Abstract

Introduction

Apabetalone, a small molecule inhibitor, targets epigenetic readers termed BET proteins that contribute to gene dysregulation in human disorders. Apabetalone has in vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory and antiatherosclerotic properties. In phase 2 clinical trials, this drug reduced the incidence of major adverse cardiac events in patients with cardiovascular disease. Chronic kidney disease is associated with a progressive loss of renal function and a high risk of cardiovascular disease. We studied the impact of apabetalone on the plasma proteome in patients with impaired kidney function.

Methods

Subjects with stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease and matched controls received a single dose of apabetalone. Plasma was collected for pharmacokinetic analysis and for proteomics profiling using the SOMAscan 1.3k platform. Proteomics data were analyzed with Ingenuity Pathway Analysis to identify dysregulated pathways in diseased patients, which were targeted by apabetalone.

Results

At baseline, 169 plasma proteins (adjusted P value <0.05) were differentially enriched in renally impaired patients versus control subjects, including cystatin C and β2 microglobulin, which correlate with renal function. Bioinformatics analysis of the plasma proteome revealed a significant activation of 42 pathways that control immunity and inflammation, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, vascular calcification, and coagulation. At 12 hours postdose, apabetalone countered the activation of pathways associated with renal disease and reduced the abundance of disease markers, including interleukin-6, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and osteopontin.

Conclusion

These data demonstrated plasma proteome dysregulation in renally impaired patients and the beneficial impact of apabetalone on pathways linked to chronic kidney disease and its cardiovascular complications.

Keywords: bromodomain, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, epigenetics, inflammation, proteomics

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) afflicts approximately 11% of the general worldwide population, and represents an important global health challenge.1 CKD evolves over many years, with progressive loss of renal function, which could eventually lead to renal replacement therapy (dialysis) and kidney transplantation. Over the course of the disease, there is a progressive increase in both mortality and comorbidities, primarily due to the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD).2 Consequently, early therapeutic intervention is essential to slow CKD progression, prevent end-stage renal disease, and improve the quality of life and longevity of patients.

CKD is characterized by heightened levels of oxidative stress, advanced glycation end-products, proinflammatory cytokines, and uremic toxins.3 Pathogenic signaling initiated by these factors induces changes in epigenetic marks, including methylation and acetylation on chromatin-associated proteins.4, 5 BET proteins BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, and BRDT are epigenetic readers that use small interaction modules called bromodomains (BDs) to bind to acetylated lysine−tagged histones and transcription factors associated with transcriptionally active chromatin.6, 7, 8 Binding leads to the recruitment of the transcriptional machinery that drives gene expression.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 In disease states, abnormal signaling often results in overabundant or mislocalized acetylation marks, overexpression of BET proteins, and increased BET protein occupancy of gene regulatory regions.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 This causes changes to gene transcription patterns that control cell fate, proliferation and activation in cancer, fibrosis, autoimmunity, and inflammation.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Recently, BET proteins were shown to contribute to renal disorders, including experimental polycystic kidney disease and renal inflammatory disease.22, 23, 24, 25, 26 Importantly, in these studies, small molecule inhibitors targeting the BDs of BET proteins countered aberrant gene transcription, which led to improved renal outcomes.22, 23, 24, 26

Apabetalone (RVX-208) is a first-in-class orally available BET inhibitor (BETi) developed to treat CVD.27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 In biochemical assays, apabetalone targeted the second BD (BD2) of BET proteins with 20- to 30-fold selectivity.33, 34 In cells, BD2 binding by apabetalone resulted in differential transcriptional effects compared with a pan-BETi that targeted both BD1 and BD2 with equal affinity.34, 35 Apabetalone downregulated immune, inflammatory, and proatherosclerotic genes in ex vivo−treated human blood cells and primary hepatocytes, as well as in a mouse model of atherosclerosis.30, 36, 37, 38 Furthermore, apabetalone improved the plasma lipid profiles of CVD patients and significantly lowered the incidence of major adverse cardiac events in the Study of Quantitative Serial Trends in Lipids with Apolipoprotein A-I Stimulation (SUSTAIN) and the ApoA-I Synthesis Stimulation and Intravascular Ultrasound for Coronary Atheroma Regression Evaluation (ASSURE) phase 2 trials.30, 39 Although high-potency pan-BETi are currently being tested for cancer indications,40 apabetalone was the first BETi to enter clinical trials for the treatment of CVD. Determining the scope of the in vivo actions of apabetalone is currently an area of active investigation.27, 28, 29, 30, 31

CKD is characterized by a strong immune and inflammatory component that contributes to accelerated endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, atherosclerosis, and calcification.41, 42 CKD patients often succumb to cardiovascular complications because current therapies fail to treat the key pathogenic mechanisms underlying disease progression.43 To evaluate the potential of apabetalone as a CKD therapeutic, we examined the pharmacokinetics of apabetalone in a phase 1, open-label, parallel group study of patients with an estimated glomerular rate (eGFR) of <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Using a novel aptamer-based proteomics approach coupled to bioinformatics, we identified proteins enriched in the plasma from patients with impaired kidney function, relative to control subjects. Furthermore, we demonstrated that a single dose of apabetalone downregulated plasma markers of endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis, vascular inflammation, calcification, fibrosis, hemostasis, and chronic inflammation, countering the pathogenic signaling in CKD patients. These findings suggest that apabetalone treatment might benefit CKD patients.

Methods

Patient Selection

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. The phase I apabetalone pharmacokinetic study consisted of 2 cohorts of 8 subjects each who received a single 100-mg oral dose of apabetalone after a meal. Cohort 1 consisted of subjects with stage 4 or 5 CKD who were not on dialysis, with an eGFR of <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and a mean eGFR of 20 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Cohort 2 consisted of control subjects matched to the renally impaired subjects in age, weight, and sex, as well as an eGFR of ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, with mean eGFR of 78.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Additional characteristics of the cohorts are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients enrolled in the phase 1 pharmacokinetics study

| Characteristics | Cohort 1 renal impaired (n = 8) | Cohort 2 controls (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 55.9 ± 16.5 | 52.6 ± 16.5 |

| Male sex | 5 (63) | 5 (63) |

| White race | 8 (100) | 8 (100) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic or Non-Latino | 8 (100) | 8 (100) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.1 ± 5.1 | 25.5 ± 3.0 |

| Median clinical chemistry measures | ||

| Albumin (g/l) | 36.0 ± 4.1 | 39.8 ± 3.1 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/l) | 113.1 ± 60.4 | 73.0 ± 16.2 |

| CKD-EPI (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 18.8 ± 5.9 | 78.4 ± 10.6 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/l) | 305.3 ± 104.9 | 87.9 ± 10.3 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/l) | 21.9 ± 10.5 | 6.1 ± 1.9 |

| Blood pressure | ||

| Systolic (mm Hg) | 132.8 ± 26.4 | 129.0 ± 21.7 |

| Diastolic (mm Hg) | 67.4 ± 14.8 | 71.5 ± 12.7 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Hypertension | 5 | 3 |

| Hypo/hyperthyroidism | 2 | 0 |

| Diabetes | 1 | 0 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 | 0 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1 | 0 |

| Allergy | 1 | 1 |

| Autoimmune | 1 | 1 |

| Genetic disorder | 1 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1 | 0 |

Values are number (%), mean ± SD, or number.

