Summary

Secondary caries at the tooth-resin interface is the primary reason for replacement of resin composite restorations. The tooth-resin interface is formed by the interlocking of resin material with hydroxyapatite crystals in enamel and collagen mesh structure in dentin. Efforts to strengthen the tooth-resin interface have identified chemical agents with dentin collagen cross-linking potential and antimicrobial activities. The purpose of the present study was to assess protective effects of bioactive primer against secondary caries development around enamel and dentin margins of class V restorations, using an in vitro bacterial caries model. Class V composite restorations were prepared on 60 bovine teeth (n=15) with pretreatment of the cavity walls with control buffer solution, an enriched fraction of grape seed extract (e-GSE), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl aminopropyl)-carbodiimide/N-hydroxysuccinimide, or chlorhexidine digluconate. After incubating specimens in a bacterial model with Streptococcus mutans for four days, dentin and enamel were assessed by fluorescence microscopy. Results revealed that only the naturally occurring product, e-GSE, significantly inhibited the development of secondary caries immediately adjacent to the dentin-resin interface, as indicated by the caries inhibition zone. No inhibitory effects were observed in enamel margins. The results suggest that the incorporation of e-GSE into components of the adhesive system may inhibit secondary caries and potentially contribute to the protection of highly vulnerable dentin-resin margins.

Introduction

Resin composite is commonly used for the direct restoration of missing tooth structures. In 2006, the number of resin composite restorations placed in the United States was 121 million, compared with 52.2 million for its alternative, amalgam.1 In addition to esthetics, resin composites can adhere to tooth structure2 and allow for a conservative tooth preparation.3 However, the service life of resin composites is consistently shorter than amalgam.4,5 A 1%-3% annual failure rate has been reported for resin composite restorations with 50%-75% of failures resulting from secondary caries, followed by postoperative sensitivity and restoration fracture.2,6-8

As secondary caries develops at the margins between the restorative material and the tooth substrates, methods to improve the properties of the adhesive interface have been investigated. Resin polymerization reactions are associated with a volumetric shrinkage that induces internal contraction stresses at the interface. The degree of polymerization and shrinkage was positively correlated with interfacial gap size as examined by micro-tomography.9 This may lead to marginal breakdown, marginal staining, and possible sites for the development of secondary caries.10 Furthermore, water absorption into porosities and degradation of resin by esterase activity in saliva contribute to the breakdown of margins over time.11

Approaches to strengthen the anchoring dentin matrix have gained increased interest. Specifically, the biomodification of dentin matrix by bioactive agents mediating exogenous collagen cross-linking.12 Carbodiimide, a synthetic chemical agent, was previously shown to reinforce dentin matrix and stabilize the dentin-resin bond over time by inducing zero-length cross-links.13 Proanthocyanidins (PACs) are plant-derived polyphenolic compounds derived from catechins and form a structurally complex class of oligomers and polymers. Previous studies have shown that certain PACs can reinforce dentin selectively, improve the dentin-resin bond strength, and are suitable agents for primary caries prevention.12,14-17

With the median life span of resin composite restorations being eight years in adults,18 multiple replacements are likely in the lifetime of a patient. Every time a replacement is made, more tooth structure is lost, and as a result, repeated failure and replacement of restorations can lead to premature tooth loss. The purpose of the present study was to assess the protective effects of bioactive agents against secondary caries development around enamel and dentin margins of class V resin composite restorations, using an in vitro bacterial caries model. The null hypothesis was that bioactive primers do not affect secondary caries development around enamel and dentin margins compared with control groups.

Methods and Materials

Materials

The chemical agents used in the study were as follows: 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl]ethane-sulfonic acid powder (HEPES, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl aminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC/NHS; Thermo Scientific Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), N-hydroxysuccinimide (Thermo Scientific Pierce), and chlorhexidine digluconate (CHX) stock solution (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA, USA).

