Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association between alcohol consumption (at baseline and over lifetime) and non-fatal and fatal coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke.

Design

Multicentre case-cohort study.

Setting

A study of cardiovascular disease (CVD) determinants within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and nutrition cohort (EPIC-CVD) from eight European countries.

Participants

32 549 participants without baseline CVD, comprised of incident CVD cases and a subcohort for comparison.

Main outcome measures

Non-fatal and fatal CHD and stroke (including ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke).

Results

There were 9307 non-fatal CHD events, 1699 fatal CHD, 5855 non-fatal stroke, and 733 fatal stroke. Baseline alcohol intake was inversely associated with non-fatal CHD, with a hazard ratio of 0.94 (95% confidence interval 0.92 to 0.96) per 12 g/day higher intake. There was a J shaped association between baseline alcohol intake and risk of fatal CHD. The hazard ratios were 0.83 (0.70 to 0.98), 0.65 (0.53 to 0.81), and 0.82 (0.65 to 1.03) for categories 5.0-14.9 g/day, 15.0-29.9 g/day, and 30.0-59.9 g/day of total alcohol intake, respectively, compared with 0.1-4.9 g/day. In contrast, hazard ratios for non-fatal and fatal stroke risk were 1.04 (1.02 to 1.07), and 1.05 (0.98 to 1.13) per 12 g/day increase in baseline alcohol intake, respectively, including broadly similar findings for ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke. Associations with cardiovascular outcomes were broadly similar with average lifetime alcohol consumption as for baseline alcohol intake, and across the eight countries studied. There was no strong evidence for interactions of alcohol consumption with smoking status on the risk of CVD events.

Conclusions

Alcohol intake was inversely associated with non-fatal CHD risk but positively associated with the risk of different stroke subtypes. This highlights the opposing associations of alcohol intake with different CVD types and strengthens the evidence for policies to reduce alcohol consumption.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of mortality worldwide, and it is estimated that the overall number of cardiovascular disease deaths will rise to 20 million by 2030.1 Coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke are the most common forms of CVD, as estimated by the Global Burden of Disease study.2 CHD and stroke account for 20% and 12% respectively of overall mortality in Europe.3 The association between alcohol consumption and the risk of CVD has been investigated. A positive association with stroke has been established, but the shapes of dose-response relations for different CVD outcomes have not been well characterised.4

Epidemiological studies have provided observational evidence of lower risk of CHD with moderate alcohol consumption compared with non-drinkers and heavy drinkers. The existence of a J shaped relation between alcohol intake and the risk of CHD was reported in a meta-regression study.5 Lower risk of CHD in regular drinkers and higher risk of CHD in binge and heavy drinkers, compared with non-drinkers, was described in a subsequent meta-analysis.6 Those results were recently confirmed in a meta-analysis of 11 cohort studies, which reported that baseline alcohol intake in the range of 15-30 g/day was inversely related with the risk of CHD, compared with non-drinkers.7 It has also been suggested that non-fatal and fatal CHD might have different determinants.8 Investigations focusing on fatal CHD events tended to report positive associations with alcohol intake compared with studies that evaluated the association between alcohol intake and both non-fatal and fatal CHD events.9 A meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies reported that alcohol intake was consistently associated with a higher risk of morbidity and mortality of ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, in both men and women.10 In a recent study in the UK, heavy alcohol intake was positively associated with coronary death, heart failure, cardiac arrest, transient ischaemic attack, ischaemic stroke, intracerebral haemorrhage, and peripheral arterial disease, compared with moderate use, but inversely related to myocardial infarction or stable angina.4 Such opposing relations of alcohol consumption with different CVD types have also been reported in a recent study combined analysis of data from 83 cohorts in high-income countries.11

Most prospective studies of CVD have solely assessed recent alcohol intake at participants’ time of entry into a cohort, but not queried participants’ drinking habits over many earlier decades (ie, lifetime alcohol consumption). Similarly, the association between consumption of different types of alcohol (eg, wine and beer) and CVD risk has not been thoroughly explored.11 Hence, we evaluated the dose-response association of baseline and lifetime alcohol consumption, including different types of alcohol, with the risk of incident CHD and stroke in the EPIC-CVD study.

Methods

Study population and design

The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and nutrition (EPIC) study enrolled 519 978 adults (366 521 women) aged mostly 35-70 from 23 centres in 10 countries between 1991 and 2000, as described elsewhere.12 EPIC-CVD is a multi centre case-cohort study nested within the EPIC cohort designed to investigate the determinants of cardiovascular disease (CVD).13 The study included 18 816 incident CVD cases identified between March 1991 and December 2010 in the EPIC cohort and a random subcohort of 17 634 EPIC participants was used as a reference group.14 Participants in the case-cohort study belonged to one of the following categories: cases that arose outside the subcohort, cases that arose in the subcohort, and non-cases in the subcohort.

