Abstract

Are individuals more sensitive to losses than gains in terms of economic growth? We find that measures of subjective well-being are more than twice as sensitive to negative as compared to positive economic growth. We use Gallup World Poll data from over 150 countries, BRFSS data on 2.3 million US respondents, and Eurobarometer data that cover multiple business cycles over four decades. This research provides a new perspective on the welfare cost of business cycles, with implications for growth policy and the nature of the long-run relationship between GDP and subjective well-being.

Keywords: economic growth, business cycles, subjective well-being

1 Introduction

This paper explores a simple question: is individual well-being more sensitive to losses than gains in terms of economic growth? We use subjective well-being data drawn from three large and complementary datasets to investigate whether economic downturns are associated with decreases in well-being that are significantly larger in magnitude than increases associated with equivalent upswings. Our analyses reveal an asymmetry in the manner in which individuals experience positive and negative macroeconomic fluctuations. We find that measures of life satisfaction and affect are more than twice as sensitive to negative growth as compared to equivalent positive economic growth.

Since the seminal work of Easterlin (1974), the linkages between subjective well-being and national income have become the subject of a substantial research literature. Although evidence shows that across countries the relationship between per capita GDP and subjective well-being is roughly log-linear (Stevenson and Wolfers, 2008; Deaton, 2008; Helliwell et al., 2013), the time-series relationship remains the subject of an extended debate. Whilst subjective well-being tends to covary with macroeconomic variables (Di Tella et al., 2003, 2001), evidence of a long-run relationship between growth and happiness is mixed. Whereas some recent research identifies a positive relationship between the level of per capita GDP and subjective well-being over time (Sacks et al., 2012), others fail to find the significant relationship between growth and well-being over the long-run that one might expect given the cross-sectional and short-run time-series evidence (Easterlin et al., 2010; Layard, 2005; Graham, 2010). However, none of these contributions considers potential differences between positive and negative economic growth. In this paper, we find that the economic growth rate is significantly related to subjective well-being, but that the gradient is more than twice as steep when growth is negative compared to when it is positive.

A large behavioral literature shows that humans are prone to a ‘negativity bias,’ and has established—broadly—that “bad is stronger than good” (Baumeister et al., 2001). One famous example of this is that individuals typically display a form of “loss aversion,” in that ‘the aggravation that one experiences in losing a sum of money appears to be greater than the pleasure associated with gaining the same amount’ (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979, p. 279). In this paper, we relax the implicit assumption of a symmetric association between positive and negative growth rates and measures of subjective well-being, and find that individuals are more sensitive to economic downturns than they are to equivalent upswings.

We analyse data from three large data sets—the Eurobarometer, the Gallup World Poll, and the US Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)—and employ piecewise (or ‘segmented’) regression models that introduce separate terms for macroe-conomic gains and losses. These datasets are three of the largest subjective well-being surveys available, and are complementary in that they each contribute a different setting to test for asymmetric sensitivity to gains and losses in economic growth. The Euro-barometer and Gallup World Poll are both at the international level, with each totalling over one million individual observations. The Eurobarometer data begin in the early 1970s and cover multiple business cycles in 15 European countries, while the Gallup data are drawn from a shorter (2005–2013) time period but cover a wider range of over 150 countries. The BRFSS data consist of nearly 2.3 million observations drawn from samples of each US state between 2005 and 2010, allowing us to examine within-state variation in the economic growth rate. In the Eurobarometer and BRFSS we focus on evaluative self-reports of life satisfaction, whereas the Gallup World Poll asks respondents a number of questions designed to give a fuller picture of individuals’ well-being, allowing us to explore the effects of macroeconomic fluctuations on both emotional as well as evaluative elements of subjective well-being.

The findings contribute to various strands of literature in behavioral and macroeconomics. First, as noted above, the analysis relates to the expanding literature on economic growth and subjective well-being (e.g. Proto and Rustichini (2013); Stevenson and Wolfers (2013)). Although our analysis centers on the short-run relationship between the economic growth rate and subjective well-being, the finding of an asymmetry allows us to revisit the longstanding debate on the long-run relationship. The “Easterlin Paradox” resulting from the conflicting findings in the short-term versus long-term can perhaps be better understood in light of our findings on “macroeconomic loss aversion,” in that short periods of recession have the ability to undo any well-being gains from longer expansionary periods, potentially leading to a non-significant relationship between national income and average well-being when considered in the long-run.

Second, this work addresses the welfare cost of business cycles (Lucas, 1987, 2003). The use of an ‘experienced utility’ rather than a ‘decision utility’ measure (Kahneman et al., 1997) means that welfare is considered here in terms of subjective well-being rather than consumption. Although these welfare measures show considerable overlap (Benjamin et al., 2012), their relationships to the business cycle contrast. The difference between volatile versus smooth growth in terms of consumption is often considered small (Otrok, 2001; Lucas, 2003),1 but the psychological impact of volatile growth on individual well-being is mostly overlooked. One notable exception to this is Wolfers (2003), who uses subjective well-being data to estimate the welfare cost of volatility, finding that greater unemployment volatility undermines well-being and that the same holds to a lesser extent for inflation. To our knowledge, there is no in-depth study that allows for a heterogeneous association of positive and negative growth with subjective well-being. Doing so offers insight into the underlying mechanism that drives the welfare cost of volatile versus smooth business cycles on well-being.

Third, the analysis relates to the classic behavioral finding of individual loss aversion, which underpins Prospect Theory (Tversky and Kahneman, 1991) and has by now been demonstrated in a variety of settings (Barberis, 2013). While Prospect Theory suggests that prospective losses loom larger than equivalent prospective gains in determining individuals’ decisions and actions, we observe that individuals also experience real losses more acutely than gains, at least in a macroeconomic context. That is, rather than appealing to the concept of ‘decision utility’ and seeking to reveal loss averse preferences through individuals’ choices and behavior, we employ subjective well-being data to proxy ‘experienced utility’ and show that a greater welfare weight is placed on national income losses as compared to equivalent gains. Although experimental evidence shows that individuals make decisions based on the anticipation that the experience of a loss will be more acute than that of a comparable gain, Kahneman (1999, p. 19) nevertheless notes that ‘the extent to which loss aversion is also found in experience is not yet known.’ Indeed, some have posited that loss averse preferences may simply reflect an ‘affective forecasting error’ explained by individuals overestimating the impact that losses will eventually have (Kermer et al., 2006; Rick, 2011). Instead, we show that economic downturns have a greater influence on well-being than equivalent economic growth. While our study focuses on macroeconomic fluctuations, related research has explored microeconomic effects on subjective well-being of gains and losses in personal income and status (Boyce et al., 2013; Di Tella et al., 2010; Vendrik and Woltjer, 2007).

Finally, the findings contribute to research into the well-being impact of the recent Great Recession, which has identified large psychological costs associated with economic downturns (Deaton, 2012; Montagnoli and Moro, 2014; Graham et al., 2010). For example, Deaton (2012) uses individual daily self-reports of well-being in the USA between 2008 and 2011 to show that subjective well-being declined sharply when GDP fell and unemployment rose. In a similar vein, Stuckler et al. (2011) show that economic downturns are associated with decreases in mental and physical health, while Barr et al. (2012) find evidence of an increased prevalence of suicide. Importantly, however, these studies do not consider whether economic downturns have a disproportionate effect on subjective well-being as compared to economic upswings.

The paper is structured as follows. Sections II and III outline the data and methods used to derive our results, which are presented in section IV. Section V includes follow-up analyses that explore possible mechanisms underlying the asymmetric experience of negative and positive growth as well as a discussion of the scholarly and policy implications.

2 Data

2.1 Subjective Well-being

In order to examine how macroeconomic fluctuations are experienced by individuals and investigate the welfare costs of periodic downturns, we use subjective well-being data as a welfare measure. Economic research using subjective well-being—or “happiness”— data is burgeoning,2 but such cardinal measures of ‘experienced utility’ remain distinct from the neoclassical notion of welfare that uses ordinal measures of ‘decision utility’ by way of revealed preferences (Kahneman et al., 1997; Rabin, 1998; Kahneman and Thaler, 2006; Fleurbaey and Blanchet, 2013). More recent work compares and bridges notions of experienced and decision utility. Evidence presented by Benjamin et al. (2012) suggests that measures of subjective well-being—and ‘life satisfaction’ in particular—are relatively good predictors of choice and can potentially be considered as a proxy (albeit an imperfect one3) for the standard concept of decision utility (see also Benjamin et al., 2014; Perez-Truglia, 2010; Charpentier et al., 2016). For a summary of the variety of ways in which the validity and reliability of subjective well-being measures have been demonstrated, see Krueger and Stone (2014).

