Abstract

Introduction

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (corresponding to CKD stage G4+) comprise a minority of the overall CKD population but have the highest risk for adverse outcomes. Many CKD G4+ patients are older with multiple comorbidities, which may distort associations between risk factors and clinical outcomes.

Methods

We undertook a meta-analysis of risk factors for kidney failure treated with kidney replacement therapy (KRT), cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, and death in participants with CKD G4+ from 28 cohorts (n = 185,024) across the world who were part of the CKD Prognosis Consortium.

Results

In the fully adjusted meta-analysis, risk factors associated with KRT were time-varying CVD, male sex, black race, diabetes, lower eGFR, and higher albuminuria and systolic blood pressure. Age was associated with a lower risk of KRT (adjusted hazard ratio: 0.74; 95% confidence interval: 0.69–0.80) overall, and also in the subgroup of individuals younger than 65 years. The risk factors for CVD events included male sex, history of CVD, diabetes, lower eGFR, higher albuminuria, and the onset of KRT. Systolic blood pressure showed a U-shaped association with CVD events. Risk factors for mortality were similar to those for CVD events but also included smoking. Most risk factors had qualitatively consistent associations across cohorts.

Conclusion

Traditional CVD risk factors are of prognostic value in individuals with an eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, although the risk estimates vary for kidney and CVD outcomes. These results should encourage interventional studies on correcting risk factors in this high-risk population.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, risk factors

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has a major impact on the affected individuals’ lives and carries an economic burden to societies.1 The prevalence of CKD Stage G3+ (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) varies substantially across the world; in the United States, between 4.8% and 11.8,2 in China, between 1.1% and 3.8%,3 and in Europe, between 1.0% and 5.9%.4 Globally, the prevalence of CKD with severely decreased GFR (G4+, eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2) is much lower (<0.5%); however, associated morbidity and mortality are higher among patients with CKD G4+,5 and less is known about relevant risk factors.

Patients with CKD have an elevated risk of progressing to kidney failure requiring kidney replacement therapy (KRT), cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, and mortality, with higher risk at higher CKD stage.6, 7 Traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as older age and male sex, are associated with CVD and mortality in CKD stage G3+.8 In addition, lower eGFR and higher albuminuria are important risk factors for progression to KRT and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.7 However, risk factors for KRT, CVD events, and mortality may not be the same in a population that has already progressed to CKD G4+. For example, some believe that high blood pressure may be less of a risk factor in CKD with severely decreased GFR. In addition, it is not known whether risk factors vary by age, which is a characteristic of particular interest, given that most patients with CKD G4+ are older than 65 years.9 A better understanding of factors associated with different outcomes may inform treatment strategies.

Using 28 cohorts from across the world, we investigated the relative risk associations between traditional risk factors and adverse outcomes in CKD G4+. We hypothesized that traditional risk factors would be important in CKD G4+ and that older age would not significantly modify the relationship between risk factors and outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This study followed a call for participation in the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes controversies conference in Barcelona (December 2016) for evaluation and management of CKD with severely decreased GFR. Study cohorts were part of the Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium, a worldwide, collaborative network consisting of CKD cohorts with information on eGFR and albuminuria.10, 11 The underlying selection criteria are provided in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Appendix S1 and Supplementary Table S1). For this specific project, 28 cohorts were selected, with inclusion criteria consisting of at least 500 individuals older than 18 years with an eGFR ≤30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (CKD Stage G4+) at any visit. Furthermore, the cohorts had to have follow-up for both KRT and death before and after KRT and at least 50 events of each outcome. Time at risk began at the first visit in which eGFR was observed to be <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Study Variables

The study variables are listed in Table 1. eGFR was estimated by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation using age, sex, race, and serum creatinine standardized according to isotope dilution mass spectrometry traceable methods.12 For cohorts in which serum creatinine was not standardized, we reduced the serum creatinine by 5%.13 Albuminuria was recorded as the urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) or protein/creatinine ratio and converted to ACR as done previously.14 If these measurements were not available, we used dipstick proteinuria information. Diabetes mellitus was defined as the use of glucose-lowering drugs, a fasting glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l or nonfasting glucose ≥11.1 mmol/l, hemoglobin A1c ≥6.5%, or self-reported diabetes. Smoking status was recoded as current smoking versus not smoking. History of CVD was defined as a previous diagnosis of myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, bypass grafting, heart failure, or stroke.

Table 1.

Participating studies and baseline characteristics

| Study | n | Death (pre/post-KRT) | ESRD | CVD (pre/post-KRT) | Follow-up, yr (SD) | Age, yr (SD) | SBP, mm Hg (SD) | eGFR (SD) | ACR, mg/g (IQR) | % Male | % Black | % History of CVD | % Diabetes | % Smoker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AASK (USA) | 622 | 135 (85/50) | 286 | 38 (38/0) | 4 (3) | 56 (12) | 135 (21) | 25 (4) | 130 (34, 488) | 60 | 100 | 53 | 1 | 29 |

| BC CKD (Canada) | 9672 | 4717 (3305/1412) | 3036 | 5 (3) | 71 (13) | 137 (23) | 24 (5) | 225 (42, 1233) | 55 | 0.41 | 16 | 50 | 11 | |

| CanPREDDICT (Canada) | 1739 | 452 (322/130) | 435 | 334 (286/48) | 3 (2) | 69 (13) | 134 (20) | 23 (5) | 188 (37, 929) | 62 | 1.6 | 38 | 52 | |

| CCF (USA) | 9256 | 3000 (2640/360) | 1115 | 2 (1) | 73 (13) | 130 (22) | 24 (5) | 51 (13, 346) | 46 | 17 | 24 | 30 | 9 | |

| CRIB (UK) | 315 | 133 (62/71) | 185 | 6 (3) | 62 (14) | 152 (23) | 18 (7) | 589 (118, 1345) | 61 | 5.1 | 45 | 17 | 12 | |

| CRIC (USA) | 1764 | 473 (235/238) | 834 | 475 (346/129) | 5 (3) | 60 (11) | 131 (24) | 25 (4) | 267 (48, 1066) | 54 | 45 | 45 | 60 | 14 |

| CRISIS (UK) | 1717 | 710 (553/157) | 461 | 3 (3) | 66 (14) | 140 (22) | 20 (6) | 150 (55, 466) | 62 | 0.64 | 48 | 36 | 14 | |

| GCKD (Germany) | 504 | 34 (30/4) | 33 | 34 (32/2) | 2 (0) | 64 (11) | 140 (22) | 26 (4) | 130 (23, 877) | 61 | 0 | 43 | 44 | 15 |

| Geisinger (USA) | 19293 | 10039 (8953/1086) | 1802 | 6292 (5822/470) | 4 (4) | 73 (14) | 127 (22) | 24 (5) | 48 (15, 232) | 41 | 0.99 | 56 | 43 | 6 |

