ABSTRACT

Disulfide linkage is critical to protein folding and structural stability. The location of disulfide linkages for antibodies is routinely discovered by comparing the chromatograms of the reduced and non-reduced peptide mapping with location identification confirmed by collision-induced dissociation (CID) mass spectrometry (MS)/MS. However, CID product spectra of disulfide-linked peptides can be difficult to interpret, and provide limited information on the backbone region within the disulfide loop. Here, we applied an electron-transfer dissociation (ETD)/CID combined fragmentation method that identifies the disulfide linkage without intensive LC comparison, and yet maps the disulfide location accurately. The native protein samples were digested using trypsin for proteolysis. The method uses RapiGest SF Surfactant and obviates the need for reduction/alkylation and extensive sample manipulation. An aliquot of the digest was loaded onto a C4 analytical column. Peptides were gradient-eluted and analyzed using a Thermo Scientific LTQ Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer for the ETD-triggered CID MS3 experiment. Survey MS scans were followed by data-dependent scans consisting of ETD MS2 scans on the most intense ion in the survey scan, followed by 5 MS3 CID scans on the 5 most intense ions in the ETD MS2 scan. We were able to identify the disulfide-mediated structural variants A and A/B forms and their corresponding disulfide linkages in an immunoglobulin G2 monoclonal antibody with λ light chain (IgG2λ), where the location of cysteine linkages were unambiguously determined.

KEYWORDS: disulfide linkage, electron-transfer dissociation, collision-induced dissociation, monoclonal antibody, peptide mapping

Introduction

The formation of disulfide linkages is a common post-translational modification (PTM), involving cysteine oxidation, with potential for reshuffling through thiol (SH)-SS interchange reaction in an alkaline environment. Correct formation of disulfide linkages is essential for the folding and stability of most proteins, such as monoclonal antibodies (mAbs).1-4 Higher-order structure also plays a critical role in biological function, and can greatly be influenced by disulfide linkages. Incorrect formation of disulfide linkages can cause loss of efficacy of proteins.5-8 Knowledge of disulfide linkages could influence the development process for therapeutic proteins at various points from candidate selection to the manufacturing of a commercial product.9-12

Three subclasses of IgG antibodies, IgG1, IgG2 and IgG4, are typically developed as therapeutic antibodies. Each contains a total of 12 intra-chain disulfide bonds, but the subclasses differ in the number of inter-chain disulfide bonds (4 for IgG1 and IgG4; 6 for IgG2) in their classical structures.13-15 Inter-chain disulfide bonds are highly solvent exposed and more reactive, whereas intra-chain disulfide bonds are buried between the two layers of anti-parallel β-sheet structure within each domain, and thus are less reactive.16-19 Inter-chain disulfide bonds in human IgGs are susceptible to exchange in the presence of redox potential, such as in the whole blood, and vulnerable to degradation.4 Moreover, Dillon et al. reported that in a “blood-like” environment, such as during the commercial production of therapeutic IgG2 and subsequent purification steps, the inter-chain disulfide bonds at the hinge region interconverted and led to disulfide heterogeneity.1 In comparison, intra-chain disulfide bonds are less reactive to redox potential, but could be incompletely formed during cell culture. For example, Harris et al. reported IgG2 antibodies produced by a new cell line contain unpaired cysteine residues in the VH domain between C22 (H) and C96 (H).20,21 An antigen-binding fragment (Fab) containing unpaired cysteines exhibited reduced potency in an IgE-receptor binding inhibition assay.22 In addition, the majority of IgG1 dimers are attributed to the formation of inter-molecular disulfide bonds.23 Dimerization of IgG2 antibodies through disulfide bond formation was also reported under heat stress or agitation conditions.24,25 During therapeutic mAb product development, degradation or improper formation of disulfide bonds could lead to product heterogeneity and aggregation, as well as a significant decrease in potency. Administration of non-native disulfide bonded structures to patients might trigger immune response. Therefore, use of a comprehensive and accurate disulfide mapping method that characterizes all disulfides and establishes the presence of correct connectivity to assure drug function and quality is critical.

Disulfide linkages in mAbs are generally characterized by Edman sequencing or mass spectrometry (MS) with reduced and non-reduced conditions.26-30 MS is the most commonly used analytical tool for characterization of disulfide linkages in therapeutic proteins, due to its superior selectivity and sensitivity. In particular, disulfide linkages are conventionally characterized by peptide mapping with reduced and non-reduced conditions.26,31 The disappearance of the disulfide-linked peptides together with the appearance of corresponding new peaks in the reduced peptide maps compared to non-reduced mapping reveals the possible sites of disulfide linkages. Identification of the disulfide linkages are further confirmed by collision-induced dissociation (CID) MS/MS, where CID fragmentation spectra of the reduced peptides are screened for parent ions with m/z values corresponding to peptides containing one or more free SH groups.

One limitation of this combined chromatography comparison and CID fragmentation method is that it requires perfect alignment between the reduced and non-reduced peptide mapping. Differences in LC traces indicate the existence of potential disulfide linkages to be confirmed by CID fragmentation. CID fragmentation is not ideal for identifying disulfide-linked peptides, because it does not cleave the disulfide linkages and produces difficult-to-interpret product mass spectra of the disulfide-linked peptides.32 Moreover, in cases where intertwined disulfide linkages are involved, information regarding each disulfide linkage in the structure is lost during the reduced peptide mapping, and cannot be retrieved by CID fragmentation.

Electron-transfer dissociation (ETD) and electron-capture dissociation (ECD) are two alternative means of fragmentation that have shown preferential cleavage of disulfide bonds over backbone (N–Cα) fragmentation.32-34 Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for disulfide linkage cleavage in ETD and ECD. For example, the electron could be directly attached at a disulfide bond, assisted by positive charges in close proximity.35,36 Alternatively, when disulfide-linked peptides are subjected to ETD or ECD, an electron can first be transferred to/captured by the amine group close to a disulfide bond due to the higher electron affinity of the amine group, and then form a hydrogen atom. The hydrogen atom is then transferred to the disulfide bond, and induces breakage of the disulfide bond into a protonated (Cys-SH) and an odd electron (Cys-S•) form.37 Each disulfide-dissociated peptide could contain a mixed population, either as the Cys-SH or (Cys-S•) forms.

Multiple studies have leveraged ETD in the identification of disulfide bonds. For example, Wu et al.38 used online LC-MS with the ETD approach to identify disulfide linkages in therapeutic proteins such as human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibodies. Cole et al.39 applied the ETD method in the mapping of 13 intra-peptide disulfide bonds, with both N–Cα backbone cleavage and disulfide bond cleavage occurring in a single electron transfer event, followed by CID on selected product ions. Wang et al.40 applied a similar method in the identification of disulfide scrambling in IgG1 mAbs and an Fc fusion protein, and found that, under the same heat-stressed condition, less scrambling was generated in the fusion protein, which has no light chains but only two Fc chains, compared to the IgG1 mAbs.

IgG2λ contains three major disulfide isoform classes (A, A/B, and B isoforms), differing in their specific linkages between the Fab arms and the heavy chain hinge region.3 In the IgG2A form, the cysteine near the C-terminus of each light chain is linked to the Fab arms of the heavy chain. In the IgG2B form, both Fab arms are disulfide linked to the hinge, whereas only one Fab arm is disulfide linked to the hinge in the structural hybrid antibody IgG2A/B. Within the IgG2A form, two sub-isoforms IgG2A1 and IgG2A2 were further discriminated based on their different eluting order in non-reducing denaturing reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC); however, no differences in the disulfide binding pattern were observed between the two IgG2A sub-isoforms.41 The A and A/B isoforms are most abundant in IgG2λ, together with a negligible amount of B isoform according to the non-reducing RP-HPLC profile.41

Here, we have characterized the disulfide-mediated structural variants IgG2λ A and A/B isoforms and their disulfide linkages, including the shared six pairs of intra-chain and the distinct inter-chain disulfide linkages between two isoforms. We utilized RapiGest SF Surfactant and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to prepare a denatured and alkylated digest under non-reducing condition, performed the disulfide mapping by the ETD-triggered MS3 experimental paradigm, and analyzed the data by the Proteome Discoverer platform. The disulfide linkage in the disulfide-linked peptides is first broken by ETD in the MS2 step, with the disulfide-dissociated peptides being further characterized in the subsequent CID MS3 step. The ETD/CID MSn strategy unambiguously maps the disulfide linkage with less sample manipulation, is less vulnerable to chromatography noise, and yet more accurate and sensitive in the determination of disulfide linkages. We leveraged the nodes in the Proteome Discoverer framework, such as the SEQUEST search, to automatically generate a list of disulfide-dissociated peptides from the CID MS3 spectra. With the presented ETD method, in the case where only one of the peptides dissociated from the disulfide linkage is identified by the CID MS3 product spectrum, the complementary peptide can be determined using the identified disulfide-unlinked peptide with the loss of two hydrogens as a dynamic modification in the search of the ETD MS2 spectrum. The ETD MS/MS spectrum of the disulfide linked peptide could confidently be identified, and thus confirm the disulfide bond. The combination of the RapiGest SF Surfactant-assisted sample preparation, LC-MS with ETD/CID fragmentation, and the node-based data processing is unparalleled in its ability to comprehensively and unambiguously characterize disulfide linkages.

