Abstract

Background

Marker-assisted breeding will move forward from introgressing single/multiple genes governing a single trait to multiple genes governing multiple traits to combat emerging biotic and abiotic stresses related to climate change and to enhance rice productivity. MAS will need to address concerns about the population size needed to introgress together more than two genes/QTLs. In the present study, grain yield and genotypic data from different generations (F3 to F8) for five marker-assisted breeding programs were analyzed to understand the effectiveness of synergistic effect of phenotyping and genotyping in early generations on selection of better progenies.

Results

Based on class analysis of the QTL combinations, the identified superior QTL classes in F3/BC1F3/BC2F3 generations with positive QTL x QTL and QTL x background interactions that were captured through phenotyping maintained its superiority in yield under non-stress (NS) and reproductive-stage drought stress (RS) across advanced generations in all five studies. The marker-assisted selection breeding strategy combining both genotyping and phenotyping in early generation significantly reduced the number of genotypes to be carried forward. The strategy presented in this study providing genotyping and phenotyping cost savings of 25–68% compared with the traditional marker-assisted selection approach. The QTL classes, Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 and Sub1 + qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 in Swarna-Sub1, Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY1.2, Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.2 and Sub1 + qDTY2.2 + qDTY12.1 in IR64-Sub1, qDTY2.2 + qDTY4.1 in Samba Mahsuri, Sub1 + qDTY3.1 + qDTY6.1 + qDTY6.2 and Sub1 + qDTY6.1 + qDTY6.2 in TDK1-Sub1 and qDTY12.1 + qDTY3.1 and qDTY2.2 + qDTY3.1 in MR219 had shown better and consistent performance under NS and RS across generations over other QTL classes.

Conclusion

“Deployment of this procedure will save time and resources and will allow breeders to focus and advance only germplasm with high probability of improved performance. The identification of superior QTL classes and capture of positive QTL x QTL and QTL x background interactions in early generation and their consistent performance in subsequent generations across five backgrounds supports the efficacy of a combined MAS breeding strategy”.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12284-018-0227-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Drought, Drought yield QTLs, Marker-assisted selection breeding strategy, Pyramiding, Rice

Background

Rice breeding methodology followed in the past as well as the present ranges from conventional breeding (Singh et al. 1998; Xinglai et al. 2006; Baenziger et al. 2008; Obert et al. 2008; Brick et al. 2008; Kumar et al. 2014), hybrid breeding (Shull 1948; Reif et al. 2005), marker-assisted breeding (MAB; Price 2006; McNally et al. 2009; Breseghello and Sorrells 2006; Kumar et al. 2014), and transgenic breeding (Bhatnagar-Mathur et al. 2008; Yang et al. 2010) to genome-wide association studies and genomic selection (Brachi et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2010; Begum et al. 2015; Biscarini et al. 2016). Grain yield as well as resistance against existing as well as emerging biotic and abiotic stresses is not a straightforward result of understanding the physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of genetic loci. Three major interactions, i) interaction between genes for the same trait, ii) genes for different traits, and iii) interactions of genes with environments and genetic background restricting the use of QTLs in introgression programs (Kumar et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2012; Xue et al. 2009; Almeida et al. 2013; Elangovan et al. 2008; Cuthbert et al. 2008; Heidari et al. 2011; Bennett et al. 2012). Selection of an appropriate donor/recipient to create desirable variability (Mondal et al. 2016; Dixit et al. 2014) and precise selection under variable conditions, environments, and stress intensity levels is must. A large population size is generally required for selecting appropriate plants possessing the needed gene combinations, desired plant type, and higher yield. An integration of modern, novel, and affordable breeding strategies with knowledge of associated mechanisms, interactions, and associations among related or unrelated traits/factors is necessary in rice breeding improvement programs.

The conventional breeding approach involving a series of phenotyping and genotyping screening of a large population to obtain desired variability and a high frequency of favorable genes in combination was earlier followed by several drought breeding program (Kumar et al. 2014). A conventional breeding approach involving sequential selection of large segregating populations for biotic (bacterial late blight, blast) and abiotic stresses (drought, submergence) across generations helped breeders to develop breeding lines combining tolerance of both stresses. Superior lines in terms of acceptable plant type, grain yield, and quality traits and stable performance under different environments are promoted for release (Kumar et al. 2014; Sandhu and Kumar 2017).

Modern molecular breeding strategies have been implemented to practice a more precise, quick and cost-effective breeding strategy compared to traditional conventional rice breeding improvement programs. Previously, many QTLs for grain yield under drought using different strategies such as selective/whole-genome genotyping, bulk segregant analysis (Vikram et al. 2011; Yadaw et al. 2013; Mishra et al. 2013; Sandhu et al. 2014; Ghimire et al. 2012) have been identified. The successful introgression and pyramiding of the identified genetic regions in different genetic backgrounds using marker-assisted backcrossing (Yadaw et al. 2013; Mishra et al. 2013; Sandhu et al. 2014; Venuprasad et al. 2009; Sandhu et al. 2013; Sandhu et al. 2015) has been reported. Accurate repetitive phenotyping in multi-locations and multi-environments under variable growing conditions is required to evaluate the performance and adaptability of the developed MAB products. There have been several examples of introgression of single genes for both biotic and abiotic stresses (gall midge – Das and Rao 2015; blast – Miah et al. 2016; brown plant hopper – Jairin et al. 2009; submergence – Septiningsih et al. 2009) in the background of popular high-yielding varieties as well as introgression of more than one gene for biotic stresses (xa5 + xa13 + Xa21 - Singh et al. 2001, Kottapalli et al. 2010; Xa21 + xa13 - Singh et al. 2011) for oligogenic traits controlled by major genes.

Several major large-effect QTLs such as qDTY1.1 (Vikram et al. 2011; Ghimire et al. 2012), qDTY2.1 (Venuprasad et al. 2009), qDTY2.2 (Venuprasad et al. 2007; Swamy et al. 2013), qDTY3.1 (Venuprasad et al. 2009), qDTY4.1 (Swamy et al. 2013), qDTY6.1 (Venuprasad et al. 2012), qDTY10.1 (Swamy et al. 2013), and qDTY12.1 (Bernier et al. 2007) for grain yield under reproductive-stage (RS) drought stress have been identified. A total of 28 significant marker trait associations were detected for yield-related trait in genome wide association study of japonica rice under drought and non-stress conditions (Volante et al. 2017). Moreover, each of these identified QTLs has shown a yield advantage of 300–500 kg ha− 1 under RS drought stress depending upon the severity and timing of the drought occurrence. However, in order to provide farmers with an economic yield advantage under drought, it is necessary that two or more such QTLs be combined to obtain a targeted yield advantage of 1.0 t ha− 1 under severe RS drought stress (Sandhu and Kumar 2017; Kumar et al. 2014).

Polygenic traits governed by more than one gene within the identified QTLs do not follow the simple rule of single gene introgression. The positive/negative interactions of alleles within QTLs and with the genetic background (Dixit et al. 2012a, b), pleiotropic effect of genes and linkage drag (Xu and Crouch 2008; Vikram et al. 2015; Vikram et al. 2016; Bernier et al. 2007; Venuprasad et al. 2009; Vikram et al. 2011; Venuprasad et al. 2012) played an important role in determining the effect of introgressed loci. The reported linkage drag of the qDTY QTLs has been successfully broken and individual QTLs have been introgressed into improved genetic backgrounds (Vikram et al. 2015). To identify an appropriate number of plants with positive interactions and high phenotypic expression, MAB requires genotyping and phenotyping of large numbers of plants/progenies in each generation from F2 onwards. In this case, MAB for more than two genes/QTLs is not a cost-effective approach. The population size to be genotyped and phenotyped for complex traits such as drought increases significantly as two or more QTLs are considered for introgression. To enhance breeding capacity to develop climate-resilient rice cultivars, there is a strong need to develop a novel, cost/labor-effective, and high-throughput breeding strategy. The effective integration of molecular knowledge into breeding programs and making MAB cost-effective enough to be fully adapted by small- or moderate-sized breeding programs are still a challenge.

In the present study, we closely followed the marker-assisted introgression of two or more QTLs for RS drought stress in the background of rice varieties; Swarna-Sub1, IR64-Sub1, Samba Mahsuri, TDK1-Sub1, and MR219 from F3 to F6/F7/F8 generations. Class analysis for different combinations of QTLs for yield under RS drought stress as well as under irrigated control conditions was performed with the aim to understand the effectiveness of synergistic effect of phenotyping and genotyping in early generations on selection of better progenies. We hypothesized that a QTL class that has performed well in an early generation may maintain its performance across generations/years and seasons.

