Abstract

Context:

Medication nonadherence is common among diabetics and it is one of the leading public health challenges.

Aims:

The aims of this study were to find the prevalence of nonadherence to diabetic medication and to identify various factors associated with it.

Settings and Design:

This study was conducted in 34 villages of the field practicing areas of rural health training center. This was a mixed method study design.

Subjects and Methods:

It was conducted among 328 type 2 diabetic patients. The quantitative data were collected from diabetic patients and qualitative data from health-care providers to identify their perceived barriers for patient's nonadherence.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Collected data were entered in Epi Info (3.5.3) and analyzed using SPSS version 24 software.

Results:

The prevalence of low adherence to diabetic medication was 45.4% among the study population. Bivariate analysis shows significant association with the patients who are literate (odds ratio [OR] = 0.6, confidence interval [CI] = 0.38–0.95), hypertensive (OR = 1.6, CI = 1.04–2.5), taking treatment from private facility (OR = 0.54, CI = 0.34–0.87), perceived lack of satisfaction with doctor–patient relationship (OR = 3.3, CI = 1.3–8.3), and perceived lack of knowledge about diabetes (OR = 2.03, CI = 1.29–3.1) with low adherence to medication.

Conclusions:

The prevalence of nonadherence to medications is common among diabetics in rural areas, and there is a need to strengthen the primary health-care system in addressing barriers to achieve better health outcomes.

Keywords: Adherence, drug therapy, India, rural, type 2 diabetes mellitus

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is considered to be one of the most psychologically and behaviorally demanding of the chronic diseases and it requires frequent self-monitoring of blood glucose, dietary modification, diet, and administration of medication under schedule.[1] Medication nonadherence is common among diabetics and it is one of the leading public health challenges.[2] In a resource-poor country like India with low literacy levels and restricted access to health-care facilities, the prevalence of medication nonadherence is much more common.[3]

Medication adherence has been defined by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research as the “extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval and dose of a dosing regimen.”[4] Poor treatment adherence that contributes to the suboptimal glycemic control continues to be one of the major barriers to effective diabetes management.[5] Suboptimal treatment can lead to increased use of health-care services (acute care and hospitalizations), reduction in patient's quality of life, and increased health-care costs (drug costs and medical costs).[6] In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasized that “increasing the effectiveness of adherence interventions may have a far greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medical treatments.”[7] Most of the available literature in India on medication nonadherence for diabetics are from hospital-based studies and it shows that it is common and various factors involved in the medication nonadherence are of behavioral and sociocultural factors.[8,9,10] There is a need for gathering of relevant information on various factors associated with medication nonadherence, which will help in identifying ways to overcome the barriers. Hence, the present community-based study was conducted to find the prevalence of nonadherence to diabetic medication and to identify various factors associated with it. The findings of the study will be helpful in addressing barriers of treatment adherence when developing programs for noncommunicable diseases at a community level.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study setting

The present cross-sectional study was undertaken in Thiruvennainallur of Villupuram district in Tamil Nadu, India, which is located about 200 km from Chennai. The district is having a literacy status of 71.8%, and agriculture is the main occupation.[11] The rural health training center (RHTC) located in Thiruvennainallur is the peripheral center of the Department of Community Medicine, Sri Manakula Vinayagar Medical College and Hospital, which undertook the present study. The field practicing areas of RHTC are 34 villages covering a population of 63,921. The RHTC also runs a noncommunicable disease clinic focusing on diabetes and hypertension management.

Study period

The present study was conducted for 6 months from November 2016 to April 2017.

Study design

We used mixed method study (quantitative and qualitative) design for the present study. A convergent design was used as a type of mixed method design in which quantitative data were collected among the diabetic patients and qualitative data including free-listing activity were done among health-care providers to identify their perceived barriers for patient's nonadherence. The reason for collecting both the quantitative and qualitative data was to bring together the strengths of both forms of research to corroborate results.[12]

Study subjects

Type 2 diabetic patients >18 years of both sexes were included in the study.

