Abstract

Objective

Adolescent fertility rates are high in Kenya, and increase the risks of unintended repeat pregnancies and maternal and infant morbidity and mortality. Our objective was to examine knowledge, practices, and influences surrounding contraceptive access and use among Kenyan postpartum adolescents.

Study Design

We conducted a mixed methods study (surveys and focus group discussions) with postpartum adolescents and family planning (FP) providers at two maternal and child health clinics in Kenya.

Main Outcome Measures

Four focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with postpartum adolescents (stratified by age and site), and two FGDs were conducted with FP providers (stratified by site). Transcripts were analyzed for prevalent themes. The participants also completed individual surveys that were analyzed for contraceptive knowledge.

Results

Adolescent contraceptive decision-making and use were shaped by social norms of adolescent sexual behaviour. Lack of FP knowledge, community misinformation, and insufficient counselling and time with providers all contributed to adolescent concerns about FP. However, as adolescents transitioned to motherhood, they felt more encouraged to use FP and had increased awareness of FP benefits.

Conclusion

Both postpartum adolescents and providers felt delivery of FP services could be improved if providers had better training and counselling tools.

Keywords: postpartum, adolescent, family planning, contraception, Kenya

Introduction

Worldwide, 40% of pregnancies are unintended, with nearly 90% occurring in developing countries [1]. Unmet need for family planning (FP) is high in these settings, despite strong desires to delay or prevent future pregnancies [2]. Reducing unmet need during the postpartum period is an effective strategy to promote birth spacing, and reduce maternal and infant morbidity and mortality [3]. Yet, modern contraceptive prevalence rates (mCPRs) are low (34%) among postpartum women [2].

In Kenya, low (37%) mCPR among adolescents, coupled with early sexual debut and high fertility rates, result in 40% of adolescents childbearing before age 20 [4]. Postpartum adolescents face similar challenges using FP encountered by adult postpartum women, namely concerns about compatibility with breastfeeding and misconceptions about fertility. However, adolescents also have unique barriers to accessing and using contraception. While Kenyan laws promote adolescent access to FP, adolescent embarrassment, provider bias or personal beliefs, and inability to access services create challenges for adolescents to receive FP [5]. Furthermore, preferences and needs among postpartum adolescents specifically duration of coverage, perceived tolerance for long-acting, reversible contraception (LARC), dosing schedules, and ability to navigate side effects may differ from their adult counterparts [6].

Consequences of disproportionally high unmet need for FP among postpartum adolescents contributes to substantial disease burden for young mothers and their infants. Adolescents who become pregnant have a markedly higher risk of adverse maternal and infant outcomes, including mortality, low birth weight, and prematurity [7, 8, 9]. They may experience other adverse social and economic outcomes, including stigma, lower educational attainment, early marriage, and reduced earning potential, which have negative generational impacts [10, 11, 12]. Despite these risks, and the need to reduce unintended pregnancies, data on postpartum adolescent contraceptive behaviours are lacking. We conducted a mixed methods study among postpartum Kenyan adolescents and FP providers to identify determinants of postpartum adolescent contraceptive desire, method choice, and use.

Methods

Design, Setting and Population

This study was conducted between October and November 2013 at two rural public maternal and child health (MCH) clinics in Kisumu and Siaya County, Kenya. Postpartum adolescents attending infant immunization visits were recruited by MCH clinic and study staff to complete a survey and participate in focus group discussions (FGDs). Purposeful sampling was used to recruit participants based on eligibility criteria. Adolescents were asked to return to the clinic for a FGD scheduled within 2 weeks of study enrollment and completion of the survey. Adolescents (defined as age 14-21) were eligible if they were HIV-negative, postpartum, and attending six-week infant immunization visits. Four adolescent FGDs were conducted, stratified by site and age (14-18 or 19-21 years). Health care providers eligible for study participation (employed at MCH clinics or hospitals, provided any FP services, and ≥18 years) were referred by hospital administrators to study staff for participation in a survey and FGD. Two FGDs with providers were conducted, one at each site, and occurred on the same day as they were enrolled in the study and completed the survey.

Adolescent surveys were administered by study staff and included assessment of adolescents' contraceptive knowledge, misconceptions, and; a few questions were also asked about influences on FP use and intentions to use FP. Provider surveys developed by the study team were self-administered and assessed providers' experiences delivering contraceptives, knowledge, and current FP practice. Adolescents and providers were asked a series of contraceptive knowledge questions about each FP method (7-16 questions per method), and a few questions (3 for providers, 8 for adolescents) about general pregnancy prevention. FGDs were led by a female Kenyan behavioral scientist trained in qualitative methods using a semi-structured guide developed by the study team to explore community, health care worker, and personal facilitators and barriers to FP. FGDs and surveys were facilitated in participants' preferred language, Dholuo for adolescent FGDs, and English for provider FGDs. FGDs were ∼1.5 hours and audio recorded, transcribed, and translated into English (if needed) by the same facilitator.