Results

Performance of lines introgressed with QTLs for grain yield under drought

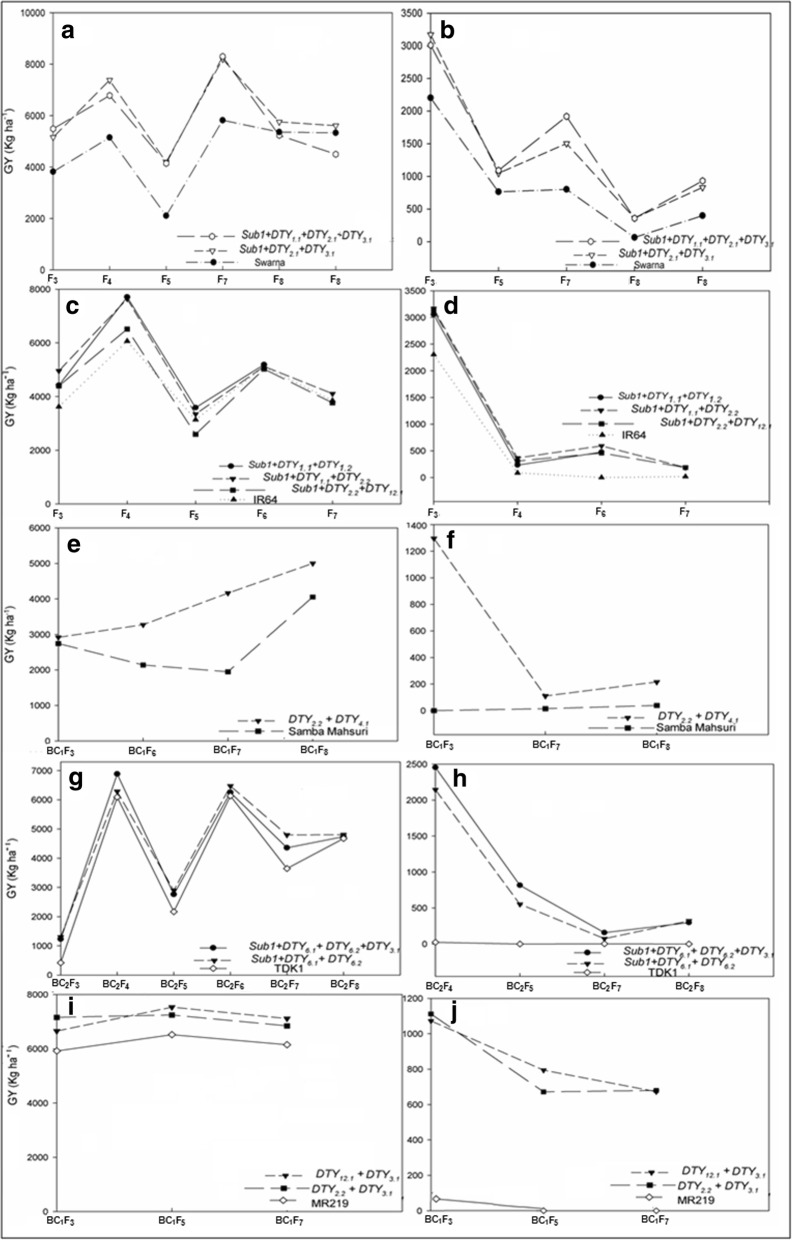

The pyramided lines with either a single gene or in combination of genetic loci associated with grain yield under drought produced a grain yield advantage over the recipient parent across backgrounds and generations (Fig. 1a to j). The pyramided lines with two or more QTLs had shown a high grain yield advantage in Swarna-Sub1 (Table 1), IR64-Sub1 (Table 2), Samba Mahsuri (Table 3), TDK1-Sub1 (Table 4), and MR219 (Table 5) backgrounds. In a Swarna-Sub1 background, a grain yield advantage of 76.2–2478.5 kg ha− 1 and 395.7–2376.3 kg ha− 1 under non-stress (NS) in Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 and Sub1 + qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 pyramided lines, respectively, was observed. Under RS drought stress, a grain yield advantage of 292.4–1117.8 and 284.2–2085.5 kg ha− 1 in Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 and Sub1 + qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 pyramided lines, respectively, was observed (Table 1). In an IR64-Sub1 background, the pyramided lines (Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.2) showed a grain yield advantage ranging from 21.3 to 1571.4 kg ha− 1 and 170.4 to 864.7 kg ha− 1 under NS and RS drought stress, respectively. Under RS drought stress, the pyramided lines (Sub1 + qDTY3.2 + qDTY2.3 + qDTY12.1) showed a grain yield advantage of 217.1 to 719.1 kg ha− 1 in an IR64-Sub1 background (Table 2). The grain yield advantage ranged from 48.0 to 2216.9 kg ha− 1 and 95.5 to 1296.4 kg ha− 1 under NS and RS drought stress conditions, respectively, in Samba Mahsuri introgressed with qDTY2.2 + qDTY4.1 (Table 3). In TDK1-Sub1 pyramided lines (Sub1 + qDTY3.1 + qDTY6.1 + qDTY6.2), the grain yield advantage ranged from 65.2 to 792.0 kg ha− 1 and 155.9 to 2429.5 kg ha− 1 under NS and RS drought stress conditions, respectively (Table 4). The pyramided lines with qDTY12.1 + qDTY3.1 and qDTY2.2 + qDTY3.1 showed a grain yield advantage of 735.1–1012.8 kg ha− 1 and 324.0–1240.9 kg ha− 1, respectively, under NS and 672.3–1059.5 kg ha− 1 and 571.4–1099.3 kg ha− 1, respectively, under RS drought stress conditions in an MR219 background (Table 5).

Fig. 1.

a Graph representing the generation (X axis) and mean grain yield (Y axis) of selected SwarnaSub1 pyramided lines under NS (control); b Graph representing the generation (X axis) and mean grain yield (Y axis) of selected SwarnaSub1 pyramided lines under RS drought stress; c Graph representing the generation (X axis) and mean grain yield (Y axis) of selected IR64Sub1 pyramided lines under NS (control); d Graph representing the generation (X axis) and mean grain yield (Y axis) of selected IR64Sub1 pyramided lines under RS drought stress; e Graph representing the generation (X axis) and mean grain yield (Y axis) of selected Samba Mahsuri pyramided lines under NS (control); f Graph representing the generation (X axis) and mean grain yield (Y axis) of selected Samba Mahsuri pyramided lines under RS drought stress; g Graph representing the generation (X axis) and mean grain yield (Y axis) of selected TDK1Sub1 pyramided lines under NS (control); h Graph representing the generation (X axis) and mean grain yield (Y axis) of selected TDK1Sub1 pyramided lines under RS drought stress; i Graph representing the generation (X axis) and mean grain yield (Y axis) of selected MR219 pyramided lines under NS (control); and (j) Graph representing the generation (X axis) and mean grain yield (Y axis) of selected MR219 pyramided lines under RS drought stress

Table 1.

Mean comparison of QTL classes of grain yield (kg ha− 1) across F3 to F8 generations under reproductive-stage drought stress and irrigated non-stress control conditions in Swarna-Sub1 background at IRRI, Philippines

| QTL class | QTL | 2012DS | 2012DS | 2012DS | 2012DS | 2012DS | 2012WS | 2013DS | 2013DS | 2014DS | 2014DS | 2015WS | 2015WS | 2016DS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS_Med | RS_Med | RS_ Med | NS_Late | RS_Late | NS | NS | RS | NS | RS | NS | RS | RS | ||

| F3 | F3 | F3 | F3 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F5 | F7 | F7 | F8 | F8 | F8 | ||

| Population size | ||||||||||||||

| 663 | 366 | 304 | 91 | 84 | 754 | 432 | 432 | 432 | 432 | 52 | 52 | 52 | ||

| A | qDTY 1.1 | 4906 bc | 2677 cde | 2894 bcf | 6766 gh | 3674 c | 3925 bc | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| B | Sub1+ qDTY 1.1 | 5431 efg | 2228ab | 2930 bg | 4141 a | 3652 bc | 3536 bcd | – | – | – | – | 5191 c | 68.24 a | 579 b |

| C | DTY 2.1 | 4811cde | 2828 efg | 2962 abg | 4265 ab | 3719 bc | 4176 abc | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D | Sub1+ qDTY 2.1 | 5084 cf | 2452 bcde | 2776 abde | 4649 ab | 3554 bc | 2729 a | 4109 bc | 793 ac | – | – | – | – | – |

| E | qDTY 3.1 | 5098 cdeg | 3010 gh | 3001 bg | 4987 ac | 2658 b | – | 4135 bc | 973 ac | 7941 ab | 1868 cd | – | – | – |

| F | Sub1+ qDTY 3.1 | 4705 bc | 3027 fh | 2984 bg | – | 3315 bc | 4663 ac | 4107 cd | 1097 cd | 7934 b | 1838 cd | 4940 b | 97.96 a | 677 c |

| G | Sub1 | 5430 cf | 2642 bcefh | 2334 ab | 5338 bcd | 3204 bc | 3515 a | 2948 abc | 530 ac | – | – | – | – | – |

| H | qDTY 1.1 + qDTY 2.1 | 5394 df | 2653 ce | 3131 efg | 6445 fg | 3671 c | 4308 ab | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| I | Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.1 | 5444 ef | 2428 ac | 3133 efg | 6642 fgh | 3636 c | 4460 ab | 3710 bc | 605 ab | – | – | – | – | – |

| J | qDTY1.1 + qDTY3.1 | 4788 c | 2693 de | 2945 be | 6395 fg | 3481 bc | 4288 ab | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| K | Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY3.1 | 4989 cd | 2832 efg | 3003 ceg | 6639 efh | 3377 bc | 5183 c | 3456 b | 677 ad | – | – | 4676 a | 159.19 b | 566 b |

| L | qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 | 5265 bdf | 2998 fh | 2955 bg | – | 3620 bc | 4623 ac | 4116 cd | 992 bcd | 7932 ab | 1672 bc | – | – | – |

| M | qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 + Sub1 | 5154 cf | 3172 h | 3162 efg | 7380 hi | 3714 bc | – | 4192 cd | 1048 bcd | 8194 b | 1503 ab | 5754 g | 360.16 c | 830 d |

| N | qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 | 5055 cd | 2845 df | 3130 dg | 7373 hi | 3505 c | 4807 bc | 3912 bd | 1073 c | 8043 b | 1854 d | – | – | – |

| O | Sub1+ qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 | 5484 ef | 3010 gh | 3167 fg | 6780 gh | 3859 c | 4838 bc | 4141 c | 1092 c | 8297 b | 1918 d | 5434 e | 356.81 c | 931 d |

| X | Parent | 3818 a | 2203 ab | 2465 a | 5827 cde | 2828 ab | 5146 c | 2106 a | 764 ac | 5818 a | 799 a | 5358 f | 64.45 a | 398 a |

| Trial mean | 5077 | 2691 | 2937 | 6044 | 3474 | 4760 | 3615 | 838 | 7878 | 1652 | 5222 | 175 | 605 | |

| F- value | 3.68 | 7.39 | 2.45 | 19.77 | 1.21 | 6.04 | 13.22 | 1.79 | 6.88 | 3.75 | 5.38 | 6.16 | 3.93 | |

| p-value | 0.0168 | <.0001 | 0.0018 | 0.0001 | 0.2838 | <.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0559 | 0.0003 | 0.0008 | <.0001 | 0.2991 | 0.368 | |

The letter display are QTL class labels ordered by mean grain yield of QTL class. Means followed by the same letter (within a column) are not significantly different, DS dry season, WS wet season, NS non-stress, RS reproductive-stage drought stress, Med medium duration, Late late duration, X recipient parent (no QTL)

Table 2.