Results

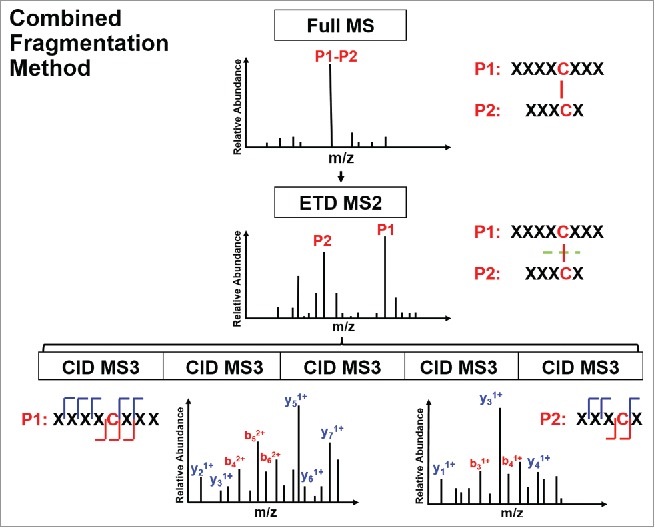

The schematic view of the presented ETD-triggered MS3 paradigm is shown in Figure 1. The IgG2λ mAb used in this study consists of two human heavy chains and two human λ light chains. The antibody was expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells, and purified by well-established chromatographic procedures developed at Amgen.42 The studied IgG2λ contained mainly the A and A/B isoforms, and a negligible amount of the B isoform, as quantified by non-reducing RP-HPLC profile.41 The A, A/B, and B disulfide isoform classes share the 12 common intra-chain disulfide linkages (one pair of each within the VH, VL, CL, CH1, CH2, and CH3 domain), and differ in the inter-chain disulfide linkages at the hinge region. Table 1 summarizes the disulfide-linked peptides of the three major disulfide isoform classes in the studied IgG2λ mAb and their mass to charge (m/z) ratios. In the table, “T” indicates that the peptide was digested by trypsin, whereas “H” or “L” refer to the resulting peptide originating from digestion of the heavy chain or light chain. The number aligns with the order of the theoretical peptide digest counting from the N-terminal. The first six disulfide-linked peptides in Table 1 represent the six pairs of intra-chain disulfide linkages shared between all isoforms, whereas the rest represent the distinct inter-chain disulfide linkages at the hinge region of each isoform.

Figure 1.

Schematic view of an electron transfer dissociation triggered MS3 paradigm.

Table 1.

Representative ions of disulfide-linked peptides of the three disulfide-mediated structural variants A, A/B, and B isoforms in IgG2λ.

| Intra-chain Disulfide-linked Peptides | Linked Cysteine | m/z |

|---|---|---|

| VH: [TH3-TH11]4+ | C22(H)-C96(H) | 838.63 |

| VL: [TL2-TL6]4+ | C22(L)-C89(L) | 1504.19 |

| CL: [TL10-TL16]5+ | C138(L)-C197(L) | 762.38 |

| CH1: [TH16-TH17]8+ | C157(H)-C213(H) | 1010.12 |

| CH2: [TH23-TH28]4+ | C270(H)-C330(H) | 998.22 |

| CH3: [TH36-TH41]5+ |

C376(H)-C434(H) |

770.37 |

| Inter-chain Disulfide-linked Peptides |

Linked Cysteine |

m/z |

| A:[TH21-TH21^]5+ | C232(H)-C232(H)^; C233(H)-C233(H)^; C236(H)-C236(H)^; C239(H)-C239(H)^ | 1071.72 |

| A:[TL17-TH15]3+ | C215(L)-C144(H) | 679.33 |

| A/B:[TH15-TH21^-TH21-TL17]5+ | C215(L)-C232(H); C232(H)^-C144(H); C233(H)-C233(H)^; C236(H)-C236(H)^; C239(H)-C239(H)^; | 1477.90 |

| B: [TH15-TL17^-TH21^-TH21-TL17-TH15^]6+ | C215(L)-C232(H); C233(H)-C144(H)^; C236(H)-C236(H)^; C239(H)-C239(H)^; | 1570.74 |

^Peptide on another heavy chain.

A: Distinct disulfide-linked peptides in IgG2A isoform.

A/B: Distinct disulfide-linked peptides in IgG2A/B isoform.

B: Distinct disulfide-linked peptides in IgG2B isoform.

CID mainly cleaves peptide amide bones to produce b and y ions. The CID spectra of disulfide-linked peptides are typically difficult to interpret and provide limited information for the backbone region within the disulfide loop. Alternatively, ETD cleaves the NH-Cα bond to produce c and z ions, and favors fragmentation of disulfide linkages. Specifically, ETD breaks the disulfide bond to produce two polypeptides, labelled as a free cysteine-containing peptide for one polypeptide and a free cysteine-containing peptide with an odd electron replacing its proton as the other polypeptide. A sequential CID on the disulfide-dissociated peptides from the ETD scan produces b and y ions for the entire backbone region. In this study, we digested the IgG2λ using trypsin without reduction, and then identified the disulfide linkages by the combined ETD/CID fragment method.

