Abstract

Methyl isocyanate has been recently detected in comet 67P/ Churyumov-Gerasimenko (67P/CG) and in the interstellar medium. New physicochemical studies on this species are now necessary as tools for subsequent studies in astrophysics. In this work, infrared spectra of solid CH3NCO have been obtained at temperatures of relevance for astronomical environments. The spectra are dominated by a strong, characteristic multiplet feature at 2350-2250 cm-1, which can be attributed to the antisymmetric stretching of the NCO group. A phase transition from amorphous to crystalline methyl isocyanate is observed at ~ 90 K. The band strengths for the absorptions of CH3NCO in ice at 20 K have been measured. Deuterated methyl isocyanate is used to help with the spectral assignment. No X-ray structure has been reported for crystalline CH3NCO. Here we advance a tentative theoretical structure, based on Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, derived taking as a starting point the crystal of isocyanic acid. A harmonic theoretical spectrum is calculated then for the proposed structure, and compared with the experimental data. A mixed ice of H2O and CH3NCO was formed by simultaneous deposition of water and methyl isocyanate at 20 K. The absence of new spectral features indicates that methyl isocyanate and water do not react appreciably at 20 K, but form a stable mixture. The high CH3NCO/H2O ratio reported for comet 67P/CG, and the characteristic structure of the 2350-2250 cm-1 band, make of it a very good candidate for future astronomical searches.

Keywords: Methods, laboratory, solid state- techniques, spectroscopic-ISM, clouds-infrared, ISM

1. Introduction

Organic isocyanates (R-NCO) have been synthesized since the mid-nineteenth century and their chemistry has been extensively investigated due to their technical applications in the production of polyurethane and polyureas, in the industry of chemical pesticides, and in the preparation of diverse bio-compounds (Saunders & Slocombe 1948; Ozaki 1972). Methyl isocyanate (CH3NCO), the first term in the alkyl isocyanate series, came to notoriety in 1984 when it was identified as the main toxic agent responsible for the Bophal massive poisoning (D´Silva et al. 1986), which is generally regarded as the worst industrial catastrophe to date. Very recently, methyl isocyanate has been detected at the surface of comet 67P/ Churiumov-Gerasimenko (CG) (Goesmann et al. 2015), and in the interstellar medium (ISM) (Halfen et al. 2015; Cernicharo et al. 2016).

Electron diffraction (Eyster et al. 1940; Anderson et al. 1972), microwave (MW) spectra (Curl et al. 1963; Lett & Flygare 1967; Koput 1984; Koput 1986; Kasten et al. 1986) and theoretical calculations (Koput 1988; Sullivan et al. 1994; Zhou & Durig 2009; Reva et al. 2010, Dalbouha et al. 2016) indicate that the CH3NCO molecule is an asymmetric top with a CNC angle of about 140° and a small barrier (≈ 20-30 cm-1) for the torsion of the methyl group. Its large amplitude internal motions (CH3 torsion and CNC bend) complicate the spectral analysis and although the high accuracy of the available experimental data (Cernicharo et al. 2016) has allowed the detection of this molecule in the gas phase of the ISM, an appreciable discrepancy persists in the value of the A rotational constant (Halfen et al. 2015; Cernicharo et al. 2016; Dalbohua et al. 2016).

Possible gas-phase mechanisms for the production of CH3NCO in the ISM have been advanced in the literature (Halfen et al. 2015), but it is more likely that this comparatively “complex” molecule (Herbst & van Dishoeck 2009) be formed through solid phase chemistry (Goesmann et al. 2015) at the surface or in the bulk of ice mantels in cold astronomical media and then released to the gas phase in the transition to higher temperature conditions (Cernicharo et al. 2016). The possibility of detecting methyl isocyanate in astronomical ices is thus enticing. In fact, the first detection of the compound in space was reported for solid material from the surface of comet 67P/CG as a part of the Rosetta mission. It was based on mass spectrometric measurements performed by the COSAC instrument on board the Philae lander (Goesmann et al. 2015). This circumstance was however exceptional and future searches for the molecule in astronomical ices will require infrared (IR) spectroscopy.

Experimental IR and Raman spectra have also been reported for a variety of methyl isocyanate samples (Hirschmann et al. 1965; D´Hendecourt & Allamandola 1986; Sullivan et al. 1994; Zhou & Durig 2009; Reva et al. 2010). The mid IR absorption spectrum is dominated by a very prominent band at about 2350-2250 cm-1 attributed to the antisymmetric stretching of the NCO group. Other bands appear at 3000-2950 cm-1 (CH3 stretchings), 1460-1420 cm-1 (NCO symmetric stretch and CH3 deformations), 1150-1130 cm-1 (CH3 rocking vibration), 870-850 cm-1 (C-N stretching), and 625-580 cm-1 (NCO bendings). The bands of the large amplitude motions appear at lower frequencies: 190-170 cm-1 for the CNC in-plane bending, and 20-30 cm-1 for the CH3 torsion, and have been determined from far IR, Raman and MW spectra (Koput 1986, Sullivan 1994). In spite of their low frequencies, these bands could also have some influence on the mid IR region through combinations with higher frequency modes (Zhou & Durig 2009; Reva et al. 2010; Dalbouha et al. 2016).

Most previous studies, especially the theoretical calculations, have focused on the determination of the structure and spectra of the isolated CH3NCO molecule. IR spectra of liquid and solid methyl isocyanate have also been measured, but they were basically used for a global spectral assignment of vibrational bands. In this work we study the evolution of the IR spectra of solid CH3NCO over the wide temperature range of relevance to astronomical environments. The IR spectrum of CD3NCO has been added as a supplement for the analysis of the spectrum of CH3NCO. We also report the spectrum of CH3NCO diluted in water ice at 20 K, a temperature typical for interstellar cold clouds, and we discuss the phase transition from amorphous to crystalline, at ~90 K. As part of the study we advance a tentative theoretical structure for crystalline CH3NCO, based on Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, and provide an estimate of the IR band strengths of CH3NCO in ice that might be of help for future astronomical searches.

