Abstract

Surface display of biomolecules on the live cells offers new opportunities to treat human diseases and perform basic studies. Existing methods are primarily focused on unimolecular functionalization, i.e., the display of single biomolecules on each spot of the cell surface. Here we show that the surface of live cells can be functionalized to display polyvalent biomolecular structures through two-step reactions under physiological conditions. The polyvalent functionalization enables the cell surface to recognize the microenvironment one order of magnitude more effectively than unimolecular functionalization. Thus, polyvalent display of biomolecules on the live cells holds great potential for various biological and biomedical applications.

Keywords: polyvalent, cell engineering, DNA self-assembly

Graphical abstract

Polyvalent display: Biomolecules on the live cells play essential roles in determining how cells recognize the environment. Here we show that the surface of live cells can be functionalized to display polyvalent biomolecular structures for enhanced molecular recognition.

The cell surface displays various biomolecules. Their ability in recognizing the environment is important for the functions of the cells. Numerous methods have been studied to functionalize the surface of live cells with exogenous biomolecules for new functionalities of molecular recognition. The functionalized cells have been widely studied for applications such as immunotherapy, tissue engineering and stem cell homing.[1–9] These prominent methods are historically developed for unimolecular functionalization, i.e., the display of single biomolecules on each spot of the cell surface. As the objective of cell surface engineering is to acquire a new or enhanced ability of biomolecular recognition on the cells and polyvalent interactions are superior to monovalent interactions,[10] we explored a new method for polyvalent surface display of biomolecules on the live cells (i.e., polyvalent engineering) and further examined the functionalized cell surface in microenvironmental recognition and the formation of micro-scale tissue constructs.

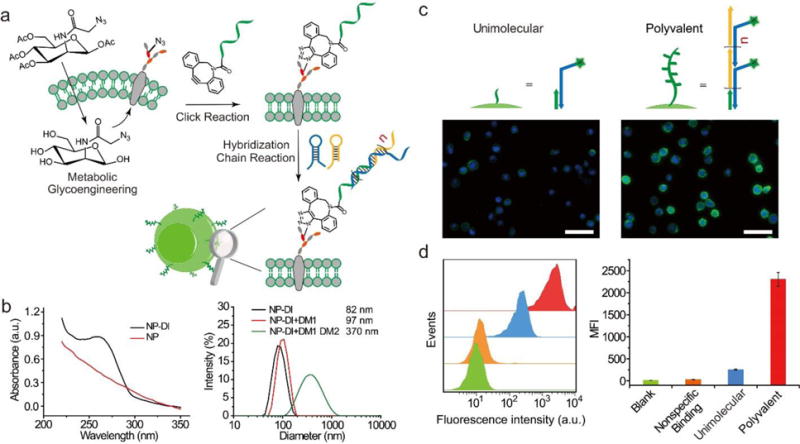

The cells experienced two-step surface treatment under physiological conditions (Figure 1a). The first surface treatment was to display a DNA initiator (DI) on the cells. The cells were fed with N-azidoacetylmannosamine-tetraacylated (Ac4ManNAz). After Ac4ManNAz is metabolized in the cytoplasm, its metabolite (i.e., N-α-azidoacetyl sialic acid) can be displayed on the cell surface as a moiety of membrane glycoproteins.[6] As the cell surface displays the azide groups, a molecule bearing dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) would react with the membrane glycoproteins via copper-free click chemistry.[11,12] The results (Figure S1) showed that the surface of the Ac4ManNAz-fed cells could display DI after treated with DI-DBCO. While we applied Ac4ManNAz for DI display, it is possible to use other methods to realize the same purpose. For instance, SNAP-tag allows for modification of surface proteins with functional groups that can be used to conjugate with DI.[13] Future work can be carried out to compare the advanages of these methods in DI display.

Figure 1.

Polyvalent engineering for surface display of branched DNA polymers. a) Schematic illustration of in situ formation of polyvalent DNA polymers on the cell surface. b) Characterization of DI-functionalized nanoparticles (NP) with UV-vis absorption spectra (left). Analysis of DNA polymerization on the particle surface using dynamic light scattering (right). c) Fluorescence images of the cells after unimolecular (left) or polyvalent (right) functionalization. Scale bars, 50 μm. d) Flow cytometry analysis of the engineered cells. Data were presented as mean±s.d.

