Abstract

Helicobacter pylori commonly infects the epithelial layer of the human stomach and in some individuals causes peptic ulcers, gastric adenocarcinoma or gastric lymphoma. Helicobacter pylori is a genetically diverse species, and the most important bacterial virulence factor that increases the risk of developing disease, versus asymptomatic colonization, is the cytotoxin associated gene pathogenicity island (cagPAI). Socially housed rhesus macaques are often naturally infected with H. pylori similar to that which colonizes humans, but little is known about the cagPAI. Here we show that H. pylori strains isolated from naturally infected rhesus macaques have a cagPAI very similar to that found in human clinical isolates, and like human isolates, it encodes a functional type IV secretion system. These results provide further support for the relevance of rhesus macaques as a valid experimental model for H. pylori infection in humans.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, rhesus macaques, CagA, type 4 secretion system, cag pathogenicity island, animal model

Naturally infected rhesus monkeys carry Helicobacter pylori with a functional T4SS that can translocate CagA and thus use the same virulence mechanisms that are associated with disease in humans.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori is a bacterium that frequently colonizes the gastric mucosa of the human stomach, infecting over 50% of the world's population. Although usually asymptomatic, ∼10% of those infected with H. pylori will develop peptic ulcer disease and 1%–3% will progress to gastric adenocarcinoma (Wroblewski, Peek and Wilson 2010), the third most common cause of cancer death worldwide (Ferlay et al.2015). The bacterial genetic locus most closely associated with clinical disease, rather than asymptomatic infection, is the H. pylori cag pathogenicity island (cagPAI). The cagPAI is a 40kb DNA segment that harbors 27 genes, many of which are required to produce a type IV secretion system (T4SS) that is essential for translocation of peptidoglycan and the CagA oncoprotein into host gastric epithelial cells (Odenbreit et al.2000; Viala et al.2004). The function of the other cagPAI genes is unknown.

Experimental animal models are essential to fully understand the pathogenesis of H. pylori infection. Most investigators use the mouse model, which is inexpensive, convenient and offers elegant host genetics, or the Mongolian gerbil, which is arguably the best disease model but has fewer reagents. The rhesus macaque is an alternative that has several advantages over conventional small animal models, including the anatomical and physiological similarities to humans. Moreover, unlike rodents, socially housed rhesus monkeys are naturally infected with H. pylori (Drazek, Dubois and Holmes 1994; Dubois et al.1994). Infection is common and occurs within the first year of life (Solnick et al.2003), which are features that mimic the epidemiology of H. pylori in humans in developing countries (Bardhan 1997) where infection is most common. All infected animals have chronic gastritis, and some develop atrophy (Dubois et al.1996), which is the histologic precursor to adenocarcinoma (Correa and Piazuelo 2012).

Although H. pylori from rhesus macaques is genetically very similar to that from humans (Joyce et al.2002), little is known about the prevalence or function of the cagPAI in rhesus-derived H. pylori. Here we demonstrate that naturally infected rhesus monkeys uniformly harbor H. pylori strains that have a cagPAI that is very similar genetically and functionally to that of human isolates. These results suggest that H. pylori utilizes similar virulence mechanisms to colonize rhesus and human hosts and further validate the rhesus macaque as an experimental model for H. pylori infection in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male and female rhesus macaques (N = 9) aged 3 to 5 years were located at the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC). Animals were housed in a 100 × 200 ft outdoor field cage that contained 80 to 120 male (∼30%) and female (∼70%) rhesus monkeys ranging in age from newborn to over 30 years. All experiments were performed in accordance with NIH guidelines, the Animal Welfare Act, and United States federal law, at the University of California, Davis, under animal use protocol #15751 approved by the UC Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Endoscopy with gastric biopsy

Endoscopy with gastric biopsy and subsequent H. pylori isolation were performed essentially as described previously (Solnick et al. 2003). Homogenized gastric biopsies were inoculated onto brucella agar containing 5% newborn calf serum (NCS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and TVPA antibiotics (trimethoprim, 5 mg/l; vancomycin, 10 mg/l; polymyxin B, 2.5 IU/l, amphotericin B, 2.5 mg/l; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and incubated for up to 8 days. A total of 10 single colonies confirmed as H. pylori were isolated from each monkey.

Bacterial culture

Helicobacter pylori was cultured on brucella agar (BBL, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated NCS and TVPA antibiotics. All H. pylori cultures were grown at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions generated by a fixed 5% O2 concentration (Anoxomat, Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA, USA).

