INTRODUCTION

The healthcare system is burdened with both overuse and underuse of medical services. Overuse is described as the provision of a healthcare service that poses more harm than benefit, while underuse is the failure to deliver a service that poses more benefit than harm.1 Right care is defined as care optimizing health of a population by delivering what is needed, wanted, effective, and responsible in its use or resources. Previous high-value care lists have primarily focused on overuse, and have failed to explore underuse. Furthermore, the development of these lists has not commonly involved patient or patient-advocate input—a process that may achieve broader public recognition and increased uptake.2 In this study, we utilized a multi-institutional, interdisciplinary approach that included patients and patient advocates in identifying five examples of overuse and underuse to create the Right Care Top 10 list.

METHODS

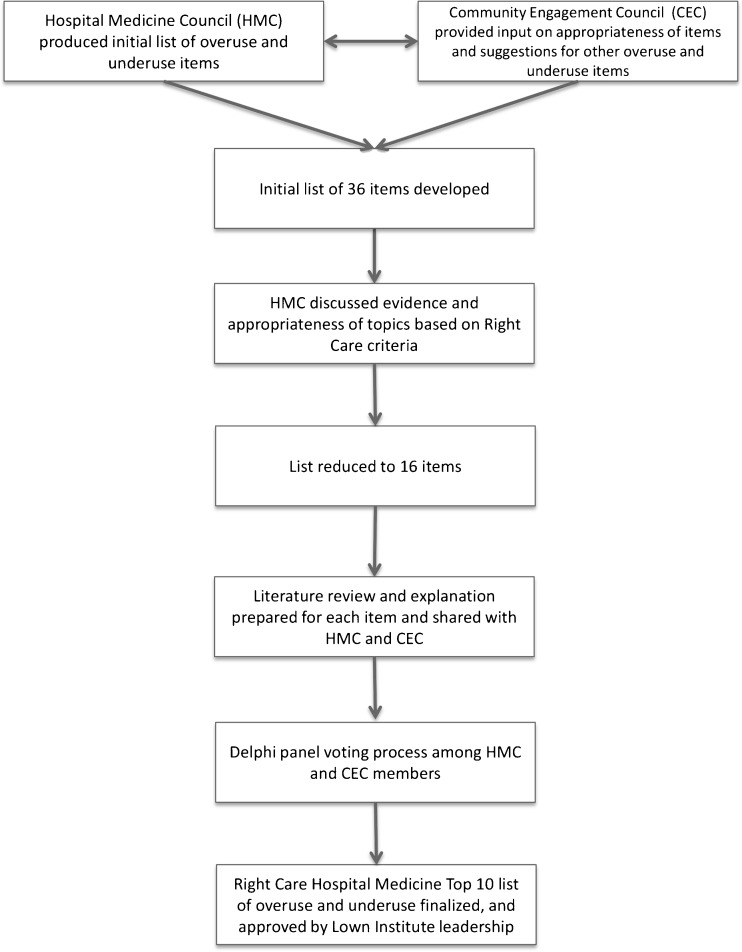

Physicians, advanced practitioners, and nurses within the Right Care Alliance (RCA) Hospital Medicine Council collaborated with patient advocates from the Community Engagement Council. The aim was to develop a list of five do’s and don’ts, or areas of underuse and overuse, respectively, in adult hospital medicine. A guiding framework for inclusion was that the items (1) matter to patients, (2) be evidence-based, and (3) be infractions of value-focused care, and (4) have high potential to harm or benefit. The councils were formed after open invitation to RCA members, with monthly calls held among participants between August 2016 and 2017. Following structured discussions and literature review, the Hospital Medicine Council generated a preliminary list. In parallel, two clinicians (HJC, ST) reviewed these items with patient advocates and solicited further suggestions. Thirty-two items were included on the initial list (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Right care hospital medicine Top 10 list development overview.

Following iterative discussions and literature review, items that did not fit the inclusion criteria were removed, shortening the list to 16. Evidence for each recommendation was provided for all participants. Two clinicians (HJC, ST) offered technical and clinical clarifications to patient advocates during an open 2-week voting period. Consensus between clinicians and patients was reached through a modified Delphi voting process3 using an online survey instrument (SurveyMonkey®).

RESULTS

Ten clinicians and 11 patient advocates participated. The top five overuse (Don’ts) and five underuse (Do’s) recommendations were established (Table 1). Only one underuse recommendation focused on specific clinical testing and treatment compared to all five overuse recommendations. Of the four recommendations that focused on systems improvement, three centered on communication.

