Abstract

Objective

To examine whether history of traumatic brain injury (TBI) is associated with more rapid progression from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to Alzheimer disease (AD).

Method

Data from 2,719 subjects with MCI were obtained from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center. TBI was categorized based on presence (TBI+) or absence (TBI−) of reported TBI with loss of consciousness (LOC) without chronic deficit occurring >1 year prior to diagnosis of MCI. Survival analyses were used to determine if a history of TBI predicted progression from MCI to AD up to 8 years. Random regression models were used to examine whether TBI history also predicted rate of decline on the Clinical Dementia Rating scale Sum of Boxes score (CDR-SB) among subjects who progress to AD.

Results

Across 8 years, TBI history was not significantly associated with progression from MCI to a diagnosis of AD in unadjusted (HR=0.80; 95% CI=0.63–1.01; p=.06) and adjusted (p=.15) models. Similarly, a history of TBI was a non-significant predictor for rate of decline on CDR-SB among subjects who progressed to AD (b=0.15, p=.38). MCI was, however, diagnosed a mean of 2.6 years earlier (p<.001) in TBI+ subjects compared to the TBI− group.

Conclusions

A history of TBI with LOC was not associated with progression from MCI to AD, but was linked to an earlier age of MCI diagnosis. These findings add to a growing literature suggesting that TBI might reduce the threshold for onset of MCI and certain neurodegenerative conditions, but appears unrelated to progression from MCI to AD.

Keywords: Head Injury, Cognitive Decline, Mild Cognitive Impairment, Dementia, Risk

A history of traumatic brain injury (TBI) may be a risk factor for the later development of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer Disease (AD) (Barnes et al., 2014; Fleminger, Oliver, Lovestone, Rabe-Hesketh, & Giora, 2003; Plassman et al., 2000; Sivanandam & Thakur, 2012). While a majority of the evidence stems from moderate-to-severe TBI, not all studies have found a link (Crane et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2015), and evidence of the potential association between mild TBI and later life cognitive decline remains less clear (Gardner et al., 2014). Furthermore, the potential mechanism(s) underlying an association between TBI and the later development of AD remains poorly understood.

Classic AD pathology involves the accumulation of tau-related neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) and amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques (Nelson, Braak, & Markesbery, 2009). When the pathological burden surpasses a threshold, cognitive/behavioral impairments clinically manifest. It is well-known that TBI commonly affects frontal and temporal lobe structures/networks via axonal and neuronal injury and results in a cascade of abnormal neurochemical processes (Gentry, Godersky, & Thompson, 1988; Giza & Hovda, 2014; Messé et al., 2011; Zappalà, Thiebaut de Schotten, & Eslinger, 2012). TBI may play a role in a neurodegenerative process by disrupting long-term neuronal functioning and connections, as some evidence indicates tau and Aβ accumulate as a result of TBI (Abisambra & Scheff, 2014; Ikonomovic et al., 2004; Johnson, Stewart, & Smith, 2010; Johnson, Stewart, & Smith, 2012; Johnson, Stewart, & Smith, 2013).

Since TBI may contribute to the accumulation of AD-related pathology, it is possible TBI could hasten clinical manifestation of later cognitive disorders. The earliest threshold prior to AD onset where AD-related pathological changes occur and subtle neurobehavioral deficits manifest is known as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (Petersen et al., 1999). MCI is often a transitional stage between normal aging and AD, and represents a period when neuropsychological impairment develops but everyday functioning is relatively preserved (Petersen, 2001). Approximately 10–15% of individuals with MCI go on to develop AD each year (Farias, Mungas, Reed, Harvey, & DeCarli, 2009). However, rates of progression vary widely in MCI, with some individuals advancing to AD within a year of MCI diagnosis, others many years later, some not progressing to any dementia, and a subgroup which shows a variable course (Petersen et al., 1999; Koepsell & Monsell, 2012; Tyas et al., 2007).

Because of variation in the clinical trajectory of MCI, much attention has been focused on the identification of factors related to progression from MCI to AD. Recent studies have conducted retrospective analyses of large samples of subjects with MCI as well as frontotemporal dementia, and found that a remote (>1 year prior to evaluation) history of TBI with LOC was associated with an approximately 2 year earlier diagnosis of each condition (LoBue et al., 2016a; LoBue et al., 2016b). This supports the notion that TBI may accelerate the accumulation of pathological burden in AD and related conditions, resulting in a reduced threshold for clinical manifestation. Since greater AD-related pathology has been associated with accelerated aging and greater cognitive impairment (Rodrigue et al., 2012), TBI may be a risk factor for progressing from MCI to AD and influence the course of decline, though this is currently unknown. The aim of this investigation was to examine whether a history of TBI was associated with more rapid progression from MCI to AD.

