Abstract

Advances in genomics and metabolomics have made clear in recent years that microbial biosynthetic capacities on Earth far exceed previous expectations. This is attributable, in part, to the realization that most microbial natural product (NP) producers harbor biosynthetic machineries not readily amenable to classical laboratory fermentation conditions. Such “cryptic” or dormant biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) encode for a vast assortment of potentially new antibiotics and, as such, have become extremely attractive targets for activation under controlled laboratory conditions. We report here that co-culturing of a Rhodococcus sp. and a Micromonospora sp. affords keyicin, a new and otherwise unattainable bis-nitroglycosylated anthracycline whose mechanism of action (MOA) appears to deviate from those of other anthracyclines. The structure of keyicin was elucidated using high resolution MS and NMR technologies, as well as detailed molecular modeling studies. Sequencing of the keyicin BGC (within the Micromonospora genome) enabled both structural and genomic comparisons to other anthracycline-producing systems informing efforts to characterize keyicin. The new NP was found to be selectively active against Gram-positive bacteria including both Rhodococcus sp. and Mycobacterium sp. E. coli-based chemical genomics studies revealed that keyicin’s MOA, in contrast to many other anthracyclines, does not invoke nucleic acid damage.

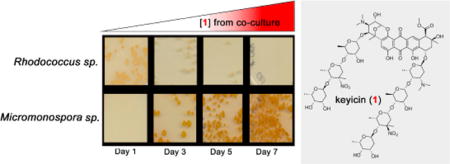

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

It is now widely recognized that humanity faces a host of burgeoning crises likely to impact global health in the foreseeable future. Principal among these has been the rise of drug resistant microbes set forth, in part, by a loss of interest in natural products (NPs) in the 70s through to the early 2000s across both academia and industry. This change in attitude was inspired by two critical thoughts at the time: i) the belief that NP structural diversity and microbial diversities had largely been exhausted, and ii) that a more efficient means of identifying drugs and drug leads lay in the prodigious application of combinatorial chemistry and high throughput screening (HTS) technologies. However, our view of drug discovery today is informed largely by technological advances and discoveries over the last 10–20 years that dramatically refute those early tenets and argue that natural products remain one of the greatest sources of molecular diversity applicable to treating human diseases.1 Revolutionary advances in genome sequencing, proteomics, metabolomics, and other methodologies have changed not only how we see the natural world but also how we can harness its intricacies. The rise of these technologies enabled by technical advances (e.g. those related to nucleic acid and/or protein sequencing and synthesis, mass spectrometry and other diagnostics) as well as dramatic increases in computational capabilities have brought about stunning revelations about microbial diversity and how this influences NP production.2-16 Microbes leverage NPs to interact with their biotic and abiotic environments and, as such, these metabolites have been selected through evolution for biological relevance, often serving as attractive new drug leads.17-19 Rational discovery strategies with multidisciplinary approaches can be employed to uncover these bioactive molecules at scale.

For over 80 years, culturable microorganisms formed the basis for NP drug discovery providing unique compounds with useful biological activities and medical uses.1, 20 Metagenomic studies of the last 10–15 years have shown, however, that the overwhelming majority of microorganisms (> 95%) on earth have either eluded interrogation for NP production, harbor NP biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) that remain silent under laboratory culturing conditions, or have been studied using technologies that, at the time, failed to meet the challenges of the day.21-23 It is believed that only 0.1-1% of the microorganisms on earth have been successfully cultured in the laboratory.23 At the same time it is now thought that earth harbors ~ 8.7 million eukaryotic species of which about 2.2 million are marine. Similarly, a lower bound of ~ 10000 prokaryotic species of which ~ 1300 are marine has been postulated.24 However, microbial diversity assessments employing cultivation-independent technologies suggest that these numbers are likely off by ~ 100 fold.25 For instance, work carried out in support of the International Census of Marine Microbes (ICoMM) initiative has shown that, on average, 1 L of seawater contains 108–109 bacteria representing ~ 20000 bacterial species.25

Especially with respect to prokaryotic species and lower eukaryotes, many of these organisms have proven rich sources of NPs (bacteria, fungi, plants, etc.). Yet it is clear that their molecular diversity, especially in light of what we are now learning about microbiomes and symbiotic relationships, remains dramatically underutilized.26 Genomics has revealed that the untapped microbial diversity available for drug and drug lead identification efforts far exceeds previous expectations.1, 22

Genome mining using biosynthetic signatures from established BGCs has proven to be an important tool in the search for new antimicrobial NPs which has inspired an explosion in BGC sequencing efforts and reported NP-encoding genomes.7, 15, 27-30 However, identifying new NPs on the basis of BGC mining remains a daunting task; i) one genome can house multiple, often dozens of BGCs (of the same, or different classes), ii) BGCs might be composed of elements distributed over multiple contigs and may contain genes for which no clear function exists thereby confounding gene-to-reaction correlations, iii) identified cryptic BGCs may fail to translate to detectable NPs, iv) many microorganisms are recalcitrant to necessary manipulations, and v) metagenomic library expression systems are often impractical.27 Hence, genomic approaches, although an excellent way to identify BGCs and their putative products, are, in the absence of other complementary technologies, insufficient to achieve broadly successful bioinformatics-guided NP identification goals for some biosynthetic classes.31, 32 However, when used in combination with proteomics and metabolomics, genomics becomes an increasingly powerful tool linking molecules with their biosynthetic genes. It is becoming increasingly evident that by triangulating genomic, proteomic and metabolomic information for microorganisms one becomes better able to address two key questions in current natural products chemistry: i) How does one identify interesting organisms when it comes to antimicrobial NP biosynthesis, and ii) How can cryptic BGCs be activated in an otherwise unproductive organism? Interdisciplinary approaches have vastly improved the ability to elucidate biosynthetic potentials; especially those that incorporate biological hypotheses in unveiling novel chemistry.33 Additionally, chemical genomics (CG) now enables one to rapidly gain insight into a NP’s mechanism of action further supporting the notion that biological insight hastens chemical discoveries and can drive chemical initiatives.34 Conclusively linking a BGC to a NP of interest via genome mining-based approaches remains a challenge. However, recent disclosures including the efforts detailed here, highlight that genomics, proteomics and metabolomics can be very effectively leveraged to identify novel producers of unique bioactive NPs.

We report herein the discovery of keyicin (1, Figure 1), a novel polynitroglycosylated anthracycline antibiotic, along with early efforts to understand its biosynthesis and mechanism/s of biological activity. An otherwise cryptic NP, keyicin production results from co-culturing of the producer Micromonospora strain with Rhodococcus. Only through the application and synergy of the technologies noted above was the identification and characterization of 1 possible. Closely related NPs have been identified before but never as the products of co-cultured microbes nor with zwitterionic nitroglycans appended to the aglycone core. Moreover, a great number of such keyicin-like agents have been shown to express biological activities through DNA-dependent means; results of chemical genomics suggest that keyicin functions in a unique manner that is independent of DNA damage processes. We postulate that keyicin is involved in microbial interactions between the co-cultured microbes and that these interactions are representative of similar NP-mediated microbial interactions ubiquitous in nature.35

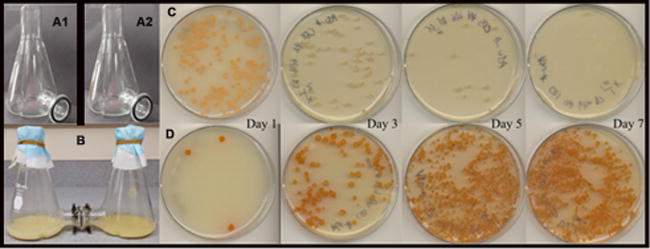

Figure 1.