Helicobacter pylori DNA fingerprinting

Genomic DNA from each single colony was prepared from plate-grown bacteria using a Qiagen DNA extraction kit (DNeasy® Blood & Tissue Kit, QIAGEN Sciences, MD, USA) or phenol-chloroform DNA extraction. Repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (REP-PCR) was performed as previously described (Solnick et al.2003) using the degenerate oligonucleotide primers REP1R-DT and REP2-DT (Table 1). DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel for 16 h at 18 V and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Table 1.

Primers used for PCR.

| Amplification | Name | Sequence (5΄ to 3΄)a | 26695 region |

|---|---|---|---|

| REP-PCR | Rep2-DT | NCG NCT TAT CNG GCC TAC | NA |

| Rep1R-DT | III NCG NCG NCA TCN GGC | ||

| cagA PCR detection | D008 | ATA ATG CTA AAT TAG ACA ACT TGA GCG A | 581152-581449 |

| R008 | TTA GAA TAA TCA ACA AAC ATC ACG CCA T | ||

| cag1-4 | HP0519:548L21 | CGC TCA AAC CTG AAA GAT CAA | 546585-550329 |

| cag5:2135U20 | TGG GGA AAG TGC CTA ATC AA | ||

| cag5-6 (including virB11) | cag4:381U28 | CAA CAA AAG CGT GTA TCA ATT AGT AGA A | 549969-554299 |

| cag7:5691U27 | CAA ATC TGT GGT AGA TGA AAT TAT CAA | ||

| cag7 | cag6:116L24 | CTT GCG GAT CGT TGC TAT CTT TTA | 553930-560178 |

| cag8:1395U28 | ATG GTA TAG AGT TAA TGA AAT TGC AGA A | ||

| cag8-10 | cag7:12L21 | TTC TTC ATT CAT GTC TTA ACG | 559978-563935 |

| cag10:61U25 | GCC CTT GAT AGA TTG GCT AAA CTC A | ||

| cag11-14 | cag10:627L24 | AAG CCA AAA GGA TTG ATG ATA AGA | 563346-567505 |

| cag14: 18U21 | ACG CAT TAG AGA TCC GAA CAA | ||

| cag15-18 | cag14:357L25 | CTA GAG TCT TAC TTG AGA GAC ACT C | 567142-571474 |

| cag18:110U22 | CCA ACC AAC AAG TGC TCA AAA A | ||

| cag19-22 | cag18:512L25 | GTC TGT GAA GCA GTG ATT AAG GAA G | 571048-575001 |

| cag22:153U27 | CCT TAC CGC TCT TTA TGA TTT TTC TAA | ||

| cag23-25 | cag22:681L23 | CGC TCA TAT CAA TCT GAA TCC AA | 574451-579074 |

| cag25:14U25 | CAA GAA TCA CTG ACA GCT ACA AGA A | ||

| Intergenic space between cag25 and cag26 (cagA) | cag25:271L20 | ATA CCG CCT GCC ACC GCT AA | 578798-580381 |

| cagA:437L25 | GGG GGT TGT ATG ATA TTT TCC ATA A | ||

| cag26 (cagA) | cagA:223U26 | AAT AAA GCG ATC AAA AAT TCT ACC AA | 580143-b |

| Rhesus pai reverse | GCT AAA TGC TTT CCA TCC ACA AAC | ||

| cagY PCR-RFLP | HP0527R | CCG TTC ATG TTC CAT ACA TCT TTG | 554810-560058 |

| HP0528F | CTA TGG TGA ATT GGA GCG TGT G |

For degenerate REP-PCR primers, I = inosine; N = any nucleotide

Rhesus pai reverse primer does not match 26695; NA = not applicable.

DNA sequence analysis

The entire cagPAI from one rhesus H. pylori isolate from monkey 1 was sequenced by PCR amplification of 10 overlapping DNA segments with flanking primers (Table 1) and the Expand Long Template PCR system (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Purified PCR products were sequenced directly by the Sanger method and assembled using Sequencher analysis software (GeneCodes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The resulting open reading frames were compared to sequenced human H. pylori isolates J99 (Alm et al.1999) and 26695 (Tomb et al.1997) using the Vector NTI software package (Life technologies, Foster City, CA, USA). To confirm correct assembly of the cagY 5΄ repeats, the cagY PCR products were electrophoresed on 0.4% agarose gels for 16 h at 18 V and the total cagY size was estimated. In addition, genes essential for IL-8 induction were amplified from two isolates from a second monkey (monkey 5) using flanking primers (Table 1). Sequencing and analysis were performed as above. All DNA sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KX683298 (for entire cagPAI) and KX807112-807127 (IL-8 essential cagPAI genes).