Self-reported well-being can be broadly subdivided into evaluative and emotional measures (see Kahneman and Deaton, 2010, for a discussion). In line with the literature on macroeconomics and subjective well-being, we focus primarily on evaluative measures. In the BRFSS and Eurobarometer, we use responses to a life satisfaction question, and in the Gallup World Poll we employ answers to a Cantril Ladder question. Nevertheless, our analysis also considers the association of economic growth with emotional measures of well-being. The Gallup survey asks respondents a number of different questions designed to capture various dimensions of human well-being, allowing us to assess the experience of economic ups and downs by varied measures of positive and negative affect.

To be able to compare results more easily across our three analyses, we standardize the well-being scales within each dataset, such that they each have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. Table 1 to 3 report descriptive statistics of the main variables. More detailed summary statistics broken down by country/state are reported in an online appendix.

Table 1.

Gallup World Poll

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Ladder | 1,166,517 | 5.484 | 2.223 | 0 | 10 |

| Future Ladder | 1,074,085 | 6.740 | 2.368 | 0 | 10 |

| Happiness | 806,864 | 0.688 | 0.463 | 0 | 1 |

| Enjoyment | 1,169,277 | 0.698 | 0.459 | 0 | 1 |

| Sadness | 1,155,071 | 0.207 | 0.405 | 0 | 1 |

| Stress | 1,057,236 | 0.289 | 0.453 | 0 | 1 |

| Worry | 1,156,273 | 0.338 | 0.473 | 0 | 1 |

| Economic Growth | 968 | 0.041 | 0.055 | −0.180 | 1.045 |

| Negative Growth | 123 | 0.035 | 0.037 | −0.180 | 0 |

| Positive Growth | 845 | 0.052 | 0.048 | 0 | 1.045 |

| GDP per capita (US$2005) | 968 | 10,741 | 15,242 | 150 | 81,852 |

| Inflation Rate | 961 | 0.061 | 0.081 | −0.727 | 1.570 |

| Unemployment Rate | 961 | 0.085 | 0.062 | 0.001 | 0.475 |

2.1.1 Gallup World Poll

The Gallup World Poll is a large-scale repeated cross-sectional survey covering more than 150 countries (although not all countries participated in all waves4). The period covered in our analysis is 2005–2013. All samples in the Gallup World Poll are probability based and nationally representative of the resident population aged 15 and older. The typical Gallup World Poll survey wave interviews 1,000 individuals.5

The main evaluative subjective well-being question of interest we use in this paper is the standard Cantril Self-Anchoring Striving Scale (Cantril, 1965).6 Further questions focus on affective or emotional well-being, and ask respondents whether they felt “happiness/sadness/worry/stress/anger/enjoyment/love a lot of the day yesterday?” These questions illicit a dichotomous yes/no response. We concentrate on two such measures of negative affect (whether respondents felt “worry”, or “stress” yesterday) and two of positive affect (whether respondents felt “happy” or “enjoyment”).

2.1.2 Eurobarometer

The Eurobarometer is an opinion survey carried out on behalf of the European Commission that has typically, though not always, been conducted twice each year. For each wave, a random sample of approximately 1,000 individuals from each country in the European Union is interviewed on a range of issues including how satisfied they are with the life they lead. The response options are: very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied, and not at all satisfied. This four category subjective well-being question has been included at least once every year from 1973 to 2013, apart from 1974, and is translated for our purposes onto a 1–4 scale (on which 4 corresponds to the “very satisfied” response). The Eurobarometer began with 9 countries and has grown over time along with the expansion of the EU. The data we use in this analysis come from the 15 longest-serving members of the EU (the so-called EU-15), for which the minimum time-series is 18 years and the maximum 39 years as represented in Figure A1.7

2.1.3 BRFSS

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is carried out by the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States, and its primary aim is to collect data on the most important risk factors leading to premature death, such as cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and hypertension. A four category life satisfaction question—with response categories: very satisfied, satisfied, dissatisfied, very dissatisfied—was included from 2005 until 2010. The BRFSS samples a large number of US individuals with approximately 400,000 respondents per year, divided across the different states and different months of the year (totaling approximately 2.3 million respondents).

2.2 Macroeconomic Data

The principal source of macroeconomic data for the two international panels is the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. GDP is measured per capita in purchasing power parity (PPP) constant 2005 US dollars. Unemployment and inflation data are drawn from the same source, with any gaps being filled where possible using data from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database and the OECD. For the two international datasets, macroeconomic data points correspond to country-years. The BRFSS data is matched with macroeconomic data at the state-quarter level. Population data per US state is provided by STATS Indiana (stats.indiana.edu) and quarterly state personal income per capita data are taken from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, and quarterly state-level unemployment data as well as quarterly nationwide inflation data are both drawn from the Bureau of Labour Statistics.

3 Empirical Estimation

To investigate the relationship between economic growth and subjective well-being we estimate the baseline equation

| (1) |

where SWBijt is a subjective well-being measure of individual i in country j in year t in the international panels, and the subjective well-being of individual i in U.S. state j in quarter t in the BRFSS sample. GROWTHjt is the rate of economic growth from year t-1 to year t calculated by the World Bank (or in the US sample it is the quarter-to-quarter economic growth rate). is a vector of individual-level demographic characteristics that are known to influence self-reports of well-being, such as age, gender, education level and marital status. ξj is a country/US state fixed effect. γt is a survey-wave fixed effect in the international panels, or a seasonal dummy in the case of the BRFSS. εijt is the error term, clustered on country-years (state-quarters).

Country(state)-specific intercepts diminish the threat of omitted variable bias by controlling for unobserved heterogeneity across countries (states), such that time-invariant factors like culture and climate are controlled for. Survey-specific intercepts are included in order to control for common shocks as well as to partial out variance in survey design over time. Deaton (2012) shows that question ordering and context effects are typically substantial in relation to subjective well-being questions (see also Sacks et al., 2013; Schwarz and Strack, 1999).

To test for any asymmetric effects of economic growth, we then fit a piecewise linear regression model that introduces separate terms for negative and positive growth, such that

| (2) |

where X+ is equal to economic growth in country-years (state-quarters) in which growth is positive, 0 otherwise; and X− is equal to the economic growth rate where growth is negative, 0 otherwise. We use the absolute value of negative growth in order to make the direction of the resulting coefficients more intuitive to interpret - an “increase” in negative growth corresponds to a negative change in well-being.8

Our main contribution to the debate on the relationship between growth and well-being is to provide empirical analyses that relax the implicit assumption of a symmetric association between positive and negative growth on the one hand, and measures of subjective well-being on the other. In line with the literature, the core of the analysis is reduced-form. Indeed, both the causes and consequences of fluctuations in GDP can be numerous, and are likely to vary across both time and space. For example, recessions can lead to high unemployment and/or inflation, macroeconomic factors both shown to be good predictors of subjective well-being (Di Tella et al., 2001), whilst economic growth has also been shown to reduce inequalities of subjective well-being within countries over time (Clark et al., 2016). Equally, adverse economic and labour market conditions can also lead to social tensions and changing attitudes that might have an impact on subjective well-being. One might imagine that a multitude of studies, both micro-case studies as well as more macro-oriented studies, will be needed to thoroughly understand the effects of all these factors on subjective well-being. Nevertheless, as a first step towards understanding the mechanisms behind a disproportionate association of negative growth and well-being, we introduce various macroeconomic covariates (unemployment rate, household consumption growth, and inflation rate)9 into the equation as well as considering the impact of individuals’ self-reported financial distress and their current expectations about the future of the economy.

4 Results

4.1 Baseline

Our main result is that, across all three data sets, subjective well-being is more sensitive to decreases in national income than it is to equivalent increases. Table 4 shows that evaluative subjective well-being is positively and significantly associated with the economic growth rate. Introducing separate terms for positive and negative growth—and thus allowing the slope gradient to differ for economic gains and losses—we find in all three data sets that the statistical relationship between economic growth and well-being appears to be driven principally by episodes of negative growth. The negative growth terms are greater in both magnitude and statistical significance.10

Table 4.

