Abstract

The kinetics and mechanism of the oxidation of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] (where dmgBF2 = difluoroboryldimethylglyoximato) by sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) were investigated by stopped-flow spectrophotometry at 450 nm over the temperature range of 10 °C ≤ θ ≤ 25 °C, pH range of 5.0 ≤ pH ≤ 7.8, and at an ionic strength of 0.60 M (NaCl). The pKa1 value for [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] was calculated as 5.27 ± 0.14 at I = 0.60 (NaCl). The redox process was dependent on pH and oxidant concentration in a complex manner, that is, kobs = ((k2[H+] + k1Ka)/([H+] + Ka))[OCl−]T, where at 25.3 °C, k1 was calculated as 3.54 × 104 M−1 s−1, and k2 as 2.51 × 104 M−1 cm−1. At a constant pH value, while varying the concentration of sodium hypochlorite two rate constants were calculated, viz., k′1 = 7.56 s−1 (which corresponded to a reaction pathway independent of the NaOCl concentration) and k′2 = 2.26 × 104 M−1 s−1, which was dependent on the concentration of NaOCl. From the variation in pH, , and were calculated as 58 ± 16 kJ mol−1, 46 ± 1 kJ mol−1, 34 ± 55 J mol−1 K−1, and −6 ± 4 Jmol−1 K−1, respectively. The self-exchange rate constant, k11, for sodium hypochlorite (as ClO−) was calculated to be 1.2 × 103 M−1 s−1, where an outer-sphere electron transfer mechanism was assumed. A green product, [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)]·1.75NaOCl, which can react with DMSO, was isolated from the reaction at pH 8.04 with a yield of 13%.

Keywords: Kinetics, Cobaloximes, Sodium hypochlorite, Self-exchange rate constants, 59Co NMR spectroscopy

1. Introduction

The conversion of solar energy to chemical energy is ever growing, so too with hydrogen being used as a clean renewable source of energy that is carbon-free [1–6]. Today, hydrogen production through the reduction of water appears to be a convenient solution for long term storage of renewable energy. However, due to the high cost of the catalyst produced from noble metals, there is a search and a need for viable hydrogen-producing catalysts based on cheaper and abundant first-row transition metals such as iron, cobalt, and nickel [7–9]. Cobaloximes [10] have been utilized to produce hydrogen in acidic media [11–13] as they essentially mimic the active centre of hydrogenases [14,15].

The most plausible route in the catalytic evolution of hydrogen involves the formation of a Co(I) species from either a Co(II) or Co (III) precursor [10,16]. Recent studies have been geared towards studying a Co(I)-containing intermediate through NMR spectroscopy [17], X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) [18], and high frequency electron paramagnetic resonance (HFEPR) [19] techniques. Other studies [13,16,20] have employed bridging binuclear systems to understand and enhance the catalyst performance for hydrogen production (See Fig. 1 for some examples). For photocatalytic processes employing binuclear complexes with a pyridine-type linker from the photoactive metal centre to a cobaloxime catalytic centre [21–23], the effect of a bridging ligand in the axial position on the electron transfer relative to the cobaloxime alone in a particular solvent has not been studied for the BF2 capped cobaloxime species. In photocatalytic experiments, acid sources such as p-cyanoanilinium, anilinium, and triethylammonium cations are usually employed in the process of producing hydrogen [24].

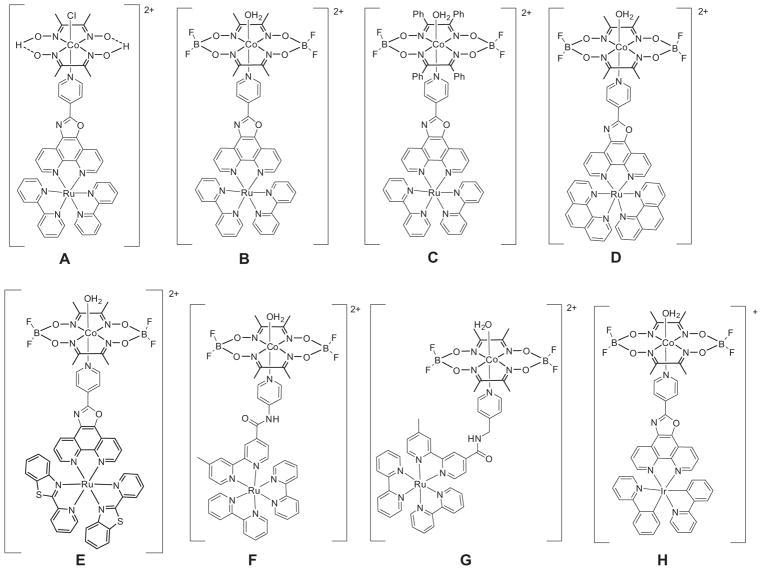

Fig. 1.

Binuclear mixed-metal complexes used for the production of hydrogen in acidic media [10,22,25].

For many years, we have been interested in the synthesis and characterization of transition metal complexes that contain at least one cobalt metal centre [22,26–33], and also inorganic reaction mechanisms that involve electron transfer processes [26,27,34–36]. Recently we reported the synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic studies of novel mixed-metal binuclear ruthenium(II)– cobalt(II) photocatalysts [Ru(pbt)2(L-pyr)Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)](PF6)2 (where pbt = 2-(2′-pyridyl)benzothiazole, L-pyr = (4-pyridine)- oxazolo[4,5-f]phenanthroline), [Ru(Me2bpy)2(L-pyr)Co(dmgBF2)2 -(OH2)](PF6)2 (where Me2bpy = 4,4′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine), and [Ru(phen)2(L-pyr)Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)](PF6)2 for hydrogen evolution in acidic acetonitrile [22]. More recently, Lawrence et al. [37] carried chemical and spectroelectrochemical reducing studies [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] in the presence of pyridine and its analogue in order to assess the stability of the resulting Co(I) species in various solvents.

As such, studies such as those reported by Lawrence et al. [37] have focused on the reduction the Co(II) metal centre to a Co(I) metal centre, but few researchers have reported the detailed chemistry of the oxidation of a Co(II) metal centre to a Co(III) metal centre in the cobaloxime, [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] in aqueous media. In some exciting and novel electron transfer studies carried by Bakac et al. [38], they observed the reversibility of the oxidation of [Co (dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] in the presence of , and the subsequent reduction of the oxidized species, [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2]+, by . In the presence of the , the absorbance at 450 nm was observed to decrease as the concentration of was increased. When was added it was observed that the 450 nm peak was regenerated, but it was observed that the absorbance was about 10% lower than the original absorbance for [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2]. In that same year, Connolly and Espenson [39], conducted experiments with BF2 capped cobaloximes in the presence of HCl and , and were successful in producing hydrogen until all of the was depleted. In that study, it was observed that the chromium(II) metal centre formed a bridged to the cobalt(II) metal centre of the cobaloxime via a chloro ligand before the electron transfer occurred to form an active cobalt(I) species.

In other electron transfer studies as carried out by Adin and Espenson [40] with the oxidants, [Co(NH3)5X]2+ (where X = F−, Cl−, or Br−), it was observed that with [Co(dmgH)2(OH2)2] (where dmgH = dimethylglyoximato), the electron transfer process occurred via an inner-sphere mechanism by the identification of the final products, which was found to be [Co(dmgH)2(OH2)X] (where X = F−, Cl−, or Br−) [40]. In a similar study with [Co (dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] and [Co(NH3)5X]2+ (where X = Br−, Cl−, or ), as reported by the very experienced team of Wang and Jordan [41], the observed rates were slower when compared to that of the hydrogen-bonded cobaloxime, [Co(dmgH)2(OH2)2] [41]. The rate constants with [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2], typically were ~103 times smaller and this was attributed largely to the smaller driving force for [Co(dmgH)2(OH2)2]. The observed difference in rate was attributed to the formation of a bridge between hydrogen-bonded species which would be harder to form in [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] [41]. In another study as reported by the revered research team of Wangila and Jordan [42], they used [Co(OH2)6](ClO4)3 to oxidize [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2], where they were able to determine the enthalpy and entropy of activation. At this time, we believe that there is still more to be learned about the electron transfer process involving [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2], which is a precursor to the oxidized species of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2]+ in aqueous media.

