (e.g. traumatic brain injury) or pre-existing brain abnormality represents the first hit on cognitive function, but subsequent development of epilepsy is effectively a ‘second hit’ that leads to further deviation from the normal trajectory of cognitive decline with ageing (Fig. 1) (Breuer et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

Trajectories of cognitive decline with ageing. The schematic illustrates how cognitive function in people with epilepsy might decline compared to healthy ageing (blue). One model proposes that an initial brain insult (‘initial hit’) leads to cognitive decline in epilepsy patients simply running parallel to but below the normal trajectory (dashed yellow). These individuals start from lower cognitive performance and also reach the threshold for functional impairment or dementia earlier. An alternative model is that while an initial hit might be a neurodevelopmental disorder or traumatic brain injury, subsequent development of epilepsy is in effect a ‘second hit’, which leads to further deviation from the normal trajectory (solid yellow). A third proposal is that, with increasing time, the trajectory of cognitive decline in people with epilepsy deviates further from that in healthy individuals leading to accelerated cognitive ageing (red). Inspired by a figure used by Breuer et al. (2016).

Evidence for progression of cognitive decline in epilepsy comes from a relatively small number of longitudinal studies in which the majority of patients had focal seizures, mostly TLE, with many being associated with evolution to bilateral tonic clonic seizures (Seidenberg et al., 2007). In addition, most of these studies examined people who at baseline had a mean age of 31–37 years and were followed-up between 1 and 13 years. One investigation has reported on a small sample (n = 17) of older individuals who at baseline had a mean age of 64 years and were followed up 2–3 years later (Griffith et al., 2007). In this study, participants were also assessed with the Executive Interview Test (EXIT-25) to assess executive function. Overall, cognitive deficits did not worsen in this group, although performance continued to be below that of matched healthy older adults. However, delayed logical memory showed a significantly deleterious trajectory. In addition, performance on the EXIT-25 also worsened, suggesting that older adults with epilepsy might experience greater decline in executive function over time.

A recent study by Breuer and co-workers screened 287 adult patients for cognitive deterioration compared to expected premorbid IQ (defined as ≥1 SD discrepancy between actual WAIS IQ and estimated premorbid IQ) (Breuer et al., 2017). A group of 27 individuals fulfilled the criteria (mean age: 55.7; mean seizure duration: 21.8 years). More than 77% of them had associated comorbidities (including 52% cardiovascular, 14% cerebrovascular and 24% traumatic brain injury). Analyses revealed that the most prominent factors that accounted for the variance in cognitive deterioration were those that might impact on cognitive reserve: low premorbid IQ and education level, later age of seizure onset and older age (Breuer et al., 2017). These findings would be consistent with a double hit model in which pre-existing low brain reserve makes the brain more vulnerable to a second hit from the development of epilepsy.

Hermann et al. (2007) sought to apply a taxonomic classification to the cognitive impairments in TLE by comparing 96 TLE patients with 82 healthy control participants. Using cluster analysis, they found that although all patients with TLE were impaired compared to controls, they could be further segregated. One group had minimal impairment (47%; although delayed memory, language, executive function and psychomotor processing speed were still significantly lower than controls). A second group had marked memory difficulties and evidence of relatively mild cognitive dysfunction across other domains (24%). Finally, a third group showed a global pattern of cognitive difficulties (29%; significantly poorer performance than controls and the first and second groups). Patients in this group had an earlier age of onset, were a little older (thereby indicating a longer duration of epilepsy) and were more likely to be on more AEDs than individuals in the other groups. A subgroup of participants was assessed again after 4 years. All had declined compared to controls, but the deterioration was more marked in Group 3 (Hermann et al., 2007).

The initial work demonstrated that Group 3 had lower cerebral tissue and hippocampal volumes on MRI (Hermann et al., 2007). A follow-up investigation showed that the cognitive subtypes could be differentiated through a wide variety of MRI measures suggesting that widespread neuroanatomical changes might underpin the differing patterns of cognitive deficit (Dabbs et al., 2009). In both studies, the groups were aged 14–59 years. It remains to be established if there are neuroanatomical changes that might delineate differences between patients with, for example, late-onset TLE and memory difficulties compared to a cohort of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Nevertheless, it is clear that there is considerable heterogeneity within even one subgroup of patients with epilepsy. Thus generalizations about ‘single hit’, accelerated ageing and ‘double hit’ models might not be appropriate. Instead, the precise model that might explain cognitive trajectory might vary across individuals.

Epilepsy and dementia in older patients: a bidirectional relationship?

Gowers first introduced the concept of epileptic dementia, implying that dementia and epilepsy might, in some subjects, be the consequence of the same underlying disorder (Gowers, 1881). The higher incidence of cognitive impairment in older people with epilepsy certainly raises questions as to whether these individuals might have increased rates of progression to dementia, particularly those with TLE (Höller and Trinka, 2014). As part of the EURODEM project, eight case-control studies that assessed the risks of developing Alzheimer’s disease in several medical conditions were reanalysed (van Duijn et al., 1991). When compared with population-based controls, individuals with epilepsy had an increased relative risk of being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease at least 1 year after epilepsy diagnosis. The greatest risk for Alzheimer’s disease occurred in patients who had epilepsy for <10 years (relative risk 2.5) versus >10 years (relative risk 1.4). Importantly though, this increased risk appeared not to be related to the cumulative effect of longstanding seizures. A follow-up study based on three nationwide Dutch morbidity registers over the period 1980–89 investigated the risk of dementia for patients aged 50–75 years. Patients with epilepsy were found to have a relative risk of 1.5 of being diagnosed with dementia over an 8-year period (Breteler et al., 1995).

The mechanisms underlying an increased likelihood of developing dementia have not been definitively established. Intriguingly, part of the risk might be attributable to the fact that patients with Alzheimer’s disease and/or vascular dementia are actually more likely to develop epilepsy (Hommet et al., 2008; Imfeld et al., 2013). In a UK study that examined the records of 22 084 patients (mean age ∼80 and half the sample with Alzheimer’s disease), after adjusting for baseline predictors of seizures, Alzheimer’s disease was associated with a significantly increased risk of seizures [hazard ratio (HR) 5.31, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.97–7.10] (Cook et al., 2015). In addition, patients with Alzheimer’s disease were at a higher risk of haemorrhagic stroke (HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.06–2.08), which is an independent risk factor for developing seizures. In Han Chinese patients with Alzheimer’s disease too, the risk of seizures is higher in Alzheimer’s disease than in age-matched controls (HR 1.85; 95% CI 1.40–2.90) (Cheng et al., 2015).

Vascular dementia also increases the risk of seizures. Another large UK population-based study examined the records of 4438 cases with vascular dementia and 7086 patients with Alzheimer’s disease, comparing them to 11 524 dementia-free patients (mean age >80 in the three samples). This reported an odds ratio of developing seizures of 5.7 (95% CI 3.2–10.1) for vascular dementia and 6.6 (95% CI 4.1–10.6) for Alzheimer’s disease (Imfeld et al., 2013). Thus, it might not simply be a case of epilepsy and associated risk factors, increasing the risk of dementia, but dementia—whether in the form of Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia—simultaneously increasing the risk of epilepsy (Helmstaedter and Witt, 2017).