Economic Growth and Well-Being

| Gallup World Poll | Eurobarometer | BRFSS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Cantril Ladder | Life Satisfaction | Life Satisfaction | ||||

| Economic Growth | 0.561*** | 2.312*** | 0.436*** | |||

| (0.168) | (0.435) | (0.075) | ||||

| Negative Growth | −1.354*** | −5.788*** | −0.489*** | |||

| (0.340) | (1.293) | (0.146) | ||||

| Positive Growth | 0.233 | 0.913** | 0.357*** | |||

| (0.201) | (0.375) | (0.134) | ||||

| Countries/States | 157 | 157 | 15 | 15 | 51 | 51 |

| Macro observations | 968 | 968 | 508 | 508 | 1233 | 1233 |

| Micro observations | 1,166,517 | 1,166,517 | 1,092,999 | 1,092,999 | 2,260,476 | 2,260,476 |

| R2 | 0.034 | 0.034 | 0.030 | 0.031 | 0.060 | 0.060 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses, adjusted for clustering at the country-year level in the Gallup and Eurobarometer, and at the state-quarter level in the BRFSS. All outcomes variables are standardised (mean=0, SD=1). Gallup World Poll data is collected between 2005–2013; Eurobarometer 1973–2013; BRFSS 2005–2010. All regressions include individual-level controls: age, age-squared, education level, gender, marital status. Country fixed effects and survey wave dummies are included in all of the Eu-robarometer and Gallup models; state fixed effects and seasonal dummies are included in the BRFSS models. Negative and Positive Growth terms are splines, such that negative (positive) growth is equal to the absolute value of the growth rate when it is negative (positive) and zero otherwise.

p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

To illustrate, using the Gallup sample, we can see that a 10% economic contraction corresponds to a 0.135 standard deviation drop in life satisfaction, but an equivalent 10% expansion of the economy relates only to a statistically ill-defined increase of around 0.023 standard deviations. These estimates correspond to a 0.33 decrease and a 0.05 increase on the 0–10 Cantril Ladder scale, respectively. From a human well-being perspective, the results from the three data sets would suggest that some 2 to 6 percent of economic growth would be required to offset just 1 percent of economic contraction.

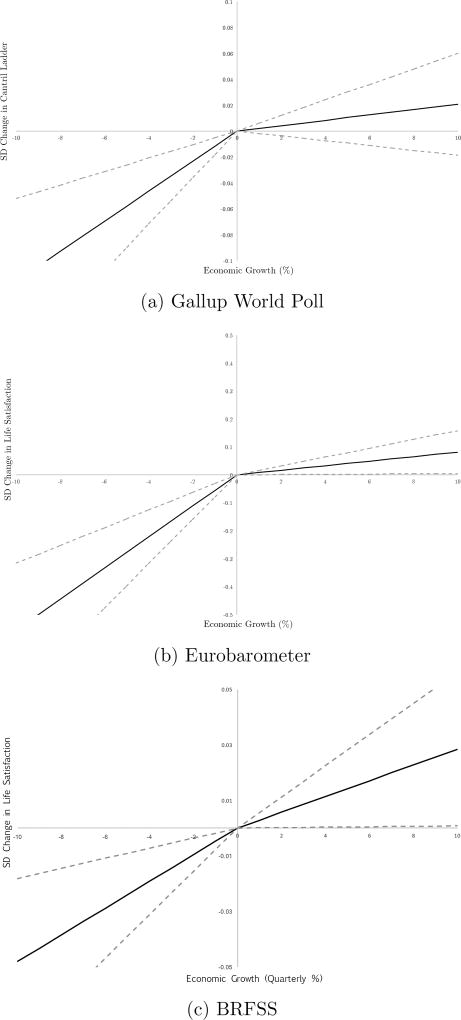

The asymmetry in the relationship between economic growth and well-being can be seen more clearly in Figure 1, which simply plots the coefficients for negative and positive growth separately on the x-axis, and subjective well-being on the y-axis. This representation looks similar to the well-known utility function of Prospect Theory—showing that losses loom larger than gains in decision utility (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). Here, Figure 1 suggests that individuals experience macroeconomic losses more acutely than equivalent gains in economic growth.

Figure 1. The Asymmetric Experience of Positive and Negative Growth.

Notes: Graphs plot the coefficients for negative and positive growth from regressions of evaluative SWB on splines of negative and positive growth, the level of log GDP per capita, a vector of personal controls, country/state fixed effects, and year/season dummies. These regressions correspond to model 2 of each of Tables 5, 6 and 7. See text for further details. 95% confidence intervals reported.

4.2 Addition of further macroeconomic covariates

Having observed an interesting correlational asymmetry in Table 4, we now move on to gradually introduce further macroeconomic variables into the equation. Two issues are of principal interest here: first, whether the short-run growth effect or long-run level effect of GDP dominates, and second, whether or not the disproportionate negative growth association is merely a reflection of the already well-established non-pecuniary negative effects of unemployment and inflation.

All three datasets, which cover different time-frames and sets of countries, produce similar results in Tables 5, 6, and 7. As one would expect, the unemployment rate is negatively associated with subjective well-being over time. In all three datasets, the introduction of the unemployment rate alongside economic growth leads to a reduction in the coefficient on negative growth, suggesting that at least some (though not all) of the association between negative growth and subjective well-being, which remains significantly different from zero, is mediated through increases in unemployment that occur during recessionary periods.

Table 5.

Gallup 2005–2013 - Addition of main macroeconomic indicators

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cantril Ladder | ||||||||

| Economic Growth | 0.481*** | 0.465*** | 0.517*** | 0.394** | ||||

| (0.162) | (0.165) | (0.167) | (0.168) | |||||

| Negative Growth | −1.159*** | −1.082*** | −1.136*** | −0.776** | ||||

| (0.325) | (0.352) | (0.322) | (0.323) | |||||

| Positive Growth | 0.208 | 0.214 | 0.274 | 0.249 | ||||

| (0.201) | (0.197) | (0.200) | (0.199) | |||||

| GDP per capita (log) | 0.295*** | 0.276*** | 0.124 | 0.117 | ||||

| (0.098) | (0.096) | (0.100) | (0.100) | |||||

| Unemployment Rate | −1.829*** | −1.767*** | −1.653*** | −1.625*** | ||||

| (0.298) | (0.298) | (0.333) | (0.333) | |||||

| Inflation Rate | −0.204 | −0.168 | −0.217 | −0.195 | ||||

| (0.143) | (0.140) | (0.147) | (0.147) | |||||

| Country and Wave FEs | x | x | x | X | x | x | x | x |

| Individual Controls | x | x | x | X | x | x | x | x |

| Countries | 157 | 157 | 156 | 156 | 156 | 156 | 155 | 155 |

| Country-years | 968 | 968 | 961 | 961 | 963 | 963 | 956 | 956 |

| Individuals | 1,166,517 | 1,166,517 | 1,158,490 | 1,158,490 | 1,158,549 | 1,158,549 | 1,150,522 | 1,150,522 |

| R2 | 0.035 | 0.035 | 0.035 | 0.035 | 0.034 | 0.034 | 0.035 | 0.035 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses, adjusted for clustering at the country-year level. Subjective well-being responses are standardised (mean=0, SD=1). Country fixed effects and survey wave dummies are included in all models. All regressions include individual-level controls: age, age-squared, education level, gender, marital status. Negative and Positive Growth terms are splines, such that negative (positive) growth is equal to the absolute value of the growth rate when it is negative (positive) and zero otherwise.

p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

Table 6.

Eurobarometer 1973–2013 - Addition of main macroeconomic indicators

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “On the whole, how satisfied are you with the life you lead?” | ||||||||

| Economic Growth | 2.172*** | 1.253*** | 2.198*** | 1.263*** | ||||

| (0.415) | (0.333) | (0.386) | (0.333) | |||||

| Negative Growth | −5.570*** | −3.687*** | −5.181*** | −3.688*** | ||||

| (1.227) | (0.910) | (1.199) | (0.921) | |||||

| Positive Growth | 0.814** | 0.360 | 1.025*** | 0.359 | ||||

| (0.392) | (0.342) | (0.361) | (0.349) | |||||

| GDP per capita (log) | 0.252*** | 0.239*** | −0.011 | −0.009 | ||||

| (0.079) | (0.074) | (0.071) | (0.067) | |||||

| Unemployment Rate | −2.417*** | −2.274*** | −2.382*** | −2.290*** | ||||

| (0.235) | (0.214) | (0.256) | (0.236) | |||||

| Inflation Rate | 1.133*** | 0.930*** | 0.113 | −0.010 | ||||

| (0.308) | (0.286) | (0.247) | (0.250) | |||||

| Country and Wave FEs | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Individual Controls | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Countries | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Country-years | 508 | 508 | 508 | 508 | 508 | 508 | 508 | 508 |

| Individuals | 1,092,999 | 1,092,999 | 1,092,999 | 1,092,999 | 1,092,999 | 1,092,999 | 1,092,999 | 1,092,999 |

| R2 | 0.030 | 0.031 | 0.033 | 0.034 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.033 | 0.034 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses, adjusted for clustering at the country-year level. Life satisfaction responses are standardised (mean=0, SD=1). Country fixed effects and survey wave dummies are included in all models. All regressions include individual-level controls: age, age-squared, education level, gender, marital status. Negative and Positive Growth terms are splines, such that negative (positive) growth is equal to the absolute value of the growth rate when it is negative (positive) and zero otherwise.

p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

Table 7.

