Abstract

Health care professionals working collaboratively on interprofessional teams are essential to optimize patient-centered care. Collaboration and teamwork can be best achieved if interprofessional education (IPE) starts early for health professions students. This commentary describes the formation, implementation, impact, and lessons learned from students’ curricular and co-curricular activities and faculty collaboration over a five-year trajectory of the Eastern Shore Collaborative for Interprofessional Education (ESCIPE). This collaborative is an inter-institutional, interprofessional team and includes 18 faculty members from nine health disciplines with administrative support to prepare practice-ready graduates through effective IPE curricular and co-curricular activities. This collaborative also serves as a resource for interprofessional education, research and scholarship initiatives for faculty members. Activities include educational programs such as an emergency preparedness point-of-dispensing (POD) drill, patient management laboratory simulation, geriatric assessment interdisciplinary team workshop, medical mission as public/global health rotation and service-learning program, rural health fair, and annual university health festival for community outreach. The ESCIPE has also facilitated interprofessional faculty assessment and development, research and scholarship opportunities.

Keywords: interprofessional education, interdisciplinary, health professions education

INTRODUCTION

According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2003 report, Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality, interdisciplinary teamwork is one of five core competencies for health care professionals.1 The IOM report states that health care professionals should communicate effectively, understand each other’s roles, and be educated to deliver patient-centered care as members of an interdisciplinary team to provide safe and high-quality care for patients. The World Health Organization (WHO) illustrates that interprofessional education (IPE) occurs when at least two professional students learn “about, from, and with” each other.2 Furthermore, it is well-recognized that health care professionals must work collaboratively in functional teams to meet the needs of patients and work within a dynamic health care delivery system. Collaboration and teamwork can best be achieved if IPE starts early, with students from different professions engaging in interactive learning.1,2 While health care professional education has evolved to include aspects of IPE in their schools and curricula, accrediting bodies have recommended, and in some cases, required IPE as a specific standard or competency for health care professional students’ education.3-14 The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) published an expert panel report with core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice. Furthermore, the IPEC has provided a training institute for health care professional educators and administrators to engage in discussions and facilitate the development and implementation of IPE in a team-based approach across health care professional education over the years. 15

Formation of the Eastern Shore Interprofessional Collaborative

In 2012, an inter-institutional and interprofessional team was created and comprised of five faculty members from six disciplines: nursing and respiratory therapy at Salisbury University (SU), and pharmacy, physical therapy, physician’s assistant, and rehabilitation science at University of Maryland Eastern Shore (UMES). The SU-UMES team of four faculty members attended an IPEC conference in 2012, which served as a catalyst for the creation of the Eastern Shore Collaborative for Interprofessional Education (ESCIPE) to advance health care education for future practicing professionals on the eastern shore of Maryland. Since the 2012 IPEC conference, the ESCIPE team has met monthly, alternating between campuses, to achieve its mission, goals, and objectives (Appendix 1). These meetings have culminated in the development, implementation, and evaluation of multiple educational programs, training experiences, and collaborations for students and faculty. A team of four faculty members attended a second IPEC conference in 2014 as a re-affirmation for inter-institutional and interprofessional collaboration. Currently, the ESCIPE team has 18 faculty members representing nine disciplines at two institutions.

Over the past five years, the ESCIPE team has received multiple levels of ongoing support, including leadership, infrastructure, and funding from SU and UMES. The mission, vision, and strategic plans of both institutions include IPE as a priority. Leadership support at the university administration level, which provided the funding for ESCIPE team members to attend the two IPEC conferences, has also supported funding for local faculty development programs and networking events. At SU, the departments that are actively involved in IPE efforts are nursing, respiratory therapy, medical laboratory science, social work, exercise science, and athletic training. At UMES, these are the programs of dietetics, pharmacy, physical therapy, and rehabilitation science. Overall, 18 ESCIPE faculty members from nine disciplines at both institutions have become the champions for IPE activities and efforts in their respective programs.

