Abstract

Background

The developmental propensity model of antisocial behavior posits that several dispositional characteristics of children transact with the environment to influence the likelihood of learning antisocial behavior across development. Specifically, greater dispositional negative emotionality, greater daring, and lower prosociality—operationally, the inverse of callousness— and lower cognitive abilities are each predicted to increase risk for developing antisocial behavior.

Methods

Prospective tests of key predictions derived from the model were conducted in a high-risk sample of 499 twins who were assessed on dispositions at 10–17 years of age and assessed for antisocial personality disorder (APD) symptoms at 22–31 years of age. Predictions were tested separately for parent and youth informants on the dispositions using multiple regressions that adjusted for oversampling, nonresponse, and clustering within twin pairs, controlling demographic factors and time since the first assessment.

Results

Consistent with predictions, greater numbers of APD symptoms in adulthood were independently predicted over a 10–15 year span by higher youth ratings on negative emotionality and daring and lower youth ratings on prosociality, and by parent ratings of greater negative emotionality and lower prosociality. A measure of working memory did not predict APD symptoms.

Conclusions

These findings support future research on the role of these dispositions in the development of antisocial behavior.

Keywords: developmental propensity model, prosociality, negative emotionality, daring, antisocial personality

Antisocial behavior has profound consequences for the wellbeing of victims and perpetrators alike (Piquero, Shepherd, Shepherd, & Farrington, 2011). We have presented a developmental propensity model of the origins of antisocial behavior in which individual differences in several aspects of cognitive ability and three dimensions of socioemotional dispositions influence the likelihood of learning antisocial behavior through transactions with the social environment (Sameroff & MacKenzie, 2003) from early childhood on (Lahey & Waldman, 2005, 2012; Lahey, Waldman, & McBurnett, 1999). In this model, antisocial behavior is learned through a process of shaping, differential reinforcement, and modeling of antisocial behavior (Bandura, 1969; Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989). Children vary in their likelihood of learning antisocial behavior both because of the nature of their social learning environments and individual differences in their predisposing characteristics that make them more or less likely to learn antisocial behavior. These dispositions are hypothesized to (1) evoke and select the child into different social environments, and (2) influence how different children respond to the same environments.

The developmental propensity model addresses four dimensions of child behavior found to predict future antisocial behavior in a literature review—prosociality, negative emotionality, daring, and low cognitive abilities (Lahey & Waldman, 2003, 2005, 2012). Children high in negative emotionality respond frequently and intensely to frustrations and threats with intense negative emotions. Such responses are hypothesized to provide the ‘raw material’ from which oppositional and aggressive behaviors are shaped. Furthermore, negative emotionality evokes aversive interchanges with others that decrease opportunities for adaptive socialization of child behavior. For example, children’s angry behaviors interfere with the development of adaptive friendships and evoke coercive exchanges that result in adults backing down from requests, reinforcing child noncompliance (Snyder, Reid, & Patterson, 2003). Similarly, negative emotional responses to provocations (e.g., another child playing with a toy that the child wants) lead peers to defer, reinforcing the antisocial behavior. The net result is that negative emotionality promotes the learning of antisocial behavior through negative and positive reinforcement.

Individual differences in the dispositions of prosociality and daring are hypothesized to influence the social learning of antisocial behavior both by evoking social responses and by influencing the affective valence of stimuli. That is, for children who differ in prosociality and daring, the same situations and consequences of behavior can be either attractive and positively reinforcing or unattractive and punishing. Prosociality refers to a tendency to care about the welfare of others, attempt to please them, and experience of guilt over misbehaviors. In terms of the items used to operationalize both constructs, prosociality is the inverse of callousness (Frick, Ray, Thornton, & Kahn, 2014; Lahey, 2014; Waldman et al., 2011). Children who are high on dispositional prosociality evoke mostly positive social behaviors from adults and peers, but if they behave in ways that upset others, the natural consequences of their behaviors are punishing—guilt inducing—reducing the likelihood of future misbehavior. Furthermore, children high in prosociality are hypothesized to be more responsive to social rewards, fostering the social reinforcement of adaptive behavior (Lahey & Waldman, 2012). In contrast, children who are low in prosociality are less motivated to do what others ask of them, evoking controlling and restrictive responses from adults. Furthermore, children low in prosociality find the social consequences of their misbehaviors to be neutral or even reinforcing. For example, taking another’s property would result in tangible positive reinforcement, with little offsetting guilt. Thus, antisocial behavior is self-reinforcing in children who are low in prosociality (Frick & Viding, 2009). Children high in daring are not harm avoidant and find intense and risky situations to be attractive and rewarding. Thus, the rough-and-tumble of fighting, the stimulation of vandalism, and the risk of being caught when shoplifting are attractive and positively reinforcing to daring children, whereas they are punishing to less daring children. In addition, multiple aspects of lower cognitive ability predispose children to antisocial behavior, including both language deficits (Keenan & Shaw, 2003; Lahey, D'Onofrio, Van Hulle, & Rathouz, 2014) and deficient executive functioning (Granvald & Marciszko, 2016; Morgan & Lilienfeld, 2000; Nigg & Huang-Pollock, 2003). Each of these four dispositions is hypothesized to contribute independently to the development of antisocial behavior, but interactions among the dispositions have neither been proposed nor ruled out (Lahey & Waldman, 2005).