It is our goal to understand the electron transfer process between the cobaloxime, [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] and other oxidants that do not absorb in the same visible region (at λ = 450 nm) as the cobaloxime. As such, we decided to use the known oxidizing agent, sodium hypochlorite, which does not absorb in the region 300–1110 nm.

It must be also noted that reports of kinetics involving sodium hypochlorite and transition metal complexes in aqueous solution are very sparse, but in 2000, there was a report by Rajan et al. [43], where the hypochlorite oxidation of the Schiff base complex of chromium(IIl), trans-[Cr(salen)(OH2)2]+ was investigated at pH 9.0 in order to understand the mechanism of formation of an oxochromium( V) species, which has been implicated in the apoptotic cell death brought about by the trans-[Cr(salen)(OH2)2]+ cation. The reaction exhibited a two stage kinetic profile due to the formation of the oxochromium(V) species and its subsequent decay. The final product was unambiguously identified as chromate(VI). The overall stoichiometry of l[Cr(III)]:1.5[OCl−] was established for the reaction. The activation parameters for the formation of the oxochromium(V) species were ΔH‡ = 9.9 ± 1.8 kcal mol−1 and ΔS‡ = 24.5 ± 8.0 e.u [43]. Reaction schemes were proposed with Cr(V) and Cr(IV) binuclear species as possible intermediates. An inner-sphere mechanism was postulated for the formation of the oxochromium(V) intermediate [43].

We now describe some preliminary reactivity studies between [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] and some Co(III) oxidants and sodium hypochlorite; followed by a detailed study of the electron transfer process involving [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] and sodium hypochlorite at four different temperatures under pseudo-first order condition, with sodium hypochlorite in excess.

2. Material and methods

Analytical or reagent grade chemicals obtained from commercial sources were used as received throughout this study. Microanalyses (C, H, and N) were performed by Intertek Pharmaceutical Services (Whitehouse, NJ). All sodium hypochlorite solutions were made up using Alfa Aesar sodium hypochlorite (14.5% available chlorine), which was standardized against Na2S2O3·5H2O. The secondary standard, Na2S2O3·5H2O, was standardized against the primary standard, KIO3 using a standard literature procedure [44].

3. Experimental

3.1. Physical measurements

All 59Co NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker 400 MHz NMR spectrometer using the Bruker “cpmg1d” pulse sequence for up to 450,000 transients, and referenced to K3[Co(CN)6] in DMSO-d6 (δ = 289 ppm) [45]. All NMR spectra were processed using ACD/ NMR Processor Academic Edition Version 12.01.

All electrochemical data were acquired on a BASi® Epsilon C3 under an argon atmosphere in aqueous solution, which was thoroughly purged with Ar before any acquisition at room temperature. A standard three electrode configuration was employed consisting of a glassy carbon working electrode (diameter = 3 mm), Pt wire auxiliary electrode, and a Ag/AgCl (BASi, 3.0 M NaCl which was separated from the analytical solution by a Vicor® frit) reference electrode in aqueous media. The total ionic strength was maintained with 0.60 M NaCl.

3.2. UV–visible and kinetic studies

All UV–visible spectra were acquired on an Agilent® 8453A diode array spectrophotometer; while all kinetic measurements were acquired using a Hi-Tech SF-61SX2 stopped-flow spectrophotometer interfaced with a computer. The spectrophotometer syringes were immersed in a water-bath linked to a thermostat system (Haake AC 150/A10) capable of maintaining temperatures within ±0.01 °C. For the electron transfer reaction involving sodium hypochlorite and [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2], the following was carried out: A solution of the complex of known concentration was prepared in a volumetric flask (50 ml). The ionic strength of the solution was adjusted to the required value with appropriate amounts of NaCl; then the flask was thermostatted for 10 min before introducing the solutions into the syringes of the stopped-flow spectrophotometer. The apparatus was equilibrated to the reaction temperature for at least 1 h prior to use, and the complex solution with no buffer was kept in one of the thermostatted drive syringes for 5 min before each acquisition. By having no buffer in the complex’s solution, this was to ensure that the pH jump method was utilized as we found that both buffers can react slowly with the complex, but not on the stopped-flow time scale.

The other thermostatted syringe contained the sodium hypochlorite, phosphate buffer (NaH2PO4·H2O/Na2HPO4·2H2O), and the supporting electrolyte (NaCl). This syringe with its contents was also prethermostatted at the desired temperature. Both reactants were then mixed in the stopped-flow spectrophotometer after triggering. An excess of the oxidant was used in all cases to ensure pseudo-first order conditions. The kinetic data were collected and processed using TgK Scientific Kinetic Studio software suite V 4.0.1.27092. The pseudo-first order rate constants (kobs) were determined by a non-linear least squares regression to fit the curve of the photomultiplier voltage versus time. The reported rate constants are an average of at least three kinetic runs. The standard deviation for each kobs values is ±10%. The pH of each solution was measured with a Fisher Scientific Accument® XL150 pH/mV analyzer, fitted with a VWR sympHony probe.

3.3. Stoichiometric studies

The redox stoichiometry [oxidant:complex] was determined by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm ([Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2]) of buffered solutions containing the complex at a fixed concentration while varying the concentration of sodium hypochlorite; then determining the break point of the plot of absorbance versus the ratio, [NaOCl]:[complex].

3.4. Determination of the pKa1 value of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2]

The pKa1 value of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] was determined by measuring the largest absorbance change at 265 nm as the pH value was varied. Two buffers were employed for this study; for the pH values ranging from 3.50 to 5.50, a sodium acetate/acetic acid buffer was used; while the phosphate buffer was used in the pH range of 5.25–8.00.

3.5. Preparation of the complexes

[Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] [38], [Co(NH3)5Br]Br2 [46], [Co(NH3)5Cl] Cl2 [46], [Co(NH3)5OH2](ClO4)3 [28], and K[Co(EDTA)] ·2H2O [47] were prepared by the literature procedures.

3.6. Synthesis of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl

NaOCl (1.13 ml, 1.77 M stock concentration) was added to H2O (450 ml) in a 500 ml beaker; then the pH was adjusted to 8.04 with HCl. [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] (0.1008 g, 0.24 mmol) was added to the resulting solution, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 44 h during which time a green solid precipitated out of solution. The mixture was then filtered, and the residue was washed with deionized water, air dried, and collected. Yield = 0.0171 g (13%) Calc. for C8H15B2Cl1.75CoF4N4Na1.75O7.75: C, 17.41; H, 2.65; N, 10.15%. Found: C, 17.87; H, 2.31; N, 9.70%. FTIR (ν/cm−1): 826.9 (vs) (B–F), 941.9 (s) (B–F), 986.6 (vs) (O–B), 1101.0 (vs) (N–O), 1131.5 (s) (Co-OH), 1175.7 (vs) (B–F), 1215.5 (s) (N–O), 1635.2 (s) (C═N), and 3554.8 (vs) (O–H). δH (DMSOd6) = 1.90, 6.47, and 11.32 ppm; δCo (DMSO-d6) = 3077 ppm.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Reactions involving [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2]

4.1.1. Synthesis and characterization of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] · 1.75NaOCl

It is interesting to note that sodium hypochlorite can react with [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2]. When [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] was reacted with a sodium hypochlorite at a pH of 7.82 (phosphate buffer), the golden colour of the solution went colourless almost immediately, but when the solutions were unbuffered, and the ionic strength was not controlled it was observed that a green solid precipitated out of an aqueous solution. Due to this observation, we preformed the reaction on a larger scale and a green product isolated with a 13% yield (see Scheme 1). Elemental analysis (C, H, and N) was carried out on the green product, which was formulated as [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl. The complex was very insoluble in water and in acetonitrile, but had a solubility that was less than 1.0 mM in DMSO. On standing, we found that the green complex reacted with DMSO (see below for more details).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl.

