Abstract

Airway hyperreactivity is a hallmark feature of asthma and can be precipitated by airway insults, such as ozone exposure or viral infection. A proposed mechanism linking airway insults to airway hyperreactivity is augmented cholinergic transmission. In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that acute potentiation of cholinergic transmission is sufficient to induce airway hyperreactivity. We atomized the cholinergic agonist bethanechol to neonatal piglets and forty-eight hours later measured airway resistance. Bethanechol-treated piglets displayed increased airway resistance in response to intravenous methacholine compared to saline-treated controls. In the absence of an airway insult, we expected to find no evidence of airway inflammation; however, transcripts for several asthma-associated cytokines, including IL17A, IL1A, and IL8, were elevated in the tracheas of bethanechol-treated piglets. In the lungs, prior bethanechol treatment increased transcripts for IFNγ and its downstream target CXCL10. These findings suggest that augmented cholinergic transmission is sufficient to induce airway hyperreactivity, and raise the possibility that cholinergic-mediated regulation of pro-inflammatory pathways might contribute.

Keywords: airway hyperreactivity, piglet, cholinergic, inflammation

Introduction

Airway hyperreactivity is a common feature of asthma and is characterized by exaggerated airway narrowing in response to a variety of stimuli [1]. It is well established that airway insults (e.g. viral infection, ozone inhalation, antigen challenge) can precipitate or worsen asthma-like symptoms, including airway hyperreactivity, in “normal” (e.g. non-reactive) and asthmatic airways [2–4]. Enhanced cholinergic transmission is a proposed mechanism mediating insult-induced airway hyperreactivity [5]. Specifically, evidence suggests that inflammation inhibits presynaptic cholinergic receptors on nerve terminals innervating the airway, resulting in enhanced acetylcholine release, and augmented bronchoconstriction [3,4].

We hypothesized that if enhanced cholinergic transmission is a key factor mediating airway hyperreactivity [5], then cholinergic stimulation in the absence of an airway insult might also be sufficient to induce airway hyperreactivity. To examine this possibility, we challenged neonatal piglets with the non-selective muscarinic receptor agonist bethanechol. Because previous studies have shown that airway hyperreactivity can occur as early as 24–48 hours following an airway insult [3,4], we measured airway resistance 48 hours later. We selected the piglet model due to its similar anatomy, physiology, and development compared to humans [6], as well as our extensive expertise with the model [7,8].

Materials and methods

Animals and Ethic Statement

A total of 16 piglets (Landrace/Yorkshire breed, 2–3 days of age) were fed commercial milk replacer (Soweena Litter Life), and allowed a 36–48-hour to acclimate before interventions began. The University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures. Procedures were completed in accordance with federal policies and guidelines.

Airway instillation

After acclimation, piglets were anesthetized with 20mg/kg ketamine and 2.0mg/kg xylazine (Henry Schein Animal Health). Airways were accessed with a laryngoscope. A laryngotracheal atomizer (MADgic) was passed directly beyond the vocal folds to aerosolize either a 500 µl of 0.9% saline control or 8 mg/ml bethanechol chloride (Selleckchem) in 0.9% saline solution to the airway. The dose selected has previously been shown to acutely increase airway resistance in piglets [9]. Of the total 16 piglets that underwent instillation, 6 piglets were simply observed and euthanized. Histological specimens were examined from these piglets to evaluate overall tolerability of the bethanechol paradigm.

FlexiVent

Forty-eight hours post instillation, animals (n =10) were anesthetized with ketamine (20mg/kg) and xylazine (2.0mg/kg) and intravenous propofol (2mg/kg) (Henry Schein Animal Health). A tracheostomy was performed [10] and a cuffless endotracheal tube (Coviden, 4.0 mm OD) was placed. Piglets were connected to a flexiVent system (SCIREQ), and paralytic (rocuronium bromide, Novaplus) was administered. Piglets were ventilated at 60 breaths/min at a volume of 10ml/kg body mass. Increasing doses of methacholine were administered intravenously. Measurements for each dose were taken at 10 sec intervals over the course of approximately 5 mins. Airway resistance was measured using a single compartment model.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

RNA from the trachea was isolated using RNeasy Lipid Tissue kit (Qiagen), with DNase digestion using RNase-free DNase (Qiagen). RNA concentrations were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA (1000 ng) was reverse transcribed using Superscript VILO Master Mix (Thermofisher). Briefly, RNA and master mix were incubated for 10 mins at 25°C, followed by 60 mins at 42°C, followed by 5 mins at 85°C. Inflammatory-directed quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR arrays (Qiagen, PASS-011ZF) were completed according the manufacturer’s instructions, using fast SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems). The qRT-PCR array has 5 housekeeping genes that can be used to for quantification with standard ΔΔCT methods [8]. For inflammatory-directed qRT-PCR arrays, RNA was reversed transcribed for each animal. For analysis, equal amounts of individual tracheal cDNA was pooled for each treatment group (n = 5 control piglets, n = 5 bethanechol piglets). Three separate sets of pooled cDNA per group were generated and used for qRT-PCR arrays. Statistical analysis for tracheal tissues was performed on the technical replicates (n = 3). To confirm the array findings, we also performed qRT-PCR for IL17A (Ss03391803_m1), IL8 (Ss03392437_m1), and IL1a (Ss03391335_m1) with β-actin (Ss0337653_uH) as a housekeeping gene on the individual tracheal cDNA (n = 5 bethanechol, n = 5 control) using TaqMan Universal PCR master mix II, no UNG (Applied Biosystems) and primer and probe sets from ThermoFisher. Standard ΔΔCT methods were used for analysis [8]. For inflammatory-directed qRT-PCR arrays of the lung, RNA was reversed transcribed for each animal and assayed separately (n = 5 saline-treated piglets, n = 5 bethanechol-treated piglets). Statistical analysis was performed on the individual qRT-PCR arrays. To examine muc5AC, muc5B transcript abundance, we utilized previously published primer sequences [11]. FoxJ1 primers were developed with the following sequences: FoxJ1 forward 5’-ATA TGG CGG AGA GCT GGC TA-3’; FoxJ1 reverse 5’-CCT TGG CGT TGA GAA TGG AG-3’. Actin was used as a housekeeping gene utilizing previously described primers sequences [8]. Data were acquired using fast SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems). Standard ΔΔCT methods were used for analysis [8]. Melting curves were implemented for all SYBR green primer sets. All PCR was performed on a Lightcycler 480 (Roche).

Chemicals

Bethanechol chloride (Selleckchem) was dissolved in 0.9% saline. Acetyl-beta-methacholine-chloride (Sigma) was dissolved in 0.9% saline for flexiVent studies.

