Abstract

Products of ultraviolet (UV) irradiation such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) stimulate melanin synthesis. Reactive sulfur species (RSS) have been shown to have strong ROS and NO scavenging effects. However, the instability and low retention of RSS limit their use as inhibitors of melanin synthesis. The free thiol at Cys34 on human serum albumin (HSA) is highly stable, has a long retention and possess a high reactivity for RSS. We report herein on the development of an HSA based RSS delivery system. Sulfane sulfur derivatives released from sodium polysulfides (Na2Sn) react readily with HSA. An assay for estimating the elimination of sulfide from polysulfide showed that almost all of the sulfur released from Na2Sn bound to HSA. The Na2Sn-treated HSA was found to efficiently scavenge ROS and NO produced from chemical reagents. The Na2Sn-treated HSA was also found to inhibit melanin synthesis in B16 melanoma cells and this inhibition was independent of the number of added sulfur atoms. In B16 melanoma cells, the Na2Sn-treated HSA also inhibited the levels of ROS and NO induced by UV radiation. Finally, the Na2Sn-treated HSA inhibited melanin synthesis from L-DOPA and mushroom tyrosinase and suppressed the extent of aggregation of melanin pigments. These data suggest that Na2Sn-treated HSA inhibits tyrosinase activity for melanin synthesis via two pathways; by directly inhibiting ROS signaling and by scavenging NO. These findings indicate that Na2Sn-treated HSA has potential to be an attractive and effective candidate for use as a skin whitening agent.

Keywords: Ultraviolet irradiation, Human serum albumin, Reactive sulfur species, Whitening agent, Oxidative stress

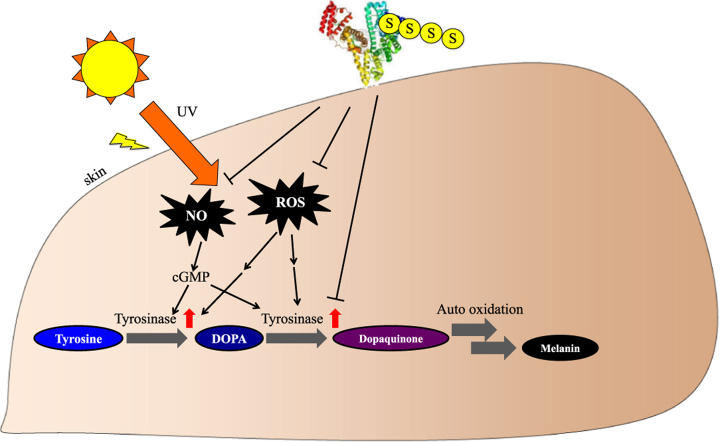

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

We developed of an Reactive sulfur species delivery system based on human serum albumin.

-

•

The novel polysulfides-added albumin could inhibit melanin synthesis in melanocyte.

-

•

The polysulfides-added albumin also inhibited the levels of ROS and NO induced by UV radiation.

-

•

The polysulfides-added albumin has the potential to be an attractive candidate for a whitening agent.

1. Introduction

Ultraviolet (UV) irradiation produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) that ultimately cause cell death [1]. To protect the skin from UV damage, melanin, a dark colored pigment, is produced by melanocytes [2]. While melanin is essential for skin health, a demand for melanin scavenging preparations exists. Chloasma (melasma) is a condition in which the skin develops discolored areas that are caused by overproduction of melanin and are sometimes regarded as a metaphor of aging. In addition, inhibitors of melanin synthesis are popular cosmetics for brightening the skin, especially in Asian countries [3].

Tyrosinase catalyzes the production of melanin from tyrosine via DOPA and dopaquinone in melanocytes [4]. Its activity is regulated by a variety of factors such as ERK1/2 and Akt signaling [5]. ROS such as hydrogen peroxide produced by UV irradiation, activates tyrosinase and promotes melanin synthesis in melanocytes [2]. UV also causes the production of nitric oxide (NO) and stimulates tyrosinase activity via cGMP [6], a second messenger of NO.

On the other hand, thiol compounds with anti-oxidant effect has been widely used as supplements, radioprotection agents and perm agents [7]. Thiol-containing compounds undergo self-oxidation to form sulfonic acid, sulfenic acid and sulfonic acid [8]. Thiol also scavenges NO via S-nitrosation [8]. Because of these effects, thiol-containing compounds are often used in treating chloasma [7], [9]. However, the skin whitening effect of thiols is very weak, a demand for more effective ROS and NO scavenging agents exists.

Reactive sulfur species (RSS) including cysteine persulfide have recently been reported to have stronger anti-oxidant effects than thiols. RSS contain a reactive thiol group [10] and the pKa of most RSS are much lower than that for thiols [11]. Therefore, RSS can react effectively with both ROS and NO and predicted to reduce the extent of melanin production. Sodium polysulfides (Na2Sn), diallyltrisulfide (DATS) and dimethyltrisulfides (DMTS) are commonly used as RSS donors [12]. However, Na2Sn has a low retention at neutral pH and has an offensive smell. In addition, DATS and DMTS, which are produced by garlic and onions are also odorous and their potential for such treatments is limited [13]. Furthermore, the half-life of Na2Sn is very short in serum and, based on in vivo models, multiple injections are needed for them to be effective. Thus, the development of novel RSS-delivery-systems would be highly desirable.

Human serum albumin (HSA) is the most abundant protein in serum and is widely used as a drug carrier because of its biocompatibility and long plasma retention properties [14], [15]. HSA contains a total of 35 Cys residues and one of them, Cys34, is present in the form of a free thiol group [16]. Cys34 is sometimes a target for a drug binding site, because of its reactive thiol group [17], [18]. For example, in the presence of nitric oxide (NO) the Cys34 thiol group is S-nitrosated. We previously demonstrated that S-nitrosated HSA (SNO-HSA) allows NO to be retained for long periods in serum [19]. SNO-HSA has various biological functions, including a liver protective effect against ischemia/reperfusion [20] and tumor suppressing effects [21].

Consequently, we hypothesized that HSA could be used as a RSS carrier (such as SNO-HSA) via the S-sulfhydration of Cys34-SH. As a source of polysulfur, DATS and DMTS are limited because of their lipophilicity and volatility. Hence, commercially available Na2Sn (Na2S, Na2S2, Na2S3 and Na2S4) was used in this study. Ogasawara et al. previously prepared sulfur-bound serum albumin reacted with sodium sulfide (NaHS) by a simple mixing of the reagents [22]. The sulfur from NaHS was added to Cys34 and the resulting preparation protected liver damage caused by lipid peroxide. We adopted this method for preparing RSS-added-HSA using Na2Sn for RSS delivery.

