Abstract

Academic stratification during educational transitions may be maintained, disrupted, or exacerbated. This study marks the first to use national data to investigate how the transition to high school (re)shapes academic status at the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender. We seek to identify the role of the high school transition in shaping racial/ethnic and gender stratification by contextualizing students’ academic declines during the high school transition within the longer window of their educational careers. Using Add Health, we find that white and black boys experience the greatest drops in their grade point averages (GPAs). We also find that the maintenance of high academic grades between the eighth and ninth grades varies across racial/ethnic and gender subgroups; higher-achieving middle school black boys experience the greatest academic declines. Importantly, we find that white and black boys also faced academic declines before the high school transition, whereas their female student peers experienced academic declines only during the transition to high school. We advance current knowledge on educational stratification by identifying the transition to high school as a juncture in which boys’ academic disadvantage widens and high-achieving black boys lose their academic status at the high school starting gate. Our study also underscores the importance of adopting an intersectional framework that considers both race/ethnicity and gender. Given the salience of high school grades for students’ long-term success, we discuss the implications of this study for racial/ethnic and gender stratification during and beyond high school.

Keywords: gender, race, school transitions, academic achievement, high school

Racial and ethnic disparities and gender gaps in education are critical social problems with profound consequences for social inequality over the life course. Today, phrases like “the trouble with boys,” “the rise of women,” and “racial/ethnic achievement gaps” are pervasive in the public and academic discourse. Disparities in academic grades—a major indicator of academic status and a source of racial/ethnic and gender inequalities in postsecondary education and labor force outcomes—widen across formal schooling. We argue that educational transitions are a point when traditionally marginalized status groups are especially vulnerable (Mickelson 2003; Roderick 2003) and examine the transition from middle school to high school as a potential “crucible period” (Entwisle et al. 1988:174) during which students’ academic status can decline, increase, or remain constant (Entwisle and Alexander 1989; Lucas 2001; Schiller 1999; Schneider, Swanson and Riegle-Crumb 1997). Of particular concern is how boys, and especially racial/ethnic minority boys, fare during the transition.

The current study uses the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) to understand the racial/ethnic and gender patterns in who falls (further) behind and who gets (further) ahead during the transition to high school. We advance scholarship on educational inequality by using national data and an intersectional framework to study academic disparities between racial/ethnic and gender subgroups during the transition from middle school into high school. Specifically, we examine whether grade point average (GPA) gaps between white, black, and Latino/a young men and women are preserved, narrowed, or widened across the transition to high school, recognizing that race/ethnic and gender inequalities likely interact to influence students’ academic status. Ninth grade marks the beginning point when cumulative high school GPA and class rank are defined. These academic indicators are powerful signals of preparation for life after high school. Creating or exacerbating gaps along racial/ethnic and gender lines, this transition can set the tone for the remainder of students’ high school years (Allensworth and Easton 2005; Langenkamp 2011; Roderick and Camburn 1999) and impact college admissions and beyond.

Our study has three objectives that will contribute to the research on racial/ethnic and gender stratification in education. The first is to investigate racial/ethnic and gender differences in academic status indicated by course grades during the transition to high school. Our findings suggest that the transition to high school presents academic risk for all students, but especially for white and black boys. Our second objective builds on research suggesting that students’ risk during the transition to high school differs by their middle school academic standing (Langenkamp 2010, 2011; Schiller 1999). Our results suggest that the preservation of high academic status between middle school and high school differs across racial/ethnic and gender subgroups, with high-achieving black boys experiencing the greatest loss and high-achieving white girls experiencing the greatest continuity in academic status between middle school and high school.

In our final objective, we investigate whether the transition to high school is a crucible period during which students unexpectedly gain or lose academic status, or whether it marks a continuation of existing trends and further entrenches academic (dis)advantage. Substantial evidence suggests that status-group advantages and disadvantages accumulate throughout formal schooling (Condron 2009; DiPrete and Jennings 2012; Entwisle, Alexander and Olson 2007; Kerckhoff 1993; Mickelson and Greene 2006; Quiroz 2001). Yet, most research on the transition to high school examines changes in students’ academic performance only between the eighth and ninth grades, typically conceptualizing this period as initiating students’ academic challenges (Barber and Olsen 2004; Benner 2011). However, for marginalized groups, the transition to high school may exacerbate academic declines that began in middle school, and importantly may increase intersectional disparities. We investigate this possibility by taking advantage of the multi-cohort design of Add Health to examine the GPAs of white, black, and Latino/a boys and girls across seventh through tenth grades. We find that whether the high school transition sparks or exacerbates academic risk in students’ educational careers varies between racial/ethnic and gender subgroups.

The current study adds new insights on the contours of educational inequality by investigating whether students’ relative academic status evolves along the intersecting axes of race/ethnicity and gender rather than academic performance history. Given the primary role that differences in high school GPA play in racial/ethnic and gender disparities in college attendance, success, and completion (Buchmann and DiPrete 2006; Massey and Probasco 2010), studying who gets ahead and who falls behind at the high school starting gate has important implications for educational stratification both within and beyond high school.

BACKGROUND

Transitions are theoretically significant because they may result in the maintenance of the status quo, in the further accumulation of (dis)advantage, or in turning points that exacerbate or narrow inequalities as students interact with the structure of schooling (Benner 2011; Langenkamp 2011; Laub and Sampson 1993; Pallas 2003). Research suggests that higher-status groups are better able to preserve their relative academic advantage during educational transitions (Lucas 2001), and that discrimination and teacher biases against lower-status groups are heightened when students move through stages of schooling (Kerckhoff 1993; Mickelson 2003).

Higher academic status is unevenly distributed in schools along racial/ethnic and gender lines. Studies on the transition to high school have focused either on race/ethnic or gender differences in academic status. However, theories of intersectionality stress that race/ethnicity and gender cannot be viewed in isolation because these systems of inequality combine to shape both privilege and disadvantage within institutions (Collins 2010; Crenshaw 1991; McCall 2001). Previous work underscores the value of an intersectional approach for unpacking how schools affect racial/ethnic and gender inequalities in educational outcomes (Irizarry 2015; Morris 2006; Riegle-Crumb and Humphries 2012). Building on this research, we argue that race/ethnicity and gender are dimensions of inequality that interact to shape students’ academic vulnerability during the transition to high school.

Academic Performance at the Intersection of Race/Ethnicity and Gender

Most research documents declines in students’ academic performance between the eighth and ninth grades (Barone, Aquirre-Deandries and Trickett 1991; Benner and Graham 2009; Felner, Primavera and Cauce 1981; Gillock and Reyes 1996; Isakson and Jarvis 1999; Roderick 2003; Seidman et al. 1996; Weiss and Bearman 2007). The few studies that consider racial/ethnic or gender differences in academic performance during the transition have inconsistent findings. For example, some studies find that racial/ethnic minorities (Benner and Graham 2009; Felner et al. 1981) and boys (Roderick 2003; Roderick and Camburn 1999) experience the greatest academic declines during the transition to high school. Older studies analyzing samples from a single high school found that racial/ethnic minority students do not experience worse academic outcomes compared to white students (Barone, Aquirre-Deandries and Trickett 1991; Seidman et al. 1996). Additionally, Aprile Benner and Sandra Graham (2009) document greater female declines in GPA. These disparate findings may result from differences in student populations and schools between the urban cities (from Chicago to Los Angeles) in which these studies were based. Furthermore, not considering both race/ethnicity and gender may mask important subgroup differences across the transition to high school. We rely on national data that allow us to consider racial/ethnic and gender subgroups.