An FTIR spectrum which was acquired for [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2) (OH)] ·1.75NaOCl revealed some interesting features as shown in Fig. 2. The FT IR spectrum of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl has ν(B–F) stretching frequencies at 826.9 cm−1 and 941.9 cm−1, as well as the ν(O–B) stretching frequency at 986.6 cm−1 [22]. The ν(B–F) stretching frequency which was originally observed at 1158.5 cm−1 in [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] was increased to 1175.7 cm−1 in the product. Similarly, the ν(C═N) stretching frequency for [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] which is observed at 1618.2 cm−1 also increased to 1638.4 cm−1. In [Co(dmgBF2)2 (OH2)2], the antisymmetric and symmetric ν(OH) stretching frequencies were observed at 3529.4 and 3601.6 cm−1, as well as the HOH bending at 1548.4 cm−1 [48]. When compared to the product the only stretching frequency from the water that was observed was the ν(OH) stretching frequency which was apparent at 3554.8 cm−1; while the peak corresponding to the bending stretching frequency for the cobalt-hydroxo bond, ν(Co-OH), was observed at 1131.5 cm−1 [48]. Any peak that would correspond to the OCl− species appears to be masked the stretching frequency of the complex [49]. The very weak O–Cl stretching frequency for OCl− should occur at 739 cm−1 [49], but this stretching frequency was found to be masked by the other stretching frequencies of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl.

Fig. 2.

Two FTIR spectra of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl.

Initially when [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl was added to DMSO only a small amount of the complex dissolved into the solution to produce a pale green colour, but as time progressed the solution’s colour changed to a dark brown as more and more of the complex dissolved into solution. Fig. 3 shows a plot of the molar extinction coefficient versus wavelength of [Co(dmgBF2)2 (OH2)2] and [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl (red) in DMSO, where for the latter, there is a peak at 451 nm with a molar extinction coefficient of 2.2 × 103 M−1 cm−1. The appearance of this peak signifies the possibility that DMSO is reacting with the complex to produce a species that is very soluble in DMSO.

Fig. 3.

A plot of the molar extinction coefficient versus wavelength of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] (black) and [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl (red) in DMSO. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The 1H NMR spectrum of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl in DMSO (Fig. 4) also reveals evidence that DMSO is reacting with [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl to form a Co(II) species. This is evident in the broad nature of the peaks in the 1H NMR spectrum as a resulting cobalt(II) species would be paramagnetic in nature. The methyl groups on the complex appears at δ = 1.90 ppm with the appearance of two other peak appearing at δ = 6.47 ppm and δ = 11.32 ppm which corresponds to the DMSO and hydroxo ligands, respectively. When compared to [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2], the methyl peak from [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl appears upfield in the 1H NMR spectrum. However, when compared to dimethylglyoxime (dmg), the chemical shifts for the methyl peaks are observed to similar chemical shift as well as the peak circa 11.32 ppm, which in the dimethylglyoxime case belongs to the oxime (C═N–OH).

Fig. 4.

1H NMR spectra of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl (A), [Co(dmgBF2)2 (OH2)2] (B), and dmg (C) in DMSO-d6.

On acquisition of the 59Co NMR spectrum of the product arising from the dissolved complex, [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl in DMSO-d6 (Fig. 5), a chemical shift was observed at δ = 3077 ppm. In comparison, Cropek et al. [22] observed a chemical shift of 5652 ppm in DMSO-d6 for [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2]. When we compare the chemical shifts of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] and the product that was formed from the reaction between [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl and DMSO-d6, the former appeared downfield to the latter. It must be stressed that detailed EPR spectroscopic studies will be carried out on the product that is formed in DMSO in order to ascertain the structural properties of the resulting product.

Fig. 5.

59Co NMR spectrum of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)] ·1.75NaOCl in DMSO-d6.

Dimethyl sulfoxide can act as an oxidant, whereby it is reduced to form dimethyl sulfide under mild conditions (aerobic and anaerobic) [50–52]. It has also been reported that DMSO can act as a reducing agent under certain conditions, yielding its fully oxidized form, dimethyl sulfone (DMSO2), as the product [53,54]. In our case, we believe that DMSO has reacted with [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2) (OH)] ·1.75NaOCl and reduced the Co(III) metal centre to a Co(II) metal centre. The Co(II)-containing product is believed to have DMSO coordinated as a ligand (see proposed structure 2).

4.1.2. A brief spectroscopic study between [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] and five Co(III) complexes as a reason why we chose sodium hypochlorite as an oxidant

Bakac et al. [38] have reported that the UV–visible spectrum of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] is characterized by absorption maxima at 456, 328, and 260 nm with molar extinction coefficients of 4.06 × 103, 1.92 × 103, and 5.82 × 103 M−1 cm−1, respectively. The peak at 456 nm is particularly characteristic and, owing to its position and intensity, is most often used in kinetics studies. In contrast, the cobalt(III) complex, [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2]+, as reported by Bakac et al. [38], has a relatively weak and featureless visible spectrum, with an intensity that rises into the UV region toward the general cobaloxime-type absorption at ca. 260 nm [38].

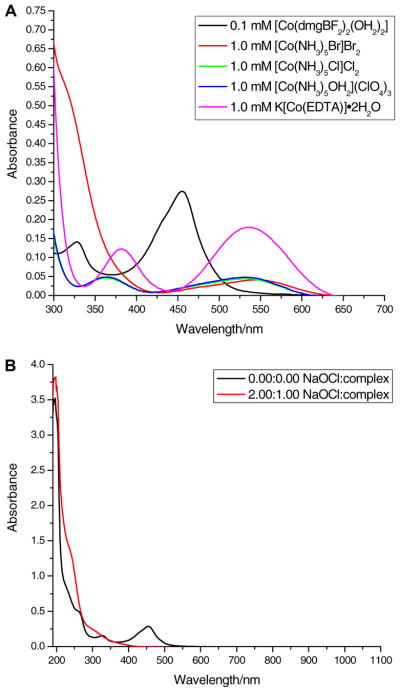

We carried out a UV–visible spectroscopic study between [Co (dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] and five Co(III) complexes in water. Fig. 6(A) shows the UV–visible spectra for all five Co(III) complexes, each at a concentration of 1.0 mM when compared to 0.10 mM for [Co (dmgBF2)2(OH2)2]. We expect that at 20 times (or higher) the concentration of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2], the peak at 450 nm would be completely masked by the absorbance of the Co(III) oxidants. When two equivalents of sodium hypochlorite are reacted with one equivalent of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2], there was a decrease in absorbance at 450 nm and an increase in absorbance at 250 nm (see Fig. 6(B)), which is indicative of the formation of [Co (dmgBF2)2(OH2)2]+. As there is no absorbance of sodium hypochlorite at 450 nm, we have elected to use an oxidizing agent that does not absorb at the λmax of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2]. This would enable us to determine the pseudo-first order rate constants when we carry out kinetics studies with [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] and sodium hypochlorite at 450 nm (where the largest absorbance change of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] is expected to occur).