Method

This study involved a retrospective analysis of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Uniform Data Set (UDS) between September, 2005 and June, 2015. NACC has maintained a combined database since September, 2005 from 34 past and present National Institute of Aging (NIA) - funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADC) across the U.S (Morris et al., 2006), and contains clinical and sociodemographic information on healthy controls and subjects diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Clinical diagnosis was determined by ADC clinicians using established guidelines along with a review of all available information, which typically included neuropsychological testing, neurological exam results, medical history, and psychosocial background. A clinical diagnosis of MCI was made if there was a cognitive complaint, evidence of cognitive impairment in one or more domains, everyday functioning was relatively intact, and criteria for dementia were not met (Petersen & Morris, 2005). Additionally, if cognitive impairment included memory, the MCI diagnosis was further defined as amnestic type. The diagnosis of AD was made according to NINCDS/ADRDA criteria and defined as probable or possible AD (McKhann et al., 1984), while normal cognition was defined as a lack of neurocognitive impairment and failure to meet established clinical criteria of MCI, dementia, or other neurodegenerative conditions. NACC’s data collection procedures were approved by institutional review boards at each participating ADC. Selection criteria for this study included subjects who were a) over age 50, b) diagnosed with MCI at their initial visit to an Alzheimer’s Disease Center (ADC), c) completed ≥2 visits, and d) remained MCI, reverted to normal cognition, or progressed to a diagnosis of AD during follow-up.

The NACC database contains three patient/informant-reported questions related to TBI: a) whether subjects had ever sustained a TBI resulting in <5 minutes loss of consciousness (mLOC), b) ≥5 mLOC, and c) if there was a chronic deficit/dysfunction as a result of the injury. Each question is coded as absent, recent/active (defined as occurring within 1 year of visit or currently requiring treatment), remote/inactive (defined as occurring >1 year of visit and either having recovered from the injury or no treatment is currently underway), or unknown. Age at TBI or time since injury is not collected by NACC. Therefore, the only way to examine the effect of a history of remote TBI was to select those subjects who were coded as having a TBI occurring >1 year prior to the initial visit (i.e., remote/inactive). Further, subjects reporting a history of TBI leading to a chronic deficit or a recent/active TBI at the initial visit or anytime thereafter were excluded in an attempt to remove the effect of acute cognitive decline directly attributable to a recent TBI. As such, this study only included individuals who reported a history of TBI with LOC and no chronic deficits that occurred more than one year prior to the initial visit, or an absence of TBI history.

Measures

The following variables were included in analyses because of their known link with later cognitive decline: age of MCI diagnosis, sex, race, education, family history of dementia (i.e., a first-degree relative with a dementia diagnosis), apolipoprotein E-e4 (Apoe4) status, number of years smoking cigarettes, and history of depression (defined as consulting a clinician, being prescribed medication, or receiving a diagnosis related to depressed mood > 2 years prior) and alcohol abuse. Because vascular risk factors have also been associated with increased dementia risk, the Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging and Incidence of Dementia (CAIDE) risk score was calculated by totaling weighted scores for age, education, sex, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, and presence/absence of hypercholesterolemia (i.e. reflective of total cholestrol ≥ 6.5 mmol/L), and examined (Exalto et al., 2014). Furthermore, NACC subjects are evaluated using the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale, which is a reliable and valid semi-structured clinician interview rating scale for cognitive decline in 6 functional domains: memory, orientation, judgement and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care (Cedarbaum et al., 2013). Severity of impairment is rated for each domain as no impairment (0), questionable impairment (0.5), mild (1), moderate (2), and severe (3), with the exception of the personal care domain which excludes a rating for questionable impairment. A Sum of Boxes score (CDR-SB) is computed by totaling severity ratings for all 6 domains, and was analyzed due to its sensitivity for staging dementia severity.

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square, t-tests, nonparametric tests, and ANCOVAs were used where appropriate to compare the TBI+ and TBI− groups on sociodemographic, clinical, and Apoe4 information at time of MCI diagnosis. Background variables that significantly differed between the groups were entered as covariates when assessing clinical characteristics at time of MCI diagnosis. Only subjects with complete baseline data were included for analysis.