Study materials were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Washington (UW) and Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi (KNH/UoN) Ethics and Research Committee (ERC) before study initiation. All participants provided written informed consent.

Analysis

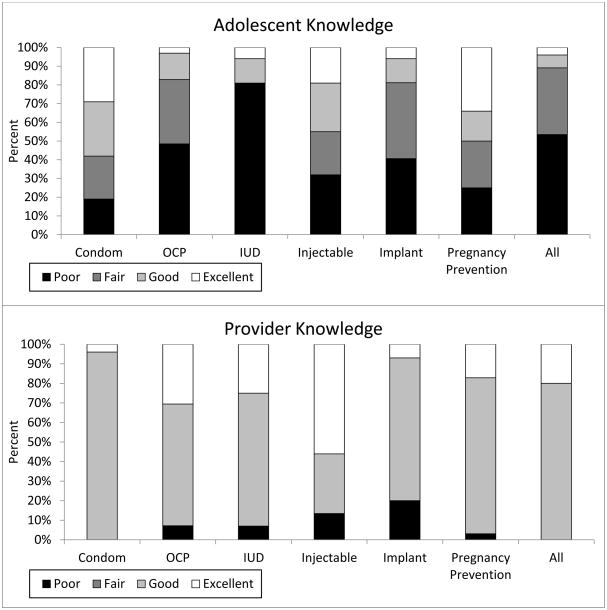

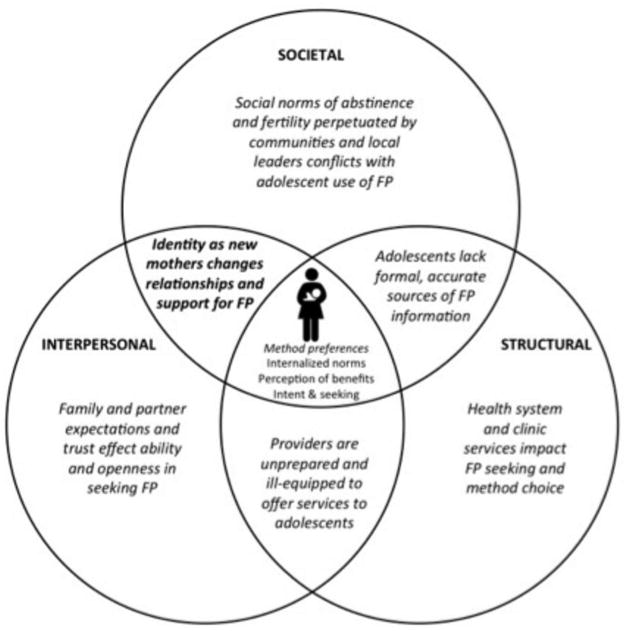

We used a grounded theory approach to advance understanding about determinants of FP among postpartum adolescents employing constant comparative analysis [13]. Data were managed in Atlas.ti 7.5.11. We used open-coding and an iterative approach to develop a codebook. Two researchers independently coded transcripts, and compared codes to ensure inter-coder agreement. Thematic analysis produced a modified socio-ecological model with individual, interpersonal, societal, and structural domains (Figure 1) [14]. A priori secondary content analysis also compared themes for younger (14-18 years) and older (19-21 years) adolescents, but results were pooled since no major differences between groups were detected. Stata 14.0 was used to summarize survey data. The proportions of correct contraceptive knowledge responses were categorized as poor (≤55%), fair (>55-70%), good (>70-85%), and excellent (>85%) by each contraceptive method, and overall. Surveys and FGDs asked women about birth control pills, but did not distinguish between progestin-only vs. combined pills unless specified; we have abbreviated this as oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) throughout.

Figure 1.

Model of influences on postpartum adolescent family planning (FP) method access and choice.

Results

A total of 32 postpartum adolescents (n=16 age 14-18, n=16 age 19-21) and 28 providers participated in the study. Six adolescents completed surveys at recruitment but did not return for scheduled FGDs. Median provider age was 36 (interquartile range [IQR] 31-47), and median number of years providing FP was 5 (IQR 3-10). Overall qualitative themes are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Themes and quotes from adolescents and providers.

| Theme | Sub-theme | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent FP use conflicts with social norms of abstinence and fertility | Relationships affect FP use | Even the mother-in-law wants grandchildren, so if you go for the one [FP method] for 12 years or for 5 years, and the mother-in-law, if you give birth to a girl…she will say “I want a boy, I want a boy”, so that will prevent you [from using FP]. (Site A, age 14-18) Condoms, sometimes boyfriend doesn't allow…even using they will not agree, so if he refuses, injection you can hide once in a while and you go and get. (Site A, age 14-18) |

| Motherhood shifts social identities and support for FP | Birth spacing benefits | [FP] makes us have good spacing of children and also makes us to educate [children] well. (Site A, age 14-18) You cannot give birth to kids close to one another, because if you get pregnant immediately it's going to force you to remove this one from breastfeeding and then you have another one… sometimes you are going to work and you can't ask for permission every year [from working] that you are pregnant. (Site A, age 14-18) |

