Abstract

Background

Carbapenems are the last line of defence against ever more prevalent MDR Gram-negative bacteria, but their efficacy is threatened worldwide by bacteria that produce carbapenemase enzymes. The epidemiology of bacteria producing carbapenemases has been described in considerable detail in Europe, North America and Asia; however, little is known about their spread and clinical relevance in Africa.

Methods

We systematically searched in PubMed, EBSCOhost, Web of Science, Scopus, Elsevier Masson Consulte and African Journals Online, international conference proceedings, published theses and dissertations for studies reporting on carbapenemase-producing bacteria in Africa. We included articles published in English or French up to 28 February 2014. We calculated the prevalence of carbapenemase producers only including studies where the total number of isolates tested was at least 30.

Results

Eighty-three studies were included and analysed. Most studies were conducted in North Africa (74%, 61/83), followed by Southern Africa (12%, 10/83), especially South Africa (90%, 9/10), West Africa (8%, 7/83) and East Africa (6%, 6/83). Carbapenemase-producing bacteria were isolated from humans, the hospital environment and community environmental water samples, but not from animals. The prevalence of carbapenemase-producing isolates in hospital settings ranged from 2.3% to 67.7% in North Africa and from 9% to 60% in sub-Saharan Africa.

Conclusions

Carbapenemase-producing bacteria have been described in many African countries; however, their prevalence is poorly defined and has not been systematically studied. Antibiotic stewardship and surveillance systems, including molecular detection and genotyping of resistant isolates, should be implemented to monitor and reduce the spread of carbapenemase-producing bacteria.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, Gram-negative, β-lactamase, epidemiology

Introduction

MDR bacterial infections have emerged as one of the world's greatest threats due to limited availability of treatment options.1,2 The spread of MDR Gram-negative (MDRGN) bacteria is increasingly reported in both hospital and community settings worldwide.2 Carbapenem antibiotics are effective against MDRGN bacilli, particularly those producing extended-spectrum β-lactamase enzymes, as well as a broad range of Gram-positive bacteria. However, their usefulness is threatened by the emergence and spread of bacteria that produce carbapenemase enzymes.3,4 Infections caused by carbapenemase-producing bacteria are associated with mortality rates as high as 67%, depending on the type of enzyme.5–8 Bacteria that produce carbapenemases are therefore a major public health and clinical concern, and are increasingly reported worldwide, especially within the Enterobacteriaceae family.9–12 As reported in 2012, the prevalence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe is high in Greece, Italy and Turkey, and very low in Nordic countries.13

Based on amino acid homology, carbapenemases can be assigned to three of the four classes of β-lactamases, namely, Ambler classes A, B and D.11,14 These three classes of carbapenemases can also be differentiated based on the hydrolytic mechanism at their active sites. Class A and D carbapenemases are referred to as serine carbapenemases because they have serine (serine dependent) at their active sites, whereas class B carbapenemases have zinc (zinc dependent) at their active site and are referred to as metallo-β-lactamases.11 Ambler class A carbapenemases may be plasmid encoded or chromosomal, and are partially inhibited by clavulanic acid, a β-lactamase inhibitor.11 The KPCs are the most frequently identified class A carbapenemases.2 Class B metallo-β-lactamases are plasmid mediated, or in some cases chromosomal, and the most common enzymes among clinical isolates in this group include VIM, IMP and NDM.11 NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae have been identified as a major concern due to their rapid spread worldwide.15–17 The plasmids harbouring blaNDM-1 gene are very diverse and may carry a number of other resistance determinants.16,17 Class B enzymes are able to hydrolyse all β-lactams except for aztreonam, a monobactam, and their hydrolytic activity is reduced or inhibited by EDTA but not by clavulanic acid.11 Class D enzymes, also referred to as OXA type, can be subdivided into five families, namely the OXA-23, -24/40, -48 and -58 carbapenemases, which are mainly plasmid encoded, and the OXA-51 carbapenemase, which is chromosomally encoded and intrinsic in Acinetobacter baumannii.18 Class D enzymes are not inhibited by clavulanic acid or EDTA.11

Whilst the epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing organisms has been described in considerable detail in Europe, North America and Asia,2,13,19 relatively little is known about their spread and clinical importance in Africa. We therefore did a systematic review of carbapenemase-producing bacteria in African countries, to determine their epidemiology in Africa and to identify areas for further research.

Methods

Literature search in databases

A comprehensive literature search of PubMed, EBSCOhost, Scopus and Web of Science was conducted using relevant keywords (Supplementary Data). Articles published in French were searched from Elsevier Masson Consulte database using the keywords: ‘carbapenemase Afrique’. In addition, in order to retrieve articles published in journals that are not indexed in the above databases, the African Journals Online database was searched using the keywords ‘β-lactamase AND Africa’.

Non-database literature search

A search of proceedings from international conferences (European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 2012, 2013; International Conference on Prevention and Infection Control, 2013; and International Congress on Infectious Diseases, 2012), published theses and dissertations was also performed to identify relevant articles.

Study selection criteria

We included peer-reviewed articles (in English or French) reporting any data on carbapenemase-producing bacteria from African countries. The last literature search was performed on 28 February 2014. We excluded studies conducted outside African Union countries or on islands administered by European countries (British, French, Spanish and Portuguese overseas territories); and those reporting non-carbapenem-resistant isolates from Africa. In addition, reviews, editorials and studies that did not give the details of the resistance mechanism of carbapenem-resistant isolates were excluded. Furthermore, we also excluded studies that used the same carbapenemase-producing isolates from published studies for other investigations. All studies describing carbapenemase-producing bacteria isolated from humans, animals or environmental samples from Africa were included.

Data extraction and synthesis

The data extracted include: the country in which the samples were collected, year of sampling, study design, type of sample, bacterial species identified, type of carbapenemase described, setting in which sampling was conducted and age group of the participants and the references. The data were extracted by two authors (R. I. M. and M. K.) and disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus. A third author (H. J. Z. or M. P N.) was consulted where consensus could not be achieved. The study design was determined by two authors (R. I. M. and M. K.) for studies where this was not specified. In this review, children were defined as individuals of <12 years of age. We calculated the prevalence of carbapenemase producers only including studies where the total number of isolates tested was 30 or more.

Results

Literature search

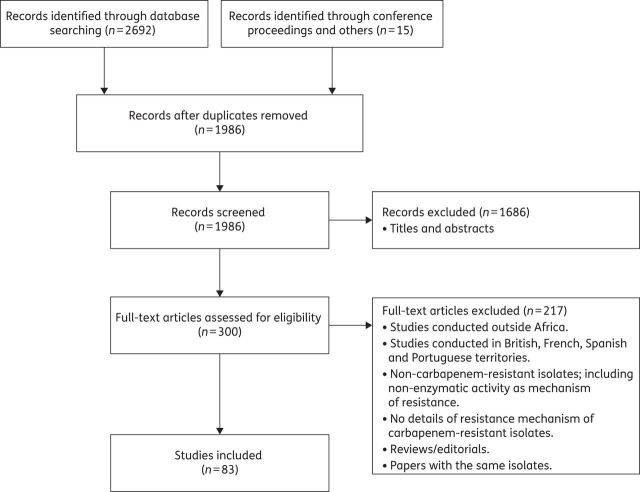

A total of 2692 articles were identified through the electronic database searches. In addition, 15 articles were identified through non-database searches (Figure 1). After duplicate removal, 1986 articles were screened based on the titles and abstracts. Of these, 1686 were excluded as not meeting the specified inclusion criteria. Finally, 300 full-text articles were reviewed, of which 83 full-text articles fulfilled the criteria for inclusion in this systematic review. The reasons for excluding full-text articles are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing selection of studies reviewed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Characteristics of studies included in this systematic review