IL-8 ELISA

IL-8 was measured as described previously (Barrozo et al.2013). AGS gastric adenocarcinoma cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were co-cultured with H. pylori at an MOI of 1:100 for 18–24 h. Supernatants were harvested and diluted 1:8 prior to IL-8 assay by ELISA (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Helicobacter pylori J166 WT and its isogenic cagY deletion mutant (Barrozo et al.2013) were included as positive and negative controls, which typically induce around 3000 pg/ml and 200 pg/ml IL-8, respectively.

cagA PCR, CagA expression and translocation

cagA was amplified using primers D008 and R008 (Table 1) in PCR reactions as previously described (Figura et al.1998). Expression and phosphorylation of CagA were detected by immunoblot as previously described (Barrozo et al.2013). Briefly, lysates from H. pylori co-cultured with AGS gastric carcinoma cells were electrophoresed in a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel (BioRad, Hercules, CA), transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and incubated separately with IgG antibodies to CagA (Austral Biological, San Ramon, CA) and to phosphotyrosine (PY99, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Bound antibody was detected by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-IgG, visualized using ECL reagents (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) and exposure to X-ray film. Films were imaged with GelDoc XR+ imaging system (BioRad) using the white light conversion screen and the silver stain application. The Band Analysis tools of ImageLab software version 5.2.1 (BioRad) were used to select the bands in the blots and determine their relative density using results for J166 WT as reference.

cagY PCR-RFLP

cagY genotyping was performed by polymerase chain reaction restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) as described previously (Barrozo et al.2013), using primers HP0527R and HP0528F (Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 7.0 using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test and Pearson correlation as indicated. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Naturally infected rhesus macaques are colonized with clonally diverse strains of H. pylori

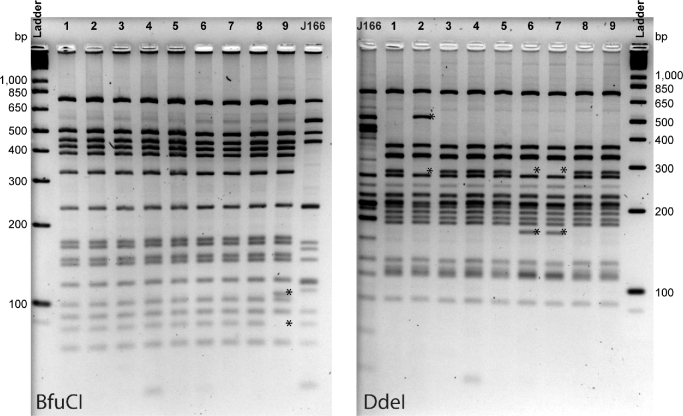

Rhesus monkeys at the CNPRC are housed in one-half acre outdoor field cages that contain a breeding colony of males and females. Animals are sometimes removed for experimentation, but new animals are typically not introduced other than by birth because this disrupts the social structure and sometimes leads to aggression. Since H. pylori strains within each field cage are more closely related than across different field cages (Solnick et al.2003), we obtained gastric biopsies from 9 monkeys housed in 9 different cages to better represent the diversity of H. pylori at the CNPRC. All monkeys were culture positive for H. pylori. To assess clonality of the 9 isolates, we performed REP-PCR on a single isolate from each monkey. As expected, the strains were more similar to one another than is typical among human isolates (Go et al.1995), but subtle differences were apparent by REP-PCR analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

REP-PCR DNA fingerprints of a single H. pylori isolate from each monkey (N = 9). Although related, each strain is unique, with one or more bands (*) that distinguish it from every other. Stars indicate bands that are either absent or present in each isolate compared to the isolate from monkey 1.

cagPAI DNA sequence of a rhesus Helicobacter pylori strain is highly related to that from strains found in human infection

All H. pylori strains isolated from rhesus monkeys were positive by PCR for the cagA gene (Fig. 2A), which was used as a marker for the presence of the cagPAI. We next sequenced the entire cagPAI of the isolate from monkey 1 and compared the results with the cagPAI from human isolates J99 and 26695, whose complete genomes are sequenced. The rhesus H. pylori strain carried the same cagPAI gene content as the human strains and had a high sequence similarity, typically >93% (Table 2). The most notable exceptions were cag7 (cagY) and cag26 (cagA), which are also highly variable among human isolates and known to be under strong diversifying selection (Olbermann et al.2010). cag2 from rhesus H. pylori was also very dissimilar from human isolates, which is not surprising since cag2 is sometimes absent among human strains and may be a pseudogene (Azuma et al.2004). These results indicate that the cagPAI gene sequences of H. pylori derived from rhesus monkeys are closely related to those of human isolates, with the exception of genes that are already known to be variable among human isolates.