Structure of new co-culture-dependent antibiotic keyicin (1).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Detection of New Antibiotic via Interspecies Interactions

We have previously developed a microscale co-culturing platform to investigate interspecies interactions between marine invertebrate-associated bacteria with a special emphasis on both genomics and metabolomics.36 Notably, during the course of co-culturing Mycobacterium sp. with Micromonospora WMMB-235, Mycobacterium inhibition became evident over time. Co-culture-derived antimicrobial activities were selective against the Gram+ bacteria Bacillus subtilis and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus as well as Mycobacterium sp. and Rhodococcus sp. Notably, all co-culture systems were characterized by a dark red pigmentation that was absent in corresponding monocultures and, of the co-culture systems investigated, the Micromonospora– Rhodococcus system generated the largest zone of inhibition. Consequently, the Micromonospora–Rhodococcus co-culture system was selected for subsequent metabolomics analysis.

We applied a self-generated in-house LCMS-based metabolomics platform to compare metabolite production between co-cultures and monocultures.36, 37 Initial fluctuations in LCMS analyses in replicate co-cultures and monocultures were postulated to arise from variable cell concentrations within the seed cultures used to inoculate co-cultures. To alleviate such variances, five seed cultures were inoculated and combined (instead of one culture) prior to co-culturing (see Methods). Repeated microscale co-cultures, using this improved inoculation approach, were evaluated by LCMS-Principal Component Analysis (PCA) metabolomics (Figure 2).36 In the scores plot, spatial separations of metabolites produced in co-culture versus monoculture extracts were observed. Individual metabolites responsible for observed variances were clearly depicted in the loadings plot. Each symbol in the loadings plot corresponds to a retention time (RT)-mass-to-charge (m/z) pair. Compounds clustered in the center of the loadings plot were present in all three strains, while compounds diverging from the cluster represent uniquely produced metabolites. Notably, several compounds were identified as being exclusively produced in co-culture (Figure 2).

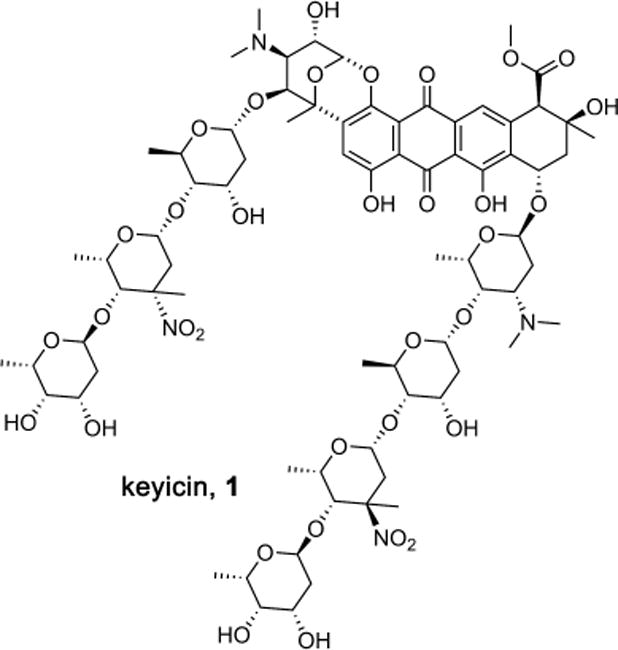

Figure 2.

LCMS-PCA metabolomics of Micromonospora sp. and Rhodococcus sp. co-culture. (A) PCA scores plot describing variance in metabolites in co-culture and monoculture extracts of the Micromonospora sp. and Rhodococcus sp. (B) PCA loadings plot displaying individual metabolites responsible for the variance observed between extracts; the high variance seen in co-culture extracts is attributable to metabolites highlighted by the yellow oval in plot 2B.

Having identified the metabolite likely driving co-culture antimicrobial activity, we carried out bioactivity-guided fractionation of the co-culture extract. A series of related doubly-charged ions [M + 2H]2+ = 790.3625, 797.3521 and 805.3524 amu likely correlating to the antimicrobial species was observed and extracted ion chromatograms for each mass confirmed that species production was exclusive to the Micromonospora–Rhodococcus co-culture (Supporting Information, Figures S1, S2). Dereplication concerns dictated that all three masses be queried against the Antibase NP database. The co-culture specific species, on the basis of these early efforts, appeared to be previously unreported thus confirming the presumed need to generate keyicin on a scale compatible with complete structural elucidation efforts.

To support structural and mechanistic elucidation efforts both microscale (500 μL) and standard scale (100 mL) fermentations were carried out and sampled daily over a 14 d period.36 On the basis of LC/MS analyses, keyicin was confirmed to be produced exclusively in co-culture regardless of fermentation scale (see Supporting Information) although microscale fermentations afforded keyicin with reduced rates relative to standard scale fermentations. On the basis of these findings, subsequent fermentations were carried out for 14 d. Before transitioning to large scale fermentations, a media study was carried out using four media: ASW-A [20 g soluble starch, 10 g glucose, 5 g peptone, 5 g yeast extract, 5 g CaCO3 in 1 L artificial seawater (ASW)], ASW-D (2 g yeast extract, 5 g malt extract and 2 g dextrose in 1 L ASW), ISP2 (4 g yeast extract, 10 g malt extract and 4 g dextrose in 1 L ASW) and M1 (10 g soluble starch, 4 g yeast extract, 2 g peptone, 15 g agar in 1 L ASW). LC/MS analyses indicated that nutrient limited ASW-D media produced the highest yields of keyicin. Hence, large scale co-cultures of Micromonospora and Rhodococcus were carried out for 14 d using ASW-D media enabling sufficient quantities of keyicin to be generated.

Complementary to structure elucidation efforts we also sought to understand the nature of keyicin induction in co-culture. Inspired by earlier reports that NP production in co-cultures of Actinobacteria and mycolic acid-containing bacteria required physical contact between cell types, we endeavored specifically to determine if keyicin biosynthesis might be triggered by physical cell–cell contact.38 Employing customized growth flasks separated with a 0.2 μm diffusible membrane monocultures of the Micromonospora sp. WMMB-235 and Rhodococcus sp. were cultured on either side of the membrane (Figure 3). Daily sampling, plating onto agar and incubation revealed that i) indeed, neither cell type could traverse the 0.2 μm membrane, and ii) over the course of 7 d the growth of the Micromonospora sp. remained relatively consistent whereas the Rhodococcus sp. suffered significant growth inhibition (Figure 3). Most importantly, production of keyicin was observed by LC/MS. Not surprisingly, disc diffusion of keyicin onto lawns of the Rhodococcus sp. or Mycobacterium sp. WMMA-183 revealed this compound’s antibacterial activity thereby supporting our early observations of growth inhibition during microscale co-cultures. On the basis of these findings it was clear that keyicin biosynthesis does not require physical interactions between the Rhodococcus “inducing cells” and the putative Micromonospora sp. producer of 1.