Empirical research utilizing theories of intersectionality suggests that assuming homogeneity within gender or racial/ethnic groups obscures differences in academic outcomes (e.g., Morris 2006; Noguera 2003; Riegle-Crumb and Humphries 2012). A few studies suggest that male students of color may experience greater declines in grades between middle school and high school than other racial/ethnic and gender subgroups. Specifically, Melissa Roderick (2003) found that black boys attending a predominately black middle school in Chicago experienced greater academic declines during the transition to high school relative to black girls. Moreover, Roderick and Camburn (1999) found that boys from all racial/ethnic backgrounds in public schools in Chicago—especially Latino boys—were more likely to experience course failure than girls, net of other factors. Given boys’ lower levels of academic performance and engagement (DiPrete and Jennings 2012; Jacob 2002; Johnson, Crosnoe and Elder 2001; Mickelson and Greene 2006), they may be less prepared to meet the heightened demands of high school. Young men of color may also face greater difficulty forming productive relationships with teachers (Carter 2007; Ferguson 2001; Morris 2006) at a time when doing so is more challenging yet vital to academic success (Langenkamp 2010, 2011; Roderick 2003). Using an intersectional approach, our first objective builds on studies based on a single school or district and investigates whether there are significant racial/ethnic and gender differences in students’ academic declines between the eighth and the ninth grades. We consider the roles of teacher attachment and academic engagement in explaining any observed disparities.

Race/Ethnicity and Gender and the Preservation of Academic Status

High school marks a point of both heightened competition for grades, especially among students vying for top slots, and pressure on schools to ensure that struggling students graduate from high school. However, a student’s middle school academic standing may condition the effects of a transition, allowing students with low grades to improve their academic standing while those with high grades experience downward mobility (Langenkamp 2010, 2011; Schiller 1999). We build on this work in our second objective; we investigate whether the strength of the link between earlier (eighth grade) and later (ninth grade) performance differs by racial/ethnic and gender subgroup membership.

Status-group inequalities in education may be re-established and further entrenched during pivotal school junctures (Kerckhoff 1993; Lucas 2001; Mickelson 2003). We posit that whether high achieving middle school students preserve or lose their academic status by the end of ninth grade differs at the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender. We base our empirical expectations on research demonstrating that teachers perceive students along stereotyped lines and studies suggesting when stereotypes are most salient in decision making.

Research indicates that lower-status groups are held to higher ability standards than higher-status groups (Biernat and Kobrynowicz 1997; Foschi 1996), reflected in Stephen Carter’s (1993:58) popularized assertion that black individuals “have to work twice as hard to be considered half as good” as white individuals. Students are affected by racialized and gendered stereotypes across schooling, with studies demonstrating that teachers’ perceptions of students’ performance are influenced by racial/ethnic and gender stereotypes even when contradicted by actual measures of achievement or behavior (e.g., Ferguson 2001; Irizarry 2015; Morris 2006; Riegle-Crumb and Humphries 2012). In fact, research shows that teachers evaluate high-achieving racial/ethnic minority students more negatively than high-achieving white students (Irizarry 2015). Teachers’ perceptions of students matter because teachers assign course grades based on students’ class performance and their perceptions of students’ cognitive and non-cognitive skills (Farkas et al. 1990; Kelly 2008).

These processes may be especially pronounced during the transition to high school because stereotypes are heightened in more anonymous environments (Irvine 1990) and in situations where decision makers have little information about individuals (Guttmann and Bar-Tal 1982). Indeed, research suggests that racial/ethnic minorities may be most susceptible to discrimination during school transitions when critical decisions are made that influence students’ next stage of schooling, or what Mickelson (2003:1071) referred to as “loci of discrimination.”

Based on this research, we expect that the continuity of academic performance between middle school and high school will be strongest for students whose academic performance is consistent with dominant racial/ethnic and gender stereotypes and weakest for individuals whose middle school academic performance diverges from the academic stereotypes associated with their status group. Because white girls typically earn high academic grades and teachers generally perceive their comportment to align with that of an “ideal student,” we expect that the transition to high school will have the weakest negative impact on the freshman year grades of white girls who earned good grades in middle school, possibly giving them a relative advantage. Given that young black men are a highly marginalized racial/ethnic and gender subgroup throughout schooling, we expect high performing black male middle school students to experience the greatest discontinuity in academic grades during the transition. Our second objective estimates this possibility.

The Transition to High School and the Adjacent Years

Our final objective builds on substantial evidence that how students fare during school transitions must be considered within the context of individuals’ longer academic trajectories that are shaped within a school system in which educational inequalities increase over time (Benner 2011; Condron 2009; Entwisle et al. 2007; Kerckhoff 1993; Quiroz 2001). While the high school transition may precipitate a negative turning point for some students, for others it may extend an existing trend of academic losses. The transition may represent for subpopulations who experience early academic marginalization yet one more step in a process that sorts students according to race/ethnicity and gender rather than their individual prior academic performance. Only a couple studies—both focused on a single school district—have examined changes in students’ academic grades during the grade progressions adjacent to the high school transition, and neither considered students’ academic performance at the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender (Barber and Olson 2004; Benner and Graham 2009). As a result, we do not know whether changes in academic status during the high school transition represent discontinuity or continuity within students’ academic trajectories or whether the answer to this differs across racial/ethnic and gender subgroups.

Contextualizing the transition to high school within the adjacent years is especially critical when investigating the role of the high school transition in shaping the academic performance of boys and girls from different racial/ethnic backgrounds, and is a specific contribution of the current study. Indeed, research demonstrates that the black-white achievement gap increases throughout the entire formal schooling process (Jacobson et al. 2001; Phillips, Crouse and Ralph 1998), and, unlike disparities by social class, these gaps are exacerbated during the school year (Condron 2009). School processes may heighten the academic risks for marginalized subgroups.

Racial/ethnic minority students, boys, and especially black boys, receive lower grades than other groups (e.g., DiPrete and Jennings 2012; Entwisle et al. 2007; Nord et al. 2011; Willingham and Cole 1997) and experience challenges forming constructive relationships with teachers across schooling (Carter 2007; Entwisle et al. 2007; Ferguson 2001; Hamre and Pianta 2001). In addition, boys lose academic ground to girls from kindergarten through middle school (DiPrete and Jennings 2012; Entwisle et al. 2007; Willingham and Cole 1997), and some studies find that the gender gap in achievement and grades for black students emerges in middle school (Davis and Jordan 1994; Mickelson and Greene 2006). Therefore, black boys (and possibly white boys) lose academic ground well before they enter high school. In sum, our final objective examines whether the transition to high school results in a turning point, the maintenance of (dis)advantage, or the further accumulation of academic (dis)advantage for young men and women from different racial/ethnic backgrounds. For example, do boys’ declines in academic status mark a point of departure from their previous performance? Or, are their academic losses in high school a continuation of middle school disadvantage, making them fall even further behind their female counterparts? We also compare students’ academic performance during the grade progression following the transition to high school. Doing so allows us to assess whether white and black boys recover losses in academic status or whether the status quo is maintained during the ninth to tenth grade progression.

DATA AND METHODS

The Sample

We take advantage of the multi-cohort design of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) to examine young men’s and women’s academic performance between the seventh and tenth grades. Add Health is a nationally representative longitudinal study that began in 1994-95 (Wave I) with over 20,000 students in a sample of 80 U.S. high schools, each with one feeder school sampled proportional to its representation of the high school’s student body (Harris et al. 2003). Sample members were followed up a year later in 1996 (Wave II). Our analysis includes seventh, eighth, and ninth grade students who completed surveys in the two waves and who have a valid sample weight (n = 6,690). American Indians and Asian American/Pacific Islanders were excluded from our analysis due to small cell sizes. Finally, we only include students for whom there are no missing data on our dependent variable, Wave II self-reported GPA (seventh grade cohort = 1,820; eighth grade cohort = 1,850; ninth grade cohort = 2,200; Total N = 5,870). Thus, we exclude the small number of students who were not enrolled in school at Wave II, for reasons including dropout, expulsion, and pregnancy. Ancillary analyses in which we coded these students as having failing Wave II GPAs produce very similar results to the analyses in which we exclude this population of students.