Surface display of biomolecules on the live cells hold great potential for various applications;[14–19] however, the realization of this potential has a necessary prerequisite, i.e., maintenance of high cell viability. Thus, we examined the effect of DI-DBCO treatment on the cell viability. The results showed that the treatment of the cells with a high concentration of DI-DBCO decreased the cell viability (Figure S2), demonstrating that it is necessary to use a low concentration of DI to maintain high cell viability and minimize cell disturbance. We chose to use 45 μM of DI-DBCO in the following studies unless otherwise noted.

In the second surface treatment, the DI-displaying cells were reacted with two DNA hairpin monomers (DMs) to achieve polyvalent surface engineering (Figure 1a). The Pierce Group and others have shown that rationally designed DMs can polymerize in the presence of DI via hybridization chain reaction.[20–23] In this work, DMs were purposely designed to bear an unreacted side domain; thus, the formed DNA polymers would display repeating branches to achieve polyvalence for molecular recognition (Figure S3). The image of gel electrophoresis showed that DNA polymerization happened in the presence of DI (Figure S4a). Moreover, when the DI-functionalized particles were incubated with the solution of DMs, the apparent size of the particles significantly increased and reached 370 nm in diameter from the initially 82 nm in three hours (Figure 1b and Figure S4b). It demonstrates that polyvalent DNA polymers can also be synthesized on the DI-functionalized surface.

We then applied these two reactions including click reaction and DI-initiated DNA polymerization to functionalize the surface of live CCRF-CEM cells. We systematically designed numerous controls to validate the proposed concept and characterized the cells. The cells that were not treated with Ac4ManNAz exhibited little fluorescence after treated with DI-DBCO and/or DMs (1 μM) (Figure S5). In contrast, the cells fed with Ac4ManNAz exhibited very strong fluorescence after sequentially treated with DI-DBCO and DMs (Figure S5). Notably, these cells exhibited stronger fluorescence than those treated with DM1 alone (Figure 1c). Consistent with the microscopic observation, the flow cytometry data showed that the fluorescence intensity of the cells treated with the DMs solution was approximately one order of magnitude as high as that of the cells treated with DM1 alone (Figure 1d). Moreover, the fluorescence intensity of the cells increased with the reaction time (Figure S6) and the concentration of DI-DBCO (Figure S7), suggesting that the display of DI and the formation of the supramolecular DNA polymers can be controlled by the DI concentration and the reaction time. Taken together, these results demonstrate that supramolecular DNA polymers can form from DI on the surface of live cells.

Notably, the DNA polymers have multiple repeating branches and each branch is an element of molecular recognition. Thus, the presence of multiple branches in each DNA polymer leads to the polyvalent functionalization of the cell surface. We thereafter examined the ability of the engineered cells in recognizing the environment at both the nano-scale and micro-scale levels. To illustrate the ability of recognizing the nano-scale materials, we incubated the engineered cells in the solution of nanoparticles (~10 nm). The end of the DNA branch was labeled with biotin and the nanoparticles was tethered with streptavidin. The images show that very few nanoparticles were observed on the cell surface that was only functionalized with DM1. In contrast, a large number of nanoparticles extended from the cell surface to the surrounding in the polyvalence group (Figure 2a), indicating that the ability of nanoparticle recognition by the engineered cell surface with polyvalent DNA polymers could be tremendously enhanced by orders of magnitude. This difference may come from two reasons. One is the increase of the valence on the cell surface as polyvalent interactions are superior to monovalent interactions.[24–26] The other may be due to the decrease of steric hindrance as polyvalent DNA polymers were >100 nm in length with the ability of protruding from the cell surface (Figure 1b). The native cell surface has a nanoscale glycocalyx layer[27] that may limit the access of nanoparticles from the microenvironment to biomolecules in the vicinity of the glycocalyx layer. Taken together, these data suggest that the ability of the cells in molecular recognition could be tremendously strengthened through polyvalent display.