Figure 2.

Functional characterization of the cagPAI in H. pylori isolates from naturally infected rhesus macaques. All strains contained cagA (A) and expressed CagA in bacterial culture (B) and during co-culture with gastric epithelial cells (C). Each cagPAI encoded a functional T4SS as indicated by CagA phosphorylation (D) and IL-8 induction (E). Values of IL-8 induction are mean ± SEM from three biological replicates normalized to the results for H. pylori strain J166. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to H. pylori J166 cagY deletion mutant (ANOVA with Dunnett's test).

Table 2.

Percent identity of rhesus cagPAI genes compared to human strains 26695 and J99.

| Gene | Start | Stop | Length | Direction | 26695 Designation | % Identity | J99 Designation | % Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cag1 | 1 | 348 | 348 | + | HP0520 | 96.0 | JHP0469 | 96.3 |

| cag2 | 379 | 1122 | 744 | + | HP0521 | 17.1 | JHP0470 | 48.7 |

| cag3 | 1115 | 2560 | 1446 | + | HP0522 | 97.2 | JHP0471 | 94.4 |

| cag4 | 2570 | 3079 | 510 | + | HP0523 | 95.7 | JHP0472 | 94.4 |

| cag5 | 3554 | 5800 | 2247 | − | HP0523 | 96.8 | JHP0472 | 95.8 |

| virB11 | 5809 | 6801 | 993 | − | HP0525 | 97.7 | JHP0474 | 96.8 |

| cag6 | 6816 | 7405 | 590 | − | HP0526 | 97.3 | JHP0475 | 97.8 |

| cag7 | 7543 | 12235 | 4693 | − | HP0527 | 78.5 | JHP0476 | 80.5 |

| cag8 | 12274 | 13842 | 1569 | − | HP0528 | 97.9 | JHP0477 | 96.4 |

| cag9 | 13895 | 15502 | 1608 | − | HP0529 | 97.6 | JHP0478 | 97.7 |

| cag10 | 15507 | 16265 | 759 | − | HP0530 | 97.2 | JHP0479 | 96.8 |

| cag11 | 16645 | 17295 | 651 | + | HP0531 | 94.8 | JHP0480 | 94.7 |

| cag12 | 17308 | 18150 | 843 | + | HP0532 | 98.1 | JHP0481 | 97.2 |

| cag13 | 18350 | 18919 | 570 | − | HP0534 | 96.3 | JHP0482 | 97.3 |

| cag14 | 19390 | 19770 | 381 | − | HP0535 | 96.9 | JHP0483 | 97.9 |

| cag15 | 20514 | 20858 | 345 | − | HP0536 | 93.9 | JHP0484 | 94.2 |

| cag16 | 21258 | 22388 | 1131 | + | HP0537 | 98.9 | JHP0485 | 96.6 |

| cag17 | 22403 | 23323 | 921 | + | HP0538 | 97.6 | JHP0486 | 97.4 |

| cag18 | 23405 | 24118 | 714 | − | HP0539 | 97.2 | JHP0487 | 97.5 |

| cag19 | 24115 | 25260 | 1146 | − | HP0540 | 96.2 | JHP0488 | 96.9 |

| cag20 | 25271 | 26383 | 1113 | − | HP0541 | 97.6 | JHP0489 | 97.4 |

| cag21 | 26400 | 26828 | 429 | − | HP0542 | 97.9 | JHP0490 | 97.4 |

| cag22 | 26883 | 27689 | 807 | − | HP0543 | 96.4 | JHP0491 | 96.4 |

| cag23 | 27691 | 30642 | 2952 | − | HP0544 | 97.6 | JHP0492 | 96.7 |

| cag24 | 30651 | 31274 | 624 | − | HP0545 | 96.0 | JHP0493 | 95.4 |

| cag25 | 31276 | 31623 | 348 | − | HP0546 | 95.7 | JHP0494 | 96.6 |

| cagA | 34355 | 37996 | 3642 | + | HP0547 | 90.0 | JHP0495 | 87.7 |

Helicobacter pylori isolated from natural infected rhesus macaques has a functional T4SS