Mean comparison of QTL classes of grain yield (kg ha− 1) across F3 to F7 generations under reproductive-stage drought stress and irrigated non-stress control conditions in IR64-Sub1 background at IRRI, Philippines

| QTL class | QTL | 2013WS | 2013WS | 2014DS | 2014DS | 2014WS | 2015DS | 2015DS | 2015WS | 2015WS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | RS | NS | RS | NS | NS | RS | NS | RS | ||

| F3 | F3 | F4 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F6 | F7 | F7 | ||

| Population size | ||||||||||

| 467 | 467 | 194 | 194 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 18 | 18 | ||

| A | Sub1+ qDTY1.1 + qDTY1.2 + qDTY12.1 | 4137 ac | 3621 cde | 7553 bdf | 584 g | – | – | – | – | – |

| B | Sub1+ qDTY1.1 + qDTY1.2 + qDTY2.2 + qDTY12.1 | 3640 ac | 2605 a | 7968 bdf | 196 abc | – | – | – | – | – |

| C | Sub1+ qDTY1.1 + qDTY1.2 + qDTY2.2 | 4986 c | 2734 ab | 5996 abc | 377def | – | – | – | – | – |

| D | Sub1+ qDTY1.1 + qDTY1.2 | 4418 cd | 3054 abc | 7709 cef | 232 abc | 3585 ab | 5192 a | 477 bcd | – | – |

| E | Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.2 + qDTY12.1 | 3589 ac | 2634 abc | – | 273 be | 3976 a | 420 bce | – | – | |

| F | Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.2 | 4953 ac | 3169 abe | 7637 bdf | 367 ceg | 3347 ab | 5120 a | 592 bf | 4105 a | 188 a |

| G | Sub1 + qDTY 1.1 | 4413 ac | 2677 ab | 8224 cef | 410 eg | – | – | – | – | – |

| H | Sub1 + qDTY 1.2 + qDTY 12.1 | 4001 ac | 2963 abc | 6660 abe | 245 be | – | 5468 a | 252 ab | – | – |

| I | Sub1 + qDTY1.2+ qDTY2.2 + qDTY12.1 | 5370 cb | 3352 abe | 8790 bf | 259 be | – | – | – | – | – |

| J | Sub1 + qDTY 12.1 | 4380 cd | 2690 abd | 6117 ab | 189 bc | 3066 ab | 5125 a | 372 abc | 3997 a | 64 a |

| K | Sub1 + qDTY2.2 + qDTY12.1 | 4395 cd | 3130 bc | 6512 ab | 308 ae | 2592 a | 5026 a | 459 bc | 3762 a | 186 a |

| L | Sub1 + qDTY 2.2 | 4252 cd | 3767 e | 7893 cf | 223 abc | – | – | – | – | – |

| M | Sub1 + qDTY2.3 + qDTY12.1 | 3168 ac | 3084 abe | 8532 cef | 194 be | – | – | – | – | – |

| N | Sub1 + qDTY 2.3 | 3145 ab | 2602 a | 7080 bde | 244 abcd | – | – | – | – | – |

| O | Sub1 + qDTY3.2 + qDTY12.1 | 3670 ac | 2746 abd | 7145 abf | 263 bef | – | – | – | – | – |

| P | Sub1 + qDTY3.2 + qDTY2.2 + qDTY12.1 | 3109 ac | 2728 abd | 7798 bdf | 197 be | – | – | – | – | – |

| Q | Sub1 + qDTY3.2 + qDTY2.2 | 3055abd | 2526 a | 6441 ab | 220 abcd | 2381 a | 4398 a | 761 f | – | – |

| R | Sub1 + qDTY3.2 + qDTY2.3 + qDTY12.1 | 2845 ac | 2931 abc | 6469 abc | 304 abcd | 2293 a | 4570 a | 719 def | 3883 a | 275 a |

| S | Sub1 + qDTY3.2 + qDTY2.3 | 1688 a | 2891 abe | 5319 a | 304 bef | – | 4727 a | 255 ab | – | – |

| T | Sub1 + qDTY 3.2 | 3444 ac | 3427 be | 6230 ad | 124 b | – | – | – | – | – |

| X | Parent | 3620 ac | 2305 a | 6066 abf | 87 abc | 3139 ab | 5099 a | 0a | 3849 a | 18 a |

| Trial mean | 3853 | 2998 | 7181 | 277 | 3024 | 4870 | 862 | 3943 | 128 | |

| F- value | 1.59 | 2.88 | 2.92 | 3.22 | 2.83 | 2.26 | 4.32 | 1.54 | 1.53 | |

| p-value | 0.2956 | 0.006 | 0.0006 | 0.0011 | 0.0363 | 0.404 | 0.0004 | 0.5566 | 0.5585 | |

The letter display are QTL class labels ordered by mean grain yield of QTL class. Means followed by the same letter (within a column) are not significantly different, DS dry season, WS wet season, NS non-stress, RS reproductive-stage drought stress, X recipient parent (no QTL)

Table 3.

Mean comparison of QTL classes of grain yield (kg ha−1) across BC1F3 to BC1F8 generations under reproductive-stage drought stress and irrigated non-stress control conditions in Samba Mahsuri background at IRRI, Philippines

| QTL class | QTL | 2013DS | 2013DS | 2014WS | 2015WS | 2015WS | 2016DS | 2016DS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | RS | NS | NS | RS | NS | RS | ||

| BC1F3 | BC1F3 | BC1F6 | BC1F7 | BC1F7 | BC1F8 | BC1F8 | ||

| Population size | ||||||||

| 42 | 42 | 70 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | ||

| A | qDTY 2.2 | 2020 a | 1069 bc | 3405 b | 3327 b | 44 a | – | – |

| B | qDTY 4.1 | 1900 a | 894 b | 3340 b† | 4727 d† | 184 b† | 5643 b† | 33 a |

| C | qDTY2.2 + qDTY4.1 | 2916 b | 1296 c | 3270 b | 4161 c | 110 ba | 4999 a | 216 b |

| X | Parent | 2742 b | 0 a | 2137 a | 1945 a | 15 a | 4051 a | 39 a |

| Trial Mean | 2395 | 815 | 3038 | 3540 | 88 | 5198 | 96 | |

| F- value | 31.22 | 46.37 | 11.18 | 43.03 | 2.12 | 19.98 | 62.66 | |

| p-value | 0.0089 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.09 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |

The letter display are QTL class labels ordered by mean grain yield of QTL class. Means followed by the same letter (within a column) are not significantly different, DS dry season, WS wet season, NS non-stress, RS reproductive-stage drought stress, X recipient parent (no QTL), †Mean data of only 2 lines

Table 4.

Mean comparison of QTL classes of grain yield (kg ha−1) across BC2F3 to BC2F8 generations under reproductive-stage drought stress and irrigated non-stress control conditions in TDK-Sub1 background at IRRI, Philippines

| QTLclass | QTL | 2013WS | 2014DS | 2014WS | 2015DS | 2015WS | 2016DS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS | NS | RS | NS | NS | RS | NS | RS | NS | RS | ||

| BC2F3 | BC2F4 | BC2F4 | BC2F5 | BC2F6 | BC2F6 | BC2F7 | BC2F7 | BC2F8 | BC2F8 | ||

| Population size | |||||||||||

| 843 | 231 | 231 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | ||

| A | Sub1 + qDTY6.1 + qDTY6.2 + qDTY3.1 | 1232 gh | 6883 bc | 2453 c | 2763 bc | 6252bc | 816 f | 4356 ab | 158 de | 4739 ab | 298 cd |

| B | qDTY 6.1 + qDTY 6.2 + qDTY 3.1 | 1298 gh | 6289 b | 2069 b | 2629 ac | 6174 c | 250 bc | 4966 cd | 122 cd | 4871 ab | 278 c |

| C | Sub1+ qDTY6.1 + qDTY6.2 | 1301 gi | 6289 abc | 2143 bc | 2897 bcd | 6475 c | 552 de | 4797 bd | 73.83 abc | 4804 b | 320 cd |

| D | Sub1+ qDTY 6.1 + qDTY 3.1 | 1091 fde | 5707 ab | 2120 bc | 3476 c | 5958 ab | 368 bd | 4657 bc | 75 bc | 4780 ab | 179 ac |

| E | Sub1+ qDTY6.2 + qDTY3.1 | 1178 ge | 6061 abc | 2112 bc | 2576 ac | 5157 a | 274 bc | – | – | – | – |

| F | qDTY6.1 + qDTY6.2 | 998 cd | 3890 a | 2126 bc | 2307 ac | 4799 a | 501 cde | – | – | – | – |

| G | qDTY6.1 + qDTY3.1 | 1012 ge | 5874 ab | 1959 b | 2704 ac | 6775 c | 211.97 b | 5074 d | 73 b | 4793 ab | 113 ab |

| H | qDTY6.2 + qDTY3.1 | 1134 fe | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| I | Sub1 + qDTY 6.2 | 1051 ce | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| J | Sub1+ qDTY 6.1 | 1446 j | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| K | Sub1 + qDTY 3.1 | 1376 hij | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| L | qDTY 6.2 | 1416 ij | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| M | qDTY 6.1 | 1308 gh | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| N | qDTY 3.1 | 1217 fg | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| X | Parent | 421 a | 6091 abc | 24 a | 2167 a | 6135 bc | 0 a | 3647 a | 2 a | 4674 a | 0 a |

| Trial mean | 1165 | 5886 | 1863 | 2715 | 6091 | 409 | 4583 | 84 | 4760 | 198 | |

| F- value | 34.1 | 6.6 | 1.03 | 3.21 | 4.99 | 16.32 | 6.44 | 6.0 | 5.32 | 5.0 | |

| p-value | <.0001 | 0.0012 | 0.4207 | 0.0341 | 0.0105 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0013 | 0.0046 | |

The letter display are QTL class labels ordered by mean grain yield of QTL class. Means followed by the same letter (within a column) are not significantly different, DS dry season, WS wet season, NS non-stress, RS reproductive-stage drought stress, X recipient parent (no QTL)

Table 5.

