Abstract

Background

Failure of chemoradiotherapy (CRT) for anal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) results in persistent or recurrent anal SCC. Treatment with salvage abdominoperineal resection (APR) can potentially achieve cure. The aims of this study are to analyze oncological and surgical outcomes of our 30-year experience with salvage APR for anal SCC after failed CRT and identify prognostic factors for overall survival (OS).

Methods

All consecutive patients who underwent salvage APR between 1990 and 2016 for histologically confirmed persistent or recurrent anal SCC after failed CRT were retrospectively analyzed.

Results

Forty-seven patients underwent salvage APR for either persistent (n = 24) or recurrent SCC (n = 23). Median OS was 47 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 10.0–84.0 months] and 5-year survival was 41.6%, which did not differ significantly between persistent or recurrent disease (p = 0.551). Increased pathological tumor size (p < 0.001) and lymph node involvement (p = 0.014) were associated with impaired hazard for OS on multivariable analysis, and irradical resection only (p = 0.001) on univariable analysis. Twenty-one patients developed local recurrence after salvage APR, of whom 8 underwent repeat salvage surgery and 13 received palliative treatment. Median OS was 9 months (95% CI 7.2–10.8 months) after repeat salvage surgery and 4 months (95% CI 2.8–5.1 months) following palliative treatment (p = 0.055).

Conclusions

Salvage APR for anal SCC after failed CRT resulted in adequate survival, with 5-year survival of 41.6%. Negative prognostic factors for survival were increased tumor size, lymph node involvement, and irradical resection. Patients with recurrent anal SCC after salvage APR had poor prognosis, irrespective of performance of repeat salvage surgery, which never resulted in cure.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the anal canal is a relatively rare malignancy, but its incidence has increased over the last few years.1 Currently, chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is standard of care for anal cancer, resulting in superior local control compared with radiotherapy alone with 5-year survival rates of 60–80%.2–8 CRT leads to preservation of the anal sphincter by avoiding surgery. Unfortunately, CRT fails in 20–30% of patients, resulting in persistent (10–15%) or local recurrent disease (10–15%).2–7,9

Salvage abdominoperineal resection (APR) is often the only option for patients with persistent or recurrent anal SCC to achieve durable local control and survival. Several institutes have reported case series on this topic. However, due to heterogeneity in treatment protocols, results on patient outcomes vary widely.10–20 Our institute has a well-established protocol for treatment of anal SCC, which has changed little in the last three decades. The aims of the present study are to analyze the results of a 30-year experience with salvage APR for recurrent and persistent anal SCC after failed CRT in a large single-center cohort and to identify prognostic factors for overall survival. In addition, outcomes of patients treated for local recurrence developed after primary salvage APR for persistent or recurrent SCC were also analyzed. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, results of repeat surgery for treatment of local recurrence after salvage APR have never been previously studied.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data of all consecutive patients who underwent salvage APR with curative intent for histologically confirmed persistent or recurrent anal SCC between 1990 and 2016 at the Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, a tertiary referral center in The Netherlands, were retrospectively analyzed. Patient demographics, perioperative variables, tumor characteristics, neoadjuvant therapy, short- and long-term outcomes, and postoperative mortality and morbidity were collected from medical records, the municipality register, and general practitioners. All patients were followed up by our institute; last update of follow-up was 22 January 2018. The present study was approved by the Erasmus MC local medical ethics committee (registration number MEC-2017-448).

Primary Treatment

All primary malignancies were initially treated with radiotherapy, and the majority (78.7%) also received concomitant chemotherapy. Radiotherapy was administered with median dose of 60 Gy [interquartile range (IQR) 60–60 Gy], and chemotherapy was administered in the first four days of the first week [5-fluorouracil (1000 mg/m2) and mitomycin C (10 mg/m2)]. Patients with histologically proven anal SCC within 6 months after the last day of radiotherapy, or patients with incomplete response, were classified as having persistent disease. Initial complete responders to (chemo)radiotherapy, who were diagnosed with biopsy-proven recurrent anal SCC, after 6 months or more since the last day of radiotherapy, were classified as having recurrent disease.

Staging

Tumor stage was assessed by physical examination and radiologic imaging according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor–node–metastasis (TNM) staging system (7th edition) for cancer of the anal canal. Nodal stage was assessed by pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and suspicious inguinal lymph nodes were biopsied. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest and abdomen were used to confirm absence of metastatic disease prior to surgery.