| Adolescents lack formal, accurate sources of FP information | Need for reliable sources of information | Doctors should be free with teachers to tell the students in school… if you feel you cannot abstain, its good to go for family planning. (Site A, age 14-18) |

| Concealability, reversibility, and fear of side effects guide individual FP preferences | Dosing interval | I will forget, like the date of the injection will just go because sometimes I am in school doing exams and the date will just go like that… (Site B, age 19-21) |

| Misconceptions | [Adolescents] believe that if [IUD] is inserted it can go up to the chest. That is a very big issue…also a baby can be born with the IUD in the hand. (Site B, Provider) | |

| Providers are unprepared and ill-equipped to offer services to adolescents | Method effectiveness | I don't know the updates but in the learning, the failure rates of almost all [FP methods] is 0.1, 1.1%. Failure rates are equal. (Site A, Provider) |

| Limited counselling | When I went I was told nothing; they only gave me the drug. (Site B, age 14-18) | |

| Misconceptions | The virgins…are not coming for family planning methods (laugh) but if they come I wouldn't go on breaking their virginity because I want to put [in] an IUD. (Site A, Provider) | |

| Lack of continued training | Also lack of skills…not all of us can insert IUD and maybe let's say she [qualified provider] is on leave…clients are either being referred or chose another method. (Site B, Provider) | |

| Clinic services impact FP seeking and method choice | Method stock-outs | When I went to the hospital I asked… that doctor told me that now it's [injectable] not there but the one that is there are the pills, that is what you can get. (Site A, age 19-21) |

Adolescent use of FP conflicts with social norms of abstinence and fertility

In FGDs, adolescent girls described immense community pressure to remain abstinent until marriage and refrain from using contraception. Community leaders, families, and society were reported to disapprove of premarital sex. Traditional healers and religious figures were discouraging of adolescent FP use and perpetuated misinformation about FP. Parents were also unsupportive of their daughters using FP and adolescents feared their parents' reactions if they asked for information or assistance, preventing them from talking to parents about FP.

Somebody saw that you had gone [for FP], you know he is going to tell your parents, you know if you are still at your parent's you [use FP] secretly… [because] after your parents have known [you have gone] it will be known that… my child is [sexually active and promiscuous]. (Site A, age 14-18)

Adolescents were interested in preventing pregnancy, but were afraid of openly seeking FP, due to beliefs that FP was inappropriate prior to demonstrating fertility. They also internalized social norms discouraging sexual activities before marriage or childbearing, and feared perceptions of the community that utilizing FP services was planning for, and enjoying, sexual activities, which caused adolescents to discretely seek FP services. Social pressures from partners, mothers-in-law, or other family to produce children (particularly boys) inhibited many adolescents from seeking FP services and perpetuated barriers to seek FP after marriage. Some adolescents described partners who questioned their fidelity if they sought FP, or forbade, sabotaged, or withheld funds to purchase FP.

Motherhood shifts social identities and support for FP

After becoming mothers, adolescents described a societal shift in acceptance of FP use and community support for birth limiting; having short interpregnancy intervals was cause for embarrassment. Adolescents also said some partners became supportive of FP after they had a child.

The person that I am staying with can allow me to go for family planning. I can go because it's like he is planning for our future well. (Site B, age 19-21)

Some adolescents acknowledged educational benefits of using FP, and discussed a shift in support from parents to use FP to help them stay in school after having a baby and alleviate familial burden to provide further childcare.

… they [parents] have a kid in school and the next day this child has given birth to a child, so she [the mother] is going to tell her, “go for family planning… I cannot take you to school and I also feed your child… if one day you finish school and you have gotten your work, you can leave [FP].” (Site A, age 14-18)

With additional support to use FP after motherhood, adolescents became more motivated to seek FP to delay future pregnancies and achieve personal and family goals. They had newfound appreciation for the responsibility of providing for and raising healthy children, economic and social impacts of pregnancy, and ability of FP to help achieve desired family size. Based on survey responses, most (97%) adolescents planned to use FP, which may be directly related to recognition of these FP benefits.

