Abstract

Background

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is the most common form of inherited retinal dystrophy presenting remarkable genetic heterogeneity. Genetic annotations would help with better clinical assessments and benefit gene therapy, and therefore should be recommended for RP patients. This report reveals the disease causing mutations in two RP pedigrees with confusing inheritance patterns using whole exome sequencing (WES).

Methods

Twenty-five participants including eight patients from two families were recruited and received comprehensive ophthalmic evaluations. WES was applied for mutation identification. Bioinformatics annotations, intrafamilial co-segregation tests, and in silico analyses were subsequently conducted for mutation verification.

Results

All patients were clinically diagnosed with RP. The first family included two siblings born to parents with consanguineous marriage; however, no potential pathogenic variant was found shared by both patients. Further analysis revealed that the female patient carried a recurrent homozygous C8ORF37 p.W185*, while the male patient had hemizygous OFD1 p.T120A. The second family was found to segregate mutations in two genes, TULP1 and RP1. Two patients born to consanguineous marriage carried homozygous TULP1 p.R419W, while a recurrent heterozygous RP1 p.L762Yfs*17 was found in another four patients presenting an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Crystal structural analysis further indicated that the substitution from arginine to tryptophan at the highly conserved residue 419 of TULP1 could lead to the elimination of two hydrogen bonds between residue 419 and residues V488 and S534. All four genes, including C8ORF37, OFD1, TULP1 and RP1, have been previously implicated in RP etiology.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates the coexistence of diverse inheritance modes and mutations affecting distinct disease causing genes in two RP families with consanguineous marriage. Our data provide novel insights into assessments of complicated pedigrees, reinforce the genetic complexity of RP, and highlight the need for extensive molecular evaluations in such challenging families with diverse inheritance modes and mutations.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12967-018-1522-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Retinitis pigmentosa, Genetic heterogeneity, Next generation sequencing, Mutation, OFD1, C8ORF37, TULP1, RP1, Consanguinity

Background

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP, MIM: 268000), the most common form of inherited retinal degenerations, affects over one million individuals globally [1, 2]. Night blindness is usually the initial symptom for RP, followed by subsequent visual field constriction, and eventual vision loss. RP is featured by great clinical heterogeneities. Its onset age ranges from early childhood to mid-adulthood. Inter- and intra-familial phenotypic diversities caused by the same RP causing mutations have also been revealed [3–5]. Thus, clinical diagnose for RP patients are sometimes challenged by its wide phenotypic spectrum and under certain conditions, like in a young patient without fully onset RP phenotypes. In such situations, molecular testing could help to address the clinical ambiguity in RP diagnosis. RP also shows high genetic heterogeneity. To date, 83 RP causing genes involving hundreds of mutations have been identified (RetNet). Next-generation sequencing (NGS), enabling simultaneous parallel sequencing of numerous genes with high efficiency, is an efficient tool for molecular diagnosis of RP [2, 4]. Genetic annotations with NGS promote better clinical assessments and gene therapy, and therefore should be recommended for RP patients. However, pedigrees with puzzling inheritance patterns could sometimes confuse the genetic diagnoses. Herein, we described the genotypic and phenotypic findings in two complicated RP pedigrees using NGS. Distinct inheritance patterns and RP causing genes/mutations were found in both families.

Methods

Sample collection and clinical assessments

Our study, conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved and prospectively reviewed by the local ethics committee of People Hospital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (No. 10 [2017]). Eleven participants from family A (Fig. 1a) and 14 participants from family B (Fig. 1b) were recruited from the People’s Hospital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. Written informed contents were obtained from all participants or their legal guardians before their enrollments. Peripheral blood samples were collected from all 25 participants for genomic DNA extraction. Family history and consanguineous marriages were carefully reviewed. Medical records were obtained from all participants. Each participant received general ophthalmic evaluations, while comprehensive ophthalmic examinations were selectively conducted on the eight included patients. Another 150 Chinese healthy controls free of major ocular problems were recruited with their blood samples donated.

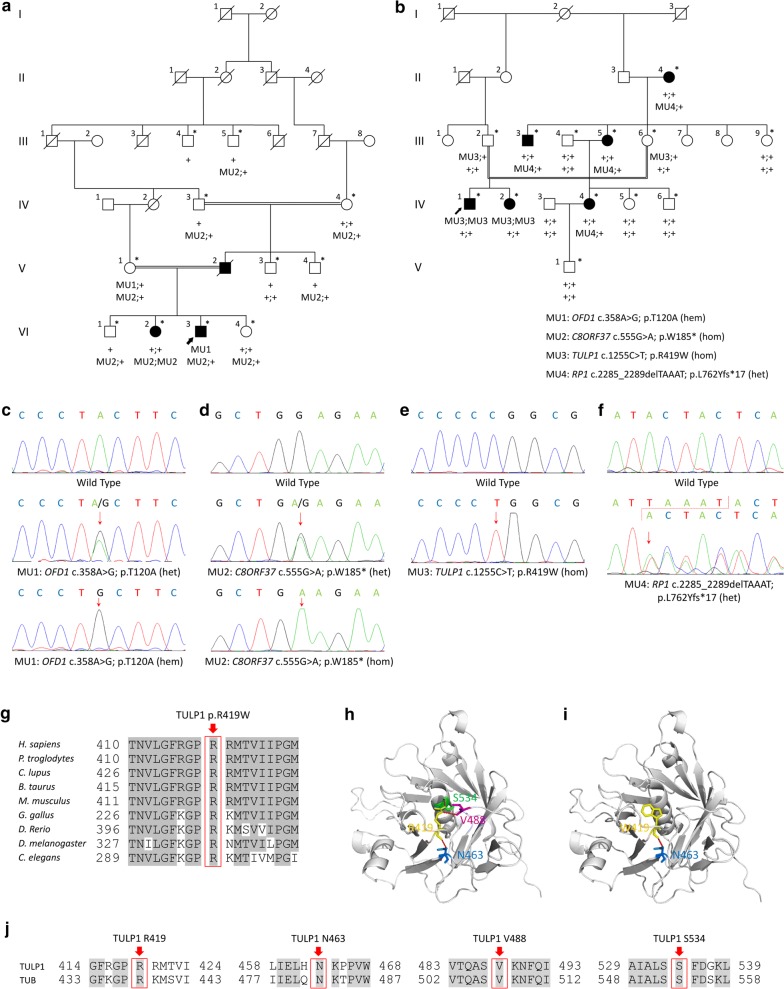

Fig. 1.