BRFSS 2005–2010 - Addition of main macroeconomic indicators

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “In general, how satisfied are you with your life?” | ||||||||

| Economic Growth | 0.404*** | 0.392*** | 0.438*** | 0.380*** | ||||

| (0.077) | (0.072) | (0.075) | (0.073) | |||||

| Negative Growth | −0.481*** | −0.438*** | −0.487*** | −0.465*** | ||||

| (0.153) | (0.135) | (0.151) | (0.146) | |||||

| Positive Growth | 0.284* | 0.323** | 0.361** | 0.239* | ||||

| (0.141) | (0.129) | (0.142) | (0.142) | |||||

| GDP per capita (log) | 0.082*** | 0.086*** | 0.015 | 0.019 | ||||

| (0.029) | (0.030) | (0.033) | (0.034) | |||||

| Unemployment Rate | −0.198*** | −0.197*** | −0.200*** | −0.201*** | ||||

| (0.051) | (0.051) | (0.061) | (0.061) | |||||

| Inflation Rate | 0.036 | 0.009 | −0.122 | −0.172 | ||||

| (0.108) | (0.115) | (0.111) | (0.116) | |||||

| State and Season FEs | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Individual Controls | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| States | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 |

| State-quarters | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 |

| Individuals | 2,260,476 | 2,260,476 | 2,260,476 | 2,260,476 | 2,260,476 | 2,260,476 | 2,260,476 | 2,260,476 |

| R2 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.060 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses, adjusted for clustering at the state-quarter level. Life satisfaction responses are standardised (mean=0, SD=1). State fixed effects and season dummies are included in all models. Economic growth refers to the quarter-on-quarter growth rate. All regressions include individual-level controls: age, age-squared, education level, gender, marital status. Negative and Positive Growth terms are splines, such that negative (positive) growth is equal to the absolute value of the growth rate when it is negative (positive) and zero otherwise.

p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

Our findings in relation to the long-run level of income are mixed. In all three cases, once the level of (log) GDP per capita is introduced alongside the growth rate in columns (1) and (2), both level and change effects appear to be present. This is in line with much of the current literature, which tends to show a positive relationship between the level of per capita GDP and subjective well-being within countries over time (e.g. Sacks et al., 2012). This suggests that although people may respond to fluctuations in the short-term, and be particularly averse to periods of recession during the business cycle, overall economic development over time raises both living standards as well as subjective well-being. However, a note of caution in this is that once all the main macroeconomic indicators are included together in columns (7) and (8), the only significant predictors of subjective well-being are negative economic growth and the unemployment rate, with the level of GDP and inflation not significantly associated with evaluative self-reports of well-being.

Given that the BRFSS uses quarterly rather than yearly data, we also include in an online appendix a one quarter lag of the economic growth rate. The BRFSS results discussed above in our main tables are in line with the other two datasets, but the asymmetry is less immediately apparent than in the Gallup or Eurobarometer samples. One potential reason for this is the use of quarterly data, which may obscure any delayed well-being sensitivity to economic growth. Adding a one quarter lag of our growth terms confirms this, and these extended models give much stronger evidence of an asymmetric experience of negative and positive growth.

4.3 Positive and negative affect over the business cycle

The richness of the Gallup World Poll allows us in Tables 8 and 9 to go beyond the initial analysis of evaluative well-being, and examine how individuals experience economic expansions and contractions. We focus here on two positive and two negative emotions. The long-run level of (log) per capita GDP is not significantly related to the day-to-day emotional experience of individuals. However, emotional well-being is significantly related to macroeconomic movements over the business cycle. Regressing emotional well-being on the economic growth rate, we can see that short-run changes in GDP are associated with feelings of happiness, enjoyment, worry, and stress in the ways one might expect.

Table 8.

Gallup 2005–2013 - Positive Affect over the Business Cycle

| Panel A | Panel B | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Happiness | Enjoyment | |||||||

| Economic Growth | 0.158*** | 0.119* | 0.161*** | 0.121** | ||||

| (0.055) | (0.069) | (0.051) | (0.050) | |||||

| Negative Growth | −0.223*** | −0.116 | −0.356*** | −0.231** | ||||

| (0.084) | (0.093) | (0.080) | (0.092) | |||||

| Positive Growth | 0.119 | 0.120 | 0.080 | 0.079 | ||||

| (0.086) | (0.099) | (0.068) | (0.066) | |||||

| GDP per capita (log) | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.037 | 0.035 | ||||

| (0.073) | (0.073) | (0.029) | (0.029) | |||||

| Unemployment Rate | −0.434*** | −0.434*** | −0.232*** | −0.224*** | ||||

| (0.157) | (0.158) | (0.086) | (0.086) | |||||

| Inflation Rate | −0.050* | −0.050** | −0.048** | −0.042* | ||||

| (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.024) | (0.025) | |||||

| Country and Wave FEs | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Individual Controls | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Countries | 151 | 151 | 150 | 150 | 156 | 156 | 154 | 154 |

| Country-years | 625 | 625 | 616 | 616 | 967 | 967 | 955 | 955 |

| Individuals | 806,864 | 806,864 | 793,802 | 793,802 | 1,169,277 | 1,169,277 | 1,153,213 | 1,153,213 |

| R2 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.017 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses, adjusted for clustering at the country-year level. Outcome variables are dichotomous yes/no answers to the question “Did you feel happy/enjoyment a lot yesterday?” Country fixed effects and survey wave dummies are included in all models. All regressions include individual-level controls: age, age-squared, education level, gender, marital status. Negative and Positive Growth terms are splines, such that negative (positive) growth is equal to the absolute value of the growth rate when it is negative (positive) and zero otherwise.

p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

Table 9.

Gallup 2005–2013 - Negative Affect over the Business Cycle

| Panel A | Panel B | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Worry | Stress | |||||||

| Economic Growth | −0.156*** | −0.128** | −0.079* | −0.054 | ||||

| (0.050) | (0.050) | (0.047) | (0.051) | |||||

| Negative Growth | 0.359*** | 0.266** | 0.328*** | 0.275** | ||||

| (0.124) | (0.127) | (0.120) | (0.128) | |||||

| Positive Growth | −0.070 | −0.075 | 0.034 | 0.034 | ||||

| (0.065) | (0.062) | (0.065) | (0.067) | |||||

| GDP per capita (log) | −0.004 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.005 | ||||

| (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.032) | (0.033) | |||||

| Unemployment Rate | 0.503*** | 0.493*** | 0.594*** | 0.580*** | ||||

| (0.107) | (0.108) | (0.143) | (0.143) | |||||

| Inflation Rate | 0.021 | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.000 | ||||

| (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.019) | (0.021) | |||||

| Country and Wave FEs | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Individual Controls | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Countries | 157 | 157 | 155 | 155 | 156 | 156 | 154 | 154 |

| Country-years | 967 | 967 | 956 | 956 | 889 | 889 | 878 | 878 |

| Individuals | 1,156,273 | 1,156,273 | 1,142,209 | 1,142,209 | 1,057,236 | 1,057,236 | 1,044,172 | 1,044,172 |

| R2 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.009 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses, adjusted for clustering at the country-year level. Outcome variables are dichotomous yes/no answers to the question “Did you feel worry/stress a lot yesterday?” Country fixed effects and survey wave dummies are included in all models. All regressions include individual-level controls: age, age-squared, education level, gender, marital status. Negative and Positive Growth terms are splines, such that negative (positive) growth is equal to the absolute value of the growth rate when it is negative (positive) and zero otherwise.

p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

However, once we split the growth term into positive and negative splines, it is noticeable that these relationships are in all four cases driven exclusively by periods of economic contraction. Negative growth years are significantly associated with decreases in happiness and enjoyment, and increases in worry and stress, experienced by respondents during those periods. Yet, positive growth does not seem to be related either to increased happiness and enjoyment or reduced worry and stress.

