Abstract

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) is the federal government’s largest form of food assistance, and a frequent focus of political and scholarly debate. Previous discourse in the public health community and recent proposals in state legislatures have suggested limiting the use of SNAP benefits on unhealthy food items, such as sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs). This paper identifies two possible underlying motivations for item restriction, health and morals, and analyzes the level of empirical support for claims about the current state of the program, as well as expectations about how item restriction would change participant outcomes. It also assesses how item restriction would reduce individual agency of low-income individuals, and identifies mechanisms by which this may adversely affect program participants. Finally, this paper offers alternative policies to promote healthier purchasing and eating among SNAP participants that can be pursued without reducing individual agency. Health advocates and officials must more fully weigh the attendant risks of implementing SNAP item restrictions, including the reduction of individual agency of a vulnerable population.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) is the federal government’s largest form of food assistance - costing nearly $74 billion in 2015 - and a frequent focus of political and scholarly debate (USDA Food and Nutrition Service, 2017). The program serves nearly 46 million people across the nation; the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) 2015 analysis of 22.5 million participating households found that over 40% of program beneficiaries were under 18 years old, and over 20% are over 60 years old or disabled (Gray et al., 2016). The program’s funding has been reduced twice over the last four years, and Congressional leaders expressed interest in further lowering the program’s cost and size (http://www.cbpp.org/research/snap-benefits-will-be-cut-for-nearly-all-participants-in-november-2013http://www.cbpp.org/research/snap-benefits-will-be-cut-for-nearly-all-participants-in-november-2013; Chokshi, 2014; Anon., 2014; Anon, 2014).

Previous discourse in the public health community (Barnhill, 2011; Ludwig et al., 2012) and proposals in state legislatures (Brattin, 2015; Wisconsin Legislature, n.d.; Richie, 2016) have suggested limiting the use of SNAP benefits on unhealthy food items, such as sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), justified, in part, as potential methods for improving the health of participants. In the past, several states have requested permission from USDA, the federal agency that oversees the program, to implement these types of item restrictions. Though these proposals have been rejected, state legislatures and administrators continue to discuss similar mechanisms for controlling what SNAP can buy. Additionally, the perspectives of SNAP participants regarding item restriction have not been systematically studied in ways that are representative (Leung et al., 2017; Leung et al., 2013; Blumenthal et al., 2014).

This paper presents an ethical argument against item restriction, based on the value of individual agency, which is uniquely constrained and regulated among welfare recipients. Even if SNAP administrators can effectively impose these restrictions on participants, should they?

1. Logistics and motivations for item restriction

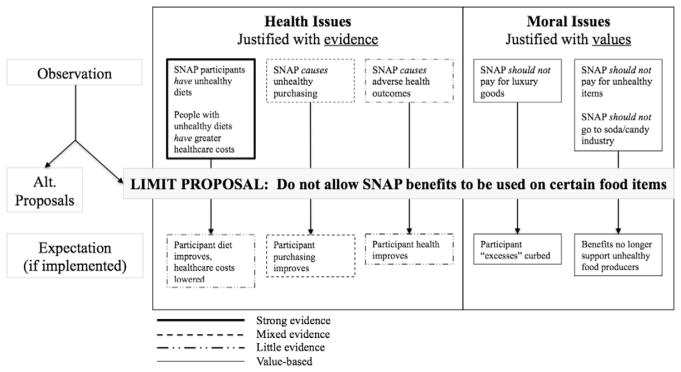

Two primary motivations are identified for restricting items that can be purchased with SNAP benefits: health issues and moral issues (see Fig. 1). Though health officials may only subscribe to the former motivation, both are offered for comparison.

Fig. 1.

Summary of motivations to prohibit certain items from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Different observations of unfavorable circumstances surrounding the program are used to justify a variety of proposals to improve outcomes. Excepting the current health status of program participants, no other evidence-based observation or expectation is backed by unequivocal evidence.

The first primary motivation, poor health outcomes of individuals and families, is frequently cited in calls to reform and limit purchases made with SNAP benefits, with some estimating that item limits will yield decreased consumption of unhealthy products by participating households, ultimately resulting in lower healthcare costs (Gundersen, n.d.; Basu et al., 2013). Results from empirical assessments of a poor health-SNAP connection are mixed, ranging from studies demonstrating a weak relationship to obesity, to others showing significant reductions in likelihood of being obese among program participants (Gundersen, n.d.). At least for SSBs, USDA economists do not expect item restriction to lower consumption among SNAP participants, who may substitute cash for banned items; however, these claims are difficult to evaluate empirically, as a ban’s impact cannot be assessed within an active SNAP participant population, limiting the predictive capacity of econometric models (Todd & Ver, 2014).

