Abstract

Homologous recombination (HR) is an error-free DNA repair mechanism that maintains genome integrity by repairing double-strand breaks (DSBs). Defects in HR lead to genomic instability and are associated with cancer predisposition. A key step in HR is the formation of Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments which are responsible for the homology search and strand invasion steps that define HR. Recently, the budding yeast Shu complex has emerged as an important regulator of Rad51 along with the other Rad51 mediators including Rad52 and the Rad51 paralogs, Rad55-Rad57. The Shu complex is a heterotetramer consisting of two novel Rad51 paralogs, Psy3 and Csm2, along with Shu1 and a SWIM domain-containing protein, Shu2. Studies done primarily in yeast have provided evidence that the Shu complex regulates HR at several types of DNA DSBs (i.e. replication-associated and meiotic DSBs) and that its role in HR is highly conserved across eukaryotic lineages. This review highlights the main findings of these studies and discusses the proposed specific roles of the Shu complex in many aspects of recombination-mediated DNA repair.

Keywords: Shu complex; homologous recombination; Rad51 paralogs, Rad51; Sws1

The Shu complex is a conserved double-strand break repair regulator that promotes error-free homologous recombination to repair DNA replicative damage and meiotic breaks.

INTRODUCTION

To maintain genome stability, numerous cellular mechanisms have evolved to repair damaged DNA. Among these, homologous recombination (HR) is considered an error-free DNA repair mechanism that repairs double-strand breaks (DSBs), one of the most cytotoxic DNA lesions. DSBs can arise from errors in DNA metabolism, such as during DNA replication, as well as by exposure to exogenous DNA-damaging agents such as ionizing radiation (IR) and chemotherapeutic drugs. Misrepaired DSBs can lead to mutations or chromosomal rearrangements, which are hallmarks of cancer cells. Accordingly, HR is a tightly controlled process and its deregulation leads to genome instability and tumorigenesis. The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae primarily uses HR to repair DSBs, and therefore this organism has long been used to study how DSB repair by HR is regulated (Symington, Rothstein and Lisby 2014). Since HR is highly conserved among eukaryotes, experimental findings in budding yeast are often applicable to other systems. Here, we will focus on regulation of HR by a novel complex of proteins, called the Shu complex (also referred to as the PCSS complex) (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Sasanuma et al.2013). The budding yeast Shu complex is a heterotetramer (Shu1, Shu2, Csm2 and Psy3) that promotes HR by regulating a key step of HR, the formation of Rad51 filaments (Gaines et al.2015). In addition, there is increasing evidence for a role of the Shu complex in HR that is triggered during replication fork stalling and collapse.

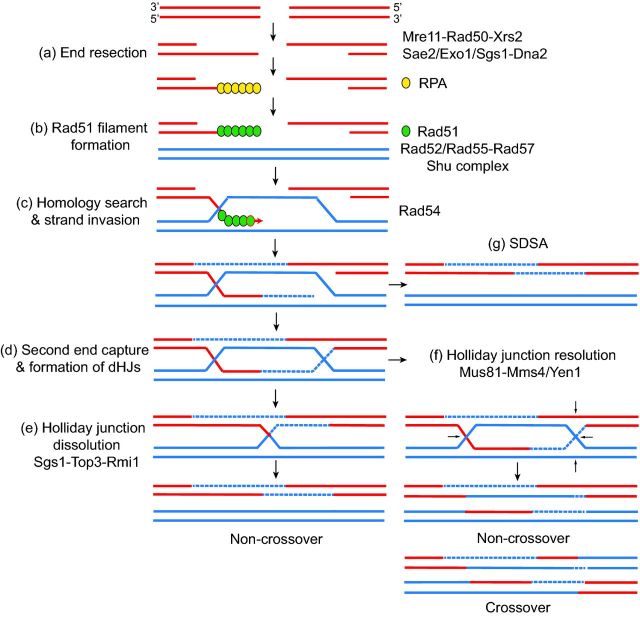

HR is a highly regulated process that begins upon DSB formation and recognition by the DNA damage checkpoint (Jasin and Rothstein 2013; Kowalczykowski 2015). HR is also utilized for the restart and repair of stalled and collapsed replication forks, respectively. Here, we will describe canonical HR; however, the Shu complex primarily functions to promote HR in the context of DNA replication. During canonical HR, the DNA ends of the break site are then resected in the 5′-3′ direction by the Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 complex in conjunction with Sae2 (Paull 2010; Symington 2014; Cejka 2015) (Fig. 1a). Long-range DNA end resection then occurs by the DNA exonuclease Exo1, or the Sgs1 helicase in conjunction with the endonuclease Dna2 (Mimitou and Symington 2008; Zhu et al.2008) (Fig. 1). The 3′ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) ends are quickly coated by the replication protein A (RPA) complex, a heterotrimer of Rfa1, Rfa2 and Rfa3, which prevents degradation of the ssDNA and removes secondary structures from ssDNA to facilitate Rad51 loading. Subsequently, RPA-coated ssDNA is displaced by the RecA-like protein Rad51 to form a pre-synaptic filament (Brill and Stillman 1991; Sugiyama, Zaitseva and Kowalczykowski 1997) (Fig. 1b). Rad51 loading on RPA-coated ssDNA is facilitated by Rad52 (Sung 1997a; New et al.1998; Shinohara and Ogawa 1998). Rad51 forms a helical nucleoprotein filament that is essential for the homology search and strand invasion steps that define HR. Once homology is found, Rad51 filaments invade the donor homologous duplex leading to the formation of a displacement loop (D-loop). Rad51's strand exchange activity is stimulated by the Rad54 translocase (Fig. 1c) (Petukhova et al.1999; Ceballos and Heyer 2011). The 3′ end of the invading filament primes DNA synthesis and the D-loop is extended, while exposing ssDNA complimentary to the other 3′ end of the resected DSB (Fig. 1c). The second end of the DSB can be captured giving rise to a double-Holliday junction (dHJ) (Fig. 1d). This structure can be dissolved by the Sgs1-Top3-Rmi1 complex or resolved by Mus81-Mms4/Yen1 nucleases yielding either non-crossover or crossover products (Fig. 1e–f) (Wyatt and West 2014). Alternatively, in synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA), the newly synthesized strand dissociates from the D-loop and anneals to the ssDNA on the other end of the break leading to a non-crossover product (Fig. 1g) (Allers and Lichten 2001).

Figure 1.

Schematic of double-strand break (DSB) repair by homologous recombination (HR). (a) Upon DSB formation, the ends of the break are resected by the combined actions of Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2, Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1-Dna2. (b) Following resection, the 3′ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs are stabilized by the replication protein A (RPA) complex. Displacement of RPA and consequent Rad51 filament formation is aided by Rad52, the Rad51 paralogs Rad55-57 and the Shu complex. (c) The Rad51 filament performs the homology search and invades an adjacent strand leading to D-loop formation. The homologous sequences are used as a repair template. (d) Second-end capture results in a double-Holliday junction (dHJ) formation. (e) The dHJ can be dissolved by the Sgs1-Top3-Rmi1 complex leading to non-crossover products. (f) Alternatively, the dHJ can be resolved by Mus81-Mms4/Yen1 to yield either non-crossover or crossover products. The arrows show where the cutting occurs. (g) In synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA), the end of the newly synthesized DNA re-anneals with the top strand, leading to a non-crossover. The red lines represent the DNA that contained a DSB. The solid blue lines are the homologous chromosome or a sister chromatid. Dotted blue lines represent new DNA synthesized during repair.

A defining step of HR-mediated repair is the assembly of a pre-synaptic Rad51 nucleoprotein filament (Karpenshif and Bernstein 2012; Godin, Sullivan and Bernstein 2016). Regulation of Rad51 is controlled by factors that promote assembly and disassembly of Rad51 monomers onto the ssDNA. The pro-recombination factors have been termed the so-called ‘Rad51 mediators’. In humans, a critical RAD51 mediator is BRCA2, which is important for loading human RAD51 onto the ssDNA, while in budding yeast an analogous function is carried out by Rad52 (Sung 1997a; New et al.1998; Yang et al.2005). In addition to Rad52's role as a Rad51 mediator by nucleating Rad51 filament assembly, it carries out an annealing function by promoting second-end capture (Mortensen, Lisby and Rothstein 2009). Another significant group of Rad51 mediators is the Rad51 paralogs, which include proteins that structurally resemble Rad51 in their ATPase core (Albala et al.1997; Dosanjh et al.1998; Liu et al.1998, 2011; Braybrooke et al.2000). The human RAD51 paralogs include RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D, XRCC2, XRCC3 and a more recently described highly divergent paralog, SWSAP1 (Tebbs et al.1995; Albala et al.1997; Cartwright et al.1998; Dosanjh et al.1998; Pittman, Weinberg and Schimenti 1998; Liu et al.2011b). The yeast Rad51 paralogs include Rad55-Rad57 and more recently the Shu complex members Csm2 and Psy3 (Sung 1997b; She et al.2012; Tao et al.2012; Godin et al.2015). Together, the Rad51 mediators perform several functions, first to nucleate Rad51 filament formation, and subsequently to stabilize and elongate the filaments (Sugiyama, Zaitseva and Kowalczykowski 1997). However, the exact function of the Rad51 paralogs is not well defined and the concerted action of the Rad51 mediators is just beginning to be revealed (Gaines et al.2015; Prakash et al.2015; Godin, Sullivan and Bernstein 2016). Mutations in genes that regulate Rad51 filament assembly are associated with Fanconi anemia and cancer predisposition, particularly breast and ovarian cancers (Wooster et al.1995; Phelan et al.1996; Thorlacius et al.1996; Meindl et al.2010; Somyajit, Subramanya and Nagaraju 2010; Vaz et al.2010; Loveday et al.2011; Hilbers et al.2012; Park et al.2012; Golmard et al.2013; Prakash et al.2015). Given these links between mutations in the human RAD51 mediators with cancer predisposition and Fanconi anemia, there is a critical need to understand their function. Due to the embryonic lethality observed in the mouse knockout models and the low abundance and insolubility of the individual human RAD51 paralogs (Shu et al.1999; Deans et al.2000; Pittman and Schimenti 2000; Kuznetsov et al.2009; Smeenk et al.2010; Suwaki, Klare and Tarsounas 2011), yeast has provided an excellent system to elucidate Rad51 mediator function.

