Abstract

Background

Childhood-onset bipolar disorder (BD) is a serious condition that affects the patient and family. While research has documented familial dysfunction in individuals with BD, no studies have compared developmental differences in family functioning in youths with BD vs. adults with prospectively verified childhood-onset BD.

Methods

The Family Assessment Device (FAD) was used to examine family functioning in participants with childhood-onset BD (n=116) vs. healthy controls (HCs) (n=108), ages 7–30 years, using multivariate analysis of covariance and multiple linear regression.

Results

Participants with BD had significantly worse family functioning in all domains (problem solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, behavior control, general functioning) compared to HCs, regardless of age, IQ, and socioeconomic status. Post-hoc analyses suggested no influence for mood state, global functioning, comorbidity, and most medications, despite youths with BD presenting with greater severity in these areas than adults. Post-hoc tests eliminating participants taking lithium (n=17) showed a significant diagnosis-by-age interaction: youths with BD had worse family problem solving and communication relative to HCs.

Limitations

Limitations include the cross-sectional design, clinical differences in youths vs. adults with BD, ambiguity in FAD instructions, participant-only report of family functioning, and lack of data on psychosocial treatments.

Conclusions

Familial dysfunction is common in childhood-onset BD and endures into adulthood. Early identification and treatment of both individual and family impairments is crucial. Further investigation into multi-level, family-based mechanisms underlying childhood-onset BD may clarify the role family factors play in the disorder, and offer avenues for the development of novel, family-focused therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, child, adolescent, young adult, family functioning, Family Assessment Device

Introduction

Childhood-onset bipolar disorder (BD) is a complex condition affecting 1–2% of youths (Van Meter et al., 2011). Compared to individuals with late adolescent- and adult-onset BD, youths with childhood-onset BD spend more time symptomatic with mixed depressive and manic presentations, rapid mood fluctuations, and subthreshold symptoms (Birmaher et al., 2009; Birmaher et al., 2014; Geller et al., 2008). These youths also have greater functional impairment (Perlis et al., 2009), poorer quality of life (Perlis et al., 2009), and higher risk for suicidality (Perlis et al., 2004). In addition, childhood-onset BD often persists into adulthood, leading to further impairment and negative outcomes (Axelson et al., 2011; Birmaher et al., 2009; Birmaher et al., 2014; Geller et al., 2008; Leverich et al., 2007). Given the enduring nature of this disorder, there is a critical need for studies to directly evaluate developmental effects by aggregating data from children, adolescents, and adults in order to examine the phenomenology and mechanisms of BD across the lifespan, and thereby enhance diagnosis and treatment efforts.

Family functioning is one such process relevant to BD and important to understand from a developmental perspective, as findings could indicate optimal family involvement in treatment and age-specific intervention targets. In addition to the patient, families of individuals with childhood-onset BD are quite impaired. Compared to healthy controls (HCs) and youths with other psychiatric conditions, families of youths with BD display high levels of conflict, control, aggression, quarreling, forceful punishment, tension, stress, and negative expressed emotion; and low levels of warmth, affection, intimacy, cohesion, expressiveness, organization, and positive expressed emotion (Belardinelli et al., 2008; Keenan-Miller et al., 2012; Nader et al., 2013; Perez Algorta et al., 2017; Schenkel et al., 2008). Family dysfunction also predicts worse course of BD in youths, including: 1) low maternal warmth (Geller et al., 2008); 2) chronic stress in family, romantic, and peer relationships (Kim et al., 2007; Siegel et al., 2015); 3) frequency and severity of stressful life events (Kim et al., 2007); 4) low levels of cohesion and adaptability (Sullivan et al., 2012); and 5) high levels of conflict (Sullivan et al., 2012). This relationship is also bidirectional, with patients’ symptoms/behaviors reciprocally influencing caregivers’ burden/distress (Reinares et al., 2016b). Thus, psychosocial evidence-based treatments (EBTs) for childhood-onset BD incorporate family-based strategies including psychoeducation, communication, problem solving, and affect regulation to address these impairments (Fristad and MacPherson, 2014).

Familial caregivers (e.g., parents, spouses, close relatives) of adults with BD display comparable dysfunction, including low levels of cohesion, expressiveness, and organization; and high levels of conflict (Miklowitz, 2011; Miklowitz and Johnson, 2009; Reinares et al., 2016a; Solomon et al., 2008; Weinstock et al., 2006). In addition, high expressed emotion (Kim and Miklowitz, 2004; Yan et al., 2004) and familial negative affective style (O’Connell et al., 1991) predict recurrence in adults with BD. However, no research has examined the persistence of family dysfunction into adulthood among individuals with childhood-onset BD. One study demonstrated that adults with retrospectively obtained childhood-onset BD experienced sustained psychosocial/functional impairment during prospective observation on a measure that assessed work, relationships (including family), recreation, and life satisfaction (Perlis et al., 2009). Though, family functioning in particular was not assessed in this study, and determination of childhood-onset BD diagnoses may have been influenced by retrospective recall bias (Leboyer et al., 2005). Importantly, no studies have directly compared family functioning in youths with BD vs. adults with prospectively verified childhood-onset BD (youth participants with BD followed into adulthood).

Unfortunately, research is often artificially bifurcated by regulatory requirements or investigator expertise/training in pediatrics or adults, and few datasets have prospectively established childhood-onset BD (Birmaher et al., 2009; Geller et al., 2008). These limitations make it challenging to evaluate developmental differences in mechanisms and processes implicated in childhood-onset BD. In addition, no studies have specifically examined the developmental progression of familial dysfunction in this condition, despite its relevance to onset and course of the disorder (Geller et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2007; Reinares et al., 2016b; Siegel et al., 2015). Importantly, parent and family variables also influence psychosocial treatment outcomes in childhood-onset BD, serving as both moderators (Miklowitz et al., 2009; Sullivan et al., 2012; Weinstein et al., 2015) and mediators (MacPherson et al., 2016; Mendenhall et al., 2009). Thus, enhanced understanding of family processes in childhood-onset BD is crucial from both a phenomenological and intervention perspective.

To address gaps in the literature and better conceptualize familial dysfunction across development, the current study examined family functioning in youths with BD, adults with prospectively verified childhood-onset BD, and youth and adult HCs. Adults with BD were followed since childhood via their participation in the Brown University site of the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study to ensure that retrospective recall bias did not impact BD diagnoses (Birmaher et al., 2009; Leboyer et al., 2005). Hypotheses were based on research documenting a more severe course of illness and functional impairment in youths vs. adults with BD (Birmaher et al., 2009; Geller et al., 2008; Perlis et al., 2009; Perlis et al., 2004). In addition, youths likely had less time to seek treatment and develop strategies for managing symptoms/stressors than adults with childhood-onset BD, given longer duration of illness in the latter, potentially contributing to exacerbated family dysfunction at younger ages. Thus, it was hypothesized that: 1) youths and young adults with childhood-onset BD would demonstrate impaired family functioning compared to HCs; and 2) youths with BD would display worse family functioning compared to adults with childhood-onset BD.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were enrolled in one of two studies approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Bradley Hospital and Brown University. Written informed parental consent and child assent were obtained for youths; written informed consent was obtained for adults. Subsequently, parents, youths, and adults completed assessments and measures cross-sectionally. The sample included 116 individuals with childhood-onset BD (70 youths, 46 adults) and 108 HCs (46 youths, 62 adults).