The developmental propensity model will require two kinds of tests. Prospective observational studies of the transactions of children who vary in these dispositions with their environments and subsequent changes in their behavior are needed to test the mechanistic hypotheses. Before such intensive studies are conducted, however, the model can be subjected to strong risk of refutation by testing the fundamental hypothesis that variations in these dispositions in childhood and adolescence predict future antisocial behavior. A reliable and valid measure of the three socioemotional dispositions, termed the Child and Adolescent Dispositions Scale (CADS), which can be completed by youth or their parents, was developed for this purpose (Lahey, Applegate, et al., 2008; Lahey, Rathouz, Applegate, Tackett, & Waldman, 2010). Cross-sectional analyses of children and adolescents have supported the model in showing that each disposition was robustly and independently associated with conduct disorder (CD) symptoms, both within and across parent and youth informants (Lahey, Applegate, et al., 2008; Lahey et al., 2010; Waldman et al., 2011). A similar cross-sectional study found that parent-rated CADS dispositions of prosociality and negative emotionality, but not daring, were correlated with CD symptoms (Taylor, Allan, Mikolajewski, & Hart, 2013). In a longitudinal study, the three CADS dispositions measured at age 12 years by parent and youth reports each significantly predicted antisocial behavior three years later (Trentacosta, Hyde, Shaw, & Cheong, 2009). The goal of the present study is to conduct a long-term prospective test of the developmental propensity model by determining if a brief measure of cognitive ability and the three CADS dispositions measured at 10–17 years of age predict symptoms of antisocial personality disorder (APD) and arrests at 22–31 years of age.

METHOD

Participants and Procedures

Participants for the current study were selected from the first wave of the Tennessee Twin Study (TTS) (Lahey, Rathouz, et al., 2008) for a follow-up evaluation 10–15 years later (median = 12 years).

Wave 1 Sample and Measures

The TTS sample is representative of 6–17 year old twins born in Tennessee and living in one of the state’s five metropolitan statistical areas in 2000–2001. The Tennessee Department of Health identified birth records and located families. A random sample was selected, stratified by age and 35 geographic subareas, proportional to the number of families in each subarea. Of 4012 selected households, 3592 (89.5%) were located and screened, with 2646 of the screened families being eligible (co-residence with the adult caretaker at least half the time and fluency in English). Interviews were completed with 2063 adult caretakers (90.8% biological mothers), with a 70% response rate. After exclusion of twin pairs in which either twin had been given a diagnosis of autism, psychosis, or seizure disorder, the sample consisted of 3,990 twins in 1,995 complete pairs (71% non-Hispanic white, 24% African American, and 5% as Hispanic and other groups).

Caretakers and youth were separately administered computer-assisted interviews by trained interviewers using the reliable and valid Child and Adolescent Psychopathology Scale (CAPS) (Lahey et al., 2004). The CAPS queried DSM-IV symptoms of a range of mental disorders during the last year. Symptoms were rated on a four-point scale, reflecting frequency and severity, with means taken of the symptoms to create dimensional measures. CADS items were rated separately by parent and youth informants on the same four-point scale, with means taken of the items on the negative emotionality, daring, and prosociality subscales (Lahey, Applegate, et al., 2008; Lahey et al., 2010). Each child was administered the Digit Span subtest of the WISC-III (Wechsler, 1991) to measure working memory. Because raw digit span scores were used, the youth’s age in wave 1 was controlled in all analyses.