5 Discussion

Our analysis suggests that measures of subjective well-being are more than twice as sensitive to economic contractions as compared to equivalent expansions. An important initial concern is that this main finding may be driven largely—or even entirely—by the Great Recession of the late 2000s, potentially limiting the generalizability of our results. Clearly, the main recessionary periods covered in the Gallup (2005–2013) and BRFSS (2005–2010) data do relate to this unusually deep recessionary period. One advantage of the Eurobarometer data, however, is that we are able to study multiple business cycles over four decades going back to the 1970s. In Table A.1 we use this dataset in order to test the robustness of our findings to the omission of the Great Recession. Omitting the 2007–2009 period from the analysis, we find that the asymmetric relationship between negative/positive growth and SWB is evident in the data even when leaving this period out of the sample.

Mechanisms

In line with previous research on macroeconomic growth and subjective well-being, the analysis of this paper is reduced-form. Further research is required in order to understand why macroeconomic fluctuations have an asymmetric effect on subjective well-being. The questions of why individuals experience macroeconomic losses more negatively than they experience equivalent gains positively, as well as whether this relationship is causal, are beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, we suggest several possible avenues for further research in order to address this important follow-up question.

One conjecture is that there is a pure behavioral “loss aversion” effect. Indeed, one deep-rooted mechanism could be that individuals simply react more strongly to negative developments. Humans’ disproportionate sensitivity to negative stimuli and the general finding that “bad is stronger than good” (Baumeister et al., 2001) may have an explanation rooted in evolutionary biology (McDermott et al., 2008), since the avoidance of threats can be most important for survival.

An important potential alternative—or complementary—explanation is that the asymmetry is driven at least in part by the non-pecuniary negative effects of unemployment (Clark and Oswald, 1994; Kassenboehmer and Haisken-DeNew, 2009; Winkelmann and Winkelmann, 1998), which typically increases during recessions. Including the unemployment rate as a covariate in our analysis, we find that some of the association between the negative growth rate and subjective well-being is indeed driven by unemployment. However, not all of the disproportionate association of downturns and well-being can be explained in this way, suggesting that further mechanisms may be driving the results.

Periods of economic contraction not only involve a loss of national income but also an increase in economic uncertainty (Bloom, 2009, 2014). One non-psychological conduit between recessions and subjective well-being may simply be consumption behavior. Economic uncertainty may lead individuals to consume fewer goods and services compared to any increases brought about by equivalent economic upswings, thus leading to disproportionate losses of well-being that are at least to some extent linked to the enjoyment of consumption. Rosenblatt-Wisch (2008), for example, shows that negative growth has a disproportionate effect on consumption (see also Bowman et al., 1999; Foellmi et al., 2011). We are able to test this potential conduit using the Eurobarometer and Gallup data by introducing the annual growth rate in household consumption expenditure per capita into our baseline equation. In an online appendix we show that consumption is significantly associated with subjective well-being; however, the asymmetric experience of negative and positive growth is robust to the inclusion of consumption growth, suggesting that this mechanism is unable to explain all of the disproportionate association between negative growth and well-being.

A more psychological explanation is that the uncertainty has a direct effect upon subjective well-being. For example, Luechinger et al. (2010) highlight the role of economic insecurity in increasing angst and stress by showing that the subjective well-being of employed individuals working in the public sector, who in general enjoy more job protection, is less acutely affected by economic shocks than comparable workers in the private sector.11 To assess whether this instability mechanism is able to explain away the apparent behavioral loss aversion effect, we exploit the fact that the Eurobarometer and Gallup World Poll include (in some though not all survey waves) questions on future economic expectations. In an online appendix we introduce dummies for positive and negative economic expectations (omitting the neutral category) into our baseline equation. These regressions suggest expectations about the future do indeed have an effect on current subjective well-being, with negative expectations having a stronger impact. Nevertheless, the baseline result of an asymmetric experience of negative and positive growth is robust to the inclusion of these current expectations.

Related to this is the notion that negative growth has a disproportionate effect upon individuals’ feelings of financial distress. To begin to test this proposition, we take advantage of a question included in multiple rounds of the Gallup World Poll that surveys respondents’ on their feelings about their household level of income—whether they are living comfortably, getting by, finding it difficult, or finding it very difficult. We find that introducing this variable into our principal equation brings down the coefficient on negative growth by around a quarter (see online appendix for details), suggesting that at least part of the large negative growth effect can be explained through this channel.

The long-run income-happiness relationship

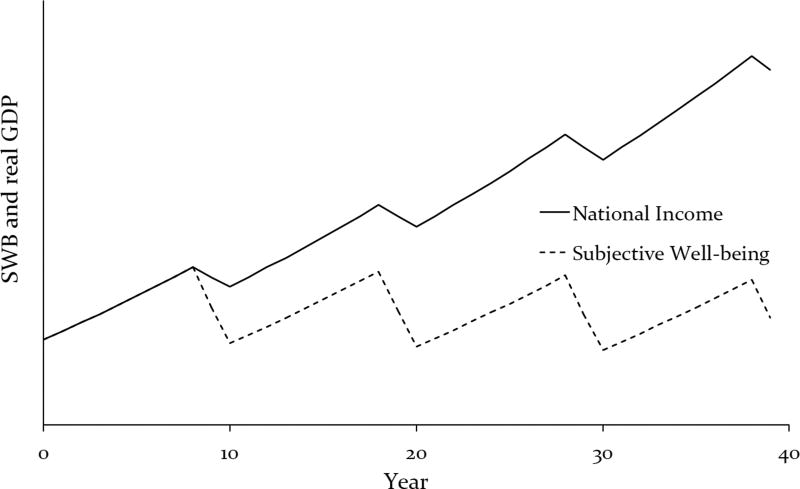

Our main analysis is firmly rooted in the short-run year-to-year fluctuations of the macroeconomy. Nevertheless, an important line of further research should focus on the extent to which the short-run asymmetry in the subjective experience of negative and positive growth can contribute to the longstanding debate on the long-run GDP-happiness relationship. Periodic recessions have the ability to undo any well-being gains from longer expansionary periods. If these losses are disproportionately large enough, they have the potential to lead to an insignificant relationship between national income and average well-being when considered in the long run. To illustrate, imagine a 10-year business cycle consisting of 8 years of positive growth followed by two recessionary years. If we treat positive and negative growth as qualitatively the same (i.e. we assume the magnitude of the slopes to be equal), then we would expect to see a general upward trend much like that of real national income. However, if people are four times more sensitive to negative growth, then the well-being gains accumulated over the 8 years of positive growth can be wiped out by just 2 years of negative growth. Over the whole cycle (and over multiple cycles), despite the short-run relationship, the net change in aggregate life satisfaction can be zero. This dynamic can be seen in the stylized theoretical representation of national income and subjective well-being shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Theoretical representation of the asymmetric experience of positive and negative growth over the business cycle

It is worth noting that this explanation relies not only upon negative growth doing disproportionate damage during recessionary periods, as our analysis suggests, but also on the proposition that extended periods of strictly positive growth have the ability to raise national levels of subjective well-being. To begin to investigate this more concretely we replace the year-to-year growth rate as the main predictor of SWB in our baseline equation with long-run changes in (log) GDP per capita. Moreover, we can then allow the magnitude of the long-run Δ GDP coefficient to vary according to whether the long run expansion occurred through a sequence of strictly positive growth years, or through a series of gains and losses. When we do so using the Eurobarometer data, we find evidence—reported in Table A.3—that strictly positive growth spells are associated with rising SWB whereas growth spells obtained by way of ups and downs are less clearly conducive to increases in life satisfaction.12

Of course, we do not expect this dynamic to entirely explain away the apparent paradox, and offer it rather as a complementary explanation along with the two most prominent accounts, namely the psychological mechanisms of hedonic adaptation and social comparison (see Clark et al., 2008). Several avenues of further research will be required in order to investigate the interactive dynamics between loss aversion, adaptation and social comparisons, as well as to quantify the relative size of their influences upon the long-run income-SWB relationship.13

An alternative way to assess the impact of ups and downs is not to identify the disproportionate influence of losses on SWB, but instead to more broadly investigate the effects of volatility. As noted above, Wolfers (2003) approaches this question of business cycle volatility by regressing national subjective well-being on both the mean and standard deviation of the prior 8 years of the unemployment and inflation rates. He finds that the standard deviation in each case enters into the equation negatively, thus showing that business cycle volatility can undercut progress in terms of SWB. In Table A.2, we build on this by instead modeling SWB as a function of the mean and standard deviation of the previous 8 years of the GDP growth rate.14 We similarly find that economic growth volatility (proxied by the SD of the growth rate) undermines the positive effect of growth (proxied by the mean of the growth rate).