Family pedigrees and genetic annotations of identified mutations. a Pedigree of family A. Included participants are indicated by asterisk. b Pedigree of family B. Included participants are indicated by asterisk. c–f Sequence chromatograms of identified mutations, including OFD1 c.358A>G (c), C8ORF37 c.555G>A (d), TULP1 c.1255C>T (e), and RP1 c.2285_2289delTAAAT (f). g Orthologous protein sequence alignment of TULP1 from human (H. sapiens), chimpanzees (P. troglodytes), dogs (C. lupus), cows (B. taurus), rats (M. musculus), chickens (G. gallus), zebrafish (D. rerio), fruit flies (D. melanogaster), and worms (C. elegans). Conserved residues are shaded. The mutated residue 419 is boxed and indicated. h, i Crystal structural analysis of the wild type (h) and mutant (i) TULP1 protein. Hydrogen bonds between residue 419 and residues V488 and S534 were eliminated due to the substitution from arginine to tryptophan. j Conservational analysis of residues TULP1 R419, N463, V488 and S534 between TULP1 and TUB proteins

NGS approach and bioinformatics analyses

To reveal the disease causing mutation in the two families, we selectively performed whole exome sequencing (WES) on three participants in family A (A-IV:3, A-VI:2 and A-VI:3) and two patients in family B (B-III:4 and B-IV:1). WES was conducted with the 44.1 megabases SeqCap EZ Human Exome Library v2.0 (Roche NimbleGen, Madison, WI) for enrichment of 23588 genes on patients from family A [6], and with SureSelect Human All Exon V6 60 Mb Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) on patients from family B [7]. Briefly, qualified genomic DNA samples were randomly sheared by Covaris into 200–250 base pair (bp) fragments. Fragments were then ligated with adapters to both ends, amplified by ligation-mediated polymerase chain reaction (LM-PCR), purified, and hybridized. Non-hybridized fragments were then washed out. Quantitative PCR was further applied to estimate the magnitude of enrichment of both non-captured and captured LM-PCR products. Each post-capture library was then loaded on an Illumina Hiseq 2000 platform for high-throughput sequencing.

Raw data were initially processed by CASAVA Software 1.7 (Illumina) for image analysis and base calling. Sequences were generated as 90 bp pair-end reads. Reads were aligned to human h19 genome using SOAPaligner (http://www.soap.genomics.org.cn) and Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA; http://www.bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/). Only mapped reads were included for subsequent analysis. Coverage and depth were determined based on all mapped reads and the exome region. Atlas-SNP2 and Atlas-Indel2 were applied for variant calling [8]. Variant frequency data were obtained from the following six single nucleotide polymorphism databases, including dbSNP144 (http://www.hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/database/snp135.txt.gz.), HapMap Project (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/hapmap), 1000 Genome Project (ftp://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp), YH database (http://yh.genomics.org.cn/), Exome Variant Server (http://www.evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), and Exome Aggregation Consortium (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/). Variants with a minor allele frequency of over 1% in any of the above databases were discarded. Sanger sequencing was employed for mutation validation and prevalence test in 150 additional controls using a previously defined protocol [9]. Primer information is detailed in Additional file 1: Table S1 and Additional file 2: Table S2.

In silico analysis

We applied vector NTI Advance™ 2011 software (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to analyze the conservation of the mutated reside by aligning protein sequence of human TULP1 (ENSP00000229771) with sequences of the following orthologues proteins: P. troglodytes (ENSPTRP00000030898), C. lupus (ENSCAFP00000001922), B. taurus (ENSBTAP00000055698), M. musculus (ENSMUSP00000049070), G. gallus (ENSGALP00000010281), D. rerio (ENSDARP00000099556), D. melanogaster (FBpp0088961), and C. elegans (F10B5.4). Crystal structural modeling of the wild type and mutant TULP1 proteins were constructed with SWISS-MODEL online server [10, 11], and displayed with PyMol software.