Mean comparison of QTL classes of grain yield (kg ha−1) across BC1F3 to BC1F7 generations under reproductive-stage drought stress and irrigated non-stress control conditions in MR219 background at IRRI, Philippines

| QTL class | QTL | 2013DS | 2014DS | 2015DS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | RS | NS | RS | NS | RS | ||

| BC1F3 | BC1F3 | BC1F5 | BC1F7 | BC1F7 | |||

| Population size | |||||||

| 214 | 214 | 620 | 620 | 70 | 70 | ||

| A | qDTY 12.1 | 6229 a | 654 b | 6967 b | 301 a | – | – |

| B | qDTY12.1 + qDTY2.2 | 6633 b | 761 bc | 7364 ac | 598 b | 5986 a | 540 c |

| C | qDTY12.1 + qDTY3.1 | 6652 ac | 1072 d | 7532 cd | 794 e | 7111 c | 672 d |

| D | qDTY 2.2 | 6760 ab | 904 cd | 7079 ba | 669 bc | 6957 c | 393 b |

| E | qDTY2.2 + qDTY3.1 | 7158 bc | 1112 d | 7243 cd | 663 c | 6843 bc | 679 d |

| F | qDTY2.2 + qDTY3.1 + qDTY12.1 | 6799 ab | 642 b | 7106 ad | 442 b | 6674 bc | 578 cd |

| G | qDTY 3.1 | 6488 a | 890 c | 7374 ac | 568 c | 6923 bc | 537 bcd |

| X | Parent | 5917 ab | 13 a | 6519 b | 0 ab | 6148 ab | 0 a |

| Trial mean | 6705 | 781 | 7173 | 505 | 6663 | 486 | |

| F- value | 2.0 | 11.76 | 9.45 | 19.39 | 7.76 | 6.18 | |

| p-value | 0.05 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0004 | <.0001 | |

The letter display are QTL class labels ordered by mean grain yield of QTL class. Means followed by the same letter (within a column) are not significantly different, DS dry season, WS wet season, NS non-stress, RS reproductive-stage drought stress, X recipient parent (no QTL)

Performance of pyramided lines in the F3 generation

Mean performances of QTL classes from F3 to F7/F8 of Swarna-Sub1, IR64-Sub1, Samba Mahsuri, TDK1-Sub1, and MR219 pyramided lines are shown in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively.

In a Swarna background, two classes (Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 and Sub1 + qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1) showed higher performance in F3 under both NS and RS drought stress (Table 1). In an IR64-Sub1 background, three classes (Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY1.2, Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.2, Sub1 + qDTY2.2 + qDTY12.1) showed higher performance under NS and RS drought stress both, whereas Sub1 + qDTY3.2 + qDTY2.3 + qDTY12.1 performed better under RS drought stress only in F3 (Table 2). In Samba Mahsuri background, the QTL class qDTY2.2 + qDTY4.1 showed a higher performance than a single QTL under both NS and RS drought stress in F3 (Table 3). In a TDK1-Sub1 background, the classes consisting of pyramided lines with Sub1 + qDTY3.1 + qDTY6.1 + qDTY6.2 and Sub1 + qDTY6.1 + qDTY6.2 showed a stable and high effect across variable growing conditions in F3 (Table 4). In the MR219 background, pyramided lines having qDTY12.1 + qDTY3.1 and qDTY2.2 + qDTY3.1 showed significant yield advantage under both NS and RS drought stress (Table 5).

Validation of MAB-selected class performance in subsequent generations

The performance of pyramided line classes identified as superior in the F3 generation was found to be consistent and higher than other QTL classes throughout F4, F5, F6, F7, and F8 generations (except where the number of lines per class was less) across all five studied backgrounds in the present study. The high mean grain yield QTL classes in the F3 generation, Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 and Sub1 + qDTY2.1 + qDTY3.1 in a Swarna background (Table 1), qDTY2.2 + qDTY4.1 in a Samba Mahsuri background (Table 3), and Sub1 + qDTY3.1 + qDTY6.1 + qDTY6.2 and Sub1 + qDTY6.1 + qDTY6.2 in a TDK1-Sub1 background (Table 4) had maintained their high mean grain yield performance from the F4 to F8 generations over other QTL classes. The low mean yield performers in the F3 generation, Sub1 + qDTY1.1, Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY3.1 in a Swarna-Sub1 background (Table 1), qDTY2.2 in a Samba Mahsuri background (Table 3), and qDTY6.1 + qDTY3.1 and Sub1 + qDTY6.2 + DTY3.1 in a TDK1-Sub1 background (Table 4), were observed to be lower yielders in each of the generations from F4 to F8. The significant high grain yield advantage of Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY1.2, Sub1 + qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.2, Sub1 + qDTY2.2 + qDTY12.1, and Sub1 + qDTY3.2 + qDTY2.3 + qDTY12.1 in an IR64-Sub1 background (Table 2) and of qDTY12.1 + qDTY3.1 and qDTY2.2 + qDTY3.1 in an MR219 background (Table 5) was consistent from the F4 to F7 generation. QTL classes Sub1 + qDTY1.2 + qDTY12.1, Sub1 + qDTY3.2 + qDTY2.3, and qDTY1.1 + qDTY2.2 + qDTY12.1 + Sub1 in an IR64-Sub1 background showed lower yield from F3 to subsequent generations (Table 2). The low grain yield performance of qDTY12.1 + qDTY2.2 and qDTY2.2 + qDTY3.1 + qDTY12.1 under RS drought stress in MR219 was maintained from the F4 to F7 generation (Table 5). None of the inferior QTL classes identified in F3 outperformed the identified superior QTL combination class or combination classes in any advanced generation under NS as well as under variable intensities of RS drought stress in different seasons/years across generations from F4 to F7/F8.

Cost effectiveness of the early generation selection

The genotyping cost for the whole population considering all QTL classes from F3 to F7/F8 ranged from USD 9225 to USD 21760 whereas the genotyping cost accounting for further advancement and screening (F4 to F7/F8) of only superior classes in F3 varied from USD 5730 to USD 8978 (Table 6). A genotyping cost savings of USD 12443, 3720, 14,780, 2273, and 6225 was observed in Swarna-Sub1, IR64-Sub1, Samba Mahsuri, TDK1-Sub1, and MR219 backgrounds, respectively, with a range of savings of USD 2273 to USD 14780 in all five backgrounds.

Table 6.

Comparison of genotyping cost (USD) considering advancement of all QTL classes versus advancement of only higher performing F3 generation QTL classes

| Background | Generation | Number of QTL classes | Population size | Cost (USD) | Total genotyping cost (USD) | Savings (USD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Based on all classes | Based on selected classes | Based on all classes | Based on selected classes | Based on all classes | Based on selected classes | ||||

| Swarna-Sub1 | F3 | 15 | 754 | 754 | 5655 | 5655 | 21,420 | 8978 | 12,443 |

| F4 | 15 | 754 | 106 | 5655 | 795 | ||||

| F5 | 10 | 432 | 106 | 3240 | 795 | ||||

| F6 | 10 | 432 | 106 | 3240 | 795 | ||||

| F7 | 6 | 432 | 108 | 3240 | 810 | ||||

| F8 | 5 | 52 | 17 | 390 | 127.50 | ||||

| IR64-Sub1 | F3 | 20 | 467 | 467 | 7005 | 7005 | 12,105 | 8385 | 3720 |

| F4 | 19 | 194 | 46 | 2910 | 690 | ||||

| F5 | 19 | 64 | 18 | 960 | 270 | ||||

| F6 | 13 | 64 | 18 | 960 | 270 | ||||

| F7 | 7 | 18 | 10 | 270 | 150 | ||||

| Samba Mahsuri | BC1F3 | 3 | 42 | 42 | 210 | 210 | 21,760 | 6980 | 14,780 |

| BC1F4 | 3 | 3000 | 640 | 15,000 | 3200 | ||||

| BC1F5 | 3 | 1200 | 640 | 6000 | 3200 | ||||

| BC1F6 | 3 | 70 | 44 | 350 | 220 | ||||

| BC1F7 | 2 | 20 | 15 | 100 | 75 | ||||

| BC1F8 | 2 | 20 | 15 | 100 | 75 | ||||

| TDK1-Sub1 | BC2F3 | 14 | 843 | 843 | 6323 | 6323 | 9225 | 6954 | 2272 |

| BC2F4 | 7 | 231 | 43 | 1733 | 323 | ||||

| BC2F5 | 7 | 48 | 14 | 360 | 105 | ||||

| BC2F6 | 7 | 48 | 14 | 360 | 105 | ||||

| BC2F7 | 5 | 60 | 13 | 450 | 98 | ||||

| MR219 | BC1F3 | 7 | 214 | 214 | 1605 | 1605 | 11,955 | 5730 | 6225 |

| BC1F4 | 7 | 620 | 240 | 4650 | 1800 | ||||

| BC1F5 | 7 | 620 | 240 | 4650 | 1800 | ||||

| BC1F6 | 7 | 70 | 35 | 525 | 262.50 | ||||

| BC1F7 | 7 | 70 | 35 | 525 | 262.50 | ||||

The genotyping cost was calculated considering five markers per QTL (one peak/near the peak, two right-hand-side flanking markers, and two left-hand-side flanking markers) and USD 0.50 per data point

The phenotyping cost for the whole population ranged from USD 29197 to USD 157455 whereas it was USD 20225 to USD 50507 in the case of selected classes (Table 7). A phenotyping cost savings of USD 60023, 8973, 10,963, 106,948, and 30,029 was observed in Swarna-Sub1, IR64-Sub1, Samba Mahsuri, TDK1-Sub1, and MR219 backgrounds, respectively, with phenotyping cost savings of USD 8973–106,948 in all five backgrounds. The genotyping and phenotyping cost and savings were high in Samba Mahsuri as the number of plant samples in the whole population set in the F4 generation was more than in the QTL class selected in F3 (DTY2.2 + DTY4.1) (Table 6). The cost savings was inversely proportional to the number of QTL combination classes identified as providing superior performance in F3.

Table 7.