IDENTIFICATION OF THE BUDDING YEAST Shu COMPLEX

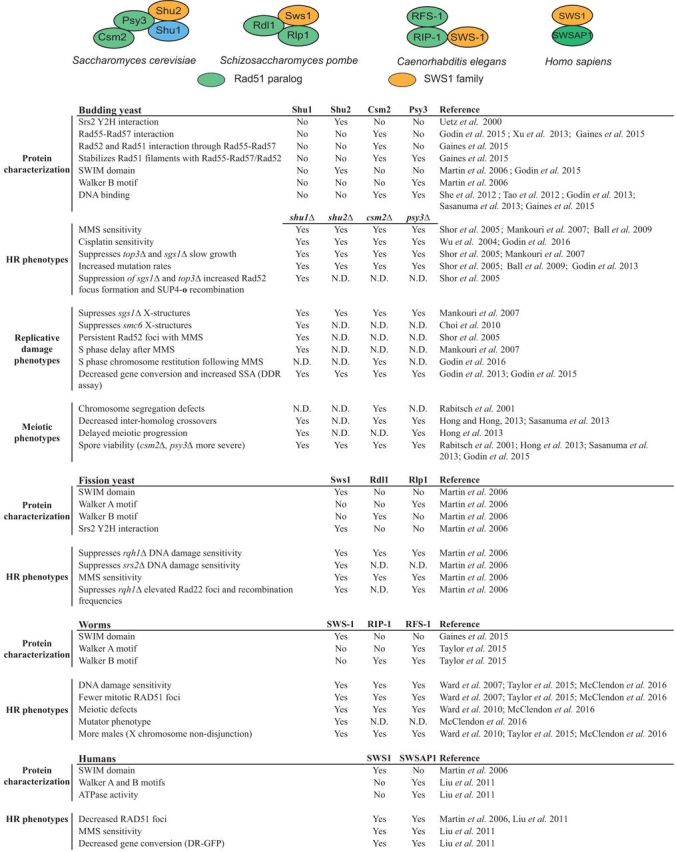

The Shu complex genes SHU1, SHU2, PSY3 and CSM2 were identified in a genetic screen for suppressors of the slow growth phenotype and DNA damage sensitivity observed with topoisomerase 3 deletion (top3Δ), a gene important for both DNA end resection and dissolution of dHJs as part of the Sgs1-Top3-Rmi1 protein complex (Ira et al.2003; Wu and Hickson 2003; Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Cejka et al.2010; Niu et al.2010). Similar to suppressing the top3Δ phenotype, deletion of the Shu complex members also suppresses sgs1Δ cells DNA damage sensitivity to hydroxyurea (HU) and the hyper-recombination observed at the SUP4-ο locus (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005). Comparable results are also observed upon disruption of RAD52 and its epistasis group of genes including RAD55-RAD57 and RAD59 (Shor et al.2002; Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005). Furthermore, cells with disruption of the Shu genes are sensitive to methylmethane sulfonate (MMS), a DNA-alkylating agent (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Mankouri, Ngo and Hickson 2007; Ball et al.2009). In addition, knocking out the individual Shu complex members results in similar MMS sensitivity as the quadruple Shu complex mutant (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005). Yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H) analysis revealed that the Shu proteins interact with each other to form a complex (Ito et al.2001; Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Ball et al.2009). Together, these results suggest that these four proteins are in the same epistasis group and part of a larger complex (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005). Please note that Table 1 includes a summary of the protein characteristics and genetic results observed for the different Shu complexes in multiple species.

Table 1.

Summary of Shu complexes and phenotypes across eukaryotes. This table highlights known members of the Shu complex in budding yeast, fission yeast, worms and humans. Green circles are Rad51 paralogs, while orange circles represent Shu2/SWS1 family members. The table summarizes protein characterization and presence or absence of observed phenotypes for each individual member of the Shu complex across taxa. N.D. indicates that there is no data available.

|

Genetic analyses have consistently placed the Shu genes in the RAD52 epistasis group that includes genes involved in DSB repair through HR (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Mankouri, Ngo and Hickson 2007). Consistent with a role of Shu genes in HR, Shu complex mutants exhibit fewer Rad51-mediated gene conversion events and more Rad51-independent single-strand annealing (SSA) events, as measured by a direct repeat recombination assay (Godin et al.2013, 2015). In addition, cells with mutations in Shu genes also exhibit increased mutation rates (7–10× over wild-type cells), which are dependent upon the translesion synthesis pathway (TLS) (Huang et al.2003; Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Ball et al.2009). Together, these results suggest that the Shu complex is an important contributor to promoting error-free HR at the expense of other error-prone repair mechanisms such as TLS and SSA.

Although initially thought to be unique to budding yeast, Shu complex members were later discovered in the fission yeast Saccharomyces pombe in a Y2H screen for novel S. pombe Srs2-interacting proteins (Martin et al.2006). The budding yeast Shu2 protein was also found to interact with Srs2 by Y2H in a genome-wide screen (Ito et al.2001). The fission yeast screen identified a SWIM domain-containing protein, which resembled S. cerevisiae Shu2 (Martin et al.2006). This fission yeast protein was named Sws1 (SWIM domain-containing and Srs2-interacting protein 1) and similar to budding yeast shu2Δ mutants, sws1Δ mutant cells are also MMS sensitive. In addition, sws1Δ also suppresses the DNA damage sensitivity of srs2Δ and rqh1Δ (the S. pombe SGS1 homolog) cells [camptothecin (CPT) for srs2Δ and CPT, HU, UV, IR and low doses of MMS for rqh1Δ (Martin et al.2006)]. Like budding yeast, the fission yeast Sws1 protein also associates with the Rad51 paralogs, Rlp1 and Rdl1, which were hypothesized to bear similarity to the human Rad51 paralogs XRCC2 and RAD51D, respectively (Martin et al.2006). Together, Sws1, Rlp1 and Rdl1 form a pro-recombinogenic complex that controls an early HR step (Martin et al.2006).

A unique feature of the Shu complex is the presence of a SWIM domain in one of its members, Shu2/Sws1. The SWIM domain is a Zn finger-like domain that consists of a canonical sequence CXC…Xn…CXH (Makarova, Aravind and Koonin 2002). This domain is represented in bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes and is predicted to bind DNA or mediate protein–protein interactions (Makarova, Aravind and Koonin 2002; Godin et al.2015; McClendon et al.2016). The SWIM domain is also found in bacterial ATPases of the SWI2/SNF2 family, plant MuDR transposases and vertebrate MEKK1 (Makarova, Aravind and Koonin 2002). Additional, sequence analysis expanded the Shu2/SWS1 protein family SWIM domain to include an invariant alanine (CXC…Xn…CXHXXA) and showed that it is conserved across all eukaryotic lineages (Godin et al.2015). Consistent with the predicted role of the SWIM domain in protein–protein interactions, mutating invariable residues, C114S, C116S, C176S and H178A, within the SWIM domain of yeast Shu2 abolish Y2H interactions with the other Shu complex members, Shu1 and Psy3 (Godin et al.2015). Moreover, these residues are also important for the repair of MMS-induced DNA damage and for Shu2's meiotic function (Godin et al.2015).

In addition to the Shu complex containing a member of the Shu2/SWS1 protein family, in all species where the Shu complex has been analyzed, it is also composed of Rad51 paralogs (Martin et al.2006; Liu et al.2011b; Godin et al.2015; McClendon et al.2016) (Table 1). Structural analysis of purified Csm2-Psy3 shows that although these proteins only share 17% sequence homology, they have a similar architecture, mainly consisting of a set of β-sheets flanked by α-helices (She et al.2012; Tao et al.2012; Sasanuma et al.2013). The interface between Csm2 and Psy3 includes extensive hydrogen bonding (Sasanuma et al.2013). Furthermore, the Csm2-Psy3 heterodimer closely resembles the ATPase core domain of the Rad51 recombinase and as such, Csm2 and Psy3, represents novel Rad51 paralogs (She et al.2012; Tao et al.2012; Sasanuma et al.2013). In vitro studies with purified proteins show that the Csm2-Psy3 heterodimer is responsible for the DNA-binding activity of the Shu complex (She et al.2012; Tao et al.2012; Sasanuma et al.2013). Unlike Rad51, binding of Csm2-Psy3 to DNA is independent of co-factors or ATP (Godin et al.2013; Sasanuma et al.2013). Fluorescence anisotropy experiments show that Csm2-Psy3 preferentially binds to a forked DNA substrate, and, to a lesser extent, 3′ overhang DNA, which are DNA structures utilized by the HR pathway in vivo (Godin et al.2013). In contrast to Csm2-Psy3, the Shu1-Shu2 heterodimer does not bind DNA in vitro (Sasanuma et al.2013). However, Shu1-Shu2-Psy3 can bind ssDNA and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), suggesting that a DNA-binding interface may be formed between Psy3 and Shu1-Shu2 (Tao et al.2012).