Beyond concerns for the physical wellbeing of SNAP recipients, specifically their diets, some proposed restrictions focus on moral concerns. State legislatures in Maine, Wisconsin, and New York have recently explored SNAP prohibitions on “luxury” foods, such as lobster or steak (Brattin, 2015; Wisconsin Legislature, n.d.; Richie, 2016). While this concern is not supported by data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SNAP participants consume less beef and shellfish than the general population) (Cole & Fox, 2008), or a recent USDA analysis (Grasky et al., 2016), proposed bans invoke a moral belief that these items should be foregone by individuals making a good-faith effort toward self-sufficiency.

Examples already exist of morally motivated item eligibility for SNAP purchasing, such as the prohibition of alcohol. Though the majority of Americans consume alcohol (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016), these beverages are excluded from SNAP spending (USDA Food and Nutrition Service, 2016). Conversely, other agricultural products, such as seeds for growing fruits and vegetables, represent unique caveats for SNAP purchasing; though not necessarily food items, seeds are allowed to promote certain behaviors - gardening or farming - viewed as positive (USDA Food and Nutrition Service, 2016).

It is not only the content of SNAP expenditures that is subject to restriction, but also where purchasing may occur. While supermarkets are by far the main points of SNAP redemption (Castner & Henke, 2011), much attention has recently been given to farmers’ markets (SNAP EBT Equipment Resources, n.d.). USDA has overseen a vast expansion of redemption technology (via electronic benefit transfer, or EBT) to farmers’ markets, again evincing a perspective that these venues for SNAP purchasing are worth promoting in ways that others (e.g., highly-accessible and affordable fast food restaurants) are not (Anon., n.d.).

Some also suggest that implementing SNAP restrictions is logistically feasible. Examples from state and local-level systems include those that allow retailers to flag product classes for taxation (e.g., tobacco), as well as the item-specific Women, Infants, and Children Program (Pomeranz & Chriqui, 2015). Others cite public support for certain item restrictions, even among some SNAP participants, as evidence of the political feasibility of such reforms (Pomeranz & Chriqui, 2015; Long et al., 2014). The existence of item restriction proposals, such as one by former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, also seem to prove the point that such programmatic changes are logistical and political possibilities, at least in certain settings (Daines & Farley, 2010; Hartocollis, 2010).

2. Reduced agency: an ethical risk of item restriction

Sociologists and economists have provided theoretical frameworks for considering individual agency (Sen, 1992; Sen, 1985). Put simply, agency describes one’s ability to make and execute choices (Ruger, 2003). In practice, these choice sets for a SNAP participant are far narrower than the universe of food items; social, cultural, economic, or environmental contexts serve as choice-expanding or (more often) choice-narrowing factors. By focusing on the choices of the poor, and by targeting a program that is critical to their everyday decisions and budgeting (Edin et al., 2013), SNAP restrictions selectively limit these abilities within an already agency-constrained population.

Among SNAP recipients, agency-influencing contexts may include living with unemployment or poverty wages, amenity-poor neighborhoods, low mobility, and high exposure to unhealthy food and beverage advertising (Gray et al., 2016; Hillier, 2012). Indeed, some researchers suggest that poverty is the most influential contextual factor on food choices, and that healthy food affordability poses a significant and critical barrier (Drewnowski & Eichelsdoerfer, 2010). These contexts and their effect on food choice - in particular, but not limited to SNAP shopping - are not well understood. Furthermore, the introduction of additional rules for SNAP purchasing not only reduces the agency of participants, but also is unlikely to be uniformly experienced across different contexts.