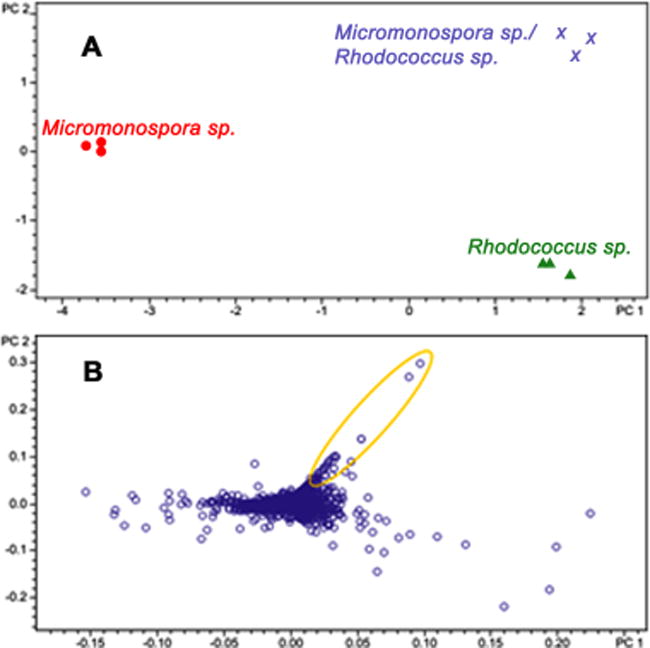

Figure 3.

Cell-cell contact study between Micromonospora sp. WMMB-235 and Rhodococcus sp. WMMA-185. (A1 and A2) Each half of custom co-culture vessel enabling separation of two independent cultures with 0.2 μm filter. (B) Intact co-culture vessel with filter membrane separating cell types. (C) Aliquots of the Rhodococcus sp. and (D) aliquots of the Micromonospora sp. removed from culture, diluted, and streaked every 2 d.

Characterization of the keyicin scaffold

FTICR MS analysis of keyicin (1) revealed its molecular formula to be C75H108N4O34 via isotopic fine structure analysis and its 2D structure was determined on the basis of extensive 1H and 13C NMR data sets (Supporting Information). Analysis of 13C NMR data and the red pigment suggested a sp2 hybridized conjugated carbon skeleton, but only a single aromatic proton, H-3, was observed by 1H NMR. Additionally, the number of 13C resonances did not match the molecular formula. Only after isotopic labeling with 13C-glucose were all resonances detected. We hypothesize that dynamics on the NMR time scale caused severe broadening of H-11 and affected 13C acquisition in the absence of 13C isotopic labeling. Another potentially confounding feature of keyicin was the presence of eight anomeric protons suggesting a multiply glycosylated aglycone. Given this complexity, it was no surprise that classical 2D NMR experiments, including COSY, HSQC and HMBC experiments failed to shed much insight into the structure of the keyicin aglycone.

13C Isotopic incorporation was evaluated with the goal in mind of executing 13C–13C COSY experiments; these would enable us to confidently assign the 13C–13C spin system.7 Optimized 13C incorporation conditions were identified (Supporting Information, Table S2, Figure S5) enabling extensive use of COSY, HMBC and ROESY approaches to solve the structure of 1.

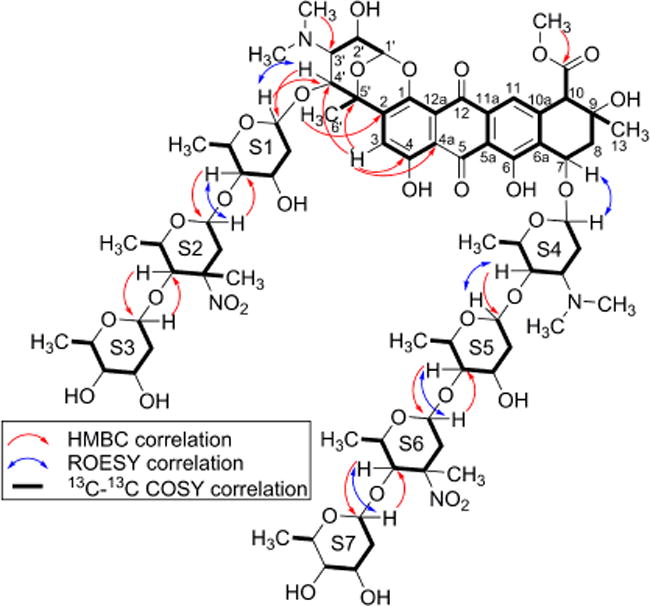

Analysis of the 13C–13C COSY data allowed for rapid characterization of the polycyclic phenolic aglycone. Furthermore, the 13C–13C COSY and extensive 1D and 2D NMR data enabled characterization of the eight sugar moieties. The position of H-3 was confirmed using HMBC correlations to C-4a, C-4, C-4′, and C-5′. The C–C spin system beginning with the attachment between C-2 and C-5′, along with HMBC correlation from H-3 to C-4′ and C-5′, indicated a sugar moiety fused to the aglycone. Glycosidic linkages were determined using a combination of HMBC and ROESY correlations to complete the 2D structure of 1 (Figure 4 and Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

Key HMBC (red) and ROESY (blue) correlations in core of (1) and for determination of glycosidic linkages. Carbon connectivities determined by 13C–13C COSY correlations (red). Detailed application of specific ROESY correlations were instrumental in determining S1–S7 configurations (Supporting Information).

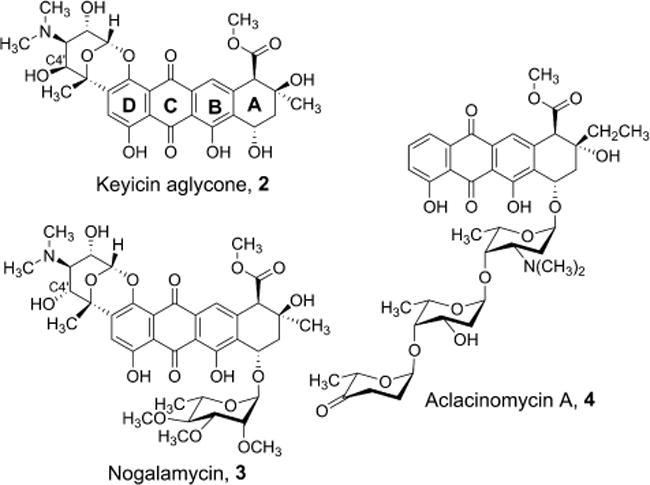

Strikingly, elucidation of the 2D structure of 1 revealed remarkable similarities, especially with respect to keyicin’s aglycone core scaffold, to a number of other NPs whose biosynthetic origins and biological activities are well established. These similarities, especially between the keyicin aglycone, nogalamycin and aclacinomycin A (Figure 5), would come to greatly expedite our efforts to understand the structure and biosynthetic origins of cryptically-encoded NP 1.

Figure 5.

Direct comparisons of the keyicin aglycone core to the intact structure of nogalamycin and the more classically arranged anthracycline aclacinomycin A.

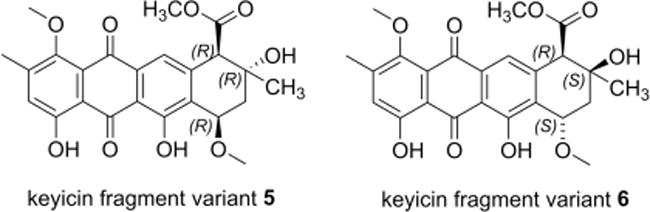

The structural relatedness of keyicin and nogalamycin aglycones proved instrumental in establishing the relative configuration of 1. Comparisons of 13C shifts for keyicin to those previously established for anthracyclines like aclacinomycin A, arugomycin (AGM) and viriplanin A proved instrumental also in elucidating the structures of sugars S1–S7 (Figure 4 for sugar numbering) as did careful evaluation of HMBC and ROESY correlations (Supporting Information Table S1 and Supporting Experimentals). Moreover, S1–S7 were subjected to conformer distribution analyses using Spartan ‘14 and conformers with a Boltzmann distribution ≥5% were subjected to geometry optimization and 13C NMR calculations.39 Calculated carbon chemical shifts were compared to experimental values using the DP4 probability method and the results of these comparisons used to support or refute configurational assignments made on the basis of 13C chemical shift comparisons to known anthracyclines (see Supporting Information).40 For the more rigid keyicin aglycone, carbon chemical shifts were calculated using an equilibrium conformer followed by geometry optimization and 13C NMR calculations. Despite the smaller difference between calculated and experimental carbon chemical shifts (Δ) for anthraquinone structure 6 versus 5 (Figure 6), DP4 calculations indicated 5 to be slightly favored over 6 (see Supporting Information Figure S20 for complete analysis).