Outcome assessment

The main coronary disease endpoints were defined as any coronary heart disease (CHD), comprised of myocardial infarction (ICD-10 (international classification of diseases, 10th revision) codes: I21, I22), angina (I20), or other CHD (I23-I25). Cerebrovascular events were ascertained and validated using the same methods as for coronary events and included haemorrhagic stroke (I60-I61), ischaemic stroke (I63), unclassified stroke (I64), and other acute cerebrovascular events (I62, I65-69, F01). Non-fatal coronary events were ascertained by different methods depending on the follow-up procedures used by each centre, using active follow-up through questionnaires or linkage with morbidity and hospital registries, or both.13

Validation of suspected events was performed on all ascertained case events (Italy, Spain, Greece, Germany, and Denmark) or on a subset of events (UK, the Netherlands, and Sweden). Validation was performed by retrieving and assessing medical records or hospital notes, contact with medical professionals, retrieving and assessing death certificates, or verbal autopsy. Angina was not assessed as a CHD outcome in the Italian EPIC centres of Varese, Torino, and in Germany, Sweden, and Denmark. To harmonise the definition of fatal CVD across centres, non-fatal and fatal events occurring within 28 days of each other were considered to be a single fatal event, in accordance with commonly used definitions.15 Information on CVD and overall mortality were ascertained using boards of health and mortality registries (Italy, Spain, UK, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark) or by active follow-up (Greece and Germany). In the EPIC study, loss to follow-up is less than 0.3%.

Participant characteristics

We calculated alcohol consumption at baseline for the whole EPIC cohort from validated dietary questionnaires specific to each country which captured local dietary habits.12 16 Participants reported the number of standard glasses of wine, beer, cider, sweet liquor, distilled spirits, or fortified wines they consumed daily or weekly during the 12 months before recruitment. Alcohol consumption was taken from highly standardised 24 hour dietary recall measurements from a subset of the cohort.17

We calculated total alcohol intake using the estimated ethanol content in the types of alcohol and information on average glass volumes for each country. Lifetime alcohol consumption, available for 76% of participants (395 183/519 978), was assessed as glasses of different beverages consumed weekly at age 20, 30, 40, and 50. Average lifetime alcohol consumption was determined as a weighted average of intake over lifetime, with weights equal to the time of individual exposure to alcohol at different ages.18 Smoking status at baseline, age at starting and quitting smoking, and number of cigarettes smoked daily was collected by lifestyle questionnaires for each country. The following information was also collected: socioeconomic status, height and weight (self reported in the UK Oxford centre, measured elsewhere), physical activity, and history of previous illnesses (including myocardial infarction, angina, stroke, diabetes, cancer, and hypertension). Participants from Norway and France were excluded as there were too few cardiovascular events in these countries to obtain reliable estimates.

Statistical analyses

After exclusion of participants with missing values for smoking variables (n=505), baseline alcohol consumption (51), body mass index (273), physical activity (333), and history of hypertension (1112), 32 549 participants (52% women, 17 015/32 549), remained in the analysis. Predefined categories of baseline and lifetime alcohol intakes were defined as lower than 0.1 g/day (defined as non-drinkers at baseline and never drinkers at lifetime), 0.1–4.9 g/day (reference category), 5.0-14.9 g/day, 15.0-29.9 g/day, 30.0-59.9 g/day, and ≥60.0 g/day. Associations for wine and beer intake (each grouped into non-drinkers, 0.1–2.9 g/day (reference), 3.0-9.9 g/day, 10.0-19.9 g/day, 20.0-39.9 g/day, and ≥40.0 g/day, ≥20.0 g/day in women) were assessed in mutually adjusted models, also accounting for spirits, liquors, and fortified wine intake.

The first non-fatal and fatal CHD and stroke events were modelled in Prentice weighted Cox proportional hazard models with age as the underlying time variable,19 stratified by sex and centre. Participants within the subcohort contributed follow-up time until the point at which they had a non-fatal or fatal CVD event, died of a non-CVD cause, were lost to follow-up, or reached the end of the centre’s follow-up period. Robust standard errors were used since participants’ contributions to the case-cohort pseudo-likelihood are not independent.20 Models were adjusted for age at recruitment; body mass index; height; smoking status categorised as never (reference category), former, and current; history of hypertension (yes or no); and physical activity as defined by the Cambridge Index (inactive, moderately inactive, moderately active, and active). Adjustment for more extensive information on smoking frequency and duration, plasma levels of total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides at baseline, and education level did not alter the risk estimates; these results were not retained further.

Hazard ratios for overall CVD and non-fatal and fatal CHD and stroke were computed in relation to baseline and lifetime alcohol consumption in predefined categories, per 12 g/day increase, and for mutually adjusted types of alcohol. In analyses of lifetime alcohol consumption, information on alcohol intake at different ages was used to separate non-drinkers at baseline into never drinkers and former drinkers. We conducted sensitivity analyses, in turn, for non-fatal CHD and stroke after exclusion of the first two years of follow-up (to help limit potential reverse causality), for non-fatal and overall myocardial infarction, separately in centres that collected information on incident angina, and by adjusting models for known history of cancer and diabetes. We conducted further analyses separately for ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke.

The overall test of significance for the association of alcohol consumption with CVD outcomes was assessed with Wald test statistics compared with a χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of categories minus one, not including the non-drinker category. We performed trend tests by modelling alcohol consumption as a continuous variable on the log hazard scale, with inclusion of an indicator variable to define non-drinkers. A quadratic term for alcohol intake was also included in the model for fatal CHD to assess non-linearity. We further investigated the shape of the association between alcohol consumption and risk of non-fatal CHD using restricted cubic splines with knots defined by the mid-points of categories described earlier.

We evaluated potential heterogeneity of associations between alcohol consumption and the risk of non-fatal CHD and stroke according to smoking status by including an interaction term between baseline alcohol consumption (continuous) and smoking status (0=never, 1=current smokers). We assessed the interaction term with the Wald test on one degree of freedom. We also evaluated the heterogeneity of associations by physical activity and education level, but the results were compatible with the hypothesis of homogeneity across levels of these variables. The assumption of proportionality of hazards was evaluated using the inclusion into the disease model of interaction terms between exposure and attained age (data not shown).