THE Shu COMPLEX FUNCTION DURING HR IS TO PROMOTE Rad51 FILAMENT ASSEMBLY

In vitro and genetic studies done primarily in budding yeast have provided strong evidence that the Shu complex regulates HR. The Shu complex belongs to the RAD52 epistasis group, which includes genes central to HR such as RAD51, RAD54 and the Rad51 paralogs, RAD55-RAD57 (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Mankouri, Ngo and Hickson 2007). One of the first indications that the Shu complex may regulate some aspects of RAD52-dependent recombination repair was the observation that Rad52-YFP foci persist longer in MMS-exposed shu1Δ mutant cells (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005). Further, genetic analyses of shu1Δ mutants in rad52Δ and rad51Δ backgrounds revealed that these cells do not exhibit increased sensitivity to MMS when compared to the single rad52Δ or rad51Δ mutants, thus supporting the inclusion of the Shu complex in the RAD52 epistasis group (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Mankouri, Ngo and Hickson 2007). Similar results are observed in rad55Δ and rad55Δ csm2Δ cells that are equally sensitive to MMS and IR when compared to wild type or csm2Δ alone (Godin et al.2013). Unlike the other members of the RAD52 epistasis group, Shu complex mutants exhibit limited DNA damage sensitivity and are proficient for repair of direct DSB-inducing agents such as IR (Martin et al.2006). Therefore, rad52Δ, rad55Δ or rad57Δ mutants exhibit increased DNA damage sensitivity to a broader range of DNA-damaging agents such as IR, UV, HU (Game and Mortimer 1974; Prakash et al.1980; Johnson and Symington 1995; Herzberg et al.2006; Valencia-Burton et al.2006; Mozlin, Fung and Symington 2008; Godin et al.2016).

In addition to a genetic interaction between the Shu complex members and the other Rad51 mediators in the RAD52 epistasis group, physical interactions are also observed. Y2H and in vitro pull down experiments have revealed that Csm2 directly interacts with Rad55-Rad57 via Rad55 (Godin et al.2013; Xu et al.2013; Gaines et al.2015). Upon further analysis, it was found that the Rad55 interaction bridges an interaction of the Shu complex with Rad51 and Rad52 (Godin et al.2013; Gaines et al.2015). For example, by Y2H an interaction between Csm2 and Rad51 is seen, but this Y2H interaction is no longer observed upon rad55Δ disruption (Godin et al.2013; Xu et al.2013). Therefore, in the absence of RAD55, Csm2 can no longer interact with Rad51. Similar results are observed with Rad52, whose interaction with the Shu complex member, Csm2, is also bridged by Rad55 (Gaines et al.2015). These data suggest a model in which the Shu complex, along with the Rad51 mediators, Rad52 and Rad55-Rad57, form a higher order ensemble that regulates Rad51.

A direct role for the Shu complex in regulating Rad51 was shown by in vitro analyses of Rad51 loading onto RPA-coated ssDNA (Gaines et al.2015). Using different combinations of Rad52, Rad55-Rad57 and the Shu complex, Gaines et al. (2015) demonstrated that addition of the Shu complex to reactions containing Rad52 and Rad55-Rad57 results in a 2- to 3-fold stimulation in Rad51 loading onto RPA-coated ssDNA, compared to Rad52 and Rad55-57 alone. This study provided the first biochemical evidence that the Shu complex acts during Rad51 filament assembly through a synergistic interaction with Rad52 and Rad55-Rad57 (Gaines et al.2015). Intriguingly, the Csm2-Psy3 heterodimer is sufficient for stimulating Rad51 pre-synaptic filament assembly, suggesting that Shu1-Shu2 is not directly involved in Rad51 loading. Taking into consideration that the Csm2-Psy3 heterodimer possesses DNA-binding activity, and not Shu1-Shu2 (She et al.2012; Tao et al.2012; Sasanuma et al.2013), it is plausible that the binding of the Shu complex to DNA may be required for its stimulatory function on Rad51 filament assembly. Although Shu1-Shu2 are dispensable for the Shu complex's in vitro activity, in vivo SHU1 and SHU2 are just as important for Shu complex-mediated DNA repair (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Mankouri, Ngo and Hickson 2007; Godin et al.2015). Therefore, it remains to be determined how Shu1-Shu2 contribute to the Shu complex function in vivo.

Quite surprisingly, further analysis of the interactions between the Rad51 mediators indicated that it is the physical interaction between Csm2 and Rad55-Rad57 that is critical for the Shu complex's function in stimulating Rad51 pre-synaptic assembly. By using the crystal structure of Csm2-Psy3, solvent-exposed residues on the surface of Csm2 that were outside of the Csm2-Psy3 heterodimer interface were identified (Gaines et al.2015). Mutation of a highly conserved phenylalanine to an alanine (F46A) on surface of Csm2 abolishes its interaction with Rad55 (95% in vitro), and therefore indirectly blocks Csm2's interaction with Rad51 and Rad52 (Gaines et al.2015). Importantly, csm2-F46A maintains its DNA-binding activity and is still incorporated into the Shu complex with its binding partners Psy3, Shu1 and Shu2. However, the Shu complex containing the mutant csm2-F64A protein is unable to enhance Rad51 loading onto RPA-coated ssDNA, providing evidence that the interaction between the Shu complex and Rad55-Rad57 is essential for the Shu complex's in vitro function. Underscoring the importance of the interaction between the Shu complex and Rad55 for the biological functions of the Shu complex in HR, cells harboring the csm2-F46A mutation exhibit a similar phenotype to csm2Δ cells. For example, both csm2-F46A and csm2Δ mutants are similarly sensitive to MMS, exhibit increased mutation rates and have impaired gene conversion frequencies (Gaines et al.2015). Therefore, the Shu complex interaction with Rad55 is essential for its role in Rad51 regulation.

A ROLE FOR THE Shu COMPLEX DURING DNA REPLICATION

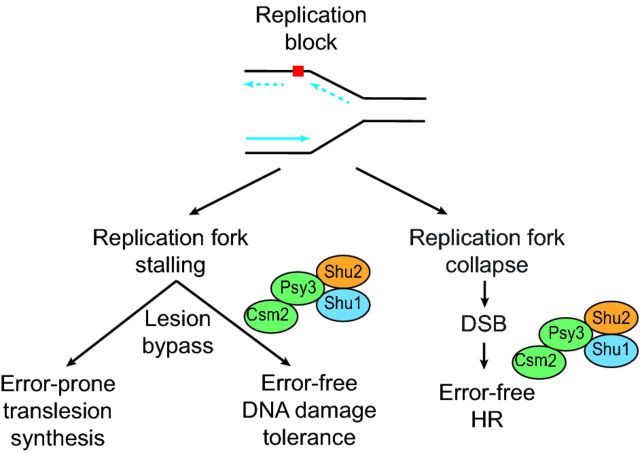

HR is an important error-free mechanism that is also utilized to bypass DNA lesions that can block replication fork progression (Branzei and Foiani 2010; Petermann and Helleday 2010). Increasing evidence suggests that the Shu complex has an important role in promoting HR at specific replication fork-blocking lesions (Godin et al.2016) (Fig. 2). For example, the Shu complex preferentially binds forked DNA substrates in vitro (Godin et al.2013), and Shu mutants are primarily sensitive to MMS. The Shu complex mutants also exhibit modest sensitivity to other replication-blocking lesions such as CPT as well as the cross-linking agent cisplatin (Godin et al.2016). In fact, PSY3 was initially named for its sensitivity to cisplatin [Platinum sensitivity 3 (Wu et al.2004)]. MMS is an alkylating agent and DNA alkylation is primarily repaired by the base excision repair (BER) pathway. However, if the replication fork encounters a BER intermediate, then those DNA intermediates (such as an abasic site or 3′ dRP) can block replication fork progression and lead to stalled or collapsed forks (Groth et al.2010). Indeed, the Shu complex mutants exhibit increased MMS sensitivity when BER intermediates accumulate by disruption of the DNA glycosylase MAG1 or the AP endonucleases APN1 and APN2 (St Onge et al.2007; Godin et al.2016). This poses the question as to whether the Shu complex may be specifically involved in promoting HR in the context of replication-induced DNA lesions.

Figure 2.

Role of the Shu complex in recombination repair of replicative damage. When a replication fork encounters a lesion (red square), the lesion can be bypassed by error-prone translesion synthesis or alternatively, by error-free DNA damage-tolerance mechanisms. If the fork collapses, a DSB forms. The DSB is repaired by error-free HR allowing the replication fork to be repaired and restarted. The Shu complex is involved in both error-free DNA damage-tolerance mechanisms as well as error-free HR.

