Abstract

Diabetic nephropathy accounts for most the excess mortality in individuals with diabetes, but the molecular mechanisms by which nephropathy develops are largely unknown. Here we tested cytosine methylation levels at 397,063 genomic CpG sites for association with decline in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) over a six year period in 181 diabetic Pima Indians. Methylation levels at 77 sites showed significant association with eGFR decline after correction for multiple comparisons. A model including methylation level at two probes (cg25799291 and cg22253401) improved prediction of eGFR decline in addition to baseline eGFR and the albumin to creatinine ratio with the percent of variance explained significantly improving from 23.1% to 42.2%. Cg22253401 was also significantly associated with eGFR decline in a case-control study derived from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort. Probes at which methylation significantly associated with eGFR decline were localized to gene regulatory regions and enriched for genes with metabolic functions and apoptosis. Three of the 77 probes that associated with eGFR decline in blood samples showed directionally consistent and significant association with fibrosis in microdissected human kidney tissue, after correction for multiple comparisons. Thus, cytosine methylation levels may provide biomarkers of disease progression in diabetic nephropathy and epigenetic variations contribute to the development of diabetic kidney disease.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, gene expression

INTRODUCTION

Nephropathy is a serious complication of diabetes mellitus that often leads to end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Diabetic nephropathy is the most common cause of ESRD in the United States and most developed nations.1,2 Virtually all of the excess mortality experienced by diabetic individuals relative to those without diabetes occurs in those with nephropathy.3 Treatment of hyperglycemia and blood pressure can reduce risk of nephropathy to some extent,4–7 but the molecular mechanisms by which diabetic kidney disease develops remain unknown. Familial aggregation of diabetic nephropathy indicates that genetic factors may be involved in disease pathogenesis.8–10 Although a few well-replicated single nucleotide variants associated with the disease have been recently identified,11,12 most most of the heritability remains uexplained. Epigenetic variations, such as in DNA methylation, may play a role in disease susceptibility and may explain part of the heritability for complex traits.13,14 DNA methylation mostly occurs at the cytosine base in cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) sequences. Most of the genome has low CpG content, and cytosines in low CpG regions are generally methylated. Most promoter regions, in contrast, have high CpG content (CpG islands), and methylation in CpG islands is variable. Methylation of CpG islands plays a key role in regulating gene expression as methylation levels can interfere with transcription factor binding. Methylation changes that occur in gene regulatory regions, such as promoters or enhancers, are likely to be functional.15

Several lines of evidence suggest that epigenetic factors may contribute to risk of diabetic nephropathy. Epigenetic mechanisms have been implicated in the “metabolic memory” by which reduction in risk for diabetic complications induced by intensive treatment of glycemia remains reduced after the treatment period is over.16 Studies in cellular and animal models have shown that hyperglycemia can induce persistent histone modification changes, which could influence pathways related to diabetic kidney disease,17–20 but few studies have been performed in patients to validate these results. Ko et al identified significant cytosine methylation differences in tubule cells of kidneys obtained from patients with chronic kidney disease compared with those from healthy individuals.21 Kidney-specific cytosine methylation changes were enriched in regulatory regions and correlated with expression of pro-fibrotic genes, indicating that epigenetic changes are likely to play a role in disease development.

Several studies have identified particular CpG sites, measured in peripheral blood, that are differentially methylated between individuals with and without diabetic nephropathy.22–24 Apart from a small study in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC),24 these studies have been cross-sectional, and, since cytosine methylation levels can change over time, it is uncertain whether the differences in methylation preceded onset of diabetic nephropathy or whether they developed as a consequence of nephropathy. Longitudinal studies are required to determine the extent to which cytosine methylation levels are associated with risk of developing diabetic kidney disease. The identification of CpG sites at which methylation levels are predictive of diabetic nephropathy may not only provide markers that can be useful indicators of disease prognosis, but may also yield important clues about disease pathogenesis. In the present study, we analyzed the extent to which DNA methylation, measured in peripheral blood in diabetic Pima Indians with chronic kidney disease, associates with development of subsequent ESRD and subsequent changes in renal function, as measured by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). The Pima Indians are an American Indian population with a high prevalence of type 2 diabetes and a high risk of diabetic ESRD;25,26 over 90% of the ESRD which occurs in this population is attributable to diabetes.26

RESULTS

Cytosine methylation levels and association with baseline eGFR

We conducted a nested case-control study27–29 to assess association of methylation levels with development of ESRD in individuals with diabetes and established chronic kidney disease [albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR) ≥300 mg/g or eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2] at baseline. The study involved 181 Pima Indians, selected from a longitudinal study.25 Baseline characteristics for participants are shown in Table 1. In keeping with the matched case-control design, there were no significant differences between those who developed ESRD and those who did not in sex, duration of diabetes or age.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in methylation studies.

| All | Case | Control | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 181 | 80 | 101 | |

| Age (yrs) | 53.5 ± 12.0 | 52.9 ± 10.0 | 54.0 ± 13.4 | 0.53 |

| Sex | 66 male, 112 female | 32 male, 48 female | 37 male 64 female | 0.65 |

| Duration (yrs) | 18.1 ±7.1 | 18.3 ± 13.2 | 17.9 ± 7.7 | 0.71 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 140.3 ± 20l8 | 145.1 ± 19.7 | 136.6 ± 20.9 | 0.0055 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 80.9 ± 11.3 | 83.3 ± 12.3 | 79.0 ± 10.1 | 0.011 |

| mBP (mm Hg) | 100.7 ± 12.6 | 103.9 ± 13.2 | 98.2 ± 11.4 | 0.0028 |

| HbA1c (%) | 10.0 ± 2.2 | 10.3 ± 2.1 | 9.7 ± 2.2 | 0.069 |

| ACR (mg/g) | 985.7 | 2026.3 | 542.2 | 8.2E-10 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 78.1 ± 31.0 | 69.8 ± 33.8 | 84.7 ± 27.0 | 0.0015 |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.11 ± 0.68 | 1.34 ± 0.90 | 0.92 ± 0.34 | 0.00015 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 31.6 ± 6.6 | 31.4 ± 6.8 | 31.7 ± 6.5 | 0.75 |

| Bisulfite Conversion Efficiency | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 0.93 |

Data are mean ± SD, except for N and sex, which are reported as counts, and ACR, which is reported as the median. P-values are for the comparison between cases and controls, and were calculated by t-tests, except for sex (Fisher’s exact test) and ACR (Wilcoxon rank sum test).

