SUMMARY

Human diseases are often caused by loss of somatic cells incapable of re-entering the cell cycle for regenerative repair. Here, we report a combination of cell-cycle regulators that induce stable cytokinesis in adult post-mitotic cells. We screened cell-cycle regulators expressed in proliferating fetal cardiomyocytes and found overexpression of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1), CDK4, cyclin B1, and cyclin D1 efficiently induced cell division in post-mitotic mouse, rat and human cardiomyocytes. Overexpression of the cell-cycle regulators was self-limiting through proteasome-mediated degradation of the protein products. In vivo, lineage tracing revealed that 15–20% of adult cardiomyocytes expressing the four factors underwent stable cell division, with significant improvement in cardiac function after acute or subacute myocardial infarction. Chemical inhibition of Tgf-β and Wee1 made CDK1 and cyclin B dispensable. These findings reveal a discrete combination of genes that can efficiently unlock the proliferative potential in cells that had terminally exited the cell cycle.

Keywords: Heart, Cardiomyocyte, Cell Division, Cyclin, CDK, Cell Cycle, Regeneration

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian cell cycle is highly regulated and involves numerous feedback loops that either permit or prevent cell division, depending on the cell type (Hydbring et al., 2016; Malumbres and Barbacid, 2009). Although fetal cells proliferate to achieve organ growth and tissue-specific stem cells undergo cytokinesis post-natally, differentiated cells generally become post-mitotic and permanently exit the cell cycle (Li and Kirschner, 2014). As a result, the regenerative capacity of most organs through cell proliferation is limited. In contrast, organisms such as zebrafish and reptiles are highly regenerative due to efficient re-entry of adult cells into the cell cycle after damage (Aguirre et al., 2013; Yin and Poss, 2008). The ability to control cell-cycle entry in post-natal tissue would represent a powerful approach for mammalian regeneration, but has been met with limited success to date.

The cell-cycle exit of mammalian cardiomyocytes appears to be among the most stable, perhaps signified by the rarity of cardiac tumors (Lestuzzi, 2016). The ability of fetal cardiomyocytes to divide extends into the first week of life in mice, and as a result, mice retain the ability to regenerate after cardiac damage until approximately post-natal day 7 (P7), but not beyond (Porrello et al., 2011; Puente et al., 2014). In contrast, zebrafish retain the capacity for cardiac regeneration into adulthood, primarily through cardiomyocyte proliferation (Gemberling et al., 2015; Jopling et al., 2010; Kikuchi et al., 2010). Although manipulation of signaling through the Hippo pathway, which regulates organ size during development, allows re-entry of cardiomyocytes into the cell cycle and facilitates some cardiac regeneration in mice (Heallen et al., 2011; Leach et al., 2017; Morikawa et al., 2015; Xin et al., 2013), the minimal cell-cycle genes required for efficient cytokinesis remain unknown. Numerous attempts to identify such cell-cycle regulators that could induce cell division of cardiomyocytes or other cell types have resulted in nuclear division (karyokinesis), but inefficient cleavage into two distinct daughter cells (cytokinesis) and subsequent survival, as reviewed in (Zebrowski et al., 2016). Such strategies stimulate activation of cell-cycle markers in no more than 1% of cardiomyocytes, limiting their utility.

Cytokinesis involves not only progression through the G1/S phase with DNA synthesis, but also efficient progression through the G2/M phase. Each transition is regulated by distinct complexes of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (Fededa and Gerlich, 2012). The expression of a number of these regulators is diminished in mammalian hearts coincident with their exit from the cell cycle (Rubart and Field, 2006; Takeuchi, 2014; Zebrowski et al., 2016).

Here, we took a combinatorial approach to screen for factors and conditions that could recapitulate the fetal state of cardiomyocyte division. Ectopic introduction of the Cdk1/CyclinB1 and the Cdk4/CyclinD1 complexes promoted cell division in at least 15% of mouse and human cardiomyocytes in vitro. Rigorous assessment of cell division in vivo with the Cre-recombinase dependent Mosaic Analysis with Double Markers (MADM) lineage tracing system revealed similar efficiency in mouse hearts, with cardiac regeneration upon delivery of cell-cycle regulators immediately after myocardial infarction and even 1 week after injury.

RESULTS

Screening for Cell-Cycle Genes That Promote Cardiomyocyte Proliferation

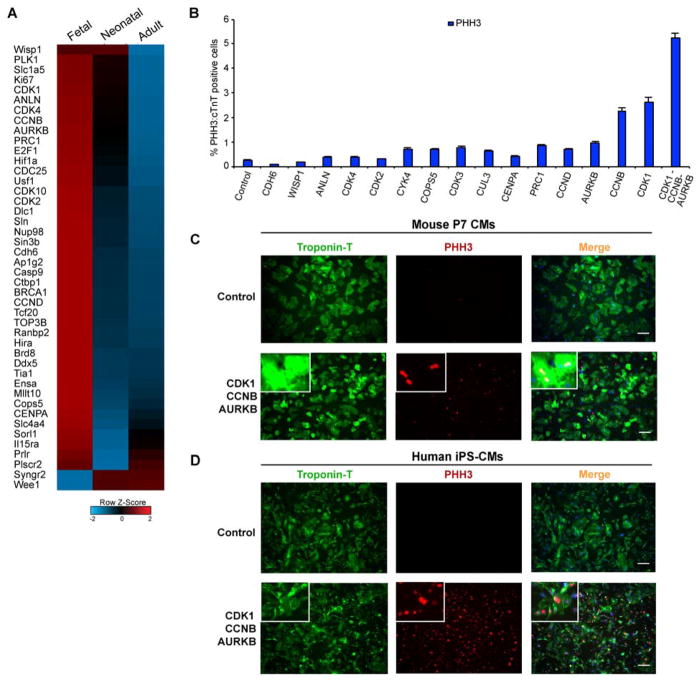

To identify factors that influence cardiomyocyte proliferation, we performed transcriptome analyses on embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5, fetal), 1-day-old (P1, neonatal), and 8-week-old (adult) C57/Bl6 mouse hearts and compared the expression levels of the major cell-cycle regulators. Most cell-cycle genes in adult hearts were significantly downregulated, compared to neonatal and fetal hearts (Figure 1A). We cloned 15 of the top differentially regulated genes between proliferative (fetal/neonatal) and non-proliferative (adult) cardiac cells—focusing on the genes more involved in cytokinesis—into adenoviral vectors. We infected primary mouse cardiomyocytes (85–90% purity) (Mohamed et al., 2016) harvested at post-natal day 7 (P7), when cell division had ceased, with either a control virus or the cell-cycle regulators of interest. After 48 hours, we fixed the cells and assessed the potential for cardiomyocyte proliferation by histone H3 phosphorylation (PHH3), marking cells that may enter mitosis. We found that cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1), cyclin B1 (CCNB), and aurora kinase B (AURKB) were the top hits that individually enhanced the number of PHH3+ cardiomyocytes (Figure 1B), assessed by co-localization of PHH3 staining with cardiac Troponin-T (cTnT) staining using the BZ-analyzer software. Combining the three genes resulted in further enhancement in histone H3 phosphorylation in 7-day-old primary mouse cardiomyocytes marked by cTnT (~200-fold more than controls) (Figure 1B and C). To test this combination in human cardiomyocytes, we overexpressed the three genes in post-mitotic 60-day-old human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes (hiPS-CMs), selected for 90–95% purity (Ang et al., 2016), and observed a similar increase in PHH3+:cTnT+ cardiomyocytes (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Screening of Fetal Cell-Cycle Genes that Can Promote Cardiomyocyte Phospho-histone 3 (PHH3) expression.

(A) Row normalized Z-score heatmap (average of n=3) shows selected transcriptome data for differentially expressed genes related to cell-cycle regulation between fetal (E10.5), neonatal (P1) and adult (8-week-old) mouse hearts.

(B) Bar graph shows the percentage of cardiomyocyte (cTnT+) nuclei positive for phospho-histone H3 (PHH3) 48 hours after adenoviral infection to overexpress the indicated protein in post-natal day 7 (P7) primary mouse cardiomyocytes.

(C, D) Immunocytochemistry of P7 primary mouse cardiomyocytes (C) or 60-day-old human iPS–derived cardiomyocytes (D) infected with a control adenovirus or CDK1-CCNB-AURORA expressing adenoviruses and immunostained 48 hours later with antibodies to PHH3 (red), cardiac Troponin T (green) and DAPI (blue) to mark nuclei; insets represent higher magnification of cells. Also, see Figure S1.

Using time-lapse imaging, we assessed the phases of cell division in primary mouse cardiomyocytes isolated from cardiomyocyte-specific α-myosin heavy chain (αMHC)-GFP transgenic mice at P7 (Ieda et al., 2010) and in 60-day-old hiPS-CMs overexpressing CDK1, CCNB, and AURKB (Figure S1A, B and Supplementary Movie 1, 2). Although most of the cells that underwent complete cell division did so within the first 48–72 hours, cell death occurred very soon after dividing.

CDK1/CCNB/CDK4/CCND Combinatorially Induces Stable Cardiomyocyte Proliferation

To investigate why cell division induced by CDK1, CCNB and AURKB triggered cell death, we considered that the premature or inappropriate entry of cells into the mitosis phase may be the cause, as all three factors mainly promote G2/M phase progression (Vitale et al., 2011). In agreement with this, expression of DNA damage response markers, including p-ATM, p-Chk1, and p-Chk2, was significantly elevated after overexpression of the three factors (Figure S1C).