Bronchoalveolar lavage, ELISAs, and cell count analysis

The caudal left lung of each piglet was excised and the main bronchus cannulated; three sequential 5-ml lavages of 0.9% sterile saline were administered. The recovered material was pooled, spun at 500 × g, and supernatant removed. Cells were counted on a hemocytometer. ELISAs for porcine IL17A (ThermoFisher, ESIL17A), IL8 (R&D Systems, P8000), CXL10 (Ray Biotech, ELP-IP10-1) and IFNγ (ThermoFisher, KSC4021) were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and quantified with an accuSkan FC (Fisher Scientific). The lower limit of sensitivity was 14pg/ml, 6.7 pg/ml, 0.4ng/ml, 2pg/ml for IL17A, IL8, CXCL10, and IFNγ, respectively.

Histology

Trachea and lung tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (~7–10 days) then routinely processed, paraffin-embedded, sectioned (~4 µm) and stained with H&E and dPAS stains. Tissues were examined by a pathologist (DKM) masked to conditions. Digital images were collected with specialized equipment (BX51 microscope and DP73 digital camera, Olympus) and software (CellSens Pathology Edition, Olympus). Indices of inflammation were assigned as previously described [12]. Histological examination included 3 animals per treatment group that did not undergo flexiVent procedures, in addition to those that did.

Statistical Analysis

A two-way ANOVA was performed to assess airway resistance in response to intravenous methacholine and to assess inflammation via quantitative real-time PCR arrays. For airway resistance, a Sidak’s multiple comparison test was applied. For the PCR arrays, a false discovery rate using the two-stage step-up method of Benjamin, Krieger, and Yekutieli was applied. An unpaired Student’s t-test was used to assess basal airway resistance, cytokine concentrations, and TaqMan primer and probe qPCR. For histopathological scoring, a non-parametric Mann Whitney test was performed between groups. All tests were carried out using GraphPad Prism 7.0a. Statistical significance was determined as p<0.05.

Results and discussion

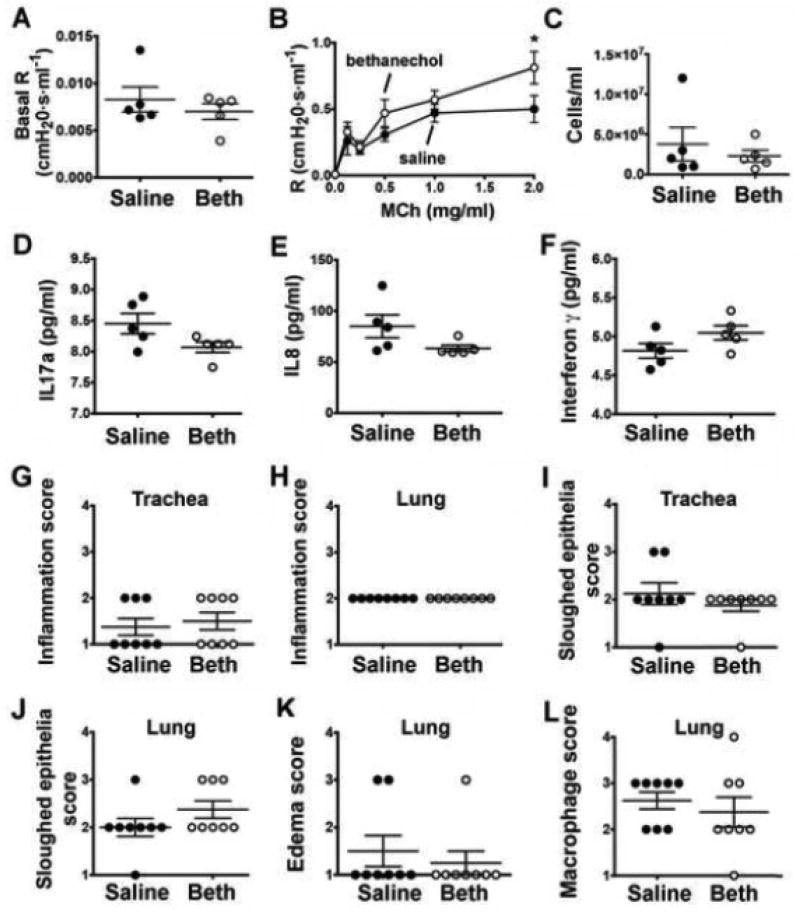

We first examined airway mechanics. Basal airway resistance measurements were not different between treatment groups (Figure 1A). Piglets that were exposed to bethanechol 48 hours prior to testing exhibited greater airway resistance in response to intravenous methacholine compared to saline controls (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Airway resistance and inflammation markers in neonatal piglets forty-eight hours post bethanechol challenge. (A) Baseline airway resistance prior to administering methacholine. (B) Airway resistance in response to increasing doses of methacholine; n = 5 piglets each group. (C) Number of cells/ml observed in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of saline-treated and bethanechol-treated piglets. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid concentrations of IL17A (D) IL8 (E) and IFNγ mediated. Histological scoring by a pathologist masked to treatment for inflammation (G, H), sloughed epithelium (I, J), edema (K) and macrophages (L). Scoring parameters for inflammation, edema and sloughed epithelium are as follows: 1= within normal limits; 2 = mild, uncommon, focal; 3 = moderate, multifocal; 4 = extensive, coalescing changes. Scoring parameters for macrophages are as follows: 1= within normal limits; 2 = accumulation within airway (<33%); 3 = accumulation within airway (34–66%); 4 = accumulation within airway (>67%). For panels A-F, n = 5 piglets per group; for panels G-L, n = 8 piglets per group. Data are mean ± SEM. For *, p < 0.05 for treatment effect using a two-way ANOVA. An unpaired Student’s t-test was used to assess basal airway resistance and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid cells cytokine concentrations. A non-parametric Mann Whitney test was performed to examine histological scoring. All tests were carried out using Prism 7.0a. Abbreviations: R, resistance; MCh, methacholine; Beth, bethanechol; IL17a, interleukin 17a; IL8, interleukin 8; CXCL10, C-X-C motif chemokine 10; IFNγ, interferon gamma.

Previous studies suggest that airway insults augment cholinergic transmission secondary to inflammation [3,4]. Because there was no inciting airway insult, we anticipated airway inflammation to be absent in the bethanechol-treated piglets. However, inflammatory-directed qRT-PCR arrays revealed elevated transcripts for several pro-inflammatory markers in the tracheas of bethanechol-treated piglets compared to saline controls (Table 1). When correcting for false discovery rate (FDR), elevations in three cytokines (IL17A, q value < 0.0001; IL1A, q value = 0.031; IL8, q value < 0.0001) were statistically significant (Table 1). Primer and probe sets with a β-actin as a reference gene confirmed elevations in IL17A, IL8, and IL1A (Table 1, gray shaded rows). Because the lungs of asthmatics are often affected by inflammation [13], we also examined lung tissues with inflammatory-directed quantitative real-time PCR arrays. Doing so revealed that prior bethanechol treatment increased mRNA expression of IFNγ (q value < 0.0001) and its downstream target CXCL10 (q value = 0.0047) (Table 2).