Interprofessional Faculty Assessment and Development

Improved health outcomes for patients have been demonstrated through interprofessional collaborations, yet there are few studies related to the importance and support of faculty development in interprofessional education.15 While pre-professional health care students need opportunities to work collaboratively with other team members, this can only be achieved through high-quality opportunities from well-prepared instructors. Faculty members need appropriate support and resources in developing courses, workshops, simulations, recruitment of experienced speakers, and assistance in disseminating information.16-18 In the fall of 2013, ESCIPE developed the Interprofessional Perception, Knowledge, and Attitudes Scale (IPKAS) to conduct an assessment relative to the IPEC core competency awareness and perception of faculty from multiple professions at both institutions. The results of the survey revealed that faculty members lacked confidence in their IPE knowledge, were deficient in IPE pedagogical approaches, and uncertain of how to best manage interprofessional conflicts.19 This data served as a catalyst to guide faculty development programs at both institutions.

ESCIPE aimed to provide faculty members with programs to further develop and enhance their ability to teach interprofessional skills. In August 2014, a faculty development workshop focusing on the core elements of interprofessional education, managing interprofessional conflicts, and teaching interprofessional development skills was offered. More than 40 faculty members representing both institutions and eight professional programs attended. The program was well-received and had favorable evaluations. In addition to providing an opportunity for faculty members to develop skills in interprofessional education, the workshop was an opportunity for them to network and build inter-institutional, interprofessional partnerships. In May 2016, members of ESCIPE sponsored an Interprofessional meet and greet where various health-related community organizations came to Salisbury University and discussed their organizations’ services. Faculty members from both universities attended with eight programs represented. The meet and greet consisted of an introduction to ESCIPE-related interprofessional programs and opportunities followed by presentations from each community organization. Those represented included a community-based organization that provides services to individuals with mental illness and addictions, an area health education center, a local hospice facility, an acute-care facility, and a local agency on aging. An open forum that facilitated networking and further collaboration followed the agency presentations.

Interprofessional Activities Across the Curricular Spectrum

The two universities have developed multiple interprofessional activities that reflect ESCIPE’s overall mission and goals (Appendix 1). Faculty members have approached these initiatives positively to foster effective interprofessional communication and team-building. This positive approach has traditionally been a strong catalyst for health care faculty members to participate in interprofessional curricular activities and provide enriched interprofessional learning opportunities for students.20 One of the first initiatives of ESCIPE was the development of a formal guest lecturer network. In this exchange, faculty members are invited to present an area of expertise in health programs at both universities. Topics include research design, disease pathologies, and discipline-specific scope of practice. Additionally, faculty members at both universities have designed, developed, and implemented a variety of interprofessional curricular activities, including didactic, clinical, and experiential components over five years. Selected examples are discussed below.

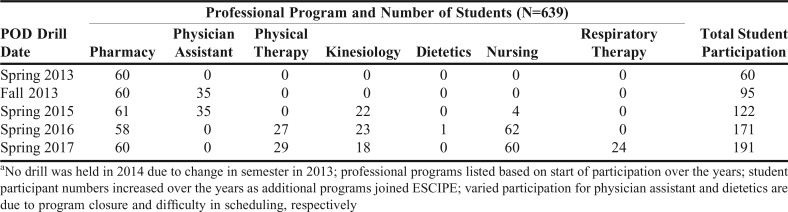

Emergency Preparedness Point-of-Dispensing (POD) Drill. In 2013, the UMES School of Pharmacy initiated a plan to conduct a POD drill in conjunction with the Somerset County Health Department, the county in which UMES is located, in Maryland to prepare and train student pharmacists to be able to assist with the operation of a POD as outlined in the university’s emergency preparedness and response plan and aligned with the Maryland Department of Health, Office of Preparedness and Response. While the first drill was conducted with student pharmacists only, it became evident that this training would be applicable to the other health professions students on campus to increase the number of trained volunteers and provide an opportunity for students to work together interprofessionally. Each year thereafter, more UMES health professions students were added, and starting in 2016, nursing students from SU were included. In 2017, respiratory therapy students from SU attended, which increased the total participation in this annual activity to 191 students (Table 1). This activity is part of a required public health course for first professional year pharmacy students. For the POD drill exercise, students are paired into two-person interprofessional teams (eg, one student pharmacist and one student nurse) and then work together in this team for the entire 3-hour exercise. In the follow-up survey conducted after the most recent drill, 67% (n=191) of the students agreed or strongly agreed that “working with a student from a different profession improved my ability to engage in patient-centered problem-solving.”