Wave 2 Sample and Measures

Twin pairs for the wave 2 assessments were recruited from the wave 1 TTS sample in four replicates based on age in wave 1 in reverse order: 16–17, 14–15, 12–13, and 10–11 years. Pairs were eligible if the last known address of both twins was within >300 miles of Vanderbilt University (95.2% of twins). The replicates were selected by oversampling on wave 1 CAPS second-order psychopathology dimension scores based on the greater rating of each symptom from the parent or youth. All high-risk pairs were selected if either twin had symptom ratings on either internalizing, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or the combination of ODD and CD symptoms in the top 10% of that age range. In addition, 19–23% of the remainder of each replicate was randomly selected with two constraints: (1) monozygotic pairs were oversampled by randomly excluding 40% of the randomly selected dizygotic pairs, and (2) the exact number selected from the remainder of the sample varied slightly to equate replicate sizes. The resulting replicates each included 100 pairs, except that the fourth replicate had 105 pairs.

Three selected pairs of twins could not be located and 18 selected pairs were declared out of scope due to previous participation in a pilot study, mental or physical incapacity, residence outside the U.S., imprisonment, or death. Screening was completed for 90.0% of the in-scope twins and interviews were completed for 72.2% of the screened sample during 2013–2016, including 248 complete twin pairs (49.6% monozygotic; 66.9% high risk) and 3 individuals without their co-twin. Demographic characteristics of the 499 interviewed participants are in Supplemental Table S1.

Most interviews were conducted in person at Vanderbilt University because neuroimaging was part of the study, but interviews were conducted by telephone for scan-ineligible but in-scope participants. Symptoms of APD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) were assessed using the Young Adult version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children (YA_DISC) (Abram et al., 2015; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000; Witkiewitz et al., 2013). Counts of APD symptoms were based on symptoms reported to be present in the last 12 months. Additionally, lifetime police contacts were queried in this interview.

Data Analyses

Criterion Validity of Self-Reports of APD Symptoms

To assess the validity of the wave 2 self-reports of APD symptoms, the association of counts of APD symptoms and self-reported lifetime history of arrests was quantified using a weighted logistic regression that took sample stratification and clustering into account in SAS 9.4 SURVEYLOGISTIC.

Tests of Predictions from the Developmental Propensity Model

Prospective multiple regression analyses were executed using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors in Mplus 7.4 to test predictions derived from the developmental propensity model. In separate analyses for each informant, these simultaneous negative binomial models tested predictions that counts of symptoms of APD in wave 2 would be independently predicted by wave 1 digit span and prosociality, negative emotionality, and daring. Age in wave 1, the number of years since wave 1, sex, non-Hispanic white versus other race-ethnic group, the log of the total income of the family of origin, and the number of years of education of the twins’ mothers were covariates of no interest in all analyses.

Analyses took stratification and clustering within twin pairs into account and were weighted by the inverse of the probability of selection into wave 2. Because the loss of participants was not negligible, the weights also adjusted for nonresponse using data on demographic characteristics and wave 1 data on psychopathology, dispositions, and working memory. This allows valid parameter estimates when weighted back to the full wave 1 TTS sample, and, by extension, to the population from which the wave 1 sample was drawn (Korn & Graubard, 1999). There were no missing data on any predictor variables, except that maternal education for two mothers was imputed from the mean of nonmissing values on that variable. Although our focus was on counts of APD symptoms, additional tests were conducted of predictive associations between the wave 1 dispositions and the diagnosis of APD and a lifetime history of arrest using the same covariates and weights in SAS SURVEYLOGISTIC.

RESULTS

Tests of Sample Bias

Two sets of planned comparisons assessed biases due to nonparticipation using unweighted logistic regressions. The 499 participants in wave 2 were separately compared to (a) the 275 selected in-scope nonparticipants, and (b) 16 nonparticipants who were out of scope due to incarceration. As shown in Supplemental Table S1, compared to in-scope nonparticipants, participants had better educated mothers, more affluent families, were rated by parents as exhibiting greater prosociality and fewer adolescent CD symptoms, and had higher digit span scores. Compared to incarcerated twins, participants had better educated mothers; were rated by parents lower on negative emotionality, daring, and adolescent CD symptoms, and higher on prosociality; and rated themselves as more prosocial than incarcerated twins. Therefore, in addition to weighting based partly on nonparticipation, because nonparticipants exhibited many of the adolescent characteristics hypothesized to predict APD, all tests of predictive hypotheses in the participants were controlled for the variables on which the included and excluded participants differed to adjust for sampling biases.