The certainty of each incident cardiovascular event was assessed using available clinical information, and a score was developed to express low, medium, or high certainty, as summarised in supplementary table 5. We excluded events with the lowest certainty level when performing the sensitivity analyses and effect estimates were minimally affected, even for fatal stroke.

Hazard ratios for the associations of non-fatal and fatal CHD and stroke with baseline alcohol consumption (per 12 g/day increase) were further estimated for each country and combined with random effects meta-analyses. Linear and quadratic terms were modelled for fatal CHD. Heterogeneity by country was assessed with the Cochran Q test, and estimated by the I2 index. We obtained the associated P value by comparing the Cochran Q statistics to a χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of countries minus one. Statistical tests were two sided, and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).21

Patient involvement

No participants were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No participants were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows the sex and country specific numbers of cardiovascular events, as well as descriptive statistics about baseline and lifetime alcohol consumption, including types of alcohol, among the subcohort. A total of 11 006 first coronary heart disease (CHD) events were identified; 9307 were non-fatal and 1699 were fatal. A total of 6588 first stroke events were identified; 5855 were non-fatal and 733 were fatal. The median age at recruitment and follow-up time in in the subcohort were 52 and 12.5 years, respectively.

Table 1.

Sex and country specific numbers of cardiovascular events (n=17 594) and descriptive statistics about baseline and lifetime alcohol status and consumption (g/day) among the subcohort (n=16 244)

| Country | Total events | CHD | Stroke | Baseline alcohol | Lifetime alcohol | Types of alcohol | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-fatal | Fatal | Non-fatal | Fatal | Non-drinkers (%) | Drinkers* | Never drinkers (%) | Drinkers* | Wine | Beer | Spirits† | ||||||

| Men | ||||||||||||||||

| Italy | 622 | 472 | 25 | 115 | 10 | 5 | 26 (1-65) | 3 | 24 (2-60) | 22 (0-59) | 1 (0-5) | 2 (0-11) | ||||

| Spain | 1265 | 797 | 93 | 343 | 32 | 13 | 33 (2-88) | 3 | 46 (3-111) | 26 (0-73) | 3 (0-16) | 4 (0-17) | ||||

| UK | 1568 | 1042 | 292 | 161 | 73 | 11 | 11 (1-39) | 1 | 14 (1-38) | 5 (0-29) | 4 (0-22) | 2 (0-8) | ||||

| The Netherlands | 498 | 385 | 31 | 75 | 7 | 10 | 18 (1-55) | NA | NA | 3 (0-14) | 9 (0-35) | 3 (0-22) | ||||

| Greece | 399 | 177 | 62 | 104 | 56 | 9 | 20 (1-67) | 5 | 32 (0-96) | 10 (0-43) | 4 (0-19) | 6 (0-28) | ||||

| Germany | 761 | 383 | 93 | 263 | 22 | 4 | 26 (2-68) | 1 | 29 (3-76) | 8 (0-44) | 15 (0-60) | 2 (0-7) | ||||

| Sweden | 2763 | 1220 | 407 | 1,057 | 79 | 11 | 11 (1-36) | NA | NA | 3 (0-12) | 4 (0-12) | 4 (0-16) | ||||

| Denmark | 2158 | 1055 | 154 | 922 | 27 | 2 | 29 (2-78) | 1 | 21 (3-51) | 11 (0-30) | 14 (0-55) | 4 (0-11) | ||||

| All | 10 034 | 5531 | 1157 | 3040 | 306 | 8 | 24 (1-70) | 2 | 30 (2-87) | 13 (0-51) | 7 (0-32) | 3 (0-15) | ||||

| Women | ||||||||||||||||

| Italy | 596 | 403 | 10 | 160 | 23 | 23 | 11 (0-36) | 16 | 8 (1-23) | 9 (0-35) | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0-11) | ||||

| Spain | 630 | 311 | 23 | 260 | 36 | 50 | 9 (0-30) | 37 | 7 (0-22) | 7 (0-30) | 1 (0-8) | 0 (0-17) | ||||

| UK | 1233 | 780 | 142 | 203 | 108 | 16 | 7 (0-29) | 6 | 7 (0-22) | 5 (0-12) | 1 (0-4) | 2 (0-8) | ||||

| The Netherlands | 1444 | 986 | 67 | 321 | 70 | 20 | 11 (0-37) | 11 | 9 (1-24) | 6 (0-24) | 1 (0-3) | 4 (0-22) | ||||

| Greece | 271 | 87 | 30 | 91 | 63 | 36 | 6 (1-18) | 34 | 5 (0-17) | 3 (0-12) | 1 (0-6) | 1 (0-28) | ||||

| Germany | 318 | 112 | 23 | 172 | 11 | 5 | 10 (0-36) | 3 | 7 (1-23) | 7 (0-26) | 2 (0-14) | 1 (0-7) | ||||

| Sweden | 1866 | 641 | 187 | 950 | 88 | 18 | 7 (0-21) | NA | NA | 3 (0-12) | 1 (0-5) | 2 (0-16) | ||||

| Denmark | 1202 | 456 | 60 | 658 | 28 | 2 | 14 (1-41) | 6 | 9 (1-24) | 6 (0-30) | 3 (0-12) | 2 (0-11) | ||||

| All | 7560 | 3776 | 542 | 2815 | 427 | 24 | 10 (0-33) | 15 | 8 (0-23) | 6 (0-27) | 2 (0-7) | 2 (0-7) | ||||

NA=Information on lifetime consumption not available in Bilthoven (The Netherlands), Naples (Italy), and Sweden.