Table 1.

List of transcripts queried through inflammatory-directed PCR arrays in piglet tracheal tissues

| saline | Bethanechol | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Name | Mean | SEM | n | Mean | SEM | n | Mean Diff. | q value | P Value |

| AIMP1 | 1 | 0.090 | 3 | 1.178 | 0.031 | 3 | −0.1789 | 0.9966 | 0.8458 |

| BMP2 | 1 | 0.079 | 3 | 1.139 | 0.165 | 3 | −0.1393 | 0.9966 | 0.8797 |

| C5 | 1 | 0.123 | 3 | 1.382 | 0.061 | 3 | −0.3823 | 0.9966 | 0.6778 |

| CCL1 | 1 | 0.088 | 3 | 0.882 | 0.277 | 3 | 0.1179 | 0.9966 | 0.898 |

| CCL17 | 1 | 0.238 | 3 | 0.847 | 0.278 | 3 | 0.1529 | 0.9966 | 0.868 |

| CCL2 | 1 | 0.060 | 3 | 1.429 | 0.114 | 3 | −0.4296 | 0.9966 | 0.6406 |

| CCL20 | 1 | 0.261 | 3 | 1.540 | 0.272 | 3 | −0.5407 | 0.9966 | 0.5568 |

| CCL21 | 1 | 0.136 | 3 | 0.886 | 0.116 | 3 | 0.1135 | 0.9966 | 0.9018 |

| CCL22 | 1 | 0.263 | 3 | 0.506 | 0.091 | 3 | 0.4938 | 0.9966 | 0.5915 |

| CCL3L1 | 1 | 0.135 | 3 | 3.141 | 0.351 | 3 | −2.142 | 0.3242 | 0.0204 |

| CCL4 | 1 | 0.081 | 3 | 2.330 | 0.101 | 3 | −1.331 | 0.9966 | 0.1487 |

| CCL5 | 1 | 0.086 | 3 | 1.336 | 0.075 | 3 | −0.337 | 0.9966 | 0.7142 |

| CCL8 | 1 | 0.201 | 3 | 2.043 | 0.498 | 3 | −1.043 | 0.9966 | 0.2573 |

| CCR1 | 1 | 0.119 | 3 | 1.180 | 0.211 | 3 | −0.1807 | 0.9966 | 0.8443 |

| CCR10 | 1 | 0.177 | 3 | 1.053 | 0.116 | 3 | −0.05312 | 0.9966 | 0.954 |

| CCR2 | 1 | 0.325 | 3 | 1.306 | 0.294 | 3 | −0.3062 | 0.9966 | 0.7393 |

| CCR3 | 1 | 0.398 | 3 | 0.936 | 0.397 | 3 | 0.06304 | 0.9966 | 0.9454 |

| CCR4 | 1 | 0.222 | 3 | 2.091 | 0.192 | 3 | −1.092 | 0.9966 | 0.2359 |

| CCR5 | 1 | 0.226 | 3 | 1.291 | 0.263 | 3 | −0.2918 | 0.9966 | 0.7512 |

| CCR7 | 1 | 0.049 | 3 | 1.083 | 0.163 | 3 | −0.0831 | 0.9966 | 0.928 |

| CD40LG | 1 | 0.182 | 3 | 1.491 | 0.169 | 3 | −0.4917 | 0.9966 | 0.5931 |

| CD70 | 1 | 0.173 | 3 | 1.585 | 0.167 | 3 | −0.5859 | 0.9966 | 0.5244 |

| CSF1 | 1 | 0.076 | 3 | 1.159 | 0.147 | 3 | −0.1596 | 0.9966 | 0.8623 |

| CSF2 | 1 | 0.118 | 3 | 2.626 | 0.278 | 3 | −1.626 | 0.7294 | 0.0778 |

| CSF3 | 1 | 0.067 | 3 | 0.953 | 0.370 | 3 | 0.04611 | 0.9966 | 0.96 |

| CXCL10 | 1 | 0.003 | 3 | 1.096 | 0.253 | 3 | −0.09634 | 0.9966 | 0.9166 |

| CXCL11 | 1 | 0.110 | 3 | 0.964 | 0.272 | 3 | 0.03556 | 0.9966 | 0.9692 |

| CXCL12 | 1 | 0.023 | 3 | 0.902 | 0.054 | 3 | 0.09731 | 0.9966 | 0.9158 |

| CXCL2 | 1 | 0.074 | 3 | 1.641 | 0.184 | 3 | −0.6414 | 0.9966 | 0.4858 |

| CXCL9 | 1 | 0.202 | 3 | 1.274 | 0.219 | 3 | −0.2749 | 0.9966 | 0.7651 |

| CXCR2 | 1 | 0.153 | 3 | 2.591 | 0.645 | 3 | −1.591 | 0.7294 | 0.0844 |

| CXCR4 | 1 | 0.088 | 3 | 1.302 | 0.100 | 3 | −0.3025 | 0.9966 | 0.7423 |

| FASLG | 1 | 0.073 | 3 | 1.789 | 0.081 | 3 | −0.7899 | 0.9966 | 0.3908 |

| FLT3LG | 1 | 0.086 | 3 | 0.930 | 0.071 | 3 | 0.06991 | 0.9966 | 0.9394 |

| IFNG | 1 | 0.405 | 3 | 1.340 | 0.482 | 3 | −0.341 | 0.9966 | 0.7109 |

| IL10 | 1 | 0.112 | 3 | 1.821 | 0.125 | 3 | −0.8215 | 0.9966 | 0.3722 |

| IL10RA | 1 | 0.057 | 3 | 1.206 | 0.150 | 3 | −0.2066 | 0.9966 | 0.8224 |

| IL10RB | 1 | 0.134 | 3 | 1.213 | 0.326 | 3 | −0.2132 | 0.9966 | 0.8167 |

| IL12B | 1 | 0.158 | 3 | 1.132 | 0.336 | 3 | −0.1329 | 0.9966 | 0.8852 |

| 1L13 | 1 | 0.327 | 3 | 0.557 | 0.153 | 3 | 0.4428 | 0.9966 | 0.6304 |

| IL15 | 1 | 0.149 | 3 | 0.977 | 0.313 | 3 | 0.02237 | 0.9966 | 0.9806 |

| IL16 | 1 | 0.106 | 3 | 0.947 | 0.089 | 3 | 0.05269 | 0.9966 | 0.9543 |

| IL17A | 1 | 0.204 | 3 | 8.988 | 0.726 | 3 | −7.988 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| IL17F | 1 | 0.078 | 3 | 3.264 | 0.189 | 3 | −2.264 | 0.3038 | 0.0143 |

