Abstract

Purpose

The pharmacokinetic properties of mecillinam (MEC) for urinary tract infections are excellent, and the resistance rate in Enterobacteriaceae is low compared to other recommended antibiotics. The oral prodrug pivmecillinam (P-MEC) has been used successfully as first choice for cystitis in the Nordic countries for many years. Norwegian and Danish guidelines also recommend P-MEC for acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis (AUP) and intravenous (IV) MEC for suspected urosepsis (only in Denmark). Here, we wish to present an updated investigation on the clinical data behind these recommendations together with sparse but more current clinical data.

Methods

Prospective clinical trials evaluating MEC as monotherapy or in polytherapy with one other beta-lactam (mostly ampicillin [AMP]) for pyelonephritis or bacteremia were reviewed. Outcomes of primary interest were clinical and bacteriological success and relapse, respectively. Search databases used were PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Embase.

Results

Twelve clinical studies (1979–2015) were included in this integrated literature review. Clinical success was seen in 38/51 (75%) patients treated with MEC as monotherapy and in 152/164 (93%) patients treated with MEC and one other beta-lactam. Bacteriological success was seen in 35/47 (74%) and 117/167 (70%) patients treated with MEC alone and with one other beta-lactam, respectively. In complicated infections, bacteriological success was much lower. Clinical relapse rate was not well described. Several uropathogenic bacteremia cases were treated successfully with MEC alone (ie, 10/15 [67%] and 13/15 [87%] for clinical and bacteriological success, respectively) or with one other beta-lactam (ie, 57/65 [88%] and 53/63 [84%] for clinical and bacteriological success, respectively). However, data on bacteremia are very sparse. Adverse reactions were few and mild (73/406 [18%]) and primarily seen when AMP was co-administered (69/73 [95%]). No serious adverse reactions were reported.

Conclusion

IV MEC or oral P-MEC for 14 days may be suitable for the treatment of AUP and pediatric pyelonephritis. Randomized controlled trials using a single standardized dose of P-MEC compared to other current recommendations are warranted. Similarly, more evidence is required before MEC should be recommended for bacteremia or sepsis due to Enterobacteriaceae.

Keywords: pyelonephritis, mecillinam, review, pivmecillinam, amdinocillin

Introduction

Mecillinam (MEC) (known as amdinocillin in the USA) is an antimicrobial drug from the amidinopenicillin group that was first introduced in 1972. MEC is selective and highly effective against Gram-negative bacteria, especially Escherichia coli.1,2 The oral prodrug pivmecillinam (P-MEC) has high bioavailability (~70%), and 45% of the dose is secreted in the urine as MEC within 6 hours. Side effects are few and most commonly include mild gastrointestinal symptoms.2,3 Community resistance rates are generally low (including in Scandinavia [5%–6%]4–6 where MEC has been used for several decades), with a low rate of collateral damage and a low risk of clonal spread of resistance.7–12

The international guideline for acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis (AUP) recommends that local resistance toward an empirical antibiotic should be <10%,13 and as the rates of resistance to recommended antibiotics continue to rise,8,11 the current recommendations are increasingly limited.13 The resistance to ciprofloxacin is of particular concern because ciprofloxacin is generally the recommended first-line therapy for outpatient care of pyelonephritis.13 The present pipeline of novel oral antimicrobials is very limited. Therefore, it is crucial to re-vitalize old antimicrobials for potential effectiveness against pyelonephritis. We believe that MEC has several interesting properties for this indication, including high efficacy for the treatment of lower urinary tract infections (UTI),3,14–16 high renal tissue concentration compared to serum,17 low rates and spread of resistance even in countries with high consumption,7–11 and few side effects and synergism with other antibiotics.2 MEC also exhibits good in vitro activity against extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) and carbapenemase producing Enterobacteriaceae;18–22 however, clinical utility is still not well established in the literature.23,24

Nevertheless, the potential use of MEC for the treatment of pyelonephritis and urosepsis is not internationally acknowledged. The oral prodrug is however recommended empirically against AUP in Denmark and Norway (400 mg three times daily [tid], for 7–14 days),25–27 or intravenously (IV) as MEC (1 g tid) for the treatment of urosepsis,28 but the evidence behind these recommendations is not specified in the guidelines.

Aim

With this study, we wanted to present an updated investigation of the clinical trials underlying these recommendations. We believe that this could enlighten the medical community outside Scandinavia of this old alternative antimicrobial drug for especially acute pyelonephritis, where the causative bacteria increasingly are resistant to the currently recommended therapies.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

We included prospective clinical trials in children (excluding neonates) and adults of MEC/P-MEC as monotherapy or in combination with another antibiotic for acute pyelonephritis and/or urosepsis/bacteremia. Bacteriological and/or clinical effects had to have been evaluated. We did not limit our inclusion to randomized controlled trials since there were few studies on the subject.

Search strategy

We conducted a widespread search for relevant studies in English regardless of age of the studies. We performed an unfiltered PubMed search combining the following terms: (“pyelonephritis” OR “upper urinary tract infection” OR “urinary tract infection” OR “UTI” OR “Sepsis” OR “Septic” OR “SIRS” OR “bacteraemia” OR “fever” OR “Febrile”) AND (“mecillinam” OR “pivmecillinam” OR “amdinocillin” OR “amidinopenicillin”) (N=317). A MeSH database search was done with the following mesh words in combination: (“Fever” OR “Sepsis” OR “Pyelonephritis” OR “Urinary Tract Infections” OR “Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome” OR “Bacteraemia”) AND (“Amdinocillin” OR “Amdinocillin Pivoxil”) (N=169). After removing duplications, the searches yielded 317 articles. The last search was conducted on February 17, 2017. Similar searches in the Cochrane Library (N=61) and Embase (N=218) were performed. The reference lists of the included studies and relevant reviews were additionally scanned for relevant clinical trials not found in the PubMed and MeSH database search.