Fig. 6.

A plot of absorbance versus wavelength comparing 0.1 mM [Co(dmgBF2)2(- OH2)2] in water to the respective 1.0 mM Co(III) complex (A), and a plot of absorbance versus wavelength for the reaction between 0.10 mM [Co(dmgBF2)2(- OH2)2] and 0.20 mM NaOCl (I = 0.60 M (NaCl), buffer = phosphate buffer, and pH = 7.33 ± 0.02) (B).

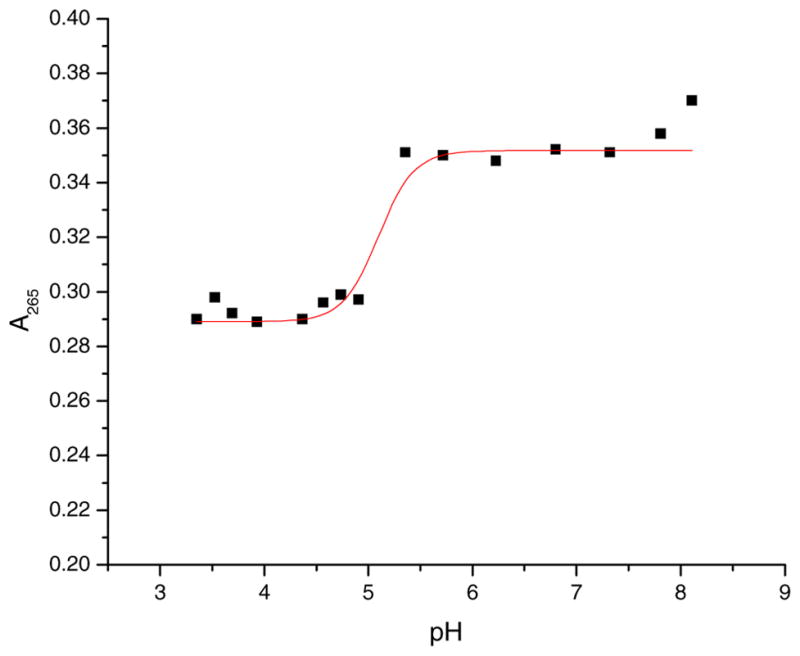

4.2. Determination of the pKa value for [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2]

The pKa1 value for the first dissociation of a proton from [Co (dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] was obtained via a variation in pH at a constant concentration of complex, where the larges absorbance change at 265 nm occurred (see Fig. 7). A non-linear regressional fit was used to determine a pKa1 value of 5.27 ± 0.14 (I = 0.60 M (NaCl)). The pKa1 value of 5.27 ± 0.14 for [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] can be compared to pKa1 = 4.40 ± 0.03 (I = 0.10 M (LiClO4)) for [Co(dmgBF2)2 (OH2)2]+ as reported by the revered research team of Wang and Jordan [41].

Fig. 7.

A plot of absorbance versus pH at room temperature. [Complex] = 0.10 mM, I = 0.60 M (NaCl), λ = 265 nm, acetate buffer (3.50 ≤ pH ≤ 5.50), and phosphate buffer (5.25 ≤ pH ≤ 8.00).

| (1) |

4.3. Nature of the reaction and the stoichiometry of the reaction

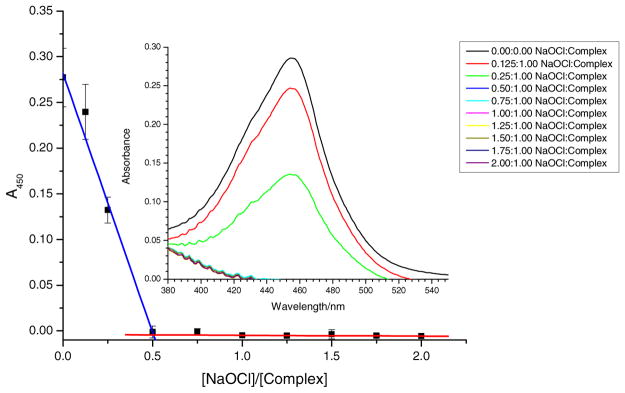

Sodium hypochlorite is known for its oxidizing ability; and in the literature, sodium hypochlorite and its protonated form hypochlorous acid are two electron acceptors [55]. Thus 1 mol of sodium hypochlorite should react with 2 mole of [Co(dmgBF2)2 (OH2)2] in aqueous solution. The stoichiometry was obtained via a spectrophotometric titration, where the disappearance of [Co (dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] was monitored at 450 nm (see Fig. 8 and Table 1). Due to the fact that hypochlorite is a two electron oxidant the stoichiometry that was observed was 0.5:1.0 ([NaOCl]: [complex]).

Fig. 8.

A plot of absorbance versus the ratio of [NaOCl]/[Complex] for the oxidation of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] by NaOCl. Inset = a plot of Absorbance versus wavelength for the oxidation of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] by NaOCl. [Complex] = 0.10 mM, λ = 450 nm, I = 0.60 M (NaCl), buffer = phosphate buffer, and pH = 7.33 ± 0.02.

Table 1.

Stoichiometry of the reaction between [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] and sodium hypochlorite, pH = 7.33 ± 0.02 (phosphate buffer), I = 0.60 M (NaCl), [complex] = 0.10 mM, λ = 450 nm, and cuvette path length = 1.00 cm.

| [NaOCl]T/[complex] | Absorbance |

|---|---|

| 0.000 | 0.28 |

| 0.125 | 0.24 |

| 0.250 | 0.13 |

| 0.500a | 0.00 |

| 0.750 | 0.00 |

| 1.000 | 0.00 |

| 1.250 | 0.00 |

| 1.500 | 0.00 |

| 1.750 | 0.00 |

| 2.000 | 0.00 |

Break point occurs at [NaOCl]T/[complex] = 0.50.

As such, the stoichiometric data in Table 1 and Fig. 8 are consistent with the reaction summarized in the following equation:

| (2) |

4.4. Sodium hypochlorite concentration, ionic strength, temperature, and pH dependence of the reaction

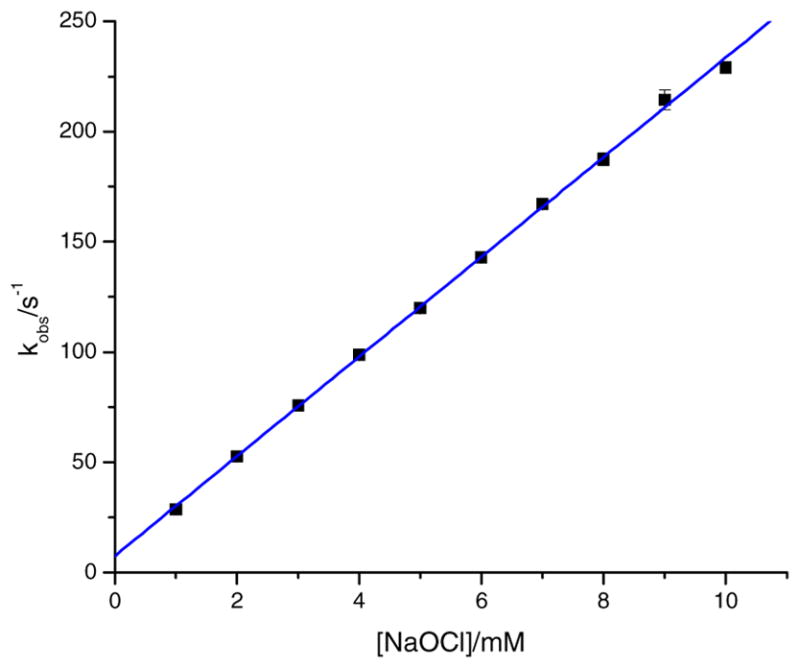

Kinetic studies were carried out over the ranges of 1.00 mM ≤ [NaOCl] ≤ 10.0 mM, 5.34 ≤ pH ≤ 7.78 and 10.3 °C ≤ θ ≤ 25.3 °C ranges, at a constant ionic strength of 0.60 M (NaCl). The reactions were observed at stopped-flow times in a uniphasic fashion where the pseudo-first order rate constants (kobs) were determined. For the kinetic runs where the total concentration of sodium hypochlorite was varied, it was observed that as the concentration increased, the kobs values also increased (see Table 2 and Fig. 9). The plot in Fig. 9 shows a positive slope as well as a non-zero intercept, where the intercept was given the term k′1 and the slope as k′2. A linear plot gave values for k′1 and k′2 as 7.56 s−1 and 2.26 × 104 M−1 s−1, respectively. The non-zero intercept can be interpreted as there is a step that is dependent on the solvent and not on the oxidant, or that there is some type of equilibrium that may exist. If the latter is the case, then the data can be interpreted as the reaction favoring the formation of the intermediate and subsequent oxidation. The following equation was used for the plot:

| (3) |

Table 2.

Pseudo-first order rate constants for the oxidation of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] by NaOCl. Variation in NaOCl concentration. [Complex] = 0.10 mM, λ = 450 nm, I = 0.60 M (NaCl), θ = 10.1 °C, buffer = phosphate buffer, and pH = 7.45 ± 0.08.

| [NaOCl]/mM | 10−2 kobs/s−1 |

|---|---|

| 1.00 | 0.27 |

| 2.00 | 0.53 |

| 3.00 | 0.76 |

| 4.00 | 0.99 |

| 5.00 | 1.20 |

| 6.00 | 1.43 |

| 7.00 | 1.67 |

| 8.00 | 1.88 |

| 9.00 | 2.14 |

| 10.0 | 2.29 |

Fig. 9.

A plot of kobs versus the concentration of NaOCl. [Complex] = 0.10 mM, λ = 450 nm, I = 0.60 M (NaCl), θ = 10.1 °C, buffer = phosphate buffer, and pH = 7.82 ± 0.08.

The ionic strength has been recognized for its effects on the rates of ionic reactions [35,56]. When the reacting species have similar charges, the rate of reaction is observed to increase, whereas when the reacting species have opposite charges, the rate of reaction is observed to decrease [35,56]. Upon varying the ionic strength as shown by in our kinetic data in Table 3, as the ionic strength is increased, the kobs value is increased. By applying the Brönsted-Bjerrum equation [57],

Table 3.

Pseudo-first order rate constants for the oxidation of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] by NaOCl at various ionic strengths. [Complex] = 0.05 mM, [NaOCl] = 3.00 mM, λ = 450 nm, θ = 10.1 °C, buffer = phosphate buffer, and pH = 5.49 ± 0.11.

| I/M | kobs/s−1 |

|---|---|

| 0.24 | 36.06 ± 0.01 |

| 0.30 | 38.45 ± 1.16 |

| 0.40 | 42.30 ± 3.15 |

| 0.50 | 43.48 ± 4.48 |

| 0.60 | 47.15 ± 4.41 |

| (4) |

where is the rate constant at infinite dilution, z1 and z2 are the ionic charges of the reactants, and A is the Debye-Hückel constant (A = 0.4961 M−1/2 at 10 °C) [57]. By carrying out a linear regressional analysis on Eq. (4) with the data from Table 3, z1z2 was calculated as +1.04 and as 1.65 × 101 s−1. From the value of z1z2, it can be inferred that the reacting species have charges of z1 = −1 and z2 = −1, which signifies that the reacting species in solution are [Co (dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)]− and OCl− at pH 5.49.

Under the pseudo-first order conditions, it was observed that the kobs values decreased slightly; then increased as the pH was increased (see Table 4). Based on the data in Table 4, this reaction is pH dependent. Over the pH range used in the study, the predominant species in solution is HOCl which begins to decrease as the pH is increased to form OCl− [58]. The pKa value of HOCl was reported as 7.4 [58,59]. At pH 7.4, we would expect 50% HOCl and 50% OCl− to be in existence. From the pKa value of 5.27 for [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2], it can be deduced that the predominant species would be the aqua hydroxo species, [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)]− over the pH range (5.34–7.42) used in this study as shown in Table 4 and Fig. 10.

Table 4.

Pseudo-first order rate constants for the oxidation of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] by NaOCl by varying the pH. [Complex] = 0.05 mM, [NaOCl] = 3.00 mM, λ = 450 nm, I = 0.60 M (NaCl), and buffer = phosphate buffer.

| θ = 10.3 °C | θ = 15.2 °C | θ = 20.0 °C | θ = 25.3 °C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| pH | kobs/s−1 | pH | kobs/s−1 | pH | kobs/s−1 | pH | kobs/s−1 |

| 5.50 | 27.0 | 5.42 | 35.8 | 5.35 | 44.3 | 5.34 | 76.3 |

| 5.77 | 27.6 | 5.63 | 35.3 | 5.63 | 41.2 | 5.64 | 74.0 |

| 6.12 | 26.3 | 6.02 | 34.5 | 6.01 | 39.1 | 5.98 | 72.2 |

| 6.50 | 24.5 | 6.43 | 31.5 | 6.44 | 38.0 | 6.44 | 76.2 |

| 6.96 | 28.9 | 6.85 | 36.7 | 6.85 | 46.4 | 6.88 | 92.3 |

| 7.42 | 33.6 | 7.23 | 44.0 | 7.26 | 54.2 | 7.27 | 113.8 |

| 7.62 | 36.5 | 7.53 | 48.2 | 7.78 | 59.3 | 7.51 | 128.7 |

Fig. 10.

A plot of kobs versus pH. [Complex] = 0.05 mM, [NaOCl] = 3.00 mM, λ = 450 nm, I = 0.60 M (NaCl), θ = 25.3 °C, and buffer = phosphate buffer.

The data in Tables 2–4 can be satisfactorily explained in terms of the proposed mechanism shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Mechanism for the oxidation of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] by sodium hypochlorite.

The expression for such a mechanism would then lead to Eq. (5):

| (5) |

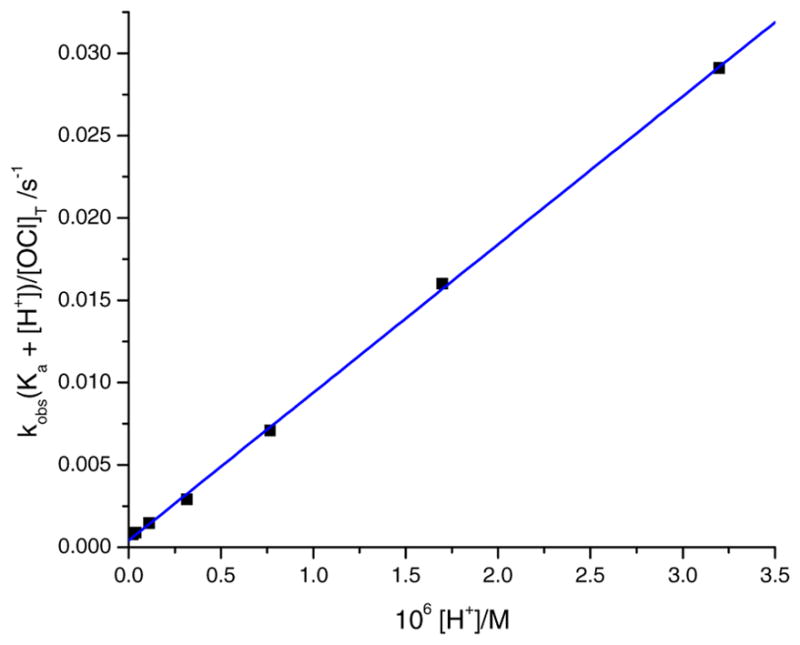

where [OCl−]T is the total hypochlorite concentration. Since the concentration of OCl− is increasing as the pH is increased and the fact that there is an increase in the kobs value, k1 should be the main contributing path over the pH range, and Eq. (5) can be rearranged to give:

| (6) |

A plot of the left-hand side of the Eq. (6) versus [H+] is linear over the range 5.34 ≤ pH ≤ 7.42, with the slope being k2 and an intercept being k1Ka. A plot at 10.3 °C is shown in Fig. 11. A linear regressional analysis was performed and the second-order rate constants k1 and k2 were calculated for each temperature. The k1 and k2 values are shown in Table 5, along with the corresponding enthalpy and entropy of activation calculated using the Eyring’s equation. The negative entropy of activation in Table 5 is indicative of an associative mechanism, or could implicate the solvent as playing a dominant role.

Fig. 11.

A plot of kobs(Ka + [H+])/[OCl]T versus [H+] for the oxidation of [Co (dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] by 3 mM NaOCl. [Complex] = 0.05 mM, λ = 450 nm, I = 0.60 M (NaCl), θ = 10.3 °C, and buffer = phosphate buffer.

Table 5.

Rate parameters values and the activation parameters for the reaction between [Co (dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] and sodium hypochlorite.

| θ/ °C | 10−4 k1/M−1s−1 | 10−4 k2/M−1s−1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.3 | 0.99 | 0.90 | ||

| 15.2 | 1.05 | 1.25 | ||

| 20.0 | 1.63 | 1.80 | ||

| 25.3 | 3.54 | 2.51 | ||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Table 6 shows a few oxidants that have been studied in conjunction with [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] for developing mechanisms for the electron transfer process, where the mechanism for many of these reactions are known as reported in the literature data of the said table.

Table 6.

Table of rate constants and activation parameters for the oxidation of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] by various oxidants.

| Oxidant | I/M | θ/°C | k/M−1s−1 | ΔH‡/kJ mol−1 | ΔS‡/J mol−1 K−1 | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaOCl | 0.6a | 25.3 | 3.54 × 104 | 58 ± 16 | 34 ± 55 | This work |

| HOCl | 0.6a | 25.3 | 2.51 × 104 | 46 ± 1 | −6 ± 4 | This work |

| [Co(NH3)5Br]2+ | 0.1b | 25 | 50 | – | – | [41] |

| [Co(NH3)5Cl]2+ | 0.1b | 25 | 2.90 | – | – | [41] |

| [Co(NH3)5N3]2+ | 0.1b | 25 | 5.90 | – | – | [41] |

| [Fe(bpy)3]3+ | 0.04c | 25 | 1.59 × 106 | 9.3 | −95.0 | [60] |

| [Co(OH2)5(OH)]2+ | 1.0b | 25 | 1.00 × 105 | 75.8 | 66.1 | [42] |

| [Fe(OH2)6]3+ | 0.5b | 25 | 2.90 × 102 | – | – | [42] |

| [Fe(OH2)5(OH)]2+ | 0.5b | 25 | 6.20 × 104 | – | – | [42] |

NaCl.

LiClO4.

HNO3/NaNO3.

If we take the [Co(NH3)5X]2+ (where X = Cl−, Br−, or ) series, all the oxidants used in Table 6 were observed to react via an inner-sphere mechanism. In the studies conducted on [Co(OH2)5 (OH)]2+, [Fe(OH2)6]3+, and [Fe(OH2)5(OH)]2+ it was reported that the electron transfer occurred through an inner-sphere mechanism, which occurs via a hydroxide-bridged intermediate [38,42]. In the case of [Fe(bpy)3]3+, since the bpy ligands cannot form a bridge to the cobaloxime, it was deemed that this reaction proceeded via an outer-sphere mechanism [60]. When we compare the oxidants, [Fe(bpy)3]3+ and NaOCl, there is a definite trend in ΔS‡, with the value being less negative as the charge of the oxidant decreases from +3 to −1, indicating that the higher charged transition state gives more loss of entropy. This may be expected if solvent molecules become more restricted around a more highly charged activated complex.

4.5. Electrochemical studies and the Marcus cross relationship

The Marcus cross relationship is often used in determining whether or not a reaction proceeds via an outer-sphere electron transfer [61–63]. The Marcus theory predicts the second-order rate constant (k12) for heteronuclear outer-sphere redox reactions from the electron self-exchange rate constants (k11 and k22) of the respective oxidant and reductant. In order to apply the Marcus theory, the redox potentials for both reactants are needed to calculate the overall equilibrium constant (K12). Before applying the Marcus equation, it is important to acquire the cyclic voltammogram for [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] in order to determine the CoII/III redox couple. As such, the cyclic voltammogram of [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] was acquired in water with NaCl as the supporting electrolyte (see Fig. 12). In order to convert all redox couples to be versus NHE, the conversion factor of +0.206 V was added to the CoII/III and CoII/I redox couples (versus Ag/AgCl) as shown in Fig. 12. Thus, the couples of E1/2 (CoII/III) = +0.36 V and E1/2 (CoII/I) = −0.61 V (both versus Ag/AgCl) were converted to give redox couples of E1/2 (CoII/III) = +0.57 V and E1/2 (CoII/I) = −0.40 V (both versus NHE), respectively.

Fig. 12.

A cyclic voltammogram of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] in water. Working electrode = glassy carbon electrode, auxiliary electrode = Pt wire, reference electrode = Ag/AgCl, supporting electrolyte = 0.6 M (NaCl), [complex] = 1.0 mM, and scan rate = 100 mV s−1.

In the cyclic voltammogram (Fig. 12), the CoII/III redox couple calculated as +0.57 V (versus NHE) at I = 0.60 M (NaCl) in aqueous media is more cathodic in value than the values obtained by Lawrence et al. (E1/2 (CoII/III) = +0.69 V (versus NHE) at I = 0.10 M (NaClO4)) [37], Bakac et al., (E1/2 (CoII/III) = +0.68 V (versus NHE) at I = 0.10 M (LiClO4)) [38], and Wang and Jordan (E1/2 (CoII/III) = +0.65 V (versus NHE) at I = 0.10 M) [41].

When we compare the CoII/III redox couple in acetonitrile [37,64,65], it is generally observed to be quasi-reversible at E1/2 (CoII/III) = +0.70 V (versus a Ag wire) at I = 0.10 M ([nBu4N]ClO4) [37], where the redox couple tends to appear more anodic when compared to our value of E1/2 (CoII/III) = +0.36 V (versus Ag/AgCl) at I = 0.6 M (NaCl).