| GLOMMS2 (UK) | 6384 | 3283 (3175/108) | 265 | 3 (2) | 79 (11) | 25 (5) | 44 (10, 189) | 38 | 0 | 26 | 12 | 1 | ||

| Gonryo (Japan) | 729 | 57 (57/0) | 354 | 48 (43/5) | 2 (2) | 67 (13) | 135 (17) | 19 (7) | 666 (318, 1401) | 59 | 0 | 27 | 38 | |

| Hong Kong CKD groups | 502 | 191 (113/78) | 270 | 6 (3) | 61 (12) | 138 (19) | 17 (7) | 60 (21, 150) | 56 | 0 | 27 | 46 | 11 | |

| Maccabi (Israel) | 12576 | 7531 (6800/731) | 1693 | 3480 (3338/142) | 4 (3) | 76 (13) | 135 (22) | 25 (5) | 70 (10, 301) | 49 | 0 | 64 | 46 | |

| MASTERPLAN (Netherlands) | 437 | 93 (58/35) | 142 | 32 (30/2) | 4 (1) | 61 (12) | 138 (22) | 24 (5) | 185 (53, 666) | 69 | 0 | 32 | 32 | 18 |

| MDRD (USA) | 851 | 474 (81/393) | 724 | 14 (7) | 51 (13) | 134 (19) | 22 (6) | 335 (64, 1002) | 60 | 10 | 17 | 9 | 12 | |

| Nanjing CKD (China) | 1584 | 116 (21/95) | 1003 | 108 (44/64) | 4 (3) | 47 (14) | 141 (22) | 21 (6) | 1008 (550, 1839) | 54 | 0 | 12 | 21 | 0.40 |

| NephroTest (France) | 740 | 213 (100/113) | 372 | 6 (4) | 61 (14) | 139 (22) | 22 (6) | 277 (69, 820) | 67 | 11 | 24 | 36 | 14 | |

| NRHP-URU (Uruguay) | 2090 | 658 (505/153) | 512 | 385 (379/6) | 3 (2) | 72 (13) | 135 (22) | 21 (5) | 83 (0, 655) | 49 | 0.14 | 36 | 32 | 6 |

| NZDCS (New Zealand) | 1372 | 919 (576/343) | 438 | 620 (545/75) | 6 (3) | 71 (12) | 138 (21) | 23 (6) | 13 (2, 93) | 43 | 0.073 | 47 | 100 | 9 |

| PSP CKD (UK) | 3522 | 1251 (1224/27) | 141 | 688 (675/13) | 2 (1) | 80 (12) | 131 (19) | 24 (5) | 48 (18, 151) | 43 | 0.51 | 47 | 30 | 8 |

| PSPA (France) | 573 | 437 (238/199) | 294 | 3 (2) | 82 (5) | 145 (22) | 13 (4) | 463 (174, 1015) | 57 | 0 | 55 | 39 | ||

| RCAV (USA) | 78114 | 30012 (28,014/1998) | 4148 | 21672 (21,063/609) | 3 (2) | 69 (11) | 125 (24) | 24 (5) | 38 (10, 220) | 97 | 22 | 61 | 58 | |

| RENAAL (Multia) | 1078 | 234 (138/96) | 327 | 400 (356/44) | 3 (1) | 60 (7) | 151 (21) | 26 (3) | 1604 (690, 3133) | 59 | 13 | 28 | 100 | 17 |

| SCREAM (Sweden) | 18486 | 12370 (11,841/529) | 1132 | 7882 (7709/165) | 3 (2) | 70 (12) | 25 (5) | 112 (27, 787) | 45 | 0 | 54 | 25 | ||

| SMART (Netherlands) | 137 | 79 (55/24) | 31 | 29 (23/6) | 6 (4) | 65 (11) | 152 (25) | 21 (8) | 187 (47, 523) | 70 | 0 | 52 | 29 | 27 |

| SRR CKD (Sweden) | 2555 | 778 (532/246) | 770 | 912 (807/105) | 3 (2) | 69 (14) | 142 (23) | 21 (6) | 211 (43, 953) | 66 | 0 | 33 | 38 | |

| Sunnybrook (Canada) | 1592 | 636 (457/179) | 362 | 533 (438/95) | 3 (2) | 72 (14) | 136 (22) | 23 (6) | 236 (62, 807) | 54 | 0 | 17 | 41 | 8 |

| West of Scotland CKD (UK) | 6820 | 2954 (2505/449) | 1136 | 419 (304/115) | 5 (3) | 68 (13) | 143 (24) | 24 (6) | 151 (34, 800) | 49 | 0.088 | 25 | 21 | |

| Total | 185,024 | 81,979 | 22,301 | 44,401 |

ACR, albumin creatine ratio; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IQR, interquartile range; KRT, kidney failure treated with kidney replacement therapy; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

All values are expressed as numbers unless other is indicated; eGFR presented as Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation in ml/min per 1.73 m2. The selection criteria and extended information about each cohort are given in Supplementary Appendix S1 and Supplementary Table S1. Study acronyms or abbreviations are listed in Supplementary Appendix S2.

RENAAL contains participants from 28 countries: Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Peru, Portugal, Russia, Singapore, Spain, Slovakia, United Kingdom, United States, and Venezuela.

There were 3 major outcomes: kidney failure treated with KRT, CVD event, and death. We also studied recurrent hospitalization events as a secondary outcome. The KRT outcome was defined as start of KRT and either actively ascertained or ascertained through linkages to registries or International Classification of Diseases codes (Supplementary Appendix S1). As for the CVD event, we accepted both fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart failure events occurring after enrollment in our cohort (Supplementary Appendix S1). If fatal events were lacking, we did include nonfatal events. Note that any CVD event could occur also in individuals with a history of CVD at baseline, but only the first event after enrollment was quantified. Death was treated as a censoring event for both KRT and CVD.

Statistical Analysis

Because the focus of our analysis was the risk relationship rather than the absolute risk of events, we used Cox proportional hazards regression instead of competing risk models. For the purpose of analyses, age was expressed per 10 years older, and eGFR per 5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 lower. Albuminuria from the heterogeneous sources was referred to as urine ACR and log-transformed and scaled such that the coefficients reflect a twofold increase in ACR. Systolic blood pressure was modeled as a linear spline with a knot at 140 mm Hg, based on review of the literature and exploratory data analysis in in-house cohorts, and expressed per 20 mm Hg higher value. Race, sex, diabetes, smoking, and history of CVD were dichotomized. In addition to serving as an outcome in some of the analyses, KRT and CVD also were modeled as time-varying variables during follow-up for analyses of the CVD and KRT, respectively, as well as for mortality for both. For analyses of hospitalizations, recurrent events were counted during follow-up. We started by analyzing the risk relationships in each cohort individually by time-varying Cox proportional hazards models. For analyses of KRT and CVD as outcomes, death was treated as a censoring event. For hospitalization, we used negative binomial regression. Multiple imputation was used for any missing data except for demographic variables (age, sex, race), eGFR, and outcomes. Meta-analyses were conducted separately for studies with information on all 3 outcomes and those with information on only KRT and death. Adjusted risk ratios were pooled through meta-analysis using the random effects model.15 The random effects meta-analysis assumes that the observed estimates may vary across cohorts because of a real difference in effect of the variables in each study, but also because of chance. This type of analysis uses a more conservative approach, downplays larger studies, and produces confidence intervals that are generally larger than the corresponding fixed effects. Between-study heterogeneity was quantified by the I2 statistic, but also assessed through visual inspection of the individual coefficients and their corresponding 95% intervals.16, 17 All analyses were re-run stratified by age younger than or older than 65 years. Meta-regressions were performed to explain any underlying heterogeneity of the risk factors, with investigated explanatory variables, including region, cohort type, average cohort eGFR, average cohort ACR, proportion missing ACR, average cohort age, median follow-up time, average systolic blood pressure, and proportion of the cohort that were men, had diabetes, a history of CVD, and were current smokers. All analyses were done in Stata 14 MP (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Study Characteristics