Table 1.

Point of Dispensing (POD) Drill/Exercise Student Participation 2013-2017a

Patient Management Laboratory Simulation. An interprofessional patient laboratory simulation provides health care professional students the opportunity to work collaboratively on acute-care focused patient cases specifically prepared for the sharing of discipline-specific interventions. This annual event includes students from nursing, pharmacy, respiratory care, and physical therapy. Cases related to management of patient diagnoses such as Parkinson’s disease, cystic fibrosis, and total hip arthroplasty. Each discipline contributes to the overall patient profile with mobility maneuvers, breathing exercises, management of supplemental oxygen, medication review, and wound assessment.21

An intensive care unit case study was developed to give students practice assessing and mobilizing, as a team, the complex medical patient with multiple fractures, lines and tubes, and splint devices. In addition, students were required to collectively respond to medical emergencies involving postural hypotension and autonomic dysreflexia. Students gained insight into the roles of other health professionals and worked toward providing better patient team-based interprofessional care. Follow-up surveys indicated that 100% (n=83) of participants of all disciplines gained insight into the roles of other health professionals.21 Similarly, all students expressed that shared learning with other health professionals increased their ability to understand clinical problems. This is a required curricular activity for students.

Geriatric Assessment Interdisciplinary Team (GAIT) and Geriatric Toolbox Workshop. In conjunction with the local area health education center (AHEC), the 2016 workshop was attended by 146 health care professional students from a variety of disciplines (45 nursing, 58 pharmacy, 33 physical therapy, and 10 social work students) as a part of a course. The one- or two-day GAIT workshop focuses on geriatric topics for rural communities. Settings have included hospitals, physical therapy clinics, and residential care facilities. Interprofessional experiences held on site at geriatric facilities have historically promoted effective learning opportunities.22 Each workshop has a thematic underpinning, such as fall prevention, hospice care, discharge planning, and cognitive challenges in older adults, which requires students to synthesize a variety of resources. An aging simulation experience, patient interviews, and interprofessional treatment-planning are embedded in the GAIT curriculum. Students enhance their communication skills by interacting with other health professionals on an interdisciplinary team. A second event sponsored by the local AHEC is the Geriatric Toolbox Workshop. Using a geriatric case study as a springboard for interdisciplinary discussion and deliberation, health care students use various instruments and strategies to assess behavior, mood, medications, and mobility in older adult clients. They subsequently apply these outcomes measures to the initial case study and formulate appropriate interventions and referrals for community resources.

Medical Missions as Global Health Service Experience. Global health has become an integral component and opportunity for health care professional students’ education. An academic-community partnership was formed with Health and Education for Haiti,23 La Merced, and International Community Initiatives for ensuring sustainability of medical missions as a global health experience, including clinical rotations and service-learning opportunities. Global competency activities were developed. Pre-mission preparation included Haitian Creole language training, country profile and tropical diseases presentations, physical assessments training, and medications and supplies inventory, packaging, and labeling. Post-mission works included reflection papers, in-service presentations, and fundraising. There were 34 students -- 26 pharmacy, 5 physical therapy, and 3 physician assistant -- along with 15 health care professionals who conducted four missions over four years. Nearly 4,000 patients were served, and 9,000 prescriptions dispensed. Each mission averaged seven days abroad with a faculty member/preceptor to student ratio of 1:2. Lessons learned from these experiences included the need for standardized documentation sheets, pre-printed medication labels, and interpreters at every workstation. A stepwise and systematic process for the development and implementation of future experiences was documented. Providing health care services in an interprofessional international environment enabled participants to foster new relationships with diverse populations and gain real-world experiences while benefiting underserved communities.