Criterion Validity of Self-Reports of APD Symptoms

The validity of self-reported APD symptoms was evaluated by comparing the percent of arrests in persons with each number of symptoms. The weighted percent of individuals reporting each number of APD symptoms and at least one police arrest was 0 (6.2%), 1 (21.7%), 2 (19.4%), 3 (22.6%), and 4+ APD symptoms (45.3%). This significant association of the number of APD symptoms with arrests, OR = 1.60 (95% CI: 1.28–2.01), indicated that the odds of arrest were 60% greater with each one additional APD symptom. Indeed, although the weighted percent of arrests was high among individuals with enough symptoms (4+) to meet adult criteria for APD, it is notable that 95 of the 116 arrests were reported by persons who did not meet diagnostic criteria for APD, with nearly all of these arrests occurring in individuals reporting 1–3 symptoms of APD. This pattern supports treating APD symptoms as a count variable instead of a binary diagnosis.

Tests of the Developmental Propensity Model

Predicting Counts of Adult APD Symptoms

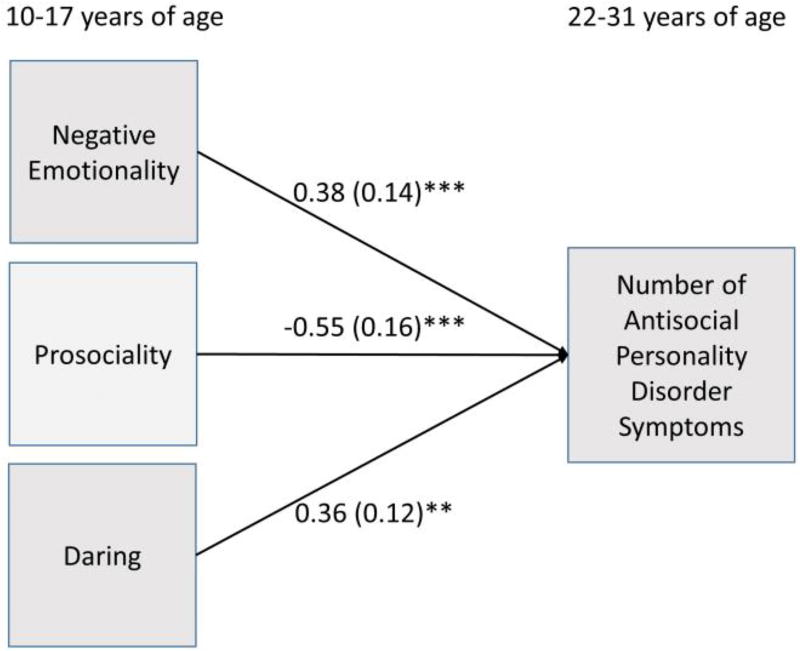

Unweighted correlations among all predictor and outcome variables are presented in Table 1. In this sample, 277 of 499 individuals reported at least one symptom of APD (range 0–7). As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1, the results of Model 1 indicated that the number of APD symptoms in adulthood was independently predicted by youth-rated CADS dispositions of negative emotionality, daring, and prosociality in year 1, but not by digit span, when all demographic covariates shown in Table S2 were controlled. The standardized beta coefficients reported in Table 2 for youth-rated dispositions indicate, for example, that a positive one-unit difference between two individuals on prosociality was associated with a 100*(1-exp(−.55)) = 47% fewer APD symptoms in the individual with higher prosociality versus the reference individual. For each one-unit difference in youth-reported negative emotionality, the expected mean number of APD symptoms was 100*(exp(.38)−1) = 46% greater. Similarly parent-rated negative emotionality and prosociality in wave 1 significantly predicted future APD symptoms, but parent-rated daring did not at p < .05.

Table 1.

Unweighted zero-order correlations among predictor and outcome variables in the longitudinal sample (N = 499).

| Negative Emotionality |

Prosociality | Daring | Digit Span | Adolescent CD |

Adult APD | Police Contacts |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Emotionality | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.15*** | 0.22*** | 0.10* | −0.01 | |

| Prosociality | −0.31*** | −0.10* | 0.02 | −0.35*** | −0.24*** | −0.28*** | |

| Daring | 0.20*** | −0.23*** | 0.07 | 0.21*** | 0.18*** | 0.18*** | |

| Digit Span | −0.18*** | 0.12** | −0.03 | −0.17*** | −0.07 | −0.03 | |

| Adolescent CD | 0.34*** | −0.50*** | 0.23*** | −0.14** | 0.23*** | 0.25*** | |

| Adult APD | 0.22*** | −0.20*** | 0.15** | −0.07 | 0.16*** | 0.35*** | |

| Police Contacts | 0.09* | −0.34*** | 0.24*** | −0.03 | 0.29*** | 0.35*** |

CD = conduct disorder symptoms; APD = antisocial personality disorder symptoms.