2. Experimental

The synthesis of Han et al. (1989) was modified to prepare methyl isocyanate (CH3NCO) and fully deuterated methyl isocyanate (CD3NCO). Silver cyanate (15.0 g, 0.1 mol), dry diethyleneglycol dibutyl ether (25 mL) and iodomethane (7.10 g, 50 mmol) or iodomethane-d3 (7.25 g, 50 mmol) were mixed together in a cell equipped with a magnetic stirring bar and a stopcock. The cell was immersed in a liquid nitrogen bath and degassed. The mixture was heated under stirring at 90°C for 20 h. The cell was then fitted on a vacuum line (0.1 mbar) equipped with two traps and low boiling compounds were distilled. The first trap was immersed in a bath cooled at -30°C to remove high boiling compounds. The low boiling methyl isocyanate was selectively condensed in the second trap immersed in a liquid nitrogen bath. The yield was 40%. The deuterated species was characterized by 13C NMR spectroscopy: CD3NCO: 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 27.4 (sept., 1JCD = 21.7 Hz, CD3), 121.4 (s brd, NCO). (Caution! Methyl isocyanate is a highly-toxic, severe lachrymatory agent and should be handled with care).

The set-up for infrared spectroscopy of ices has been described in detail in previous publications (Maté et al. 2003; Gálvez et al. 2008; Maté et al. 2014) and only the details relevant to the present investigation are given here. It consists of a vacuum chamber with a closed-cycle He cryostat, coupled to a FTIR spectrometer. Inside the chamber, solid layers of methyl isocyanate were deposited from the vapor phase on an IR transparent Si substrate in contact with the head of the cryostat. The CH3NCO and CD3NCO vapors were introduced by means of a needle valve connecting the chamber with a small pyrex flask containing approx. 5 ml of liquid methyl isocyanate. For a better handling of the vapor flow to the chamber, the flask was held in an ice bath or in a bath with ice and salt. The liquid samples were subjected to three freeze-pump-thaw cycles for degassing before allowing methyl isocyanate into the vacuum chamber. Deposits were formed at substrate temperatures of 20 and 110 K. Deposition pressures in the ≈ 10-6 mbar range and deposition times of several minutes were typically used. Normal incidence transmission spectra were recorded with a Bruker Vertex 70 FTIR spectrometer coupled to the vacuum chamber through two KBr windows. The spectra were recorded with a resolution of 2 cm-1 using a HgCdTe (MCT) detector refrigerated with liquid nitrogen.

Absolute gas-phase densities in the deposition chamber were estimated with the help of a calibrated quadrupole mass spectrometer (QMS) placed in a differentially pumped adjacent vacuum chamber and connected to the deposition chamber by a regulation valve. The calibration of the QMS is described in Appendix A1

3. Theoretical Calculations

As far as we know, no X-ray structure has been reported for crystalline CH3NCO. In this work we derive a tentative structure taking as a starting point the crystal of isocyanic acid (von Dohlen & Carpenter 1955). A similar strategy was successfully applied to the study of the structure of schwertmannite (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2010), where a theoretical unit cell based on that of the chemically related akageneite was successfully used for the interpretation of the X-ray data.

In the present work, H atoms in the unit cell of isocyanic acid were substituted by CH3 groups, and the new unit cell was optimized using the CASTEP code (Clark et al. 2005; Refson et al. 2006), a DFT plane-wave, pseudopotential method. At the minimum in the potential energy surface atomic forces and charges were evaluated to predict the harmonic vibrational spectrum. For the optimization process with CASTEP, the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) was chosen with the PBE exchange-correlation functional (Perdew et al. 1996). The Grimme DFT-D2 correction (Grimme 2006) was also applied. The convergence criteria were set at 1 × 10-5 eV/atom for the energy, 0.02 eV/Å for the interatomic forces, 830 eV for the cut off energy, maximum stress 0.05 GPa and 0.001 Å for the displacements.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Infrared spectra and phase transition

Mid-IR spectra of CH3NCO and CD3NCO solid samples formed by vapor deposition at 20 K are shown in Fig. 1. At this temperature, which is typical for the grain mantels in interstellar dense clouds, amorphous solids are formed. The spectra are dominated by an intense band, with a quadruplet structure between 2360 and 2200 cm-1, shown in the insets of Fig. 1, which corresponds to the antisymmetric stretching vibration of the NCO group, νa-NCO. The band spans roughly the same wavenumber region for the two isotopic variants, but the internal structure of the band and relative intensity of the maxima are isotope dependent.

Figure 1.

Mid-IR spectra of solid methyl isocyanate and fully deuterated methyl isocyanate deposited at 20 K from the vapor phase.

The assignment of all normal mode vibrations observed in the 3100-550 cm-1 range is given in Table 1. Minor features, not listed in the table, can also be discerned in the spectra. They are likely due to overtones or combination bands. We are only aware of a previous mid-IR spectrum of amorphous CH3NCO reported by D´Hendecourt and Allamandolla (1986), but in this spectrum the most intense band was saturated. The rest of the bands are in good agreement with those of Fig. 1. A vibrational spectrum of CD3NCO is presented here for the first time.

Table 1.

Observed IR absorption wavenumbers (cm-1), and assignment of the spectrum of amorphous methyl isocyanate (vapor deposited at 20 K). Symbols ν, δ, β and r stand for stretch, deformation, bending and rocking vibrations respectively. Subindices a and s denote antisymmetric and symmetric modes. The wavenumber of the maximum peak within the νa-NCO band is given in bold.

| CH3NCO | CD3NCO | Assignment |

|---|---|---|

| 3000 | νa-CH3 | |

| 2958 | νs-CH3 | |

| 2327, 2298 2278, 2246 |

2335, 2285, 2258, 2233 |

νa-NCO |

| 2132 | νa-CD3 | |

| 2085 | νs-CD3 | |

| 1456 | δa-CH3 | |

| 1443 | 1444 | νs-NCO |

| 1412 | δs-CH3 | |

| 1135 | r-CH3 | |

| 1094 | δa-CD3 | |

| 1056 | δs-CD3 | |

| 887 | r-CD3 | |

| 850 | 802 | ν-CN |

| 616 | 616 | β-NCO |

The assignment of the three peaks between 1456 and 1412 cm-1 in CH3NCO is not unanimous and they are sometimes interchanged in the literature (Sullivan et al. 1994; Zhou & Durig 2009, Reva et al. 2010). DFT calculations of the molecular spectrum show that the νs-NCO vibration is largely mixed with bending CH3 motions (Reva et al. 2010). In any case, the contribution of the symmetric NCO stretch to the overall absorption in this frequency interval is small as clearly seen in the spectrum of CD3NCO, where methyl bending modes are red-shifted upon deuterium substitution and only a small peak corresponding to νs(NCO) is left at 1444 cm-1.