These considerations raise important questions: do seizures cause dementia, does dementia cause seizures, or does something else cause both? Some recent work suggests that epilepsy could be considered a symptom rather than a disease in itself (Helmstaedter and Witt, 2017). It is argued that epilepsy is simply one manifestation of the underlying pathological process that might contribute to seizures, cognitive decline, psychological problems, systemic illness and, perhaps indirectly, psychosocial difficulties. Seizures can, for example, be observed in the prodromal phase of several neurodegenerative illnesses (Cretin et al., 2017), and some studies in patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease have reported that cognitive decline may begin several years earlier in those individuals who suffer from seizures compared to those who do not (Amatniek et al., 2006; Irizarry et al., 2012; Vossel et al., 2013). These findings have led some authors to consider whether there might be analogous processes occurring in patients with TLE who might progress to dementia (Höller and Trinka, 2014).

In patients with familial autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (<50 years old) seizures are far more common than in typical late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, affecting >45% of cases, although rates vary with specific genetic mutations (Zarea et al., 2016). This suggests that younger people with Alzheimer’s disease (aged 50–59) are at highest risk of developing seizures and therefore disease duration might not be crucial (Amatniek et al., 2006). There is also some evidence that epilepsy in typical late-onset Alzheimer’s disease may be associated with faster progression of cognitive decline (Volicer et al., 1995; Amatniek et al., 2006), but large-scale longitudinal studies are required to confirm this. As highlighted in a comprehensive recent systematic review, much more work is needed to fully elucidate the epidemiology of epilepsy in dementia and also of dementia in epilepsy (Subota et al., 2017). It remains unclear whether epilepsy and dementia simply share common risk factors, whether there is truly a bidirectional relationship between the two—or both. In the next section we examine evidence for common risk factors.

Common risk factors for epilepsy and dementia

An important issue in dementia research is detection of disease at an early stage. The use of CSF (e.g. tau and amyloid-β levels) and neuroimaging biomarkers (e.g. hippocampal atrophy on structural MRI, temporoparietal hypometabolism on FDG PET, abnormal amyloid and tau PET imaging) to make the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in the ‘preclinical’ state is one strategy that has gained widespread currency (Jack and Holtzman, 2013; Ahmed et al., 2014). Similarly, the diagnosis of vascular dementia often rests on the presence of evidence of small vessel cerebrovascular change on MRI, while the clinical diagnosis of mixed Alzheimer’s disease/vascular dementia usually occurs when there are biomarkers suggesting the presence of both types of pathology (Harper et al., 2014). Precisely how individuals with epilepsy with preclinical dementia might present or be detected remains to be established (Höller and Trinka, 2014). Indeed, it may well be that biomarkers for dementia in epilepsy might not be unique to people with epilepsy but rather reflect mixed pathologies, e.g. associated with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, as well as perhaps electrophysiological evidence of ongoing overt or covert abnormal electrical activity, e.g. IEDs.

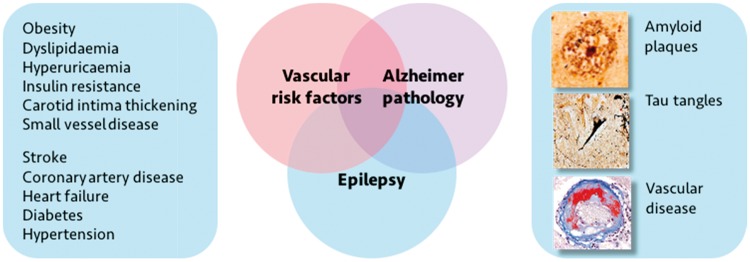

A reason for postulating that this might indeed be the case is that it is increasingly becoming apparent that an important potential explanation for the co-occurrence of both seizures and dementia is that these conditions share common risk factors (Fig. 2). Several features have been associated with accelerated cognitive decline, brain ageing and dementia. These include increased vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, smoking and low exercise, all of which predispose to atherosclerosis; altered lifestyles such as decreased social interaction and physical inactivity; treatment with medications (including some anti-epileptic medications) that adversely affect cholesterol, folate and glucose metabolism; as well as elevated inflammatory markers (Schwaninger et al., 2000; Fratiglioni et al., 2004; Dik et al., 2005; Vezzani and Granata, 2005; Panza et al., 2006; Hamed, 2014).

Figure 2.

The intersections of Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy and vascular disease. Several overlapping pathologies (right) can contribute to development of late-onset epilepsy as well as the development of dementia. In particular, vascular risk factors (left) are common in people with epilepsy. These may represent modifiable risk factors for both the development of dementia and of epileptogenesis.

While many of these are over-represented in patients with epilepsy (Hermann et al., 2008; Hamed, 2014; Keezer et al., 2016), the relationships of these factors to cognitive and brain ageing are only now beginning to be systematically examined. For example, while it has been long recognized that late onset epilepsy associates with an increased risk of stroke (Cleary et al., 2004; Wannamaker et al., 2015), it is only more recently that the extent of cerebrovascular disease has come under scrutiny in this group of patients (Gibson et al., 2014; Hanby et al., 2015).

An important contribution to this area was made by Sillanpää et al. (2015), who followed a cohort of 245 patients with childhood onset epilepsy living in the vicinity of the Turku University Hospital, Finland, for over 50 years. The authors demonstrate that even in ‘uncomplicated epilepsy’, namely patients without major neurological impairment at onset, MRI at 50-year follow-up demonstrated significantly more evidence of cerebrovascular disease than in controls. These findings could not be correlated to lifestyle choices such as smoking, alcohol consumption or physical exercise or to standard vascular risk factors such as hyperlipidaemia, diabetes or hypertension. Even patients with primary generalized epilepsy, most of whom were in terminal remission from seizures, still showed increased markers of cerebrovascular disease on brain imaging. One may speculate from these data that the increased vascular burden may be due to epilepsy itself, be that the underlying aetiology of the epilepsy, consequences of recurrent seizures (for example repeated head injury or bouts of status epilepticus), or chronic exposure to AEDs.

The same group has now also published data from amyloid PET imaging, showing that some of the Turku patients have positive evidence of amyloid deposition, with greater frequency than healthy controls, particularly in prefrontal cortex (Joutsa et al., 2017). Higher amyloid deposition occurred in those individuals who were APOE4 genotype positive—which also puts healthy individuals at greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease as well as vascular dementia (Liu et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015). The impact of these imaging findings on cognition in this valuable cohort awaits further study.