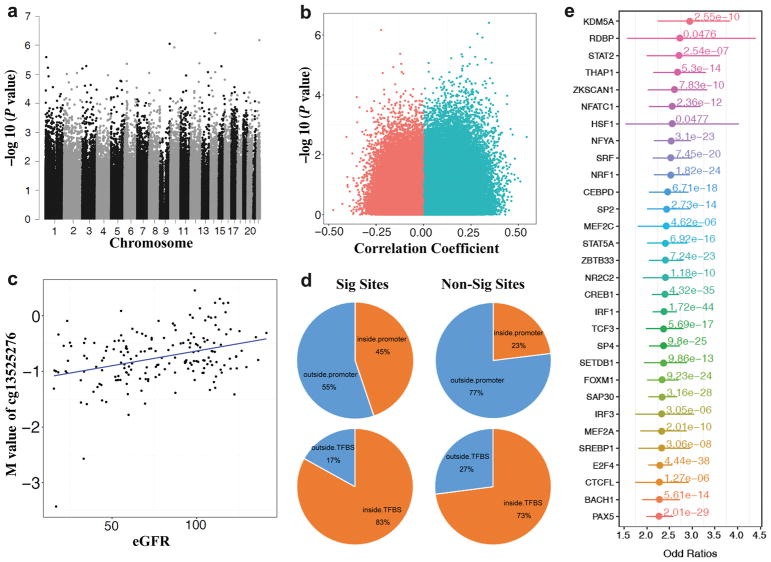

Cytosine methylation was measured in baseline peripheral blood samples with the Infinium HumanMethylation450 Beadchip, resulting in methylation level measures at 397,063 CpG sites. We performed epigenome wide association analysis between cytosine methylation levels and baseline eGFR. Results are shown in Figure 1a. The relationship between effect size and the p-value for association is shown in Figure 1b. After adjustment for multiple comparisons none of the sites achieved genome-wide significance [false discovery rate (FDR)<0.05], but the association with eGFR at several sites approached significance. The strongest association between methylation level and eGFR levels was with cg13525276 (on chromosome 14) in the gene body of TSHR (P=3.87×10−7, FDR=0.119). Figure 1c shows the relationship of methylation level at the top probe with eGFR. The top 20 sites with the strongest evidence for association of methylation with baseline eGFR are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Summary of association between methylation at CpGs and baseline eGFR. (A) Manhattan plot of 397,063 methylation probes used for the analysis. The X-axis represents the chromosomal position, while the y-axis is the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the p-value. P-values were calculated with adjustment for age, sex, duration of diabetes, mean blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, batch, cell type and conversion efficiency. (B) Volcano plot analysis of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (x-axis without adjustment for covariates) between M value and eGFR across 181 samples. Y-axis, -log(P-value adjusted for covariates) of the linear regression. Overall more probes showed positive correlation with eGFR (higher methylation level at higher eGFR) (C) Correlation between the top differentially methylated locus and eGFR. X-axis represent eGFR, y-axis represents M-value for cg13525276. Each dot is one single individual. (Pearson Correlation, Coefficient=0.345, P-value=1.95e-6); (D) Comparison of the genomic distribution of the 1435 significant probes associated with eGFR (p-value < 0.05 and absolute value of effect size in top 1%) and non-significant probes. Significant CpGs more likely to be located within human promoter regions than non-significant CpGs (Odds Ratio=2.71, Chi-square Test P-value < 2.2e-16), and they were more likely to be located in transcription factor binding sites (TFBS, Odds Ratio=1.82, Chi-square Test P-value<2.2e-16); (E) Enrichment of significant CpG loci associated with eGFR (uncorrected p-value < 0.05 and absolute value of effect size in tpo 1%) for each of 128 transcription factor binding sites (TFBS), compared with nonsignificant CpG loci. X-axis, odds ratios with 95%CI; the corrected p-value of fisher exact test for each TFBS is also shown.

Table 2.

Top 20 probes at which methylation level associates with baseline eGFR after adjustment 6 cell types (CD8T, CD4T, NK, Bcell, Mono, Gran).

| Probe Name | Effect Size | P-value | Partial R | Chr | Position | RefGene Name | Refgene Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg13525276 | 0.0062 | 3.87E-07 | 0.40 | 14 | 81426012 | TSHR | Body |

| cg14400768 | −0.0078 | 6.73E-07 | −0.39 | 22 | 46609193 | PPARA | Body |

| cg13914004 | 0.0056 | 9.02E-07 | 0.39 | 9 | 130659670 | ST6GALNAC6 | Body |

| cg06298701 | 0.0090 | 1.20E-06 | 0.38 | 10 | 51566673 | NCOA4 | 5’UTR |

| cg19809157 | 0.0049 | 2.55E-06 | 0.37 | 1 | 9422438 | SPSB1 | Body |

| cg06383241 | −0.0085 | 4.19E-06 | −0.36 | 12 | 116997022 | MAP1LC3B2 | TSS200 |

| cg19021318 | 0.0038 | 4.36E-06 | 0.36 | 6 | 30689568 | TUBB | Body |

| cg20791839 | 0.0047 | 5.23E-06 | 0.36 | 3 | 53926047 | SELK | TSS200 |

| cg11098259 | 0.0048 | 5.32E-06 | 0.36 | 15 | 58430391 | AQP9 | TSS200 |

| cg18368411 | 0.0125 | 5.96E-06 | 0.36 | 1 | 31845959 | FABP3 | TSS200 |

| cg00294109 | 0.0093 | 6.38E-06 | 0.36 | 3 | 3219781 | CRBN | Body |

| cg18625627 | 0.0053 | 8.40E-06 | 0.35 | 14 | 81426015 | TSHR | Body |

| cg14373760 | 0.0129 | 8.44E-06 | 0.35 | 13 | 99961037 | GPR183; UBAC2 | TSS1500; Body |

| cg02090160 | −0.0080 | 9.10E-06 | −0.35 | 2 | 172958880 | — | — |

| cg21856744 | 0.0095 | 9.10E-06 | 0.35 | 8 | 663745 | ERICH1 | Body |

| cg18110243 | 0.0055 | 9.86E-06 | 0.35 | 2 | 37384171 | EIF2AK2 | 5’UTR |

| cg17812850 | 0.0134 | 1.08E-05 | 0.35 | 4 | 148538527 | TMEM184C | TSS200 |

| cg02586551 | 0.0052 | 1.10E-05 | 0.35 | 11 | 73693988 | UCP2 | TSS200 |

| cg15616998 | −0.0054 | 1.17E-05 | −0.35 | 1 | 40435396 | MFSD2A | 3’UTR |

| cg26954121 | 0.0064 | 1.34E-05 | 0.35 | 14 | 23749076 | HOMEZ | Body |

Effect size is the regression coefficient: M unit methylation per ml/min/1.73m2, adjusted for age, sex duration of diabetes, HbA1c, mean blood pressure, batch, cell type and conversion efficiency

We also performed analyses without adjustment for cell type. The order of the top 20 associated sites changed modestly, but methylation differences at several sites remained strongly associated, and one site in CRBN achieved FDR<0.05 (cg00294109, P=1.03×10−7, FDR=0.041, Table S1). This suggests that results are largely due to cell type autonomous methylation changes rather than cell type composition induced methylation variation.

Top eGFR associated regions are localized to gene regulatory regions of metabolic genes

Cytosine methylation levels of gene regulatory regions, promoters or enhancers are more likely to be functional compared with those that lie outside of regulatory regions. To expand the analysis we used all 1435 probes whose association reached nominal significance with baseline eGFR (P<0.05 and top 1% of absolute value of effect size). As shown in Figure 1d, 45% of these probes localized to gene promoter regions compared with 23% of probes for those probes that did not show significant association with eGFR (P<2.2×10−16 for difference in proportions). There were no significant differences in the proportion of probes that localized to gene body regions. These results indicate that loci that showed statistical association with eGFR are likely to be functional as they are localized to the regulatory genome.

To further assess the functional regulatory role of identified methylated loci we examined the overlap of differentially methylated loci and transcription factor binding sites. We used the ENCODE database (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTrackUi?db=hg19&g=hub_4607_uniformTfbs&hubUrl=http://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/ensembl/encode/integration_data_jan2011/hub.txt) to download validated transcription factor binding regions (across 91 different cell lines Figure 1d). Overall, 83% of these significant probes localized to transcription factor binding sites compared with 73% of non-significant probes. Importantly, this analysis showed that differentially methylated regions are enriched on specific transcription factor binding sites, including chromatin modifiers and inflammation associated transcription factors, such as STAT2, STAT5A and IRF (Figure 1e).

Differentially methylated genes are involved in cell cycle apoptosis and metabolism

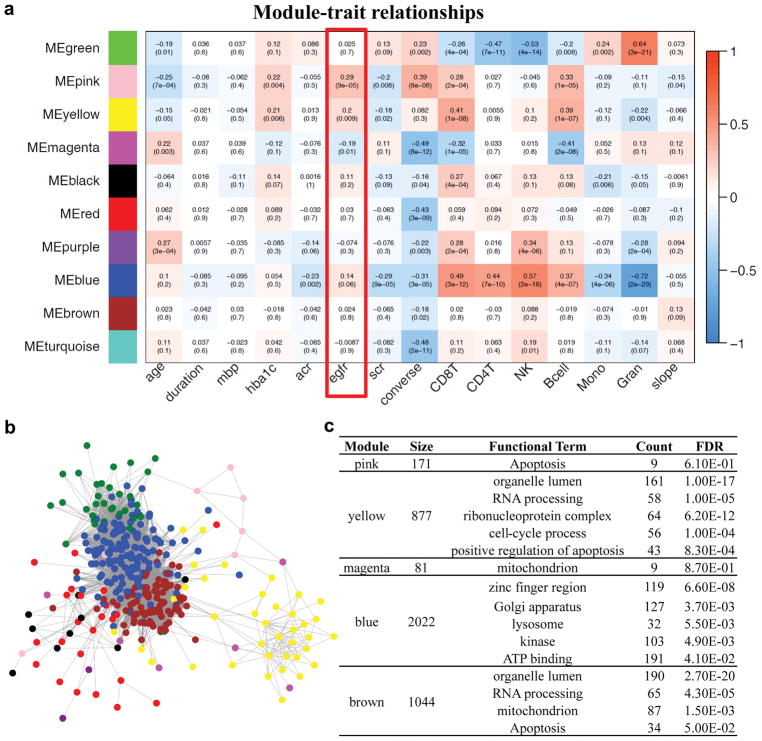

To understand the biological role of genes at which methylation levels associated with diabetic kidney disease we performed weighted gene coregulatory network analysis (WGCNA).30 WCGNA tests for internal correlation among methylation levels, and, once this internal correlation is established, co-regulated modules are correlated with clinical characteristics. Assessment of the relationship between clinical phenotypes and methylation in gene networks may have a higher likelihood of detecting significant changes than analysis of individual probes. For this analysis we only used the methylation levels of CpG sites within promoter regions available on the arrays (28376 genes), as promoter methylation changes likely influence gene expression; in addition, the target gene can be identified. Our analysis identified 10 specific modules of co-methylation at the promoter. Next we examined the correlation between modules and clinical phenotypes. As shown in Figure 2a, methylation levels of probes in the pink module showed the strongest positive correlation with baseline eGFR (R=0.29, P=9×10−5). The functional feature with greatest enrichment for this module was involvement in apoptosis (9 of 171 genes). The yellow and magenta modules also showed statistically significant association with eGFR, and the involved genes were also associated with cell cycle and apoptosis and mitochondrial function. Graphical representation of the differentially methylated promoters generated several networks (Figure 2b). In summary, genes at which methylation was associated with eGFR were enriched for involvement in cell cycle apoptosis and metabolism (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) of methylation levels for 28,376 promoter regions. (A) The correlation between the phenotypes and the each eigengene of 10 gene modules identified by WGCNA. Each cell represents Person’s correlation coefficient and p-value. (B) Networks among the differentially methylated promoters. (C) The functional annotation of included genes for each candidate module.