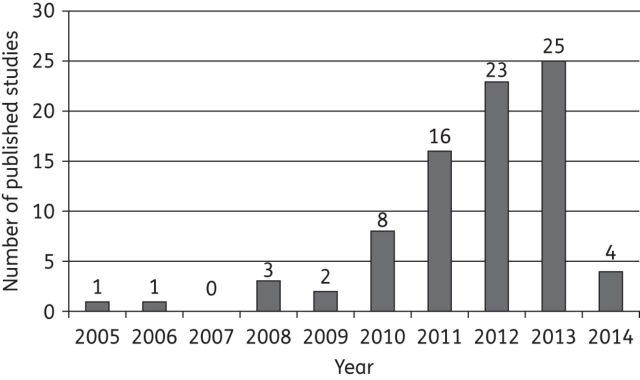

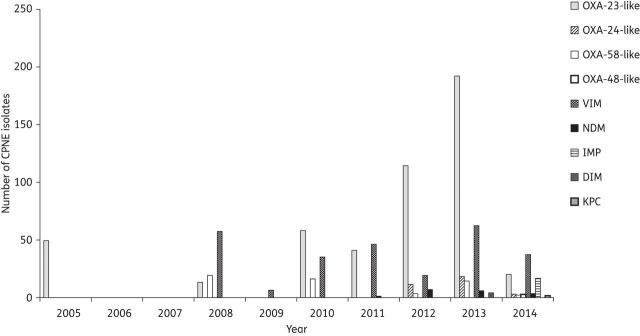

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the main characteristics of the 83 studies (from 15 countries) included in this systematic review. Most of the studies were based on laboratory-based surveillance. Prior to 2010, only seven studies reported carbapenemase-producing bacteria in Africa, but subsequently increasing numbers of studies (including outbreaks) were reported (Figure 2). Outbreaks reported in Africa involved OXA-48, OXA-58, OXA-23, VIM-2 or VIM-4 carbapenemase-producing bacteria (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Studies reporting carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Africa

| Country | Year of sampling | Type of study | Isolate source | Organisms | Number of isolates positive/total tested (%) | Carbapenemase described (number of isolates) |

Setting | Age group | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPC | OXA | VIM | NDM | Others | |||||||||

| Algeria | 2008 | case report | urinary samples |

E. coli K. pneumoniae P. stuartii |

5/5 (100) | VIM-19 (2) VIM-19 (2) VIM-19 (1) |

H | NA | 48 | ||||

| Algeria | 2011 | case report | blood cultures | K. pneumoniae | NA | OXA-48 (1) | H | Ch | 135 | ||||

| Cameroona | NA | case report | rectal swab | E. coli | NA | NDM-4 (1) | H | NA | 103 | ||||

| Egypt | 2009–10 | laboratory-based surveillance | stool, blood, pus, urine, throat swab, peritoneal fluid |

K. pneumoniae E. coli E. cloacae |

10/10 (100) | OXA-48 (1) OXA-48 (2) — |

VIM-1 (2) VIM-1 (2) VIM-1 (4) |

H | Ch & A | 46 | |||

| Egypt | 2009–10 | case report | blood culture, sputum | K. pneumoniae | NA | OXA-163 (2) | H | A | 64 | ||||

| Egypt | 2010–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | E. cloacae | 2/3 (67) | VIM-4 (2) | H | NA | 44 | ||||

| Egypt | 2011 | prospective study | urine, blood, respiratory tract specimens | K. pneumoniae | 14/45 (31.1) | KPC (14) | H | NA | 33 | ||||

| Egypt | 2009–10 | retrospective study | faecal, exudates, blood | E. coli | 3/73 (4.1) | OXA-48 (2) | VIM-1 (1) VIM-29 (1) |

H | Ch & A | 28 | |||

| Egypt | 2012 | case report | gastric fluid, blood | K. pneumoniae | NA | OXA-163 (1) | NDM-1 (1) | H | A | 57 | |||

| Kenya | 2007–09 | laboratory-based surveillance | urine, urethral pus | K. pneumoniae | 7/7 (100) | NDM-1 (7) | H | A | 58 | ||||

| Libyaa | 2011 | cross-sectional | nostrils, tonsils and perineum specimens | K. pneumoniae | NA | OXA-48 (7) | H | NA | 93 | ||||

| Libyaa | 2011 | case report | blood | K. pneumoniae | NA | OXA-48 (1) | H | A | 98 | ||||

| Libyaa | 2011 | cross-sectional | rectal swabs | K. pneumoniae | NA | OXA-48 (1) | H | NA | 99 | ||||

| Libyaa | 2011 | case series | CSF, pleural fluid, catheter, urine, endotracheal | K. pneumoniae | 6/6 (100) | OXA-48 (6) | H | NA | 105 | ||||

| Libyaa | 2011 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | K. pneumoniae | NA | OXA-48 (13) | H | A | 136 | ||||

| Morocco | 2009–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | blood, urine, bone, skin abscess, urinary tract catheter |

K. pneumoniae K. oxytoca E. cloacae |

21/21 (100) | OXA-48 (16) OXA-48 (1) OXA-48 (4) |

H | Ch & A | 95 | ||||

| Morocco | 2009–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA |

K. pneumoniae E. cloacae E. coli M. morganii |

9/17 (53) | OXA-48 (2) OXA-48 (1) OXA-48 (2) OXA-48 (1) |

IMP-1 (1) IMP-1 (2) |

C | NA | 25 | |||

| Morocco | 2010–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | E. coli | 2/47 (4) | OXA-48 (1) | IMP-1 (1) | C | Ch & A | 26 | |||

| Morocco | NA | case series | urine, blood, pancreatic abscess | K. pneumoniae | NA | NDM-1 (3) | H | A | 59 | ||||

| Morocco | NA | cross-sectional | water (puddles) | S. marcescens | NA | OXA-48 (2) | C | NA | 10 | ||||

| Morocco | 2012 | cross-sectional | rectal swabs |

K. pneumoniae E. cloacae |

10/37 (27) | OXA-48 (7) OXA-48 (3) |

H | NA | 32 | ||||

| Morocco | 2011 | cross-sectional | rectal swabs |

K. pneumoniae K. oxytoca K. terrigena E. cloacae E. coli |

24/28 (86) | OXA-48 (14) OXA-48 (1) OXA-48 (1) OXA-48 (2) OXA-48 (1) |

NDM-1 (5) | H | NA | 63 | |||

| Morocco | NA | case report | urine | K. pneumoniae | NA | OXA-48 (1) | VIM-1 (1) | NDM-1 (1) | C | A | 24 | ||

| Morocco | 2009–10 | prospective | blood, pus, urine, catheter, subcutaneous fluid collection |

K. pneumoniae K. oxytoca E. cloacae |

13/463 (2.8) | OXA-48 (6) OXA-48 (1) OXA-48 (3) |

NDM-1 (3) | H | NA | 36 | |||

| Morocco | 2009 | case report | NA | K. pneumoniae | NA | OXA-48 (1) | H | A | 69 | ||||

| Moroccoa | 2010 | case report | urine, rectal swab | E. cloacae | NA | OXA-48 (2) | H | NA | 71 | ||||

| Moroccoa | 2010 | case report | rectal swabs | K. pneumoniae | NA | OXA-48 (2) | H | NA | 137 | ||||

| Moroccoa | 2010 | case report | urine | E. coli | NA | OXA-48 (1) | H | A | 138 | ||||

| South Africa | 2011 | case report | urine, blood, tracheal aspirate, central venous catheter |

K. pneumoniae E. cloacae |

NA | KPC-2 (3) KPC-2 (1) |

NDM-1 (1) — | H | A | 41 | |||

| South Africa | 2011–12 | case series | tissue, urine, tracheal aspirate |

K. pneumoniae — S. marcescens |

NA | OXA-48 (3) OXA-181 (6) OXA-48 (1) |

H | Ch & A | 65 | ||||

| South Africa | NA | case report | sputum | E. cloacae | NA | NDM-1 (1) | H | A | 60 | ||||

| South Africa | 2010 | case report | pus | K. pneumoniae | NA | VIM-1 (1) | H | A | 47 | ||||

| South Africaa | 2012 | case report | urine | E. cloacae | NA | NDM-1 (1) | H | A | 61 | ||||

| Sierra Leone | 2010–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA |

E. cloacae E. coli K. pneumoniae Enterobacter spp. Providencia Enterobacteriaceae |

13/20 (65) | OXA-58 (4) OXA-58 (1) OXA-58 (3) OXA-58 (1) OXA-58 (1) |

VIM (3) VIM (1) VIM (4) — VIM (1) VIM (1) |

DIM-1 (3) DIM-1 (1) |

H | NA | 43 | ||

| Senegal | 2008–09 | case series | N/A |

K. pneumoniae E. coli E. cloacae Enterobacter sakazaki |

11/11 (100) | OXA-48 (8) OXA-48 (1) OXA-48 (1) OXA-48 (1) |

H | NA | 70 | ||||

| Tanzania | 2007–12 | laboratory-based surveillance | pus, urine, blood, aspirate, sputum |