Benefit amounts provide another example of how context may influence the effect of restrictions on individual agency. While SNAP has been shown to reduce food insecurity, only 48% of participating households report being food secure (Committee on Examination of the Adequacy of Food Resources and SNAP Allotments et al., 2013). Previous research has also shown how some households decrease their caloric intake or skip meals at the end of the month, as SNAP benefits are exhausted (Todd, 2015; Hamrick & Andrews, 2016). For certain participants, SNAP benefits are effectively the only funds available to be spent on food, as any cash resources are quickly allocated to other needs, such as rent, medications, or debts (Edin et al., 2013). Especially for the estimated 22.2% of participant households without any gross income (Gray et al., 2016), a prohibition of specific food items could be interpreted as a de facto dietary restriction, rather than subtle nudging toward healthier choices, while for the 31.8% of SNAP households with some form of gross income, greater flexibility between SNAP benefits and cash may already exist for specific food items. Still, there is disagreement on how individuals may respond to SNAP bans (Ludwig et al., 2012; Todd & Ver, 2014). While individual agency would inevitably be reduced with item restriction, the effect on overall diet is unclear.

Several ways that restrictions may reduce agency for SNAP users operate through stigma against the program and its participants (Gundersen, n.d.; Wahowiak, 2015). Current SNAP standards force participants to either avoid common household items such as toilet paper or diapers, or complete two separate payments at checkout, one for SNAP-eligible items, and another for ineligible products. Though these items can be conveniently acquired at supermarkets, this additional step is both a unique inconvenience for SNAP participants and visible procedure that may identify individuals as SNAP recipients to other shoppers.

Researchers have also noted the importance of EBT cards for reducing stigma, as they are rendered for payment in the same way as a credit or debit card (Atasoy et al., 2010; Zekeri, 2003). Conflicting evidence, however, indicates that this system may still be widely recognizable as welfare (Dolan et al., 2012; Kasperkevic, 2014; Card, 2016). Additional SNAP restrictions will result in increased in dual-payment checkouts; the exact magnitude of this increase will depend on participants’ willingness to use cash for prohibited goods and the speed of their adaptation to new rules, as well as any accommodations made by retailers.

This is not to say that agency-constraining policies or programs are inherently harmful or unethical. Indeed, agency-reducing policies are the cornerstone of many public health initiatives with broad population-level benefits. However, it is important to understand why these policies - which exclusively apply to a vulnerable population - are favored over possible alternatives and, to differentiate between moralistic and health-oriented policies, advocates should make their motivations explicit.

3. Alternatives to item restriction to improve health of SNAP participants

Four alternative options are presented that may also improve the health of participants while appreciating the low-income contexts in which food choices are made, preserving individual agency and avoiding increased stigmatization (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Possible health-promoting alternative policies to item restriction in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

| Healthy item incentives | Unhealthy item taxes | SNAP schedule change | Healthier products | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oversight | NGO, State, USDA | Local, State | State, USDA | Industry |

| Cost to Gov’t | Expense | Revenue | No change | No change |

| Benefits | Lowers financial risk of trying new healthy foods | Lowers consumption | Favored by retailers | Population-level effect |

| Risk | Financial sustainability, who pays | SNAP exempt from sales tax | Possible challenges for participants | Major changes across global corporations |

| Agency impact | Increase | No change | No change | No change |

First, incentive-based initiatives around the country, including the federal Healthy Incentives Project (HIP), demonstrate ways to encourage SNAP participants to spend benefits on fruits and vegetables (Wilde et al., 2015). Similar to item restriction proposals, this alternative grows out of a concern over the diets of SNAP participants; however, this model is reinforced by empirical evidence: participants consume fewer fruits and vegetables than higher-income individuals (Wolfson & Bleich, 2015). By offering a financial bonus when shoppers buy produce with SNAP, these programs have increased consumption of healthy foods while preserving participants’ freedom to choose (Klerman et al., 2014). Some studies have found that incentives, when paired with item restrictions, can achieve favorable dietary outcomes, though others have found that participants favor increased benefit amounts over this hybrid incentive-restriction (Leung et al., 2017; Harnack et al., 2016). While the long-term funding strategy for bonus programs is subject to question, it exists as a proven method of improving SNAP participants’ nutritional decisions.

Second, “sin taxes” on unhealthy products, such as SSBs, may have population-wide effects. When applied as sales taxes, these efforts will have no effect on SNAP purchasing, as benefits are exempt from this type of taxation (Zheng et al., 2013). However, applied as an excise tax on distributors, all consumers will likely face increased prices. Thus, SNAP participants would face the same choices as the general population, and not be uniquely forced to spend from one income source versus another, as with item restriction. Furthermore, the revenue raised can be dedicated to other health promotion or community development initiatives, as in Berkeley, California and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Falbe et al., 2015; Gostin, 2017).