Cytosine methylation levels are associated with future decline in eGFR

Cross-sectional association between cytosine methylation and clinical parameters cannot establish causality. On the other hand, longitudinal analyses of the relationship between baseline methylation and subsequent phenotypic changes can identify methylation patterns predictive of, and more likely causally related to, disease risk. Therefore, we studied association between methylation levels and future kidney functional decline. We first examined association of methylation levels with development of ESRD as a binary outcome. The Manhattan plot of the association of individual sites and ESRD development is shown in Figure S1. No site achieved statistical significance following multiple testing correction (FDR<0.05). The 20 sites with the strongest associations with development of ESRD are shown in Table S2. The strongest association occurred on chromosome 2 with cg27556193 (P=8.48×10−6 FDR=0.84; this site was near OTX1).

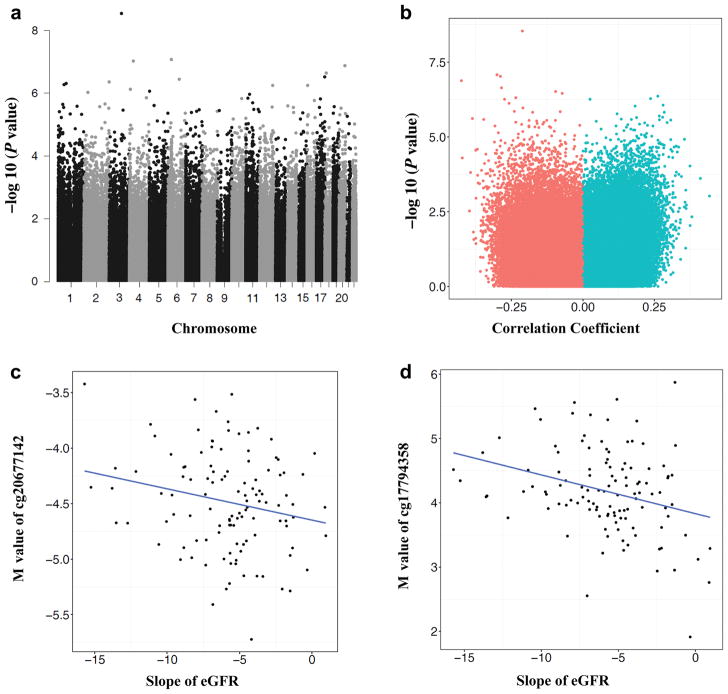

To augment statistical power, we analyzed rate of functional decline as a continuous variable. As random effects models are often robust to outliers, we used a mixed effects model to estimate best linear unbiased predictor (BLUP) slopes and intercepts (Figure S2).31 The eGFR slope was calculated over an average of 5.6 (SD=3.5) years of follow-up. Analyses of association of methylation at each CpG site with subsequent slope in eGFR are shown in Figure 3. The Manhattan plot of the association of probes with eGFR slope is shown in Figure 3a; effect size and p-value are shown in Figure 3b. There were 77 sites associated with subsequent eGFR slope that passed multiple testing correction (FDR<0.05). The top 20 sites are shown in Table 3. The strongest association was observed with cg20677142 on chromosome 3 near the transcription start site for CDGAP (P=2.87×10−9) (Figure 3c), while the second strongest was observed with cg17794358 on chromosome 6 (Figure 3d), near ATF6B and FKBPL. The complete list of 77 sites that showed statistically significant association with eGFR slope is given in Table S3. The table also contains information on the association with baseline eGFR and with development of ESRD. Results were largely unchanged with additional adjustment for body mass index (Table S4). For most of these probes, the association remained statistically significant in the absence of adjustment for cell type (Table S5).

Figure 3.

Summary association between methylation at CpGs and eGFR slope. (A) Manhattan plot of 397,063 methylation probes used for the analysis. The X-axis represents the chromosomal position, while the y-axis is the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the p-value. P-values were calculated with adjustment for age, sex duration, Hba1c, mean blood pressure, batch, conversion efficiency, and cell type. (B) Volcano plot analysis of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (x-axis without adjustment for covariates) between M values and eGFR slope across 115 samples. Y-axis, −log(P-value with adjustment for covariates) of the linear regression. Correlation coefficient<0 means higher methylation is associated with more rapid eGFR decline; (C) Correlation between methylation at cg20677142and eGFR slope. X-axis represents eGFR slope, y-axis represents M-value at cg20677142. Each dot is one single individual. The probe cg20677142 is located at chr3 and close to the TSS of CDGAP. (D) Correlation between methylation at g17794358 and eGFR slope. X-axis represents eGFR slope, y-axis represents M-value at g17794358. Each dot is one single sample. The probe cg17794358 is located at chr6 and close to ATF6B and FKBPL. (E) The chromosomal location of the cg20677142 probe. Coler codes for chromatin states are: red = predicted promoter, orange = enhancer, yellow = weak enhancer, green = transcribed region. (F) The chromosomal location of the cg17794358 probe. Color codes are as in Figure 3E.

Table 3.

Top 20 probes whose methylation levels associated with eGFR slope after adjustment for 6 cell types (CD8T, CD4T, NK, Bcell, Mono, Gran).

| Probe Name | Effect Size | P-value | Partial R | Chr | Position | RefGene Name | Refgene Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg20677142 | −5.5083 | 2.87E-09 | −0.59 | 3 | 119012899 | CDGAP | TSS1500 |

| cg17794358 | −3.2946 | 8.36E-08 | −0.54 | 6 | 32097257 | ATF6B;FKBPL | TSS1500;Body |

| cg09616494 | −2.2392 | 9.48E-08 | −0.54 | 4 | 36333625 | DTHD1 | Body |

| cg25799291 | −2.8907 | 1.33E-07 | −0.53 | 20 | 55685277 | — | — |

| cg01295785 | −3.6623 | 2.29E-07 | −0.52 | 18 | 12437948 | — | — |

| cg14530304 | −10.5843 | 3.04E-07 | −0.52 | 17 | 77777792 | — | — |

| cg11341657 | −4.6622 | 3.53E-07 | −0.52 | 6 | 107811567 | SOBP | 5’UTR |

| cg10553596 | 3.0437 | 4.36E-07 | 0.51 | 2 | 242751847 | NEU4 | TSS200 |

| cg07923233 | −0.7575 | 4.92E-07 | −0.51 | 1 | 76080727 | — | — |

| cg06985721 | 4.8905 | 5.27E-07 | 0.51 | 1 | 55464653 | BSND | 5’UTR |

| cg16690037 | −6.2651 | 5.54E-07 | −0.51 | 16 | 4377663 | — | — |

| ch.12.123150169F | −1.7516 | 5.55E-07 | −0.51 | 12 | 124584216 | — | — |

| cg25655234 | −1.5508 | 7.50E-07 | −0.50 | 4 | 7194841 | SORCS2 | 1stExon |

| cg12670963 | 1.7885 | 8.60E-07 | 0.50 | 5 | 1511422 | LPCAT1 | Body |

| cg11073121 | 3.0624 | 9.40E-07 | 0.50 | 2 | 37039119 | VIT | Body |

| cg15427520 | −2.2549 | 1.07E-06 | −0.50 | 11 | 35252384 | CD44 | 3’UTR |

| cg22253401 | −3.1677 | 1.40E-06 | −0.49 | 4 | 162369223 | FSTL5 | Body |

| cg27164771 | −6.0591 | 1.43E-06 | −0.49 | 11 | 19138675 | ZDHHC13 | TSS200 |

| cg02444484 | 2.5549 | 1.49E-06 | 0.49 | 10 | 95372040 | PDE6C | TSS1500 |

| cg10213328 | −4.6052 | 1.51E-06 | −0.49 | 17 | 37309414 | — | — |

Effect size is regression coefficient: [ml/min/1.73m2/year] per M unit methylation, adjusted for age, sex duration of diabetes, HbA1c, mean blood pressure, batch, conversion efficiency and cell type estimates.

We compared the functional distribution of the 3490 significant probes whose association with eGFR slope reached nominal significance (P<0.05 and absolute value of effect size in top 1%) with non-significant probes (as we did for the baseline eGFR analyses). The significant probes were again more likely than non-significant probes to be located in gene promoters (31% versus 23%), and more likely to be located in transcription factor binding sites (81% versus 73%) (P< 2.2×10−16 for both Figure S3a). The most highly enriched transcription factor binding site was ESRRA, which is a key transcriptional regulator for a variety of genes (Figure S3b).