Mean and 5th-95th centile values calculated among drinkers only.

Spirits, liquors, and fortified wine.

Baseline and lifetime alcohol consumption averages among alcohol drinkers in the subcohort were, respectively, 24 g/day and 30 g/day in men, and 10 g/day and 8 g/day in women. Baseline alcohol consumption in men was higher in Italy, Spain, Germany, and Denmark than in other EPIC countries. Women from Denmark had the highest baseline and lifetime alcohol intake. Wine represented more than 50% of total alcohol intake; beer represented around 30% and 20% of total intake, in men and women, respectively. This pattern of consumption was relatively homogeneous across countries for women. In Italy and Spain men mainly consumed wine, but in Germany they mainly consumed beer. The subcohort is described by categories of alcohol intake and smoking status in supplementary table 1. Average baseline alcohol consumption was consistently higher, for men and women, in former and current smokers than in never smokers.

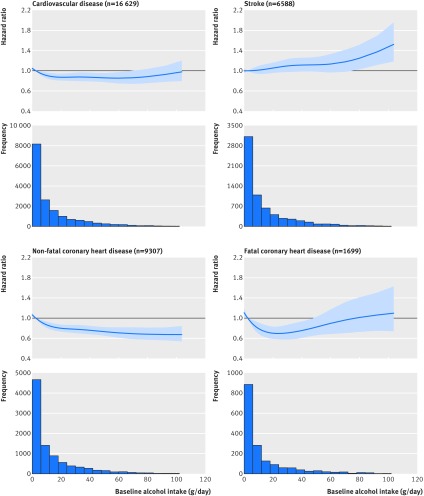

Alcohol consumption, coronary heart disease, and stroke

Alcohol consumption was inversely associated with non-fatal CHD (hazard ratio of 0.94 per 12 g/day increase, 95% confidence interval 0.91 to 0.96, P<0.001 for trend). Table 2 shows that compared with the reference group (0.1-4.9 g/day), alcohol drinkers of 30.0-59.9 g/day and at least 60.0 g/day had hazard ratios of to 0.73 (95% confidence interval 0.65 to 0.83) and 0.68 (0.57 to 0.81), respectively, for non-fatal CHD. Alcohol was non-linearly associated with fatal CHD, with hazard ratios for the 15.0-29.9 g/day group as low as 0.65 (0.53 to 0.81), and up to 0.98 (0.70 to 1.37) for intakes greater than 60.0 g/day. The non-linear association between alcohol intake and fatal CHD was described by a quadratic model with hazard ratio per 12 g/day increase indicating first and second degree terms equal to, respectively, 0.92 (0.85 to 0.99) and 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02). Figure 1 shows the non-linear trends from a restricted cubic splines analysis. Baseline alcohol consumption was positively associated with non-fatal stroke (hazard ratio of 1.04 per 12 g/day increase, 95% confidence interval 1.02 to 1.07), while the association with fatal stroke was of similar magnitude but not statistically significant (1.05, 0.98 to 1.13). Positive associations with overlapping confidence intervals were observed for ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, with hazard ratio of 1.05 per 12 g/day increase (95% confidence interval 1.02 to 1.09, P=0.001 for trend) and 1.10 (1.04 to 1.15, P<0.001 for trend), respectively (see supplementary table 3).

Table 2.

Number of events and hazard ratios for coronary heart disease and stroke by levels of baseline alcohol consumption (g/day)

| Characteristic | Non-fatal | Fatal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Events | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

| Coronary heart disease | |||||

| Non-drinkers | 1592 | 1.15 (1.03 to 1.28) | 332 | 1.25 (1.01 to 1.53) | |

| 0.1-4.9 | 2797 | 1 (ref) | 497 | 1 (ref) | |

| 5.0-14.9 | 2207 | 0.82 (0.75 to 0.90) | 418 | 0.83 (0.70 to 0.98) | |

| 15.0-29.9 | 1324 | 0.78 (0.70 to 0.87) | 198 | 0.65 (0.53 to 0.81) | |

| 30.0-59.9 | 1027 | 0.73 (0.65 to 0.83) | 174 | 0.82 (0.65 to 1.03) | |

| ≥60.0 | 360 | 0.68 (0.57 to 0.81) | 80 | 0.98 (0.70 to 1.37) | |

| P value* | <0.001 | 0.002 | |||

| 12 g/day increase | Linear | 0.94 (0.92 to 0.96) | Linear | 0.92 (0.85 to 0.99) | |

| Quadratic | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) | ||||

| P value for trend† | <0.001 | P value‡ | 0.003 | ||

| Stroke | |||||

| Non-drinkers | 924 | 1.26 (1.12 to 1.43) | 187 | 1.41 (1.12 to 1.79) | |

| 0.1-4.9 | 1573 | 1 (ref) | 214 | 1 (ref) | |

| 5.0-14.9 | 1508 | 1.03 (0.93 to 1.14) | 167 | 1.04 (0.83 to 1.31) | |

| 15.0-29.9 | 872 | 1.08 (0.96 to 1.22) | 88 | 1.07 (0.81 to 1.42) | |

| 30.0-59.9 | 704 | 1.10 (0.96 to 1.26) | 61 | 1.20 (0.87 to 1.67) | |

| ≥60.0 | 274 | 1.31 (1.07 to 1.60) | 16 | 1.14 (0.65 to 2.01) | |

| P value* | 0.109 | 0.863 | |||

| 12 g/day increase | Linear | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.07) | Linear | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.13) | |

| P value for trend† | 0.002 | 0.136 | |||

Models were stratified by centre and sex, and systematic adjustment was undertaken for age at recruitment, body mass index, height, physical activity, smoking status, and history of hypertension.

