Abstract

Aims

Alcohol mixed with energy drink (AmED) use is associated with negative consequences including hazardous alcohol use and driving under the influence. While many studies have focused on correlates of AmED use among college samples, very few have examined patterns of AmED use during adolescence and young adulthood within the general population. Accordingly, the purpose of this study is to assess age differences in AmED use among a national sample of respondents aged 18 to 30.

Methods

The data for this study come from the Monitoring the Future panel study from 2012 to 2015. The sample consists of 2,222 respondents between the ages of 18 and 30. Multiple logistic regression using generalized estimating equations (GEE) was used to model past-year AmED prevalence across age and other covariates.

Results

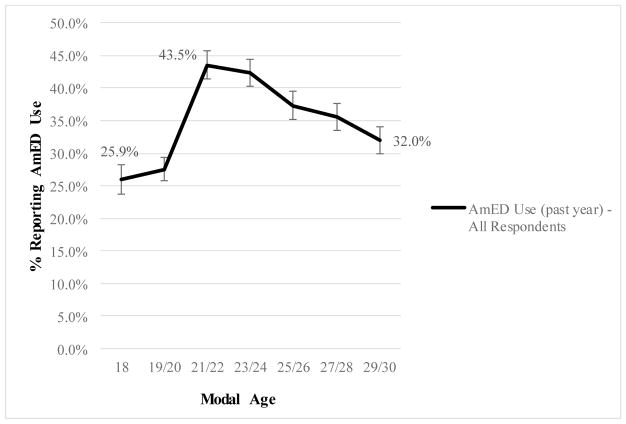

Nearly half (45.0%) of respondents indicated past-year AmED use at some point during the study period. The lowest prevalence rates were found at age 18 (25.9%) and the highest prevalence rates at age 21/22 (43.5%). GEE analyses indicated a statistically significant positive linear and negative quadratic trend with respect to the association between age of respondent and past-year AmED use. Namely, peak use occurred in early young adulthood (age 21/22 and 23/24) and then declined, reaching 32.0% by age 29/30. College attendance and several substance use behaviors at age 18 moderated these linear and quadratic age trends.

Conclusions

AmED use peaked rapidly in early young adulthood and declined into later young adulthood. Substance use during adolescence was associated with a higher incidence of AmED use across all young adult ages and a slower decline of AmED use after age 21/22. Several sociodemographic factors were associated with AmED use, particularly college attendance at the age of 21/22.

Keywords: alcohol mixed with energy drinks, alcohol, energy drinks, young adults, college

1. Introduction

Alcohol mixed with energy drink (AmED) use, such as Red Bull mixed with vodka, is linked to numerous health risks (for reviews and commentaries, see Arria & O’Brien, 2011; Linden & Lau-Barraco, 2014; Marczinski & Fillmore, 2014; McKetin, Coen, & Kaye, 2015; Peacock, Pennay, Droste, Bruno, & Lubman, 2014; Roemer & Stockwell, 2017). Research consistently finds that AmED users report heavier and riskier drinking than individuals who do not report AmED use (Linden & Lau-Barraco, 2014; McKetin et al., 2015; Patrick & Maggs, 2014; Peacock et al., 2014; VicHealth, 2016). There is also evidence that AmED users experience more alcohol-related negative consequences than non-AmED users (McKetin et al., 2015; Patrick & Maggs, 2014; Roemer & Stockwell, 2017). One reason for such increased harms may be greater risk-taking among AmED users. AmED use has been associated with increased risk of injury (see Roemer & Stockwell, 2017), driving after drinking (Bonar et al., 2015; Thombs et al., 2010; Tucker, Troxel, Ewing, & D’Amico, 2016), engagement in risky sexual behavior (e.g., unprotected sex; Snipes & Benotsch, 2013), aggression (Miller, Quigley, Eliseo-Arras, & Ball, 2016), and illicit substance use (Brache & Stockwell, 2011; Snipes & Benotsch, 2013). Within-person research has generally indicated that using alcohol and energy drinks on the same day (Patrick & Maggs, 2014) or at the same time (Linden-Carmichael & Lau-Barraco, 2017) is associated with greater alcohol-related consequences, although a review indicated some mixed findings (Peacock et al., 2014). There is some question as to whether greater risk among AmED users is attributable to these individuals having higher risk-taking propensities and engaging in higher-risk drinking events and/or whether AmED use increases the acute risk of alcohol-related harm. In any case, AmED use has emerged as an indicator of greater risk for alcohol-related problems (Linden & Lau-Barraco, 2014; McKetin et al., 2015; VicHealth, 2016).

There are physiological bases for the elevated alcohol consumption and risk-taking associated with AmED consumption (Marczinski, Stamates, & Maloney, 2018; Marczinski & Fillmore, 2014). Most evidence from experimental studies demonstrates that AmED use results in enhanced stimulation (or reduced sedation/fatigue) increased desire to drink and increased enjoyment of the effects of alcohol when compared with alcohol use alone (Marczinski, Fillmore, Stamates, & Maloney, 2016; Marczinski & Fillmore, 2014; McKetin et al., 2015), although some clinical studies find no effect of AmED on stimulation or sedation (e.g., Forward et al., 2017). Such feelings may mask important intoxication cues to stop drinking, thereby leading to higher alcohol consumption. Regardless of the stimulant nature of energy drinks, AmED consumption does not reverse the results of alcohol-related impairment on simple psychomotor tasks such as reaction time, and AmED consumption appears to attenuate only some of the complex task impairments resulting from alcohol consumption (McKetin et al., 2015). Relative to alcohol alone, AmED use has a differential effect on acute tolerance, which can influence one’s willingness to engage in risky behaviors such as driving after drinking (Marczinski et al., 2018).