Adolescents lack formal, accurate sources of FP information

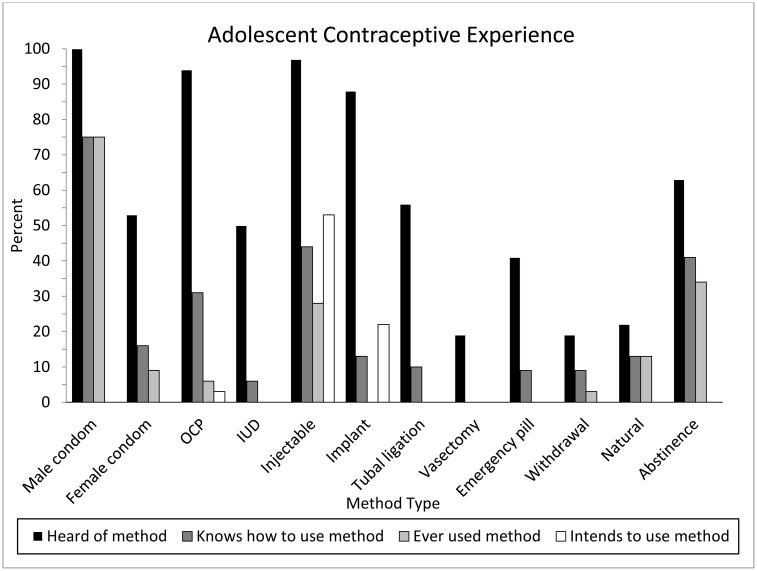

Overall, survey results suggest adolescents lacked FP knowledge and received little formal education on methods. Knowledge about LARC (including implants and intrauterine contraceptive devices [IUDs]) was particularly low (Figure 2). Adolescents were familiar with other FP methods (100% condoms, 97% injectables, 94% OCPs, 88% implants) but only 50% were familiar with IUDs (Figure 3). The most common FP methods/strategies adolescents ever used were condoms (75%), abstinence (34%), and injectables (28%); none had ever used a LARC method.

Figure 2.

Knowledge of FP methods and pregnancy prevention, by method and overall.

Proportions of correct contraceptive knowledge responses to survey questions: poor (≤55%), fair(>55-70%), good (>70-85%), and excellent (>85%) by each contraceptive method, and overall.

a) Number of adolescent survey questions for each category: condoms 9, OCPs 10, IUDs 15,injectables 8, implants 9, pregnancy prevention 8.

b) Number of provider survey questions for each category: condoms 7, OCPs 10, IUDs 16, injectables 10, implants 7, pregnancy prevention 3.

Figure 3.

Adolescent familiarity and experience with contraceptive methods.

Unlike other FP methods, adolescents were more knowledgeable about condoms: 58% had good or excellent knowledge (Table 2). Despite knowledge that condoms could prevent both HIV transmission and pregnancy, the primary reason for use was HIV prevention. FGD data indicated adolescents believed condoms were most appropriate for couples with a known HIV-positive partner, rather than when partner status was unknown or a couple was concordant negative.

You use condoms after you have gone and all of you know your status, so if one person has [HIV] and the other person doesn't have [HIV] and you still want to go on, you can use the condom but if you all have [HIV] you can work without anything and if all of you don't have [HIV], you can do it without anything. (Site A, age 14-18)

Table 2.

Adolescent and provider responses to specific survey questions.

| Questions (correct answer) | Adolescent Correct N (%) | Provider Correct N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condom | |||

| Correct use | It is OK to use same condom more than once. (False) | 26 (81) | - |

| When using condom, leave space at the tip. (True) | 18 (58) | - | |

| Pregnancy | Pregnancy occurs <1% of the time with using condoms as instructed. | - | 7 (24) |

| HIV/STI risk | Condoms prevent STIs. (True) | 27 (84) | - |

| Condoms are 100% effective at preventing STIs. (False) | - | 15 (50) | |

| Condoms prevent HIV. (True) | 27 (84) | - | |

| Condoms are the most effective way to prevent HIV. (True) | - | 27 (90) | |

| OCP | |||

| General | OCPs are effective even if a woman misses taking 2-3 days in a row. | 17 (53) | 30 (100) |

| Women should take a break from OCPs every couple of years. (False) | 17 (53) | 26 (87) | |

| Combined OCPs are safe to prescribe immediately postpartum. (False) | - | 20 (69) | |

| After a woman stops OCPs, she is unable to conceive for 2 months. (False) | 16 (50) | 24 (80) | |

| HIV/STI risk | OCPs prevent HIV. (False) | 23 (72) | - |

| OCPs increase chance of getting HIV. (False) | 18 (58) | 25 (89) | |

| OCPs increase HIV transmission to others. (False) | 18 (58) | 20 (71) | |

| IUD | |||

| General use | A woman <20 years old can use IUD, even if she has never had children. (True) | 4 (13) | 21 (70) |

| Only married women should use IUD. (False) | 13 (41) | 28 (93) | |

| IUDs are safe to use immediately postpartum. (True) | - | 25 (86) | |

| IUDs cause infertility. (False) | 8 (25) | 29 (97) | |

| Side effects | IUDs can move around in the body. (False)* | 8 (25) | - |

| IUDs can dislodge during sex. (False) | 10 (31) | 26 (87) | |

| A woman's partner can feel IUD during sex. (False) | 7 (22) | 20 (67) | |

| HIV/STI risk | A woman with a history of an STI can have an IUD. (True) | 4 (13) | 17 (57) |

| IUDs prevent HIV. (False) | 21 (66) | - | |

| IUDs increase chance of getting HIV. (False) | 16 (50) | 18 (60) | |

| IUDs increase HIV transmission to others. (False) | 14 (44) | 21 (70) | |

| IUDs are safe to use in women with HIV. (True) | - | 19 (63) | |

| Injectable | |||

| General use | Women should receive shot every 3 months. (True) | 30 (94) | 28 (93) |