K. pneumoniae E. coli K. oxytoca C. freundii M. morganii S. marcescens Salmonella spp. |

NA | KPC (3) KPC (4) |

OXA-48 (4) OXA-48 (3) OXA-48 (1) OXA-48 (1) |

VIM (11) VIM (4) — VIM (1) — VIM (2) VIM (1) |

NDM (2) NDM (2) NDM (1) — NDM (1) |

IMP (9) IMP (19) IMP (3) IMP (2) — — IMP (1) |

H | NA | 42 |

| Tunisia | 2010 | case report | urine | K. pneumoniae | NA | OXA-48 (2) | H | NA | 96 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2009–10 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | K. pneumoniae | 21/153 (14) | OXA-48 (21) | H | NA | 139 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2005 | laboratory-based surveillanceb | urine, blood, wound, catheter, cerebral abscess, sputum | K. pneumoniae | 11/11 (100) | VIM-4 (11) | H | A | 45 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2009 | case report | sputum or blood | K. pneumoniae | NA | OXA-48 (1) | H | A | 140 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2011 | laboratory-based surveillanceb | rectal, nose, axilla, environmental swabs | P. stuartii | 13/13 (100) | OXA-48 (13) | H | A | 22 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2010 | cross-sectional | environmental swabs |

E. coli K. pneumoniae |

13/46 (28) | VIM-2 (4) — | IMP-1 (9) | H | NA | 20 | |||

| Tunisia | 2012 | case report | sternal pus | K. pneumoniae | NA | NDM-1 (1) | H | A | 62 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2009–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | pus, urine, blood |

K. pneumoniae C. freundii |

NA | OXA-48 (4) OXA-48 (1) |

H | Ch & A | 94 | ||||

NA, not available; H, hospital; C, community; Ch, children; A, adult.

For the ‘Carbapenemase described’ columns, blanks mean ‘not detected’.

aTransferred or travel patient.

bIdentified outbreak.

Table 2.

Studies reporting carbapenemase-producing non-Enterobacteriaceae in Africa

| Country | Year of sampling | Type of study | Isolate source | Organisms | Number of isolates positive/total tested (%) | Carbapenemase described (number of isolates) |

Setting | Age group | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPC | OXA | VIM | NDM | Others | |||||||||

| Algeria | 2010–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | A. baumannii | 24/24 (100) | OXA-23 (23) OXA-58 (2) |

H | Ch & A | 141 | ||||

| Algeria | 2008 | laboratory-based surveillancea | rectal, urine, bronchial, environmental samples | A. baumannii | 16/16 (100) | OXA-58 (16) | H | NA | 23 | ||||

| Algeria | 2010–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | bronchial samples | A. baumannii | 14/23 (61) | OXA-23 (14) | H | Ch & A | 142 | ||||

| Algeria | NA | NA | NA | A. baumannii | NA | OXA-23 (43) OXA-24 (6) |

H | NA | 143 | ||||

| Algeria | 2004 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | A. baumannii | NA | OXA-23 (2) | H | NA | 144 | ||||

| Algeria | 2008–12 | laboratory-based surveillance | rectal swab, tracheal aspirate, urine, wound, environment |

A. baumannii — A. nosocomialis A. radioresistens |

57/113 (50) | OXA-23 (39) OXA-24 (16) OXA-23 (1) OXA-24 (1) |

NDM-1 (5) | H | NA | 21 | |||

| Algeria | 2010–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | tracheal swabs, other specimens | A. baumannii | 34/71 (48) | OXA-23 (31) OXA-72 (5) |

H | NA | 29 | ||||

| Algeria | 2010–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | blood, urine, bronchial aspirate, urinary catheter, wound | P. aeruginosa | 14/17 (82) | VIM-2 (14) | H | Ch & A | 56 | ||||

| Algeria | 2009–12 | laboratory-based surveillance | tracheal suction samples | P. aeruginosa | 2/89 (2.2) | VIM-2 (2) | H | A | 35 | ||||

| Algeriab | 2011 | case report | blood catheter, rectal swabs | A. baumannii | NA | NDM-1 (1) | H | A | 102 | ||||

| Algeriab | 2011 | case report | rectal swab | A. baumannii | NA | NDM-1 (1) | H | NA | 106 | ||||

| Côte d'Ivoire | 2009–11 | laboratory-based surveillancea | NA | P. aeruginosa | 7/12 (58) | VIM-2 (7) | H | NA | 54 | ||||

| Egypt | 2005 | laboratory-based surveillance | sputum | A. baumannii | NA | OXA-23 (1) | H | NA | 144 | ||||

| Egypt | NA | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | P. aeruginosa | 35/50 (70) | VIM-2 (35) | H | NA | 50 | ||||

| Egypt | NA | case report | catheter tip | A. baumannii | NA | OXA-58 (1) | H | NA | 145 | ||||

| Egypt | 2011–12 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | A. baumannii | 39/39 (100) | OXA-23 (39) | VIM (1) | H | NA | 30 | |||

| Egypt | 2010–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | wound, blood, catheter tip, central venous port, urine, stool, sputum, BAL, ear swab | A. baumannii | 23/34 (68) | OXA-23 (19) OXA-58 (5) OXA-40 (1) |

H | NA | 31 | ||||

| Egypt | 2012 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | A. baumannii | 25/40 (63) | OXA-23 (20) OXA-24 (3) OXA-58 (2) |

H | NA | 146 | ||||

| Egypt | 2011–12 | laboratory-based surveillance | wound, blood, urine, sputum, ear, CSF, abscess, catheter, tissue | P. aeruginosa | 31/122 (25.4) | VIM-2 (28) | NDM (2) | IMP (1) | H | NA | 147 | ||

| Egyptb | 2011 | case report | BAL, oral cavity swabs, airways | A. baumannii | NA | NDM-1 (2) | H | NA | 104 | ||||

| Egyptb | 2011 | case report | central venous line catheter | A. baumannii | NA | NDM-2 (1) | H | Ch | 148 | ||||

| Ghanab | 2006 | case report | NA | P. aeruginosa | NA | VIM-2 (1) | H | NA | 149 | ||||

| Kenya | 2006–07 | laboratory-based surveillance | urine, blood, wounds, respiratory tract specimens | P. aeruginosa | 57/57 (100) | VIM-2 (57) | H | NA | 37 | ||||

| Kenya | 2009–10 | laboratory-based surveillance | tracheal aspirate, bone marrow aspirate, CSF, catheter tip, axillary swab, nasal swab, urine, blood, and debrided tissue | A. baumannii | 16/16 (100) | OXA-23 (16) | NDM-1 (1) | H | NA | 150 | |||

| Libya | 2004 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | A. baumannii | NA | OXA-23 (1) | H | NA | 144 | ||||

| Libyab | 2011 | cross-sectional | nostrils, tonsils and perineum specimens | A. baumannii | NA | OXA-23 (3) | NDM-1 (1) | H | NA | 93 | |||

| Libyab | 2011 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | A. baumannii | NA | OXA-23 (4) | NDM-1 (2) | H | A | 136 | |||

| Madagascar | 2006–09 | laboratory-based surveillance | skin wound, urine, blood, respiratory tract secretions | A. baumannii | 53/53 (100) | OXA-23 (53) | H | NA | 40 | ||||

| Nigeria | 2012 | prospective study | NA | A. baumannii | 3/5 (60) | OXA-23 (3) | H | NA | 151 | ||||

| South Africa | 2002 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | A. baumannii | 49/49 (100) | OXA-23 (49) | H | NA | 152 | ||||

| South Africa | 2006 | laboratory-based surveillance | urine | A. baumannii | NA | OXA-23 (1) | H | NA | 144 | ||||

| South Africa | 2008 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | A. baumannii | 58/97 (59) | OXA-23 (58) OXA-58 (3) |

VIM (1) | H | NA | 39 | |||

| South Africa | 2010–11 | laboratory-based surveillancea | blood, stool, bile, urine, catheter tip | P. aeruginosa | 11/15 (73) | VIM-2 (11) | H | NA | 53 | ||||

| Sierra Leone | 2010–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA |

C. testosteroni Pseudomonas Burkholderia D. acidovorans Peudomonadaceae |

6/20 (30) | OXA-58 (1) OXA-58 (1) OXA-58 (2) OXA-58 (1) OXA-58 (1) |

— VIM (1) — — VIM (1) |

DIM-1 (1) DIM-1 (1) DIM-1 (1) — DIM-1 (1) |

H | NA | 43 | ||

| Senegal | 2008–10 | prospective | stool, head lice | A. baumannii | NA | OXA-23 (9)c | C | Ch & A | 27 | ||||

| Senegal | 2011 | case-series | blood, BAL | A. baumannii | NA | OXA-23 (3) | H | Ch & A | 153 | ||||

| Tanzania | 2010–11 | laboratory-based surveillance | pus, blood, urine | P. aeruginosa | 8/90 (8.9) | VIM (8) | H | Ch | 38 | ||||

| Tanzania | 2007–12 | laboratory-based surveillance | pus, urine, blood, aspirate |