Correlations among the youth self-ratings on wave 1 predictor variables above the diagonal; parent ratings below the diagonal.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001 (two-tailed)

Table 2.

Results of simultaneous negative binomial regressions testing the predictions that the number of adult symptoms of antisocial personality disorder is independently predicted by lower digit span scores, lower prosociality, and greater negative emotionality and daring measured in wave, controlling for the demographic covariates shown in Supplemental Table S1 (N = 499).

| Model 1: Not Controlling Wave 1 Conduct Disorder CADS Informant in Wave 1 |

Model 2: Controlling Wave 1 Conduct Disorder CADS Informant in Wave 1 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth Beta (S.E.) |

Parent Beta (S.E.) |

Youth Beta (S.E.) |

Parent Beta (S.E.) |

|

| Predictors | ||||

| Negative emotionality | 0.38 (0.14)*** | 0.48 (0.14)*** | 0.36 (0.14)** | 0.48 (0.15)*** |

| Prosociality | −0.55 (0.16)*** | −0.32 (0.17)* | −0.49 (0.17)** | −0.30 (0.18)* |

| Daring | 0.36 (0.12)** | −0.01 (0.11) | 0.35 (0.12)** | −0.01 (0.12) |

| Digit span | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.06 (0.02) | −0.03 (0.02) |

| Conduct disorder symptoms | - | - | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.04) |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001 (one-tailed tests of directional predictions)

CADS = Child and Adolescent Dispositions Scale

Figure 1.

Unstandardized beta coefficients and standard errors showing that youth-rated negative emotionality, prosociality, and daring in late childhood or adolescence each independently predicted the number of symptoms of antisocial personality disorder in early adulthood.

**p < .01; ***p < .001 (one-tailed tests of directional predictions)

We addressed the possibility that CADS dispositions might predict adult antisocial behavior only because they are a proxy for the number of CD symptoms in wave 1. When mean ratings of wave 1 CD symptoms on a 0–3 scale were the only predictor in weighted models along with the demographic covariates shown in Supplemental Table S2, adult APD symptoms were significantly predicted by parent-reported (β = 0.10, χ2 = 3.16, p < .01) and youth-reported CD symptoms (β = 0.08, χ2 = 3.29, p < .001) in separate models. Therefore, CD symptoms were added as a simultaneous predictor in each model, as shown in the right-hand columns of Table 2. For both informants, wave 1 CD symptoms were not significant predictors of future APD symptoms when the three CADS dispositions and digit span were included in the models, whereas the same CADS dimensions significantly predicted APD symptoms for each informant with or without CD symptoms in the model.

Because a previous longitudinal study suggested that nonaggressive CD symptoms predict APD better than aggressive CD symptoms in boys (Lahey, Loeber, Burke, & Applegate, 2005)—perhaps because APD symptoms are themselves mostly nonaggressive—sensitivity analyses were conducted using separate counts of aggressive and nonaggressive CD symptoms in wave 1. As reported in supplemental tables S3 and S4, there were no qualitative changes in the results for CADS dimensions when these two facets of CD were included as predictors.

Predicting the Diagnosis of APD

We examined the prediction of the binary diagnosis of APD by the dispositions, limiting the diagnostic definition to adult criteria to avoid confounding wave 1 predictors with the criteria for APD of CD symptoms before age 15. In this sample, 92 of 499 individuals met adult criteria for APD. In weighted logistic regressions that took stratification and clustering into account, when all demographic covariates shown in Supplemental Table S5 were included, but the dispositions and digit span were not, the diagnosis of APD according to adult criteria was predicted by both parent-reported (adjusted OR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.06 – 1.42), and youth-reported CD symptoms (adjusted OR = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.05 – 1.32) in separate analyses. As shown in Table 3, when CD was not included as a wave 1 predictor, the diagnosis of APD was significantly predicted in the theory-based directions by parent-rated CADS negative emotionality and prosociality, but not by parent-rated daring or digit span. Similarly, the adult diagnosis of APD was predicted by youth-rated CADS prosociality and negative emotionality, but not by youth-rated daring or digit span. When wave 1 CD was included as a predictor, CD did not significantly predict APD diagnosis, but parent-rated negative emotionality and prosociality predicted the diagnosis. In the parallel model for the youth informant, prosociality and daring significantly predicted the diagnosis of APD.

Table 3.