| Injection can interfere with breastfeeding. (False) | - | 12 (41) | |

| Side effects | A woman's period may stop if she is receiving shot. (True) | 21 (68) | 28 (93) |

| Pregnancy risk | If a woman is late receiving her shot, she is still protected against pregnancy for 3 months. (False) | 16 (50) | 24 (80) |

| HIV/STI risk | Injections prevent HIV. (False) | 25 (78) | - |

| Injection increases chance of getting HIV. (False)** | 20 (63) | 25 (83) | |

| Injection increases HIV transmission to others. (False) | 19 (59) | 26 (87) | |

| Implant | |||

| General use | A woman can see implant under skin. (False) | 5 (16) | 8 (27) |

| Implants cannot be removed early. (False) | 14 (44) | - | |

| Fertility returns immediately after removal of implant. (True) | - | 22 (73) | |

| Side effects | Implant can move around body. (False)* | 10 (31) | - |

| Implant can change menstrual bleeding pattern. (True) | 14 (44) | 28 (93) | |

| Pregnancy | Implant can prevent pregnancy for up to 3 years. (True) | 10 (31) | 25 (83) |

| HIV/STI risk | Implants prevent STIs. (False) | 21 (66) | - |

| Implants prevent HIV. (False) | 24 (75) | - | |

| Implant increases chance of getting HIV. (False) | 18 (56) | 24 (80) | |

| Implant increases HIV transmission to others. (False) | 21 (66) | 25 (83) | |

| Pregnancy Prevention | After giving birth, a woman can get pregnant before her next period. (True) | 15 (47) | 26 (87) |

| Urinating after sex prevents pregnancy. (False) | 25 (78) | - | |

| Contraception is more risky to a woman's health than pregnancy. (False) | 17 (53) | 30 (100) | |

| A woman who is still breastfeeding cannot get pregnant. (False) | 23 (72) | 25 (86) |

Some case studies suggest that in rare instances implants have migrated from their insertion point.

Some data suggest injectable contraception may increase HIV risk.

Adolescents described wanting better FP education, and supportive partners and community members who understand FP benefits during FGDs. While partners and family members influenced adolescent decisions, few adolescents trusted them as sources of FP information, which was corroborated in both surveys and FGDs. Older adolescents sought FP information from peers who shared their own experiences using FP, but also described negative interactions, such as feeling judged or fearing a breach in confidentiality. Younger adolescents did not describe sources of FP information they actively sought. Peers and community were cited by adolescents in both age groups and providers as sources of many FP myths, leading to general distrust of information from these sources. For example, a commonly perpetuated myth, FP use prior to childbearing (or an extended time) results in difficulty conceiving or infertility, was believed by the majority of adolescents, and even a few providers. Schools were not perceived to be good sources of information; teachers rarely discussed FP, and education efforts were focused only on abstinence. Surveys suggested most adolescents in both age groups (75%) trusted FP information from providers, but wanted more in-depth counselling.

What can prevent me from coming [for FP], if I've not been taught about family planning. But if I can get a doctor who can sit with me…and teach me that it is done like this and this and this, then I think I can do it. But because…[of] a lot of issues I hear outside, it can prevent me. (Site A, age 14-18)

Concealability, reversibility, and fear of side effects guide individual FP preferences

Among postpartum adolescents who planned to use FP, survey results indicated over half (53%) intended to use injectables, followed by implants (22%) and OCPs (3%); none intended to use IUDs or condoms. During FGDs, postpartum adolescents described preferences for concealable methods, with a short return to fertility, and infrequent dosing. Providers echoed need for adolescent access to discrete methods during FGDs, and offered methods (usually injectables) to allow FP use without family or partner knowledge; however, they also encouraged disclosure and partner involvement in decision-making. In adolescent surveys, method effectiveness, ease of administration, and infrequent dosing were cited as most important FP characteristics (28%, 19%, and 19%, respectively); concealability was less commonly reported (3%). The misconception that injectables had a shorter return to fertility than other methods was common among adolescents, and contributed to higher acceptance of injectables. Among adolescents intending to use implants, long-term coverage was cited as an important consideration in method selection.

Fear of side effects and difficulty using specific methods were commonly reported during both adolescent FGDs and surveys and inhibited use. Adolescents were concerned about disruption of menses (i.e., amenorrhea, spotting, or heavier menses) with FP use, and preferred to maintain a regular menses to reaffirm they were not pregnant. They were also concerned about weight changes, pain, and discomfort, including: LARC insertion pain, headaches or abdominal pain with hormonal methods, and discomfort with condoms. Some adolescents were aware of side effects prior to initiating FP, while others became aware of them only after they were experienced. Some erroneously believed pain was related to ‘unnatural’ suppression of menses. Method specific logistical barriers to using FP included injectable dosing for girls in school, planning and partner cooperation for per coital use of condoms, and daily dosing for OCPs. Adolescents also described OCPs as feeling reminiscent of receiving medical treatment and thought they could be mistaken for treating stigmatized diseases like HIV. LARC methods conferred concerns about access to, and cost of, removing LARC if they experienced discomfort or undesirable bleeding changes, or decided to become pregnant. Most adolescents were unaware LARC can be removed at any time.