In the amorphous solids, the components of the νa-NCO band are not resolved. For CH3NCO, a similar band pattern, albeit with full resolution of the four band peaks, is observed in the matrix experiments of Reva et al. (2010), carried out at temperatures between 8 and 20 K. The band is perturbed by interaction with lower frequency modes. The splitting in multiple peaks has been attributed to a coupling of the NCO asymmetric stretch with the torsion of the methyl group (Reva et al. 2010). In addition, second order perturbation theory calculations (Dalbouha et al. 2016; Senent 2017) show that the band maximum is red-shifted by more than 10 cm-1 with respect to the harmonic value due to a Fermi resonance with the δa-CH3 + ν-CN combination band. Both the Fermi resonance and the torsion of the methyl group are affected by the H/D substitution, which might explain the change in the band profile between CH3NCO and CD3NCO observed in the insets of Fig.1

Experimental band strengths for CH3NCO can be useful for astronomical observations and are listed in Table 2. They were determined using the expression:

| (1) |

where A′i is the strength of band i, NCH3NCO the column density of methyl isocyanate, and the integral of the optical depth is obtained from the measured integrated absorbance (absorbance = τ(ν)/ln 10) over the frequency range of band i. The column density of CH3NCO was obtained using the measured gas-phase density (see section 2) and assuming a sticking probability of one for deposition at 20 K:

| (2) |

where nCH3NCO is the molecular density of gas-phase methyl isocyanate in the chamber, which was kept constant during deposition, and all other parameters were defined above.

Table 2.

Experimental band strengths for the observed absorptions of CH3NCO. The uncertainty in the value of the νa-NCO band is of the order of 30% due mostly to the inaccuracy in the estimate of the column density. For the weakest bands, the uncertainty may be 40%.

| Peak (cm-1) | Wavenumber range (cm-1) | Wavelength range (μm) | A´ (cm molec-1) | band assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3000 | 3035-2979 | 3.29-3.36 | 8.8 × 10-19 | νa-CH3 |

| 2958 | 2977-2930 | 3.36-3.41 | 1.4 × 10-18 | νs-CH3 |

| 2278 | 2432-2160 | 4.11-4.63 | 1.3 × 10-16 | νa-NCO |

| 1443 | 1492-1427 | 6.70-7.01 | 4.9 × 10-18 | δa-CH3 + νs-NCO |

| 1412 | 1428-1396 | 7.04-7.16 | 1.2 × 10-18 | δs-CH3 |

| 1135 | 1076-1100 | 9.29-9.09 | 1.8 × 10-18 | r-CH3 |

| 850 | 880-820 | 11.36-12.19 | 4.6 × 10-18 | ν-CN |

| 616 | 670-550 | 14.92-18.18 | 1.4 × 10-18 | β-NCO |

The band strengths estimated from the measured spectra using equation (1) are termed “apparent”, as opposed to “absolute”, which are derived from optical constants (see for instance Hudson et al. 2014). Apparent band strengths include losses due to reflection and interference that can be substantial for thin ice samples. For the typical thickness of the present samples (≈ 150 μm) these effects are expected to be small. As for the experimental error of the magnitudes derived the main uncertainty in the integral of equation (1) is the subtraction of the baseline which is estimated to be ≈ 5% for the νa-NCO band and up to ≈ 20% for the weakest peaks. The error in the value of the column density is of the order of 30% and is due to the uncertainty in the gas-phase density of CH3NCO during deposition (see Appendix A1). Consequently, the uncertainties in the estimated band strengths are in the 30-40% range.

The most intense band (νa-NCO) has a strength comparable to that reported for the same vibration in solid isocyanic acid at 145 K (1.6 × 10-16 cm molec-1) by Lowenthal et al. (2002) and is of the order of other stretching vibrations of common ice components (CO, CO2, CH3OH…) (Gerakines et al. 1995; Bouilloud et al. 2015). D´Hendecourt and Allmandola (1986) reported an IR spectrum for pure solid CH3NCO at 10 K. In their measurements, the νa-NCO band was saturated and they could only provide a lower limit of 10-16 cm molec-1 for the band strength, which is consistent with the present determination. In addition, they gave a value of 7.5 × 10-18 cm molec-1 for the band at 2958 cm-1 and of 2.8 × 10-18 cm molec-1 for the band at 1135 cm-1, which they attributed to a CO stretching vibration, but noted that these values were very uncertain. The latter value is in reasonable agreement with our result, but that for the 2958 cm-1 band is too large. We believe that there might be a mistake in the value reported by D´Hendecourt and Allamandola (1986) for this band strength, since in their experimental spectrum (and in that of the present work) the two bands have comparable intensities.