Third, researchers have theorized mechanisms by which the distribution schedule for SNAP benefits may result in negative health consequences. Most states distribute benefits once monthly, and many participants spend nearly all of the benefits in the first two weeks, creating cycle of food abundance and scarcity (Castner & Henke, 2011). This “feast-famine” dynamic may lead to overeating, especially of satiating items with low nutritive value (Dinour et al., 2007). Amended benefit schedules may help buffer the highs and lows of this cycle; for instance, distributing SNAP twice a month, versus a single infusion, would decrease waiting in between allocations. Furthermore, these types of reforms are supported by retailers who desire a more consistent revenue stream, which, in turn, enhances their ability to operate in lower-income, SNAP-dependent neighborhoods (Pennsylvania Food Merchants Association, 2016; Anon, n.d.; Migdail-Smith, n.d.; TEGNA, n.d.).

Finally, encouraging or mandating food manufacturers to reformulate products is another means of improving health outcomes of SNAP participants without restricting choice. For example, several major companies committed to reduce calories, sodium and sugar content as part of former First Lady Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move!” Initiative (Let’s Move Initiative, n.d.). This alternative recognizes the influence exerted on consumers through marketing and promotion, and shifts more responsibility for healthy item choice to upstream actors. By focusing on the poor food choices made by all Americans, not just SNAP participants, and avoiding dramatic changes in shopping behavior, this alternative stands to have the largest population-level effect.

4. Conclusion

There is a great need to move SNAP further toward achieving its namesake and goal of “Nutrition Assistance.” Yet, while it may be plausible and perhaps politically attractive to restrict SNAP participants, reasonable alternatives also stand to improve health outcomes, several of which have potential for broader, population-level impact. All manner of choices are limited for the poor, and ethical trade-offs exist between promoting health and further narrowing individual agency or increasing stigma. If health researchers and practitioners wish to lend their energies to advocating for SNAP item restrictions, these trade-offs should first be carefully considered.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant number T32 HL007034).

References

- SNAP benefits will be cut for nearly all participants. Cent Budg Policy Priorities. 2013 Nov; [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 20]; Available from:. http://www.cbpp.org/research/snap-benefits-will-be-cut-for-nearly-all-participants-in-november-2013.

- Anonymous. President Obama signs $8.7 billion food stamp cut into law [internet] MSNBC. 2014 [cited 2017 Mar 20]; Available from:. http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/obama-signs-food-stamp-cut.

- Anonymous. SNAP Preparing for 19-day Benefits Distribution in Kentucky. NACS Online - Media - News Archive. n.d [Internet]. [cited 2017 Mar 21]; Available from:. http://www.nacsonline.com/Media/daily/pages/nd0618152.aspx#.WNB6BRIrJE4.

- Anonymous. Summary of the 2014 farm bill nutrition title: includes bipartisan improvements to SNAP while excluding harsh house provisions [internet] Cent Budg Policy priorities. 2014 [cited 2017 Mar 20]; Available from:. http://www.cbpp.org/research/summary-of-the-2014-farm-bill-nutrition-title-includes-bipartisan-improvements-to-snap.

- Anonymous. USDA Announces Grants to Enable More Farmers Markets to Serve Low-Income Families. USDA Newsroom. n.d [internet]. [cited 2016 May 11]; Available from:. http://www.usda.gov/wps/portal/usda/usdahome?contentidonly=true&contentid=2015/05/0123.xml.

- Atasoy S, Mills BF, Parmeter CF, et al. Paperless food assistance: the impact of electronic benefits on program participation [internet] Agricultural & Applied Economics Association 2010 Joint Annual Meeting. 2010 [cited 2017 Mar 22]. Available from:. http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/60964/2/10816.pdf.

- Barnhill A. Impact and ethics of excluding sweetened beverages from the SNAP program. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(11):2037–2043. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Seligman H, Bhattacharya J. Nutritional policy changes in the supplemental nutrition assistance program: a microsimulation and cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Decis Mak. 2013;33(7):937–948. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13493971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal SJ, Hoffnagle EE, Leung CW, et al. Strategies to improve the dietary quality of supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) beneficiaries: an assessment of stakeholder opinions. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(12):2824–2833. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013002942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brattin R. HOUSE BILL NO 813. 2015 [Internet]. Available from:. http://www.house.mo.gov/billtracking/bills151/billpdf/intro/HB0813I.PDF.