If we were to assume that the electron transfer process between [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] and NaOCl is outer-sphere, then we have to apply the Marcus theory. The equations used in the Marcus theory are as follows [61–63]:

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

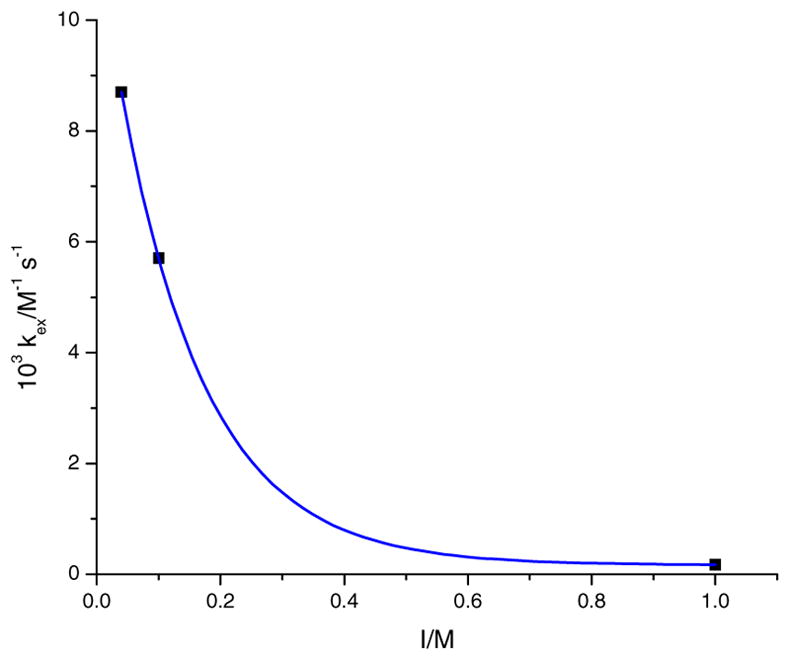

where k11 and k22 are the self-exchange rate constants for OCl− and [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2], respectively. In calculating the self-exchange rate constant, k22, for the complex (at I = 0.60 M (NaCl)), the points that were used are as follows: 8.7 × 10−3 [60], 5.7 × 10−3 [41], and 1.7 × 10−4 M−1 s−1 [42], for the ionic strengths of 0.04 M (NaNO3), 0.1 M (LiClO4), and 1.0 M (LiClO4), respectively. It is assumed that the k22 value is independent on the type of supporting electrolyte, but it is noted that k22 is dependent upon the variation of ionic strength. The self-exchange rate constant for [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2], k22 = 3.1 × 10−4 M−1 s−1, was calculated from Fig. 13 at an ionic strength of 0.60 M. From the Marcus cross equation, [66], , K12 = 6.59 × 1010, and k12 = 3.5 × 104 M−1 s−1 (from the OCl− pathway in Scheme 2). Since the self-exchange rate constant for OCl− has not been reported in the literature, and the reaction is assumed to be an outer-sphere electron transfer process; then the self-exchange rate constant (k11) for OCl− was calculated as 1.2 × 103 M−1 s−1 at 25.3 °C.

Fig. 13.

A plot of kex versus ionic strength for [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] in water.

Table 7 shows the self-exchange rate constants calculated by the Marcus relationship for electron transfer processes that involve [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] and several oxidants. If we compare the k22 values of the reactions that are known to proceed via an outer-sphere mechanism, we observe those values to be relatively small. When we compare those values to the values from the studies involving the hexaaquairon(III) cation, the k22 values are much larger and could be attributed to the inner-sphere electron transfer. We found that the k12 value for the [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2]/OCl− couple is smaller than the [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2]/[Fe(bpy)3]3+ couple, but the k11 value is nearly 10 times larger for the former. The reason why the k12 value is lower for the [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2]/ OCl− couple when compared to that of the [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2]/ [Fe(bpy)3]3+ couple is because there is some repulsion between the predominant species of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)]− and OCl− during the outer-sphere electron transfer process under the weakly acidic and basic conditions

Table 7.

Self-exchange rate constants as calculated by the Marcus relationship [42].

| Couple | logK12 | k12/M−1s−1 | k22/M−1s−1 | f12 | k11/M−1s−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] + [Co(OH2)5(OH)]2+a | 13.53 | 1.0 × 105 | 1.7 × 10−4 | 1.2 × 10−2 | 1.6 × 102 |

| [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] + [Fe(bpy)3]3+b | 7.27 | 1.6 × 106 | 8.7 × 10−3 | 1.7 × 10−1 | 8.0 × 106 |

| [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2]+ + [Co(sep)3]2+c | 10.49 | 5.5 × 103 | (2.0 × 10−3)d | 5.8 × 10−2 | 3.5 |

| [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2]+ + [Co(sep)3]2+c | 15.05 | 1.5 × 105 | (6.6 × 10−4)d | 3.5 × 10−3 | 3.5 |

| [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] + [Fe(OH2)6]3+e | 1.69 | 2.9 × 102 | 1.3 × 102 | 9.3 × 10−1 | 4.2f |

| [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] + [Fe(OH2)6]3+e | 1.69 | 2.9 × 102 | 9.4 × 104 | 9.3 × 10−1 | (6.2 × 10−3)g |

| [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] + [Fe(OH2)5(OH)]2+e | −4.75 | 6.2 × 104 | 4.1 × 1011 | 1.3 × 10−1 | 3.0 × 103 |

| [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2] + OCl−h | 10.82 | 3.5 × 104 | 3.1 × 10−4 | 5.0 × 10−2 | 1.2 × 103 |

At 25 °C with I = 1.0 M (LiClO4) [42].

Reference [60].

Reference [41].

The k22 for [Co(dmgBF2)2(H2O)2]+/0 and [Co(dmgH)2(H2O)2]+/0 recalculated from [41].

At 25 °C with I = 0.5 M (LiClO4).

Reference [67].

Determined from a least-squares fit to with Z = 1.9 × 1010 M−1 cm−1 [68].

Our work: I = 0.60 M (NaCl) at 25.3 °C.

5. Conclusions

In this work we have successfully studied the oxidation of [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)2] by NaOCl in an aqueous medium. A minor product from the reaction of the aforementioned reactants was analyzed via UV–visible, FT IR, and by 1H and 59Co NMR spectroscopies, as well as by C, H, and N elemental analysis. In the kinetics studies conducted, the OCl− species was observed to be the major reactive species on reacting with [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)(OH)]−. This was evident in both the salt effect study as well as when the pH of the reaction was varied. The application of the Marcus cross relationship in our current study could imply that the electron transfer process that occurs between the cobaloxime and the hypochlorite anion is outer-sphere mechanism in nature. As such, our k11, the self-exchange rate constant for OCl− was calculated as 1.2 × 103 M−1 s−1. Comprehensive studies with this important cobaloxime, [Co(dmgBF2)2(OH2)] and other colourless oxidants are needed to provide further mechanistic insight into the electron transfer process in order to learn more about the most plausible route in the catalytic evolution of hydrogen that involves the formation of a Co(I) species from either a Co(II) or Co(III) precursor [10,16].

Acknowledgments

AAH would like to thank the National Science Foundation (NSF) for a National Science Foundation CAREER Award as this material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under CHE-1431172 (formerly CHE –1151832). AAH would also like to thank Old Dominion University’s Faculty Proposal Preparation Program (FP3), and also for the Old Dominion University startup package that allowed for the successful completion of this work. LSJ would like to thank The University of the Virgin Islands Emerging Caribbean Scientists Program and the Minority Biomedical Research Support Research Initiative for Scientific Enhancement (MBRS-RISE), grant # 5R25GM061325.