Quantitative method

Sample size

A representative sample size of 328 was selected. This sample size was calculated considering the prevalence of low treatment adherence at 30% with 95% confidence limits and a 7.5% precision, design effect of 2, and nonresponsive rate of 10% calculated using Epi Info (version 6.04d), developed by Center of Disease Control, Atlanta, USA, and the WHO.[8,13]

Sampling method

Two-stage cluster sampling method was used to select sample for the study. At the first stage, population proportional to size method was used to select 30 clusters from all 34 villages of the two primary health centers (PHCs). In the second stage, 11 diabetic patients were selected from each cluster using the random walk method. The random walk method was done in two steps; the first step was to select the starting point from the village and it was done after identifying the center of the village from thereby rotating a pen and followed the direction shown by the tip of the pen. The second step was done to selecting the first house in that direction, and the following houses were subsequently selected in clockwise direction till the 11 desired samples are achieved. In the selected house, patients having diabetes for more than 6 months were selected. If there was more than one diabetic person in the house, then one respondent was chosen by a lottery method. If there was no diabetic person in the selected house, then the next adjacent house was selected.

Data collection

The quantitative data collection was done by house-to-house visit. Trained medical interns and social workers identified 11 diabetic patients in each cluster. After obtaining informed consent, trained social workers and medical interns administered the questionnaire to the respondents consisting of sociodemographic factors, place of treatment, satisfaction, cost of treatment, type of treatment, satisfaction with treatment and perceived knowledge about diabetes, complications, and effects of missing doses. Medication adherence was measured using Morisky Medication Adherence Scale which is an 8-question scale. Each item in the scale measures a specific medication-taking behavior. Response categories were yes/no for each item with a dichotomous response, and for the last item, it was a 5-point Likert scale. The alpha reliability of the scale was 0.83. A score <6 were considered as low adherence. A score of 6 and 7 was considered as medium adherence and a score of 8 was considered as high adherence.[14]

Qualitative method

A purposive sample of 10 doctors, health-care workers, and pharmacists was selected from the two adjoining PHCs in the field practicing areas of RHTC. The participants were asked to make an individual-free list of the various reasons for poor adherence to medications among diabetic patients. Before each interview, the study details were explained to the participants. The interviews were conducted by an investigator who is trained in qualitative research in the local language (Tamil). Each interview took 10–15 min. The participants were informed of the purpose of the study. Qualitative data were collected by the principal investigator and notes were taken. The recruitment of participants was continued until saturation was achieved.

Analysis

Data thus collected were entered into Epi info (3.5.3) software package. The entered data were transferred and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for windows, version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) software. Mean, standard deviation, and proportions were calculated for the variables. Chi-square test was used for proportions as a test of significance. Multivariate analysis using logistic regression was used to identify the combination of variables that predict the risk for low treatment adherence. The reasons listed by the health-care providers for poor medication adherence were manually coded by the principal investigatorand analysis was done for calculating Smith's S value using Anthropac software (4.98.1/x) (Analytic Technologies, Lexington, KY, USA). Smith's S (Smith's saliency score) refers to the importance, representativeness, or prominence of items to individuals or to the group and is measured in three ways: word frequency across lists, word rank within lists, and a combination of these two.[15]

Ethical consideration

The study was carried out after obtaining approval from the Research Committee and Institutional Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from the individual respondents, and the ethical principles such as respect for persons, beneficence, and justice and nonmaleficence were adhered (IEC code No. 92/2016).

RESULTS

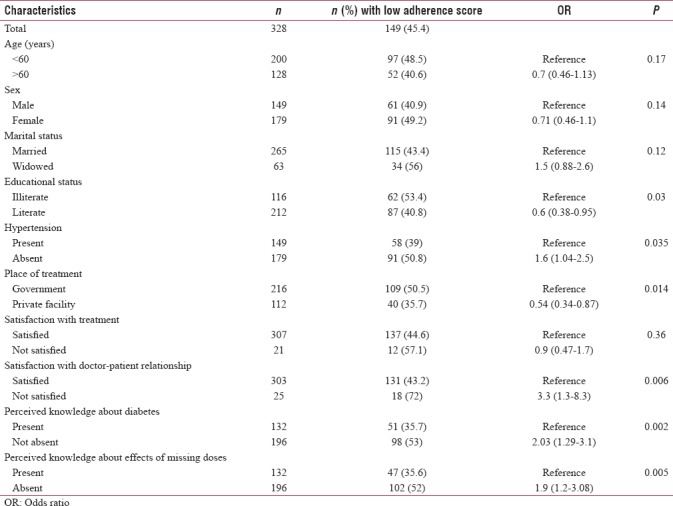

The mean age of the study participants was 57.3 ± 12.1 years. Among them, 149 (45.4%) were having low adherent score for their treatment. Bivariate analysis shows significant association with the patients who are literate (odds ratio [OR] = 0.6, confidence interval [CI] = 0.38–0.95), hypertensive (OR = 1.6, CI = 1.04–2.5), taking treatment from private facility (OR = 0.54, CI = 0.34–0.87), perceived lack of satisfaction with doctor–patient relationship (OR = 3.3, CI = 1.3–8.3), perceived lack of knowledge about diabetes (OR = 2.03, CI = 1.29–3.1), and perceived lack of knowledge about effect of missing doses (OR = 1.9, CI = 1.2–3.08). The mean duration of diabetes is significantly lower among the low adherence patients (P = −0.016). Cost of treatment was not significant associated with low adherence (P = −0.12) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristic features of the diabetic patients