Supporting a role for the Shu complex in DNA repair at a damaged replication fork, Shu complex mutants exhibit delayed S-phase progression upon MMS exposure as demonstrated by altered cell cycle profiles by FACS (Mankouri, Ngo and Hickson 2007). These results are supported by analyzing MMS-exposed cells for global chromosome changes during S phase when CSM2 is disrupted (Godin et al.2016). By pulsed field gel electrophoresis, csm2Δ cells have a delay in restoring their chromosomes (Godin et al.2016). Further, experimental evidence suggests that the Shu complex also functions in the RAD52 epistasis group during repair of replication-induced DNA damage. For example, upon MMS exposure, similar S-phase delays are observed in rad51Δ and rad54Δ cells, and no additive effects are seen in rad51Δ shu1Δ and rad54Δ shu1Δ cells (Mankouri, Ngo and Hickson 2007). The S-phase delay observed in these cells is likely due to their impaired ability to utilize recombination-mediated mechanisms to repair the MMS-induced DNA damage. In this scenario, error-prone TLS is utilized to bypass the MMS-induced lesions (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Godin et al.2016). Consistent with this hypothesis, disruption of the Shu genes results in a mutator phenotype, as measured by an increase in spontaneous CAN1 forward mutation rates (Huang et al.2003; Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005). Moreover, the mutation rates observed in Shu complex mutants are dependent on the error-prone TLS polymerase REV3 (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Ball et al.2009). Rev1 and Rev3 proteins are part of error-prone TLS pathway utilized to bypass DNA lesions that block replication (Lin, Wu and Wang 1999; Lin et al.1999; Haracska et al.2001; Goodman and Woodgate 2013). Furthermore, PSY3, CSM2 and SHU1 were identified in a genome-wide synthetic genetic array screen conducted to establish genes that become essential upon MMS exposure and in the absence of TLS (i.e. rev1Δ and rev3Δ mutants) (Ball et al.2009). Since this screen was performed in TLS-deficient mutants, it was hypothesized that the Shu genes might be involved in the error-free branch of post-replicative repair (PRR). During error-free PRR, the blocked leading strand engages in recombination-mediated template switching to use the newly synthesized strand as a repair template (Chang and Cimprich 2009). However, recent evidence shows a modest but reproducible slow growth defect when Shu complex mutant csm2Δ is combined with error-free PRR genes (rad5Δ, ubc13Δ and mms2Δ) suggesting that the Shu complex may have a function outside of the canonical error-free PRR pathway (Godin et al.2016). Similar defects were observed when gene conversion frequencies and mutation rates were measured in csm2Δ rad5Δ or csm2Δ ubc13Δ double mutant strains (Godin et al.2016). Therefore, in the absence of the Shu complex and error-free PRR, cells utilize TLS to bypass MMS-induced damage.

A role for the Shu complex in replication-associated DSB repair has also been observed in sgs1Δ cells (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Mankouri, Ngo and Hickson 2007; Ball et al.2009). In addition to Sgs1's role in canonical HR, the Sgs1 DNA helicase and its binding partners, Top3 and Rmi1, function in the repair and recovery of stalled replication forks (Gangloff et al.1994; Chang et al.2005; Mullen et al.2005; Ashton and Hickson 2010). One characteristic of MMS-exposed sgs1Δ cells is the accumulation of X-shaped structures, which represent recombination-like intermediates at replication origins (Liberi et al.2005; Giannattasio et al.2014). Two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis analyzing these X-molecules demonstrated that the increased MMS-induced X-molecules observed in sgs1Δ cells are partially suppressed by Shu complex disruption (Mankouri, Ngo and Hickson 2007). A similar suppression of X-molecules by disruption of the Shu complex is observed in cells lacking TOP3 and RMI1 (Mankouri, Ngo and Hickson 2007). Moreover, X-molecules are absent when rad51Δ or rad54Δ are also disrupted in sgs1Δ shu1Δ cells supporting the notion that Rad51 is responsible for X-molecule formation (Mankouri, Ngo and Hickson 2007). These results are consistent with a model in which the Shu complex promotes assembly of early recombination intermediates in repair of replicative damage that are then dissolved by the Sgs1-Top3-Rmi1 complex. Therefore, one possibility is that the suppression of sgs1Δ HU sensitivity by Shu complex disruption may be due to limiting accumulation of the toxic DNA intermediates that Sgs1 is needed to resolve.

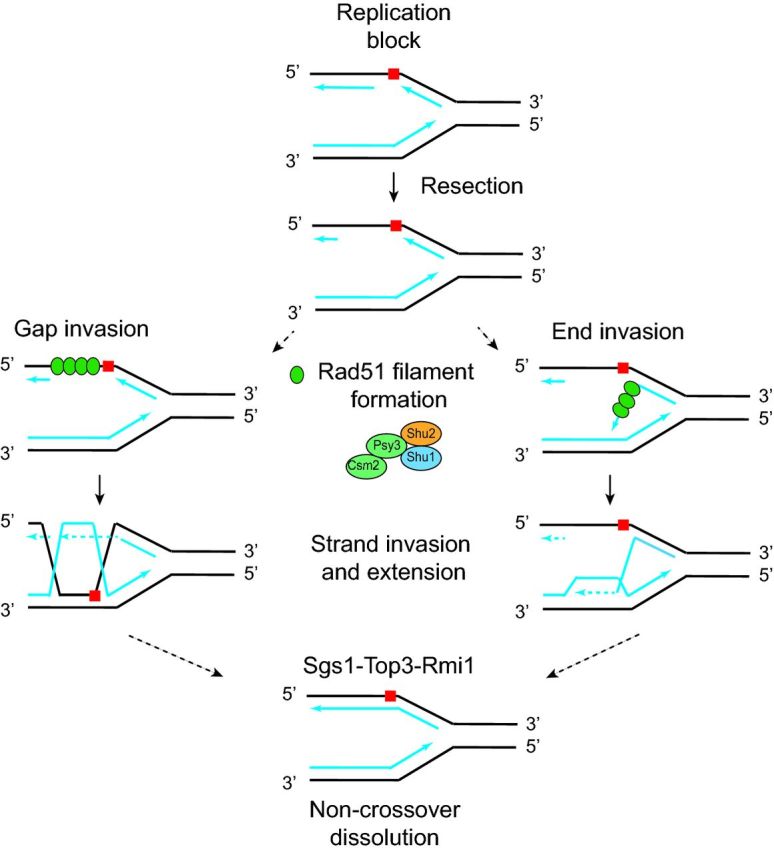

In addition to the Sgs1-Top3-Rmi1 complex's role in dissolution of MMS-induced X-structures, the Smc5/6 complex and Esc2 are also important for dissolution of these molecules (Choi et al.2010). Interestingly, like sgs1Δ, top3Δ and rmi1Δ mutants, shu1Δ also reduces the MMS sensitivity and X-molecules that accumulate in smc6–P4, smc6-56 and esc2Δ cells (Choi et al.2010). Disruption of the Shu complex is not unique in its role in preventing formation of MMS-induced X-structures. Mutations in the DNA helicase mph1 as well as the error-free PRR enzyme mms2 also alleviate the MMS sensitivity and X-molecule accumulation observed in smc6-P4 and esc2Δ mutants (Choi et al.2010). However, genetic analysis indicates that the Shu complex is likely suppressing X-molecule accumulation through a different mechanism than mph1 or mms2. For example, the MMS sensitivity of shu1Δ when combined with either an mph1Δ or mms2Δ mutation results in an increased growth defect when compared to the single mutants (Choi et al.2010). Therefore, the Shu complex is likely generating recombination intermediates during replication through a different mechanism than error-free PRR, consistent with reported synthetic growth defects when Shu complex mutants are combined with PRR mutants (Choi et al.2010; Godin et al.2016). One possibility is that specific DNA repair proteins are important to respond to different structures generated during replication fork stalling or collapse. Alternatively, these repair proteins may recognize similar DNA intermediates but may repair them through different mechanisms depending on the context. Despite increasing evidence for a role of the Shu complex in HR during replicative damage (Fig. 2), more detailed functional analysis is needed to determine the specific lesions the Shu complex responds to and in which recombination processes (i.e. fork reversal, template switching, gap filling) it engages in. For example, the Shu complex may aid Rad51 filament formation at a replication fork-blocking lesion at a ssDNA gap or end (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Model for possible roles for the Shu complex in HR at a stalled replication fork. A replication fork encounters a lesion (red square), which can be bypassed using error-free HR. After resection of the lagging strand, two models are shown. On the left, ssDNA gap invasion is diagrammed where Rad51 filaments form on the ssDNA gap at the damaged fork. The Shu complex is important for promoting Rad51 filament formation at the ssDNA gap. On the right, single-stranded end invasion is diagrammed where Rad51 filaments form on the blocked lagging strand end. The Shu complex promotes Rad51 filament formation at the ssDNA end. In both cases, the Rad51 filaments invade and extend the undamaged and newly synthesized opposing strand (i.e. bottom blue line). The intermediate structures formed during strand invasion are resolved by Sgs1-Top3-Rmi1 leading to non-crossover dissolution. In addition to these proposed mechanisms for Shu complex function, the Shu complex may also function at one-ended DSBs that arise during repair of replicative damage (not shown; Godin et al.2016). This figure is adapted from Godin, Sullivan and Bernstein 2016.