AmED consumption is popular; among college students, prevalence of recent use ranges from about 20% to 25% (e.g., Brache & Stockwell, 2011; O’Brien, McCoy, Rhodes, Wagoner, & Wolfson, 2008). Few studies have examined AmED use in non-college student populations. Of the studies examining prevalence outside of college student populations, some evidence suggests that AmED use is more popular among younger individuals (i.e., ages 18–29; Berger, Fendrich, & Fuhrmann, 2013), particularly among underage alcohol consumers ages 19–20 (Kponee, Siegel, & Jernigan, 2014). In a nationally representative sample of 12th grade students, one quarter reported past-year AmED use (Martz, Patrick, & Schulenberg, 2015). In a community-based sample, AmED users were more likely to be White (Berger et al., 2013; Martz et al., 2015). Among 12th grade students, AmED users were more likely to be male and report other drug use (Martz et al., 2015). Limited research has examined other demographic differences, although one community-based study found no differences in educational attainment between AmED users and energy-drink-only users (Berger et al., 2013). The extent to which AmED use differs among same-aged young adults who are currently attending or not attending college has not yet been documented.

Research on AmED use has been largely based on cross-sectional studies, with little longitudinal data examining age-related changes in AmED consumption. Limited evidence suggests AmED use does sometimes change over time. In a study of first-year college student drinkers, the majority reported stability in AmED use from baseline to 6 months later (no AmED use at either time point [60%] or AmED use at both time points [12%]); however, some initiated (12%) or discontinued (16%) AmED use across the 6 months (Mallett, Scaglione, Reavy, & Turrisi, 2015). Longitudinal research across a longer time period has demonstrated that AmED use among college students was predictive of alcohol use severity and alcohol-related accidents two years later (Patrick, Evans-Polce, & Maggs, 2014). These findings suggest that AmED consumption patterns may change over time and have long-term effects on alcohol use and related harms.

Given the increased risks associated with being an AmED user, additional research is needed to examine patterns of AmED use across young adulthood. Compared to other age periods, during young adulthood individuals engage in drinking most heavily (Schulenberg et al., 2017) and are most likely to meet criteria for an alcohol use disorder (ages 18–25; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015). Men and White individuals generally maintain higher rates of heavy episodic drinking across adolescence and into adulthood (Evans-Polce, Vasilenko, & Lanza, 2015). Differences by college attendance are nuanced. Among young adults who attend college, alcohol use—including heavy episodic and high-intensity drinking—peaks during the early young adult years (Lanza & Collins, 2006; Patrick, Terry-McElrath, Kloska, & Schulenberg, 2016), while young adults who do not attend college show different patterns of drinking that may include continuing or increasing alcohol use during later young adulthood (e.g., Lanza & Collins, 2006). Identifying age-related changes in AmED use may highlight critical periods when prevention and intervention efforts are most needed, and understanding the ways in which various demographic differences are associated with AmED may help identify population subgroups at particular risk.

1.1 Current Study

Using longitudinal data from a large national sample, the current study examined the developmental course of AmED use from late adolescence through young adulthood. Three research questions were examined: (1) What is the overall age-related pattern of AmED use prevalence from age 18 to 30? (2) Controlling for the effect of age, to what extent are demographics (sex, race, college attendance) and other substance use during high school (binge drinking, cigarette use, marijuana use, nonmedical prescription drug use) significantly associated with overall AmED use during the transition to young adulthood? (3) To what extent do demographics and/or other substance use during high school moderate the overall age-related pattern of AmED use during the transition to young adulthood?

2. Methods

2.1 Study Design

This study used national panel data from the Monitoring the Future (MTF) study; detailed information on the project design and sampling methods is provided elsewhere (Bachman, Johnston, O’Malley, Schulenberg, & Miech, 2015; Miech et al., 2017; Schulenberg et al., 2017). Briefly, based on a multi-stage sampling procedure, MTF surveys nationally representative samples of approximately 17,000 U.S. high school seniors each year using questionnaires administered in classrooms during the regular school day. The response rates at baseline (12th grade, modal age 18) ranged from 79% to 85%; most all nonresponse was due to the given student being absent from school (less than 1.8% refused to participate) (Miech et al., 2017). Approximately 2,400 students from each yearly high school senior sample were randomly selected for biennial follow-up. A random half of the follow-up sample began biennial follow-up the following year (model age 19), while the other half began biennial follow-up two years after their senior year (modal age 20). Mailed questionnaires were used to collect data at six follow-up modal ages (hereafter referred to simply as age): 19/20, 21/22, 23/24, 25/26, 27/28, and 29/30.