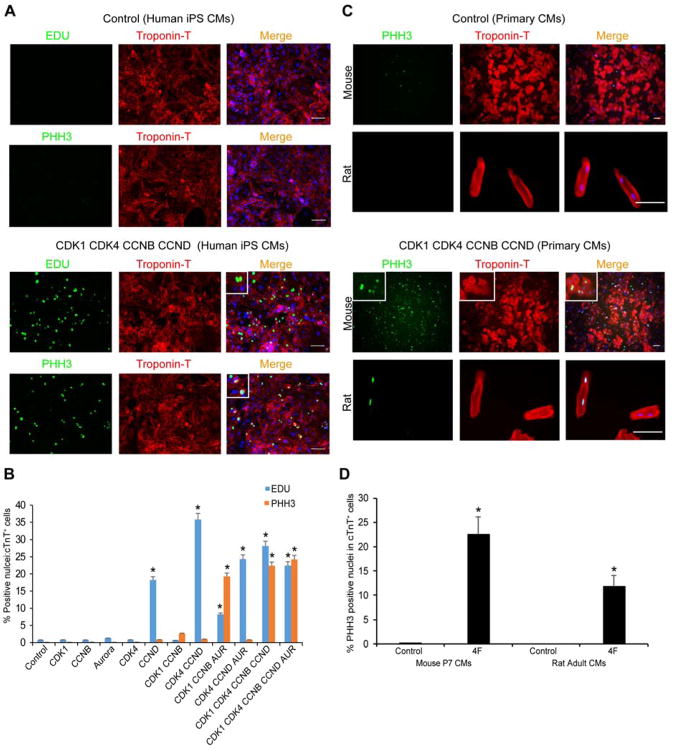

To find genes that also promote the G1 phase, we tested additional genes involved in this phase, including cMyc, CDK4, and CCND. By systematically testing combinations of the cell-cycle regulators, we found that a cocktail containing the CDK1/CCNB and CDK4/CCND complexes most efficiently enhanced hiPS-CM proliferation. This combination resulted in ~20% of cTnT-expressing cells being positive for both EDU and PHH3 staining (Figure 2A, B). In addition, this was evident in P7 primary mouse cardiomyocytes (Figure 2C, D) and even 4-month-old isolated adult rat cardiomyocytes (Figure 2C, D).

Figure 2. CDK1-CDK4-CCNB-CCND Induces EDU- and PHH3-Positive Human, Mouse and Rat Cardiomyocytes In Vitro.

(A) Representative immunocytochemistry images of PHH3, EDU, cardiac TroponinT (cTnT) and Dapi in 60-day-old human iPS-derived cardiomyocytes (iPS-CMs) 48 hours after control or CDK1-CDK4-CCNB-CCND (4F) viral infection, shown with higher magnification insets.

(B) Quantification of EDU+:cTnT+ or PHH3+:cTnT+ nuclei among CMs in response to overexpression of the indicated proteins in 60-day-old human iPS-CMs (n=3 independent experiments, *p<0.05).

(C) Representative immunocytochemistry of P7 primary mouse cardiomyocytes (top rows) and 4-month-old adult rat cardiomyocytes (lower rows) infected with LacZ (Control, top panel) or 4F (CDK1-CDK4-CCNB-CCND, lower panel) expressing adenoviruses and stained 48 hours later with PHH3 (green), cTnT (red) and DAPI nuclear stain (blue); insets represent higher magnification.

(D) Quantification of mouse or rat cTnT+ cardiomyocytes that were PHH3+ as a percentage of total cTnT+ cells (n=260 cells cTnT+ counted for each type). Bars represent average of three experiments and error bars indicate SEM (*p<0.05). Also, see Figure S1.

Surprisingly, the percentages of cardiomyocytes positive for EDU and PHH3 were similar. All initial assessments for PHH3 and EDU were done within 48 hours after virus infection, and thus, accumulation of EDU-positive nuclei through multiple cell cycles would not be expected. However, it is curious that such a high percentage of cTnT-expressing cells was PHH3 positive, raising the possibility that a portion of those may be the result of a G2/M arrest, aberrant phosphorylation of histone H3, or a direct effect of the cell-cycle genes on chromatin condensation in cardiomyocytes. Nevertheless, video microscopy, which can more directly assess successful cell division, revealed that with the combination of CDK1, CDK4, CCNB, and CCND, primary P7 mouse cardiomyocytes divided once over 6 days and remained viable after cell division (Supplementary Movie 3). In agreement with the viability, we found the CDK1/CCNB/CDK4/CCND combination suppressed upregulation of the DNA damage response observed by the 3F (Figure S1C). This combination, hereafter referred to as 4F, was used for more rigorous and definitive in vivo assessment of cardiomyocyte cytokinesis.

Lineage Tracing of Cardiomyocyte Proliferation In Vivo

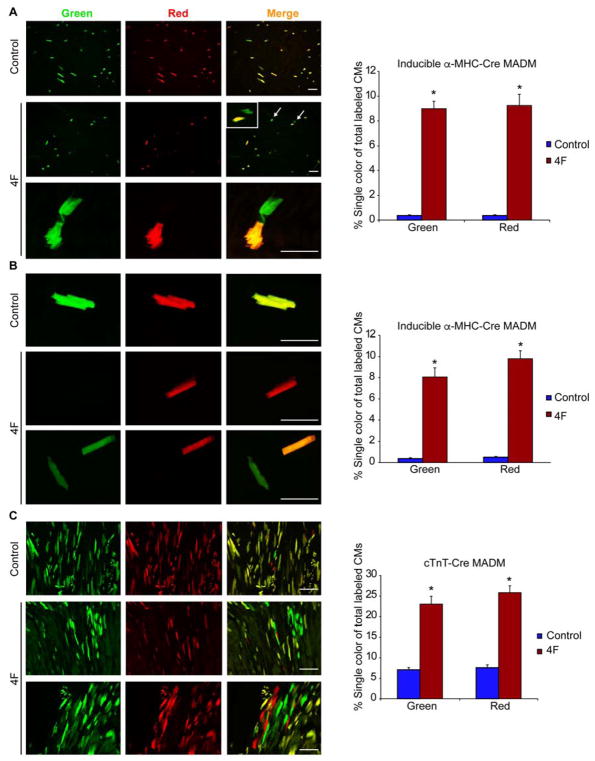

Because of the potential confounding issues around the use of EDU and PHH3 as markers to assess cytokinesis, we more carefully determined if the combination of CDK1/CCNB/CDK4/CCND induced true cardiomyocyte division in vivo by tracking cardiomyocyte proliferation in transgenic mice often used for lineage-tracing with a system known as Mosaic Analysis with Double Markers (MADM) (Ali et al., 2014; Zong et al., 2005). With this approach, cardiomyocytes that successfully divide in the presence of a cell-type-specific Cre-recombinase will produce daughter cells that are either red, green, red and green (yellow), or colorless, based on allelic recombination of fluorescent reporters; however, if the cardiomyocytes fail to divide, they will remain double-colored as yellow if recombination occurs or colorless if no recombination occurs (Figure S2A). Thus, the presence of single-color red or green cells definitively indicates cells that have undergone cell division, although dividing cells would be underrepresented by single-color cells, as double-colored (yellow) or colorless cells could have also divided.

We first used this lineage-tracing method to evaluate cardiomyocyte proliferation 2 weeks after myocardial infarction (MI) in 4-month-old adult mice using the inducible α-MHC-MER-CRE-MER MADM mouse. In these mice, Cre-recombinase can be inducibly activated specifically with tamoxifen in adult cardiomyocytes, thereby inducing recombination of the MADM reporter system. The cell-cycle markers (PHH3 and EDU) were observed in dividing single-colored cardiomyocytes during the first 4 days after 4F virus infection in vivo, validating the model as described (Figure S2B, C), and the fluorescent reporter was validated by immunohistochemistry using anti-GFP and anti-dsRed antibodies (Figure S3A). Intramyocardial injection of adenoviruses encoding the 4F increased the number of single-colored cells (green or red) to over 16% of the total recombinant cell number, compared to <1% in the control virus-injected group, indicating successful cell division in vivo in the infarct and peri-infarct areas (Figure 3A and Figure S3B). The control group results were similar to reported basal heart proliferation levels using the same mouse model (Ali et al., 2014), and there was no significant difference in the number of yellow cells in the 4F and control groups (Figure S4A), demonstrating an increase in absolute numbers of single-colored cells in addition to an increase in the percentage among recombined cells. We also isolated single-colored cardiomyocytes from digested hearts 14 days after expression of the 4F. The single-colored cells exhibited a rod-shaped structure and organized sarcomeres, and occurred in similar numbers to what we recorded histologically (Figure 3B). As expected, most of the proliferation events induced by the 4F, indicated by single-colored cells, were at the infarct or border zones with little effect on cells in the remote zone away from the area of viral injection (Figure S4B).

Figure 3. Mosaic Analysis of Double Markers (MADM) Genetically Label Cardiomyocytes after Cell Division and Reveal Cytokinesis In Vivo with 4F.

(A, B) Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of single colored (red or green) cells, indicating cardiomyocytes that underwent cytokinesis, in α-MHC MER-CRE-MER MADM mice in histological sections (A) or isolated cardiomyocytes (B) after Cre-induction in 4-month-old adult mice. Lower panel in (A) represents higher magnification. Colorless or double-labeled cells were indeterminate for cytokinesis. Mice were injected intramyocardially with adenoviruses encoding CDK1, CCNB, CDK4, and CCND (4F) or control Lac-Z virus at the time of MI induction (n=6–8 animals in each group, (8000 cells analyzed/group) *p<0.05).

(C) Representative images and quantification of single-colored cardiomyocytes in constitutive (cTnT)-CRE MADM mice with control or 4F viral infection after MI (n=3 animals in each group, (8000 cells analyzed/group) *p<0.05). 4F rows in (B) and (C) indicate distinct cells or histologic areas. Bars indicate average of experiments with SEM; student t-Test was used to compare between the two groups. Also, see Figure S2–S6.

To validate this observation with a second Cre-recombinase that was constitutive, we used the cardiac Troponin-T (cTnT)-CRE MADM system, which is active during the proliferative period in utero and in adulthood. This CRE has a recombination efficiency of 2–5%, labeling more cardiomyocytes than the 0.001–0.01% of cells labeled in the α-MHC-Cre:MER-CRE-MER MADM mice (Ali et al., 2014; Zong et al., 2005). In 4-month-old cTnT-CRE MADM control mice, 10% of cardiomyocytes in the recombinant pool were single-labeled (red or green) due to cell proliferation before birth. In contrast, in cTnT-CRE MADM mice that received 4F at 4 months of age, 50% of cardiomyocytes in the recombinant pool were single-labeled as red or green (Figure 3C). Furthermore, we assessed the nucleation of single-colored cardiomyocytes and found that in animals treated with 4F, over 90% of these cells were mono-nucleated (Figure S4C), although the approach may bias detection toward cells that become mono-nucleated.