Trial selection and data extraction

The primary reviewer selected studies according to inclusion criteria and extracted data. Outcomes of interest were clinical success and relapse, as well as bacteriological success and relapses. Senior reviewers controlled justifications for excluded studies and data extractions. All reviewers evaluated the scientific context and relevance of the selected studies and data extraction. We extracted data on characteristics such as trial design, patients (ie, sex, age, and comorbidities), type of infections (ie, pyelonephritis, bacteremia, acute, and complicated), pathogens and sensibility, and intervention (ie, antibiotics, doses, intervals, and durations). The data were analyzed by per-protocol, since majority of the studies used this methodology.

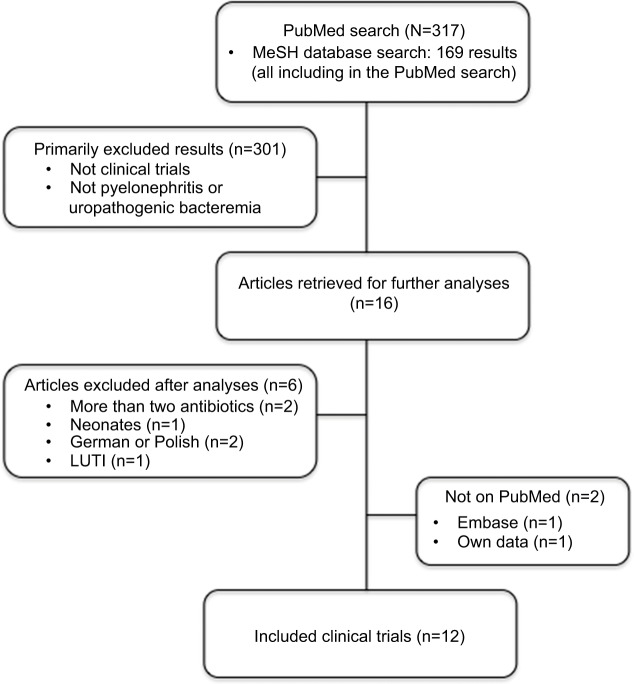

Results

Results from the literature search are summarized in Figure 1. We identified 317 articles in the PubMed and MeSH database search, which yielded the included clinical trials.29–38 The following two clinical trials were further included: one from Embase and reference lists39 and one recent quality control study on the Danish guidelines by our own research group.40 We identified the following 12 prospective clinical studies29–40 that met our criteria: two studies on MEC’s effect on uropathogenic bacteremia,30,32 one study on MEC’s effect on pediatric pyelonephritis,33 four studies on MEC’s effect on pyelonephritis with or without bacteremia,36,38–40 and five studies on concomitant MEC and ampicillin (AMP) therapy on pyelonephritis with or without bacteremia.31,34,35,37 Three studies were prospective noncomparative,32,33,36,40 and eight studies were prospective comparative;29–31,34,35,37–39 of these studies, six were randomized,29–31,34,38,39 of which only three studies were double blinded.29,31,34

Figure 1.

Literature search.

Abbreviation: LUTI, lower urinary tract infections.

Definitions of outcomes

As shown in Table 1, the definitions on treatment effect parameters were heterogeneous among the trials. Clinical success was defined as relief of symptoms and fever during the first 3–7 days.

Table 1.

Prospective studies of mecillinam for the treatment of pyelonephritis and Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia

| Pyelonephritis

| ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Design | Intervention | Patients (N) | Age (mean) (years) | Temperature (°C) | Male: female | Bacteremia (N) | Complicating factors (N) | Estimated AUP (N) | Pathogens (S to mecillinam) (N) | Clinical success | Bacteriological

|

Comment | |

| Success | Without relapse/ reinfection | |||||||||||||

| Trollfors et al (1982)38 | Randomized, open label, comparative | IV: mecillinam 800 mg tid 5 days Oral: P-MEC 400 mg tid 5 days Duration: 10 days |

25 | 19–76 (48) | ≥38.5 | 6:19 | 7 | 8 | ≤17 |

E. coli (S) (22) K. pneumoniae (S) (1) P. mirabilis (S) (2) |

15/25 | 24/25 | 18/23 (2 lower UTI) | The clinical outcome was significantly poorer (P<0.05) in patients with mecillinam. The study excluded resistant strains and negative culture |

| IV: cephaloridine 1 g tid 5 days Oral: cephalexin 500 mg tid 5 days Duration: 10 days |

26 | 18–83 (55) | 6:20 | 10 | 10 | ≤16 |

E. coli (S) (24) K. pneumoniae (S) (2) P. mirabilis (S) (1) |

25/26 | 26/26 | 18/24 (3 lower UTI) | ||||

| Ode et al (1983)39 | Randomized, open label, comparative | IV: mecillinam 1.2 g qid ≥3 days Oral: P-MEC 400 mg tid Duration: 28 days |

20 | 19–88 (56) | >37.5 | 4:16 | 4 | 6 | 14 |

E. coli (S) (17) E. coli (R) (1) P. mirabilis (S) (1) K. pneumoniae (R) (1) |

17/20 AUP: 12/14 |

12/18 AUP: 11/13 |

The resistant isolates were not evaluable for bacteriological evaluation because of change in therapy | |

| IV: trimetoprim 160 mg bid ≥3 days Oral: trimetoprim 160 mg bid Duration: 28 days |