We use multiple imputation to handle missing data on the independent variables. None of our variables has greater than 4 percent of cases missing. All models incorporate the appropriate sample weight and account for clustering within schools.

Sensitivity Tests Related to the Transition to High School

The transition from middle to high school occurs between the eighth and ninth grades, and research suggests that school climate, school composition, and the reconfiguration of relationships with teachers can place students at risk. Moreover, the match between middle and high school may differ among feeder patterns and place some students at greater risk than others. The 80 middle and high school pairs sampled by Add Health do not provide enough cases for a full analysis of feeder pattern or environmental change differences, but to the extent possible, we have conducted empirical tests to check robustness of our results across the mix of transition experiences. First, although most students change schools (and buildings) between eighth and ninth grades, we estimated models controlling for whether a student changed schools and estimated our models separately by whether students changed schools or not. Consistent with Weiss and Bearman (2007), we found no significant differences in the academic outcomes of students who did and did not change schools. Second, we tested the robustness of our results to differences in school systems’ feeder patterns, which shape the extent to which students transition to high school with eighth grade classmates and the similarity between middle and high schools in racial/ethnic composition. Although small sample sizes limit our ability to estimate effects of all combinations of racial/ethnic school composition and feeder patterns, we found that the pattern of our findings—that white and black male students experience greater academic risk during the transition than their female counterparts—is generally consistent.1

Variables

Dependent Variable

We focus on racial/ethnic and gender differences in students’ grade point averages (GPAs) surrounding the transition to high school. Academic grades are a signal of students’ performance (Pattison, Grodsky, and Muller 2013), and have consequences for postsecondary education and labor market outcomes.

We measure students’ grades with self-reports of the grades in four core academic subjects: math, science, social studies, and English. In Waves I and II, students reported whether they received an “A,” “B,” “C,” or “D/F” in these subjects, which we recoded to a four-point scale (1 = D/F, 2 = C; 3 = B; 4 = A). Overall GPA was computed by averaging students’ reported grades across these four subjects in a given academic year.

We use self-reported grades rather than transcript-reported grades because the latter are only available for high school. To test whether differences between students’ self-reported grades and transcript grades varied across race/ethnicity and gender, we compared students’ self-reported and transcript grades for those years we have both (grades 9-12). Consistent with other studies (Dornbusch et al. 1990; Langenkamp 2011), self-reported grades in Add Health are highly correlated with students’ actual grades. Sensitivity analyses indicated that, although students over-report their GPAs, the difference in the amount that students over-report their GPAs does not significantly differ across racial/ethnic and gender subgroups.

Independent Variables

Following our intersectional approach, this study highlights that advantage and power within schools is relational (Choo and Ferree 2010) by constructing a series of dummy variables for each racial/ethnic and gender subgroup: white male students and female students, black male students and female students, and Latino and Latina students. Whites are 72 percent of the sample, blacks 16 percent, and Latinos 12 percent; each racial/ethnic group is evenly split by gender. Although white female students—the group with the highest GPAs—serve as the reference category in the models, we also discuss differences between male and female students within the same racial/ethnic group. Our models with all students provide a more complete sense of the relative gender and race/ethnic differences in students’ performance across the transition. However, our substantive conclusions are the same when we estimate models separately by race/ethnicity or by gender.

We examine whether students’ relationships with teachers at Wave I explain the disparities we observe, relying on previous work (Crosnoe, Johnson, and Elder 2004) to develop this index (alpha = .62) of teacher bonding (mean = 3.74, SD = .8).2 We also estimate the degree to which differences in behavioral disengagement underlie academic disparities, relying on the Johnson, Crosnoe, and Elder (2001) operationalization of academic disengagement from Add Health indicators (alpha = .63, mean = .85, SD = .71).3 Because we are estimating the eighth grade cohort’s ninth grade GPAs (Wave II), we use students’ self-reports of teacher bonding and disengagement in eighth grade (Wave I), the year before the high school transition, in order to avoid time-order and bi-directionality issues. Our results are very consistent when we use Wave II measures of teacher bonding and disengagement.

We control for students’ parental education, the Add Health Picture Vocabulary Test (AH-PVT; mean = 100.92, SD = 14.39), family structure (.56 of the sample lives with both biological students), and whether the student was retained in their Wave I grade level at Wave II (5 percent of the sample). Estimates of coefficients including and excluding students who repeated their Wave I grade level yield identical substantive conclusions.

Analytic Plan

We use ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to predict the ninth grade GPAs of the eighth grade cohort by race/ethnic and gender subgroups. Unlike change score models that only estimate observed racial/ethnic and gender differences in GPA between two years without taking into account initial differences (Cohen et al. 2003), the lagged regression approach controls for group differences at time 1. This feature is especially important for the current study given large racial/ethnic and gender differences in GPA prior to the high school transition. Thus, controlling for students’ GPAs at time 1 (eighth grade) estimates differential academic risk of the transition (to ninth grade) net of racial/ethnic and gender differences in prior academic performance.

Using a nested modeling approach, the first model examines whether boys and girls from different racial/ethnic backgrounds earn lower ninth grade GPAs compared to white girls (reference), controlling for their previous academic performance and grade retention (Objective 1). In the second model, we control for students’ social background and verbal test scores. Our last two models examine whether social, behavioral, and academic factors provide insight into boys’ academic disadvantage during the high school transition.

The last model introduces an interaction term for eighth grade GPA with race/ethnicity and gender categories, which estimates whether students’ middle school academic standing conditions racial/ethnic and gender differences in academic performance during the transition to high school (Objective 2). Interacting GPA at time 1 with race/ethnicity and gender subgroups serves an important methodological function. Because regression toward the mean may occur when predicting dependent variables with a ceiling and floor (4 and 1 with GPA), we would expect the tendency for regression toward the mean to result in overestimated declines in GPA for girls—who have higher grades on average—and in underestimated declines for boys—who have lower grades on average. Thus, regression to the mean in this case would translate into conservative estimates of the degree to which young men’s academic grades fall behind those of young women. By interacting prior grades with gender-race groups, we can compare the time 2 GPAs of students at similar points in the GPA distribution at time 1, allowing us to compare the time 2 GPAs of students with an equal probability of regression toward the mean. Substantively, this interaction term allows us to examine relative differences at the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender. For example, a significant negative interaction for a given group would indicate a weaker correspondence between eighth and ninth grade GPA compared to the reference group, white female students. This pattern would suggest that the consistency in GPA across the transition varies across racial/ethnic and gender subgroups.

The final objective of this article is to contextualize the transition to high school by examining students’ GPAs during the grade progressions preceding (seventh-eighth grade) and following (ninth-tenth grade) the high school transition (Objective 3). We use a lagged regression approach identical to the one described above, which controls for Wave I GPA, to predict the eighth grade and tenth grade GPAs for the seventh and ninth grade cohorts respectively. To save space we show only final models that include teacher bonding and disengagement. All ancillary analyses are available upon request.

All models are estimated with fixed effects for middle school-high school pairs to remove the time-invariant observed and unobserved middle school-high school pair differences, and to compare within-pair differences in students’ grades (see Neumark and Rothstein 2006).

FINDINGS

To provide a preliminary picture of when average grades change, we first examine students’ self-reported GPAs in two consecutive years (Waves I and II) for the three cohorts. First, Table 1 shows little change in average GPA between Wave I and Wave II for the seventh and ninth grade cohorts (2.88 to 2.87 and 2.76 to 2.76, respectively). In contrast, the Wave I and Wave II GPAs for the eighth grade cohort show a decline from an average of 2.89 in eighth grade to an average of 2.75 in ninth grade, with this decline of over a tenth of a letter grade being statistically significant (p < .001). Overall, the descriptive statistics suggest that the transition to high school is a period of academic risk for students.