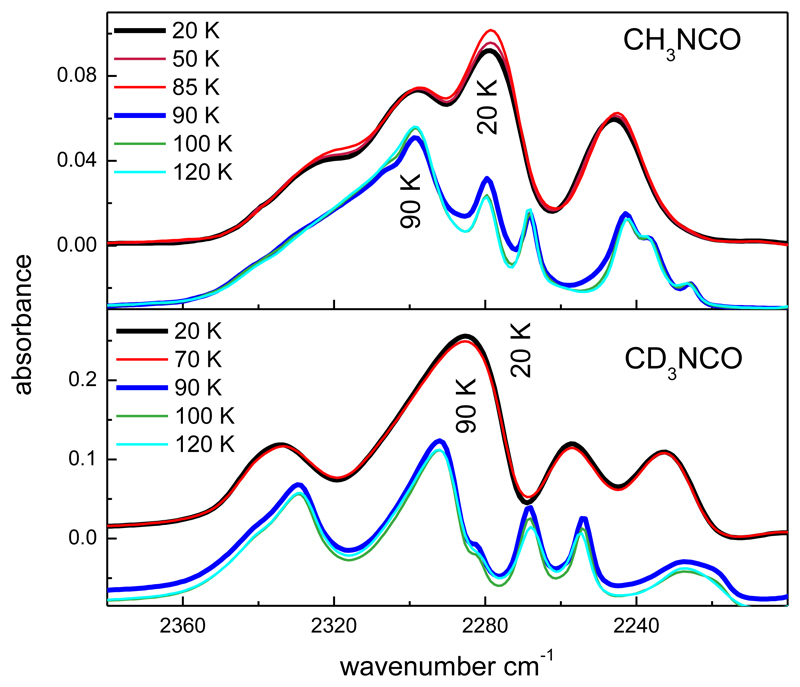

The spectra of the solid deposits hardly change with rising temperature over the 20-85 K range, but heating to ≈ 90 K leads to appreciable variations in the band shapes and shifts in the absorption maxima. Overall the peaks become sharper and in many cases split or grow shoulders, as exemplified in Fig. 2 for the νa-NCO band. These changes are indicative of sample crystallization and are due to the growing order and geometric restrictions for the molecules in a crystalline frame, which result in different environments for a given functional group. Above this temperature, the spectra remain stable until sublimation which takes place at about 130 K.

Figure 2.

Evolution of the νas-NCO band with temperature for the 20 K solid deposits of CH3NCO and CD3NCO. A shift downward of -0.03 and -0.08 is introduced in the absorbance axis of the spectra taken in the range 90-120 K for CH3NCO and CD3NCO, respectively, for a better visualization. Note the splitting of the third peak in order of decreasing wavenumber.

The stability of the CH3NCO spectra in the 20-85 K range questions the qualitative model of Reva et al. (2010) in which the quadruplet structure of the band is attributed to a coupling of stretching and torsional modes. The model interprets the band profile in terms of transitions from the ground state and the first state of the CH3 torsion to v=1 of νa-NCO and v=0, 1 and 2 of the torsion. The first torsional level, at ≈ 20-30 cm-1 (Reva et al. 2010), must be appreciably populated even at 20 K. When the temperature is increased from 20 to 85 K, the population distribution of the torsional levels should change noticeably, leading to significant variations in the band contour which are not observed. In spite of this shortcoming of the model, some coupling of stretching with torsional modes remains a plausible explanation for the quadruplet, especially considering that the experimental νa-NCO band of HNCO has just one peak (Teles et al. 1989; Lowenthal et al. 2002) and that the estimated spacing between torsional levels is roughly comparable to the separation between the observed band peaks (Reva et al. 2010).

For crystalline CD3NCO, the location of the band maximum does not change much with respect to the amorphous sample (see lower panel of Fig. 2), but for crystalline CH3NCO (upper panel), the maximum appears at 2300 cm-1, more than 20 cm-1 higher than the maximum of the amorphous solid (see Table 1). The different band profiles and specifically the frequency shift of the maximum should be considered in possible searches for frozen methyl isocyanate in astronomical environments above or below ≈ 90 K.

4.2. Theoretical model of crystalline CH3NCO

The starting point for a tentative crystalline structure for CH3NCO was the unit cell of isocyanic acid. X-ray measurements have shown that HNCO has four molecules and orthorhombic symmetry (von Dohlen 1955). As a check of consistency, the observed structure of isocyanic acid itself was first relaxed. Table 3 compares the cell parameters of the DFT optimized structure for HNCO with those obtained from the X-ray data.

Table 3.

Experimental unit cell parameters of isocyanic acid and calculated values for isocyanic acid and methyl isocyanate.

| Unit cell dimensions | HNCO X-ray, ref. [doh55] |

HNCO This work (DFT) |

CH3NCO This work (DFT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| a (Å) | 10.82 | 10.93 | 12.57 |

| b( Å) | 5.23 | 5.05 | 6.26 |

| c (Å) | 3.57 | 3.57 | 3.63 |

| α (deg) | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β (deg) | 90 | 90 | 89.52 |

| γ (deg) | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| V (Å3) | 202.02 | 197.06 | 286.12 |

The calculations reproduce the HNCO cell dimensions within 2% and maintain the orthorhombic crystal structure. The crystallographic data yield N….N distances of 3.07 Å and N….C-N angles of 120.6° which are suggestive of the presence of N-H….N hydrogen bonds. Very similar values (3.01 Å and 119.7° respectively) are obtained in the present calculations, which confirm the existence of N….H hydrogen bonds, for which a bond length of 1.89 Å is predicted. The calculations corroborate also the conclusion of the X-ray work on the absence of H….O hydrogen bonds, that are precluded by geometrical constraints.

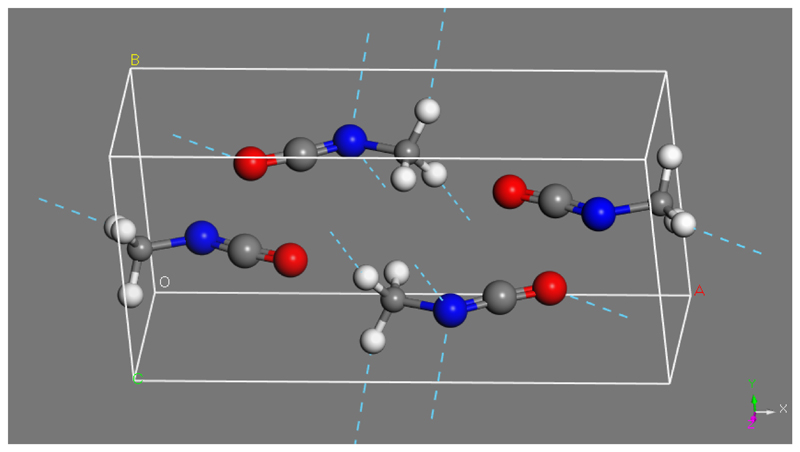

The H atoms in the isocyanic molecules were then substituted by methyl groups, and the structure was relaxed. The optimized values for the unit cell of methyl isocyanate are also listed in Table 2. The crystal is monoclinic, but very close to orthorhombic, since only one angle (β=89.52°) deviates slightly from 90°. The cell volume is increased as expected due to the inclusion of CH3 groups. Two types of hydrogen bonds are identified in the modelled CH3NCO crystal: 1) a C-H….O bond with an H….O distance of 2.43 Å and a C-H….O angle of 157°, and 2) a weaker C-H….N bond, with a H….N distance of 2.66 Å and a C-H….N angle of 160°. The predicted structure is displayed in Figure 4. Hydrogen bonds in this figure are represented by dashed lines. The zigzag ordering of the NCO units, observed in the original HNCO crystal (von Dohlen 1955), is maintained in CH3NCO