BMI, body mass index; CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology equation.

Apabetalone Pharmacokinetics and Safety

Blood samples for determination of plasma concentration of apabetalone were collected at the following time points: baseline and at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 24, 34, and 48 hours postdose. Total voided urine for determining urinary excretion of apabetalone was collected over the following intervals: baseline (single-void), 0 to 4, 4 to 8, 8 to 12, 12 to 24, and 24 to 48 hours postdose. Plasma and urine pharmacokinetic samples were shipped to and processed by Intertek Pharmaceutical Services (San Diego, California). Safety assessments included monitoring of adverse events, vital signs, clinical laboratory findings, 12-lead electrocardiograms, and physical examination.

SOMAscan Analysis

Patient plasma samples collected at baseline and at 6, 12, 24, 48 hours after the single apabetalone dose underwent proteomic analysis using the SOMAscan 1.3k platform (SomaLogic, Boulder, Colorado).44 SOMAscan uses modified aptamers to simultaneously detect 1305 proteins. The assay can quantify proteins that span over 8 logs in abundance (from femtomolar to micromolar), which allows direct analysis of plasma samples without depletion of abundant proteins. The SOMAscan assay transforms protein concentrations into DNA aptamer concentrations that are quantifiable on a DNA microarray. Changes in relative fluorescent units, which are directly proportional to the amount of target protein in the initial sample, were expressed relative to baseline.44

Statistical Analysis

To assess the differential protein levels at baseline between cohort 1 and cohort 2, the Mann-Whitney test was used when data were not normally distributed; otherwise Student’s t-tests were used. The Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) multiple testing correction was used to generate FDR-adjusted P values. An adjusted P value < 0.05 was considered significant. Shapiro-Wilk tests were used to determine data distribution.

Changes in protein levels were compared from baseline to 12 hours post-apabetalone dose in all patients. For normally distributed protein parameters, paired Student’s t-tests were used to examine the change in protein levels, whereas the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied for non-normally distributed parameters. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. Shapiro-Wilk tests were used to determine data distribution.

Pathway Analysis

QIAGEN’s Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (IPA; QIAGEN, Redwood City, California; www.qiagen.com/ingenuity) was used to interpret the proteomics data.

Results

Pharmacokinetics of Apabetalone in Control and Stage 4 or 5 CKD Patients

In this study, we compared 8 subjects with eGFRs ranging from 9 to 29 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (cohort 1, CKD stage 4 or 5, and median creatinine clearance 18.8 ml/min per square meter) and 8 subjects with eGFR ranging from 66 to 109 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (cohort 2, age-, sex-, weight-matched, and median creatinine clearance 78.4 ml/min per square meter). In addition to stage 4 or 5 CKD, cohort 1 also displayed comorbidities that commonly accompany renal disease, including CVD, diabetes, and hypothyroidism (Table 1). Baseline plasma samples were obtained from both cohorts to assess clinical biochemistry parameters. Comparison of apabetalone pharmacokinetics following a single dose revealed that the maximum (peak) serum concentration, area under the curve, time to reach maximum (peak) serum concentration (Tmax), and terminal half-life were similar for both the renally impaired and matched subjects (Supplementary Table S1). Minimal amounts of apabetalone were excreted in the urine of either cohort (Supplementary Table S2), which is consistent with the elimination of apabetalone through hepatic clearance. No significant adverse events occurred during the study in the control or the CKD cohorts (data not shown).

Plasma Proteome Profiling in CKD Patients

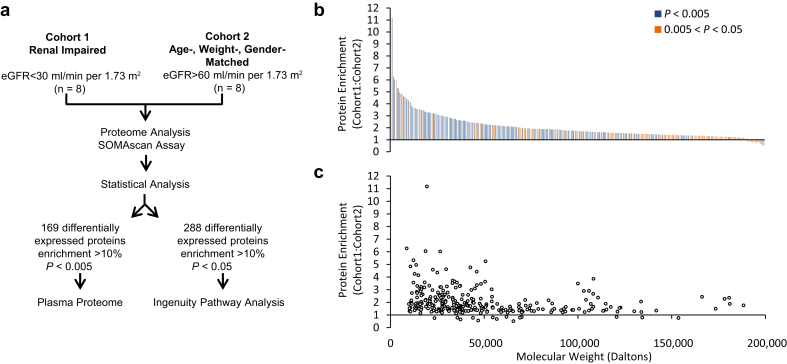

To gain insight into the molecular mechanisms that underlie CKD and its comorbidities, the proteomic composition of plasma samples from late-stage CKD (cohort 1) and control (cohort 2) subjects was assessed at baseline with the SOMAscan 1.3k platform (Figure 1a).44 Two hundred eighty-eight proteins were differentially expressed between the 2 cohorts (difference >10%, P < 0.05, FDR <0.2) (Figure 1b and Supplementary Table S3), forming a database for functional pathway analysis. Upon correction for multiple testing, 167 proteins remained significantly upregulated, whereas 2 proteins were downregulated in the CKD cohort (difference >10%, P < 0.005, FDR <0.05) (Figure 1b and Supplementary Table S3, column F).

Figure 1.

SOMAscan analysis of the plasma proteome. Study design flowchart (a). Proteins differentially expressed in the CKD cohort are plotted according to their fold enrichment (b). The degree of significance is color coded (see legend). Note that p values tend to be highly significant for highly enriched proteins. Fold enrichment as a function of protein molecular weight (c). Note that the majority of enriched proteins have a molecular weight of <45 kDa. Protein enrichment also tends to be greater for proteins with molecular weight <45 kDa.