Identification of common intra-chain disulfide linkages

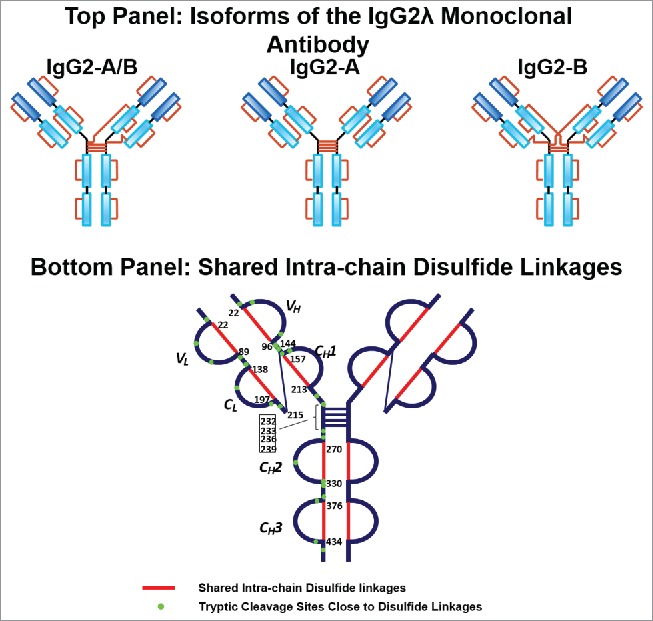

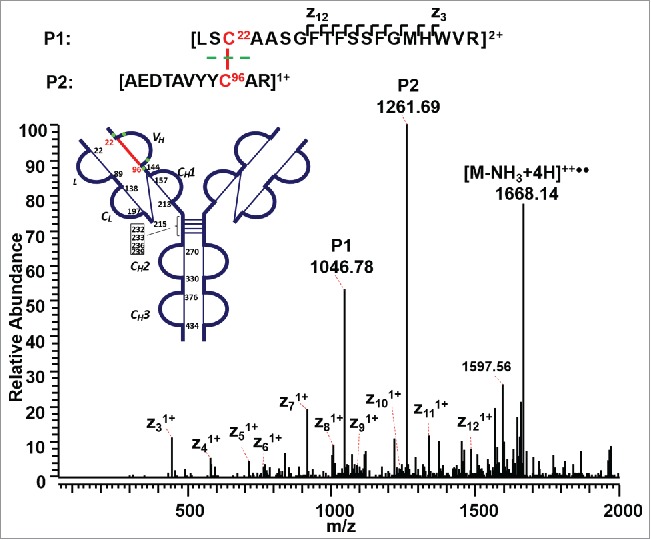

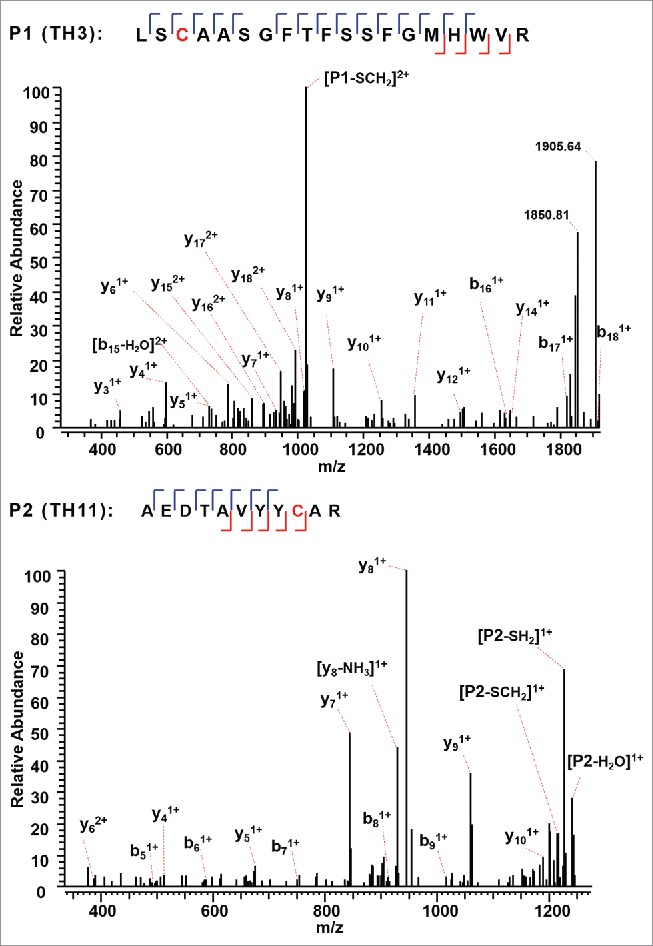

The A, A/B, and B isoforms of the IgG2λ mAb shared six pairs of common intra-chain disulfide bonds, as shown in the top panel of Figure 2. The six pairs of intra-chain disulfide linkages are marked in red in the bottom panel of Figure 2, with the sites of cysteines numbered, residing in the VH, VL, CL, CH1, CH2, and CH3 domain. Tryptic cleavages sites close to the location of disulfide linkages are highlighted. To determine the disulfide linkage, for example, the disulfide-linked peptide within the VH domain (m/z 838.629, 4+) was selected from the MS scan for ETD MS2 (Supplementary Figure 1 and Figure 3). The disulfide bond dissociated, and produced separate peptide ions P1 (m/z 1046.78, 2+) and P2 (m/z 1261.69, 1+), along with a typical ETD fragmentation pattern of the backbone cleavages with several high-intensity ions of the charge-reduced species of the precursor ion. Due to the cleavage of disulfide linkage during the ETD MS2, the ions corresponding to the unlinked peptides were automatically selected for CID MS3 (Figure 4). ETD favors the cleavage of disulfide bonds; therefore, the P1 and P2 ions were observed as the two highest intensity ions in the ETD spectrum, along with a typical ETD fragmentation pattern of the backbone cleavages (z ions) with high-intensity ions consisting of charge-reduced species of the precursor ion, such as [M-NH3+4H]++••. The loss of NH3 from the N-terminus is due to the NH-Cα bond at the N-terminus.34,38,43 P1 and P2 were automatically isolated and fragmented into b and y ions in the CID MS3 step, along with characteristic side-chain losses of amino acid residues, such as loss of 18 (water), 34 (SH2), or 46 Da (SCH2) from the cysteine residue. This result suggests the peptide contained a mixed population, such as P1-SH and P1-S•, with the protonated form producing b and y ions, and the odd-electron form producing characteristic side-chain losses of SH2 and SCH2. Similar observations of the side chain losses have been described by others.38,43 Only one fragment ion was missing for CID MS3 spectra of both P1 and P2 to be sequenced at 100%. The disulfide-linked peptide P1-P2 was confirmed to be TH3-TH11, connected by the disulfide bond between cysteines C22 (H) and C96 (H).

Figure 2.

Top panel: Three major disulfide isoform classes, A, A/B, and B isoforms, in the IgG2λ monoclonal antibody. Bottom panel: The shared six pairs of intra-chain disulfide linkages between all isoforms are highlighted in red, and the tryptic cleavages sites close to disulfide linkages are marked in green.

Figure 3.

ETD MS2 spectrum of intra-chain disulfide linked peptide within the VH domain. ETD dissociated the two peptides linked by a disulfide bond, producing intense fragments corresponding to the unlinked peptides, along with a typical ETD fragmentation pattern of the backbone cleavage, as well as the high-intensity ion of the charge-reduced species of the precursor ion.

Figure 4.

CID MS3 spectra of the disulfide-dissociated peptides TH3 (top) and TH11 peptides (bottom) within the VH domain. Only one fragment ion was missing for both CID MS3 spectra of TH3 and TH11 to achieve an MS3 sequence coverage of 100%. Both C22 (H) and C96 (H) residues were surrounded by fragment ions, and thus the location of disulfide linkages were unambiguously identified.

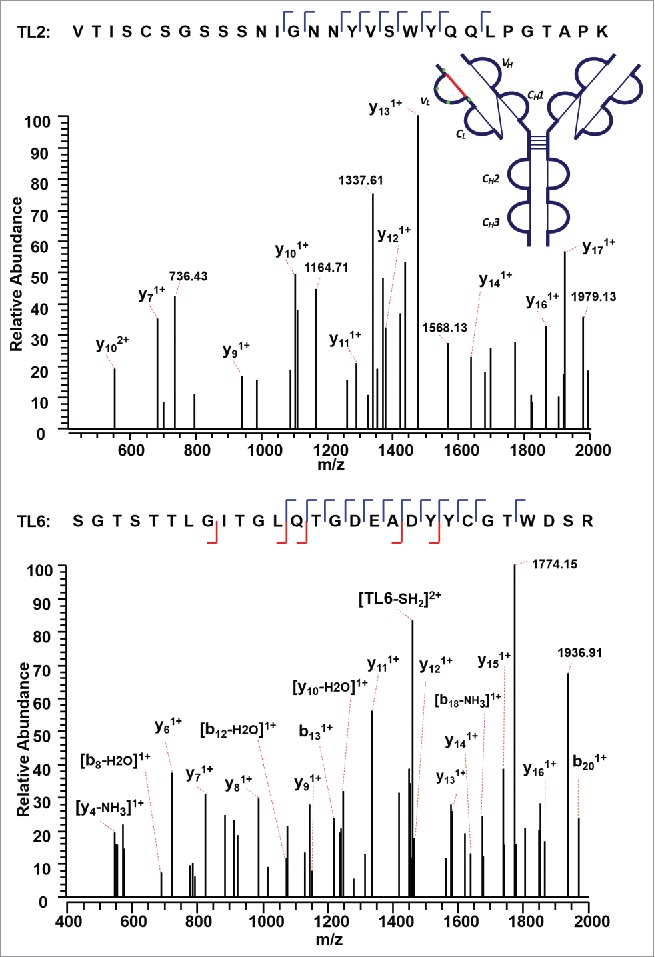

Figure 5 shows a second disulfide-linked peptide, connected through an intra-disulfide bond between C22 (L) and C89 (L) in the VL domain of the IgG2λ. The precursor ion (m/z 1504.19, 4+) was subjected to ETD MS2, yielding a typical ETD fragmentation pattern, along with two high-intensity ions TL2 (m/z 1530.91, 2+) and TL6 (m/z 1478.41, 2+) (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). Both ions are automatically fragmented in the MS3 step, with a typical CID fragmentation pattern (b and y ions), along with several side-chain losses of amino acid residues. Consecutive y ions are identified in the CID MS3 product spectrum of the peptide TL2, which could serve as an anchor to aid in the confident identification of the disulfide-dissociated peptide TL2. In the CID MS3 product spectrum of the complementary peptide TL6 generated upon dissociation of the disulfide bond, consecutive y ions were also observed, including y ions surrounding C89 (L), confirming its identity with high confidence at the amino acid level. Both peptides were found to contain one cysteine, and thus the linkage between C22 (L) and C89 (L) was assigned.

Figure 5.

CID MS3 spectra of the disulfide-dissociated peptides TL2 (top) and TL6 peptides (bottom) within the VL domain. The C89 residue in TL6 was identified by MS3 spectrum with high confidence. The identity of TL2 was confirmed by the mass difference between the disulfide-linked peptide and the disulfide-dissociated peptide. The partial MS3 sequence coverage further confirmed the linkage between C22 (L) and C89 (L).