Ultimately, future research in this area will look to identify the types of macroeconomic growth policy that are most conducive to improving subjective well-being. On the one hand, a possible reading of the income-happiness paradox suggests that further growth in the developed world is a futile means to the end of improving societal well-being. On the other hand, researchers who find evidence of a positive relationship between well-being and GDP typically take from this that further economic growth is necessarily good for society. Our results suggest a more nuanced perspective: policy designed to engineer economic “booms”, but that risks even relatively short “busts” is likely to be an inefficient way to improve societal well-being in the long-run. Steady positive growth that minimizes the risk of any economic contraction could be a more plausible route to improving general well-being.

Reference points

An important avenue for further research will focus on more precisely determining the level of economic growth against which populations evaluate gains and losses. For simplicity in this paper we have assumed the natural reference point to be zero growth. Negative growth away from GDP at year t-1 is a loss, while positive growth is a gain. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that people’s reference point might well fall at a different point. For example, the reference level of income could be the highest level of GDP previously achieved. If this is the case, then episodes of positive growth back towards this reference level of income may well be related differently to SWB than episodes of positive growth that take the country beyond this reference level. In regressions reported in an online appendix, we are able to test this proposition using the Eurobarometer, which benefits from covering multiple business cycles. We find that although “recovery” growth (taking a country back to a previously achieved level of national income) and “new” economic growth (taking a country to a level of GDP above what has been experienced by the population previously) may relate differently to life satisfaction, the general asymmetry between negative and positive growth remains evident regardless of whether the positive growth is recovery or new.

Another potential alternative is that the reference point could be the previous year’s growth rate, or some other growth rate that is considered “normal”.15 A growth rate of 2% may well feel like a loss if the population had expected something closer to a 5% rise having just experienced several years of much more rapid economic expansion. Equally, a population that experienced −4% growth in year t − 1 may well consider a growth rate of −1% in year t a gain, even though it represents an absolute loss of national income. In this sense, individuals are accustomed (or “anchored”) to a certain level of growth and expect this growth to continue going forward, and then use these expectations as a reference point, judging growth that falls below the expected rate as a loss even if it is actually an absolute gain (cf. Kőszegi and Rabin, 2006). Indeed, regression models (reported in an online appendix) that introduce the economic growth rate into the equation as a deviation from the country-mean growth rate over the preceding 10 years, show that “slow” growth (i.e. negative deviations from the mean) have a larger impact than “fast” growth (i.e. positive deviations from the mean), consistent with our general account that downturns exert a larger impact than upswings.

Further limitations

Estimates across datasets as diverse as the three employed in this paper should be compared with caution. On the one hand, there are conceptual differences among the well-being questions used across the three surveys. While the Eurobarometer and BRFSS data include a life satisfaction question, the Gallup surveys use Cantril’s ladder, responses to which are anchored to the respondent’s own reference point of their ‘best possible life’. Discrepancies between these two types of evaluative questions have been documented (Bjornskov, 2010). Furthermore, self-reported measures are susceptible to mode of interview effects, with higher levels of subjective well-being generally being reported during telephone as compared to face-to-face interviews (Dolan and Kavetsos, 2016). Such mode effects have implications for the comparability of our results between surveys given that the Eurobarometer uses face-to-face interviews, the BRFSS phone interviews, and Gallup uses a mix of phone and face-to-face interviews.16 Our results aim to provide broad evidence in favor of the asymmetric experience of positive and negative growth across multiple sources of data frequently used in the economics literature, rather than highlighting the differences between these.

To simplify the analysis, we have assumed (piecewise) linearity in the income growth– well-being relationship. Further research may relax this linearity assumption in order to test for any diminishing sensitivity to both positive and negative economic growth. In addition, we have assumed that the length of recessionary periods does not matter—that is, that the damage done in the first year of a contraction is the same as in the third or fourth year of a long slump. We find, in an initial analysis reported in an online appendix, that the negative growth coefficient worsens with each subsequent year of a long recession—indicating that the losses in well-being accelerate as countries descend deeper into longer periods of economic contraction. Supplementary work will be required in order to test this dynamic further.

Finally, comparing individuals across countries as diverse as those included in the Gallup World Poll is also potentially problematic. Indeed we might well expect the relationship between national income and subjective well-being to be very different in the developed and developing worlds. Reliable macroeconomic data is also difficult to obtain for a number of developing countries included in the Gallup sample.

6 Conclusion

Using data from three large and complementary datasets on subjective well-being around the globe, our analyses reveal an asymmetry in the manner in which people experience positive and negative economic growth. We find that measures of life satisfaction as well as positive and negative affect are more than twice as sensitive to economic downturns as compared to equivalent upswings.

Standard analyses of the income-happiness relationship often find that well-being correlates with national income and thus come to the conclusion that “growth is good.” But in light of the asymmetric experience of positive and negative growth, an empirically more accurate interpretation of the income-happiness relationship might be that “recessions are bad”. The problem of labeling results by one pole of a dimension reflects deep linguistic habits rather than the structure of the data. The word “growth” conjures an idea of economic expansion, whereas many of the data points in fact represent economic contractions.17 Analogously, if we were to suppose that being very short is more likely to make one miserable than being very tall to make one happy, the relationship would still be described as connecting happiness to “height”. Piecewise regressions such as those detailed in this research can help distill important relationships and aid our interpretation of them.

Academic and policy discussions tend to overlook whether people are more sensitive to gains or losses in economic growth and focus instead on the general benefits of economic growth. As a result, most policies are evaluated by their impact on economic growth as such with less regard to any disproportionate psychological toll that recessions may exert. Our work suggests a need for nuanced growth policies and the careful use of economic growth data when considering welfare effects in terms of well-being. In sum, we suggest that policymakers and academics should not only evaluate how much the economy has grown but also how the economy has grown.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Eurobarometer

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction (1–4) | 1,094,963 | 3.073 | 0.754 | 1 | 4 |

| Economic Growth | 508 | 0.023 | 0.027 | −0.089 | 0.108 |

| Negative Growth | 78 | 0.021 | 0.020 | −0.089 | 0 |

| Positive Growth | 429 | 0.031 | 0.019 | 0 | 0.108 |

| GDP per capita (US$2005) | 508 | 31,873 | 12,750 | 10,767 | 86,127 |

| Unemployment Rate | 508 | 0.081 | 0.042 | 0.001 | 0.273 |

| Inflation Rate | 508 | 0.045 | 0.046 | −0.045 | 0.245 |

Table 3.

BRFSS

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | 2,260,476 | 3.387 | 0.628 | 1 | 4 |

| Economic growth | 1,233 | 0.001 | 0.015 | −0.097 | 0.068 |

| Negative growth | 503 | 0.013 | 0.012 | −0.097 | 0 |

| Positive growth | 730 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0 | 0.075 |

| State income per cap’ (US$2005) | 1,222 | 35,634 | 6,149 | 26,259 | 64,598 |

| Unemployment rate | 1,233 | 0.061 | 0.024 | 0.021 | 0.144 |

| Inflation rate | 1,233 | 0.006 | 0.010 | −0.028 | 0.022 |

Acknowledgments

We thank Philippe Aghion, Dan Benjamin, Chris Boyce, Sarah Brown, Andrew Clark, Angus Deaton, Paul Dolan, Richard Easterlin, Teppo Felin, Carol Graham, Ori Heffetz, David Hemous, Daniel Kahne-man, Richard Layard, George Loewenstein, Andrew Oswald, Amine Ouazad, Nick Powdthavee, Eugenio Proto, Matthew Rabin, Johannes Spinnewijn, Peter Tufano, Tim Van Zandt, and Fabrizio Zilibotti for comments and helpful suggestions. Participants at the 2014 AEA Annual Meeting, INSEAD Economics Symposium, LSE Centre for Economic Performance annual conference, and the 2015 RES Annual Conference provided helpful comments. The usual disclaimer applies. De Neve and Ward gratefully acknowledge financial support from the US National Institute on Aging (Grant R01AG040640) and the Economic & Social Research Council.