As a corollary to such investigations on young-onset epilepsy cases who were imaged later in life, Maxwell et al. (2013) retrospectively examined 105 older patients with late onset epilepsy or isolated seizures and 105 controls. Radiological evidence of cerebrovascular disease, both large and/or small vessel disease, was more prevalent in people with seizures (Maxwell et al., 2013). Notably, though, the majority of cases and controls had undergone CT brain imaging, potentially reducing the sensitivity of detecting small vessel disease (Maxwell et al., 2013). The same group subsequently went on to examine MRI features of occult cerebrovascular disease in a small cohort of patients with late onset epilepsy and age-matched controls, reporting that the cases with epilepsy had lower cortical volume, especially in the temporal lobes, and an increased volume of white matter hyperintensity. There were additional changes in a measure of arterial arrival time, which led the authors to suggest that occult cerebrovascular disease might therefore contribute to late onset epilepsy (Hanby et al., 2015).

Although this seems plausible, it remains unclear whether modification of vascular risk factors would reduce seizures (beyond the benefit of preventing clinically apparent strokes) and/or mitigate against cognitive decline in patients with epilepsy. The results of a recent study of Seventh Day Adventists and Baptists in Denmark—religious groups that desist completely or refrain from excessive consumption of alcohol and tobacco—demonstrated that there was a reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in these communities, but without any change in the standardized incidence rate of epilepsy (Thygesen et al., 2017). These findings suggest Alzheimer’s disease and seizure incidence can be dissociated, but what is required is a well-designed prospective clinical trial to establish whether tight control of vascular and lifestyle risk factors has an impact upon cognitive decline and incidence of dementia in people with epilepsy. It would also be helpful to disentangle how much of the cognitive deficit observed in an older individual with epilepsy relates to epilepsy (seizures and IEDs) and how much is attributable to underlying pathological changes, including vascular pathology (Hamed, 2014), thereby potentially enabling stratification and appropriate targeting of therapeutics.

Molecular links between epilepsy and dementia in older patients

Another possible explanation for the increased risk of dementia in epilepsy is that some dementia syndromes might also share underlying pathological mechanisms with epilepsy, or that seizures might trigger pathological changes that make the brain more vulnerable to developing dementia pathology. Limited histopathological work has been performed to better delineate these aspects. In their study examining 138 people with chronic epilepsy, Thom et al. (2011) found that there was a higher incidence of cerebrovascular disease in older patients, and a significant correlation with cerebrovascular disease and higher Braak stages of Alzheimer’s disease-type pathology. However, when age was factored out, the association between cerebrovascular disease and Braak stage was no longer significant (Thom et al., 2011). Importantly in this cohort of patients, 30% had evidence of traumatic brain injury and this, rather than the number of seizures, correlated with a higher Braak stage (Thom et al., 2011). Similarly it has long been recognized that traumatic brain injury can increase the rate of dementia (Gualtieri and Cox, 1991). However, how traumatic brain injury, dementia and epilepsy, which may directly cause head injury through a seizure or indeed be a consequence of a previous head injury, intersect remains incompletely determined.

At a molecular level, deregulation of kinases, for example cyclin dependent kinase 5, which is known to be important in Alzheimer’s disease, has been shown in epileptogenic lesions (Sen et al., 2006, 2007b). Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis of tissue from some patients with epilepsy secondary to focal cortical dysplasia reveals aggregation of tau, similar to that in Alzheimer’s disease (Sen et al., 2007a). Such changes in tau aggregation were observed only in the older individuals of this small sample, and were limited to the epileptogenic lesion alone, not being seen in adjacent histologically-normal cortex. In the two oldest patients in the series, 3-repeat (3R) and 4-repeat (4R) tau tangles were detected with a potential increase in the 4R:3R ratio. These two older individuals did also demonstrate amyloid-β positivity. Thus molecular cascades important in both seizure generation and neurodegeneration might converge within epileptogenic tissue in older patients (Sen et al., 2008).

A recent report of patients aged over 50 years undergoing temporal lobectomy for hippocampal sclerosis (n = 33; age 50–65 years) documented that the majority demonstrated abnormal tau immunohistochemistry (Tai et al., 2016). Of the 24 cases with AT8 (a monoclonal antibody that recognizes tau) positivity, 10 had a Braak-like pattern and eight had features more compatible with chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Several cases, though, had unusual patterns of AT8 immunopositivity with, for example, subpial band staining and unusual granulations. The CA1 sector of the hippocampus seemed less involved than in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, although it should be noted that hippocampal sclerosis, the pathology underlying the epilepsy in all resected cases, can result in severe neuronal loss through CA1. Both 3R and 4R isoforms of tau were present. Tau burden correlated with postoperative, but not preoperative, cognitive scores and although it is difficult to infer much from a single case, the patient with the highest burden of tau pathology in resected tissue went on to develop Alzheimer’s disease 9 years after epilepsy surgery.

There has perhaps been less attention given to amyloid-β deposition in patients with epilepsy overall. Increased levels of amyloid-β precursor protein (APP) (Sheng et al., 1994) and age-accelerated presence of senile amyloid plaques (Mackenzie and Miller, 1994) have been observed in temporal lobectomy tissue from older TLE cases and seizures are particularly prevalent in patients with Alzheimer’s disease with APP duplication compared to other dominant Alzheimer’s disease genetic mutations (Zarea et al., 2016). The expression of APP, but not the level of APP mRNA, is higher in temporal lobe and hippocampi from patients undergoing epilepsy surgery compared to controls (Sima et al., 2014). Nonetheless, in human epileptogenic tissue, amyloid-β pathology is not often detected. Notably Tai et al. (2016) found that 28/33 of their relatively older surgical cases did not demonstrate any staining for amyloid-β and in three cases amyloid-β staining was sparse. These data are similar to the earlier study examining post-mortem samples from patients with chronic epilepsy (Thom et al., 2011) where only 34% of 138 patients demonstrated amyloid-β positivity and only 8% of the whole cohort had frequent plaques. Taken together, data from human studies might suggest that chronic temporal lobe epilepsy can associate with a tauopathy and while tau burden may contribute to cognitive difficulties, the molecular mechanisms underlying epilepsy-associated tau pathology might differ from those that drive Alzheimer’s disease.

Animal models of Alzheimer’s disease are also providing possible insights into commonalities of network disruption in Alzheimer’s disease and epilepsy (Scharfman, 2012). Fibrillar amyloid-β can disrupt neuronal membrane properties and trigger epileptiform activity (Westmark et al., 2008; Minkeviciene et al., 2009). Furthermore, in double-transgenic APP23xPS45 mice [which overexpress both APP (APPSwe) and mutant presenilin-1] there is a significant increase in hyperactive neurons, specifically adjacent to amyloid plaques (Busche et al., 2008). This appears to be associated with disruption of the balance of excitation and inhibition at long range, across brain networks (Busche and Konnerth, 2016; Palop and Mucke, 2016). Remarkably, levetiracetam and topiramate, two widely prescribed AEDs, reduced amyloid plaques in this model (Shi et al., 2013). In addition, both AEDs improved spatial memory in the transgenic mice tested on the Morris water maze (Shi et al., 2013).