Measures of AmED use were first included in the MTF study in 2012 on one of six randomly distributed questionnaire forms; data from 2012–2015 are included here (with individuals from 12th grade cohorts 2002–2014; see Supplement Table 1). Participants included in the current analytic sample (N=2,222, out of an eligible 6,378) responded to the AmED use measures at least once from ages 18 through 29/30. Of the eligible participants, 3,186 were lost at first follow-up and another 970 respondents who responded to at least one follow-up were excluded due to missing data. Due to the panel design and limited years of data collection on AmED questions (starting in 2012), 4.1% were eligible at one time point, 21.7% were eligible at two time points, and 74.2% were eligible at three time points; in the analytic sample, 27.9% of respondents completed one time point, 49% completed two time points, and 23.1% completed three time points. As noted above, attrition weights were used to account for potential bias of respondents who dropped out of the study. The weighted percentage of respondents based on age was as follows: age 18 = 14.1%, 19/20 = 21.7%, 21/22 = 14.6%, 23/24 = 13.2%, 25/26 = 12.2%, 27/28 = 12.4%, 29/30 = 11.8%. The sample was 54.1% female and 63.6% White. Roughly 46.7% of the sample attended a four-year college, full-time, between the ages of 19 and 20. Additional sample characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (modal ages combined)

| % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Alcohol mixed with energy drink (AmED) Use (time-varying) | |

| Did not engage in past 12-month AmED use | 54.9 (52.6, 57.2) |

| Engaged in past 12-month AmED use | 45.0 (42.7, 4.73) |

| Sociodemographics (time invariant) | |

| Sex (measured at age 18) | |

| Male | 45.9 (43.5, 48.2) |

| Female | 54.1 (51.7, 56.4) |

| Race/Ethnicity (measured at age 18) | |

| White | 63.6 (61.2, 66.0) |

| Non-White | 36.4 (33.9, 38.7) |

| Parental Education (measured at age 18) | |

| Neither parent has a college degree | 48.3 (45.9, 50.6) |

| At least one parent has a college degree or higher | 51.6 (49.3, 54.0) |

| College Attendance (measured at age 19/20) | |

| No, did not attend a four-year college | 53.2 (50.9, 55.6) |

| Yes, attended a four-year college | 46.7 (44.4, 49.0) |

| 12th Grade Cohort Year (measured at age 18) | |

| 2000–2003 | 18.7 (17.1, 20.4) |

| 2004–2007 | 22.6 (20.9, 24.5) |

| 2008–2011 | 28.8 (26.7, 30.9) |

| 2012–2015 | 29.7 (27.4, 32.1) |

| Substance Use (time invariant – measured at age 18) | |

| Past 30-day cigarette use | |

| Did not smoke in the past 30 days | 81.7 (79.8, 83.5) |

| Smoked in the past 30 days | 18.2 (16.4, 20.2) |

| Past two-week binge drinking (5 or more drinks in one sitting) | |

| Did not binge drink | 74.3 (72.1, 76.4) |

| Engaged in binge drinking | 25.6 (23.5, 27.8) |

| Past year marijuana use | |

| Did not smoke marijuana | 65.7 (63.4, 68.0) |

| Smoked marijuana | 34.2 (31.9, 36.5) |

| Past year nonmedical prescription drug use | |

| Did not engage in nonmedical prescription drug use | 84.7 (83.1, 86.1) |

| Engaged in nonmedical prescription drug use | 15.2 (13.8, 16.8) |

| Past year illicit substance use other than marijuana | |

| Did not engage in illicit substance use | 93.8 (92.8, 94.7) |

| Engaged in illicit substance use | 6.1 (5.2, 7.1) |

Note: N (unwtd.) = 2,222. Provided estimates are weighted.

The MTF panel oversamples drug users from the baseline sample; weights are used to adjust for this sampling. In addition, we incorporated nonresponse adjustments (i.e., attrition weights based on nonresponse at first follow-up) to the panel weights (i.e., unequal probabilities of selection into the panel sample) to account explicitly for MTF covariates that have been shown to be associated with nonresponse at future follow-ups (McCabe, Schulenberg, O’Malley, Patrick, & Kloska, 2014; Patrick, Terry-McElrath, Schulenberg, & Bray, 2017; Schulenberg et al., 2015; Terry-McElrath & O’Malley, 2015).

2.2 Measures

AmED use was measured at baseline and at each follow-up with the following question: “During the LAST 12 MONTHS, on how many occasions (if any) have you had an alcoholic beverage mixed with an energy drink (like Red Bull)?” Seven response options ranged from “0” to “40+”. AmED use was dichotomized to indicate whether respondents engaged in any AmED use (vs. none) during the past year.

Substance use at age 18 included dichotomous any/none measures for past 30-day cigarette smoking, past two-week binge drinking, past-year marijuana use, past-year nonmedical prescription drug use, and past-year illicit substance use other than marijuana. Cigarette smoking was measured using the following item: “How frequently have you smoked cigarettes during the past 30 days?” Binge drinkingwas measured using the following item: “Think back over the last two weeks. How many times have you had five or more drinks in a row?” Marijuana use was measured using the following item: “On how many occasions (if any) have you used marijuana during the last 12 months?” Nonmedical prescription drug use was a combined measure indicating any use (vs. none) of the following: narcotics/opioids, amphetamines/stimulants, sedatives, or tranquilizers. For each prescription drug class, use was measured as: “On how many occasions (if any) have you used [SPECIFIED PRESCRIPTION DRUG CLASS] during the last 12 months?” Respondents reporting any use of one or more of the four nonmedical prescription drug classes were coded as “any” nonmedical prescription drug use. Illicit substance use other than marijuana was a combined measure indicating any use (vs. none) of the following: LSD, psychedelics, cocaine, or heroin. For each substance, use was measured as: “On how many occasions (if any) have you used [SPECIFIED ILLICIT DRUG CLASS] during the last 12 months?” Respondents reporting any use of one or more of the four illicit drug classes were coded as “any” illicit drug use.