- Card Husbands R. Identity Concealment Device [Internet] 2016 [cited 2017 Mar 20]; Available from:. http://www.google.com/patents/US20160113369.

- Castner L, Henke J. Benefit Redemption Patterns in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Research and Analysis; Alexandria, VA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health [internet] 2016 Available from:. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015.htm.

- Chokshi N. Why the food stamp cuts in the farm bill affect only a third of states [Internet] Wash Post. 2014 [cited 2017 Mar 20]; Available from:. https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/govbeat/wp/2014/02/05/why-the-food-stamp-cuts-in-the-farm-bill-affect-only-a-third-of-states/

- Cole N, Fox MK. Diet Quality of Americans by Food Stamp Participation Status: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2004 [Internet] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Research, Nutrition and Analysis; Alexandria, VA: 2008. Available from:. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/NHANES-FSP.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Examination of the Adequacy of Food Resources and SNAP Allotments, Food and Nutrition Board, Committee on National Statistics, Institute of Medicine, National Resource Council. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Examining the Evidence to Define Benefit Adequacy. National Academies Press; 2013s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daines RF, Farley TA. No Food Stamps for Sodas [Internet] N Y Times. 2010 [cited 2017 Mar 20]; Available from:. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/07/opinion/07farley.html.

- Dinour LM, Bergen D, Yeh MC. The food insecurity–obesity paradox: a review of the literature and the role food stamps may play. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(11):1952–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan EM, Seiling SB, Braun B, Katras MJ. Having their say: rural mothers talk about welfare. Poverty Public Policy. 2012;4(2):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Eichelsdoerfer P. Can low-income Americans afford a healthy diet? Nutr Today. 2010;44(6):246–249. doi: 10.1097/NT.0b013e3181c29f79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Boyd M, Mabli J, et al. SNAP Food Security In-Depth Interview Study [Internet] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Research and Analysis; Alexandria, VA: 2013. [cited 2016 May 13]. Available from:. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/SNAPFoodSec.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Falbe J, Rojas N, Grummon AH, Madsen KA. Higher retail prices of sugar-sweetened beverages 3 months after implementation of an excise tax in Berkeley, California. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2194–2201. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostin LO. 2016: the year of the soda tax. Milbank Q. 2017;95(1):19–23. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasky S, Mbwana K, Romualdo AT, Manan R. Foods Typically Purchased by SNAP Households [Internet] IMPAQ International, LLC for USDA, Food and Nutrition Service; 2016. Available from:. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/SNAPFoodsTypicallyPurchased.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gray KF, Fisher S, Lauffer S. Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households: Fiscal Year 2015 [Internet] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Policy Support; Alexandria, VA: 2016. Available from:. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/Characteristics2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen C. SNAP and Obesity [Internet] n.d Available from:. http://www.ukcpr.org/sites/www.ukcpr.org/files/documents/DP2013-02_0.pdf.

- Hamrick KS, Andrews M. SNAP participants’ eating patterns over the benefit month: a time use perspective. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnack L, Oakes JM, Elbel B, Beatty T, Rydell S, French S. Effects of subsidies and prohibitions on nutrition in a food benefit program: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1610–1619. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartocollis A. A Push to Ban Soda Purchases With Food Stamps [internet] N Y Times. 2010 [cited 2017 Mar 20]; Available from:. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/07/nyregion/07stamps.html.

- Hillier A. Concentration of Tobacco Advertisements at SNAP and WIC Stores, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Prev chronic dis [internet] 2015. 2012:12. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140133. [cited 2017 Mar 22] Available from:. https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/Issues/2015/14_0133.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kasperkevic J. Food Stamps: Why Recipients are Haunted by Stigmas and Misconceptions [Internet] The Guardian. 2014 [cited 2017 Mar 20]; Available from:. https://www.theguardian.com/money/2014/apr/17/food-stamps-snap-coordinators-challenges.

- Klerman JA, Bartlett S, Wilde P, Olsho L. The short-run impact of the healthy incentives pilot program on fruit and vegetable intake. Am J Agric Econ. 2014;96(5):1372–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Let’s Move Initiative. Accomplishments. Let’s Move! [Internet] n.d http://www.letsmove.gov/accomplishments.