Results of logistic regressions testing the independent associations of digit span scores and three dispositional dimensions measured in wave 1 with the binary outcomes of the diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder (adult criteria only) and lifetime history of police arrests, controlling for demographic covariates shown in Table S2 (N = 499).

| Model 1: Not Controlling Wave 1 Conduct Disorder CADS Informant in Wave 1 |

Model 2: Controlling Wave 1 Conduct Disorder CADS Informant in Wave 1 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth OR (95% CI) |

Parent OR (95% CI) |

Youth OR (95% CI) |

Parent OR (95% CI) |

|

| Outcome: Diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder | ||||

| Predictors | ||||

| Negative emotionality | 1.34 (0.50 – 3.56)* | 3.30 (1.93 – 5.65)*** | 1.23 (0.43 – 3.48) | 3.26 (1.87 – 5.68)*** |

| Prosociality | 0.37 (0.16 – 0.83)* | 0.50 (0.26 – 0.97)* | 0.44 (0.18 – 1.08)* | 0.52 (0.24 – 1.13)* |

| Daring | 1.90 (0.95 – 3.78) | 0.90 (0.48 – 1.68) | 1.79 (0.91 – 3.53)* | 0.89 (0.46 – 1.71) |

| Digit span | 0.87 (0.71 – 1.06) | 0.87 (0.71 – 1.06) | 0.88(0.71 – 1.08) | 0.87 (0.71 – 1.07) |

| Conduct disorder symptoms | - | - | 1.08 (0.97 – 1.22) | 1.02 (0.84 – 1.25) |

| Outcome: Lifetime history of arrest | ||||

| Predictors | ||||

| Negative emotionality | 1.21 (0.65 – 2.25) | 0.96 (0.47 – 1.94) | 1.07 (0.56 – 2.04) | 0.89 (0.43 – 1.86) |

| Prosociality | 0.18 (0.08 – 0.40)*** | 0.17 (0.09 – 0.33)*** | 0.23 (0.10 – 0.50)*** | 0.19 (0.10 – 0.37)*** |

| Daring | 2.09 (1.31 – 3.33)*** | 2.65 (1.53 – 4.59)*** | 1.94 (1.19 – 3.16)*** | 2.60 (1.49 – 4.55)*** |

| Digit span | 1.04 (0.90 – 1.20) | 1.04 (0.89 – 1.22) | 1.05 (0.92 – 1.21) | 1.05 (0.90 – 1.23) |

| Conduct disorder symptoms | - | - | 1.11 (0.96 – 1.27) | 1.11 (0.92 – 1.34) |

CADS = Child and Adolescent Dispositions Scale.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

95% confidence intervals for odds ratios are based on two-tailed tests, whereas one-tailed p levels are presented for directional predictions.

Predicting Lifetime History of Police Arrest

In weighted logistic regressions including the same demographic covariates, a lifetime history of arrest reported in early adulthood by the 499 interviewed participants was predicted by both parent-reported (adjusted OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.10 – 1.59), and youth-reported wave 1 CD symptoms (adjusted OR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.02 – 1.44) in separate analyses. When CD symptoms were not in the model, parent-rated daring and prosociality each independently predicted arrests (Table 3). Similarly, for both parent and youth informants, when CD symptoms were not in the model, daring and prosociality each independently predicted arrests. Furthermore, or both informants, when CD symptoms and the three dispositions were simultaneous predictors, CD did not predict lifetime arrests, but prosociality and daring were robust predictors.

DISCUSSION

Prospective longitudinal data were used to test key directional hypotheses derived from the developmental dispositions model of antisocial behavior (Lahey & Waldman, 2005, 2012; Lahey et al., 1999). According to both parent and self-ratings on the CADS at 10–17 years of age, higher negative emotionality and lower prosociality each independently predicted more self-report symptoms in early adulthood. In addition, higher daring significantly predicted more APD symptoms according to parent but not youth ratings when CD was a simultaneous predictor. As hypothesized, youth-rated prosociality, negative emotionality, and daring were found to be only modestly correlated in wave 1 (Table 1) and these dispositional dimensions each accounted for independent variance in the prediction of future APD. Consistent with the developmental propensity model, each CADS disposition independently predicted the number of self-reported APD symptoms years later in adulthood, with the exception of parent-rated daring. Indeed, the net magnitude of these three independent predictive associations of numbers of APD symptoms from the three CADS dispositions was quite substantial, particularly for youth-rated dispositions. When the outcome was ever being arrested by the police, prosociality and daring rated by each informant were both robust independent predictors. Had these key hypotheses not been supported, research on the mechanistic hypotheses of the developmental propensity model regarding the ways in which each socioemotional disposition fosters the development of antisocial behavior would not be justified.