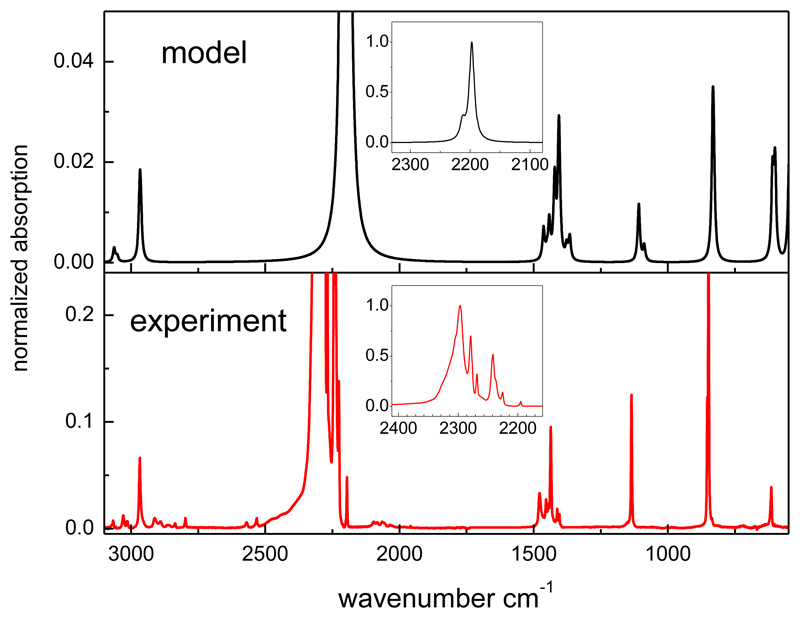

Figure 4.

Comparison of calculated (upper panel) and experimental (lower panel) spectra for crystalline CH3NCO. Both spectra are normalized to one at their maximum peaks (see inset). Note the differences in the vertical scales for the weaker absorptions.

A harmonic theoretical spectrum was calculated for the proposed structure. The unit cell of the crystal has 81 vibrational normal modes, which in the mid-IR correspond mainly to combinations of vibrations of functional groups of the individual molecules. Many of these modes are infrared inactive because the corresponding molecular vibrations cancel each other by symmetry and do not give rise to a net change of the dipole moment in the cell. In Table 4, the modes active within a given wavelength interval are grouped and assigned. Calculated band strengths are also listed. The band strength is obtained by adding the strengths of the individual modes in the interval of interest; this value is then divided by four to account for the number of molecules in the unit cell. The approximate assignment gives the predominant vibration for the interval considered. In many cases, more than one type of molecular vibration contributes to a given mode. There is no single mode of the crystal that contains the νs-NCO vibration alone; it appears always mixed with CH3 deformations. Note that this vibration was observed to be weak, and also mixed with CH3 deformations in the amorphous solid (see above) and in the isolated molecule (Reva et al. 2010).

Table 4.

Assignment and band strengths of the theoretical IR spectrum of crystalline methyl isocyanate in the 3100-500 cm-1 range. The assignments are approximate and correspond to the predominant vibrations in the indicated wavenumber intervals.

| Wavenumber range (cm-1) | assignment | Band strength (cm/molec) |

|---|---|---|

| 3080-3020 | νa-CH3 | 1.45 × 10-18 |

| 2987-2933 | νs-CH3 | 5.55 × 10-18 |

| 2327-2066 | νa-NCO | 2.74 × 10-16 |

| 1480-1340 | δs-CH3 + νs-NCO + (νa-NCO) | 1.60 × 10-17 |

| 1107-1074 | r-CH3 | 3.52 × 10-18 |

| 870-791 | ν-CN | 1.00 × 10-18 |

| 663-569 | β-NCO | 1.09 × 10-17 |

| 570-508 | β-NCO | 5.18 × 10-18 |

The calculated band strengths for the theoretical crystal are roughly a factor two larger than the experimental band strengths for the amorphous solid. This result may be considered acceptable, keeping in mind that the theoretical structure is just a prediction, the approximations involved in the theoretical model, and the uncertainty in the experimental measurements. The theoretical spectrum is compared in Fig. 4 with an experimental spectrum of crystalline CH3NCO obtained by vapor deposition at 110 K.

For the comparison, the calculated vibrational modes have been represented by Gaussian functions of 10 cm-1 FWHM and the two spectra have been normalized to one at their highest peaks (see insets in Fig. 4). The calculations reproduce reasonably well the pattern of weaker absorptions over the 3100-700 cm-1 range, and account partly for the structure observed around 3000 cm-1 and 1400 cm-1 due respectively to CH3 stretchings and deformations. However, the intensities of these absorptions with respect to the strongest peak in the spectrum are too weak as compared to the experimental ones.

The dominant theoretical band is in worse agreement with the experiment. The theoretical peak is calculated at 2174 cm-1 whereas the experimental one is found at 2300 cm-1, and the multiplet structure of the measured band is also not reproduced in the calculations. The discrepancy is hardly surprising since, in addition to the very approximate nature of the proposed crystal structure, the harmonic model used for the calculation of the spectra is not expected to account for the strong perturbations of this band, already commented on in the discussion of the amorphous solid spectra. The fact that the theoretical νa-NCO band intensity appears concentrated in a single peak explains, at least partially, the lower relative intensities of the rest of the theoretical bands shown in Fig. 4.