Table 1.

Weighted Summary Statistics for 7th, 8th, and 9th Grade Cohorts

| Variable Name | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||

| Self-reported GPA Wave II | ||

| 8th grade GPA (7th grade cohort) | 2.87 | .78 |

| 9th grade GPA (8th grade cohort) | 2.75 | .78 |

| 10th grade GPA (9th grade cohort) | 2.76 | .75 |

| Independent variables | ||

| Self-reported GPA Wave I | ||

| 7th grade GPA (7th grade cohort) | 2.88 | .77 |

| 8th grade GPA (8th grade cohort) | 2.89 | .75 |

| 9th grade GPA (9th grade cohort) | 2.76 | .77 |

| Race/ethnicity and gender | ||

| White female (ref) | .36 | |

| White male | .36 | |

| Black female | .08 | |

| Black male | .08 | |

| Latina | .06 | |

| Latino male | .06 | |

| Both biological parents | .56 | |

| Parents have college degree | .31 | |

| Add Health PVT score | 100.92 | 14.35 |

| Teacher bonding Wave I (alpha = .62) | 3.74 | .80 |

| Disengagement Wave I (alpha = .63) | .85 | .71 |

| Repeated Wave I grade | .05 | |

| N = 5,870 |

Data source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Harris et al. 2003).

Academic Performance During the Transition to High School

Table 2 shows results from OLS lagged regressions with fixed school effects that predict students’ ninth grade GPAs, controlling for their eighth grade GPAs and grade retention. As a benchmark, we estimate that white female students, who serve as our reference category, earn ninth grade GPAs that are about a tenth of a letter grade lower than their eighth grade GPAs. Our results, shown in Model 1, indicate that black female students and Latina students earn grades that are not statistically significantly different than those of white female students during the transition to high school, controlling for their eighth grade academic performance. However, our results indicate that white and black male students earn ninth grade GPAs that are about .12 and .16 significantly lower than those of white female students, controlling for eighth grade GPA. Black male students also earn significantly lower grades during the transition to high school compared to black female students, indicated by a bolded coefficient. Specifically, controlling for differences in eighth grade GPA, black male students earn a ninth grade GPA that is about .20 lower than black female students (i.e., .042 + .156), which translates into a little over three-quarters of a letter grade lower in one course, assuming that the average student takes four academic courses per year. We do not find a statistically significant gender difference in ninth grade GPA for Latino/a students. These results suggest that, overall, female students maintain their relative higher academic status during the transition, with gaps related to gender widening for white and black students.

Table 2.

Estimates from OLS Lagged Regression Predicting 9th Grade GPA

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity and gender (ref: white females) | |||

| White male | −.117* | −.126** | .011 |

| (.046) | (.044) | (.173) | |

| Black female | .042 | .099 | .708*** |

| (.069) | (.068) | (.212) | |

| Black male | -.156* | -.095 | .538* |

| (.065) | (.066) | (.246) | |

| Latina | −.095 | −.031 | .612 |

| (.078) | (.071) | (.320) | |

| Latino male | −.136 | −.080 | −.089 |

| (.072) | (.073) | (.317) | |

| 8th grade GPA | .658*** | .585*** | .644*** |

| (.031) | (.033) | (.039) | |

| Race/ethnicity and gender x 8th grade GPA | |||

| White male x 8th grade GPA | −.042 | ||

| (.054) | |||

| Black female x 8th grade GPA | −.215** | ||

| (.073) | |||

| Black male x 8th grade GPA | −.241** | ||

| (.087) | |||

| Latina x 8th grade GPA | −.222* | ||

| (.106) | |||

| Latino male x 8th grade GPA | .015 | ||

| (.113) | |||

| Repeated 8th grade | .298*** | .328*** | .331** |

| (.084) | (.083) | (.081) | |

| Both biological parents | .056 | .054 | |

| (.032) | (.032) | ||

| Parents have college degree | .110** | .104** | |

| (.035) | (.035) | ||

| Add Health PVT score | .006*** | .006*** | |

| (.001) | (.001) | ||

| Teacher bonding | .033 | .033 | |

| (.021) | (.021) | ||

| Disengagement | −.045 | −.047 | |

| (.028) | (.029) | ||

| Constant | .922* | .445 | .288 |

| (.174) | (.243) | (.228) | |

| N = 1,850 |

Notes: All models include school fixed effects. Bolded coefficients indicate statistically significant gender differences among black students. Standard errors in parentheses.

Data source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Harris et al. 2003).

* p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001 (two-tailed tests)

Family background, verbal ability, teacher bonding, student disengagement, and grade retention are introduced in Model 2. Net of these factors, white male students earn significantly lower grades than their white female counterparts during the high school transition. These controls reduce the negative coefficient for black male students in magnitude and render it nonsignificant. However, they do not explain the greater academic challenges black boys face during the transition to high school compared to black girls. Ancillary analyses indicate a statistically significant disadvantage of about .19 points for black young men in ninth grade GPA relative to black young women that persists even with the addition of control variables.

Race/Ethnicity and Gender and the Preservation of Academic Status

While white and black male students earn lower grades on average than female students during the transition to high school, students’ prior academic performance may condition who experiences relative downward academic mobility or protection. We investigate this possibility by introducing an interaction of race/ethnicity and gender with students’ eighth grade GPAs in Model 3. We observe statistically significant and negative interactions for black male students, black female students, and Latina students, suggesting that the strength of the association between eighth and ninth grade GPA is weaker for these students compared to white female students.

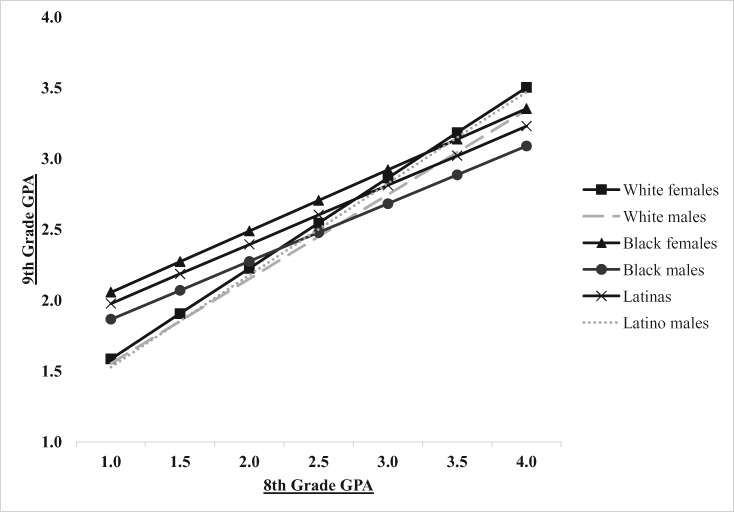

Figure 1 shows the relationship between eighth grade and ninth grade GPA by race/ethnicity and gender for students who are otherwise average on the control variables in Model 3 of Table 2. The graph shows dark lines for white female students (reference group) and black male students, black female students, and Latina students, for whom the relationship between eighth and ninth grade GPAs is statistically significantly weaker than this relationship for white female students.4 For example, an otherwise average white female student who earned a 3.5 (B+/A-) GPA in eighth grade would be expected to have a ninth grade GPA around 3.2 (B); a similar C (2.0) eighth grader would be expected to earn about a 2.2 GPA in ninth grade. The flatter lines for black male students, black female students, and Latina students indicate weaker associations between eighth and ninth grade GPAs. We see little difference in the expected ninth grade GPAs of otherwise average students who earned an overall eighth grade GPA of a 2.5, or a “C” average. This suggests that the transition to high school may result in some academic protection for black students and Latina students who were low-achieving in middle school.

Figure 1.

Predicted 9th Grade GPA by 8th Grade GPA and Race/Ethnicity and Gender

Note: Predicted values estimated from Model 3 of Table 2

Data source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Harris et al. 2003).