Results

Clinical findings

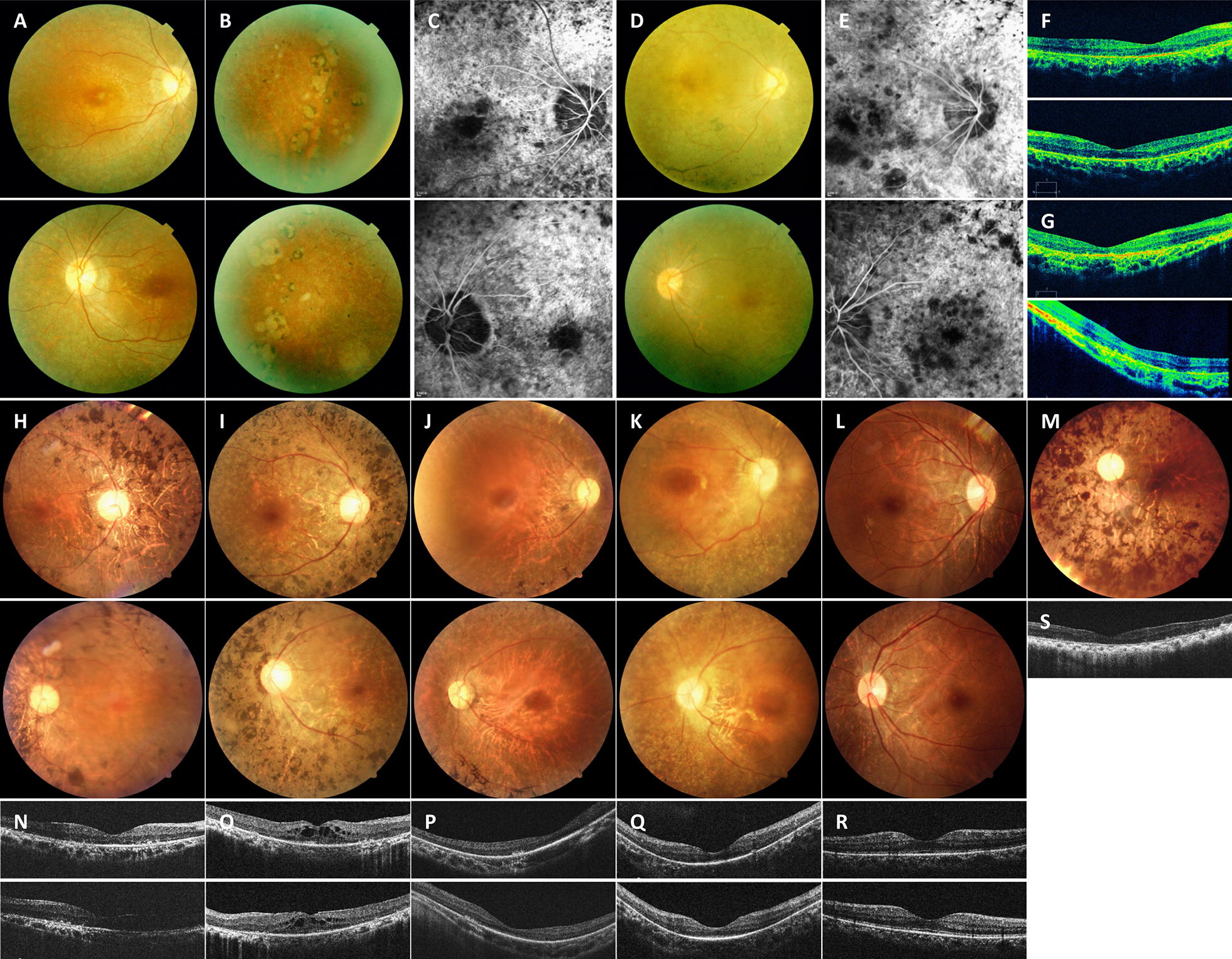

Two patients from family A, A-VI:2 and A-VI:3, and six patients from family B, B-II:4, B-III:3, B-III:5, B-IV:1, B-IV:2 and B-IV:4, were included in the present study with their clinical details summarized in Table 1. Ophthalmic features of patient A-V:2 were obtained according to his medical records, and were presented in Table 1. All patients from the two families were clinically diagnosed with RP. In family A, all three patients had early onset nyctalopia and rapid disease progress. Best corrected visual acuity was light perception for both patients A-VI:2 and A-VI:3 at their last visit to our hospital at the ages of 25 and 24 respectively. Typical RP presentations and macular degeneration were detected upon their ophthalmic evaluations (Fig. 2A–G and Table 1). In family B, RP onset ages ranged from early childhood to 50 years old (Table 1). RP progression also varied among the 6 patients. Patients B-IV:1 and B-IV:2 reported to have nyctalopia since early childhood, while the other four patients showed RP symptoms elder than 30-year-old. On examination, typical RP presentations were detected for all 6 patients, while patient B-II:4 also had chronic angle closure glaucoma in her right eye (Fig. 2H–S). Noteworthy, all 6 patients presented mild to severe cataracts (Table 1). Patient B-III:3 received bilateral cataract surgeries 2 years ago. No systemic defect was noticed in any of the included patients.

Table 1.

Clinical features of attainable patients

| Family member ID | RP causative gene | Age (year)/sex | Onset age (year) | Night blindness | Cataract | BCVA (logMAR) | Fundus appearance | ERG | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O.D. | O.S. | |||||||||||||||||

| O.D. | O.S. | O.D. | O.S. | MD | OD | AA | PD | MD | OD | AA | PD | O.D. | O.S. | |||||

| A-V:2a | – | – | 10 | Yes | – | – | LP | LP | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| A-VI:2 | C8ORF37 | 25/F | 8 | Yes | No | No | LP | LP | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | D | D |

| A-VI:3 | OFD1 | 24/M | 2 | Yes | No | No | LP | LP | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | D | D |

| B-II:4 | RP1 | 80/F | 50 | Yes | Severe | Severe | NLP | LP | – | – | – | – | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | – | D |

| B-III:3 | RP1 | 59/M | 30 | Yes | IOL | IOL | 0.6 | 0.25 | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | D | D |

| B-III:5 | RP1 | 54/F | 35 | Yes | Mild | Mild | 0.3 | 0.3 | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | D | D |

| B-IV:1 | TULP1 | 27/M | EC | Yes | Moderate | Moderate | 0.15 | 0.2 | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | D | D |

| B-IV:2 | TULP1 | 24/F | EC | Yes | Moderate | Moderate | 0.3 | 0.3 | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Waxy | Yes | Yes | D | D |

| B-IV:4 | RP1 | 31/F | – | Yes | No | No | 0.5 | 0.8 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | R | R |

F female, M male, EC early childhood, BCVA best corrected visual acuity, logMAR logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution, O.D. right eye, O.S. left eye, IOL intraocular lens, LP light perception, NLP non-light perception, MD macular degeneration, OD optic disk, AA artery attenuation, PD pigment deposits, ERG electroretinography, D diminished, R reduced

aThis patient is deceased. His clinical features are obtained based on his medical records

Fig. 2.

Ophthalmic presentations of included patients. A, B Fundus presentations of patient A-VI:3 (age 24, carrying OFD1 c.358A>G) indicate waxy optic disc, attenuated retinal arterioles, macular degeneration, bone spicule-like pigments and atrophy of RPE and choroid in the peripheral retina. C Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) of patient A-VI:3 notices a combination of speckled hypofluorescent and hyperfluorescent changes in both macular and peripheral retina. D Fundus photos of patient A-VI:2 (age 27, carrying C8ORF37 c.555G>A) show similar presentations to patient A-VI:3, but with more intensive pigmentations. E FFA of patient A-VI:2 also demonstrates intensive speckled changes of both hypofluorescence and hyperfluorescence. F OCT results of patient A-VI:3 indicate attenuated outer nuclear layer (ONL) and RPE with remarkable loss of inner segments (IS) and outer segments (OS). G OCT results of patient A-VI:2 show complete loss of IS and OS. H Patient B-III:3 (age 59, carrying RP1 c.2285_2289delTAAAT) has a waxy optic disc, attenuated retinal arterioles, mild macular degeneration, and intensive bone spicule-like pigment deposits in the mid-peripheral retina of both eyes. I Patient B-III:5 (age 54, carrying RP1 c.2285_2289delTAAAT) shows typical RP fundus similar to patient B-III:3, including intensive pigmentations and macular degeneration. J Fundus of patient B-IV:1 (age 27, carrying TULP1 c.1255C>T) demonstrates attenuated retinal vessels, a waxy optic disc, remarkable macular degeneration, and diffuse pigment deposits in the periphery retina of both eyes. K Patient B-IV:2 (age 24, carrying TULP1 c.1255C>T) shows similar fundus presentation to patient B-IV:1, presenting maculopathy and diffused pigmentations. L Slight waxy pallor of the optic disc and diffuse pigment deposits in the peripheral retina are revealed in the fundus of patient IV:4 (age 31, carrying RP1 c.2285_2289delTAAAT). M Patient II:4 (age 80, carrying RP1 c.2285_2289delTAAAT) shows typical RP fundus with intensive pigment deposits. N OCT results of patient B-III:3 indicate attenuated ONL and RPE with loss of IS and OS. O Thickened ONL with cystic cavities in the macular region were noticed by OCT in patient B-III:5. P OCT examinations of patient B-IV:1 demonstrate attenuated ONL and RPE with complete loss of IS and OS. Q Patient B-IV:2 shows similar OCT results to patient B-IV:1, including attenuated ONL and RPE, and loss of IS/OS. R Slightly attenuated ONL is presented in patient B-IV:4. S Typical RP presentations are revealed in patient B-II:4, demonstrating attenuated ONL and RPE with loss of IS and OS