Using RNA-seq, we compared the transcriptomes of endogenous adult cardiomyocytes, neonatal cardiomyocytes, and cardiac fibroblasts to α-MHC-Cre:MER-CRE-MER MADM single-colored (proliferated) or yellow (mostly non-proliferated) cardiomyocytes isolated by digestion of hearts 2 weeks after MI and 4F injection. The gene expression signatures of yellow cells or single-colored cells were more similar to adult ventricular cardiomyocytes than neonatal cardiomyocytes or cardiac fibroblasts, with yellow cells being closer to adult cardiomyocytes than the single-colored cells. The biological replicates of single-colored cells showed more variability than replicates of yellow cells, suggesting the cells are in variable states of maturation after cell division (Figure S5A). Furthermore, analysis of Gene Ontology (GO) terms among differentially expressed genes (>twofold, p<0.05) between the single-colored and yellow cardiomyocytes showed that factors involved in fatty acid metabolism predominated among down-regulated genes, perhaps suggesting a slightly less mature state 2 weeks after division. Conversely, the vast majority of upregulated genes were largely related to the immune response as expected after viral infection (Figure S5B&C). Overall, the single-colored cells were very similar to the yellow cardiomyocytes, other than the cellular response to viral infection.

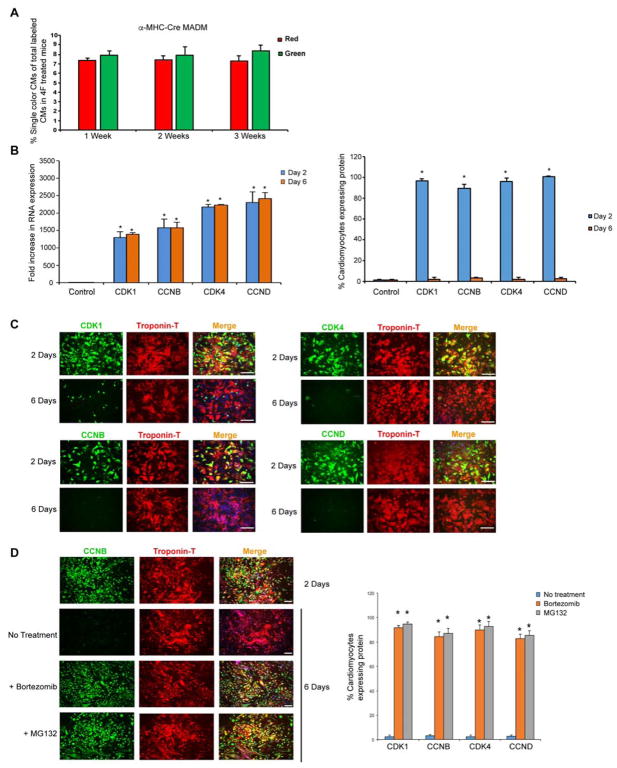

Interestingly, the number of single-color cells was not significantly increased in vivo after the initial increase during the first week after 4F virus infection (Figure 4A). We found that although mRNA levels of the virally delivered genes remained stable (Figure 4B), the levels of their protein products declined over time, becoming undetectable by day 6 in infected cardiomyocytes (Figure 4C). In the presence of a proteasome inhibitor, the protein levels persisted beyond 6 days (Figure 4D), indicating that proteasome-dependent protein degradation limits activity of the cell-cycle regulators, likely through well-described ubiquitin-related feedback loops (Fujimitsu et al., 2016; Nakayama and Nakayama, 2006).

Figure 4. Cardiomyocytes Degrade Overexpressed Cell-Cycle Proteins over Time in a Proteasome-Dependent Manner.

(A) Quantification of single-colored cells in α-MHC-Cre MADM mice 1, 2 and 3 weeks after coronary ligation and 4F infection. After the initial increase in number of single-colored cells during the first week, there was no further increase (n=600 cells analyzed from four animals in each group).

(B) Bar graphs show RNA expression (left panel) and protein expression (right panel) of the overexpressed cell cycle genes at 2 and 6 days after infection (n=3, *p<0.05).

(C) Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification for indicated protein (green) and cardiac Troponin-T (red) over time demonstrates a decline in the overexpressed protein expression by day 6 after adenoviral infection of each (n=3 independent experiments, *p<0.05).

(D) Representative images (for CCNB) and quantification of cTnT+ cardiomyocytes treated with proteosome inhibitors (Bortezomib or MG132) for 48 hours starting at day 4 demonstrate persistent protein expression of the overexpressed cell cycle genes at day 6 (n=3, *p<0.05) in the presence of proteosome inhibitors. Bars indicate means and SEM. Also, see Figure S7.

To test whether the MI and its associated inflammation affected cardiomyocyte proliferation, we injected 4F into α-MHC MER-CRE-MER MADM mice without inducing MI. Here, we detected ~10% single-colored cardiomyocytes among the recombinant cells in the non-infarct group (Figure S6A–C), compared to 16% in the MI group. These results indicated that the inflammatory reaction during MI may promote, but is not necessary for, 4F-induced cardiomyocyte proliferation in vivo.

To determine if cardiac fibroblasts, which already can proliferate, also respond to 4F, we isolated Thy1+ cells, largely cardiac fibroblasts, from β-actin-Cre:MER-CRE-MER MADM mice. We found that in vivo exposure to 4F after injury did not result in an increase in the absolute number of single-colored Thy1+ cells nor the percent of single-colored cells among recombined Thy1+ cells (~75%) (Figure S7A). Because only 10–20% of fibroblasts were infected with the adenovirus dose delivered in vivo, we used 100 MOI (10 times more than the MOI used for cardiomyocytes) on Thy1+ cardiac fibroblasts cultured in vitro for the adenovirus to reach >80% infection efficiency (Figure S7B). Despite this, there was no significant effect of 4F overexpression in cardiac fibroblasts as assessed by EDU incorporation (Figure S7C, D). The lack of significant response to 4F in fibroblasts may reflect the fact that the introduced cell-cycle factors are already expressed at baseline and the basal background of proliferation is already high with over 70% of fibroblasts being EDU+ in vitro. Among the cells that had recombination, a high percentage were single-colored at baseline, as virus was introduced right after MI when fibroblast proliferation was high.

Cell-Cycle Regulators Enhanced Cardiac Function and Increased Cardiomyocyte Proliferation after Myocardial Infarction In Vivo

Next, we tested the effects of 4F on cardiac function in vivo after cardiac damage. We performed intramyocardial injection of 4F or control adenoviruses into the peri-infarct site of mice at the time of coronary artery ligation. C57Bl6 mice were used for efficacy studies, rather than the triple transgenic αMHC-Cre:MADM mice, in order to test functional consequences in a large number of mice. All surgeries, imaging and necropsy analyses were blinded with regard to the treatment, and animals were decoded only after all data were collected. 4F injection improved heart function as indicated by significant improvement in the ejection fraction (EF), stroke volume and cardiac output (Figure 5A) assessed after 12 weeks by blinded magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the most accurate measure of heart structure and function. In agreement with this, histologic analyses revealed thick muscle within the infarct region of hearts treated with 4F, even at the apex of the heart (Figure 5B). With both MRI, measuring percent scar in the left ventricle, and histological analyses, assessing fibrotic regions within the area of damage by Trichrome stain, we found that scar size was ~50% less in the 4F-treated group than the control group (Figure 5A, C).

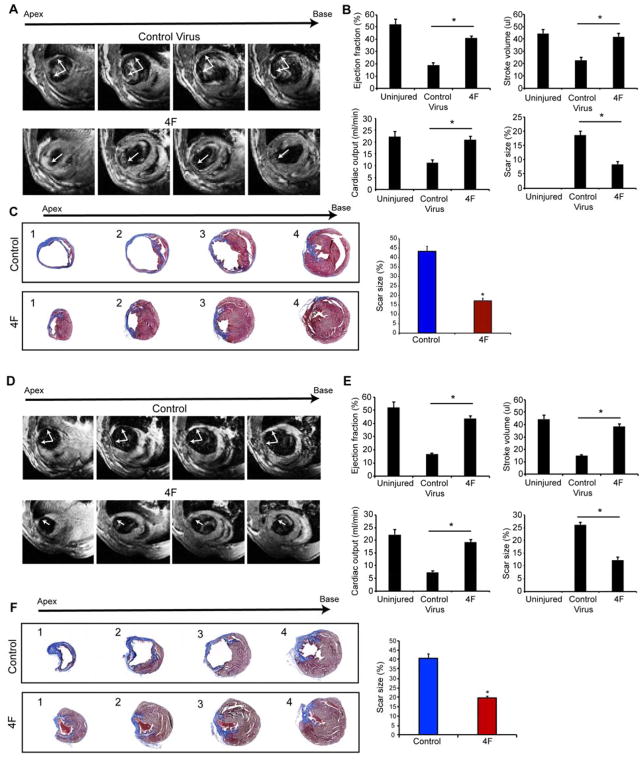

Figure 5. CDK1:CCNB:CDK4:CCND (4F) Expression Enhances Cardiac Function in Mice after Acute or Sub-Acute Myocardial Infarction.

(A) Representative transverse magnetic resonance images (MRI) 12 weeks after myocardial infarction and adenovirus injection at the time of the infarction shows ventricular wall thinning at the infarct site in the control group with improvement in animals that received the 4F (arrows). Multiple images from the bottom (apex) to the top of the ventricular chambers (base) are shown.

(B) Ejection fraction, stroke volume, cardiac output and scar size (through all heart slices), as measured by blinded MRI, were significantly improved in 4F-treated mice, compared to control mice (n=9, *p<0.05).

(C) Representative histological sections through multiple levels of the heart (apex (1) towards base (4)) with Masson’s Trichrome staining showing the scar tissue in blue and the healthy myocardium in red, with and without 4F treatment. Bar graph shows the quantification of scar size by histology (through levels 1–4 as described in the methods) (n=9, *p<0.05). Bars indicate means and error bars indicate SEM. Student t-Test was used to compare between the two groups.