In this work, we reported the preparation of Na2Sn-treated HSA and its use as a novel delivery system of RSS. The added sulfur was analyzed by means of a sulfane sulfur probe [23] and the elimination of sulfide from polysulfide [24]. To evaluate the effect of Na2Sn-treated HSA on skin whitening, the effect of the Na2Sn-treated HSA on melanin synthesis was studied using a B16 melanoma cell line.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

Human serum albumin (HSA) was purchased from KAKETSUKEN (Kumamoto, Japan) and all HSA samples were defatted by a charcoal treatment. Sodium sulfide and sodium tetrasulfide were purchased from DOJINDO Laboratory (Kumamoto, Japan). Sulfane sulfur probe 4 (SSP4) was prepared as previously described [23]. L-DOPA, glutathione, (DTNB), ascorbic acid and sodium satiric Griess reagent (sulfanilamide, naphthylethylenediamine-HCl) were purchased from Nakarai Chemicals (Kyoto, Japan). Sephadex G-25 desalting column (φ 1.6 × 2.5 cm) was purchased from GE Healthcare (Kyoto, Japan). Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) were obtained from Wako Pure Chemical (Osaka, Japan). Mushroom tyrosinase was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All other chemicals were of the best grade that was commercially available, and all solutions were prepared in deionized and distilled water.

2.2. BCA protein assay

Protein concentrations were measured using a BCA protein assay. 10 μL aliquots of samples and bovine serum albumin (BSA) standards were incubated in 100 μL of reaction buffer at 25 °C for 30 min. After the reaction, micro-plate reader was used to measure the absorbance of 540 nm. BSA was used to construct a standard curve.

2.3. Synthesis of Na2Sn treated-HSA

HSA (300 μM) was incubated with 1 mM of sodium polysulfides (Na2Sn) in PBS (pH 7.4) for 1 h at 37 °C. After the reaction, excess sodium polysulfides were removed by gel filtration with a Sephadex G-25 column.

2.4. Determination of sulfur binding rate by elimination method for sulfide from polysulfide (EMSP)

EMSP was prepared as previously described (3×EMSP by addition of 792 mg of L-ascorbic acid to 5 mL of 3 N of NaOH) [24]. Samples (7.5 μM, 133 μL) were incubated with 66.7 μL of 3×EMSP for 3 h at 37 °C. A 1% zinc acetate solution (600 μL) was then added to the reaction solution, followed by vortexing immediately. The samples were centrifuged at 8,000×g for 5 min and washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) twice. After removing the supernatants, deionized and distilled water (200 μL) was added to the precipitates. After adding 1% zinc acetate (300 μL), 50 μL of 20 mM N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine and 20 mM FeCl3 in 7.2 N HCl, the solution was incubated for 30 min at 25 °C. Samples were centrifuged at 8000×g for 1 min and transferred into 96-well plates and the OD at 665 nm measured. Na2S was used to construct a standard curve.

2.5. Detection of sulfane sulfur with SSP4

Each sample (20 μM) was incubated with 5 μM of SSP4 in 1 mM Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide / PBS (pH 7.4) for 10 min at 25 °C. After incubation, the fluorescence measured by a spectrophotometer (JASCO Corporation) with excitation at 457 nm, emission at 490–535 nm.

2.6. DPPH radical tests

DPPH (250 μM) in ethanol was mixed with the same amount of MES buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4). Na2Sn-treated HSA (40 μM) was the added to this DPPH solution, which was then incubated for 30 min at 25 °C and the absorbance of the DPPH radicals was measured at 540 nm. Scavenged radical rates were converted using the following formula;

Scavenged radical (%) = (Abssample-Abspbs)/ Abspbs × 100

2.7. NO and SNO analysis

Na2Sn-treated HSA (50 μM) was incubated with an NO donor, NOC7 (200 μM), for 30 min at 25 °C. After the reaction, the concentration of NO and SNO were measured by a Griess assay with minor modifications [25]. The Griess reagent solution was prepared by mixing 0.1% N-1-Naphtylethylene-diamide dihydrochloride and 1% sulfanilamide in 2% phosphoric acid. The reaction buffer was composed of 0.1 M NaCl, 0.5 mM DTPA and 10 mM AcONa・AcOH (pH 5.5). Samples (20 μM) were reacted with the Griess reagent solution (60 μL) in reaction buffer (110 μL) with 3 mM HgCl2 in 10 mM Na Acetate (pH 5.5). After a 15 min incubation, the absorbance of 540 nm was measured by means of a microplate reader. The remaining NO/SNO ratio (%) was calculated and compared to PBS values for the samples.

2.8. Cell culture

B16 melanoma cells were provided by the Japanese Cancer Research Resources Bank (JCRB, Tokyo, Japan), and were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and an antibiotics solution. Cells were grown with maintained at 37 °C in humidified air containing 5% CO2 in incubator (passage number 10–20).

2.9. Melanin production

B16 melanoma cells were seeded in 24 well plates at a concentration of 2.5×104 cells/well and cultured under 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h. Samples were treated with 0.4 mM tyrosine and 10 mM NH4Cl in DMEM containing 10% FBS and then incubated under 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 72 h. After the incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS and dissolved in 1 N NaOH (200 μL). After a 2 h incubation on 60 °C, the absorption (405 nm) was measured by means of a micro-plate reader.

2.10. UV radiations

A hand held UV lamp was used to irradiate the samples at a distance of 5 cm distance from the well plate. This UV lamp provides a UV intensity of 614 or 743 μW/cm2 respectively with 254 nm or 365 nm radiation from a distance of 5 cm.

2.11. Scavenging activity of Na2S4-treated HSA against intracellular ROS, NO, RSS

ROS and NO in B16 melanoma cells were measured by each of the fluorescence probes, CM-H2DCF-DA and DAF-FM-DA, respectively. B16 melanoma cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a concentration of 1 × 104 cells/well and cultured in 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. After culturing, the media was removed and replaced with CM-H2DCF-DA (5 μM) or DAF-FM-DA (10 μM) in PBS. The probes were taken up by the cells by incubating them at 37 °C for 30 min. After the reaction, the supernatants were removed, the samples diluted in PBS and the fluorescence measured immediately. Cells were radiated by a UV lamp for 15 min. After the irradiation, the fluorescence intensity (Ex. 485 nm, Em. 535 nm) was measured by means of a fluorescence micro-plate reader.