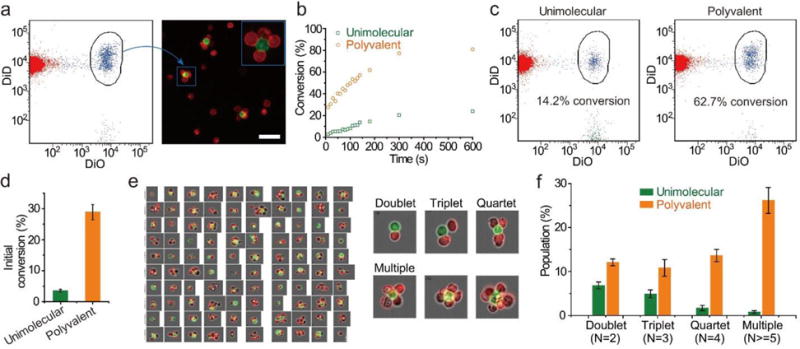

Figure 2.

Comparison between unimolecular and polyvalent display in promotion of cell-microenvironment interactions. a) Examination of the cell surface in nanomaterials recognition with STEM imaging. Bright spots: ~10 nm of quantum dots. b) Recognition of cell. Representative images of the constructs formed with the engineered CCRF-CEM cells. The engineered cells were separated into two groups and labeled with either DiO (green) or DiD (red), respectively. Scale bars, 100 μm. Schematic illustration was used for clear legibility. c) The difference between polyvalent and unimolecular functionalization in promoting cell-cell recognition. For measurement and calculation, the cell constructs were assumed to be spheres. Data were presented as mean±s.d.

Experiments were further performed to examine the ability of the engineered cells in recognizing the environment at the micro-scale level. To this end, two groups of CCRF-CEM cells were functionalized with two different DNA polymers that had the same backbone but displayed complementary branches (Table S1). As the two branches were complementary, the two DNA polymers would form polyvalent hybridization to direct cell assembly (Figure 2b). Notably, to avoid any bias in the experimental design, we used the CCRF-CEM cell line as the model because this cell is non-adherent. Thus, the primary driving force for cell assembly would be attributed to polyvalent recognition other than the natural state of cell adhesion. For clear legibility, the two cell groups were labeled with DiO (green) and DiD (red), respectively. Indeed the two cells formed micro-scale constructs and the size of the constructs increased with the cell density (Figure S8).

The difference between polyvalent engineering and unimolecular engineering (control) in promoting the formation of the constructs was compared. For each comparison, the cell density was the same in the two studied groups. The calculated size of the constructs in the polyvalence group was over one order of magnitude larger than that in the control group (Figure 2c and Figure S9). It held true in all three DI-DBCO concentrations. It suggests that the average number of cells in each construct in the polyvalence group was at least ten times more than that in the control group. These results demonstrate that polyvalent engineering is more effective in inducing the formation of the constructs than unimolecular engineering.

We also examined the kinetics of cell assembly using flow cytometry to track the formation of flower-shaped constructs (Figure 3a). The conversion of the green cells into the constructs in the polyvalence group was faster than that in the control group (Figure 3b and 3c). This difference in conversion was more significant at the right beginning of mixing the cells (Figure 3d). 2.5% of the green cells in the control group versus 28.9% in the polyvalence group were converted into the constructs. We further compared the individual populations of doublets, triplets, quartets and the constructs with ≥ 5 cells using imaging flow cytometry (Figure 3e and Figure S10). The percentage of green cells that formed constructs with ≥ 5 cells in the control group was 0.8%; in contrast, that in the polyvalence group was 26.1 %, which is over one order of magnitude higher than that of the control (Figure 3f). These results confirmed that polyvalent engineering was superior to unimolecular engineering in promoting cell-cell recognition.

Figure 3.

Kinetic analysis of cell assembly. a) Flow cytometry analysis of the flower-shaped constructs. DiO and DiD stained cells were mixed at a ratio of 1:25 and analyzed by flow cytometry. The gated blue population represented the flower-shaped constructs. b) Kinetic profiles of cell assembly for the formation of the constructs. c) Representative flow cytometry histograms showing the conversion of DiO-labeled cells into the constructs. The time point for analysis was set at 180 s. d) Comparison of the initial conversion rates (within the first 10 sec) after the mixing of the two cell populations. e) High-speed microscopic images of cell constructs during flow cytometry analysis (left). Representative images of different constructs were given (right). f) Analysis of the percentages of the constructs. Data were presented as mean±s.d.