Genetic assessments

To identify the pathogenic mutations, WES with high quality was selectively performed on individuals A-IV:3, A-VI:2, and A-VI:3 from family A (mean coverage: 98.16%; mean depth: 70.89×), and patients B-III:5 and B-IV:1 from family B (mean coverage: 98.32%; mean depth: 104.66×). NGS data were summarized in Additional file 3: Table S3. Exon-specific coverage report of all known RP genes was presented in Additional file 4: Table S4. For family A, patients A-VI:2 and A-VI:3 were born to parents with consanguineous marriage, supporting potential autosomal recessive inheritance. WES identified 10 homozygous variants and 6 compound heterozygous variants shared by patients A-VI:2 and A-VI:3 (Additional file 1: Table S1). However, Sanger sequencing revealed no variant co-segregated with the disease phenotype. We thus hypothesized that the two patients may have distinct RP causing mutations. Based on WES data, patient A-VI:2 carried a recurrent homozygous C8ORF37 mutation c.555G>A (p.W185*; Fig. 1d and Table 2), while patient A-VI:3 had a novel hemizygous OFD1 mutation c.358A>G (p.T120A; Fig. 1c and Table 2).

Table 2.

Mutations identified in this study

| Gene | Variation | Status | Bioinformatics analysis | Reported or Novel | Population prevalence (allele count) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | SIFT | PolyPhen | PROVEN | rs no. | gnomAD | EXAC | |||

| C8ORF37 | c.555G>A | p.W185* | Hom | NA | NA | NA | Novel | rs748014296 | 2/246148 | 1/121412 |

| OFD1 | c.358A>G | p.T120A | Hem | 0.63 (tolerated) | 0.006 (benign) | − 0.616 (netural) | Novel | rs755625951 | 4/178544 | 1/121388 |

| TULP1 | c.1255C>T | p.R419W | Hom | 0 (damaging) | 1 (probably damaging) | − 7.976 (deleterious) | Novel | rs775334320 | 12/217192 | 6/121222 |

| RP1 | c.2285_2289delTAAAT | p.L762Yfs*17 | Het | NA | NA | NA | Novel | NA | NA | NA |

Hom homozygous, Hem hemizygous, Het heterozygous, NA not available

SIFT: http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/; PolyPhen: http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/; PROVEN: http://provean.jcvi.org/index.php; gnomAD: http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/; EXAC: http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

As to family B, WES revealed one homozygous variant and 18 compound heterozygous variants shared by patients B-III:4 and IV:2 (Additional file 2: Table S2), while no variant was validated co-segregated with the disease phenotype. According to the family pedigree, patients B-IV:1 and B-IV:2 were born to unaffected parents with consanguineous marriage, indicating a potential autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. However, the RP phenotypes of patients B-III:3 and B-III:4 were likely inherited from the affected mother B-II:4, suggesting a dominant inheritance mode. Upon this hypothesis, a novel homozygous TULP1 mutation c.1255C>T (p.R419W; Fig. 1e and Table 2) was revealed as RP causative for patients B-IV:1 and B-IV:2, and a recurrent heterozygous RP1 mutation c.2285_2289delTAAAT (p.L762Yfs*17; Fig. 1f; Table 2) was found in patients B-II:4, B-III:3 and B-III:4. The mutated residue R419 in TULP1 was highly conserved among all tested species (Fig. 1g). Crystal structures of the wild type and mutant TULP1 proteins were obtained based on human TUB protein (Protein Data Bank ID: 1S31) with a sequence identify of 75.19 and a sequence similarity of 0.54. Our data suggested that the substitution from arginine to tryptophan at residue 419 would lead to the elimination of two hydrogen bonds between residue 419 and residues V488 and S534 (Fig. 1h, i), further supporting that this mutation would disturb the tertiary structure of TULP1 and interrupt its function. Residues R419, N463, V488 and S534 were conserved between TULP1 and TUB proteins (Fig. 1j). All four mutations identified in the two families segregated with the disease phenotype (Fig. 1a, b), and were confirmed absent in 150 Chinese controls free of major ocular problems.

Discussion

RP is a genetically heterogeneous disease with 83 disease causative genes and hundreds of mutations. In this report, molecular test reveals the coexistence of mutations affecting distinct RP causing genes in two RP families, thus providing novel insights into genetic assessments in complicated pedigrees. Among the four mutations identified in the two families, two were novel (OFD1 p.T120A and TULP1 p.R419W) and two were recurrent (C8ORF37 p.W185* and RP1 p.L762Yfs*17 [Human Gene Mutation Database ID: CD991855]).