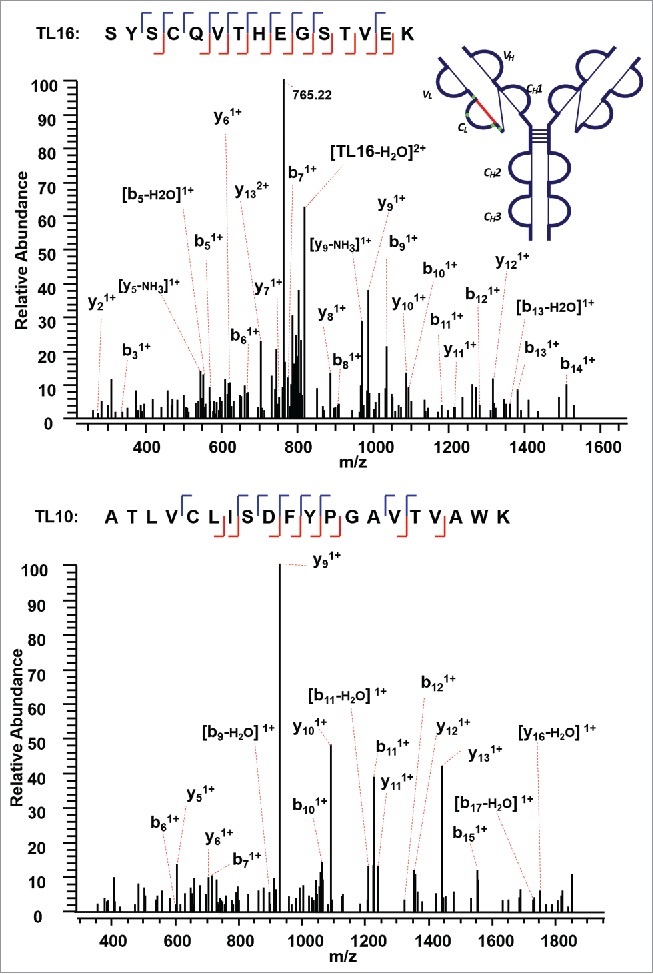

The next disulfide-associated peptide we examined with the presented approach is between C138 (L) and C197 (L) on tryptic peptides TL10 and TL16 in the CL domain. In the MS2 step, the precursor ion of the disulfide linked peptide (m/z 762.38, 5+) was isolated and dissociated as high abundant TL10 (m/z 1077.91, 2+) and TL16 ions (m/z 827.79, 2+) (Supplementary Figures 4 and 5). Figure 6 shows the CID product spectrum of each disulfide-dissociated peptide, where all the amino acids in the peptide TL16 are confidently identified by surrounding b or y ions, except for amino acid residues “SY”. Fragment ions were identified on both sides of cysteine in the CID MS3 product spectrum of TL16, and confirmed one end of the disulfide linkage to be cysteine C197 with a high confidence. Similarly, b and y ions in another CID MS3 spectrum identify the complementary peptide of the disulfide-linked peptide to be TL10. The two identified CID MS3 spectra confirm the disulfide linkage between C138 (L) and C197 (L) with confidence.

Figure 6.

CID MS3 spectra of the disulfide-dissociated peptides TL16 (top) and TL10 peptides (bottom) within the CL domain. Fragment ions were identified on both sides of cysteine in the CID MS3 product spectrum of TL16, and confirmed one end of the disulfide linkage to be cysteine C197 with a high confidence. The fragment ions in the bottom CID MS3 spectrum identified the complementary peptide to be TL10, and confirmed the linkage between C138 (L) and C197 (L).

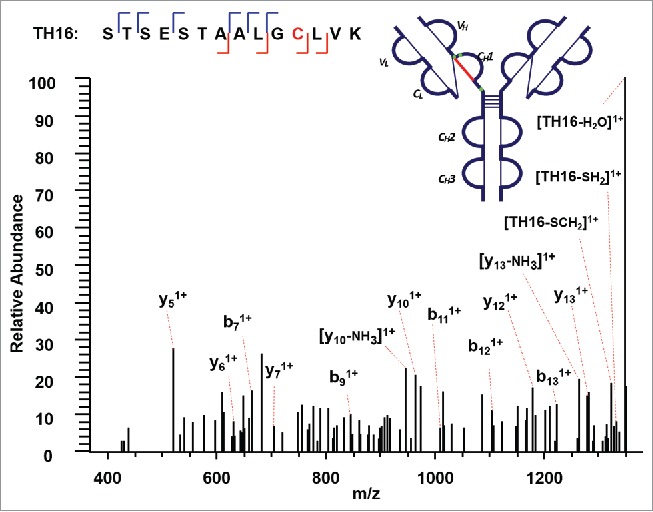

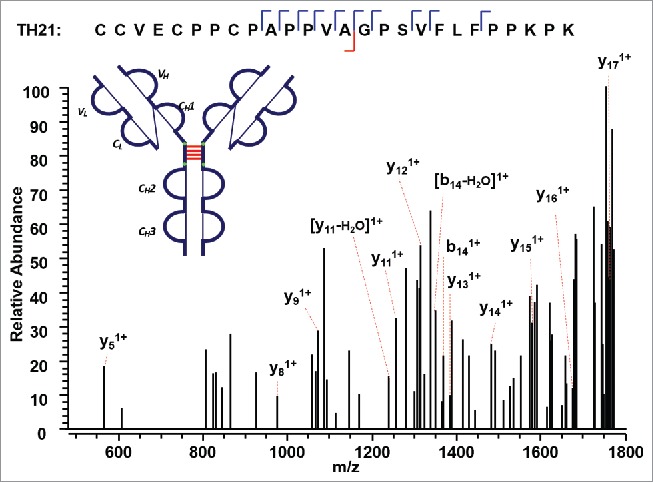

Switching to the next disulfide-linked peptide, connected through another intrachain disulfide bond between C157(H) and C213(H) within the CH1 domain, a precursor ion (m/z 1010.12, 8+) was detected and ETD fragmented (Supplementary Figures 6 and 7); however, only the CID MS3 product spectrum for one disulfide-dissociated peptide TH16, where C157(H) resides, was observed (Figure 7). Characteristic side-chain losses from the cysteine residues again were observed in the CID MS3 step due to the presence of odd-electron form of peptide TH16. The protonated TH16 was found to be fragmented into b and y ions, confirming the identity and linkage site at C157(H). To find the complementary peptide upon the dissociation of a disulfide bond, the cysteine residue in the target counterpart would be assumed to be modified with the molecular mass of the identified disulfide-dissociated peptide. For example, in this case, the molecular mass of TH16 with the loss of two hydrogens [M-2H] serves as a dynamic modification when searching against ETD MS2 spectra using SEQUEST. The other chain of the disulfide-linked peptide was identified to be peptide TH17. The absence of disulfide-dissociated peptide ion TH17 from the ETD MS2 spectra, and the subsequent CID MS3 product spectra could be explained if the disulfide-dissociated peptide TH17 (6705 Da) existed as 3+, 2+, or 1+ charge state (m/z >2000), which is beyond the mass detection window. The SEQUEST search was then repeated using peptide TH17 as a dynamic modification against ETD MS2 spectra, and confirmed the complementary chain to be TH16. The linkage between TH16 and TH17 through C157(H) and C213(H) was thus assigned.

Figure 7.

CID MS3 spectrum of the disulfide-dissociated peptide TH16 within the CH1 domain. TH16 was identified by Proteome Discoverer as a reduced peptide resulting from disulfide cleavage. There are multiple fragment ions serving as anchors to aid in confident identification of peptide segment. To find its complementary peptide in the disulfide-linked peptide, the molecular mass of TH16 with the loss of two hydrogens [M-2H] serves as a dynamic modification when searching against ETD MS2 spectra using SEQUEST. The counterpart in the disulfide-linked peptide was identified as TH17, linked by disulfide bond between C157 (H) and C213 (H).