P value for the Wald test statistics compared with a χ2 distribution with four degrees of freedom, not including the category of non-drinkers (<0.1 g/day).

P value for baseline alcohol consumption modelled as a continuous variable, with inclusion in the model of an indicator variable expressing alcohol consumption at baseline.

P value for inclusion of a quadratic term for baseline alcohol consumption.

Fig 1.

Association between baseline alcohol consumption (g/day) and risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, non-fatal coronary heart disease, and fatal coronary heart disease

Table 3 shows that lifetime alcohol consumption was inversely associated with non-fatal CHD, with hazard ratios of 0.74 (95% confidence interval 0.64 to 0.86) and 0.75 (0.62 to 0.91) for alcohol consumption of 30.0-59.9 g/day and at least 60.0 g/day, respectively, compared with the reference category. Lifetime alcohol consumption was positively associated with non-fatal stroke with a hazard ratio of 1.03 (95% confidence interval 1.00 to 1.06, P=0.03 for trend). Never and former drinkers had similar non-fatal CHD and stroke risks, showing on average a 20% higher risk compared with light drinkers (0.1-4.9 g/day).

Table 3.

Number of events and hazard ratios for non-fatal coronary heart disease (CHD) and non-fatal stroke by levels of lifetime alcohol consumption (g/day), accounting for former drinkers

| Characteristic | Non-fatal CHD | Non-fatal stroke | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Events | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

| Former drinkers* | 615 | 1.24 (1.05 to 1.46) | 253 | 1.27 (1.04 to 1.54) | |

| Never drinkers | 580 | 1.17 (1.00 to 1.38) | 305 | 1.14 (0.95 to 1.37) | |

| 0.1-4.9 | 1571 | 1 (ref) | 791 | 1 (ref) | |

| 5.0-14.9 | 1800 | 0.89 (0.80 to 1.00) | 1024 | 0.98 (0.86 to 1.11) | |

| 15.0-29.9 | 1102 | 0.79 (0.69 to 0.90) | 685 | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.17) | |

| 30.0-59.9 | 698 | 0.74 (0.64 to 0.86) | 428 | 1.08 (0.90 to 1.30) | |

| ≥60.0 | 331 | 0.75 (0.62 to 0.91) | 179 | 1.12 (0.88 to 1.44) | |

| P value† | <0.001 | 0.736 | |||

| 12 g/day increase | 0.97 (0.94 to 0.99) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.06) | |||

| P value for trend‡ | 0.008 | 0.034 | |||

Models were stratified by centre and sex, and systematic adjustment was undertaken for age at recruitment, body mass index, height, physical activity, smoking status, and history of hypertension. Analyses were conducted among participants with available information on lifetime alcohol intake.

Defined as lifetime drinkers who were non-drinkers at baseline.

P value for the Wald test statistics compared with a χ2 distribution with four degrees of freedom, not including the categories of former and never drinkers.

P value for lifetime alcohol consumption modelled as continuous variable, with inclusion in the model of an indicator variable expressing alcohol consumption, and exclusion of former drinkers.

Alcohol types

Table 4 shows that wine and beer intake were inversely associated with non-fatal CHD, with a hazard ratio of 0.94 per 12 g/day increase (95% confidence interval 0.91 to 0.97, P<0.001 for trend) and 0.94 (0.89 to 0.99, P=0.013 for trend), respectively. Beer intake was positively associated with non-fatal stroke with a 7% higher risk associated per 12 g/day (3% to 12%, P=0.002 for trend), but wine intake was not statistically significant. Spirits, liquors, and fortified wine intakes were not associated with CHD or stroke (data not shown).

Table 4.

Number of events and hazard ratios for non-fatal coronary heart disease (CHD) and non-fatal stroke by levels of types of alcohol consumption at baseline (g/day)

| Characteristic | Wine intake | Beer intake | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Events | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

| Non-fatal CHD | |||||

| Non-drinkers | 2932 | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.25) | 4021 | 1.08 (0.98 to 1.18) | |

| 0.1-2.9 | 2823 | 1 (ref) | 2733 | 1 (ref) | |

| 3.0-9.9 | 1869 | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.93) | 1611 | 1.07 (0.97 to 1.19) | |

| 10.0-19.9 | 649 | 0.86 (0.75 to 0.98) | 473 | 0.98 (0.84 to 1.15) | |

| 20.0-39.9 | 686 | 0.76 (0.66 to 0.86) | 317 | 0.86 (0.71 to 1.04) | |

| ≥40.0 | 348 | 0.73 (0.61 to 0.87) | 152 | 0.79 (0.59 to 1.05) | |

| P value* | <0.001 | 0.069 | |||

| 12 g/day increase | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.97) | 0.94 (0.89 to 0.99) | |||

| P value for trend† | <0.001 | 0.013 | |||

| Non-fatal stroke | |||||

| Non-drinkers | 1764 | 1.13 (1.01 to 1.25) | 2094 | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.26) | |

| 0.1-2.9 | 1671 | 1 (ref) | 1829 | 1 (ref) | |

| 3.0-9.9 | 1398 | 0.95 (0.85 to 1.05) | 1167 | 1.21 (1.08 to 1.35) | |

| 10.0-19.9 | 391 | 1.00 (0.85 to 1.16) | 369 | 1.16 (0.98 to 1.37) | |

| 20.0-39.9 | 436 | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.17) | 248 | 1.31 (1.07 to 1.60) | |

| ≥40.0 | 195 | 1.05 (0.84 to 1.30) | 148 | 1.40 (1.06 to 1.84) | |

| P value* | 0.762 | 0.002 | |||

| 12 g/day increase | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.07) | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.12) | |||

| P value for trend† | 0.204 | 0.002 | |||

Models were mutually adjusted for wine, beer, spirits, and fortified wine, and stratified by centre and sex, and systematic adjustment was undertaken for age at recruitment, body mass index, height, physical activity, smoking status, and history of hypertension. Models for wine and beer consumptions were mutually adjusted, and also included spirits, liquors, and fortified wine consumption.