| IL18 | 1 | 0.144 | 3 | 1.358 | 0.225 | 3 | −0.3588 | 0.9966 | 0.6966 |

| IL18RA | 1 | 0.313 | 3 | 1.834 | 0.868 | 3 | −0.8341 | 0.9966 | 0.3649 |

| IL1A | 1 | 0.238 | 3 | 4.029 | 1.723 | 3 | −3.03 | 0.0308 | 0.0011 |

| IL1B | 1 | 0.117 | 3 | 3.101 | 0.222 | 3 | −2.102 | 0.3242 | 0.0229 |

| IL1RN | 1 | 0.051 | 3 | 1.825 | 0.402 | 3 | −0.8259 | 0.9966 | 0.3696 |

| IL21 | 1 | 0.434 | 3 | 1.299 | 0.533 | 3 | −0.3 | 0.9966 | 0.7444 |

| IL23A | 1 | 0.166 | 3 | 0.968 | 0.161 | 3 | 0.03178 | 0.9966 | 0.9724 |

| IL27 | 1 | 0.203 | 3 | 0.926 | 0.211 | 3 | 0.07378 | 0.9966 | 0.9361 |

| IL2RG | 1 | 0.099 | 3 | 1.412 | 0.322 | 3 | −0.4126 | 0.9966 | 0.6538 |

| IL4 | 1 | 0.090 | 3 | 0.881 | 0.091 | 3 | 0.1182 | 0.9966 | 0.8977 |

| IL4R | 1 | 0.053 | 3 | 1.034 | 0.078 | 3 | −0.03445 | 0.9966 | 0.9701 |

| IL5 | 1 | 0.098 | 3 | 1.025 | 0.067 | 3 | −0.02593 | 0.9966 | 0.9775 |

| IL5RA | 1 | 0.331 | 3 | 0.852 | 0.327 | 3 | 0.1474 | 0.9966 | 0.8727 |

| IL6 | 1 | 0.121 | 3 | 2.672 | 0.188 | 3 | −1.672 | 0.7294 | 0.0698 |

| IL6R | 1 | 0.147 | 3 | 1.218 | 0.120 | 3 | −0.2183 | 0.9966 | 0.8125 |

| IL6ST | 1 | 0.159 | 3 | 1.141 | 0.213 | 3 | −0.1418 | 0.9966 | 0.8775 |

| IL7 | 1 | 0.063 | 3 | 1.191 | 0.082 | 3 | −0.1912 | 0.9966 | 0.8354 |

| IL7R | 1 | 0.073 | 3 | 1.448 | 0.107 | 3 | −0.4489 | 0.9966 | 0.6256 |

| IL8 | 1 | 0.464 | 3 | 18.028 | 13.101 | 2 | −17.03 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| IL9 | 1 | 0.386 | 3 | 1.336 | 0.656 | 3 | −0.3367 | 0.9966 | 0.7144 |

| LIF | 1 | 0.054 | 3 | 1.115 | 0.126 | 3 | −0.1154 | 0.9966 | 0.9002 |

| OSM | 1 | 0.145 | 3 | 1.277 | 0.134 | 3 | −0.2772 | 0.9966 | 0.7632 |

| IL17B | 1 | 0.057 | 3 | 1.192 | 0.526 | 3 | −0.1923 | 0.9966 | 0.8345 |

| IL33 | 1 | 0.093 | 3 | 0.743 | 0.029 | 3 | 0.256 | 0.9966 | 0.7808 |

| LOC100519468 | 1 | 0.225 | 3 | 0.777 | 0.212 | 3 | 0.2225 | 0.9966 | 0.8089 |

| IL9R | 1 | 0.046 | 3 | 0.917 | 0.155 | 3 | 0.08256 | 0.9966 | 0.9285 |

| LOC100621682 | 1 | 0.121 | 3 | 0.687 | 0.086 | 3 | 0.3126 | 0.9966 | 0.734 |

| IL2RB | 1 | 0.673 | 3 | 2.514 | 0.931 | 3 | −1.515 | 0.7761 | 0.1004 |

| LTA | 1 | 0.178 | 3 | 0.981 | 0.234 | 3 | 0.01811 | 0.9966 | 0.9843 |

| LTB | 1 | 0.138 | 3 | 0.845 | 0.229 | 3 | 0.1544 | 0.9966 | 0.8667 |

| MIF | 1 | 0.165 | 3 | 1.126 | 0.122 | 3 | −0.1268 | 0.9966 | 0.8904 |

| NAMPT | 1 | 0.277 | 3 | 1.526 | 0.188 | 3 | −0.5269 | 0.9966 | 0.5669 |

| SPP1 | 1 | 0.112 | 3 | 1.597 | 0.240 | 3 | −0.5979 | 0.9966 | 0.5159 |

| TGFB2 | 1 | 0.164 | 3 | 1.371 | 0.044 | 3 | −0.3711 | 0.9966 | 0.6867 |

| TNF | 1 | 0.095 | 3 | 2.584 | 0.460 | 3 | −1.584 | 0.7294 | 0.0858 |

| TNFRSF11B | 1 | 0.251 | 3 | 1.257 | 0.271 | 3 | −0.2576 | 0.9966 | 0.7795 |

| TNFRSF13B | 1 | 0.241 | 3 | 1.192 | 0.327 | 3 | −0.1922 | 0.9966 | 0.8345 |

| TNFSF4 | 1 | 0.140 | 3 | 1.355 | 0.136 | 3 | −0.3557 | 0.9966 | 0.6991 |

| VEGFA | 1 | 0.082 | 3 | 1.076 | 0.083 | 3 | −0.07657 | 0.9966 | 0.9337 |

| TNFRSF10 | 1 | 0.107 | 3 | 1.094 | 0.022 | 3 | −0.09462 | 0.9966 | 0.9181 |

| IL17A | 1 | 0.155 | 5 | 41.91 | 19.85 | 5 | −40.91 | N/A | 0.0733 |

| IL1A | 1 | 0.158 | 5 | 2.094 | 0.401 | 5 | −1.094 | N/A | 0.0349 |

| IL8 | 1 | 0.152 | 5 | 2.701 | 0.529 | 5 | −1.701 | N/A | 0.0150 |

data in shaded rows were obtained using TaqMan primer and probes with β-actin as reference gene. In instances where the n is less than 3, the transcript was either not detected due to a technical error (i.e. the well was not loaded with cDNA), or because the transcript was not expressed at levels that were distinguishable from background.