To further understand the functional role of the top sites at which methylation was associated with eGFR slope, we examined the RefSeq genomic annotation. Figure 3e shows the location of the cg20677142 probe. The cg20677142 probe is located in the annotated promoter region of CDGAP. We also examined the ENCODE functional annotation of this region in the kidney and in other cell lines. In the human kidney, the genomic region containing this probe showed strong enrichment for H3K4me3 histone marks, which indicate an active promoter region (Figure 3e). The region also showed enrichment for active enhancer marks, such as H3K27ac and H3K4Me1. In other ENCODE cell lines, this genomic region is marked as apromoter in most cell types (Figure 3e). Figure 3f shows the chromosomal location of the cg17794358 probe, which is located in an exonic region of FKBPL. The region containing this probe also shows strong enrichment for H3K4me3 and H3K4Me1 histone marks in human kidney cell lines (Figure 3f). This genomic region is also marked as a promoter in most ENCODE cell types. These findings suggest that these genic regions are associated with gene expression regulation in the human kidney.

We again used WGCNA analysis (Figure 2) to understand the functional role of genes at which methylation levels in promoter regions were associated with eGFR slope. We found that one gene group (pink) showed statistically significant association with eGFR decline. Pathway analysis of this cluster contained genes associated with function in the apoptosis pathway. The brown module containing probes for mitochondrial and apotosis pathways showed an association of borderline statistical significance (p=0.09). In summary our analysis identified multiple probes at which methylation significantly associated with future kidney function decline after multiple testing correction; these regions are enriched for regulatory elements in the genome, and they encode genes enriched for apoptosis and metabolism.

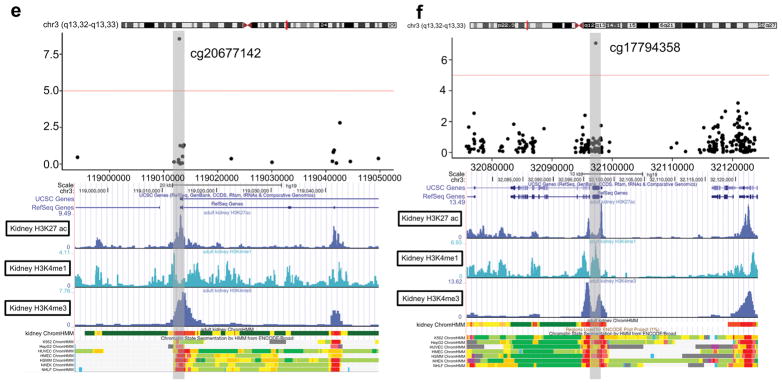

Kidney function associated probes in blood also correlate with fibrosis associated changes in the kidney

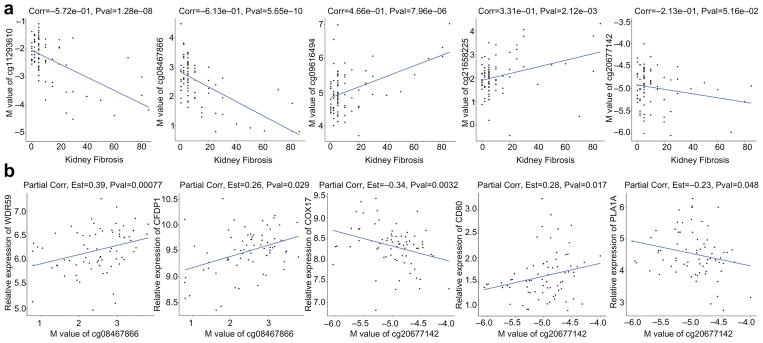

Given that many epigenetic changes are cell-type specific, a critical question is whether methylation levels observed in blood samples reflect methylation levels in cell types relevant to disease pathogenesis. Renal tubule epithelial cells play a key role in diabetic kidney disease, and we have previously performed genome wide cytosine methylation analysis of microdissected human kidney tubule samples using the Infinium 450K arrays.21 Our dataset included 94 samples obtained from patients with and without diabetes and diabetic CKD. The dataset includes clinical information (age, sex, race, GFR), and structural analysis (level of tubulointersitial fibrosis, glomerulosclerosis). We applied a linear regression model and adjusted for the same covariates as in blood samples to identify loci at which methylation correlates with fibrosis. We analyzed the 77 differentially methylated regions observed in blood samples that correlated with future functional decline. We found that 5 of these regions were nominally significantly correlated with degree of fibrosis in kidney tubule samples and 3 of the sites were correlated in the direction consistent with that observed in blood (Figure 4a); at all 3 of these sites the association remained significant after Bonferroni correction for the number of sites analyzed (p<6.5×10−4). Furthermore, 2 of these 5 CpG regions were identified to be correlated with the expressed levels of their adjacent genes, including WDR59, CFDP1, COX17, CD80, and PLA1A (Figure 4b). These results indicate that some CpG sites at which methylation levels in blood samples associate with eGFR decline also demonstrate correlation between renal fibrosis and methylation levels in kidney, and may reflect pathological processes in kidney tissue.

Figure 4.

A) Correlation of top eGFR slope predicting loci with kidney fibrosis. X axis shows degree of kidney fibrosis and y axis shows the methylation level in kidney samples. These 5 loci were identified in blood samples as they were able to predict kidney function decline. B) Significant correlations of these probes with expression of nearby transcripts in kidney tissue samples.

Extent to which methylation measures can improve current prognostic biomarkers

Markers of kidney function currently used in clinical practice (eGFR, ACR) are limited in their ability to distinguish individuals at high risk of kidney disease progression from those at low risk. Therefore, we also examined whether differentially methylated sites can improve the existing eGFR slope prediction model (i.e., in addition to baseline eGFR and ACR) among our initial cohort of individuals with chronic kidney disease at baseline. Baseline eGFR and ACR show consistent correlation with functional decline and therefore these two variables are used in current prediction models (using linear regression with the naïve eGFR slope, estimated using least squares, as the dependent variable). We found that with two CpG sites, cg25799291 and cg22253401, methylation levels can substantially improve the model fit: the proportion of variance in eGFR slope explained by the model, measured by the R2, improved from 23.1% in the model that only included baseline eGFR and ACR to 42.2% in the model that also included cg25799291 and cg22253401 (Table 4). The average prediction error (root mean square error) improved by 12.5%. On the other hand, including randomly selected loci that showed no significant association with GFR decline did not improve the prediction model. When prediction was done via a split-sample analysis to reduce “overfitting”, the R2 was still substantially improved at 35.9% of variance and average prediction error was improved by 7.5%. Furthermore, a risk score constructed of methylation levels at these two CpG sites was predictive of development of ESRD controlled for age, sex, duration of diabetes, baseline eGFR, ACR and cell type heterogeneity (odds ratio=1.44, P=0.019). The C-statistic, a measure of classification accuracy, was 0.694 for the model that included methylation score versus 0.664 for the model that included all variables except methylation score

Table 4.

Methylation levels at cg25799291 and cg22253401 can improve prediction models of eGFR slope, compared with standard clinical predctors and 5 other randomly selected CpG loci.

| Model | AIC | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Root Mean Square Error* | Model P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFR+log(ACR) | 406.58 | 0.2311 | 0.2174 | 5.783 | 4.06 × 10−7 |

| GFR+log(ACR)+cg25799291 | 395.39 | 0.3144 | 0.3020 | 5.485 | 3.87 × 10−9 |

| GFR+log(ACR)+cg22253401 | 388.95 | 0.3517 | 0.3401 | 5.333 | 1.82 × 10−10 |

| GFR+log(ACR)+cg27451230 | 408.53 | 0.2314 | 0.2176 | 5.807 | 1.89 × 10−6 |

| GFR+log(ACR)+cg23672176 | 408.43 | 0.2321 | 0.2182 | 5.805 | 1.81 × 10−6 |

| GFR+log(ACR)+cg13859847 | 408.14 | 0.2340 | 0.2202 | 5.797 | 1.58 × 10−6 |

| GFR+log(ACR)+cg05525106 | 408.31 | 0.2329 | 0.2191 | 5.802 | 1.71 × 10−6 |

| GFR+log(ACR)+cg25749165 | 408.43 | 0.2321 | 0.2182 | 5.805 | 1.81 × 10−6 |

| GFR+log(ACR)+cg25799291+cg22253401† | 377.75 | 0.4220 | 0.4115 | 5.059 | 1.94 × 10−12 |

Outcome is “naïve” (least-squares) slope of eGFR

Average prediction error in ml/min/1.73m2/year

Final model is: eGFR slope= 43.88 – 0.0450*eGFR – 2.112*log(ACR) −2.765*cg25799291 – 3.863*cg22253401

Analysis of consistency of association with methylation levels across cohorts

To determine whether associations between methylation levels and eGFR slope replicate across different groups of individuals, we also analyzed methylation levels in a case control study derived from individuals with chronic kidney disease at baseline in the CRIC,24 consisting of those whose kidney disease progressed rapidly (mean eGFR slope=−5.1 ml/min/1.73 m2/yr, n=20) and those whose kidney disease was stable (mean eGFR slope=2.2 ml/min/1.73 m2/yr, n=20). In this cohort methylation in baseline peripheral blood was also measured using the Infinium HumanMethylation450 Beadchip. After correction for multiple comparisons, none of the 77 probes was significantly associated with eGFR slope (Table S6). However, hypermethylation at cg22253401, which was a major component of the Pima prediction score at which hypermethylation predicted ESRD (odds ratio=1.41, P=0.010), was also associated with increased risk of rapid progression in CRIC at P<0.05 (Table 5). These findings suggest that some of the probes which predict eGFR slope in Pimas with chronic kidney disease (particularly cg22253401) may also predict renal function decline in other populations with chronic renal insufficiency.