Surgery

All patients deemed eligible for complete, curative resection underwent salvage APR. Multivisceral resection was performed if necessary. If possible, omentoplasty was performed to fill the pelvis. Primary closure of the perineal defect was routinely performed up to 1999, and if this was not feasible, the open wound was packed for healing by secondary intention. From 2000 onwards, the perineal defect was reconstructed with either a vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous (VRAM) or gracilis muscle flap.21,22 Inguinal lymph node dissection was performed in case of biopsy-proven positive lymph nodes. Postoperative complications were graded according to the Dindo–Clavien classification.23 Local recurrence after salvage APR was defined as any local recurrence after salvage APR, regardless of whether the indication for salvage APR was for persistent or recurrent anal SCC.

Statistics

Survival analysis was performed by Kaplan–Meier method, and comparisons were made using log-rank tests. Survival was calculated from day of APR until data of death or last follow-up. Survival rates for recurrence after salvage APR were calculated from date of diagnosis of recurrent anal SCC until death or last follow-up. Cox proportional-hazard models were constructed to identify prognostic factors in univariable and multivariable analysis. Mann–Whitney U and chi-squared test were performed as appropriate. Covariables with a trend towards significance (p < 0.100) were selected for multivariable analysis, with a maximum of three considering the number of events. Two-sided p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0.0 for Windows (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA).

RESULTS

Forty-seven consecutive patients underwent salvage APR for anal SCC between 1990 and 2016. Patient characteristics are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics before and after abdominoperineal resection (N = 47)

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 27 | 57.4 |

| Female | 20 | 42.6 |

| Age | ||

| At time of diagnosis primary | 53 (46–66)* | |

| At time of operation | 56 (48–66)* | |

| Clinical tumor stage | ||

| T1 | 8 17.0 | |

| T2 | 20 | 42.6 |

| T3 | 13 | 27.7 |

| T4 | 6 | 12.8 |

| Clinical nodal stage | ||

| N0/Nx | 40 | 85.1 |

| N1 | 5 | 10.6 |

| N2 | 2 | 4.3 |

| Clinical Metastasis stage | ||

| M0 | 45 | 95.7 |

| M+ | 2 | 4.3 |

| Histology | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 47 | 100 |

| Pretreatment | ||

| Radiotherapy | 47 | 100 |

| Mean dose Gy | 60 (60–60)* | |

| Concomitant chemotherapy | ||

| 5-FU Mitomycin C | 36 | 76.6 |

| 5-FU only | 1 | 2.1 |

| No chemotherapy | 10 | 21.3 |

| Indication for surgery | ||

| Persistent disease | 24 | 48.9 |

| Recurrent disease | 23 | 51.1 |

| Time interval radiotherapy and surgery (in months) | ||

| Persistent disease | 5 (4–7)* | |

| Recurrent disease | 15.0 (9.5–37.5)* | |

| Surgical procedure | ||

| APR | 35 | 74.5 |

| APR and posterior vaginal wall | 4 | 8.5 |

| Posterior exenteration | 4 | 8.5 |

| Total pelvic exenteration | 2 | 4.3 |

| Posterior exenteration and vulvectomie | 2 | 44.3 |

| Additional procedures | ||

| Partial sacrectomy | 2 | 4.3 |

| Synchronous ILND | 2 | 4.3 |

| Omentoplasty | 33 | 70.2 |

| IORT | 2 | 4.3 |

| Wound closure and/or reconstruction | ||

| Primary closure | 10 | 21.3 |

| Wound left open | 1 | 2.1 |

| VRAM-flap | 31 | 66.0 |

| Gracilis flap | 3 | 6.4 |

| Pudendus flap | 1 | 2.1 |

| Gluteal flap | 1 | 2.1 |

| Operating time | ||

| Minutes | 378.6 ± 129.9** | |

| Pathological tumor size | ||

| Maximum diameter (millimeter) | 30.0 (20.0–48.3)* | |

| Pathological nodal stage | ||

| N0/Nx | 41 | 87.2 |

| N1 | 2 | 4.3 |

| N2 | 4 | 8.5 |

| Pathological metastases stage | ||

| M0/Mx | 43 | 91.5 |

| M1 | 4 | 8.5 |

| Vasoinvasion | ||

| Yes | 11 | 23.3 |

| No | 18 | 38.3 |

| Unknown | 18 | 38.3 |

| Perineural growth | ||

| Yes | 14 | 29.8 |

| No | 15 | 31.3 |

| Unknown | 18 | 38.3 |

| Pathological resection margins | ||

| R0 | 38 | 80.9 |

| R1 | 8 | 17.0 |

| R2 | 1 | 2.1 |

*Median and interquartile range, **Mean and standard deviation

APR abdominoperineal resection, IORT intra-operative radiotherapy, VRAM vertical rectus abdominus muscle, ILND Inguinal lymph node dissection, 5-FU 5-fluorouracil