References

- 1.Armaroli N, Balzani V. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:52–66. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg R, Nocera DG. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:6799–6801. doi: 10.1021/ic058006i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffert MI, Caldeira K, Jain AK, Haites EF, Harvey LDD, Potter SD, Schlesinger ME, Schneider SH, Watts RG, Wigley TML, Wuebbles DJ. Nature. 1998;395:881–884. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray HB. Nat Chem. 2009;1:7–7. doi: 10.1038/nchem.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lubitz W, Tumas W. Chem Rev. 2007;107:3900–3903. doi: 10.1021/cr050200z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Service RF. Science. 2005;309:548–551. doi: 10.1126/science.309.5734.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon RB, Bertram M, Graedel TE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1209–1214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509498103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du P, Knowles K, Eisenberg R. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12576–12577. doi: 10.1021/ja804650g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esswein AJ, Nocera DG. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4022–4047. doi: 10.1021/cr050193e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dempsey JL, Brunschwig BS, Winkler JR, Gray HB. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:1995–2004. doi: 10.1021/ar900253e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dempsey JL, Winkler JR, Gray HB. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1060–1065. doi: 10.1021/ja9080259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han A, Wu H, Sun Z, Jia H, Yan Z, Ma H, Liu X, Du P. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:10929–10934. doi: 10.1021/am500830z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valdez CN, Dempsey JL, Brunschwig BS, Winkler JR, Gray HB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:15589–15593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118329109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bacchi M, Berggren G, Niklas J, Veinberg E, Mara MW, Shelby ML, Poluektov OG, Chen LX, Tiede DM, Cavazza C, Field MJ, Fontecave M, Artero V. Inorg Chem. 2014;53:8071–8082. doi: 10.1021/ic501014c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Razavet M, Artero V, Fontecave M. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:4786–4795. doi: 10.1021/ic050167z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNamara WR, Han Z, Yin CJ, Brennessel WW, Hollan PL, Eisenberg R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:15594–15599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120757109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marinescu SC, Winkler JR, Gray HB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:15127–15131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213442109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smolentsev G, Guda AA, Janousch M, Frieh C, Jud G, Zamponi F, Chavarot-Kerlidou M, Artero V, van Bokhoven JA, Nachtegaal M. Faraday Discuss. 2014;171:259–273. doi: 10.1039/c4fd00035h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krzystek J, Ozarowski A, Zvyagin SA, Telser J. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:4954–4964. doi: 10.1021/ic202185x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laga SM, Blakemore JD, Henling LM, Brunschwig BS, Gray HB. Inorg Chem. 2014;53:12668–12670. doi: 10.1021/ic501804h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manton JC, Long C, Vos JG, Pryce MT. Dalton Trans. 2014;43:3576–3583. doi: 10.1039/c3dt53166j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cropek DM, Metz A, Muller AM, Gray HB, Horne T, Horton DC, Poluektov O, Tiede DM, Weber RT, Jarrett WL, Phillips JD, Holder AA. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:13060–13073. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30309d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fihri A, Artero V, Pereira A, Fontecave M. Dalton Trans. 2008:5567–5569. doi: 10.1039/b812605b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacques PA, Artero V, Pecaut J, Fontecave M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20627–20632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907775106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C, Wang M, Pan J, Zhang P, Zhang R, Sun L. J Organomet Chem. 2009;694:2814–2819. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holder AA, Dasgupta TP. Inorg Chim Acta. 2002;331:279–289. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holder AA, Dasgupta TP, Im SC. Transition Met Chem. 1997;22:135–140. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holder AA, Dasgupta TP. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1996:2637–2643. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holder AA, Dasgupta TP, McFarlane W, Rees NH, Enemark JH, Pacheco A, Christensen K. Inorg Chim Acta. 1997;260:225–228. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moody LM, Balof S, Smith S, Rambaran VH, VanDerveer D, Holder AA. Acta Crystallogr, Sect E: Struct Rep Online. 2008;E64:m262–m263. doi: 10.1107/S1600536807067141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rambaran VH, Erves TR, Grover K, Balof S, Moody LV, Ramsdale SE, Seymour LA, VanDerveer D, Cropek DM, Weber RT, Holder AA. J Chem Crystallogr. 2013;43:509–516. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan H, Newton DAL, Seymour LA, Metz A, Cropek D, Holder AA, Ofoli RY. Catal Commun. 2014;56:76–80. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawrence MAW, McMillen CD, Gurung RK, Celestine MJ, Arca JF, Holder AA. J Chem Crystallogr. 2015;45:427–433. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varey JE, Lamprecht GJ, Fedin VP, Holder A, Clegg W, Elsegood MRJ, Sykes AG. Inorg Chem. 1996;35:5525–5530. doi: 10.1021/ic951659m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holder AA, Brown RF, Marshall SC, Payne VC, Cozier MD, Alleyne WA, Bovell CO. Transition Met Chem. 2000;25:605–611. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawrence MAW, Holder AA. Inorg Chim Acta. 2016;441:157–168. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawrence MA, Celestine MJ, Artis ET, Joseph LS, Esquivel DL, Ledbetter AJ, Cropek DM, Jarrett WL, Bayse CA, Brewer MI, Holder AA. Dalton Trans. 2016;45:10326–10342. doi: 10.1039/c6dt01583b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakac A, Brynildson ME, Espenson JH. Inorg Chem. 1986;25:4108–4114. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Connolly P, Espenson JH. Inorg Chem. 1986;25:2684–2688. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adin A, Espenson JH. Inorg Chem. 1972;11:686–688. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang K, Jordan RB. Can J Chem. 1996;74:658–665. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wangila GW, Jordan RB. Inorg Chim Acta. 2005;358:3753–3760. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajan R, Nair BU, Ramasami T. Bioinorg React Mech. 2000;1:247–256. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jeffery G, Bassett J, Mendham J, Denney R. Vogel’s Textbook of Quantitative Chemical Analysis. John Wiley and Sons Inc; New York NY: 1989. p. 10158. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taura T. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1990;63:1105–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Halmos Z, Wendlandt WW. Thermochim Acta. 1972;5:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dwyer FP, Gyarfas EC, Mellor DP. J Phys Chem. 1955;59:296–297. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakamoto K. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds. Wiley Online Library; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hedberg K, Badger RM. J Chem Phys. 1951;19:508–509. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen TK, Thornton D, Ho MY. Int J Pharm. 1990;59:211–216. [Google Scholar]

- 51.López NI, Duarte CM. J Sea Res. 2004;51:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kharasch N, Thyagarajan B. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1983;411:391–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1983.tb47334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beilke MA, Collins-Lech C, Sohnle PG. J Lab Clin Med. 1987;110:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharon D, Afri M, Noked M, Garsuch A, Frimer AA, Aurbach D. J Phys Chem Lett. 2013;4:3115–3119. doi: 10.1021/jz3017842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rayner-Canham G, Overton T. Descriptive Inorganic Chemistry. Macmillan; 2003. The group 17 elements: the halogens; pp. 4421–4472. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bronsted JN. Z Physik Chem. 1922;102:169–207. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manov GG, Bates RG, Hamer WJ, Acree SF. J Am Chem Soc. 1943;65:1765–1767. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soulard M, Bloc F, Hatterer A. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1981:2300–2310. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gazda M, Margerum DW. Inorg Chem. 1994;33:118–123. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wangila GW, Jordan RB. Inorg Chim Acta. 2005;358:2804–2812. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marcus R. Discuss Faraday Soc. 1960;29:21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marcus RA. Can J Chem. 1959;37:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marcus R. J Phys Chem. 1963;67:853–857. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hu XL, Brunschwig BS, Peters JC. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:8988–8998. doi: 10.1021/ja067876b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baffert C, Artero V, Fontecave M. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:1817–1824. doi: 10.1021/ic061625m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harrison R. Nuffield Advanced Science Book of Data. Longman; London: 1972. Standard electrode potentials; pp. 116–118. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Silverman J, Dodson RW. J Phys Chem. 1952;56:846–852. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hupp JT, Weaver MJ. Inorg Chem. 1983;22:2557–2564. [Google Scholar]