Inclusion criteria for participants with BD were: 1) ages 7–17 (youths) or 18–30 (adults); 2) English fluency; and 3) diagnosis of BD per the DSM-IV-TR. Youths with BD were recruited for a study that compared youths with BD vs. HCs, and were required to have BD-I (n=68) or BD-(II n=2). Adults with BD were originally enrolled as youths in the Brown University site of the COBY study, prior to enrolling in the current study. The COBY study required a diagnosis of BD-I (n=28), BD-II (n=3), or BD-Not Otherwise Specified (NOS) (n=15); the latter was defined as elation plus two associated symptoms or irritability plus three associated symptoms, change in functioning, ≥ 4 hours within a 24-hour period, ≥ 4 cumulative lifetime days (Birmaher et al., 2006). Thus, adults’ diagnoses of childhood-onset BD were prospectively confirmed. Exclusion criteria were: 1) full scale IQ (FSIQ) < 70 on the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) (Wechsler, 2005); 2) autism spectrum disorder or primary psychosis; and 3) medical/neurological conditions potentially mimicking BD.

Inclusion criteria for HCs were: 1) ages 7–17 (youths) or 18–30 (adults); 2) English fluency; and 3) no current/lifetime psychiatric illness or substance abuse/dependence in participants or first-degree relatives. Exclusion criteria were: 1) FSIQ < 70; 2) learning disorders or autism spectrum disorder; and 3) serious, non-psychiatric medical disorders potentially mimicking/confounding psychiatric illness.

Measures

Family functioning

Current family functioning was assessed via youth/adult participant report on the Family Assessment Device (FAD) (Epstein et al., 1983), consisting of 60 items and seven subscales: 1) Problem Solving—family’s ability to address problems adaptively; 2) Communication—style and clarity of verbal information sharing; 3) Roles—established behavior patterns to fulfill family functions; 4) Affective Responsiveness—family members’ ability to experience appropriate affect across situations; 5) Affective Involvement—interest and value placed on family members’ behaviors and concerns; 6) Behavior Control—the way family members maintain expectations for each other; and 7) General Functioning—overall summary of family processes. Items are averaged to produce a summary score for each subscale ranging from one to four; higher scores indicate poorer functioning, and scores above two suggest clinical severity. The FAD has demonstrated good reliability and validity across ages and populations (Miller et al., 1985; Pritchett et al., 2011; Staccini et al., 2015; Youngstrom et al., 2011).

Demographic information

Parents reported on youths’ age, race, current medications, and socioeconomic status (SES), categorized according to the Hollingshead Index (Hollingshead, 1975). Adult participants reported on these variables for themselves. Youth and adult participants were administered the WASI (Wechsler, 2005) by trained research assistants to measure IQ.

Psychiatric diagnoses

Participants’ current and past psychiatric diagnoses were evaluated using the Child Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, Present and Lifetime Version (Kaufman et al., 1997) for youths and parents, or the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First et al., 2002) for adults. These semi-structured interviews were conducted by a board-certified child/adolescent psychiatrist or a licensed clinical psychologist with established inter-rater reliability (κ>.85).

Mood and global functioning

To characterize mood and functioning, participants with BD were assessed via the clinician-administered Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (Young et al., 1978) for youths and adults, the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R) (Poznanski et al., 1984) for youths, and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) (Hamilton, 1960) for adults. These scales have well established reliability and validity (Poznanski et al., 1984; Trajkovic et al., 2011; Young et al., 1978). Higher scores indicate greater severity. As depression symptoms were measured using different scales, sample-specific z-scores were created for analyses (Wegbreit et al., 2016; Wegbreit et al., 2015). Functional impairment was assessed via the clinician-rated Children’s Global Assessment Scale (Shaffer et al., 1983) for youths and the Global Assessment Scale of Functioning (Hall, 1995) for adults (scores range from 1–100; 100 indicates superior functioning).

Analytic Strategy

Analyses were implemented in SPSS 22 with two-tailed comparisons and a .05 significance criterion. First, independent samples t-tests and chi-square analyses were used to compare demographic, clinical, and family functioning variables in: 1) participants with BD vs. HCs; and 2) youths vs. adults with BD.

Then, to determine whether different factors influenced the effect of diagnosis on family functioning, two sets of analyses were conducted to examine age as a categorical and continuous predictor, based on prior work (Wegbreit et al., 2015), and due to differences between youths vs. adults with BD (see Results). First, multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was used to examine age categorically, such that age group (youths vs. adults), diagnosis, and the diagnosis-by-age interaction were fixed factors, and FAD subscales were dependent variables. Any demographic variables that significantly differed between participants with BD vs. HCs were included as covariates. Given significant main or interaction effects, tests of between-subject effects were conducted. Next, multiple linear regression was used to examine age continuously, with diagnosis, age, and the diagnosis-by-age interaction included in models examining individual FAD subscales, along with demographics that differed between participants with BD vs. HCs. All independent variables were standardized to reduce multi-collinearity, and standardized beta-weights were reported to facilitate interpretable and direct comparisons between regressions (Cohen et al., 2003).

Lastly, to avoid a possible issue with multiple comparisons, following aforementioned primary analyses post-hoc regressions were conducted to measure effects of potentially confounding variables (mood state, global functioning, comorbidity, medication).

Results

Demographics

There were no differences between participants with BD vs. HCs for sex and race (Tables 1 and 2). Collapsing across ages, participants with BD were younger and had lower FSIQ than HCs; there was no difference in Hollingshead-categorized SES (Table 1). When examining demographics across diagnostic groups by age groups, youths with BD had significantly lower FSIQ and SES than youth HCs; there was no difference in age (Table 2). Adults with BD were significantly younger and had significantly lower SES than adult HCs; there was no difference in FSIQ. To be conservative, all MANCOVA and regression analyses covaried for FSIQ and SES.

Table 1.