(D) Representative MRI images 12 weeks after myocardial infarction and virus injection 1 week after infarction shows the wall thinning at the infarct site in the control group, which was improved in the animals that received the 4F.

(E) Ejection fraction, stroke volume, cardiac output and scar size as measured by MRI, were significantly improved in 4F-treated mice compared to control mice (n=9, *p<0.05). Bars indicate means with SEM.

(F) Representative histological sections through multiple levels of the heart with Masson’s Trichrome staining, with and without 4F treatment delivered one week after injury. Bar graph shows the quantification of scar size by histology (n=9, *p<0.05). Also, see Figure S7.

While the improvement in cardiac function upon immediate treatment before scar formation was encouraging, a more clinically relevant situation involves presence of a fibrotic scar that has replaced necrotic myocardium and results in progressive dysfunction. We therefore repeated the functional studies after injecting adenovirus encoding the 4F 1 week after myocardial infarction, when a clear scar is present but has not fully thinned as yet, making technical aspects of adenovirus injection feasible in the mouse. Although control and treated mice had similarly diminished EF 1 week after MI (40.7 ± 1.2% vs. 41.2 ± 1.3%, respectively; p=0.79), the 4F treatment group displayed significantly higher EF, stroke volume and cardiac output after 3 months by MRI than control treated mice (Figure 5D, E). Furthermore, histological analysis and MRI showed a significant 50% reduction in scar size and improvement in muscle thickness (Figure 5E, F). The decrease in scar formation, even when treatment was initiated one week after MI, may reflect the immaturity of scar at this early stage, making it more amenable to replacement by proliferating cardiomyocytes at the border zone.

Simplification of Cardiomyocyte Cell-Cycle Induction

In an attempt to simplify the genes needed for cardiomyocyte cell division, we examined the effect of growth factors that may enhance cardiomyocyte proliferation, including heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (hbEGF) (Ieda et al., 2009), neuregulin (NRG1) (Bersell et al., 2009; Polizzotti et al., 2015), and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) (Huang et al., 2013; Li et al., 2011), as well as known regulators of CDK1 activity, including cell-division cycle 25 (CDC25) and Wee1 (Boutros et al., 2007). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis® (Qiagen), comparing RNAseq data from neonatal and adult hearts, revealed that the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) and IGF pathways were the top differentially regulated pathways. We therefore included TGFβ and its inhibitor SB431542 in the screen for stable cell division. Addition of CDC25 was not more effective than 4F, nor was inclusion of the secreted factors. However, chemical inhibition of Wee1, a negative regulator of CDK1, using MK1775, along with the TGFβ inhibitor SB431542 (abbreviated as 2i), replaced the need for CDK1 and CCNB from the 4F cocktail, based on cells positive for PHH3 (Figure 6A). Given the potential unreliability of PHH3 as a marker of proliferation in this assay, we assessed the CDK4, CCND and 2i (2F2i) cocktail in vivo using the αMHC-Cre-based MADM system used with the 4F approach. Efficiency of the 2F2i combination was similar to 4F in inducing single-colored daughter cells marking cells that have undergone cell division (Figure 6B).

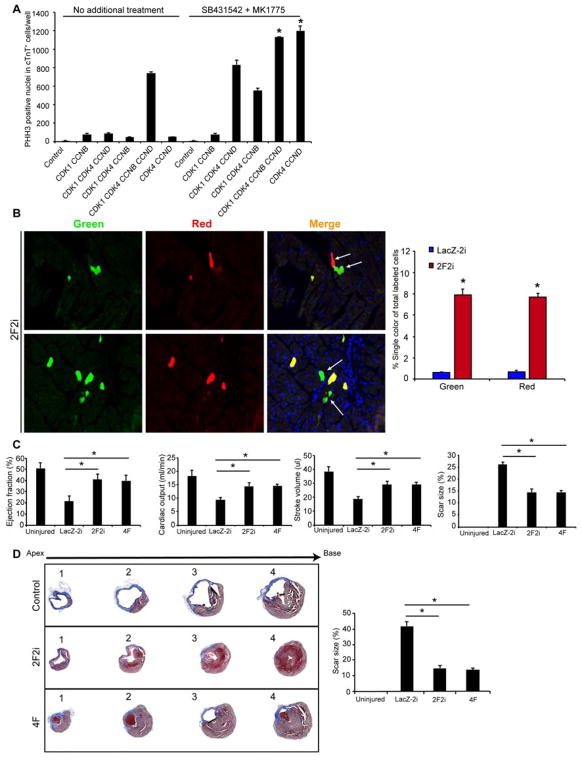

Figure 6. CDK4 and CCND, with Transient Wee1 and TGFβ Inhibition (2F2i), Induces Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Enhances Cardiac Function after Injury.

(A) Histograms quantifying the number of PHH3+ nuclei in cTnT+ human iPS-CMs upon expression of indicated combinations of factors in the presence or absence of a Wee1 inhibitor (MK1775) and a TGFβ inhibitor (SB431542) (*p<0.05).

(B) Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of single colored (red or green) cells in histologic sections of α-MHC MER-CRE-MER MADM mice, indicating cardiomyocytes that underwent cytokinesis (n=4 animals in each group *p<0.05).

(C) Ejection fraction, stroke volume, cardiac output and scar size (through all ventricular heart slices), as measured by blinded MRI after 3 months, were similarly improved in 2F2i and 4F-treated mice compared to control mice (n=8, *p<0.05).

(D) Representative histological sections through multiple levels of the heart (apex [1] towards base [4]) with Masson’s Trichrome staining showing the scar tissue in blue and the healthy myocardium in red, with LacZ-2i, 2F2i, or 4F treatment. Bar graph shows quantification of scar size by histology (through levels 1–4 as described in the methods) (n=8, *p<0.05). Bars represent means and error bars indicate SEM. One-way ANOVA was used to compare between the three groups.

To assess the effect of 2F2i on cardiac function, we performed functional studies similar to those described above after injecting adenovirus encoding CDK4 and CCND intra-myocardially 1 week after myocardial infarction, and injecting the two small molecules daily intraperitoneally for 1 week (1 mg/kg/day). Baseline cardiac dysfunction, assessed by ejection fraction, 1 week after infarction and before treatment was similar in all groups (LacZ-2i: 32.6 ± 2.44%; 2F2i: 31.66 ± 2.3; 4F: 33.2 ± 2.46%). The 4F and 2F2i treatment groups showed similarly greater measures of cardiac function after 3 months, compared to control treated mice, as assessed by MRI (Figure 6C). Furthermore, histological analysis and MRI consistently showed a significant reduction in scar size and improvement in muscle thickness (Figure 6C, D).

Mechanistically, we found that 2i resulted in dampening of the 2F-induced increase in p27 protein expression in human iPS-CMs (Figure 7A). Furthermore, knocking down p27 with siRNA in iPS-CMs overexpressing 2F induced PHH3 expression to similar levels as 2F2i (Figure 7B & C), suggesting p27, which represses activity of G1 phase cyclins (Ravitz et al., 1996), as a significant block to proliferation in this setting (Figure 7D).

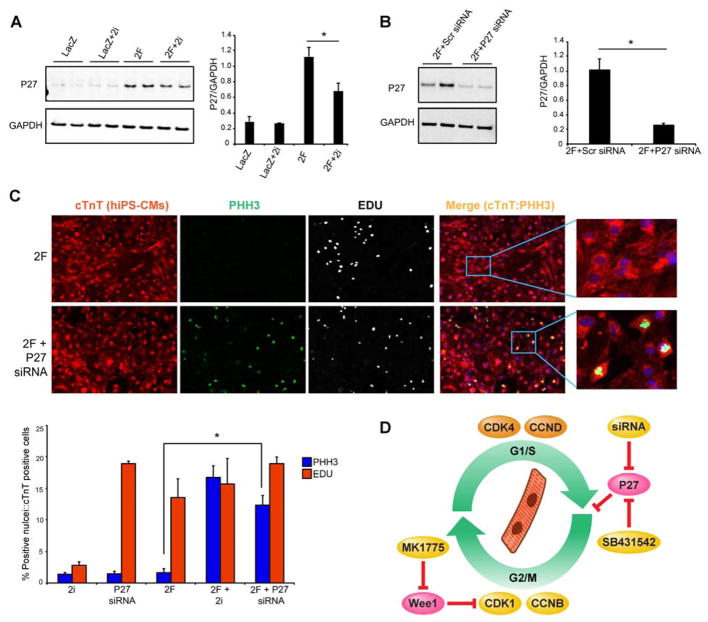

Figure 7. Wee1 and TGFβ Inhibition (2i) Limit P27 Activation Induced by CDK4 and CCND.

(A) Representative western blots and quantification for P27 expression in human iPS-CMs overexpressing either LacZ control virus, or 2F (CDK4/CCND) in the presence or absence of the 2i after 48 hours (n=3 independent experiments, *p<0.05). Bars indicate average ratio of image density for each protein band relative to GAPDH intensity, with SEM.

(B) Representative western blots and quantification of P27 knockdown using P27 siRNA vs scrambled (Scr) control siRNA (n=3 independent experiments, *p<0.05).

(C) Representative images and quantification for EDU incorporation and histone H3 phosphorylation (PHH3) to examine the effect of knocking down P27 using siRNA compared to 2i in the setting of 2F introduced into human iPS-CMs (n=3 independent experiments, *p<0.05).

(D) Summary of findings showing that a combination of four cell cycle regulators can induce cytokinesis of mature cardiomyocytes in vitro and in vivo resulting in repair of damaged hearts. Similar results were obtained with only two cell cycle regulators (CDK4/CCND) and either inhibition of Wee1 using MK1775 and Tgf-β using SB431542, or P27 knockdown with siRNA.

DISCUSSION

The findings here demonstrate that a combination of four cell-cycle regulators, composing the CDK1:CCNB and CDK4:CCND complexes, can efficiently induce cardiomyocyte proliferation and subsequent cell survival in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, rigorous Cre-based lineage tracing using the MADM system provided definitive evidence for adult cardiomyocyte division in vivo with an efficiency of at least 15%. Intramyocardial delivery of the cell cycle regulators resulted in improved cardiac function after injury relative to controls, even when the cell-cycle regulators were delivered after partial consolidation of the scar tissue induced by coronary ligation.