There were 28 cohorts included in this study, with 185,024 participants with eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 from 30 different countries. There were 19 cohorts that had information on all 3 of the outcomes of interest (KRT, CVD events, and death), and 9 cohorts that had information only on KRT and death. The characteristics of all 28 cohorts are presented in Table 1. Overall, average age was 70 years (SD 13), 69% were men, 11% were black, 5.4% were Asian, 46% had diabetes, and 50% had a history of CVD. The mean eGFR was 24 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (SD 6) and median urine ACR was 48 mg/g (interquartile range, 38–112). Inclusion criteria and extended description of the participating cohorts, covariates, and outcomes are found in Supplementary Appendix S1 and Supplementary Table S1. Mean follow-up for the 28 cohorts was 3.3 years (SD 2.8).

Risk Factors for Kidney Failure Requiring KRT After eGFR 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2

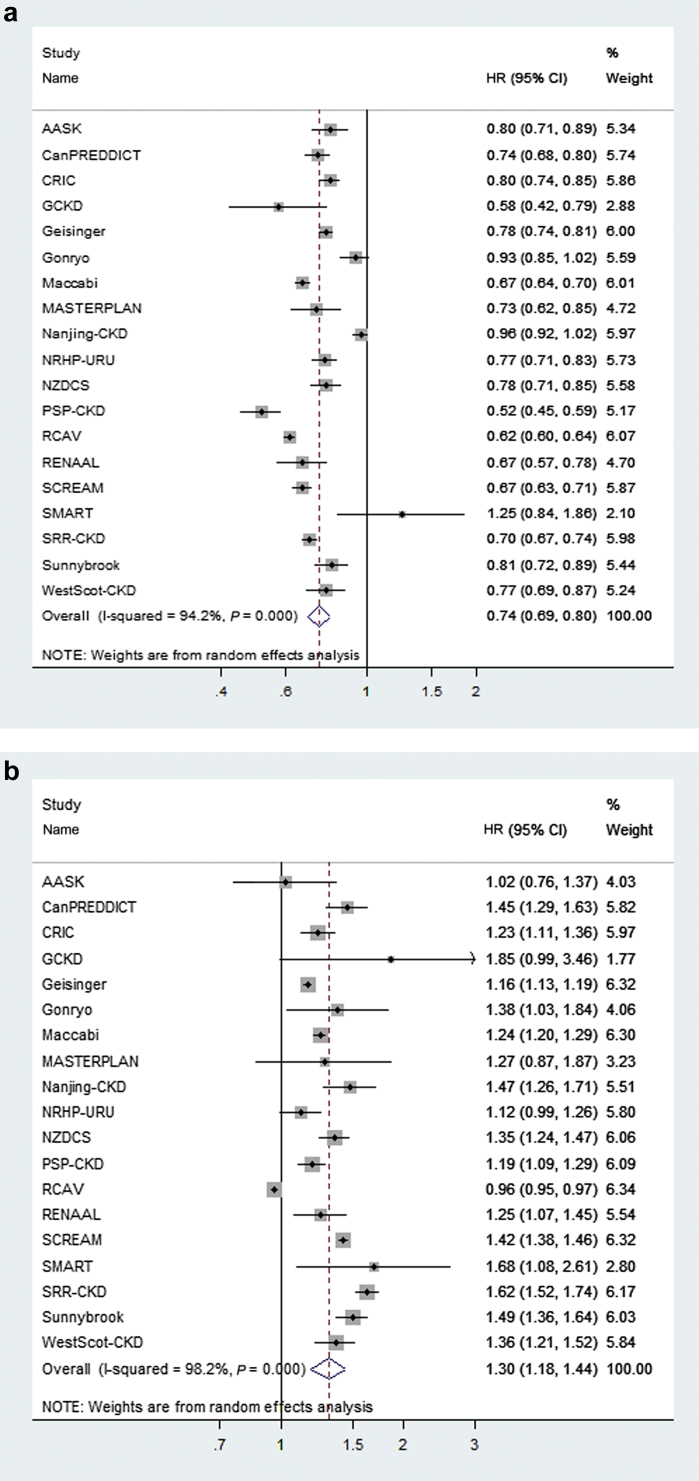

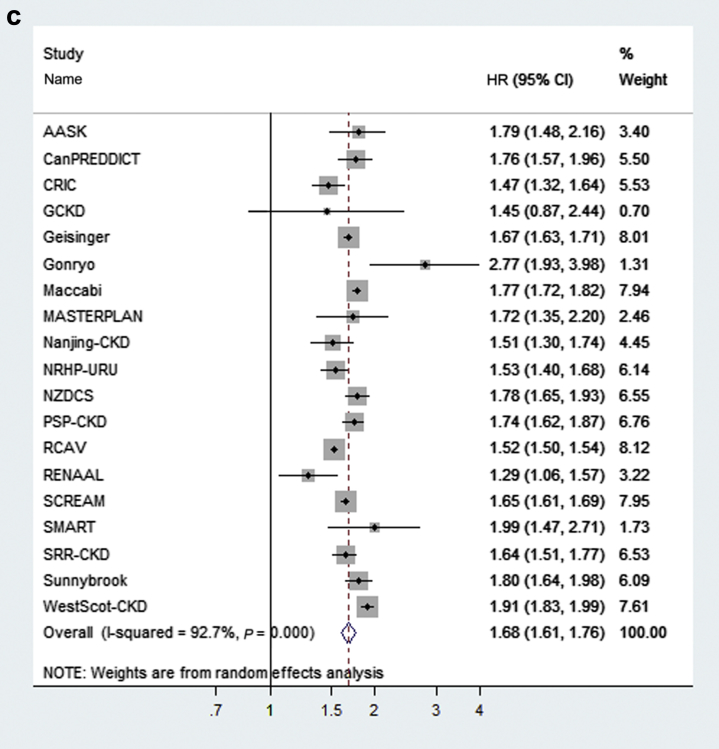

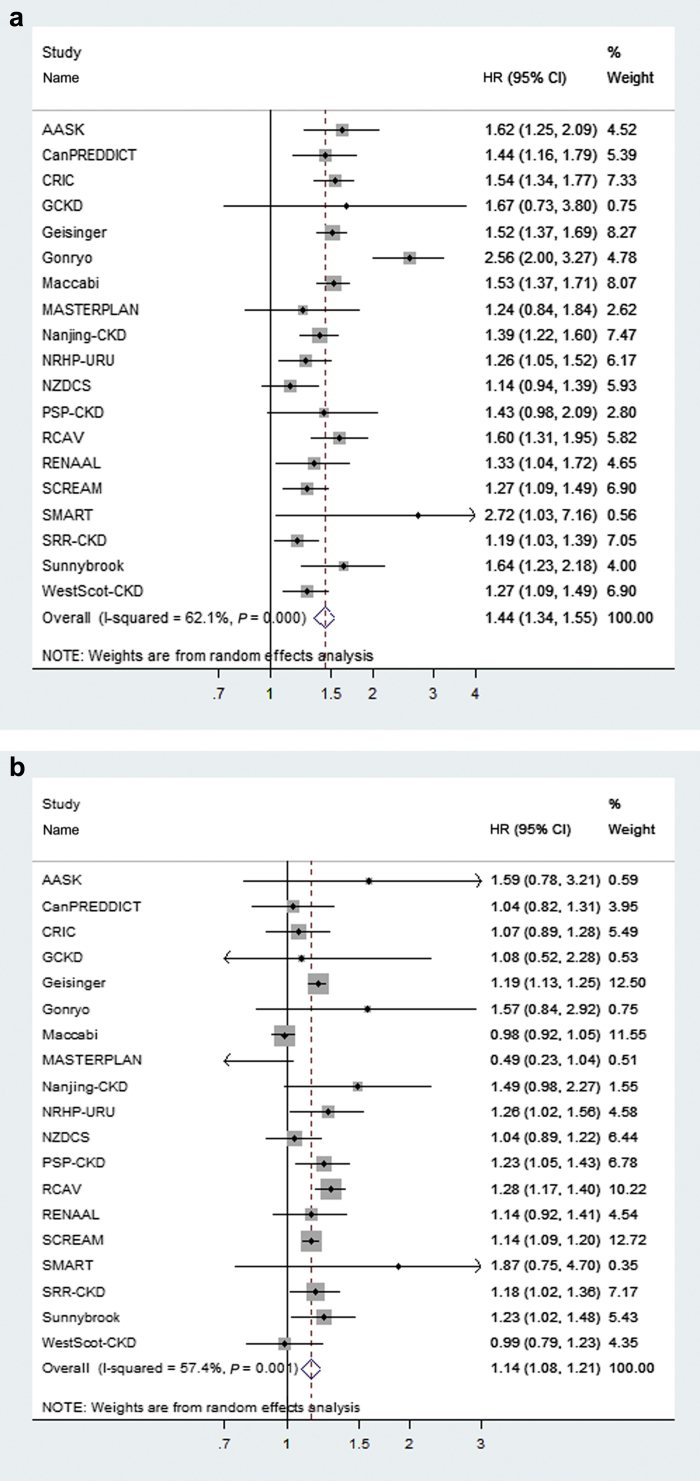

The unadjusted incidence rates for KRT ranged from 17 to 302 events per 1000 person-years between the different cohorts (Supplementary Table S2). In total, there were 22,301 (12.1%) KRT events among 185,024 people. The meta-analyzed adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the relationship between risk factors and onset of KRT in the 19 cohorts with outcome information on KRT, CVD events, and death are presented in Table 2, column 2. The risk factors most strongly associated with KRT were male sex (HR: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.34–1.55), black race (HR: 1.49; 95% CI: 1.29–1.72), lower eGFR (HR: 1.73 per 5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 lower; 95% CI: 1.58–1.90), higher urine ACR (HR: 1.26 per twofold higher; 95% CI: 1.21–1.31), and the occurrence of a CVD event during follow-up (HR: 2.28; 95% CI: 2.02–2.57). Older age was associated with a lower risk of KRT (HR per 10 years older: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.69–0.80). The direction and size of the age association was qualitatively consistent across most cohorts (Figure 1a). Men had higher risk of KRT in all the participating 19 cohorts, although the point estimate varied to some degree (Figure 2a). The relationship between the presence of diabetes and KRT (excluding 3 cohorts that did not include persons with and without diabetes mellitus) was slightly weaker (HR: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.14–1.47), with diabetes observed as an independent, statistically