Demographics and Family Functioning for Participants with Bipolar Disorder vs. Healthy Controls

| Variables | Bipolar Disorder (n=116) |

Healthy Control (n=108) |

Statistic χ2/t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, M(SD) | 16.51(4.80) | 18.17(5.56) | −2.40* |

| Sex (Male), n(%) | 67(58) | 57(53) | 0.56 |

| Race (Caucasian), n(%)a | 96(86) | 83(82) | 0.50 |

| Full-Scale IQ, M(SD) | 106.16(11.96) | 113.11(12.59) | −4.23*** |

| Socioeconomic Status, M(SD)b | 36.37(15.80) | 39.23(15.77) | −1.33 |

| Family Functioning | |||

| Problem Solving, M(SD) | 2.18(0.47) | 1.93(0.43) | 4.20*** |

| Communication, M(SD) | 2.23(0.44) | 2.00(0.43) | 4.00*** |

| Roles, M(SD) | 2.33(0.38) | 2.00(0.35) | 6.62*** |

| Affective Responsiveness, M(SD) | 2.17(0.55) | 1.97(0.56) | 2.72** |

| Affective Involvement, M(SD)c | 2.34(0.49) | 1.96(0.44) | 6.06*** |

| Behavior Control, M(SD) | 1.89(0.41) | 1.71(0.40) | 3.20** |

| General Functioning, M(SD) | 2.10(0.51) | 1.72(0.46) | 5.87*** |

Race was missing or not reported by four participants with bipolar disorder and seven healthy controls.

Socioeconomic status was missing from five participants with bipolar disorder and two healthy controls.

Affective involvement was missing from one participant with bipolar disorder.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Table 2.

Demographics for Participants with Bipolar Disorder vs. Healthy Controls by Age Group

| Youths

|

Adults

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Bipolar Disorder (n=70) |

Healthy Control (n=46) |

Statistic χ2/t |

Bipolar Disorder (n=46) |

Healthy Control (n=62) |

Statistic χ2/t |

| Age, M(SD) | 13.46(3.09) | 12.64(3.41) | 1.33 | 21.16(2.77) | 22.27(2.35) | −2.25* |

| Sex (Male), n(%) | 39(56) | 20(43) | 1.66 | 28(61) | 37(60) | 0.02 |

| Race (Caucasian), n(%)a | 60(88) | 35(83) | 0.53 | 36(82) | 48(81) | 0.00 |

| Full-Scale IQ, M(SD) | 105.03(11.19) | 115.71(12.59) | −4.79*** | 107.89(13.00) | 111.18(12.34) | −1.34 |

| Socioeconomic Status, M(SD)b | 42.82(14.46) | 49.24(13.08) | −2.39* | 25.79(11.75) | 32.13(13.56) | −2.47* |

Race was missing or not reported by two youth and two adult participants with bipolar disorder and four youth and three adult healthy controls.

Socioeconomic status was missing from one youth and four adult participants with bipolar disorder and two youth healthy controls.

p<.05;

p<.001

When comparing youths vs. adults with BD, youths had significantly higher SES; there were no differences in sex, race, and FSIQ (Table 3). In addition, youths with BD had more severe manic symptoms, more comorbidities (except substance use disorders), worse global functioning, and were more likely to be taking psychotropic medications. There were no group differences in age of onset of BD, mood state (mostly euthymic), and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and anxiety.

Table 3.

Demographic, Family Functioning, and Clinical Characteristics of Participants with Bipolar Disorder by Age Group

| Variables | Youths with Bipolar Disorder (n=70) |

Adults with Bipolar Disorder (n=46) |

Statistic χ2/t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, M(SD) | 13.46(3.09) | 21.16(2.77) | −13.67*** |

| Sex (Male), n(%) | 39(56) | 28(61) | 0.30 |

| Race (Caucasian), n(%)a | 60(88) | 36(82) | 0.90 |

| Full-Scale IQ, M(SD) | 105.03(11.19) | 107.89(12.99) | −1.26 |

| Socioeconomic Status, M(SD)b | 42.82(14.46) | 25.79(11.75) | 6.45*** |

| Family Functioning | |||

| Problem Solving, M(SD) | 2.14(0.47) | 2.25(0.46) | −1.24 |

| Communication, M(SD) | 2.23(0.48) | 2.23(0.37) | 0.02 |

| Roles, M(SD) | 2.29(0.35) | 2.40(0.43) | −1.47 |

| Affective Responsiveness, M(SD) | 2.03(0.46) | 2.38(0.62) | −3.44** |

| Affective Involvement, M(SD)c | 2.28(0.49) | 2.43(0.48) | −1.57 |

| Behavior Control, M(SD) | 1.81(0.42) | 2.00(0.36) | −2.46* |

| General Functioning, M(SD) | 2.03(0.47) | 2.21(0.54) | −1.92 |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||

| Age of Onset of Bipolar Disorder, M(SD)d | 10.25(3.70) | 9.78(3.63) | 0.64 |

| Duration of Bipolar Disorder, M(SD)e | 3.16(3.11) | 11.20(3.04) | −13.25*** |

| Mania, M(SD)f | 9.29(6.50) | 4.33(2.82) | 4.82*** |

| Global Functioning, M(SD) | 57.33(13.31) | 63.91(11.23) | −2.77** |

| Mood State (Euthymic), n(%)g | 46(66) | 36(80) | 2.73 |

| Currently Medicated (Yes), n(%)h | 63(90) | 21(47) | 26.12*** |

| Comorbid Conditions, M(SD) | 2.57(1.49) | 1.83(1.39) | 2.71** |

| Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, n(%) | 42(60) | 24(52) | 0.69 |

| Any Anxiety Disorder, n(%) | 43(61) | 21(46) | 2.79 |

| Substance Use Disorder, n(%) | 0(0) | 19(41) | 34.58*** |

Race was missing or not reported by two youths and two adults with bipolar disorder.

Socioeconomic status was missing from one youth and four adults with bipolar disorder.

Affective involvement was missing from one youth with bipolar disorder.

Age of onset of bipolar disorder was missing from five youths and three adults with bipolar disorder.

Duration of bipolar disorder was missing from five youths and three adults with bipolar disorder.

Mania score was missing for one adult with bipolar disorder.

Mood state was missing for one adult with bipolar disorder.

Medication status was missing from one adult with bipolar disorder.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Between-Group Differences in Family Functioning

In independent samples t-tests of FAD subscales, participants with BD demonstrated significantly more impairments in all family functioning domains compared to HCs (problem solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, behavior control, general functioning) (Table 1). When comparing youths vs. adults with BD, adults had significantly worse affective responsiveness and behavior control compared to youths (Table 3).

Differences in Family Functioning with Age as a Categorical Predictor

In MANCOVA analyses of FAD subscales, there was a significant effect for diagnosis [F(7,204)=7.11, p<.001] and age [F(7,204)=3.93, p<.001], but not for the diagnosis-by-age interaction [F(7,204)=1.64, p=.13]. The covariates of FSIQ [F(7,204)=1.49, p=.17] and SES [F(7,204)=1.43, p=.19] were not significant.