Surgical Results

Indications for surgery were either persistent (n = 24; 48.9%) or recurrent disease (n = 23; 51.1%). Median time between the last day of (chemo)radiotherapy and date of surgery was 5 months (IQR 4–7 months) for patients with persistent disease and 15 months (IQR 9.5–37.5 months) for patients with recurrent disease. APR without additional resections was performed in 35 patients, APR with posterior vaginal wall resection in 4 patients, posterior exenteration in 6 patients (including vulvectomy in 2 patients), and total pelvic exenteration in 2 patients. Other additional procedures were partial sacrectomy (n = 2), synchronous inguinal lymph node dissection (n = 2), and intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT, n = 2). Omentoplasty was performed in 33 patients. One patient had two lesions in the liver suspicious for metastases, which were histopathologically confirmed by frozen section. Salvage APR was performed, but the liver metastases were not resected. Until 1999, primary perineal closure was performed in seven patients, one open wound was packed for secondary healing, and one gluteal transposition flap was performed for reconstruction. In 38 patients treated from 2000 onwards, primary perineal closure was performed three times, while a locoregional flap for perineal closure was used 35 times [VRAM flap (n = 31), gracilis muscle flap (n = 3), and bilateral pudendal flap (n = 1)]. Surgical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Radical resection (R0) was achieved in 38 patients (80.9%), microscopically irradical resection (R1) in 8 patients (17.0%), and macroscopically irradical resection (R2) in 1 patient (2.1%). One patient had liver metastases, and three patients had inguinal lymph node metastases. Tumor characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Mortality and Morbidity

None of the patients died within 30 days of surgery. Within 2 months, there was one case of euthanasia due to unbearable suffering from severe wound infection and no perspective of cure considering confirmed liver metastases. The majority of patients (n = 33; 70.3%) experienced no or minor complications (Dindo–Clavien ≤ 2), and 14 patients (29.7%) developed major complications (Dindo–Clavien ≥ 3). Mortality and morbidity are displayed in Table 2. Six out of 10 patients with primary closure of the perineal defect and 9 out of 36 patients with muscle flap reconstruction (MFR) experienced perineal wound complications. Nine patients required surgery for perineal wound complications. The latter were treated with debridement with (n = 5) or without vacuum-assisted closure therapy (n = 2) and muscle flap necrosectomy followed by repeat reconstruction (n = 2). Median time between last day of radiotherapy and surgery did not significantly influence perineal wound complications (p = 0.909). The proportion of patients with perineal wound complications was lower in patients treated with MFR (25%; 9/36) compared with patients treated without MFR (54.5%; 6/11), however this was not significant (p = 0.066).

Table 2.

Mortality, morbidity, and perineal wound complications

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality | ||

| < 30 days after surgery | 0 | 0 |

| During hospital admission | 1 | 2.1 |

| Dindo-Clavien | ||

| None | 17 | 36.2 |

| Dindo 1 | 6 | 12.8 |

| Dindo 2 | 10 | 21.3 |

| Dindo 3A | 1 | 2.1 |

| Dindo 3B | 10 | 21.3 |

| Dindo 4 | 3 | 6.4 |

| Dindo 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Major complications | ||

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 | 2.1 |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 2 | 4 |