Comparison of phenotyping cost (USD) considering advancement of all QTL classes versus advancement of only higher performing F3 generation QTL classes

| Background | Generation | Population size | Phenotyping cost (USD) | Total phenotyping cost (USD) | Savings (USD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Based on all classes | Based on selected classes | Based on all classes | Based on selected classes | Based on all classes | Based on selected classes | |||

| Swarna-Sub1 | F3 | 754 | 754 | 27,280 | 27,280 | 103,330 | 43,307 | 60,023 |

| F4 | 754 | 106 | 27,280 | 3835 | ||||

| F5 | 432 | 106 | 15,630 | 3835 | ||||

| F6 | 432 | 106 | 15,630 | 3835 | ||||

| F7 | 432 | 108 | 15,630 | 3907 | ||||

| F8 | 52 | 17 | 1881 | 615 | ||||

| IR64-Sub1 | F3 | 467 | 467 | 16,896 | 16,896 | 29,197 | 20,225 | 8973 |

| F4 | 194 | 46 | 7019 | 1664 | ||||

| F5 | 64 | 18 | 2316 | 651 | ||||

| F6 | 64 | 18 | 2316 | 651 | ||||

| F7 | 18 | 10 | 651 | 362 | ||||

| Samba Mahsuri | BC1F3 | 42 | 42 | 1520 | 1520 | 157,455 | 50,507 | 106,948 |

| BC1F4 | 3000 | 640 | 108,540 | 23,155 | ||||

| BC1F5 | 1200 | 640 | 43,416 | 23,155 | ||||

| BC1F6 | 70 | 44 | 2533 | 1592 | ||||

| BC1F7 | 20 | 15 | 724 | 543 | ||||

| BC1F8 | 20 | 15 | 724 | 543 | ||||

| TDK1-Sub1 | BC2F3 | 843 | 843 | 30,500 | 30,500 | 44,501 | 33,539 | 10,963 |

| BC2F4 | 231 | 43 | 8358 | 1556 | ||||

| BC2F5 | 48 | 14 | 1737 | 507 | ||||

| BC2F6 | 48 | 14 | 1737 | 507 | ||||

| BC2F7 | 60 | 13 | 2171 | 470 | ||||

| MR219 | BC1F3 | 214 | 214 | 7743 | 7743 | 57,671 | 27,642 | 30,029 |

| BC1F4 | 620 | 240 | 22,432 | 8683 | ||||

| BC1F5 | 620 | 240 | 22,432 | 8683 | ||||

| BC1F6 | 70 | 35 | 2533 | 1266 | ||||

| BC1F7 | 70 | 35 | 2533 | 1266 | ||||

The phenotyping cost of USD 36.18 per entry was calculated considering two replications and screening under NS and RS drought stress with plot size of 1.54 m2 (IRRI Standard drought screening costing)

Interaction among QTLs and with background

In our study, qDTY1.1 showed positive interactions with qDTY2.1, qDTY2.2, and qDTY3.1, whereas qDTY2.2 showed positive interactions with qDTY4.1, qDTY12.1, and qDTY3.1. qDTY3.1 showed positive interactions with qDTY1.1, qDTY2.2, qDTY12.1, qDTY6.1, and qDTY6.2 at least in the genetic backgrounds that we studied in the present experiment. Such information will be helpful to breeders in selecting QTL combinations in their MAB programs.

Discussion

Phenotypic evaluation of QTLs pyramided lines

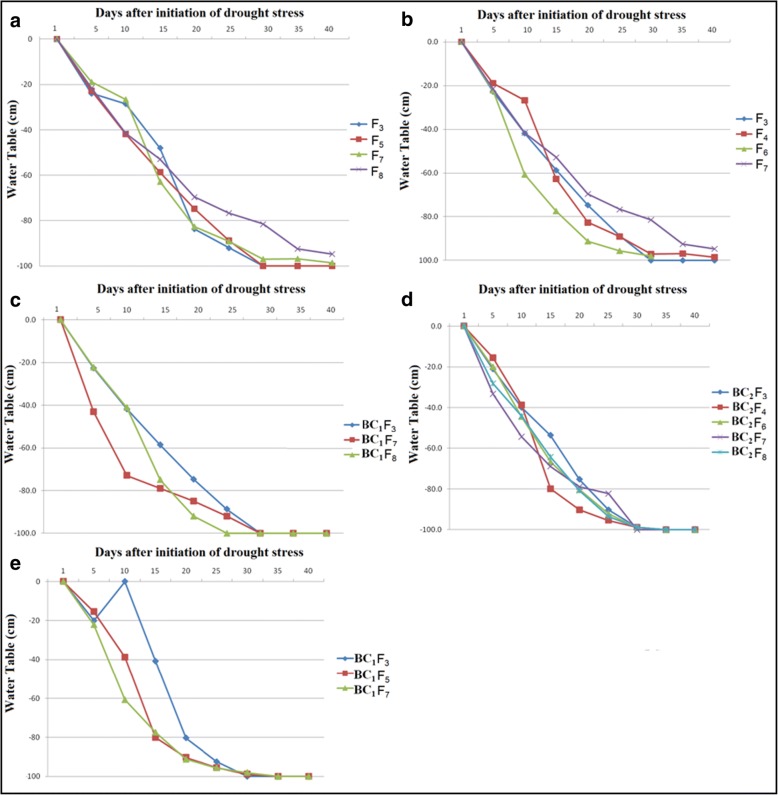

The yield reduction in RS drought stress experiments was 45, 77, 79, and 97% in F3, F5, F7, and F7 generations, respectively, in Swarna-Sub1 introgression lines as compared to the mean yield of the NS experiments. In IR64-Sub1, the yield reduction was 22, 96, 82, and 97% in F3, F4, F6, and F7 generations, respectively. In the Samba Mahsuri background, the mean yield reduction was 66, 98, and 98% in F3, F7, and F8 generations, respectively, in the RS drought stress experiment compared with NS experiments. A grain yield reduction of 68, 93, 98, and 96% was observed in F4, F6, F7, and F8 generations, respectively, under RS drought stress compared with NS in TDK1-Sub1 introgressed lines. In MR219 introgressed lines, the yield reduction under RS drought stress compared with NS was 88, 93, and 93% in F3, F5, and F7 generations, respectively. Accurate standardized phenotyping under RS drought stress assists breeders in rejecting inferior QTL classes in F3 itself and is the basis of success of the combined MAS breeding approach. It is evident from the yield reduction as well as the water table depths (Fig. 2a-e) that the stress level in RS drought stress experiments ranged from moderate to severe drought stress intensity at the reproductive stage in most of the cases. DTF of majority of pyramided lines was less than that of recipient lines under RS but not under NS. Some of the selected progenies showed early DTF than recipient under NS and this may have resulted from linkages of the drought QTLs with earliness (Vikram et al. 2016). Most of the progenies showed similar PHT as that of recipient cultivars under NS but higher PHT under RS because of their increased ability to produce biomass under RS (data not presented).

Fig. 2.

Soil water potential measured by parching water table level in experiments (a) Swarna-Sub1 pyramided lines with qDTY1.1, qDTY2.1, and qDTY3.1 in different generations; b IR64-Sub1 pyramided lines with qDTY1.1, qDTY1.2, qDTY2.2, qDTY2.3, qDTY3.2, and qDTY12.1 in different generations; c Samba Mahsuri pyramided lines with qDTY2.2 and qDTY4.1 in different generations; d TDK1-Sub1 pyramided lines with qDTY3.1, qDTY6.1, and qDTY6.2 in different generations; and (e) MR219 pyramided lines with qDTY2.2, qDTY3.1, and qDTY12.1 in different generations using polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipe

Selection of superior QTLs class in early generation

In a marker-assisted QTL introgression/pyramiding program, it would be very valuable to explore QTL combinations with high performance in early generations. The F2 generation is highly heterogeneous; therefore, screening of a large population size is essential to maximize the exploitation of genetic variation (Kahani and Hittalmani 2015). Sometimes, based on the availability of resources, fields for phenotyping, as well as capacity of breeding programs, breeders have to reduce the population size, which may lead to a loss of existing positive genetic variability in the population (Govindaraj et al. 2015). In the present study, the screening of a large-sized F3 population was carried out under control (NS) and RS drought stress conditions. The classification of the population in different classes based on QTL combinations in each generation (F3 to F7/F8) followed by class analysis to see the performance of each QTL class across generation advancement proved to be an effective approach in identifying best-bet QTL combination classes across five high-yielding genetic backgrounds. The performance of the genotypes in a particular QTL class was consistent from F3 to F7/F8 generations in all five studied background in the present study. The advancement of the classes with high mean grain yield performance in the F3 generation in addition to the MAB approach involving stepwise phenotyping and genotyping screening suggested this as being a cost/labor- and resource-effective breeding strategy. The lesser number of genotypes in advanced generations can be screened more precisely in a large plot size with more replications. The current cost-effective high-throughput phenotyping platform (Comar et al. 2012; Andrade-Sanchez et al. 2014; Sharma and Ritchie 2015; Bai et al. 2016) can be used for precise breeding and physiological studies considering the small population size. Even at the F3 level, some heterozygosity will be observed when more genes are involved in the introgression program. However, in our study, we did not observe any change in performance of QTL classes found superior in F3, indicating the F3 generation to be suitable to conduct class analysis and reject inferior classes.

Population size and validation of combined breeding strategy

In addition to the modern next-generation genotyping strategies (Barba et al. 2014; Rius et al. 2015; Dhanapal and Govindaraj 2015) and agricultural system models (Antle et al. 2016), several breeding strategies involving correlated traits as selection criteria in early generations (Senapati et al. 2009), grain yield (Kumar et al. 2014), secondary traits (Mhike et al. 2012), genetic variance, heritability (Almeida et al. 2013), path coefficient analysis, selection tolerance index (Dao et al. 2017), and yield index (Raman et al. 2012) have been suggested for use in breeding programs. The consistent performance of pyramided lines with specific QTL combinations across generations (F3 to F7/F8) in five backgrounds in the present study validates the potential of the suggested combined MAS breeding approach presented in the current study. The integration of accurate phenotyping and the selection of the best class representing the genetic variability of the whole population in early generations are critical steps for the practical implementation of this ultimate novel breeding strategy. Keeping a large F3 population size depending upon the number of genes/QTLs being introgressed and precise phenotyping to exploit the hidden potential of each genotype in each QTL class could maximize the potential output of each class in early generations. The most logical QTL-class performance-derived novel breeding strategy could be adopted to optimize the breeding efficiency of small-to moderate-sized breeding programs in rice breeding improvement programs. Further, the strategy could be equally useful to other crops in which major genes/QTLs determine the expression of traits and QTL x QTL or QTL x genetic background interactions have been identified.

We were able to understand the effectiveness of early generation selection in the marker-assisted introgression program for drought because the breeding program maintained systematic data for both genotyping and phenotyping conducted over the past six or more years. It was only after we successfully identified the best lines coming from each introgression program after successful multi-location evaluation that we realized that, as the breeding program will need to bring in more and more genes for multiple traits to address each of the new emerging climate-related challenges, modifications that allow plant breeders to make large-scale rejections in the early generation will become necessary. The effectiveness of the combined MAS strategy is evident from the result that, in none of the five cases were the superior QTL class combinations identified in F3 outperformed by inferior classes identified in F3 in any advanced generation under both NS and variable intensities of RS drought stress in different seasons/years across generations from F4 to F6/F7/F8.