OFD1 mutations have been reported to cause X-linked recessive Joubert syndrome, orofaciodigital syndrome and isolated RP (Table 3) [12, 13]. OFD1, protein encoded by the OFD1 gene, is a crucial component of the centrioles. OFD1 is involved in ciliogenesis regulation and exhibits neuroprotective roles [14]. Herein, a hemizygous OFD1 missense mutation is associated with a severe form of RP presenting early onset age and fast disease progression. C8ORF37 mutations correlate with a wide spectrum of autosomal recessive retinopathies ranging from RP to Bardet-Biedl syndrome (Table 3) [15–22]. The encoded C8ORF37 protein is a ciliary protein located at the base of the photoreceptor connecting cilia [16], while its role in modulating retinal function is not fully elucidated. In this study, the patient carrying homozygous nonsense C8ORF37 mutation presents early onset RP with macular involvement, which is similar to previous reports [15, 17]. TULP1 mutations are implicated in autosomal recessive RP and LCA etiologies (Table 3) [22–57]. TULP1 protein plays crucial roles in maintaining retinal homeostasis. According to previous reports, TULP1 interacts and co-localizes with F-actin in photoreceptor cells of bovine retina [58], and RPE phagocytosis ability was remarkably reduced in TULP1−/− mice [59]. Thus, TULP1 is required for maintaining regular functions of photoreceptors and RPE cells. We herein identified TULP1 mutations in two siblings demonstrating RP with early onset and quick progression. Further confirmatory functional studies are still needed to better illustrated pathogenesis of the identified novel mutations.

Table 3.

List of mutations reported in C8ORF37, OFD1 and TULP1 associated retinopathies

| Gene | Variation | Disease | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | Domain | |||

