Abstract

The benign acute childhood myositis presents as a marked and painful oedema of leg muscles in the days following a viral illness. This disease is often considered as occurring only in children. We report the case of a 32-year-old patient who presented with severe pain and oedema of both legs associated with motor deficit of lower extremities. He suffered from a grippal syndrome for 4 days. Creatine kinase blood level rose up to 39 394 IU/L (n<200) and a muscle biopsy of left tibialis anterior found necrosisand regeneration of myocytes without inflammatory infiltrates. All clinical and paraclinical abnormalities spontaneously disappeared in a few days. This case illustrates that a disorder similar to benign acute childhood myositis may occur in adult patients. Muscle biopsy might be avoided in typical cases because of the favourable evolution.

Keywords: influenza, muscle disease

Background

Benign acute childhood myositis is a disorder characterised by severe bilateral calf pain, difficulty for walking and a marked rhabdomyolysis in the days following a viral illness.1 2 The prognosis is excellent as patients present with spontaneous normalisation of symptoms and serum creatine kinase (CK) levels.3 4 It is well known by paediatricians that invasive investigations are not useful.5 This entity is often considered as affecting exclusively the children and physicians may be unaware that adult cases may also occur. Here, we report the case of an adult presenting with a similar disorder.

Case presentation

A 32-year-old man was addressed because of severe pain and oedema of both calves who had appeared the day before. He had no personal or familial medical history, especially no history of neuromuscular disease or exercise intolerance. He took no medication. He reported an episode of fever, rhinorrhoea and diffuse myalgia in the 4 days preceding the onset of lower limbs pain (figure 1). He mentioned no unusual recent physical activity. Clinical examination showed markedly swollen calves and bilateral weakness of dorsal and plantar foot flexion evaluated at 3/5 on the Medical Research Council scale. Walking abilities were severely impaired by weakness and oedema of legs. Reflexes and sensory examination were normal. There was no other clinical abnormality.

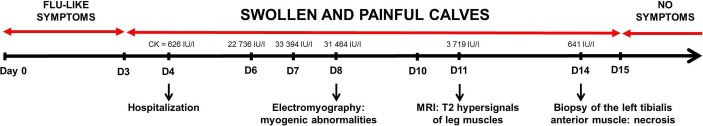

Figure 1.

Timeline of symptoms and main investigations.

Investigations

Serum CK level was increased at 39 394 IU/L (n<200). Blood tests, including especially blood cell count, anti-nuclear antibodies, plasma ACE, thyroid-stimulating hormone, renal function, hepatitis B and C virus serology, HIV serology, Borrelia burgdorferi serology and C reactive protein were normal. Bilateral sural, tibial and peroneal nerves conduction studies were normal. Electromyographic examination showed myogenic abnormalities, that is, short duration, low amplitude motor unit action potentials with early recruitment in tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles and not in vastus lateralis and deltoid muscles. Muscle MRI revealed bilateral leg muscles abnormalities (figure 2). Left tibialis anterior muscle biopsy found necrosis and regeneration, normal major histocompatibility complex class 1 (MHC1) expression and no inflammatory infiltrates (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Muscle MRI of legs (T2 sequences). Hyperintensities of the right tibialis anterior (1), right flexor digitorum longus (2), left tibialis anterior (3) and left lateral gastrocnemius (4) muscles surrounded by subcutaneous oedema (asterisk).

Figure 3.

Left tibalis anterior muscle biopsy. Fibres in postnecrosis regeneration (H&E, A) without abnormal sarcolemmal expression of major histocompatibility complex class I (immunohistochemistry, B).

Differential diagnosis

Preserved reflexes, absence of cognitive, cerebellar or pyramidal dysfunction and normal nerve conduction studies argued against a nervous system disease such as encephalitis, myelitis or Guillain-Barré syndrome. Electromyographic examination and MRI results as well as markedly elevated CK levels suggested a muscle rather a vascular or articular disease. An extensive work-up detected no abnormalities consistent with an autoimmune disease or an infection by HIV, hepatitis B and C viruses and Lyme disease. The patient did not travel in tropical areas where he may have been exposed to dengue virus. No toxic or drug exposure was recorded and it would have not affected only the leg muscles. The histological findings were not in favour of an inflammatory or genetic myopathy. Metabolic diseases that impair the muscular energy production are usually considered after at least two episodes of rhabdomyolysis and are not associated with a specific involvement of leg muscles.2 4 He had neither a previous episode of rhabdomyolysis nor a familial history of myopathy. Finally, acute benign myositis of viral origin was diagnosed based on the preceding flu-like symptoms, the involvement of distal lower limbs muscles and the spontaneous recovery. The search for type A and B influenza virus using an enzyme immunofluorescence assay in nasopharyngeal secretions was negative, but it was performed 15 days after the onset of flu-like symptoms.