Diagnosis was significant for all FAD subscales: problem solving [F(1,210)=18.22, p<.001], communication [F(1,210)=10.76, p=.001], roles [F(1,210)=36.26, p<.001], affective responsiveness [F(1,210)=7.04, p=.01], affective involvement [F(1,210)=27.47, p<.001], behavior control [F(1,210)=7.40, p=.01], and general functioning [F(1,210)=32.60, p<.001].

Age was significant for affective responsiveness [F(1,210)=7.74, p=.01], behavior control [F(1,210)=4.81, p=.03], and general functioning [F(1,210)=4.50, p=.04]. Specifically, presence of BD and older age were associated with increased impairment.

Differences in Family Functioning with Age as a Continuous Predictor

In regression analyses of FAD subscales, all models showed a significant effect for diagnosis (Table 4). Presence of BD was associated with more impaired family problem solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, behavior control, and general functioning. Older age was associated with worse affective responsiveness and behavior control, and lower SES was associated with deficiencies in roles and affective responsiveness. FSIQ and the diagnosis-by-age interaction were not significant.

Table 4.

Primary Regression Analyses of Family Functioning for Participants with Bipolar Disorder vs. Healthy Controls

| Problem Solving |

Communication | Roles | Affective Responsiveness |

Affective Involvement |

Behavior Control |

General Functioning |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Effect | β | t(216) | β | t(216) | β | t(216) | β | t(216) | β | t(215) | β | t(216) | β | t(216) |

| Diagnosis | 0.29 | 4.18*** | 0.24 | 3.40** | 0.41 | 6.16*** | 0.17 | 2.48* | 0.36 | 5.41*** | 0.19 | 2.74** | 0.37 | 5.50*** |

| Age | 0.10 | 1.38 | 0.03 | 0.35 | −0.05 | −0.70 | 0.17 | 2.39* | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.19 | 2.70** | 0.09 | 1.30 |

| Diagnosis x Age | −0.09 | −1.41 | −0.09 | −1.26 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.05 | 0.72 | 0.08 | 1.26 | −0.02 | −0.29 | −0.02 | −0.30 |

| FSIQ | 0.06 | 0.91 | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.84 | −0.08 | −1.12 | −0.09 | −1.30 | −0.07 | −0.94 | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| SES | −0.09 | −1.28 | −0.07 | −1.02 | −0.14 | −2.13* | −0.16 | −2.23* | −0.03 | −0.49 | −0.09 | −1.35 | −0.08 | −1.12 |

Note. FSIQ=Full-Scale IQ; SES=Socioeconomic Status.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Post-Hoc Analyses: Effect of Mood State and Global Functioning

To examine potential effects of mood state and global functioning, follow-up regressions were conducted. First, non-euthymic participants with BD were excluded (n=24 youths, 9 adults, 1 adult with missing data). Non-euthymic participants were defined by YMRS ≥ 13 for youths and adults and/or CDRS-R ≥ 40 for youths, HAM-D ≥ 8 for adults (Zimmerman et al., 2013). Next, participants with BD-II (n=2 youths, 3 adults) and BD-NOS (n=15 adults) were excluded, thus comparing participants with BD-I vs. HCs. In these models, diagnosis remained significant for all FAD subscales, older age remained significant for affective responsiveness and behavior control, but lower SES was no longer significant for roles and affective responsiveness (Supplementary Table 1). FSIQ and the diagnosis-by-age interaction remained non-significant. Thus, familial dysfunction was apparent for participants with BD regardless of current mood state or BD subtype.

Within-group regressions were also conducted with participants with BD, including covariates for depression, mania, global functioning, and duration of BD (in lieu of age) separately. These analyses controlled for SES, but not FSIQ (as the latter did not significantly differ between groups). None of these covariates were associated with family functioning (Supplementary Table 2). Consistent with primary analyses, older age predicted worse affective responsiveness when including most clinical correlates, and when substituting duration of BD for age. Also, lower SES predicted impairment in roles in all models. These findings provide further evidence that mood symptoms, global functioning, and duration of BD did not impact observed family deficits.

Post-Hoc Analyses: Effect of Comorbid Conditions and Substance Use Disorders

To examine potential effects of comorbidity, within-group regressions were conducted with participants with BD, including covariates for number of comorbid conditions and presence of ADHD, anxiety, and substance use disorders (SUDs) separately, controlling for SES. No comorbidities were associated with family functioning (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). When controlling for number of comorbidities, older age no longer predicted worse affective responsiveness (Supplementary Table 2). However, this association remained significant when controlling for ADHD, anxiety, and SUDs (Supplementary Table 3). Similar to primary analyses, lower SES predicted worse functioning in roles in all models. Thus, comorbidities did not influence the relationship between childhood-onset BD and family impairments.

Post-Hoc Analyses: Effect of Medications

To examine potential effects of medications, within-group regressions were conducted with participants with BD, including a covariate for presence of psychiatric medications, controlling for SES. Presence of medication was not associated with family functioning (Supplementary Table 2). Also, lower SES no longer predicted worse affective responsiveness, and older age no longer predicted worse behavior control. Similar to primary analyses, lower SES predicted impairment in roles, and older age predicted worse affective responsiveness. Thus, presence of medications did not affect findings pertaining to family dysfunction in youths and adults with BD.

To further examine potential effects of medications, follow-up regressions were conducted excluding participants taking each medication class sequentially (lithium, atypical antipsychotics, antiepileptics, antidepressants, stimulants, non-stimulants). Results were generally consistent with primary analyses (Supplementary Table 4). Presence of BD diagnosis remained significantly associated with greater impairment for most FAD subscales, as did older age for worse behavior control and affective responsiveness. However, the relationship between lower SES and impaired familial roles and affective responsiveness varied depending on the medication class excluded.