CKD progression is accompanied by an overall increase in the plasma concentration of low-molecular-weight (LMW; <45 kDa) proteins due to a decline in the filtration capacity of the kidneys.45, 46 Analysis showed that 173 of the 288 CKD cohort-enriched proteins were LMW proteins. These LMW proteins showed a greater fold enrichment in the CKD cohort compared with proteins of >45 kDa (2.3 ± 1.2 vs. 1.7 ± 0.76, respectively; P = 0.000024; Student’s t-test) (Figure 1c). Many of the enriched LMW proteins are well-established biomarkers that correlate with kidney function,47 including cystatin C (3.1-fold), β-2-microglobulin (5-fold), neutrophil gelatinase−associated lipocalin (4.6-fold), liver fatty acid−binding protein (2.7-fold), and fibroblast growth factor 23 (1.8-fold) (Supplementary Table S3 and references therein). Numerous uremic toxins, as classified by the European Toxin Work Group,45 were also upregulated in the CKD cohort (Supplementary Table S4). Other enriched proteins included cytokines and their soluble receptors, adhesion molecules, metalloproteases, and complement and coagulation proteins, as well as factors involved in calcification, metabolism, and oxidative stress (Supplementary Table S3).

Gene ontology analysis48 of the CKD cohort−associated proteins (FDR <0.2) showed significant enrichment of 53 terms in the molecular function category (Supplementary Table S5). The top 21 enriched terms (Table 2) were related to ligand-receptor signaling, with 9 linked to cytokine and chemokine pathways. IPA,49 with its manually curated database from peer-reviewed literature, further predicted not only the impact of disease on cellular functions (P values), but also the direction of change by calculating the activation z-score (Supplementary Table S6). Analysis showed that 234 “disease or function” annotations were increased in the CKD cohort (z score >2), whereas 6 annotations were decreased (z score <−2). In particular, top pathways (Table 3) which referred to immune and inflammatory cell migration, proliferation, differentiation, activation, and viability, were all upregulated in plasma from the CKD cohort compared with the control cohort. The IPA analysis also predicted a marked upregulation of 42 canonical pathways (z score >2) and a downregulation of 2 pathways (z-score: <−2), with functions in immune and inflammatory responses, endothelial dysfunction, coagulation, renin-angiotensin system, calcification, and oxidative stress (Table 4). Thus, our bioinformatics analysis highlighted many of the underlying dysfunctional pathways that contribute to CKD and its comorbidities.

Table 2.

Gene ontology term molecular function analysis of CKD-enriched proteins: top 21 terms (z-score >2.0; P < 0.0001)

| GO term | Molecular function | P value |

|---|---|---|

| GO:0005102 | Receptor binding | 4.0 × 10−45 |

| GO:0005125 | Cytokine activity | 2.7 × 10−23 |

| GO:0005126 | Cytokine receptor binding | 1.7 × 10−22 |

| GO:0005515 | Protein binding | 8.5 × 10−19 |

| GO:0004872 | Receptor activity | 8.1 × 10−13 |

| GO:0060089 | Molecular transducer activity | 8.1 × 10−13 |

| GO:0019955 | Cytokine binding | 8.3 × 10−13 |

| GO:0008083 | Growth factor activity | 1.2 × 10−12 |

| GO:0008009 | Chemokine activity | 5.4 × 10−11 |

| GO:0004871 | Signal transducer activity | 1.9 × 10−10 |

| GO:0005035 | Death receptor activity | 2.8 × 10−10 |

| GO:0005031 | Tumor necrosis factor-activated receptor activity | 2.8 × 10−10 |

| GO:0019199 | Transmembrane receptor protein kinase activity | 3.2 × 10−10 |

| GO:0042379 | Chemokine receptor binding | 8.4 × 10−10 |

| GO:0001664 | G-protein coupled receptor binding | 1.1 × 10−8 |

| GO:0005488 | Binding | 3.0 × 10−8 |

| GO:0038023 | Signaling receptor activity | 5.1 × 10−8 |

| GO:0005539 | Glycosaminoglycan binding | 5.9 × 10−8 |

| GO:0004896 | Cytokine receptor activity | 2.4 × 10−7 |

| GO:0019838 | Growth factor binding | 3.1 × 10−7 |

| GO:0048020 | CCR chemokine receptor binding | 6.0 × 10−7 |

GO, gene ontology.

Table 3.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis disease or functions analysis of CKD-enriched proteins: top 21 terms (z score >2.0; P < 0.0001)

| IPA: diseases or functions annotation | Z score | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Cell movement | 6.2 | 7.9 × 10−74 |

| Migration of cells | 6.4 | 1.1 × 10−71 |

| Leukocyte migration | 5.7 | 3.1 × 10−63 |

| Cell movement of leukocytes | 5.3 | 1.5 × 10−58 |

| Proliferation of cells | 4.5 | 4.8 × 10−56 |

| Cell movement of myeloid cells | 5.0 | 5.6 × 10−52 |

| Quantity of cells | 2.3 | 2.3 × 10−51 |

| Activation of cells | 5.2 | 3.7 × 10−50 |

| Cell movement of phagocytes | 5.4 | 7.4 × 10−49 |

| Activation of blood cells | 4.4 | 7.0 × 10−47 |

| Inflammatory response | 4.1 | 9.4 × 10−47 |

| Activation of leukocytes | 4.7 | 1.2 × 10−44 |

| Quantity of blood cells | 2.9 | 5.0 × 10−44 |

| Cell movement of granulocytes | 4.5 | 2.9 × 10−42 |

| Chemotaxis | 5.9 | 5.2 × 10−41 |

| Quantity of leukocytes | 2.8 | 1.4 × 10−40 |

| Homing of cells | 5.8 | 2.3 × 10−40 |

| Recruitment of cells | 3.8 | 3.6 × 10−40 |

| Differentiation of cells | 4.6 | 4.6 × 10−39 |

| Growth of tumor | 3.7 | 1.7 × 10−38 |

| Cell movement of mononuclear leukocytes | 5.1 | 4.5 × 10−38 |

IPA, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

Table 4.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis of proteins enriched in the CKD cohort and the impact of apabetalone in the CKD cohort at 12 hours postdose versus baseline

| Ingenuity Pathway Analysis | CKD vs. control: baseline |

CKD: apabetalone |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| z score | P value | z score | P value | |

| Dendritic cell maturation | 3.46a | <0.0001 | −4.12b | <0.0001 |

| IL-6 signaling | 3.21a | <0.0001 | −3.46b | <0.0001 |

| Th1 pathway | 3.16a | <0.0001 | −3.32b | <0.0001 |

| Colorectal cancer metastasis signaling | 3.13a | <0.0001 | −3.50b | <0.0001 |

| NF-κB signaling | 3.05a | <0.0001 | −3.46b | <0.0001 |

| Acute phase response signaling | 2.89a | <0.0001 | −3.46b | <0.0001 |

| HMGB1 signaling | 2.84a | <0.0001 | −3.50b | <0.0001 |

| IL-17A signaling in airway cells | 2.83a | <0.0001 | −2.33b | <0.0001 |

| Type I diabetes mellitus signaling | 2.83a | <0.0001 | −2.65b | <0.0001 |

| Role of NFAT in cardiac hypertrophy | 2.83a | 0.004 | <0.0001 | |

| Death receptor signaling | 2.83a | <0.0001 | −2.12b | <0.0001 |

| p38 MAPK signaling | 2.65a | 0.0008 | −3.32b | <0.0001 |

| STAT3 Pathway | 2.53a | <0.0001 | −1.63 | 0.0002 |

| Production of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in macrophages | 2.50a | <0.0001 | −3.16b | 0.0001 |