Grape seed extract was obtained from Polyphenolics Inc. (Madera, CA, USA) and consisted of PACs with a degree of polymerization (DP) ranging from oligomers (2 to 7) up to polymers (8 to >20). Using a previously published method,19 the polymeric PACs were selectively depleted from the crude extract to yield an enriched oligomeric mixture (e-GSE). The refined e-GSE material was composed of phenolic acids and phenolic monomers (PACs) that are commonly known as catechins and the oligomeric PACs. Gravimetrically, approximately 70% of the e-GSE fraction consisted of flavan-3-ol monomers; the remaining 30% was oligomeric PACs (OPACs). Among the OPACs in e-GSE, approximately 50% are dimers, and the other half are mid- to high-order OPACs. Both classes of compounds are jointly referred to as PACs in the following.

Restorative Procedures and Specimen Preparation

Bovine incisors were placed in 0.1% thymol solution for four weeks. Teeth were cleaned to remove debris, periodontal ligament, and cementum of the root surfaces, and then they were visually inspected and excluded if enamel defects and white spots were detected with a magnifying dental loupe. Teeth were sectioned 4 mm above and 4 mm below the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) at the mid-mesial and mid-distal surfaces using a diamond wafering blade (Buehler- Series 15LC Diamond, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA). Teeth were further sectioned into two halves to obtain mesial and distal sections to a final rectangular dimension of 8 mm width × 8 mm length×1.5-2 mm thickness. Class V preparations of 3 mm width×3 mm length×1 mm depth were cut at the CEJ using a flat-end carbide bur (#558, Brasseler USA Dental, Savannah, GA, USA) in a high-speed handpiece with air/water coolant. Enamel and root dentin margins were prepared at 90° to the tooth surface, and burs were changed every five preparations.

Cavity preparations were randomly assigned to four groups (n=15). For the control group (HEPES primer), cavity walls were etched with 32% phosphoric acid (Scotchbond, 3M ESPE, St Paul, MN, USA) for 15 seconds and rinsed with distilled water for 30 seconds. Preparations were blotted dry with an absorbent tissue (KimWipe, Kimberly-Clark Corporation, Irving, TX, USA) and primed with 20 mM HEPES buffer for one minute, rinsed for 30 seconds, and blotted dry with an absorbent tissue, and a drop of Adper Single Bond Plus (3M ESPE) was actively applied on the preparation surfaces. The adhesive layer was air dried to remove excess solvent and light cured for 20 seconds (Optilux 501 light unit at 830 mW/cm2, Kerr, Orange, CA, USA). Preparations were filled with Filtek Supreme Plus Universal composite material (3M ESPE) in two vertical increments and light cured for 40 seconds each. Immediately after the final curing, restorations were polished with coarse-, medium-, and fine-grit aluminum-oxide abrasive discs (Sof-Lex, 3M/ESPE) in a slow speed handpiece.

The experimental groups followed the same restorative sequence, except for the following protocols for each primer: e-GSE primer, priming solution containing 15 w/v% e-GSE was applied for one minute and rinsed with distilled water for 30 seconds, modified from Castellan and others20; EDC/NHS primer, priming solution containing 0.3 M EDC/0.12 M NHS was applied for one minute21 and rinsed for one minute; and CHX primer, priming solution containing 2% chlorhexidine was applied for 30 seconds and blotted dry.22

Artificially Induced Secondary Caries

Cosmetic nail varnish was applied 1 mm away from the margins of the restorations and air dried for 40 minutes. Specimens were disinfected in 70% ethanol for 20 minutes,23 rinsed with sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) twice, and stored in sterile PBS at 4°C overnight. Streptococcus mutans UA159 was aerobically cultured on Brain Heart Infusion (BHI, Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) agar, and a colony was inoculated into BHI broth and incubated for 18-20 hours at 37°C. Then, cells were washed twice with PBS and suspended in fresh medium supplemented with 1% sucrose (BHIS) and standardized to 1 × 108 cells/mL spectrophotometrically (absorbance of 0.20 at 550 nm; Spectronic 601, Milton Roy, Ivyland, PA, USA). Specimens were inoculated with S. mutans suspension in BHIS for 4 hours at 37°C, after which the media were replaced with BHI without sucrose for the next 20 hours (modified protocol from Fontana and others).24 Wells were gently rinsed with PBS buffer twice following each media change. At the end of a four-day challenge, specimens were removed from the wells and rinsed in running water thoroughly. Specimens were sectioned along the axis of the tooth, through the restorations. Sections were embedded in epoxy resin overnight and polished with #320, #400, #600, #800, and #1200 grit silicon carbide abrasive papers (Buehler) under running water.