Table 5.

Association of top 20 probes associated with slope of eGFR in Pimas with progression of kidney disease in CRIC

| Probe Name | chr | Position | RefGene Name | Pima Partial R | CRIC Effect Size | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg20677142 | 3 | 119012899 | CDGAP | −0.59 | −1.693 | 0.1974 |

| cg17794358 | 6 | 32097257 | ATF6B;FKBPL | −0.54 | −0.134 | 0.8516 |

| cg09616494 | 4 | 36333625 | DTHD1 | −0.54 | −0.338 | 0.7853 |

| cg25799291 | 2 | 55685277 | — | −0.53 | 4.543 | 0.0302 |

| cg01295785 | 18 | 12437948 | — | −0.52 | 1.839 | 0.1329 |

| cg14530304 | 17 | 77777792 | — | −0.52 | −1.712 | 0.3579 |

| cg11341657 | 6 | 107811567 | SOBP | −0.52 | −0.244 | 0.3380 |

| cg10553596 | 2 | 242751847 | NEU4 | 0.51 | 0.222 | 0.8092 |

| cg07923233 | 1 | 76080727 | — | −0.51 | 0.133 | 0.4875 |

| cg06985721 | 1 | 55464653 | BSND | 0.51 | 0.259 | 0.8145 |

| cg16690037 | 16 | 4377663 | — | −0.51 | 0.077 | 0.9586 |

| ch.12.123150169F | 12 | 124584216 | — | −0.51 | 0.069 | 0.8631 |

| cg25655234 | 4 | 7194841 | SORCS2 | −0.50 | −1.450 | 0.1500 |

| cg12670963 | 5 | 1511422 | LPCAT1 | 0.50 | −1.773 | 0.1453 |

| cg11073121 | 2 | 37039119 | VIT | 0.50 | 1.630 | 0.1173 |

| cg15427520 | 11 | 35252384 | CD44 | −0.50 | −0.541 | 0.3912 |

| cg22253401 | 4 | 162369223 | FSTL5 | −0.49 | −3.281 | 0.0396 |

| cg27164771 | 11 | 19138675 | ZDHHC13 | −0.49 | −2.494 | 0.1968 |

| cg02444484 | 10 | 95372040 | PDE6C | 0.49 | −1.892 | 0.0767 |

| cg10213328 | 17 | 37309414 | — | −0.49 | −0.821 | 0.4936 |

Pima partial R is the correlation between methylation and slope of eGFR in Pimas with chronic renal disease at baseline, CRIC effect size is logarithm of the odds per unit M for being in the stable kidney function group relative to the rapid progression group. P-values < 0.05 for association with consistent direction in Pimas and in CRIC are indicated by bold.

DISCUSSION

Studies in cellular and animal models have suggested that epigenetic factors play a role in development of diabetic kidney disease.17–19 A role for cytosine methylation in diabetic kidney disease is also suggested by studies in kidney tissue and peripheral blood in humans with diabetes.16,21 However most studies of DNA methylation and diabetic nephropathy have had been small and cross-sectional,22,23 and specific CpG sites at which methylation associates with risk of diabetic kidney disease have not been identified. In the present study we have examined the association of methylation levels at CpG sites, measured in peripheral blood in 181 Pima Indians, with measures of diabetic kidney disease both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. We found that, after accounting for multiple statistical comparisons, cytosine methylation at 77 different CpG sites significantly predicts decline in renal function, observed over an average of 6 years. One key limitation of most previous studies of methylation and diabetic kidney disease is that they have been cross-sectional, and, thus, cannot distinguish whether observed methylation differences are the cause or consequence of kidney disease. As the present findings are based on longitudinal analyses, with methylation measured before progression of kidney disease, they indicate that cytosine methylation may play a role in development of diabetic kidney disease.

The site with the strongest association with subsequent eGFR decline was near CDGAP (also known as ARHGAP31), which codes for Rho GTPase Activating Protein 31. This gene is expressed across a wide range of tissues, including kidney, and mutations in ARHGAP31 cause Adams-Olivier Syndrome, which is characterized by aplasia cutis congenita of the scalp and terminal transverse limb defects, and which is occasionally associated with renal abnormalities, such as hydronephrosis and small kidneys.32 Hypomethylation at this site (cg20677142) in visceral adipose tissue is also associated with insulin resistance.33 Studies in ARHGAP31-deficient mice and cultured endothelial cells suggest that this protein is an important regulator of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-mediated angiogenesis.34 Given our findings, and the importance of VEGF in diabetic nephropathy and other diabetic complications,35 ARHGAP31 is a strong candidate as an epigenetic mediator of risk of diabetic nephropathy. One of the other CpG sites associated with subsequent decline in eGFR was between FKBPL and ATF6B. FKBPL is an important anticancer protein having intra- and extracellular roles in tumor and endothelial cells, with antiangiogenic effects mediated via the CD44 pathway.36,37 ATF6B is involved in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response.38 Both angiogenesis and altered endoplasmic reticulum stress response play plausible roles in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy, but further studies are needed to elucidate these roles.

In our analyses we controlled for estimates of the cellular composition of peripheral blood leukocytes, derived from methylation profiles. Since cellular heterogeneity is potentially a powerful confounder of the association between DNA methylation and traits, this approach is customary in epigenetic association studies. However, in some situations cellular heterogeneity may reflect the role of a mediator of association, rather than a confounder (e.g. if inflammatory mechanisms are responsible for risk). We also conducted analyses without adjustment for cell type, and found similar results with the ARHGAP31 and FKBPL/ATF6B probes still among the most strongly associated sites. The functional significance of both the ARHGAP31 (cg20677142) and FKBPL/ATF6B (cg17794358) is supported by annotation, which indicates that both are located in regulatory regions in ENCODE cell lines. Furthermore, kidney-specific ChIP-Seq data show enrichment for histone modifications (H3K4me1 and H3K4me3) typically associated with regulatory elements; this suggests that these differentially methylated CpG sites act on regulatory elements in the human kidney, and that they might show differential methylation across different cell types.

The genes identified as differentially methylated in the current study did not replicate any of those identified in previous epigenome-wide association studies of diabetic nephropathy.22,23 The previous studies were mostly conducted in European populations and were largely cross-sectional in nature. In the present study, we have conducted both longitudinal and cross-sectional analyses. The top signals identified as associated with eGFR in our cross-sectional analyses do not generally overlap with those identified as associated with eGFR decline in our longitudinal analyses in the same individuals. This suggests that epigenetic variations associated with eGFR cross-sectionally (which are perhaps more likely to be secondary to renal disease) may be different from those that are associated longitudinally with eGFR changes (which are perhaps more likely to reflect determinants of renal disease). This observation is consistent with the findings that eGFR is a reasonable, but imperfect, predictor of renal function decline. Nonetheless, in our pathway analyses the top signals identified by both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses were reflective of apoptosis and mitochondrial function. Thus, the epigenetic cross-sectional correlates and longitudinal predictors of eGFR may be reflecting these biological processes, even if the specific sites involved are different.