Rural Health Screening Service. Nursing, pharmacy, and physical therapy students traveled to a remote island within the Chesapeake Bay, accessible only by boat, where residents have limited access to traditional health care services. This initiative enabled the collaboration with the local area health education center. In the local church, students performed wellness screens, including falls and balance batteries, medication reconciliation, and nutrition assessments. As a co-curricular activity, students worked with local residents in interprofessional teams, completed medical histories and offered support with assistive devices, exercises, medication, and dietary information. There were 10 interprofessional teams of students in their next to or final professional year, and each discipline observed those screening tools (eg, balance, medication reconciliation, and nutrition) performed by the other students. Aggregate team recommendations were given. Where appropriate, participants were referred for follow-up or primary care. Rural health screens have traditionally afforded opportunities for students to perform community health histories and develop skills to work with underserved populations.24

Annual University Health Festival for Community Outreach and Service. A major benefit of collaboration between two universities includes infusing interprofessional elements into existing events. The UMES Annual Health and Wellness Festival is held each spring to meld both rural community and university resources, along with more than 60 invited healthcare agencies and university programs. The festival offers students co-curricular opportunities for “hands-on” experience with health promotion initiatives, while offering resources to diverse underrepresented local residents. Nursing students provide education with the local health department as a part of their clinical rotation. Pharmacy and physical therapy students provide collaborative efforts for education and interaction with the public. Students were paired from each profession to disseminate health promotion topics, with each profession tailoring the interaction and education to their own scope of practice. The goals of incorporating IPE at the festival are multifaceted. Students gain a heightened understanding of their role on the health care team, while both developing and promoting patient-centered care. The health fair initiatives also reinforce didactic curricular content with topics including vital signs and assistive device adjustment. Sadowski and colleagues demonstrated that peer teaching is an effective mode of instruction between pharmacy and physical therapy to enhance ambulatory device psychomotor skill acquisition.25

Dissemination and Scholarship for Faculty

The ESCIPE has facilitated interprofessional research and scholarship opportunities for faculty. Members of the collaborative have presented the works of the ESCIPE, including innovative interprofessional development and teaching strategies, through multiple presentations at local, regional, national, and international conferences. More than 10 peer-reviewed oral and poster presentations have been completed. Upon publication of this article, there are four peer-reviewed manuscripts from the works of the ESCIPE published in four different disciplines journals.19,21,26 As an example, one manuscript focused on an undergraduate interprofessional critical care course, the first of its kind within the University System of Maryland (USM) that targeted nursing and respiratory therapy students to learn collaboratively in a safe simulated learning environment. All ESCIPE-related presentations and manuscripts reported the results of various activities developed and implemented by members of ESCIPE. Several members also have ongoing interprofessional and active programs of research and funding. In addition to the knowledge and experience being provided to student participants in this effort, the importance of this work’s contributions toward faculty requirements of tenure and promotion is immense.

Lessons Learned, Next Steps, and Conclusion

The creation and maintenance of the ESCIPE has required support from many stakeholders. Although the two universities are only 12 miles apart, each has its own culture and milieu. Faculty members have had to collaborate interprofessionally to ensure the success and sustainability of the ESCIPE. The collaboration has represented, on a small scale, an ability to overcome the barriers that thwart interprofessional practice and the rewards that IPE can provide. The collaborative has served as an environment that simulates some of the challenges in IPE including role clarification, discipline-specific expectations, difference in education and practice language and entry-level practice discrepancies. Logistics such as academic calendar differences, lack of common meeting space, limited parking on either campus, and changes in the membership of the committee are among the challenges.

The existence of ongoing leadership support for this interprofessional collaborative has been critical. Deans have provided both encouragement and financial assistance, as well as, secretarial support. Both university presidents are supportive of this effort for the two universities to work together. The idea of health care professionals from two universities working with one another has benefits for students and faculty members, although the latter are required to collaborate by their accrediting bodies and academic roles. There are also altruistic benefits for Eastern Shore patients and residents as health care consumers.