Age was coded as a continuous measure in order to create linear and quadratic terms. Accordingly, age 18 was coded as ‘0’, age 19/20 as ‘1’, age 21/22 as ‘2’, age 23/24 as ‘3’, age 25/26 as ‘4’, age 27/28 as ‘5’, and age 29/30 as ‘6’. Linear and quadratic terms were uncentered in the analyses.

College attendance was a yes/no dichotomy indicating if respondents attended a four-year college, full-time, at age 19/20 (during their first follow-up).

Additional covariates included sex (male versus female), race (White versus Non-White), parental level of education (neither parent has a college degree versus at least one parent has a college degree), and cohort year at age 18 (see Table 1 for more details).

2.3 Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using commercially available software (STATA/SE v.14.2; STATA Corp., College Station, TX) using attrition weights. To address research question 1 (RQ1; overall age-related patterns of AmED use prevalence from ages 18 to 30), the weighted percentages of respondents reporting past-year AmED use at ages 18, 19/20, 21/22, 23/24, 25/26, 27/28 and 29/30 were estimated and graphed. Then, to model the pattern of AmED use from ages 18 to 29/30, two logistic regression models using GEE with an independent correlation structure were fitted (Hanley, Negassa, Edwardes, & Forrester, 2003; Zeger, Liang, & Albert, 1988). Specifically, the first model included a linear age term, followed by a second model including both linear and quadratic age terms. To address RQ 2 (demographic and other age 18 substance use associations with AmED use), a GEE logistic regression model was fit simultaneously including all sociodemographic characteristics and age 18 substance use behaviors, controlling for linear and quadratic age terms. To address RQ 3 (extent to which demographics and/or other substance use during high school moderate the overall age-related pattern of AmED use), a series of 10 separate GEE models were run, each simultaneously including linear and quadratic age terms; all listed demographic and other substance use main effects, and interactions between linear and quadratic age terms and a single demographic/substance use term. For covariates with significant interactions, group-specific models were run to clarify differences in patterns of AmED from modal ages 18 to 29/30.

3. Results

3.1 Overall Age-related Pattern of AmED Use Prevalence from Modal Ages 18 to 29/30

Roughly 45% of respondents indicated past-year AmED use during the study period (see Table 1). Figure 1 shows the pattern of overall past-year AmED use by age. AmED use rapidly increased from 25.9% at age 18 into early young adulthood (peaking at 43.5% at age 21/22) and then declined through later young adulthood, reaching 32.0% at age 29/30. Table 2, Models 1 and 2, provide the results of GEE analyses confirming statistically significant positive linear (AOR = 1.59, 95% CI=1.36, 1.84) and negative quadratic (AOR = .934, 95% CI .913, .955) trends with respect to the correlation between age of respondent and past-year AmED use.

Figure 1. Overall prevalence of past 12-month alcohol mixed with energy drink (AmED) use from modal ages 18 to 29/30.

Note. N (unwtd.) = 2,222. Percentages were calculated using attrition weights. 95% confidence intervals are based on standard errors obtained using Taylor linearization

Table 2.

Examining age trends and correlates of past 12-month alcohol mixed with energy drink (AmED) use

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modal Age | OR 95% CI | AOR 95% CI | AOR 95% CI |

| Linear | 1.05** (1.01, 1.10) | 1.59*** (1.36, 1.84) | 1.69*** (1.42, 2.01) |

| Quadratic | 0.93*** (0.91, 0.96) | 0.91*** (0.89, 0.93) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | (ref) | ||

| Female | 0.65 *** (0.55, 0.78) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | (ref) | ||

| Non-White | 0.82 (0.67, 1.01) | ||

| Parental Education | |||

| Neither parent has a college degree | (ref) | ||

| At least one parent has a college degree | 1.22* (1.01, 1.47) | ||

| College Attendance at age 19/20 | |||

| No, did not attend a four-year college | (ref) | ||

| Yes, attended a four-year college | 1.38*** (1.14, 1.67) | ||

| 12th Grade Cohort | |||

| Continuous (0 = 1999 through 15 = 2014) | 0.94* (0.90, 0.99) | ||

| Past 30-day cigarette use at age 18 | |||

| No smoking in the past 30 days | (ref) | ||

| Smoked in the past 30 days | 1.04 (0.78, 1.40) | ||

| Past two-week binge drinking at age 18 | |||

| No binge drinking | (ref) | ||

| Engaged in binge drinking | 2.24*** (1.77, 2.83) | ||

| Past year marijuana use at age 18 | |||

| No marijuana use | (ref) | ||

| Smoked marijuana | 2.32*** (1.84, 2.93) | ||

| Past year nonmedical prescription drug use at age 18 | |||

| No nonmedical prescription drug use | (ref) | ||

| Engaged in nonmedical prescription drug use | 1.43* (1.07, 1.91) | ||

| Past year illicit substance use other than marijuana at age 18 | |||

| No illicit substance use | (ref) | ||

| Engaged in illicit substance use | 1.04 (0.72, 1.51) | ||

Note: N (unwtd.) = 2,222. OR = odds ratio. AOR = adjusted odds ratio. 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