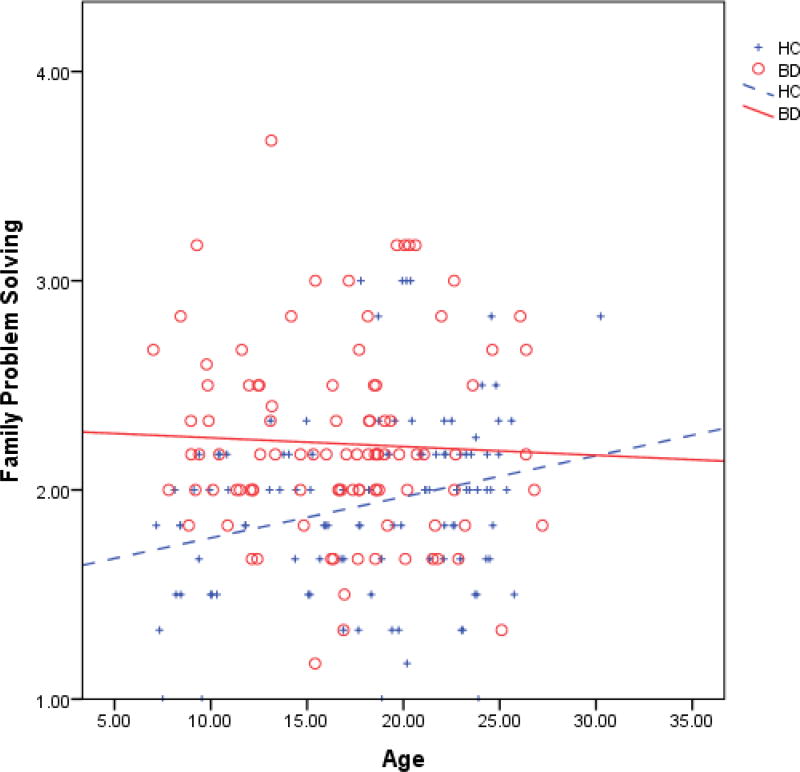

A significant diagnosis-by-age interaction occurred for family problem solving and communication when excluding participants taking lithium at time of study (n=14 youths, 2 adults, 1 adult with missing data). Follow-up regressions for problem solving by diagnosis (controlling for SES) revealed a significant effect of age in HCs: older age predicted more impaired problem solving in HCs [β=0.25, t (105)=2.47, p=.02], but there was not a significant age effect for participants with BD [β=−0.09, t(94)=−0.85, p=.40]. SES was not significant. Thus, both youths and adults with BD (excluding those taking lithium) appear impaired in family problem solving, regardless of age, while older HCs demonstrated worse family problem solving than younger HCs, creating a larger discrepancy in youths with BD vs. youth HCs than adults with BD vs. adult HCs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Family problem solving for individuals with bipolar disorder vs. healthy controls, excluding those taking lithium (n=14 youths, 2 adults, 1 adult with missing data). HC=Healthy Control; BD=Bipolar Disorder.

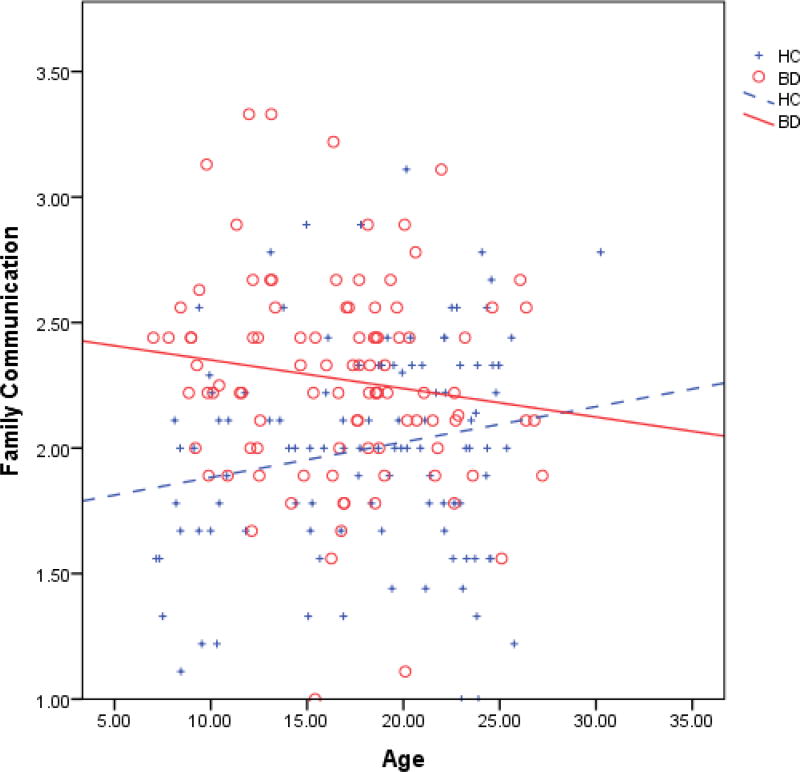

Follow-up regressions for communication by diagnosis (controlling for SES) demonstrated a non-significant effect of age in HCs [β=0.15, t(105)=1.45, p=.15] and participants with BD [β=−0.18, t(94)=−1.67, p=.10]. SES was not significant. The direction of effects suggest that family communication may improve with age for participants with BD, while communication may worsen into adulthood for HCs, creating a greater discrepancy in youths with BD vs. youth HCs than adults with BD vs. adult HCs (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Family communication for individuals with bipolar disorder vs. healthy controls, excluding those taking lithium (n=14 youths, 2 adults, 1 adult with missing data). HC=Healthy Control; BD=Bipolar Disorder.

Notably, participants with BD taking lithium reported significantly better family problem solving [t(113)=−2.39, p=.02] and communication [t(113)=−2.51, p=.01] than participants not taking lithium, despite having significantly higher mania scores [t(112)=2.93, p=.004]. Differences in global functioning [t(113)=0.08, p=.94], and depression for youths [t(68)=0.89, p=.38] and adults [t(43)=1.38, p=.18] were not significant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to take a developmental approach to investigate family functioning in youths and young adults with prospectively verified childhood-onset BD. Results indicated that participants with BD had significantly worse family functioning in all domains (problem solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, behavior control, general functioning) compared to HCs, even when controlling for SES and FSIQ. The hypothesized diagnosis-by-age interaction in family functioning was not observed in primary analyses. Rather, family dysfunction was comparable in youths and adults with childhood-onset BD. In addition, there was no influence for mood state, global functioning, comorbidity, and most medications, despite youths with BD presenting with greater severity in these areas than adults with BD. Post-hoc analyses eliminating participants taking lithium revealed a significant diagnosis-by-age interaction, such that youths with BD had worse family problem solving and communication relative to youth HCs. Collectively, findings suggest that familial dysfunction is a substantial and enduring deficit in childhood-onset BD, which should be targeted in treatment across development, with potential for increased impairment and the need for greater supports in youths.

Findings add to the literature on familial processes in childhood-onset BD and suggest that family functioning deficits are robust and salient into young adulthood (Belardinelli et al., 2008; Keenan-Miller et al., 2012; Nader et al., 2013; Perez Algorta et al., 2017; Schenkel et al., 2008). This is important and concerning, as family factors are associated with onset and worse course of BD in youths (Geller et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2007; Siegel et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2012) and adults (Kim and Miklowitz, 2004; O’Connell et al., 1991; Yan et al., 2004), and influence psychosocial treatment outcomes (MacPherson et al., 2016; Mendenhall et al., 2009; Miklowitz et al., 2009; Reinares et al., 2016b; Sullivan et al., 2012; Weinstein et al., 2015).