Providers are unprepared and ill-equipped to offer services to adolescents

Providers' personal beliefs about adolescent FP use and inadequate training affected their ability to meet adolescents' FP needs. On-going FP training was infrequent, and only offered to selected providers, typically nurses primarily tasked with delivering FP services. The limited FP training providers in MCH or maternity wards received compromised their ability to offer accurate information and comprehensive, integrated FP services. For example, many were unaware failure rates vary by method and neglected to discuss failure rates during FP counselling. Providers also said they were overworked and had competing priorities, limiting their ability to offer tailored counselling. At times, adolescents tired of waiting for services went home without receiving FP, or sought private providers to avoid long wait times. Some providers acknowledged delivering limited FP counselling and discussing short-term methods that could be administered quickly when the queue was long, but said they expanded to a broader range of FP methods (including LARC) when they were not busy.

If I am only one health provider in a dispensary or clinic, I have overwhelming work… I will not provide those methods that take a lot of my time… I will not tell the client about IUD and maybe implants. So I will counsel the client on pills, Depo, and condom so that they have that option only, so that I will clear the queue so maybe some other time… I will give [more counseling]… (Site B, Provider)

Providers reported spending more time on FP counselling than adolescents recalled receiving, with a few adolescents recalling virtually no counselling at all. Adolescents said counselling focused on method dosing requirements, and discussion of side effects was uncommon unless specifically requested.

Providers' focus on short-term methods perpetuated adolescents' lack of knowledge of LARC. Usually, providers only offered short-term methods they were confident administering. Provider experience with LARC was low based on survey results; 18% had placed >10 IUDs and 34% had placed >10 implants. Providers referred adolescents if they were unable to provide LARC, but referrals were infrequent and the process was not transparent, leading to confusion about when and where to receive services. Therefore, adolescents who initially asked about LARC often chose to accept readily available short-term methods.

Provider misconceptions about FP and personal beliefs about adolescent sexual activity sometimes led to adolescents being denied FP services. Providers frequently referenced FP as suitable for ‘mothers’, excluding nulliparous adolescents from FP conversations. Adolescents and providers described inappropriate deferrals and refusals to provide FP based on postpartum status, parity, age, and provider beliefs about appropriate methods for adolescents. Misconceptions about adolescent IUD use were particularly prevalent in FGDs, including beliefs that IUDs are inappropriate during physical maturation or prior to sexual debut. Both providers and adolescents mentioned that negative provider attitudes towards adolescents seeking FP resulted in poor counselling quality and diminished adolescent motivation to seek FP. One adolescent related requesting LARC, but encountered resistance to receiving a method due to the provider's personal beliefs.

[The provider] asked me “why?” And I told him that I want to go to college that's when I can get another child. And then he asked me, “Can you not abstain till the end of those ten years?” (Site A, age 19-21)

Adolescents and providers also cited provider characteristics as important in determining adolescents' comfort seeking FP services. Both adolescents and providers mentioned that many women were uncomfortable with male providers inserting IUDs and older ‘motherly’ providers were perceived as judgmental which may deter seeking FP.

Structural factors impact FP seeking and method choice

Access to clinics, FP cost, and method supply were structural barriers to FP for adolescents. Some adolescents expressed difficulty getting to public clinics or seeking FP services on non-child health days. In contrast, others easily accessed clinics and even described traveling to distant clinics to prevent negative perceptions about their sexual activity or HIV status. Overall, providers perceived clinic distance as a more important barrier for FP access and management than adolescents. While FP cost and availability did not meaningfully affect seeking FP services, they were determinants of access to the full range of methods. Adolescents were typically offered (and selected) free or low cost methods that were readily available. In some cases, adolescents purchased injectables from private pharmacies and returned to clinics for administration.

Discussion

Adolescents' FP opinions were influenced by community social norms and interpersonal relationships with partners, family, and providers. We found adolescents internalized cultural influences and social norms, which discouraged FP use before marriage and/or childbearing, but also received FP encouragement and support following motherhood. As a result, adolescents experienced a substantial identity shift during their transition to motherhood, which affected their acceptance of, and desire to use, FP. Although previous studies have also found that cultural and religious opposition to adolescent contraceptive use contributes to lack of support to make decisions to use FP [15, 16, 17], to our knowledge, the shift in support for FP after motherhood has not been previously described. Targeted approaches supporting postpartum adolescents to use FP have high potential for success due to familial and community support for FP use for young mothers. Furthermore, there are unique opportunities to assess and meet postpartum adolescent needs by incorporating them into non-stigmatized care that includes FP while they are already engaged in the health care system during antenatal, postnatal, and infant care [18].