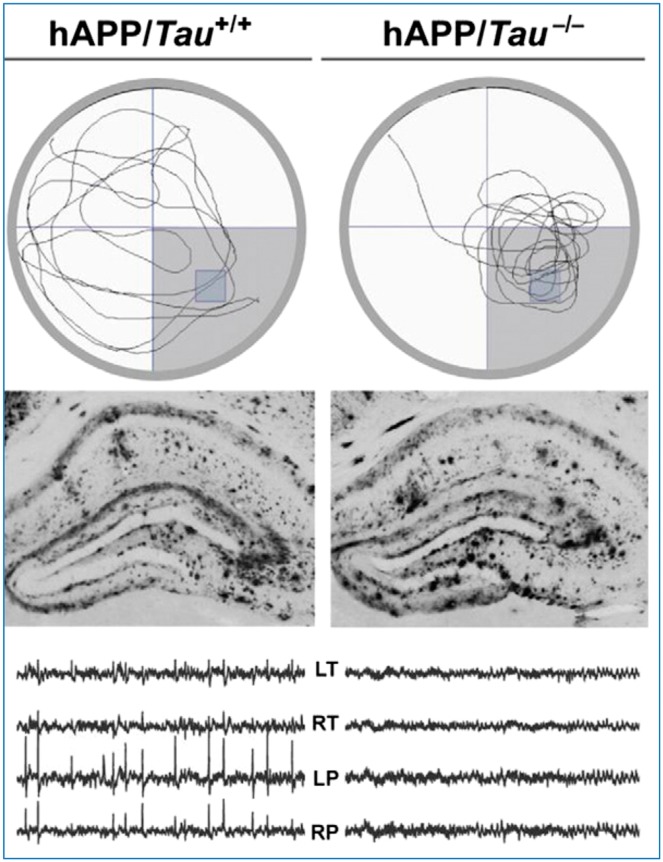

Other recent studies using a different mouse genetic model of Alzheimer’s disease [human APP (hAPP) transgenic] reported that these animals develop abnormal electrical activity in the hippocampus (Sanchez et al., 2012). Further investigations on this animal model have revealed that deficits in spatial memory and abnormal spiking on EEG can be normalized when the mouse is also depleted of tau (by knockout of the tau gene, MAPT), without any effect on amyloid deposition (Roberson et al., 2007) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease shows abnormal spiking. The human amyloid precursor (hAPP) transgenic mouse of model of Alzheimer’s disease shows deficits of spatial memory on the Morris water maze task, taking longer to find the platform (top left) and with abnormal spiking activity over left and right temporal and parietal cortex (bottom left). Reduction of tau by creating a hAPP mouse, which does not produce tau (hAPP/Tau-/-) normalizes both spatial memory and the EEG (top and bottom right, respectively), despite the fact that both models have similar amyloid plaque deposition (middle). Modified with permission from Roberson et al. (2011).

Treatment with levetiracetam—but not other tested AEDs (ethosuximide, gabapentin, phenytoin, pregabalin, valproic acid and vigabatrin)—reduced such aberrant electrical activity, and chronic treatment with levetiracetam actually improved memory performance and behaviour in these mice (Sanchez et al., 2012). Electrophysiological studies in acute hippocampal slices confirmed that levetiracetam reversed deficits in synaptic transmission restoring long-term potentiation curves so that they were no different to that from non-transgenic mice (Sanchez et al., 2012). Importantly, higher doses of levetiracetam were ineffective and once the drug was withdrawn there was recurrence of epileptiform activity with associated return of the behavioural and cognitive deficits. In humans, levetiracetam has also been shown to suppress aberrant hippocampal blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) hyperactivity in amnestic mild cognitive impairment individuals, with associated improvement on an experimental memory task (Bakker et al., 2012), as discussed in more detail below in the ‘Network level effects in epilepsy and dementia’ section.

As an elegant corollary of this work, several groups have investigated whether disruption of tau might have an impact in animal models of genetic epilepsy. For example, Dravet syndrome is a devastating epileptic encephalopathy that associates with mutations in the human SCN1A gene encoding the voltage gated potassium channel subunit Nav 1.1. In the mouse model of Dravet syndrome, deletion of tau alleles decreased the number of seizures and reduced mortality (Gheyara et al., 2014). There was also evidence of improved learning and memory with tau depletion (Gheyara et al., 2014). In Kcna−/− mice, which lack Kv1.1 rectifier currents and whose neurons are therefore hyperexcitable, depletion of tau reduced seizure frequency and duration. While similarly in acquired models of epilepsy, depletion of tau through antisense oligonucleotides reduced the effect of chemoconvulsants (DeVos et al., 2013) and constitutional depletion of tau through genetic deletion prevented deficits in spatial memory and learning after repeated mild head injuries (Cheng et al., 2014). Finally, treatment with sodium selenate, a drug that reduces tau hyperphosphorylation, decreased seizure severity/frequency in three separate rodent models of epilepsy (Jones et al., 2012). Taken together this body of work again illustrates commonality of pathways that may underpin epilepsy and dementia with demonstration that suppression of tau hyperphosphorylation or reduction in seizures of can benefit epilepsy and Alzheimer’s disease, respectively.

Network level effects in epilepsy and dementia

Increasingly, epilepsy is considered to be a brain network disorder, with widespread functional connectivity changes associated with even focal pathologies (Dinkelacker et al., 2016; Englot et al., 2016). Moreover, it is now also appreciated that a major contribution to cognitive impairment in people with epilepsy is seizure activity, regardless of the underlying pathological cause of seizures (Holmes, 2015). In fact, although it has long been acknowledged that status epilepticus or recurrent seizures can impact upon cognition, findings in both animal models and humans demonstrate that interictal spikes or IEDs can also disrupt cognitive function (Kleen et al., 2010, 2013) even if remote to the ictal onset zone (Ung et al., 2017).