Fluorescence Microscopy Analysis

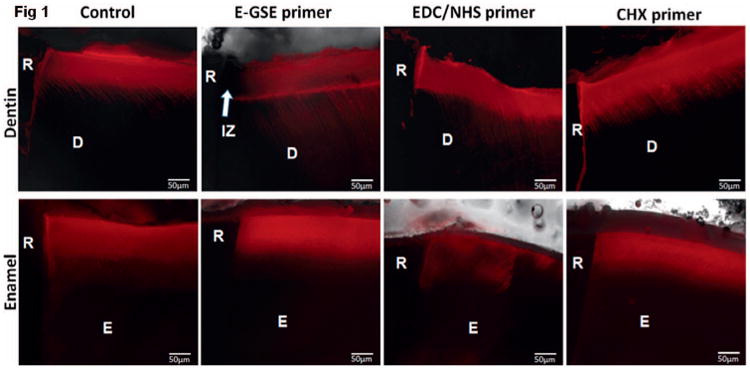

Specimens were hydrated with distilled water for one hour and stained overnight with 0.1 mM rhodamine B solution (pH 7.2), following the protocol described by Fontana and others.25 After elapsed time, specimens were rinsed in running water for one minute and blotted dry with absorbent paper. Specimens were examined under a fluorescence microscope (DMI 6000 B, Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) with a connected digital camera (Hamamatsu, Skokie, IL, USA) and LAS AF software (Leica). Images of light differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, as well as red fluorescence at 529 nm, were captured. The same microscope settings were used for all images. Images were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Positions of restoration margins were identified in DIC images and transferred to fluorescence images. Lesion depth (LD) was measured 125 μm away from the restoration margin as the depth of rhodamine stained from the surface. Secondary caries was measured as total fluorescence (TF; Figure 1),25 where a fluorescent area was marked and TF was measured as area multiplied by mean fluorescence. For dentin, TF was measured within 250, 100, 50, or 25 μm from the restoration. For enamel, TF was measured within 250 or 25 μm from the restoration.

Figure 1. Representative images of rhodamine-B–infiltrated dentin and enamel depicting demineralization around class V restorations restored with bioactive primers. R, resin; D, dentin; E, enamel; IZ, inhibition zone.

Data were analyzed for the effect of treatment on LD and TF by one-way analysis of variance and Bonferroni post hoc test at α=0.05.

Results

Margins in Dentin

LDs were similar across the treatment groups (Figure 1); there were no statistically significant mean differences in LDs (Table 1; p>0.05). Most interestingly, an inhibition zone (IZ) was noted in the e-GSE group, where rhodamine staining was scarce next to the tooth-resin interface (Figure 1). Such IZ was not observed in the control or any other treatment group. When examined up to 250 μm adjacent to the restoration, there was no statistically significant difference in total fluorescence among all treatment groups (p>0.05). When the area was limited to 100 or 50 μm adjacent to the restoration, a statistically significant difference was observed between the e-GSE and CHX groups (p<0.05). When the area was limited to 25 μm adjacent to the restoration, total fluorescence for the e-GSE group was significantly lower than all the other groups (Table 1). The e-GSE group had the least amount of demineralization, especially near the restoration margin, which was consistent with the presence of an inhibition zone (Figure 1). The e-GSE primer showed a protective effect immediately adjacent to the dentin-resin interface.

Table 1. Secondary Caries Lesions Depth and Total Fluorescence Calculated by Area and Distances From the Dentin and Enamel Marginsa.

