ABSTRACT

Secondary envelopment of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) occurs through a mechanism that is poorly understood. Many enveloped viruses utilize the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRTs) for viral budding and envelopment. Although there are conflicting reports on the role of the ESCRT AAA ATPase protein VPS4 in HCMV infection, VPS4 may act in an envelopment role similar to its function during other viral infections. Because VPS4 is normally recruited by the ESCRT-III complex, we hypothesized that ESCRT-III subunits would also be required for HCMV infection. We investigated the role of ESCRT-III, the core ESCRT scission complex, during the late stages of infection. We show that inducible expression of dominant negative ESCRT-III subunits during infection blocks endogenous ESCRT function but does not inhibit virus production. We also show that HCMV forms enveloped intracellular and extracellular virions in the presence of dominant negative ESCRT-III subunits, suggesting that ESCRT-III is not involved in the envelopment of HCMV. We also found that as with ESCRT-III, inducible expression of a dominant negative form of VPS4A did not inhibit the envelopment of virions or reduce virus titers. Thus, HCMV does not require the ESCRTs for secondary envelopment. However, we found that ESCRT-III subunits are required for efficient virus spread. This suggests a role for ESCRT-III during the spread of HCMV that is independent of viral envelopment.

IMPORTANCE Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a prevalent opportunistic pathogen in the human population. For neonatal and immunocompromised patients, HCMV infection can cause severe and possibly life-threatening complications. It is important to define the mechanisms of the viral replication cycle in order to identify potential targets for new therapies. Secondary envelopment, or acquisition of the membrane envelope, of HCMV is a mechanism that needs further study. Using an inducible fibroblast system to carefully control for the toxicity associated with blocking ESCRT-III function, this study determines that the ESCRT proteins are not required for viral envelopment. However, the study does discover a nonenvelopment role for the ESCRT-III complex in the efficient spread of the virus. Thus, this study advances our understanding of an important process essential for the replication of HCMV.

KEYWORDS: CHMP, ESCRT, HCMV, VPS4, assembly, envelopment, spread

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a herpesvirus of clinical significance for immunosuppressed individuals and developing fetuses. One essential replication process, secondary envelopment or acquisition of the membrane envelope, remains largely uncharacterized, with very little known about the molecular details of this process. Viruses have adapted a variety of strategies for obtaining their envelope layer. In some cases, influenza A virus and the M2 protein, for example, the process is driven entirely by viral products (1). In other cases, envelopment requires the coordinated efforts of both viral and cellular proteins. Since the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) machinery promotes budding outward from the cytoplasm, these cellular complexes are often recruited by viral proteins as part of the envelopment process, as was first reported for HIV-1 (2). The ESCRTs were originally described in the context of the formation of the intraluminal vesicles (ILV) of multivesicular bodies (MVB), in which the ESCRT complexes are sequentially recruited to promote cargo clustering and vesicle formation. These complexes, recruited in sequential order, include ESCRT-0, ESCRT-I, ESCRT-II, ESCRT-III, and the VPS4 AAA ATPase. In the context of viral budding, different subsets of these ESCRT complexes may be recruited. This appeared to be the case for HCMV, in which two independent studies reported that two ESCRT proteins, ALIX and Tsg101, are not required for the production of infectious virions (3, 4). While the studies agreed that these ESCRT complexes are not required, they differed with regard to the requirement of the downstream ESCRTs for productive HCMV infection (summarized in Fig. 1A). In one case, small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of the late ESCRT AAA ATPase VPS4 did not affect HCMV titers (4), while the other study reported that dominant negative constructs of both VPS4A and its associated factor CHMP1A block infection (3). Because CHMP1A, along with its binding partner IST1, modulates a subset of VPS4 activities (5), roles for both VPS4A and CHMP1A during HCMV infection, specifically at the envelopment step, seemed a probable model. Although specific roles for VPS4A and CHMP1A in envelopment were not investigated, from this study it was proposed that, like other viruses, HCMV utilizes a subset of the ESCRT machinery to promote envelopment.

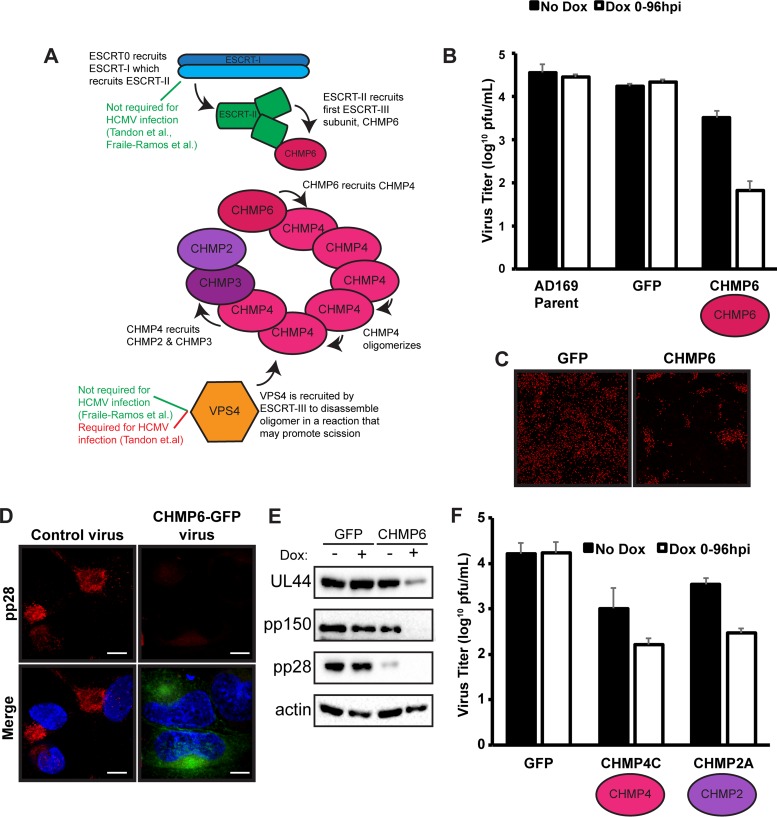

FIG 1.

High levels of dominant negative ESCRT-III subunits prevent the initiation of HCMV infection. (A) Model of ESCRT recruitment during ILV formation. (B) Titers of viruses expressing a parental control, GFP, or CHMP6-GFP at 96 hpi (MOI, 3) in the presence or absence of 100 ng/ml doxycycline (Dox). Viral titers are from three independent replicates. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of immediate early proteins (red) 9 dpi (MOI, 0.05) in the presence of Dox. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of pp28 (red) at 96 hpi in cells infected with a virus expressing CHMP6-GFP or a control virus at 96 hpi. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Bars, 10 μm. (E) Western blot analysis of viral proteins pUL44, pp150, and pp28 at 96 hpi (MOI, 3) from fibroblasts infected with viruses expressing GFP or CHMP6-GFP. (F) Titers of viruses expressing CHMP4C-GFP or CHMP2A-GFP. Viral titers are from three independent experiments.

In agreement with a role in envelopment, both VPS4A and CHMP1A are recruited to the viral cytoplasmic assembly compartment (cVAC) during infection (6). This recruitment may be mediated either directly by a viral protein or by the ESCRT-III complex, similarly to VPS4 recruitment during ILV formation. ESCRT-III consists of four core subunits (CHMP6, CHMP4, CHMP3, and CHMP2) that oligomerize on the membrane to form a scission-promoting complex (Fig. 1A). CHMP6, the first subunit recruited during ILV formation, binds to ESCRT-II and initiates the recruitment of the other ESCRT-III subunits and oligomer formation. HCMV may utilize ESCRT-III to recruit VPS4 during infection, or VPS4 may be recruited by viral proteins. A number of viral proteins are known to be important for late stages of HCMV assembly and morphogenesis, but only the viral protein UL71 and its interacting protein UL103 have been implicated in the late stage of membrane scission during envelopment. Since this phenotype is consistent with a block in scission activity in other viruses requiring the ESCRTs, a protein such as UL71 may also be important for the recruitment of ESCRT-III and VPS4. Roles in envelopment for the viral protein UL71 and its interacting protein UL103 have recently become well established (7–10). Furthermore, the alphaherpesvirus homologues UL7 and UL51 also play roles in virus assembly and spread (11–13). Thus, UL71 may function by recruiting the ESCRT-III complex, which subsequently recruits VPS4. Alternatively, UL71 may directly recruit VPS4. Since the core ESCRT-III subunits had not yet been investigated during HCMV infection, we began our study with the presumption that they are involved in envelopment. Surprisingly, not only did we discover that ESCRT-III is not required for the production of infectious virions; we also found that VPS4 is not involved in the production of infectious virions. This is consistent with the original report in which VPS4 actually had a slight inhibitory effect on infectious titers (4). While our findings provide definitive evidence that HCMV does not require the ESCRT machinery for envelopment, we did find that blocking the ESCRT pathway decreased the efficiency of virus spread. This indicates an alternative function for the ESCRT pathway in the mechanism of HCMV spreading, outside of a direct role in virion production.

