Abstract

Aniridia-associated glaucoma is often refractory to medical treatment. Glaucoma drainage device surgery is often considered after failed angle surgery. However, the potential complications of tube surgery in young children are not negligible. The failure rate of conventional trabeculectomy may be high and can require close and multiple postoperative follow-up visits. Here, we describe a child with aniridia who achieved good short-term results with deep sclerectomy. A 14-month-old girl was referred to our unit following bilateral trabeculotomies for aniridia-associated glaucoma and persistent uncontrolled intraocular pressure (IOP) in both eyes. She underwent sequential bilateral deep sclerectomies with microperforations. The patient achieved normalized IOP in both eyes after 6-month follow-up without any complications. Deep sclerectomy, with microperforations, may be a reasonable surgical procedure to perform in children with aniridia with failed angle surgery before contemplating tube shunt surgery.

Keywords: Aniridia, deep sclerectomy, glaucoma

Introduction

Aniridia is a rare bilateral ocular disorder affecting the iris and other ocular tissues.[1] Due to changes in the structure of the angle such as the anterior rotation of the rudimentary iris, glaucoma in congenital aniridia is usually developed during the adolescent or early adolescent years. Aniridia-associated glaucoma is difficult to manage [2] and many methods have been described to control the disease including medical treatment,[3] trabeculotomy,[4] goniotomy,[4] trabeculectomy,[4,5] or glaucoma drainage devices (GDDs).[6]

To the best of our knowledge, few reports have focused on deep sclerectomy in eyes with congenital glaucoma associated with aniridia.[7] Here, we describe a child with aniridia who underwent deep sclerectomy with microperforations after failed trabeculotomies in both eyes.

Case Report

A 14-month-old girl was referred to tertiary care unit for a history of “congenital glaucoma” for an opinion regarding surgical management. She had a history of prematurity, born at 6 months of gestation and stayed in the incubator for 6-months postpartum. She received treatment for a resolved chronic lung disease and following up with cardiology for small patent ductus arteriosus and small patent foramen ovale. She was status post bilateral glaucoma angle surgery (trabeculotomy) at the age of 4 months which was done elsewhere and was on antiglaucoma eye drops of timolol maleate 0.5% twice daily, dorzolamide 2% twice daily, and apraclonidine 0.5% twice daily in both eyes and latanoprost 0.005% once at bed time in the right eye only. On examination, she had mild corneal haze more in the left eye, deep anterior chambers (AC) in both eyes, aniridia (with rudimentary iris stump) in both eyes, and clear lenses in both eyes. Fundus examination showed flat retinae with cup-to-disc ratios of 0.6 in the right eye and 0.7 in the left eye with average-sized discs for her age. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was taken in both eyes using pneumotonometer with difficulty as the child was crying but measured and was 37 mmHg in the right eye and 38 mmHg in the left eye. The impression at this stage was congenital glaucoma associated with aniridia (secondary glaucoma) in both eyes and the patient was scheduled for examination under anesthesia (EUA) for a more detailed assessment with possible glaucoma surgery to either eye. This plan was explained and discussed with the family.

During the EUA, the examination results were similar as before. The IOP was taken by pneumotonometer and was 26 mmHg in the right eye and 32 mmHg in the left eye and it was also taken by tonopen and was 35 mmHg in the right eye and 45 mmHg in the left eye before intubation. The horizontal corneal diameter was 13 mm in both eyes. Central corneal thickness was 453 μ in the right eye and 472 μ in the left eye. Ultrasound A - scan axial length was 22.6 mm in the right eye and 21.9 mm in the left eye.

Given the worse corneal haze in the left eye and higher IOP, a decision was made to undergo glaucoma surgery in the left eye. A decision to perform deep sclerectomy was made as this had been successfully performed by other consultants in our department with good results. It was anticipated that, due to angle anomalies in aniridia,[3] penetration of the trabeculo-Descemet's window (TDW) might be needed to achieve adequate filtration.

The left eye was prepped and draped in the usual sterile ophthalmic manner. A wire lid speculum was applied to open the eye. Before starting the procedure, the conjunctiva was noted to be scarred superiorly between 10 o'clock and 12 o'clock. Therefore, a superonasal site was chosen for surgery. A 6/0 vicryl corneal traction suture placed, conjunctival peritomy and posterior dissection with Wescotts scissors were done. Mitomycin C (0.4 mg/ml) sponges were placed for 3 min under the conjunctiva then removed followed by copious irrigation of the eye to remove excess Mitomycin C. A 5 × 5 mm superficial scleral flap and 4 × 4 mm deeper scleral flap were fashioned. Schlemm's canal was prodded with a blunt spatula but only minimal flow was noticed. Therefore, three perforations were made with 30-gauge needle in the TDW. The deeper flap was removed, and the superficial scleral flap was sutured fairly tightly with two 10/0 nylon sutures. The conjunctiva was closed with 10/0 nylon. A small bubble of gas (15% C3F8) was injected in AC with 30-gauge needle to prevent shallowing of the AC postoperatively. (The patient was not traveling by air postoperatively.) Subconjunctival steroid (dexamethasone 2 mg/0.5 ml) and antibiotic (cefazolin sodium 50 mg/0.5 ml) were given and the patient left the operating room in a good condition.