On the other end of the performance continuum, we see that the weaker association between eighth and ninth grade GPAs results in the lower relative performance for some of the highest eighth grade achievers. Our ancillary estimates show that higher-achieving black boys (but not black girls) earn ninth grade GPAs significantly lower than similarly achieving white girls.5 This suggests that black male students who were academically promising in eighth grade tend to experience downward mobility relative to white female students during the transition to high school. For example, otherwise average black male students who earned a 3.5 in eighth grade are expected to earn about one-third of a grade point lower in ninth grade (2.9) than otherwise similar white female students (3.2) who shared the same academic standing as black male students in eighth grade. Substantively, these results suggest that black male students with a “B” average in middle school are expected to drop to a “C” average in ninth grade, whereas their white female “B” average counterparts in middle school are expected to maintain a “B” average in high school. A similar pattern emerges among the very highest-achieving Latina students—particularly among those who earned 4.0 GPAs in eighth grade; however, cell sizes for this group are very small.

It is important to note that ancillary analyses indicate the relationship between eighth and ninth grade GPA does not significantly differ by gender for white and black students. In other words, regardless of middle school academic standing, white and black male students earn ninth grade overall GPAs that are about .12 and .20 lower on average than white and black female students, respectively. This consistent gap indicates that the relative group standing was preserved during the transition to high school.

Overall, our interaction terms representing the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender and academic status in eighth grade GPA indicate that the hierarchy is at least partially disrupted along racial/ethnic and gender lines during the transition to ninth grade. Effectively, status-group disparities are exacerbated by adjustments along racial/ethnic and gender dimensions to students’ locations within the academic hierarchy between the eighth and ninth grades.

The Transition to High School and the Adjacent Years

We are left with two lingering questions. First, were male students already losing academic ground relative to female students, or does the transition to high school represent a turning point? Second, do white and black male students experience stability or continued risk compared to female students during the ninth to tenth grade progression? We explore these issues in Table 3, which shows results from lagged OLS regressions with fixed school effects predicting students’ eighth and tenth grade GPAs.

Table 3.

Estimates from OLS Lagged Regressions Predicting 8th and 10th Grade GPA

| Variables | 8th Grade GPA | 10th Grade GPA |

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity and gender (ref: white females) | ||

| White male | −.102** | −.061 |

| (.036) | (.038) | |

| Black female | −.092 | .028 |

| (.084) | (.070) | |

| Black male | −.178* | (-.032) |

| (.072) | (.066) | |

| Latina | −.137 | −.083 |

| (.094) | (.095) | |

| Latino male | −.075 | −.188 |

| (.074) | (.116) | |

| Wave I GPA | .606*** | −.562*** |

| (.027) | (.028) | |

| Repeated grade at Wave I | .315* | −.130 |

| (.131) | (.076) | |

| Both biological parents | .095** | .035 |

| (.034) | (.036) | |

| Parents have college degree | .007 | .096** |

| (.036) | (.034) | |

| Add Health PVT score | .005** | .004* |

| (.001) | (.002) | |

| Teacher bonding | .005 | .038 |

| (.025) | (.026) | |

| Disengagement | −.077** | −.025 |

| (.029) | (.026) | |

| Constant | 1.170*** | 1.573* |

| (.187) | (.234) | |

| N | 1,820 | 2,200 |

Notes: All models include school fixed effects. Standard errors in parentheses.

Data source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Harris et al. 2003).

* p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001 (two-tailed tests)

As shown in the first column of Table 3, white and black male students earn eighth grade GPAs that are on average .10 and .18 significantly lower than those of white female students, net of seventh grade grades and other control variables.6 Assuming students are enrolled in four academic courses during the year, this translates into a little less than a one-half letter grade drop in one course for white male students and a little more than three-quarters of a letter grade drop in one course for black male students. We find no statistically significant differences between groups when the reference category is changed to directly compare the grades of black male and female students or Latino/a male and female students or when we include an interaction of race/ethnicity/gender with seventh grade GPA.

The second column in Table 3 estimates students’ tenth grade GPAs, controlling for their ninth grade GPAs. Net of ninth grade GPA and other controls, the results indicate no significant differences in tenth grade GPA between any racial/ethnic and gender group and white female students. We computed separately that white female students’ tenth grade GPAs are also not significantly different from their ninth grade GPAs. Thus, black and white male students appear to neither recover from the declines observed in prior years nor continue to lose academic ground relative to female students between ninth and tenth grade. Rather, after the transition to high school their freshman year academic status—and the inequality—is maintained.

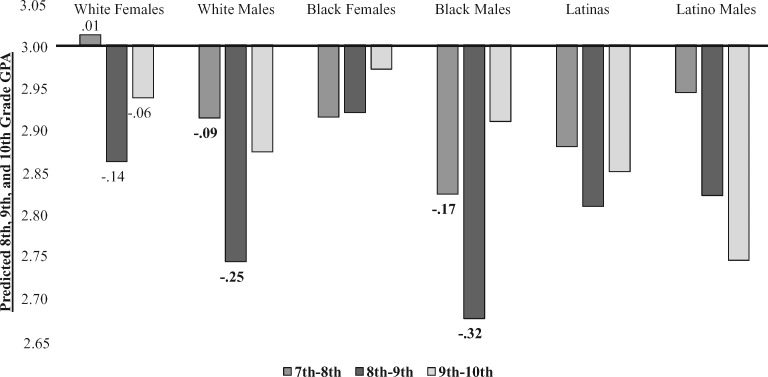

Figure 2 compares these findings for each grade level progression for a student with a B (3.0) average in the prior year, shown by race/ethnicity and gender groups. A 3.0 GPA is the minimum GPA requirement for admissions to many universities and to qualify for many college scholarships. We use the final models with full controls (Tables 2 and 3) for these estimates.7

Figure 2.

Predicted 8th, 9th, and 10th Grade GPA for Otherwise Average “B” Students

Notes: Predicted values estimated from regressions shown in Tables 2 and 3. Value labels shown for the reference group (white females) and groups whose expected GPAs are statistically significantly different than those of white females at the p < .05 level (two-tailed test).

Data source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Harris et al. 2003).

For each racial/ethnic and gender subgroup, the first bar represents their predicted eighth grade GPA for a “B” average seventh grader, indicating academic maintenance (at the 3.0 line) or the degree of loss between the seventh and eighth grades. Values beneath the bars for white female students, the reference group in the regressions, indicate their expected gain or loss for the following year. For the other groups, values are shown when the expected GPAs are statistically significantly different from those of white female students. For example, the predicted eighth grade GPA for an otherwise average black male student who earned a 3.0 in seventh grade is 2.83, representing a .17 decline in GPA from his 3.0 baseline in seventh grade. The second bar for black male students shows that the predicted ninth grade GPA for an otherwise average black male student who earned a 3.0 in eighth grade is 2.68, or .32 lower than the 3.0 he earned in eighth grade. Each of these losses is statistically significantly different from those of white female students. These estimates of racial/ethnic and gender gaps in academic performance at each year are conservative because we “reset” students’ grades at the start of each grade progression of interest by controlling for students’ GPA in the previous year.

Taken together, we draw two important insights about the intersection of race/ethnicity, gender, and academic performance from Tables 2 and 3 and the corresponding predicted values shown in Figure 2. First, with respect to absolute changes in GPA, white and black male students’ GPAs between the eighth and ninth grades are predicted to drop by over or about twice as much as they did between the seventh and eighth grades (−.25 compared to −.09 for white male students and −.17 compared to −.32 for black male students). However, the racial/ethnic and gender gaps in GPAs at each grade level progression are nearly identical in eighth and ninth grade. For instance, Figure 2 shows that the estimated gap in GPA between white female and black male students for the transition from seventh to eighth grade is about one-fifth of a grade point (3.01-2.83). There is a similar one-fifth of a grade point (2.86-2.68) gap after the transition from eighth grade to ninth grade. Similarly, the difference in white female and white male students’ GPAs is about one-tenth of a grade point in eighth grade (3.01-2.91) and one-tenth of a grade point in ninth grade (2.86-2.75). In sum, white and black male students fall behind female students by about the same increment both prior to and during the transition to high school. Thus, the transition to high school may be part of a longer trend of academic risk for them.