| Cavity primers | Margins in dentin | Margins in enamel | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion depth (μm) | Total fluorescence (×105), mean (SD) | Lesion depth (μm) | Total fluorescence (×105), mean (SD) | |||||

| 250 μm | 100 μm | 50 μm | 25 μm | 250 μm | 25 μm | |||

| Control | 72.5 (9.8) | 8.06 a (5.51) | 3.37 ab (1.98) | 1.82 ab (1.04) | 1.04 b (0.57) | 80.5 (29.7) | 6.20 (6.93) | 4.16 (3.71) |

| e-GSE | 74.8 (15.0) | 8.23 a (5.57) | 2.29 a (1.63) | 0.79 a (0.70) | 0.27 a (0.30) | 67.8 (18.7) | 4.06 (3.50) | 2.20 (1.37) |

| EDC/NHS | 71.2 (16.4) | 10.75 a (6.78) | 4.45 ab (3.14) | 2.29 ab (2.05) | 1.24 b (1.14) | 71.7 (22.6) | 2.42 (3.90) | 2.40 (2.79) |

| CHX | 74.4 (13.1) | 12.29 a (6.27) | 4.86 b (2.85) | 2.69 b (1.81) | 1.37 b (0.83) | 83.4 (49.3) | 5.55 (6.43) | 3.21 (3.12) |

Different letters indicate statistically significant differences in each column (p<0.05).

Margins in Enamel

LDs in enamel were similar across the experimental groups as shown in Table 1 (p>0.05) and Figure 1. Regardless of the areas examined, 250 or 25 μm adjacent to the restoration, there were no statistically significant mean differences in TF among all groups (Table 1). Enamel demineralization did not differ across the treatment groups (p>0.05).

Discussion

An S. mutans–induced caries model was used for artificial caries development, which was clinically more relevant than a pH-cycling model. Carious lesions in dentin were more aggressive closer to the restoration (distance 100 vs 300 μm). The current findings confirm that dentin-resin interface seems to be more susceptible to caries progression around the restoration margin than the enamel-resin interface, which may be associated to less effective bonding to dentin compared with enamel. Resin composite's surface roughness and hydrophobicity26,27 may have favored adhesion of oral streptococci and contributed to more demineralization closer to the dentin margins. The integrity of the tooth-resin interface influences the progression of caries around the restoration margin, with microleakage providing an additional portal for bacterial attack.28,29

One of the most interesting results of this study was that the e-GSE primer inhibited secondary caries development immediately adjacent to the dentin-resin interface. The e-GSE protective effect against secondary caries development was clearly represented by the presence of an inhibition zone, as well as the lowest total fluorescence relative to all other groups, measured within 25 μm of the restoration (Table 1). Three possible mechanisms of actions can be considered for e-GSE to inhibit secondary caries in dentin: (1) tissue stabilization, (2) a tighter interfacial seal, and (3) antimicrobial activity. As dentin is relatively porous, the e-GSE PACs were able to diffuse further than a few micrometers of the hybrid layer and protect dentin beyond the interface. Collagen cross-linking has been suggested to stabilize dentin by providing a scaffold for mineralization and a barrier for acid diffusion and mineral loss.14,16 The observed fluorescence patterns suggest that surface caries lesions progressed to the peripheries until limited by PAC-treated dentin near the interface.

A tighter resin seal is achievable at the dentin-resin interface when the collagen mesh structure is intact and capable of forming a hybrid layer.30 The e-GSE primer showed these properties, inducing collagen cross-linking and maintaining the collagen mesh structure before application of the bonding agent. A tighter interfacial seal is considered to be more resistant to bacterial leakage and acid diffusion; previous studies reported a positive correlation between the interface gap size and secondary caries.31-33 Studies have suggested that 250- to 400-μm gaps contribute to the development of secondary caries and do not consider an open margin as an indication for replacement of a restoration.4 However, gaps of 50 μm and less were previously shown to be colonized by S. mutans biofilm and subsequently caries being formed specifically at the interface.28,29 An additional study will be required to assess the effect of e-GSE on marginal integrity without a caries challenge.

PACs are known for general antimicrobial properties. Specific to cariogenic bacteria, PACs inhibit surface-adsorbed glucosyltransferases and acid production by S. mutans,34 as well as decrease the growth of S. mutans and biofilm formation.35 Catechins such as epigallocatechin gallate suppress gtf genes associated with S. mutans biofilm formation.36 The antimicrobial activity of PACs against cariogenic bacteria likely contributes to the inhibition of dentin demineralization by e-GSE, as the dentin tissue might function as a reservoir for PACs bound to the collagen backbone.