2.12. Mushroom tyrosinase activity and melanin aggregation

Tyrosinase and L-DOPA solutions were prepared in PBS (pH 7.4) immediately before the assay. Tyrosinase, isolated from mushrooms, was used for examining the inhibitory activity of Na2Sn-treated HSA. A 20 μL portion of mushroom tyrosinase (537 U/mL) and 100 μL of Na2Sn-treated HSA (40 μM) were mixed well with PBS (60 μL) in 96 well plates and 20 μL of L-DOPA (5 mM) was then added. After a 30 min incubation, the level of synthesized melanin was analyzed by measuring the OD 490 nm. For assaying melanin aggregation, the mixture was centrifuged at 20,000 g, 15 min for 3 h. The white arrow shows the aggregated material. Non-aggregated melanin in the supernatant was measured at an OD of 490 nm.

2.13. Safety tests

The topical cream used in this study was prepared by mixing water (30 mL) Jojoba Oil (15 mL) and 5 g of emulsifying wax at 60 °C. After cooling, the Na2S4-treated HSA (20 μM) and the resulting suspension were mixed well. The Skin Irritation Test was done following the OECD Test Guideline 439 using the LabCyte Epi-Model (a 3D cultured human skin model).

2.14. Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of the collected data was evaluated by ANOVA analysis followed by Newman-Keuls method for more than 2 means. Differences between the groups were evaluated by Student's t-test. P < 0.05 was regarded as being statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Preparation of S-sulfydrated HSA

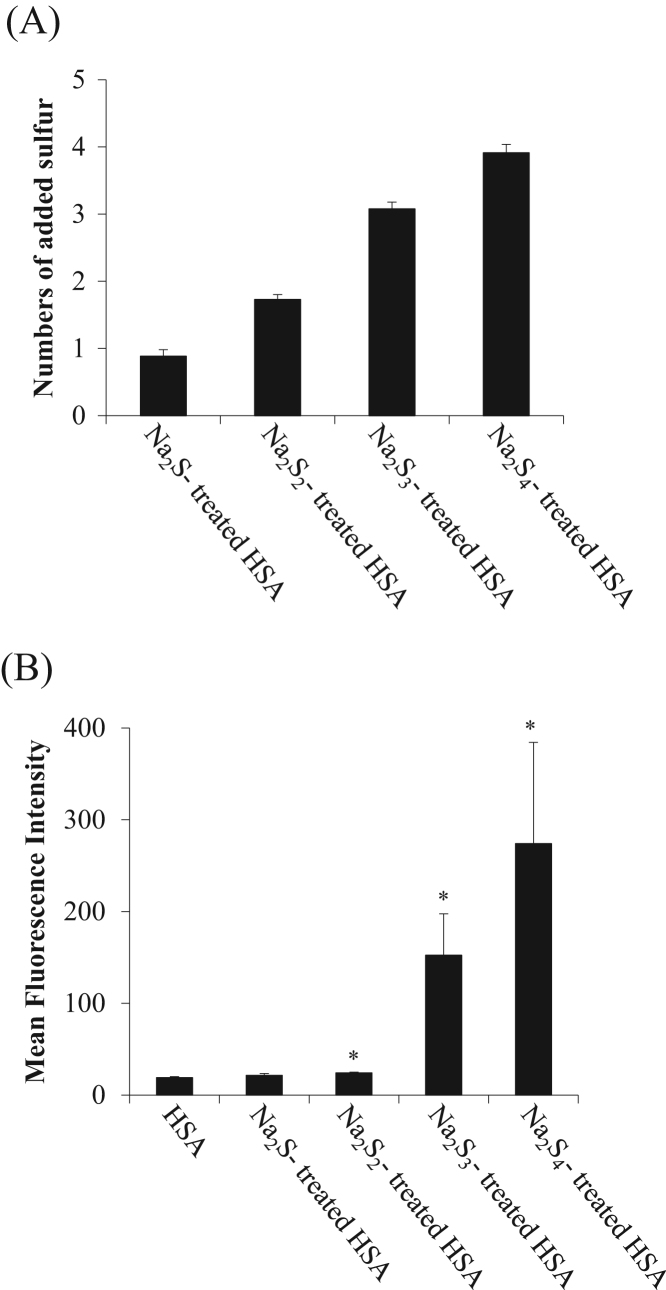

Na2Sn-treated HSA was prepared from HSA that had been incubated with Na2Sn and subjected to gel filtration after the reaction. To assess the amount of sulfane sulfur in the sample, EMSP, a novel quantitative method we previously developed, was employed [24]. Hence, Na2S4-treated HSA was prepared from HSA and Na2Sn by allowing the reagents to react for 1 h at 37 °C. Different amounts of sodium polysulfides were allowed to react with HSA. Then, the HSA samples were incubated with EMSP solution, which was prepared at time of use, for 3 h at 37 °C. Based on the EMSP analyses, the level of S-sulfydration increased independently of the amount of sulfur (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, as shown in Fig. 1B, the Na2S3- or Na2S4-treatment enhanced the SSP4 (a fluorescence probe for sulfane sulfur) fluorescence intensity compared with the Na2S- or Na2S2-treatments, suggesting that SSP4 possibly reacted with the polysulfide of the protein in a non-linear manner (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Polysulfur binding to HSA by incubation with sodium polysulfide. (A) Valance dependency for adding sulfur to HSA with Na2Sn. Sulfane sulfur in Na2Sn-treated HSA samples were measured by EMSP. The values were subtracted from the untreated HSA. (B) SSP2 fluorescence intensity of Na2Sn-treated HSA samples was analyzed by SSP2. Each value represents the mean ± S.E. (n = 3). *p < 0.05 as compared with HSA.