4.3. Methyl isocyanate in water ice

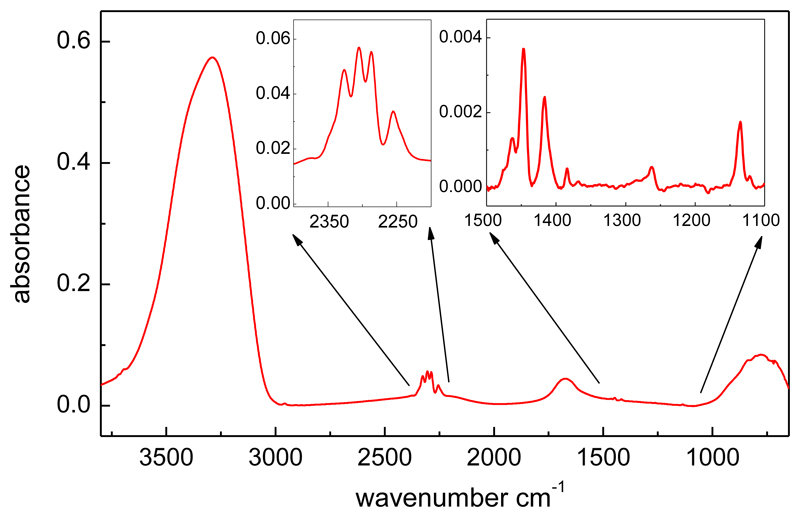

The spectrum of a mixture of H2O and CH3NCO ice is displayed in Fig. 5. The mixed ice was formed by simultaneous deposition of water and methyl isocyanate at 20 K. The CH3NCO/H2O molecular ratio in the gas phase was ≈ 2.7 %. At this deposition temperature, the sticking coefficient should be nearly one for the two species and, considering that the collision frequency of molecules of mass mi with the substrate surface is proportional to mi-0.5, the ratio of CH3NCO molecules in the mixed ice is estimated to be ≈ 1.5 %, which is close to the CH3NCO/H2O proportion (1.3 %) found in the material excavated by the COSAC instrument at the surface of comet 67P/CG.

Figure 5.

Spectrum of a mixture of H2O and CH3NCO. The molecular ratio of methyl isocyanate is ≈ 1.5% (see text). Insets show enlargements of the 2200-2400 cm-1 and 1100-1500 cm-1 intervals.

The spectrum is dominated by the intense, broad OH stretching, ν(OH), band of water at 3288 cm-1. Typical water absorptions corresponding to bending (β ≈ 1670 cm-1) and libration (r ≈ 780 cm-1) vibrations also stand out in the spectrum. The νa-NCO band, with its characteristic quadruplet structure, is clearly visible too. It is located on top of a broad H2O absorption attributed to a combination band (β + r). The much weaker CH3NCO bands in the 1500-1000 cm-1 range are still appreciable (see right inset in Fig.5). The weak CH3NCO vibrational modes below 900 cm-1 or above 3000 cm-1 are blended with intense water absorptions and are not considered further. No other significant peaks are identified in the spectral region investigated, which indicates that methyl isocyanate and water do not react appreciably at 20 K, but form a stable mixture. The νa-NCO band profile resembles that of amorphous CH3NCO over the 20-85 K range (see Fig. 2), but with noteworthy differences attributable to the different environments felt by the CH3NCO molecules. In the ice mixture, the peaks are sharper and shifted toward higher frequencies, and the second and third peaks have comparable intensities. Under the deposition conditions of this experiment the individual CH3NCO molecules should be surrounded by water molecules within a porous ice structure (Maté et al. 2012a) with an approximate bulk density of 0.65 g/cm3. The peak positions for the four components of the νa-NCO band in different environments are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Wavenumbers of the four maxima in the νa-NCO band of CH3NCO in various environments.

| νa-NCO cm-1 amorph. solid, 20 K, this work | νas (NCO) cm-1 H2O ice, 20 K, this work | νas (NCO) cm-1 N2 matrix, 8 K ref. [rev10] | νas (NCO) cm-1 vapor ref. [sul94] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2327 | 2336 | 2334.7 | 2340 |

| 2298 | 2305 | 2307.9 | 2308 |

| 2279 | 2286 | 2288.9 | 2285 |

| 2246 | 2255 | 2259.7 | 2265 |

The maxima in the spectrum of the amorphous solid are red-shifted by 7-9 cm-1 with respect to those in water ice, which are in general red-shifted with respect to those in the N2 matrix and in the vapor. This trend reflects the degree of perturbation of the molecular vibration by the surroundings. It is worth observing that the shift in frequencies between the ice, where the CH3NCO molecules are embedded in a bulk phase of polar water molecules, and those in the weakly interacting non-polar N2 matrix, are smaller (< 5 cm-1) than those between the amorphous solid and the CH3NCO/H2O ice, which suggests a comparatively strong interaction between the CH3NCO molecules in the amorphous solid.

The band strengths of methyl isocyanate in ice can be estimated from a comparison with the intense ν-OH absorption of water ice, whose band strength is well known (Mastrapa et al. 2009; Bouilloud et al. 2015). If we assume that CH3NCO is component 1 and H2O is component 2 in the ice mixture, the strength of band b of methyl isocyanate, A’1,b can be expressed as:

| (3) |

where A’2,ν(OH) is the band strength of the OH stretching mode of water ice and N2/N1 is the ratio of column densities in the ice. For vapor deposited water ice at 20 K we take A’2,ν(OH)=1.9 × 10-16 cm molec-1 (Mastrapa et al. 2009). We also note that the column density ratio in our experiment is the same as the molecular ratio estimated for the ice: (N2/N1) ≈ 67. The quotient of integrated optical depths can be substituted by the corresponding quotient of integrated experimental absorbances. The band strengths derived from the present measurements are listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Band strengths for CH3NCO absorptions in H2O/CH3NCO (1.5%) ice mixtures co-deposited at 20 K. The estimated uncertainties are 30% for the νa-NCO band and 50% for the rest.

| Peak (cm-1) | Wavenumber range (cm-1) | Wavelength range (μm) | A’ (cm molec-1) | band assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2305 | 2220-2380 | 4.50-4.20 | 1.5 × 10-16 | νa-NCO |

| 1447 | 1435-1485 | 6.99-6.73 | 3.7 × 10-18 | δa-CH3 + νs-NCO |

| 1417 | 1393-1432 | 7.18-6.98 | 1.9 × 10-18 | δs-CH3 |

| 1135 | 1114-1146 | 8.98-8.73 | 1.0 × 10-18 | r-CH3 |

The estimated strength of the νa-NCO band of methyl isocyanate in ice is ≈ 15% higher than that of the same band in pure amorphous CH3NCO (see Table 2) but the two values are within their mutual experimental error. The rest of the band strengths are of the same order than the corresponding ones for pure CH3NCO ice and they also lie within their mutual uncertainties. These bands are probably too weak to be of practical use for astronomical searches.