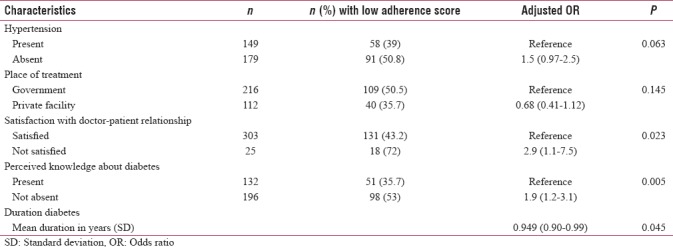

In multivariate analysis, three variables emerged as significant predictors for low adherence for the treatment of diabetes. The odds of low adherence for treatment among patients who are not satisfied with their relationship doctor increases by 2.9 times (CI = 1.1–7.5) as those who are satisfied with doctor–patient relationship. The odds of low adherence for treatment among patients perceived lack of knowledge about diabetes increased by 1.9 times (CI = 1.2–3.1) as those who are perceived of having knowledge about diabetes. The risk of low adherence to treatment decreases by 0.94 times (CI = 0.90–0.99) for each year increase in the duration of diabetes. The Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 value for the final model was 11.4% [Table 2].

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of various factors associated with low adherence for treatment

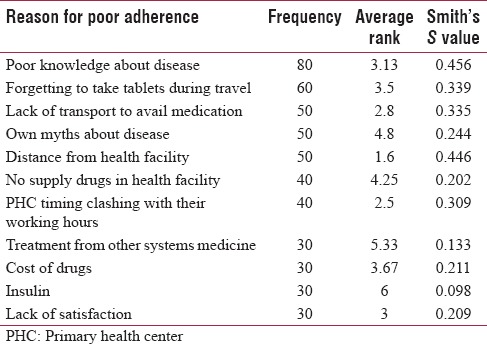

As explored in the free listing of health-care providers, the major reasons for poor adherence of diabetic medication are patient's poor knowledge about disease, distance from the health facility, forgetting medications during travel, lack of transport to avail drugs, inaccessible PHC timings, cost of drugs in private hospitals, side effects, patient's own myths about disease, and exploring other systems of medicine [Table 3].

Table 3.

Perceived barriers for diabetes medication adherence by health-care providers

DISCUSSION

The present cross-sectional study was conducted among diabetic patients and health-care providers to find the barriers for diabetic medication adherence among them. Overall, the prevalence of low adherence for treatment is 45.4%. Significant factors associated with low adherence for medication are illiterate, not having comorbid condition such as hypertension, poor satisfaction with government health facility, perceived poor satisfaction with doctor–patient relationship, perceived lack of knowledge about diabetes, perceived lack of knowledge about effect of missing doses, and initial years of having diabetes. Qualitative analysis shows that the common reasons are lack of knowledge about disease, distance, travel, lack of transport to health facility, inaccessible timing of the health facility, cost of drugs in private hospitals, and side effects.

The present study is a community-based study conducted among good sample of 328 diabetic patients of 34 villages using cluster sampling. It also provides health-care provider's perspectives for poor adherence to treatment among diabetics. It highlights the prevalence of low adherence to diabetic medications in a rural area and possible reasons for it.

In the present study, the prevalence of low adherence to diabetic medication was 45.4%. A hospital study from Puducherry reported that 26% of their study population had a low adherence score.[8] A hospital study from Mangalore shows that low adherence was found in 28% of the study participants.[10] A study from a diabetic clinic of Ethiopia shows that the proportion of patients with a low adherence score is 25.4%.[16] In the present study, the prevalence of low adherence for diabetic treatment was higher than the other studies because our study is a community-based study, which was done in a rural area, and they will be different from patients coming to tertiary care centers or diabetic clinics.