P. aeruginosa A. baumannii |

NA | KPC (1) | OXA-48 (2) | VIM (9) | NDM (1) | IMP (12) IMP (3) |

H | NA | 42 |

| Tunisia | 2008 | laboratory-based surveillancea | urine, cutaneous pus, blood | P. aeruginosa | 16/24 (67) | VIM-2 (16) | H | A | 52 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2001–05 | laboratory-based surveillance | blood, pus | A. baumannii | 19/39 (49) | OXA-97 (19) | H | NA | 34 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2003–07 | laboratory-based surveillancea | blood, urine, catheter | P. aeruginosa | 5/75 (6.7) | VIM-2 (5) | H | A | 55 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2002–06 | laboratory-based surveillance | pus, blood, urine, catheter, bronchial secretions | P. aeruginosa | 35/73 (48) | VIM-2 (35) | H | Ch & A | 51 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2007 | laboratory-based surveillancea | blood, pus, urine, pulmonary specimens, materials | A. baumannii | 41/50 (82) | OXA-23 (41) | H | NA | 72 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2007 | case report | tracheal protection culture | A. baumannii | NA | OXA-23 (1) | H | A | 154 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2007 | laboratory-based surveillance | NA | P. aeruginosa | 30/30 (100) | VIM-2 (30) | H | NA | 155 | ||||

| Tunisia | 2005–07 | laboratory-based surveillancea | blood, pus, urine, tracheal aspirate | A. baumannii | 13/99 (13) | OXA-23 (13) | H | A | 73 | ||||

BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; Ch, children; A, adult; H, hospital; C, community; NA, not available.

For the ‘Carbapenemase described’ columns, blanks mean ‘not detected’.

aIdentified outbreak.

bTransferred or travel patient.

cThree isolates from human head lice.

Figure 2.

Number of studies reporting carbapenemase-producing bacteria in Africa per year (until February 2014).

Most of the studies reporting the identification of carbapenemase-producing bacteria were conducted in North Africa (74%, 61/83), followed by Southern Africa (12%, 10/83), especially South Africa (90%, 9/10), West Africa (8%, 7/83) and East Africa (6%, 6/83) (Tables 1 and 2).

Thirty-seven studies reported the age group of patients; 60% involved adults between the ages of 12 and 90 years old, 32% involved both adults and children and only three (8%) studies were specific to children (Tables 1 and 2). In addition, most studies (94%, 78/83) were performed in hospital settings with samples collected from hospitalized patients or the hospital environment (Tables 1 and 2). In humans, there were no reports of negative findings in studies that screened for carbapenemase producers. Carbapenemase-producing bacteria (OXA-23, OXA-24, OXA-58, VIM-2 or IMP-1) were isolated in all four studies that screened samples from hospital environments (ICU, toilet, mechanical ventilator).20–23 In this systematic review, five out of 83 (6%) studies were conducted in a community setting: four studies included samples collected mainly from non-hospitalized patients from which both class B and D carbapenemase-producing bacteria were isolated.10,24–27 One study tested environmental water samples from a Moroccan city, Marrakesh, and identified a class D (OXA-48) carbapenemase-producing Serratiamarcescens.10 In animals, only one study, conducted in Senegal, screened animal stool samples (donkeys, ducks, goats, cows, chickens, sheep, pigeons and a dog) to isolate carbapenemase-producing bacteria, but none of the samples tested positive for carbapenemases.27

Most studies (66%, 37/56) detecting carbapenemase producers followed the CLSI guidelines for susceptibility testing. Others used guidelines from the Antibiogram Committee of the French Microbiology Society (16%, 9/56), EUCAST (14%, 8/56) and BSAC (4%, 2/56). Depending on study design, the proportion of carbapenemase-producing isolates ranged from 0.2% to 100% (Tables 1 and 2). In studies included in this systematic review, the prevalence of carbapenemase-producing isolates in hospital settings ranged from 2.3% to 67.7% in North Africa,20,21,28–36 and from 9% to 60% in sub-Saharan Africa.37–40 In community settings, their prevalences were 0.2% and 5.4% in two studies conducted in Morocco.25,26

Carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae

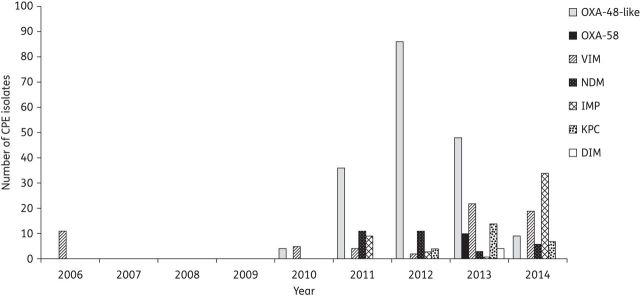

Figures 3 and 4 show the number of reported carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and their geographical distribution in Africa, respectively.

Figure 3.

Number of reported carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) isolates in Africa (until February 2014).

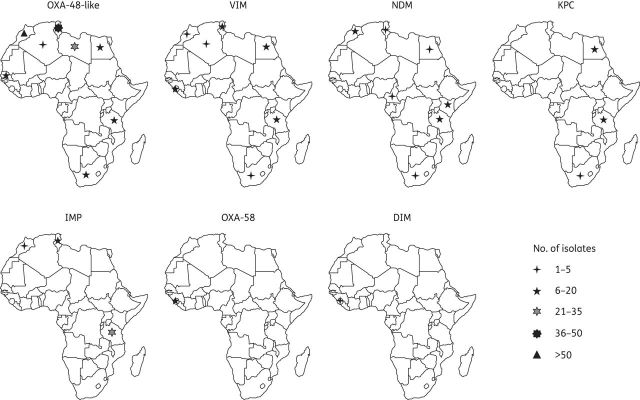

Figure 4.

Geographical distribution of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates in Africa (until February 2014).

Ambler class A carbapenemases

In Africa, Ambler class A carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae were reported in only three studies, from Egypt, Tanzania and South Africa (Table 1). In Egypt, KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains (n = 14) were recovered from patients admitted to different wards at the Suez Canal University hospital.33 The study in South Africa involved an adult patient infected with KPC-2-producing K. pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae.41 The risk factors associated with the acquisition of KPC-2 producers were treatment with multiple antibiotic agents, prolonged hospital and ICU stay, use of invasive devices and immunosuppression.41

Ambler class B carbapenemases

Four metallo-β-lactamases (NDM, VIM, IMP and DIM) were reported among Enterobacteriaceae in Africa. NDM or VIM variants were reported in at least one country from each African region (Figure 4). IMP was only identified in Morocco, Tunisia and Tanzania,20,25,26,42 whilst DIM-1 was found only in Sierra Leone.43

Most of the VIM-producing Enterobacteriaceae were recovered from adult patients hospitalized in ICUs or surgery wards.24,28,44–47 In addition, VIM-4-producing K. pneumoniae isolates (n = 11) were the cause of an outbreak in a Tunisian university hospital45 (Table 1). Moreover, three studies showed an association of VIM-4 or VIM-19 enzymes with class 1 integrons.44,45,48 VIM-1, VIM-4 and VIM-19 were identified in resistant Enterobacteriaceae (mainly K. pneumoniae, Escherichia coli and E. cloacae).24,44–46,48,49 With the exception of a single report, from Tunisia, of VIM-2-producing E. coli isolates,20 reports of VIM-2 enzymes were restricted to Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates.37,50–56

With the exception of one K. pneumoniae strain recovered from the urine of a non-hospitalized patient, NDM-producing Enterobacteriaceae (mainly K. pneumoniae) were identified in hospital settings, mostly among adult patients hospitalized in ICUs or medical or surgical wards.24,41,57–62 NDM-producing Enterobacteriaceae were mostly isolated from rectal swabs, urine, catheter tips or pus.24,36,41,58,59,62,63 NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae were mainly K. pneumoniae isolates (Table 1). One K. pneumoniae isolate from a urine sample of a non-hospitalized (elderly male) patient from Taza, Morocco, was found to harbour OXA-48, VIM-1 and NDM-1 enzymes.24 NDM-1 was also identified in E. cloacae isolates in South Africa;60,61 one such isolate was cultured from the urine sample of a patient who had been hospitalized in India before travelling to South Africa.61 In Africa, NDM-1 was first identified in Kenya among seven clonally related K. pneumoniae isolates from urine or urethral pus of seven adult patients hospitalized in different wards (four in a medical ward, two in ICU and one in a maternity ward) at the Aga Khan University Hospital between 2007 and 2009.58