It is likely that there are multiple sites at which epigenetic modification contributes to risk of diabetic nephropathy. Although, to our knowledge, this study is the largest genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation and diabetic nephropathy to date, larger studies will be required to detect sites with more modest effects. The lack of power for modest effect sizes, particularly for the dichotomous outcome, is probably the reason why none of the individual sites were statistically significantly associated with subsequent ESRD after correction for multiple comparisons. With the increased power for analysis of the continuous outcome eGFR slope, we identified 77 CpG sites associated with eGFR slope after correction for multiple comparisons. Pathway analyses suggested that sites associated with eGFR tended to be in genes influencing apoptosis and mitochondrial function. This suggests that epigenetic modification of these pathways contributes to risk of progression of diabetic kidney disease- this is consistent with other evidence that suggests that these pathways are involved development of diabetic nephropathy.39–41

The potential functionality of the methylation sites we identify is further supported by the fact that methylation levels at some of these sites also associated with fibrosis in kidney tissue. For 5 of the 77 sites at which methylation level measured in peripheral blood was associated with eGFR slope in the Pima Indians, methylation levels measured in the kidney in a different cohort of diabetic individuals was associated with level of fibrosis (at 3 of the 5 statistical significance was retained after correction for multiple comparisons, and the direction of association with the kidney disease was the same in both groups). Given that fibrosis is a major determinant of declining renal function,42 these results suggest that epigenetic modification at these sites has functional effects in diabetic kidneys. For clinical predictive purposes, cytosine methylation levels are optimally measured in readily accessible tissues, such as peripheral blood, as in the present study. However, one might expect cytosine methylation measured in kidney tissue to be more closely related to the pathogenesis of nephropathy. The present findings suggest that at least some of the epigenetic variations identified in peripheral blood as associated with progressive kidney disease are reflective of processes in kidney tissue.

Through multivariate modeling of future eGFR decline, we found that a model that included methylation levels at two CpG sites, cg25799291 and cg22253401, contributed significantly to the prediction of the eGFR slope beyond standard clinical variables. Although for the epigenome-wide analyses we report results for the BLUP estimates of eGFR slope, which are more robust, for these analyses we used the “naïve” (least squares) slope, as this is perhaps more relevant to the clinical situation. (The two slope estimates are highly correlated, r=0.89, but do give somewhat different results. See Table S7 for the top 20 sites for naïve slope.) A model containing only the standard prediction variables of baseline eGFR and ACR accounted for 23.1% of the variance in eGFR slope, while a model including these two sites accounted for an additional 12.8% of the variance when a split-sample validation procedure was used to reduce overfitting. Furthermore, each standard deviation of a risk score derived from these two sites was associated with a 46% increase in risk of ESRD. Cg25799291 is not located in a known regulatory region for any gene- it is in a CpG island on chromosome 20, 58 kb away from BMP7, the nearest gene. The region is enriched for epigenetic regulatory elements H3K4me1 and H3K4me3 in several ENCODE cell lines (UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway, accessed March 17, 2017). Cg2253401 is located in an intron of FSTL5; the function of this gene is not well-characterized but it is involved in cell proliferation.43 While the functional characteristics of these two sites are not clear, our results suggest that they may provide useful biomarkers for risk of progression of diabetic nephropathy. Levels of mRNA expression measured in peripheral blood may also provide useful biomarkers, and direct comparisons are required to assess the predictive value of gene expression versus DNA methylation measures. The present study cannot make this comparison since mRNA was not collected. Nonetheless, in the present analyses the association with methylation levels at cg22253401 is of particular interest, since this probe was also significantly associated with progression of renal disease in CRIC. [The probe was not significantly associated eGFR slope in an additional 318 Pimas who did not have advanced kidney disease at baseline (data not shown).] These findings suggest that methylation patterns (particularly cg22253401) can predict progression of kidney disease in individuals with advanced kidney disease. Since DNA methylation is relatively easy to measure in peripheral blood samples, this could potentially be a useful tool for clinical management of diabetic kidney disease. Due to its relatively small sample size, the CRIC sample analyzed here has limited power to assess replication. Ultimately, confirmation of the present results in additional cohorts is required to firmly establish methylation at these sites as predictors of progression of diabetic kidney disease.

In summary, the present study identified 77 CpG sites strongly associated with progression of diabetic kidney disease among individuals with chronic kidney disease at baseline. These findings have implications for the pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease-suggesting that epigenetic modification of pathways affecting apoptosis and renal fibrosis are important contributors to the disease. Although further confirmation in additional cohorts is required to establish predictive utility of methylation measures for kidney disease, the present results also suggest that DNA methylation measured in peripheral blood cells may provide a useful, easily measured, biomarker for assessing risk of diabetic nephropathy.

METHODS

Data and Measurements

Data were derived from a longitudinal study in a rural community where most residents are Pima Indians.25 In this study, community residents who were ≥ 5 years old were invited to a health examination every two years. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and all participants gave informed consent. The examination included a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test, and diabetes was diagnosed according to 1997 American Diabetes Association criteria:44 i.e., fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l (126 mg/dl), two-hour post-load plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/l (200 mg/dl) or a diagnosis made in the course of routine clinical care. Serum and urine creatinine were measured by a modified Jaffe method.45 Since 1982, urinary albumin concentration was measured by nephelometric immunoassay, and urinary albumin excretion was estimated with the albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR). EGFR was calculated from serum creatinine using the CKD-EPI formula for non-black race.46 Hemoglobin A1c was measured by high performance liquid chromatography (BioRad MDMS until 2000 and Tosoh A1c 2.2 Plus thereafter). Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured at the 1st and 4th Korotkoff sounds respectively and mean blood pressure was calculated as [(2*diastolic+systolic)/3].

End-Stage Renal Disease

Surveillance for ESRD and for mortality has been conducted independently of the research studies.26,47 ESRD, which was defined as the need for dialysis or kidney transplantation or as a death from kidney failure if dialysis was unavailable or refused, was ascertained through surveillance of dialysis units serving the community, by reports from participants, by review of medical records and from a registry maintained by the Office of Public Health Nursing. Deaths were also ascertained and available records were reviewed to determine cause of death as previously described.47 Date of ESRD was taken as date of initiation of dialysis or date of death from diabetic nephropathy.

Participants

For the present analyses, we focused on development of ESRD in diabetic individuals with advanced chronic kidney disease. Thus, we selected DNA from the first examination in individuals with diabetes who did not have ESRD but who had chronic kidney disease (defined as ACR≥ 300 mg/g or eGFR< 60 ml/min, based on a single measure observed in the epidemiologic study). This is subsequently called the “baseline” examination. In the longitudinal study 355 individuals with DNA samples were available who met these criteria, and 90 of these developed ESRD during a mean follow-up of 5.1 years. We used a nested case-control design27–29 to select matching controls for each case for methylation studies. Cases and controls were matched for sex and duration of diabetes (in 5-year categories). We used a “risk set sampling” procedure29 to select controls from among individuals who were at risk for disease but had not yet developed it at the follow-up time at which each case developed ESRD (i.e., controls were selected from among those who had been followed at least as long as the case and who had not developed ESRD). Up to 4 controls were selected for each case, if available. This strategy efficiently captures the information from the full longitudinal cohort without the need to assay the entire cohort-all cases are selected, as are a matched sample of controls who would contribute person-time to an incidence calculation.29,48 With this design, the odds ratio associated with each exposure variable (e.g. the methylation level) represents an unbiased estimate of the hazard ratio obtained in longitudinal study of the full cohort;49,50 it is noteworthy that the same control can be matched to multiple cases and a control for a given case can subsequently become a case themselves. Of the 90 cases who developed ESRD, 8 did not have sufficient DNA available for methylation studies, and 2 were excluded after quality control procedures (see below). Thus, final analyses were based on 80 cases and 327 matched controls, constituting a total of 181 individuals (80 ESRD cases and 101 who did not develop ESRD and who were only included as controls) Among cases, 42% had eGFR<60 ml/min/1.73m2 and ACR≥300 mg/g at baseline, 55% had eGFR≥60 ml/min/1.73m2 and ACR≥ 300mg/g, while 3% had eGFR<60 ml/min/1.73m2 and ACR<300 mg/g.

DNA Methylation Assays

DNA methylation was measured using the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 Beadchip which measures methylation at ~485,000 CpG sites across the genome (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Methylation results generated on this array have previously been validated by bisulfite sequencing and pyrosequeincing.51,52 DNA was extracted from nuclear pellets derived from peripheral blood leukocytes, and was analyzed on the array both with bisulfite treatment and without bisulfite treatment. Most pre-process and quality control steps were conducted using the Minfi package.53 First, we excluded 65 SNP probes and 850 control probes. The raw signal intensities generated from the array were corrected for background intensity. Probes with a p-value for detection >0.01 in any sample were removed, as were those that map to the sex chromosome or that cross-hybridize to multiple genomic locations.54 We further removed probes targeting single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and probes that contain a SNP within the probe or within 1 base pair of the probe (minor allele frequency >0.01 according to dbSNP137). Thus, a total of 397,063 probes were analyzed. We excluded 2 subjects that were not within ±3 s.d. from the mean of a principal component for PC1, PC2 and PC3 based on principal component analysis (PCA), which was performed using a random selection of 50,000 autosomal probes. These 2 samples also showed quality problems. The proportion of methylation at each CpG site was taken as the beta value, which was calculated from the intensities of the methylated (m) and unmethylated (u) probes [beta=m/(m+u+100)]; the constant 100 regularizes beta-values when both m and u values are small.55 Beta-mixture quantile (BMIQ) normalization56 was performed by the RnBeads package to adjust for type 2 bias in the Infinium 450K platform. Additionally, the bisulfite conversion efficiency was estimated by the bisulfite conversion control probes, based on Illumina guidelines. Annotation data were taken from IlluminaHumanMethylation450kanno.ilmn12.hg19 in Bioconductor.