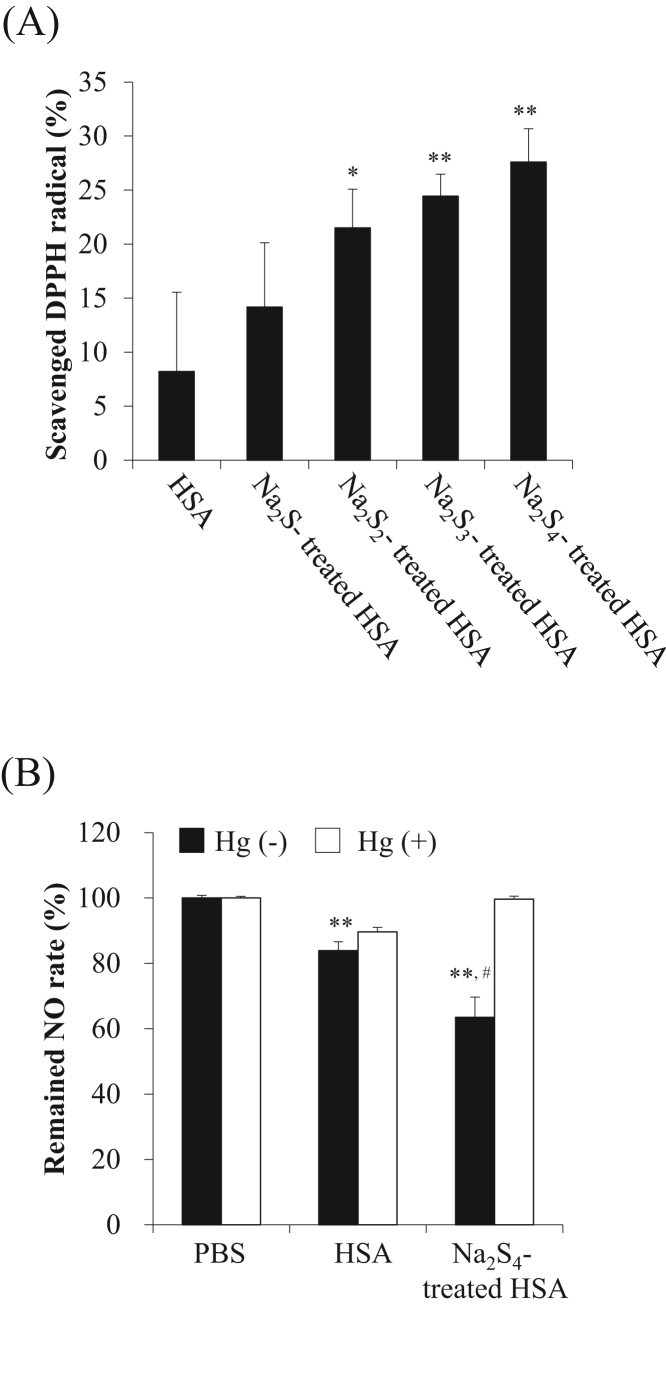

3.2. Antioxidant and NO suppressive effect of Na2S-treated HSA

We postulated that Na2Sn-treated HSA would suppress melanin production because of its antioxidant activity. Hence, a DPPH radical test [26], [27] was carried out to analyze the antioxidant activity in vitro. As a result, the Na2Sn-treated HSA had a significantly higher concentration of added sulfur (Fig. 2A). To elucidate the effect of NO, NOC7 (a NO donor) was co-incubated with Na2S4-treated HSA at 25 °C. After a 30 min period of incubation, the remaining NO concentration was quantitated by a Griess assay. As seen in the closed bars of Fig. 2B, the Na2S4-treated HSA scavenged significantly more NO compared with the control and HSA (Fig. 2B). Elemental mercury (Hg) is known to reduce SNO and release NO2-. When Hg was added to a solution of Na2S4-treated HSA, NO2- was released, suggesting that the Na2S4-treated HSA was scavenged via S-nitrosation.

Fig. 2.

Anti-oxidant properties of Na2Sn-treated HSA. (A) DPPH radical scavenging activity of HSA and Na2Sn-treated HSA. The concentration of DPPH radicals was measured by the oxidation of linoleic acid in the presence of HSA and Na2S4-treated HSA samples. (B) Scavenging of NO by Na2Sn-treated HSA. NO concentration was measured by a Griess assay after the reaction with Na2S4-treated HSA (50 μM) and NOC7 (200 μM). Each value represents the mean ± S.E. n = 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 as compared with control. #p < 0.05 as compared with HSA.

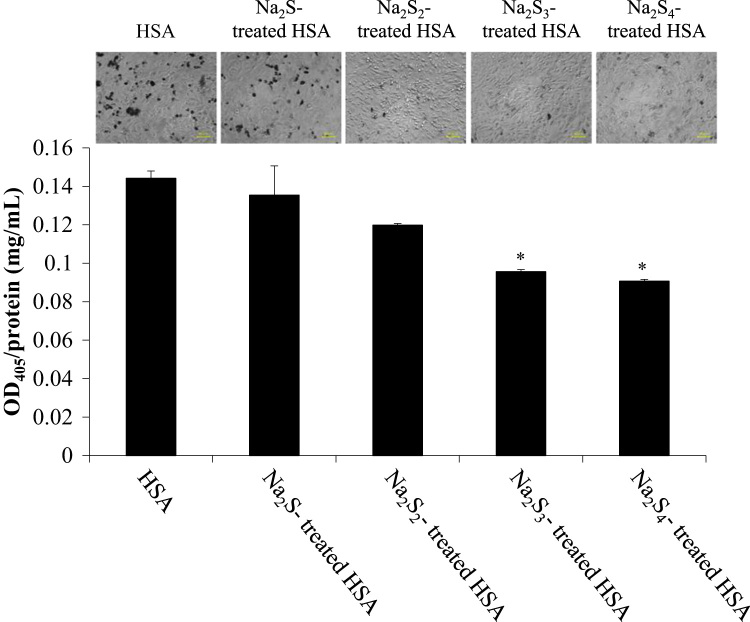

3.3. Melanin suppress effect of Na2Sn-treated HSA

B16 mice melanoma cells were cultured and melanin synthesis was promoted by adding tyrosine to the media. As shown in Fig. 3, the Na2Sn-treated HSA inhibited melanin synthesis and the inhibition was dependent on the sulfur content. Cell images of B16 melanoma cells after the application of the Na2Sn-treated HSA also demonstrated that Na2Sn-treated HSA decreased the ratio of production of melanin positive cells (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of Na2Sn-treated HSA on melanin synthesis in B16 melanoma cells. Melanin content was measured by the absorption of at 405 nm after incubating Na2Sn-treated HSA with 0.4 mM tyrosine and 10 mM NH4Cl for 72 h. Protein contents were analyzed by BCA protein Assay. Each value represents the mean ± S.E. n = 3. *p < 0.05 as compared with HSA. Cell image after the treatment with Na2Sn-treated HSA in B16 melanoma cells. The photos were taken after a 72 h treatment with Na2Sn-treated HSA in the presence of 0.4 mM tyrosine and 10 mM NH4Cl.