However, despite support for FP following childbirth, adolescents described lacking quality FP knowledge, and had concerns about future fertility and menstrual changes as side effects of FP both before and after demonstrating fertility. These findings are supported by other studies among African adolescents and women [15, 17, 19, 20]. Adolescents were most familiar with injectables, and method familiarity, consistent availability, concealability, and infrequent dosing schedules led most adolescents intending to use injectables. Interestingly, adolescents in our study preferred a rapid return to fertility and were unaware injectables have a longer return to fertility following discontinuation. While LARC methods had desirable characteristics such as concealability and dosing schedules; safety and removal concerns, method misconceptions, inappropriate exclusions, limited LARC counselling, and lack of knowledge about differences in effectiveness between methods led to low uptake of LARC.

Adolescents wanting to avoid pregnancy could benefit from user-independent LARC, which have been shown to be safe and highly effective methods for adolescent populations (including both nulliparous and postpartum), and are recommended by WHO and Kenyan guidelines [21, 22]. Implant use in Kenya has surged to 10%, second only to injectables [4]; similar to our findings on intentions to use. A Kenyan study offering information and free FP services to adolescents led to high (24%) implant acceptance, and significantly lower discontinuation rates and fewer unintended pregnancies compared to short-term methods [23]. Although improving FP knowledge and dispelling myths are critical to help adolescents make informed decisions; knowledge alone has not been sufficient to increase contraceptive use among adolescent girls [24], and efforts to improve FP counselling experiences and social norms are also required. Strategies to support providers to offer high-quality FP counseling and services on the full range of methods to adolescents, including LARC, are necessary to meet adolescent FP needs [5].

In addition, adolescents need better counselling and education about condoms. Despite elevated risks of HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among young women, condoms were unpopular among adolescents in our study and were used for HIV prevention not pregnancy prevention, which supports others' findings [17, 20]. Lack of desire to use condoms may stem from adolescent girls' inability to negotiate consistent condom use with partners [6, 25], or low perceptions of HIV/STI risk. We also found adolescents may have misconceptions about the need to use condoms in concordant negative relationships, or with a partner of unknown status, underscoring the need for improved counselling on condom use.

Providers' attitudes and perceptions about adolescent FP use, and FP knowledge and training, play an important role in supporting, or hindering, adolescent use. Inappropriate FP exclusions for adolescent use based on age, parity, and marital status were common in our study and others [16, 26], making it challenging for adolescents to seek or receive FP. One Kenyan study found over half of FP providers applied minimum age restrictions and refused to offer some contraceptive methods, particularly LARC, to adolescents [27]. Provider language and framing of FP as suitable for mothers, coupled with limited time for FP counselling, may also dissuade adolescents from accessing FP in indirect ways [17]. Adolescents, often inexperienced FP users, may require more provider assistance and counselling time to make value-laden, complex FP decisions [28]. National policies and international guidelines seeking to reduce unintended pregnancies outline many adolescent-friendly strategies, but are not sufficiently supported with trained personnel, funding, or adequate time and space to offer tailored services for adolescents [29, 16].

Our study had several strengths. The mixed methods design allowed us to quantify postpartum adolescent FP knowledge and experience, include adolescent and provider perspectives, and gain insight into how relationships contributed to promoting and discouraging FP use. Our focus on postpartum adolescents allowed us to explore adolescent FP use and decision-making before and after motherhood, and identify determinants of FP that are distinct from adult postpartum women. By including provider perspectives we gained insight in their attitudes towards, and challenges with, providing adolescents FP services. Our study was also subject to some limitations. Participants were from western Kenya, and results may not be generalizable to other settings. Adolescents were recruited from infant immunization clinics and already engaged in health care, so may be more likely to utilize FP [30]. Additionally, hospital administrators identified FP providers; however, there was substantial variation in the frequency and types of FP services provided.

Our study suggests postpartum adolescents are interested and ready to use FP. They appreciate the demands of childrearing, recognize FP benefits, and have community and family support to use FP. To increase LARC acceptance among adolescents, counselling must also address valid method-specific issues like implant or IUD removal and cost [31]. Providers can play a critical role in supporting adolescent FP; however, interventions to improve adolescent FP use involving providers should strive to reduce provider burden while simultaneously increasing skills. Strategies featuring provider training to deliver comprehensive counselling could include decision aids, audiovisuals, and/or telephone follow-up [32], and incorporate novel approaches to on-going hands-on training. While some youth-centered interventions in low- and middle-income countries have shown promise, many lack robust evaluation, ascertainment of long-term impact, or strategies that are tailored to different adolescent groups (i.e., postpartum, in-school, out-of-school) [33, 34]. Future efforts supporting adolescent FP to reduce unintended pregnancies among this vulnerable population should incorporate adolescents and communities during intervention design and implementation stages, and include these elements in their approach [33, 35] to maximize potential for sustainable impact.

Highlights.