3.2 Covariate Associations with Overall AmED Use Prevalence

Table 2, Model 3, shows that several sociodemographic and substance use behaviors at age 18 were significantly associated with AmED use across young adulthood, controlling for age. Significantly lower odds of AmED use were observed for females (vs. males). There also was a linear decrease in the odds of AmED use based on respondent cohort, whereby the likelihood of AmED use during any point in young adulthood (ages 18–30) was highest for individuals completing high school in 1999, and then decreased among individuals completing high school in succeeding years through 2014. Significantly higher odds of AmED use were observed for respondents who had at least one parent who graduated from college (vs. no parents with a college degree), were full-time students at a four-year college at age 19/20 (vs. not), and who—at age 18—reported binge drinking, marijuana use, or nonmedical prescription drug use. For instance, respondents who reported any past 12-month marijuana use at age 18 had higher odds of past-year AmED use across young adulthood (AOR = 2.32, 95% CI=1.84, 2.93) when compared to their peers who did not report similar marijuana use at age 18. AmED use across young adulthood was not significantly associated with race/ethnicity or age 18 cigarette use or illicit substance use.

3.3 Interactions Between Covariates and Age

Supplement Tables 2 and 3 report results of the 10 separate GEE models that simultaneously included linear and quadratic age terms, all sociodemographic/other substance use main effects, and interactions between linear and quadratic age terms and a single demographic/substance use term. Both linear and quadratic interactions were significant for college attendance, as well as age 18 cigarette use, binge drinking, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs. For age 18 marijuana use, a significant interaction was found only with the linear term. No significant interaction effects with either the linear or quadratic age terms were observed for sex, race, highest level of parental education, or cohort year.

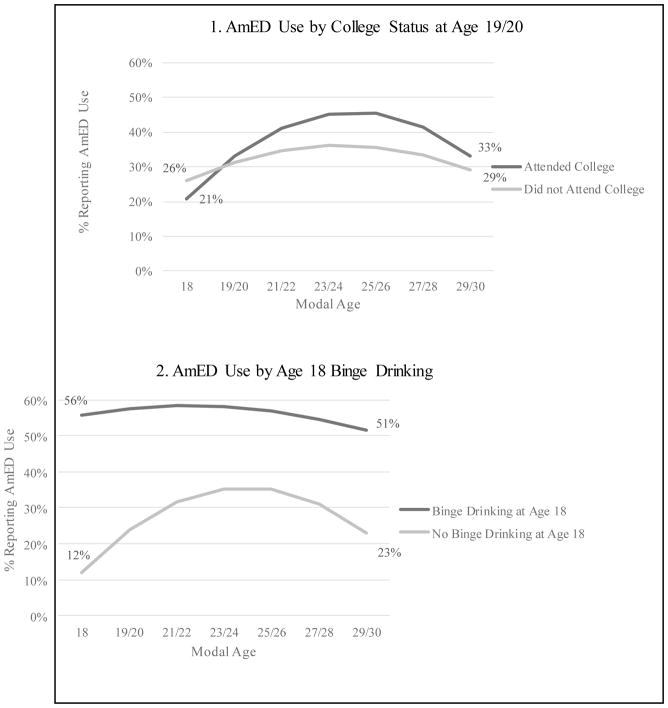

For the four covariates with significant interactions with both the linear and quadratic age terms, group-specific models were run to clarify differences in patterns of AmED use from modal ages 18 to 29/30; results are shown in Table 3. Respondents who attended college at age 19/20 had stronger positive linear and negative quadratic trends compared to respondents who did not attend college (see Figure 2, Panel 1 for a graphical representation). Specifically, AmED prevalence among college attenders rose from a modeled 21% at age 18 to 45% at ages 23/24 and 25/26, and then dropped to 33% by age 29/30. In contrast, modeled AmED prevalence for non-college attenders rose from 26% at age 18 to approximately 35% at age 23/24, and then decreased to 29% by age 29/30. Respondents who reported age 18 cigarette use, binge drinking, or nonmedical use of prescription drugs had weaker positive linear and negative quadratic trends when compared to their peers who did not use these substances at age 18, but higher AmED prevalence throughout young adulthood. Figure 2 Panel 2 provides a graphical representation of this pattern of association for binge drinking, revealing the weaker linear and quadratic trends in AmED use among respondents who indicated binge drinking at age 18 versus respondents who did not engage in this behavior. Essentially, AmED use at age 18 was markedly higher (and remained higher, with comparatively minor developmental change across young adulthood) for individuals reporting age 18 cigarette use, binge drinking, or nonmedical prescription drug use than for age 18 non-users of these other substances.

Table 3.