Table 2.

List of transcripts queried through inflammatory-directed PCR arrays in piglet lung tissues

| saline | Bethanechol | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Name | Mean | SEM | n | Mean | SEM | n | Mean Diff. | q value | P Value |

| AIMP1 | 1 | 0.040 | 4 | 1.234 | 0.176 | 5 | −0.234 | 0.7991 | 0.5042 |

| BMP2 | 1 | 0.072 | 5 | 0.771 | 0.053 | 5 | 0.2288 | 0.7991 | 0.4885 |

| C5 | 1 | 0.170 | 5 | 1.115 | 0.075 | 5 | −0.1153 | 0.8612 | 0.7270 |

| CCL1 | 1 | 0.154 | 5 | 1.444 | 0.447 | 5 | −0.4441 | 0.7991 | 0.1789 |

| CCL17 | 1 | 0.213 | 5 | 0.618 | 0.074 | 5 | 0.382 | 0.7991 | 0.2476 |

| CCL2 | 1 | 0.191 | 5 | 0.690 | 0.086 | 5 | 0.3098 | 0.7991 | 0.3483 |

| CCL20 | 1 | 0.161 | 5 | 0.841 | 0.108 | 5 | 0.1588 | 0.7991 | 0.6306 |

| CCL21 | 1 | 0.208 | 5 | 0.652 | 0.089 | 5 | 0.3472 | 0.7991 | 0.2933 |

| CCL22 | 1 | 0.180 | 5 | 0.750 | 0.104 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.7991 | 0.4492 |

| CCL3L1 | 1 | 0.267 | 5 | 1.242 | 0.151 | 5 | −0.2423 | 0.7991 | 0.4632 |

| CCL4 | 1 | 0.137 | 5 | 1.670 | 0.110 | 5 | −0.67 | 0.6139 | 0.0428 |

| CCL5 | 1 | 0.088 | 5 | 1.003 | 0.125 | 5 | −0.003831 | >0.9999 | 0.9907 |

| CCL8 | 1 | 0.297 | 4 | 1.489 | 0.245 | 5 | −0.4897 | 0.7991 | 0.1624 |

| CCR1 | 1 | 0.194 | 5 | 1.032 | 0.040 | 5 | −0.03234 | 0.9923 | 0.9220 |

| CCR10 | 1 | 0.173 | 5 | 0.638 | 0.110 | 5 | 0.3612 | 0.7991 | 0.2743 |

| CCR2 | 1 | 0.258 | 5 | 0.717 | 0.085 | 5 | 0.2823 | 0.7991 | 0.3927 |

| CCR3 | 1 | 0.124 | 5 | 0.835 | 0.126 | 5 | 0.1648 | 0.7991 | 0.6178 |

| CCR4 | 1 | 0.207 | 5 | 0.676 | 0.111 | 5 | 0.3231 | 0.7991 | 0.3280 |

| CCR5 | 1 | 0.303 | 5 | 0.953 | 0.083 | 5 | 0.04667 | 0.9674 | 0.8876 |

| CCR7 | 1 | 0.164 | 5 | 0.692 | 0.107 | 5 | 0.3079 | 0.7991 | 0.3513 |

| CD40LG | 1 | 0.095 | 5 | 0.561 | 0.061 | 5 | 0.4384 | 0.7991 | 0.1846 |

| CD70 | 1 | 0.278 | 5 | 1.212 | 0.122 | 5 | −0.2121 | 0.7991 | 0.5207 |

| CSF1 | 1 | 0.099 | 5 | 0.793 | 0.058 | 5 | 0.2063 | 0.7991 | 0.5322 |

| CSF2 | 1 | 0.353 | 5 | 1.118 | 0.242 | 5 | −0.1184 | 0.8612 | 0.7200 |

| CSF3 | 1 | 0.169 | 5 | 0.597 | 0.075 | 5 | 0.403 | 0.7991 | 0.2226 |

| CXCL10 | 1 | 0.338 | 5 | 2.400 | 0.464 | 5 | −1.401 | 0.0011 | <0.0001 |

| CXCL11 | 1 | 0.290 | 5 | 1.415 | 0.216 | 5 | −0.4154 | 0.7991 | 0.2087 |

| CXCL12 | 1 | 0.120 | 5 | 0.942 | 0.109 | 5 | 0.05758 | 0.9511 | 0.8616 |

| CXCL2 | 1 | 0.181 | 5 | 0.903 | 0.071 | 5 | 0.09672 | 0.8645 | 0.7696 |

| CXCL9 | 1 | 0.398 | 5 | 1.851 | 0.452 | 5 | −0.8515 | 0.2902 | 0.0101 |

| CXCR2 | 1 | 0.087 | 5 | 1.191 | 0.212 | 5 | −0.192 | 0.7991 | 0.5611 |

| CXCR4 | 1 | 0.090 | 5 | 1.178 | 0.200 | 5 | −0.1787 | 0.7991 | 0.5884 |

| FASLG | 1 | 0.089 | 5 | 1.242 | 0.240 | 5 | −0.2425 | 0.7991 | 0.4628 |

| FLT3LG | 1 | 0.044 | 5 | 0.754 | 0.054 | 5 | 0.2458 | 0.7991 | 0.4568 |

| IFNG | 1 | 0.239 | 5 | 3.509 | 1.534 | 5 | −2.509 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| IL10 | 1 | 0.218 | 5 | 1.484 | 0.160 | 5 | −0.4848 | 0.7991 | 0.1424 |