CD symptoms were significant predictors of all antisocial outcomes controlling for demographics when the three CADS dispositions were not in the model. When CD was added to models that included the three CADS dispositions, however, CD did not significantly predict any outcomes, but the same CADS dispositions predicted the antisocial outcomes when CD was a predictor.

There are at least three potentially important implications of these findings:

Like previous studies, these findings indicate long-term stability in behavior (Copeland, Wolke, Shanahan, & Costello, 2015; Lahey, Van Hulle, et al., 2008). They do not tell us why early behavior predicts future behavior, however (Lahey, 2015). Chronic or correlated adverse conditions may separately give rise to each aspect of problem behavior at different ages in the absence of any causal relation between earlier and later behavior. In contrast, genetic and environmental etiologies early in life may give rise to individual differences in child dispositions that transact with environments (Sameroff & MacKenzie, 2003) to give rise to later antisocial behaviors, as hypothesized in the developmental propensity model. If so, the robust continuity between CADS dispositions and later APD symptoms suggests that early interventions that reduce negative emotionality and daring and promote prosociality could reduce future antisocial behavior. This is not a foregone conclusion, given that we cannot infer causality from these analyses, but it is a plausible hypothesis that should be tested.

Consistent with our earlier hypotheses (Lahey & Waldman, 2012), the present findings indicate that adult APD behaviors are robustly predicted by earlier negative emotionality, which is a disposition that is also strongly related to essentially all other dimensions of psychopathology in children, adolescents, and adults through the general factor of psychopathology (Lahey, Krueger, Rathouz, Waldman, & Zald, 2016). This means that antisocial behavior is strongly linked to other forms of psychopathology and should be understood in that broader context.

It is interesting that early negative emotionality was a robust predictor of future adult APD behaviors, but not a lifetime history of arrest. In contrast, prosociality and daring predict arrests. This suggests that more emotional individuals with APD symptoms are less likely to be arrested, perhaps because they exhibit a less psychopathic profile of antisocial behavior.

Consistent with the logic of the NIMH Research Domains Criteria (RDoC) initiative (Cuthbert & Insel, 2013), it is possible that each CADS disposition reflects a largely distinct psychobiological process that is more homogeneous than antisocial behavior. If so, studies of the etiology and psychobiological mechanisms of dispositions may be more tractable and informative than studies of the causes and mechanisms of APD.

Limitations

Tests of the model were limited by the modest sample size, which could have resulted in some associations among variables in the population not being detected as statistically significant. Furthermore, interactions among the dispositions and interactions of the dispositions with sex and other demographic factors were not tested due to the sample size. The hypothesis that cognitive ability would be a predictor of APD symptoms was tested, but only using a measure of working memory, which may have led to an underappreciation of the role of cognitive deficits (Keenan & Shaw, 2003). Future tests of the developmental propensity model should include stronger measures of cognitive and language abilities to more comprehensively examine the role of cognitive deficits.

The assessment of arrest addressed a socially important aspect of antisocial behavior, but they were measured on a lifetime basis that could have overlapped in time with ratings of CD and dispositions and were subject to retrospective recall biases. Notably, the present study only tested the three dispositional constructs specified in the developmental propensity model. Other dispositional traits also predict of adult antisocial behavior and should be studied (Lynam & Widiger, 2007).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant R01-MH098098 from the National Institute of Mental Health and CTSA grants UL1-TR000445 and UL1-TR000430.

Contributor Information

Benjamin B. Lahey, University of Chicago

Quetzal A. Class, University of Chicago

David H. Zald, Vanderbilt University

Paul J. Rathouz, University of Wisconsin

Brooks Applegate, Western Michigan University.

Irwin D. Waldman, Emory University

References

- Abram KM, Zwecker NA, Welty LJ, Hershfield JA, Dulcan MK, Teplin LA. Comorbidity and continuity of psychiatric disorders in youth after detention: A prospective longitudinal study. Jama Psychiatry. 2015;72:84–93. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fifth. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Principles of behavior modification. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Wolke D, Shanahan L, Costello J. Adult functional outcomes of common childhood psychiatric problems A prospective, longitudinal study. Jama Psychiatry. 2015;72:892–899. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, Insel TR. Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: The seven pillars of RDoC. Bmc Medicine. 2013;11 doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Kahn RE. Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:1–57. doi: 10.1037/a0033076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Viding E. Antisocial behavior from a developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1111–1131. doi: 10.1017/s0954579409990071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granvald V, Marciszko C. Relations between key executive functions and aggression in childhood. Child Neuropsychology. 2016;22:537–555. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2015.1018152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Shaw DS. Starting at the beginning: Exploring the etiology of antisocial behavior in the first years of life. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, editors. Causes of Conduct Disorder and Juvenile Delinquency. New York, NY: Guilford Press Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 153–181. [Google Scholar]