- Leung CW, Hoffnagle EE, Lindsay AC, et al. A qualitative study of diverse experts’ views about barriers and strategies to improve the diets and health of supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) beneficiaries. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(1):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung CW, Musicus AA, Willett WC, Rimm EB. Improving the nutritional impact of the supplemental nutrition assistance program: perspectives from the participants. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(Suppl 2):S193–S198. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long MW, Leung CW, Cheung LWY, Blumenthal SJ, Willett WC. Public support for policies to improve the nutritional impact of the supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP) Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(1):219–224. doi: 10.1017/S136898001200506X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig DS, Blumenthal SJ, Willett WC. Opportunities to reduce childhood hunger and obesity: restructuring the supplemental nutrition assistance program (the food stamp program) JAMA. 2012;308(24):2567–2568. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.45420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migdail-Smith L. Grocery stores plead for more time on SNAP food cards, reading eagle - NEWS [internet] Read Eagle. n.d [cited 2017 Mar 21]; Available from:. http://readingeagle.com/news/article/grocery-stores-plead-for-more-time-on-snap-food-cards.

- Pennsylvania Food Merchants Association. SNAP Distribution Schedule Change. SPECTRUM [Internet] 2016:78. Available from:. http://www.pfma.org/uploads/3/7/7/2/37727363/oct2016_spect_web.pdf.

- Pomeranz JL, Chriqui JF. The supplemental nutrition assistance program: analysis of program administration and food law definitions. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):428–436. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie P. NY State Senate Bill S6761 [Internet] NY State Senate. 2016 [cited 2017 Mar 20]; Available from:. https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2015/s6761/amendment/original.

- Ruger JP. Health and development. Lancet. 2003;362(9385):678. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14243-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. Commodities and Capabilities. North-Holland; Amsterdam: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. Inequality Reexamined. Oxford; New York: Russell Sage Foundation; Clarendon Press; Oxford Univ. Press New York; 1992. [cited 2016 Jul 19]. Available from:. http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3053251 (Internet) [Google Scholar]

- SNAP EBT Equipment Resources. Food and Nutrition Service [Internet] n.d [cited 2017 Mar 20];Available from:. https://www.fns.usda.gov/ebt/snap-ebt-equipment-resources.

- TEGNA. Idaho to stagger release of food stamps [internet] KTVB. n.d [cited 2017 Mar 21]; Available from:. http://www.ktvb.com/news/local/idaho/idaho-to-stagger-release-of-food-stamps/135494430.

- Todd JE. Revisiting the supplemental nutrition assistance program cycle of food intake: investigating heterogeneity, diet quality, and a large boost in benefit amounts. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2015;37(3):437–458. [Google Scholar]

- Todd JE, Ver Ploeg M. Caloric beverage intake among adult supplemental nutrition assistance program participants. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):e80–e85. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA Food and Nutrition Service. Eligible Food Items [Internet] USDA Food Nutr Serv. 2016 [cited 2017 Mar 20];Available from:. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/eligible-food-items.

- USDA Food and Nutrition Service. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation and Costs [Internet] 2017 Available from:. https://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/pd/SNAPsummary.pdf.

- Wahowiak L. SNAP restrictions can hinder ability to purchase healthy food: stigma, payment options among issues. Natl Health. 2015;45(6):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wilde P, Klerman JA, Olsho LEW, Bartlett S. Explaining the impact of USDA’s healthy incentives pilot on different spending Outcomes. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2015:ppv028. [Google Scholar]

- Wisconsin Legislature. AB177: bill text [internet] n.d [cited 2017 Mar 20]; Available from:. http://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2015/related/proposals/ab177.

- Wolfson JA, Bleich SN. Fruit and vegetable consumption and food values: National patterns in the United States by supplemental nutrition assistance program eligibility and cooking frequency. Prev Med. 2015;76:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zekeri AA. South Rural Dev Center Food Assist Policy Ser. 2003. Opinions of EBT recipients and food retailers in the rural south; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, McLaughlin EW, Kaiser HM. Taxing food and beverages: theory, evidence, and policy. Am J Agric Econ. 2013;95(3):705–723. [Google Scholar]