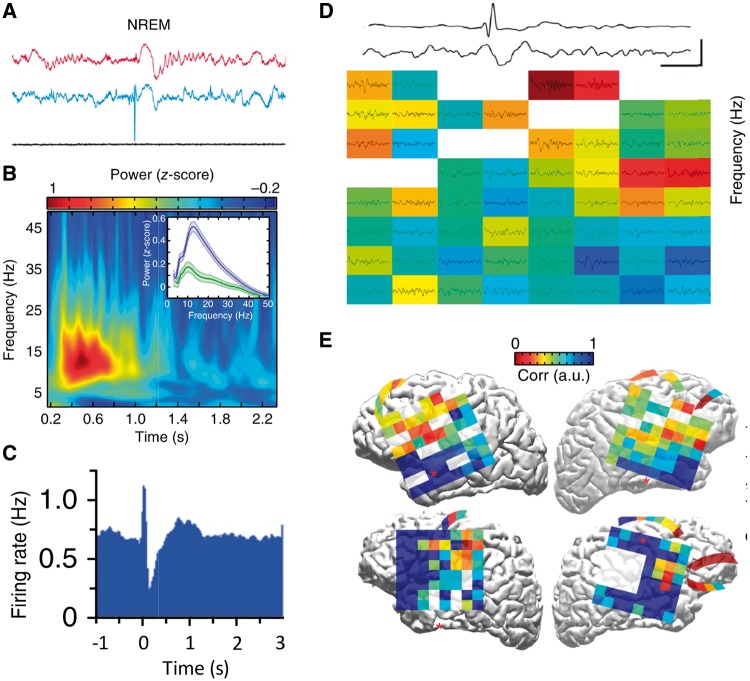

In patients, the best evidence for this comes from investigation of individuals who have had depth electrodes implanted into their hippocampi for presurgical evaluation. IEDs were associated with significant impairment in recall on a working memory task (Kleen et al., 2013; Ung et al., 2017). A recent study in a rat model of TLE revealed hippocampal-medial prefrontal coupling changes associated with IEDs (Fig. 4A–C) (Gelinas et al., 2016). Crucially, the frequency of IEDs and level of coupling correlated with memory impairment. Furthermore, a pilot study in patients with TLE demonstrated similar altered coupling between hippocampal IEDs and distant cortical electrical events, with IEDs leading to disruption of ongoing cortical activity (Fig. 4D and E) (Gelinas et al., 2016). An independent, detailed examination of a case with idiopathic generalized epilepsy using simultaneous video-EEG and functional MRI while the patient performed a working memory task also revealed widespread cortical effects of IEDs (Chaudhary et al., 2013), while a more recent group study on 67 cases reported that even IEDs originating outside the seizure zone can have a detrimental impact on memory (Ung et al., 2017). Such findings support the view that IEDs can have long-range effects leading to disrupted cognitive function.

Figure 4.

Hippocampal interictal epileptiform discharges couple with frontal activity. Rodent studies: (A) Medial prefrontal cortical (mPFC; red) and hippocampal (blue) local field potentials (LFPs) recorded during non-REM sleep in a kindling model of TLE. This is an example of a putative hippocampal IED-evoked spindle (oscillation) in frontal cortex. Similar findings occurred in REM sleep and awake states. (B) Normalized spectrogram in rat mPFC after hippocampal IED onset. The inset shows the change in averaged mPFC power spectrum from before (green) to after (blue) IED. (C) Average peri-event firing-rate histograms of mPFC pyramidal cells in the time window around hippocampal IED (which occurred at time zero) reveals a decrease in activity (‘down time’) in mPFC firing after the IED. Human studies: (D) LFP recorded from IED electrode in parahippocampal gyrus (upper) and subdural cortical electrode (lower) demonstrating time-locked spindle. The grid in frontal cortex shows z-scored spindle-band power across cortical electrocorticography (ECoG) array triggered on IED (white channels are non-functional). (E) ECoG grid and strip placement (each square represents one recording electrode) on the projected pial surface of four patients with epilepsy. Warm colours indicate high IED-spindle correlation; cool colours represent low correlation. Modified with permission from Gelinas et al. (2016).

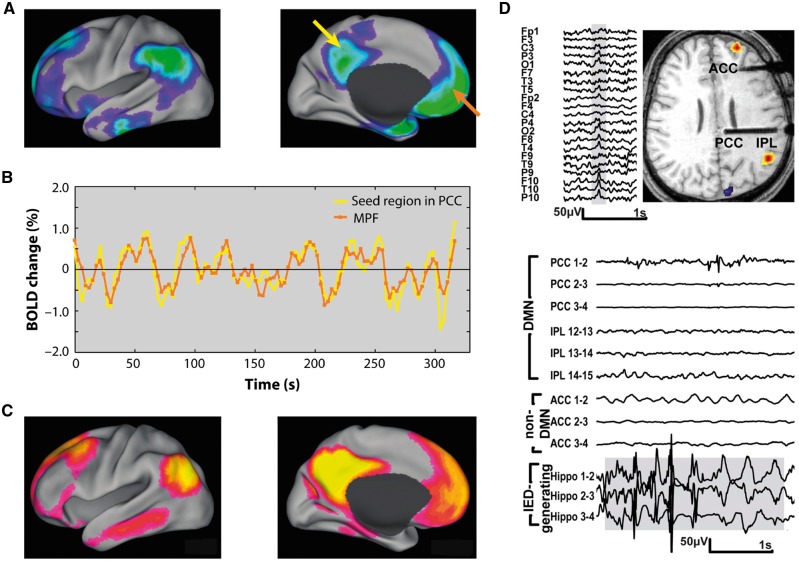

One specific question about the nature of long-range network effects of IEDs and seizure activity is whether these might have effects via certain critical nodes in the brain. In particular, a great deal of attention has turned to the role of the so-called default mode network (DMN; Fig. 5) (Raichle, 2015). This ensemble of brain regions includes the posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, lateral parietal and medial frontal regions, and is strongly linked to the hippocampus (Vincent et al., 2006). The DMN is most active at rest or when an individual is not performing a specific experimenter-defined task, but crucially deactivates during goal-directed behaviour (Fig. 5A), as assessed for example by changes in the BOLD signal detected by functional MRI. Greater deactivation of the DMN correlates positively with better performance on cognitive tasks, but is negatively correlated with activation in brain regions such as dorsolateral prefrontal regions, which are considered to essential to performing the cognitive task (Sambataro et al., 2010; Dang et al., 2013). In addition, stronger functional connectivity between DMN brain regions (Fig. 5B and C) is also related to better scores on tests of episodic memory and executive function (Sambataro et al., 2010; He et al., 2012; Dang et al., 2013).

Figure 5.

Default mode network and epilepsy. (A) DMN regions show decreases in activity when subjects perform cognitive tasks performance. (B) BOLD resting state activity is strongly correlated within DMN regions. Here activity is shown for the seed region in posterior cingulate cortex (yellow arrow in A) and another region which shows a similar pattern of activity, in medial prefrontal cortex (orange arrow in A). (C) Functional connectivity across DMN regions defined by spatial coherence in resting state BOLD signal fluctuations across these areas. (D) Top panel shows scalp EEG with right temporal IED and associated BOLD changes in a patient with TLE. Functional MRI demonstrates significant simultaneous activations in right frontal and parietal lobes and deactivation in cuneus. Bottom panel shows stereotaxic intracerebral EEG (SEEG) traces illustrating runs of hippocampal IEDs (lower three traces) and SEEG in posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), inferior parietal lobule (IPL) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). The most medial channel in PCC (upper trace) shows propagation of epileptic activity. (A–C) Adapted with permission from Raichle (2015); (D) Adapted from Fahoum et al. (2013).

In TLE, simultaneous functional MRI-EEG studies reveal that the medial temporal lobe BOLD signal is increased in association with IEDS (Laufs et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2010). Furthermore, both structural connectivity (measured by diffusion weighted MRI) and functional connectivity (indexed by functional MRI) are decreased within the DMN, compared to healthy individuals (Liao et al., 2011). Recent investigations of epilepsy patients using either functional MRI and/or EEG provide further support for abnormal DMN connectivity (Fig. 5D), either in the presence (Fahoum et al., 2013) or absence of IEDs (Coito et al., 2016; Robinson et al., 2017). Thus there is now abundant evidence for long-distance effects on the DMN in people with epilepsy including TLE, both during IEDs and in their absence.