Although a significant diagnosis-by-age interaction was not observed in primary analyses, between-group comparisons revealed that adults with BD had more impaired family affective responsiveness and behavior control than youths with BD. It is possible that these dimensions are particularly challenging for adults with BD and their families of origin (parents and/or siblings with whom they grew up) to navigate as they transition to adulthood, seek independence, and redefine their relationships. Or, in the context of their current families, adults with BD may experience difficulty interacting with their partners and/or children, potentially replicating dysfunctional familial processes from their childhood. Thus, these impairments may be important to assess and target in treatment of young adults with childhood-onset BD. Specifically, discussing and role-playing appropriate and effective emotional displays to situations (and understanding others’ points of view) may be beneficial, in addition to clearly defining relationships, roles, and responsibilities with both current partners/children and families of origin. Similarly, these dimensions should be evaluated and addressed in youths with BD, as early identification and intervention may prevent worsening of these processes. Interestingly, older age was associated with poorer familial affective responsiveness, behavior control, and general functioning, while lower SES predicted worse affective responsiveness and roles. Thus, individuals with childhood-onset BD in addition to these demographics may experience compounded familial dysfunction, and thus may require more intensive intervention.

Importantly, family functioning deficits were apparent despite most participants with BD being euthymic, and when controlling for symptom severity, global functioning, comorbidity, and most medications. In addition, family deficits were generally equivalent across age groups in primary analyses, even though youths with BD had more severe mania, more comorbidities, worse global functioning, and higher psychotropic medication usage. Research has documented that when individuals with BD are in remission, considerable psychosocial, global, and neurocognitive deficits remain (Gitlin and Miklowitz, 2017; Goldstein et al., 2009; Reinares et al., 2016a). The current study adds to these findings by indicating that family dysfunction also endures despite symptomatic reduction, and remains problematic in young adults with childhood-onset BD. Thus, EBTs should target not only symptoms, but also family-level factors (Reinares et al., 2016b). Indeed, current psychosocial EBTs for childhood-onset BD emphasize family involvement in treatment (Fristad and MacPherson, 2014). However, as dismantling studies have not been conducted, it is unclear which family-based components are most effective, or if novel family strategies are necessary. As psychosocial treatment information was not collected in this study, it is unclear what psychotherapies participants received, or if these influenced findings.

While post-hoc tests generally yielded similar results as primary analyses, a significant diagnosis-by-age interaction occurred for family problem solving and communication when excluding participants taking lithium. There was a greater discrepancy in youths with BD vs. youth HCs than adults with BD vs. adult HCs. Thus, family communication and problem solving should be targeted in treatment of youths with BD, and indeed, existing EBTs incorporate strategies for addressing these factors (Fristad et al., 2009; Miklowitz et al., 2008; West et al., 2014). These results should be considered preliminary, as they are the only analyses that revealed a significant diagnosis-by-age interaction, based on elimination of 17 individuals (mostly youths). Though, it is notable that among participants with BD, those taking lithium reported superior family problem solving and communication compared to those not taking lithium, despite having higher mania scores. Lithium usage in adults with BD is associated with improved cognition and psychosocial functioning (Daglas et al., 2016; Pompili et al., 2014). If similar effects occur in youths taking lithium, this may influence families’ willingness and ability to engage with youths, who may be functioning better and more able to constructively participate in family discussions/activities, thereby reciprocally facilitating improved family problem solving and communication. However, as the relationship between lithium, cognition, psychosocial functioning, and family functioning was not assessed, these hypotheses are purely speculative.

Another possible explanation is that youths prescribed lithium may have been more ill and involved in more extensive treatment, given higher mania scores in those prescribed lithium, and since lithium is often not the frontline recommended pharmacological agent for youths (Liu et al., 2011). Illness severity may have motivated parents to seek EBTs, create a safe/supportive home environment, and/or enact effective parenting strategies to promote health and stability in their children. As aforementioned, family problem solving and communication are targeted in EBTs for childhood-onset BD, so these families may have learned strategies for improving these domains. In addition, families of less acute children may have been fatigued from previously caring for the child when in a more symptomatic/impaired state, and thus when offered respite via reduction in the child’s symptoms, were less diligent about implementing effective parenting strategies, and perhaps frustrated with family turmoil associated with childhood-onset BD. These suppositions are hypothetical, as data on psychotherapeutic treatments and observed family processes were not collected.

Findings suggest that a diagnosis-by-age interaction may exist in developmental samples of childhood-onset BD, with increased impairment in family problem solving and communication in youths. Thus, as recommended in current EBTs for childhood-onset BD (Fristad and MacPherson, 2014), family communication and problem solving deficits should be directly addressed via practicing effective verbal and nonverbal communication, and teaching strategies for identifying family problems and triggers, brainstorming and evaluating potential solutions, and selecting and following-through with plans for specified issues. Nevertheless, familial dysfunction seems to persist into young adulthood, underscoring the need for better understanding of family-based mechanisms in childhood-onset BD, and the development and/or refinement of therapeutic strategies to target these deficits.

While needing replication, our work suggests that future studies should probe brain/behavior mechanisms underlying problem solving and communication in those with childhood-onset BD, as these abilities appear impaired at both the individual and family level. In turn, better understanding of these processes could facilitate development of targeted, mechanism-focused treatments that may be more effective and efficient than existing interventions. For instance, individuals with childhood-onset BD display deficits in both reversal learning (Wegbreit et al., 2016) and facial emotion recognition (Wegbreit et al., 2015). Indeed, the ability to think flexibly, adapt to changing circumstances, recognize others’ emotions, and modulate one’s affective response are linked to problem solving and communication capabilities, and thus may partially explain deficits in these domains. As such, cognitive remediation has been proposed as a promising new treatment for childhood-onset BD, to target specific neurocognitive impairments tied to dysfunction (Dickstein et al., 2015).

If research discerns similar parent-based brain/behavior mechanisms linked to parental psychopathology and familial dysfunction in childhood-onset BD (such as problem solving and communication), adjunctive parental cognitive remediation may enhance the efficacy, effectiveness, and efficiency of EBTs by targeting neurocognitive/learning impairments based on individual parent capacities/profiles, thereby facilitating acquisition and implementation of therapeutic strategies. Parent-based cognitive remediation could also enhance dissemination, as computerized interventions can be administered broadly without reliance on mental health professionals, and could serve to shorten the length of psychosocial intervention required, if therapeutic skills are more swiftly learned and applied via targeting parental neurocognitive deficits. Thus, future research should examine parent and family deficits across units of analysis, with a focus on neurocognition and brain functioning, to inform specific impairments and thereby novel targets for innovative treatments, such as parent-based, adjunctive cognitive remediation.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. First, this study employed a cross-sectional design, though longitudinal work would offer more nuanced information regarding trajectories of family functioning, and predictors of worsening or abatement. Second, clinical differences in youths vs. adults with BD may have influenced findings, as youths demonstrated increased impairment, though post-hoc tests examining the impact of clinical variables on family functioning were not significant. Third, there is potential ambiguity in FAD instructions, which state “Read each statement carefully, and decide how well it describes your own family.” While likely that most participants completed this based on their families of origin, it is possible that some adults completed this based on their current living partners or their own children, though it is unknown how many adults had nuclear families of their own. This is consistent with prior research on family functioning in adults with BD, which often incorporates a mix of familial caregivers (e.g., parents, spouses, close relatives) (Miklowitz, 2011; Miklowitz and Johnson, 2009). Nevertheless, FAD results from adults may indicate global interpersonal impairment, and potential replication of dysfunctional interaction patterns from families of origin, though future work should confirm this. Finally, only youth and adult participants reported on family functioning, which may have offered a narrow or skewed view of the home environment. Future studies would benefit from augmenting the FAD with additional assessments of parental psychopathology, multi-informant report of familial processes, and participant treatment usage, so as to better characterize family functioning in those with vs. without BD.