Survival analyses were utilized to examine the ability of a history of TBI to predict progression from MCI to AD up to 8 years, first in an unadjusted model (Kaplan Meier analysis), and second (Cox proportional hazard model), adjusted for age at MCI diagnosis, sex, race, education, family history of dementia, number of Apoe4 alleles, number of years smoking cigarettes, CAIDE risk score, and histories of depression and alcohol abuse. Covariates remained in the model if p<.15. Time to progression was calculated by taking the difference between the ages for diagnosis of MCI and AD. For subjects who did not progress to AD (i.e., remain MCI or revert to normal cognition), the time from age of MCI diagnosis to the last follow-up visit was used instead. Time estimates were limited to 8 years because of the limited number of subjects with progression/follow-up visits beyond this timeframe.

Random regression models were used to assess whether a history of TBI was associated with decline in CDR-SB scores over time among those who progressed to AD. Subject drop-out is common in the NACC dataset, calculated to exceed 80% beyond 6 visits in our sample. As a result, two models were used to examine the best fit to the data. In model 1, CDR-SB scores were assessed across five visits. In model 2 the 6th visit was added. Each model included history of TBI and the aforementioned covariates as fixed effects predictors. Time between study visits (number of days from initial visit) was modeled as a random intercept and slope. Also, since subject drop-out after two visits would restrict variability in change of CDR-SB scores, only individuals who completed a minimum of 3 visits were examined.

Analyses initially included amnestic and non-amnestic MCI types combined in order to determine the possible magnitude of the effect TBI may have on the general progression from MCI to AD. Afterward, analyses were performed again only for subjects diagnosed with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCIamn) to assess whether associations remained, because these subjects are the most likely among MCI cases to develop AD (Vos et al., 2013). All analyses were conducted using IBM© SPSS Statistics V22 (IBM Corp, SPSS Statistics V22, Armonk, NY, 2013) with significance set at p<.05.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of MCI Groups

A total of 2,719 subjects diagnosed with MCI met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Among these, 248 reported a history of TBI with LOC (TBI+ MCIamn n = 197) occurring more than one year prior to the initial visit and 2,471 subjects reported an absence of TBI (TBI− MCIamn n=2,038). Baseline characteristics for the combined MCI group can be found in Table 1. The TBI+ and TBI− MCI groups did not differ by race, education, CAIDE risk scores, number of years smoking cigarettes, family history of dementia, or Apoe4 status. The MCI groups did differ significantly in terms of sex distribution and histories of depression and alcohol abuse (p’s<.001). Compared to the TBI+ group, the TBI− group had a larger proportion of females (51% vs 33%) and fewer subjects with a history of depression (18% vs 31%) and alcohol abuse (3% vs 10%).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of sample selection from NACC’s UDS dataset. MCI = mild cognitive impairment; AD = Alzheimer disease; F-U = follow up visits; TBI = traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Medical History of Subjects With and Without a History of TBI

| TBI+ (n=248) |

TBI− (n=2471) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age of MCI diagnosis, M (SD)* | 71.68 (9.05) | 74.33 (8.50) |

| Education, M (SD) | 15.17 (3.36) | 15.20 (3.21) |

| Female*, n (%) | 82 (33) | 1260 (51) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 203 (82) | 1913 (78) |

| African American | 25 (10) | 323 (13) |

| Hispanic | 14 (6) | 158 (6) |

| Other, Non-white | 6 (2) | 70 (3) |

| Family History of Dementia, n (%) | 143 (58) | 1280 (56) |

| Apoe4 alleles, n (%) | ||

| 0 alleles | 141 (57) | 1388 (56) |

| 1 allele | 90 (36) | 883 (36) |

| 2 alleles | 17 (7) | 200 (8) |

| Cigarette Smokers, n (%) | 51 | 46 |

| # of Years Smoking Cigarettes, M (SD) | 22.54 (15.23) | 22.75 (14.97) |

| History of Depression*, n (%) | 77 (31) | 448 (18) |

| History of Alcohol Abuse*, n (%) | 25 (10) | 68 (3) |

| History of Other Substance Abuse, n (%) | 6 (2) | 12 (1) |

| CAIDE score, M (SD) | 6.84 (1.78) | 6.67 (1.81) |

| CDR–SB score, M (SD) | 1.26 (1.02) | 1.30 (1.08) |

Note. n = 2,719.

p <.05.