22 | 32–86 (56) | 8:14 | 5 | 10 | 12 |

E. coli (17) P. mirabilis (1) K. pneumoniae (1) Others (3) |

18/22 | 12/21 | |||||

| IV: AMP 2 g qid ≥3 days Oral: P-AMP 600 mg tid Duration: 28 days |

21 | 20–86 (58) | 2:19 | 6 | 5 | 15 |

E. coli (18) K. pneumoniae (1) Others (2) |

16/21 | 13/20 | |||||

| Helin (1983)33 | Open label, noncomparative (pediatric) | Oral: P-MEC 25–40 mg/kg/day bid or tid Duration: 10 days |

20 | 0.5–14 (4) | >38.5 | 4:16 | – | 1 | – |

E. coli (S) (16) K. pneumoniae (S) (2) S. saphropyticus (R) (1) Others (R) (1) |

nd | 19/20 | 18/19 | Failure was seen in the patient with mixed Gram-positive bacteriuria. Relapse was seen in the patient with ureteral stenosis (K. pneumoniae) |

| Rotstein and Farrar (1983)37 | Open label, comparative | IV: mecillinam 10 mg/kg + AMP nd qid Duration: 4–10 days |

11 | 18–80 (39)a | nd | ~1/3 male | 4 | – | – |

E. coli (S) (16) E. coli (R) (5) |

11/11 | 11/11 | nd | 3/10 had clinical relapse (intervention group nd). In vitro synergism between mecillinam and other beta-lactam (P<0.025) |

| IV: mecillinam 10 mg/kg + CCC nd qid Duration: 4–10 days |

9 | 3 | 2 | – | K. pneumoniae (S) (5) | 8/9 | 9/9 | |||||||

| King et al (1983)35 | Open label, comparative | IV: mecillinam 10 mg/kg + AMP nd qid Duration: nd |

14 | nd | nd | ~50% male | nd | nd | nd | Gram-negative bacteria (31) |

26/28 | 21/31 | Low bacteriological cure rate in subgroup with complicated UTI | |

| IV: mecillinam 10 mg/kg + CCC nd qid Duration: nd |

14 | |||||||||||||

| Eriksson et al (1986)31 | Randomized, open label, comparative | IV: mecillinam 400 mg/AMP 500 mg tid (N=15) ~4 days Oral: P-MEC 200 mg/P-AMP 250 mg tid Duration: 14 days |

27 (IV: 15) | 15–86 (55) | ≥38 | 6:21 | 5 | 7 | 20 |

E. coli (25) S. saphropyticus (1) Others (2) |

25/27 (including no relapse) | 27/27 | 15/27 (only two clinical relapses) | Better clinical outcome in the combination group (P=0.002). With only S strains (P=0.06). Better bacteriological outcome in the combination group (P=0.007). Males |

| IV: AMP 1.4 g or tid ~4 days Oral: P-AMP 700 mg bid Duration: 14 days |

30 (IV: 17) | 16–82 (57) | 8:22 | 9 | 9 | 21 |

E. coli (24) K. pneumoniae (4) P. mirabilis (3) Others (2) |

16/30 (including no relapse) | 22/30 | 10/21 (only two clinical relapses) | and complicated infections (P=0.06) and high age (P<0.01) were more common in the unsuccessful treatment group | |||

| Jernelius et al (1988)34 | Randomized, double blinded, placebo controlled | Oral: P-MEC /P-AMP 400/500 mg tid 7 days + placebo tid 14 days Duration: 7 days |

32 | 18–81 (59) | ≥38 | 12:20 | 5 | 14 | 18 |

E. coli (S) (28) K. pneumoniae (S) (2) P. mirabilis (S) (1) S. saphropyticus (R) (2) Others (R) (1) Others (S) (2) |

29/32 Relapse: 3/32 |

9/32 | 14/32 | Significantly better bacteriological success (P=0.004) and lower relapse rate in the 3-week group, (P=0.02). Of the nine patients without bacteriological success in the 3-week group, seven had complicating factors. All bacteria had clinical success |

| Oral: P-MEC /P-AMP 400/500 mg tid 7 days + 200/250 mg tid 14 days Duration: 21 days |

29 | 16–78 (61) | 7:22 | 4 | 13 | 16 |

E. coli (S) (29) S. saphropyticus (R) (1) Others (R) (2) |

28/29 Relapse: 1/29 |

20/29 | 23/29 | ||||

| Cronberg et al (1995)29 | Randomized, double blinded, comparative | IV: mecillinam 600 mg/AMP 1.2 g bid ~3 days Oral: P-MEC 400 mg/P-AMP 500 mg bid Duration: 14 days |

65 | (61) | ≥38.5 | Estimated <50% male | 12 | nd | nd |

E. coli (49) K. pneumoniae (5) P. mirabilis (2) Others (12) |

41/60 | 44/60 | Therapeutic outcomes, parameters adherence rate, and adverse effects were similar in both groups. More severe adverse reactions in cephalosporin group (ie, diarrhea, Clostridium | |

| IV: cefotaxime 2 g bid ~3 days Oral: cefadroxil 800 mg bid Duration: 14 days |

71 | (61) | Estimated <50% male | 20 | nd | nd |

E. coli (58) K. pneumoniae (3) P. mirabilis (6) Others (16) |

45/70 | 50/70 | difficile. and fungal superinfection). The study used ITT analyses, however, since the majority of the studies used PP analysis we decided to use that | ||||

| Nicolle and Mulvey (2007)36 | Case report | Oral: P-MEC 400 mg bid Duration: 2 years |

1 | 47 | nd | 0:1 | – | 1 | 0 | ESBL – E. coli (S) (1) | Bacteriological and clinical success was seen over the following weeks after initiating the therapy, no relapse of ESBL producing E. coli over following 2 years | |||

| Jansåker et al (2015)40 | Observational noncomparative | Oral: P-MEC 400 mg tid Duration: 14 days |