Conclusions

Individuals with childhood-onset BD exhibit robust deficits in family functioning, which generalize across the developmental transition from childhood to young adulthood, regardless of mood state, global functioning, comorbidity, and most medications. Family affective responsiveness and behavior control may be more impaired in adults with childhood-onset BD, while family problem solving and communication may be most salient for youths with BD. Future research should replicate findings, examine family functioning longitudinally in childhood-onset BD, incorporate several informants, and evaluate the impact of psychosocial treatments on family dimensions (and vice versa). Mediational work suggests that improvement in family factors is possible with family-based psychosocial EBTs for childhood-onset BD, and associated with improvement in children’s mood and functioning (MacPherson et al., 2016; Mendenhall et al., 2009). Thus, further investigation into multi-level, family-based mechanisms underlying childhood-onset BD may broaden our understanding of the role family factors play in childhood-onset BD, and thereby offer avenues for the development of novel, pointed family-focused strategies to enhance existing EBTs, such as personalized, parent-based cognitive remediation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We examined family functioning in youths and adults with childhood-onset bipolar disorder (BD).

Family functioning was worse in participants with BD vs. healthy controls, regardless of demographics.

There was no influence for mood, global functioning, comorbidity, and most medications.

Removing those taking lithium showed a significant diagnosis-by-age interaction.

Youths with BD had worse family problem solving and communication relative to healthy controls.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge and thank the youths, young adults, and their families for their time and effort participating in these studies, without which this research would not be possible.

Role of the Funding Source

This study was supported by Emma Pendleton Bradley Hospital and the National Institute of Mental Health grants K22MH074945 and R01MH087513 (Principal Investigator Daniel P. Dickstein). Young adult participants with bipolar disorder were recruited from Brown University’s site of the Course and Outcome in Bipolar Youth (COBY) study (R01MH059929). The funders had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Statement

Contributors

Heather A. MacPherson and Daniel P. Dickstein conceptualized the current study. Heather A. MacPherson conducted all statistical analyses, led the literature search, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, as well as reformulated each following draft.

Amanda L. Ruggieri and Rachel E. Christensen constructed and organized the database file for these analyses and assisted with data cleaning.

Amanda L. Ruggieri, Rachel E. Christensen, Elana Schettini, Kerri L. Kim, and Sarah A. Thomas assisted in preparing and editing the manuscript for submission.

Daniel P. Dickstein supervised the current study and provided mentorship (including contributing to and editing drafts) throughout. He also wrote the protocols and obtained grant funding for the studies from which the sample and data for the current paper are drawn.

All authors have contributed to and approved the current version of the manuscript.