Outcome and follow-up

Recovery was spontaneously complete, with CK levels normalising and clinical symptoms disappearing in a few days. No new episode of myositis was observed in the 36-month period of follow-up.

Discussion

In this case, the diagnosis of benign viral myositis was initially not considered because it was often seen as an exclusively paediatric disease.1–3 A muscle biopsy was thus performed whereas it is not useful for the diagnosis of benign acute childhood myositis.5 However, we noted after the recovery that our patient had the typical symptoms and course of benign acute childhood myositis especially the calf oedema and myositis of leg muscles. An inflammatory or genetic myopathy would not have recovered spontaneously without relapses. Histologic analysis showed no specific sign of genetic or inflammatory disease. The causal infectious agent was not identified but the search for viral particle was performed after the symptomatic phase when the germs had been probably eliminated. In clinical practice, the causal infectious agent is also rarely identified in affected children and the diagnosis of benign acute childhood myositis is usually based on the chronology of symptoms onset in the days following a viral infection.1–4

A closer look at biomedical literature showed that benign acute childhood myositis denomination was misleading. In its initial report of 74 cases of ‘myalgia cruris epidemica’, Lundberg described 70 children and 4 adults with acute calf pain and rhabdomyolysis occurring after an influenza virus epidemic.6 Later, the less common adult cases were overlooked and ‘myalgia cruris epidemica’ was renamed benign acute childhood myositis.1 Studies on this disease were thereafter conducted by paediatricians who did not include adult cases. Such patients were, therefore, not mentioned in recent medical literature.

The most likely mechanism of benign acute childhood myositis is a direct invasion of muscle cells by viral particles while an autoimmune reaction is less probable.7 Influenza virus is the most frequent cause of this disease, and it has been demonstrated that influenza virus can directly infect cultured human muscle cells.8 The particular involvement of distal lower limbs muscles and the marked calf oedema is well documented in the literature but is not clearly explained. These clinical features are helpful to distinguish benign acute myositis from idiopathic inflammatory myopathies in which proximal muscles are predominantly involved.1 2

Our case may be useful to remind that benign acute myositis is possible in adults and that a muscle biopsy might be avoided in such typical cases.

Learning points.

Benign acute childhood myositis is a disorder with a favourable evolution without treatment nor the need of invasive investigations.

It is often considered as a paediatric disorder and a similar affection in adult patients may be misdiagnosed.

Our case shows an example of this occurrence in an adult and suggests that useless investigations especially muscle biopsy should be avoided in typical cases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Bernard Goichot (Médecine Interne, Hopital de Hautepierre, Hopitaux Universitaires de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France) for his valuable help and advices.

Footnotes

Contributors: J-BC participated to conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis, drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content. CD participated to acquisition of data and analysis, revised the article critically for important intellectual content. BL participated to acquisition of data and analysis, drafted and revised the article critically for important intellectual content. AE-L participated to conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis, drafted and revised the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: J-BC reports hospitality fees from LFB Laboratory, Grifols and CSL Behring and speaker fees from CSL-Behring.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Mackay MT, Kornberg AJ, Shield LK, et al. Benign acute childhood myositis: laboratory and clinical features. Neurology 1999;53:2127–31. 10.1212/WNL.53.9.2127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zafeiriou DI, Katzos G, Gombakis N, et al. Clinical features, laboratory findings and differential diagnosis of benign acute childhood myositis. Acta Paediatr 2000;89:1493–4. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2000.tb02783.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agyeman P, Duppenthaler A, Heininger U, et al. Influenza-associated myositis in children. Infection 2004;32:199–203. 10.1007/s15010-004-4003-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferrarini A, Lava SA, Simonetti GD, et al. Influenzavirus B-associated acute benign myalgia cruris: an outbreak report and review of the literature. Neuromuscul Disord 2014;24:342–6. 10.1016/j.nmd.2013.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neocleous C, Spanou C, Mpampalis E, et al. Unnecessary diagnostic investigations in benign acute childhood myositis: a case series report. Scott Med J 2012;57:1–3. 10.1258/smj.2012.012023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lundberg A. Myalgia cruris epidemica. Acta Paediatr 1957;46:18–31. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1957.tb08627.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bove KE, Hilton PK, Partin J, et al. Morphology of acute myopathy associated with influenza B infection. Pediatr Pathol 1983;1:51–66. 10.3109/15513818309048284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Desdouits M, Munier S, Prevost MC, et al. Productive infection of human skeletal muscle cells by pandemic and seasonal influenza A(H1N1) viruses. PLoS One 2013;8:e79628 10.1371/journal.pone.0079628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]