| VEGF family ligand-receptor interactions | 2.45a | 0.001 | −3.16b | <0.0001 |

| VEGF signaling | 2.45a | 0.003 | −2.33b | <0.0001 |

| Nitric oxide signaling in the cardiovascular system | 2.45a | 0.006 | −3.00b | <0.0001 |

| Induction of apoptosis by HIV1 | 2.45a | 0.0001 | −1.63 | <0.0001 |

| PAK signaling | 2.45a | 0.002 | −2.65b | 0.0002 |

| CNTF signaling | 2.45a | 0.0002 | −2.00b | 0.006 |

| Oncostatin M signaling | 2.45a | <0.0001 | 0.007 | |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma signaling | 2.33a | <0.0001 | −2.53b | <0.0001 |

| ILK signaling | 2.33a | 0.001 | −2.89b | <0.0001 |

| Renin-angiotensin signaling | 2.33a | <0.0001 | −2.83b | 0.0001 |

| Cardiac hypertrophy signaling | 2.33a | 0.004 | −3.16b | 0.0006 |

| Role of pattern recognition receptors in recognition of bacteria and viruses | 2.24a | 0.0004 | −2.45b | <0.0001 |

| IL-22 signaling | 2.24a | <0.0001 | −1.63 | <0.0001 |

| Tec kinase signaling | 2.24a | 0.02 | −3.16b | <0.0001 |

| Role of NANOG in mammalian embryonic stem cell pluripotency | 2.24a | 0.001 | −2.45b | <0.0001 |

| Coagulation system | 2.24a | <0.0001 | −0.45 | <0.0001 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus signaling | 2.24a | 0.04 | −3.00b | <0.0001 |

| NGF signaling | 2.24a | 0.02 | −2.65b | 0.0006 |

| Melanocyte development and pigmentation signaling | 2.24a | 0.008 | −2.24b | 0.005 |

| Corticotropin releasing hormone signaling | 2.24a | 0.0009 | −2.00b | 0.01 |

| Notch signaling | 2.24a | 0.0001 | 0.07 | |

| BMP signaling pathway | 2.12a | <0.0001 | −2.45b | 0.0003 |

| IL-8 signaling | 2.11a | <0.0001 | −3.74b | <0.0001 |

| PEDF signaling | 2.00a | 0.004 | −2.53b | <0.0001 |

| GM-CSF signaling | 2.00a | 0.02 | −3.00b | <0.0001 |

| Role of PI3K/AKT signaling in the pathogenesis of influenza | 2.00a | 0.02 | −2.83b | <0.0001 |

| Role of IL-17F in allergic inflammatory airway diseases | 2.00a | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | |

| Ephrin B signaling | 2.00a | 0.003 | 0.6 | |

| PPAR signaling | −2.12b | <0.0001 | 2.24a | 0.005 |

| Antioxidant action of vitamin C | −2.24b | 0.01 | 2.45a | 0.0003 |

BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; CNTF, ciliary neurotrophic factor; ILK, integrin-linked protein kinase; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HMGB1, high mobility group box-1; IL, interleukin; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NANOG, nanog homeobox; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T-cells; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NGF, nerve growth factor; PAK, p-21-activated kinase; PEDF, pigment epithelium-derived factor; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Predicated activation is indicated by a z score >2.0.

Predicated repression is indicated by a z score <−2.

Apabetalone Downregulates Markers and Pathways Upregulated in Plasma From Renally Impaired Cohort

To enable assessment of the CKD cohort’s response to apabetalone, target engagement was evaluated at multiple time points postdose. At 12 hours, the known BETi target engagement marker lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG3)18, 23 was maximally downregulated (Supplementary Figure S1). Recovery of LAG3 plasma expression was observed following drug clearance (Supplementary Figure S1). Therefore, the impact of apabetalone on plasma protein levels in the CKD cohort was analyzed 12 hours postdose (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effect of apabetalone on CKD and cardiovascular disease protein biomarkers in plasma from CKD and control patients

| Protein | Gene | CKD vs. control: baseline |

CKD (n = 8): apabetalone |

Control (n = 8): apabetalone |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Ratio | P valuea | % Change from baselineb | P valuec | % Change from baselineb | P valuec | ||

| Inflammation | |||||||

| IL-6 | IL6 | 1.3 | 0.1 | −29.0 | 0.05 | 42.3 | 0.25 |

| IL-17A | IL17A | 1.2 | 0.4 | −13.3 | 0.02 | −7.8 | 1.00 |

| IL-15 receptor subunit α | IL15RA | 2.5 | 0.0002 | −12.0 | 0.02 | −8.5 | 0.84 |

| IL-12 | IL12A IL12B | 1.0 | 0.3 | −11.5 | 0.04 | −3.4 | 1.00 |

| IL-23 | IL12B IL23A | 3.3 | 0.003 | −11.3 | 0.01 | 3.4 | 0.64 |

| IL-1 α | IL1A | 1.4 | 0.1 | −10.8 | 0.01 | 1.3 | 0.55 |

| Extracellular matrix remodelling | |||||||

| Fibronectin | FN1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | −24.7 | 0.02 | 3.6 | 0.55 |

| Fibronectin fragment 3 | FN1 | 1.1 | 0.5 | −18.0 | 0.04 | 3.5 | 0.55 |

| Stromelysin-1 | MMP3 | 3.0 | 0.002 | −15.4 | 0.02 | 7.4 | 0.84 |

| Stromelysin-2 | MMP10 | 2.4 | 0.0002 | −10.9 | 0.02 | −1.8 | 0.55 |

| Fibronectin fragment 4 | FN1 | 1.3 | 0.05 | −10.6 | 0.04 | 14.6 | 0.55 |

| Vascular calcification | |||||||

| Osteopontin | SPP1 | 3.6 | 0.0002 | −17.9 | 0.01 | −15.9 | 0.04 |

| Thrombosis, fibrinolysis, and platelet activation | |||||||

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 | SERPINE1 | 0.9 | 1 | −41.6 | 0.04 | 11.0 | 0.84 |

| Tissue-type plasminogen activator | PLAT | 0.7 | 0.6 | −27.8 | 0.01 | −14.3 | 0.11 |

| P-selectin | SELP | 1.0 | 0.9 | −22.5 | 0.04 | 8.0 | 0.74 |

| Urokinase-type plasminogen activator | PLAU | 1.1 | 1 | −17.5 | 0.01 | −11.7 | 0.02 |

| Complement activation | |||||||

| Complement C3b | C3 | 0.4 | 0.07 | −19.0 | 0.04 | 8.7 | 0.95 |

| C5a anaphylatoxin | C5 | 1.8 | 0.01 | −12.1 | 0.04 | −22.4 | 0.01 |

| Complement C3d fragment | C3 | 1.0 | 0.4 | −10.5 | 0.04 | −9.0 | 0.02 |

IL, interleukin.