The ability of regenerative organisms to repair damage through cellular proliferation has led to attempts at inducing cell-cycle re-entry of terminally differentiated mammalian cells. For example, combinations of microRNAs that induce cardiomyocyte proliferation have been reported (Aguirre et al., 2014; Eulalio et al., 2012; Tian et al., 2015). However, miRNAs are limited by the large number of genes that they target, and the efficiency with this approach was very low. Manipulation of the Hippo signaling pathway can also influence cardiomyocyte proliferation in the fetal and neonatal stages (Heallen et al., 2011). However, the Hippo pathway was not robust in inducing cardiac proliferation in adulthood (Morikawa et al., 2015; Xin et al., 2013), although deletion of the Hippo pathway mediator, Salvador, in mice resulted in improved cardiac function after MI (Leach et al., 2017). The expression of cell-cycle regulators has also been examined, and while DNA synthesis and karyokinesis may occur, demonstration of efficient cytokinesis with survival has been elusive. For example, CDK1 and CCNB function in a complex to promote the G2/M phase and together appear to induce cardiomyocyte karyokinesis, but cytokinesis and cell stability after division were not explored (Bicknell et al., 2004). Similarly, CDK4 and CCND cooperate through physical interaction to promote the G1/S phase and can promote DNA synthesis in cardiomyocytes, but not necessarily cytokinesis (Tamamori-Adachi et al., 2008). Finally, expression of Cyclin A modestly induced cardiomyocyte proliferation in vitro and could induce limited cardiomyocyte proliferation in vivo (Chaudhry et al., 2004; Shapiro et al., 2014). All of the aforementioned relied upon induction of PHH3 (a G2/M phase marker), observed in less than ~1% of cells (Zebrowski et al., 2016), but the demonstration of actual cytokinesis in vivo using rigorous genetic lineage-marking strategies as shown here provides more definitive evidence of proliferation.

The use of a Wee1 inhibitor and TGFβ inhibitor with the CDK4:CCND complex allowed efficient cell-cycle entry of cardiomyocytes in vitro and in vivo. Wee1 phosphorylates CDK1, resulting in inactivation of the CDK1:CCNB complex. Thus, inhibition of Wee1 would result in greater activity of the endogenous CDK1:CCNB complex and promotion of the G2/M phase (Harvey et al., 2005). Since TGFβ functions to directly activate p27 expression in a Smad-dependent manner and p27 represses function of G1 phase cyclins (Ravitz et al., 1996), the enhancement of cell-cycle progression upon TGFβ inhibition may be related to p27 inhibition, which we observed with 2F2i. The combination of these chemical inhibitors would thus promote enhancement of G2/M and G1/S phases and allow replacement of CDK1 and CCNB from the 4F cocktail.

Ongoing cellular division would be an unwanted outcome in any regenerative approach. We found that cardiomyocyte proliferation and the increase in PHH3 occurred only during the first 4–5 days, after which the cells did not divide any further. Cyclins and CDKs are highly regulated through ubiquitin-mediated pathways and we observed that, despite high levels of mRNA, the protein levels of the expressed 4Fs declined dramatically after a few days and this decline was dependent on proteasome activity. This autoregulatory loop is beneficial, as limited cell division is preferable. Although we did not observe any cardiac tumors in mice treated with 4F, likely due to the autoregulation of 4F protein expression, the potential for ectopic proliferation calls for caution and specificity of delivery in any future clinical development. The short time window desired for expression of the cell-cycle regulators makes modified mRNA a plausible approach for transient in vivo delivery, which may address the risks associated with ongoing expression of positive cell-cycle regulators (Zangi et al., 2013). The significantly improved cardiac function even after scar formation, along with the possibility of transient local delivery of the cell-cycle regulators, raises the potential for the translation of this technology.

In conclusion, here we describe a discrete combination of cell-cycle regulators that effectively induce cardiomyocyte proliferation in vitro and in vivo. As these cell-cycle regulators control cell division of many cell types, future studies will determine if a similar combination efficiently induces proliferation of other post-mitotic cells within organs that have limited regenerative capacity, including pancreatic beta cells, neurons, sensorineural hair cells in the ear, liver cells, and retinal cells, among others.

STAR*METHODS

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Deepak Srivastava (Deepak.Srivastava@Gladstone.ucsf.edu).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Animal studies were performed in accordance with the UCSF animal use guidelines, and the protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and were accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. For lineage tracing, we used mosaic analysis with double markers (MADM) mice, which required us to cross three transgenic lines to generate the ubiquitous labelling (Actin Cre MADM) obtained from JAX labs: Igs2tm2(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J (Cat no. 013751) Igs2tm1(ACTB-EGFP,-tdTomato)Luo/J (Cat no. 013749) and Tg(CAG-cre/Esr1*)5Amc (Cat no. 004682). However, for cardiomyocytes tissue specificity, instead of Tg(CAG-cre/Esr1*)5Amc, the MADM mice were crossed to either B6.FVB(129)-A1cfTg(Myh6-cre/Esr1*)1Jmk/J (Cat no. 005657) for α-MHC-MADM or Tg(Tnnt2-cre)5Blh (Cat no. 024240) for generation of cardiac troponin-T MADM. For the cardiac function studies, we used C57BL/6J mice (Cat no. 000664). For isolation of adult rat cardiomyocytes, we used Sprague Dawley rats from Charles River (Cat no. 400).

Method Details

Adenovirus cloning and screening

Adenovirus cloning and production of virus particles was conducted as described (Mohamed et al., 2013; Mohamed et al., 2016). Briefly, 15 selected cDNA were generated by RT-PCR using RNA isolated from fetal mouse or human hearts. In our experiments, CDK1 (Vector Biolabs) was constitutively active via T14A and Y15F mutations that block phosphorylation with WEE1. The cDNA was cloned into pENTR11 (Gateway Adenoviral System; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then underwent homologous recombination with the pAd/CMV/V5-DEST to generate recombinant viral DNA. The recombinant adenoviral DNA was transformed into HEK293 cells to produce viral particles and then purified using a cesium-chloride gradient. The initial screening was conducted in primary cardiomyocytes isolated from 7-day-old mice 48 hours after viral infection. To stain for the nuclear division marker EDU, we used the Click-iT® EdU Alexa Fluor® 488 Imaging Kit (Thermo Fisher), and to stain for the G2/M phase marker (PHH3), we used anti-histone H3 (phospho S10) antibody (Abcam #ab47297). Imaging was performed with a Keyence BZ9000 imaging system, and quantification was performed using BZ analyzer software.

Isolation of P7 neonatal cardiomyocytes

Primary mouse cardiomyocytes were isolated from 7-day-old C57/Bl6 mouse or αMHC GFP transgenic neonates by an established protocol (Oceandy et al., 2009). For the αMHC GFP transgenic hearts cardiomyocytes were isolated from all neonates’ hearts within the litter where 50% of the hearts are GFP+ to dilute the green cell number and obtain isolated green cardiomyocytes for efficient live cell imaging. Briefly, hearts were cut into small pieces, and ventricular tissue was digested by several rounds of 7-minute incubations in ADS buffer (0.68% NaCl (w/v), 0.476% Hepes (w/v), 0.012% NaH2PO4 (w/v), 0.1% glucose (w/v), 0.04% KCl (w/v), 0.01% MgSO4 (w/v), pH 7.35) containing 0.3 mg/ml collagenase A (Roche) and 0.6 mg/ml pancreatin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C with shaking. Digestions were pooled, and cells were centrifuged and resuspended in plating medium (68% DMEM, 17% medium 199, 10% horse serum, 5% FCS). Cells were then plated on tissue culture dishes, and incubated for 60 minutes at 37 °C in 5% CO2 to separate adherent cardiac fibroblasts. Supernatants containing cardiomyocytes were plated on laminin-coated tissue culture dishes and incubated overnight at 37 °C in 5% CO2 to allow cellular attachment. The following day, cells were washed with PBS, and the plating medium was replaced with maintenance medium (79.5% DMEM, 19.5% medium 199, 1% FCS) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Immunocytochemistry and immunohistochemistry

Cells or OCT sections were washed twice with PBS and then fixed in 4% formaldehyde (0.5 ml) for 15 minutes. Fixed cells/sections were washed three times with PBS, permeablized with 0.1% Triton-X 100 for 15 minutes, and then blocked with 10% horse serum in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then probed with the monoclonal rabbit anti-PHH3 (Abcam) and anti-Troponin-T antibody (Thermo Fisher) (1:100) diluted in 1% horse serum for 1.5 hours at room temperature, washed three times in PBS, and then labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse (1:200; Jackson Laboratory) diluted in 1% horse serum for 1.5 hours in the dark. Cells were then washed three times in PBS and once in water. Coverslips were mounted onto slides, and cell staining was visualized using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope and Keyence BZ9000. The percentage of co-localization of PHH3 and Troponin-T was quantified using BZ analyzer software.

Preparation and maintenance of iPS-CMs

The human iPS–derived cardiomyocytes (hiPS-CMs) were prepared as described (Lian et al., 2013). Briefly, iPS cells were plated at cell density of 3.5X105 cells/well on Matrigel coated 12-well plates using mTESR medium for 3 days. Then 6 μM CHIR99021 in RPMI/B27 supplement without insulin medium was added for 48 hours, followed by IWP4 (5 μM) for 24 hours. Then the cells were re-plated on fibronectin coated 6-well plates in RPMI/B27 supplement without insulin for 5 days and then switched to RPMI/B27 supplement with insulin. After 10 days, we purified the cardiomyocytes by culturing them in lactate medium (DMEM + 4 mM lactate + NEAA + P/S + Glutamax) for 5 days. Then the cardiomyocytes were maintained in RPMI/B27 supplement with insulin for 2–3 months. The cells were split every 2–3 weeks on fresh fibronectin.

FACS analysis and sorting

For live-cell sorting and quantitative analysis, cells were dissociated using TRYPLE (Thermo Fisher) and sorted using an LSRII (BD) machine.