RESULTS

ESCRT-III subunits are not required for the production of infectious HCMV virions.

To investigate whether HCMV required the ESCRT-III complex for infection, we began by testing a role for CHMP6, the first ESCRT-III subunit recruited in ILV formation (Fig. 1A). Taking advantage of the dominant negative effect that ESCRT-III subunits tagged with fluorophores have on complex activity (14), we engineered the HCMV genome to express green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged CHMP6 in order to measure its effect on virion production. This approach ensures that every infected cell expresses CHMP6-GFP, and to regulate its expression, we placed it under the control of an inducible promoter. As a control, we generated a virus expressing only GFP under the control of the same inducible promoter. After induction of CHMP6-GFP, we observed a 2-log reduction in the titers of infectious virions (cell associated plus extracellular) recovered at 96 h postinfection (hpi) from those of the GFP or AD169 parental control virus (Fig. 1B). Accordingly, virus spread was also significantly reduced and in some cases was limited to single, isolated cells (Fig. 1C). In contrast, the control virus spread throughout nearly the entire monolayer.

We next sought to correlate this block in infection to envelopment by first determining whether viral proteins were being properly trafficked to the cVAC despite the block to the ESCRT pathway. Surprisingly, we could detect very little of the late viral protein and cVAC marker, pp28, by immunofluorescence analysis of cells that were infected for 96 h in the presence of the tetracycline (TET) inducer doxycycline (Dox) (Fig. 1D), which we confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1E). Additionally, analysis of other viral proteins revealed that almost no pp150 and a markedly reduced amount of pUL44 were present (Fig. 1E), indicating inability to initiate a robust infection in the presence of the dominant negative CHMP6 protein. Expressing ESCRT-III dominant negative constructs at high levels results in cell toxicity and, as in our observation with HCMV proteins, reduces expression of the retroviral Gag protein (14). The significant reduction in viral protein production suggested that expressing the dominant negative ESCRT-III subunits from the viral genome resulted in a level of expression that perturbed cellular conditions sufficiently to prevent a robust infection from establishing. Even in the absence of doxycycline induction, we observed decreases in both infectious virus titers and levels of the viral protein pp28 (Fig. 1B and E). We believe that this is due to leaky expression from the high number of copies present after HCMV genome replication. Accordingly, CHMP6-GFP protein can be detected by Western blot analysis in both the presence and the absence of doxycycline (Fig. 2B). While we cannot rule out the possibility that this phenotype was due to a second-site mutation in the virus expressing CHMP6-GFP, we do not favor this possibility, since similar results were observed using viruses engineered to express other ESCRT-III subunits, CHMP4C-GFP and CHMP2A-GFP, and titers were further reduced upon doxycycline induction (Fig. 1F and data not shown). These results emphasized the importance of tightly regulating dominant negative expression and revealed the need for an alternative approach to assessing the role of ESCRT-III subunits during infection.

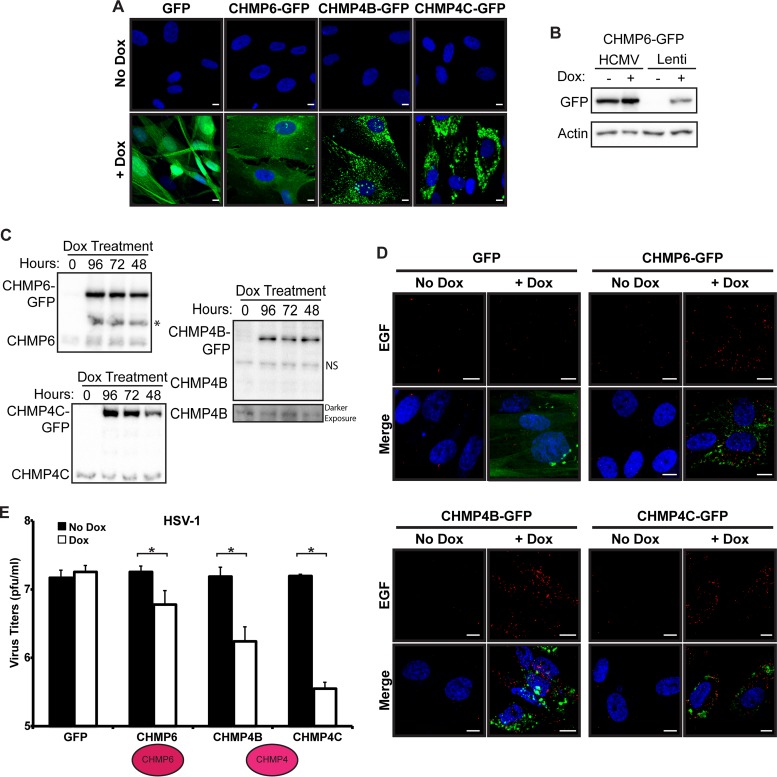

FIG 2.

ESCRT function is inhibited in inducible ESCRT-III fibroblasts. (A) GFP expression of inducible fibroblasts expressing GFP, CHMP6-GFP, CHMP4B-GFP, or CHMP4C-GFP 24 h post-Dox addition. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Bars, 10 μm. (B) Western blot analysis of HCMV-infected cells expressing CHMP6-GFP from the HCMV genome (HCMV) or of fibroblasts following lentiviral transduction (Lenti) and selection for cells containing the inducible construct. Dox was present throughout the infection (96 h). (C) Western blot analysis of endogenous and GFP-tagged CHMP6, CHMP4B, and CHMP4C at 96 hpi after Dox induction for 0, 48, 72, or 96 h. NS, nonspecific band detected by the CHMP4B antibody; *, unknown band detected by the CHMP6 antibody only in Dox-induced samples. (D) EGF degradation in ESCRT-III dominant negative (green) fibroblasts. EGF (red) was imaged 3 h after a 30-min pulse in the presence or absence of Dox. Nuclei are labeled with DAPI. Bars, 10 μm. (E) HSV-1 infection of fibroblasts expressing GFP, CHMP6-GFP, or CHMP4-GFP at 24 hpi (MOI, 5). Dox was added 24 h prior to infection. Significant differences (P < 0.05) between samples are marked with asterisks. Infections were carried out in three independent experiments.

To better control the expression of the ESCRT-III dominant negative subunits, we utilized a lentivirus system with expression of the subunits under the control of an inducible promoter. Following lentivirus transduction of both the inducible dominant negative ESCRT-III construct and a Tet activator, cells were passaged three times under selection to generate a population of cells containing both the Tet activator protein and the dominant negative expression vector, ensuring that the entire population of infected cells would express both desired constructs. Using this system, we generated cells expressing GFP and dominant negative versions of five of the seven mammalian ESCRT-III subunits (CHMP6, CHMP4B and -C, CHMP3, and CHMP2A) and confirmed the inducibility of construct expression in the presence of doxycycline by monitoring the presence of GFP (Fig. 2A and data not shown). We observed expression of GFP (or the corresponding CHMP-GFP) in >90% of induced cells. Importantly, we could detect no GFP fluorescence in fibroblasts transduced with inducible lentivirus constructs in the absence of doxycycline (Fig. 2A and B). However, the expression level of CHMP6-GFP after induction was lower than the levels expressed from the genome, with or without doxycycline. While this may be beneficial for avoiding the adverse effects on infection that we observed with the elevated dominant negative levels, we were concerned that we might not be expressing our constructs at a level sufficient to block ESCRT function. Western blot analysis confirmed that the dominant negative GFP-tagged constructs expressed in the transduced fibroblasts were in fact in excess over the endogenous protein (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, to ensure that our system was capable of expressing dominant negative ESCRT-III subunits at a level sufficient to block pathway function, we used an assay that monitors the degradation of a fluorescently labeled epidermal growth factor (EGF) reporter. Upon binding its receptor, EGF is endocytosed and delivered to the lysosome for degradation in an ESCRT-dependent manner. In the absence of doxycycline, EGF was degraded in all samples. However, after doxycycline induction, clear EGF punctae were present in all of the ESCRT-III dominant negative samples, but not in the GFP sample, indicating a block in the ability to degrade EGF (Fig. 2D). This suggests that ESCRT function was successfully inhibited.