MCI = mild cognitive impairment; TBI = traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness; Other, Non-white = Asian/Pacific Islander/Native American background; CDR–SB = Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes; CAIDE = the Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging and Incidence of Dementia risk score; Apoe4 = apolipoprotein E-e4.

Clinical Characteristics of MCI Groups

At time of MCI diagnosis, CDR-SB scores were nearly equivalent for the TBI+ (range=0–4.5) and TBI− groups (range=0–8; p=.16). However, MCI was diagnosed on average 2.6 years earlier in the TBI+ group (M=71.68) relative to the TBI− group (M=74.33; p<.001), controlling for sex and psychiatric comorbidities. Examining only subjects with MCIamn continued to show that CDR-SB scores did not significantly differ between those with and without a history of TBI (TBI+ MCIamn M=1.34; vs TBI− MCIamn M=1.37; p=.41), but that diagnosis of MCI was earlier for the TBI+ group (MCIamn M=72.06) compared to the TBI− group (MCIamn M=74.71; p<.001).

Progression from MCI to AD

The median duration of follow-up was 4 years (interquartile range=2–5 years). A total of 1,016 subjects out of 2,719 progressed from MCI to a diagnosis of AD over a course of 8 years, of whom 870 had amnestic MCI at baseline and 73 had a history of TBI (TBI+ MCIamn n=67). Annual rates of progression from MCI to AD were 8% and 10% for the TBI+ and TBI− groups, respectively, during 5 years of follow-up, and similar rates were found among MCIamn subjects.

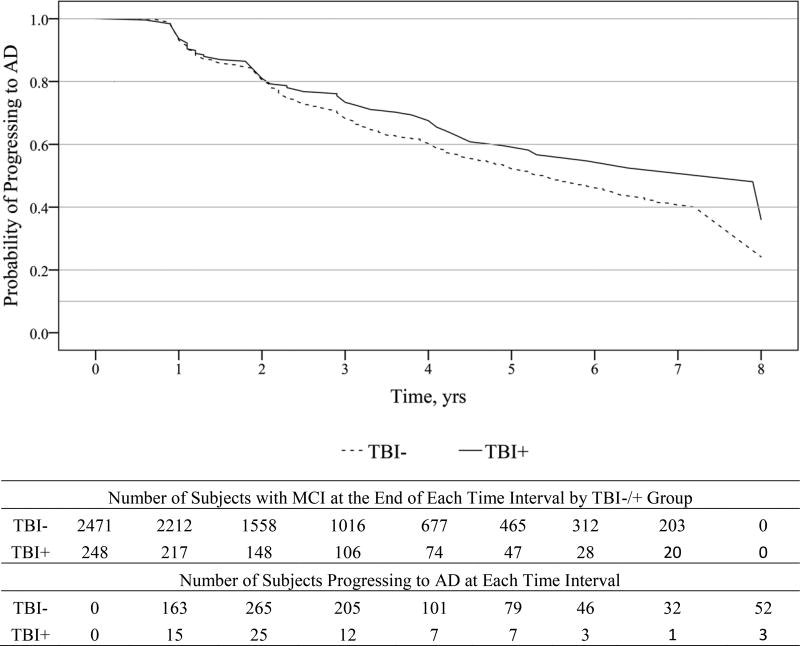

Progression of diagnosis

TBI history alone was not significantly associated with progression from MCI to a diagnosis of AD (Figure 2; HR=0.80; 95% CI=0.63 to 1.01; p=.06), but a trend toward slower progression in TBI+ subjects was seen. However, this association diminished further (HR=0.84; 95% CI=0.66 to 1.07; p=.15; Table 2) after adjusting for age of MCI diagnosis, race, presence of Apoe4 alleles, and family history of dementia; individual adjustment for each covariate showed that age of MCI diagnosis eliminated the trend for history of TBI. Similarly, among subjects with MCIamn at baseline, history of TBI was a non-significant predictor for progression to AD in unadjusted (HR=0.84; 95% CI=0.66 to 1.08; p=.17) and adjusted (HR=0.90; 95% CI=0.70 to 1.15; p=.39) models.

Figure 2.

Survival curve for progressing from MCI to AD in subjects with and without a history of TBI over 8 years. MCI = mild cognitive impairment; AD = Alzheimer disease; TBI+ = subjects with a history of traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness.