Intriguingly, similar patterns of findings implicating the DMN have emerged independently in the Alzheimer’s disease literature. Hyperactivity within the hippocampus when people perform memory tasks in association with decreased resting functional connectivity of the DMN has been reported in mild cognitive impairment (Dickerson et al., 2005; Celone et al., 2006; Bakker et al., 2012), i.e. individuals who are at high risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Moreover, the level of DMN deactivation correlated with recall performance (Celone et al., 2006). The presence of concomitant cerebrovascular disease in Alzheimer’s disease may lead to systematic network changes that extend beyond the DMN, involving brain regions implicated in executive functions (Chong et al., 2017).

It is now also well established that amyloid deposition in Alzheimer’s disease (as measured using amyloid PET imaging) follows a pattern of distribution in the brain that is strikingly similar to the DMN. Remarkably, even in healthy older individuals, both hippocampal hyperactivity and reduced DMN deactivation during memory encoding tasks are associated with greater amyloid deposition (Sperling et al., 2009; Mormino et al., 2012). More recent investigation using tau PET imaging also reveals hyperactivity within the medial temporal lobe associated with greater tau deposition (Marks et al., 2017). Further, a longitudinal study using both functional MRI and amyloid PET imaging has reported that greater hippocampal activation on a memory task at baseline was associated with increased amyloid deposition over time (Leal et al., 2017).

It has been difficult to determine if hippocampal hyperactivity is pathological or simply an indicator of a compensatory response for declining memory in patients with mild cognitive impairment or those with greater amyloid/tau deposition. A proof-of-concept study demonstrated that 2 weeks of levetiracetam (at 125 mg twice a day or 62.5 mg twice a day but not at higher doses of 250 mg twice a day) suppressed aberrant hippocampal BOLD hyperactivity in amnestic mild cognitive impairment individuals, associated with a significant improvement in memory performance on an experimental task (Bakker et al., 2012). These findings therefore raise the possibility that hippocampal hyperactivity represents abnormal, pathological activity rather than a compensatory mechanism, as also suggested by findings in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease (Palop and Mucke, 2016). In the TLE literature, an independent study reported that levetiracetam normalized failure of hippocampal deactivation during a working memory task (Wandschneider et al., 2014), again pointing to important parallels between Alzheimer’s disease and TLE.

In more severe mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease cases hippocampal activity actually falls below normal, but DMN functional connectivity remains weakened (Celone et al., 2006). In addition, established Alzheimer’s disease not only has an increased associated risk of developing epilepsy (Imfeld et al., 2013), but recent work has revealed that patients with Alzheimer’s disease also show significantly greater subclinical epileptiform activity. One investigation has documented silent hippocampal seizure activity recorded from foramen ovale intracranial electrodes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (Lam et al., 2017). In a different study, ∼42% of Alzheimer’s disease cases monitored using overnight video-EEG had evidence of epileptiform activity (Vossel et al., 2016). This was defined as paroxysmal sharp waveforms of 20–200 ms, distinct from ongoing background activity and associated with a subsequent slow wave. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in brain atrophy between Alzheimer’s disease cases with and without subclinical epileptiform activity, suggesting that severity of Alzheimer’s disease might not be the crucial factor in distinguishing between these groups. Therefore, several lines of evidence point to intriguing and increasing similarities in network dysfunction associated with epilepsy—particularly TLE—and Alzheimer’s disease, raising the possibility that stabilization of abnormal neuronal networks might not only reduce seizures, but also improve cognition.

Conclusions and future directions

In this review we have sought to better understand whether seizures promote cognitive impairment and/or dementia, whether dementia causes seizures, or if common underlying pathophysiological mechanisms are responsible for both? The findings to date show that older adults with epilepsy, whether they developed the condition at a younger age or de novo later in life, exhibit poorer performance across a range of cognitive measures compared to healthy controls (Table 1) and have an increased risk of developing dementia. However, we note with caution that there has been surprisingly little investigation specifically of cognitive function in late-onset cases. The data that are available show that there is clear heterogeneity in cognitive performance across this group (Witt et al., 2014), just as there is in younger people with one subtype of epilepsy, TLE (Hermann et al., 2007). The key factors that determine this variation remain to be established and would be an important issue for future studies to focus on. Stratification of dementia risk in people with epilepsy at an early stage would potentially have a major impact in this field.

Although some pathologies (e.g. cerebrovascular disease) appear to have a worse prognosis for cognition, how different underlying pathologies interact with cognitive reserve, seizure control, psychological co-morbidities and lifestyle or vascular risk factors to impact upon everyday life, for both patients and carers, remains to be definitively established. Whether the pattern of cognitive impairment can help to stratify dementia risk or identify patients with more vascular versus Alzheimer-like pathology has also not been definitively assessed. However, the likelihood is that with mixed pathologies (e.g. traumatic, vascular, tau, amyloid) there might not be pure phenotypes. Indeed it is unclear whether dementia in the context of epilepsy represents a very different condition to dementia in other disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and mixed Alzheimer’s disease/vascular dementia, or whether specialized criteria for mild cognitive impairment or dementia diagnosis in people with epilepsy might need to be introduced in the future.

Whether epilepsy simply lowers brain reserve and thereby facilitates manifestation of dementia-related pathology, or whether epilepsy is a disorder that itself produces dementia—by the effects of seizures and IEDs on brain structure and function—also remains unclear. The evidence reviewed here certainly suggests that some vascular risk factors and pathophysiological mechanisms (e.g. tau and vascular pathology) are indeed common to people with epilepsy and dementia.

Another important future direction of research would be to investigate whether more aggressive management of vascular risk factors (e.g. blood pressure, smoking, diet and exercise) would improve control of seizures and thereby protect against worsening of cognitive decline in people with epilepsy. Likewise, an important related, unanswered question is whether elderly patients with epilepsy are genuinely susceptible to accelerated cognitive decline (Fig. 1). Does the pathological burden (vascular, traumatic, tau or amyloid) in people with epilepsy interact synergistically with ongoing seizure activity or IEDs to lead to progressive worsening of cognitive function and further deviation away from the normal trajectory associated with cognitive ageing? Longitudinal studies of older patients with epilepsy could potentially assist greatly in this regard.

Whether dementia causes seizures has also become a topic of great interest recently. Again, as reviewed here, there is increasing evidence from both human and animal model studies of an association between tau and/or amyloid pathology and development of seizures. In addition, some AEDs appear to have a beneficial impact not only in reducing such activity, but in actually improving cognitive function, perhaps by long-distance effects at the level of brain networks. Whether AED therapy would have a beneficial effect in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment who do not have overt seizures is the subject of ongoing trials.

All these questions are unlikely to be answered by small-scale studies. Given the range of underlying pathologies and the multitude of factors that impact upon cognitive performance discussed here, there is a pressing need for large-scale patient registries with harmonized systems of cognitive assessment. Standardization across centres as well as across disease diagnoses would greatly facilitate such an endeavour. Development of short, pragmatic test batteries that are not culturally specific would also improve detection of cognitive impairment in elderly people with epilepsy in the developing world. Baseline and longitudinal tracking of cognitive function using standardized neuropsychological measures is a particularly important consideration in this population in whom, as illustrated, very little research has been conducted to date.