| C8ORF37 | c.155+2T>C | – | – | CRD | [56] |

| C8ORF37 | c.156−2A>G | – | – | CRD | [15, 18] |

| C8ORF37 | c.243+2T>C | – | – | RP | [21] |

| C8ORF37 | c.244−2A>C | – | – | RP | [17] |

| C8ORF37 | c.374+2T>C | – | – | EORD | [20] |

| C8ORF37 | c.497>A | p.L166* | – | RP | [15, 18] |

| C8ORF37 | c.529C>T | p.R177W | – | CRD, BBS | [15, 18, 19, 22] |

| C8ORF37 | c.545A>G | p.Q182R | – | RP | [15, 18] |

| C8ORF37 | c.555G>A | p.W185* | – | RP | [17], this study |

| C8ORF37 | c.575delC | p.T192Mfs*28 | – | EORD | [20] |

| OFD1 | p.T120A | – | RP | This study | |

| OFD1 | IVS9+706A>G | p.N313fs*330 | Coiled coil domain | RP | [13] |

| TULP1 | c.3G>A | p.M1I | – | RP | [25] |

| TULP1 | c.99+1G>A | – | – | LCA, RP | [23, 26] |

| TULP1 | c.280G>T | p.D94Y | – | LCA | [27] |

| TULP1 | c.286_287delGA | p.E96Gfs*77 | – | RP | [57] |

| TULP1 | c.350−2delAGA | – | – | RP | [28] |

| TULP1 | c.394_417del | p.E120_D127del | – | RP | [29] |

| TULP1 | c.539G>A | p.R180H | – | LCA | [30] |

| TULP1 | c.627delC | p.S210Qfs*27 | – | LCA | [31] |

| TULP1 | c.629C>G | p.S210* | – | RP | [32] |

| TULP1 | c.718+2T>C | – | – | LCA, RP | [33] |

| TULP1 | c.725_728delCCAA | p.P242Qfs*16 | – | LCA | [34] |

| TULP1 | c.901C>T | p.Q301* | Tubby domain | LCA, CRD | [35, 36] |

| TULP1 | c.937delC | p.Q301fs*9 | Tubby domain | RP | [28] |

| TULP1 | c.932G>A | p.R311Q | Tubby domain | RP | [37] |

| TULP1 | c.956G>A | p.G319D | Tubby domain | RP | [38] |

| TULP1 | c.961T>G | p.Y321D | Tubby domain | LCA | [34] |

| TULP1 | c.999+5G>C | – | Tubby domain | LCA, RP | [33] |

| TULP1 | c.1025G>A | p.R342Q | Tubby domain | RP | [37] |

| TULP1 | c.1047T>G | p.N349K | Tubby domain | RP | [39] |

| TULP1 | c.1064A>T | p.D355V | Tubby domain | LCA | [34] |

| TULP1 | c.1087G>A | p.G363R | Tubby domain | CRD | [40] |

| TULP1 | c.1081C>T | p.R361* | Tubby domain | LCA | [41] |

| TULP1 | c.1102G>T | p.G368W | Tubby domain | LCA | [26] |

| TULP1 | c.1112+2T>C | – | Tubby domain | RP | [42] |

| TULP1 | c.1113–2A>C | – | Tubby domain | LCA | [34] |

| TULP1 | c.1138A>G | p.T380A | Tubby domain | LCA, RP | [43, 45, 46] |

| TULP1 | c.1145T>C | p.F382S | Tubby domain | RP | [47] |

| TULP1 | c.1198C>T | p.R400W | Tubby domain | LCA, RP, CRD | [26, 48, 49] |

| TULP1 | c.1199G>A | p.A400Q | Tubby domain | RP | [50] |

| TULP1 | c.1204G>T | p.E402* | Tubby domain | LCA | [26] |

| TULP1 | c.1224+4A>G | – | Tubby domain | RP | [29] |

| TULP1 | c.1246C > T | p.R416C | Tubby domain | RP | [25] |

| TULP1 | c.1255C>T | p.R419W | Tubby domain | RP | This study |

| TULP1 | c.1258C>A | p.R420S | Tubby domain | RCD | [51] |

| TULP1 | c.1259G>C | p.R420P | Tubby domain | RP | [23] |

| TULP1 | c.1318C>T | p.R440* | Tubby domain | LCA | [31] |

| TULP1 | c.1349G>A | p.W450* | Tubby domain | LCA | [27] |

| TULP1 | c.1376T>A | p.I459K | Tubby domain | RP | [23, 24] |

| TULP1 | c.1376T>C | p.I459T | Tubby domain | RP | [42] |

| TULP1 | c.1376_1377delTA | p.I459Rfs*12 | Tubby domain | LCA | [34] |

| TULP1 | c.1381C>G | p.L461V | Tubby domain | LCA, RP | [33] |

| TULP1 | c.1444C > T | p.R482W | Tubby domain | RP | [44, 48] |

| TULP1 | c.1445G>A | p.A482Q | Tubby domain | RP | [46] |

| TULP1 | c.1466A>G | p.K489R | Tubby domain | RP | [29, 43, 52, 57] |

| TULP1 | c.1472T>C | p.F491L | Tubby domain | RP | [23] |

| TULP1 | c.1495+1G>A | – | Tubby domain | RP | [24] |

| TULP1 | c.1495+2_1495+3insT | – | Tubby domain | RP | [53] |

| TULP1 | c.1495+4A>C | – | Tubby domain | RP | [57] |

| TULP1 | c.1496−6C>A | – | Tubby domain | RP | [23, 29] |

| TULP1 | c.1511_1521del | p.L504fs*140 | Tubby domain | RP | [44] |

| TULP1 | c.1518C>A | p.F506L | Tubby domain | LCA | [31] |

| TULP1 | c.1561C>T | p.P521S | Tubby domain | RP | [57] |

| TULP1 | c.1582_1587dup | p.F528_A529dup | Tubby domain | LCA, RP | [54] |

| TULP1 | c.1604T>C | p.F535S | Tubby domain | LCA | [55] |

CRD cone-rod dystrophy, RP retinitis pigmentosa, EORD early-onset retinal dystrophy, BBS Bardet–Biedl syndrome, LCA Leber congenital amaurosis

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrate the coexistence of diverse inheritance modes and mutations affecting distinct disease causing genes in two RP families. Our findings reinforce the genetic complexity of RP, provide novel insights into the assessments of complicated pedigrees with consanguinity, and highlight the need for extensive molecular evaluations in such challenging families involving diverse inheritance modes and mutations.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1. Post-filtration variants in family A.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Post-filtration variants in family B.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Overview of data production.

Additional file 4: Table S4. Coverage for all exons in all known RP genes.

Authors’ contributions

XC, XS, YL, and ZL contributed equally to this report. All authors were involved in managing the patients. XC, BY and CZ wrote the report. XC, XS, YL and ZL did the genetic analysis and whole exome sequencing, and CZ reviewed the genetic results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients and their family members for their participation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Yes.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study, conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved and prospectively reviewed by the local ethics committee of People Hospital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. Written informed contents were obtained from all participants or their legal guardians before their enrollments.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81525006, 81670864 and 81730025 to C. Z., 81700877 to X. C., and 81760180 to X. S.); Shanghai Outstanding Academic Leaders (2017BR013 to C. Z.); Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20171087 to X. C.); the Key Technology R&D Program of Ningxia Province (2014ZYH65 to X. S.); Open Foundation of State Key Laboratory of Reproductive Medicine (Nanjing Medical University, SKLRM-KA201607 to X. C.) and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- RP

retinitis pigmentosa

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- WES

whole exome sequencing

- bp

base pair

- LM-PCR

ligation-mediated polymerase chain reaction

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

Footnotes

Xue Chen, Xunlun Sheng, Yani Liu and Zili Li contributed equally to this work

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12967-018-1522-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Xue Chen, Email: drcx1990@163.com.

Xunlun Sheng, Email: shengxunlun@163.com.

Yani Liu, Email: yani.2007.happy@163.com.

Zili Li, Email: lzlhou@126.com.

Xiantao Sun, Email: sunxt38019896@163.com.

Chao Jiang, Email: jc_484@163.com.

Rui Qi, Email: qirui0106vip@163.com.

Shiqin Yuan, Email: shiqinyuan@yeah.net.

Xuhui Wang, Email: wangxuhui1618@163.com.

Ge Zhou, Email: 354636568@qq.com.

Yanyan Zhen, Email: 397826852@qq.com.

Ping Xie, Email: xieping9@126.com.

Qinghuai Liu, Email: liuqh@njmu.edu.cn.

Biao Yan, Email: yanbiao1982@hotmail.com.

Chen Zhao, Email: dr_zhaochen@163.com.