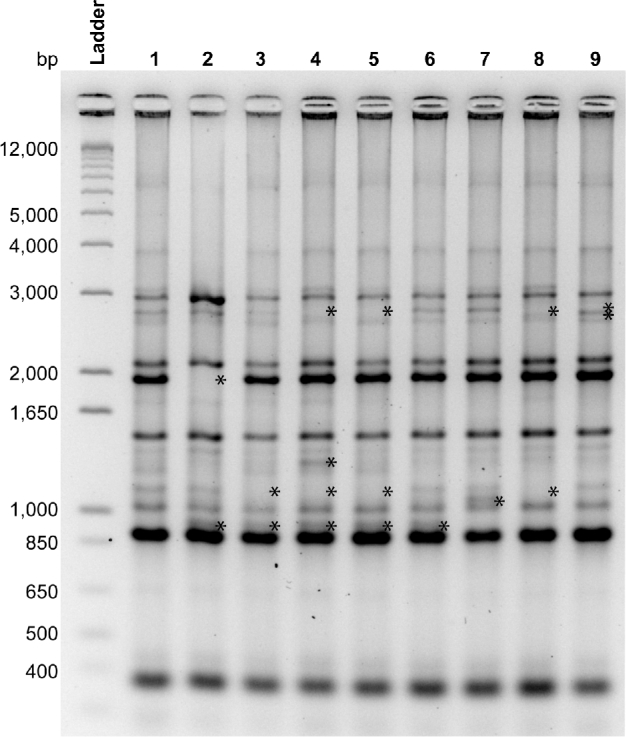

After confirming that the monkey isolates were uniformly positive for the cagPAI, with sequence similarity to human isolates, we assessed if the cagPAI expressed CagA and encoded a functional T4SS. Immunoblot of agar plate-cultured bacteria, as well as of H. pylori co-cultured with human AGS cells, demonstrated that all rhesus isolates expressed CagA (Fig. 2B and C). To determine if rhesus-derived H. pylori cagPAI encodes a functional T4SS, we performed co-culture experiments with isolates from each monkey, and compared the results to WT J166 and its isogenic cagY deletion mutant as positive and negative controls, respectively (Barrozo et al.2013). In co-culture with AGS cells, H. pylori induced IL-8 and CagA was tyrosine phosphorylated, suggesting that the rhesus-derived H. pylori contains a cagPAI that encodes a functional T4SS (Fig. 2D, E). Similar to what is found in cagPAI positive clinical isolates from humans (Olbermann et al.2010), H. pylori strains from individual animals showed marked variability in IL-8 induction, which was strongly correlated with total CagA (r = 0.685, P = 0.042) and phosphorylated CagA (r = 0.85, P = 0.004, Pearson correlation) detected in co-culture with AGS cells. Since T4SS function is modulated by recombination in cagY (Barrozo et al.2013), we next performed cagY PCR-RFLP on the isolates to determine if T4SS function was associated with differences in cagY. Digestion of amplified cagY with DdeI and BfuCI showed four distinct RFLP fingerprints among the nine isolates (Fig. 3), suggesting that cagY can undergo recombination during transmission and natural colonization of monkeys similar to what is seen in human infection. However, no consistent pattern was found between T4SS function and cagY RFLP. Together, these results demonstrate that all rhesus H. pylori isolates expressed a cagPAI that encoded a functional T4SS.

Figure 3.

cagY PCR-RFLP of a single H. pylori isolate from each monkey. cagY was PCR amplified, digested with BfuCI or DdeI and separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Four unique patterns were identified, with variant bands present and absent (*) compared to the most common pattern found in isolates from monkeys 1,3,4,5 and 8.

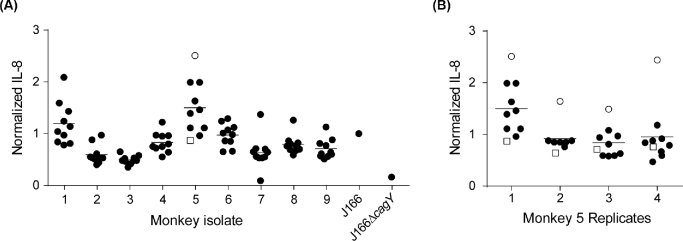

Heterogeneity of T4SS function among Helicobacter pylori colonies from within individual rhesus macaques