P value for the Wald test statistics compared with a χ2 distribution with four degrees of freedom, not including the category of alcohol subtype non-drinkers (<0.1 g/day).

P value for types of alcohol at baseline modelled as a linear variable, with inclusion in the model of indicator variables expressing alcohol subtype consumption.

Interaction with smoking

Smoking was associated with all cardiovascular disease events, with stronger hazard ratio estimates comparing current to never smokers observed for fatal CHD (hazard ratio 2.97, 95% confidence interval 2.53 to 3.50) and non-fatal CHD (2.24, 2.05 to 2.45) than stroke (1.76, 1.61 to 1.92). A test for interaction between alcohol intake and smoking was of borderline statistical significance for non-fatal stroke (P=0.02), but there was no evidence of such an interaction for non-fatal CHD (P=0.46), as reported in supplementary table 2.

Sensitivity analyses

After exclusion of the first two years of follow-up, the associations between baseline alcohol consumption and non-fatal CHD and stroke were little changed, as shown in supplementary table 4. Alcohol consumption had inverse associations of similar magnitude with non-fatal and overall myocardial infarction. The inverse association for non-fatal myocardial infarction was confirmed in centres that did not assess incident angina, with a hazard ratio of 0.91 per 12 g/day increase (95% confidence interval 0.88 to 0.94, P<0.001 for trend). In centres that assessed angina the associations were weaker, with a hazard ratio of 0.97 per 12 g/day increase (0.93 to 1.01, P=0.100 for trend). Further adjustment for known history of cancer and diabetes at baseline did not appreciably change the results (data not shown). Analyses by country indicated that the associations between baseline alcohol consumption and risk of non-fatal and fatal CHD and stroke were not materially different across countries (see supplementary figure 1).

Discussion

The association between alcohol consumption and the risk of incident non-fatal and fatal coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke was evaluated among individuals without cardiovascular disease (CVD) at baseline in eight European countries in the EPIC-CVD study. While baseline and lifetime alcohol consumption were inversely associated with non-fatal CHD risk, alcohol intake was positively associated with non-fatal stroke.

In this study, wine intake and beer intake had broadly similar inverse associations with non-fatal CHD. By contrast, beer intake was positively associated with the risk of non-fatal stroke while its association with wine intake was unclear. Country specific hazard ratio estimates for risk of stroke in predominantly wine consuming countries (eg, Italy) were similar to hazard ratios in predominantly beer consuming countries (eg, Germany and Denmark), arguing against confounding by geographical region. These findings are consistent with evidence from a meta-analysis evaluating the relation between types of alcohol and non-fatal and fatal cardiovascular outcomes.22 Wine intake has been associated with lower oxidative stress levels, putatively through the activity of antioxidants found in wine such as polyphenols.23 24 25 However, in the EPIC study information on the type of wine consumed (ie, red or white) is not available.

In our analysis, smoking was strongly positively associated with the risk of CHD and stroke, which is consistent with existing evidence.26 27 28 In line with previous observations,29 30 our findings suggested that alcohol consumption and smoking have independent associations with the risk of non-fatal CHD.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

This is the first population based study assessing the association between baseline and lifetime alcohol consumption and the risk of non-fatal and fatal CHD and stroke in a pan-European prospective investigation. Our findings reinforce previous evidence of the association between alcohol consumption and the risk of CHD in the Spanish population.31 Our analysis included a comparatively large number of incident CHD and stroke events (after exclusion of prevalent CVD at baseline), and controlled for several potential confounding factors. We harmonised exposure data across participating countries on alcohol consumption, smoking status, and other lifestyle characteristics, and studied validated CVD outcomes.

A controversial element in the evaluation of the association between alcohol consumption and CVD has been the observation that non-drinkers (<0.1 g/day) are at higher risk of CVD than moderate drinkers. We adopted several approaches to help limit potential bias involved in the study of never-drinkers (who might differ systematically from drinkers in ways that are difficult to measure, but which might be relevant to disease causation) and of ex-drinkers (a category that includes people who might have abstained from alcohol owing to poor health itself, as well as those who changed their habits to achieve a healthier lifestyle).32 33 Firstly, we studied lifetime alcohol consumption (available for 76% of study participants) to help limit the potentially distorting effects of changes in alcohol intake due to pre-existing morbid conditions at the baseline survey. Secondly, statistical tests and dose-response relations were evaluated on current alcohol drinkers, and light alcohol drinkers (0.1-4.9 g/day) were consistently set as the reference category. Thirdly, in analyses on lifetime alcohol consumption, former and never drinkers were separated out, yet showed similar non-fatal CHD and stroke risks compared with baseline light drinkers (see supplementary table 2). Lastly, we showed our results were robust to a variety of additional sensitivity analyses, including the exclusion of the first two years of follow-up (to limit potential reverse causation), additional adjustment for baseline history of cancer and diabetes, and exclusion of participants with a history of angina.