In this review we have tried to identify what is currently understood about cognitive deficits in older people with epilepsy. We have highlighted the commonality of molecular and brain network disruption that may bind epilepsy and dementia much more closely than previously thought. We have also sought to identify possible areas of future research that may, in due course, offer the opportunities of slowing cognitive decline in patients with epilepsy.

Acknowledgements

We thank our anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments and suggestions.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, The Wellcome Trust and Wellcome Integrative Neuroscience Centre, Oxford.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AED

anti-epileptic drug

- DMN

default mode network

- IED

interictal epileptiform discharge

- TLE

temporal lobe epilepsy

References

- Ahmed RM, Paterson RW, Warren JD, Zetterberg H, O’Brien JT, Fox NC, et al. Biomarkers in dementia: clinical utility and new directions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014; 85: 1426–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatniek JC, Hauser WA, DelCastillo-Castaneda C, Jacobs DM, Marder K, Bell K, et al. Incidence and predictors of seizures in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Epilepsia 2006; 47: 867–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annegers J, Hauser W, Coan SP, Rocca W. A population-based study of seizures after traumatic brain injuries. N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 20–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annegers JF, Dubinsky S, Coan SP, Newmark ME, Roht L. The incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in multiethnic, urban health maintenance organizations. Epilepsia 1999; 40: 502–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A, Krauss GL, Albert MS, Speck CL, Jones LR, Stark CE, et al. Reduction of hippocampal hyperactivity improves cognition in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuron 2012; 74: 467–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell B, Lin JJ, Seidenberg M, Hermann BP. The neurobiology of cognitive disorders in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol 2011; 7: 154–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbeck GL. Epilepsy care in developing countries: part I of II. Epilepsy Curr 2010; 10: 75–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breteler MM, De Groot R, Van Romunde LK, Hofman A. Risk of dementia in patients with Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, and severe head trauma: a register-based follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 142: 1300–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer LE, Boon P, Bergmans JW, Mess WH, Besseling RM, de Louw A, et al. Cognitive deterioration in adult epilepsy: does accelerated cognitive ageing exist? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016; 64: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer LE, Grevers E, Boon P, Bernas A, Bergmans JW, Besseling RM, et al. Cognitive deterioration in adult epilepsy: clinical characteristics of ‘Accelerated Cognitive Ageing’. Acta Neurol Scand 2017; 136: 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MJ, Elder AT, Kwan P. Epilepsy in later life. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 1019–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns J, Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia 2003; 44 (Suppl 1): 2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busche MA, Eichhoff G, Adelsberger H, Abramowski D, Wiederhold KH, Haass C, et al. Clusters of hyperactive neurons near amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Science 2008; 321: 1686–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busche MA, Konnerth A. Impairments of neural circuit function in Alzheimer’s disease. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 2016; 371: 20150429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler CR, Graham KS, Hodges JR, Kapur N, Wardlaw JM, Zeman AZ. The syndrome of transient epileptic amnesia. Ann Neurol 2007; 61: 587–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler CR, Zeman AZ. Recent insights into the impairment of memory in epilepsy: transient epileptic amnesia, accelerated long-term forgetting and remote memory impairment. Brain 2008; 131: 2243–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caciagli L, Bernasconi A, Wiebe S, Koepp MJ, Bernasconi N, Bernhardt BC. A meta-analysis on progressive atrophy in intractable temporal lobe epilepsy: time is brain? Neurology 2017; 89: 506–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canter RG, Penney J, Tsai LH. The road to restoring neural circuits for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2016; 539: 187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celone KA, Calhoun VD, Dickerson BC, Atri A, Chua EF, Miller SL, et al. Alterations in memory networks in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: an independent component analysis. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 10222–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary UJ, Centeno M, Carmichael DW, Vollmar C, Rodionov R, Bonelli S, et al. Imaging the interaction: epileptic discharges, working memory, and behavior. Hum Brain Mapp 2013; 34: 2910–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CH, Liu CJ, Ou SM, Yeh CM, Chen TJ, Lin YY, et al. Incidence and risk of seizures in Alzheimer’s disease: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Epilepsy Res 2015; 115: 63–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JS, Craft R, Yu GQ, Ho K, Wang X, Mohan G, et al. Tau reduction diminishes spatial learning and memory deficits after mild repetitive traumatic brain injury in mice. PLoS One 2014; 9: e115765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Pack A, Elkind MS, Longstreth WT Jr, Ton TG, Onchiri F. Predictors of incident epilepsy in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Neurology 2017; 88: 870–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong JS, Liu S, Loke YM, Hilal S, Ikram MK, Xu X, et al. Influence of cerebrovascular disease on brain networks in prodromal and clinical Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2017; 140: 3012–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary P, Shorvon S, Tallis R. Late-onset seizures as a predictor of subsequent stroke. Lancet 2004; 363: 1184–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coito A, Genetti M, Pittau F, Iannotti GR, Thomschewski A, Höller Y, et al. Altered directed functional connectivity in temporal lobe epilepsy in the absence of interictal spikes: a high density EEG study. Epilepsia 2016; 57: 402–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad J, Pawlowski M, Dogan M, Kovac S, Ritter MA, Evers S. Seizures after cerebrovascular events: risk factors and clinical features. Seizure 2013; 22: 275–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook M, Baker N, Lanes S, Bullock R, Wentworth C, Arrighi HM. Incidence of stroke and seizure in Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Age Ageing 2015; 44: 695–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cretin B, Philippi N, Dibitonto L, Blanc F. Epilepsy at the prodromal stages of neurodegenerative diseases. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil 2017; 15: 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabbs K, Becker T, Jones J, Rutecki P, Seidenberg M, Hermann B. Brain structure and aging in chronic temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 2012; 53: 1033–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabbs K, Jones J, Seidenberg M, Hermann B. Neuroanatomical correlates of cognitive phenotypes in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2009; 15: 445–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang LC, O’Neil JP, Jagust WJ. Genetic effects on behavior are mediated by neurotransmitters and large-scale neural networks. Neuroimage 2013; 66: 203–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVos SL, Goncharoff DK, Chen G, Kebodeaux CS, Yamada K, Stewart FR, et al. Antisense reduction of Tau in adult mice protects against seizures. J Neurosci 2013; 33: 12887–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Salat DH, Greve DN, Chua EF, Rand-Giovannetti E, Rentz DM, et al. Increased hippocampal activation in mild cognitive impairment compared to normal aging and AD. Neurology 2005; 65: 404–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dik MG, Jonker C, Hack CE, Smit JH, Comijs HC, Eikelenboom P. Serum inflammatory proteins and cognitive decline in older persons. Neurology 2005; 64: 1371–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkelacker V, Dupont S, Samson S. The new approach to classification of focal epilepsies: epileptic discharge