Figure 6.

Partial characterization of anthracycline core possibilities for keyicin via application of molecular modeling and DFT calculation approaches. See Supporting Information for experimental data for these and alternative variants.

However, comparisons of the methyl C-13 chemical shift for similar anthracyclines including nogalamycin (3) AGM,41, 42 and viriplanin A43 suggested that the methyl C-13 was on the opposite side of the plane relative to the C-10 pendant carboxymethyl moiety. Consequently, the keyicin A-ring stereochemistry was ultimately assigned as shown by 6 (see Supporting Information).

Elucidation of keyicin’s C1′–C6′ fragment also relied heavily upon comparisons to known anthracyclines. Well established AGM and viriplanins as well as keyicin, all belong to the nogalamycin class of anthracyclines; a key differentiating feature is that nogalamycin itself (3) bears only a pendant OH moiety at C4′ site whereas all other members of the class bear O-trisaccharide linkages to C4′. This structural feature of 3 versus all other known members of the nogalamycin class proved instrumental in assigning the C4′ configuration of keyicin.

Comparisons of 13C chemical shifts for C1′–C6′ of the noted anthracyclines suggested identical stereochemistry among the molecules; a notable exception being the R-configuration and absence of sugar substitution at C4′ for 3. Given the high degree of structural similarity between AGM and keyicin we paid special attention to the 13C shifts for C3′–C6′ keeping in mind the influence that C4′ configuration would have on the surrounding centers. For AGM these values (C3′ = 62.5, C4′ = 81.6, C5′ = 77.6, C6′ = 23.6 ppm) aligned extremely well with those observed for keyicin (C3′ = 62.7, C4′ = 82.5, C5′ = 78.2, C6′ = 24.2 ppm). In addition, the C3′ pendant N-CH3 resonances for AGM and keyicin at 44.3 and 44.6 ppm, respectively, strongly supported identical C4′ configurations. Given their putatively identical aglycone configuration, AGM served, in comparisons to 3, as an effective proxy for keyicin. Accordingly, 13C shift differences for C4′ as well as each compounds proximal N-CH3 and C6′ carbon suggested different C4′ configuration between nogalamycin and AGM, and by default, keyicin; differences of 2.4, 1.7 and 1.6 ppm were noted for C4′, N-CH3, and C6′, respectively. These data firmly supported the hypothesis that the aglycones of AGM and keyicin share identical configuration.

That keyicin shares the C4′ S-configuration previously demonstrated for AGM and related C4′-glycosylated members of the nogalamycin class was further validated by ROESY. Having defined the relative configuration of all stereocenters in S1 on the basis of ROESY correlations (Supporting Information) we noted a clear ROESY correlation between a C3′ pendant dimethylamine CH3 and the axial anomeric H of S1. This correlation was consistent with a syn placement of H3′ and H4′ of the C1′–C6′ tetrahydropyran moiety and ultimate assignment of the S-configuration to the keyicin C4′.

Enzymatic studies with 3 have indicated that two enzymes, SnoK and SnoN, are responsible, respectively, for i) installing the C2–C5′ bond resulting in carbocyclization, and ii) an epimerization at nogalamycin’s C4′ position.44 Notably, genomic analyses of the keyicin biosynthetic pathway (discussed below) revealed the presence of both snoK and snoN homologs. Thus, the difference in C4′ configurations between nogalamycin and keyicin may be related to the presence of keyicin’s C4′ tethered sugar moiety. We posit that the relative absence of substantive functionality appended to the nogalamycin C4′ enables SnoN-catalyzed epimerization. Conversely, SnoN homologs in the keyicin (and possibly other anthracycline) pathways, may not have C4′ access sufficient to permit epimerization.

Having elucidated the structure of 1, it becomes apparent that a number of interesting features differentiate keyicin from all other related anthracyclines: i) one of the two polysaccharides projected from the aglycone likely assumes a zwitterionic form under physiologically relevant conditions, and ii) its construction requires co-culture conditions implying that it plays an important and tunable role in bacterial competition/defensive processes; to date there is no evidence to suggest that other related anthracyclines play as important a role in competitive microbe-microbe associations.

Proteomics Analysis of Keyicin-producing Co-culture and Biosynthetic Insights

Early efforts strongly suggested the Micromonospora sp. as the source of 1 in co-cultures and indeed, sequencing of its genome revealed BGCs representative of one type I polyketide synthase (PKS), two type II PKSs, one type III PKS, one lanthipeptide and six hybrid clusters.45 Also notable were ORFs encoding seven glycosyltransferases (GTs) associated with S1–S7; further functional annotations within the putative keyicin BGC (Supporting Information, Tables S3, S4) further implicated the Micromonospora sp. as the producer of 1 in co-culture. Sequencing of the Rhodococcus sp. genome46 on the other hand, failed to reveal any evidence of type II PKS ORFs.

With this genomic information in hand we carried out proteomic analyses of Micromonospora–Rhodococcus co-cultures and monocultures targeting only large proteins for identification; all significant proteins (or fragments thereof) were identified using PEAKS47 software and imported raw LC-MS/MS data were used to search the annotated Micromonospora sp. and Rhodococcus sp. genomes45, 46 Five proteins associated with keyicin construction were identified in both co-culture and Micromonospora sp. monoculture. Putative generic cyclase (Kyc9), dTDP-4-dehydrorhamnose 3,5-epimerase (Kyc28) and PKS cyclase (Kyc34) enzymes were detected in biological triplicate analyses as were a phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase (product of kyc17) and a 3-oxoacyl-(acyl-carrier protein). Significantly, all five Micromonospora-derived enzymes predicted during early genomics efforts and a DUF4440 domain-containing protein (termed Kyc51) were identified in all co-culture replicates, but in only one replicate of the Micromonospora sp. monoculture suggesting that, when confronted with the Rhodococcus-specific components (as during co-cultures), the Micromonospora sp. amplifies expression of specific biosynthetic proteins associated with keyicin production.

Anthracycline BGCs and Structures Illuminate Keyicin Construction

Genomics data for both co-culture organisms45, 46 allow us to glean significant biosynthetic and structural insights far exceeding our assignment of the Micromonospora sp. as the induced manufacturer of 1. Indeed, these data provide significant validation of the proteomics information enabling assignment of keyicin biosynthesis to the Micromonospora sp. rather than the Rhodococcus strain. In addition to having aided the structural characterization of keyicin, nogalamycin (MIBiG: BGC0000250) and aclacinomycin A (MIBiG: BGC0000191→BGC0000193) again serve as important reference points by way of their well-established biosynthetic gene clusters. The high degree of structural and genetic similarity between the keyicin and nogalamycin systems provide further validation, not only of the keyicin producer assignment but also key structural assignments for keyicin.