Nevertheless, our study had potential limitations. Despite attempts to control for many confounders, residual confounding could still affect the observed associations, particularly owing to factors related to socioeconomic status, which are difficult to assess. In the EPIC study, alcohol measurements at baseline showed relatively high validity,16 but we cannot discount the possibility of misclassification of alcohol intake (for example, under-reporting). Our study could not investigate the relevance of specific drinking patterns, such as binge drinking or regular drinking during meals. Large studies in progress in East Asian populations, where common genetic variants predict 20-fold differences in drinking prevalence, should help to clarify whether alcohol intake is causally or artefactually associated with CVD outcomes.34

Comparison with other studies

Although a previous cohort-wide analysis of the EPIC study reported no strong association between lifetime alcohol consumption and cardiovascular mortality, that analysis included four times fewer cardiovascular outcomes than the present analysis and did not consider non-fatal events.30 Data from the EPIC-CVD case-cohort study have contributed to a recent combined analysis of 83 prospective studies. In contrast with the current study, however, that combined analysis could not focus systematically on lifetime alcohol consumption or on different types of alcohol consumed.11 In a meta-analysis of 26 epidemiological studies (17 cohort and 9 case-control) on stroke morbidity and mortality, alcohol intake was positively associated with the risk of haemorrhagic and ischaemic stroke, similarly in men and women.10 In a large recent study conducted in the UK, heavy drinkers (defined as participants exceeding current UK guidelines for alcohol of 24 g/day and 16 g/day, for men and women respectively) compared with moderate drinkers (within the UK alcohol guidelines) showed hazard ratio estimates of 1.21 (95% confidence interval 1.08 to 1.35) for coronary heart death, 1.22 (1.08 to 1.37) for heart failure, 1.50 (1.26 to 1.77) for cardiac arrest, 1.11 (1.02 to 1.37) for transient ischaemic attack, 1.33 (1.09 to 1.63) for ischaemic stroke, 1.37 (1.16 to 1.62) for intracerebral haemorrhage, 1.35 (1.23 to 1.48) for peripheral arterial disease, and 0.88 (0.79 to 1.00) for myocardial infarction.4

Conclusions

Alcohol intake was inversely associated with the risk of non-fatal CHD but positively associated with the risk of different stroke subtypes, highlighting the opposing associations of alcohol intake with different CVD types. Given previous knowledge about alcohol intake’s positive association with all cause mortality and the risk of cancer, our results strengthen policies to reduce alcohol consumption.

What is already known on this topic

Most prospective studies solely assessed recent alcohol intake at the time of entry into a cohort

Moderate alcohol consumption has been associated with a lower risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), as well as a higher risk of cancer and all cause mortality

Alcohol consumption has been associated with a higher risk of total stroke, but evidence about stroke subtypes is limited

What this study adds

Associations with cardiovascular outcomes were broadly similar with average lifetime alcohol consumption as for baseline alcohol intake

Alcohol intake was inversely associated with the risk of non-fatal CHD, but there were positive and broadly similar associations with risk of ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke

Given the known positive association of alcohol intake with all cause mortality and the risk of cancer, the opposing associations of alcohol intake we found with different cardiovascular disease types strengthen the rationale for policies to reduce alcohol consumption

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarah Spackman (EPIC-CVD Data Manager, Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit) and Nicola Kerrison (InterAct Data Manager, MRC Epidemiology Unit) for their help with this project.

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary information: Supplementary tables 1-4 and figure 1

Contributors: AA, HB, AT, EW, RK, MS, SP, DP, RT, TJK, RCT, KO, WMMV, JRQ, AT, PM, LA, RS, NJW, ER, PF and JD collected, stored, and administered study participants’ information on lifestyle exposure within the EPIC study. NJW, CL, NGF, SJS, ASB, MS, ER, and JD designed the case-cohort study, and assessed and validated the cardiovascular disease (CVD) events within the EPIC-CVD study. CR, AMW, DM, MS, ASB, and PF performed the statistical analyses. CR, AMW, DM, MS, ASB, PF, RS, MJG, PB, and HF interpreted the results and prepared the first versions of the manuscript. All authors actively contributed to the final manuscript. PF is the guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by the Direction Générale de la Santé (French Ministry of Health) (grant GR-IARC-2003-09-12-01). EPIC-CVD has been supported by the European Union Framework 7 (HEALTH-F2-2012-279233), the European Research Council (268834), the UK Medical Research Council (G0800270 and MR/L003120/1), the British Heart Foundation (SP/09/002 and RG/08/014 and RG13/13/30194), and the UK National Institute of Health Research. The establishment of the random subcohort was supported by the EU Sixth Framework Programme (FP6) (grant LSHM_CT_2006_037197 to the InterAct project) and the Medical Research Council Epidemiology Unit (grants MC_UU_12015/1 and MC_UU_12015/5).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The ethical review boards of the International Agency for Research on Cancer and all local institutions where participants had been recruited gave approval for the study. All participants gave written informed consent.

Data sharing: Access to EPIC data and biospecimens can be found at http://epic.iarc.fr/access/index.php.