5. Astrophysical Implications

The discovery of a relatively large proportion of CH3NCO (1.3% with respect to H2O) in the material extracted from the surface of comet 67P/CG came as a surprise to the astronomical community (Goesmann et al. 2015). At that time, this compound had not been detected anywhere in space. Although comets are subjected to a substantial re-processing in their journey through the Solar System, at least part of their components are believed to be remnants from the original molecular cloud that gave rise to the solar nebula, and that could be the case of methyl isocyanate. Shortly after its detection in comet 67P/CG, methyl isocyanate was identified in the gas phase of hot cores in Sgr B2 and Orion (Halfen et al. 2015; Cernicharo et al. 2016). It is believed that the molecule is formed in the ices of molecular clouds and then released from the grains in the transition to the hot core phase (Cernicharo et al. 2016). The estimated CH3NCO/H2O ratio (≈ 0.02%) in hot cores is much lower than that of comet 67P/CG, which suggests that part of the methyl isocyanate in the hypothetic original ices may remain in the solid phase during cloud collapse and be incorporated to cold bodies in planetary systems.

The obvious spectroscopic feature for a search of CH3NCO in interstellar ices is the intense νa-NCO band at ≈ 2220-2350 cm-1 (4.25-4.50 μm) discussed throughout this work. This frequency interval is not adequate for observations from Earth, since it overlaps partly with the lower frequency wing of the atmospheric CO2 absorption at ≈ 2349 cm-1 (4.26 μm). Data from space based observatories have become available over the last decades both for massive young stellar objects (YSOs) (Gibb et al. 2004; Dartois 2005) and for low-mass YSOs (Boogert et al. 2008; Oberg et al. 2011; Boogert et al. 2015). In interstellar ices, the strong absorption of CO2 at 2341 cm-1 can interfere somewhat with the νa-NCO band of CH3NCO. However, the mentioned CO2 absorption is narrow and for typical CO2 ice concentrations (Boogert et al. 2015) the perturbation should be limited to the high frequency edge of the methyl isocyanate band. The Solar System evolved from a low-mass YSO and it is likely that its primeval ices resembled those in this type of objects. An extensive survey of ices in low-mass YSOs was performed in the course of the Spitzer mission (Oberg et al. 2011), but these observations were limited to wavenumbers lower than 2000 cm-1 (λ > 5 μm) and thus do not cover the region of interest here. The 2220-2350 cm-1 (4.25-4.50 μm) spectral interval was actually included in the previous study of a smaller sample of massive YSOs, carried out with the Infrared Space Observatory (ISO) (Gibb et al. 2004; Dartois 2005) but the molecule was not identified. Ices around massive YSOs often show a band at ≈ 2165 cm-1 (4.62 μm), attributed to to OCN- (Hudson et al. 2001, van Broekhuizen et al. 2005; Maté et al. 2012b), which is taken as a signature of the strong ice processing typical for these objects (Boogert et al. 2015) and could be chemically related to isocyanic acid and isocyanates. In fact, Hudson et al. (2001) have shown that electron bombardment of C2H5NCO + H2O ice mixtures leads to the appearance of this OCN- absorption feature probably through a mechanism of dissociative electron attachment. The νa-NCO band of methyl isocyanate should appear between this band and the intense band of CO2 in ice at 4.27 μm. In this region, only a small peak at 4.38 μm, attributed to 13CO has been confidently identified (Boogert et al. 2015). A faint multipeak structure is insinuated in some of the ISO spectra between the two prominent absorptions at 4.25 and 4.62 μm (Boogert et al. 2000), but the signal to noise ratio is too low and the band analysis too complex to draw any conclusion on the presence of other species. A detailed investigation of this region in low-mass YSOs would be worthwhile since they are more representative of the early Solar System. As discussed by Boogert et al. (2008) in their thorough analysis of Spitzer data, identification of minor ice species in the IR spectra is a complex task due to the concurrence of many possible carriers with the consequent overlapping of spectral bands in the naturally weak absorption features. In this respect, methyl isocyanate may be an exception. The high CH3NCO/H2O ratio reported for comet 67P/CG, and the characteristic multiplet structure of its intense νa-NCO band, which is constrained between well-known CO2 and XCN absorptions, make of it a very good candidate for searches with the new generation of high resolution up-coming facilities like the James Webb Space Telescope.

6. Conclusions

After the discovery of methyl isocyanate on comet 67P/ Churyumov-Gerasimenko, this molecule has become the target of several astrophysical studies. We present here new results based on laboratory and theoretical investigations. The main conclusions are the following:

The spectra of CH3NCO present several interesting features. The most outstanding is a strong, complex band at ~ 2300 cm-1, assigned to the asymmetric stretch of the NCO backbone. It has four components whose origin is not yet fully understood. The structure of this zone is maintained upon warming up to 85 K, but it shows wavenumber shifts and rearrangements when methyl isocyanate is mixed with water, in a N2 matrix, or in gas phase. Thus, this feature could reveal interesting information on the nature and surroundings of CH3NCO if detected in ice form in astrophysical media other than comets.

The evolution of the spectra with temperature allows observing a phase change from amorphous to crystalline at 90 K. Besides the usual sharpening of IR bands, some wavenumber shifts take place associated to this phase transition, especially again in the NCO band.

This vibration is also strong in the spectrum of CD3NCO, in the same wavenumber region, but with a slightly different pattern. Further studies on this subject would be highly interesting.

The crystalline structure of CH3NCO was not known. We have derived a tentative structure based on that of isocyanic acid, HNCO, for which some information was available. The results of the model seem acceptable concerning the structure of the unit cell, the bonding among the four enclosed molecules, and the predicted IR spectrum.

For astrophysical purposes, band strengths are of key importance. We have measured these values for the spectra of CH3NCO and of CH3NCO/H2O ices at 20 K. Good agreement is obtained with the scarce previous information on these data.

Analysis of the spectrum of CH3NCO/H2O ice at 20 K does not disclose any features indicative of the formation of new species. Therefore, although CH3NCO reacts with H2O at higher temperatures, it seems to form a stable mixture at 20 K.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3.