6 | 23–78 (47) | nd | 0:6 | – | 0 | 6 |

E. coli (S) (6) K. pneumoniae (S) (1) |

6/6 | 6/6 | 4/5 (relapse: asymptomatic) | Including retrospective cases: bacteriological and clinical success 17/22 (77%). Bacteriological relapse 7/22 (32%). One ESBL producing E. coli infection with treatment success |

| Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Design | Intervention | Number of patients | Age (median) (years) | Male:female | Complicating factors | Pathogens | Results and comments |

| Frimodt-Møller and Ravn (1979)32 | Observational noncomparative | IV: mecillinam 10 mg/kg qid with/without one other antibiotics Duration: 4–10 days (median 7) |

5 | 47–85 (78) | 1:4 | All patients had serious comorbidities and impaired renal function |

E. coli (S) (2) K. pneumoniae (S) (2) K. oxytoca (S) (1) |

2/2 with monotherapy had clinical and bacteriological success 3/3 with concomitant therapy had clinical and bacteriological success |

| Ekwall et al (1980)30 | Randomized, open label, comparative | IV: mecillinam 10 mg/kg qid 7–14 days Oral: P-MEC 400 mg tid Duration: 21 days |

3 | 56–86 (57) | 1:2 | nd |

E. coli (S) Citrobacter sp (S) K. pneumoniae (S) |

2/3 had clinical and bacteriological success 1/3 had clinical and bacteriological failure (female with K. pneumoniae ) |

| IV: mecillinam 5 mg/kg + AMP 15 mg/kg qid 7–14 days Oral: P-MEC 200 mg + P-AMP 350 mg tid Duration: 21 days |

5 | 21–73 (45) | 3:2 | nd |

E. coli (S) (4) K. pneumoniae (S) E. coli (S) (3) |

4/5 had clinical and bacteriological success 1/5 had clinical and bacteriological failure (male with E. coli) 4/5 had clinical and bacteriological success |

||

| Nonrandomized | IV: mecillinam 10 mg/kg + AMP 30 mg/kg qid 7–14 days Oral: P-MEC 400 mg + P-AMP 700 mg tid Duration: 21 days |

5 | 52–87 (65) | 3:2 | Patients with serious comorbidities |

Citrobacter sp (S) P. mirabilis (S) (2) |

1/5 had clinical and bacteriological failure (male with Ec and Citrobacter sp) | |

| King et al (1983)35 | Open-label comparative (stratified cases) | IV: mecillinam 10 mg/kg + AMP nd qid Duration: nd |

11 | b | ~50% male | b | Gram-negative bacteria | 11/11 had clinical and bacteriological success |

| IV: mecillinam 10 mg/kg + CCC nd qid Duration: nd |

14 | 13/14 had clinical and bacteriological success | ||||||

Notes:

Including five cases with other infections.

Stratified cases of bacteremia caused by pyelonephritis (for detailed data refer Table 2).

Abbreviations: AMP, ampicillin; AUP, acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis; bid, two times daily; CCC, cephalosporin or carbenicillin; E. coli, Escherichia coli; ESBL, extended spectrum beta-lactamase; GI, gastrointestinal; ITT, intention to treat; IV, intravenous; K. oxytoca, Klebsiella oxytoca; K. pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae; nd, no data/not described; P. mirabilis, Proteus mirabilis; P-AMP, pivampicillin; P-MEC, pivmecillinam; PP, per protocol; qid, four times daily; SAR, severe adverse reaction; S, sensitive; S. saphropyticus, Staphylococcus saphropyticus; tid, three times daily; UTI, urinary tract infections.

Bacteriological success was heterogeneously defined; it was mainly defined as eradication of bacteria during or after therapy, although some studies included “no relapse or reinfection” in the definition and some studies defined bacteriological relapse separately (range 2–24 weeks). Therefore, to make the definition more homogenous in this review, we chose a wide definition of bacteriological success: bacterio-logically cured without relapse or reinfection. This lowered the bacteriological success rate in the studies that did not include bacteriological relapse or reinfection in the definition for bacteriological success. Very few studies described whether a bacteriological failure, relapse, or reinfection was symptomatic.

Outcomes

The 12 included clinical trials are described in Table 1. The trials were published from 1979 to 2015. They included a total of 296 adult patients with pyelonephritis and/or bacteremia; 57 patients were treated with P-MEC alone and 239 patients were treated with P-MEC and one other beta-lactam. The 20 pediatric patients with acute pyelonephritis were treated with P-MEC alone.

MEC in pyelonephritis

The summarized results for P-MEC for the treatment of pyelonephritis are shown in Table 2.38–40 The cumulative clinical success and the bacteriological success were 75% and 74%, respectively. Considerably higher treatment failure was found in complicated infections (ie, high age, males, bacteremia, and females with predisposing factors),38,39 and high treatment success was seen in the studies where AUP could be stratified.38,40 There are two cases with treatment success with P-MEC in pyelonephritis caused by ESBL producing E. coli.36,40 In a comparative study, MEC (800 mg tid) had significantly lower clinical success than cephaloridine 1 g tid (P<0.05).38 With a higher initial MEC dose of 1200 mg four times daily (qid), an overall superior treatment success was achieved compared to MEC 800 mg tid and with no difference compared to AMP and trimethoprim.39

Table 2.