significant risk factor in only 8 of 16 cohorts (Supplementary Figure S1a). In meta-regression analyses, the heterogeneity in the association between diabetes and KRT was mainly explained by differences in cohorts with respect to urine ACR, with a stronger effect size in cohorts with less albuminuria testing and lower ACR levels, as well as to a lesser extent by differences in age, systolic blood pressure, and history of CVD between the different cohorts (Supplementary Figure S2). In sensitivity analysis, we compared risk coefficients from the meta-analysis when the analyses were extended to the full 28 cohorts with information on KRT and death; results were similar (Supplementary Table S3, column 2 vs. Table 2, column 2).

Table 2.

Meta-analyzed HRs of risk factors associated with KRT, CVD, and death in the 19 cohorts

| Variables | HR (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| KRT | CVD | Death | |

| Age, 10 yr | 0.74 (0.69–0.80) | 1.30 (1.18–1.44) | 1.68 (1.61–1.76) |

| Male sex | 1.44 (1.34–1.55) | 1.14 (1.08–1.21) | 1.14 (1.08–1.21) |

| Black | 1.49 (1.29–1.72) | 1.02 (0.85–1.23) | 0.93 (0.82–1.05) |

| History of CVD | 0.91 (0.82–1.02) | 2.57 (2.27–2.92) | 1.27 (1.18–1.36) |

| Smoker | 1.02 (0.93–1.11) | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 1.37 (1.25–1.50) |

| SBP <140, 20 mm Hg | 1.25 (1.10–1.41) | 0.90 (0.85–0.95) | 0.84 (0.81–0.88) |

| SBP ≥140, 20 mm Hg | 1.17 (1.10–1.24) | 1.09 (1.04–1.15) | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.30 (1.14–1.47) | 1.41 (1.30–1.53) | 1.12 (1.03–1.22) |

| eGFR, −5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 1.73 (1.58–1.90) | 1.07 (1.05–1.10) | 1.12 (1.09–1.15) |

| ACR, twofold increase | 1.26 (1.21–1.31) | 1.05 (1.04–1.07) | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) |

| Time-varying CVD | 2.28 (2.02–2.57) | 2.87 (2.57–3.20) | |

| Time-varying KRT | 1.39 (1.15–1.68) | 2.07 (1.80–2.38) | |

ACR, albumin to creatinine ratio; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; KRT, kidney failure treated with kidney replacement therapy; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

All values are expressed as pooled HRs with 95% CIs. The HR for age is expressed for every 10-year increase in age at baseline, the HR for ACR is expressed per twofold increase in mg/g, the HR for eGFR is expressed for every 5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 decrease, the HR for SBP is expressed as per 20 mm Hg increase in blood pressure above and below 140 mm Hg. The 3 cohorts that did not include persons with and without diabetes mellitus did not contribute to the meta-analyzed hazard ratio for diabetes mellitus.