P value comparing baseline between cohorts calculated using Mann-Whitney test.

Results expressed as median percent change from baseline.

P value comparing change vs. baseline calculated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Numerous plasma proteins with physiological functions relevant for CKD and CVD were downregulated by apabetalone in the CKD cohort. Circulating proatherogenic, inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1, IL-17, IL-12, and IL-23, as well as the IL-15 receptor subunit α, decreased in abundance with apabetalone treatment (10%−29%) (Table 5). Apabetalone reduced levels of metalloproteases (MMP-3, MMP-10) and extracellular matrix proteins (fibronectin, osteopontin) (11%−25%). Markers of fibrinolysis were also downregulated, including plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, tissue-type plasminogen activator, and urokinase-like plasminogen activator (42%, 28% and 18%, respectively), as well as a marker of platelet activation and vascular inflammation, P-selectin (23%). Furthermore, apabetalone decreased the abundance of activated fragments of complement proteins, including anaphylatoxin C5a (12%) (Table 5). In contrast, apabetalone had limited effects on disease biomarkers in the control cohort (Table 5).

To gain insight into the functional effects of apabetalone, the impact of apabetalone on the IPA canonical pathways upregulated in plasma from the CKD cohort was assessed (Table 4). Remarkably, apabetalone reversed the activation of 33 of 42 pathways in the CKD cohort, with the greatest impact on pathways that were most upregulated in the CKD patients (Table 4). These canonical pathways regulate inflammation through cytokine signaling, acute phase response, T-cell, and dendritic cell responses. Further, apabetalone downregulated other pathways relevant to CKD pathophysiology: vascular calcification (bone morphogenetic protein signaling), fibrosis (integrin-linked protein kinase signaling), apoptosis (death cell receptor signaling), angiogenesis (vascular endothelial growth factor and pigment epithelium-derived factor signaling), nitric oxide, and reactive oxygen species signaling. Moreover, intracellular signaling pathways converging on the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) were also downregulated by apabetalone, whereas the peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor pathway was upregulated, countering pathogenic signaling in CKD.50, 51 Finally, pathways that contribute to comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiac hypertrophy, were also downregulated by apabetalone (Table 4). Overall, apabetalone simultaneously modulated multiple pathways that contribute to CKD pathology and associated vascular complications.

Discussion

Changes in plasma protein composition are a central feature of CKD pathophysiology and its associated comorbidities. Until recently, however, attempts to study the plasma proteome have been hampered by the complexity of the plasma protein composition and inherent limitations of mass spectrometry.52, 53, 54 SOMAscan is a powerful protein discovery tool that can simultaneously detect 1305 proteins representative of various cellular functions.44 Here, a total of 169 proteins (adjusted P < 0.05) were identified as differentially expressed in plasma from control and renally impaired cohorts. Approximately 60% were LMW proteins (<45 kDa), consistent with the impairment of kidney filtration in late stage CKD.45, 46 The plasma proteome presented here shows little overlap with previously published mass spectrometry driven studies (Supplementary Table S3, column J).52, 53, 54 In contrast, our data largely corroborates the results of a previous SOMAscan study,44 in which a smaller panel (614 aptamers) was used to assess stages 3 to 5 CKD patient plasma composition. Forty-five of the 60 markers identified by Gold et al.,44 were also detected in this study (Supplementary Table S3, column J). Differences may be due to cohort size and composition. Many of the enriched proteins are well established CKD biomarkers that correlate with kidney function and CKD or CVD outcomes (Supplementary Table S3, columns H and I). These proteins play a role in inflammation, vascular calcification, thrombosis, cell adhesion, extracellular matrix remodeling, oxidative stress, and metabolism. Interestingly, several of the enriched proteins we identified have not been previously linked to CKD or CVD. Establishing the functional relevance of these novel CKD cohort-enriched proteins and determining their prognostic value presents exciting avenues for future studies.

Analysis of plasma from renally impaired patients revealed that a single dose of apabetalone rapidly downregulated multiple CKD and CVD protein markers (Table 5), as well as associated molecular pathways (Table 4). In contrast, in the control cohort, apabetalone had no significant effect on pathway activation or repression (as determined by the IPA z-score; data not shown), or on the abundance of most circulating disease markers (Table 5). This differential sensitivity to a BET protein inhibitor highlights the dysregulation of BET protein-dependent pathways in human CKD, which is consistent with published data from cell and animal models.21, 23, 26

Inflammation contributes to the onset and progression of renal disease.41 Indeed, 40% of the 288 proteins upregulated in the CKD cohort are directly or indirectly linked to inflammation (Supplementary Table S3). The most prevalent among these are cytokines and chemokines known to be dysregulated in CKD and its comorbodities.55 In plasma from the CKD cohort, there was an increase in circulating cytokines (Supplementary Table S3), and pathways controlled by IL-6, IL-17, oncostatin M, IL-22, IL-8, and granulocyte-macrophage, colony-stimulating factor were predicted to be activated (Table 4). Significantly, a single dose of apabetalone reduced the plasma protein levels of multiple cytokines and chemokines, including IL-6, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-23 (Table 5). In addition, apabetalone was predicted to counter the CKD cohort−associated upregulation of cytokine pathways, including IL-6, IL-8, and IL-17 (Table 4). Essential components of the innate and adaptive immune system56, 57 were among the top upregulated pathways in the CKD cohort, including the dendritic cell maturation and Th1 signaling pathways (Table 4, and Supplementary Figures S2 and S3). Extensive cross-talk occurred between these 2 pathways, with activated dendritic cells stimulating inflammatory Th1 lymphocyte responses, which, in turn, promoted dendritic cell maturation.58 Apabetalone had a significant impact on both pathways (z scores: −4.2 and −3.3, respectively) (Table 4, and Supplementary Figures S2 and S3), which was consistent with published data.30, 38

Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 induce the acute phase response (APR) protein expression and secretion by the liver.59 Multiple APR proteins were upregulated in plasma from the CKD cohort potentially due to increased IL-6 signaling (as predicted by IPA) (Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Figures S4 and S5). APR signaling pathway was ranked the sixth most activated pathway in CKD plasma (Table 4). APR proteins are markers of disease progression and become highly enriched in the plasma of stage 3 and 4 CKD patients.53, 54 Interestingly, this enrichment is greater in plasma of patients with CKD than in the plasma of CVD patients,53 which indicates that inflammation is exacerbated in patients with advanced kidney failure.41 Of note, the APR pathway was robustly downregulated by apabetalone (z score: −3.46) (Table 4 and Supplementary Figure S5), in line with previously published data.30, 37, 38

Consistent with the susceptibility of CKD patients to thrombosis and bleeding,60 the coagulation system pathway was upregulated in plasma from the CKD cohort (Table 4). Several circulating hemostatic factors were predictive of CVD events.61, 62 Apabetalone significantly decreased markers of the fibrinolysis pathway (including plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, urokinase-like plasminogen activator, and tissue-type plasminogen activator) (Table 5), which are associated with disturbances in hemostasis63 and atherosclerosis64 in CKD patients. Inflammation and coagulation can activate the complement cascade, propagating and amplifying proinflammatory signaling and damage.65 In agreement with previous studies,37 apabetalone reduced the plasma concentration of activated C3 fragments and of the anaphylatoxin C5a, a marker that has been correlated with CVD outcomes.66, 67, 68 To date, no adverse events related to coagulation nor complement system dysregulation have been observed in clinical trials with apabetalone37 (and unpublished data).

Increased acetylation of gene promoters and transcription factors such as STAT3 and NF-κB have been detected in cultured renal cells and animal models of inflammatory renal disease.23, 69, 70, 71 These aberrant acetylated lysine residues become the target of BET proteins (e.g., BRD4) that then drive transcription of inflammatory genes.23, 71 Apabetalone downregulated the abundance of multiple NF-κB target proteins in plasma from the CKD cohort, including IL-6, IL-1α, IL-12, IL-23, MMP-3, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (Table 5), and decreased the predicted activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway (z-score: −3.5) (Table 4 and Supplementary Figure S6). These data corroborate previously reported inhibition of NF-κB−dependent pathways by BETi.16, 23

Current therapies fail to counter progressive systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, vascular calcification, fibrosis, and atherosclerosis in patients with CKD.43 The plasma proteome study reported here demonstrated that apabetalone might oppose many of these pathogenic pathways in patients with CKD (and its accompanying comorbidities) by rapidly downregulating plasma markers associated with these dysfunctions. Considering its favorable pharmacokinetic properties in CKD patients and a well-established safety profile,29, 32 apabetalone is a potential therapeutic agent capable of modulating molecular pathways associated with risk factors that drive CKD progression and its cardiovascular complications.

Disclosure

SW, LMT, CH, SCS, DG, RJ, MS, JOJ, NCW, and EK are employees and shareholders of Resverlogix Corp. which supported the study financially. KK-Z is an advisory board member of Resverlogix Corp. The other author declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Aziz Khan, Pamod Hemakumara, Dr. Chris Sarsons, and Emily Daze for proteomics data analysis, as well as Ken Lebioda, Dr. Srinivasan Beddhu, Dr. Vincent Brandenburg, Dr. Mathias Haarhaus, Dr. Marcello Tonelli, and Dr. Carmine Zoccali for intellectual input.

Author Contributions

RR, RJ, MS, JOJ, NCW, KK-Z, and EK participated in the clinical trial design. SW, LMT, EK, and CH analyzed the data and interpreted the results. SW and SCS wrote the manuscript. MS, JOJ, NCW, EK, LMT, and DG critically reviewed the manuscript. The final version was approved by all authors.

Footnotes

Table S1. Pharmacokinetic assessment of the renal impaired cohort 1 and matched control cohort 2 following a single apabetalone dose (100 mg).

Table S2. Urine output measured as the fractional excretion (Fe%) of apabetalone for the renal impaired cohort 1 and matched control cohort 2 following a single apabetalone dose (100 mg).

Table S3. Complete annotated list of 288 proteins enriched in CKD (P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). Baseline comparison of cohort 1 versus cohort 2 (enrichment: red indicates upregulation, blue indicates downregulation), and its statistical significance are shown in columns D, E, and F. References supporting links to renal, cardiovascular or inflammatory diseases and diabetes are listed columns H and I). Plasma proteomic studies that identified protein enrichment in CKD patients are cited (column J).

Table S4. Uremic toxins enriched in the plasma from CKD cohort relative to the control cohort.

Table S5. Gene ontology term molecular function analysis of proteins enriched in CKD plasma: complete list of 53.

Table S6. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis disease or functions analysis of proteins enriched in CKD plasma: complete list.

Figure S1. Target engagement time course. Apabetalone (blue circles and line) and LAG3 (orange diamonds and line) serum concentrations measured at discrete time intervals following a single apabetalone dose. Representative data from a single patient.

Figure S2. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: dendritic cell maturation. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to apabetalone 12 hourpost single dose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Figure S3. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: Th1 signaling. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to single apabetalone 12 hour postdose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Figure S4. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: interleukin-6 signaling. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to single apabetalone 12 hour postdose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Figure S5. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: acute phase response signaling. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to single apabetalone 12 hour postdose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Figure S6. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: nuclear factor-κb signaling. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to single apabetalone 12 hour postdose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at www.kireports.org.

Supplementary Material

Pharmacokinetic assessment of the renal impaired cohort 1 and matched control cohort 2 following a single apabetalone dose (100 mg).

Urine output measured as the fractional excretion (Fe%) of apabetalone for the renal impaired cohort 1 and matched control cohort 2 following a single apabetalone dose (100 mg).

Complete annotated list of 288 proteins enriched in CKD (P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). Baseline comparison of cohort 1 versus cohort 2 (enrichment: red indicates upregulation, blue indicates downregulation), and its statistical significance are shown in columns D, E, and F. References supporting links to renal, cardiovascular or inflammatory diseases and diabetes are listed columns H and I). Plasma proteomic studies that identified protein enrichment in CKD patients are cited (column J).

Uremic toxins enriched in the plasma from CKD cohort relative to the control cohort.

Gene ontology term molecular function analysis of proteins enriched in CKD plasma: complete list of 53.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis disease or functions analysis of proteins enriched in CKD plasma: complete list.