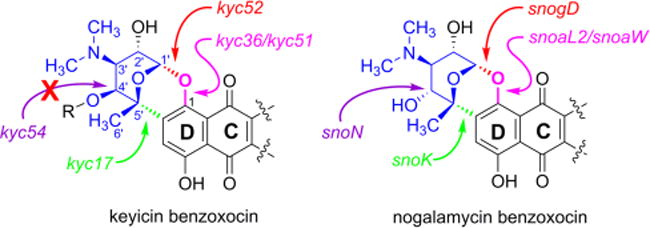

Of interest were genes located within each BGC that code for highly specific, and unique functionalities that define the shared keyicin/nogalamycin benzoxocin scaffold as highlighted in Figure 7. Review of the BGCs for both natural products revealed well over 30 genes across both systems that share > 60% similarity (Supporting Information, Table S3); the most interesting of these relate to benzoxocin construction. It is now well established that the products of snoaL2 and snoaW hydroxylate the C-1 of a nogalamycinone intermediate48, 49 followed by glycosylation of the newly installed phenol with nogalamine by SnogD50 and that the redox enzyme SnoK44 carries out C–C bond formation linking the C5′ of the newly installed nogalamine ortho to the newly generated aryl ether linkage. Genes within the kyc cluster responsible for this same sequence of transformations are kyc36/kyc51 followed by kyc52 (glycolase) and kyc17, respectively (Figure 7). The structural assignments made in advance of BGC studies are strongly supported by these genomic data.

Figure 7.

Correlations of orfs (and resulting gene products) to key benzoxocin linkages for keyicin versus nogalamycin aglycones. Gene/enzyme similarities across the two NP systems are color coded with arrows indicating key linkages installed. Notably only kyc54 and snoN appear to be similar yet fail to carry out the same chemistry upon their respective substrates.

In addition to genes dictating benzoxocin construction in both BGCs, a great many other genes have been identified within the kyc cluster showing strong similarity/homology to nogalamycin cluster components. A handful of these critical putative homologs are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selection of key BGC gene correlations between keyicin and nogalamycin clusters

| kyc gene | Nogalamycin BGC gene | Accession # for kyc gene | Accession # for nogalamycin gene | Putative function for established gene product | % identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kyc9 | snoaM51 | OHX01513.1 | AAF01818.1 | polyketide cyclase | 78% |

| kyc17 | snoK44 | OHX01520.1 | AAF01812.1 | non-heme iron α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)–dependent carbocyclase | 62% |

| kyc25 | snogE51-53 | OHX01526.1 | AAF01809.1 | GT for nogalose | 62% |

| kyc34 | snoaL48 | OHX01535.1 | AAF01813.1 | nogalonic acid methyl ester (NAME) cyclase | 77.8% |

| kyc36 | snoaW49, 54 | OHX01536.1 | AAF01810.1 | putative hydroxylase (in tandem with SnoaL2) | 60.7% |

| kyc44 | snogA55 | OHX01543.1 | AAF01819.1 | amino methyltransferase | 67.2% |

| kyc51 | snoaL249 | OHX01549.1 | AAF01808.1 | C-1 hydroxylase component (in tandem with SnogW) | 63.2% |

| kyc52 | snogD50, 52, 53 | OHX01550.1 | AAF01811.1 | GT (specifically, nogalamine-transferase) | 65% |

| kyc54 | snoN44 | OHX01552.1 | AAF01805.1 | SnoK homolog with epimerase role | 71% |

The benzoxocin moieties of keyicin and nogalamycin differentiate these species from the overwhelming majority of other anthracyclines. Even between keyicin and nogalamycin however, an important differentiation is observed beyond the benzoxocin scaffold. SnoN (encoded within the nogalamycin cluster) is responsible for setting the C4′ configuration of nogalamycin via epimerization.44 Within the kyc cluster, kyc54 codes for a highly similar enzyme (71% similarity, Table 1) yet the C4′ configuration in keyicin is inverted relative to that in nogalamycin. In considering the origins of this stereochemical difference we posit that the presence of the pendant trisaccharide at C4′ in keyicin likely prohibits Kyc54-promoted epimerization. Devoid of any similar steric encumbrance, SnoN is presumably highly efficient at processing the less heavily glycosylated nogalamycin intermediate. Thus, we propose that the pendant C4′-linked sugar in keyicin prohibits Kyc54 action. This is interesting not only in the context of contrasting the keyicin and nogalamycin systems but also because it suggests that C4′ epimerization in each pathway comes at a very late stage during biosynthesis and is presumably a “post-tailoring” step; it is rare that an aglycone is subject to post-tailoring modifications. The data observed here however, suggests that the keycin/nogalamycin systems may be one such representative.

In addition to clear similarities between the nogalamycin and keyicin scaffolds and BGCs MIBiG accession numbers identified using antiSMASH revealed often dramatic genetic similarity to BGCs for other anthracycline natural products. The keyicin BGC was found to have very highly shared gene content to the BGCs for cinerubin B (MIBiG: BGC0000212, 88%), cosmomycin D (MIBiG: BGC0001074, 88%), arimetamycin (MIBiG: BGC0000199, 84%), kosinostatin (MIBiG: BGC0001073, 75%), aclacinomycin (MIBiG: BGC0000191, 72%) (Supporting Information, Table S5, Figure S21 for relevant structures). To put these data into context, it is instructive to note that the BGCs for keyicin and nogalamycin (MIBiG: BGC0000250) display 52% overall similarity.

A-ring glycosylation during keyicin construction provides yet another opportunity to correlate features of the kyc BGC to those of other, more well-established anthracycline BGCs. During aclacinomycin construction the enzyme duo of AknS and AknT employs TDP-l-rhodosamine to tether a rhodosamine sugar to the precursor aklavinone C7-OH moiety.56 AknK then employs TDP-2-deoxy-l-fucose to glycosylate the newly added rhodosamine moiety.57 The resulting disaccharide can undergo another cycle of glycosylation at the hands of AknK to render the final trisaccharide.57 Notably, within the cosmomyin D cluster, cosK displays 79% similarity to aknK and has been shown experimentally to carry out the same transformation during cosmomycin D construction as that of AknK during aclacinomycin A production.58 Like aclacinomycin, cosmomycin D production calls for C7-OH glycosylation with L-rhodosamine. This transformation is carried out by CosG which transfers rhodosamine to both the 7- and 10-positions of the cosmomycin aglycone; the C7-OH tethered species then serves as a substrate for fucosylation by CosK en route to the final trisaccharide that distinguishes this species from other members of the cosmomycin family.58 Not surprisingly, the kyc cluster contains three genes with moderate to good similarities to the GTs noted above; SEARCHGTr software further supported early hypotheses correlating specific chemistries to kyc genes.59 For rhodosamine transfer, kyc26 displays 43% similarity to AknT (AAF73456.1) and kyc25 shows 56% similarity to AknS (AAF73455.1); with regard to the cosmomycin system, kyc25 shows 60% similarity to CosG (KDN80069.1). In considering fucose transfer, AknK appears to have a number of candidate homologs within the kyc cluster; these genes, with accompanying similarities to AknK, include kyc12 (48.5%), kyc20 (52%), kyc24 (53%), kyc29 (50%), kyc32 (47.7%) and kyc52 (30%). The application of SEARCHGTr, a program specifically designed for GT analysis that takes into consideration donor and recipient active site architectures further supported the notion that GTs involved in keyicin construction bear similarity to other more well-established GTs (Supporting Information, Table S4).59 Not surprisingly, the same kyc genes, with the exception of kyc52, with similarity to AknK also prove similar to CosK. Putative CosK homolog candidates include the keyicin biosynthetic products of kyc12 (49.8%), kyc20 (54%), kyc24 (55%), kyc29 (27.4%), and kyc32 (48.8%). Consequently, many elements within the kyc BGC correlate both keyicin structural and genomics features to those of other closely related anthracyclines (Supporting Information, Table S5). These strong associations across compounds and their microbial producers provide strong support for our structural elucidation of keyicin and illuminate opportunities for potential biosynthetic engineering efforts.