Bold values indicate statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Variation of the age coefficient for kidney failure treated with kidney replacement therapy (a), cardiovascular disease (b), and death (c) across 19 cohorts in the main analysis. The individual and average hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from the adjusted Cox regression model and expressed per 10-year higher age. Weights are from the random effects analysis. Heterogeneity between cohorts is assessed by I2. Study acronyms or abbreviations are listed in Supplementary Appendix S2. HR, hazard ratio. (Continued)

Figure 2.

Variation of the sex coefficient (male vs. female) for kidney failure treated with kidney replacement therapy (a), cardiovascular disease (b), and death (c) across 19 cohorts in the main analysis. The individual and average hazard ratios and 95% confidence interval (CI) from the adjusted Cox regression model. Weights are from the random effects analysis. Heterogeneity between cohorts is assessed by I2. Study acronyms or abbreviations are listed in Supplementary Appendix S2. HR, hazard ratio. (Continued)

Risk Factors for CVD Events After eGFR 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2

The unadjusted incidence rate of a CVD event was highly variable between the cohorts, both before and after KRT. In total, there were 44,401 (28.6%) CVD events that occurred among 155,014 people. In the fully adjusted model, the onset of KRT was among the most important risk factors for a subsequent CVD event (HR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.15–1.68) (Table 2, column 3). Other important risk factors for a CVD event included a history of CVD and the presence of diabetes, as well as older age, male sex, higher ACR, and lower eGFR. Systolic blood pressure showed a U-shaped association with CVD event risk. Each 20 mm Hg higher blood pressure above 140 mm Hg was associated with a 9% higher risk of CVD events, whereas a systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg relative to 120 mm Hg was associated with an 11% lower risk of a CVD event. The association between age and CVD was consistent in direction across all cohorts but one (Figure 1b). Associations between sex and CVD events were also relatively similar across cohorts (Figure 2b), and meta-regression analyses did not identify any cohort-level factors that explained underlying heterogeneity (Supplementary Figure S3). The presence of diabetes was a strong risk factor for CVD in all cohorts but one (Supplementary Figure S1b).

Risk Factors for Mortality After eGFR 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2

In total, there were 81,979 (44.3%) deaths among 185,024 people during follow-up. In the 19 cohorts with all outcomes present, the development of a CVD event and the onset of KRT were both exceedingly strong risk factors for subsequent death (Table 2, column 4). Other risk factors for mortality included lower eGFR and higher urine ACR, as well as older age, male sex, history of previous CVD, and the presence of diabetes. Similar to its association with CVD events, systolic blood pressure was associated with death in a nonlinear fashion with lower blood pressure below 140 mm Hg being associated with death, and no association for higher blood pressure with death above 140 mm Hg. Smoking was significantly associated with death (HR: 1.37; 95% CI: 1.25–1.50). The association between age and mortality was qualitatively similar across cohorts (Figure 1c). The associations of male sex and diabetes with mortality were weaker and not always consistent in direction across cohorts and showed more heterogeneity between the different cohorts (Figure 2c and Supplementary Figure S1c). Meta-regression of the association between male sex and mortality as well as diabetes and mortality did not show any particular cohort-level factor that explained the variation (Supplementary Figures S4 and S5). The relationship between the risk factors and mortality remained similar in the analysis with all 28 cohorts included (Supplementary Table S3, column 3 vs. Table 2, column 4).

Risk Factors for Hospitalization

Out of the 8 cohorts with information on hospitalization rates, the unadjusted incidence of recurrent hospitalization ranged from 12 to 1524 per 1000 person-years pre-onset of kidney failure treated with KRT, and 26 to 2293 hospitalizations per 1000 person-years after KRT (Supplementary Table S4). In all cohorts, hospitalization rates were higher after KRT was initiated. Risk factors for recurrent hospitalizations included history of CVD, lower systolic blood pressure below 140 mm Hg and higher systolic blood pressure above 140 mm Hg, higher urine ACR, and lower eGFR; history of CVD and higher systolic blood pressure above 140 mm Hg also were risk factors post-KRT of similar magnitude both before and after KRT (Supplementary Table S5).