All other agents evaluated in this study had no significant effect on inhibiting secondary caries formation around resin composite restorations. Although EDC has collagen cross-linking activity,37 it did not have the same effect as e-GSE. EDC's cross-linking ability is known to be less potent than other chemical agents,13,38 and no effect was observed on interfacial nanoleakage compared with a control.38 Although EDC was shown to inhibit bacterial membrane ATPases39 and sugar uptake in oral streptococcal bacteria,40 EDC does not take part in newly induced cross-linkage and is quickly hydrolyzed in solution, thus limiting a significant antimicrobial protection at the adhesive interface.

CHX was not found to inhibit secondary caries in any of the outcomes. A possible explanation is that CHX does not exhibit a permanent binding mechanism to the dentin structure and that the residual amount of CHX at the interface was too low for exerting bactericidal activity as it is only bacterio-static at low concentrations.41 Furthermore, a few studies have suggested weakening of the tooth-resin bond by chlorhexidine.42,43

As with any in vitro study, cautions remain when extrapolating results to the actual oral environment. The bacterial caries model in this study involved only a single species of cariogenic bacteria (S. mutans). However, the present design provides significant and promising findings. Inevitably, the hybrid layer is subjected to degradation and fatigue over time.30,44 Aging of specimens was not simulated in the present work, but will be pursued in future studies.

Conclusions

Bacterial-induced secondary caries develops in enamel and dentin regardless of the composition of the primer solution. Lesions were more aggressive closer to the dentin-resin adhesive margins. An enriched fraction of grape seed extract, e-GSE, significantly inhibited secondary caries development within 25 μm of the restoration margin in dentin. None of the other treatments inhibited secondary caries development around resin composite restorations. The results suggest that incorporation of e-GSE in the restorative procedure of resin composites may reduce secondary caries development immediately around highly susceptible root dentin margins.

Clinical Relevance.

Secondary caries is the primary reason for the replacement of resin composite restorations. Using an artificially induced bacterial carious model, this study found that a bioactive primer containing plant-derived proanthocyanidins inhibited secondary caries formation at the dentin-resin interface.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grant DE024040. The authors thank Dr. Wei Li for assistance in the microbiology assays.

Footnotes

Regulatory Statement: This study was conducted in accordance with all the provisions of the local human subjects oversight committee guidelines and policies of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Conflict of Interest: The authors of this manuscript certify that they have no proprietary, financial, or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service, and/or company that is presented in this article.

Contributor Information

Go Eun Kim, Restorative Dentistry, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Ariene Arcas Leme-Kraus, Restorative Dentistry, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Rasika Phansalkar, Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Grace Viana, Orthodontics, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Christine Wu, Pediatric Dentistry, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Shao-Nong Chen, Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Guido Frank Pauli, Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Ana Karina Barbieri Bedran-Russo, Restorative Dentistry, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