Second, white girls—despite a slight observed absolute decrease in grades at the middle to high school transition—tend to end their freshman year with a relative academic advantage over their male peers. We observe a repositioning of students’ relative academic standing that occurs along racial/ethnic and gender lines; white and black boys who began high school with the same GPA as white girls fall behind them by the end of their freshman year. Moreover, this status quo is maintained in their following sophomore year.

DISCUSSION

Our study advances scholarship on educational stratification by investigating how academic status at the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender is enhanced, preserved, or lost across the high school transition. Consistent with previous literature, we found that the transition to high school presents risk for all groups of students. However, our study underscores the importance of an intersectional approach that highlights the relative standing of subgroups who experience structural inequality very differently. We contextualized the high school transition within students’ broader academic experiences that have been affected by previous risky transitions, stratification processes, and ongoing developmental changes that shape racial/ethnic and gender differences throughout schooling. Our study documents evidence of a national trend in which white and black male students—especially higher-achieving young black men—suffer significant academic losses relative to their female counterparts at the high school starting gate, when grades and class rank are officially recorded and begin to accumulate.

Furthermore, we investigated whether the magnitude of their losses varied depending on middle school academic performance. High achieving young white women maintain their positions within the most coveted highest percentiles of the grade distribution. Strikingly, high-achieving young black men and the very highest achieving Latina students—both groups that are underrepresented in higher education—fall behind high-achieving white girls.

We can only speculate about why these higher-achieving students of color experience academic downward mobility relative to white girls. Evidence suggests that teachers’ perceptions of students’ cognitive and non-cognitive skills influence the grades teachers assign students (Kelly 2008) and that teachers may perceive students along stereotyped lines (e.g., Ferguson 2001; Morris 2006; Riegle-Crumb and Humphries 2012). Such stereotypes could be more pronounced at transition points when teachers and students are first meeting. Our findings suggest that students whose academic status is inconsistent with these stereotypes (e.g., high-performing black boys) may be most susceptible to academic declines during the transition. Consistent with this idea, a recent study finds that teachers evaluate high-achieving racial/ethnic minority students more negatively than high-achieving white students (Irizarry 2015). Students’ race/ethnicity and gender may also cue teachers’ assessments of students’ level of engagement and ability to learn (Mangels et al. 2012), and teachers’ perceptions of these non-cognitive skills affect the academic grades they assign (Kelly 2008). Potentially heightened stereotypes at this juncture may also escalate the risk of stereotype threat (Steele and Aronson 1995), in which students—especially higher-performing black students (Vars and Bowen 1998)—fear falling prey to stereotypes of underachievement.

Interestingly, we found some evidence that the middle to high school transition may result in a greater degree of academic protection for minority girls and black boys who were less academically successful in middle school, relative to similar white female students. This pattern is consistent with psychology studies suggesting that lower-status groups are held to lower standards for basic competency evaluations even as their ability is more strictly assessed than higher-status groups (Biernat and Kobrynowicz 1997; Foschi 1996). Future research should seek to identify possible mechanisms through which higher-performing black young men pay the highest price during the high school transition as well as further examine the possibility that lower-status, lower performing students are academically buffered during the transition.

We are also left wondering why white and black boys experience downward academic mobility compared to girls during the high school transition. Although boys’ higher levels of disengagement are a major source of academic gender gaps, our measure of behavioral disengagement did not mitigate white and black boys’ greater academic losses relative to their female peers. Moreover, ancillary analyses indicate that student reports of school expulsion, suspension, and risky behaviors do not explain their academic losses. This finding is consistent with another study that documented significant gender differences in GPAs among Chicago high school freshman, independent of prior achievement and student behaviors (Allensworth and Easton (2007). Previous research has also implicated boys’ less constructive relationships with teachers in academic gender gaps, yet our measure of teacher bonding did not explain the observed differences.

Whereas prior research has examined either students’ performance between the eighth and ninth grades only or did not consider race/ethnicity and gender, we argued and found that whether the transition to high school represents a turning point or one piece of a larger trend of increasing (dis)advantage depends on race/ethnicity and gender. Overall, our results suggest that that the transition to high school is part of a larger process—one in which students from groups that may have been academically marginalized since kindergarten experience the transition as another step in a process that sorts according to race/ethnicity and gender rather than prior academic performance as they mature through the life course. The academic declines that we observed among young white and black men in late middle school may be partly related to enduring impacts of the elementary to middle school transition (Eccles, Lord and Midgley 1991; Simmons and Blyth 1987), which cannot be examined with Add Health.

In contrast to young males, our results suggest that the high school transition may initiate academic risk for white girls. White girls with high GPAs may suffer in absolute terms as they confront the academic and social challenges associated with the transition. Or they may perform at the same level as they were in middle school but their grades decline slightly due to an increasing of academic standards in high school. In relative terms, the high achieving white girls get ahead of higher-achieving black boys and the highest achieving Latina students between eighth and ninth grades. Similar to white girls, the high school transition may initiate risk for black girls, who maintain their GPAs about as well as white girls during the high school transition and surrounding years. In addition, the greatest gender differences within racial groups appear to be among black students. The divergent academic outcomes between black and white girls and their male counterparts, who fell behind them prior to and during the transition to high school, underscores the importance of an intersectional approach.

Our results leave us with questions about how the transition to high school shapes Latino/a students’ academic grades, given the negative but non-significant coefficients for young Latino/a men and women. This could be a function of greater heterogeneity in the academic experiences of Latino students across the seventh-tenth grade period and an issue with smaller cell sizes. Future research should address how the high school transition shapes the grades of Latino/a boys and girls.

In situating the transition to high school within students’ broader educational careers, we also found that students maintain their relative academic positions between ninth and tenth grades. This suggests that changes in academic status during the transition to high school—when female students gain ground—is sustained in the second year of high school. Given research implicating boys’ lower high school GPAs in the gender gap in college application rates (Carbonaro, Ellison and Covay 2011), enrollment (Jacob 2002; Riegle-Crumb 2010), performance (Buchmann and DiPrete 2006; Massey and Probasco 2010), and completion (Conger and Long 2010), young men’s further accumulation of academic disadvantage during the transition to high school likely has long-term educational consequences. That the highest achieving black young men suffer the most suggests that an emphasis on class rank in college admissions may contribute to inequality in prestigious college and university attendance among the most meritorious of this underrepresented group. To the extent that these racial/ethnic and gender gaps are a function of stereotypes or other such processes that differentially target racial/ethnic and gender groups, relying on relative grades has the potential to reinforce discrimination.

Policies that promote positive interactions between teachers in receiving schools and students at points of school transitions may attenuate the trends that we have observed here. Vertical teaming, or the close communication and sharing of information between middle school and high school teachers about incoming freshman (Langenkamp 2010), may help mitigate males’ academic declines as they transition to high school. Interestingly, Roderick (2003) finds that middle school teachers held positive views of those males who later struggled and were deemed troublesome by their new high school teachers. More generally, policies that allow new students’ personal and individual strengths and reputations to travel with them to a new school may disrupt the tendency for their status group characteristics to serve as a basis of evaluation rather than individual accomplishments and achievements.

Our study was limited because we had to rely on student self-reports of GPA at two time points rather than being able to follow students all the way between seventh and tenth grade, or beyond. Growth curve modeling would have been a preferable method for examining students’ academic trajectories across the middle school to high school transition, but was not feasible with the available data. An ideal data set would provide both middle school and high school transcript data for a nationally representative cohort.