Overall, IPE activities over the past five years have supported the mission and overarching goals of ESCIPE to prepare practice-ready graduates through effective IPE to enter the increasingly complex health care workforce, and serve as a resource for interprofessional expertise facilitating education, research and scholarship opportunities for supporting optimal patient-centered health care and outcomes. Several objectives, including curricular and co-curricular activities, as well as faculty development and scholarship have been achieved or in-progress when at least one or two activities have been implemented.

As the ESCIPE has reached its five-year milestone, the development and implementation of IPE activities and initiatives should also have formal evaluation. This will better assess and further develop the ESCIPE strategic plan, including setting future directions and priorities for the next five years. For example, ESCIPE faculty representatives have already provided feedback to secure targeted funding and grants for additional IPE activities, build and maintain a neutral ESCIPE website, survey students of all health care professions on both campuses for their IPE awareness and perceptions upon enrollment and graduation. These efforts and opportunities can be expanded with additional funding and grants for further impact and sustainability, especially in working together with regional health care partners to enhance patient care and outcomes. The expansion of academic workforce partnerships, including local and state health agencies and medical centers, is also important to meet current and future workforce needs in the region and beyond, ultimately to improve patient-centered care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge ESCIPE team members and staff support from both universities:

Patrick Dougherty, PharmD, Cathy Ferraro, M.S., RDN, LDN, Lisa Joyner, MEd, RRT, RRT-NPS, Dennis Killian, PharmD, PhD, Meredith Madden, EdD, ATC, Jennifer Marvin, MSW, LGSW, Adriana Rangel, MPH, RRT, Donna Ritenour, EdD, ATC, Nancy Rodriguez-Weller, RPh, FASCP, Annette Rogers, BS, Leslie Santos, PhD, CRC, William B. Talley, RhD, CRC, Kimberly van Vulpen, PhD, MSW.

We appreciate administrative support for ESCIPE creation and sustainability from both universities: Dr. Juliette B. Bell, president of University of Maryland Eastern Shore (UMES); Dr. Janet Dudley-Eshbach, president of Salisbury University (SU); Dr. Rondall E. Allen, dean of UMES School of Pharmacy & Health Professions; Dr. Michael Scott, dean of SU Henson School of Science & Technology; Dr. Nicholas R. Blanchard, founding dean of UMES School of Pharmacy & Health Professions; and Dr. Karen Olmstead, former dean of SU Henson School of Science & Technology.

We acknowledge our partners and their support for Point-of-Dispensing (POD) drill: Barbara Logan, RN, CHEP, Emergency Preparedness coordinator, Somerset County Health Department; and Don Taylor, RPh, former president/chair of the Maryland Board of Pharmacy Emergency Preparedness Task Force (EPTF). We also acknowledge our partner and its funding for Geriatrics Assessment Interdisciplinary Team (GAIT): Lisa Widmaier, MEd, GAIT coordinator/CHW lead trainer, Eastern Shore Area Health Education Center (AHEC); and Reba Cornman, MSW, director, The Geriatrics and Gerontology Education and Research Program (GGEAR) at University of Maryland Baltimore.

Appendix 1. The Eastern Shore Collaborative for Interprofessional Education (ESCIPE)

Mission, Goals, and Objectives – adopted 10/9/13, revised 6/14 and 9/14

Mission: To facilitate interprofessional educational opportunities and academic-practice partnerships among health care faculty, professionals, and students at Salisbury University and University of Maryland Eastern Shore to optimize health care outcomes.

Goals and Objectives

Working together with regional health care partners to:

-

1. Prepare practice-ready graduates through effective interprofessional education to enter the increasingly complex health care workforce.

1.1 Design and implement interprofessional didactic courses for SU and UMES students

1.2 Provide interprofessional experiential opportunities for SU and UMES students

1.3 Implement interprofessional seminars for SU and UMES students

-

2. Serve as a resource for interprofessional expertise facilitating educational, research and scholarship opportunities for supporting optimal patient-centered health care and outcomes.