- Korn EL, Graubard BI. Analysis of health surveys. New York: Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB. What we need to know about callous-unemotional traits: Comment on Frick, Ray, Thornton, and Kahn (2014) Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:58–63. doi: 10.1037/a0033387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB. Why are children who exhibit psychopathology at high risk for psychopathology and dysfunction in adulthood? Jama Psychiatry. 2015;72:865–866. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Chronis AM, Jones HA, Williams SH, Loney J, Waldman ID. Psychometric characteristics of a measure of emotional dispositions developed to test a developmental propensity model of conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:794–807. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Waldman ID, Loft JD, Hankin BL, Rick J. The structure of child and adolescent psychopathology: Generating new hypotheses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:358–385. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, D'Onofrio BM, Van Hulle CA, Rathouz PJ. Prospective association of childhood receptive vocabulary and conduct problems with self-reported adolescent delinquency: Tests of mediation and moderation in sibling-comparison analyses. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:1341–1351. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9873-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Krueger RF, Rathouz PJ, Waldman ID, Zald DH. A hierarchical causal taxonomy of psychopathology across the life span. Psychological Bulletin. 2016;143:142–186. doi: 10.1037/bul0000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Loeber R, Burke JD, Applegate B. Predicting future antisocial personality disorder in males from a clinical assessment in childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:389–399. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, Applegate B, Tackett JL, Waldman ID. Psychometrics of a self-report version of the child and adolescent dispositions scale. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:351–361. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, Applegate B, Van Hulle C, Garriock HA, Urbano RC, Waldman ID. Testing structural models of DSM-IV symptoms of common forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:187–206. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Van Hulle CA, Keenan K, Rathouz PJ, D’Onofrio BM, Rodgers JL, Waldman ID. Temperament and parenting during the first year of life predict future child conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:807–823. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9247-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID. A developmental propensity model of the origins of conduct problems during childhood and adolescence. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, editors. Causes of Conduct Disorder and Juvenile Delinquency. New York, NY: Guilford Press Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 76–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID. A developmental model of the propensity to offend during childhood and adolescence. In: Farrington DP, editor. Advances in criminological theory. Vol. 13. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 2005. pp. 15–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID. Annual Research Review: Phenotypic and causal structure of conduct disorder in the broader context of prevalent forms of psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:536–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID, McBurnett K. Annotation: The development of antisocial behavior: An integrative causal model. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:669–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Widiger TA. Using a general model of personality to identify the basic elements of psychopathy. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:160–178. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan AB, Lilienfeld SO. A meta-analytic review of the relation between antisocial behavior and neuropsychological measures of executive function. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:113–136. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Huang-Pollock CL. An early-onset model of the role of executive functions and intelligence in conduct disorder/delinquency. Causes of Conduct Disorder and Juvenile Delinquency. 2003:227–253. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist. 1989;44:329–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquero AR, Shepherd I, Shepherd JP, Farrington DP. Impact of offending trajectories on health: Disability, hospitalisation and death in middle-aged men in the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2011;21:189–201. doi: 10.1002/cbm.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, MacKenzie MJ. Research strategies for capturing transactional models of development: The limits of the possible. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:613–640. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Reid JB, Patterson GR. A social learning model of child and adolescent antisocial behavior. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, editors. Causes of Conduct Disorder and Juvenile Delinquency. New York: Guilford; 2003. pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Allan N, Mikolajewski AJ, Hart SA. Common genetic and nonshared environmental factors contribute to the association between socioemotional dispositions and the externalizing factor in children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:67–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta CJ, Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Cheong JW. Adolescent dispositions for antisocial behavior in context: The roles of neighborhood dangerousness and parental knowledge. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:564–575. doi: 10.1037/a0016394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldman ID, Tackett JL, Van Hulle CA, Applegate B, Pardini D, Frick PJ, Lahey BB. Child and adolescent conduct disorder substantially shares genetic influences with three socioemotional dispositions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:57–70. doi: 10.1037/a0021351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. The Wechsler intelligence scale for children—third edition. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, King K, McMahon RJ, Wu J, Luk J, Bierman KL CPPRG. Evidence for a multi-dimensional latent structural model of externalizing disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:223–237. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9674-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.