Despite these limitations, the current study highlights the value of studying transitions with an eye toward the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender. Furthermore, we gained important insights by broadening the window of focus from the middle school to high school transition to the adjacent years, when we could observe whether declines accumulated or were isolated. We argue that of greatest concern is the racial/ethnic and gender disparities that emerge during the transition to high school among the top performing middle school students: higher-achieving white girls in middle school get ahead while higher-achieving black boys fall behind by the end of the freshman year of high school. This shift results in a reorientation of relative academic performance along racial/ethnic and gender lines among students who are best positioned to succeed in high school and postsecondary education.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research uses data from the AHAA study, which was funded by a grant (R01 HD040428-02, Chandra Muller, PI) from the http://www.nichd.nih.gov/ National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and a grant (REC-0126167, Chandra Muller, PI, and Pedro Reyes, Co-PI) from the http://www.nsf.gov/ National Science Foundation. This research was also supported by Grant 5 R24 HD042849, Population Research Center, and Grant 5 T32 HD007081, Training Program in Population Studies, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD. Any opinions, findings, and recommendations presented here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the granting agencies.

Footnotes

We find one exception to the general observed pattern that white and black boys experience greater academic declines during the transition to high school than white and black girls. Ancillary results suggest that, unlike white boys who transition to high school with the majority of their middle school peers, white boys who transition to high school alone or with only a few of their middle school peers (about 17 percent) do not suffer greater academic declines relative to white girls. Although our cell sizes are relatively small, this finding is consistent with previous research suggesting that the transition to high school may create academic opportunity or protection for those students who were struggling in middle school.

Teacher bonding represents the mean of the responses to the following three questions asked in Wave I: (1) “The teachers at your school treat students fairly?”; (2) “How much do you feel your teachers care about you?”; and (3) “During the 94-95 school year, how often did you have trouble getting along with your teachers?” (reverse coded). The student answered “strongly agree,” “agree,” “neutral,” “disagree,” and “strongly disagree” to the first question and “not at all,” “very little,” “somewhat,” “quite a bit,” and “very much” to the other two questions.

This measure of disengagement is based on student responses to three questions in Wave I, including how often the student had trouble turning in homework, how often the student skipped class, and how often the student had trouble paying attention in class in the past school year.

The light grey lines represent subgroups for whom the relationship between eighth and ninth grades is not statistically significantly different relative to white girls.

Although small cell sizes are a concern when examining racial/ethnic and gender differences at the top and bottom of the grade distribution, a little under half of black males in the eighth grade cohort earned eighth grade average GPAs that were 2.75 or higher (n = 110). A 2.75 GPA or higher is above average among the black male eighth graders in our sample.

Ancillary analyses indicate that white female students do not experience a drop in GPA during the seventh to eighth grade transition.

Given the statistically significant interactions between eighth grade GPA and race/ethnicity in the models predicting ninth grade GPA (shown in Table 2), we consider this interaction in the predicted ninth GPAs of students shown in Figure 2. Ancillary analyses indicate that this interaction was not statistically significant in models predicting eighth and tenth grade GPA, and it therefore was not included in the models used to calculate predicted eighth and tenth grade GPAs.

REFERENCES

- Allensworth Elaine M., Easton John Q.. 2005. “The On-Track Indicator as a Predictor of High School Graduation.” Chicago, IL: Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Allensworth Elaine M., Easton John Q.. 2007. What Matters for Staying On-Track and Graduating in Chicago Public High Schools: A Close Look at Course Grades, Failures and Attendance in the Freshman Year. Chicago: Consortium on Chicago School Research. [Google Scholar]

- Barber Brian K., Olsen Joseph A.. 2004. “Assessing the Transitions to Middle and High School.” Journal of Adolescent Research 191:3-30. [Google Scholar]

- Barone Charles, Aquirre-Deandries Ana I., Trickett Edison J.. 1991. “Means-Ends Problem-Solving Skills, Life Stress, and Social Support as Mediators of Adjustment in the Normative Transition to High School.” American Journal of Community Psychology 192:207-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner Aprile D. 2011. “The Transition to High School: Current Knowledge, Future Directions.” Educational Psychology Review 233:299-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner Aprile D., Graham Sandra. 2009. “The Transition to High School as a Developmental Process Among Multiethnic Urban Youth.” Child Development 802:356-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernat Monica, Kobrynowicz Diane. 1997. “Gender- and Race-Based Standards of Competence: Lower Minimum Standards but Higher Ability Standards for Devalued Groups.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 723:544-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann Claudia, DiPrete Thomas A.. 2006. “The Growing Female Advantage in College Completion: The Role of Family Background and Academic Achievement.” American Sociological Review 714:515-41. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonaro William, Ellison Brandy J., Covay Elizabeth. 2011. “Gender Inequalities in the College Pipeline.” Social Science Research 401:120-35. [Google Scholar]

- Carter Prudence L. 2007. Keepin’ It Real: School Success Beyond Black and White. New York: Oxford Unversity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carter Stephen L. 1993. Reflections of an Affirmative Action Baby. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Choo Hae Y., Ferree Myra M.. 2010. “Practicing Intersectionality in Sociological Research: A Critical Analysis of Inclusions, Interactions, and Institutions in the Study of Inequalities.” Sociological Theory 282:129-49. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Jacob,, Cohen Patricia, West Stephen G., Aiken Leona S.. 2003. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Collins Patricia Hill. 2010. “The New Politics of Community.” American Sociological Review 751:7-30. [Google Scholar]

- Condron Dennis J. 2009. “Social Class, School, and Non-School Environments, and Black/White Inequalities in Children’s Learning.” American Sociological Review 745:683-708. [Google Scholar]

- Conger Dylan, Long Mark C.. 2010. “ Why are Men Falling Behind? Gender Gaps in College Performance and Persistence.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 6271:184-214. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw Kimberle. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 436:1241-99. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe Robert, Johnson Monica Kirkpatrick, Elder Glen H. Jr. 2004. “Intergenerational Bonding in School: The Behavioral and Contextual Correlates of Student-Teacher Relationships.” Sociology of Education 771:60. [Google Scholar]

- Davis James Earl, Jordan Will J.. 1994. “The Effects of School Context, Structure, and Experiences on African American Males in Middle and High School.” Journal of Negro Education 634:570-87. [Google Scholar]

- DiPrete Thomas A., Jennings Jennifer L.. 2012. “Social and Behavioral Skills and the Gender Gap in Early Educational Achievement.” Social Science Research 411:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch Sanford M., Ritter Philip L., Mont-Reynaud Randy, Chen Zeng-yin. 1990. “Family Decision Making and Academic Performance in a Diverse High School Population.” Journal of Adolescent Research 52:143-60. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles Jacquelynne S., Lord Sarah, Midgley Carol. 1991. “What are We Doing to Early Adolescents? The Impact of Educational Contexts on Early Adolescents.” American Journal of Education 994:521-42. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle Doris R., Alexander Karl L.. 1989. “Children’s Transition Into Full-Time Schooling: Black/White Comparisons.” Early Education and Development 12:85-104. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle Doris R., Alexander Karl L., Pallas Aaron M., Cadigan Doris. 1988. “A Social Psychological Model of the Schooling Process Over First Grade.” Social Psychology Quarterly 513:173-89. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle Doris R., Alexander Karl L., Olson Linda S.. 2007. “Early Schooling: The Handicap of Being Poor and Male.” Sociology of Education 802:114-38. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas George, Grobe Robert P., Sheehan Daniel, Shuan Yuan. 1990. “Cultural Resources and School Success: Gender, Ethnicity, and Poverty Groups within an Urban School District.” American Sociological Review 551:127-42. [Google Scholar]

- Felner Robert D., Primavera Judith, Cauce Ana M.. 1981. “The Impact of School Transitions: A Focus for Preventive Efforts.” American Journal of Community Psychology 94:449-59. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson Ann Arnett. 2001. Bad Boys Public Schools in the Making of Black Masculinity. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foschi Martha. 1996. “Double Standards in the Evaluation of Men and Women.” Social Psychology Quarterly 593:237-54. [Google Scholar]

- Gillock Karen L., Reyes Olga. 1996. “High School Transition-Related Changes in Urban Minority Students’ Academic Performance and Perceptions of Self and School Environment.” Journal of Community Psychology 243:245-61. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmann Joseph, Bar-Tal Daniel. 1982. “Stereotypic Perceptions of Teachers.” American Educational Research Journal 19:519-28. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre Bridget K., Pianta Robert C.. 2001. “Early Teacher–Child Relationships and the Trajectory of Children’s School Outcomes through Eighth Grade.” Child Development 722:625-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris Kathleen Mullan, Florey Francesca, Tabor Joyce, Bearman Peter S., Jones Jo, Udry Richard J.. 2003. “The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design.” Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina. Retrieved November 9, 2017 (www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design).