Table 1.

Hospital Medicine Right Care Top 10 Recommendations with Mean Response Scores Among Patient Advocates and Clinicians

| Mean response scores* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation | Combined | Patient advocate | Clinician | |

| Underuse (Do’s) | Implement programs designed to promote sleep in the inpatient setting. | 6.38 (± 1.21) | 6.4 (± 1.43) | 6.4 (± 0.92) |

| Provide verbal or written communication to the patient’s primary care provider prior to discharge. | 6.29 (± 1.28) | 6.7 (± 0.62) | 5.8 (± 1.6) | |

| Provide personalized instructions (including education) to patients on discharge. | 6.14 (± 1.32) | 5.9 (± 1.68) | 6.4 (± 0.66) | |

| Check orthostatic vital signs on patients with syncope prior to considering testing beyond an electrocardiogram. | 5.94 (± 1.51) | 6.6 (± 0.49) | 5.5 (± 1.8) | |

| Use structured verbal and written communication for shift and service handoffs between providers. | 5.89 (± 1.49) | 5.8 (± 1.71) | 6 (± 1.26) | |

| Overuse (Don’ts) | Don’t order daily labs in the presence of clinical stability or in the absence of a specific clinical question. | 6.47 (± 0.7) | 6.7 (± 0.45) | 6.3 (± 0.78) |

| Don’t order telemetry monitoring in the absence of a specific clinical indication. | 6.36 (± 0.72) | 6.3 (± 0.83) | 6.4 (± 0.66) | |

| Don’t routinely order laboratory and imaging tests prior to evaluating and examining the patient. | 6.25 (± 1.55) | 6.8 (± 0.4) | 5.7 (± 2.0) | |

| Don’t order urine electrolytes in acute kidney injury in the absence of oliguria or hepatic disease, and don’t order renal ultrasound without an evidence-based risk stratification framework. | 5.85 (± 1.17) | 6 (± 0.71) | 5.8 (± 1.31) | |

| Don’t order computed tomography of the head to evaluate inpatient delirium in the absence of neurologic findings. | 5.75 (± 1.2) | 6.3 (± 0.75) | 5.4 (± 1.28) | |

*Respondents were asked to evaluate each recommendation on a scale from 1 to 7 (1, does not meet selection criteria; 4, meets some criteria but not most; 7, meets selection criteria)

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first high-value list that (1) utilized principles of co-creation4 with equitable representation from clinicians and patient advocates throughout the entire process, and (2) focused on both overuse and underuse. This process may serve as a rubric and provide future guidance on how to integrate patient’s perspectives into the development of value-based recommendations.

Clinicians have predominantly developed high-value lists with patient input integrated after the recommendations were finalized.2 With recent data suggesting only a modest impact following the release of Choosing Wisely,5 patient engagement during policy creation may be a possible solution.6

While highly innovative, Choosing Wisely™ had a singular emphasis on decreasing overuse and did not address the alternate side of the value coin, underuse.1 Additionally, in focusing on overuse and underuse, we act to steer patient and provider views away from rationing and reassure that these lists are meant to improve the overall quality and value of care provided.

Our study does have limitations. Despite efforts to offer technical clarification, some patient advocates reported refraining from voting on some items due to uncertainty of medical terminology, leading to a possible selection bias. For example, four of ten recommendations focused on systems and communications concerns—issues that are relatable and easy to comprehend. Although this may be perceived as a limitation, it may also reflect what is truly important from the patients’ view.

In conclusion, a co-creation approach that utilizes both physician and patient input is critical in improving healthcare value. Moreover, a singular focus on overuse fails to acknowledge that improved quality and value can also come from addressing underuse.1 Optimizing care on both ends of the utilization spectrum has the greatest potential to improve acceptance and uptake in the clinical setting. This collaborative, patient-oriented process can set an example for future high-value lists.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Carissa Fu and patient advocates of the Community Engagement Council. There were no prior presentations of this work.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Saini V, Brownlee S, Elshaug AG, Glasziou P, Heath I. Addressing overuse and underuse around the world. Lancet. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Born KB, Coulter A, Han A, et al. Engaging patients and the public in Choosing Wisely. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(8):687–691. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitch K. The Rand/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. Rand: Santa Monica; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P, et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(7):509–517. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, et al. Early trends among seven recommendations from the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA internal medicine. 2015;175(12):1913–1920. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2013;32(2):207–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]