While this result indicates a successful block to ESCRT function, we sought a second assay to confirm that our cells expressing the dominant negative constructs were functioning as expected. ESCRT-III subunits have previously been found to be important for herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) replication (15, 16). Using our induction system, we next showed that HSV-1 titers were reduced when the expression of CHMP6-GFP, CHMP4B-GFP, or CHMP4C-GFP was induced in the respective dominant negative-containing fibroblasts (Fig. 2E). The block was more potent with the CHMP4 isoforms than with CHMP6-GFP, an observation similar to what was originally published (15). Importantly, there was no difference in titers after induction of the GFP control. These results confirm that ESCRT-III function is in fact inhibited in our system.

The uncontrolled expression of the dominant negative proteins from the viral genome resulted in protein levels sufficient to cause cytotoxicity. Viral protein expression was significantly reduced, since the infection was unable to proceed under these cytotoxic conditions (Fig. 1). To ensure that our lentivirus system controlled the expression of the dominant negative ESCRT-III subunits sufficiently to avoid generating conditions too toxic for an infection to progress, we examined the expression and localization of viral proteins. We harvested lysates from our HCMV-infected fibroblasts containing dominant negative constructs at 96 hpi and found no difference in the levels of the viral proteins pUL44, pp150, and pp28, regardless of the duration of induction (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, there was no difference in pp28 or gB localization after the induction of either CHMP6-GFP or CHMP4B-GFP (Fig. 3B), suggesting that viral proteins were able to traffic to what appears to be a properly formed cVAC in the absence of a functional ESCRT-III pathway. This important observation confirms that blocking the ESCRT pathway does not alter the trafficking of viral factors; however, it does not reveal whether a block is occurring for cytoplasmic envelopment, a process that occurs temporally after the proper formation of viral factors and their trafficking to the cVAC.

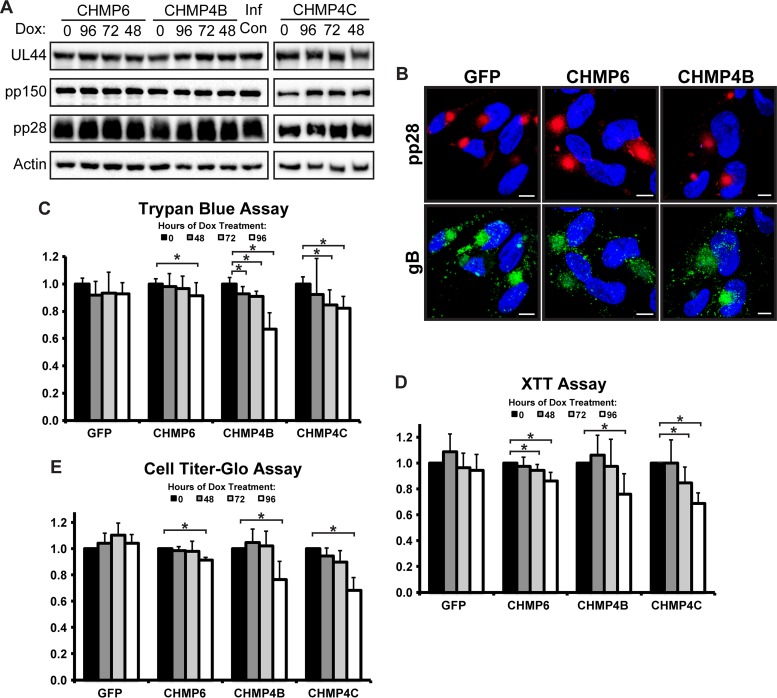

FIG 3.

HCMV viral protein expression and cVAC formation are unaffected by dominant negative ESCRT-III subunits. (A) Western blot analysis of viral proteins 96 hpi (MOI, 3) in fibroblasts expressing CHMP6-GFP, CHMP4B-GFP, or CHMP4C-GFP. Hours (above the blot) indicate the duration of Dox induction. (B) Immunofluorescence staining for pp28 (red) and gB (green) 96 hpi. Fibroblasts were treated with Dox for 48 h prior to fixation. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI. Bars, 10 μm. (C to E) Cell viability assays on fibroblasts expressing GFP, CHMP6-GFP, CHMP4B-GFP, or CHMP4C-GFP 96 hpi (MOI, 3) as measured by a trypan blue (C), XTT (D), or CellTiter-Glo (E) assay. For each cell type, viability is shown relative to no Dox treatment. Significant differences (P < 0.05) between samples are marked with asterisks. All viability assay results are from at least three independent experiments.

One final test of our system was to monitor the status of the cells when the ESCRT-III pathway was inhibited. Using three different cell viability assays based on three different parameters (membrane permeability, NADPH levels, and ATP levels), we found that blocking ESCRT-III often resulted in a slight but significant drop in cell viability after induction of the dominant negative subunits. This observation illustrates the importance of tightly controlling dominant negative ESCRT-III expression to maintain a level and duration sufficient to block pathway function without inducing cell toxicity.

Having established a system in which ESCRT-III function was inhibited without high levels of cell toxicity, we next investigated whether ESCRT-III was required for productive HCMV infection. Expression of the dominant negative constructs was induced for either 96 (doxycycline was added at the time of infection), 72, or 48 h. Regardless of the time of induction, the presence of the CHMP6 dominant negative protein had no significant effect on total (cell-associated plus extracellular) infectious virus titers (Fig. 4A), and therefore, CHMP6 does not appear to play a role in the HCMV replication cycle. During ILV formation, a major role of CHMP6 is to bind to ESCRT-II to initiate ESCRT-III oligomerization. While a role for ESCRT-II has not been investigated during HCMV infection, it is known that ESCRT-I is not required. Thus, it is possible that HCMV bypasses the need for both the upstream ESCRT complexes and CHMP6 by directly recruiting CHMP4 to initiate the ESCRT-III polymer, which, in turn, recruits VPS4. In a similar manner, HIV does not require the ESCRT-II complex or CHMP6 for budding, since CHMP4 is recruited in an alternative manner (17).

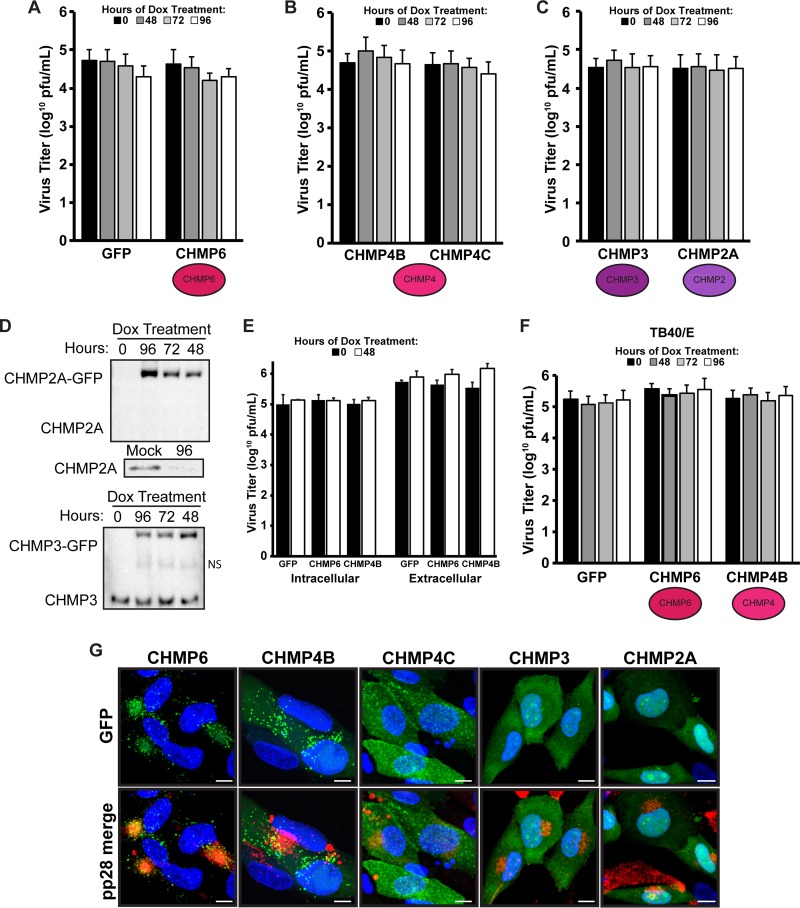

FIG 4.