Effect of mecillinam and mecillinam in combination with other beta-lactams for the treatment of pyelonephritis with and without bacteremia

| Mecillinam

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Without predisposing factors (AUP)

|

With predisposing factors

|

All pyelonephritis

|

|||

| Clinical success | Bacteriological success (without relapse/reinfections) | Clinical success | Bacteriological success (without relapse/reinfections) | Clinical success | Bacteriological success (without relapse/reinfections) | |

| Ode et al39 | 12/14 | 11/13a | 5/6 | 1/5b | 17/20 | 12/18b,b |

| Trollfors et al38 | Not possible to determine | 15/25 | 18/23c | |||

| Jansåker et al40 | 6/6 | 5/6 | – | – | 6/6 | 5/6 |

| Total | 18/20 (90%) | 16/19 (84%) | 5/6 (83%) | 1/5 (20%) | 38/51 (75%) | 35/47 (74%) |

|

Mecillinam in combination with other beta-lactams | ||||||

| Reference | Without predisposing factors (AUP) (overall successd) | With predisposing factors (overall successd) |

All acute pyelonephritis

|

|||

| Clinical success | Bacteriological success (without relapse/reinfections) | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Rotstein and Farrar37 | Not possible to determine | Not possible to determine | 16/20 | 20/20 | ||

| King et al35 | Not possible to determine | Not possible to determine | 26/28 | 21/31 | ||

| Eriksson et al31 | 11/20 | 4/7 | 25/27 | 15/27 | ||

| Jernelius et al34,e | 13/16 | 1/13 | 28/29 | 20/29 | ||

| Cronberg et al29 | Not possible to determine | Not possible to determine | 57/60 | 41/60 | ||

| Total | 24/36 (67%) | 5/20 (25%) | 152/164 (93%) | 117/167 (70%) | ||

Notes:

Resistant E. coli was not evaluable because change in therapy.

Resistant K. pneumoniae was not evaluable because change in therapy.

Two dropouts, three asymptomatic bacteriuria (different strains), and two bacteriuria with symptoms of LUTI.

Defined as both clinical success and bacteriological success, without bacteriological relapse.

Since it was significantly inferior, the 1-week therapy was not included.

Abbreviations: AUP, acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis; K. pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae; E. coli, Escherichia coli.

To our knowledge, there is only one pediatric clinical study on P-MEC.33 The author found an excellent bacteriological success (19/20) of P-MEC in children (0.5–14 years) with pyelonephritis, when administered as 25–40 mg/kg/day two times daily (bid)/tid for 10 days.

The summarized results for P-MEC combined with another beta-lactam (pivampicillin [P-AMP] in 141/163) for pyelonephritis are listed in Table 2. The clinical success and the bacteriological success were 93% and 70%, respectively. The combination of P-AMP/P-MEC had excellent clinical success within the first week of treatment. However, Jernelius et al found that the bacteriological success was 39% and 88% for AUP, with 1- and 3-week therapies, respectively (P=0.02). Symptomatic relapses were mainly lower UTI in both groups, and the few relapses found in the 3-week therapy were asymptomatic in >80% of the cases.34 The 2-week therapy demonstrated intermediate results as compared to the 1- and 3-week therapies.29,31 One study used a lower dose of P-MEC/P-AMP (0.2/0.25 g tid)31 compared to similar trials.29,34 The bacteriological success (56%) and overall success (ie, both clinical success and bacteriological success without relapse) in AUP (55%) were much lower in this study31 compared to the other studies, where the bacteriological success waŝ69%29,34 and the overall success in AUP was 81%.34 In the two studies that cases could be stratified into uncomplicated or complicated pyelonephritis, the overall success rates were 67% and 25%, respectively. It was found that patients of high age, males, and females with predisposing factors demonstrated a considerably lower and insufficient treatment success, mostly because of bacteriological failure.31,34 Eriksson et al31 found that MEC combined with AMP was superior both clinically and bacteriologically to AMP alone, in spite of a lower dosage in the combination therapy. AMP monotherapy was associated with higher selection of resistant strains to both AMP (P=0.02) and MEC (P=0.06) compared to combination therapy, which was not associated with the selection of resistant strains. Cronberg et al29 found that MEC combined with AMP for 14 days (IV followed by oral administration) had similar rates for treatment success, treatment discontinuation, and bacteriological relapses for acute pyelonephritis as treatment with a cephalosporin (IV followed by an oral administration). The relapse rate was similar to other studies on the MEC/AMP combination.30,34,39 Two studies compared MEC (10 mg/kg qid) combined with either AMP or cephalosporines (doses not defined).45,46 One of these studies found that both combinations had equal excellent outcome after a 4- to 10-day therapy.37 The second study found that the AMP combination had an inferior bacteriological success (duration not defined); yet, there was no difference in the bacteremia group.35

MEC in bacteremia

The data are very sparse on MEC given as monotherapy for bacteremia caused by Enterobacteriaceae. The results from the studies we found are listed in Table 3. Cumulatively, the clinical success and the bacteriological success were 67% (10/15) and 87% (13/15), respectively. The results for MEC combined with another beta-lactam (mostly AMP) on bacteremia caused by Enterobacteriaceae are listed in Table 3. Cumulatively, the clinical success and the bacteriological success were 88% (57/65) and 84% (53/63).

Table 3.