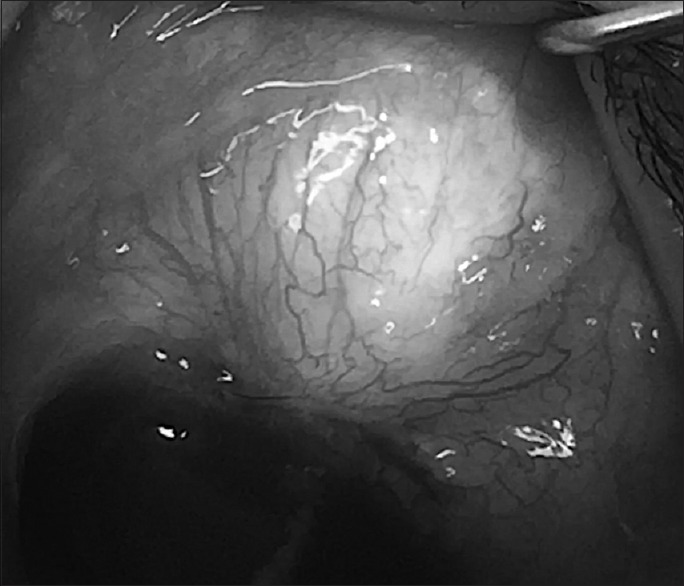

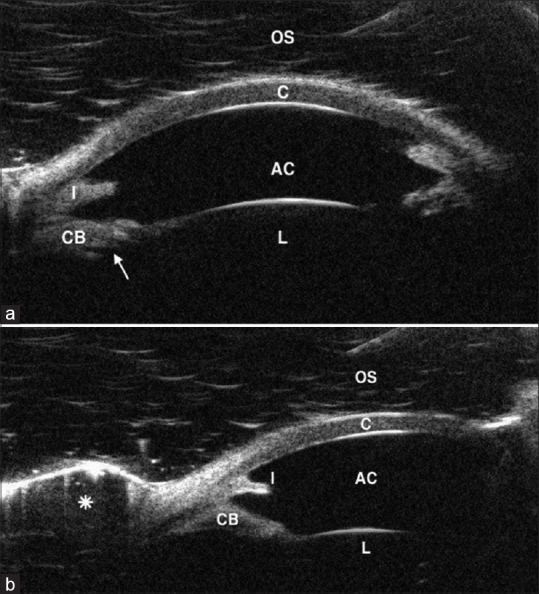

First day postoperation, the child was comfortable with deep AC and digital IOP around 15 mmHg in the left eye. The patient was discharged with steroid eye drops (prednisolone acetate 1%) every 2 h till seen next visit and topical antibiotic (ofloxacin 0.3%) four times daily for 2 weeks. She was also discharged with antiglaucoma eye drops of timololmaleate 0.5% twice daily, dorzolamide 2% twice daily in both eyes, and apraclonidine 0.5% twice daily and latanoprost 0.005% once at bed time in the right eye only. The patient had been kept on aqueous suppressants to the left eye as this may help prevent bleb encystment in the early postoperative phase. Three-week postoperation, examination under sedation was done again and showed formed bleb [Figure 1] in the left eye with no leak, deep AC, flat retina, and choroid with an IOP of 32 mmHg in the right eye and 9 mmHg in the left eye taken by tonopen. Given the early success of deep sclerectomy with microperforations in the left eye, the same procedure was performed 2 months later in the right eye. Six months postoperation in the left eye and 4 months in the right eye, the child maintained controlled IOPs, 13 mmHg in the right eye and 11 mmHg in the left taken by tonopen (on timololmaleate 0.5% twice daily and dorzolamide 2% twice daily in both eyes). Ultrasound biomicrosopy was done to both eyes to evaluate the blebs [Figure 2a and b].

Figure 1.

Formed bleb in the left eye, 4 months postoperation

Figure 2.

(a) UBM of the OS showing the cornea (C), deep AC, iris stump (I), enlarged CB with anterior rotation of its posterior part, the ciliary processes (arrow) and the lens (L). (b) UBM of the OS showing the cornea (C), deep AC, iris stump (I), enlarged CB with anterior rotation of its posterior part, the lens (L), and the formed bleb (asterisk). UBM: Ultrasound biomicroscopy, OS: Left eye, AC: Anterior chamber, CB: Ciliary body

Discussion

The incidence of glaucoma associated with aniridia has been reported to range from 6% to 75%.[1] The drainage angle in glaucoma patients with aniridia is thought to have developmental abnormalities which cause obstruction to the outflow of the aqueous humor through Schlemm's canal.[8]

Grant and Walton did gonioscopic examinations for aniridic patients with glaucoma and aniridic patients without glaucoma, and the result was that the stroma of the iris extends forward onto the trabecular meshwork, initially in the form of synechiae-like attachments, followed by a more homogenous sheet, resulting in eventual angle closure.[3]

Medical treatment for patients with congenital glaucoma associated with aniridia is frequently unsuccessful, and the need for surgical treatment is necessary.