ESCRT-III is not required for productive HCMV infection. (A to C) Virus titers at 96 hpi (MOI, 3) of fibroblasts expressing GFP or CHMP6-GFP (A), CHMP4B-GFP or CHMP4C-GFP (B), or CHMP3-GFP or CHMP2A-GFP (C) with HCMV strain AD169. (D) Western blot analysis of endogenous and GFP-tagged CHMP3 and CHMP2A at 96 hpi after Dox induction for 0, 48, 72, or 96 h. NS, nonspecific band detected by the CHMP3 antibody. (Inset) Mock-treated and 96-hpi lysates probed with the CHMP2A antibody. (E) Intracellular and extracellular virus titers (96 hpi) on fibroblasts selected for constructs expressing GFP, CHMP6-GFP, or CHMP4B-GFP, infected with HCMV AD169 in the presence or absence of Dox (48-h induction). (F) Virus titers at 96 hpi on fibroblasts with HCMV strain TB40/E. No significant differences were found between samples (P > 0.05). Titers are from at least three independent experiments. (G) Micrographs depicting the localization of CHMP-GFP proteins in relation to pp28 (red). Bars, 10 μm.

To investigate a role for CHMP4, we used dominant negative versions of two of the CHMP4 isoforms, CHMP4B and CHMP4C. Surprisingly, neither isoform affected viral titers (Fig. 4B). Thus, neither CHMP6 nor CHMP4 is required for producing infectious HCMV virions, in contrast to the findings with HSV-1 (Fig. 2E). Similarly, virus titers were not affected in the presence of a dominant negative CHMP3 or CHMP2A construct (Fig. 4C), although these two isoforms were not subjected to all the extensive tests measuring toxicity and the functional block as the CHMP6 and the CHMP4 isoforms. However, Western blot analysis confirmed that the dominant negative CHMP2A protein was in abundant excess over endogenous levels (Fig. 4D). In contrast, endogenous levels of CHMP3 were similar to CHMP3-GFP levels, indicating the possibility that CHMP3-GFP levels may not be sufficient to block complex function. Nonetheless, we could detect no reduction in virus titers under conditions where ESCRT-III function was shown to be inhibited.

The titer data presented above were for a combination of both cell-associated and extracellular virus. To show that there was no reduction in the release of extracellular virus, we next harvested cell-associated and extracellular virus separately. We found no difference in the release of infectious virions from uninduced cells and cells expressing GFP, CHMP6-GFP, or CHMP4B-GFP (Fig. 4E). Taken together, these observations are not consistent with the hypothesis that ESCRT-III is involved in envelopment. To show that these results were not specific for the laboratory strain AD169, we infected our GFP-, CHMP6-, and CHMP4B-selected fibroblasts with HCMV strain TB40/E. We found that induction of the dominant negative CHMP6 or CHMP4B subunits after infection with TB40/E did not affect the production of infectious virions (Fig. 4F), confirming our observation that HCMV does not require ESCRT-III for a productive infection. In support of this observation, we found that of the ESCRT-III subunits investigated, only CHMP6 was recruited to the assembly compartment (Fig. 4G). Thus, HCMV does not recruit ESCRT-III to mediate the envelopment step.

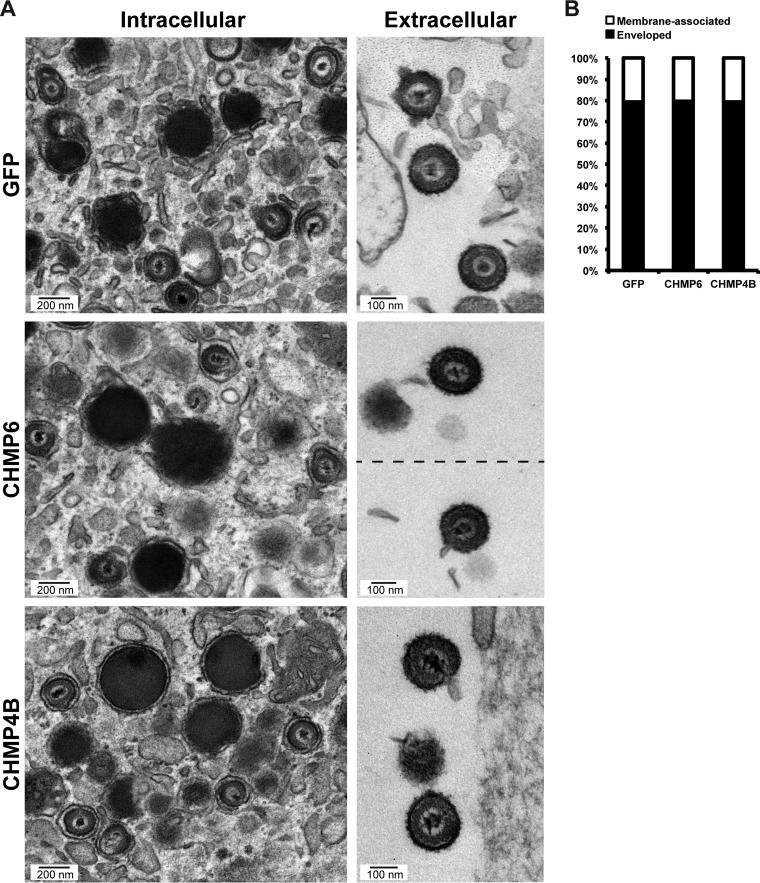

While these observations suggest that ESCRT-III is not involved in envelopment, we next used electron microscopy (EM) to examine cytoplasmic and extracellular virions in the presence of our dominant negative ESCRT-III subunits. Expression of dominant negative CHMP6 or CHMP4B proteins did not affect envelopment, as evidenced by the fact that properly enveloped virions in the cytoplasm and extracellular space were prevalent (Fig. 5A). Quantitative analysis of the EM images revealed no difference among the samples in the percentages of membrane-associated capsids undergoing envelopment and fully enveloped capsids (Fig. 5B). This is consistent with the absence of any significant reduction in virus titers. Since blocking a single subunit has the net effect of blocking the entire ESCRT-III pathway, our data strongly support the notion that ESCRT-III is not required for the production of infectious virions and does not mediate envelopment. However, we cannot completely rule out a contribution from isoforms that were untested (CHMP4A, CHMP2B) or undertested (CHMP3, CHMP2A).

FIG 5.

Dominant negative ESCRT-III does not inhibit HCMV secondary envelopment. (A) Electron micrographs of enveloped intracellular and extracellular virions in fibroblasts expressing GFP, CHMP6-GFP, or CHMP4B-GFP at 96 h after infection with AD169 (MOI, 3). Fibroblasts were treated with Dox for 48 h prior to fixation. (B) Graph showing percentages of membrane-associated capsids that have not completed envelopment compared to percentages of fully enveloped capsids. Total numbers of capsids were 182 (GFP), 190 (CHMP6), and 181 (CHMP4B).

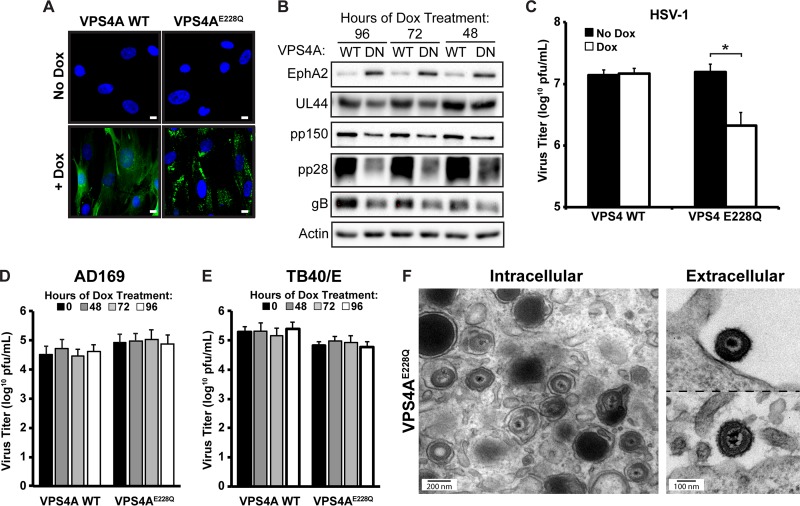

VPS4 is not required for the production of infectious HCMV virions.