After demonstrating the enhanced ability of the cells with polyvalent functionalization in recognizing environment, we further investigate the potential of this method in biological and biomedical applications. As a case study, we replaced the cancer cell line CCRF-CEM with two primary human cells to develop micro-scale tissue constructs. Both fluorescence images and flow cytometry histograms show that the supramolecular DNA polymers could be displayed on the primary human cells (Figure 4a and 4b). As these two human cells were engineered to display complementary polyvalent DNA polymers, respectively, these two cells formed the hMSC-NHAC constructs once mixed. Importantly, the constructs increased in size from the beginning 55 μm to 320 μm in 20 days during the culture (Figure 4c and Figure S11). It demonstrated that the functionalized cells maintained the viability and capability to grow. Development of micro-scale tissue constructs holds great potential for biomedical applications such as tissue engineering and drug screening.[28–31] For instance, the co-culture of stem cells and chondrocytes has been studied to promote chondrogenesis.[32] Thus, we stained type II collagen and aggrecan, two major markers of chondrogenesis. The hMSC-NHAC constructs expressed more type II collagen and aggrecan than the constructs with either hMSC or NHAC alone (Figure 4d). These data demonstrate that it is promising to engineer live human cells with polyvalent functionalization and to make micro-scale tissue constructs.

Figure 4.

Generation and growth of hMSC-NHAC constructs. a) Fluorescence images of the cells engineered with the unimolecular or polyvalent functionalization methods. Blue: DAPI. Green: Calcein-AM. Red: DNA or polyvalent DNA polymer. Scale bars, 100 μm. b) Flow cytometry analyses of the engineered cells. c) Size analysis of the hMSC-NHAC constructs during the culture. hMSC expressed RFP for clear observation. Representative images acquired at different time points are shown to demonstrate the growth of the constructs. Scale bars, 100 μm. d) Immunofluorescence staining of the constructs for analyzing the expression of type II collagen and aggrecan. Scale bars, 50 μm.