Effect of mecillinam and mecillinam in combination with other beta-lactams for the treatment of bacteremia caused by Enterobacteriaceae

| Reference | Cases | Clinical success | Bacteriological success (without relapse/reinfections) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Mecillinam

| |||

| Frimodt-Møller and Ravn32 | 2 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| Ekwall et al30 | 3 | 2/3 | 2/3 |

| Ode et al39 | 3 | 3/3 | 3/3 |

| Trollfors et al38 | 7 | 3/7 | 6/7 |

| Total | 15 | 10/15 (67%) | 13/15 (87%) |

|

Mecillinam in combination with other beta-lactams | |||

| Frimodt-Møller and Ravn32 | 3 | 3/3 | 3/3 |

| Ekwall et al30,a | 10 | 8/10 | 8/10 |

| Rotstein and Farrar37 | 7 | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| King et al35 | 25 | 24/25 | 24/25 |

| Eriksson et al31 | 4 | 4/4 | 2/2 |

| Jernelius et al34,b | 4 | 4/4 | 2–3/4 |

| Cronberg et al29 | 12 | 7/12 | 7/12 |

| Total | 64 | 57/65 (88%) | 53/63 (84%) |

Notes:

Twofold doses in 50% of the patients.

Since the 1-week therapy was significantly inferior, it is not included in this table.

Adverse reactions

The cumulative results of adverse reactions with MEC with/ without AMP for pyelonephritis and/or uropathogenic bacteremia are shown in Table 4. There was no serious adverse reaction, but approximately one of the five patients had an adverse reaction, which was mainly seen in the concomitant therapy groups.

Table 4.

ARs of mecillinam as monotherapy or combined with AMP

| Reference | Therapy | Exanthema | GI | Others | Total AR | Total SAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frimodt-Møller and Ravn32 | MEC or MEC/AMP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| Ekwall et al30,a | MEC/AMP, P-MEC/P-AMP | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5/73 | 0/73 |

| Ekwall et al30 | MEC/P-MEC | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Ode et al39 | MEC/P-MEC | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3/20 | 0/20 |

| Trollfors et al38 | MEC/P-MEC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/25 | 0/25 |

| Helin33 (pediatric) | P-MEC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/19 | 0/19 |

| Eriksson et al31 | MEC/AMP | 7 | 4 | 5 | 16/43 | 0/43 |

| Jernelius et al34 | P-MEC/P-AMP | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5/38 | 0/38 |

| Jernelius et al34 (21 days) | P-MEC/P-AMP | 0 | 11 | 1 | 12/39 | 0/39 |

| Cronberg et al29 | MEC/AMP, P-MEC/P-AMP | 12 | 15 | 5 | 32/144 | 0/144 |

| Total | Cumulative | 26 | 34 | 13 | 73/406b (18%) | 0/406 (0%) |

| Total | MEC | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Total | MEC/AMP | 24 | 32 | 13 | 69 | 0 |

Notes: We did not include the studies that did not report, specify, and/or categorize the side effects.

Half had double dose.

Some patients had more than one AR.

Abbreviations: AMP, ampicillin; AR, adverse reaction; GI, gastrointestinal; MEC, mecillinam; P-AMP, pivampicillin; P-MEC, pivmecillinam; SAR, serious adverse reaction.

Discussion

MEC has been used for AUP for several years in parts of Scandinavia. We found no evidence that MEC should be an insufficient alternative against AUP, but insufficient for patients with acute complicated pyelonephritis on bacteriological outcome, even when combined with AMP. From the published results, it seems that the regimen for AUP in adults should be P-MEC ≥400 mg tid (adjusted for weight) for at least 14 days in adults with/without initially IV MEC. Both clinical33 and retrospective data on resistance rates41 support a recommendation of P-MEC in pediatric pyelonephritis, administered as 25–40 mg/kg/day bid/tid for 10 days.33

The low bacteriological success rates in pyelonephritis31 and lower UTI caused by ESBL producing bacteria24 can largely be explained by suboptimal dosing with P-MEC 200 mg tid. Higher dosage and shorter dosing interval of MEC for UTI are suggested to attain sufficient time above minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC),42 especially for ESBL producing E. coli (manuscript in preparation). Studies similar to Eriksson et al31 that administered P-MEC as 400 mg instead of 200 mg demonstrated a higher bacteriological success rate.29,34 Similarly, the lesser clinical effect of MEC compared to cephaloridine for pyelonephritis38 could also be explained by the lower dosage of 800 mg tid, since no difference was found when dosing MEC 1.2 g qid compared to AMP and trimethoprim.39 Hence, a higher dose of P-MEC, eg, 1000 mg tid, could be more beneficial in pyelonephritis than the currently recommended doses, which should also be sufficient for ESBL producing strains. The duration should be 14 days in pyelonephritis as the bacteriological effect seems to increase with duration,29,31,34 and since there is still missing solid evidence that a short (eg, 7 days) course is sufficient for P-MEC.

Interestingly, MEC with or without AMP demonstrated satisfactory success on bacteremia caused by Enterobacteriaceae.29–32,34,35,37–39 A Danish retrospective study reported a favorable 30-day mortality outcome of MEC (23%) compared to other antibiotics (43%) for Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–0.9).43 Although MEC seems to be effective against selected cases of uropathogenic bacteremia, we do not recommend MEC to be used alone when urosepsis is suspected but administered together with an aminoglycoside to broaden the antimicrobial spectra for empirical treatments.

Synergism with MEC and other beta-lactams occurs because MEC is an amidinopenicillin, with more selective affinity to penicillin-binding protein 2, as compared with aminopenicillins or cephalosporines.44 This synergism has been investigated clinically in a few studies,29–31,34,37 but only one study found a significant difference (P<0.025).37 Cumulatively, there seems to be a difference in outcomes between monotherapy and combination therapy (75% and 93% clinical success, respectively), which could be explained by the synergistic effect. MEC alone was also seen bacteriologically inferior in pyelonephritis compared to a cephalosporin,38 but not when combined with AMP.29 Synergism and higher bactericidal activity have also been demonstrated in vitro between MEC and clavulanic acid.18,45

The side effects of monotherapy with P-MEC are described as few and mild.2 This is similar to the findings of this study (Table 4). However, concomitant therapy of MEC and AMP was associated with mild adverse reactions in one of the five patients treated.