Western blotting

Proteins from cell lysates containing 20 μg of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (BioRad). Membranes were then washed in PBS, treated with blocking buffer (Li-cor), and then incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-GAPDH antibody loading control (Abcam #Ab9484, 1:1000), anti-P27 antibody (Abcam #ab32034, 1:1000), anti-phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) (Cell Signaling #2348, 1:1000), anti-phospho-Chk2 (Thr68) (Cell Signaling #2197, 1:1000) and anti-phospho-ATM (Ser1981) (Cell Signaling #5883, 1:1000). Membranes were washed in PBS and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies (Li-Cor, IRDye 600LT; IRDye 800CW, 1:10,000) for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were washed and visualized with an Odyssey Fc Dual-mode Imaging System.

Animal experiments

All surgeries were performed as described (Qian et al., 2012). Briefly, 8–9-week-old mice were anaesthetized with 2.4% isoflurane/97.6% oxygen and placed in a supine position on a heating pad (37 °C). Animals were intubated with a 24G Angiocath and ventilated using a MiniVent Type 845 mouse ventilator (Hugo Sachs Elektronik-Harvard Apparatus; stroke volume, 250 μl; respiratory rate, 120 breaths per minute). Myocardial infarction (MI) was induced by permanent ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery with a 7-0 prolene suture, as described (Qian et al., 2012). Sham-operated animals served as surgical controls and were subjected to the same procedures as the experimental animals with the exception that the LAD was not ligated. Animals were randomized into two different groups of nine mice, which received intramyocardial injection of either 4F or control adenoviruses. The mouse surgeon was blinded to whether 4F or control adenovirus was administered in each animal.

Cardiac function was assessed by serial echocardiography before and after MI. Echocardiography was performed blindly with the Vevo 770 High-Resolution Micro-Imaging System (VisualSonics) with a 15-MHz linear-array ultrasound transducer. The left ventricle was assessed in both parasternal long-axis and short-axis views at a frame rate of 120 Hz. End-systole or end-diastole were defined as the phases in which the left ventricle appeared the smallest and largest, respectively, and used for ejection-fraction measurements. To calculate the shortening fraction, left-ventricular end-systolic and end-diastolic diameters were measured from the left-ventricular M-mode tracing with a sweep speed of 50 mm/s at the papillary muscle. B-mode was used for two-dimensional measurements of end-systolic and end-diastolic dimensions. Imaging and calculations were done by an individual who was blinded to the treatment applied to each animal and code was broken only after all data acquired.

At the end of the experiments (12 weeks after MI), animals were exposed to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess cardiac structure and function as described in more detail below. Animals were then sacrificed, and their hearts harvested for histological studies. Standard Masson’s Trichrome staining was performed on hearts 12 weeks after viral delivery and coronary artery ligation. To determine scar size, BZ analyzer software was used to measure the scar area (blue) and healthy area (red) on transverse sections spanning four levels within the left ventricle of an MI heart. From each level, we measured four slices of tissues as technical quadruplicates (for a total of 16 sections). Individuals assessing scar area were blinded to the treatment applied in each animal.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

At the end of 12 weeks, in vivo MRI imaging was performed blindly with a 7T preclinical horizontal bore magnet interfaced with an Agilent imaging console. Animals were anaesthetized via inhalation of 2% isoflurane with 98% oxygen and placed into a home-built, linear-polarized birdcage coil with 28-mm internal diameter (ID). Body temperatures during imaging experiments were kept at 34 ºC. Animal heartbeats, breathing, and temperature were monitored with an MRI-compatible, small-animal life-support system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY). Location and long and short axes of mouse hearts were determined from gradient echo scout images with the following parameters: repetition time (TR), 10 msec; echo time (TE), 4 msec; excitation flip angle, 20-degree; field of view (FOV), 6 cm2; matrix dimension, 128x128; slice thickness, 1 mm; number of repetitions, 2. To evaluate functional parameters of control and infarcted hearts, MRI images of short axes were acquired with a spin echo–pulse sequence. Parameters of the acquisition were TR=1 sec, TE=10 msec, in-plane image resolution 200 μm, and acquisition time ~20 min (dependent on heart rate). Cardiac and breath gating were employed. To measure the ejection fraction, stroke volume, cardiac output and scar size, nine or ten short-axis slices of the heart were acquired at diastole (LVEDV) (zero delay after R-heart-peak) and systole (LVESV) (45% of the R-R interval delay from the R-peak). The MRI analyses were conducted as described in (Franco et al., 1999). Briefly, to determine the LV volume during systole and diastole, the endocardial border was identified by hand, and volumes were calculated by summation of the endocardial area in all slices multiplied by the distance between the slice centers. Stroke volume was calculated as (SV=LVEDV-LVESV) and ejection fraction as (EF=SV/LVEDV). Cardiac output was computed as (CO=SVxHR), where the HR was the average heart rate during the scan. Individuals acquiring MRI images, and those calculating functional parameters were blinded to treatment applied to each animal and numerical code for each animal was broken only after all data acquired.

Adult cardiomyocyte isolation

Adult cardiomyocytes (CMs) were isolated as described (Qian et al., 2012), with minor modifications. Briefly, adult mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane and mechanically ventilated. Hearts were removed and perfused retrogradely via aortic cannulation with a constant flow of 3 ml/min in a Langendorf apparatus. Hearts were perfused at 37 °C for 5 minutes with Wittenberg Isolation Medium (WIM) containing 116 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 6.7 mM MgCl2, 12 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine, 3.5 mM NaHCO3, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 1.0 mM NaH2PO4, 21 mM HEPES, with 1.5 nM insulin, essential vitamins (GIBCO), and essential mM amino acids (GIBCO) (pH 7.4), followed by digestion solution (WIM supplemented with 0.8 mg/ml colleganse II and 10 μM CaCl2) for 10 minutes. Hearts were then removed from the Langendorf apparatus while intact (with tissues loosely connected). Desired areas (i.e., border/infarct zone) were then micro-dissected under the microscope, mechanically dissociated, triturated, and resuspended in a low-calcium solution (WIM supplemented with 5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 10 mM taurine, and 150 μM CaCl2). Cells were then spun at low speed, supernatant was removed, and calcium was gradually reintroduced through a series of washes. For calcium transient measurements, cells were used on the same day as isolation and, until recordings, were stored at room temperature (21 °C) in M199 (Gibco) supplemented with 5 mM creatine, 2 mM l-carnitine, 5 mM taurine, and 1.5 nM insulin. For immunocytochemistry, cells were plated onto laminin-coated culture slides, allowed to adhere, and fixed on the day of isolation. For RNAseq, cardiomyocytes were selected manually by micropipette based on the presence of either a single-color (red or green) or yellow-color signal under the fluorescent microscope immediately after isolation.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated with a commercial kit (Direct-Zol RNA Mini-prep, Zymo Research). Reverse transcription was carried out using a mixture of oligo(dT) and random hexamer primers (SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMIx for qRT-PCR, ThermoFisher Scientific). Real-time PCR analysis was conducted with Taqman Probes (Thermo Fisher) using the 7900HT FAST real-time PCR detection system (Applied Biosystems).

RNA-seq Analyses

RNA was extracted from adult cardiomyocytes isolated from MADM mice. All samples were acquired in four replicates for RNAseq. The RNA was isolated using the miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, #210874). Using the Ovation RNA-seq System v2 Kit (NuGEN), the total RNA (20–50 ng) was reverse transcribed to synthesize first-strand cDNA using a combination of random hexamers and a poly-T chimeric primer. The RNA template was then partially degraded by heating and the second-strand cDNA was synthesized using DNA polymerase. Double-stranded DNA was then amplified using single-primer isothermal amplification (SPIA). SPIA is a linear cDNA amplification process in which RNase H degrades RNA in DNA/RNA heteroduplex at the 5′-end of double-stranded DNA, after which the SPIA primer binds to the cDNA, and the polymerase starts replication at the 3′-end of the primer by displacing the existing forward strand. Random hexamers were then used to linearly amplify the second-strand cDNA. cDNA samples were fragmented to an average size of 200 bp using the Covaris S2 sonicator. Libraries were made from the fragmented cDNA using the Ovation Ultralow V2 kit (NuGen). After end repair and ligation, the libraries were PCR amplified with nine cycles. Library quality was assessed by a Bioanalyzer on High-Sensitivity DNA chips (Agilent), and concentration was quantified by qPCR (KAPA) (Dafforn et al., 2004; Kurn et al., 2005). The libraries were sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 sequencer with a single-read, 50-cycle sequencing run (Illumina). We utilized the RNA-seq-analysis pipeline reported previously (Theodoris et al., 2015). For the reader’s convenience and completeness of the current manuscript, we review the important steps/features and/or statistics of the pipeline below. Known adapters and low-quality regions of reads were trimmed using Fastq-mcf (http://code.google.com/p/ea-utils). Sample QC was assessed using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Reads were aligned to the mouse-reference assembly mm9 or human-reference assembly hg19 using Tophat 2.0.13 (Kim et al., 2013). Gene expression was tallied by Subread featureCounts (Liao et al., 2014) using Ensembl’s gene annotation for mm9 or hg19. Finally, we calculated differential expression P-values using edgeR (Robinson et al., 2010). Here, we first filtered out any genes without at least two samples with a CPM (counts per million) between 0.5 and 5000. CPMs below 0.5 indicates non-detectable gene expression, and CPM above 5000 is typically only seen in mitochondrial genes. If these high-expression genes were not excluded, their counts would disproportionately affect the normalization. After excluding these genes, we re-normalized the remaining ones using “calcNormFactors” in edgeR, then calculated P-values for each gene with differential expression between samples using edgeR’s assumed negative–binomial distribution of gene expression. We calculated the false discovery rates (FDRs) for each P-value with the Benjamini-Hochberg method (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995), based on the built-in R function “p.adjust”. PCA plots were generated using the PCA R packages (FacorMineR, ggplotR and Cairo) using the default settings. PC1 and PC2 were plotted as the most abundant components.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Comparison of independent variables (e.g., quantification of western blotting, immunohistochemistry, pHH3 and EDU staining for proliferation) was conducted by one-sided t-test with significance threshold p<0.05 with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple hypothesis testing. Comparison between multiple groups (e.g., MRI mouse data) was conducted by one-way ANOVA with significance threshold p<0.05. Analysis of RNA-seq differential expression was conducted by negative binomial test with FDR correction of 10% using USeq.