Our results indicate that ESCRT-III is not required for HCMV infection. However, VPS4, which is normally recruited by ESCRT-III, has been shown to localize to the viral cytoplasmic assembly compartment (6) and may play a role in HCMV infection, although conflicting reports about a role for VPS4 exist (3, 4). Since there are conflicting reports about the role of VPS4 during HCMV infection, we first wanted to confirm the VPS4 phenotype utilizing our inducible system in which we can block function without inducing toxicity to cells. Accordingly, we generated cells expressing GFP fusions of wild-type (WT) VPS4A or VPS4AE228Q, which blocks ATP hydrolysis, acts in a dominant negative manner, and inhibits HIV-1 budding (2). Expression of both constructs was induced in the presence of doxycycline (Fig. 6A). We next showed that we were able to successfully block the ESCRT pathway, as shown by the accumulation of a plasma membrane protein, EphA2, which is endocytosed and targeted for degradation during HCMV infection (18). EphA2 levels were significantly increased after induction of the dominant negative form, but not the wild-type form, of VPS4A (Fig. 6B). As a confirmation of the block in VPS4 function, infection of the VPS4AE228Q fibroblasts with HSV-1 resulted in a 1-log reduction in the production of infectious HSV-1 virions (Fig. 6C), a finding similar to what has been reported previously (15). We next measured cell-associated and extracellular infectious HCMV virions and, contrary to our hypothesis, found that blocking VPS4 function did not reduce HCMV titers after infection with either the AD169 or the TB40/E strain (Fig. 6D and E). This was particularly surprising because after induction of the dominant negative VPS4A construct for any amount of time, we noticed reductions in steady-state levels of pUL44, pp150, pp28, and gB (Fig. 6B). This suggests that prolonged exposure to the dominant negative VPS4A construct was beginning to adversely affect cell fitness, which was confirmed by observed decreases in cell viability in two of our three assays (data not shown). Importantly, despite the reductions in viral steady-state protein levels and cell viability, we observed no decrease in infectious virus titers. If anything, there was a slight increase in titers with the AD169 strain, as was originally reported using siRNA against VPS4 (4), although our data did not have sufficient statistical power to confirm a significant increase in virus titers. EM analysis confirmed the presence of both intracellular and extracellular HCMV virions (Fig. 6F). Hence, we conclude that VPS4A is not required for the cytoplasmic envelopment of HCMV virions.

FIG 6.

VPS4A is not required for HCMV envelopment. (A) Fibroblasts were transduced with inducible WT GFP-VPS4A or VPS4AE228Q and were imaged 24 h post-Dox treatment. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Bars, 10 μm. (B) Western blot analysis of cellular protein EphA2 and viral proteins pUL44, pp150, and pp28 at 96 hpi after AD169 infection (MOI, 3) of fibroblasts expressing WT VPS4A (WT) or dominant negative VPS4AE228Q (DN). (C) Virus titers on fibroblasts expressing WT VPS4A or VPS4AE228Q 24 h after HSV-1 infection. Dox was added to cells 24 h prior to infection. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (P < 0.05) between samples. (D and E) HCMV AD169 (D) and TB40/E (E) titers at 96 h after infection (MOI, 3) of fibroblasts expressing WT VPS4A or VPS4AE228Q. No significant differences were found between samples (P > 0.05). Viral titers are from three independent experiments. (F) Electron micrographs of enveloped intracellular and extracellular virions from VPS4AE228Q cells 96 h after infection with HCMV AD169 (MOI, 3). Dox was added to cells for 48 h prior to fixation.

ESCRT-III has a nonenvelopment role in the spread of HCMV.

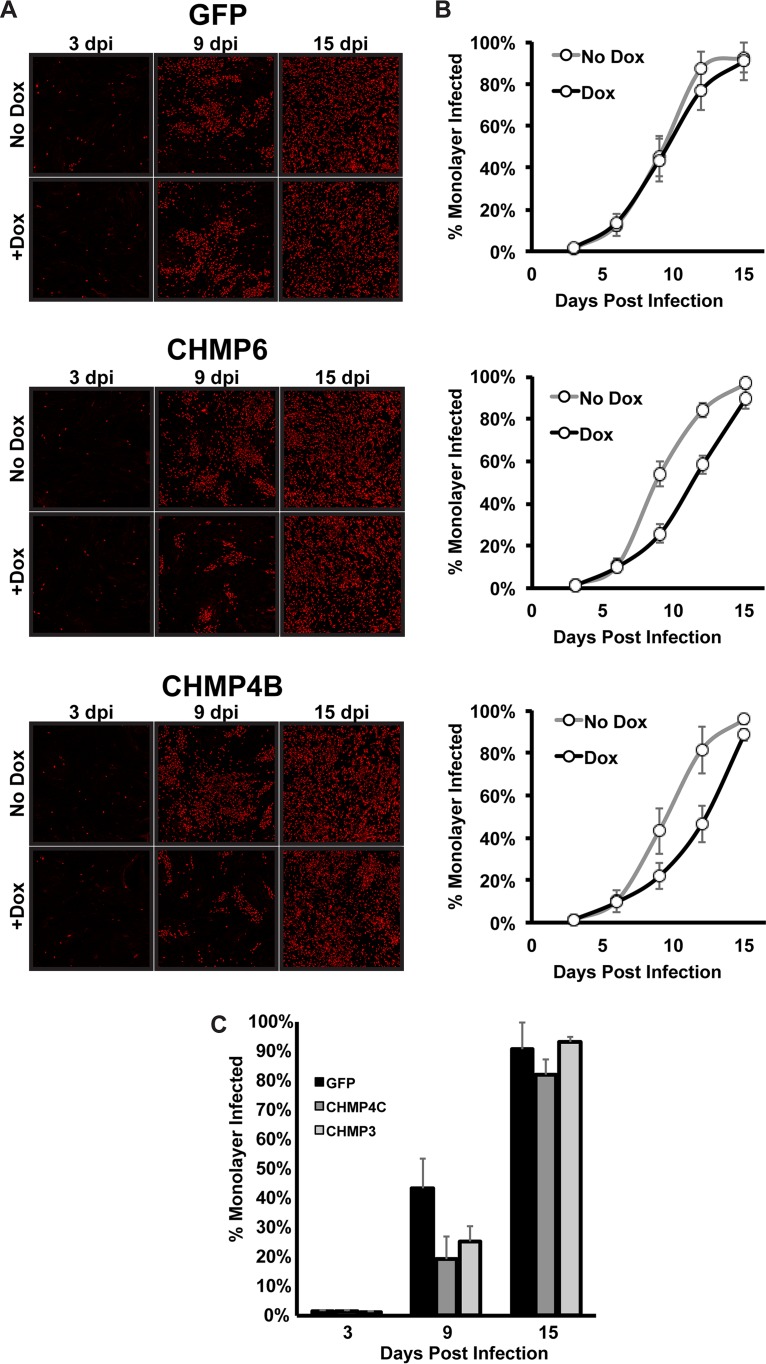

While our results are consistent with VPS4 not being required for the production of infectious virions, and hence capsid envelopment, we were interested in the conflicting reports on a role for VPS4 during infection (3, 4). One explanation was that the transfection of the dominant negative constructs led to cell toxicity and the inability to support an infection. This is consistent with our results showing that cells are sensitive to both the level and the duration of dominant negative expression. A second possible explanation could be the differences in the multiplicity of infection (MOI). In our study and the siRNA knockdown study reporting no effect for VPS4 (4), high MOIs were used. In contrast, a phenotype for VPS4 was found using a low-MOI infection monitored by antigen spread (3). Therefore, we used a low-MOI infection and asked whether blocking ESCRT-III would affect the spread of HCMV, similarly to what was reported for VPS4. To avoid toxicity concerns with expressing our dominant negative ESCRT-III subunit in the entire population for an extended period of time, we modified our system slightly and placed the Tet activator protein in the HCMV genome. Thus, although the entire population of cells contained the dominant negative ESCRT-III construct and was exposed to doxycycline, only the infected cells would contain the Tet activator and would be able to induce expression of the dominant negative construct. After a low-MOI infection, we fixed cells at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 days postinfection (dpi) and stained for expression of the major immediate early proteins. We then calculated the percentage of the monolayer that was infected. In cells expressing GFP only, the infection spread throughout the monolayer in both the presence and the absence of doxycycline (Fig. 7A and B). In contrast, in the presence of CHMP6-GFP or CHMP4B-GFP, there was a delay in spread at both 9 and 12 days postinfection. For both constructs, however, this delay was overcome, and infection was indistinguishable from that for the uninduced cells, at 15 dpi. Similar results were observed for both CHMP4C and CHMP3 (Fig. 7C). Thus, ESCRT-III improves the efficiency of spread but does not appear to be essential for HCMV replication.