| IL10RA | 1 | 0.144 | 5 | 0.895 | 0.072 | 5 | 0.1046 | 0.8645 | 0.7514 |

| IL10RB | 1 | 0.157 | 5 | 0.696 | 0.071 | 5 | 0.3039 | 0.7991 | 0.3575 |

| IL12B | 1 | 0.243 | 5 | 0.879 | 0.187 | 4 | 0.1208 | 0.8612 | 0.7301 |

| 1L13 | 1 | 0.122 | 5 | 0.698 | 0.195 | 4 | 0.3011 | 0.7991 | 0.3901 |

| IL15 | 1 | 0.292 | 5 | 0.439 | 0.131 | 5 | 0.5602 | 0.7991 | 0.0902 |

| IL16 | 1 | 0.128 | 5 | 0.807 | 0.105 | 5 | 0.1925 | 0.7991 | 0.5599 |

| IL17A | 1 | 0.342 | 5 | 0.558 | 0.201 | 5 | 0.4418 | 0.7991 | 0.1812 |

| IL17F | 1 | 0.184 | 5 | 0.899 | 0.240 | 5 | 0.1001 | 0.8645 | 0.7618 |

| IL18 | 1 | 0.203 | 5 | 1.199 | 0.348 | 5 | −0.1994 | 0.7991 | 0.5460 |

| IL18RA | 1 | 0.432 | 5 | 0.547 | 0.130 | 5 | 0.4526 | 0.7991 | 0.1708 |

| IL1A | 1 | 0.252 | 5 | 0.530 | 0.095 | 5 | 0.4697 | 0.7991 | 0.1553 |

| IL1B | 1 | 0.100 | 5 | 0.753 | 0.102 | 5 | 0.2468 | 0.7991 | 0.4549 |

| IL1RN | 1 | 0.054 | 5 | 0.829 | 0.072 | 5 | 0.1704 | 0.7991 | 0.6060 |

| IL21 | 1 | 0.353 | 5 | 0.774 | 0.110 | 5 | 0.2254 | 0.7991 | 0.4949 |

| IL23A | 1 | 0.261 | 5 | 0.810 | 0.197 | 5 | 0.19 | 0.7991 | 0.5652 |

| IL27 | 1 | 0.198 | 5 | 0.803 | 0.079 | 5 | 0.1967 | 0.7991 | 0.5514 |

| IL2RG | 1 | 0.190 | 5 | 0.904 | 0.140 | 5 | 0.09518 | 0.8645 | 0.7732 |

| IL4 | 1 | 0.220 | 5 | 0.579 | 0.096 | 5 | 0.4208 | 0.7991 | 0.2029 |

| IL4R | 1 | 0.123 | 5 | 0.814 | 0.090 | 5 | 0.1852 | 0.7991 | 0.5751 |

| IL5 | 1 | 0.238 | 5 | 0.714 | 0.130 | 5 | 0.2852 | 0.7991 | 0.3880 |

| IL5RA | 1 | 0.422 | 5 | 0.481 | 0.048 | 5 | 0.5188 | 0.7991 | 0.1165 |

| IL6 | 1 | 0.269 | 5 | 0.713 | 0.198 | 5 | 0.2869 | 0.7991 | 0.3851 |

| IL6R | 1 | 0.121 | 5 | 0.822 | 0.132 | 5 | 0.1779 | 0.7991 | 0.5900 |

| IL6ST | 1 | 0.311 | 5 | 0.720 | 0.052 | 5 | 0.2797 | 0.7991 | 0.3972 |

| IL7 | 1 | 0.226 | 5 | 0.977 | 0.153 | 5 | 0.02259 | 0.9977 | 0.9455 |

| IL7R | 1 | 0.222 | 5 | 0.716 | 0.145 | 5 | 0.283 | 0.7991 | 0.3915 |

| IL8 | 1 | 0.399 | 3 | 0.305 | 0.188 | 3 | 0.6947 | 0.7991 | 0.1035 |

| IL9 | 1 | 0.488 | 5 | 0.247 | 0.041 | 5 | 0.7522 | 0.4951 | 0.0230 |

| LIF | 1 | 0.218 | 5 | 0.656 | 0.058 | 5 | 0.3433 | 0.7991 | 0.2988 |

| OSM | 1 | 0.128 | 5 | 0.801 | 0.117 | 5 | 0.1985 | 0.7991 | 0.5478 |

| IL17B | 1 | 0.496 | 5 | 0.380 | 0.046 | 5 | 0.6193 | 0.7514 | 0.0611 |

| IL33 | 1 | 0.128 | 5 | 1.327 | 0.360 | 5 | −0.3271 | 0.7991 | 0.3221 |

| LOC100519468 | 1 | 0.187 | 5 | 0.626 | 0.072 | 5 | 0.3738 | 0.7991 | 0.2579 |

| IL9R | 1 | 0.117 | 5 | 0.773 | 0.131 | 5 | 0.2267 | 0.7991 | 0.4924 |

| LOC100621682 | 1 | 0.160 | 5 | 0.577 | 0.092 | 5 | 0.423 | 0.7991 | 0.2005 |

| IL2RB | 1 | 0.533 | 5 | 0.317 | 0.061 | 5 | 0.6826 | 0.6139 | 0.0390 |

| LTA | 1 | 0.139 | 5 | 0.654 | 0.064 | 5 | 0.346 | 0.7991 | 0.2950 |

| LTB | 1 | 0.238 | 5 | 0.841 | 0.115 | 5 | 0.1586 | 0.7991 | 0.6311 |

| MIF | 1 | 0.145 | 5 | 0.828 | 0.076 | 5 | 0.1719 | 0.7991 | 0.6028 |

| NAMPT | 1 | 0.284 | 5 | 0.630 | 0.086 | 5 | 0.3695 | 0.7991 | 0.2634 |

| SPP1 | 1 | 0.082 | 5 | 1.276 | 0.304 | 5 | −0.2763 | 0.7991 | 0.4028 |

| TGFB2 | 1 | 0.109 | 5 | 0.822 | 0.084 | 5 | 0.1775 | 0.7991 | 0.5910 |

| TNF | 1 | 0.223 | 5 | 1.116 | 0.142 | 5 | −0.1167 | 0.8612 | 0.7239 |

| TNFRSF11B | 1 | 0.116 | 5 | 0.882 | 0.129 | 5 | 0.1172 | 0.8612 | 0.7226 |

| TNFRSF13B | 1 | 0.427 | 5 | 0.827 | 0.149 | 5 | 0.173 | 0.7991 | 0.6005 |

| TNFSF4 | 1 | 0.078 | 5 | 0.984 | 0.105 | 5 | 0.01504 | 0.9997 | 0.9637 |

| VEGFA | 1 | 0.122 | 5 | 0.979 | 0.090 | 5 | 0.02062 | 0.9977 | 0.9502 |

| TNFRSF10 | 1 | 0.214 | 5 | 0.724 | 0.067 | 5 | 0.2758 | 0.7991 | 0.4037 |

In instances where the n is less than 5, the transcript was either not detected due to a technical error (i.e. the well was not loaded with cDNA), or because the transcript was not expressed at levels that were distinguishable from background.

We further examined inflammation by analyzing bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of bethanechol-treated piglets and saline-treated piglets. We found no differences in the total number of cells (Figure 1C). Granulocytes were similarly lacking in both groups (data not shown). We also examined protein concentrations of IL17A and IL8, the two cytokines that showed the greatest induction at the transcript level in the trachea (Table 1), and IFNγ and CXCL10. Concentrations of IL17A were below the limit of reliable detection (Figure 1D). IL8 levels were within the limit of sensitivity, but no differences were detected between treatment groups (Figure 1E). Concentrations of CXCL10 were below detection (data not shown); IFNγ was detected, but no differences were observed (Figure 1F). Histological examination also revealed no differences in inflammation (Figure 1G,H) or sloughed epithelium [14] (Figure 1I,J) between treatment groups in either the trachea or the lung. Edema and macrophages were also examined in the lung; however, no differences were detected between treatment groups (Figure 1K,L). Thus, bethanechol induced changes in inflammatory pathways that were only detectable at the transcriptional level.