Only three studies reported the detection of IMP-1 in Africa: two from Morocco and one from Tunisia. In Tunisia, IMP-1-producing K. pneumoniae isolates (n = 9) were isolated from swabs taken from the hospital environmental (ICU and toilet).20 In Morocco, four IMP-1 carbapenemase producers (one uropathogenic E. coli, one K. pneumoniae and two E. cloacae) were isolated from community-acquired urinary tract infections.25,26 Three of these four isolates (one K. pneumoniae and two E. cloacae) were from Casablanca.25 The origin of the IMP-1-producing uropathogenic E. coli isolate was not mentioned.26

Ambler class D carbapenemases

OXA-48-like producing Enterobacteriaceae were isolated from both hospital and community settings (Table 1). Most of the OXA-48-like producers were isolated from pus, wounds, rectal swabs, blood or urine samples collected from adults or children hospitalized in surgical wards or ICUs.24,32,36,57,62–65 Several reports indicated that OXA-48-producing Enterobacteriaceae are endemic in North African countries, such as in Morocco and Tunisia.2,66–71 OXA-48-producing Providencia stuartii isolates were reported as the cause of an outbreak in a Tunisian hospital.22 OXA-181, a point mutant analogue of OXA-48, was reported in South Africa from K. pneumoniae isolates recovered in tracheal aspirate and urine samples of hospitalized adult patients.65 In addition to OXA-181, OXA-163, an OXA-48 variant that has an increased activity against extended spectrum β-lactams was identified among K. pneumoniae strains in Egypt.57,64 Of note, the OXA-51-like and OXA-58 carbapenemases which are known to be Acinetobacter-related, were identified among Enterobacteriaceae species in a study conducted in Sierra Leone43 (Table 1).

Carbapenemases among non-Enterobacteriaceae

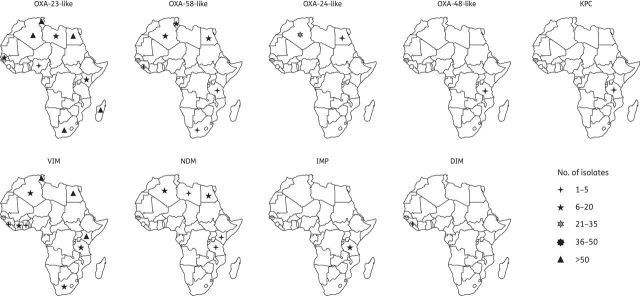

Figures 5 and 6 show the number of reported carbapenemase-producing non-Enterobacteriaceae isolates and their geographical distribution in Africa, respectively.

Figure 5.

Number of reported carbapenemase-producing non-Enterobacteriaceae (CPNE) isolates in Africa (until February 2014).

Figure 6.

Geographical distribution of carbapenemase-producing non-Enterobacteriaceae isolates in Africa (until February 2014).

Ambler class A carbapenemases

Class A carbapenemases were only reported in Tanzania. The KPC enzyme, known to be prevalent among Enterobacteriaceae, was identified in a P. aeruginosa isolate from a clinical specimen from a tertiary hospital in northwestern, Tanzania.42

Ambler class B carbapenemases

A variety of metallo-β-lactamases were reported among non-Enterobacteriaceae isolates (Figure 6). VIM-2 and NDM variants (NDM-1 and NDM-2) were reported among P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii, respectively. VIM-2-producing P. aeruginosa were involved in outbreaks in Tunisia, Côte d'Ivoire and South Africa,52–55 (Table 2). Four studies showed an association of VIM-2 enzyme with class 1 integrons that also contained gene cassettes that render isolates resistant to different classes of antimicrobial agents.51,54–56 NDM-producing A. baumannii isolates were identified in patients from North and East Africa, with no obvious link with the Indian subcontinent (Figure 6 and Table 2).

Ambler class D carbapenemases

Carbapenem-hydrolysing class D β-lactamases were identified in many African countries (Figure 6). The OXA-23-like carbapenemase subgroup was mainly reported in A. baumannii strains from North Africa (Figure 6). OXA-23-producing A. baumannii strains were reported as the cause of an outbreak in Tunisian hospitals.72,73 OXA-24-like enzymes were reported in Algeria and Egypt, among resistant A. baumannii isolates (Figure 6). OXA-58-like enzymes were less common and, like OXA-23 and OXA-24, they were more consistently associated with resistant Acinetobacter species (Table 2). Interestingly, the OXA-48 enzyme, which is widespread among Enterobacteriaceae, was identified in two P. aeruginosa clinical isolates in Tanzania.42

Discussion

The burden of antibiotic resistance is a public health concern and may contribute to increased mortality, prolonged hospital stay and increased costs of healthcare, especially in developing countries.74–78 In Africa, data on antibiotic resistance are very limited.79 Lack of systematically collected data on the African continent contributes to a poor understanding of antimicrobial resistance and limits an effective response to the problem.79

Carbapenemase-producing bacteria, particularly KPC, VIM, IMP, NDM and OXA types, are increasingly reported worldwide; however, most reports are from Europe, North America and Asia.2,11,80 The KPC enzyme was first identified from a K. pneumoniae isolate in the USA in 1996.12 Since then, KPC-producing bacteria have spread worldwide, including Africa.81–85 VIM-producing isolates are endemic in Greece;86,87 however, outbreaks as well as isolated cases have been reported throughout the world.2,13,52,88,89 IMP producers, which are endemic in Japan and Taiwan, were reported worldwide.84,87,90 NDM enzymes are mostly described in Enterobacteriaceae, especially E. coli and K. pneumoniae, and they are widespread in India and Pakistan but are increasingly reported worldwide.13,16,58,91,92 Class D, OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae are widespread in Turkey, the Middle East and North Africa.2,66–71

This systematic review showed that there is a rapid increase in the number of reports of carbapenemase-producing bacteria in Africa. Class D carbapenemases (especially OXA-48) are the most reported enzymes among Enterobacteriaceae in Africa, particularly in North African countries. This enzyme was described in various Enterobacteriaceae, including K. pneumoniae, E. coli, E. cloacae, P. stuartii and Citrobacter freundii isolates from North African countries.22,32,46,63,93,94 Data from these countries show that OXA-48-producing isolates are not from a single clone.25,95,96 A study conducted by Poirel et al.71 also showed differing pulsotypes (diverse clones) among four OXA-48-producing E. cloacae isolates, two from patients transferred from Morocco to France, and two from Turkey.67,71 However, a common OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae clone circulating in North African countries is also found in several European countries, especially in Turkey, France and the Netherlands.2,9,13,25,95–97 There are cases of OXA-48-producing K. pneumoniae imported from Libya to Italy, Slovenia and Denmark, indicating that North Africa harbours OXA-48-producing Enterobacteriaceae.93,98,99 OXA-23 (also known as ARI-1) was first identified in 1985 from an A. baumannii strain from a patient in Edinburgh, UK.100,101 The relatedness of strains circulating in Africa is not clear; however, many strains of OXA-23-producing A. baumannii from Madagascar and Tunisia were reported to be of the same clone.40,73

This systematic review also indicates that metallo-β-lactamases are present in each African region. As in other parts of the world, the emergence, among Enterobacteriaceae, of NDM enzymes that are able to hydrolyse almost all β-lactam antibiotics is of great concern.17,24,41,62,102,103 In addition to Enterobacteriaceae, NDM has been identified among A. baumannii isolates from North African countries, especially Algeria, Egypt and Libya.21,93,102,104,105 There are also several reports of imported cases identified in Europe, in patients from North Africa with no obvious link to the Indian subcontinent.102,104,106