FIG 7.

Dominant negative ESCRT-III subunits slow HCMV spread during low-MOI infection. Shown are low-MOI (0.05) infections of fibroblasts expressing inducible GFP, CHMP6-GFP, or CHMP4B-GFP with AD169 Tet activator HCMV. (A) Immunofluorescence staining for immediate early protein (red) 3, 9, and 15 dpi. Dox was added to cells at the beginning of infection, and fresh Dox was added every 3 days thereafter. (B) The percentage of the monolayer infected was calculated by comparing DAPI and immediate early protein staining fluorescence within the monolayer from three independent experiments. (C) Percentage of the monolayer infected in fibroblasts expressing CHMP4C-GFP and CHMP3-GFP during low-MOI infection with Dox treatment as described for panel A.

DISCUSSION

In an attempt to elucidate the mechanism of cytoplasmic envelopment of HCMV, we set out to define the contribution of the previously uninvestigated ESCRT-III core subunits. While it has been shown that some ESCRT components (ALIX and Tsg101) are not required for HCMV infection, the role of the ESCRT AAA ATPase VPS4 is less clear, since there are conflicting reports on whether HCMV requires VPS4 for a productive infection (3, 4). We hypothesized that HCMV utilizes the late ESCRTs, ESCRT-III and Vps4, to mediate cytoplasmic envelopment and bypasses the upstream ESCRT complexes by directly recruiting these ESCRT complexes to sites of envelopment. Previous reports have defined a role for the viral protein UL71 in cytoplasmic envelopment, since both the UL71 knockout virus and viruses with UL71 mutants trap envelopment at the budding stage (7, 8). Thus, UL71 is a prime candidate for the viral factor responsible for recruiting the core ESCRT-III subunits and VPS4 to mediate the final scission event during envelopment.

To our surprise, we found no evidence that HCMV requires ESCRT-III for the production of infectious virions. We found numerous virions, both intracellular and extracellular, with a viral envelope, disproving our hypothesis. This observation was not strain dependent. One concern with the negative result is that we may not be sufficiently blocking ESCRT function. We used two separate assays to show that ESCRT function was inhibited in our system. In one assay, degradation of an internalized protein was inhibited upon doxycycline induction, and in the second assay, the production of HSV-1 virions, which requires ESCRT-III, was reduced upon induction of our dominant negative constructs. Thus, despite a successful block in ESCRT-III function, we observed no defect in the production of HCMV. Therefore, while there may be a supporting role for ESCRT-III that we did not detect in our system, our results clearly show that the ESCRT-III complex is not the sole factor mediating the scission event of HCMV envelopment.

Based on these results, we next hypothesized that UL71 was recruiting VPS4 directly to mediate envelopment. To investigate this hypothesis, we first wanted to confirm the VPS4 phenotype using our system. We were unable to detect any reduction in infectious virion production in the presence of a dominant negative VPS4 protein despite showing a block in the pathway by use of our two assays to monitor ESCRT function. Titers remained constant even under conditions where we began to detect cell toxicity and reductions in virus protein steady-state levels. Thus, our results are in agreement with the original publication reporting that VPS4 was not required for HCMV infection (4). This result is somewhat surprising, since both published results and our observations indicate that VPS4 is recruited to the assembly compartment region (3, 6, 19). We also observed that CHMP6 is recruited to the cVAC region but found no evidence of cVAC localization for the other ESCRT-III subunits. Why HCMV would recruit VPS4A and CHMP6, but not other ESCRT-III factors, to the cVAC remains an open question.

One observation that we made consistently throughout our study was the sensitivity of cells to expression of the dominant negative ESCRT-III and VPS4 constructs. We noticed that cells were sensitive to both the level of dominant negative protein expressed and the duration of this overexpression. Similar observations were noted in the paper originally describing the dominant negative ESCRT-III constructs, in which high expression levels of the dominant negative ESCRT-III subunits affected the expression of the HIV Gag protein (14). We were also able to find conditions where infectious virion titers were reduced when the dominant negative constructs were expressed in large amounts; however, under these conditions, this is likely a result of general cell toxicity rather than evidence of a direct role for the ESCRTs. In support of this, steady-state levels of viral proteins were severely reduced, indicating that the ability of the virus to robustly initiate gene expression was hampered when dominant negative constructs were expressed at these higher levels. This may be a contributing reason for the discrepancy in previous reports investigating a role for VPS4.

Taken together, all results indicate an envelopment mechanism independent of ESCRT-III and VPS4. Thus, the mechanistic details of HCMV envelopment remain an open area of investigation, including the elucidation of the factors involved. As mentioned previously, according to published results, UL71 has a clear role in this process (7, 8). However, future studies are needed to elucidate the other factors, whether of viral or host origin, that work in conjunction with UL71. Alternatively, UL71 alone may be sufficient to promote envelopment. UL71, which shares some structural elements with ESCRT-III subunits, may promote membrane scission in a manner similar to that of the ESCRT-III complex. Future studies, including a structural analysis of UL71, are required to address these open questions.

While we were unable to find a role for ESCRT-III in HCMV envelopment, we did find that efficient spread of HCMV through the monolayer was reduced in the absence of functional ESCRT-III subunits. Although necessary for efficient spread, they are not required for spread, as the infection eventually caught up by 15 dpi. One hypothesis consistent with this observation is that the ESCRTs are involved in producing exosomes that transmit a signal to neighboring cells to prepare them for the incoming infection. Spread is delayed in the absence of this signal. Viral modulation of extracellular vesicles released from infected cells has been described for other herpesviruses (20–22). Exosomes released from cells infected with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) contain viral factors that activate growth-signaling pathways in uninfected cells (23). It is thought that this cell-to-cell communication contributes to the signaling activity within tumor microenvironments. Similarly, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) microRNAs (miRNAs) are packaged into exosomes and target cellular pathways that alter cell migration (24). HCMV-infected cells undergo significant metabolic changes to support infection, and it seems possible that initiating these signaling pathways prior to infection may enhance virus spread. Alternatively, the ESCRTs may be involved in degrading an inhibitory signal, which slows infection in the absence of a functional degradation pathway. Further experiments are required to elucidate the contribution of the ESCRTs to HCMV spread.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Normal human dermal fibroblasts (HFFs) (catalog no. 106-05n; Cell Applications Inc.), normal human lung fibroblasts, MRC-5 cells (ATCC CCL-171), and HEK-293TN (provided by David Spector) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Corning) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM GlutaMAX (Gibco), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 g/ml streptomycin (Corning). Cells were maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2.

BAC mutagenesis.

Recombinant viruses were generated using bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) mutagenesis in Escherichia coli strain SW105 and galK selection as described previously (25). Inducible ESCRT constructs were generated with pTRE3G-Bi and pEF1a-Tet3G (Clontech). ESCRT-III subunits C-terminally tagged with GFP in pEGFPN2 (Clontech) were inserted into pTRE3G-Bi using restriction enzyme digestion with BglII and NotI. Recombinant viruses were made by PCR amplification of the Tet-inducible promoter and GFP-tagged subunits and recombination into the EF1a-Tet3G AD169 BAC, which has been described previously (26). The EF1a-Tet3G construct was inserted near the TRS1 region of the genome. AD169 encoding EF1-Tet3G was used as the parental control virus for all recombinant viruses expressing dominant negative ESCRT-III subunits. The pTRE3G-Bi promoter construct was inserted near the US34a region. The following primers were used: forward, 5′-AGGGTGGCGAGGTGTGAGGATGAAACATATGCAGATACGCAGTGTTGTTA AAGTGCCACCTGACGTCG; reverse, 5′-GACTTTCATACTGAAGTACCGTTGTACGCATTACACGGGTTTCGTTCGGA GTGAGCGAGGAAGCTCGG. BAC insertion sites were PCR amplified from purified BAC DNA and were verified by Sanger sequencing (Genewiz).