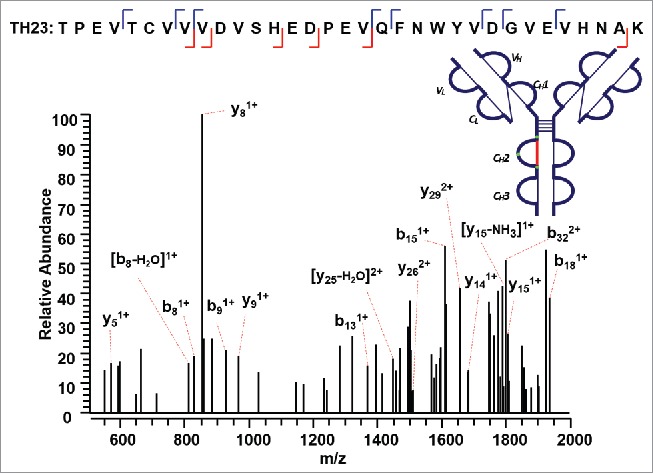

We then used our method to map the disulfide bond between a 33 amino acid long peptide containing a cysteine residue and its complementary disulfide bonded peptide within the CH2 domain (Supplementary Figures 8 and 9). ETD MS2 data of the precursor ion (m/z 998.22, 4+) produced a single CID MS3 identified sequence TH23 (m/z 1871.79, 2+) (Figure 8). The mass of the complementary peptide was calculated based on the difference between the precursor ion and the identified disulfide-dissociated TH23. The other chain was confirmed to be a dipeptide TH28 (249 Da). Notably, TH28 was not detected in the reduced tryptic peptide mapping of this IgG2A mAb, possibly because its fragment ions were below the mass detection range. The combined ETD/CID dissociation method shows the capability to discover unidentified peptide in the conventional reduced peptide mapping by the mass difference between the precursor ion for ETD MS2 and the identified peptide by the CID MS3 data.

Figure 8.

CID MS3 spectrum of the disulfide-dissociated peptide TH23 within the CH2 domain. TH23 was identified by Proteome Discoverer as a reduced peptide resulting from disulfide cleavage with multiple fragment ions serving as anchors to aid in confident identification of peptide segment. The dipeptide TH28 was confirmed to be the complementary peptide based on the mass difference between the disulfide-linked peptide and the identified disulfide-dissociated TH23, leading to the identification of disulfide linkage between C270 (H) and C330 (H).

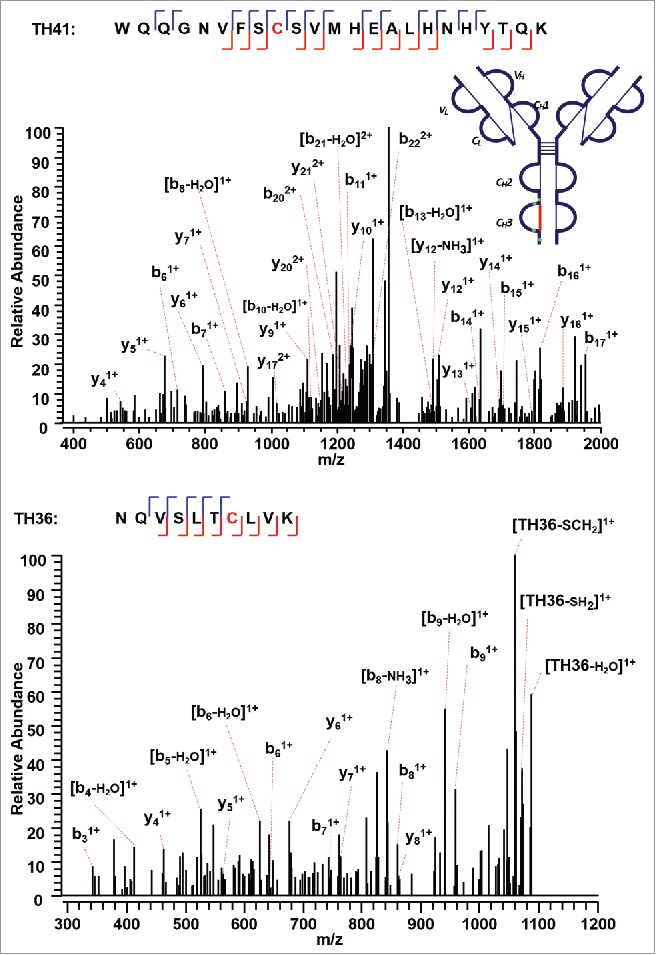

The approach found the last intra-chain disulfide-linked peptide between C376 (H) and C434 (H) in the CH3 domain (Figure 9). In the MS2 step, the precursor ion of the disulfide linked peptide (m/z 770.37, 5+) was isolated and dissociated as high abundant TH41 (m/z 1373.49, 2+) and TH36 ions (m/z 1104.74, 1+) (Supplementary Figures 10 and 11). High sequence coverage was observed for both CID MS3 spectra, with adjacent fragment ions on both sides of cysteines C376 (H) and C434 (H). Both cysteines were identified with high confidence, and the MS3 sequence coverage for the two chains (TH36 and TH41) is 90% and 74%. The ETD MS2 spectrum together with two identified CID MS3 spectra confirm this intra-chain disulfide linkage with very high confidence.

Figure 9.

CID MS3 spectra of the disulfide-dissociated peptides TH41 (top) and TH36 peptides (bottom) within the CH3 domain. One or five fragment ions were missing for TH36 or TH41 to achieve a CID MS3 sequence coverage of 100%. Both C376 (H) and C434 (H) residues were identified by high confidence, and thus the location of disulfide linkages were unambiguously identified.

Identification of inter-chain disulfide linkages

The three major classes of disulfide-mediated structural isoforms (A, A/B, and B isoforms) in IgG2λ differ in their specific linkages between the Fab arms and the heavy chain hinge region. RP-HPLC profiles of IgG2λ show that IgG2λ contains mainly the A isoform, a relatively lower level of the A/B isoform, and a negligible level of the B isoform.41 We only observed one disulfide pattern for the IgG2A form, supporting the report from Liu et al. that the A1 and A2 sub-isoforms share the same disulfide pattern.41

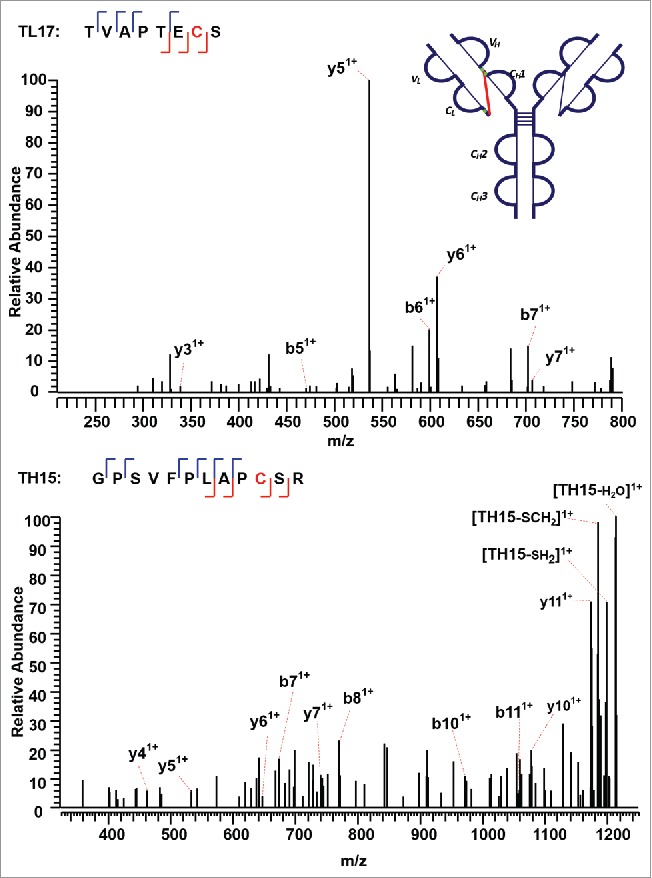

The IgG2A isoform consists of four inter-chain disulfide bonds restricted within the hinge region, and a pair of inter-chain disulfide bonds between the CL and CH1 domain. The tryptic peptide TH21 contains four cysteine sites, C232 (H), C233 (H), C236 (H), and C239 (H). The TH21 from one heavy chain was found to form disulfide linkages with the TH21 on the other heavy chain (TH21^). ETD cleaves the disulfide chain between the disulfide-associated peptide TH21-TH21^ (m/z 1071.72, 5+), producing two identical unlinked peptides, which results in a single peak related to the disulfide-unlinked peptide in the ETD MS2 spectrum (Supplementary Figures 12 and 13). The single peak was isolated and fragmented in the subsequent CID MS3 spectrum (Figure 10). Notably, for disulfide bound pairs of two identical peptides, only one new peak would be observed in the reduced peptide mapping corresponding to the disappearance of the disulfide-associated peptides. Similarly, only one CID product spectrum data is available for the disulfide-unlinked peptides. The linkage could be assigned by comparing the mass difference between the precursor mass selected for ETD MS2 and the identified unlinked peptide. By determining the mass difference of ions in the consecutive ETD MS2 and CID MS3 scans, we were able to identify the linkages between two TH21 peptides. In addition, Figure 11 shows the other distinct inter-chain disulfide linkages between peptides TL17 and TH15 within the CL and CH1 domain of the IgG2A isoform. The precursor ion (m/z 679.33, 3+) was subjected to ETD MS2, yielding a typical ETD fragmentation pattern, along with two high-intensity ions TL17 (m/z 807.49, 1+) and TH15 (m/z 1230.79, 1+) (Supplementary Figures 14 and 15). The CID MS3 sequence coverage is nearly complete for the MS3 of peptide TL17, whereas that of peptide TH15 lacks three fragment ions to be 100%. The presence of two fragment ions on both sides of an amino acid results in C215 (L) identified with high confidence. The peptide identified with such a high confidence could be used to check the final identification of the matching peptide.