Several risk factors are associated with the acquisition of carbapenemase-producing bacteria in healthcare settings, such as recent antibiotic therapy, prolonged hospital stay, use of invasive devices and immunosuppression.7,107–109 These risk factors were reported in a South African study.41 In the community, risk factors are still uncertain; however, overuse and over-the-counter use of antibiotics, inadequate hygiene and global travel may enhance the spread of carbapenemase-producing bacteria.2,79,110,111 Selection for such bacteria is not only associated with recent or prior carbapenem therapy but also with use of other antibiotics (such as aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones),81,112 as indicated by the detection of carbapenem-resistant (OXA-23) A. baumannii in Madagascar, where carbapenems were unavailable during the study period.40 The uncontained spread of carbapenemase-producing bacteria may occur in Africa for several reasons. Firstly, there is substantial over-the-counter use of antibiotics in many African countries (reaching 40% in Nigeria and Uganda) with limited attention to antimicrobial stewardship.79,110,111,113,114 Of concern is an increase in over-the-counter use of carbapenems in Africa, especially in Egypt.78 Egypt is among the three countries (the other two being India and Pakistan) in the world where retail sales of carbapenems have drastically increased according to the report by The Lancet Infectious Diseases Commission.78 This might be explained by, in addition to the quasi-absence of regulations governing antibiotic use, the availability of low-cost generic or counterfeit and low-quality carbapenems. Secondly, due to resource constraints, infection-control practices are often suboptimal, with limited opportunity for patient isolation or screening of high-risk individuals.115 Finally, in the context of other pressing, more visible healthcare priorities, there may be limited political will or attention to the emerging problem of antimicrobial resistance.116,117

The occurrence, in Morocco, of OXA-48-producing S. marcescens isolates in environmental water is also of concern since such organisms can be spread through unsafe water and poor sanitation.10 Carbapenemase-producing organisms have also been isolated from environmental water samples in Asia118–121 and Europe.122,123 Although no carbapenemase-producing bacteria were identified in a single study conducted in animal reservoirs in Africa,27 there is a need for further studies. Of note, carbapenemase-producing bacteria have been found in animals (cattle, dogs, pigs and horses) in Western Europe.124–128 Therefore, active surveillance is needed for the detection of bacteria resistant to carbapenems in the food chain as well as in livestock.

Detection of carbapenemase-producing bacteria is not straightforward, since there is no screening medium that is able to detect all types of carbapenemases,129 and some carbapenemase producers demonstrate intermediate resistance or susceptibility to carbapenems on routine testing.2 Most studies reviewed here used routine antibiotic susceptibility testing (either disc diffusion or automated systems) to screen for carbapenemase-producing bacteria.30,52,55,56,66,130 Of note, automated systems are unreliable in detecting all types of carbapenemase-producing isolates.131

Limitations of this systematic review include the inability to determine the true prevalence of carbapenemase-producing bacteria as most studies were case reports or laboratory-based surveillance. In addition, there are few published data on carbapenemase-producing organisms from sub-Saharan Africa. There is also a lack of reports of negative findings in studies that screened for carbapenemase producers in humans; however, this may have been influenced by publication bias, with studies not detecting carbapenemase producers less likely to be reported. Many studies also had incomplete data regarding risk factors for the acquisition of carbapenemase-producing bacteria. In most studies there was no clear distinction between community-associated or hospital-associated infections.

Conclusions

Whilst data from Africa are still limited, this systematic review provides evidence that carbapenemase-producing bacteria occur widely in Africa. Infections due to MDRGN organisms are likely to cause a substantial burden of disease in Africa, and yet research into this area is not prioritized by grant funding organizations.132 For example, neonatal infections were estimated to be responsible for more than 800 000 deaths in 2010, and yet the proportion of these caused by MDRGN organisms is unknown.77 Therefore, to inform future policy decisions and guide appropriate antimicrobial therapy in Africa, data on antibiotic resistance should be systematically collected and appropriate screening methods used to identify carbapenemase-producing bacteria in Africa. These data should be supplemented by molecular detection and genotyping of resistant isolates and characterization of existing and novel carbapenemase genes.133 NDM enzymes were already prevalent in India at the time when this enzyme was first detected.134 Similarly, without strong surveillance systems in Africa, it is likely that the detection of emerging antimicrobial resistance will occur too late to prevent the widespread dissemination of resistant bacteria.

Funding

This work was supported by a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Global Health Grant (OPP107641) and the National Research Foundation, South Africa. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. R. I. M. is supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa and the Drakenstein Child Health Study, Cape Town, South Africa. M. K. is supported by the Wellcome Trust, UK.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

The corresponding author had full access to all of the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the article for publication. All of the authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript prior to submission for publication.

Author contributions

M. K., H. J. Z. and M. P. N. initiated the project, and R. I. M. extracted the data and reviewed the article with M. K. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