HCMV infections and virus titrations.

TB40/E, AD169, and derivatives listed above were generated from BAC stocks. To generate virus stocks, purified BAC DNA was electroporated into MRC-5 cells according to previously published protocols (27). Infected cells were used to infect MRC-5 cells in roller bottles (Greiner) to produce larger stocks of virus for experimental infections. Virions produced in roller bottles were concentrated by ultracentrifugation on a 20% sorbitol cushion at 20,000 rpm for 1 h at 20°C in a Beckman SW32 rotor.

HCMV infections were carried out at an MOI of 0.05 for multistep growth curves and at an MOI of 3 for single-step growth curves. Cell counts were determined using a TC20 automated cell counter (Bio-Rad). Virus-infected cells were incubated for 3 h at 37°C before the medium was replaced with fresh medium. For inducible ESCRT infections, 100 ng/ml doxycycline (Enzo Life Sciences) was added to the medium at various time points. Virus was harvested at 96 h postinfection for each experiment by scraping the cells into the medium, sonicating 10 times with 1-s pulses, vortexing for 15 s, and centrifuging at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. Supernatants were collected and were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen before storage at −80°C.

HCMV stocks and samples for growth curves were titrated by serial dilutions on MRC-5 cells and were quantified by the immunological detection of immediate early proteins as described previously (28). A rabbit polyclonal antibody that detects exons 2 and 3 of the major HCMV immediate early proteins was a kind gift from Jim Alwine (29). Images of stained monolayers were acquired on a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope, and fluorescent nuclei were quantified using NIS Elements software.

HSV infections.

Transduced and selected HFFs (as described in the next section) were infected with the KOS strain of HSV-1 at an MOI of 5 for 1 h at 37°C. This MOI was calculated using the viral titer that was determined by a plaque assay on Vero cells. After 1 h of infection, HFFs were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and were then incubated with a regular infection medium with or without doxycycline at 37°C. At 24 h postinfection, when a cytopathic effect (CPE) was apparent, HFFs and medium were harvested together and were put through 3 freeze-thaw cycles prior to titration. The viral titer was determined for each sample by a plaque assay on Vero cells. Graphed data represent the results of 3 independent experiments.

Lentivirus production and cell selection.

Lentivirus was made using the 3rd-generation packaging system: pMDLg/pRRE and pRSV Rev were a gift from Didier Trono (plasmids 12251 and 12253; Addgene), and pCMV-VSV-G was a gift from Bob Weinberg (plasmid 8454; Addgene). The pCDH vector, WT VPS4A, and VPS4AE228Q were gifts from J. Lammerding. To make inducible ESCRT constructs in the pCDH vector, we replaced the CMV promoter of pCDH with a Tet-inducible promoter to make inducible pCDH (pCDHi). The pCDH CMV promoter was removed by restriction enzyme digestion with SpeI and NotI. The Tet-inducible promoter was removed from pTRE3G-Bi by digestion with XbaI and NotI and was ligated into pCDH with compatible overhangs between SpeI and XbaI. CHMP-GFP sequences were inserted into pCDHi by PCR amplification from pEGFPN2 and restriction enzyme digestion using BamHI and NotI with the following primers: CHMP6 forward (5′-GCATGGATCCATGGGTAACCTGTTCGGCCG), CHMP4B forward (5′-GCATGGATCCATGTCGGTGTTCGGGAAGCTG), CHMP4C forward (5′-GCATGGATCCATGAGCAAGTTGGGCAAGTTC), CHMP3 forward (5′-GCATGGATCCATGGGGCTGTTTGGAAAGAC), CHMP2A forward (5′-GCATGGATCCATGGACCTATTGTTCGGGCG), and the common GFP reverse primer (5′-GCATGCGGCCGCTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCA).

GFP-VPS4A WT and E228Q were inserted (BamHI/NotI) using the following primers: forward, 5′-GCATGGATCCCCGCCACCATGGTGAGCAAG; reverse, 5′-GCATGCGGCCGCACTCTCTTGCCCAAAGTCC.

Lentivirus was produced in 293TN cells using the X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Roche) and was harvested according to the manufacturer's protocol. For lentiviral delivery, subconfluent HFFs were transduced with lentivirus encoding Tet-inducible constructs in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich). Transduced cells were then passaged under 2 μg/ml puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) selection. Following selection, cells were either used for low-MOI infection with recombinant EF1a-Tet3G HCMV or seeded at subconfluence for a second lentiviral transduction with the EF1a-Tet3G lentivirus. Following the second lentivirus transduction, cells were expanded and were used for high-MOI HCMV and HSV infections.

Western blotting.

Total-cell lysates were prepared from HCMV-infected cells at an MOI of 3 at 96 h postinfection by harvesting lysates in 1× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM aprotinin, 0.2 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml leupeptin. Laemmli buffer was added directly to cell monolayers, which were then incubated for 10 min before being collected and stored at −80°C. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting on a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane blocked with 5% milk or 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-buffered saline (0.1% Tween). We used the following antibodies: CMV pp28 (5C3; Virusys), CMV pp52 (CH13; Santa Cruz), CMV pp150 (a gift from David Spector), CMV gB (Virusys), actin (EMD Millipore), EphA2 (Cell Signaling), CHMP6 (Proteintech), CHMP4B (Proteintech), CHMP4C (Origene), CHMP2A (Proteintech), CHMP3 (Abcam), and GFP (a gift from John Wills). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for Western blotting detection were purchased from Santa Cruz (goat anti-rabbit) and GE Healthcare (sheep anti-mouse). Antibody dilutions were in accordance with manufacturers' instructions. The SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific) was used for secondary-antibody detection.

Cell viability assays.

Cells used for viability assays were infected at an MOI of 3 and were analyzed 96 hpi. Doxycycline (100 ng/ml) was added to samples at various time points. For trypan blue experiments, cells were washed with PBS, treated with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Life Technologies), and resuspended with medium. Cells were mixed in a 1:1 ratio with 0.4% trypan blue dye (Bio-Rad), and the percentage of live cells was determined using the TC20 automated cell counter (Bio-Rad). For the 2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide salt (XTT) assay, the medium was removed from all wells and was replaced with fresh medium at 96 hpi. XTT and activating reagents (Biotium) were added to each well according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C, and absorbance was measured using a Synergy H1 hybrid reader (BioTek). For the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega), the medium was removed from all wells and replaced with fresh medium at 96 hpi. Reagents were added to each well according to manufacturers' instructions. Luminescence was measured using the Synergy H1 hybrid reader.

EGF degradation assay.

Fibroblasts were grown on coverslips in the presence or absence of doxycycline. Cells were cooled on ice for 10 min and were washed twice with cold epidermal growth factor (EGF) binding medium: DMEM, 0.2% BSA, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). Cells were incubated on ice for 30 min in EGF binding medium containing 100 ng/ml EGF conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 (Life Technologies). Cells were washed 3 times with EGF binding medium and were returned to 37°C in EGF binding medium. Cells were fixed at 30 and 180 min after incubation at 37°C, and coverslips were mounted using DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech). Images were taken on a C2+ confocal microscope system (Nikon).

Immunofluorescence microscopy and imaging.

Coverslips containing either uninfected or HCMV-infected cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were blocked in PBS containing 10% human serum, 0.5% Tween 20, and 5% glycine. Triton X-100 (0.1%) was added for permeabilization. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer. The primary antibodies to viral proteins pp28 (Virusys) and gB (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- and rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Alexa Fluor 488- and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were also used. Coverslips were mounted with ProLong Diamond antifade mountant with DAPI (Thermo Scientific). Images were taken on a C2+ confocal microscope system (Nikon). Images were processed using NIS Elements software. Images shown in Fig. 2 through 6 are volume renderings of z-stacks.