- Irizarry Yasmiyn. 2015. “ Selling Students Short: Racial Differences in Teachers’ Evaluations of High, Average, and Low Performing Students.” Social Science Research 520:522-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine Jacqueline. 1990. Blacks Students and School Failure: Policies, Practices, and Prescriptions. Westport CT: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Isakson Kristen, Jarvis Patricia. 1999. “ The Adjustment of Adolescents During the Transition into High School: A Short Term Longitudinal Study.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 281:1-26. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob Brian A. 2002. “Where the Boys Aren’t: Non-cognitive Skills, Returns to School and the Gender Gap in Higher Education.” Economics of Education Review 216:589-98. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson Jonathan, Olsen Cara, Rice Jennifer King, Sweetland Stephen, Ralph John. 2001. Educational Achievement and Black White Inequality. Statistical Analysis Report 2001-061 (July), National Center for Education Statistics, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Monica Kirkpatrick, Crosnoe Robert, Elder Glen H. Jr.. 2001. “Students’ Attachment and Academic Engagement: The Role of Race and Ethnicity.” Sociology of Education 744:318-40. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly Sean. 2008. “What Types of Students’ Effort Are Rewarded with High Marks?” Sociology of Education 811:32-52. [Google Scholar]

- Kerckhoff Alan C. 1993. Diverging Pathways: Social Structure and Career Deflections. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langenkamp Amy G. 2010. “Academic Vulnerability and Resilience during the Transition to High School: The Role of Social Relationships and District Context.” Sociology of Education 831:1-19. [Google Scholar]

- Langenkamp Amy G. 2011. “ Effects of Educational Transitions on Students’ Academic Trajectory: A Life Course Perspective.” Sociological Perspectives 544:497-520. [Google Scholar]

- Laub John H., Sampson Robert J.. 1993. “Turning Points in the Life Course: Why Change Matters to the Study of Crime.” Criminology 313:301-25. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas Samuel R. 2001. “Effectively Maintained Inequality: Education Transitions, Track Mobility, and Social Background Effects.” American Journal of Sociology 1066:1642-90. [Google Scholar]

- Mangels Jennifer A., Good Catherine, Whiteman Ronald C., Maniscalco Brian, Dweck Carol S.. 2012. “Emotion Blocks the Path to Learning under Stereotype Threat.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 72:230-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., Probasco LiErin. 2010. “Divergent Streams: Race-Gender Achievement Gaps at Selective Colleges and Universities.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 701:219-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall Leslie. 2001. Complex Inequality: Gender, Class and Race in the New Economy. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson Roslyn Arlin. 2003. “When Are Racial Disparities in Education the Result of Racial Discrimination? A Social Science Perspective.” Teachers College Record 1056:1052-86. [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson Roslyn Arlin, Greene Anthony D.. 2006. “ Connecting Pieces of the Puzzle: Gender Differences in Black Middle School Students’ Achievement.” Journal of Negro Education 751:34-48. [Google Scholar]

- Morris Edward W. 2006. An Unexpected Minority: White Kids in an Urban School. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neumark David, Rothstein Donna. 2006. “School-to-Career Programs and Transitions to Employment and Higher Education.” Economics of Education Review 254:374-93. [Google Scholar]

- Noguera Pedro A. 2003. “The Trouble with Black Boys: The Role and Influence of Environmental and Cultural Factors on the Academic Performance of African American Males.” Urban Education 384:431-59. [Google Scholar]

- Nord Christine, Roey Shep, Perkins Robert, Lyons Marsha, Lemanski Nita, Tamir Yael, Brown Janis, Schuknecht Jaston, Herrold. Kathleen. 2011. “The Nation’s Report Card: America’s High School Graduates (NCES 2011-462).” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Pallas Aaron M. 2003. “Educational Transitions, Trajectories, and Pathways” Pp. 165-84 in Handbook of the Life Course, edited by Mortimer Jeylan T., Shanahan Michael J.. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Pattison Evangeleen, Grodsky Eric, Muller Chandra. 2013. “Is the Sky Falling? Grade Inflation and the Signaling Power of Grades.” Educational Researcher 425:259-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips Meredith, Crouse James, Ralph John. 1998. “Does the Black-White Test Score Gap Widen after Children Enter School?” Pp. 229-72 in The Black-White Test Score Gap, edited by Jencks Christopher, Phillips Meredith. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz Pamela Anne. 2001. “The Silencing of Latino Student ‘Voice’: Puerto Rican and Mexican Narratives in Eighth Grade and High School.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 323:326-49. [Google Scholar]

- Riegle-Crumb Catherine. 2010. “More Girls Go to College: Exploring the Social and Academic Factors Behind the Female Postsecondary Advantage Among Hispanic and White Students.” Research in Higher Education 516:573-93. [Google Scholar]

- Riegle-Crumb Catherine, Humphries Melissa. 2012. “Exploring Bias in Math Teachers’ Perceptions of Students’ Ability by Gender and Race/Ethnicity.” Gender & Society 262:290-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roderick Melissa. 2003. “What’s Happening to the Boys? Early High School Experiences and School Outcomes Among African American Male Adolescents in Chicago.” Urban Education 385:538-607. [Google Scholar]

- Roderick Melissa, Camburn Eric. 1999. “Risk and Recovery from Course Failure in the Early Years of High School.” American Educational Research Journal 362:303-43. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller Kathryn S. 1999. “Effects of Feeder Patterns on Students’ Transition to High School.” Sociology of Education 724:216-33. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider Barbara, Swanson Christopher B., Riegle-Crumb Catherine. 1997. “ Opportunities For Learning: Course Sequences and Positional Advantages.” Social Psychology of Education 21:25-53. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman Edward, Lawrence Aber J., Allen LaRue, French Sabine Elizabeth. 1996. “The Impact of the Transition to High School on the Self-System and Perceived Social Context of Poor Urban Youth.” American Journal of Community Psychology 244:489-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons Roberta G., Blyth Dale A.. 1987. Moving into Adolescence: The Impact of Pubertal Change and School Context. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Steele Claude M., Aronson Joshua. 1995. “Stereotype Threat and the Intellectual Test Performance of African Americans.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 695:797-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vars Frederick E., Bowen William G.. 1998. “Scholastic Aptitude Test Scores, Race, and Academic Performance in Selective Colleges and Universities” Pp. 457-79 in The Black-White Test Score Gap, edited by Jencks Christopher, Phillips Meredith. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss Christopher C., Bearman Peter S.. 2007. “Fresh Starts: Reinvestigating the Effects of the Transition to High School on Student Outcomes.” American Journal of Education 1133:395-422. [Google Scholar]

- Willingham Warren W., Cole Nancy S.. 1997. Gender and Fair Assessment. New York: Routledge Press. [Google Scholar]