M. K. was a recipient of a Carnegie Corporation of New York (USA) fellowship.

References

- 1.Xu Z-Q, Flavin MT, Flavin J. Combating multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2014;23:163–82. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2014.848853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L. Global spread of Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1791–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohlenberg A, Weitzel-Kage D, van der Linden P, et al. Outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a surgical intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect. 2010;74:350–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cezário RC, Duarte De Morais L, Ferreira JC, et al. Nosocomial outbreak by imipenem-resistant metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in an adult intensive care unit in a Brazilian teaching hospital. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2009;27:269–74. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borer A, Saidel-Odes L, Riesenberg K, et al. Attributable mortality rate for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:972–6. doi: 10.1086/605922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daikos GL, Petrikkos P, Psichogiou M, et al. Prospective observational study of the impact of VIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase on the outcome of patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1868–73. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00782-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel G, Huprikar S, Factor SH, et al. Outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection and the impact of antimicrobial and adjunctive therapies. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:1099–106. doi: 10.1086/592412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwaber MJ, Klarfeld-Lidji S, Navon-Venezia S, et al. Predictors of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae acquisition among hospitalized adults and effect of acquisition on mortality. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1028–33. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01020-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potron A, Kalpoe J, Poirel L, et al. European dissemination of a single OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae clone. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:e24–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potron A, Poirel L, Bussy F, et al. Occurrence of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase gene blaOXA-48 in the environment in Morocco. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5413–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05120-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Queenan AM, Bush K. Carbapenemases: the versatile β-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:440–58. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yigit H, Queenan AM, Anderson GJ, et al. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1151–61. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1151-1161.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantón R, Akóva M, Carmeli Y, et al. Rapid evolution and spread of carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:413–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ) Scientific opinion on carbapenem resistance in food animal ecosystems. EFSA J. 2013;11:3501. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, et al. Characterization of a new metallo-β-lactamase gene, blaNDM-1, and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:5046–54. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00774-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordmann P, Poirel L, Toleman MA, et al. Does broad-spectrum β-lactam resistance due to NDM-1 herald the end of the antibiotic era for treatment of infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:689–92. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:597–602. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turton JF, Ward ME, Woodford N, et al. The role of ISAba1 in expression of OXA carbapenemase genes in Acinetobacter baumannii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;258:72–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lascols C, Peirano G, Hackel M, et al. Surveillance and molecular epidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates that produce carbapenemases: first report of OXA-48-like enzymes in North America. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:130–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01686-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chouchani C, Marrakchi R, Ferchichi L, et al. VIM and IMP metallo-β-lactamases and other extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from environmental samples in a Tunisian hospital. APMIS. 2011;119:725–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2011.02793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mesli E, Berrazeg M, Drissi M, et al. Prevalence of carbapenemase-encoding genes including New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase in Acinetobacter species, Algeria. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e739–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mnif B, Ktari S, Chaari A, et al. Nosocomial dissemination of Providencia stuartii isolates carrying blaOXA-48, blaPER-1, blaCMY-4 and qnrA6 in a Tunisian hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:329–32. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drissi M, Poirel L, Mugnier PD, et al. Carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii, Algeria. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:1457–8. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barguigua A, El Otmani F, Lakbakbi El Yaagoubi F, et al. First report of a Klebsiella pneumoniae strain coproducing NDM-1, VIM-1 and OXA-48 carbapenemases isolated in Morocco. APMIS. 2012;121:675–7. doi: 10.1111/apm.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barguigua A, El Otmani F, Talmi M, et al. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates in the Moroccan community. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;73:290–1. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barguigua A, El Otmani F, Talmi M, et al. Prevalence and types of extended spectrum β-lactamases among urinary Escherichia coli isolates in Moroccan community. Microb Pathog. 2013;61–62:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kempf M, Rolain J-M, Diatta G, et al. Carbapenem resistance and Acinetobacter baumannii in Senegal: the paradigm of a common phenomenon in natural reservoirs. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 28.Abdelaziz MO, Bonura C, Aleo A, et al. Cephalosporin resistant Escherichia coli from cancer patients in Cairo, Egypt. Microbiol Immunol. 2013;57:391–5. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bakour S, Kempf M, Touati A, et al. Carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in two university hospitals in Algeria. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1341–3. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.045807-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fouad M, Attia AS, Tawakkol WM, et al. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii harboring the OXA-23 carbapenemase in intensive care units of Egyptian hospitals. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e1252–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Hassan L, El Mehallawy H, Amyes SGB. Diversity in Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from paediatric cancer patients in Egypt. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:1082–8. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Girlich D, Bouihat N, Poirel L, et al. High rate of fecal carriage of ESBL and OXA-48 carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae at a University hospital in Morocco. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:350–4. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metwally L, Gomaa N, Attallah M, et al. High prevalence of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-mediated resistance in K. pneumoniae isolates from Egypt. East Mediterr Heal J. 2013;19:947–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poirel L, Mansour W, Bouallegue O, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from Tunisia producing the OXA-58-like carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase OXA-97. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1613–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00978-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sefraoui I, Berrazeg M, Drissi M, et al. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strains isolated from western Algeria between 2009 and 2012. Microb Drug Resist. 2013;20:156–61. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wartiti MA, Bahmani FZ, Elouennass M, et al. Prevalence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a university hospital in Rabat, Morocco: a 19-months prospective study. Int Arab J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pitout JDD, Revathi G, Chow BL, et al. Metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from a large tertiary centre in Kenya. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:755–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moyo S, Haldorsen B, Aboud S, et al. First report of metallo-β-lactamase producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Tanzania. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:469. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kock MM, Bellomo AN, Storm N, et al. Prevalence of carbapenem resistance genes in Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from clinical specimens obtained from an academic hospital in South Africa. South African J Epidemiol Infect. 2013;28:28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andriamanantena TS, Ratsima E, Rakotonirina HC, et al. Dissemination of multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in various hospitals of Antananarivo Madagascar. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2010;9:17. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brink AJ, Coetzee J, Clay CG, et al. Emergence of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM-1) and Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC-2) in South Africa. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:525–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05956-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mushi MF, Mshana SE, Imirzalioglu C, et al. Carbapenemase genes among multidrug resistant Gram negative clinical isolates from a tertiary hospital in Mwanza, Tanzania. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:303104. doi: 10.1155/2014/303104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leski TA, Bangura U, Jimmy DH, et al. Identification of blaOXA-51-like, blaOXA-58, blaDIM-1, and blaVIM carbapenemase genes in hospital Enterobacteriaceae isolates from Sierra Leone. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:2435–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00832-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dimude JU, Amyes SGB. Molecular characterisation and diversity in Enterobacter cloacae from Edinburgh and Egypt carrying blaCTX-M-14 and blaVIM-4 β-lactamase genes. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;41:574–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ktari S, Arlet G, Mnif B, et al. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates producing VIM-4 metallo-β-lactamase, CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum β-lactamase, and CMY-4 AmpC β-lactamase in a Tunisian university hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:4198–201. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00663-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poirel L, Abdelaziz MO, Bernabeu S, et al. Occurrence of OXA-48 and VIM-1 carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Egypt. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;41:90–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peirano G, Moolman J, Pitondo-Silva A, et al. The characteristics of VIM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from South Africa. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44:74–8. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2011.614276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robin F, Aggoune-Khinache N, Delmas J, et al. Novel VIM metallo-β-lactamase variant from clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae from Algeria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:466–70. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00017-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moolman J, Pitout J. Pathogens chipping away at our last line of defence—the rise of the metallo-β-lactamases. South African Med J. 2011;102:27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diab M, Fam N, EL-Said M, et al. The occurrence of VIM-2 metallo-ß-lactamases in imipenem-resistant and -susceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from Egypt; Berlin, 2013. Basel, Switzerland: European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases; p. p. 124. Abstracts of the Twenty-third European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Abstract P1342. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hammami S, Gautier V, Ghozzi R, et al. Diversity in VIM-2-encoding class 1 integrons and occasional blaSHV2a carriage in isolates of a persistent, multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clone from Tunis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:189–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hammami S, Boutiba-Ben Boubaker I, Ghozzi R, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing VIM-2 metallo-β-lactamase in a kidney transplantation unit. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:106. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-6-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacobson RK, Minenza N, Nicol M, et al. VIM-2 metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa causing an outbreak in South Africa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1797–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jeannot K, Guessennd N, Fournier D, et al. Outbreak of metallo-β-lactamase VIM-2-positive strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the Ivory Coast. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:2952–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mansour W, Poirel L, Bettaieb D, et al. Metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in Tunisia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;64:458–61. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Touati M, Diene SM, Dekhil M, et al. Dissemination of a class I integron carrying VIM-2 carbapenemase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from a hospital intensive care unit in Annaba, Algeria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2426–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00032-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abdelaziz MO, Bonura C, Aleo A, et al. NDM-1- and OXA-163-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Cairo, Egypt, 2012. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2013;1:213–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poirel L, Revathi G, Bernabeu S, et al. Detection of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Kenya. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:934–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01247-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poirel L, Benouda A, Hays C, et al. Emergence of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Morocco. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2781–3. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lowman W, Sriruttan C, Nana T, et al. NDM-1 has arrived: first report of a carbapenem resistance mechanism in South Africa. South African Med J. 2011;101:873–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Govind CN, Moodley K, Peer AK, et al. NDM-1 imported from India—first reported case in South Africa. South African Med J. 2013;103:476–8. doi: 10.7196/samj.6593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ben Nasr A, Decré D, Compain F, et al. Emergence of NDM-1 in association with OXA-48 in Klebsiella pneumoniae from Tunisia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:4089–90. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00536-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zerouali K, Barguiga A, Timinouni M, et al. Prevalence and characterisation of carbapenemase producing Enterobacteriaceae in a university hospital centre, Casablanca, Morocco. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:468. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abdelaziz MO, Bonura C, Aleo A, et al. OXA-163-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Cairo, Egypt, in 2009 and 2010. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2489–91. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06710-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brink AJ, Coetzee J, Corcoran C, et al. Emergence of OXA-48 and OXA-181 carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in South Africa and evidence of in vivo selection of colistin resistance as a consequence of selective decontamination of the gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:369–72. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02234-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Poirel L, Heritier C, Tolun V, et al. Emergence of oxacillinase-mediated resistance to imipenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;48:15–22. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.1.15-22.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carrër A, Poirel L, Yilmaz M, et al. Spread of OXA-48-encoding plasmid in Turkey and beyond. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1369–73. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01312-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cuzon G, Ouanich J, Gondret R, et al. Outbreak of OXA-48-positive carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2420–3. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01452-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Benouda A, Touzani O, Khairallah M-T, et al. First detection of oxacillinase-mediated resistance to carbapenems in Klebsiella pneumoniae from Morocco. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2010;104:327–30. doi: 10.1179/136485910X12743554760108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moquet O, Bouchiat C, Kinana A, et al. Class D OXA-48 carbapenemase in multidrug-resistant enterobacteria, Senegal. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:143–4. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.100224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Poirel L, Ros A, Carrër A, et al. Cross-border transmission of OXA-48-producing Enterobacter cloacae from Morocco to France. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1181–2. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hammami S, Ghozzi R, Saidani M, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii producing the carbapenemase OXA-23 in Tunisia. Tunis Med. 2011;89:638–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mansour W, Poirel L, Bettaieb D, et al. Dissemination of OXA-23-producing and carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a University Hospital in Tunisia. Microb Drug Resist. 2008;14:289–92. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2008.0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zaidi AKM, Huskins WC, Thaver D, et al. Hospital-acquired neonatal infections in developing countries. Lancet. 2005;365:1175–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71881-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thaver D, Ali SA, Zaidi AKM. Antimicrobial resistance among neonatal pathogens in developing countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(Suppl 1):S19–21. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181958780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Laxminarayan R, Heymann D. Challenges of drug resistance in the developing world. 2012;1567:3–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012;379:2151–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, et al. Antibiotic resistance—the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:1057–98. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Okeke IN, Laxminarayan R, Bhutta ZA, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in developing countries. Part I: recent trends and current status. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:481–93. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grundmann H, Livermore DM, Giske CG, et al. Carbapenem-non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae in Europe: conclusions from a meeting of national experts. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:pii=19711. doi: 10.2807/ese.15.46.19711-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nordmann P, Cuzon G, Naas T. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:228–36. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Leavitt A, Navon-Venezia S, Chmelnitsky I, et al. Emergence of KPC-2 and KPC-3 in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in an Israeli hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3026–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00299-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maltezou HC, Giakkoupi P, Maragos A, et al. Outbreak of infections due to KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a hospital in Crete (Greece) J Infect. 2009;58:213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Navon-Venezia S, Leavitt A, Schwaber MJ, et al. First report on a hyperepidemic clone of KPC-3-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Israel genetically related to a strain causing outbreaks in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:818–20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00987-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Samra Z, Ofir O, Lishtzinsky Y, et al. Outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC-3 in a tertiary medical centre in Israel. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;30:525–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ikonomidis A, Tokatlidou D, Kristo I, et al. Outbreaks in distinct regions due to a single Klebsiella pneumoniae clone carrying a blaVIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5344–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.10.5344-5347.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vatopoulos A. High rates of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greece—a review of the current evidence. Euro Surveill. 2008;13:pii=8023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lauretti L, Riccio ML, Mazzariol A, et al. Cloning and characterization of blaVIM, a new integron-borne metallo-β-lactamase gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1584–90. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Giani T, Marchese A, Coppo E, et al. VIM-1-producing Pseudomonas mosselii isolates in Italy, predating known VIM-producing index strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2216–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06005-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Walsh TR, Toleman MA, Poirel L, et al. Metallo-β-lactamases: the quiet before the storm? Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:306–25. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.306-325.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Decousser J, Jansen C, Nordmann P, et al. Outbreak of NDM-1-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in France, January to May 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:pii=20547. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.31.20547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Espinal P, Fugazza G, López Y, et al. Dissemination of an NDM-2-producing Acinetobacter baumannii clone in an Israeli rehabilitation center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5396–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00679-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hammerum AM, Larsen AR, Hansen F, et al. Patients transferred from Libya to Denmark carried OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, NDM-1-producing Acinetobacter baumannii and meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:191–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Saïdani M, Hammami S, Kammoun A, et al. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant OXA-48 carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Tunisia. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1746–9. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.045229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hays C, Benouda A, Poirel L, et al. Nosocomial occurrence of OXA-48-producing enterobacterial isolates in a Moroccan hospital. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39:545–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lahlaoui H, Poirel L, Barguellil F, et al. Carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamase OXA-48 in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Tunisia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:937–9. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1389-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pitart C, Solé M, Roca I, et al. First outbreak of a plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing OXA-48 β-lactamase in Klebsiella pneumoniae in Spain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4398–401. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00329-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kocsis E, Savio C, Piccoli M, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae harbouring OXA-48 carbapenemase in a Libyan refugee in Italy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:E409–11. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pirš M, Andlovic A, Cerar T, et al. A case of OXA-48 carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a patient transferred to Slovenia from Libya, November 2011. Euro Surveill. 2011;16:pii=20042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Donald HM, Scaife W, Amyes SG, et al. Sequence analysis of ARI-1, a novel OXA β-lactamase, responsible for imipenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii 6B92. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:196–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.1.196-199.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Paton R, Miles RS, Hood J, et al. ARI 1: β-lactamase-mediated imipenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1993;2:81–7. doi: 10.1016/0924-8579(93)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Boulanger A, Naas T, Fortineau N, et al. NDM-1-producing Acinetobacter baumannii from Algeria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2214–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05653-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dortet L, Poirel L, Anguel N, et al. New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase 4-producing Escherichia coli in Cameroon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1540–2. doi: 10.3201/eid1809.120011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hrabák J, Stolbová M, Studentová V, et al. NDM-1 producing Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from a patient repatriated to the Czech Republic from Egypt, July 2011. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:pii=20085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lafeuille E, Decré D, Mahjoub-Messai F, et al. OXA-48 Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from Libyan patients. Microb Drug Resist. 2013;19:491–7. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2012.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bogaerts P, Rezende de Castro R, Roisin S, et al. Emergence of NDM-1-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in Belgium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1552–3. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gregory CJ, Llata E, Stine N, et al. Outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Puerto Rico associated with a novel carbapenemase variant. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:476–84. doi: 10.1086/651670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hussein K, Sprecher H, Mashiach T, et al. Carbapenem resistance among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates: risk factors, molecular characteristics, and susceptibility patterns. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:666–71. doi: 10.1086/598244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jeon M-H, Choi S-H, Kwak YG, et al. Risk factors for the acquisition of carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli among hospitalized patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62:402–6. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mukonzo JK, Namuwenge PM, Okure G, et al. Over-the-counter suboptimal dispensing of antibiotics in Uganda. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:303–10. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S49075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Morgan DJ, Okeke IN, Laxminarayan R, et al. Non-prescription antimicrobial use worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:692–701. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70054-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kritsotakis EI, Tsioutis C, Roumbelaki M, et al. Antibiotic use and the risk of carbapenem-resistant extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in hospitalized patients: results of a double case–control study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1383–91. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sabry NA, Farid SF, Dawoud DM. Antibiotic dispensing in Egyptian community pharmacies: an observational study. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2013;10:168–84. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Esimone CO, Nworu CS, Udeogaranya OP. Utilization of antimicrobial agents with and without prescription by out-patients in selected pharmacies in South-eastern Nigeria. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29:655–60. doi: 10.1007/s11096-007-9124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Campbell H, Duke T, Weber M, et al. Global initiatives for improving hospital care for children: state of the art and future prospects. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e984–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Larson E. Community factors in the development of antibiotic resistance. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:435–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Harbarth S, Samore MH. Antimicrobial resistance determinants and future control. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:794–801. doi: 10.3201/eid1106.050167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Isozumi R, Yoshimatsu K, Yamashiro T, et al. bla NDM-1-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae from environment, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1383–5. doi: 10.3201/eid1808.111816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Khan AU, Nordmann P. Spread of carbapenemase NDM-1 producers: the situation in India and what may be proposed. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44:531–5. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2012.669046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Walsh TR, Weeks J, Livermore DM, et al. Dissemination of NDM-1 positive bacteria in the New Delhi environment and its implications for human health: an environmental point prevalence study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:355–62. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhang C, Qiu S, Wang Y, et al. Higher isolation of NDM-1 producing Acinetobacter baumannii from the sewage of the hospitals in Beijing. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zurfluh K, Hächler H, Nüesch-Inderbinen M, et al. Characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates from rivers and lakes in Switzerland. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:3021–6. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00054-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Galler H, Feierl G, Petternel C, et al. KPC-2 and OXA-48 carbapenemase-harbouring Enterobacteriaceae detected in an Austrian wastewater treatment plant. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O132–4. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Fischer J, Rodríguez I, Schmoger S, et al. Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica producing VIM-1 carbapenemase isolated from livestock farms. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:478–80. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Poirel L, Berçot B, Millemann Y, et al. Carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter spp. in cattle, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:523–5. doi: 10.3201/eid1803.111330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Fischer J, Rodríguez I, Schmoger S, et al. Escherichia coli producing VIM-1 carbapenemase isolated on a pig farm. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1793–5. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Smet A, Boyen F, Pasmans F, et al. OXA-23-producing Acinetobacter species from horses: a public health hazard? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:3009–10. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Stolle I, Prenger-Berninghoff E, Stamm I, et al. Emergence of OXA-48 carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in dogs. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:2802–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Carrër A, Fortineau N, Nordmann P. Use of ChromID extended-spectrum β-lactamase medium for detecting carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1913–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02277-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twenty-second Informational Supplement M100-S22. Wayne, PA, USA: CLSI; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Woodford N, Eastaway AT, Ford M, et al. Comparison of BD Phoenix, Vitek 2, and MicroScan automated systems for detection and inference of mechanisms responsible for carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2999–3002. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00341-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Head MG, Fitchett JR, Cooke MK, et al. Systematic analysis of funding awarded for antimicrobial resistance research to institutions in the UK, 1997–2010. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:548–54. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Opazo A, Domínguez M, Bello H, et al. Review article: OXA-type carbapenemases in Acinetobacter baumannii in South America. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6:311–6. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Castanheira M, Deshpande LM, Mathai D, et al. Early dissemination of NDM-1- and OXA-181-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Indian hospitals: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 2006–2007. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1274–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01497-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Aggoune-Khinache N, Assaous F, Maamar HT, et al. Emergence of carbapenem-hydrolyzing OXA-48 β-lactamase in an Algerian hospital; Berlin, 2013. Basel, Switzerland: European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases; p. p. 13. Abstracts of the Twenty-third European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Abstract R2638. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kaase M, Pfennigwerth N, Szabados F, et al. OXA-48, OXA-23 and NDM-1 carbapenemases in Gram-negative bacteria from patients from Libya. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:475. [Google Scholar]