We previously showed that individual Helicobacter pylori isolates from experimentally infected rhesus monkeys sometimes displayed marked variability in T4SS function, which in some cases was related to recombination in cagY (Barrozo et al.2013). To better understand T4SS function within a population of H. pylori in naturally infected monkeys, we isolated 10 colonies from each monkey and examined their capacity to induce IL-8. Most isolates from within an individual animal showed similar IL-8 induction (Fig. 4A). Similar to what we have observed before in experimentally infected monkeys (Barrozo et al.2013), strains with relatively high levels of IL-8 induction (e.g. monkeys 1 and 5) showed greater variability. This might be measurement error, resulting from variability in host or bacterial cell density, or pipetting error, but could also reflect differences in T4SS function among isolates within an individual animal. To address this, we performed biological replicate assays on the colonies from monkey 5, which demonstrated that one colony (open circle) consistently showed greater induction of IL-8 (Fig. 4B). However, cagY PCR-RFLP and DNA sequence analysis of 16 cagPAI genes implicated in T4SS function (cag3-4, virB11, cag7-12, cag16, cag18-20, cag23, cag25-26) showed no differences between the isolate inducing high IL-8 (open circle) and one of the others (open square) (data not shown). These results suggest that there are sometimes reproducible differences in T4SS function among strains within an animal, but that they are not necessarily attributable to sequence differences in cagPAI genes.

Figure 4.

Heterogeneity of IL-8 induction among multiple individual H. pylori colonies isolated from each monkey. (A) Multiple isolates from within most individual monkeys showed similar induction of IL-8, though in some cases (e.g. monkeys 1 and 5) there was considerable variability. (B) Biological replicates of strains recovered from monkey 5 showed that the isolate with the highest IL-8 (open circle) was consistently higher than all others. The cagPAI sequence of this isolate was later compared to one of the isolates that induced low IL-8 (open square). IL-8 values are normalized to the results for H. pylori strain J166.

DISCUSSION

Socially housed rhesus monkeys are naturally infected with Helicobacter pylori (Drazek, Dubois and Holmes 1994; Dubois et al.1994, 1996; Solnick et al.2003), and some develop the associated diseases that affect humans, including peptic ulcer, gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma (Kimbrough 1966; Parker, Gilmore and Dubois 1981; Solnick, Eaton and Peek 2016). Therefore, rhesus monkeys have been used as a model host to study H. pylori pathogenesis, treatment and vaccine development (Solnick, Eaton and Peek 2016). In humans, expression of CagA is the major determinant for the outcome of infection, but it is unknown if the same is true for macaques. In fact, all Helicobacter species that infect animals other than humans lack the cagPAI (Vermoote et al.2011; Smet et al.2013), and it might thus be possible that cagPAI-negative H. pylori are favored in naturally infected monkeys. Here we studied the prevalence and function of the cagPAI in naturally infected monkeys and showed that rhesus-derived H. pylori uniformly expresses CagA and a functional T4SS with high gene sequence similarity to human strains. The similarity between rhesus- and human-derived H. pylori in cagPAI, and in whole genome DNA microarrays (Joyce et al.2002), suggests that rhesus monkeys in captivity may have acquired the infection from humans. Transmission of helicobacters has indeed been shown to occur between humans and other species (Haesebrouck et al.2009; Sabry, Abdel-Moein and Seleem 2016).

Helicobacter pylori infection in developing countries is common, is acquired very early in life and is almost uniformly positive for the cagPAI—all features that are similar to H. pylori infection in rhesus monkeys. As the H. pylori prevalence declines in developed countries, so too does the prevalence of the cagPAI (Perez-Perez et al.2002). The reasons for this are unknown, but it might indicate a role for the cagPAI in transmission of H. pylori between hosts. This is supported by the observation that transmission in mice has been found only with defective acid secretion (Bjorkholm et al.2004), which is promoted by cagPAI gene products that downregulate parietal cell H,K-ATPase expression (Saha et al.2010). Alternatively, features of the H. pylori microbial ecology in developing countries—and among socially housed macaques—might favor the cagPAI. Since the cagPAI appears to be important for acquisition of iron from the gastric epithelium (Tan et al.2011; Noto et al.2013, 2014), one possibility is that relative iron deficiency selects for cagPAI-positive strains. Another possibility is that the inflammatory response induced by the cagPAI, including expression of defensins and other antimicrobial peptides (Hornsby et al.2008; Bauer et al.2012, 2013), protects the host against other enteric infections, which are common in both developing countries and among socially housed rhesus monkeys. These similarities between H. pylori in macaques and in humans where infection is most common suggest that the rhesus model can be used to better understand the role of the cagPAI in the ecology of H. pylori.