Target engagement time course. Apabetalone (blue circles and line) and LAG3 (orange diamonds and line) serum concentrations measured at discrete time intervals following a single apabetalone dose. Representative data from a single patient.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: dendritic cell maturation. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to apabetalone 12 hourpost single dose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: Th1 signaling. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to single apabetalone 12 hour postdose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: interleukin-6 signaling. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to single apabetalone 12 hour postdose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: acute phase response signaling. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to single apabetalone 12 hour postdose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: nuclear factor-κb signaling. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to single apabetalone 12 hour postdose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

References

- 1.Mills K.T., Xu Y., Zhang W. A systematic analysis of worldwide population-based data on the global burden of chronic kidney disease in 2010. Kidney Int. 2015;88:950–957. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alani H., Tamimi A., Tamimi N. Cardiovascular co-morbidity in chronic kidney disease: current knowledge and future research needs. World J Nephrol. 2014;3:156–168. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v3.i4.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zoccali C., Vanholder R., Massy Z.A. The systemic nature of CKD. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:344–358. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witasp A., Van Craenenbroeck A.H., Shiels P.G. Current epigenetic aspects the clinical kidney researcher should embrace. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017;131:1649–1667. doi: 10.1042/CS20160596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wing M.R., Ramezani A., Gill H.S. Epigenetics of progression of chronic kidney disease: fact or fantasy? Semin Nephrol. 2013;33:363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filippakopoulos P., Picaud S., Mangos M. Histone recognition and large-scale structural analysis of the human bromodomain family. Cell. 2012;149:214–231. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filippakopoulos P., Qi J., Picaud S. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature. 2010;468:1067–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taniguchi Y. The bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) family: functional anatomy of BET paralogous proteins. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17111849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itzen F., Greifenberg A.K., Bösken C.A. Brd4 activates P-TEFb for RNA polymerase II CTD phosphorylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:7577–7590. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroder S., Cho S., Zeng L. Two-pronged binding with bromodomain-containing protein 4 liberates positive transcription elongation factor b from inactive ribonucleoprotein complexes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:1090–1099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.282855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanno T., Kanno Y., LeRoy G. BRD4 assists elongation of both coding and enhancer RNAs by interacting with acetylated histones. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:1047–1057. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winter G.E., Mayer A., Buckley D.L. BET bromodomain proteins function as master transcription elongation factors independent of CDK9 recruitment. Mol Cell. 2017;67:5–18.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W.-S., Prakash C., Sum C. Bromodomain-containing-protein 4 (BRD4) regulates RNA polymerase II serine 2 phosphorylation in human CD4+ T cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:43137–43155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.413047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denis G.V. Bromodomain coactivators in cancer, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and inflammation. Discov Med. 2010;10:489–499. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaefer U. Pharmacological inhibition of bromodomain-containing proteins in inflammation. Cold Spring Harbor Persp Biol. 2014;6 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown J.D., Lin C.Y., Duan Q. NF-kappaB directs dynamic super enhancer formation in inflammation and atherogenesis. Mol Cell. 2014;56:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicodeme E., Jeffrey K.L., Schaefer U. Suppression of inflammation by a synthetic histone mimic. Nature. 2010;468:1119–1123. doi: 10.1038/nature09589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandukwala H.S., Gagnon J., Togher S. Selective inhibition of CD4+ T-cell cytokine production and autoimmunity by BET protein and c-Myc inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14532–14537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212264109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whyte W.A., Orlando D.A., Hnisz D. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell. 2013;153:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loven J., Hoke H.A., Lin C.Y. Selective inhibition of tumor oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell. 2013;153:320–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding N., Hah N., Yu R.T. BRD4 is a novel therapeutic target for liver fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:15713–15718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522163112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou X., Fan L.X., Peters D.J. Therapeutic targeting of BET bromodomain protein, Brd4, delays cyst growth in ADPKD. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:3982–3993. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suarez-Alvarez B., Morgado-Pascual J.L., Rayego-Mateos S. Inhibition of Bromodomain and Extraterminal Domain Family Proteins Ameliorates Experimental Renal Damage. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:504–519. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015080910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou B., Mu J., Gong Y. Brd4 inhibition attenuates unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced fibrosis by blocking TGF-beta-mediated Nox4 expression. Redox Biol. 2017;11:390–402. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang G., Liu R., Zhong Y. Down-regulation of NF-kappaB transcriptional activity in HIV-associated kidney disease by BRD4 inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28840–28851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.359505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong C., Masucci M.V., Zhou X. Pharmacological targeting of BET proteins inhibits renal fibroblast activation and alleviates renal fibrosis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:69291–69308. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholls S.J., Gordon A., Johansson J. Efficacy and safety of a novel oral inducer of apolipoprotein a-I synthesis in statin-treated patients with stable coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1111–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholls S.J., Puri R., Wolski K. Effect of the BET protein inhibitor, RVX-208, on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: results of the phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, ASSURE Trial. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2016;16:55–65. doi: 10.1007/s40256-015-0146-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Bartolo B.A., Scherer D.J., Nicholls S.J. Inducing apolipoprotein A-I synthesis to reduce cardiovascular risk: from ASSERT to SUSTAIN and beyond. Arch Med Sci. 2016;12:1302–1307. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.62906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilham D., Wasiak S., Tsujikawa L.M. RVX-208, a BET-inhibitor for treating atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, raises ApoA-I/HDL and represses pathways that contribute to cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2016;247:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicholls S.J., Gordon A., Johannson J. ApoA-I induction as a potential cardioprotective strategy: rationale for the SUSTAIN and ASSURE studies. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2012;26:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s10557-012-6373-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikolic D., Rizzo M., Mikhailidis D.P. An evaluation of RVX-208 for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2015;24:1389–1398. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2015.1083010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLure K.G., Gesner E.M., Tsujikawa L. RVX-208, an inducer of ApoA-I in humans, is a BET bromodomain antagonist. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Picaud S., Wells C., Felletar I. RVX-208, an inhibitor of BET transcriptional regulators with selectivity for the second bromodomain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:19754–19759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310658110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tyler D.S., Vappiani J., Caneque T. Click chemistry enables preclinical evaluation of targeted epigenetic therapies. Science. 2017;356:1397–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.aal2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jahagirdar R., Zhang H., Azhar S. A novel BET bromodomain inhibitor, RVX-208, shows reduction of atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic ApoE deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2014;236:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wasiak S., Gilham D., Tsujikawa L.M. Downregulation of the complement cascade in vitro, in mice and in patients with cardiovascular disease by the BET protein inhibitor apabetalone (RVX-208) J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2017;10:337–347. doi: 10.1007/s12265-017-9755-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wasiak S., Gilham D., Tsujikawa L.M. Data on gene and protein expression changes induced by apabetalone (RVX-208) in ex vivo treated human whole blood and primary hepatocytes. Data Brief. 2016;8:1280–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2016.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicholls SJ, Ray KK, Johansson J, et al. Selective BET protein inhibition with apabetalone and cardiovascular events: a pooled analysis of trials in patients with coronary artery disease [epub ahead of print]. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs.https://doi.org/10.1007/s40256-017-0250-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Fujisawa T., Filippakopoulos P. Functions of bromodomain-containing proteins and their roles in homeostasis and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:246–262. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Imig J.D., Ryan M.J. Immune and inflammatory role in renal disease. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:957–976. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eddington H., Sinha S., Kalra P.A. Vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease: a clinical review. J Ren Care. 2009;35 Suppl 1:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2009.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathew R.O., Bangalore S., Lavelle M.P. Diagnosis and management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: a review. Kidney Int. 2017;91:797–807. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gold L., Ayers D., Bertino J. Aptamer-based multiplexed proteomic technology for biomarker discovery. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanholder R., Baurmeister U., Brunet P. A bench to bedside view of uremic toxins. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:863–870. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schepky A.G., Bensch K.W., Schulz-Knappe P. Human hemofiltrate as a source of circulating bioactive peptides: determination of amino acids, peptides and proteins. Biomed Chromatogr. 1994;8:90–94. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1130080209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lopez-Giacoman S., Madero M. Biomarkers in chronic kidney disease, from kidney function to kidney damage. World J Nephrol. 2015;4:57–73. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v4.i1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gene Ontology Consortium Gene Ontology Consortium: going forward. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D1049–D1056. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kramer A., Green J., Pollard J., Jr. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:523–530. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stadler K., Goldberg I.J., Susztak K. The evolving understanding of the contribution of lipid metabolism to diabetic kidney disease. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:40. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0611-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rangan G., Wang Y., Harris D. NF-kappaB signalling in chronic kidney disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009;14:3496–3522. doi: 10.2741/3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glorieux G., Mullen W., Duranton F. New insights in molecular mechanisms involved in chronic kidney disease using high-resolution plasma proteome analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:1842–1852. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luczak M., Formanowicz D., Marczak L. Deeper insight into chronic kidney disease-related atherosclerosis: comparative proteomic studies of blood plasma using 2DE and mass spectrometry. J Transl Med. 2015;13:20. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0378-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luczak M., Suszynska-Zajczyk J., Marczak L. Label-free quantitative proteomics reveals differences in molecular mechanism of atherosclerosis related and non-related to chronic kidney disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17050631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carrero J.J., Yilmaz M.I., Lindholm B. Cytokine dysregulation in chronic kidney disease: how can we treat it? Blood Purif. 2008;26:291–299. doi: 10.1159/000126926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hochheiser K., Tittel A., Kurts C. Kidney dendritic cells in acute and chronic renal disease. Int J Exp Pathol. 2011;92:193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2010.00728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y., Gu W., He L. Th1/Th2 cell's function in immune system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;841:45–65. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9487-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lutz M.B. Induction of CD4(+) regulatory and polarized effector/helper T cells by dendritic cells. Immune Netw. 2016;16:13–25. doi: 10.4110/in.2016.16.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gruys E., Toussaint M.J., Niewold T.A. Acute phase reaction and acute phase proteins. J Zhejiang Univ Sci. B. 2005;6:1045–1056. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2005.B1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lutz J., Menke J., Sollinger D. Haemostasis in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:29–40. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tofler G.H., Massaro J., O'Donnell C.J. Plasminogen activator inhibitor and the risk of cardiovascular disease: The Framingham Heart Study. Thromb Res. 2016;140:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kannel W.B. Overview of hemostatic factors involved in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Lipids. 2005;40:1215–1220. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1488-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pawlak K., Ulazka B., Mysliwiec M. Vascular endothelial growth factor and uPA/suPAR system in early and advanced chronic kidney disease patients: a new link between angiogenesis and hyperfibrinolysis? Transl Res. 2012;160:346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zahran M., Nasr F.M., Metwaly A.A. The role of hemostatic factors in atherosclerosis in patients with chronic renal disease. Electron Physician. 2015;7:1270–1276. doi: 10.14661/1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oikonomopoulou K., Ricklin D., Ward P.A. Interactions between coagulation and complement–their role in inflammation. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34:151–165. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0280-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Speidl W.S., Exner M., Amighi J. Complement component C5a predicts future cardiovascular events in patients with advanced atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2294–2299. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Speidl W.S., Exner M., Amighi J. Complement component C5a predicts restenosis after superficial femoral artery balloon angioplasty. J Endovasc Ther. 2007;14:62–69. doi: 10.1583/06-1946.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Speidl W.S., Katsaros K.M., Kastl S.P. Coronary late lumen loss of drug eluting stents is associated with increased serum levels of the complement components C3a and C5a. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208:285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu R., Zhong Y., Li X. Role of transcription factor acetylation in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes. 2014;63:2440–2453. doi: 10.2337/db13-1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ni J., Shen Y., Wang Z. Inhibition of STAT3 acetylation is associated with angiotensin renal fibrosis in the obstructed kidney. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2014;35:1045–1054. doi: 10.1038/aps.2014.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bomsztyk K., Flanagin S., Mar D. Synchronous recruitment of epigenetic modifiers to endotoxin synergistically activated Tnf-alpha gene in acute kidney injury. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Pharmacokinetic assessment of the renal impaired cohort 1 and matched control cohort 2 following a single apabetalone dose (100 mg).