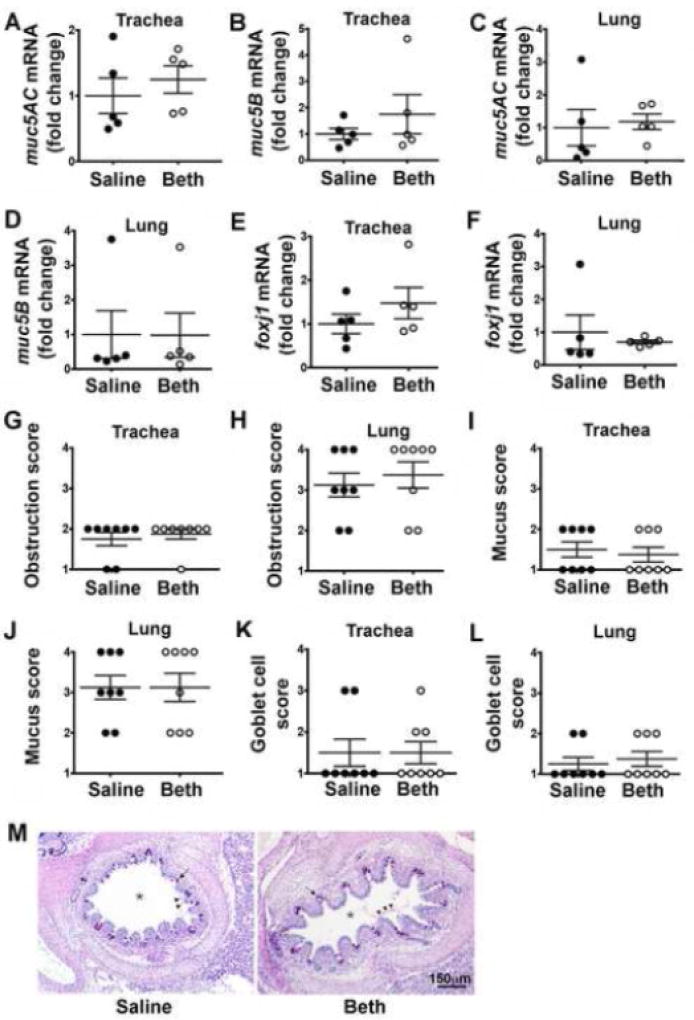

Because mucus obstruction and goblet cell hyperplasia are key features of asthma [15], we also quantified the transcript abundance of two major secreted mucin glycoproteins, muc5AC and muc5B [16]. Prior bethanechol treatment had no effect on muc5AC or muc5B mRNA expression in either the trachea (Figure 2A, B) or lung (Figure 2C,D). Transcript abundance of foxJ1, a marker of goblet cell progenitors [17], also revealed no differences in the trachea (Figure 2E) or lung (Figure 2F) of bethanechol-treated piglets compared to saline-treated piglets. Consistent with this, we observed no differences in histological indices of airway obstruction, mucus, or goblet cell number (Figure 2G–M).

Figure 2.

Mucin expression and mucus obstruction in neonatal piglet airways forty-eight hours post bethanechol challenge. Fold change mRNA expression of muc5AC (A, C), muc5B (B, D), and foxj1 (E, F). Histological scoring for airway obstruction (G, H), mucus (I, J), and goblet cells (K, L). Scoring parameters for goblet cells are as follows: 1= within normal limits; 2 = mild, uncommon, focal; 3 = moderate, multifocal; 4 = extensive, coalescing changes. Scoring parameters for obstruction and mucus are as follows: 1= within normal limits; 2 = accumulation within airway (<33%); 3 = accumulation within airway (34–66%); 4 = accumulation within airway (>67%). (M) Lung cross-section stained with dPAS; asterisk (*) indicates airway; arrow indicates goblet cells; arrowheads point to mucus. For panels A–F, n = 5 piglets per group; for panels G-L, n = 8 piglets per group. Data are mean ± SEM. For *, p < 0.05 for treatment effect using a two-way ANOVA. An unpaired Student’s t-test was used to assess mRNA fold changes. A non-parametric Mann Whitney test was performed to examine histological scoring. All tests were carried out using Prism 7.0a. Abbreviations: Beth, bethanechol; muc5AC, mucin5AC; muc5B, mucin5B; foxj1, forkhead box J1.

Previous data suggest a causal role for cholinergic signaling in the manifestation of insult-induced airway hyperreactivity [3,5]. In the current study, we have expanded upon those findings by demonstrating that cholinergic stimulation in the absence of an inciting insult is sufficient to evoke airway hyperreactivity. Moreover, while previous studies in mice suggest that repeated cholinergic stimulation exaggerates airway narrowing in lung slices ex vivo [18], our studies in the neonatal piglet suggest that repeated stimulation is not necessary to evoke airway pathophysiology.

We discovered that bethanechol-mediated airway hyperreactivity was associated with an increase in inflammatory transcripts (IL17A, IL1A, IL8, CXCL10, IFNγ) that are of known or proposed significance in asthma pathogenesis [19–22]. Although we did not anticipate this finding, previous studies have suggested a pro-inflammatory role for cholinergic signaling in the airway. Indeed, muscarinic receptor activation has been shown to increase the release of IL6 and IL8 from airway smooth muscle cells [23]. Activation of muscarinic receptors on CD4+ CD62L+ T cells has also been shown to facilitate differentiation into Th17 cells [24], which express IL17A [25]. Thus, while previous studies suggest that augmented cholinergic transmission secondary to inflammation underlies airway hyperreactivity [3–5], our data suggest that cholinergic transmission per se is capable of inducing transcription of asthma-associated pro-inflammatory mediators. Therefore, it is possible that cholinergic-mediated modulation of the inflammatory network is an underappreciated factor in insult-induced airway hyperreactivity.

We found elevations in transcripts for IFNγ in the lung following acute cholinergic potentiation. Of interest, Jacoby and colleagues demonstrated that IFNγ increases the release of acetylcholine in cultured parasympathetic neurons [26]. It was proposed that a mechanism by which viral infections precipitate airway hyperreactivity is through IFNγ–mediated augmentation of acetylcholine release. If true, then our data might suggest a possible feedforward circuit, in which cholinergic potentiation can increase IFNγ to further augment release of acetylcholine.