Data and Software Availability

Transcriptome data for Figure 1A is available in Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession number GSE14414 and RNAseq data for Extended Data Figure S5 is under accession number GSE97730 and for reviewer access: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=kdgfggewrfsntoj&acc=GSE97730.

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-histone H3 (phospho S10) antibody. | Abcam | Cat#AB47297 |

| Cardiac Troponin T Monoclonal Antibody (13-11) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#MA5-12960 |

| anti-GAPDH antibody | Abcam | Cat#AB9484 |

| anti-P27 antibody | Abcam | Cat#AB32034 |

| anti-phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) | Cell Signaling | Cat#2348 |

| anti-phospho-Chk2 (Thr68) | Cell Signaling | Cat#2197 |

| anti-phospho-ATM (Ser1981) | Cell Signaling | Cat#5883 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| pENTR11 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A10467 |

| pAd/CMV/V5-DEST | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#V49320 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| SB144352 | Tocris | Cat#1614 |

| MK1775 | Selleckchem | Cat#S1525 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Click-iT™ EdU Alexa Fluor™ 647 Imaging Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#C10340 |

| Click-iT™ EdU Alexa Fluor™ 488 Imaging Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#C10337 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Transcriptome data for figure 1A | GEO | GSE14414 |

| RNAseq data for Extended data figures S5 | GEO | GSE97730 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Igs2tm2(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J | JAX Laboratories | Cat#013751 |

| Igs2tm1(ACTB-EGFP,-tdTomato)Luo/J | JAX Laboratories | Cat#013749 |

| Tg(CAG-cre/Esr1*)5Amc | JAX Laboratories | Cat#004682 |

| B6.FVB(129)-A1cfTg(Myh6-cre/Esr1*)1Jmk/J | JAX Laboratories | Cat#005657 |

| Tg(Tnnt2-cre)5Blh | JAX Laboratories | Cat#024240 |

| C57BL/6J mice | JAX Laboratories | Cat#000664 |

| Sprague Dawley rats | Charles River | Cat#400 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| GeneSolution siRNA targeting P27 (CDKN1B) Target sequence ACCGACGATTCTTCTACTCAA |

Qiagen | Cat#1027416 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Gateway™ pENTR™ 11 Dual Selection Vector | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A10467 |

| pAd/CMV/V5-DEST™ Gateway™ Vector Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#V49320 |

Supplementary Material

Day 7 primary mouse cardiomyocytes infected with CDK1:CCNB:AURKB adenoviruses. Time-lapse imaging using Incucyte live cell imaging system started 6 hours post-infection (1 hour/frame). Note at end of frame, cells die abruptly.

Day 60 hiPS-derived cardiomyocytes infected with CDK1:CCNB:AURKB adenoviruses. Time-lapse imaging using Incucyte live-cell imaging system started 6 hours post-infection (1/2 hour / Frame).

Supplementary Video 3: Time-lapse imaging of primary mouse cardiomyocytes infected with the 4F (related to Figure 2). Day 7 primary mouse cardiomyocytes infected with CDK1:CDK4:CCNB:CCND adenoviruses. Time-lapse imaging using Incucyte live-cell imaging system started 6 hours post-infection (1 hour/Frame).

Figure S1. CDK1/CCNB/AURKB (3F)-Induced Cell Division in Mouse and Human Cardiomyocytes and DNA Damage Response, Related to Figures 1–2 and Supplementary Videos 1–2)

(A) Time lapse imaging of cell division in P7 mouse cardiomyocytes isolated from α-MHC-GFP transgenic mice overexpressing CDK1, CCNB and AURKB (3F). Panels are representative of images recorded every hour for 4 days and demonstrate cell division of a cardiomyocyte, followed by rapid cell death seen in last panel (see Supplementary Video 1 and 2).

(B) Time lapse imaging of cell division in 60-day-old hiPS-derived cardiomyocytes overexpressing 3F. Panels are representative of images collected every hour for 2 days. Last panel represents immunocytochemistry for cardiac Troponin T (cTnT) in the 36-hour cells. Arrows denote dividing cells and their progeny.

(C) Representative western blots and quantification for the indicated DNA damage response markers (p-ATM, p-Chk1 and p-Chk2) in response to virus encoding 4F, 3F or LacZ (control) in human iPS-CMs (n=3 independent experiments with two replicates in each; *p<0.05, bars indicate means with SEM).

Figure S2. Validation of the Mosaic Analysis with Double Markers (MADM) System to Detect 4F-Induced Cardiomyocyte Proliferation In Vivo, Related to Figure 3

(A) Schematic diagram showing the principle behind the lineage tracing of proliferating cells in MADM mice (adapted from (Gitig, 2010)).

(B, C) Representative histologic images of cardiomyocyte-specific α-MHC-Cre MADM hearts infected with 4F at the time of infarct and sectioned 4 days later. Single-colored cardiomyocytes stained positive for PHH3 (B) and EDU incorporation (C). Low and high magnification of indicated areas are shown,

Figure S3. Validation of α-MHC-Cre MADM Fluorescent Reporter and Examples of Single-Colored Cells in Infarct and Peri-Infarct Regions, Related to Figure 3

(A) Representative GFP- or RFP-immunostained and unstained adjacent heart sections from α-MHC-Cre MADM mice showing that the signal intensity was similar in immunostained sections compared to sections visualized by fluorescence, validating use of the fluorescent reporter in this system. Arrows are pointing to two single-colored cells showing similar signal intensities in the two adjacent sections.

(B) Representative images from α-MHC-Cre MADM mouse heart sections treated with 4F showing single-colored cardiomyocytes at the infarct zone (top two panels). Bottom panel shows a representative peri-infarct region without scar where there are many events of recombination including a single-colored cardiomyocyte.

Figure S4. Spatial Location and Nucleation of Divided Cardiomyocytes In Vivo, Related to Figure 3

(A) Bar graph shows quantification of the absolute numbers of single-colored and yellow-colored cardiomyocytes in α-MHC-Cre MADM 2 weeks after infarction and injection with either LacZ (Control) or 4F adenoviruses (n=8 animals in each group and 10 sections from each animal).

(B) Bar graph shows quantification of the percent single-colored cells at the infarct, border and remote zones in α-MHC-Cre MADM mice injected with 4F adenoviruses at the time of the infarct and harvested 2 weeks later (n=8000 cells analyzed from 8 animals).

(C) Bar graph shows quantification of single-colored cardiomyocyte nucleation where over 90% of the single-colored cardiomyocytes were mononucleated in cTnT-Cre MADM mice hearts injected with 4F at the time of MI and harvested 2 weeks later (n=2000 cells analyzed from 10 different heart sections from three animals).

Figure S5. RNA Sequencing of Cardiomyocytes Isolated from MADM Mice after Cytokinesis, Related to Figure 3

(A) Principal component analysis (PCA) of RNA-seq data from isolated single-colored adult cardiomyocytes from MADM mice 2 weeks after injection with the 4F (post-cytokinesis) compared to yellow-colored cardiomyocytes (indeterminate) from the same animals (n=4), and also compared to averages of control adult cardiomyocytes (CM), neonatal CMs and cardiac fibroblasts (n=3). Adult single-colored cells (red) had greater variability than the yellow cells that were mostly cells that had not undergone cell division.

(B, C) Gene Ontology (GO) term analysis of the genes downregulated (B) and upregulated (C) by more than two-fold with p<0.05 significance between the single-colored vs yellow CMs.

Figure S6. 4F Induces Cardiomyocyte Proliferation in Non-Infarcted α-MHC-Cre MADM Heart, Related to Figure 3

(A, B) Representative immunofluorescence images (A) and quantification of single-colored cells (B), indicating cardiomyocyte cytokinesis, in α-MHC-Cre MADM mice in histological sections without myocardial infarction.

(C) Direct comparison of quantification of the single-colored cells in infarcted and non-infarcted hearts treated with either 4F or control LacZ virus. Low magnification views indicate breadth of recombination in cardiomyocytes, and insets show higher magnification of single- or double-colored cells. Mice were infected intramyocardially with adenoviruses encoding CDK1, CCNB, CDK4, and CCND (4F) or control Lac-Z virus and the hearts were harvested 2 weeks later (n=6 animals in each group, *p<0.05). Bars indicate means and SEM.

Figure S7. 4F Does Not Affect Fibroblast Proliferation In Vivo or In Vitro Related to Figure 4

(A) Quantification of isolated Thy1+ cells from ubiquitous β-Actin-Cre-MADM mice by using a Langendorff preparation, digesting the heart, and sorting a cardiac fibroblast-enriched population marked with the APC-conjugated-Thy1 antibody. FACS was used to quantify the number of single-colored fibroblasts and revealed no difference between animals treated with 4F or LacZ control virus (n=4 animals in each group).

(B) Representative FACS plots showing infection efficiency of GFP adenovirus in Thy1+ cardiac fibroblasts infected with 10 or 100 MOI, compared to iPS-CMs infected with 10 MOI of the virus.

(C) Representative FACS plots (left panels) and immunostaining (right panels) of EDU incorporation in DDR2+ cells (pre-sorted for Thy1+) infected with either LacZ control virus, or CDK1-CDK4-CCNB-CCND (4F) for 48 hours (n=3 independent experiments and 3 technical replicates in each).