References

- 1.Anasagasti A, Irigoyen C, Barandika O, de Munain AL, Ruiz-Ederra J. Current mutation discovery approaches in retinitis pigmentosa. Vis Res. 2012;75:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Chen X, Xu Q, Gao X, Tam PO, Zhao K, Zhang X, Chen LJ, Jia W, Zhao Q, et al. SPP2 mutations cause autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14867. doi: 10.1038/srep14867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 2006;368:1795–1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu X, Xiao J, Huang H, Guan L, Zhao K, Xu Q, Zhang X, Pan X, Gu S, Chen Y, et al. Molecular genetic testing in clinical diagnostic assessments that demonstrate correlations in patients with autosomal recessive inherited retinal dystrophy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:427–436. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.5831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X, Sheng X, Liu X, Li H, Liu Y, Rong W, Ha S, Liu W, Kang X, Zhao K, Zhao C. Targeted next-generation sequencing reveals novel USH2A mutations associated with diverse disease phenotypes: implications for clinical and molecular diagnosis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e105439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheng X, Chen X, Lei B, Chen R, Wang H, Zhang F, Rong W, Ha R, Liu Y, Zhao F, et al. Whole exome sequencing confirms the clinical diagnosis of Marfan syndrome combined with X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Transl Med. 2015;13:179. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0534-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X, Sheng X, Zhuang W, Sun X, Liu G, Shi X, Huang G, Mei Y, Li Y, Pan X, et al. GUCA1A mutation causes maculopathy in a five-generation family with a wide spectrum of severity. Genet Med. 2017;19:945–954. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Challis D, Yu J, Evani US, Jackson AR, Paithankar S, Coarfa C, Milosavljevic A, Gibbs RA, Yu F. An integrative variant analysis suite for whole exome next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinform. 2012;13:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao C, Lu S, Zhou X, Zhang X, Zhao K, Larsson C. A novel locus (RP33) for autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa mapping to chromosomal region 2cen-q12.1. Hum Genet. 2006;119:617–623. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDowall J, Hunter S. InterPro protein classification. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;694:37–47. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-977-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coene KL, Roepman R, Doherty D, Afroze B, Kroes HY, Letteboer SJ, Ngu LH, Budny B, van Wijk E, Gorden NT, et al. OFD1 is mutated in X-linked Joubert syndrome and interacts with LCA5-encoded lebercilin. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:465–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webb TR, Parfitt DA, Gardner JC, Martinez A, Bevilacqua D, Davidson AE, Zito I, Thiselton DL, Ressa JH, Apergi M, et al. Deep intronic mutation in OFD1, identified by targeted genomic next-generation sequencing, causes a severe form of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP23) Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3647–3654. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Chen X, Wang F, Zhang J, Li P, Li Z, Xu J, Gao F, Jin C, Tian H, et al. OFD1, as a ciliary protein, exhibits neuroprotective function in photoreceptor degeneration models. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0155860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estrada-Cuzcano A, Neveling K, Kohl S, Banin E, Rotenstreich Y, Sharon D, Falik-Zaccai TC, Hipp S, Roepman R, Wissinger B, et al. Mutations in C8orf37, encoding a ciliary protein, are associated with autosomal-recessive retinal dystrophies with early macular involvement. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heon E, Kim G, Qin S, Garrison JE, Tavares E, Vincent A, Nuangchamnong N, Scott CA, Slusarski DC, Sheffield VC. Mutations in C8ORF37 cause Bardet Biedl syndrome (BBS21) Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:2283–2294. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ravesh Z, El Asrag ME, Weisschuh N, McKibbin M, Reuter P, Watson CM, Baumann B, Poulter JA, Sajid S, Panagiotou ES, et al. Novel C8orf37 mutations cause retinitis pigmentosa in consanguineous families of Pakistani origin. Mol Vis. 2015;21:236–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Huet RA, Estrada-Cuzcano A, Banin E, Rotenstreich Y, Hipp S, Kohl S, Hoyng CB, den Hollander AI, Collin RW, Klevering BJ. Clinical characteristics of rod and cone photoreceptor dystrophies in patients with mutations in the C8orf37 gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:4683–4690. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan AO, Decker E, Bachmann N, Bolz HJ, Bergmann C. C8orf37 is mutated in Bardet-Biedl syndrome and constitutes a locus allelic to non-syndromic retinal dystrophies. Ophthalmic Genet. 2016;37:290–293. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2015.1066830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katagiri S, Hayashi T, Yoshitake K, Akahori M, Ikeo K, Gekka T, Tsuneoka H, Iwata T. Novel C8orf37 mutations in patients with early-onset retinal dystrophy, macular atrophy, cataracts, and high myopia. Ophthalmic Genet. 2016;37:68–75. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2014.949380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jinda W, Taylor TD, Suzuki Y, Thongnoppakhun W, Limwongse C, Lertrit P, Suriyaphol P, Trinavarat A, Atchaneeyasakul LO. Whole exome sequencing in Thai patients with retinitis pigmentosa reveals novel mutations in six genes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:2259–2268. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazar CH, Mutsuddi M, Kimchi A, Zelinger L, Mizrahi-Meissonnier L, Marks-Ohana D, Boleda A, Ratnapriya R, Sharon D, Swaroop A, Banin E. Whole exome sequencing reveals GUCY2D as a major gene associated with cone and cone-rod dystrophy in Israel. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;56:420–430. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagstrom SA, North MA, Nishina PL, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Recessive mutations in the gene encoding the tubby-like protein TULP1 in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 1998;18:174–176. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banerjee P, Kleyn PW, Knowles JA, Lewis CA, Ross BM, Parano E, Kovats SG, Lee JJ, Penchaszadeh GK, Ott J, et al. TULP1 mutation in two extended Dominican kindreds with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 1998;18:177–179. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katagiri S, Akahori M, Sergeev Y, Yoshitake K, Ikeo K, Furuno M, Hayashi T, Kondo M, Ueno S, Tsunoda K, et al. Whole exome analysis identifies frequent CNGA1 mutations in Japanese population with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e108721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanein S, Perrault I, Gerber S, Tanguy G, Barbet F, Ducroq D, Calvas P, Dollfus H, Hamel C, Lopponen T, et al. Leber congenital amaurosis: comprehensive survey of the genetic heterogeneity, refinement of the clinical definition, and genotype-phenotype correlations as a strategy for molecular diagnosis. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:306–317. doi: 10.1002/humu.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beryozkin A, Zelinger L, Bandah-Rozenfeld D, Shevach E, Harel A, Storm T, Sagi M, Eli D, Merin S, Banin E, Sharon D. Identification of mutations causing inherited retinal degenerations in the israeli and palestinian populations using homozygosity mapping. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:1149–1160. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paloma E, Hjelmqvist L, Bayes M, Garcia-Sandoval B, Ayuso C, Balcells S, Gonzalez-Duarte R. Novel mutations in the TULP1 gene causing autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:656–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu S, Lennon A, Li Y, Lorenz B, Fossarello M, North M, Gal A, Wright A. Tubby-like protein-1 mutations in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 1998;351:1103–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez-del Pozo M, Borrego S, Barragan I, Pieras JI, Santoyo J, Matamala N, Naranjo B, Dopazo J, Antinolo G. Mutation screening of multiple genes in Spanish patients with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa by targeted resequencing. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Wang X, Zou X, Xu S, Li H, Soens ZT, Wang K, Li Y, Dong F, Chen R, Sui R. Comprehensive molecular diagnosis of a large Chinese Leber congenital amaurosis cohort. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:3642–3655. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glockle N, Kohl S, Mohr J, Scheurenbrand T, Sprecher A, Weisschuh N, Bernd A, Rudolph G, Schubach M, Poloschek C, et al. Panel-based next generation sequencing as a reliable and efficient technique to detect mutations in unselected patients with retinal dystrophies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:99–104. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.den Hollander AI, Lopez I, Yzer S, Zonneveld MN, Janssen IM, Strom TM, Hehir-Kwa JY, Veltman JA, Arends ML, Meitinger T, et al. Identification of novel mutations in patients with Leber congenital amaurosis and juvenile RP by genome-wide homozygosity mapping with SNP microarrays. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:5690–5698. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Wang H, Sun V, Tuan HF, Keser V, Wang K, Ren H, Lopez I, Zaneveld JE, Siddiqui S, et al. Comprehensive molecular diagnosis of 179 Leber congenital amaurosis and juvenile retinitis pigmentosa patients by targeted next generation sequencing. J Med Genet. 2013;50:674–688. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Wang H, Peng J, Gibbs RA, Lewis RA, Lupski JR, Mardon G, Chen R. Mutation survey of known LCA genes and loci in the Saudi Arabian population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1336–1343. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan AO, Bergmann C, Eisenberger T, Bolz HJ. A TULP1 founder mutation, p.Gln301*, underlies a recognisable congenital rod-cone dystrophy phenotype on the Arabian Peninsula. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:488–492. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hebrard M, Manes G, Bocquet B, Meunier I, Coustes-Chazalette D, Herald E, Senechal A, Bolland-Auge A, Zelenika D, Hamel CP. Combining gene mapping and phenotype assessment for fast mutation finding in non-consanguineous autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa families. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:1256–1263. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Consugar MB, Navarro-Gomez D, Place EM, Bujakowska KM, Sousa ME, Fonseca-Kelly ZD, Taub DG, Janessian M, Wang DY, Au ED, et al. Panel-based genetic diagnostic testing for inherited eye diseases is highly accurate and reproducible, and more sensitive for variant detection, than exome sequencing. Genet Med. 2015;17:253–261. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kannabiran C, Singh H, Sahini N, Jalali S, Mohan G. Mutations in TULP1, NR2E3, and MFRP genes in Indian families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis. 2012;18:1165–1174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boulanger-Scemama E, El Shamieh S, Demontant V, Condroyer C, Antonio A, Michiels C, Boyard F, Saraiva JP, Letexier M, Souied E, et al. Next-generation sequencing applied to a large French cone and cone-rod dystrophy cohort: mutation spectrum and new genotype-phenotype correlation. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:85. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0300-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo Y, Prokudin I, Yu C, Liang J, Xie Y, Flaherty M, Tian L, Crofts S, Wang F, Snyder J, et al. Advantage of whole exome sequencing over allele-specific and targeted segment sequencing in detection of novel TULP1 mutation in Leber congenital amaurosis. Ophthalmic Genet. 2015;36:333–338. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2014.886269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang F, Wang H, Tuan HF, Nguyen DH, Sun V, Keser V, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, Luo H, Zhao L, et al. Next generation sequencing-based molecular diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa: identification of a novel genotype-phenotype correlation and clinical refinements. Hum Genet. 2014;133:331–345. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1381-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iqbal M, Naeem MA, Riazuddin SA, Ali S, Farooq T, Qazi ZA, Khan SN, Husnain T, Riazuddin S, Sieving PA, Hejtmancik JF. Association of pathogenic mutations in TULP1 with retinitis pigmentosa in consanguineous Pakistani families. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:1351–1357. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.den Hollander AI, van Lith-Verhoeven JJ, Arends ML, Strom TM, Cremers FP, Hoyng CB. Novel compound heterozygous TULP1 mutations in a family with severe early-onset retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:932–935. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.7.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKibbin M, Ali M, Mohamed MD, Booth AP, Bishop F, Pal B, Springell K, Raashid Y, Jafri H, Inglehearn CF. Genotype-phenotype correlation for leber congenital amaurosis in Northern Pakistan. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:107–113. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ajmal M, Khan MI, Micheal S, Ahmed W, Shah A, Venselaar H, Bokhari H, Azam A, Waheed NK, Collin RW, et al. Identification of recurrent and novel mutations in TULP1 in Pakistani families with early-onset retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis. 2012;18:1226–1237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kondo H, Qin M, Mizota A, Kondo M, Hayashi H, Hayashi K, Oshima K, Tahira T. A homozygosity-based search for mutations in patients with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa, using microsatellite markers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4433–4439. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Y, Zhang Q, Shen T, Xiao X, Li S, Guan L, Zhang J, Zhu Z, Yin Y, Wang P, et al. Comprehensive mutation analysis by whole-exome sequencing in 41 Chinese families with Leber congenital amaurosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:4351–4357. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV, Huang WC, Sumaroka A, Roman AJ, Schwartz SB, Luo X, Sheplock R, Dauber JM, Swider M, Stone EM. TULP1 mutations causing early-onset retinal degeneration: preserved but insensitive macular cones. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:5354–5364. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh HP, Jalali S, Narayanan R, Kannabiran C. Genetic analysis of Indian families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa by homozygosity screening. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4065–4071. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roosing S, van den Born LI, Hoyng CB, Thiadens AA, de Baere E, Collin RW, Koenekoop RK, Leroy BP, van Moll-Ramirez N, Venselaar H, et al. Maternal uniparental isodisomy of chromosome 6 reveals a TULP1 mutation as a novel cause of cone dysfunction. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1239–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maria M, Ajmal M, Azam M, Waheed NK, Siddiqui SN, Mustafa B, Ayub H, Ali L, Ahmad S, Micheal S, et al. Homozygosity mapping and targeted sanger sequencing reveal genetic defects underlying inherited retinal disease in families from pakistan. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0119806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abbasi AH, Garzozi HJ, Ben-Yosef T. A novel splice-site mutation of TULP1 underlies severe early-onset retinitis pigmentosa in a consanguineous Israeli Muslim Arab family. Mol Vis. 2008;14:675–682. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mataftsi A, Schorderet DF, Chachoua L, Boussalah M, Nouri MT, Barthelmes D, Borruat FX, Munier FL. Novel TULP1 mutation causing Leber congenital amaurosis or early onset retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:5160–5167. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eisenberger T, Neuhaus C, Khan AO, Decker C, Preising MN, Friedburg C, Bieg A, Gliem M, Charbel Issa P, Holz FG, et al. Increasing the yield in targeted next-generation sequencing by implicating CNV analysis, non-coding exons and the overall variant load: the example of retinal dystrophies. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rahner N, Nuernberg G, Finis D, Nuernberg P, Royer-Pokora B. A novel C8orf37 splice mutation and genotype-phenotype correlation for cone-rod dystrophy. Ophthalmic Genet. 2016;37:294–300. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2015.1071408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ullah I, Kabir F, Iqbal M, Gottsch CB, Naeem MA, Assir MZ, Khan SN, Akram J, Riazuddin S, Ayyagari R, et al. Pathogenic mutations in TULP1 responsible for retinitis pigmentosa identified in consanguineous familial cases. Mol Vis. 2016;22:797–815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xi Q, Pauer GJ, Marmorstein AD, Crabb JW, Hagstrom SA. Tubby-like protein 1 (TULP1) interacts with F-actin in photoreceptor cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4754–4761. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caberoy NB, Maiguel D, Kim Y, Li W. Identification of tubby and tubby-like protein 1 as eat-me signals by phage display. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Post-filtration variants in family A.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Post-filtration variants in family B.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Overview of data production.

Additional file 4: Table S4. Coverage for all exons in all known RP genes.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.