Figure 10.

CID MS3 spectrum of the distinct disulfide-dissociated peptide TH21 at the hinge region of the IgG2A isoform. TH21 on one heavy chain was found to connect with TH21 on the other heavy chain, and formed the inter-chain disulfide bond.

Figure 11.

CID MS3 spectra of the disulfide-dissociated peptides TL17 (top) and TH15 peptides (bottom) across the CL and CH1 domain. TL17 is at the C-terminal of the light chain of the mAb, ending with S. Three or one fragment ion was missing for CID MS3 spectrum of TH15 or TL17 to achieve an MS3 sequence coverage of 100%. Both C144 (H) and C215 (L) residues were identified by high confidence, and thus the location of disulfide linkages were unambiguously identified.

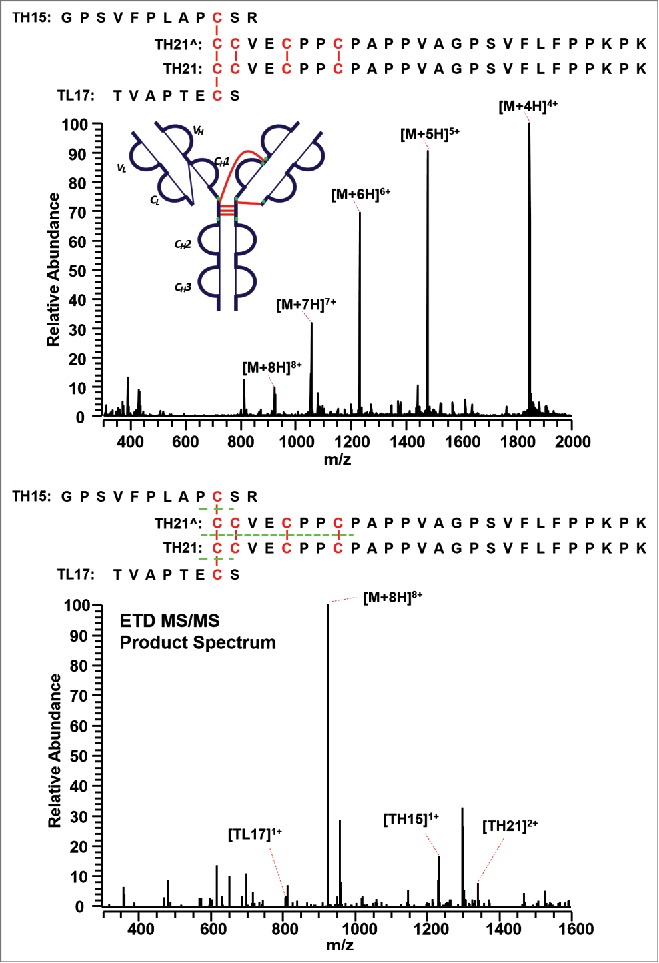

The IgG2A/B isoform consists of a specific disulfide-linked peptide between the CH1, hinge region, and the CL domain. Figure 12 shows the MS1 (top panel) and MS2 (bottom panel) spectra of the distinct disulfide-linked peptide between the hinge region and one Fab arm in the IgG2A/B isoform. Although a good MS3 CID spectrum is yet to be observed, the MS1 spectrum was detected with good confidence, and the subsequent ETD product spectrum presented the disulfide-dissociated peptides to be TL17, TH15, and TH21 based on the mass. No product mass spectrum of the disulfide-linked peptide between the hinge region and both Fab arms was observed to confirm an IgG2B isoform, possibly due to the low abundance of IgG2B isoforms. Enrichment of the IgG2B isoform is required to detect its distinct disulfide linkages.

Figure 12.

MS1 (top) and MS2 (bottom) spectra of the distinct disulfide-linked peptide between the hinge region and one Fab arm in the IgG2A/B isoform. Full MS spectrum confirms the existence of the linked peptide, whereas the ETD MS/MS product spectrum shows the identity of the unlinked peptides.

Discussion

Current disulfide linkage mapping based on chromatography comparison and CID fragmentation only for structural variants has several limitations. First, most non-reduced peptide mapping experiments start with the digested and non-alkylated samples under non-reducing condition. The samples, however, are vulnerable to pH change and prone to disulfide scrambling. Here, we denatured and alkylated the mAb IgG2λ under non-reducing conditions using NEM at mildly acidic pH in RapiGest. This step irreversibly labels any free cysteines present in the sample, and helps control disulfide-rearrangement during the procedure. RapiGest is cleaved into insoluble components at low pH, and removed by centrifugation. Then, normal separation by HPLC and mass analysis by mass spectrometry is performed.

Second, disulfide linkages are commonly determined by correlating the disappearance of the disulfide-linked peptides with the appearance of the corresponding unlinked peptides in the reduced peptide mapping. The correlation obviously requires a perfect alignment of LC traces between the reduced and non-reduced peptide mapping. However, the reduction of disulfide linkages does not always lead to a shift of retention time; thus, the potential location of disulfide linkages could not be confirmed by CID MS2 product spectra without the presence of a new peak in the reduced peptide mapping. For example, in the case of internally disulfide-linked peptides, the disulfide-linked and disulfide-dissociated peptides elute closely,44 and the mass shift in MS1 peak of a possible “disulfide-linked” peptide can be misinterpreted as the isotopic distribution. Therefore, it is hard to conclude whether there is an internal disulfide linkage based on the LC traces and CID MS2 data. Our methodology does not depend on the comparison of LC traces to locate potential disulfide linkages. ETD MS2 cleaves the intra-peptide disulfide bond, and produces a reduced single peptide that can be sequenced based on its CID MS3 product spectrum with no ambiguity. Furthermore, for the peptide containing intra-peptide disulfide linkages only, the mass difference between the precursor ion and the fully reduced peptide ion in the ETD MS2 spectrum can be used to deduce the number of disulfide linkages.

Finally, current practice requires the CID product spectra of both dissociated peptides from a disulfide-associated peptide. With our ETD method, when only one of the peptides dissociated from the disulfide linkage is identified by the CID MS3 product spectrum, the complementary peptide can be identified by using the identified disulfide-unlinked peptide with the loss of two hydrogens as a dynamic modification in the search of the ETD MS2 spectrum.

It is common to get high false positives rates when sequencing the disulfide-dissociated peptides by the SEQUEST node in Proteome Discoverer. For example, a polypeptide not containing cysteine was output as a possible component of a disulfide-associated peptide. The high false positives rates are due to the limited size of the database, which is commonly composed of the sequence of the interested protein only. Increasing the size of the database by adding more irrelevant sequences could help decrease the false positives rates. Alternatively, algorithms that could predict a list of all possible disulfide-linked peptides could be leveraged to match the MS1 precursors selected for ETD and assign the identities. For complicated proteins, it is highly possible that more than one disulfide-linked peptide could match to a given precursor. The CID MS3 spectrum could be used to verify the identity of the disulfide-dissociated peptides. Such an integrated approach will be extremely powerful for identification of both known and new disulfide linkages in proteins.

Another excellent application of the ETD method is to determine intertwined disulfide linkages, such as two disulfide linkages between three peptides. Conventional methods use chemical reduction such as dithiothreitol, which fully cleaves the three disulfide-linked peptide into three separate peptides. Although the backbone sequence information can be generated from the product MS spectrum of each completely disulfide-dissociated peptides, information regarding each disulfide linkage in an intertwined disulfide structure is lost. Alternatively, ETD could generate partially dissociated peptides with high abundance to facilitate identification of complex disulfide linkages.