Cost-effectiveness of combined breeding strategy

Breeding practices are challenged by being laborious, time consuming, and non-economical, requiring large land space and a large population size (Sandhu and Kumar 2017), being imprecise, and having unreliable phenotyping screening (Bhat et al. 2016); hence, an economical, fast, accurate, and efficient breeding selection system is required to increase grain yield potential and productivity (Khan et al. 2015). The cost-benefit balance (Bhat et al. 2016) must be considered in increasing genetic gain in the new era of modern science. The use of the class analysis approach in the F3 generation followed by advancing only higher performing classes reported a genotyping cost savings of 25–68% and phenotyping cost savings of 25–68% compared with the traditional molecular marker breeding approach (Table 6). Although the cost-benefit of the combined MAS breeding strategy will always be inversely proportional to the number of superior QTL class combinations identified for advancement in F3 and subsequent generations, the cost savings will increase as the number of genes included in the introgression program increases because of the rejection of a larger proportion of the total population early in the F3 generation. This procedure will save time, labor, resources, and space and will allow breeders to focus only on germplasm with higher value. This will reduce the population size for phenotypic and genotypic selection in advanced generations compared with earlier marker-assisted breeding strategies (Price 2006; McNally et al. 2009; Yadaw et al. 2013; Sandhu et al. 2014; Brachi et al. 2012; Begum et al. 2015). It will be practical and realistic only if the phenotyping, genotyping, and class analysis in early generations are accurate.

Interactions among QTLs and with background

The QTLs for grain yield under drought have shown QTL x QTL (Sandhu et al. 2018) as well as QTL x genetic background interactions (Dixit et al. 2012a, b; Sandhu et al. 2018). Many such interactions that may occur between QTL x QTL and QTL x genetic background are unknown. Such positive/negative interactions affecting grain yield under normal or RS situation can be captured through approach that combines selection based on phenotyping and genotyping in the early generations. The current study clearly demonstrated the success of selection based on combining phenotyping and genotyping in identifying better progenies in early generation thereby reducing the number of progenies to be advanced. Number of plants to be generated and evaluated in the early generations will depend upon the number of QTLs/genes to be introgressed together, size of introgressed QTLs region as well as availability of closely linked markers for each of the QTLs. The QTLs for grain yield under drought have shown undesirable linkages with low yield potential, very early maturity duration, tall plant height (Vikram et al. 2015). At IRRI, studies were undertaken to break the undesirable linkages of QTLs with tall plant height, very early maturity duration and low yield potential (Vikram et al. 2015). Such improved lines were used in the MAS introgression program. The drought tolerant donors N22, Dular, Apo, Way Rarem, Kali Aus, Aday Sel that are source of identified QTLs do not possess good grain quality. Even though, we did not study the linkage of qDTYs with grain quality, the introgressed lines released as varieties in IR64, Swarna backgrounds in India and Nepal did not reveal any adverse effect on grain quality. The yield superiority of lines with two or more QTLs under both NS and RS drought stress over the five high-yielding backgrounds clearly indicated that qDTY QTLs identified at IRRI are free from undesirable linkage drag and can be successfully used in MAB programs targeting yield improvement under RS drought stress. Further, in Swarna-Sub1, IR64-Sub1, and TDK-Sub1, the highest yielding classes identified were the classes possessing both Sub1 and combinations of the drought QTLs. The yield superiority of such classes across these three backgrounds over all the generations clearly indicated that tolerance of submergence and drought can be effectively combined even though they are governed by two different physiological mechanisms. In the QTL study undertaken at IRRI, qDTY1.1 showed a significant mean yield advantage in MTU1010 and IR64 (Sandhu et al. 2015); qDTY2.2 in Pusa Basmati 1460, MTU1010, and IR64 (Venuprasad et al. 2007; Swamy et al. 2013; Sandhu et al. 2013; Sandhu et al. 2014); qDTY2.3 in Vandana and IR64 (Dixit et al. 2012b; Sandhu et al. 2014); qDTY3.2 in Sabitri (Yadaw et al. 2013); qDTY6.1 in IR72 (Venuprasad et al. 2009); and qDTY12.1 in Vandana (Bernier et al. 2007), Sabitri (Mishra et al. 2013), Kalinga, and Anjali backgrounds. Similar interaction of qDTY2.3 and qDTY3.2 with qDTY12.1 in a Vandana background (Dixit et al. 2012b); qDTY2.2 and qDTY3.1 with qDTY12.1 in an MRQ74 background (Shamsudin et al. 2016); and qDTY2.2 + qDTY4.1 in an IR64 background (Swamy et al. 2013) was observed. The interaction of identified QTLs with other QTLs in more than two backgrounds supports the usefulness of such QTL classes in MAS. In all five of these cases, through genotyping and phenotyping we were able to identify QTL class combinations with positive interactions and higher yield. As more data are generated across different backgrounds and interactions are established, breeders will have the ability to identify and forward only selected classes without phenotyping from F3 onward.

Pyramiding of multiple QTLs associated with multiple traits

With the identification of gene-based/closely linked markers for different biotic stresses (bacterial blight, blast, brown planthopper, gall midge) and abiotic stresses (submergence, drought, phosphorus deficiency, cold, anaerobic germination, high temperature), the MAB program is moving forward to introgress more genes/QTLs to develop climate-resilient and better rice varieties. For effective tolerance to develop a variety combining tolerance of biotic and abiotic stresses – bacterial leaf blight (three genes – xa5, xa13, Xa21), blast (two – pi2, pi9), brown planthopper (two – BPH3, BPH17), gall midge (two – Gm4, Gm8), drought (three –qDTY1.1, qDTY2.1, qDTY3.1), and submergence (Sub1) – researchers will need introgression and the combination of 13–15 genes/QTLs in gene combinations mentioned here or in other combinations depending upon the prevalence of a pathotype/biotype in different regions. The number of genes to be introgressed is likely to increase as exposure of rice to high temperature at the reproductive stage will probably increase in most rice-growing regions. The introgression of 10–15 genes will not only require a larger initial population in F2 and F3 but will also lead to increased positive/negative interactions between genes/QTLs. With capacity development, as more and more breeding programs adopt marker-assisted introgression of more genes, the combined MAS strategy will be of great help to plant breeders in reducing the number of plants that they should handle in each generation and make their breeding program cost-effective.

Conclusions

The selection of QTL classes with a high mean yield performance and positive interactions among loci and with background in the early generation and consistent performance of QTL classes in subsequent generations across five backgrounds supports the effectiveness of a combined MAS breeding strategy. The challenge ahead is the appropriate estimation of the precise population size to be used for QTL class analysis in the early F3 generation to maintain genetic variability as the number of genes/QTLs increases further. Integration of a cost-effective, efficient, designed, statistics-led early generation superior QTL class selection-based breeding strategy with new-era genomics such as genotyping by sequencing and genomic selection could be an important breakthrough to build up a scientific next-generation breeding program.

Methods

The study was conducted at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Philippines, to introgress QTLs for grain yield under RS drought stress in the background of improved high- yielding widely grown but drought-susceptible varieties from India (Swarna, IR64, Samba Mahsuri), Lao PDR (TDK1), and Malaysia (MR219).

Five sets of introgressed populations were used:

Swarna-Sub1 pyramided lines with qDTY1.1, qDTY2.1, and qDTY3.1

IR64-Sub1 pyramided lines with qDTY1.1, qDTY1.2, qDTY2.2, qDTY2.3, qDTY3.2, and qDTY12.1

Samba Mahsuri pyramided lines with qDTY2.2 and qDTY4.1

TDK1-Sub1 pyramided lines with qDTY3.1, qDTY6.1, and qDTY6.2

MR219 pyramided lines with qDTY2.2, qDTY3.1, and qDTY12.1

Three steps were employed for the development of a cost-effective, reliable, and resource-efficient combined MAS breeding strategy: (1) grain yield and genotypic data across F3, F4, F5, F6, F7, and F8/fixed lines for all five sets were compiled; (2) class analysis was carried out to develop a combined MAS breeding strategy; and (3) the performance of the superior classes was monitored across advanced generations to validate the combined MAS breeding strategy.

The screening of all five population sets was carried out under NS control and RS drought stress conditions. For the NS experiments, 5-cm water depth level was maintained throughout the rice growing season until physiological maturity. For the screening under RS drought stress, irrigation was stopped at 30 days after transplanting (DAT). The last irrigation was provided at 24 DAT and there was no standing water in the field when drought was initiated at 30 DAT. The stress cycle was continued until severe stress symptoms were observed. Monitoring of soil water potential was carried out by placing perforated PVC pipes at 100-cm soil depth in the field in a zig-zag manner. After the initiation of stress, the water table level was recorded daily. When approximately 70% of the lines exhibited severe leaf rolling or wilting, one life-saving irrigation with a sprinkler system was provided. Then, a second cycle of the stress was initiated. The water table level was measured from all the pipes until the rice crop reached 50% maturity.

Molecular marker work was carried out following the procedure as described in Sandhu et al. (2014). For genotyping, a total of 754, 754, 432, 432, 432, and 52 plants were phenotyped and genotyped in F3 (NS, RS), F4 (NS), F5 (NS, RS), F6 (NS, RS), F7 (NS), and F8 (NS, RS) generations, respectively, in a Swarna-Sub1 background. In the IR64-Sub1 background, 467, 194, 64, 64, and 18 plants were phenotyped and genotyped in F3 (NS, RS), F4 (NS, RS), F5 (NS), F6 (NS, RS), and F7 (NS, RS) generations, respectively. In the Samba Mahsuri background, a total of 42, 3000, 1200, 70, 20 and 20 plants were phenotyped and genotyped in BC1F3 (NS, RS), BC1F4 (NS, RS), BC1F5 (NS), BC1F6 (NS), BC1F7 (NS, RS), and BC1F8 (NS, RS) generations respectively. In the TDK-1Sub1 background, 843, 231, 48, 48, 60 and 60 plants were phenotyped and genotyped in BC2F3 (RS), BC2F4 (NS, RS), BC2F5 (NS), BC2F6 (NS, RS), BC2F7 (NS, RS), and BC2F8 (NS, RS) generations, respectively. A total of 214, 620, 620, 70, and 70 plants were phenotyped and genotyped in BC1F3 (NS, RS), BC1F4 (NS), BC1F5 (NS, RS), BC1F6 (NS, RS), and BC1F7 (NS, RS) generations, respectively, in the MR219 background. Data on plant height, days to 50% flowering, and grain yield were recorded following the procedure of Venuprasad et al. (2009). The detailed description on QTLs and markers used in the present study in each background is presented in Additional file 1: Table S1. The general schematic scheme followed for QTL introgression and pyramiding program, phenotyping and genotyping screening is shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Analytical approach to reveal a combined MAS breeding strategy

The grain yield data from F3, F4, F5, F6, F7, and F8 generations across seasons and NS (control) and RS drought stress conditions for all five sets of pyramided populations were compiled and categorized into classes based on the genotypic QTL information. Class analysis using SAS v9.2 was attempted to see the mean grain yield performance of QTL classes across generation advancement.