Adolescent family planning conflicts with social norms of abstinence and fertility

Motherhood shifts social identities and support for family planning

Concealability, reversibility, and side effects guide individual FP preferences

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sedgh G, Singh S, Hussain R. Intended and unintended pregnancies worldwide in 2012 and recent trends. Stud Fam Plann. 2014;45(3):301–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00393.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasha O, Goudar SS, Patel A, Garces A, Esamai F, Chomba E, et al. Postpartum contraceptive use and unmet need for family planning in five low-income countries. Reprod Health. 2015;12(Suppl 2):S11. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-12-S2-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, Faundes A, Glasier A, Innis J. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1810–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DHS (Demographic Health Services) Program. [accessed 4 August 2016];Statcompiler. 2014 http://beta.statcompiler.com/

- 5.Chandra-Mouli V, Parameshwar P, Parry M, Lane C, Hainsworth G, Wong S, et al. A never-before opportunity to strengthen investment and action on adolescent contraception, and what we must do to make full use of it. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s12978-017-0347-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daley AM. What influences adolescents' contraceptive decision-making? A meta-ethnography J Pediatr Nurs. 2014;29(6):614–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO (World Health Organization) [accessed 4 August 2016];Aolescent pregnancy. 2016 http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/maternal/adolescent_pregnancy/en/

- 8.Darroch JE, Woog V, Bankole A, Ashford LS. Adding it up: costs and benefits of meeting the contraceptive needs of adolescents. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magadi M. Poor pregnancy outcomes among adolescents in South Nyanza region of Kenya. Afr J Reprod Health. 2006;10(1):26–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fall CHD, Sachdev HS, Osmond C, Restrepo-Mendez MC, Victora C, Martorell R, et al. Association between maternal age at childbirth and child and adult outcomes in the offspring: a prospective study in five low-income and middle-income (COHORTS Collaboration) Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(7):e366–77. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00038-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timaeus IM, Moultrie TA. Teenage childbearing and educational attainment in South Africa. Stud Fam Plann. 2015;46(2):143–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2015.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Early motherhood and subsequent life outcomes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(2):151–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd. Los Angeles, Calif: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godia PM, Olenja JM, Hofman JJ, Van den Broek N. Young people's perception of sexual and reproductive health services in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:172. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godia PM, Olenja JM, Lavussa JA, Quinney D, Hofman JJ, Van den Broek N. Sexual reproductive health service provision to young people in Kenya; health service providers' experiences. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:476. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochako R, Mbondo M, Aloo S, Kaimenyi S, Thompson R, Kays M. Barriers to modern contraceptive methods uptake among young women in Kenya: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:118. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1483-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO. Programming Strategies for Postpartum Family Planning. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rominski SD, SK Morhe E, Maya E, Manu A, Dalton VK. Comparing women's contraceptive preferences with their choices in 5 urban family planning clinics in Ghana. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5(1):65–74. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williamson LM, Parkes A, Wight D, Petticrew M, Hart GJ. Limits to modern contraceptive use among young women in developing countries: a systematic review of qualitative research. Reprod Health. 2009;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. 5th. Geneva: WHO; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kenya MOPHS (Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation), Division of Reproductive Health. 2010 National Family Planning Guidelines for Service Providers. Nairobi: Kenya MOPHS; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hubacher D, Olawo A, Manduku C, Kiarie J, Chen PL. (2012) Preventing unintended pregnancy among young women in Kenya: prospective cohort study to offer contraceptive implants. Contraception. 2012;86(5):511–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Somba MJ, Mbonile M, Obure J, Mahande MJ. Sexual behaviour, contraceptive knowledge and use among female undergraduates' students of Muhimbili and Dar es Salaam Universities, Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:94. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS) Global Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2013. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nalwadda G, Mirembe F, Tumwesigye NM, Byamugisha J, Faxelid E. Constraints and prospects for contraceptive service provision to young people in Uganda: providers' perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:220. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tumlinson K, Okigbo CC, Speizer IS. Provider barriers to family planning access in urban Kenya. Contraception. 2015;92(2):143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaccard J, Levitz N. Counseling adolescents about contraception: towards the development of an evidence-based protocol for contraceptive counselors. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(4 Suppl):S6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greifinger R, Ramsey M. Making Your Health Services Youth-Friendly. Washington, DC: Population Services International (PSI); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Do M, Hotchkiss D. Relationships between antenatal and postnatal care and post-partum modern contraceptive use: evidence from population surveys in Kenya and Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christofield M, Lacoste M. Accessible contraceptive implant removal services: an essential element of quality service delivery and scale-up. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4(3):366–372. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopez LM, Grey TW, Tolley EE, Chen M. Brief educational strategies for improving contraception use in young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD012025. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012025.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gottschalk LB, Ortayli N. Interventions to improve adolescents' contraceptive behaviors in low-and middle-income countries: a review of the evidence base. Contraception. 2014;90(3):211–25. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.WHO. Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!) Geneva: WHO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chandra-Mouli V, McCarraher DR, Phillips SJ, Williamson NE, Hainsworth G. Contraception for adolescents in low and middle income countries: needs, barriers, and access. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]