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios, Confidence Intervals, and Statistics for Survival Analyses Predicting Progression from MCI to AD Among the Combined MCI Sample

| HR | 95% CI for HR | LR χ2 p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Unadjusted Model | |||

|

| |||

| TBI history* | 0.80 | 0.63 – 1.01 | .06 |

| Adjusted Model | |||

|

| |||

| TBI history | 0.88 | 0.69 – 1.12 | .30 |

| Age* | 1.04 | 1.03 – 1.05 | <.001 |

| Family History of Dementia* | 1.11 | 0.97 – 1.26 | .13 |

| Apoe4 alleles | |||

| 1 allele* | 1.87 | 1.63 – 2.14 | <.001 |

| 2 alleles* | 2.67 | 2.18 – 3.28 | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| African American* | 0.56 | 0.45 – 0.71 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.83 | 0.62 – 1.12 | .22 |

| Other, Non-white | 1.13 | 0.76 – 1.67 | .56 |

Note. n = 2,719.

p < .05.

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; LR = log rank test; TBI = traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness; Apoe4 = apolipoprotein E-e4; CAIDE = the Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging and Incidence of Dementia risk score; Other, Non-white = Asian/Pacific Islander/Native American background.

Cognitive decline

Among subjects progressing to an AD diagnosis (≥3 completed visits; TBI+ n=62, TBI− n=804), random regression showed that a history of TBI with LOC was a non-significant predictor for cognitive decline as reflected by the CDR-SB score (b=0.15, p=.38). While CDR-SB scores across 5 visits provided the model of best fit (Akaike information criterion; Model 1=15,476 vs. Model 2=16,953), the results remained unchanged when CDR-SB scores were examined across 6 visits (Table 3). Examination of subjects with MCIamn who progressed to AD (TBI+ n=55, TBI− n=736) showed similar results.

Table 3.

Coefficients, Confidence Intervals, and Statistics for Predicting Decline on CDR-SB scores in the Combined MCI Sample who Progressed to AD

| Model 1 (5 visits) | Model 2 (6 visits) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | 95% CI | p | b | 95% CI | p | |

|

|

||||||

| Sex, Female*Ϯ | −0.31 | −0.48 – −0.13 | .001 | −0.34 | −0.53 – −0.16 | <.001 |

| Education | −0.02 | −0.06 – 0.01 | .11 | |||

| Race | ||||||

| African American | −0.20 | −0.51 – 0.12 | .22 | −0.25 | −0.58 – 0.08 | .14 |

| Hispanic | 0.12 | −0.31 – 0.55 | .58 | 0.06 | −0.39 – 0.51 | .81 |

| Other, Non-white*Ϯ | 0.91 | 0.29 – 1.53 | .004 | 0.97 | 0.33 – 1.61 | .003 |

| History of Depression* | 0.24 | 0.04 – 0.44 | .02 | 0.25 | 0.00 – 0.50 | .05 |

| TBI History with LOC | 0.15 | −0.19 – 0.49 | .38 | 0.21 | −0.14 – 0.56 | .24 |

Note. n = 1,016.

p < .05 in Model 1.

p < .05 in Model 2.

CI = confidence interval; b = coefficients; MCI = Mild cognitive impairment; AD = Alzheimer disease TBI = traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness; Other, Non-white = Asian/Pacific Islander/Native American background

Discussion

This study is the first to examine whether a history of TBI was associated with progression from MCI to AD. Despite a history of TBI with LOC being linked to an approximately 2.5 year earlier diagnosis of MCI as shown in a previous study by LoBue et al. (2016a), TBI history was not associated with progression to AD up to 8 years. Whereas a history of TBI initially showed a trend for a reduced risk for progression from MCI to AD, with annual rates of progression being slightly less for subjects with a history of TBI (8%) relative to those without (10%), this trend association was eliminated after adjusting for the earlier age of MCI diagnosis seen in the TBI+ group. Similar results were observed when analyses were confined to subjects diagnosed with amnestic MCI at baseline.