Urine output measured as the fractional excretion (Fe%) of apabetalone for the renal impaired cohort 1 and matched control cohort 2 following a single apabetalone dose (100 mg).

Complete annotated list of 288 proteins enriched in CKD (P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). Baseline comparison of cohort 1 versus cohort 2 (enrichment: red indicates upregulation, blue indicates downregulation), and its statistical significance are shown in columns D, E, and F. References supporting links to renal, cardiovascular or inflammatory diseases and diabetes are listed columns H and I). Plasma proteomic studies that identified protein enrichment in CKD patients are cited (column J).

Uremic toxins enriched in the plasma from CKD cohort relative to the control cohort.

Gene ontology term molecular function analysis of proteins enriched in CKD plasma: complete list of 53.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis disease or functions analysis of proteins enriched in CKD plasma: complete list.

Target engagement time course. Apabetalone (blue circles and line) and LAG3 (orange diamonds and line) serum concentrations measured at discrete time intervals following a single apabetalone dose. Representative data from a single patient.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: dendritic cell maturation. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to apabetalone 12 hourpost single dose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: Th1 signaling. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to single apabetalone 12 hour postdose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: interleukin-6 signaling. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to single apabetalone 12 hour postdose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: acute phase response signaling. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to single apabetalone 12 hour postdose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis canonical pathway analysis: nuclear factor-κb signaling. Predicted signaling in CKD plasma (A). Predicted changes in response to single apabetalone 12 hour postdose (B). Yellow and turquoise: measured upregulation or downregulation in protein abundance. Orange and blue: predicted upregulation or downregulation. Pink outline: proteome data.