and disconnectivity in relation to cognition. Epilepsy Behav 2016; 64: 322–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodrill CB. Neuropsychological effects of seizures. Epilepsy Behav 2004; 5 (Suppl 1): S21–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott G, Isaac CL, Muhlert N. Measuring forgetting: a critical review of accelerated long-term forgetting studies. Cortex 2014; 54: 16–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englot DJ, Konrad PE, Morgan VL. Regional and global connectivity disturbances in focal epilepsy, related neurocognitive sequelae, and potential mechanistic underpinnings. Epilepsia 2016; 57: 1546–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahoum F, Zelmann R, Tyvaert L, Dubeau F, Gotman J. Epileptic discharges affect the default mode network–FMRI and intracerebral EEG evidence. PLoS One 2013; 8: e68038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratiglioni L, Paillard-Borg S, Winblad B. An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol 2004; 3: 343–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelinas JN, Khodagholy D, Thesen T, Devinsky O, Buzsáki G. Interictal epileptiform discharges induce hippocampal-cortical coupling in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Med 2016; 22: 641–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheyara AL, Ponnusamy R, Djukic B, Craft RJ, Ho K, Guo W, et al. Tau reduction prevents disease in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Ann Neurol 2014; 76: 443–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson LM, Hanby MF, Al-Bachari SM, Parkes LM, Allan SM, Emsley HC. Late-onset epilepsy and occult cerebrovascular disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 564–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowers W. Epilepsy and other chronic convulsive diseases: their causes, symptoms, & treatment. London: Churchill; 1881. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith HR, Martin RC, Bambara JK, Faught E, Vogtle LK, Marson DC. Cognitive functioning over 3 years in community dwelling older adults with chronic partial epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2007; 74: 91–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith HR, Martin RC, Bambara JK, Marson DC, Faught E. Older adults with epilepsy demonstrate cognitive impairments compared with patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Epilepsy Behav 2006; 8: 161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri T, Cox DR. The delayed neurobehavioural sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 1991; 5: 219–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamed SA. Atherosclerosis in epilepsy: its causes and implications. Epilepsy Behav 2014; 41: 290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanby MF, Al-Bachari S, Makin F, Vidyasagar R, Parkes LM, Emsley HCA. Structural and physiological MRI correlates of occult cerebrovascular disease in late-onset epilepsy. Neuroimage Clin 2015; 9: 128–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper L, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, Schott JM, Fox NC. An algorithmic approach to structural imaging in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014; 85: 692–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Carmichael O, Fletcher E, Singh B, Iosif AM, Martinez O, et al. Influence of functional connectivity and structural MRI measures on episodic memory. Neurobiol Aging 2012; 33: 2612–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmers SL, Thurman DJ, Durgin TL, Pai AK, Faught E. Descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy in the U.S. population: a different approach. Epilepsia 2015; 56: 942–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstaedter C, Elger CE. Chronic temporal lobe epilepsy: a neurodevelopmental or progressively dementing disease. Brain 2009; 132: 2822–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstaedter C, Witt JA. Epilepsy and cognition—a bidirectional relationship? Seizure 2017; 49: 83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann B, Seidenberg M, Lee EJ, Chan F, Rutecki P. Cognitive phenotypes in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2007; 13: 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann B, Seidenberg M, Sager M, Carlsson C, Gidal B, Sheth R, et al. Growing old with epilepsy: the neglected issue of cognitive and brain health in aging and elder persons with chronic epilepsy. Epilepsia 2008; 49: 731–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann BP, Seidenberg M, Dow C, Jones J, Rutecki P, Bhattacharya A, et al. Cognitive prognosis in chronic temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol 2006; 60: 80–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höller Y, Trinka E. What do temporal lobe epilepsy and progressive mild cognitive impairment have in common? Front Syst Neurosci 2014; 8: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes GL. Cognitive impairment in epilepsy: the role of network abnormalities. Epileptic Disord 2015; 17: 101–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommet C, Mondon K, Camus V, De Toffol B, Constans T. Epilepsy and dementia in the elderly. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008; 25: 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain SA, Haut SR, Lipton RB, Derby C, Markowitz SY, Shinnar S. Incidence of epilepsy in a racially diverse, community-dwelling, elderly cohort: results from the Einstein aging study. Epilepsy Res 2006; 71: 195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imfeld P, Bodmer M, Schuerch M, Jick SS, Meier CR. Seizures in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia: a population-based nested case-control analysis. Epilepsia 2013; 54: 700–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry MC, Jin S, He F, Emond JA, Raman R, Thomas RG, et al. Incidence of new-onset seizures in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2012; 69: 368–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Holtzman DM. Biomarker modeling of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2013; 80: 1347–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Epilepsy Council. Epilepsy prevalence, incidence and other statistics. UK and Ireland: Joint Epilepsy Council; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jones NC, Nguyen T, Corcoran NM, Velakoulis D, Chen T, Grundy R, et al. Targeting hyperphosphorylated tau with sodium selenate suppresses seizures in rodent models. Neurobiol Dis 2012; 45: 897–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutsa J, Rinne JO, Hermann B, Karrasch M, Anttinen A, Shinnar S, et al. Association between childhood-onset epilepsy and amyloid burden 5 decades later. JAMA Neurol 2017; 74: 583–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keezer MR, Sisodiya SM, Sander JW. Comorbidities of epilepsy: current concepts and future perspectives. Lancet Neurol 2016; 15: 106–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SS, Roberts N. Voxel-based morphometry of temporal lobe epilepsy: an introduction and review of the literature. Epilepsia 2008; 49: 741–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleen JK, Scott RC, Holmes GL, Lenck-Santini PP. Cognitive and behavioral comorbidities of epilepsy. Epilepsia 2010; 51: 79.19624717 [Google Scholar]

- Kleen JK, Scott RC, Holmes GL, Roberts DW, Rundle MM, Testorf M, et al. Hippocampal interictal epileptiform activity disrupts cognition in humans. Neurology 2013; 81: 18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam AD, Deck G, Goldman A, Eskandar EN, Noebels J, Cole AJ. Silent hippocampal seizures and spikes identified by foramen ovale electrodes in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 2017; 23: 678–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufs H, Hamandi K, Salek-Haddadi A, Kleinschmidt AK, Duncan JS, Lemieux L. Temporal lobe interictal epileptic discharges affect cerebral activity in ‘default mode’ brain regions. Hum Brain Mapp 2007; 28: 1023–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal SL, Landau SM, Bell RK, Jagust WJ. Hippocampal activation is associated with longitudinal amyloid accumulation and cognitive decline. Elife 2017; 6: e22978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W, Zhang Z, Pan Z, Mantini D, Ding J, Duan X, et al. Default mode network abnormalities in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: a study combining fMRI and DTI. Hum Brain Mapp 2011; 32: 883–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JJ, Mula M, Hermann BP. Uncovering the neurobehavioural comorbidities of epilepsy over the lifespan. Lancet 2012; 380: 1180–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CC, Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol 2013; 9: 106–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]