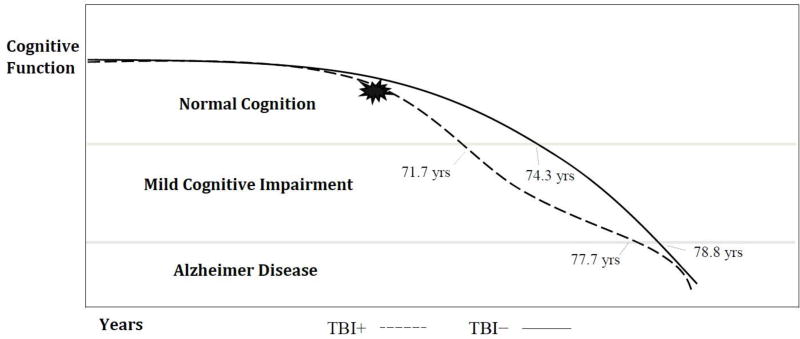

Because a history of TBI with LOC is linked to an earlier onset of MCI, these findings add to a growing literature suggesting that TBI might accelerate the accumulation of AD-related pathology. For example, a history of TBI may be a risk factor for earlier development of MCI via contributing to the accumulation of tau and Aβ pathology found in AD. However, once the neurodegenerative process for MCI to AD begins, TBI history appears unrelated to subsequent decline (Figure 3). These findings may reflect a threshold-lowering phenomenon similar to the relationship between cerebrovascular insults and the initial clinical expression of AD, wherein subsequent progressive decline is related to the AD process rather than cerebrovascular factors per se (Attems & Jellinger, 2014; Gorelick et al., 2011).

Figure 3.

Timeline of progression from MCI to AD for subjects with and without a history of TBI. MCI = age of diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment; AD = age of diagnosis of Alzheimer disease; TBI+ = a history of traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness.

Although moderate-to-severe TBI is considered a significant risk factor for developing AD, a mechanistic link remains unclear. TBI has been hypothesized to initiate a neurodegenerative process, accelerate the expression of neurodegenerative diseases, and/or disrupt neuronal/cognitive reserve and interact with aging and other factors (Gardner et al., 2014). It has previously been found that between 1 and 4 years after a moderate-to-severe injury, TBI patients show greater diffuse white matter atrophy compared to age-matched controls (Farbota et al., 2012), which has also been observed in retired professional athletes with cognitive impairment and a history of multiple concussions (Hart et al., 2013). Damage to white matter tracts is believed to initiate an accumulation of Aβ plaques and NFTs (Johnson et al., 2013). Furthermore, a recent neuroimaging study found that years after injury (range = 1 to 17), Aβ plaques were present to a greater degree in-vivo in a small sample of moderate-to-severe TBI patients compared to an older cognitively normal group (nearly 20 years older), and that Aβ deposition was associated with greater white matter damage, partially overlapping the pattern seen in AD (Scott et al., 2016). Such findings support the notion that moderate-to-severe TBI is associated with white matter degenerative changes that may initiate/accelerate AD-related pathology. However, findings from one of the largest autopsy investigations (n = 1,589) to date showed that although AD-related pathology was common in individuals with a history of TBI and LOC, a history of TBI occurring more than 40 years prior was found to only be associated with accumulation of Lewy Body pathology and an increased risk for developing Parkinson’s disease (Crane et al., 2016). Thus, what remains to be seen is whether TBI leads to AD-related pathological changes that continue beyond a few years or eventually stabilize, and whether similar changes occur in milder TBI severities.

In the present study, we did not find a link between a history of TBI and rate of progression from MCI to AD, as overall impairment levels (i.e., CDR-SB scores) did not differ between the TBI+ and TBI− groups at time of MCI diagnosis, nor was a history of TBI associated with more rapid decline among subjects who progressed to AD. Given that greater AD-related pathology has been associated with accelerated aging and greater cognitive impairment (Rodrigue et al., 2012), these findings are perhaps contrary to what we might expect if TBI somehow triggers the progressive development of AD-related pathology, although TBIs in this sample may have occurred years or even decades earlier. Furthermore, a majority of our TBI sample (65%) self-reported a history of mild TBI (< 5 minutes of LOC) as opposed to more serious injuries that much of the evidence linking TBI to the development of AD stems from. Another issue related to neuropathological changes after TBI may involve the timing of TBI, as injuries occurring later in life may play an important role in rate of cognitive decline related to AD. In an investigation that followed 325 individuals diagnosed with AD over time (median of 1.5 years), a history of TBI (i.e., head injury resulting in LOC, medical attention, or post-traumatic amnesia) within 10 years of AD onset (n = 14) was found to be associated with more rapid decline on CDR-SB scores after dementia onset, while more remote TBIs were not (TBI history > 10 years prior to onset; n = 49) (Gilbert et al., 2014). Taken together, a history of remote TBI does not appear to influence the course of cognitive decline from MCI to AD. However, further investigation is needed, as the implications of TBI severity and age at time of injury are unknown.