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons of baseline characteristics between groups were made by the t-test for continuous variables and by Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous variables. Multiple linear regression was used to assess the relationship between methylation and eGFR or other continuous measures of kidney function (ACR, serum creatinine) at baseline. In these analyses, beta was transformed to M (M=log2[beta/(1-beta)]),57 and M was taken as the dependent variable while eGFR (or other renal function trait) was an independent variable; covariates included age, sex, duration of diabetes, mean blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, batch and conversion efficiency. Measures of the type of cells constituting the peripheral blood leukocytes were not made during the longitudinal study. To address potential confounding of results by cell type, the method of Houseman et al58 was used to estimate the distribution of cell types from DNA methylation patterns. This method uses methylation data from ~100 probes to predict the cell type distribution, derived from a reference sample with known cell type distributions, and it has been validated across several different settings.58,59 The cell-type estimates derived from this method were used as additional covariates. Estimates of the cell type proportions in cases and controls are shown in Table S8.

Conditional logistic regression, accounting for the matched case-control design, was used to assess the relationship between methylation (M) at each probe and risk of ESRD; covariates included age, duration of diabetes, mean blood pressure, HbA1c, batch, cell type and conversion efficiency. The C-statistic, which is analogous to the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, was calculated for conditional logistic models accounting for the matched design.60 To improve power to predict progression of kidney disease, association of methylation with eGFR slope, calculated from the baseline examination across all subsequent examinations, was also analyzed. For these longitudinal data, we used a linear mixed effects model and calculated BLUP (Best Linear Unbiased Predictor) estimates31 of intercepts and slopes for each individual (without covariates). Subsequently we used weighted linear regression, with the BLUP estimates of slope as the dependent variable and the inverse of the variances of the BLUP estimates as weights, to analyze association of methylation at CpG sites with subsequent progression.61 The model was adjusted for age, sex duration, hba1c, mean blood pressure, batch, cell type and conversion efficiency; we did not control for baseline eGFR as this is incorporated into the intercept of the mixed model. BLUP methods use a similar approach to that of a repeated measures mixed model (e.g. hierarchical linear model), but provide an efficient and easily interpretable alternative method of estimation to a full likelihood calculation. When the top probes identified using the BLUP approach were analyzed in a full repeated measures model, similar results were obtained. To account for the multiple comparisons involved in analysis of a large number of CpG sites the false discovery rate (FDR) procedure was used;62 thus, FDR<0.05 was taken as genome-wide statistical significance.

To develop sets of probes that might be useful for clinical prediction, we selected combinations of probes from among the top 20 sites identified as individually associated with eGFR slope using a forward stepwise procedure, and we analyzed their combined association with eGFR slope controlled for baseline eGFR and ACR, which are standard clinical predictors. For these analyses, we used the “naïve” (least-squares) estimate of the eGFR slope, rather than the BLUP estimate, as the dependent variable; since the BLUP estimates use information from across the entire sample, the naïve slope may be more relevant to the individual clinical situation. Least squares methods were used to calculate the average prediction error (root mean square error), and proportion of variance (R2) explained by the model. Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) was also calculated as a measure of model fit (lower values indicate a better fitting model).63 After selection of the markers, we used a split-sample validation procedure to reduce “overfitting” bias that occurs when and individual’s data are used to develop a prediction equation for their own values. The total sample was randomly divided into two parts, and the regression equation was fit separately in each sample. The model fit statistics were then recalculated using the parameter estimates for each sample that were obtained in the other half of the data. In addition, we also calculated a methylation risk score from the CpG sites included in the final model. This score was calculated as Σ−βiMi, where β is the regression coefficient associated with the ith site and M is its methylation level. The extent to which this score predicted development of ESRD was assessed by conditional logistic regression.

Network Analyses

Based on annotation data provided by IlluminaHumanMethylation450kanno.ilmn12.-hg19 in Bioconductor where promoters were determined from regulatory features in the UCSC Genome Browser and from Illumina (see https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/annotation/html/IlluminaHumanMethylation450kanno.ilmn12.hg19.html), CpG sites were mapped into promoter regions of 28376 genes, each of which contained 3 CpG sites on average. The average beta values of CpG sites within each promoter region were calculated to represent the promoter-methylation levels for each gene. A weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) was conducted on this methylation matrix to identify function specific gene modules, based on shared methylation patterns, that are correlated with renal function traits.30

Human Kidney Tissue Studies

DNA methylation studies had also been performed in human kidney tissue, as previously described.21 In brief, human kidney tissue was collected from the unaffected portion of cancer nephrectomies. Clinical information was collected at the time of nephrectomy using an honest broker system. Histopathological analysis (including degree of tubulointerstitial fibrosis) was performed by an expert renal pathologist. Only control samples and samples with hypertension, diabetes and kidney disease were included. Samples from individuals with significant hematuria or other signs of glomerulonephritis (HIV, hepatitis, or lupus) were excluded, as was one sample without clinical data. The diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease was made based on histopathological changes. DNA was extracted from 94 microdissected human kidney tubule epithelial samples. Genomic DNA (200 ng) was purified using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified DNA quality and concentration were assessed with NanoDrop ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and by Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA Assay Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) prior to bisulfite conversion.

DNA methylation was measured using the Infinium HumanMethylation450 Beadchip (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Quality control, data processing and normalization for the kidney data were performed the same way as for the blood samples. Linear regression analyses were conducted across 91 individuals, with M as the dependent variable, percentage fibrosis as an independent variable, and age, gender, race, diabetes category, hypertension category, batch and conversion efficiency as covariates.

Analysis of consistency of association with methylation levels across cohorts

To determine whether associations between methylation levels and eGFR slope in Pimas with chronic kidney disease replicate across different groups of individuals, we also analyzed methylation levels in a case-control study derived from individuals with chronic kidney disease at baseline in the CRIC, consisting of those whose kidney disease progressed rapidly, and those whose kidney disease was stable. Methylation in baseline peripheral blood was also measured using the Infinium HumanMethylation450 Beadchip. The CRIC samples constituted a case-control study in which 20 rapid progressors (most negative eGFR slope) were selected from among 3919 CRIC participants.24 These were compared with 20 individuals with stable kidney disease (positive eGFR slope) matched for sex, race and underlying disease. Mean baseline age was 54 (±15) years in rapid progressors and 55 (±8) years in those with stable kidney disease. In both groups 60% of individuals were women and 50% had diabetes. Mean baseline eGFR was 41 (±11) ml/min/1.73m2 in rapid progressors and 52 (±10) ml/min/1.73m2 in those with stable kidney disease. Association between progression of kidney disease and methylation was analyzed with a logistic regression model with M-value as the predictor variable and progression group (stable kidney disease versus rapid progression) as the outcome, with control for sex, race and diabetes status (the same covariates used in Wing et al).24

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support:

This work was supported in part by a grant from the American Diabetes Association (1-12-DNP-01), in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and in part by NIH DP3 DK1082220 and R01 DK087635 (to the Susztak lab).