Transparency: The manuscripts’ guarantor (PF) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Naghavi M, Wang H, Lozano R, et al. GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;385:117-71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, Rayner M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: epidemiological update. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2929. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bell S, Daskalopoulou M, Rapsomaniki E, et al. Association between clinically recorded alcohol consumption and initial presentation of 12 cardiovascular diseases: population based cohort study using linked health records. BMJ 2017;356:j909. 10.1136/bmj.j909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med 2004;38:613-9. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bagnardi V, Zatonski W, Scotti L, La Vecchia C, Corrao G. Does drinking pattern modify the effect of alcohol on the risk of coronary heart disease? Evidence from a meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:615-9. 10.1136/jech.2007.065607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zheng Y-L, Lian F, Shi Q, et al. Alcohol intake and associated risk of major cardiovascular outcomes in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. BMC Public Health 2015;15:773. 10.1186/s12889-015-2081-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greenland P, Knoll MD, Stamler J, et al. Major risk factors as antecedents of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease events. JAMA 2003;290:891-7. 10.1001/jama.290.7.891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Corrao G, Rubbiati L, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, Poikolainen K. Alcohol and coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Addiction 2000;95:1505-23. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951015056.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patra J, Taylor B, Irving H, et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of morbidity and mortality for different stroke types--a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2010;10:258. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wood AM, Kaptoge S, Butterworth AS, et al. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration/EPIC-CVD/UK Biobank Alcohol Study Group Risk thresholds for alcohol consumption: combined analysis of individual-participant data for 599 912 current drinkers in 83 prospective studies. Lancet 2018;391:1513-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Riboli E, Hunt KJ, Slimani N, et al. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): study populations and data collection. Public Health Nutr 2002;5(6b):1113-24. 10.1079/PHN2002394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Danesh J, Saracci R, Berglund G, et al. EPIC-Heart EPIC-Heart: the cardiovascular component of a prospective study of nutritional, lifestyle and biological factors in 520,000 middle-aged participants from 10 European countries. Eur J Epidemiol 2007;22:129-41. 10.1007/s10654-006-9096-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Langenberg C, Sharp S, Forouhi NG, et al. InterAct Consortium Design and cohort description of the InterAct Project: an examination of the interaction of genetic and lifestyle factors on the incidence of type 2 diabetes in the EPIC Study. Diabetologia 2011;54:2272-82. 10.1007/s00125-011-2182-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Investigators WMPP, WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators The World Health Organization MONICA Project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): a major international collaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41:105-14. 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90084-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaaks R, Slimani N, Riboli E. Pilot phase studies on the accuracy of dietary intake measurements in the EPIC project: overall evaluation of results. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Epidemiol 1997;26(Suppl 1):S26-36. 10.1093/ije/26.suppl_1.S26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Slimani N, Ferrari P, Ocké M, et al. Standardization of the 24-hour diet recall calibration method used in the european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC): general concepts and preliminary results. Eur J Clin Nutr 2000;54:900-17. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferrari P, Jenab M, Norat T, et al. Lifetime and baseline alcohol intake and risk of colon and rectal cancers in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC). Int J Cancer 2007;121:2065-72. 10.1002/ijc.22966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prentice RL. A case-cohort design for epidemiologic cohort studies and disease prevention trials. Biometrika 1986;73:1-11 10.1093/biomet/73.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barlow WE. Robust variance estimation for the case-cohort design. Biometrics 1994;50:1064-72. 10.2307/2533444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stata Statistical Software Release 12. Version. StataCorp. College Station TSL, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Di Castelnuovo A, Rotondo S, Iacoviello L, Donati MB, De Gaetano G. Meta-analysis of wine and beer consumption in relation to vascular risk. Circulation 2002;105:2836-44. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000018653.19696.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Booyse FM, Pan W, Grenett HE, et al. Mechanism by which alcohol and wine polyphenols affect coronary heart disease risk. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17(Suppl):S24-31. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arranz S, Chiva-Blanch G, Valderas-Martínez P, Medina-Remón A, Lamuela-Raventós RM, Estruch R. Wine, beer, alcohol and polyphenols on cardiovascular disease and cancer. Nutrients 2012;4:759-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pandey KB, Rizvi SI. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2009;2:270-8. 10.4161/oxim.2.5.9498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mons U, Müezzinler A, Gellert C, et al. CHANCES Consortium Impact of smoking and smoking cessation on cardiovascular events and mortality among older adults: meta-analysis of individual participant data from prospective cohort studies of the CHANCES consortium. BMJ 2015;350:h1551. 10.1136/bmj.h1551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V, Million Women Study Collaborators The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet 2013;381:133-41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61720-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sandhu RK, Jimenez MC, Chiuve SE, et al. Smoking, smoking cessation, and risk of sudden cardiac death in women. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2012;5:1091-7. 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.975219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ferrari P, Licaj I, Muller DC, et al. Lifetime alcohol use and overall and cause-specific mortality in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and nutrition (EPIC) study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005245. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hart CL, Davey Smith G, Gruer L, Watt GC. The combined effect of smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol on cause-specific mortality: a 30 year cohort study. BMC Public Health 2010;10:789. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arriola L, Martinez-Camblor P, Larrañaga N, et al. Alcohol intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in the Spanish EPIC cohort study. Heart 2010;96:124-30. 10.1136/hrt.2009.173419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fillmore KM, Kerr WC, Stockwell T, et al. Moderate alcohol use and reduced mortality risk: Systematic error in prospective studies. Addict Res Theory 2006;14:101-32 10.1080/16066350500497983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Naimi TS, Brown DW, Brewer RD, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and confounders among nondrinking and moderate-drinking U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med 2005;28:369-73. 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Millwood IY, Li L, Smith M, et al. Alcohol consumption in 0.5 million people from 10 diverse regions of China: prevalence, patterns and socio-demographic and health-related correlates. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: Supplementary tables 1-4 and figure 1