Electron microscopy.

Cells were seeded on 60-mm Permanox tissue culture dishes (Nalge Nunc International). Cells were infected at an MOI of 3 for 96 h, and 100 ng/ml doxycycline was added 48 hpi. At 96 hpi, cells were washed with PBS and were fixed at 4°C in fixation buffer (0.5% [vol/vol] glutaraldehyde, 0.04% [wt/vol] paraformaldehyde, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate). Cells were processed by the Microscopy Imaging Facility (Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine). Briefly, the fixed samples were washed three times with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, followed by postfixation in 1% osmium–1.5% potassium ferrocyanide overnight at 4°C. Samples were then washed 3 times in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, dehydrated with ethanol, and embedded in Epon 812 for staining and sectioning. Images were acquired using a JEOL JEM-1400 Digital Capture transmission electron microscope. For the quantification of EM micrographs, tegumented capsids in contact with the membrane were categorized as to whether envelopment was completed (enveloped) or in process (membrane associated).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Brianne Roper for assistance in generating reagents. We thank Han Chen and the Penn State Hershey imaging core for the preparation of EM samples. We thank John Wills for helpful discussions, suggestions on preparing the manuscript, and assistance with the HSV-1 studies in his lab.

J.C. was supported by John Wills' NIH grant R01AI071286. The work and authors N.J.B and N.T.S. were supported by NIH grant R01AI130156 to N.J.B., by NIH training grant T32CA060395 (N.T.S.), and under a grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco CURE Funds. The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rossman JS, Jing X, Leser GP, Lamb RA. 2010. Influenza virus M2 protein mediates ESCRT-independent membrane scission. Cell 142:902–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrus JE, von Schwedler UK, Pornillos OW, Morham SG, Zavitz KH, Wang HE, Wettstein DA, Stray KM, Côté M, Rich RL, Myszka DG, Sundquist WI. 2001. Tsg101 and the vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell 107:55–65. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tandon R, AuCoin DP, Mocarski ES. 2009. Human cytomegalovirus exploits ESCRT machinery in the process of virion maturation. J Virol 83:10797–10807. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01093-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraile-Ramos A, Pelchen-Matthews A, Risco C, Rejas MT, Emery VC, Hassan-Walker AF, Esteban M, Marsh M. 2007. The ESCRT machinery is not required for human cytomegalovirus envelopment. Cell Microbiol 9:2955–2967. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajorek M, Morita E, Skalicky JJ, Morham SG, Babst M, Sundquist WI. 2009. Biochemical analyses of human IST1 and its function in cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell 20:1360–1373. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das S, Pellett PE. 2011. Spatial relationships between markers for secretory and endosomal machinery in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells versus those in uninfected cells. J Virol 85:5864–5879. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00155-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schauflinger M, Fischer D, Schreiber A, Chevillotte M, Walther P, Mertens T, von Einem J. 2011. The tegument protein UL71 of human cytomegalovirus is involved in late envelopment and affects multivesicular bodies. J Virol 85:3821–3832. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01540-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietz AN, Villinger C, Becker S, Frick M, von Einem J. 2018. A tyrosine-based trafficking motif of the tegument protein pUL71 is crucial for human cytomegalovirus secondary envelopment. J Virol 92:e00907-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00907-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das S, Ortiz DA, Gurczynski SJ, Khan F, Pellett PE. 2014. Identification of human cytomegalovirus genes important for biogenesis of the cytoplasmic virion assembly complex. J Virol 88:9086–9099. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01141-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahlqvist J, Mocarski E. 2011. Cytomegalovirus UL103 controls virion and dense body egress. J Virol 85:5125–5135. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01682-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albecka A, Owen DJ, Ivanova L, Brun J, Liman R, Davies L, Ahmed MF, Colaco S, Hollinshead M, Graham SC, Crump CM. 2017. Dual function of the pUL7-pUL51 tegument protein complex in herpes simplex virus 1 infection. J Virol 91:e02196-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02196-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klupp BG, Granzow H, Klopfleisch R, Fuchs W, Kopp M, Lenk M, Mettenleiter TC. 2005. Functional analysis of the pseudorabies virus UL51 protein. J Virol 79:3831–3840. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3831-3840.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oda S, Arii J, Koyanagi N, Kato A, Kawaguchi Y. 2016. The interaction between herpes simplex virus 1 tegument proteins UL51 and UL14 and its role in virion morphogenesis. J Virol 90:8754–8767. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01258-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Schwedler UK, Stuchell M, Müller B, Ward DM, Chung HY, Morita E, Wang HE, Davis T, He GP, Cimbora DM, Scott A, Kräusslich HG, Kaplan J, Morham SG, Sundquist WI. 2003. The protein network of HIV budding. Cell 114:701–713. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00714-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pawliczek T, Crump CM. 2009. Herpes simplex virus type 1 production requires a functional ESCRT-III complex but is independent of TSG101 and ALIX expression. J Virol 83:11254–11264. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00574-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crump CM, Yates C, Minson T. 2007. Herpes simplex virus type 1 cytoplasmic envelopment requires functional Vps4. J Virol 81:7380–7387. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00222-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langelier C, von Schwedler UK, Fisher RD, De Domenico I, White PL, Hill CP, Kaplan J, Ward D, Sundquist WI. 2006. Human ESCRT-II complex and its role in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 release. J Virol 80:9465–9480. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01049-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fielding CA, Weekes MP, Nobre LV, Ruckova E, Wilkie GS, Paulo JA, Chang C, Suárez NM, Davies JA, Antrobus R, Stanton RJ, Aicheler RJ, Nichols H, Vojtesek B, Trowsdale J, Davison AJ, Gygi SP, Tomasec P, Lehner PJ, Wilkinson GW. 2017. Control of immune ligands by members of a cytomegalovirus gene expansion suppresses natural killer cell activation. Elife 6:e22206. doi: 10.7554/eLife.22206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dell'Oste V, Gatti D, Gugliesi F, De Andrea M, Bawadekar M, Lo Cigno I, Biolatti M, Vallino M, Marschall M, Gariglio M, Landolfo S. 2014. Innate nuclear sensor IFI16 translocates into the cytoplasm during the early stage of in vitro human cytomegalovirus infection and is entrapped in the egressing virions during the late stage. J Virol 88:6970–6982. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00384-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLauchlan J, Addison C, Craigie MC, Rixon FJ. 1992. Noninfectious L-particles supply functions which can facilitate infection by HSV-1. Virology 190:682–688. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90906-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meckes DG, Gunawardena HP, Dekroon RM, Heaton PR, Edwards RH, Ozgur S, Griffith JD, Damania B, Raab-Traub N. 2013. Modulation of B-cell exosome proteins by gamma herpesvirus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E2925–E2933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303906110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalamvoki M, Du T, Roizman B. 2014. Cells infected with herpes simplex virus 1 export to uninfected cells exosomes containing STING, viral mRNAs, and microRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E4991–E4996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419338111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meckes DG, Shair KH, Marquitz AR, Kung CP, Edwards RH, Raab-Traub N. 2010. Human tumor virus utilizes exosomes for intercellular communication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:20370–20375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014194107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chugh PE, Sin SH, Ozgur S, Henry DH, Menezes P, Griffith J, Eron JJ, Damania B, Dittmer DP. 2013. Systemically circulating viral and tumor-derived microRNAs in KSHV-associated malignancies. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003484. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warming S, Costantino N, Court DL, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. 2005. Simple and highly efficient BAC recombineering using galK selection. Nucleic Acids Res 33:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruz L, Streck NT, Ferguson K, Desai T, Desai DH, Amin SG, Buchkovich NJ. 2017. Potent inhibition of human cytomegalovirus by modulation of cellular SNARE syntaxin 5. J Virol 91:e01637-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01637-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spector DJ, Yetming K. 2010. UL84-independent replication of human cytomegalovirus strain TB40/E. Virology 407:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Britt WJ. 2010. Human cytomegalovirus: propagation, quantification, and storage. Curr Protoc Microbiol Chapter 14:Unit 14E.3. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc14e03s18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harel NY, Alwine JC. 1998. Phosphorylation of the human cytomegalovirus 86-kilodalton immediate-early protein IE2. J Virol 72:5481–5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]