Examining subgroup differences in the association between age and alcohol mixed with energy drink (AmED) use.

| College attendance at age 19/20 | Cigarette use at age 18 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attended college (n=1093) | Did not attend (n=1129) | Any use (n=470) | No use (n=1752) | |

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Linear age term | 2.05*** (1.36, 2.25) | 1.44** (1.11, 1.87) | 1.08 (0.71, 1.66) | 1.91***(1.57, 2.32) |

| Quadratic age term | 0.89*** (0.88, 0.95) | 0.93*** (0.89, 0.96) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 0.89***(0.87, |

| Past 2-week binge drinking at age 18 | Past 12-month nonmedical prescription drug use at age 18 | |||

| Any use (n=613) | No use (n=1609) | Any use (n=519) | No use (n=1,703) | |

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Linear age term | 0.98 (0.71, 1.36) | 2.28*** (1.85, 2.82) | 1.11 (1.02, .790) | 1.90***(1.55, 2.32) |

| Quadratic age term | 0.96 (0.92, 1.01) | 0.88*** (0.85, 0.91) | 0.96 (0.91, 1.00) | 0.86***(0.87, 0.92) |

Note: AOR = adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval. All analyses controlled for sex, race/ethnicity, parental education, cohort year, non-medical prescription drug use, and illicit substance use other than marijuana. Each listed model also controlled for the three other covariates listed in the table.

Figure 2.

Past year alcohol mixed with energy drink (AmED) use between the ages of 18 and 30, modeled trends.

4. Discussion

This study documents, for the first time, developmental patterns in AmED use across young adulthood. Results among young adults overall demonstrate a dramatic increase in AmED consumption from ages 18 to 21, elevated peak levels of AmED consumption from ages 21 to 24, followed by decreases in AmED use from ages 24 to 30. This pattern is similar to overall trajectories observed for alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking (Maggs & Schulenberg, 2004; Patrick et al., 2016; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002; Schulenberg et al., 2017). Indeed, the similarities in overall trajectories for alcohol use and AmED use likely indicate that for alcohol users, at least some degree of combining alcohol with energy drinks is a normative behavior. Future research that examines factors associated with variation in the degree to which alcohol users combine alcohol with energy drinks is needed.

This study provided an opportunity to study AmED use across young adulthood in both college and non-college populations. A trajectory of significantly increasing AmED use during early young adulthood was observed for both individuals who attended traditional 4-year college at age 19/20 and those who did not, but the rate of increase and peak prevalence for AmED use was significantly more pronounced for those who attended college. Young adults who did not attend college had lower overall prevalence and a smaller increase. These patterns are similar to those previously documented for binge and high-intensity drinking among college attenders and non-attenders (Brown et al., 2008; Patrick et al., 2016; Schulenberg & Patrick, 2012). AmED use appears to be particularly common among college students during and immediately following years of college attendance. AmED users appear to be a particularly high-risk population, given the combination of both high-risk alcohol use and elevated risk for negative consequences (Brache & Stockwell, 2011; Linden-Carmichael & Lau-Barraco, 2017; Patrick & Maggs, 2014; Snipes & Benotsch, 2013; Thombs et al., 2010; Woolsey, Waigandt, & Beck, 2010). Efforts to provide prevention messaging regarding the dangers of AmED consumption may be particularly relevant among college students, but—as the results of the current study show—are also called for among non-college populations.

Substance use during high school (at age 18) was also associated with different age-related patterns of AmED use. Namely, young adults who engaged in cigarette use, binge drinking, or nonmedical use of prescription drugs at age 18 had consistently higher overall prevalence of AmED use across young adulthood, and a smaller degree of change in AmED use prevalence across age. In other words, young adults with a history of using a variety of substances were more likely to also use AmED and to have elevated AmED use throughout young adulthood. Young adults who did not report other substance use tended to increase their AmED use dramatically from ages 18 to 21 but still reported lower peak AmED use than individuals who used other substances at age 18. This suggests two things. First, adolescent intervention programs for other drug use should also consider indicating risks particular to AmED use. Second, prevention programs for AmED use may be needed for individuals who did not use other substances in high school in order to mitigate possible negative consequences associated with a marked increase in AmED use during the early years of young adulthood.

The likelihood of AmED use throughout young adulthood decreased significantly based on high school graduation cohort, with the highest odds associated with high school completion in 1999 and the lowest odds associated with high school completion in 2014. This apparent decline closely follows that of overall alcohol use and binge and high-intensity drinking among individuals in their early 20s (Patrick, Terry-McElrath, Miech, et al., 2017; Schulenberg et al., 2017). However, trends for binge and high-intensity drinking have been generally stable during the mid-20s and have been increasing during the late 20s (Patrick, Terry-McElrath, Miech, et al., 2017) Thus, the possibility that AmED use may be decreasing for all ages across cohorts is an observation that deserves additional future research.