| Gastric ulcer bleeding | 1 | 2.1 |

| Major complications requiring surgery | ||

| Stoma necrosis | 1 | 2.1 |

| Abdominal wound necrosis | 1 | 2.1 |

| Fascia dehiscence | 1 | 2.1 |

| Perineal wound complications | MFR (N = 36) | No MFR (N = 11) |

|---|---|---|

| Additional muscle flap reconstruction | 1 | 1 |

| Vacuum assisted therapy | 3 | 2 |

| Wound complication treated conservative | 4 | 3 |

| Wound complication requiring debridement | 2 | 0 |

| Perineal hernia | 1 | 1 |

MFR muscle flap reconstruction

Survival

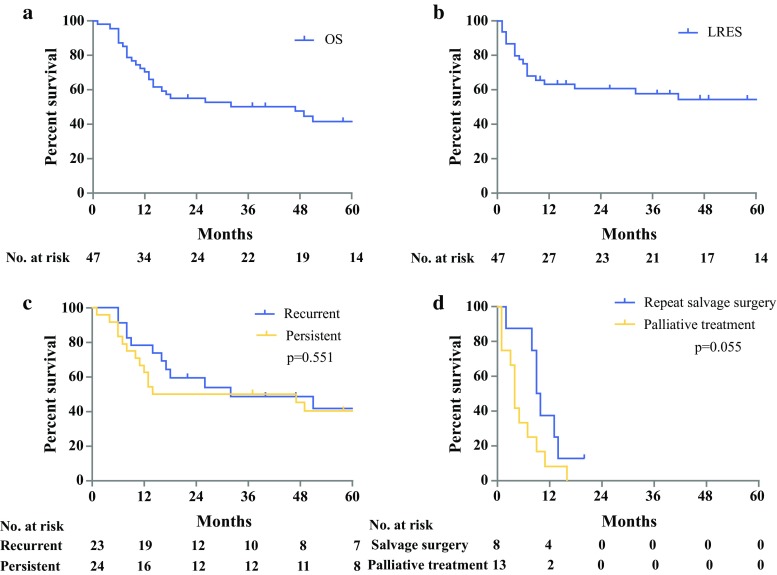

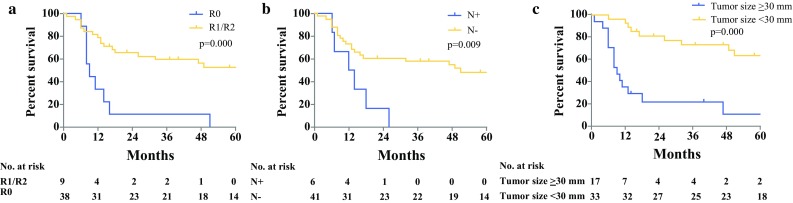

Median follow-up time was 80 months (95% CI 68.6–91.4 months). At last follow-up, 19 patients (40.4%) were alive. Median overall survival (OS) was 47 months (95% CI 10.0–84.0 months), and the estimated 5-year survival rate was 41.6%. Survival curves did not differ significantly between patients with persistent versus recurrent disease (5-year survival rate 40.4 vs. 41.7%, respectively; p = 0.551). Survival curves are shown in Fig. 1. On both univariable and multivariable analysis, increased pathological tumor size (p < 0.001) and positive lymph nodes (p = 0.014) were significantly associated with worse OS. Irradical resection was only significantly associated on univariable analysis (p = 0.001) but not on multivariable analysis (p = 0.087). Analyses are presented in Table 3, and the influence on survival in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

a Overall survival (OS). b Local recurrence-free survival (LRFS). c OS for persistent versus recurrent disease. d OS for local recurrence after salvage APR; repeat salvage surgery versus palliative treatment

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable survival analysis for overall survival of squamous cell carcinoma

| Univariable | P value | Multivariable | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio [95% CI] | Hazard ratio [95% CI] | |||

| Male versus female | 1.150 [0.536–2.466] | 0.720 | – | – |

| Age at time of operation | 1.021 [0.986–1.058] | 0.239 | – | – |

| CTxRTx versus RTx | 0.884 [0.332–2.351] | 0.805 | – | – |

| Recurrent disease versus persistent disease | 0.794 [0.794–1.709] | 0.556 | – | – |

| Multivisceral resection | 1.169 [0.524–2.608] | 0.704 | – | – |

| Irradical resection (R1/R2) | 4.056 [1.746–9.423] | 0.001 | 2.786 [0.862–9.005] | 0.087 |

| Node positive (N1/N2) | 3.228 [1.255–8.302] | 0.015 | 4.445 [1.356–14.563] | 0.014 |

| Metastasis positive (M1) | 2.603 [0.878–7.712] | 0.084 | – | – |

| Vasoinvasion | 2.081 [0.795–5.679] | 0.144 | – | – |

| Perineural growth | 2.702 [0.973–7.504] | 0.056 | – | – |

| Pathological tumor size (maximum diameter in mm) | 1.039 [1.023–1.055] | < 0.001 | 1.036 [1.018–1.054] | < 0.001 |

CTxRTx chemoradiotherapy, RTx radiotherapy

Fig. 2.