Limitations

One limitation relates to the lack of TBI details in the NACC dataset, as our ability to examine potentially important variables that could play a role in progression to AD was narrow. NACC’s cutoff of <5 and ≥5 minutes LOC for TBI includes a wide range of severities. As such, we could not examine TBI severity, which may have important implications given that moderate-to-severe TBI has been found to be a significant risk factor for developing AD. In addition, with the definition for “remote” TBI (i.e., >1 year), injuries may have occurred as recently as nearly one year prior to the initial ADC visit or decades earlier. It is possible subjects may have a >1 year time period between onset of symptoms of MCI and the age they arrived at an ADC for diagnosis; thus, an unknown proportion of TBIs in our sample may have occurred following onset of MCI or may have occurred in close temporal relationship to MCI symptom onset. Furthermore, our classification of TBI relied upon retrospective self-report methods, and although this is consistent with prior studies, recall bias/inaccuracy is possible and could limit accuracy in reporting a history of TBI. Another potential limitation is that while most subjects had a median of 4 annual visits and follow-up was up to 8 years for some individuals, subject drop-out exceeded 80% beyond 6 years, which could restrict generalization of the findings at longer intervals.

Conclusions

A history of TBI with LOC was associated with an earlier age of diagnosis of MCI, but not progression to AD over the course of 8 years in this longitudinal investigation derived from a national multicenter database. Individuals with a history of TBI with LOC did not show faster progression from MCI to AD, higher annual rates of progression, or a greater rate of cognitive decline than those without a TBI history. While these results provide evidence that TBI might contribute to a neurodegenerative process by slightly accelerating its onset for some individuals, the implications of various TBI characteristics (i.e., severity and time since injury) remain unclear and deserve further investigation. Future studies with longitudinal neuroimaging after TBI, evaluation of neuropsychological patterns, and more detailed assessment of TBI features in individuals presenting for dementia evaluation, are needed in order to further understand the implications of TBI on risk for later cognitive decline.

Public Significance Statement.

A history of traumatic brain injury might contribute to a neurodegenerative process by slightly accelerating its onset for some individuals, but appears unrelated to subsequent decline. This is contrary to what would be expected if a brain injury somehow triggers the progressive development of a neurodegenerative disease. However, further research is needed, as the effects of injury severity and age at time of injury are unknown.