Certain aspects of gender and race/ethnicity associations appear to be unique to AmED use and do not track similarly to associations with alcohol use alone. This is unlike the significant relationship between AmED use and college status, high school substance use, and cohort, which reflect (at least in part) previously recognized associations found for alcohol use without energy drinks. The current study found that higher past 12-month AmED use prevalence across young adulthood was reported by men (vs. women) and individuals who had at least one parent with a college degree (vs. those without a college-educated parent); however, these characteristics were not associated with significant differences in the rate of change in AmED use over developmental time. This is in contrast to prior research which has found that rates of developmental change in other high-risk drinking behaviors are faster for men than women (Chen & Jacobson, 2013; Nino, Cai, Mota-Back, & Comeau, 2017; Patrick et al., 2016), and possibly for individuals with higher parental education (Chen & Jacobson, 2013; note that no significant association was found by Patrick et al., 2016). Further, the current study found no indication that the overall prevalence or rate of developmental change in AmED use differed significantly between White versus non-White young adults. Again, past research has indicated that the rate of increase of some other alcohol use behaviors is higher for White than non-White individuals during early young adulthood (Chen & Jacobson, 2013; Patrick et al., 2016). These results indicate that the risk for a steep increase in the likelihood of AmED use in early young adulthood applies across sex, race/ethnicity, and parental education, which again calls for both broad-based prevention messaging relevant for a wide range of young adults on the risks associated with AmED use.

This study is strengthened by utilization of a broad national sample involving longitudinal data collection across ages 18 through 29/30, when the risks for negative consequences from alcohol use are the highest. However, the study’s findings are subject to limitations. These include use of a school-based 12th grade sample; high school dropouts are not included in this study, though dropout is associated with higher alcohol use risk (Tice, Lipari, & Van Horn, 2017). Further, data involve use of self-reported measures obtained over two-year intervals. The attrition rates for this study were non-trivial, although typical for recent studies using mail data collection (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2014). Attrition was addressed using previously described attrition weights, but some degree of bias in estimates may remain. Such limitations notwithstanding, this study was the first to provide data on developmental change in AmED use in a national sample of both college and non-college young adults. Future research should address AmED use at earlier ages (including age of initiation) and differences across subgroups to identify those most at risk. Intersections between AmED use and particularly high-risk drinking (e.g., high-intensity drinking; Patrick, 2016) should also be examined to clarify the acute consequences associated with combining energy drinks with alcohol during young adulthood.

Highlights.

Alcohol mixed with energy drink (AmED) use peaked at ages 21–24 in the U.S at 43.5%.

Full-time four-year college students reached higher levels of AmED use.

Binge drinking and use of marijuana and nonmedical prescription drugs predicted AmED use.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

Development of this manuscript was supported by research grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA037902 and P50DA039838) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA023504). Data collection and manuscript preparation were supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA001411 and R01DA016575). The study sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the study sponsors.

Development of this manuscript was supported by research grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA037902 and P50DA039838) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA023504). Data collection and manuscript preparation were supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA001411 and R01DA016575). The study sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the study sponsors.

Footnotes

Contributors

All authors contributed to the writing of the text and have approved the final manuscript. Dr. Veliz conducted statistical analysis and contributed to writing. Dr. Patrick conceptualized and led the manuscript preparation. Dr. Linden-Carmichael and Ms. Terry-McElrath contributed to writing and editing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arria AM, O’Brien MC. The “high” risk of energy drinks. JAMA. 2011;305(6):600–601. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. The Monitoring the Future project after four decades: Design and procedures (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No. 82) Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 2015. [Accessed October 15, 2017]. Available at http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/occpapers/mtf-occ82.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Berger L, Fendrich M, Fuhrmann D. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks: Are there associated negative consequences beyond hazardous drinking in college students? Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(9):2428–2432. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonar EE, Cunningham RM, Polshkova S, Chermack ST, Blow FC, Walton MA. Alcohol and energy drink use among adolescents seeking emergency department care. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;43:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brache K, Stockwell T. Drinking patterns and risk behaviors associated with combined alcohol and energy drink consumption in college drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(12):1133–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, McGue M, Maggs JL, Schulenberg JE, Hingson R, Swartzwelder S, Martin C, Chung T, Tapert SF, Sher K, Winters KC, Lowman C, Murphy S. A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 4):S290–310. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. [Accessed November 2, 2017];Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50) 2015 Available at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf.