Overall survival curves (prognostic factors): a resection margin, b nodal stage, and c pathological tumor size (diameter in millimeters with median as cutoff value)

Recurrence after Salvage APR

The overall rate of disease recurrence after salvage APR was 55.3%. Twenty-one patients (44.7%) developed local recurrence after salvage APR, including 13 patients with simultaneous locoregional recurrence or distant metastases [inguinal lymph node (n = 7), liver (n = 2), adrenal gland (n = 1), retroperitoneal lymph nodes (n = 1), peritoneal carcinomatosis (n = 1), and cervical lymph node + liver metastasis (n = 1)]. Five patients developed distant metastases or locoregional recurrence only [inguinal lymph node (n = 2), retroperitoneal lymph nodes (n = 1), hilar lymph nodes (n = 1), liver metastases (n = 1)]. Median OS for patients with local recurrence and/or distant metastases after salvage APR was 12 months (95% CI 8.3–15.7 months). Median local-recurrence-free survival after salvage APR (LRFS) was not reached. The estimated 5-year LRFS after salvage APR was 51.1%. None of the patients developed local recurrence after 42 months from salvage APR. Three patients received postoperative chemotherapy for metastatic disease, and none of the patients received standard adjuvant chemotherapy.

Eight patients with local recurrence after salvage APR underwent repeat salvage surgery by extensive local excision, including additional inguinal lymph node dissection (n = 2), liver metastases resection (n = 1), and cervical lymph node dissection (n = 1).

Thirteen patients underwent palliative treatment for local recurrence after salvage APR, including fistula resection (n = 2), radiotherapy in combination with hyperthermia (n = 2), and chemotherapy for metastatic disease (n = 2), while seven patients received best supportive care only. Median OS for all patients with local recurrence after salvage APR, calculated from date of diagnosis of local recurrence, was 7 months (95% CI 1.0–13.0 months). The 1-year survival rate was 19.0%, and all patients died within 15 months except for one patient, who had undergone repeat salvage surgery and was still alive at last follow-up of 22 months.

There was no significant difference (p = 0.055) in survival of patients with local recurrence after salvage APR treated with repeat salvage surgery, with median OS of 9 months (95% CI 7.2–10.8 months), compared with patients with palliative treatment, with median OS of 4 months (95% CI 2.8–5.1 months).

DISCUSSION

The present study describes the results of salvage APR for SCC of the anal canal after failure of initial primary therapy in 47 patients. Overall estimated 5-year survival was 41.6%. Negative prognostic factors were increased pathological tumor size and lymph node involvement on multivariable analysis, and positive resection margin only on univariable analysis. Type of local failure did not affect survival. The overall local recurrence rate after salvage APR was 44.7%. None of the patients who developed local recurrence after salvage APR could be cured, and all had poor prognosis.

Although surgery has been replaced by CRT for primary treatment of SCC of the anal canal, salvage APR has remained the gold standard for patients with persistent disease or local recurrent disease after failed CRT. Due to the relative rarity of the procedure for this indication, most published series consist of only a small number of patients treated over a long period of time, and are therefore prone to a certain degree of bias. We present herein a rather homogeneous group of patients. All patients were treated with an adequate radiation dose of > 45 Gy, and all but eight patients received the standard protocol of 60 Gy. This in contrast to some other published series where the study population was treated with a wide range of radiation doses.9–11,16

The percentages of radical resection and 30-day postoperative mortality are comparable to previous studies.9,13,24–27 Outcome measures of complications after salvage APR varied widely in other studies, preventing adequate comparison. However, in the current study, surgical reinterventions were slightly more common (25.5%) than the range reported by others (12–20%).13,24–26 In this study, 31.9% of patients experienced perineal complications, while others reported perineal complications in 22–50% of patients, regardless of use of muscle flap reconstruction.9,13,16,25,27 We could not identify a group prone to perineal complications based on time between radiotherapy and surgery or use of muscle flap reconstruction, possibly due to small numbers.

The 5-year OS in this study of 41.6% lies within the range of 23–69% reported by other authors. Survival of patients with persistent disease did not differ significantly from that of patients with recurrent disease, which is also in agreement with results published previously,10,11,14,15,17,19,28 although some studies did report poorer survival rates in patients with persistent compared with recurrent disease.10,16 This could be explained by more aggressive behavior of tumor cells in persistent disease or fast regrowth. However, other studies reported significantly worse survival in patients with recurrent disease, which could not be explained clearly.29,30

We found that increased pathological tumor size, lymph node involvement, and positive resection margins adversely affected survival, which is in concordance with most other series (Appendix 1).9–11,13–15,17,24,25,28,30–32 Although not identified on multivariable analysis in the present study, positive resection margin seems to remain the most common factor negatively affecting survival. These findings emphasize the importance of achieving negative resection margins, which can sometimes only be achieved by aggressive multivisceral resection or multidisciplinary treatment.