THE Shu COMPLEX IN MEIOTIC RECOMBINATION REPAIR

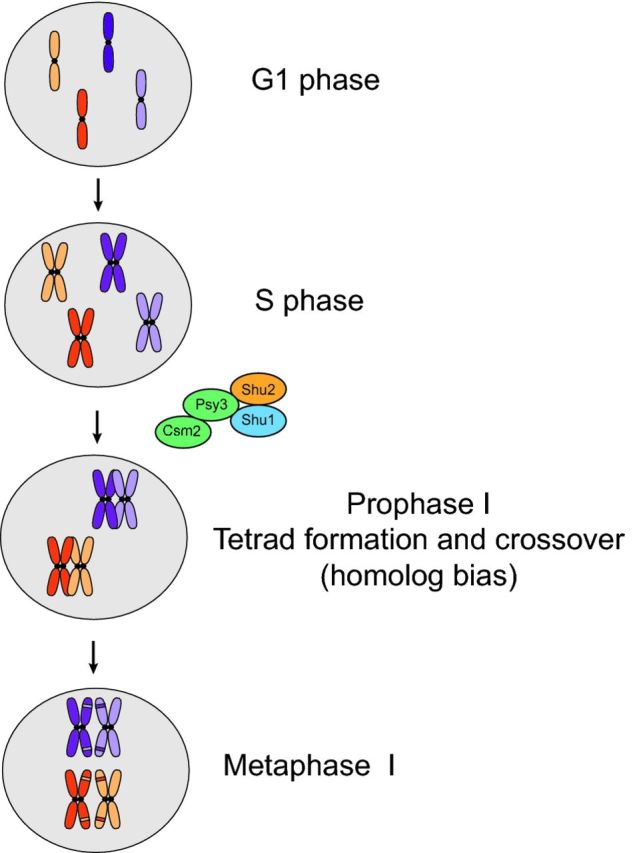

In addition to the Shu complex's function in mitotic HR, the Shu complex is also important for repair of meiotic DSBs induced by the endonuclease Spo11, a topoisomerase-like protein (Fig. 4). In contrast to mitotic recombination, where the sister chromatid is primarily used as a template, meiotic recombination favors that the homologous chromosome is used for repair. Use of the homolog is essential for proper chromosome segregation in the first meiotic division and ensures genetic diversity in the meiotic progeny (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Role of the Shu complex in meiotic recombination. Meiotic recombination during prophase I preferentially occurs between homologous chromosomes (depicted in dark and light orange and dark and light purple chromosomes, respectively). The Shu complex promotes homolog bias during meiosis. This bias ensures proper chromosome segregation following metaphase I in the first meiotic division and contributes to genetic diversity in the meiotic progeny (represented as a different color patch in each sister chromatid).

The first evidence for a role of the Shu complex in meiosis came from a genetic screen for chromosome missegregation mutants by visualizing segregation of a GFP-tagged chromosome (Rabitsch et al.2001). This screen identified csm2Δ cells as exhibiting chromosome segregation defects and decreased spore viability. Therefore, CSM2 was named for its defect in chromosome segregation [chromosome segregation mutant 2 (Rabitsch et al.2001)]. Similar to csm2Δ cells, decreased spore viability has also been observed for shu1Δ, shu2Δ and psy3Δ mutants (Hong et al.2013; Sasanuma et al.2013; Godin et al.2015).

Meiotic recombination intermediates formed between sister and homologous chromosomes at a HIS-LEU2 DSB recombination hotspot can be analyzed by separating the recombination products by one- and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (Kim et al.2010). Using this assay, multiple groups observed that SHU1, PSY3 or CSM2 deletion mutants exhibit reduced interhomolog crossovers and non-crossovers but increased intersister dHJs suggesting that the Shu complex assists in promoting meiotic homolog bias (Hong and Kim 2013; Hong et al.2013; Sasanuma et al.2013). For example, csm2Δ cells form up to 10-fold more intersister joint molecules (Sasanuma et al.2013). shu1 and psy3 mutants also exhibit slower meiotic progression (Hong and Kim 2013; Hong et al.2013). Together, these findings further support that the Shu complex is required for meiotic interhomolog recombination (Fig. 4). Interestingly, ChIP analyses of meiotic recombination hotspots reveal that psy3Δ and shu1Δ mutants abolish Rad51 recruitment to these hotspots, but have no effect on the binding of the meiosis-specific recombinase Dmc1 (Sasanuma et al.2013). Therefore, the Shu complex specifically regulates meiotic recombination through a Rad51-dependent mechanism. An interesting observation is that csm2 and psy3 mutants show more severe meiotic phenotypes than do shu1 or shu2 mutants (i.e. spore viability, meiotic recombination) (Sasanuma et al.2013; Godin et al.2015), while in mitotic cells all single mutants are comparable in their phenotypic outcomes. Considering that the Csm2-Psy3 heterodimer is also more important than Shu1-Shu2 for Rad51 filament formation in vitro (Gaines et al.2015), this suggests that Csm2-Psy3's role in meiosis is to regulate Rad51 filament formation, whereas its function in replicating (i.e. mitotic) cells could be different.

EXPLORING OTHER Shu COMPLEX FUNCTIONS AT THE RIBOSOMAL DNA, IN REGULATING Srs2, AND AT TELOMERES

The Shu complex also has a role in recombination at the ribosomal DNA (rDNA). When the rDNA becomes unstable by disruption of the UAF complex (such as a uaf30Δ cell), hyper-recombination of the rDNA is observed. Uaf30 is member of a nucleolar UAF complex that promotes rDNA transcription (Siddiqi et al.2001). In the absence of the UAF complex, rDNA transcription is reduced, and cells compensate by expanding the number of their rDNA repeats via a recombination-dependent mechanism. Therefore, uaf30Δ mutants have a rDNA hyper-recombination phenotype and exhibit increasing numbers of rDNA repeats over time (Bernstein et al.2013). The increased rDNA recombination observed in uaf30Δ cells leads to cell lethality when SHU1 is overexpressed (Bernstein et al.2011). Furthermore, shu1Δ uaf30Δ double mutants exhibit reduced rDNA copy number and rDNA recombination compared to uaf30Δ cells suggesting that Shu1 regulates the rDNA hyper-recombination of uaf30Δ cells. Shu1 regulates rDNA recombination in two different manners. First, Shu1 regulates Rad52 localization to the nucleolus, where the rDNA resides. Secondly, Shu1 negatively regulates the localization of the anti-recombinase Srs2 to DSBs in rDNA (Bernstein et al.2011, 2013). Srs2 is a DNA helicase that negatively regulates Rad51 (Krejci et al.2003; Veaute et al.2003). This negative regulation of Srs2 by Shu1 is not restricted to the rDNA and is also observed by decreased YFP-Srs2 focus formation at a fluorescently labeled inducible I-SceI endonuclease cut site (Bernstein et al.2011). It remains unknown how Shu1 negatively regulates Srs2. However, a physical Y2H interaction was observed between Shu2 and Srs2, and this interaction is also conserved in Saccharomyces pombe (Uetz et al.2000; Martin et al.2006). Moreover, in fission yeast the Shu2 homolog, sws1Δ, suppresses srs2Δ CPT sensitivity suggesting that there is a physical and genetic interaction between these proteins (Martin et al.2006). Unlike mitotic DNA repair, the Shu complex's negative regulation of Srs2 is not observed in meiotic cells (Hong and Kim 2013; Sasanuma et al.2013). These results suggest that the genetic and physical interaction between the Shu complex and Srs2 is likely context specific.

A role for the Shu complex in telomere recombination has also been investigated. However, it appears that the Shu complex does not normally play a role at telomeric loci (van Mourik et al.2016). In yeasts that reach a critically short telomere length, a subset of cells, referred as ‘survivors’, can overcome senescence by using recombination mechanisms to maintain their telomeres (Lundblad and Blackburn 1993; Nakamura, Cooper and Cech 1998). Deletion of the Shu genes does not affect the rates of senescence or survivor formation in telomerase-positive or -negative cells that lack the telomerase components EST2 or TLC1 (van Mourik et al.2016). In addition, SHU1 deletion does not rescue the rapid senescence phenotype observed in est2Δ sgs1Δ cells (van Mourik et al.2016). In contrast, in cdc9-1 mutants, which are defective in DNA ligase I and characterized by long telomeres, deletion of PSY3 partially suppressed telomere elongation (Vasianovich, Harrington and Makovets 2014). It seems likely that the Shu complex does not normally play a role in telomere maintenance but perhaps under specific cellular stresses, such as with a cdc9-1 mutant, is a function observed.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE TWO Rad51 PARALOG-CONTAINING SUB-COMPLEXES (Rad55-Rad57 VERSUS Shu COMPLEX)

Although both the Shu complex and Rad55-Rad57 consist of Rad51 paralogs and are important for DSB repair, important differences between these two Rad51 paralog sub-complexes exist. As mentioned earlier, rad55Δ and rad57Δ mutants are sensitive to a wider range of DNA-damaging agents (IR, HU, UV, CPT, cisplatin and MMS) than the Shu complex mutants (MMS, CPT, cisplatin) (Johnson and Symington 1995; Herzberg et al.2006; Valencia-Burton et al.2006; Mozlin, Fung and Symington 2008; Godin et al.2016). RAD55 and RAD57 mutants are significantly more deficient than Shu complex mutants for mating-type switching, sporulation and gene conversion (Johnson and Symington 1995; Rabitsch et al.2001; Signon et al.2001; Godin et al.2013, 2015; Hong and Kim 2013; Sasanuma et al.2013). While both Rad55-Rad57 and the Shu complex stimulate Rad51 filament formation in the presence of Rad52 (Sung 1997b; Gasior et al.1998; Sugawara, Wang and Haber 2003; Gaines et al.2015), Rad55-Rad57 has an additional role in stimulating Rad51-mediated strand exchange (Sung 1997b; Sugawara, Wang and Haber 2003). The Shu complex function in strand exchange has not been investigated. Rad55-Rad57 directly interacts with Rad51, via Rad55, but this is not observed with the Shu complex where this interaction is bridged through Rad55-Rad57 (Johnson and Symington 1995; Sung 1997b; Gaines et al.2015). Suggesting that Rad55-Rad57 and the Shu complex exhibit unique functions, overexpression of RAD51 can suppress many of the defects observed in rad55Δ or rad57Δ cells but not in csm2Δ or psy3Δ mutants (Mozlin, Fung and Symington 2008; Godin et al.2013). Both Rad55-Rad57 and Shu complex member, Shu1, have additional roles in promoting Rad51 by negatively regulating the Srs2 anti-recombinase (Fung, Mozlin and Symington 2009; Bernstein et al.2011; Liu et al.2011a), although the mechanisms may be different.