The significant factors for low medication adherence found in the present study are poor satisfaction with the doctor–patient relationship, lack of knowledge about disease, duration of diabetes, illiteracy, receiving treatment from government hospitals, traveling, and patient's own myths about the disease. Previous Indian studies show that lack of family support, distance from the hospital, cost of treatment, multiple drugs, side effects, and socioeconomic status leads to poor adherence.[2,8,9,10] Studies from Ethiopia and Botswana identified poor wealth status, using traditional treatment, service dissatisfaction, and HIV status associated with low adherence.[16,17]

In the present study, cost or socioeconomic status was not identified as a significant risk factor since most of the patients avail treatment from PHC, but health-care providers perceive cost as an important problem for patient's adherence in the private setup. Their problem lies with the fact of having lack of knowledge about disease or complications and dissatisfaction with services. Since most of the PHCs are manned by single or two medical officers, their other job responsibilities limits their time in spending towards diabetic patients to provide quality health education and quality care. Hence, there is a need to properly educate the patients about disease, its complication, need for adherence of treatment, side effects of treatment, and addressing their myths. Another important factor identified by patients and health-care provider is distance from the hospital and lack of transport; since most of patients are elderly and not having adequate family support, there is a need to provide drugs either in monthly mobile camps in those villages to improve the treatment adherence.

CONCLUSION

Epidemiological transition of India shows that prevalence of diabetes is increasing and it is becoming common in rural areas also and they are dependent on the primary health system to address their health concerns. Hence, there is a need to strengthen the existing noncommunicable disease setup of the primary health-care system in not only providing drugs but also in providing quality health education and quality care to promote drug adherence leading to better health outcomes among patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We also acknowledge the Management of Sri Manakula Vinayagar Medical College and Hospital for supporting the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kalyango JN, Owino E, Nambuya AP. Non-adherence to diabetes treatment at Mulago Hospital in Uganda: Prevalence and associated factors. Afr Health Sci. 2008;8:67–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zullig LL, Gellad WF, Moaddeb J, Crowley MJ, Shrank W, Granger BB, et al. Improving diabetes medication adherence: Successful, scalable interventions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:139–49. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S69651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medi RK, Mateti UV, Kanduri KR, Konda SS. Medication adherence and determinants of non-adherence among South Indian diabetes patients. J Soc Health Diabetes. 2015;3:48–51. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild CJ, Fuldeore MJ, Ollendorf DA, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: Terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11:44–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wangnoo SK, Maji D, Das AK, Rao PV, Moses A, Sethi B, et al. Barriers and solutions to diabetes management: An Indian perspective. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:594–601. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.113749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vervloet M, van Dijk L, Santen-Reestman J, van Vlijmen B, Bouvy ML, de Bakker DH, et al. Improving medication adherence in diabetes type 2 patients through Real Time Medication Monitoring: A Randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effect of monitoring patients' medication use combined with short message service (SMS) reminders. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. Adherence to Long-term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arulmozhi S, Mahalakshmi T. Self care and medication adherence among type 2 diabetics in Puducherry, Southern India: A hospital based study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:1–3. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7732.4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma T, Kalra J, Dhasmana DC, Basera H. Poor adherence to treatment: A major challenge in diabetes. JIACM. 2014;15:26–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Divya S, Nadig P. Factors contributing to non-adherence to medication among type 2 diabetes mellitus in patients attending tertiary care hospital in South India. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2015;8:274–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Register General of India. Census. 2011. [Last accessed on 2017 Sep 18]. Available from: http://www.census2011.co.in/census/district/27-viluppuram.html .

- 12.Creswall JW. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. California: SAGE Publications; 2015. p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dongre AR, Rajendran KP, Kumar S, Deshmukh PR. The effect of community-managed palliative care program on quality of life in the elderly in rural Tamil Nadu, India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2012;18:219–25. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.105694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:348–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15.Anthropac Software – Version 4.98. Analytic Technologies. 1996. [Last accessed on 2017 Sep 05]. Available from: http://www.analytictech.com/anthropac/apacdesc.htm .

- 16.Abebe SM, Berhane Y, Worku A. Barriers to diabetes medication adherence in North West Ethiopia. Springerplus. 2014;3:195. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rwegerera GM, Moshomo T, Gaenamong M, Oyewo TA, Gollakota S, Mhimbira FA, et al. Antidiabetic medication adherence and associated factors among patients in Botswana: Implications for the future. Alex J Med. 2017;54:103–9. Doi: 10.1016/j.ajme. 2017.01.005. [Google Scholar]