A major limitation with these old studies is that they fail to describe the clinical details in the cases of bacteriological failures/relapses, which was frequently seen in many papers regarding complicated infections. This is of major importance since asymptomatic bacteriuria is much less worrisome than a symptomatic bacteriological failure/relapse. Thus, we believe that clinical success represents the major outcome, which was excellent in the majority of the studies.

Although the reviewed studies were well designed and conducted at the time, they were conducted several decades ago, comparator drugs are uncommon today, the included sample sizes were generally small, the clinical picture on bacteriological failure/relapse was limited, and many used definitions of disease and outcome that vary from current standards. This severely limits the possibility to provide sufficient evidence-based recommendations to treat AUP with MEC. Therefore, there is an urgent need of clinical controlled trials comparing a single, standardized dose of P-MEC/MEC with other currently recommended antimicrobial treatments of uncomplicated and complicated pyelonephritis and sepsis.

A recent meta-analysis on the duration of antibiotic therapy for pyelonephritis with or without bacteremia concluded that 7 days of treatment is equivalent to longer therapies (including beta-lactams).46 However, the analysis only included one study with MEC,34 in which 7 days was found to be significantly bacteriologically inferior to 21 days of treatment. With this in consideration, we believe that the first randomized control study on the subject preferably should be a noninferiority trail comparing MEC in a higher dosage of 1000 mg tid with ciprofloxacin in currently recommended dosage13 for 7 days.

Conclusion

MEC is an important older antimicrobial drug, which based on limited number of studies may be considered as an alternative in AUP, especially in patients with high predicted probability of bacteria with resistance to fluoroquinolone and other first-line agents. MEC may also be considered for pediatric pyelonephritis. Randomized clinical trial comparing the drug with standard of care regimens is warranted. There are currently no sufficient data to support the use of MEC in patients with bacteremia or sepsis due to Enterobacteriaceae.

Acknowledgments

The Departments of Clinical Microbiology at the University Hospital of Copenhagen, Rigshospitalet and Hvidovre, funded the study.

Footnotes

Author contributions

FJ came up with the idea, designed and conducted the study and wrote the review. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Lund F, Tybring L. 6-amidinopenicillanic acids – a new group of antibiotics. Nat New Biol. 1972;236:135–137. doi: 10.1038/newbio236135a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dewar S, Reed LC, Koerner RJ. Emerging clinical role of pivmecillinam in the treatment of urinary tract infection in the context of multidrug-resistant bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;69:303–308. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolle LE. Pivmecillinam in the treatment of urinary tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46(suppl 1):35–39. discussion 63–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NORM/NORM-VET 2016 . Usage of Antimicrobial Agents and Occurrence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Norway. Tromsø/Oslo: 2017. print. electronic. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Statens Serum Institut, National Veterinary Institute, National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark DANMAP 2016 - Use of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from food animals, food and humans in Denmark. [Accessed January 20, 2018]. Available from: https://www.danmap.org/

- 6.Swedres-Svarm 2016 Consumption of Antibiotics and Occurrence of Resistance in Sweden Solna/Uppsala. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graninger W. Pivmecillinam – therapy of choice for lower urinary tract infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;22(suppl 2):73–78. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(03)00235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahlmeter G, Poulsen HO. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Escherichia coli from community-acquired urinary tract infections in Europe: the ECO.SENS study revisited. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schito GC, Naber KG, Botto H, et al. The ARESC study: an international survey on the antimicrobial resistance of pathogens involved in uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34:407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahlmeter G, Ahman J, Matuschek E. Antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli causing uncomplicated urinary tract infections: a European update for 2014 and comparison with 2000 and 2008. Infect Dis Ther. 2015;4:417–423. doi: 10.1007/s40121-015-0095-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahlmeter G, Menday P. Cross-resistance and associated resistance in 2478 Escherichia coli isolates from the Pan-European ECO.SENS Project surveying the antimicrobial susceptibility of pathogens from uncomplicated urinary tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:128–131. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poulsen HO, Johansson A, Granholm S, Kahlmeter G, Sundqvist M. High genetic diversity of nitrofurantoin- or mecillinam-resistant Escherichia coli indicates low propensity for clonal spread. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:1974–1977. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America; European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e103–e120. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjerrum L, Gahrn-Hansen B, Grinsted P. Pivmecillinam versus sulfamethizole for short-term treatment of uncomplicated acute cystitis in general practice: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2009;27:6–11. doi: 10.1080/02813430802535312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferry SA, Holm SE, Stenlund H, Lundholm R, Monsen TJ. Clinical and bacteriological outcome of different doses and duration of pivmecillinam compared with placebo therapy of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection in women: the LUTIW project. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2007;25:49–57. doi: 10.1080/02813430601183074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicolle LE. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection in adults including uncomplicated pyelonephritis. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35:1–12. v. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostri P, Frimodt-Moller C. Concentrations of mecillinam and ampicillin determined in serum and renal tissue: a single-dose pharmacokinetic study in patients undergoing nephrectomy. Curr Med Res Opin. 1986;10:117–121. doi: 10.1185/03007998609110428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampri N, et al. Mecillinam/clavulanate combination: a possible option for the treatment of community-acquired uncomplicated urinary tract infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2424–2428. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tärnberg M, Ostholm-Balkhed A, Monstein HJ, Hällgren A, Hanberger H, Nilsson LE. In vitro activity of beta-lactam antibiotics against CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:981–987. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Titelman E, Iversen A, Kahlmeter G, Giske CG. Antimicrobial susceptibility to parenteral and oral agents in a largely polyclonal collection of CTX-M-14 and CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. APMIS. 2011;119:853–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2011.02766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas K, Weinbren MJ, Warner M, Woodford N, Livermore D. Activity of mecillinam against ESBL producers in vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:367–368. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Kelly F, Kavanagh S, Manecksha R, Thornhill J, Fennell JP. Characteristics of gram-negative urinary tract infections caused by extended spectrum beta lactamases: pivmecillinam as a treatment option within South Dublin, Ireland. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:620. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1797-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansaker F, Frimodt-Moller N, Sjogren I, Dahl Knudsen J. Clinical and bacteriological effects of pivmecillinam for ESBL-producing Escherichia coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae in urinary tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;69:769–772. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soraas A, Sundsfjord A, Jorgensen SB, Liestol K, Jenum PA. High rate of per oral mecillinam treatment failure in community-acquired urinary tract infections caused by ESBL-producing Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lægehåndbogen [webpage on the Internet] Pyelonefritis. 2017. [Accessed January 20, 2018]. Available from: http://www.sundhed.dk/sundhedsfaglig/laegehaandbogen/nyrer-og-urinveje/tilstande-og-sygdomme/infektioner/pyelonefritis/