Recently, Hallemeier et al.30 reported a multidisciplinary approach, including reirradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy and IORT, in a small group of patients with persistent or recurrent anal cancer. Only 21% developed recurrence within the reirradiated area. The 5-year OS was 23%, but they specifically treated patients with expected narrow or positive resection margins.30 In the present study, only two patients received IORT, and none received reirradiation prior to salvage surgery, because of the high-dose radiotherapy used as primary treatment. Wright et al.33 retrospectively analyzed 14 patients with locoregional recurrent anal SCC who underwent salvage surgery and IORT. Addition of IORT was not associated with locoregional control or survival benefit and did not compensate for positive surgical margins.33 Reirradiation and IORT could potentially decrease local recurrence rate, but this remains unclear.

Currently there is no role for standard adjuvant chemotherapy, however the combination of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is the gold standard in metastatic disease, with an overall response rate of 60%.34,35 Eng et al.36 showed a prolonged OS for multidisciplinary management with systemic chemotherapy and intervention compared with palliative chemotherapy only in patients with unresectable and metastatic anal SCC.36 In the present study, three patients received postoperative chemotherapy without additional intervention. Therefore, we could not clearly assess the effect on OS. Multidisciplinary treatment for unresectable and metastatic anal SCC can potentially lead to prolonged OS.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to present data on treatment of recurrent anal SCC after failed CRT for primary anal SCC and salvage APR for recurrent/persistent anal SCC. Alamri et al.27 and Correa et al.24 only reported survival for these patients. Some patients with local recurrence after salvage APR also had distant metastases or locoregional recurrence, and type of surgery was not protocolled as it is for the primary salvage APR. On the other hand, our results clearly show that recurrence after salvage APR has poor prognosis, regardless of the treatment. Palliative surgery may still be considered for some patients, especially those with pain. Cure, however, does not seem to be possible.

This study is limited by its retrospective nature and the small number of patients collected over a long time period. Patients with persistent or recurrent disease have different tumor biology, and mixing these cases could affect the outcomes of salvage APR. Advances in diagnostic imaging and treatment were made during the study period and likely contributed to heterogeneity in our study population and outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the present study show that salvage APR for patients with SCC of the anal canal after failed CRT provides adequate long-term survival and local control. Prognostic factors for survival were advanced tumor stage, lymph node involvement, and positive resection margins. Patients with recurrent anal SCC after salvage APR had poor prognosis irrespective of performance of repeat salvage surgery, which never resulted in cure.

Appendix 1: Overview of Current Literature

| Ref. | Year of publication | No. of patients | 5-Year OS (%) | Prognostic factors for OS after salvage APR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zelnick et al.20 | 1992 | 9 | 24 | Not identified or not mentioned |