Another similarity between H. pylori infection in humans and in naturally infected rhesus monkeys is that the cagPAI in rhesus H. pylori encodes a functional T4SS that translocates CagA and induces IL-8. Yet in experimental infection of rhesus monkeys, T4SS function is frequently lost by recombination in cagY, much like what happens uniformly during infection of mice (Barrozo et al.2013). The different outcome of experimental challenge versus natural infection in monkeys may result from the larger inoculum or perhaps from introduction of H. pylori directly into the stomach. Moreover, since natural H. pylori infection typically occurs in young macaques (and children), T4SS function may be preserved because they are relatively immunotolerant. This is consistent with results in infant mice, where cagPAI function is relatively preserved (Arnold et al.2010), and it may also explain the observation that the prevalence of the cagPAI is lower in countries where infection is acquired at an older age (Perez-Perez et al.2002).

Although T4SS function among isolates from a single individual is little studied, we found that some monkeys were colonized with strains that appeared clonal by REP-PCR, but that differed reproducibly in T4SS function (Fig. 4). Since we previously demonstrated cagY-dependent modulation of T4SS function, we used PCR-RFLP to determine if cagY genotype was related to T4SS function. Although cagY was variable among strains from different monkeys (Fig. 3), it did not correlate with T4SS function, and no differences were found among isolates from monkey 5 that differed in their induction of IL-8 (Fig. 4). Moreover, the high and low IL-8 inducing strains from monkey 5 did not differ at other cagPAI genes that are associated with T4SS function, suggesting that cagPAI genes whose function is unknown, or genes outside the cagPAI, can regulate T4SS function. Several examples of non-cagPAI gene regulation of T4SS function have been described, including the babA adhesin (Ishijima et al.2011), the ferric uptake regulator (Pich et al.2012) and a predicted glycosyltransferase that is induced by epithelial cell contact and upregulates expression of cagA (Bhattacharya et al.2016).

In summary, we have shown that H. pylori strains isolated from naturally infected, socially housed monkeys have a functional T4SS that translocates CagA, induces IL-8 and is highly related to human cagPAI. These results suggest that H. pylori can use the same virulence mechanisms in monkeys as in humans, and support the relevance of the rhesus monkey as a model for H. pylori infection in humans.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ECS, SLD, HDE, LMH and JVS: conceived and designed the experiment. ECS, SLD, HDE and LMH: performed experiments. ECS, SLD, HDE, LMH and JVS: analyzed data. ECS, SLD and JVS: wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lucy Cai for technical assistance and Don Canfield for endoscopy of rhesus monkeys.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI108713 to JVS) and the California National Primate Research Center Base Grant (P51OD011107) from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest.None declared.