In conclusion, our methodology leverages denatured and alkylated tryptic digests under non-reducing condition, ETD-triggered MS3 experimental paradigm, and the Proteome Discoverer platform for disulfide mapping. Alkylating the free thiol eliminates possible method-induced disulfide shuffling, and enables discovery of the native disulfide location. We successfully identified and confirmed all the common intra-chain and the distinct inter-chain disulfide linkages between the A and A/B isoforms in a mAb IgG2λ, with the relative high abundant ions observed in ETD MS2 spectrum providing strong evidence of the linked peptides. Data analysis was empowered by the Proteome Discoverer to identify the disulfide-dissociated peptides, whereas the product spectrum and coverage map were shown to present the efficiency of fragmentation. Due to the lower intensity of ETD MS2 and subsequent CID MS3 product ions, the current method requires a large amount of purified proteins for identification of disulfide linkages. The approach presented here could be applied to identify the disulfide linkages in protein mixtures as long as there is sufficient digested material. For the data analysis of complex protein mixtures, such as proteome samples containing thousands of proteins, it is likely that the noise of numerous random matches of inter-protein disulfide bonds would make it difficult to identify a small number of intra-protein disulfide bond matches. Disulfide linkages between different proteins are extremely rare.29 It is recommended to filter the intra-protein and inter-protein disulfide linkages separately, and adjust the false discovery rate for intra-protein disulfide linkages accordingly.

Materials and methods

Materials

The mAb IgG2λ was produced at Amgen Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA), and consisted of two human gamma heavy chains and two human λ light chains. The antibody was expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells, and purified by well-established chromatographic procedures developed at Amgen.42 RapiGest SF surfactant was purchased from Waters (Milford, MA). Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and guanidine hydrochloride solution were obtained from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA). Lyophilized trypsin was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). NEM was obtained from Calbiochem (Billerica, MA).

Alkylation and trypsin digestion of protein

The mAb IgG2λ was concentrated by Centricon tube or diluted to 5 mg/mL in 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.2, 5% (w/v) sorbitol. Prior to digestion, the free cysteine residues of the sample were blocked by incubating with 6.0 µL of 20% RapiGest solution and 1.0 µL of 15 mM NEM solution added to 50 µL of sample at 78°C for 10 min. Every 45 µL of the alkylated sample was digested with 20 µg of trypsin at 37°C for 17 hours. TFA was then added to quench the enzymatic reaction and degrade the RapiGest.

Data acquisition: On-line LC CID MS1, ETD MS2, and CID MS3

Each tryptic digest (∼30 µg) was subjected to nano flow RP-HPLC separation by Waters Acuity ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography system (Milford, MA), and mass detection by Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (San Jose, CA) equipped with electrospray ionization source. Enzymatic digests were separated by Waters BEH C4 column (2.1 × 150 mm 300 Å pore size) at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min with the column temperature maintained at 60°C. Mobile phase A was 0.08% (v/v) TFA in water, and mobile phase B was 0.07% (v/v) TFA in 80% acetonitrile. Beginning with 0% mobile phase B, phase B linearly increased to 50% after 60 min and to 95% at 63 min. After washing at 95% for 3 min, the column was equilibrated with 0% B for 5 min.

Tryptic digests were electrosprayed at 4 kV and injected into a Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (San Jose, CA). Precursor ions were isolated in the ion trap with an isolation window width of 3 Th, followed by ETD fragmentation for a reaction time of 100 ms. Figure 1 shows the general survey scheme of the mass spectrometer, which was operated in the data-dependent mode to switch automatically between MS, ETD-MS2, and CID of isolated species in the MS3 steps. For the MS survey scans, the scan range was set to 200–2000 m/z at a mass resolving power (m/Δm50%, in which Δm50% is the full absorption-mode mass spectral peak width at half-maximum peak height) of 60,000 at m/z 400, and the automatic gain control (AGC) target was set to 1 × 106. For the MS/MS scans, the AGC target was set to 1 × 105, and the maximum injection was set to 500 ms. Each precursor ion for the ETD scans was isolated using the data-dependent acquisition mode with an isolation window width of 3 Th to select automatically and sequentially a specific ion (starting with the most intense ion) from the first MS scan. The 5 most abundant ions from the prior ETD spectrum were selected for further CID fragmentation in the CID MS3 step. The mass spectra were externally calibrated by Pierce LTQ Velos ESI positive ion calibration solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA).

LC/MSE data were processed and searched against in-house developed software MassAnalyzer,45 and disulfide linkages were confirmed by Thermo Scientific Proteome Discoverer 1.4 software with SEQUEST node. ETD MS2 and CID MS3 spectra were separated with the “Scan Event Filter” (node #2 for ETD and node #6 for CID spectra) using the fragmentation type for differentiation and the order of scan event. “None-Fragment Filter” (node #3) removes the precursor-related peaks in the mass list, and increases search confidence and reduction of false positive identification.46,47 The “None-Fragment Filter” node was used with the following parameters: remove precursor, 1-Da window offset; remove charge reduced precursor, 0.5-Da window offset; and remove neutral loss form charge reduced precursor, 0.5-Da window offset. ETD MS2 spectra were searched by SEQUEST® (node #4), and the following CID MS3 spectra were searched using SEQUEST® (node #7). In the cases where only one chain form the disulfide-linked peptide was identified by CID MS3, the detected peptides with the loss of two hydrogens were searched again as a dynamic modification against the ETD MS2 spectra to find the matching peptide.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- CID