The authors thank the participants who volunteered for the study and the staff of the Phoenix Epidemiology and Clinical Research Branch who provided assistance This work was presented in part at the annual meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics, Baltimore, MD, October 6–10, 2015.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no icompeting financial interests to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Saran R, Li Y, Robinson B, et al. Us Renal Data System 2015 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(3 Suppl 1):Svii, S1–305. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas MC, Cooper ME, Zimmet P. Changing Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Associated Chronic Kidney Disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(2):73–81. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson RG, Pettitt DJ, Carraher MJ, Baird HR, Knowler WC. Effect of Proteinuria on Mortality in Niddm. Diabetes. 1988;37(11):1499–1504. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.11.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The Effect of Intensive Treatment of Diabetes on the Development and Progression of Long-Term Complications in Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uk Prospective Diabetes Study (Ukpds) Group. Intensive Blood-Glucose Control with Sulphonylureas or Insulin Compared with Conventional Treatment and Risk of Complications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (Ukpds 33) Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al. Effects of Losartan on Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):861–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al. Renoprotective Effect of the Angiotensin-Receptor Antagonist Irbesartan in Patients with Nephropathy Due to Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):851–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imperatore G, Knowler WC, Pettitt DJ, Kobes S, Bennett PH, Hanson RL. Segregation Analysis of Diabetic Nephropathy in Pima Indians. Diabetes. 2000;49(6):1049–1056. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.6.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman BI, Tuttle AB, Spray BJ. Familial Predisposition to Nephropathy in African-Americans with Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25(5):710–713. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90546-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seaquist ER, Goetz FC, Rich S, Barbosa J. Familial Clustering of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Evidence for Genetic Susceptibility to Diabetic Nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(18):1161–1165. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905043201801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iyengar SK, Sedor JR, Freedman BI, et al. Genome-Wide Association and Trans-Ethnic Meta-Analysis for Advanced Diabetic Kidney Disease: Family Investigation of Nephropathy and Diabetes (Find) PLoS Genet. 2015;11(8):e1005352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandholm N, Salem RM, McKnight AJ, et al. New Susceptibility Loci Associated with Kidney Disease in Type 1 Diabetes. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(9):e1002921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ek WE, Rask-Andersen M, Johansson A. The Role of DNA Methylation in the Pathogenesis of Disease: What Can Epigenome-Wide Association Studies Tell? Epigenomics. 2016;8(1):5–7. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cortijo S, Wardenaar R, Colomé-Tatché M, et al. Mapping the Epigenetic Basis of Complex Traits. Science. 2014;343(6175):1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.1248127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Susztak K. Understanding the Epigenetic Syntax for the Genetic Alphabet in the Kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(1):10–17. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Z, Miao F, Paterson AD, et al. Epigenomic Profiling Reveals an Association between Persistence of DNA Methylation and Metabolic Memory in the Dcct/Edic Type 1 Diabetes Cohort. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(21):E3002–3011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603712113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brennan EP, Ehrich M, O’Donovan H, et al. DNA Methylation Profiling in Cell Models of Diabetic Nephropathy. Epigenetics. 2010;5(5):396–401. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.5.12077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villeneuve LM, Natarajan R. The Role of Epigenetics in the Pathology of Diabetic Complications. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299(1):F14–25. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00200.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villeneuve LM, Reddy MA, Lanting LL, Wang M, Meng L, Natarajan R. Epigenetic Histone H3 Lysine 9 Methylation in Metabolic Memory and Inflammatory Phenotype of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(26):9047–9052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803623105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sayyed SG, Gaikwad AB, Lichtnekert J, et al. Progressive Glomerulosclerosis in Type 2 Diabetes Is Associated with Renal Histone H3k9 and H3k23 Acetylation, H3k4 Dimethylation and Phosphorylation at Serine 10. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(6):1811–1817. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko YA, Mohtat D, Suzuki M, et al. Cytosine Methylation Changes in Enhancer Regions of Core Pro-Fibrotic Genes Characterize Kidney Fibrosis Development. Genome Biol. 2013;14(10):R108. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sapienza C, Lee J, Powell J, et al. DNA Methylation Profiling Identifies Epigenetic Differences between Diabetes Patients with Esrd and Diabetes Patients without Nephropathy. Epigenetics. 2011;6(1):20–28. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.1.13362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell CG, Teschendorff AE, Rakyan VK, Maxwell AP, Beck S, Savage DA. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis for Diabetic Nephropathy in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. BMC Med Genomics. 2010;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wing MR, Devaney JM, Joffe MM, et al. DNA Methylation Profile Associated with Rapid Decline in Kidney Function: Findings from the Cric Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(4):864–872. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knowler WC, Bennett PH, Hamman RF, Miller M. Diabetes Incidence and Prevalence in Pima Indians: A 19-Fold Greater Incidence Than in Rochester, Minnesota. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108(6):497–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson RG, Newman JM, Knowler WC, et al. Incidence of End-Stage Renal Disease in Type 2 (Non-Insulin-Dependent) Diabetes Mellitus in Pima Indians. Diabetologia. 1988;31(10):730–736. doi: 10.1007/BF00274774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research: Volume I-the Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research: Volume Ii- the Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langholz B, Goldstein L. Risk Set Sampling in Epidemiologic Cohort Studies. Statist Sci. 1996:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langfelder P, Horvath S. Wgcna: An R Package for Weighted Correlation Network Analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson GK. That Blup Is a Good Thing: The Estimation of Random Effects. Statist Sci. 1991:15–32. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lehman A, Wuyts W, Patel MS. Adams-Oliver Syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. Genereviews(R) Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arner P, Sahlqvist A-S, Sinha I, et al. The Epigenetic Signature of Systemic Insulin Resistance in Obese Women. Diabetologia. 2016;59(11):2393–2405. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4074-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caron C, DeGeer J, Fournier P, et al. Cdgap/Arhgap31, a Cdc42/Rac1 Gtpase Regulator, Is Critical for Vascular Development and Vegf-Mediated Angiogenesis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27485. doi: 10.1038/srep27485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carranza K, Veron D, Cercado A, et al. Cellular and Molecular Aspects of Diabetic Nephropathy; the Role of Vegf-A. Nefrología (English Edition) 2015;35(2):131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.nefro.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valentine A, O’Rourke M, Yakkundi A, et al. Fkbpl and Peptide Derivatives: Novel Biological Agents That Inhibit Angiogenesis by a Cd44-Dependent Mechanism. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(5):1044–1056. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKeen HD, Brennan DJ, Hegarty S, et al. The Emerging Role of Fk506-Binding Proteins as Cancer Biomarkers: A Focus on Fkbpl. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39(2):663–668. doi: 10.1042/BST0390663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thuerauf DJ, Morrison L, Glembotski CC. Opposing Roles for Atf6alpha and Atf6beta in Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response Gene Induction. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(20):21078–21084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang HM, Ahn SH, Choi P, et al. Defective Fatty Acid Oxidation in Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells Has a Key Role in Kidney Fibrosis Development. Nat Med. 2015;21(1):37–46. doi: 10.1038/nm.3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breyer MD, Susztak K. The Next Generation of Therapeutics for Chronic Kidney Disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(8):568–588. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma K, Karl B, Mathew AV, et al. Metabolomics Reveals Signature of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Diabetic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(11):1901–1912. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013020126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Efstratiadis G, Divani M, Katsioulis E, Vergoulas G. Renal Fibrosis. Hippokratia. 2009;13(4):224–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang D, Ma X, Sun W, Cui P, Lu Z. Down-Regulated Fstl5 Promotes Cell Proliferation and Survival by Affecting Wnt/Beta-Catenin Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(3):3386–3394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.American Diabetes Association Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(7):1183–1197. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chasson AL, Grady HJ, Stanley MA. Determination of Creatinine by Means of Automatic Chemical Analysis. Tech Bull Regist Med Technol. 1960;30:207–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A New Equation to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sievers ML, Nelson RG, Bennett PH. Adverse Mortality Experience of a Southwestern American Indian Community: Overall Death Rates and Underlying Causes of Death in Pima Indians. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(11):1231–1242. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90024-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Breslow NE, Patton J. Case-Control Analysis of Cohort Studies. In: Breslow NE, Whittemore AS, editors. Energy and Health. Philadelphia: SIAM Institute for Mathematics and Society; 1979. pp. 226–242. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prentice RL, Breslow NE. Retrospective Studies and Failure Time Models. Biometrika. 1978;65(1):153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prentice RL, Pyke R. Logistic Disease Incidence Models and Case-Control Studies. Biometrika. 1979;66(3):403–411. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bibikova M, Barnes B, Tsan C, et al. High Density DNA Methylation Array with Single Cpg Site Resolution. Genomics. 2011;98(4):288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roessler J, Ammerpohl O, Gutwein J, et al. Quantitative Cross-Validation and Content Analysis of the 450k DNA Methylation Array from Illumina, Inc. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:210. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, et al. Minfi: A Flexible and Comprehensive Bioconductor Package for the Analysis of Infinium DNA Methylation Microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(10):1363–1369. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Jager PL, Srivastava G, Lunnon K, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease: Early Alterations in Brain DNA Methylation at Ank1, Bin1, Rhbdf2 and Other Loci. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(9):1156–1163. doi: 10.1038/nn.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bibikova M, Lin Z, Zhou L, et al. High-Throughput DNA Methylation Profiling Using Universal Bead Arrays. Genome Res. 2006;16(3):383–393. doi: 10.1101/gr.4410706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teschendorff AE, Marabita F, Lechner M, et al. A Beta-Mixture Quantile Normalization Method for Correcting Probe Design Bias in Illumina Infinium 450 K DNA Methylation Data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(2):189–196. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Irizarry RA, Ladd-Acosta C, Carvalho B, et al. Comprehensive High-Throughput Arrays for Relative Methylation (Charm) Genome Res. 2008;18(5):780–790. doi: 10.1101/gr.7301508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Houseman EA, Accomando WP, Koestler DC, et al. DNA Methylation Arrays as Surrogate Measures of Cell Mixture Distribution. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koestler DC, Christensen B, Karagas MR, et al. Blood-Based Profiles of DNA Methylation Predict the Underlying Distribution of Cell Types: A Validation Analysis. Epigenetics. 2013;8(8):816–826. doi: 10.4161/epi.25430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brentnall AR, Cuzick J, Field J, Duffy SW. A Concordance Index for Matched Case-Control Studies with Applications in Cancer Risk. Stat Med. 2015;34(3):396–405. doi: 10.1002/sim.6335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Montgomery DC, Peck EA, Vining GG. Introduction to Linear Regression Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc Series B. 1995;57(1):12. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Multimodel Inference. Sociological Methods & Research. 2004;33(2):261–304. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.