When modification is applied to the cell surface, it is important to ensure that the original composition and functionality of the cell will not be significantly changed or disturbed. Thus, it would be ideal to tether exogenous biomolecules with the least amount directly on the cell surface and meanwhile to realize the desired functions of molecular recognition. The method of polyvalent functionalization meets the demand. It only needs a small amount of DNA on the cell surface as each DNA initiator will grow into a supramolecular DNA polymers with multiple branches. Nucleic acids can be conjugated to a diverse array of molecules, nano-scale materials, micro-scale materials and many other substrates.[33,34] Nucleic acid hybridization has also been demonstrated to be a powerful tool for the development of new structures and materials.[35–37] Based on those previous studies and the current work, we envision that the engineered cell surface would recognize a variety of living or non-living substances. Thus, this method for the polyvalent display of biomolecules on the live cells holds potential for broad biological and biomedical applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported here was partially supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (Grant DMR-1322332) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (Grant R01HL122311). We thank the Husk Institute Microscopy Facility (University Park, PA) for technical support.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- 1.Sackstein R, Merzaban JS, Cain DW, Dagia NM, Spencer JA, Lin CP, Wohlgemuth R. Nat Med. 2008;14:181–187. doi: 10.1038/nm1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fesnak AD, June CH, Levine BL. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:566–581. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gartner ZJ, Bertozzi CR. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:4606–4610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900717106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu H, Kwong B, Irvine DJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:7052–7055. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Todhunter ME, Jee NY, Hughes AJ, Coyle MC, Cerchiari A, Farlow J, Garbe JC, LaBarge MA, Desai TA, Gartner ZJ. Nat Methods. 2015;12:975–981. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prescher JA, Dube DH, Bertozzi CR. Nature. 2004;430:873–877. doi: 10.1038/nature02791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross G, Waks T, Eshhar Z. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86:10024–10028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.10024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Q, Cheng H, Peng H, Zhou H, Li PY, Langer R. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;91:125–140. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeong JH, Schmidt JJ, Kohman RE, Zill AT, DeVolder RJ, Smith CE, Lai MH, Shkumatov A, Jensen TW, Schook LG, Zimmerman SC, Kong H. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:8770–8773. doi: 10.1021/ja400636d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mammen M, Choi SK, Whitesides GM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:2754–2794. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2754::AID-ANIE2754>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jewett JC, Bertozzi CR. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1272–1279. doi: 10.1039/b901970g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Wang R, Cai K, He H, Liu Y, Yen J, Wang Z, Xu M, Sun Y, Zhou X, Yin Q, Tang L, Dobrucki IT, Dobrucki LW, Chaney EJ, Boppart SA, Fan TM, Lezmi S, Chen X, Yin L, Cheng J. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:415–424. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu GJ, Friedman M, Jost C, Johnsson K, Kamali-Moghaddam M, Plückthun A, Landegren U, Söderberg O. N Biotechnol. 2013;30:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarkar D, Spencer JA, Phillips JA, Zhao W, Schafer S, Spelke DP, Mortensen LJ, Ruiz JP, Vemula PK, Sridharan R, Kumar S, Karnik R, Lin CP, Karp JM. Blood. 2011;118:e184–e191. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vermesh U, Vermesh O, Wang J, Kwong GA, Ma C, Hwang K, Heath JR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:7378–7380. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tokunaga T, Namiki S, Yamada K, Imaishi T, Nonaka H, Hirose K, Sando S. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:9561–9564. doi: 10.1021/ja302551p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akbari E, Mollica MY, Lucas CR, Bushman SM, Patton RA, Shahhosseini M, Song JW, Castro CE. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1703632. doi: 10.1002/adma.201703632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabrielse K, Gangar A, Kumar N, Lee JC, Fegan A, Shen JJ, Li Q, Vallera D, Wagner CR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:5112–5116. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang B, Song J, Yuan H, Nie C, Lv F, Liu L, Wang S. Adv Mater. 2014;26:2371–2375. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dirks RM, Pierce NA. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:15275–15278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407024101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen N, Shi X, Wang Y. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:6657–6661. doi: 10.1002/anie.201601008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xuan F, Hsing IM. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9810–9813. doi: 10.1021/ja502904s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu G, Zhang S, Song E, Zheng J, Hu R, Fang X, Tan W. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:5490–5496. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu X, Liu Z, Janzen J, Chafeeva I, Horte S, Chen W, Kainthan RK, Kizhakkedathu JN, Brooks DE. Nat Mater. 2012;11:468–476. doi: 10.1038/nmat3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mourez M, Kane RS, Mogridge J, Metallo S, Deschatelets P, Sellman BR, Whitesides GM, Collier RJ. Nat Biotech. 2001;19:958–961. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer W, Perkins S, Theiler J, Bhattacharya T, Yusim K, Funkhouser R, Kuiken C, Haynes B, Letvin NL, Walker BD, Hahn BH, Korber BT. Nat Med. 2007;13:100–106. doi: 10.1038/nm1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reitsma S, Slaaf DW, Vink H, van Zandvoort MAMJ, oude Egbrink MGA. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454:345–359. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee GY, Kenny PA, Lee EH, Bissell MJ. Nat Methods. 2007;4:359–365. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huh D, Hamilton GA, Ingber DE. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:745–754. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koo H, Choi M, Kim E, Hahn SK, Weissleder R, Yun SH. Small. 2015;11:6458–6466. doi: 10.1002/smll.201502972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pulsipher A, Dutta D, Luo W, Yousaf MN. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:9487–9492. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bian L, Zhai DY, Mauck RL, Burdick JA. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;17:1137–1145. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roh YH, Ruiz RCH, Peng S, Lee JB, Luo D. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:5730–5744. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15162b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin C, Jungmann R, Leifer AM, Li C, Levner D, Church GM, Shih WM, Yin P. Nat Chem. 2012;4:832–839. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones MR, Seeman NC, Mirkin CA. Science. 2015;347:1260901. doi: 10.1126/science.1260901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winfree E, Liu F, Wenzler LA, Seeman NC. Nature. 1998;394:539–544. doi: 10.1038/28998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun W, Boulais E, Hakobyan Y, Wang WL, Guan A, Bathe M, Yin P. Science. 2014;346:1258361. doi: 10.1126/science.1258361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.