While both the Shu complex and Rad55-Rad57 are important for repair of damaged replication forks, it has been proposed that Rad55-Rad57 have an HR-independent function at a replication fork where spontaneous sister chromatid recombination at a stalled fork originates from a single-stranded gap and not a direct DSB (Mozlin, Fung and Symington 2008). Similar to Shu complex mutants, deletion of RAD55 also suppresses the sgs1Δ-dependent X-structures formed after MMS exposure (Vanoli et al.2010). In the case of the Shu complex, it is likely that the Shu complex plays a more important role at the fork and not at canonical HR substrates. Therefore, due to the dual role of Rad55-Rad57 at many types of DNA lesions, the rad55Δ and rad57Δ mutant defects are much more severe.

CONSERVATION OF THE Shu COMPLEX IN OTHER SPECIES

Evolutionary analyses of Shu2 revealed that Shu2 orthologs are conserved across eukaryotes from archaea to humans (Godin et al.2015). Furthermore, by measuring evolutionary rate co-variation (ERC) that determines the rate at which proteins are evolving, it has been demonstrated that functionally interacting and related proteins exhibit high ERC values (Clark, Alani and Aquadro 2012). Using these analyses of budding yeast Shu2 and Drosophila Sws1, it was revealed that the members of the Shu complex have elevated ERC values, supporting their co-functionality and highlighting shared evolutionary pressures amongst these proteins. Shu2/Sws1 also exhibit conserved functional relationships with meiotic proteins, the Rad51 paralogs, and with Srs2 (Godin et al.2015). The identification of Shu2/Sws1 protein family orthologs throughout eukaryotes also suggests an ancient origin and supports highly conserved roles for these proteins in Rad51 regulation (Godin et al.2015).

Given the evolutionary studies, it is not surprising that members of the Shu complex have now been identified in other species such as Caenorhabditis elegans and humans (Liu et al.2011b; McClendon et al.2016) (Table 1). In C. elegans, the Shu complex includes Shu2/SWS1 protein, SWS-1, and the RAD-51 paralogs, RFS-1 and RIP-1 (Taylor et al.2015; McClendon et al.2016). The sws-1 null mutants exhibit a mutator phenotype, sensitivity to a broad range of DSB-inducing agents (particularly CPT) have impaired mitotic RAD-51 foci formation, and exhibit meiotic defects (McClendon et al.2016). Indicating a conserved role for the worm Shu complex in DNA recombination, sws-1 mutants exhibit a 4-fold increase in male frequency compared to wild-type worms, which results from non-disjunction of the X-chromosome. Similar to what has been observed in yeast, worm SWS-1 interacts with the RAD-51 paralog RIP-1 by Y2H, and this interaction requires the SWIM domain of SWS-1 and the Walker B motif of RIP-1 (McClendon et al.2016). Furthermore, RIP-1 bridges an interaction between SWS-1 and the other worm RAD-51 paralog, RFS-1 (McClendon et al.2016). Together, these data suggest that the Shu complex is conserved in worms where it has both meiotic and mitotic HR functions, likely in regulating RAD-51.

In humans, Martin et al. (2006) were the first to describe a Shu2/SWS1 homolog, ZSWIM7, which they renamed SWS1 (SWIM domain containing an Srs2-interacting protein 1). Like the yeast and worm Shu2/SWS1 family members, human SWS1 co-immunoprecipitates the RAD51 paralogs (such as XRCC2 and RAD51D) in HeLa cells (Martin et al.2006). Furthermore, SWS1 knockdown by RNAi impairs both spontaneous and MMS-induced RAD51 foci formation indicating a conserved function for the Shu complex in RAD51 regulation (Martin et al.2006). To identify additional human Shu complex members, Liu et al. (2011b) used a tandem affinity purification approach to isolate potential binding partners of SWS1 and identified a novel protein which they named SWSAP1 for hSWS1-associated protein 1. SWSAP1 is a highly divergent novel RAD51 paralog, bearing similarity to archaeal RadA and containing ATPase activity through its conserved Walker A and Walker B motifs (Liu et al.2011b). Similar to SWS1 knockdown, siSWSAP1 knockdown cells are MMS sensitive and have decreased RAD51 foci and fewer gene-conversion events. Like human cells, DT40 chicken cell lines with an SWS1 gene disruption show increased sensitivity to cisplatin and a decrease in IR-induced RAD51 foci (Qing et al.2011). Interestingly, SWS1 disruption in a brca2-null DT40 background yields similar sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents as a brca2-null, implying that SWS1 and BRCA2 are in the same epistasis group. These results are consistent with yeast findings regarding the epistasis between RAD52, which in yeast loads Rad51 onto ssDNA, and the yeast Shu complex (Shor, Weinstein and Rothstein 2005; Mankouri, Ngo and Hickson 2007; Gaines et al.2015).

Both genetic and physical evidence show that SWS1 and SWSAP1 form a complex together (Table 1). In agreement with SWS1 and SWSAP1 forming a complex, double siRNA knockdown of SWS1 and SWSAP1 yields similar phenotypes as the individual knockdowns (Liu et al. 2011b). Interestingly, the ATPase activity of SWSAP1 is required for its HR function but not for its binding to SWS1 or to ssDNA (Liu et al. 2011b). Even though SWS1 and SWSAP1 can co-immunoprecipitate the other human RAD51 paralogs in vitro and in vivo (Martin et al.2006; Liu et al. 2011b), there is currently conflicting evidence as to which of these other RAD51 paralogs form the human Shu complex. Whereas Martin et al. (2006) found that SWS1 co-immunoprecipitates RAD51D and XRCC2, Liu et al. (2011b) demonstrated that SWSAP1 co-immunoprecipitates RAD51, RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D and XRCC3, but not XRCC2. Therefore, other than SWS1 and SWSAP1, the additional components of the human Shu complex remain unclear.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

By using budding yeast as a model, the highly conserved Shu complex is now known to be an important HR regulator. Although its specific functions during HR are just beginning to be revealed, the Shu complex regulates Rad51 filament assembly, likely in repair of replicative damage and during meiosis (Table 1) (Ball et al.2009; Sasanuma et al.2013; Gaines et al.2015; McClendon et al.2016). Misregulation of human RAD51 filament assembly is associated with cancer predisposition. Therefore, it is not surprising that a new report has now linked mutations in the human SWS1 protein with cancer. For example, Spier et al. (2016) published the first report listing a member of the human Shu complex, SWS1, as a potential candidate for unexplained colorectal adenomatous polyposis. Exome sequencing data from a small cohort of patients revealed a homozygous mutation in SWS1, located within the SWIM domain, that gives rise to a frameshift deletion (Spier et al.2016). This finding underscores the importance of RAD51 regulation in genome integrity and cancer prevention.

The primary sensitivity of yeast Shu mutants to the methylating agent MMS suggests that the Shu complex may be of particular importance in HR that occurs at sites of replication-induced DNA damage such as stalled or collapsed replication forks (Figs 2 and 3). Consistent with this finding, sws-1 null worms are most sensitive to the topoisomerase inhibitor, CPT (McClendon et al.2016). These results suggest that the Shu complex may have evolved to be important to repair-specific replication-blocking lesions whereas the other Rad51 paralogs may be more general HR factors. How the Shu complex is recruited to replication-associated DNA damage and its function at the replication fork remains to be determined. Given that many chemotherapeutic agents rely on cell death of highly replicating cancer cells, understanding repair of replication-blocking lesions and exploiting these pathways has important therapeutic applications. Toward this aim, our lab has been using yeast genetics to pinpoint the exact lesions that the Shu complex responds to by individually disrupting BER factors (Godin et al.2016). This type of synthetic lethal strategy has the potential to identify novel targets for HR-deficient tumors. Given that the Shu complex disruption is better tolerated than disruption of other HR factors, such as the canonical RAD51 paralogs, perhaps Shu complex inhibitors could be an alternative therapeutic approach. For example, human RAD52 is non-essential, and RAD52 inhibitors are now beginning to be exploited clinically (Lok and Powell 2012; Huang et al.2016). As more HR-deficient tumors come to light and the issue of chemotherapeutic resistance increases, uncovering additional novel druggable targets and understanding the basic mechanisms of DNA repair will become essential. Yeast provides an excellent resource to study DNA repair, and work on the Shu complex that originated in yeast has shed light on its mammalian counterparts and will continue to do so.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Godin, Meghan Sullivan and Benjamin Herken for their comments on the manuscript.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (ES024872), a V Scholar Grant from the V Foundation for Cancer Research and a Research Scholar Grant RSG-16-043-01–DMC from the American Cancer Society.