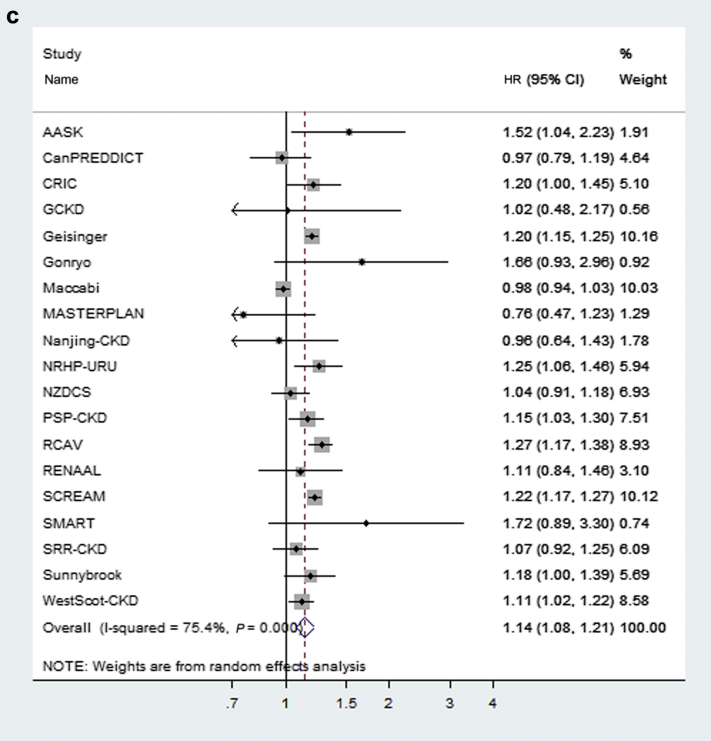

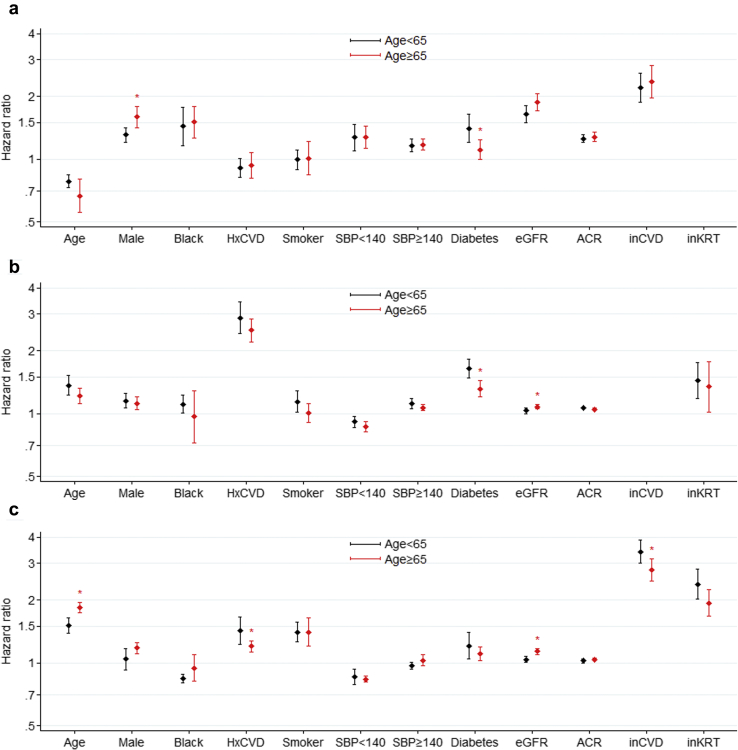

Effect Modification of Risk Factors by Age

In general, the associations between risk factors and outcomes (KRT, CVD event, and death) were similar in subgroups of participants with an age younger than or older than 65 years (Figure 3); however, for both KRT and CVD events, diabetes was a slightly stronger risk factor in the younger subgroup. In contrast, male sex was a stronger risk factor for KRT in those older than 65 years. Notably, age demonstrated significant associations with each outcome within both age strata. For example, older age was associated with a lower risk of KRT even among those with an age younger than 65 years.

Figure 3.

Risk factor modification by age for kidney failure treated with kidney replacement therapy (KRT) (a), cardiovascular disease (CVD) (b), and death (c). All values are expressed as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals unless other is indicated. The HR for age is expressed for every 10-year increase in age at baseline, the HR for albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) is expressed per twofold increase in mg/g, the HR for estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is expressed for every 5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 decrease, and the HR for systolic blood pressure (SBP) is expressed as per 20 mm Hg increase in blood pressure above and below 140 mm Hg. HxCVD, history of CVD; inCVD, a CVD event after study inclusion; inKRT, incident KRT.

Discussion

In this large meta-analysis, we studied risk factors for KRT, CVD, and death in 185,244 people with stages 4–5 CKD. Traditional risk factors were of important prognostic value in this population, although associations varied by outcome of interest. Overall, the greatest explained variation was observed for KRT, mostly due to very strong risk relationships among eGFR, albuminuria, and KRT. Lower eGFR and higher albuminuria were slightly weaker risk factors for CVD and mortality. Male sex, black race, presence of diabetes, and higher systolic blood pressure all increased the risk of KRT, whereas older age was associated with a lower risk of KRT. The risk factors for CVD and mortality were similar to those for KRT, although older age also was a risk factor and there was a nonlinear association with systolic blood pressure. Smoking was significantly associated only with mortality. Importantly, we found that the onset of KRT or a CVD event in individuals with an eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was strongly associated with subsequent mortality. Risk factor associations were fairly consistent across 28 cohorts as well as subgroups of age.

Although nephrologists know that those with severely decreased GFR represent a high-risk population for adverse outcomes, it has been difficult to assess the benefits of risk factor modification at this stage. The presence of multiple comorbidities in this population may distort relationships between risk factors such as hypertension and clinical outcomes.18 Most previous studies examining risk factors for CKD outcomes have recruited patients with a wide spectrum of kidney function,7, 8, 19, 20 and patients who survive to develop CKD stage G4+ may experience different risk associations when compared with those who never progress. Yet, studies in CKD stage G4+ are limited because of the relative rarity of disease and paucity of CKD stage G4+ disease registries. The results of our large, consortium-wide analysis including 185,244 individuals are consistent with the existing literature evaluating traditional risk factors in much smaller, local cohorts of patients with severely decreased GFR.21, 22, 23

Age was one variable that showed differences in the direction of associations with different outcomes. The protective association between older age and KRT has been shown in some21, 22, 24 but not all25 previous studies. In our study, the age coefficient was consistently “protective” for the development of KRT across cohorts, as well as within subgroups of older and younger age. On the other hand, older age was a risk factor for CVD and death, as would be expected. The apparent protective effect of age may be attributable to the competing event of death, but it also may be related to the rapidity of eGFR decline26 and the fact that starting KRT is a treatment option influenced by patient choice. Older adults may be more likely to choose conservative care or have negative attitudes toward dialysis treatment.27 Alternatively, age may influence the timing of dialysis.28

Besides age, other demographic risk factors also were associated with adverse outcomes. Male sex was a risk factor for KRT, CVD events, and death in CKD stage G4+, similar to findings in the general population. Indeed, in contrast to reports that women have a higher prevalence of CKD stage G3,5 in our study population of CKD stage G4+, men were in the majority. Mechanisms for a more rapid GFR decline in men could be related to underlying differences in glomerular hemodynamics, activity of local cytokines, or mediated by effects of sex hormones.29, 30, 31 Other reasons for the lower KRT incidence among women also are possible, such as later initiation of KRT,32 lower awareness,33 and lower rates of referral to nephrology care.5 Black race was a risk factor for KRT, but not CVD events or death. This finding is consistent with previous work showing that African American individuals have between 2 and 4 times higher incidence of KRT than people of other races and a higher odds of severely decreased GFR as compared with whites.34, 35 Some of the risk for CKD progression may be attributable to the presence of Apolipoprotein-1 risk variants36 or sickle cell trait (inheritance of a single copy of the sickle mutation), both of which occur more often in people with African ancestry.37

Traditional cardiovascular risk factors have been found to increase the risk of new-onset CKD.38 In our analysis, the occurrence of a new CVD event during follow-up was associated with a more than twofold increase in the risk of KRT. Similarly, after the initiation of KRT, the risk of both CVD events and death increased considerably. These results suggest that those who have a very high risk of CVD are likely to be the same individuals who also progress to require KRT and who are more likely to die.

Diabetes is an established risk factor for KRT, CVD, and all-cause mortality in the general population.39, 40 In the kidney failure risk equation, a KRT prediction tool for people with CKD stage G3 to G5, diabetes was not a significant risk factor once albuminuria had been taken into account.8, 41 In contrast, our analysis found diabetes to be an independent risk factor for KRT in patients with CKD stage G4+. One reason for this difference could be that many of the participants in our study lacked ACR measurements. Although we used imputation to estimate ACR levels, we found that the effect of diabetes was stronger in cohorts with more missing ACR and lower ACR measurements: 2 correlated factors at the cohort level and more indicative of an administrative cohort setting. Nonproteinuric CKD in the context of type 2 diabetes is a recognized risk factor for KRT, although the mechanisms of progressive kidney damage may be different when compared with patients who have albuminuria.42 Albuminuria itself remained an independent risk factor for all outcomes studied in this meta-analysis. Increases in albuminuria were recently shown to be associated with both the future initiation of KRT and mortality, whereas decreases were inversely correlated with KRT.43