Biological Activity of Keyicin

Keyicin (1) was screened against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Similar to the observed antibiotic activity of the crude extracts, keyicin exhibited selective Gram-positive activity. In addition to the growth inhibition of Mycobacterium sp. and Rhodococcus sp., keyicin inhibited B. subtilis and Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) at minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 8 μg/mL (9.9 μM) and 2 μg/mL (2.5 μM), respectively.

Chemical Genomics Shed Insight into Key-icin Mechanism of Action

Chemical genomics (CG) provides a means of rapidly and comprehensively assessing the pathways and processes that underlie cellular vulnerabilities to small molecules. Likewise, CG can also give insight into mechanisms of cellular resistance to such agents. We employed CG to gain broad insight into keyicin’s biological mode of action. Specifically we assessed the ability of keyicin, like other anthracyclines, to induce DNA damage as reflected by downstream effects.60-62 Cells bearing mutations that impair the ability to sustain DNA damage are more susceptible to DNA damaging agents than are those with intact compensatory mechanisms. Accordingly, we treated a barcoded E. coli deletion collection with keyicin (12.5 μg/mL) and compared the resulting CG profile with those obtained from cells exposed to the well-established DNA-intercalator ethidium bromide (100 μg/mL), and methyl methanesulfonate (MMS, 0.0125%), a known DNA alkylating/damaging agent. The CG profile of keyicin was distinct from EtBr and MMS (Supporting Information, Figure S22); The profiles of EtBr and MMS had a correlation coefficient of 0.47. Keyicin, on the other hand, had a correlation of 0.11 with EtBr and 0.16 with MMS. Particularly telling was that cells bearing inactivations of recA, a key gene involved in DNA repair in E. coli and established indicator of DNA damaging agents,63 proved particularly susceptible to the effects of EtBr and MMS yet were essentially unaffected by keyicin (Supporting Information for detailed data analysis).

Among the 20 E. coli mutants most sensitive to keyicin, not a single one is involved in DNA replication or repair machineries, strongly suggesting that keyicin’s principal mode of action does not involve DNA damage. In fact, in considering the 46 gene mutants with significant sensitivities to keyicin (Supporting Information, Table S7). no clear and significant functional enrichment is apparent to help illuminate keyicin’s mode of action. Evaluations of the network around these 46 genes suggest, tentatively, that keyicin may exert antibacterial activity through modulation of fatty acid metabolism (Supporting Information). Consequently, investigations of keyicin’s impact on bacterial lipid metabolism, as expeditiously brought to light by these CG studies, are clearly warranted.

Conclusions

The advent of interdisciplinary omics technologies has made clear that cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters encode for a significant number of, as yet unknown, but potentially promising antibiotics. We previously developed an approach to investigate the secondary metabolite induction resulting from interspecies interactions. Using this approach, a Rhodococcus sp. was found to induce production of a new antibiotic, keyicin, when co-cultured with Micromonospora sp. Structure elucidation of keyicin was assisted by 2D 13C NMR and informed, in part, by comparisons of key elements of its BGC with those of structurally related and biosynthetically characterized anthracyclines. Production of keyicin was not dependent on direct cell-cell contact, which contradicts previous reports of secondary metabolite induction by mycolic acid-containing bacteria. Keyicin was selectively active against Gram-positive bacteria including both Rhodococcus sp. and Mycobacterium sp. The E coli chemical genomics provided encouraging results surrounding a putative unique MOA for keyicin, and importantly, one that does not involve DNA damage.

METHODS

See the Supporting Information for details.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy and from the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research funded through NIH/NCATS UL1TR000427. This work was also funded by the NIH through the administration of NIGMS Grants R01GM104192 (T.S.B.) and R01GM104975 (to C.L.M), NIDDK R01DK071801 (to L.L.), HGRI grants R01HG005084 (to C.L.M) and 1R01HG0050 (to C.L.M. & J.S.P.) as well as U19-Al109673 (to C.R.C.). NIH Biotechnology training grants T32GM008347 (to S.W.S.) and T32GM008505 (to M.C.) are also gratefully acknowledged; S.W.S. is also supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (00039202). We thank the Analytical Instrumentation Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison for the facilities to acquire spectroscopic data. Orbitrap instruments were purchased through the support of an NIH shared instrument grant (NIH-NCRR S10RR029531 to L.L.) and the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. This study made use of the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison (NMRFAM), which is supported by NIH grant P41GM103399. Additional equipment was purchased with funds from the University of Wisconsin, the NIH (RR02781, RR08438), the NSF (DMB-8415048, OIA-9977486, BIR-9214394), and the USDA. L.L. acknowledges a Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professorship and a Janis Apinis Profes sorship with funding provided by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy. We also thank D. Demaria for assistance with sample collection and express our appreciation to H. Mori (Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Ikoma, Japan) for generous provision of the barcoded E. coli deletion collection.

Footnotes

All experimental procedures with complete spectroscopic data sets and spectra, S1–S7 spectroscopic characterizations/logic along with validating modeling and DFT calculations, all chemical genomics data (some as excel files) and noted BGC information for keyicin and nogalamycin as well as chemical structures for the noted anthracyclines are provided as supporting information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