| Ellenhorn et al.11 | 1993 | 38 | 44 | Nodal disease |

| Tumor fixed to lateral pelvic wall | ||||

| Involvement of perirectal fat | ||||

| Longo et al.6 | 1994 | 34 | 23–53 | Stage |

| Method of treatment | ||||

| Pocard et al.37 | 1998 | 21 | 33 | Not identified or not mentioned |

| Allal et al.29 | 1999 | 26 | 45 | Not identified or not mentioned |

| Smith et al.18 | 2001 | 22 | 33 | Not identified or not mentioned |

| Van der Wal et al.19 | 2001 | 17 | 47 | Not identified or not mentioned |

| Nilsson et al.16 | 2002 | 35 | 52 | Persistent disease |

| Akbari et al.10 | 2004 | 62 | 33 | Tumor size > 5 cm |

| Local extent | ||||

| Nodal disease | ||||

| Positive resection margins | ||||

| Ghouti et al.12 | 2005 | 36 | 69 | Not identified or not mentioned |

| Ferenschild et al.38 | 2005 | 18 | 30 | Not identified or not mentioned |

| Renehan et al.9 | 2005 | 73 | 40 | Positive resection margins |

| Mullen et al.15 | 2006 | 31 | 64 | Nodal disease |

| < 55 Gy radiotherapy dose | ||||

| Stewart et al.31 | 2007 | 22 | 24–48 | Tumor differentiation |

| Positive resection margins | ||||

| Schiller et al.17 | 2007 | 40 | 39 | Tumor size |

| Sex (male) | ||||

| Mariani et al.14 | 2008 | 83 | 57 | Age > 55 years |

| Nodal disease | ||||

| T3–4 tumor | ||||

| Local extent | ||||

| Sunesen et al.25 | 2009 | 49 | 61 | Positive resection margins |

| Eeson et al.32 | 2011 | 51 | 29 | Positive resection margins |

| Correa et al.24 | 2012 | 111 | 25 | Nodal disease |

| Positive resection margin | ||||

| Perineural and/or lymphovascular invasion | ||||

| Lefevre et al.13 | 2012 | 105 | 61 | T3–T4 status |

| Positive resection margins | ||||

| Metastatic disease | ||||

| Hallemeier et al.30 | 2014 | 32 | 23 | Recurrent disease versus persistent disease |

| Positive resection margins | ||||

| Viable disease in resection specimen | ||||

| Alamri et al.27 | 2016 | 27 | 78 | None identified |

| Pesi et al.26 | 2017 | 20 | 37 | None published |

| Present study | 2017 | 47 | 41 | Increased pathological tumor size (mm) |

| – | Nodal disease | |||

| – | Positive resection margins |

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epidermoid Anal Cancer: results from the UKCCCR randomised trial of radiotherapy alone versus radiotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, and mitomycin. UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial Working Party. UK Co-ordinating Committee on Cancer Research. Lancet. 1996;348(9034):1049–54. [PubMed]