Conflict of interest. None declared.

REFERENCES

- Albala JS, Thelen MP, Prange C, et al. Identification of a novel human RAD51 homolog, RAD51B. Genomics. 1997;46:476–9. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allers T, Lichten M. Differential timing and control of noncrossover and crossover recombination during meiosis. Cell. 2001;106:47–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton TM, Hickson ID. Yeast as a model system to study RecQ helicase function. DNA Repair. 2010;9:303–14. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball LG, Zhang K, Cobb JA, et al. The yeast Shu complex couples error-free post-replication repair to homologous recombination. Mol Microbiol. 2009;73:89–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein KA, Juanchich A, Sunjevaric I, et al. The Shu complex regulates Rad52 localization during rDNA repair. DNA Repair. 2013;12:786–90. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein KA, Reid RJ, Sunjevaric I, et al. The Shu complex, which contains Rad51 paralogues, promotes DNA repair through inhibition of the Srs2 anti-recombinase. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:1599–607. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D, Foiani M. Maintaining genome stability at the replication fork. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2010;11:208–19. doi: 10.1038/nrm2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braybrooke JP, Spink KG, Thacker J, et al. The RAD51 family member, RAD51L3, is a DNA-stimulated ATPase that forms a complex with XRCC2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29100–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill SJ, Stillman B. Replication factor-A from Saccharomyces cerevisiae is encoded by three essential genes coordinately expressed at S phase. Gene Dev. 1991;5:1589–600. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright R, Tambini CE, Simpson PJ, et al. The XRCC2 DNA repair gene from human and mouse encodes a novel member of the recA/RAD51 family. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3084–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.13.3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos SJ, Heyer WD. Functions of the Snf2/Swi2 family Rad54 motor protein in homologous recombination. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1809:509–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cejka P. DNA end resection: nucleases team up with the right partners to initiate homologous recombination. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:22931–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.675942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cejka P, Cannavo E, Polaczek P, et al. DNA end resection by Dna2-Sgs1-RPA and its stimulation by Top3-Rmi1 and Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2. Nature. 2010;467:112–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang DJ, Cimprich KA. DNA damage tolerance: when it's OK to make mistakes. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:82–90. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M, Bellaoui M, Zhang C, et al. RMI1/NCE4, a suppressor of genome instability, encodes a member of the RecQ helicase/Topo III complex. EMBO J. 2005;24:2024–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Szakal B, Chen Y-H, et al. The Smc5/6 complex and Esc2 influence multiple replication-associated recombination processes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2306–14. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-01-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark NL, Alani E, Aquadro CF. Evolutionary rate covariation reveals shared functionality and coexpression of genes. Genome Res. 2012;22:714–20. doi: 10.1101/gr.132647.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans B, Griffin CS, Maconochie M, et al. Xrcc2 is required for genetic stability, embryonic neurogenesis and viability in mice. EMBO J. 2000;19:6675–85. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosanjh MK, Collins DW, Fan W, et al. Isolation and characterization of Rad51C, a new member of the RAD51 family of related genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1179–84. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.5.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung CW, Mozlin AM, Symington LS. Suppression of the double-strand-break-repair defect of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae rad57 mutant. Genetics. 2009;181:1195–206. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.100842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines WA, Godin SK, Kabbinavar FF, et al. Promotion of presynaptic filament assembly by the ensemble of S. cerevisiae Rad51 paralogues with Rad52. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7834. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Game JC, Mortimer RK. A genetic study of x-ray sensitive mutants in yeast. Mutat Res. 1974;24:281–92. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(74)90176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangloff S, McDonald JP, Bendixen C, et al. The yeast type I topoisomerase Top3 interacts with Sgs1, a DNA helicase homolog: a potential eukaryotic reverse gyrase. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8391–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasior SL, Wong AK, Kora Y, et al. Rad52 associates with RPA and functions with rad55 and rad57 to assemble meiotic recombination complexes. Gene Dev. 1998;12:2208–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannattasio M, Zwicky K, Follonier C, et al. Visualization of recombination-mediated damage bypass by template switching. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:884–92. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin S, Wier A, Kabbinavar F, et al. The Shu complex interacts with Rad51 through the Rad51 paralogues Rad55-Rad57 to mediate error-free recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:4525–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin SK, Meslin C, Kabbinavar F, et al. Evolutionary and functional analysis of the invariant SWIM domain in the conserved Shu2/SWS1 protein family from Saccharomyces cerevisiae to Homo sapiens. Genetics. 2015;199:1023–33. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.173518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin SK, Sullivan MR, Bernstein KA. Novel insights into RAD51 activity and regulation during homologous recombination and DNA replication. Biochem Cell Biol. 2016:1–12. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2016-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin SK, Zhang Z, Herken BW, et al. The Shu complex promotes error-free tolerance of alkylation-induced base excision repair products. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golmard L, Caux-Moncoutier V, Davy G, et al. Germline mutation in the RAD51B gene confers predisposition to breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:484. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MF, Woodgate R. Translesion DNA polymerases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a010363. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth P, Auslander S, Majumder MM, et al. Methylated DNA causes a physical block to replication forks independently of damage signalling, O(6)-methylguanine or DNA single-strand breaks and results in DNA damage. J Mol Biol. 2010;402:70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haracska L, Unk I, Johnson RE, et al. Roles of yeast DNA polymerases delta and zeta and of Rev1 in the bypass of abasic sites. Gene Dev. 2001;15:945–54. doi: 10.1101/gad.882301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg K, Bashkirov VI, Rolfsmeier M, et al. Phosphorylation of Rad55 on serines 2, 8, and 14 is required for efficient homologous recombination in the recovery of stalled replication forks. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8396–409. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01317-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbers FS, Wijnen JT, Hoogerbrugge N, et al. Rare variants in XRCC2 as breast cancer susceptibility alleles. J Med Genet. 2012;49:618–20. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Kim KP. Shu1 promotes homolog bias of meiotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cells. 2013;36:446–54. doi: 10.1007/s10059-013-0215-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Sung Y, Yu M, et al. The logic and mechanism of homologous recombination partner choice. Mol Cell. 2013;51:440–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Goyal N, Sullivan K, et al. Targeting BRCA1- and BRCA2-deficient cells with RAD52 small molecule inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:4189–99. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ME, Rio AG, Nicolas A, et al. A genomewide screen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for genes that suppress the accumulation of mutations. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11529–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2035018100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ira G, Malkova A, Liberi G, et al. Srs2 and Sgs1–Top3 suppress crossovers during double-strand break repair in yeast. Cell. 2003;115:401–11. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Chiba T, Ozawa R, et al. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4569–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061034498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasin M, Rothstein R. Repair of strand breaks by homologous recombination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a012740. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RD, Symington LS. Functional differences and interactions among the putative RecA homologs Rad51, Rad55, and Rad57. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4843–50. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpenshif Y, Bernstein KA. From yeast to mammals: recent advances in genetic control of homologous recombination. DNA Repair. 2012;11:781–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KP, Weiner BM, Zhang L, et al. Sister cohesion and structural axis components mediate homolog bias of meiotic recombination. Cell. 2010;143:924–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczykowski SC. An overview of the molecular mechanisms of recombinational DNA repair. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7:a016410. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci L, Van Komen S, Li Y, et al. DNA helicase Srs2 disrupts the Rad51 presynaptic filament. Nature. 2003;423:305–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov SG, Haines DC, Martin BK, et al. Loss of Rad51c leads to embryonic lethality and modulation of Trp53-dependent tumorigenesis in mice. Cancer Res. 2009;69:863–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberi G, Maffioletti G, Lucca C, et al. Rad51-dependent DNA structures accumulate at damaged replication forks in sgs1 mutants defective in the yeast ortholog of BLM RecQ helicase. Gene Dev. 2005;19:339–50. doi: 10.1101/gad.322605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Wu X, Wang Z. A full-length cDNA of hREV3 is predicted to encode DNA polymerase z for damage-induced mutagenesis in humans. Mutat Res. 1999;433:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(98)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Xin H, Zhang Y, et al. The human REV1 gene codes for a DNA template-dependent dCMP transferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4468–75. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Renault L, Veaute X, et al. Rad51 paralogues Rad55-Rad57 balance the antirecombinase Srs2 in Rad51 filament formation. Nature. 2011a;479:245–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Lamerdin JE, Tebbs RS, et al. XRCC2 and XRCC3, new human Rad51-family members, promote chromosome stability and protect against DNA cross-links and other damages. Mol Cell. 1998;1:783–93. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Wan L, Wu Y, et al. hSWS1.SWSAP1 is an evolutionarily conserved complex required for efficient homologous recombination repair. J Biol Chem. 2011b;286:41758–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.271080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok BH, Powell SN. Molecular pathways: understanding the role of Rad52 in homologous recombination for therapeutic advancement. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6400–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveday C, Turnbull C, Ramsay E, et al. Germline mutations in RAD51D confer susceptibility to ovarian cancer. Nat Genet. 2011;43:879–82. doi: 10.1038/ng.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad V, Blackburn EH. An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1- senescence. Cell. 1993;73:347–60. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90234-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova KS, Aravind L, Koonin EV. SWIM, a novel Zn-chelating domain present in bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:384–6. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankouri HW, Ngo H-P, Hickson ID. Shu proteins promote the formation of homologous recombination intermediates that are processed by Sgs1-Rmi1-Top3. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4062–73. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin V, Chahwan C, Gao H, et al. Sws1 is a conserved regulator of homologous recombination in eukaryotic cells. EMBO J. 2006;25:2564–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClendon TB, Sullivan MR, Bernstein KA, et al. Promotion of homologous recombination by SWS-1 in complex with the RAD-51 paralogs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2016;201:133–45. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.185827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meindl A, Hellebrand H, Wiek C, et al. Germline mutations in breast and ovarian cancer pedigrees establish RAD51C as a human cancer susceptibility gene. Nat Genet. 2010;42:410–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature. 2008;455:770–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen UH, Lisby M, Rothstein R. Rad52. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R676–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozlin AM, Fung CW, Symington LS. Role of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad51 paralogs in sister chromatid recombination. Genetics. 2008;178:113–26. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.082677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen JR, Nallaseth FS, Lan YQ, et al. Yeast Rmi1/Nce4 controls genome stability as a subunit of the Sgs1-Top3 complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4476–87. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4476-4487.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura TM, Cooper JP, Cech TR. Two modes of survival of fission yeast without telomerase. Science. 1998;282:493–6. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New JH, Sugiyama T, Zaitseva E, et al. Rad52 protein stimulates DNA strand exchange by Rad51 and replication protein A. Nature. 1998;391:407–10. doi: 10.1038/34950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H, Chung WH, Zhu Z, et al. Mechanism of the ATP-dependent DNA end-resection machinery from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2010;467:108–11. doi: 10.1038/nature09318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DJ, Lesueur F, Nguyen-Dumont T, et al. Rare mutations in XRCC2 increase the risk of breast cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:734–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paull TT. Making the best of the loose ends: Mre11/Rad50 complexes and Sae2 promote DNA double-strand break resection. DNA Repair. 2010;9:1283–91. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petermann E, Helleday T. Pathways of mammalian replication fork restart. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2010;11:683–7. doi: 10.1038/nrm2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petukhova G, Van Komen S, Vergano S, et al. Yeast Rad54 promotes Rad51-dependent homologous DNA pairing via ATP hydrolysis-driven change in DNA double helix conformation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29453–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan CM, Lancaster JM, Tonin P, et al. Mutation analysis of the BRCA2 gene in 49 site-specific breast cancer families. Nat Genet. 1996;13:120–2. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman DL, Schimenti JC. Midgestation lethality in mice deficient for the RecA-related gene, Rad51d/Rad51l3. Genesis. 2000;26:167–73. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200003)26:3<167::aid-gene1>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman DL, Weinberg LR, Schimenti JC. Identification, characterization, and genetic mapping of Rad51d, a new mouse and human RAD51/RecA-related gene. Genomics. 1998;49:103–11. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash R, Zhang Y, Feng W, et al. Homologous recombination and human health: the roles of BRCA1, BRCA2, and associated proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7:a016600. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S, Prakash L, Burke W, et al. Effects of the RAD52 gene on recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1980;94:31–50. doi: 10.1093/genetics/94.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qing Y, Yamazoe M, Hirota K, et al. The epistatic relationship between BRCA2 and the other RAD51 mediators in homologous recombination. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabitsch KP, Tóth A, Gálova M, et al. A screen for genes required for meiosis and spore formation based on whole-genome expression. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1001–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasanuma H, Tawaramoto MS, Lao JP, et al. A new protein complex promoting the assembly of Rad51 filaments. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1676. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She Z, Gao ZQ, Liu Y, et al. Structural and SAXS analysis of the budding yeast SHU-complex proteins. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2306–12. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara A, Ogawa T. Stimulation by Rad52 of yeast Rad51-mediated recombination. Nature. 1998;391:404–7. doi: 10.1038/34943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shor E, Gangloff S, Wagner M, et al. Mutations in homologous recombination genes rescue top3 slow growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2002;162:647–62. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.2.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shor E, Weinstein J, Rothstein R. A genetic screen for top3 suppressors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identifies SHU1, SHU2, PSY3 and CSM2: four genes involved in error-free DNA repair. Genetics. 2005;169:1275–89. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Z, Smith S, Wang L, et al. Disruption of muREC2/RAD51L1 in mice results in early embryonic lethality which can Be partially rescued in a p53(-/-) background. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8686–93. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi IN, Dodd JA, Vu L, et al. Transcription of chromosomal rRNA genes by both RNA polymerase I and II in yeast uaf30 mutants lacking the 30 kDa subunit of transcription factor UAF. EMBO J. 2001;20:4512–21. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signon L, Malkova A, Naylor ML, et al. Genetic requirements for RAD51- and RAD54-independent break-induced replication repair of a chromosomal double-strand break. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2048–56. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.6.2048-2056.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeenk G, de Groot AJ, Romeijn RJ, et al. Rad51C is essential for embryonic development and haploinsufficiency causes increased DNA damage sensitivity and genomic instability. Mutat Res. 2010;689:50–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somyajit K, Subramanya S, Nagaraju G. RAD51C: a novel cancer susceptibility gene is linked to Fanconi anemia and breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:2031–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spier I, Kerick M, Drichel D, et al. Exome sequencing identifies potential novel candidate genes in patients with unexplained colorectal adenomatous polyposis. Fam Cancer. 2016;15:281–8. doi: 10.1007/s10689-016-9870-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Onge RP, Mani R, Oh J, et al. Systematic pathway analysis using high-resolution fitness profiling of combinatorial gene deletions. Nat Genet. 2007;39:199–206. doi: 10.1038/ng1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara N, Wang X, Haber JE. In vivo roles of Rad52, Rad54, and Rad55 proteins in Rad51-mediated recombination. Mol Cell. 2003;12:209–19. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Zaitseva EM, Kowalczykowski SC. A single-stranded DNA-binding protein is needed for efficient presynaptic complex formation by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad51 protein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7940–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung P. Function of yeast Rad52 protein as a mediator between replication protein A and the Rad51 recombinase. J Biol Chem. 1997a;272:28194–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung P. Yeast Rad55 and Rad57 proteins form a heterodimer that functions with replication protein A to promote DNA strand exchange by Rad51 recombinase. Gene Dev. 1997b;11:1111–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.9.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwaki N, Klare K, Tarsounas M. RAD51 paralogs: roles in DNA damage signalling, recombinational repair and tumorigenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:898–905. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symington LS. End resection at double-strand breaks: mechanism and regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6:a016436. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symington LS, Rothstein R, Lisby M. Mechanisms and regulation of mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2014;198:795–835. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.166140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Li X, Liu Y, et al. Structural analysis of Shu proteins reveals a DNA binding role essential for resisting damage. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:20231–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.334698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MRG, Spirek M, Chaurasiya KR, et al. Rad51 paralogs remodel pre-synaptic Rad51 filaments to stimulate homologous recombination. Cell. 2015;162:271–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebbs RS, Zhao Y, Tucker JD, et al. Correction of chromosomal instability and sensitivity to diverse mutagens by a cloned cDNA of the XRCC3 DNA repair gene. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6354–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorlacius S, Olafsdottir G, Tryggvadottir L, et al. A single BRCA2 mutation in male and female breast cancer families from Iceland with varied phenotypes. Nat Genet. 1996;13:117–9. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetz P, Giot L, Cagney G, et al. A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2000;403:623–7. doi: 10.1038/35001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Burton M, Oki M, Johnson J, et al. Different mating-type-regulated genes affect the DNA repair defects of Saccharomyces RAD51, RAD52 and RAD55 mutants. Genetics. 2006;174:41–55. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.058685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Mourik PM, de Jong J, Agpalo D, et al. Recombination-mediated telomere maintenance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is not dependent on the Shu complex. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanoli F, Fumasoni M, Szakal B, et al. Replication and recombination factors contributing to recombination-dependent bypass of DNA lesions by template switch. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasianovich Y, Harrington LA, Makovets S. Break-induced replication requires DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of Pif1 and leads to telomere lengthening. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz F, Hanenberg H, Schuster B, et al. Mutation of the RAD51C gene in a Fanconi anemia-like disorder. Nat Genet. 2010;42:406–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veaute X, Jeusset J, Soustelle C, et al. The Srs2 helicase prevents recombination by disrupting Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments. Nature. 2003;423:309–12. doi: 10.1038/nature01585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JD, Barber LJ, Petalcorin MI, et al. Replication blocking lesions present a unique substrate for homologous recombination. EMBO J. 2007;26:3384–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JD, Muzzini DM, Petalcorin MI, et al. Overlapping mechanisms promote postsynaptic RAD-51 filament disassembly during meiotic double-strand break repair. Mol Cell. 2010;37:259–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, et al. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature. 1995;378:789–92. doi: 10.1038/378789a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HI, Brown JA, Dorie MJ, et al. Genome-wide identification of genes conferring resistance to the anticancer agents cisplatin, oxaliplatin, and mitomycin C. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3940–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Hickson ID. The Bloom's syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature. 2003;426:870–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt HD, West SC. Holliday junction resolvases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6:a023192. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a023192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Ball L, Chen W, et al. The yeast Shu complex utilizes homologous recombination machinery for error-free lesion bypass via physical interaction with a Rad51 paralogue. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Li Q, Fan J, et al. The BRCA2 homologue Brh2 nucleates RAD51 filament formation at a dsDNA-ssDNA junction. Nature. 2005;433:653–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Chung WH, Shim EY, et al. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell. 2008;134:981–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]