Although bethanechol treatment increased transcripts for pro-inflammatory mediators, overt inflammation in the form of infiltrating immune cells or increased concentrations of cytokines in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was not detected. Histological sections of both the trachea and the lung also revealed no evidence of inflammation. Perhaps repeated or prolonged cholinergic stimulation [23] might be required to elicit such changes. Alternatively, a single cholinergic stimulation in a primed or compromised airway might reveal detectable or enhanced inflammation.

It has been reported that repeated challenge with the cholinergic agonist methacholine is sufficient to induce airway remodeling in mild asthmatics [27]. For example, Grainge and colleagues found that epithelial TGF-β and Ki67, submucosal thickness, and goblet cell percentage were increased following a three-day challenge with methacholine. When methacholine was co-delivered with a bronchodilator, the airway remodeling was prevented, suggesting that bronchoconstriction, and not the methacholine itself, was responsible for the airway remodeling. In our studies, we delivered a single dose of bethanechol that elicited bronchoconstriction [9]. Although we did not observe airway remodeling in our piglets, our findings are consistent with previous work suggesting that bronchoconstriction contributes to asthma pathology [27].

In summary, our data suggest that a single cholinergic event is sufficient to evoke airway hyperreactivity. They also suggest that cholinergic signaling can induce transcription of several pro-inflammatory cytokines that are associated with asthma and airway hyperreactivity. Given these findings, it is possible that mitigating cholinergic transmission might be of even greater clinical significance than previously appreciated.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Giselle Edwards, Joshua Dadural, and Yan-Shin Liao for excellent technical assistance. The authors thank Dr. Jonathan Messer for helpful advice and suggestions in the preparation of this manuscript. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, 1K99HL119560-01A1, R00HL119560-03, 10T2TR001983-01, 1K08HL135433-01, and 1P01HL091842.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: None declared.

Author contributions statement

LRR, DKM, and MAA conceived the study. LRR, DKM, and MAA wrote the manuscript. LRR, SPK, KRA, MVG, DKM and MAA performed experiments. LRR, KRA and SPK performed data analysis.

References

- 1.Berend N, Salome CM, King GG. Mechanisms of airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma. Respirology. 2008;13:624–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell TD, Chai H, Berlow B, et al. Immunization with killed influenza virus in children with chronic asthma. Chest. 1978;73:140–145. doi: 10.1378/chest.73.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yost BL, Gleich GJ, Jacoby DB, et al. The changing role of eosinophils in long-term hyperreactivity following a single ozone exposure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L627–635. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00377.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elbon CL, Jacoby DB, Fryer AD. Pretreatment with an antibody to interleukin-5 prevents loss of pulmonary M2 muscarinic receptor function in antigen-challenged guinea pigs. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;12:320–328. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.12.3.7873198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorkness R, Clough JJ, Castleman WL, et al. Virus-induced airway obstruction and parasympathetic hyperresponsiveness in adult rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:28–34. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers CS, Abraham WM, Brogden KA, et al. The porcine lung as a potential model for cystic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L240–263. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90203.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyerholz DK, Reznikov LR. Simple and reproducible approaches for the collection of select porcine ganglia. J Neurosci Methods. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reznikov LR, Dong Q, Chen JH, et al. CFTR-deficient pigs display peripheral nervous system defects at birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3083–3088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222729110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez E, Bullard CM, Armani MH, et al. Comparison Study of Airway Reactivity Outcomes due to a Pharmacologic Challenge Test: Impulse Oscillometry versus Least Mean Squared Analysis Techniques. Pulm Med. 2013;2013:618576. doi: 10.1155/2013/618576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Awadalla M, Miyawaki S, Abou Alaiwa MH, et al. Early Airway Structural Changes in Cystic Fibrosis Pigs as a Determinant of Particle Distribution and Deposition. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2014;42:915–927. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0955-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang XX, Ostedgaard LS, Hoegger MJ, et al. Acidic pH increases airway surface liquid viscosity in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:879–891. doi: 10.1172/JCI83922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reznikov LR, Meyerholz DK, Adam RJ, et al. Acid-Sensing Ion Channel 1a Contributes to Airway Hyperreactivity in Mice. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Postma DS, Kerstjens HA. Characteristics of airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:S187–192. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.supplement_2.13tac170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fireman P. Understanding asthma pathophysiology. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2003;24:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ordonez CL, Khashayar R, Wong HH, et al. Mild and moderate asthma is associated with airway goblet cell hyperplasia and abnormalities in mucin gene expression. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:517–523. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2004039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, McGuckin MA. Structure and function of the polymeric mucins in airways mucus. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:459–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner J, Roger J, Fitau J, et al. Goblet cells are derived from a FOXJ1-expressing progenitor in a human airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:276–284. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0304OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel KR, Bai Y, Trieu KG, et al. Targeting acetylcholine receptor M3 prevents the progression of airway hyperreactivity in a mouse model of childhood asthma. FASEB J. 2017 doi: 10.1096/fj.201700186R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newcomb DC, Boswell MG, Sherrill TP, et al. IL-17A Induces Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription-6-Independent Airway Mucous Cell Metaplasia. Am J Resp Cell Mol. 2013;48:711–716. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0017OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson VJ, Yucesoy B, Luster MI. Prevention of IL-1 signaling attenuates airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in a murine model of toluene diisocyanate-induced asthma. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2005;116:851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charrad R, Kaabachi W, Rafrafi A, et al. IL-8 Gene Variants and Expression in Childhood Asthma. Lung. 2017;195:749–757. doi: 10.1007/s00408-017-0058-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gauthier M, Chakraborty K, Oriss TB, et al. Severe asthma in humans and mouse model suggests a CXCL10 signature underlies corticosteroid-resistant Th1 bias. JCI Insight. 2017;2 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.94580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oenema TA, Kolahian S, Nanninga JE, et al. Pro-inflammatory mechanisms of muscarinic receptor stimulation in airway smooth muscle. Resp Res. 2010;11 doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian J, Galitovskiy V, Chernyavsky AI, et al. Plasticity of the murine spleen T-cell cholinergic receptors and their role in in vitro differentiation of nave CD4 T cells toward the Th1, Th2 and Th17 lineages. Genes Immun. 2011;12:222–230. doi: 10.1038/gene.2010.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta PK, Wagner SR, Wu Q, et al. Th17 cells are not required for maintenance of IL-17A-producing gamma delta T cells in vivo. Immunology and Cell Biology. 2017;95:280–286. doi: 10.1038/icb.2016.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacoby DB, Xiao HQ, Lee NH, et al. Virus- and interferon-induced loss of inhibitory M-2 muscarinic receptor function and gene expression in cultured airway parasympathetic neurons. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;102:242–248. doi: 10.1172/JCI1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grainge CL, Lau LC, Ward JA, et al. Effect of bronchoconstriction on airway remodeling in asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2006–2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]