REFERENCES

- Alm RA, Ling LL, Moir DT et al. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 1999;397:176–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold IC, Lee JY, Amieva MR et al. Tolerance rather than immunity protects from Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric preneoplasia. Gastroenterology 2010;140:199–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma T, Yamakawa A, Yamazaki S et al. Distinct diversity of the cag pathogenicity island among Helicobacter pylori strains in Japan. J Clin Microbiol 2004;42:2508–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardhan PK. Epidemiological features of Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. Clin Infect Dis 1997;25:973–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrozo RM, Cooke CL, Hansen LM et al. Functional plasticity in the type IV secretion system of Helicobacter pylori. PLoS Pathog 2013;9:e1003189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B, Pang E, Holland C et al. The Helicobacter pylori virulence effector CagA abrogates human beta–defensin 3 expression via inactivation of EGFR signaling. Cell Host Microbe 2012;11:576–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B, Wex T, Kuester D et al. Differential expression of human beta defensin 2 and 3 in gastric mucosa of Helicobacter pylori-infected individuals. Helicobacter 2013;18:6–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S, Mukherjee O, Mukhopadhyay AK et al. A conserved Helicobacter pylori gene, HP0102, is induced upon contact with gastric cells and has multiple roles in pathogenicity. J Infect Dis 2016;214:196–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkholm B, Guruge J, Karlsson M et al. Gnotobiotic transgenic mice reveal that transmission of Helicobacter pylori is facilitated by loss of acid–producing parietal cells in donors and recipients. Microbes Infect 2004;6:213–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa P, Piazuelo MB. The gastric precancerous cascade. J Digest Dis 2012;13:2–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drazek ES, Dubois A, Holmes RK. Characterization and presumptive identification of Helicobacter pylori isolates from rhesus monkeys. J Clin Microbiol 1994;32:1799–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois A, Berg DE, Incecik ET et al. Transient and persistent experimental infection of nonhuman primates with Helicobacter pylori: implications for human disease. Infect Immun 1996;64:2885–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois A, Fiala N, Hemanâ-Ackah LM et al. Natural gastric infection with Helicobacter pylori in monkeys: a model for spiral bacteria infection in humans. Gastroenterology 1994;106:1405–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figura N, Vindigni C, Covacci A et al. cagA positive and negative Helicobacter pylori strains are simultaneously present in the stomach of most patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia: relevance to histological damage. Gut 1998;42:772–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go MF, Chan KY, Versalovic J et al. Cluster analysis of Helicobacter pylori genomic DNA fingerprints suggests gastroduodenal disease-specific associations. Scand J Gastroenterology 1995;30:640–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haesebrouck F, Pasmans F, Flahou B et al. Gastric helicobacters in domestic animals and nonhuman primates and their significance for human health. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009;22:202–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby M, Huff JL, Kays R et al. Helicobacter pylori induces an antimicrobial response in rhesus macaques in a Cag Pathogenicity island-dependent manner. Gastroenterology 2008;134:1049–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishijima N, Suzuki M, Ashida H et al. BabA-mediated adherence is a potentiator of the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system activity. J Biol Chem 2011;286:25256–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce EA, Chan K, Salama NR et al. Redefining bacterial populations: a post-genomic reformation. Nat Rev Genet 2002;3:462–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrough R. Spontaneous malignant gastric tumor in a Rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Arch Pathol 1966;81:343–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noto JM, Gaddy JA, Lee JY et al. Iron deficiency accelerates Helicobacter pylori-induced carcinogenesis in rodents and humans. J Clin Invest 2013;123:479–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noto JM, Lee JY, Gaddy JA et al. Regulation of Helicobacter pylori virulence within the context of iron deficiency. J Infect Dis 2014;211:1790–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenbreit S, Püls J, Sedlmaier B et al. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science 2000;287:1497–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olbermann P, Josenhans C, Moodley Y et al. A global overview of the genetic and functional diversity in the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. PLoS Genet 2010;6:e1001069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker GA, Gilmore CJ, Dubois A. Spontaneous gastric ulcers in a rhesus monkey. Brain Res Bull 1981;6:445–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Perez GI, Salomaa A, Kosunen TU et al. Evidence that cagA(+) Helicobacter pylori strains are disappearing more rapidly than cagA(−) strains. Gut 2002;50:295–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pich OQ, Carpenter BM, Gilbreath JJ et al. Detailed analysis of Helicobacter pylori Fur-regulated promoters reveals a Fur box core sequence and novel Fur-regulated genes. Mol Microbiol 2012;84:921–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabry MA, Abdel-Moein KA, Seleem A. Evidence of zoonotic transmission of Helicobacter canis between sheep and human contacts. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2016;16:650–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha A, Hammond CE, Beeson C et al. Helicobacter pylori represses proton pump expression and inhibits acid secretion in human gastric mucosa. Gut 2010;59:874–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smet A, Van Nieuwerburgh F, Ledesma J et al. Genome sequence of Helicobacter heilmannii sensu stricto ASB1 isolated from the gastric mucosa of a kitten with severe gastritis. Genome Announc 2013;1:e00033–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solnick JV, Chang K, Canfield DR et al. Natural acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection in newborn rhesus macaques. J Clin Microbiol 2003;41:5511–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solnick JV, Eaton KA, Peek RM. Animal Models of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Backert S, Yamaoka Y. Helicobacter pylori Research: From Bench to Bedside Springer; Japan: 2016, 273–97 [Google Scholar]

- Tan S, Noto JM, Romero-Gallo J et al. Helicobacter pylori perturbs iron trafficking in the epithelium to grow on the cell surface. PLoS Pathog 2011;7:e1002050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 1997;388:539–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermoote M, Vandekerckhove TT, Flahou B et al. Genome sequence of Helicobacter suis supports its role in gastric pathology. Vet Res 2011;42:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viala J, Chaput C, Boneca IG et al. Nod1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nat Immunol 2004;5:1166–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewski LE, Peek RM, Wilson KT. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: factors that modulate disease risk. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010;23:713–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]