collision-induced dissociation

- ETD

electron-transfer dissociation

- Fab

antigen-binding fragment

- IgG2λ

immunoglobulin G2 monoclonal antibody with λ light chain

- LC

liquid chromatography

- mAbs

monoclonal antibodies

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

- RP-HPLC

reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenzhou Li, Da Ren, and Zhongqi Zhang for their critical review of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Dillon TM, Ricci MS, Vezina C, Flynn GC, Liu YD, Rehder DS, Plant M, Henkle B, Li Y, Deechongkit S, et al.. Structural and functional characterization of disulfide Isoforms of the human IgG2 subclass. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16206–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709988200. PMID:18339626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mamathambika BS, Bardwell JC. Disulfide-linked protein folding pathways. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:211–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175333. PMID:18588487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wypych J, Li M, Guo A, Zhang Z, Martinez T, Allen MJ, Fodor S, Kelner DN, Flynn GC, Liu YD, et al.. Human IgG2 antibodies display disulfide-mediated structural isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16194–205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709987200. PMID:18339624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu YD, Chen X, Enk JZ-v, Plant M, Dillon TM, Flynn GC. Human IgG2 antibody disulfide rearrangement in Vivo. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29266–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804787200. PMID:18713741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machino Y, Ohta H, Suzuki E, Higurashi S, Tezuka T, Nagashima H, Kohroki J, Masuho Y. Effect of immunoglobulin G (IgG) interchain disulfide bond cleavage on efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin for immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;162:415–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04255.x. PMID:21029072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAuley A, Jacob J, Kolvenbach CG, Westland K, Lee HJ, Brych SR, Rehder D, Kleemann GR, Brems DN, Matsumura M. Contributions of a disulfide bond to the structure, stability, and dimerization of human IgG1 antibody C(H)3 domain. Protein Sci. 2008;17:95–106. doi: 10.1110/ps.073134408. PMID:18156469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Neut Kolfschoten M, Schuurman J, Losen M, Bleeker WK, Martínez-Martínez P, Vermeulen E, den Bleker TH, Wiegman L, Vink T, Aarden LA, et al.. Anti-inflammatory activity of human IgG4 antibodies by dynamic fab arm exchange. Science. 2007;317:1554–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1144603. PMID:17872445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Labrijn AF, Buijsse AO, van den Bremer ETJ, Verwilligen AYW, Bleeker WK, Thorpe SJ, Killestein J, Polman CH, Aalberse RC, Schuurman J, et al.. Therapeutic IgG4 antibodies engage in Fab-arm exchange with endogenous human IgG4 in vivo. Nat Biotech. 2009;27:767–71. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kao Y-H, Hewitt DP, Trexler-Schmidt M, Laird MW. Mechanism of antibody reduction in cell culture production processes. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;107:622–32. doi: 10.1002/bit.22848. PMID:20589844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullan B, Dravis B, Lim A, Clarke A, Janes S, Lambooy P, Olson D, O'Riordan T, Ricart B, Tulloch AG. Disulphide bond reduction of a therapeutic monoclonal antibody during cell culture manufacturing operations. BMC Proc. 2011;5:P110–P. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S8-P110. PMID:22373255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruaudel J, Bertschinger M, Letestu S, Giovannini R, Wassmann P, Moretti P. Antibody disulfide bond reduction during process development: insights using a scale-down model process. BMC Proc. 2015;9:P24–P. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-9-S9-P24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trexler-Schmidt M, Sargis S, Chiu J, Sze-Khoo S, Mun M, Kao Y-H, Laird MW. Identification and prevention of antibody disulfide bond reduction during cell culture manufacturing. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;106:452–61. PMID:20178122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelman GM, Poulik MD. Studies on structural units of the γ-Globulins. J Exp Med. 1961;113:861–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.113.5.861. PMID:13725659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pink JRL, Milstein C. Inter heavy–light chain disulphide bridge in Immune Globulins. Nature. 1967;214:92. doi: 10.1038/214092a0. PMID:4166384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu H, May K. Disulfide bond structures of IgG molecules. mAbs. 2012;4:17–23. doi: 10.4161/mabs.4.1.18347. PMID:22327427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kikuchi H, Goto Y, Hamaguchi K. Reduction of the buried intrachain disulfide bond of the constant fragment of the immunoglobulin light chain: global unfolding under physiological conditions. Biochemistry. 1986;25:2009–13. doi: 10.1021/bi00356a026. PMID:3085710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amzel a LM, Poljak RJ. Three-dimensional structure of immunoglobulins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1979;48:961–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.004525. PMID:89832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lefranc M-P, Pommié C, Kaas Q, Duprat E, Bosc N, Guiraudou D, Jean C, Ruiz M, Da Piédade I, Rouard M, et al.. IMGT unique numbering for immunoglobulin and T cell receptor constant domains and Ig superfamily C-like domains. Dev Comp Immunol. 2005;29:185–203. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2004.07.003. PMID:15572068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lefranc M-P, Pommié C, Ruiz M, Giudicelli V, Foulquier E, Truong L, Thouvenin-Contet V, Lefranc G. IMGT unique numbering for immunoglobulin and T cell receptor variable domains and Ig superfamily V-like domains. Dev Comp Immunol. 2003;27:55–77. doi: 10.1016/S0145-305X(02)00039-3. PMID:12477501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaderjian WB, Chin ET, Harris RJ, Etcheverry TM. Effect of copper sulfate on performance of a serum-free cho cell culture process and the level of free thiol in the recombinant antibody expressed. Biotechnol Progr. 2005;21:550–3. doi: 10.1021/bp0497029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris RJ. Heterogeneity of recombinant antibodies: linking structure to function. Dev Biol. 2005;122:117–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris RJ, Chin ET, Macchi F, Keck RG, Shyong B-J, Ling VT, Cordoba AJ, Marian M, Sinclair D, Battersby JE, et al.. Analytical characterization of monoclonal antibodies: linking structure to function In: Shire SJ, Gombotz W, Bechtold-Peters K, Andya J, eds. Current trends in monoclonal antibody development and manufacturing. New York: (NY: ): Springer New York; 2010, pp. 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Remmele RL, Callahan WJ, Krishnan S, Zhou L, Bondarenko PV, Nichols AC, Kleemann GR, Pipes GD, Park S, Fodor S, et al.. Active dimer of Epratuzumab provides insight into the complex nature of an antibody aggregate. J Pharm Sci. 2006;95:126–45. doi: 10.1002/jps.20515. PMID:16315222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brych SR, Gokarn YR, Hultgen H, Stevenson RJ, Rajan R, Matsumura M. Characterization of antibody aggregation: role of buried, unpaired cysteines in particle formation. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99:764–81. doi: 10.1002/jps.21868. PMID:19691118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Buren N Rehder D, Gadgil H, Matsumura M, Jacob J. Elucidation of two major aggregation pathways in an IgG2 antibody. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:3013–30. doi: 10.1002/jps.21514. PMID:18680168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bloom JW, Madanat MS, Marriott D, Wong T, Chan S-Y. Intrachain disulfide bond in the core hinge region of human IgG4. Protein Sci. 1997;6:407–15. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060217. PMID:9041643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorman JJ, Wallis TP, Pitt JJ. Protein disulfide bond determination by mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2002;21:183–216. doi: 10.1002/mas.10025. PMID:12476442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haniu M, Acklin C, Kenney WC, Rohde MF. Direct assignment of disulfide bonds by Edman degradation of selected peptide fragments. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1994;43:81–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1994.tb00378.x. PMID:8138354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu S, Fan S-B, Yang B, Li Y-X, Meng J-M, Wu L, Li P, Zhang K, Zhang M-J, Fu Y, et al.. Mapping native disulfide bonds at a proteome scale. Nat Methods. 2015;12:329. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3283. PMID:25664544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Z, Pan H, Chen X. Mass spectrometry for structural characterization of therapeutic antibodies. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2009;28:147–76. doi: 10.1002/mas.20190. PMID:18720354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srebalus Barnes CA, Lim A. Applications of mass spectrometry for the structural characterization of recombinant protein pharmaceuticals. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2007;26:370–88. doi: 10.1002/mas.20129. PMID:17410555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mikesh LM, Ueberheide B, Chi A, Coon JJ, Syka JEP, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. The utility of ETD mass spectrometry in proteomic analysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1764:1811–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.10.003. PMID:17118725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark DF, Go EP, Desaire H. Simple approach to assign disulfide connectivity using extracted ion chromatograms of electron transfer dissociation spectra. Anal Chem. 2013;85:1192–9. doi: 10.1021/ac303124w. PMID:23210856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zubarev RA, Kruger NA, Fridriksson EK, Lewis MA, Horn DM, Carpenter BK, McLafferty FW. Electron capture dissociation of gaseous multiply-charged proteins is favored at disulfide bonds and other sites of high hydrogen atom affinity. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:2857–62. doi: 10.1021/ja981948k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sobczyk M, Anusiewicz I, Berdys-Kochanska J, Sawicka A, Skurski P, Simons J. Coulomb-assisted dissociative electron attachment: application to a model peptide. J Phys Chem A. 2005;109:250–8. doi: 10.1021/jp0463114. PMID:16839114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Syrstad EA, Turecček F. Toward a general mechanism of electron capture dissociation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2005;16:208–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.11.001. PMID:15694771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neff D, Smuczynska S, Simons J. Electron shuttling in electron transfer dissociation. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2009;283:122–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2009.02.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu S-L, Jiang H, Lu Q, Dai S, Hancock WS, Karger BL. Mass spectrometric determination of disulfide linkages in recombinant therapeutic proteins using online LC−MS with electron-transfer dissociation. Anal Chem. 2009;81:112–22. doi: 10.1021/ac801560k. PMID:19117448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cole SR, Ma X, Zhang X, Xia Y. Electron Transfer Dissociation (ETD) of peptides containing intrachain disulfide bonds. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:310–20. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0300-z. PMID:22161508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Lu Q, Wu S-L, Karger BL, Hancock WS. Characterization and comparison of disulfide linkages and scrambling patterns in therapeutic monoclonal antibodies: using LC-MS with electron transfer dissociation. Anal Chem. 2011;83:3133–40. doi: 10.1021/ac200128d. PMID:21428412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu YD, Chou RYT, Dillon TM, Poppe L, Spahr C, Shi SDH, Flynn GC. Protected hinge in the immunoglobulin G2-A2 disulfide isoform. Protein Sci. 2014;23:1753–64. doi: 10.1002/pro.2557. PMID:25264323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shukla AA, Hubbard B, Tressel T, Guhan S, Low D. Downstream processing of monoclonal antibodies—application of platform approaches. J Chromatogr B. 2007;848:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chrisman PA, Pitteri SJ, Hogan JM, McLuckey SA. SO 2 −· electron transfer ion/ion reactions with disulfide linked polypeptide ions. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:1020–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.02.010. PMID:15914021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valdivieso-Torres L, Sarangi A, Whidby J, Marcotrigiano J, Roth MJ. Role of cysteines in stabilizing the randomized receptor binding domains within feline leukemia virus envelope proteins. J Virol. 2016;90:2971–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02544-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z. Prediction of low-energy collision-induced dissociation spectra of peptides. Anal Chem. 2004;76:3908–22. doi: 10.1021/ac049951b. PMID:15253624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Good DM, Wenger CD, Coon JJ. The effect of interfering ions on search algorithm performance for ETD data. Proteomics. 2010;10:164–7. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900570. PMID:19899080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Good DM, Wenger CD, McAlister GC, Coon JJ. Post-acquisition ETD spectral processing for increased peptide identifications. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:1435–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.03.006. PMID:19362853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.