References

- Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Strober MA, Goldstein BI, Ha W, Gill MK, Goldstein TR, Yen S, Hower H, Hunt JI, Liao F, Iyengar S, Dickstein D, Kim E, Ryan ND, Frankel E, Keller MB. Course of subthreshold bipolar disorder in youth: diagnostic progression from bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:1001–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.07.005. e1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardinelli C, Hatch JP, Olvera RL, Fonseca M, Caetano SC, Nicoletti M, Pliszka S, Soares JC. Family environment patterns in families with bipolar children. J Affect Disord. 2008;107:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, Strober M, Gill MK, Hunt J, Houck P, Ha W, Iyengar S, Kim E, Yen S, Hower H, Esposito-Smythers C, Goldstein T, Ryan N, Keller M. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:795–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08101569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Keller M. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:175–183. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Gill MK, Axelson DA, Goldstein BI, Goldstein TR, Yu H, Liao F, Iyengar S, Diler RS, Strober M, Hower H, Yen S, Hunt J, Merranko JA, Ryan ND, Keller MB. Longitudinal trajectories and associated baseline predictors in youths with bipolar spectrum disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:990–999. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13121577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ, US: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Daglas R, Cotton SM, Allott K, Yucel M, Macneil CA, Hasty MK, Murphy B, Pantelis C, Hallam KT, Henry LP, Conus P, Ratheesh A, Kader L, Wong MT, McGorry PD, Berk M. A single-blind, randomised controlled trial on the effects of lithium and quetiapine monotherapy on the trajectory of cognitive functioning in first episode mania: A 12-month follow-up study. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;31:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.09.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein DP, Cushman GK, Kim KL, Weissman AB, Wegbreit E. Cognitive remediation: potential novel brain-based treatment for bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. CNS Spectr. 2015;20:382–390. doi: 10.1017/S109285291500036X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9:171–180. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Miriam G, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition with Psychotic Screen. New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, MacPherson HA. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent bipolar spectrum disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43:339–355. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.822309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, Verducci JS, Walters K, Young ME. Impact of multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy in treating children aged 8 to 12 years with mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1013–1021. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Tillman R, Bolhofner K, Zimerman B. Child bipolar I disorder: prospective continuity with adult bipolar I disorder; characteristics of second and third episodes; predictors of 8-year outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1125–1133. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.10.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin MJ, Miklowitz DJ. The difficult lives of individuals with bipolar disorder: A review of functional outcomes and their implications for treatment. J Affect Disord. 2017;209:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein BI, Gill MK, Esposito-Smythers C, Ryan ND, Strober MA, Hunt J, Keller M. Psychosocial functioning among bipolar youth. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall RC. Global assessment of functioning. A modified scale. Psychosomatics. 1995;36:267–275. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71666-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan-Miller D, Peris T, Axelson D, Kowatch RA, Miklowitz DJ. Family functioning, social impairment, and symptoms among adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:1085–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Miklowitz DJ. Expressed emotion as a predictor of outcome among bipolar patients undergoing family therapy. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Miklowitz DJ, Biuckians A, Mullen K. Life stress and the course of early-onset bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;99:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leboyer M, Henry C, Paillere-Martinot ML, Bellivier F. Age at onset in bipolar affective disorders: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:111–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverich GS, Post RM, Keck PE, Jr, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Kupka RW, Nolen WA, Suppes T, McElroy SL, Grunze H, Denicoff K, Moravec MK, Luckenbaugh D. The poor prognosis of childhood-onset bipolar disorder. J Pediatr. 2007;150:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HY, Potter MP, Woodworth KY, Yorks DM, Petty CR, Wozniak JR, Faraone SV, Biederman J. Pharmacologic treatments for pediatric bipolar disorder: a review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.05.011. e739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson HA, Weinstein SM, Henry DB, West AE. Mediators in the randomized trial of Child- and Family-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for pediatric bipolar disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2016;85:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendenhall AN, Fristad MA, Early TJ. Factors influencing service utilization and mood symptom severity in children with mood disorders: effects of multifamily psychoeducation groups (MFPGs) J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:463–473. doi: 10.1037/a0014527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ. Functional impairment, stress, and psychosocial intervention in bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13:504–512. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Axelson DA, Birmaher B, George EL, Taylor DO, Schneck CD, Beresford CA, Dickinson LM, Craighead WE, Brent DA. Family-focused treatment for adolescents with bipolar disorder: results of a 2-year randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1053–1061. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.9.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Axelson DA, George EL, Taylor DO, Schneck CD, Sullivan AE, Dickinson LM, Birmaher B. Expressed emotion moderates the effects of family-focused treatment for bipolar adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:643–651. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a0ab9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Johnson SL. Social and Familial Factors in the Course of Bipolar Disorder: Basic Processes and Relevant Interventions. Clin Psychol. 2009;16:281–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller IW, Epstein NB, Bishop DS, Keitner GI. The McMaster Family Assessment Device: Reliability and validity. J Marital Fam Ther. 1985;11:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Nader EG, Kleinman A, Gomes BC, Bruscagin C, dos Santos B, Nicoletti M, Soares JC, Lafer B, Caetano SC. Negative expressed emotion best discriminates families with bipolar disorder children. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell RA, Mayo JA, Flatow L, Cuthbertson B, O’Brien BE. Outcome of bipolar disorder on long-term treatment with lithium. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:123–129. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Algorta G, MacPherson HA, Youngstrom EA, Belt CC, Arnold LE, Frazier TW, Taylor HG, Birmaher B, Horwitz SM, Findling RL, Fristad MA. Parenting Stress Among Caregivers of Children With Bipolar Spectrum Disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017:1–15. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1280805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Dennehy EB, Miklowitz DJ, Delbello MP, Ostacher M, Calabrese JR, Ametrano RM, Wisniewski SR, Bowden CL, Thase ME, Nierenberg AA, Sachs G. Retrospective age at onset of bipolar disorder and outcome during two-year follow-up: results from the STEP-BD study. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:391–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00686.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, Wisniewski SR, Ostacher M, DelBello MP, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA. Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M, Innamorati M, Gonda X, Serafini G, Erbuto D, Ricci F, Fountoulakis KN, Lester D, Vazquez G, Rihmer Z, Amore M, Girardi P. Pharmacotherapy in bipolar disorders during hospitalization and at discharge predicts clinical and psychosocial functioning at follow-up. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2014;29:578–588. doi: 10.1002/hup.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Grossman JA, Buchsbaum Y, Banegas M, Freeman L, Gibbons R. Preliminary studies of the reliability and validity of the children’s depression rating scale. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1984;23:191–197. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett R, Kemp J, Wilson P, Minnis H, Bryce G, Gillberg C. Quick, simple measures of family relationships for use in clinical practice and research. A systematic review. Fam Pract. 2011;28:172–187. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinares M, Bonnin CM, Hidalgo-Mazzei D, Colom F, Sole B, Jimenez E, Torrent C, Comes M, Martinez-Aran A, Sanchez-Moreno J, Vieta E. Family functioning in bipolar disorder: Characteristics, congruity between patients and relatives, and clinical correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2016a;245:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinares M, Bonnin CM, Hidalgo-Mazzei D, Sanchez-Moreno J, Colom F, Vieta E. The role of family interventions in bipolar disorder: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016b;43:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel LS, West AE, Harral EM, Patel NB, Pavuluri MN. Parent-child interactions in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64:422–437. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S. A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RS, Hoeppner B, Yen S, Stout RL, Weinstock LM, Hower HM, Birmaher B, Goldstein TR, Goldstein BI, Hunt JI, Strober M, Axelson DA, Gill MK, Keller MB. Longitudinal associations between interpersonal relationship functioning and mood episode severity in youth with bipolar disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203:194–204. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon DA, Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Kelley J, Miller IW. Preventing recurrence of bipolar I mood episodes and hospitalizations: family psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy versus pharmacotherapy alone. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:798–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staccini L, Tomba E, Grandi S, Keitner GI. The evaluation of family functioning by the family assessment device: a systematic review of studies in adult clinical populations. Fam Process. 2015;54:94–115. doi: 10.1111/famp.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan AE, Judd CM, Axelson DA, Miklowitz DJ. Family functioning and the course of adolescent bipolar disorder. Behav Ther. 2012;43:837–847. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovic G, Starcevic V, Latas M, Lestarevic M, Ille T, Bukumiric Z, Marinkovic J. Reliability of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: a meta-analysis over a period of 49 years. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Meter AR, Moreira AL, Youngstrom EA. Meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1250–1256. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wegbreit E, Cushman GK, Weissman AB, Bojanek E, Kim KL, Leibenluft E, Dickstein DP. Reversal-learning deficits in childhood-onset bipolar disorder across the transition from childhood to young adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegbreit E, Weissman AB, Cushman GK, Puzia ME, Kim KL, Leibenluft E, Dickstein DP. Facial emotion recognition in childhood-onset bipolar I disorder: an evaluation of developmental differences between youths and adults. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17:471–485. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SM, Henry DB, Katz AC, Peters AT, West AE. Treatment moderators of child- and family-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock LM, Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Solomon DA, Miller IW. Family functioning and mood disorders: a comparison between patients with major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:1192–1202. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AE, Weinstein SM, Peters AT, Katz AC, Henry DB, Cruz RA, Pavuluri MN. Child- and family-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:1168–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.08.013. 1178.e1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan LJ, Hammen C, Cohen AN, Daley SE, Henry RM. Expressed emotion versus relationship quality variables in the prediction of recurrence in bipolar patients. J Affect Disord. 2004;83:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA, Youngstrom JK, Freeman AJ, De Los Reyes A, Feeny NC, Findling RL. Informants are not all equal: predictors and correlates of clinician judgments about caregiver and youth credibility. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21:407–415. doi: 10.1089/cap.2011.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Young D, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K. Severity classification on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.