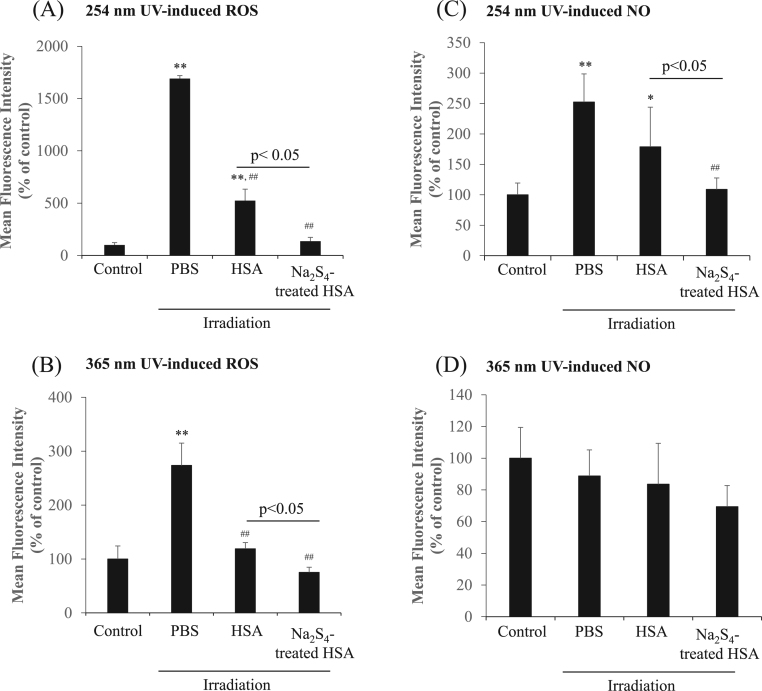

3.4. Antioxidant effect of Na2S4-treated HSA with irradiation of UV

To examine whether the Na2Sn-treated HSA suppressed the formation of UV-induced ROS or NO, an oxidative stress test was performed using B16 melanoma cells as models. ROS production by Na2S4-treated HSA in B16 melanoma cells by irradiation with 2 different UV devices for 15 min was measured by CMH2-DCF-DA. The findings indicate that the Na2S4-treated HSA caused a significant decrease in the fluorescence of CMH2-DCF-DA to PBS and HSA by irradiation at 254 nm and 365 nm (Fig. 4AB). Conversely, the Na2S4-treated HSA also suppressed the production of NO in B16 melanoma cells by irradiation with 254 nm UV (Fig. 4CD). These results indicate that Na2Sn-treated HSA suppresses melanin synthesis by inhibiting ROS and NO produced by UV irradiation.

Fig. 4.

ROS and NO scavenging effects of Na2S4-treated HSA under UV irradiation. ROS in B16 melanoma cells was detected by CM-H2DCF-DA in the presence of HSA and Na2S4-treated HSA with 15 min irradiation of 2 different UV, (A) 254 nm, (B) 365 nm. Each value represents the mean ± S.E. n = 3. **p < 0.01 as compared with control. ##p < 0.01 as compared with HSA. NO in B16 melanoma cells was detected by DAF-FM-DA in the presence of HSA and Na2S4-treated HSA after irradiation for 15 min with 2 different wavelengths, (C) 254 nm, (D) 365 nm. NO synthesis was measured by DAF-FM-DA. Each value represents the mean ± S.E. n = 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 as compared with control. ##p < 0.01 as compared with PBS.