- 26.pro.medicin [webpage on the Internet] Akut pyelonefritis. 2017. [Accessed January 20, 2018]. Available from: http://pro.medicin.dk/Specielleemner/Emner/318561#a000.

- 27.Antibiotikasentret.for.primærmedisin [webpage on the Internet] Pyelonefritt. 2017. [Accessed January 20, 2018]. Available from: http://www.antibiotikaiallmennprak-sis.no/index.php?action=showtopic&topic=hpwDhzb5&j=1.

- 28.pro.medicin [webpage on the Internet] Akut pyelonefritis/urosepsis. 2017. [Accessed January 20, 2018]. Available from: https://pro.medicin.dk/Specielleemner/Emner/318559#a000.

- 29.Cronberg S, Banke S, Bruno AM, et al. Ampicillin plus mecillinam vs. cefotaxime/cefadroxil treatment of patients with severe pneumonia or pyelonephritis: a double-blind multicentre study evaluated by intention-to-treat analysis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:463–468. doi: 10.3109/00365549509047047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekwall E, Scheja A, Cronberg S, et al. Mecillinam and ampicillin separately or combined in gram-negative septicemia. Infection. 1980;8:37–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01677397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eriksson S, Zbornik J, Dahnsjö H, et al. The combination of pivampicillin and pivmecillinam versus pivampicillin alone in the treatment of acute pyelonephritis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1986;18:431–438. doi: 10.3109/00365548609032360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frimodt-Moller N, Ravn TJ. Mecillinam in urinary tract infections and in septicaemia. Infection. 1979;7:35–37. doi: 10.1007/BF01640555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helin I. Pivmecillinam in the treatment of childhood pyelonephritis. J Int Med Res. 1983;11:113–115. doi: 10.1177/030006058301100209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jernelius H, Zbornik J, Bauer CA. One or three weeks’ treatment of acute pyelonephritis? A double-blind comparison, using a fixed combination of pivampicillin plus pivmecillinam. Acta Med Scand. 1988;223:469–477. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1988.tb15899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King JW, Beam TR, Jr, Neu HC, Smith LG. Systemic infections treated with amdinocillin in combination with other beta-lactam antibiotics. Am J Med. 1983;75:90–95. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicolle LE, Mulvey MR. Successful treatment of ctx-m ESBL producing Escherichia coli relapsing pyelonephritis with long term pivmecillinam. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39:748–749. doi: 10.1080/00365540701367801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rotstein C, Farrar WE., Jr Amdinocillin in combination with beta-lactam antibiotics for treatment of serious gram-negative infections. Am J Med. 1983;75:96–99. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trollfors B, Jertborn M, Martinell J, Norkrans G, Lidin-Janson G. Mecillinam versus cephaloridine for the treatment of acute pyelonephritis. Infection. 1982;10:15–17. doi: 10.1007/BF01640830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ode B, Flamholc L, Walder M, Cronberg S. Intravenous mecillinam, trimethoprim, and ampicillin in acute pyelonephritis. Drugs Exper Clin Res. 1981;9:337–343. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jansaker F, Hertz F, Frimodt-Moller N, Knudsen JD. Pivmecillinam treatment of community-acquired uncomplicated pyelonephritis based on sparse data. Glob J Infect Dis Clin Res. 2015;1(1):014–017. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salomonsson P, von Linstow ML, Knudsen JD, et al. Best oral empirical treatment for pyelonephritis in children: do we need to differentiate between age and gender? Infect Dis. 2016;48:721–725. doi: 10.3109/23744235.2016.1168937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frimodt-Moller N. Correlation between pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters and efficacy for antibiotics in the treatment of urinary tract infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19:546–553. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedersen G, Schonheyder HC, Sorensen HT. Antibiotic therapy and outcome of monomicrobial gram-negative bacteraemia: a 3-year population-based study. Scand J Infect Dis. 1997;29:601–606. doi: 10.3109/00365549709035903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neu JC. Synergy of mecillinam, a beta-amidinopenicillanic acid derivative, combined with beta-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976;10:535–542. doi: 10.1128/aac.10.3.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neu HC. Synergistic activity of mecillinam in combination with the beta-lactamase inhibitors clavulanic acid and sulbactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;22:518–519. doi: 10.1128/aac.22.3.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eliakim-Raz N, Yahav D, Paul M, Leibovici L. Duration of antibiotic treatment for acute pyelonephritis and septic urinary tract infection – 7 days or less versus longer treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:2183–2191. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]