Appendix

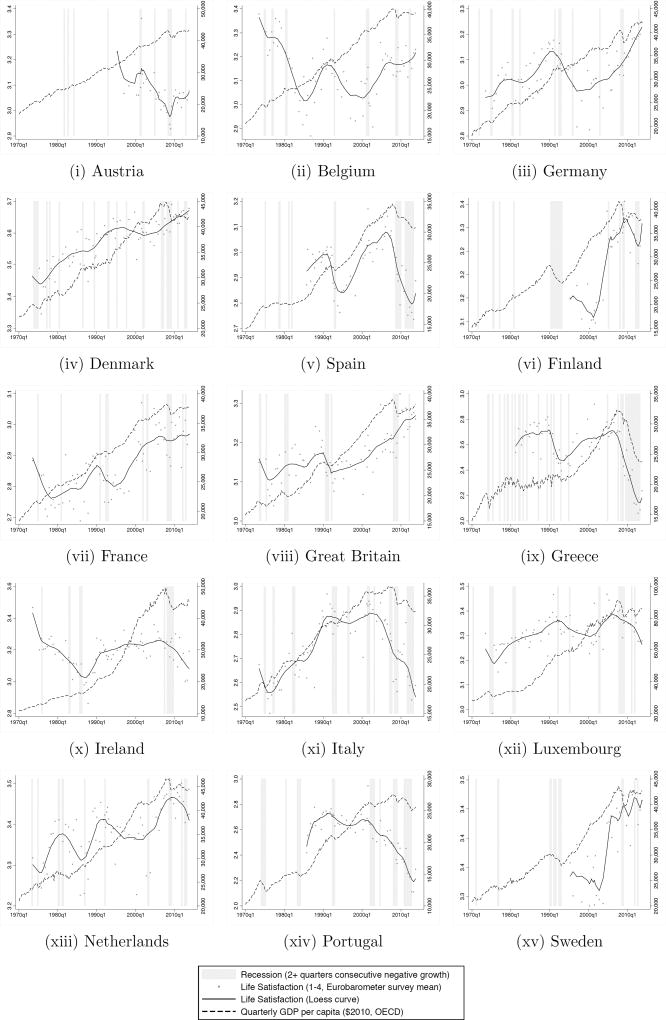

Figure A.1.

Subjective Wellbeing and GDP over time in Europe

Table A.1.

Eurobarometer: Omission of the Great Recession Years

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Satisfaction | ||||

| Years Omitted: 2007–2009 | ||||

| Economic Growth | 2.789*** | 4.271*** | ||

| (0.438) | (0.535) | |||

| Negative Growth | −8.515*** | −9.059*** | ||

| (1.511) | (1.927) | |||

| Positive Growth | 0.938** | 1.605*** | ||

| (0.365) | (0.494) | |||

| Country and Wave FEs | x | x | x | x |

| Individual Controls | x | x | x | x |

| Balanced Sample | x | x | ||

| Countries | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Country-Years | 463 | 463 | 240 | 240 |

| Individuals | 973,557 | 973,557 | 524,071 | 524,071 |

| R2 | 0.030 | 0.032 | 0.041 | 0.043 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses, adjusted for clustering at the country-year level. All outcomes variables are standardised (mean=0, SD=1). All regressions include individual-level controls: age, age-squared, education level, gender, marital status. Country fixed effects and survey wave dummies are included in all models. Negative and Positive Growth terms are splines, such that negative (positive) growth is equal to the absolute value of the growth rate when it is negative (positive) and zero otherwise.

p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

Table A.2.

Eurobarometer: Growth Rate Volatility

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life Satisfaction | |||

| Growth Rate from t-7 to t | |||

|

|

|||

| Mean | 4.331*** | 4.427*** | |

| (0.915) | (0.877) | ||

| Standard Deviation | −2.817* | −3.132** | |

| (1.702) | (1.534) | ||

|

| |||

| Country FEs, Wave FEs | x | x | x |

| Individual Controls | x | x | x |

| Countries | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Country-Years | 508 | 508 | 508 |

| Observations | 1,093,387 | 1,093,387 | 1,093,387 |

| R2 | 0.030 | 0.029 | 0.030 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses, adjusted for clustering at the country-year level. All regressions include country and wave fixed effects, as well as individual-level controls: age, age-squared, education level, gender, marital status.

p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

Table A.3.

Eurobarometer: 5 and 10 Year Long Differences in GDP per capita

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “On the whole, how satisfied are you with the life you lead?” | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 5 Year Long Differences | 10 Year Long Differences | |||||

| Δ = lnGDPjt–lnGDPjt−5 | Δ = lnGDPjt–lnGDPjt−10 | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Δ lnGDP | 0.706*** | 0.352*** | ||||

| (0.153) | (0.092) | |||||

| Δ lnGDP: Negative | −2.497*** | −2.504*** | −5.137*** | −5.182*** | ||

| (0.275) | (0.272) | (1.018) | (1.024) | |||

| Δ lnGDP: Positive | 0.247** | 0.253*** | ||||

| (0.121) | (0.086) | |||||

| Δ lnGDP: Positive * no negative growth years in-between | 0.247** | 0.262*** | ||||

| (0.120) | (0.082) | |||||

| Δ lnGDP: Positive * with negative growth years in-between | −0.112 | 0.126 | ||||

| (0.271) | (0.137) | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Country and Wave FEs | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Individual Controls | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Observations | 1,093,387 | 1,093,387 | 1,093,387 | 1,093,387 | 1,093,387 | 1,093,387 |

| R2 | 0.030 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.029 | 0.031 | 0.031 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses, adjusted for clustering at the country-year level. All regressions include country and wave fixed effects, as well as individual-level controls: age, age-squared, education level, gender, marital status. See online appendix for further details of long-difference specification and interactions.

p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

Footnotes

See also, e.g., Yellen and Akerlof (2006); Barlevy (2004) and De Santis (2007) for alternative interpretations.

See Dolan et al. (2008) for a review of the literature.

Benjamin et al. (2012) do find some systematic reversals for the link between decision utility and experience (see also Kahneman and Thaler, 2006).

We carry out our main analyses on the total, unbalanced panel of countries. In further regressions reported in an online appendix we test the robustness of our findings using a balanced panel.

Telephone surveys are used in countries where telephone coverage represents at least 80% of the population (or is the customary survey methodology). In Central and Eastern Europe, as well as in the developing world, including much of Latin America, the former Soviet Union countries, nearly all of Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, an area frame design is instead used for face-to-face interviewing. Details about the methodology for each country are available at http://www.gallup.com/se/128171/Country-Data-Set-Details-May-2010.aspx.

The Cantril Self-Anchoring Striving Scale (Cantril, 1965) asks individuals the following: “Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?” It is worth noting that respondents are also asked the same question about where they think they will stand in life about five years from now. We focus principally on the current ladder, in line with most other research using the Gallup World Poll (see e.g. Stevenson and Wolfers, 2008; Kahneman and Deaton, 2010). Following Aghion et al. (2016), we also present further analyses that test our results using the future/anticipated ladder.

A number of countries joined the EU—and the Eurobarometer—after 2004 but are not included in our sample as there is only a comparatively small amount of data available for these (mostly Eastern European) nations. Eurobarometer country-years excluded this way are, however, included in the Gallup World Poll data which span the 2005–2013 timeframe.

By splitting the data points in this way into negative and positive growth there is an implicit assumption that the natural reference point against which people judge growth performance is zero growth: negative growth is a loss, positive growth is a gain. We return to this point below in a broader discussion of reference points.

Although we present for illustrative purposes models including further key macroeconomic variables, we prefer the more parsimonious models. First, they are more comparable with the models in other studies. And second, there exist complex two-way causal relationships between inflation and unemployment on the one hand, and economic growth on the other, and simultaneous inclusion of all these variables in regression models may bias our results.

The magnitude of the coefficients in the Eurobarometer is generally larger, but it is worth reiterating that the SWB outcome measure is standardized within each dataset and that the standard deviation among this relatively homogenous group of high-income countries is likely to be relatively small compared with that of the Gallup World Poll, which encompasses a wide range of nations.

Feelings of uncertainty are also attention-seeking (Wiggins et al., 1992), and may prevent individuals from adapting to shocks (Wilson and Gilbert, 2008). Uncertainty is also arguably intensified by the disproportionate coverage of negative news about macroeconomic trends compared to respective positive trends (Soroka, 2006). Eggers and Fouirnaies (2014) leverage the arbitrariness of the cut-off of two consecutive quarters of negative growth for the official announcement of a recession to show that negative economic newspaper coverage reduces consumer spending and confidence.

We regress the subjective well-being of individuals in year t on the change in lnGDP from, say, year t-10 to year t. We then interact this positive long-difference term with a dummy variable indicating whether there has been at least one year of negative growth in the intervening 10 year period. This allows us to test whether a long positive growth period obtained via a sequence of strictly positive growth years is correlated with a rise in SWB and whether this contrasts in any way with a positive growth period obtained via ups and downs. Table A.3 reports long-differences in GDP per capita over 5 and 10 years. In an online appendix we repeat this analysis for a larger number of change lengths, as well as provide further details of this specification.

Easterlin (2010, pp. 126–6) notes, for example, the theoretical possibility of an interaction between loss aversion and adaptation, suggesting that aspirations may rise with positive growth in national income but not fall with macroeconomic losses, leading to differential adaptation to gains and losses and the long-run stagnation of aggregate happiness over multiple business cycles.