Genotyping and phenotyping cost calculation

The phenotyping cost of USD 36.18 per entry (two replications, screening under NS and RS drought stress with plot size of 1.54 m2) (IRRI Standard drought screening costing) including the cost of land preparation, land rental, irrigation, electricity, field layout, seeding, transplanting, maintenance cost, resource input (fertilizer), pesticides, herbicides, field supplies, harvesting, threshing, drying, data collection, and labor was used to calculate the cost savings for phenotyping. The genotyping cost was calculated for the whole population across successive generations (F3 to F7/F8) and compared with the genotyping cost (F3 to F7/F8) considering only the QTL classes that performed better in F3. The genotyping cost was calculated considering five markers per QTL (one peak/near the peak, two right-hand-side flanking markers, and two left-hand-side flanking markers) using USD 0.50 per data point (Xu et al. 2002; Xu 2010).

Statistical analysis

Mean comparison of QTL genotype classes

Hypothesis about no differences among phenotype means of QTL genotype classes for each background under NS and RS drought stress in each season was performed in SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute Inc. 2009) using the following linear model.

where μ represents the population mean, rk represents the effect of the kth replicate, b(r)kl is the effect of the lth block within the kth replicate, qi corresponds to the effect of the ith QTL, g(q)ij symbolizes the effect of the jth genotype nested within the ith QTL, and eijkl corresponds to the error (Knapp 2002). The effects of QTL class and the genotypes within QTL were considered fixed and the replicates and blocks within replicates were set to random.

Additional file

Table S1. QTLs and markers information’s in marker assisted introgression program in different backgrounds. Figure S1. General schematic scheme for QTL introgression and pyramiding program, phenotyping and genotyping screening. In case of Swarna-Sub1 and IR64-Sub1 no backcross was attempted. In case of Samba Mahsuri and MR219, one backcross was attempted. In case of TDK1-Sub1 two backcross was attempted. (DOCX 269 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Ma. Teresa Sta. Cruz and Paul Maturan for the management of field experiments, Jocelyn Guevarra and RuthErica Carpio for assistance with seed preparations.

Funding

This study was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) and the Generation Challenge Program (GCP). The authors thank BMGF and GCP for financial support for the study.

Availability of data and materials

The relevant supplementary data has been provided with the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

AK conceived the idea of the study and was involved in critical revision and final approval of the version to be published; NS was involved in conducting the experiments, analysis, interpretation of the data, and drafting the manuscript; SD, SY, BPMS, and NAAS were involved in developing populations and conducting the experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The manuscript has been approved by all authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12284-018-0227-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Arvind Kumar, Email: a.kumar@irri.org.

Nitika Sandhu, Email: n.sandhu@irri.org.

Shalabh Dixit, Email: s.dixit@irri.org.

Shailesh Yadav, Email: shailesh.yadav@irri.org.

B. P. M. Swamy, Email: m.swamy@irri.org

Noraziyah Abd Aziz Shamsudin, Email: nora_aziz@ukm.edu.my.