- Chen P, Jacobson KC. Longitudinal relationships between college education and patterns of heavy drinking: A comparison between Caucasians and African-Americans. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53(3):356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Polce RJ, Vasilenko SA, Lanza ST. Changes in gender and racial/ethnic disparities in rates of cigarette use, regular heavy episodic drinking, and marijuana use: Ages 14 to 32. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;41:218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forward J, Akhurst J, Bruno R, Leong X, VanderNiet A, Bromfield H, Erny J, Bellamy T, Peacock A. Nature versus intensity of intoxication: Co-ingestion of alcohol and energy drinks and the effect on objective and subjective intoxication. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017;180:292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MD, Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: An orientation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157(4):364–375. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kponee KZ, Siegel M, Jernigan DH. The use of caffeinated alcoholic beverages among underage drinkers: Results of a national survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(1):253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Collins LM. A mixture model of discontinuous development in heavy drinking from ages 18 to 30: The role of college enrollment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(4):552–561. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden-Carmichael AN, Lau-Barraco C. A daily diary examination of caffeine mixed with alcohol among college students. Health Psychology. 2017;36(9):881–889. doi: 10.1037/hea0000506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden AN, Lau-Barraco C. A qualitative review of psychosocial risk factors associated with caffeinated alcohol use. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;22(2):144–153. doi: 10.1037/a0036334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Schulenberg JE. Trajectories of alcohol use during the transition to adulthood. Alcohol Research & Health. 2004;28(4):195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Scaglione N, Reavy R, Turrisi R. Longitudinal patterns of alcohol mixed with energy drink use among college students and their associations with risky drinking and problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76(3):389–396. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT, Stamates AL, Maloney SF. Desire to drink alcohol is enhanced with high caffeine energy drink mixers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40(9):1982–1990. doi: 10.1111/acer.13152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Stamates AL, Maloney SF. Differential development of acute tolerance may explain heightened rates of impaired driving after consumption of alcohol mixed with energy drinks versus alcohol alone. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2018 doi: 10.1037/pha0000173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Energy drinks mixed with alcohol: What are the risks? Nutrition Reviews. 2014;72(0 1):98–107. doi: 10.1111/nure.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martz ME, Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. Alcohol mixed with energy drink use among U.S. 12th-grade students: Prevalence, correlates, and associations with unsafe driving. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;56(5):557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Patrick ME, Kloska DD. Non-medical use of prescription opioids during the transition to adulthood: A multi-cohort national longitudinal study. Addiction. 2014;109(1):102–110. doi: 10.1111/add.12347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKetin R, Coen A, Kaye S. A comprehensive review of the effects of mixing caffeinated energy drinks with alcohol. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;151:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2016: Volume I, secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2017. [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available at http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol1_2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Quigley BM, Eliseo-Arras RK, Ball NJ. Alcohol mixed with energy drink use as an event-level predictor of physical and verbal aggression in bar conflicts. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40(1):161–169. doi: 10.1111/acer.12921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nino MD, Cai T, Mota-Back X, Comeau J. Gender differences in trajectories of alcohol use from ages 13 to 33 across Latina/o ethnic groups. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017;180:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MC, McCoy TP, Rhodes SD, Wagoner A, Wolfson M. Caffeinated cocktails: Energy drink consumption, high-risk drinking, and alcohol-related consequences among college students. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2008;15(5):453–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM, Miech RA, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Age-specific prevalence of binge and high-intensity drinking among U.S. young adults: Changes from 2005 to 2015. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017;41(7):1319–1328. doi: 10.1111/acer.13413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME. A call for research on high-intensity alcohol use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40(2):256–259. doi: 10.1111/acer.12945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Maggs JL. Energy drinks and alcohol: Links to alcohol behaviors and consequences across 56 days. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;54(4):454–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM, Kloska DD, Schulenberg JE. High-intensity drinking among young adults in the United States: Prevalence, frequency, and developmental change. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40(9):1905–1912. doi: 10.1111/acer.13164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM, Schulenberg JE, Bray BC. Patterns of high-intensity drinking among young adults in the United States: A repeated measures latent class analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;74:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Evans-Polce RJ, Maggs JL. Use of alcohol mixed with energy drinks as a predictor of alcohol-related consequences two years later. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(5):753–757. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock A, Pennay A, Droste N, Bruno R, Lubman DI. ‘High’ risk? A systematic review of the acute outcomes of mixing alcohol with energy drinks. Addiction. 2014;109(10):1612–1633. doi: 10.1111/add.12622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer A, Stockwell T. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks and risk of injury: A systematic review. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017;78(2):175–183. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2002;(14):54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2016: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19–55. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2017. [Accessed August 8, 2017]. Available at http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME, Kloska DD, Maslowsky J, Maggs JL, O’Malley PM. Substance use disorder in early midlife: A national prospective study on health and well-being correlates and long-term predictors. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment. 2015;9(Suppl 1):41–57. doi: 10.4137/SART.S31437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Historical and developmental patterns of alcohol and drug use among college students: Framing the problem. In: White HR, Rabiner D, editors. College Drinking and Drug Use. New York, NY: Guildford; 2012. pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Snipes DJ, Benotsch EG. High-risk cocktails and high-risk sex: Examining the relation between alcohol mixed with energy drink consumption, sexual behavior, and drug use in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(1):1418–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM. Trends and timing of cigarette smoking uptake among U.S. young adults: Survival analysis using annual national cohorts from 1976 to 2005. Addiction. 2015;110(7):1171–1181. doi: 10.1111/add.12926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, O’Mara RJ, Tsukamoto M, Rossheim ME, Weiler RM, Merves ML, Goldberger BA. Event-level analyses of energy drink consumption and alcohol intoxication in bar patrons. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(4):325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice P, Lipari RN, Van Horn SL. Substance use among 12th grade aged youths by dropout status. CBHSQ Report. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2017. [Accessed November 1, 2017]. Available at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_3196/ShortReport-3196.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Troxel WM, Ewing BA, D’Amico EJ. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks: Associations with risky drinking and functioning in high school. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;167:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VicHealth. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks: Exploring patterns of consumption and associated harms, Research summary. Melbourne: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation; 2016. [Accessed February 15, 2018]. Available at https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/-/media/ResourceCentre/PublicationsandResources/healthy-eating/Alcohol-mixed-Energy-Drinks.pdf?la=en&hash=CDB0A8B0E8ABFEAD5AB4894B5DE42796B24AAF33. [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey CL, Waigandt A, Beck NC. Athletes and energy drinks: Reported risk-taking and consequences from the combined use of alcohol and energy drinks. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 2010;22(1):65–71. doi: 10.1080/10413200903403224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: A generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(4):1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]