References

- Abisambra JF, Scheff S. Brain injury in the context of tauopathies. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2014;40:495–518. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attems J, Jellinger KA. The overlap between vascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease–lessons from pathology. BMC Medicine. 2014;12:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0206-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DE, Kaup A, Kirby KA, Byers AL, Diaz-Arrastia R, Yaffe K. Traumatic brain injury and risk of dementia in older veterans. Neurology. 2014;83(4):312–319. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedarbaum JM, Jaros M, Hernandez C, Coley N, Andrieu S, Grundman M, Bruno V. Rationale for use of the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes as a primary outcome measure for Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2013;9:S45–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Dams-O’Connor K, Trittschuh E, Leverenz JB, Keene CD, Schneider JA. Association of traumatic brain injury with late-life neurodegenerative conditions and neuropathologic findings. JAMA Neurology. 2016;73(9):1062–1069. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exalto LG, Quesenberry CP, Barnes D, Kivipelto M, Biessels GJ, Whitmer RA. Midlife risk score for the prediction of dementia four decades later. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2014;10:562–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.05.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farbota KD, Sodhi A, Bendlin BB, McLaren DG, Xu G, Rowley HA, Johnson SC. Longitudinal volumetric changes following traumatic brain injury: a tensor-based morphometry study. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2012;18:1006–1018. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712000835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey D, DeCarli C. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia in clinic-vs community-based cohorts. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66:1151–1157. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleminger S, Oliver DL, Lovestone S, Rabe-Hesketh S, Giora A. Head injury as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease: the evidence 10 years on; a partial replication. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2003;74:857–862. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.7.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RC, Burke JF, Nettiksimmons J, Kaup A, Barnes DE, Yaffe K. Dementia risk after traumatic brain injury vs nonbrain trauma: the role of age and severity. JAMA Neurology. 2014;71(12):1490–1497. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry LR, Godersky JC, Thompson B. MR imaging of head trauma: review of the distribution and radiopathologic features of traumatic lesions. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 1988;9:101–110. doi: 10.2214/ajr.150.3.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert M, Snyder C, Corcoran C, Norton MC, Lyketsos CG, Tschanz JT. The association of traumatic brain injury with rate of progression of cognitive and functional impairment in a population-based cohort of Alzheimer's disease: the Cache County Dementia Progression Study. International Psychogeriatrics. 2014;26:1593–1601. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giza CC, Hovda DA. The new neurometabolic cascade of concussion. Neurosurgery. 2014;75:S24–S33. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, DeCarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, Petersen RC. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:2672–2713. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart J, Kraut MA, Womack KB, Strain J, Didehbani N, Bartz E, Cullum CM. Neuroimaging of cognitive dysfunction and depression in aging retired National Football League players: a cross-sectional study. JAMA Neurology. 2013;70:326–335. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamaneurol.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomovic MD, Uryu K, Abrahamson EE, Ciallella JR, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, DeKosky ST. Alzheimer's pathology in human temporal cortex surgically excised after severe brain injury. Experimental Neurology. 2004;190:192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Traumatic brain injury and amyloid-β pathology: a link to Alzheimer's disease? Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11:361–370. doi: 10.1038/nrn2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury. Experimental Neurology. 2013;246:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Widespread tau and amyloid-beta pathology many years after a single traumatic brain injury in humans. Brain Pathology. 2012;22:142–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00513.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepsell TD, Monsell SE. Reversion from mild cognitive impairment to normal or near-normal cognition Risk factors and prognosis. Neurology. 2012;79:1591–1598. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826e26b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBue C, Denney D, Hynan LS, Rossetti HC, Lacritz LH, Hart J, Jr, Cullum CM. Self-reported traumatic brain injury and mild cognitive impairment: increased risk and earlier age of diagnosis. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2016a;51:727–736. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBue C, Wilmoth K, Cullum CM, Rossetti HC, Lacritz LH, Hynan LS, Womack KB. Traumatic brain injury history is associated with earlier age of onset of frontotemporal dementia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2016b;87:817–820. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-311438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messé A, Caplain S, Paradot G, Garrigue D, Mineo JF, Soto Ares G, Pélégrini-Issac M. Diffusion tensor imaging and white matter lesions at the subacute stage in mild traumatic brain injury with persistent neurobehavioral impairment. Human brain Mapping. 2011;32:999–1011. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, Cummings J, DeCarli C, Ferris S, Peskind ER. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2006;20:210–216. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213865.09806.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Braak H, Markesbery WR. Neuropathology and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer disease: a complex but coherent relationship. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2009;68:1–14. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181919a48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Archives of Neurology. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment: transition from aging to Alzheimer's disease. Neurologia. 2001;15:93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Morris JC. Mild cognitive impairment as a clinical entity and treatment target. Archives of Neurology. 2005;62:1160–1163. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.7.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plassman BL, Havlik RJ, Steffens DC, Helms MJ, Newman TN, Drosdick D, Burke JR. Documented head injury in early adulthood and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Neurology. 2000;55:1158–1166. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.8.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Devous MD, Rieck JR, Hebrank AC, Diaz-Arrastia R, Park DC. β-Amyloid burden in healthy aging Regional distribution and cognitive consequences. Neurology. 2012;78:387–395. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318245d295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivanandam TM, Thakur MK. Traumatic brain injury: a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2012;36:1376–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyas SL, Salazar JC, Snowdon DA, Desrosiers MF, Riley KP, Mendiondo MS, Kryscio RJ. Transitions to mild cognitive impairments, dementia, and death: findings from the Nun Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;165:1231–1238. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott G, Ramlackhansingh AF, Edison P, Hellyer P, Cole J, Veronese M, Heckemann RA. Amyloid pathology and axonal injury after brain trauma. Neurology. 2016;86:821–828. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos S, van Rossum IA, Verhey F, Knol DL, Soininen H, Wahlund L, Frisoni GB. Prediction of Alzheimer disease in subjects with amnestic and nonamnestic MCI. Neurology. 2013;80:1124–1132. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318288690c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Tan L, Wang HF, Jiang T, Tan MS, Tan L, Yu JT. Meta-analysis of modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2015;86:1299–1306. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-310548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappalà G, Thiebaut de Schotten M, Eslinger PJ. Traumatic brain injury and the frontal lobes: what can we gain with diffusion tensor imaging? Cortex. 2012;48:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]