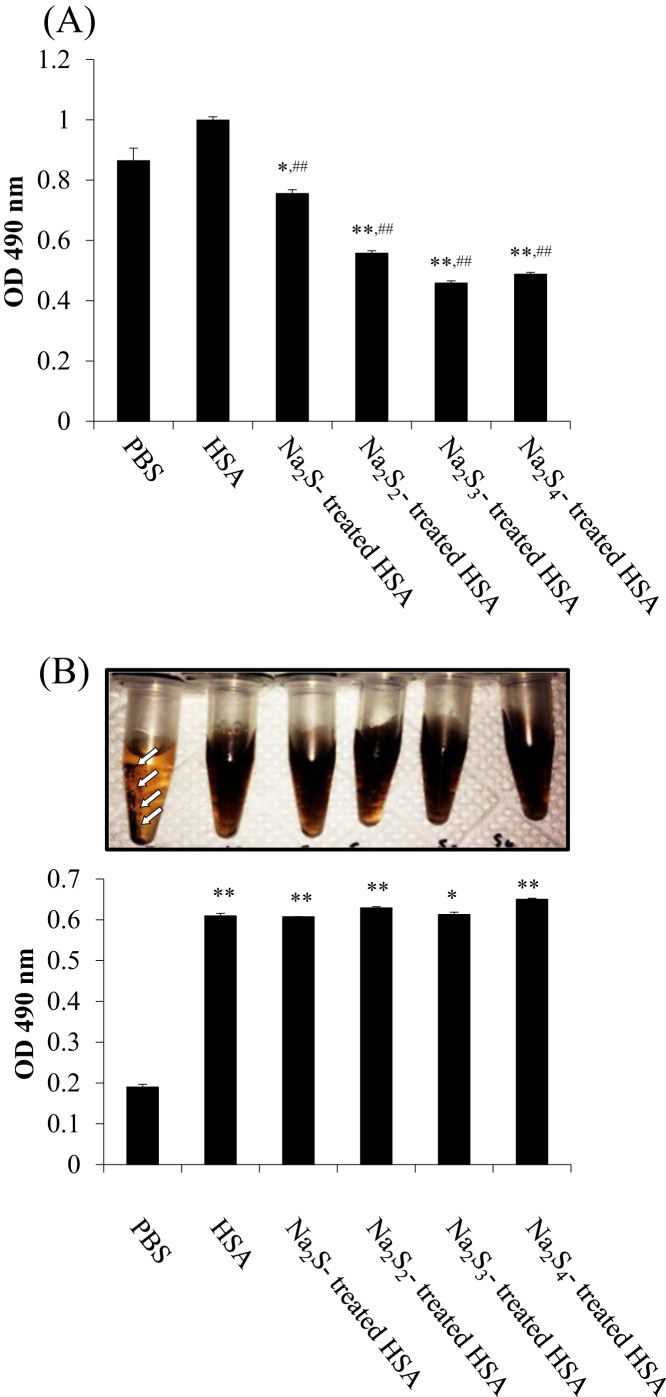

3.5. Direct suppression of tyrosinase and melanin aggregation by Na2Sn-treated HSA

Some commercial anti-melanin agents are known to directly inhibit tyrosinase activity. Thus, we tested whether the Na2Sn-treated HSA altered the activity of tyrosinase. The findings indicated that the Na2Sn-treated HSA inhibited mushroom tyrosinase to a greater extent than non-treated HSA (Fig. 5A). After being generated, melanin readily undergoes aggregation and induces medulla formation [28]. Therefore, we next addressed the issue of whether Na2Sn-treated HSA inhibits the aggregation of melanin. Consequently, when tyrosinase and L-DOPA were incubated together for 3 h, melanin pigments became aggregated, but the Na2Sn-treated HSA prevented the aggregation (Fig. 5B). On the one hand, HSA was also found to inhibit aggregation, indicating that HSA itself could prevent the binding of L-DOPA to tyrosinase.

Fig. 5.

Na2Sn-treated HSA inhibits the oxidation of L-DOPA and melanin aggregation. (A) Melanin synthesis from tyrosinase and L-DOPA in the presence of HSA and Na2Sn–treated HSA. Tyrosinase and samples were mixed and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. After the reaction, L-DOPA was added and the incubation continued for an additional 30 min (B) After 3 h, the mixture was centrifuged for 20,000 g, 15 min. Non-aggregated melanin in supernatant was measured using OD 490 nm. Tyrosinase and L-DOPA were co-incubated for 10 min and added HSA samples. White arrow showed the aggregation. Each value represents the mean ± S.E. n = 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 as compared with PBS. ##p < 0.01 as compared with HSA.

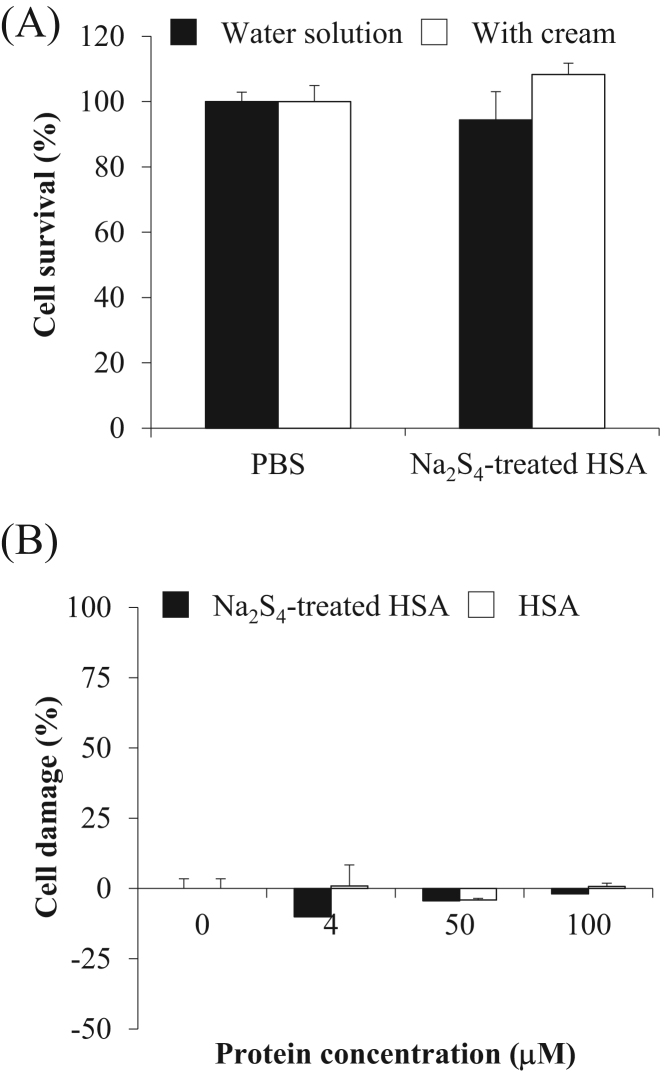

3.6. Safety test of Na2Sn-treated HSA using 3D cultured human skin

Skin irritation tests for the Na2S4-treated HSA was performed using 3D cultured human skin cells according to OECD guidelines. As a result, the numbers of surviving cells were not decreased by Na2S4-treated HSA with/without the use of a topical cream (Fig. 6A). The use of an LDH cytotoxicity detection kit also revealed that skin cells were not damaged by the Na2S4-treated HSA (Fig. 6B). These data indicated that Na2Sn-treated HSA is very safe for use against human skin under the concentrations examined in this study.

Fig. 6.

Safety testing of Na2S4-treated HSA for 3D cultured human epidermis. (A) Cell survival tests were performed using Autologous Cultured Epidermis kit with in PBS solution (white column) and in cream (black). (B) Cell damage tests were performed using an LDH Cytotoxicity Detection Kit. Each value represents the mean ± S.E. n = 3.

4. Discussion

Melanin is synthesized by the oxidation of tyrosine. Tyrosine is oxidized to L-DOPA, and then dopaquinone by the action of tyrosinase. Dopaquinone is spontaneously oxidized to melanin. Melanin induces the formation of black pigments and freckles, but also plays a role in protecting the skin from being damaged by UV radiation. In human skin, melanocytes produce ROS and NO when stimulated by UV radiation [2], [29], [30]. ROS promotes melanin synthesis by activating tyrosinase via the action of ATP synthase, phenylalanine hydroxylase, and the phosphorylation of MAPKs [31], [32]. NO activates tyrosinase via increasing the cellular level of cGMP [6]. Therefore, ROS and NO scavengers are considered to be anti-melanogenesis agents. Here, we investigated the anti-melanin synthesis effect of Na2Sn-treated HSA. Na2Sn-treated HSA strongly suppressed the cellular levels of ROS and NO produced by UV radiation (Fig. 4). Furthermore, Na2Sn-treated HSA had a direct effect on inhibiting the action of tyrosinase (Fig. 5A) and the aggregation of melanin (Fig. 5B). We were not able to clarify the mechanism for how sulfane sulfur was transferred from the Na2Sn-treated HSA to a cell. Therefore, the nature of how the direct effects of Na2Sn-treated HSA function remain unclear. Yamashita et al. demonstrated that dopaquinone binds to thiol proteins via cysteine residues [33]. Taken together, the inhibition of melanin aggregation by HSA and Na2Sn-treated HSA may also involve the formation of disulfide bonds with dopaquinone or melanin. On the other hand, tyrosinase inhibition was dependent on the content of added sulfur (Fig. 5A). GSH is known to bind tyrosinase and decrease its activity [34]. Because S-sulfhydrated cysteine has a stronger reactivity than normal cysteine [11], glutathione persulfide (GSSH) may inhibit the action of tyrosinase more than GSH. Further studies regarding the issue of whether Na2Sn-treated HSA increases intracellular GSSH is needed in the future.