References

- 1.ADA Surveys. 2005-06 survey of dental services rendered. American Dental Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demarco FF, Correa MB, Cenci MS, Moraes RR, Opdam NJ. Longevity of posterior composite restorations: not only a matter of materials. Dental Materials. 2012;28(1):87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cenci M, Demarco F, de Carvalho R. Class II composite resin restorations with two polymerization techniques: Relationship between microtensile bond strength and marginal leakage. Journal of Dentistry. 2005;33(7):603–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mjor IA, Dahl JE, Moorhead JE. Age of restorations at replacement in permanent teeth in general dental practice. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 2000;58(3):97–101. doi: 10.1080/000163500429208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mjor IA, Dahl JE, Moorhead JE. Placement and replacement of restorations in primary teeth Acta. Odontologica Scandinavica. 2002;60(1):25–28. doi: 10.1080/000163502753471961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.da Rosa Rodolpho PA, Cenci MS, Donassollo TA, Loguercio AD, Demarco FF. A clinical evaluation of posterior composite restorations: 17-year findings. Journal of Dentistry. 2006;34(7):427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pallesen U, van Dijken JW, Halken J, Hallonsten AL, Hoigaard R. Longevity of posterior resin composite restorations in permanent teeth in Public Dental Health Service: A prospective 8 years follow up. Journal of Dentistry. 2013;41(4):297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lempel E, Toth A, Fabian T, Krajczar K, Szalma J. Retrospective evaluation of posterior direct composite restorations: 10-year findings. Dental Materials. 2015;31(2):115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kakaboura A, Rahiotis C, Watts D, Silikas N, Eliades G. 3D-marginal adaptation versus setting shrinkage in light-cured microhybrid resin composites. Dental Materials. 2007;23(3):272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider LF, Cavalcante LM, Silikas N. Shrinkage stresses generated during resin-composite applications: A review. Journal of Dental Biomechanics. 2010;2010:131630. doi: 10.4061/2010/131630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kermanshahi S, Santerre JP, Cvitkovitch DG, Finer Y. Biodegradation of resin-dentin interfaces increases bacterial microleakage. Journal of Dental Research. 2010;89(9):996–1001. doi: 10.1177/0022034510372885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bedran-Russo AK, Pauli GF, Chen SN, McAlpine J, Castellan CS, Phansalkar RS, Aguiar TR, Vidal CM, Napotilano JG, Nam JW, Leme AA. Dentin biomodification: strategies, renewable resources and clinical applications. Dental Materials. 2014;30(1):62–76. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bedran-Russo AK, Vidal CM, Dos Santos PH, Castellan CS. Long-term effect of carbodiimide on dentin matrix and resin-dentin bonds. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2010;94(1):250–255. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie Q, Bedran-Russo AK, Wu CD. In vitro remineralization effects of grape seed extract on artificial root caries. Journal of Dentistry. 2008;36(11):900–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walter R, Miguez PA, Arnold RR, Pereira PN, Duarte WR, Yamauchi M. Effects of natural cross-linkers on the stability of dentin collagen and the inhibition of root caries in vitro. Caries Research. 2008;42(4):263–268. doi: 10.1159/000135671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavan S, Xie Q, Hara AT, Bedran-Russo AK. Biomimetic approach for root caries prevention using a proanthocyanidin-rich agent. Caries Research. 2011;45(5):443–447. doi: 10.1159/000330599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castellan CS, Bedran-Russo AK, Antunes A, Pereira PN. Effect of dentin biomodification using naturally derived collagen cross-linkers: One-year bond strength study. International Journal of Dentistry. 2013;2013:918010. doi: 10.1155/2013/918010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke FJ, Wilson NH, Cheung SW, Mjor IA. Influence of patient factors on age of restorations at failure and reasons for their placement and replacement. Journal of Dentistry. 2001;29(5):317–324. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(01)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phansalkar RS, Nam JW, Chen SN, McAlpine JB, Napolitano JG, Leme A, Vidal CMP, Aguiar T, Bedran-Russo AK, Pauli GF. A galloylated dimeric proanthocyanidin from grape seed exhibits dentin bio-modification potential. Fitoterapia. 2015;101:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castellan CS, Pereira PN, Grande RH, Bedran-Russo AK. Mechanical characterization of proanthocyanidin-dentin matrix interaction. Dental Materials. 2010;26(10):968–973. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazzoni A, Angeloni V, Apolonio FM, Scotti N, Tjaderhane L, Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Di Lenarda R, Tay FR, Pashley DH, Breschi L. Effect of carbodiimide (EDC) on the bond stability of etch-and-rinse adhesive systems. Dental Materials. 2013;29(10):1040–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sartori N, Stolf SC, Silva SB, Lopes GC, Carrilho M. Influence of chlorhexidine digluconate on the clinical performance of adhesive restorations: A 3-year follow-up. Journal of Dentistry. 2013;41(12):1188–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayati F, Okada A, Kitasako Y, Tagami J, Matin K. An artificial biofilm induced secondary caries model for in vitro studies. Australian Dental Journal. 