Following Wolfers (2003) we center the analysis on the previous 8 years of growth, but also report estimates for periods spanning between 5 and 12 years in an online appendix in order to ensure that we test for a wider range of possible business cycle lengths.

For example, disproportionate sensitivity to sub-zero economic growth may do little to explain the stagnation of life satisfaction in China despite year-on-year positive growth over the past two decades (Easterlin et al., 2012). Indeed a number of countries did not experience a recession during our sample period, but did nevertheless experience economic slowdowns.

Moreover, each mode has, in turn, additional implications on reported subjective well-being based on the difficulty of reaching respondents on the phone (Heffetz and Rabin, 2013) and the presence of others during face-to-face interviews (Conti and Pudney, 2011).

This semantic problem is widespread in the literature. For example, Kahneman and Deaton (2010) and De Neve and Oswald (2012) consider the relationship between personal income and subjective well-being, finding that earnings and happiness are to some extent predictive of each other. However, in neither of these studies is it examined whether the relationship is perhaps being driven principally by variation at either end of the earnings or happiness distributions.

References

- Aghion Philippe, Akcigit Ufuk, Deaton Angus, Roulet Alexandra. Creative Destruction and Subjective Well-Being. American Economic Review. 2016;12(106):3869–3897. doi: 10.1257/aer.20150338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberis Nicholas C. Thirty years of Prospect Theory in Economics: A review and assessment. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2013;27:173–196. [Google Scholar]

- Barlevy Gadi. The Cost of Business Cycles Under Endogenous Growth. American Economic Review. 2004;94(4):964–990. [Google Scholar]

- Barr Ben, Taylor-Robinson David, Scott-Samuel Alex, McKee Martin, Stuckler David. Suicides associated with the 2008–2010 recession in the UK: a time-trend analysis. British Medical Journal. 2012:245. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister Roy F, Bratslavsky Ellen, Finkenauer Catrin, Vohs Kathleen D. Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology. 2001;5(4):323. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin Daniel J, Heffetz Ori, Kimball Miles S, Rees-Jones Alex. What do you think would make you happier? What do you think you would choose? American Economic Review. 2012;102(5):2083–2110. doi: 10.1257/aer.102.5.2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin Daniel J, Heffetz Ori, Kimball Miles S, Rees-Jones Alex. Can Marginal Rates of Substitution Be Inferred from Happiness Data? Evidence from Residency Choices. American Economic Review. 2014 doi: 10.1257/aer.104.11.3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornskov Christian. How comparable are the Gallup World Poll life satisfaction data. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2010;11:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom Nicholas. The impact of uncertainty shocks. Econometrica. 2009;77(3):623–685. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom Nicholas. Fluctuations in Uncertainty. The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2014;28(2):153–175. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman David, Minehart Deborah, Rabin Matthew. Loss aversion in a consumption-savings model. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 1999;38:155–178. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce Christopher J, Wood Alex M, Banks James, Clark Andrew E, Brown Gordon DA. Money, Well-Being, and Loss Aversion: Does an Income Loss Have a Greater Effect on Well-Being Than an Equivalent Income Gain? Psychological Science. 2013;24(12):2557–2562. doi: 10.1177/0956797613496436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantril Hadley. The pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier Caroline J, Neve Jan-Emmanuel De, Li Xinyi, Roiser Jonathan P, Sharot Tali. Models of affective decision-making: how do feelings predict choice? Psychological Science. 2016;6:763–775. doi: 10.1177/0956797616634654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Andrew E, Oswald Andrew J. Unhappiness and Unemployment. Economic Journal. 1994;104(424):648–659. [Google Scholar]

- Clark Andrew E, Oswald Andrew J, Frijters Paul, Shields Michael A. Relative Income, Happiness, and Utility: An Explanation for the Easterlin Paradox and Other Puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature. 2008;46(1):95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Clark Andrew E, Oswald Andrew J, Fleche Sarah, Senik Claudia. Economic Growth Evens Out Happiness: Evidence from Six Surveys. Review of Income and Wealth. 2016 doi: 10.1111/roiw.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti Gabriella, Pudney Stephen. Survey design and the analysis of satisfaction. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2011;93:1087–1093. [Google Scholar]

- De Neve Jan-Emmanuel, Oswald Andrew J. Estimating the influence of life satisfaction and positive affect on later income using sibling fixed effects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(49):19953–19958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211437109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton Angus. Income, Health, and Well-being Around the World: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2008;22(2):53–72. doi: 10.1257/jep.22.2.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton Angus. The financial crisis and the well-being of Americans - 2011 OEP Hicks Lecture. Oxford Economic Papers. 2012;64(1):1–26. doi: 10.1093/oep/gpr051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan Paul, Kavetsos Georgios. Happy talk: Mode of administration effects on subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2016;17:1273–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan Paul, Kavetsos Georgios, Peasgood Tessa, White Matthew. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2008;29:94–122. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin Richard A. Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some Empirical Evidence. In: David PA, Reder MW, editors. Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramovitz. New York: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 89–125. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin Richard A. Happiness, growth, and the life cycle. Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin Richard A, Angelescu-McVey Laura, Switek Malgorzata, Sawangfa Onnicha, Zweig Jacqueline S. The Happiness-Income Paradox Revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(52):22463–68. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015962107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin Richard A, Morgan Robson, Switek Malgorzata, Wang Fei. China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(25):9775–9780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205672109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers Andrew C, Fouirnaies Alexander B. The Economic Impact of Economic News. Mimeo: University of Oxford; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fleurbaey Marc, Blanchet Didier. Beyond GDP: Measuring Welfare and Assessing Sustainability. Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Foellmi Reto, Rosenblatt-Wisch Rina, Schenk-Hoppe Klaus Reiner. Consumption Paths Under Prospect Utility in an Optimal Growth Model. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. 2011;35(3):273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Graham Carol. Happiness around the world: The paradox of happy peasants miserable millionaires. Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Graham Carol, Chattopadhyay Soumya, Picon Mario. Does the Dow Get You Down? Happiness and the US Economic Crisis. The Brookings Institution. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Heffetz Ori, Rabin Matthew. Conclusions regarding cross-group differences in happiness depend on difficulty of reaching respondents. American Economic Review. 2013;103:3001–3021. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.7.3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell John, Layard Richard, Sachs Jeffrey. World Happiness Report, UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman Daniel. Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology, Russell Sage. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman Daniel, Tversky Amos. Prospect theory: An analysis of decisions under risk. Econo-metrica. 1979;47:263–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman Daniel, Deaton Angus. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2010;107:16489–16493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011492107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman Daniel, Thaler Richard H. Anomalies: Utility Maximization and Experienced Utility. The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20(1):221–234. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman Daniel, Wakker Peter, Sarin Rakesh. Back to Bentham? Explorations of Experienced Utility. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1997;112(2):375–406. [Google Scholar]

- Kassenboehmer Sonja C, Haisken-DeNew John P. You’re Fired! The Causal Negative Effect of Entry Unemployment on Life Satisfaction. Economic Journal. 2009;119(536):448–462. [Google Scholar]

- Kermer Deborah A, Driver-Linn Erin, Wilson Timothy D, Gilbert Daniel T. Loss aversion is an affective forecasting error. Psychological Science. 2006;17(8):649–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kőszegi Botond, Rabin Matthew. A model of reference-dependent preferences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2006:1133–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger Alan B, Stone Arthur A. Progress in Measuring Subjective Well-Being: moving toward national indicators and policy evaluations. Science. 2014:42–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1256392. 346(6205) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layard Richard. Happiness: Lessons from a new science, Penguin. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Lucas Robert E. Models of Business Cycles. New York: Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas Robert E. Macroeconomic Priorities. American Economic Review. 2003;93(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Luechinger Simon, Meier Stephan, Stutzer Alois. Why Does Unemployment Hurt the Employed? Evidence from the Life Satisfaction Gap between the Public and the Private Sector. Journal of Human Resources. 2010;45(4):998–1045. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott Rose, Fowler James H, Smirnov Oleg. On the evolutionary origin of prospect theory preferences. The Journal of Politics. 2008;70(02):335–350. [Google Scholar]

- Montagnoli Alberto, Moro Mirko. Everybody hurts: banking crises and individual wellbeing. Sheffield Economic Research Paper Series no. 2014010. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Otrok Christopher. On measuring the welfare cost of business cycles. Journal of Monetary Economics. 2001;47(1):61–92. [Google Scholar]