Different surgical procedures have been reported for aniridia-associated glaucoma with varying success rates. Angle procedures can be successful. Adachi et al.[4] reported that 10 of 12 eyes obtained controlled IOP (defined as IOP < 21 mmHg) after one trabeculotomy (6 eyes) or two trabeculotomies (4 eyes).

They also reported that four eyes out of five needed further surgeries soon after the initial trabeculectomy because of failure. The IOP was controlled in one eye out of five after initial goniotomy with follow-up of 11 years.[4]

Several reports have indicated a poor outcome of conventional trabeculectomy in aniridia-associated glaucoma.[5]

GDDs are likely to carry a higher success rate than trabeculectomy in secondary congenital glaucomas. Arroyave et al.[6] reported the outcomes of GDD in the management of glaucoma associated with aniridia in eight eyes (250 mm2 Baerveldt glaucoma implant in six eyes, 350 mm2 Baerveldt glaucoma implant in one eye, and double-plate Molteno implant in one eye). Surgical success was achieved in seven eyes (88%) after 1 year. Loss of light perception occurred in one eye owing to retinal detachment. However, in young children, hypotony, tube malposition, and corneal decompensation are significant risks.[9]

Deep sclerectomy has been described as a successful and safe procedure for pediatric glaucoma.[7] Al-Obeidan et al. included small group of patients (13 eyes) with secondary glaucoma in their study cohort: Four eyes from patients with aniridia, the overall success rate among eyes with secondary congenital glaucoma was 9/13 or 69.2% for children who had a mean follow-up time of 35 months. The specific success rate for aniridia-associated glaucoma is not given in their report.[7] To ensure adequate filtration, we made three perforations in the (TDW) with a 30-gauge needle. One could argue that this is a modified trabeculectomy rather than a deep sclerectomy. However, deep sclerectomy, even with microperforations, may have a better outcome than trabeculectomy for a number of reasons: first, as no peripheral iridotomy is needed and a deep AC is maintained intraoperatively, there may be less postoperative inflammation and risk of scarring; second, there is a lower chance to damage the ciliary body (which is enlarged and more anterior in this case), the zonules, and the lens. Third, the success of surgery is dependent on an intrascleral aqueous lake, rather than a conjunctival bleb alone, which may be more prone to scarring. Intra- and post-operative hypotony is also far less likely with deep sclerectomy compared with trabeculectomy.[10]

Based on just this case report, the efficacy of deep sclerectomy with miroperforation in aniridia cannot be made. However, further exploration of this procedure for this condition is worth further evaluation.

Conclusion

Deep sclerectomy with microperforations may be a viable option in eyes with congenital glaucoma associated with aniridia after failed conventional trabeculotomy surgery. In young children, this may avoid GDD surgery till later in life, when tube position may be more stable.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the parents included.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nelson LB, Spaeth GL, Nowinski TS, Margo CE, Jackson L. Aniridia. A review. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984;28:621–42. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(84)90184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee H, Meyers K, Lanigan B, O'Keefe M. Complications and visual prognosis in children with aniridia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2010;47:205–10. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20090818-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant WM, Walton DS. Progressive changes in the angle in congenital aniridia, with development of glaucoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1974;72:207–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adachi M, Dickens CJ, Hetherington J, Jr, Hoskins HD, Iwach AG, Wong PC, et al. Clinical experience of trabeculotomy for the surgical treatment of aniridic glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:2121–5. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiggins RE, Jr, Tomey KF. The results of glaucoma surgery in aniridia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:503–5. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080160081036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arroyave CP, Scott IU, Gedde SJ, Parrish RK, 2nd, Feuer WJ. Use of glaucoma drainage devices in the management of glaucoma associated with aniridia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:155–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01934-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Obeidan SA, Osman Eel-D, Dewedar AS, Kestelyn P, Mousa A. Efficacy and safety of deep sclerectomy in childhood glaucoma in Saudi Arabia. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92:65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H, Khan R, O'Keefe M. Aniridia: Current pathology and management. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86:708–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandalos A, Sung V. Glaucoma drainage device surgery in children and adults: A comparative study of outcomes and complications. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;255:1003–11. doi: 10.1007/s00417-017-3584-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Razeghinejad MR, Fudemberg SJ, Spaeth GL. The changing conceptual basis of trabeculectomy: A review of past and current surgical techniques. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]