-

2.1 Develop and provide needs based interprofessional workshops for faculty

- Conduct a faculty needs assessment survey regarding interprofessional education (IPE) awareness and perception

- Implement faculty development workshop

2.2 Facilitate and disseminate interprofessional research opportunities and scholarly development for faculty and students

2.3 Secure targeted funding to support collaborative activities

2.4 Develop guest-lecture resources, eg, speakers bureau, for both SU and UMES campuses

2.5 Develop academic-workforce partnerships to meet current and future workforce needs

-

REFERENCES

- 1. Greiner AC, Knebel E, eds. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003. [PubMed]

- 2. Hopkins D, ed. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- 3. Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. ACEND accreditation standard for nutrition and dietetics internship programs. June 1, 2017.

- 4. National Accrediting Agency for Clinical Laboratory Sciences (NAACLS). Standards for Accredited and Approved Programs. June 2016.

- 5. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice. Washington, DC; 2008.

- 6. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The Essentials of Master's Education in Nursing. Washington, DC; 2011.

- 7. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice. Washington, DC; 2006.

- 8. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Center for Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 Educational Outcomes. www.aacp.org. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- 9. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Standards 2016. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- 10. Standards and required elements for accreditation of physical therapist education programs. http://www.capteonline.org/uploadedFiles/CAPTEorg/About_CAPTE/Resources/Accreditation_Handbook/CAPTE_PTStandardsEvidence.pdf.

- 11. Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant, Inc. Accreditation Manual. Accreditation Standards for Physician Assistant Education. 4th ed. Johns Creek, GA: ARC-PA; 2016.

- 12. Accreditation Manual for Undergraduate Level Rehabilitation Education Programs. http://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/accreditation-manuals/

- 13. Commission on the Accreditation of Respiratory Care. Accreditation standards for respiratory therapy programs. http://www.coarc.com/Accreditation/Entry-into-Practice.aspx.

- 14. Council on Social Work Education. Commission on Accreditation Commission on Educational Policy. The 2015 educational policy and accreditation for baccalaureate and master’s social work programs. http://www.cswe.org/getattachment/Accreditation/Accreditation-Process/2015-EPAS/2015EPAS_Web_FINAL.pdf.aspx.

- 15. Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice. Report of an expert panel. Washington, DC; 2011.

- 16.Egan-Lee E, Baker L, Tobin S, Hollenberg E, Dematteo D, Reeves S. Neophyte facilitator experiences of interprofessional education: implications for faculty development. 2011;25(5):333–338. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2011.562331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simmons B, Oandasan I, Soklaradis S, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of an interprofessional education faculty development course: the transfer of interprofessional learning to the academic and clinical practice setting. 2011;25(2):156–157. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2010.515044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinert Y. Learning together to teach together: interprofessional education and faculty development. 2005;19(Suppl 1):60–75. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinderer KA, Klima D, Truong HA, et al Faculty perceptions, knowledge, and attitudes toward interprofessional education and practice. J Allied Health. 2016;45(1):e1–e4. [PubMed]

- 20.Olenick M, Allen LR. Faculty intent to engage in interprofessional education. 2013;6:149–161. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S38499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klima DW, Hinderer KA, Freda K, McDowell Winter DE, Joyner R. Interprofessional collaboration between two rural institutions: a simulated teaching laboratory paradigm. 2014;23:45–48. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoti K, Forman D, Hughes J. Evaluating an interprofessional disease state and medication management review model. 2014;28(2):168–170. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.852523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dang YH, Nice FJ, Truong HA. Academic-community partnership for medical missions: lessons learned and practical guidance for global health service-learning experiences. 2017;28(1):8–13. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2017.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mpofu R, Daniels PS, Adonis TA, Karuguti WM.Impact of an interprofessional education program on developing skilled graduates well-equipped to practise in rural and underserved areasRural Remote Health20141432671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadowski CA, Li JC, Pasay D, Jones CA. Interprofessional peer teaching of pharmacy and physical therapy students. 2015;79(10):Article 155. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7910155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinderer KA, Joyner RL., Jr. An interprofessional approach to undergraduate critical care education. J Nurs Educ. 2014;53(3):S46–S50. [DOI] [PubMed]