(color online). Tentative structure of the unit cell of mrthyl isocyanate. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to P. C. Gómez, M. L. Senent and M. A. Moreno for helpful discussions. This work was funded by the European Union under grant ERC-2013-Syg 610256 (NANOCOSMOS) and by the Spanish MINECO CSD2009-00038 (ASTROMOL) within the Consolider-Ingenio Program. MINECO funding from grants FIS2013-48087-C2-1P, FIS2016-C3-1P, AYA2012-32032, and AYA2016-75066-C2-1-P is also acknowledged. J.-C.G. and J.C. also thank the ANR-13-BS05-0008 IMOLABS and J.-C.G. thanks the Program PCMI (INSU-CNRS) and the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) for funding support.

References

- Anderson DW, Rankin DWH, Robertson A. JMoSt. 1972;14:385. [Google Scholar]

- Boogert ACA, Ehrenfreund P, Gerakines PA, et al. A&A. 2000;353:349. [Google Scholar]

- Boogert ACA, Gerakines PA, Whittet DCB. Annu Rev Astron Astrophys. 2015;53:541. [Google Scholar]

- Boogert ACA, Pontoppidan KM, Knez C, et al. ApJ. 2008;678:985. [Google Scholar]

- Bouilloud M, Fray N, Bénilan Y, Cottin H, Gazeau MC, Jolly A. MNRAS. 2015;451:2145. [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo J, Kisiel Z, Tercero B, et al. A&A. 2016;587:L4. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201527531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SJ, Segall MD, Pickard CJ, Hasnip PJ, Probert MJ, Refson K, Payne MC. Z Krist. 2005;220:567. [Google Scholar]

- Curl RS, Sasty KVL, Rao VL, Hodgeson JA. JChPh. 1963;39:3335. [Google Scholar]

- Dalbouha S, Senent ML, Komiha N, Domíngez-Gómez R. JChPh. 2016;145 doi: 10.1063/1.4963186. 124309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dartois E. Space Sci Rev. 2005;119:293. [Google Scholar]

- D´Hendecourt LB, Allamandola LJ. ApJSS. 1986;64:453. [Google Scholar]

- D´Silva TDJ, Lopes A, Jones RL, Singhagwangcha S, Chan JK. J Org Chem. 1986;51:3781. [Google Scholar]

- Eyster EH, Gillette RH, Brockway LO. JACS. 1940;62:3236. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Martínez A, Timón V, Román-Ross G, et al. Amer Mineral. 2010;95:1312. [Google Scholar]

- Gálvez O, Maté B, Herrero VJ, Escribano R. Icarus. 2008;197:599. [Google Scholar]

- Gerakines PA, Schutte WA, Greenberg JM, van Dishoeck EF. A&A. 1995;296:810. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb EL, Whittet DCB, Boogert ACA, Tielens AGgM. ApJS. 2004;151:35. [Google Scholar]

- Goesmann F, Rosenbauer H, Brederhöft JH, et al. Sci. 2015;349:aab0689. doi: 10.1126/science.aab0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S. J Comput Chem. 2006;27:1787. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfen DT, Ilyushin VV, Ziurys LM. ApJ. 2015;812:L5. [Google Scholar]

- Han DH, Pearson PG, Baillie TAJ. Lab Comp Radiopharm. 1989;27:1371. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst E, van Dishoeck EF. ARA&A. 2009;47:427. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschmann RP, Kniseley RN, Fassel VA. Spect Acta. 1965;21:2125. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RL, Moore MH, Gerakines PA. ApJ. 2001;550:1140. doi: 10.1016/s1386-1425(00)00448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RL, Ferrante RF, Moore MH. Icarus. 2014;228:276. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W, Kim YK, Rudd ME. JChPh. 1996;104:2956. [Google Scholar]

- Kasten W, Dreizler H. Z Naturforsch A. 1986;41:637. [Google Scholar]

- Koput J. JoMoSp. 1984;106:12. [Google Scholar]

- Koput J. JMoSp. 1986;115:131. [Google Scholar]

- Koput J. JMoSp. 1988;127:51. [Google Scholar]

- Lett RG, Flygare WH. JChPh. 1967;47:4730. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal MS, Khanna RK, Moore MH. Spect Acta. 2002;58:73. doi: 10.1016/s1386-1425(01)00524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Doménech R, Manzano-Santamaría J, Muñoz-Caro GM, et al. A&A. 2015;584:A14. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrapa RM, Sandford SA, Roush TL, Cruikshank DP, D’Alle Ore CM. ApJ. 2009;701:1347. [Google Scholar]

- Maté B, Medialdea A, Moreno MA, Escribano R, Herrero VJ. JPhCh B. 2003;107:11098. [Google Scholar]

- Maté B, Rodríguez-Lazcano Y, Herrero VJ. PCCP. 2012a;14:10595. doi: 10.1039/c2cp41597f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maté B, Herrero VJ, Rodríguez-Lazcano Y, et al. ApJ. 2012b;759:90. doi: 10.1039/c2cp41597f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maté B, Tanarro I, Moreno MA, Jiménez-Redondo M, Escribano R, Herrero VJ. Faraday Disc. 2014;168:267. doi: 10.1039/c3fd00132f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberg KI, Boogert ACA, Pontoppidan KM, et al. ApJ. 2011;740:109. [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki S. Chem Rev. 1972;72:458. [Google Scholar]

- Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77:3865. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refson K, Tulip PR, Clark SJ. Phys Rev B. 2006;73:155114. [Google Scholar]

- Reva I, Lapinski L, Fausto R. JMoSt. 2010;976:333. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JH, Slocombe RJ. Chem Rev. 1948;43:203. doi: 10.1021/cr60135a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senent ML. personal communication. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan JF, Heusel HL, Zunic WM, Durig JR. Spect Acta. 1994;50A:435. [Google Scholar]

- Teles JH, Maier G, Hess BA, Jr, et al. Chem Ber. 1989;112:753. [Google Scholar]

- van Broekhuizen FA, Pontoppidan KM, Frazer KM, van Dishoeck EF. A&A. 2005;441:249. [Google Scholar]

- von Dohlen WC, Carpenter GB. Act Crist. 1955;8:646. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SX, Durig JR. JMoSt. 2009;924:111. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.