ROS are produced by UV irradiation or external stress induce signs of aging, not only in the form of melanin synthesis but also by the appearance of wrinkles and sagging skin, caused by DNA damage and the formation of cross linked collagen. It is also known that ROS are an aggravating factor in various types of inflammation such as pimples and psoriasis. Various skin whitening agents, such as tranexamic acid [35] and arbutin [36], have been designed to address these issues. However, these compounds only inhibit melanin synthesis and have no effect on oxidative stress. Thus, the risks of ROS-induced toxicity remained. An advantage of using Na2Sn-treated HSA is that it efficiently scavenges ROS (Fig. 2, Fig. 4).

Hydrogen sulfide has been studied as a third essential molecule after nitric oxide and carbon monoxide. Therapeutic effects of hydrogen sulfide have been shown to be applicable to the treatment of ischemia/reperfusion [37], atherosclerosis [38], sepsis [39] and high fat diet-induced toxicity [40]. In addition, hydropersulfide has a higher activity than hydrogen sulfide. For example, Na2S4 effectively detoxifies methyl mercury and inhibits the differentiation of neuroblastoma cells, while Na2S does not [12], [41]. Therefore, not only a skin whitening effect but also other positive effects of Na2Sn-treated HSA are possible.

In conclusion, we reported on the development of a novel RSS delivery system using serum albumin as a stable carrier. Reactive sulfur, when combined with HSA, had a stronger anti-oxidant effect than HSA and inhibited melanin synthesis in melanoma cells. The mechanism of anti-melanogenesis involves not only ROS and NO scavenging, but also suppression of tyrosinase activity and melanin aggregation. Hence, Na2Sn-treated HSA has considerable potential for use as a safe skin whitening agent.

Competing financial interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by a Program for Leading Graduate Schools “HIGO (Health life science: Interdisciplinary and Glocal Oriented) Program. This work was supported, in part, by Grants-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (KAKENHI KIBAN (C) 15K08076), Japan. The work was also, in part, supported by grants from the Takeda Science Foundation. This study was supported by Yamada Research Grant, JINSEI innovation and a research program for the development of intelligent Tokushima artificial exosome (iTEX) from Tokushima University.

Author contributions

1. Study conception and design: M.I., Y.I., T.I., M.O., T.O.; 2. Acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation of data: M.I., Y.I., R.K., N.T.; 3. Drafting/revision of the work for intellectual content and context: M.I., Y.I., V.C., H.W., T.S. T.I., M.O., T.O.; 4. Final approval and overall responsibility for the published work; Y.I., V.C., T.I., M.O., T.O.

Contributor Information

Yu Ishima, Email: ishima.yuu@tokushima-u.ac.jp.