Smoking has been linked to new-onset CKD and KRT in the general population.34, 44 Our results are consistent with the recently published Study of Heart And Renal Protection subanalysis, which showed that cigarette smoking was associated with risk of death, but not KRT in people with CKD G3+.45 Thus, even though the risk for KRT associated with smoking may change over the course of the disease, the elevated risk for death remains, reinforcing the importance of offering smoking cessation advice to people with severely decreased GFR. Elevated systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg has been demonstrated to be a risk factor for CVD and also has been associated with progression to KRT in CKD stage G3+ (eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2).46 Our results show an independent association between systolic blood pressure and KRT after adjusting for albuminuria in people with more severely decreased GFR. This may indicate that achieving blood pressure targets is important also at later CKD stages. For CVD events and death, we observed a U-shaped risk association with higher risks both below 120 mm Hg and above 140 mm Hg. These results could be regarded as contradictive of some recent reports, suggesting better outcomes with intense blood pressure–lowering medication.47 However, a more likely explanation is that our risk association for a low systolic blood pressure was confounded by comorbid factors; for example, patients with severe heart failure often having low, rather than high blood pressure.18 We did not include body mass index and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in our analyses. For LDL in particular, there were many cohorts with missing information. Initial analyses of the data available indicated only weak relationships for both body mass index and LDL.

This is the largest analysis of risk factors for adverse outcomes in people with severely decreased GFR conducted so far, and complements projections of the probability and timing of events.48 We have included studies from many different regions of the world and, by doing so, have increased the generalizability of our results. There has been a concern that people progressing to later CKD stages have a different risk profile compared with people earlier in the course of the disease. By focusing on this specific group, we have found that many of the traditional risk factors remain predictive, but that some risk factors, like age, behave differently for the different outcomes. One limitation of our analysis is that the selection of study participants differed among the individual cohorts; some research cohorts have specific inclusion and exclusion criteria (and 2 cohorts included only individuals with diabetes), whereas the large administrative databases do not. This may have affected the representativeness of study participants. In addition, in most cohorts, only a subset of the participants was selected (i.e., those with eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2), a process designed to capture both people with prevalent disease as well as “progressors.” However, although the studies differed substantially in selection criteria and recruitment, the consistency in qualitative size and direction of our risk estimates throughout the different cohorts were reassuring. Other limitations included lack of data on LDL cholesterol in most cohorts. Although in preliminary analyses, LDL cholesterol was not a strong risk factor for any of the events of interest, the lack of association may be driven by survival bias and confounding by nutritional status. Lack of time-updated measurements prohibited us from analyzing any change in the direction of the risk factors closer to initiation of dialysis.

In summary, this large meta-analysis of people with severely decreased GFR shows that traditional risk factors, such as male sex, black race, diabetes, lower eGFR, higher albuminuria, smoking, and higher systolic blood pressure, remain important in CKD stage G4+. Furthermore, patients with CKD with severely decreased GFR who develop either CVD events or KRT have an even higher risk of mortality. These results should encourage health care professionals to assess traditional risk factors in individuals with stages 4 to 5 CKD and to offer interventions to reduce exposure to those that are modifiable. Future studies assessing the clinical benefits of such interventions should include this high-risk population.

Disclosure

NJB received grant support from Baxter Healthcare. ME received grant support from the Stockholm County Council (award number 20130605 from 2014–2017). PBM received consulting fees from Astellas and Novartis, lecture fees from Eli-Lilly and Janssen, and grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim. KM received consulting fees from Kyowa Hakko Kirin, lecture fees from Kyowa Hakko Kirin and Daiichi Sankyo, travel support from Kyowa Hakko Kirin, and grant support from Kyowa Hakko Kirin. OM received lecture fees from Baxter Fresenius Roche, travel support from Sanofi Roche, and grant support from SFNDT Agence de Biomedecine Roche Fresenius Baxter Roche. PRao received grant support from NIDDK (U01-DK-061028-16-S1). VS received grant support from the Israeli Ministry of the Environment. DCW received lecture fees from Amgen, Janssen, and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma; travel support from Amgen; and grant support from Kidney Research UK and Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Foundation. The Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium Data Coordinating Center is funded in part by a program grant from the US National Kidney Foundation, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Foundation, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK100446-01). A variety of sources have supported enrollment and data collection, including laboratory measurements, and follow-up in the collaborating cohorts of the Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium. These funding sources include government agencies, such as national institutes of health and medical research councils, as well as foundations and industry sponsors listed in Supplementary Appendix S3. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Some of the data reported here have been supplied by the US Renal Data System. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Footnotes

Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium investigators/collaborators (study acronyms/abbreviations are listed in Appendix S2).

Appendix S1. Data analysis overview and analytic notes for some individual studies.

Appendix S2. Acronyms or abbreviations for studies included in the current report and their key references linked to the Web references.

Appendix S3. Acknowledgments and funding for collaborating cohorts.

Table S1. Underlying data selection by cohort.

Table S2. Unadjusted incidence rates for KRT by participating cohort.

Table S3. Meta-analyzed hazard ratios of risk factors associated with KRT and mortality in all 28 cohorts.

Table S4. Unadjusted incidence rate of hospitalizations pre- and post-KRT by participating cohort.

Table S5. Meta-analyzed hazard ratios of risk factors associated with hospitalizations pre- and post-KRT.

Figure S1. Variation of the diabetes coefficient for KRT (A), CVD (B), and death (C) across 19 cohorts in the main analysis.

Figure S2. Meta-regression analyses for effect of diabetes on the risk of KRT according to various baseline characteristics.

Figure S3. Meta-regression analyses for effect of sex on the risk of CVD according to various baseline characteristics.

Figure S4. Meta-regression analyses for effect of sex on the risk of mortality according to various baseline characteristics.

Figure S5. Meta-regression analyses for effect of diabetes on the risk of mortality according to various baseline characteristics.

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at www.kireports.org.

Supplementary Material

(study acronyms/abbreviations are listed in Appendix S2).

Data analysis overview and analytic notes for some individual studies.

Acronyms or abbreviations for studies included in the current report and their key references linked to the Web references.

Acknowledgments and funding for collaborating cohorts.

Underlying data selection by cohort.

Unadjusted incidence rates for KRT by participating cohort.

Meta-analyzed hazard ratios of risk factors associated with KRT and mortality in all 28 cohorts.

Unadjusted incidence rate of hospitalizations pre- and post-KRT by participating cohort.

Meta-analyzed hazard ratios of risk factors associated with hospitalizations pre- and post-KRT.

Variation of the diabetes coefficient for KRT (A), CVD (B), and death (C) across 19 cohorts in the main analysis.

Meta-regression analyses for effect of diabetes on the risk of KRT according to various baseline characteristics.

Meta-regression analyses for effect of sex on the risk of CVD according to various baseline characteristics.

Meta-regression analyses for effect of sex on the risk of mortality according to various baseline characteristics.

Meta-regression analyses for effect of diabetes on the risk of mortality according to various baseline characteristics.