ORCID

Tim S. Bugni: 0000-0002-4502-3084

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Pye CR, Bertin MJ, Lokey RS, Gerwick WH, Linington RG. Retrospective analysis of natural products provides insights for future discovery trends. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:5601–5606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614680114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuet KP, Tirrell DA. Chemical tools for temporally and spatially resolved mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:299–311. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0878-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang JY, Sanchez LM, Rath CM, Liu X, Boudreau PD, Bruns N, Glukhov E, Wodtke A, de Felicio R, Fenner A, Wong WR, Linington RG, Zhang L, Debonsi HM, Gerwick WH, Dorrestein PC. Molecular networking as a dereplication strategy. J Nat Prod. 2013;76:1686–1699. doi: 10.1021/np400413s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watrous J, Roach P, Alexandrov T, Heath BS, Yang JY, Kersten RD, van der Voort M, Pogliano K, Gross H, Raaijmakers JM, Moore BS, Laskin J, Bandeira N, Dorrestein PC. Mass spectral molecular networking of living microbial colonies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E1743–1752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203689109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shih CJ, Chen PY, Liaw CC, Lai YM, Yang YL. Bringing microbial interactions to light using imaging mass spectrometry. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31:739–755. doi: 10.1039/c3np70091g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinn RA, Nothias LF, Vining O, Meehan M, Esquenazi E, Dorrestein PC. Molecular Networking As a Drug Discovery, Drug Metabolism, and Precision Medicine Strategy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38:143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohimani H, Kersten RD, Liu WT, Wang M, Purvine SO, Wu S, Brewer HM, Pasa-Tolic L, Bandeira N, Moore BS, Pevzner PA, Dorrestein PC. Automated genome mining of ribosomal peptide natural products. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:1545–1551. doi: 10.1021/cb500199h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medema MH, Kottmann R, Yilmaz P, Cummings M, Biggins JB, Blin K, de Bruijn I, Chooi YH, Claesen J, Coates RC, Cruz-Morales P, Duddela S, Dusterhus S, Edwards DJ, Fewer DP, Garg N, Geiger C, Gomez-Escribano JP, Greule A, Hadjithomas M, Haines AS, Helfrich EJ, Hillwig ML, Ishida K, Jones AC, Jones CS, Jungmann K, Kegler C, Kim HU, Kotter P, Krug D, Masschelein J, Melnik AV, Mantovani SM, Monroe EA, Moore M, Moss N, Nutzmann HW, Pan G, Pati A, Petras D, Reen FJ, Rosconi F, Rui Z, Tian Z, Tobias NJ, Tsunematsu Y, Wiemann P, Wyckoff E, Yan X, Yim G, Yu F, Xie Y, Aigle B, Apel AK, Balibar CJ, Balskus EP, Barona-Gomez F, Bechthold A, Bode HB, Borriss R, Brady SF, Brakhage AA, Caffrey P, Cheng YQ, Clardy J, Cox RJ, De Mot R, Donadio S, Donia MS, van der Donk WA, Dorrestein PC, Doyle S, Driessen AJ, Ehling-Schulz M, Entian KD, Fischbach MA, Gerwick L, Gerwick WH, Gross H, Gust B, Hertweck C, Hofte M, Jensen SE, Ju J, Katz L, Kaysser L, Klassen JL, Keller NP, Kormanec J, Kuipers OP, Kuzuyama T, Kyrpides NC, Kwon HJ, Lautru S, Lavigne R, Lee CY, Linquan B, Liu X, Liu W, Luzhetskyy A, Mahmud T, Mast Y, Mendez C, Metsa-Ketela M, Micklefield J, Mitchell DA, Moore BS, Moreira LM, Muller R, Neilan BA, Nett M, Nielsen J, O’Gara F, Oikawa H, Osbourn A, Osburne MS, Ostash B, Payne SM, Pernodet JL, Petricek M, Piel J, Ploux O, Raaijmakers JM, Salas JA, Schmitt EK, Scott B, Seipke RF, Shen B, Sherman DH, Sivonen K, Smanski MJ, Sosio M, Stegmann E, Sussmuth RD, Tahlan K, Thomas CM, Tang Y, Truman AW, Viaud M, Walton JD, Walsh CT, Weber T, van Wezel GP, Wilkinson B, Willey JM, Wohlleben W, Wright GD, Ziemert N, Zhang C, Zotchev SB, Breitling R, Takano E, Glockner FO. Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:625–631. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krug D, Muller R. Secondary metabolomics: the impact of mass spectrometry-based approaches on the discovery and characterization of microbial natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31:768–783. doi: 10.1039/c3np70127a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kersten RD, Yang YL, Xu Y, Cimermancic P, Nam SJ, Fenical W, Fischbach MA, Moore BS, Dorrestein PC. A mass spectrometry-guided genome mining approach for natural product peptidogenomics. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:794–802. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin CR, Sherrod SD, Marasco CC, Bachmann BO, Schramm-Sapyta N, Wikswo JP, McLean JA. Phenotypic mapping of metabolic profiles using self-organizing maps of high-dimensional mass spectrometry data. Analytical chemistry. 2014;86:6563–6571. doi: 10.1021/ac5010794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan KR, Crusemann M, Lechner A, Sarkar A, Li J, Ziemert N, Wang M, Bandeira N, Moore BS, Dorrestein PC, Jensen PR. Molecular networking and pattern-based genome mining improves discovery of biosynthetic gene clusters and their products from Salinispora species. Chem Biol. 2015;22:460–471. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covington BC, McLean JA, Bachmann BO. Comparative mass spectrometry-based metabolomics strategies for the investigation of microbial secondary metabolites. Nat Prod Rep. 2017;34:6–24. doi: 10.1039/c6np00048g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barkal LJ, Theberge AB, Guo CJ, Spraker J, Rappert L, Berthier J, Brakke KA, Wang CC, Beebe DJ, Keller NP, Berthier E. Microbial metabolomics in open microscale platforms. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10610. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boddy CN. Bioinformatics tools for genome mining of polyketide and non-ribosomal peptides. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;41:443–450. doi: 10.1007/s10295-013-1368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakraborty C, Doss CG, Patra BC, Bandyopadhyay S. DNA barcoding to map the microbial communities: current advances and future directions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:3425–3436. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5550-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh CT, Fischbach MA. Natural Products Version 2.0: Connecting Genes to Molecules. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132:2469–2493. doi: 10.1021/ja909118a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischbach MA, Walsh CT, Clardy J. The evolution of gene collectives: How natural selection drives chemical innovation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4601–4608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709132105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cantley AM, Clardy J. Animals in a bacterial world: opportunities for chemical ecology. Nat Prod Rep. 2015;32:888–892. doi: 10.1039/c4np00141a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart EJ. Growing unculturable bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:4151–4160. doi: 10.1128/JB.00345-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman DJ. Predominately Uncultured Microbes as Sources of Bioactive Agents. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1832. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cimermancic P, Medema MH, Claesen J, Kurita K, Wieland Brown LC, Mavrommatis K, Pati A, Godfrey PA, Koehrsen M, Clardy J, Birren BW, Takano E, Sali A, Linington RG, Fischbach MA. Insights into secondary metabolism from a global analysis of prokaryotic biosynthetic gene clusters. Cell. 2014;158:412–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz M, Hover BM, Brady SF. Culture-independent discovery of natural products from soil metagenomes. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;43:129–141. doi: 10.1007/s10295-015-1706-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mora C, Tittensor DP, Adl S, Simpson AG, Worm B. How many species are there on Earth and in the ocean? PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amaral-Zettler L, Artigas LF, Baross J, Bharathi PAL, Boetius A, Chandramohan D, Herndl G, Kogure K, Neal P, Pedrós-Alió C, Ramette A, Schouten S, Stal L, Thessen A, Leeuw Jd, Sogin M. Life in the World’s Oceans. Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. A Global Census of Marine Microbes; pp. 221–245. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adnani N, Rajski SR, Bugni TS. Symbiosis-inspired approaches to antibiotic discovery. Nat Prod Rep. 2017;34:784–814. doi: 10.1039/c7np00009j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gubbens J, Zhu H, Girard G, Song L, Florea BI, Aston P, Ichinose K, Filippov DV, Choi YH, Overkleeft HS, Challis GL, van Wezel GP. Natural product proteomining, a quantitative proteomics platform, allows rapid discovery of biosynthetic gene clusters for different classes of natural products. Chem Biol. 2014;21:707–718. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Lanen SG, Shen B. Microbial genomics for the improvement of natural product discovery. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Micallef ML, D’Agostino PM, Sharma D, Viswanathan R, Moffitt MC. Genome mining for natural product biosynthetic gene clusters in the Subsection V cyanobacteria. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:669. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1855-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medema MH, Fischbach MA. Computational approaches to natural product discovery. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:639–648. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller I, Chevrette M, Kwan J. Interpreting Microbial Biosynthesis in the Genomic Age: Biological and Practical Considerations. Marine Drugs. 