References

- Almeida GD, Makumbi D, Magorokosho C, Nair S, Borém A, Ribaut JM, Bänziger M, Prasanna BM, Crossa J, Babu R. QTL mapping in three tropical maize populations reveals a set of constitutive and adaptive genomic regions for drought tolerance. Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126(3):583–600. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-2003-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade-Sanchez P, Gore MA, Heun JT, Thorp KR, Carmo-Silva AE, French AN, Salvucci ME, White JW. Development and evaluation of a field-based high-throughput phenotyping platform. Funct Plant Biol. 2014;41(1):68–79. doi: 10.1071/FP13126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antle JM, Jones JW, Rosenzweig CE. Next generation agricultural system data models and knowledge products: introduction. Agric Syst. 2016;AGSY-02173:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baenziger PS, Beecher B, Graybosch RA, Ibrahim AMH, Baltensperger DD, Nelson LA. Registration of ‘NEO1643’ wheat. J Plant Registr. 2008;2:36–42. doi: 10.3198/jpr2007.06.0327crc. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Ge Y, Hussain W, Baenziger PS, Graef G. A multi-sensor system for high throughput field phenotyping in soybean and wheat breeding. Comput Electron Agric. 2016;128:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2016.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barba M, Czosnek H, Hadidi A. Historical perspective development and applications of next-generation sequencing in plant virology. Viruses. 2014;6:106–136. doi: 10.3390/v6010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum H, Spindel JE, Lalusin A, Borromeo T, Gregorio G, Hernandez J. Genome-wide association mapping for yield and other agronomic traits in an elite breeding population of tropical rice (Oryza sativa) PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D, Reynolds M, Mullan D, Izanloo A, Kuchel H, Langridge P, Schnurbusch T. Detection of two major grain yield QTL in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L) under heat drought and high yield potential environments. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125(7):1473–1485. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1927-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier J, Kumar A, Ramaiah V, Spaner D, Atlin G. A large-effect QTL for grain yield under reproductive-stage drought stress in upland rice. Crop Sci. 2007;47(2):507–516. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2006.07.0495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat JA, Ali S, Salgotra RK, Mir ZA, Dutta S, Jadon V, Tyagi A, Mushtaq M, Jain N, Singh PK, Singh GP. Genomic selection in the era of next generation sequencing for complex traits in plant breeding. Front Genet. 2016;7:221. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2016.00221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar-Mathur P, Vadezm V, Sharmam KK. Transgenic approaches for abiotic stress tolerance in plants: retrospect and prospects. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27:411–424. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscarini F, Cozzi P, Casella L, Riccardi P, Vattari A, Orasen G, Perrini R, Tacconi G, Tondelli A, Biselli C, Cattivelli L. Genome-wide association study for traits related to plant and grain morphology, and root architecture in temperate rice accessions. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachi B, Aimé C, Glorieux C, Cuguen J, Roux F. Adaptive value of phenological traits in stressful environments: predictions based on seed production and laboratory natural selection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breseghello F, Sorrells ME. Association analysis as a strategy for improvement of quantitative traits in plants. Crop Sci. 2006;46:1323–1330. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2005.09-0305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brick MA, Ogg JB, Singh SP, Schwartz HF, Johnson JJ, Pastor-Corrales MA. Registration of drought-tolerant rust-resistant high-yielding pinto bean germplasm line CO46348. J Plant Registr. 2008;2:120–134. doi: 10.3198/jpr2007.06.0359crg. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comar A, Burger P, de Solan B, Baret F, Daumard F, Hanocq JF. A semi-automatic system for high throughput phenotyping wheat cultivars in-field conditions: description and first results. Funct Plant Biol. 2012;39(11):914–924. doi: 10.1071/FP12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert JL, Somers DJ, Brûlé-Babel AL, Brown PD, Crow GH. Molecular mapping of quantitative trait loci for yield and yield components in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L) Theor Appl Genet. 2008;117(4):595–608. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0804-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dao SJ, Traore EVS, Gracen V, Eric YD. Selection of drought tolerant maize hybrids using path coefficient analysis and selection index. Pakistan J Biol Sci. 2017;20:132–139. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2017.132.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das G, Rao GJN. Molecular marker assisted gene stacking for biotic and abiotic stress resistance genes in an elite rice cultivar. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:698. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanapal AP, Govindaraj M. Unlimited thirst for genome sequencing data interpretation and database usage in genomic era: the road towards fast-track crop plant improvement. Genet Res Internat. 2015;2015:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2015/684321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit S, Singh A, Kumar A. Rice breeding for high grain yield under drought: a strategic solution to a complex problem. Int J Agron Article ID. 2014;863683:15. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit S, Swamy BM, Vikram P, Ahmed HU, Cruz MS, Amante M, Atri D, Leung H, Kumar A. Fine mapping of QTLs for rice grain yield under drought reveals sub-QTLs conferring a response to variable drought severities. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125(1):155–169. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1823-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit S, Swamy BM, Vikram P, Bernier J, Cruz MS, Amante M, Atri D, Kumar A. Increased drought tolerance and wider adaptability of qDTY12.1 conferred by its interaction with qDTY2.3 and qDTY3.2. Mol Breed. 2012;30:1767–1779. doi: 10.1007/s11032-012-9760-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elangovan M, Rai R, Dholakia BB, Lagu MD, Tiwari R, Gupta RK, Rao VS, Röder MS, Gupta VS. Molecular genetic mapping of quantitative trait loci associated with loaf volume in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum) J Cereal Sci. 2008;47(3):587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2007.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire KH, Quiatchon LA, Vikram P, Swamy BM, Dixit S, Ahmed H, Hernandez JE, Borromeo TH, Kumar A. Identification and mapping of a QTL (qDTY1.1) with a consistent effect on grain yield under drought. Field Crops Res. 2012;131:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2012.02.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Govindaraj M, Vetriventhan M, Srinivasan M. Importance of genetic diversity assessment in crop plants and its recent advances: an overview of its analytical perspectives. Genet Res Int. 2015;2015:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2015/431487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari B, Sayed-Tabatabaei BE, Saeidi G, Kearsey M, Suenaga K. Mapping QTL for grain yield yield components and spike features in a doubled haploid population of bread wheat. Genome. 2011;54(6):517–527. doi: 10.1139/g11-017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Sang T, Zhao Q, Feng Q, Zhao Y, Li C, Zhu C, Lu T, Zhang Z, Li M, Fan D. Genome-wide association studies of 14 agronomic traits in rice landraces. Nat Genet. 2010;42(11):961–967. doi: 10.1038/ng.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jairin J, Teangdeerith S, Leelagud P, Kothcharerk J, Sansen K, Yi M, Vanavichit A, Toojinda T. Development of rice introgression lines with brown planthopper resistance and KDML105 grain quality characteristics through marker-assisted selection. Field Crops Res. 2009;110(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2008.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahani F, Hittalmani S. Genetic analysis and traits association in F2 intervarietal populations in rice under aerobic condition Rice Res: Open Access Oct 25. 2015. p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MH, Dar ZA, Dar SA. Breeding strategies for improving rice yield: a review. Agric Sci. 2015;6(5):467. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp G. Variance estimation in the error components regression model. Commun Stat Theor Met. 2002;31:1499–1514. doi: 10.1081/STA-120013008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kottapalli KR, Narasu ML, Jena KK. Effective strategy for pyramiding three bacterial blight resistance genes into fine grain rice cultivar Samba Mahsuri using sequence tagged site markers. Biotechnol Lett. 2010;32:989–996. doi: 10.1007/s10529-010-0249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Dixit S, Ram T, Yadaw RB, Mishra KK, Mandal NP. Breeding high-yielding drought-tolerant rice: genetic variations and conventional and molecular approaches. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:6265–6278. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally KL, Childs KL, Bohnert R, Davidson RM, Zhao K, Ulat VJ, Zeller G, Clark RM, Hoen DR, Bureau TE, Stokowski R. Genomewide SNP variation reveals relationships among landraces and modern varieties of rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(30):12273–12278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900992106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhike X, Okori P, Magorokosho C, Ndlela T. Validation of the use of secondary traits and selection indices for drought tolerance in tropical maize (Zea mays L) African J Plant Sci. 2012;6(2):96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Miah G, Rafii MY, Ismail MR, Puteh AB, Rahim HA, Latif MA. Marker-assisted introgression of broad-spectrum blast resistance genes into the cultivated MR219 rice variety. J Sci Food Agric. 2016;97(9):2810–2818. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra KK, Vikram P, Yadaw RB, Swamy BM, Dixit S, Cruz MTS, Maturan P, Marker S, Kumar A. qDTY12.1: a locus with a consistent effect on grain yield under drought in rice. BMC Genet. 2013;14(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-14-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal S, Rutkoski JE, Velu G, Singh PK, Crespo-Herrera LA, Guzmán C, Bhavani S, Lan C, He X, Singh RP (2016) Harnessing diversity in wheat to enhance grain yield climate resilience disease and insect pest resistance and nutrition through conventional and modern breeding approaches. Front Plant Sci 7(991):1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Obert DE, Evans CP, Wesenberg DM, Windes JM, Erickson CA, Jackson EW. Registration of ‘Lenetah’ spring barley. J Plant Registr. 2008;2:85–97. doi: 10.3198/jpr2008.01.0021crc. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Price AH. Believe it or not QTLs are accurate! Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:213–216. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman A, Verulkar S, Mandal N, Variar M, Shukla V, Dwivedi J, Singh B, Singh O, Swain P, Mall A, Robin S. Drought yield index to select high yielding rice lines under different drought stress severities. Rice. 2012;5(1):31. doi: 10.1186/1939-8433-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif JC, Hallauer AR, Melchinger AE. Heterosis and heterotic patterns in maize. Maydica. 2005;50:215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Rius M, Bourne S, Hornsby HG, Chapman MA. Applications of next-generation sequencing to the study of biological invasions. Current Zool. 2015;61(3):488–504. doi: 10.1093/czoolo/61.3.488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu N, Dixit S, Swamy BM, Vikram P, Venkateshwarlu C, Catolos M, Kumar A. Positive interactions of major-effect QTLs with genetic background that enhances rice yield under drought. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1626. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20116-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu N, Jain S, Kumar A, Mehla BS, Jain R. Genetic variation linkage mapping of QTL and correlation studies for yield root and agronomic traits for aerobic adaptation. BMC Genet. 2013;14:104–119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-14-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu N, Kumar A. Bridging the rice yield gaps under drought: QTLs genes and their use in breeding programs. Agronomy. 2017;7(2):27. doi: 10.3390/agronomy7020027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu N, Singh A, Dixit S, Cruz MTS, Maturan PC, Jain RK, Kumar A. Identification and mapping of stable QTL with main and epistasis effect on rice grain yield under upland drought stress. BMC Genet. 2014;15(1):63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-15-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu N, Torres RO, Cruz MTS, Maturan PC, Jain R, Kumar A, Henry A (2015) Traits and QTLs for development of dry direct-seeded rainfed rice varieties. J Exp Bot 66(1):225–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Senapati BK, Pal S, Roy S, De DK, Pal S. Selection criteria for high yield in early segregating generation of rice (Oryza sativa L) crosses. J Crop Weed. 2009;5:36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Septiningsih EM, Pamplona AM, Sanchez DL, Neeraja CN, Vergara GV, Heuer S, Ismail AM, Mackill DJ. Development of submergence-tolerant rice cultivars: the Sub1 locus and beyond. Ann Bot. 2009;103(2):151–160. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsudin NAA, Swamy BM, Ratnam W, Cruz MTS, Sandhu N, Raman AK, Kumar A. Pyramiding of drought yield QTLs into a high quality Malaysian rice cultivar MRQ74 improves yield under reproductive stage drought. Rice. 2016;9:21. doi: 10.1186/s12284-016-0093-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma B, Ritchie GL. High-throughput phenotyping of cotton in multiple irrigation environments. Crop Sci. 2015;55(2):958–969. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2014.04.0310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shull GH. What is “heterosis”? Genetics. 1948;33:439–446. doi: 10.1093/genetics/33.5.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AK, Gopalakrishnan S, Singh VP. Marker assisted selection: a paradigm shift in basmati breeding. Indian J Genet. 2011;71(2):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Singh RP, Rajaram S, Miranda A, Huerta-Espino J, Autrique E. Comparison of two crossing and four selection schemes for yield traits and slow rusting resistance to leaf rust in wheat. Euphytica. 1998;100:35–43. doi: 10.1023/A:1018391519757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Sidhu JS, Huang N, Vikal Y, Li Z, Brar DS. Pyramiding three bacterial blight resistance genes (xa5 xa13 and Xa21) using marker-assisted selection into indica rice cultivar PR106. Theor Appl Genet. 2001;102:1011–1015. doi: 10.1007/s001220000495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swamy BPM, Ahmed HU, Henry A, Mauleon R, Dixit S, Vikram P, Tilatto R, Verulkar SB, Perraju P, Mandal NP, Variar M, Robin S. Genetic physiological and gene expression analyses reveal that multiple QTL enhance yield of rice mega-variety IR64 under drought. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venuprasad R, Bool ME, Quiatchon L, Sta Cruz MT, Amante M, Atlin GN. A large effect QTL for rice grain yield under upland drought stress on chromosome 1. Mol Breed. 2012;30:535–547. doi: 10.1007/s11032-011-9642-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venuprasad R, Dalid CO, Del Valle M, Zhao D, Espiritu M, Cruz MTS, Amante M, Kumar A, Atlin GN. Identification and characterization of large-effect quantitative trait loci for grain yield under lowland drought stress in rice using bulk-segregant analysis. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;120(1):177–190. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venuprasad R, Lafitte HR, Atlin GN. Response to direct selection for grain yield under drought stress in rice. Crop Sci. 2007;47:285–293. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2006.03.0181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vikram P, Swamy BM, Dixit S, Ahmed HU, Cruz MTS, Singh AK, Kumar A. qDTY1.1 a major QTL for rice grain yield under reproductive-stage drought stress with a consistent effect in multiple elite genetic backgrounds. BMC Genet. 2011;12(1):89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-12-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikram P, Swamy BM, Dixit S, Trinidad J, Cruz MTS, Maturan PC, Amante M, Kumar A. Linkages and interactions analysis of major effect drought grain yield QTLs in rice. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikram P, Swamy BPM, Dixit S, Singh R, Singh BP, Miro B, Kohli A, Henry A, Singh NK, Kumar A. qDTY1.1 drought susceptibility of modern rice varieties: an effect of linkage of drought tolerance with undesirable traits. Nat Sci Rep. 2015;5:14799. doi: 10.1038/srep14799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volante A, Desiderio F, Tondelli A, Perrini R, Orasen G, Biselli C, Riccardi P, Vattari A, Cavalluzzo D, Urso S, Ben Hassen M. Genome-wide analysis of japonica rice performance under limited water and permanent flooding conditions. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1862. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Cheng J, Chen Z, Huang J, Bao Y, Wang J, Zhang H. Identification of QTL with main epistatic and QTL×environment interaction effects for salt tolerance in rice seedlings under different salinity conditions. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125:807–815. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1873-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xinglai P, Sangang X, Qiannying P, Yinhong S. Registration of ‘Jinmai 50’ wheat. Crop Sci. 2006;46:983–995. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2005.0217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y. Molecular plant breeding CABI Publishing. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Crouch JH. Marker-assisted selection in plant breeding: from publications to practice. Crop Sci. 2008;48:391–407. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2007.04.0191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Lobos KB, Clare KM. Development of SSR markers for rice molecular breeding In: Proceedings of Twenty-Ninth Rice Technical Working Group Meeting 24–27 February 2002 Little Rock Arkansas Rice Technical Working Group Little Rock Arkansas. 2002. p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Xue D, Huang Y, Zhang X, Wei K, Westcott S, Li C, Chen M, Zhang G, Lance R. Identification of QTLs associated with salinity tolerance at late growth stage in barley. Euphytica. 2009;169(2):187–196. doi: 10.1007/s10681-009-9919-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yadaw RB, Dixit S, Raman A, Mishra KK, Vikram P, Swamy BM, Cruz MTS, Maturan PT, Pandey M, Kumar A. A QTL for high grain yield under lowland drought in the background of popular rice variety Sabitri from Nepal. Field Crops Res. 2013;144:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2013.01.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Vanderbeld B, Wan J, Huang Y. Narrowing down the targets: towards successful genetic engineering of drought tolerant crops. Mol Plant. 2010;3:469–490. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. QTLs and markers information’s in marker assisted introgression program in different backgrounds. Figure S1. General schematic scheme for QTL introgression and pyramiding program, phenotyping and genotyping screening. In case of Swarna-Sub1 and IR64-Sub1 no backcross was attempted. In case of Samba Mahsuri and MR219, one backcross was attempted. In case of TDK1-Sub1 two backcross was attempted. (DOCX 269 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The relevant supplementary data has been provided with the manuscript.