- 3.Bartelink H, Roelofsen F, Eschwege F, et al. Concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is superior to radiotherapy alone in the treatment of locally advanced anal cancer: results of a phase III randomized trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Radiotherapy and Gastrointestinal Cooperative Groups. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(5):2040–2049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.5.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cummings BJ, Keane TJ, O’Sullivan B, Wong CS, Catton CN. Epidermoid anal cancer: treatment by radiation alone or by radiation and 5-fluorouracil with and without mitomycin C. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21(5):1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flam M, John M, Pajak TF, et al. Role of mitomycin in combination with fluorouracil and radiotherapy, and of salvage chemoradiation in the definitive nonsurgical treatment of epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal: results of a phase III randomized intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(9):2527–2539. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.9.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longo WE, Vernava AM, 3rd, Wade TP, Coplin MA, Virgo KS, Johnson FE. Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Predictors of initial treatment failure and results of salvage therapy. Ann Surg. 1994;220(1):40–49. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199407000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Northover J, Glynne-Jones R, Sebag-Montefiore D, et al. Chemoradiation for the treatment of epidermoid anal cancer: 13-year follow-up of the first randomised UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial (ACT I) Br J Cancer. 2010;102(7):1123–1128. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nigro ND, Vaitkevicius VK, Considine B., Jr Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: a preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum. 1974;17(3):354–356. doi: 10.1007/BF02586980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renehan AG, Saunders MP, Schofield PF, O’Dwyer ST. Patterns of local disease failure and outcome after salvage surgery in patients with anal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92(5):605–614. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akbari RP, Paty PB, Guillem JG, et al. Oncologic outcomes of salvage surgery for epidermoid carcinoma of the anus initially managed with combined modality therapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(7):1136–1144. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0548-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellenhorn JD, Enker WE, Quan SH. Salvage abdominoperineal resection following combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy for epidermoid carcinoma of the anus. Ann Surg Oncol. 1994;1(2):105–110. doi: 10.1007/BF02303552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghouti L, Houvenaeghel G, Moutardier V, et al. Salvage abdominoperineal resection after failure of conservative treatment in anal epidermoid cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(1):16–22. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0746-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lefevre JH, Corte H, Tiret E, et al. Abdominoperineal resection for squamous cell anal carcinoma: survival and risk factors for recurrence. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(13):4186–4192. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2485-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mariani P, Ghanneme A, De la Rochefordiere A, Girodet J, Falcou MC, Salmon RJ. Abdominoperineal resection for anal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(10):1495–1501. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mullen JT, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Chang GJ, et al. Results of surgical salvage after failed chemoradiation therapy for epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(2):478–483. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nilsson PJ, Svensson C, Goldman S, Glimelius B. Salvage abdominoperineal resection in anal epidermoid cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89(11):1425–1429. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiller DE, Cummings BJ, Rai S, et al. Outcomes of salvage surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(10):2780–2789. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith AJ, Whelan P, Cummings BJ, Stern HS. Management of persistent or locally recurrent epidermoid cancer of the anal canal with abdominoperineal resection. Acta Oncol. 2001;40(1):34–36. doi: 10.1080/028418601750071028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Wal BC, Cleffken BI, Gulec B, Kaufman HS, Choti MA. Results of salvage abdominoperineal resection for recurrent anal carcinoma following combined chemoradiation therapy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5(4):383–387. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(01)80066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zelnick RS, Haas PA, Ajlouni M, Szilagyi E, Fox TA, Jr. Results of abdominoperineal resections for failures after combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy for anal canal cancers. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35(6):574–77; discussion 577–78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Tobin GR, Day TG. Vaginal and pelvic reconstruction with distally based rectus abdominis myocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81(1):62–73. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vermaas M, Ferenschild FTJ, Hofer SOP, Verhoef C, Eggermont AMM, de Wilt JHW. Primary and secondary reconstruction after surgery of the irradiated pelvis using a gracilis muscle flap transposition. Eur J Surg Oncol (EJSO). 2005;31(9):1000–05. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Correa JH, Castro LS, Kesley R, et al. Salvage abdominoperineal resection for anal cancer following chemoradiation: a proposed scoring system for predicting postoperative survival. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107(5):486–492. doi: 10.1002/jso.23283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sunesen KG, Buntzen S, Tei T, Lindegaard JC, Norgaard M, Laurberg S. Perineal healing and survival after anal cancer salvage surgery: 10-year experience with primary perineal reconstruction using the vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous (VRAM) flap. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(1):68–77. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pesi B, Scaringi S, Di Martino C, et al. Results of surgical salvage treatment for anal canal cancer: a retrospective analysis with overview of the literature. Dig Surg. 2017;34(5):380–386. doi: 10.1159/000453589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alamri Y, Buchwald P, Dixon L, et al. Salvage surgery in patients with recurrent or residual squamous cell carcinoma of the anus. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(11):1687–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lefevre JH, Parc Y, Kerneis S, et al. Abdomino-perineal resection for anal cancer: impact of a vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneus flap on survival, recurrence, morbidity, and wound healing. Ann Surg. 2009;250(5):707–711. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bce334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allal AS, Laurencet FM, Reymond MA, Kurtz JM, Marti MC. Effectiveness of surgical salvage therapy for patients with locally uncontrolled anal carcinoma after sphincter-conserving treatment. Cancer. 1999;86(3):405–409. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990801)86:3<405::AID-CNCR7>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallemeier CL, You YN, Larson DW, et al. Multimodality therapy including salvage surgical resection and intraoperative radiotherapy for patients with squamous-cell carcinoma of the anus with residual or recurrent disease after primary chemoradiotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(4):442–448. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart D, Yan Y, Kodner IJ, et al. Salvage surgery after failed chemoradiation for anal canal cancer: should the paradigm be changed for high-risk tumors? J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(12):1744–1751. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eeson G, Foo M, Harrow S, McGregor G, Hay J. Outcomes of salvage surgery for epidermoid carcinoma of the anus following failed combined modality treatment. Am J Surg. 2011;201(5):628–633. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright JL, Gollub MJ, Weiser MR, et al. Surgery and high-dose-rate intraoperative radiation therapy for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(9):1090–1097. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318220c0a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faivre C, Rougier P, Ducreux M, et al. [5-Fluorouracil and cisplatinum combination chemotherapy for metastatic squamous-cell anal cancer] Carcinome épidermoide métastatique de l’anus: étude rétrospective de l’efficacité de l’association de 5-fluorouracile en perfusion continue et de cisplatine. Bull Cancer. 1999;86(10):861–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaiyesimi IA, Pazdur R. Cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil as salvage therapy for recurrent metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Am J Clin Oncol. 1993;16(6):536–540. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199312000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eng C, Chang GJ, You YN, et al. The role of systemic chemotherapy and multidisciplinary management in improving the overall survival of patients with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Oncotarget. 2014;5(22):11133–11142. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pocard M, Tiret E, Nugent K, Dehni N, Parc R. Results of salvage abdominoperineal resection for anal cancer after radiotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(12):1488–1493. doi: 10.1007/BF02237294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferenschild FT, Vermaas M, Hofer SO, Verhoef C, Eggermont AM, de Wilt JH. Salvage abdominoperineal resection and perineal wound healing in local recurrent or persistent anal cancer. World J Surg. 2005;29(11):1452–1457. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7957-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]