2017;15:165. doi: 10.3390/md15060165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Udwary DW, Zeigler L, Asolkar RN, Singan V, Lapidus A, Fenical W, Jensen PR, Moore BS. Genome sequencing reveals complex secondary metabolome in the marine actinomycete Salinispora tropica. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10376–10381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700962104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Florez LV, Biedermann PH, Engl T, Kaltenpoth M. Defensive symbioses of animals with prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms. Nat Prod Rep. 2015;32:904–936. doi: 10.1039/c5np00010f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piotrowski JS, Simpkins SW, Li SC, Deshpande R, McIlwain SJ, Ong IM, Myers CL, Boone C, Andersen RJ. Chemical genomic profiling via barcode sequencing to predict compound mode of action. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, NJ) 2015;1263:299–318. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2269-7_23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clardy J, Fischbach MA, Currie CR. The natural history of antibiotics. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adnani N, Vazquez-Rivera E, Adibhatla SN, Ellis GA, Braun DR, Bugni TS. Investigation of Interspecies Interactions within Marine Micromonosporaceae Using an Improved Co-Culture Approach. Marine drugs. 2015;13:6082–6098. doi: 10.3390/md13106082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hou Y, Braun DR, Michel CR, Klassen JL, Adnani N, Wyche TP, Bugni TS. Microbial strain prioritization using metabolomics tools for the discovery of natural products. Anal Chem. 2012;84:4277–4283. doi: 10.1021/ac202623g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Onaka H, Mori Y, Igarashi Y, Furumai T. Mycolic acid-containing bacteria induce natural-product biosynthesis in Streptomyces species. Applied and Env Microbiol. 2011;77:400–406. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01337-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shao Y, Molnar LF, Jung Y, Kussmann J, Ochsenfeld C, Brown ST, Gilbert AT, Slipchenko LV, Levchenko SV, O’Neill DP, DiStasio RA, Jr, Lochan RC, Wang T, Beran GJ, Besley NA, Herbert JM, Lin CY, Van Voorhis T, Chien SH, Sodt A, Steele RP, Rassolov VA, Maslen PE, Korambath PP, Adamson RD, Austin B, Baker J, Byrd EF, Dachsel H, Doerksen RJ, Dreuw A, Dunietz BD, Dutoi AD, Furlani TR, Gwaltney SR, Heyden A, Hirata S, Hsu CP, Kedziora G, Khalliulin RZ, Klunzinger P, Lee AM, Lee MS, Liang W, Lotan I, Nair N, Peters B, Proynov EI, Pieniazek PA, Rhee YM, Ritchie J, Rosta E, Sherrill CD, Simmonett AC, Subotnik JE, Woodcock HL, 3rd, Zhang W, Bell AT, Chakraborty AK, Chipman DM, Keil FJ, Warshel A, Hehre WJ, Schaefer HF, 3rd, Kong J, Krylov AI, Gill PM, Head-Gordon M. Advances in methods and algorithms in a modern quantum chemistry program package. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2006;8:3172–3191. doi: 10.1039/b517914a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith SG, Goodman JM. Assigning stereochemistry to single diastereoisomers by GIAO NMR calculation: the DP4 probability. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12946–12959. doi: 10.1021/ja105035r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawai H, Hayakawa Y, Nakagawa M, Furihata K, Seto H, Otake N. Arugomycin, a new anthracycline antibiotic. II. Structural elucidation. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1987;40:1273–1282. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawai H, Hayakawa Y, Nakagawa M, Furihata K, Furihata K, Shimazu A, Seto H, Otake N. Arugomycin, a new anthracycline antibiotic. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and physico-chemical properties. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1987;40:1266–1272. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hutter K, Baader E, Frobel K, Zeeck A, Bauer K, Gau W, Kurz J, Schroder T, Wunsche C, Karl W, et al. Viriplanin A, a new anthracycline antibiotic of the nogalamycin group. I. Isolation, characterization, degradation reactions and biological properties. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1986;39:1193–1204. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.39.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siitonen V, Selvaraj B, Niiranen L, Lindqvist Y, Schneider G, Metsa-Ketela M. Divergent non-heme iron enzymes in the nogalamycin biosynthetic pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:5251–5256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525034113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adnani N, Braun DR, McDonald BR, Chevrette MG, Currie CR, Bugni TS. Draft Genome Sequence of Micromonospora sp. Strain WMMB235, a Marine Ascidian-Associated Bacterium. Genome Announcements. 2017;5:e01369–16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01369-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adnani N, Braun DR, McDonald BR, Chevrette MG, Currie CR, Bugni TS. Complete Genome Sequence of Rhodococcus sp. Strain WMMA185, a Marine Sponge-Associated Bacterium. Genome Announcements. 2016;4:e01406–16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01406-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma B, Zhang K, Hendrie C, Liang C, Li M, Doherty-Kirby A, Lajoie G. PEAKS: powerful software for peptide de novo sequencing by tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid communications in mass spectrometry : RCM. 2003;17:2337–2342. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sultana A, Kallio P, Jansson A, Niemi J, Mantsala P, Schneider G. Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic data of SnoaL, a polyketide cyclase in nogalamycin biosynthesis, Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2004;60:1118–1120. doi: 10.1107/S090744490400705X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siitonen V, Blauenburg B, Kallio P, Mantsala P, Metsa-Ketela M. Discovery of a two-component monooxygenase SnoaW/SnoaL2 involved in nogalamycin biosynthesis. Chem Biol. 2012;19:638–646. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Claesson M, Siitonen V, Dobritzsch D, Metsa-Ketela M, Schneider G. Crystal structure of the glycosyltransferase SnogD from the biosynthetic pathway of nogalamycin in Streptomyces nogalater. FEBS J. 2012;279:3251–3263. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klymyshin D, Stephanyshyn O, Fedorenko V. THE ROLE OF STREPTOMYCES NOGALATER Lv65 snoaM, snoaL and snoaE GENES IN NOGALAMYCIN BIOSYNTHESIS. TSitologiia i genetika. 2015;49:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siitonen V, Claesson M, Patrikainen P, Aromaa M, Mantsala P, Schneider G, Metsa-Ketela M. Identification of late-stage glycosylation steps in the biosynthetic pathway of the anthracycline nogalamycin. Chembiochem. 2012;13:120–128. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shao L, Shi X, Liu W, Gao X, Pu T, Ma B, Wang S. Inactivation and identification of three genes encoding glycosyltransferase required for biosynthesis of nogalamycin. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2015;62:765–771. doi: 10.1002/bab.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bechthold A, Yan X. SnoaW/SnoaL2: a different two-component monooxygenase. Chem Biol. 2012;19:549–551. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klimyshin DO, Gren TP, Fedorenko VO. Role of the snorA gene in nogalamycin biosynthesis by strain Streptomyces nogalater Lv65. Mikrobiologiia. 2011;80:490–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leimkuhler C, Fridman M, Lupoli T, Walker S, Walsh CT, Kahne D. Characterization of rhodosaminyl transfer by the AknS/AknT glycosylation complex and its use in reconstituting the biosynthetic pathway of aclacinomycin A. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10546–10550. doi: 10.1021/ja072909o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu W, Leimkuhler C, Oberthur M, Kahne D, Walsh CT. AknK is an L-2-deoxyfucosyltransferase in the biosynthesis of the anthracycline aclacinomycin A. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4548–4558. doi: 10.1021/bi035945i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garrido LM, Lombo F, Baig I, Nur EAM, Furlan RL, Borda CC, Brana A, Mendez C, Salas JA, Rohr J, Padilla G. Insights in the glycosylation steps during biosynthesis of the antitumor anthracycline cosmomycin: characterization of two glycosyltransferase genes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;73:122–131. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0453-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kamra P, Gokhale RS, Mohanty D. SEARCHGTr: a program for analysis of glycosyltransferases involved in glycosylation of secondary metabolites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W220–225. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Minotti G, Menna P, Salvatorelli E, Cairo G, Gianni L. Anthracyclines: molecular advances and pharmacologic developments in antitumor activity and cardiotoxicity. Pharmacological reviews. 2004;56:185–229. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kizek R, Adam V, Hrabeta J, Eckschlager T, Smutny S, Burda JV, Frei E, Stiborova M. Anthracyclines and ellipticines as DNA-damaging anticancer drugs: recent advances. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2012;133:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gewirtz DA. A critical evaluation of the mechanisms of action proposed for the antitumor effects of the anthracycline antibiotics adriamycin and daunorubicin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:727–741. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bellou S, Muenter M, Travers M, Leifer B, Baig S, Kramer C, Qi M, Joshi C, Carlson A, Conway C. Determination of Escherichia coli Genes Involved in Resistance to DNA Alkylating Agents. The FASEB Journal. 2016;30(1 Suppl) 789.3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.