2011;56(1):40–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fontana M, Dunipace AJ, Gregory RL, Noblitt TW, Li Y, Park KK, Stookey GK. An in vitro microbial model for studying secondary caries formation. Caries Research. 1996;30(2):112–118. doi: 10.1159/000262146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontana M, Gonzalez-Cabezas C, Haider A, Stookey GK. Inhibition of secondary caries lesion progression using fluoride varnish. Caries Research. 2002;36(2):129–135. doi: 10.1159/000057871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hahnel S, Henrich A, Rosentritt M, Handel G, Burgers R. Influence of artificial ageing on surface properties and Streptococcus mutans adhesion to dental composite materials. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 2010;21(2):823–833. doi: 10.1007/s10856-009-3894-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee BC, Jung GY, Kim DJ, Han JS. Initial bacterial adhesion on resin, titanium and zirconia in vitro. Journal of Advanced Prosthodontics. 2011;3(2):81–84. doi: 10.4047/jap.2011.3.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seemann R, Bizhang M, Kluck I, Loth J, Roulet JF. A novel in vitro microbial-based model for studying caries formation—Development and initial testing. Caries Research. 2005;39(3):185–190. doi: 10.1159/000084796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diercke K, Lussi A, Kersten T, Seemann R. Isolated development of inner (wall) caries like lesions in a bacterial-based in vitro model. Clinical Oral Investigations. 2009;13(4):439–444. doi: 10.1007/s00784-009-0250-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamazaki PC, Bedran-Russo AK, Pereira PN. The effect of load cycling on nanoleakage of deproteinized resin/dentin interfaces as a function of time. Dental Materials. 2008;24(7):867–873. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Totiam P, Gonzalez-Cabezas C, Fontana MR, Zero DT. A new in vitro model to study the relationship of gap size and secondary caries. Caries Research. 2007;41(6):467–473. doi: 10.1159/000107934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cenci MS, Pereira-Cenci T, Cury JA, Ten Cate JM. Relationship between gap size and dentine secondary caries formation assessed in a microcosm biofilm model. Caries Research. 2009;43(2):97–102. doi: 10.1159/000209341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nassar HM, Gonzalez-Cabezas C. Effect of gap geometry on secondary caries wall lesion development. Caries Research. 2011;45(4):346–352. doi: 10.1159/000329384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duarte S, Gregoire S, Singh AP, Vorsa N, Schaich K, Bowen WH, Koo H. Inhibitory effects of cranberry polyphenols on formation and acidogenicity of Streptococcus mutans biofilms. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2006;257(1):50–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao W, Xie Q, Bedran-Russo AK, Pan S, Ling J, Wu CD. The preventive effect of grape seed extract on artificial enamel caries progression in a microbial biofilm-induced caries model. Journal of Dentistry. 2014;42(8):1010–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu X, Zhou XD, Wu CD. Tea catechin epigallocatechin gallate inhibits Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation by suppressing gtf genes. Archives of Oral Biology. 2012;57(6):678–683. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olde Damink LH, Dijkstra PJ, van Luyn MJ, van Wachem PB, Nieuwenhuis P, Feijen J. Cross-linking of dermal sheep collagen using a water-soluble carbodiimide. Biomaterials. 1996;17(8):765–773. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)81413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazzoni A, Apolonio FM, Saboia VP, Santi S, Angeloni V, Checchi V, Curci R, Di Lenarda R, Tay FR, Pashley DH, Breschi L. Carbodiimide inactivation of MMPs and effect on dentin bonding. Journal of Dental Research. 2014;93(3):263–268. doi: 10.1177/0022034513516465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abrams A, Baron C. Inhibitory action of carbodiimides on bacterial membrane ATPase. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1970;41(4):858–863. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keevil CW, Williamson MI, Marsh PD, Ellwood DC. Evidence that glucose and sucrose uptake in oral streptococcal bacteria involves independent phospho-transferase and proton-motive force-mediated mechanisms. Archives of Oral Biology. 1984;29(11):871–878. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(84)90085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russell AD. Chlorhexidine: Antibacterial action and bacterial resistance. Infection. 1986;14(5):212–215. doi: 10.1007/BF01644264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ercan E, Erdemir A, Zorba YO, Eldeniz AU, Dalli M, Ince B, Kalaycioglu B. Effect of different cavity disinfectants on shear bond strength of composite resin to dentin. Journal of Adhesive Dentistry. 2009;11(5):343–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elkassas DW, Fawzi EM, El Zohairy A. The effect of cavity disinfectants on the micro-shear bond strength of dentin adhesives. European Journal of Dentistry. 2014;8(2):184–190. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.130596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okuda M, Pereira PN, Nakajima M, Tagami J, Pashley DH. Long-term durability of resin dentin interface: Nanoleakage vs. microtensile bond strength. Operative Dentistry. 2002;27(3):289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]