(D) Quantification of FACS analysis (C) from pre-sorted Thy1+cardiac fibroblasts co-stained with DDR2 (fibroblast marker) and EDU and infected with either LacZ control virus, or 4F viruses for 48 hours (n=3 independent experiments with 3 replicates in each). Bars indicate means and SEM.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Morgan for advice and review of the manuscript; I. Kathiriya, A. Williams, L. Liu, and M. Calvert for assistance and helpful suggestions. We also thank B. Taylor for help in preparing the figures and editing the manuscript and C. Herron and G. Howard for assistance in editing. We also thank the Gladstone Institutes Genomics, Flow Cytometry, Histology and Bioinformatics Core facilities. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 HL057181 (D.S.), U01 HL098179 (D.S.), and U01 HL100406 (D.S.) and AHA Scientist Development Grant 16SDG29950012 (T.M.A.M.). D.S. was supported by the L.K. Whittier and Roddenberry Foundations, the Younger Family Fund, and the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. This work was also supported by NIH/NCRR grant C06 RR018928 to the Gladstone Institutes.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

A patent application by T.M.A Mohamed and D. Srivastava entitled “Method for Inducing Cell Division of Cardiomyocytes” has been filed (published PCT Application Number: WO2016/164371).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

TMAM: conception and design, collection and analysis of data, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript; YSA, PZ, ER, YH, AE, and SM: collection and analysis of data; DS: conception and design, analysis of data, financial support, manuscript writing, and final approval of manuscript.

References

- Aguirre A, Montserrat N, Zacchigna S, Nivet E, Hishida T, Krause MN, Kurian L, Ocampo A, Vazquez-Ferrer E, Rodriguez-Esteban C, et al. In vivo activation of a conserved microRNA program induces mammalian heart regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:589–604. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre A, Sancho-Martinez I, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Reprogramming toward heart regeneration: stem cells and beyond. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali SR, Hippenmeyer S, Saadat LV, Luo L, Weissman IL, Ardehali R. Existing cardiomyocytes generate cardiomyocytes at a low rate after birth in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8850–8855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408233111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang YS, Rivas RN, Ribeiro AJ, Srivas R, Rivera J, Stone NR, Pratt K, Mohamed TM, Fu JD, Spencer CI, et al. Disease Model of GATA4 Mutation Reveals Transcription Factor Cooperativity in Human Cardiogenesis. Cell. 2016;167:1734–1749. e1722. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bersell K, Arab S, Haring B, Kuhn B. Neuregulin1/ErbB4 signaling induces cardiomyocyte proliferation and repair of heart injury. Cell. 2009;138:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicknell KA, Coxon CH, Brooks G. Forced expression of the cyclin B1-CDC2 complex induces proliferation in adult rat cardiomyocytes. Biochem J. 2004;382:411–416. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutros R, Lobjois V, Ducommun B. CDC25 phosphatases in cancer cells: key players? Good targets? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:495–507. doi: 10.1038/nrc2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry HW, Dashoush NH, Tang H, Zhang L, Wang X, Wu EX, Wolgemuth DJ. Cyclin A2 mediates cardiomyocyte mitosis in the postmitotic myocardium. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35858–35866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404975200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafforn A, Chen P, Deng G, Herrler M, Iglehart D, Koritala S, Lato S, Pillarisetty S, Purohit R, Wang M, et al. Linear mRNA amplification from as little as 5 ng total RNA for global gene expression analysis. Biotechniques. 2004;37:854–857. doi: 10.2144/04375PF01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulalio A, Mano M, Dal Ferro M, Zentilin L, Sinagra G, Zacchigna S, Giacca M. Functional screening identifies miRNAs inducing cardiac regeneration. Nature. 2012;492:376–381. doi: 10.1038/nature11739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fededa JP, Gerlich DW. Molecular control of animal cell cytokinesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:440–447. doi: 10.1038/ncb2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco F, Thomas GD, Giroir B, Bryant D, Bullock MC, Chwialkowski MC, Victor RG, Peshock RM. Magnetic resonance imaging and invasive evaluation of development of heart failure in transgenic mice with myocardial expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Circulation. 1999;99:448–454. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimitsu K, Grimaldi M, Yamano H. Cyclin-dependent kinase 1-dependent activation of APC/C ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2016;352:1121–1124. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemberling M, Karra R, Dickson AL, Poss KD. Nrg1 is an injury-induced cardiomyocyte mitogen for the endogenous heart regeneration program in zebrafish. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.05871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitig D. Transcriptomics: individuality in the cellular world. Biotechniques. 2010;48:439–443. doi: 10.2144/000113435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SL, Charlet A, Haas W, Gygi SP, Kellogg DR. Cdk1-dependent regulation of the mitotic inhibitor Wee1. Cell. 2005;122:407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heallen T, Zhang M, Wang J, Bonilla-Claudio M, Klysik E, Johnson RL, Martin JF. Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science. 2011;332:458–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1199010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Harrison MR, Osorio A, Kim J, Baugh A, Duan C, Sucov HM, Lien CL. Igf Signaling is Required for Cardiomyocyte Proliferation during Zebrafish Heart Development and Regeneration. PloS one. 2013;8:e67266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hydbring P, Malumbres M, Sicinski P. Non-canonical functions of cell cycle cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:280–292. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ieda M, Fu JD, Delgado-Olguin P, Vedantham V, Hayashi Y, Bruneau BG, Srivastava D. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell. 2010;142:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ieda M, Tsuchihashi T, Ivey KN, Ross RS, Hong TT, Shaw RM, Srivastava D. Cardiac fibroblasts regulate myocardial proliferation through beta1 integrin signaling. Dev Cell. 2009;16:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling C, Sleep E, Raya M, Marti M, Raya A, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Zebrafish heart regeneration occurs by cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nature. 2010;464:606–609. doi: 10.1038/nature08899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi K, Holdway JE, Werdich AA, Anderson RM, Fang Y, Egnaczyk GF, Evans T, Macrae CA, Stainier DY, Poss KD. Primary contribution to zebrafish heart regeneration by gata4(+) cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2010;464:601–605. doi: 10.1038/nature08804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurn N, Chen P, Heath JD, Kopf-Sill A, Stephens KM, Wang S. Novel isothermal, linear nucleic acid amplification systems for highly multiplexed applications. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1973–1981. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.053694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach JP, Heallen T, Zhang M, Rahmani M, Morikawa Y, Hill MC, Segura A, Willerson JT, Martin JF. Hippo pathway deficiency reverses systolic heart failure after infarction. Nature. 2017;550:260–264. doi: 10.1038/nature24045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lestuzzi C. Primary tumors of the heart. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2016;31:593–598. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Cavallero S, Gu Y, Chen TH, Hughes J, Hassan AB, Bruning JC, Pashmforoush M, Sucov HM. IGF signaling directs ventricular cardiomyocyte proliferation during embryonic heart development. Development. 2011;138:1795–1805. doi: 10.1242/dev.054338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li VC, Kirschner MW. Molecular ties between the cell cycle and differentiation in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:9503–9508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408638111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian X, Zhang J, Azarin SM, Zhu K, Hazeltine LB, Bao X, Hsiao C, Kamp TJ, Palecek SP. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nature protocols. 2013;8:162–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:153–166. doi: 10.1038/nrc2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed TM, Abou-Leisa R, Baudoin F, Stafford N, Neyses L, Cartwright EJ, Oceandy D. Development and characterization of a novel fluorescent indicator protein PMCA4-GCaMP2 in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;63:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed TM, Abou-Leisa R, Stafford N, Maqsood A, Zi M, Prehar S, Baudoin-Stanley F, Wang X, Neyses L, Cartwright EJ, et al. The plasma membrane calcium ATPase 4 signalling in cardiac fibroblasts mediates cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11074. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa Y, Zhang M, Heallen T, Leach J, Tao G, Xiao Y, Bai Y, Li W, Willerson JT, Martin JF. Actin cytoskeletal remodeling with protrusion formation is essential for heart regeneration in Hippo-deficient mice. Sci Signal. 2015;8:ra41. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama KI, Nakayama K. Ubiquitin ligases: cell-cycle control and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:369–381. doi: 10.1038/nrc1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oceandy D, Pickard A, Prehar S, Zi M, Mohamed TM, Stanley PJ, Baudoin-Stanley F, Nadif R, Tommasi S, Pfeifer GP, et al. Tumor suppressor ras-association domain family 1 isoform A is a novel regulator of cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2009;120:607–616. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.868554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polizzotti BD, Ganapathy B, Walsh S, Choudhury S, Ammanamanchi N, Bennett DG, dos Remedios CG, Haubner BJ, Penninger JM, Kuhn B. Neuregulin stimulation of cardiomyocyte regeneration in mice and human myocardium reveals a therapeutic window. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:281ra245. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Simpson E, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Olson EN, Sadek HA. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science. 2011;331:1078–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1200708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puente BN, Kimura W, Muralidhar SA, Moon J, Amatruda JF, Phelps KL, Grinsfelder D, Rothermel BA, Chen R, Garcia JA, et al. The oxygen-rich postnatal environment induces cardiomyocyte cell-cycle arrest through DNA damage response. Cell. 2014;157:565–579. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian L, Huang Y, Spencer CI, Foley A, Vedantham V, Liu L, Conway SJ, Fu JD, Srivastava D. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2012;485:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nature11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravitz MJ, Yan S, Dolce C, Kinniburgh AJ, Wenner CE. Differential regulation of p27 and cyclin D1 by TGF-beta and EGF in C3H 10T1/2 mouse fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 1996;168:510–520. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199609)168:3<510::AID-JCP3>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubart M, Field LJ. Cardiac regeneration: repopulating the heart. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:29–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.124530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SD, Ranjan AK, Kawase Y, Cheng RK, Kara RJ, Bhattacharya R, Guzman-Martinez G, Sanz J, Garcia MJ, Chaudhry HW. Cyclin A2 induces cardiac regeneration after myocardial infarction through cytokinesis of adult cardiomyocytes. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:224ra227. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi T. Regulation of cardiomyocyte proliferation during development and regeneration. Dev Growth Differ. 2014;56:402–409. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamori-Adachi M, Takagi H, Hashimoto K, Goto K, Hidaka T, Koshimizu U, Yamada K, Goto I, Maejima Y, Isobe M, et al. Cardiomyocyte proliferation and protection against post-myocardial infarction heart failure by cyclin D1 and Skp2 ubiquitin ligase. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;80:181–190. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoris CV, Li M, White MP, Liu L, He D, Pollard KS, Bruneau BG, Srivastava D. Human disease modeling reveals integrated transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of NOTCH1 haploinsufficiency. Cell. 2015;160:1072–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]