References

- 1.Levin A., Tonelli M., Bonventre J. Global kidney health 2017 and beyond: a roadmap for closing gaps in care, research, and policy. Lancet. 2017;390:1888–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30788-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanner R.M., Gutierrez O.M., Judd S. Geographic variation in CKD prevalence and ESRD incidence in the United States: results from the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61:395–403. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L., Wang F., Wang L. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2012;379:815–822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruck K., Stel V.S., Gambaro G. CKD prevalence varies across the European general population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:2135–2147. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015050542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasparini A., Evans M., Coresh J. Prevalence and recognition of chronic kidney disease in Stockholm healthcare. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:2086–2094. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Go A.S., Chertow G.M., Fan D. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Velde M., Matsushita K., Coresh J. Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. A collaborative meta-analysis of high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1341–1352. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tangri N., Stevens L.A., Griffith J. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305:1553–1559. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coresh J., Selvin E., Stevens L.A. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsushita K., Ballew S.H., Astor B.C. Cohort profile:the chronic kidney disease prognosis consortium. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1660–1668. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coresh J., Turin T.C., Matsushita K. Decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate and subsequent risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality. JAMA. 2014;311:2518–2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levey A.S., Stevens L.A., Schmid C.H. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levey A.S., Coresh J., Greene T. Expressing the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate with standardized serum creatinine values. Clin Chem. 2007;53:766–772. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.077180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grams M.E., Sang Y., Levey A.S. Kidney-failure risk projection for the living kidney-donor candidate. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:411–421. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borenstein M., Hedges L.V., Higgins J.P. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 2009. Introduction to Meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riley R.D., Higgins J.P., Deeks J.J. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ. 2011;342:d549. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrington W., Staplin N., Judge P.K. Evidence for reverse causality in the association between blood pressure and cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic kidney disease. Hypertension. 2017;69:314–322. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroeder E.B., Yang X., Thorp M.L. Predicting 5-year risk of RRT in stage 3 or 4 CKD: development and external validation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:87–94. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01290216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson E.S., Thorp M.L., Platt R.W. Predicting the risk of dialysis and transplant among patients with CKD: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:653–660. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang W., Xie D., Anderson A.H. Association of kidney disease outcomes with risk factors for CKD: findings from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:236–243. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Nicola L., Chiodini P., Zoccali C. Prognosis of CKD patients receiving outpatient nephrology care in Italy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2421–2428. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01180211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans M., Fryzek J.P., Elinder C.G. The natural history of chronic renal failure: results from an unselected, population-based, inception cohort in Sweden. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:863–870. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundstrom U.H., Gasparini A., Bellocco R. Low renal replacement therapy incidence among slowly progressing elderly chronic kidney disease patients referred to nephrology care:an observational study. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18:59. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0473-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallan S.I., Matsushita K., Sang Y. Age and association of kidney measures with mortality and end-stage renal disease. JAMA. 2012;308:2349–2360. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.16817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Ghoul B., Elie C., Sqalli T. Nonprogressive kidney dysfunction and outcomes in older adults with chronic kidney disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2217–2223. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Visser A., Dijkstra G.J., Kuiper D. Accepting or declining dialysis: considerations taken into account by elderly patients with end-stage renal disease. J Nephrol. 2009;22:794–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stel V.S., Dekker F.W., Ansell D. Residual renal function at the start of dialysis and clinical outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:3175–3182. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang D.H., Yu E.S., Yoon K.I. The impact of gender on progression of renal disease: potential role of estrogen-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor regulation and vascular protection. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:679–688. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63155-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silbiger S.R., Neugarten J. The role of gender in the progression of renal disease. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 2003;10:3–14. doi: 10.1053/jarr.2003.50001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cobo G., Hecking M., Port F.K. Sex and gender differences in chronic kidney disease: progression to end-stage renal disease and haemodialysis. Clin Sci. 2016;130:1147–1163. doi: 10.1042/CS20160047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kausz A.T., Obrador G.T., Arora P. Late initiation of dialysis among women and ethnic minorities in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:2351–2357. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11122351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coresh J., Byrd-Holt D., Astor B.C. Chronic kidney disease awareness, prevalence, and trends among U.S. adults, 1999 to 2000. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:180–188. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grams M.E., Chow E.K.H., Segev D.L. Lifetime incidence of CKD stages 3–5 in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:245–252. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McClellan W., Warnock D.G., McClure L. Racial differences in the prevalence of chronic kidney disease among participants in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Cohort Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1710–1715. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005111200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parsa A., Kao W.H., Xie D. APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2183–2196. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naik R.P., Derebail V.K., Grams M.E. Association of sickle cell trait with chronic kidney disease and albuminuria in African Americans. JAMA. 2014;312:2115–2125. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fox C.S., Larson M.G., Leip E.P. Predictors of new-onset kidney disease in a community-based population. JAMA. 2004;291:844–850. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.7.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.D'Agostino R.B., Vasan R.S., Pencina M.J. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haroun M.K., Jaar B.G., Hoffman S.C. Risk factors for chronic kidney disease: a prospective study of 23,534 men and women in Washington County. Maryland. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2934–2941. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000095249.99803.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tangri N., Grams M.E., Levey A.S. Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315:164–174. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bolignano D., Zoccali C. Non-proteinuric rather than proteinuric renal diseases are the leading cause of end-stage kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:ii194–ii199. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carrero J.J., Grams M.E., Sang Y. Albuminuria changes are associated with subsequent risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality. Kidney Int. 2017;91:244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xia J., Wang L., Ma Z. Cigarette smoking and chronic kidney disease in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:475–487. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Staplin N., Haynes R., Herrington W.G. Smoking and adverse outcomes in patients with CKD: The Study of Heart and Renal Protection (SHARP) Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68:371–380. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peralta C.A., Norris K.C., Li S. Blood pressure components and end-stage renal disease in persons with chronic kidney disease:the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:41–47. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie X., Atkins E., Lv J. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes:updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:435–443. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00805-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grams ME, Sang Y, Ballew SH, et al. Predicting timing of clinical outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease and severely decreased glomerular filtration rate [e-pub ahead of print]. Kidney Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(study acronyms/abbreviations are listed in Appendix S2).

Data analysis overview and analytic notes for some individual studies.

Acronyms or abbreviations for studies included in the current report and their key references linked to the Web references.

Acknowledgments and funding for collaborating cohorts.

Underlying data selection by cohort.

Unadjusted incidence rates for KRT by participating cohort.

Meta-analyzed hazard ratios of risk factors associated with KRT and mortality in all 28 cohorts.

Unadjusted incidence rate of hospitalizations pre- and post-KRT by participating cohort.

Meta-analyzed hazard ratios of risk factors associated with hospitalizations pre- and post-KRT.

Variation of the diabetes coefficient for KRT (A), CVD (B), and death (C) across 19 cohorts in the main analysis.

Meta-regression analyses for effect of diabetes on the risk of KRT according to various baseline characteristics.

Meta-regression analyses for effect of sex on the risk of CVD according to various baseline characteristics.

Meta-regression analyses for effect of sex on the risk of mortality according to various baseline characteristics.

Meta-regression analyses for effect of diabetes on the risk of mortality according to various baseline characteristics.