Toru Maruyama, Email: tomaru@gpo.kumamoto-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Simon H.U., Haj-Yehia A., Levi-Schaffer F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis. 2000;5:415–418. doi: 10.1023/a:1009616228304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner M., Hearing V.J. The protective role of melanin against UV damage in human skin. Photochem. PhotoBiol. 2008;84 doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samson N., Fink B., Matts P. Interaction of skin color distribution and skin surface topography cues in the perception of female facial age and health. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2011;10:78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2010.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korner A., Pawelek J. Mammalian tyrosinase catalyzes three reactions in the biosynthesis of melanin. Science. 1982;217:1163–1165. doi: 10.1126/science.6810464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim D.S., Kim S.Y., Chung J.H., Kim K.H., Eun H.C., Park K.C. Delayed ERK activation by ceramide reduces melanin synthesis in human melanocytes. Cell. Signal. 2002;14:779–785. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palumbo A., Poli A., Di Cosmo A., D’Ischia M. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor stimulation activates tyrosinase and promotes melanin synthesis in the ink gland of the cuttlefish Sepia officinalis through the nitric oxide/cGMP signal transduction pathway. A novel possible role for glutamate as physiologic activator of melanogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:16885–16890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909509199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamura T., Onishi J., Nishiyama T. Antimelanogenic activity of hydrocoumarins in cultured normal human melanocytes by stimulating intracellular glutathione synthesis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2002;294:349–354. doi: 10.1007/s00403-002-0345-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ying J., Clavreul N., Sethuraman M., Adachi T., Cohen R.A. Thiol oxidation in signaling and response to stress: detection and quantification of physiological and pathophysiological thiol modifications. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;43:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davids L.M., van Wyk J.C., Khumalo N.P. Intravenous glutathione for skin lightening: inadequate safety data, South African Med. S. Afr. Med. J. 2016;106:782–786. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i8.10878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ida T., Sawa T., Ihara H., Tsuchiya Y., Watanabe Y., Kumagai Y., Suematsu M., Motohashi H., Fujii S., Matsunaga T., Yamamoto M., Ono K., Devarie-Baez N.O., Xian M., Fukuto J.M., Akaike T. Reactive cysteine persulfides and S-polythiolation regulate oxidative stress and redox signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014;111:7606–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321232111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuevasanta E., Möller M.N., Alvarez B. Biological chemistry of hydrogen sulfide and persulfides. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abiko Y., Yoshida E., Ishii I., Fukuto J.M., Akaike T., Kumagai Y. Involvement of reactive persulfides in biological bismethylmercury sulfide formation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2015;28:1301–1306. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nahdi A., Hammami I., Brasse-Lagnel C., Pilard N., Hamdaoui M.H., Beaumont C., El May M. Influence of garlic or its main active component diallyl disulfide on iron bioavailability and toxicity. Nutr. Res. 2010;30:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sleep D. Albumin and its application in drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2015;12:793–812. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.993313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elsadek B., Kratz F. Impact of albumin on drug delivery - New applications on the horizon. J. Control. Release. 2012;157:4–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugio S., Kashima A., Mochizuki S., Noda M., Kobayashi K. Crystal structure of human serum albumin at 2.5 A resolution. Protein Eng. 1999;12:439–446. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.6.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qi J., Zhang Y., Gou Y., Lee P., Wang J., Chen S., Zhou Z., Wu X., Yang F., Liang H. Multidrug delivery systems based on human serum albumin for combination therapy with three anticancer agents. Mol. Pharm. 2016;13:3098–3105. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gryzunov Y.A., Arroyo A., Vigne J.-L., Zhao Q., Tyurin V.A., Hubel C.A., Gandley R.E., Vladimirov Y.A., Taylor R.N., Kagan V.E. Binding of fatty acids facilitates oxidation of cysteine-34 and converts copper–albumin complexes from antioxidants to prooxidants. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003;413:53–66. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marley R., Patel R.P., Orie N., Ceaser E., Darley-Usmar V., Moore K. Formation of nanomolar concentrations of S-nitroso- albumin in human plasma By nitric oxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;31:688–696. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00627-x. 〈http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd = Retrieve&db = PubMed&dopt = Citation&list_uids = 11522454〉 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishima Y., Akaike T., Kragh-Hansen U., Hiroyama S., Sawa T., Suenaga A., Maruyama T., Kai T., Otagiri M. S-nitrosylated human serum albumin-mediated cytoprotective activity is enhanced by fatty acid binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:34966–34975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807009200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katayama N., Nakajou K., Ishima Y., Ikuta S., Yokoe J., Yoshida F., Suenaga A., Maruyama T., Kai T., Otagiri M. Nitrosylated human serum albumin (SNO-HSA) induces apoptosis in tumor cells. Nitric Oxide. 2010;22:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogasawara Y., Isoda S., Tanabe S. Antioxidant effects of albumin-bound sulfur in lipid peroxidation of rat liver microsomes. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1999;22:441–445. doi: 10.1248/bpb.22.441. 〈http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10375161〉 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen W., Liu C., Peng B., Zhao Y., Pacheco A., Xian M. New fluorescent probes for sulfane sulfurs and the application in bioimaging. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:2892–2896. doi: 10.1039/C3SC50754H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikeda M., Ishima Y., Shibata A., Chuang V.T.G. Quantitative determination of polysul fi de in albumins, plasma proteins and biological fluid samples using a novel combined assays approach. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2017:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akaike T., Inoue K., Okamoto T., Nishino H., Otagiri M., Fujii S., Maeda H. Nanomolar quantification and identification of various nitrosothiols by high performance liquid chromatography coupled with flow reactors of metals and Griess reagent. J. Biochem. 1997;122:459–466. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dinis T.C.P., Madeira V.M.C., Almeida L.M. Action of phenolic derivatives (Acetaminophen, Salicylate, and 5-Aminosalicylate) as inhibitors of membrane lipid peroxidation and as peroxyl radical scavengers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994;315:161–169. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brand-Williams W., Cuvelier M.E., Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 1995;28:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarangarajan R., Apte S.P. Melanin aggregation and polymerization: possible implications in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Res. 2005;37:136–141. doi: 10.1159/000085533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swalwell H., Latimer J. Investigating the role of melanin in UVA/UVB-and hydrogen peroxide-induced cellular and mitochondrial ROS production and mitochondrial DNA damage in human melanoma cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012;52:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roméro-Graillet C., Aberdam E., Clément M., Ortonne J.P., Ballotti R. Nitric oxide produced by ultraviolet-irradiated keratinocytes stimulates melanogenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 1997;99:635–642. doi: 10.1172/JCI119206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim H.E., Lee S.G. Induction of ATP synthase β by H2O2 induces melanogenesis by activating PAH and cAMP/CREB/MITF signaling in melanoma cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013;45:1217–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeayeng S., Wongkajornsilp A., Slominski A.T., Jirawatnotai S. Free radical biology and medicine Nrf2 in keratinocytes modulates UVB-induced DNA damage and apoptosis in melanocytes through MAPK signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017;108:918–928. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ito S., Ojika M., Yamashita T., Wakamatsu K. Tyrosinase-catalyzed oxidation of rhododendrol produces 2-methylchromane-6,7-dione, the putative ultimate toxic metabolite: implications for melanocyte toxicity. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:744–753. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuki M., Watanabe T., Ogasawara A., Mikami T., Matsumoto T. Inhibitory mechanism of melanin synthesis by glutathione. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2008;128:1203–1207. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.128.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li D., Shi Y., Li M., Liu J., Feng X. Tranexamic acid can treat ultraviolet radiation-induced pigmentation in guinea pigs. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2010;20:289–292. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim Y.J., Lee E.H., Kang T.H., Ha S.K., Oh M.S., Kim S.M., Yoon T.J., Kang C., Park J.H., Kim S.Y. Inhibitory effects of arbutin on melanin biosynthesis of α-melanocyte stimulating hormone-induced hyperpigmentation in cultured brownish guinea pig skin tissues. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2009;32:367–373. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-1309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao Y., Yao X., Zhang Y., Li W., Kang K., Sun L., Sun X. The protective role of hydrogen sulfide in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion-induced injury in diabetic rats. Int. J. Cardiol. 2011;152:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du J., Huang Y., Yan H., Zhang Q., Zhao M., Zhu M., Liu J., Chen S.X., Bu D., Tang C., Jin H. Hydrogen sulfide suppresses oxidized low-density lipoprotein (Ox-LDL)-stimulated monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 generation from macrophages via the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:9741–9753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.517995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferlito M., Wang Q., Fulton W.B., Colombani P.M., Marchionni L., Fox-Talbot K., Paolocci N., Steenbergen C. Hydrogen sulfide [corrected] increases survival during sepsis: protective effect of CHOP inhibition. J. Immunol. 2014;192:1806–1814. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hwang S.-Y., Sarna L.K., Siow Y.L., High-fat K.O. diet stimulates hepatic cystathionine β-synthase and cystathionine γ-lyase expression. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2013;91:913–919. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2013-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koike S., Shibuya N., Kimura H., Ishii K., Ogasawara Y. Polysulfide promotes neuroblastoma cell differentiation by accelerating calcium influx. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;459:488–492. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]