Abstract

Jet-lag symptoms arise from temporal misalignment between the internal circadian clock and external solar time when traveling across multiple time zones. Light is known as a strong timing cue of the circadian clock. We here examined the effect of daily light on the process of jet lag by detecting c-Fos expression in the master clock neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) under 8-hr phase-advanced jet lag condition. In WT mice, c-Fos-immunoreactivity was found at 1–2 hours on the first day after light/dark (LD) phase-advance. This induction was also observed on the second and third days, although their levels were diminished day by day. In contrast, c-Fos induction in the SCN of V1a–/–V1b–/– mice, which show virtually no jet lag symptoms even after 8-hr phase-advance, was only detected on the first day. These results indicate that external light has affected SCN neuronal activity for 3 days after LD phase-advance in WT mice suggesting the continuous progress of activity change of SCN neurons under jet lag conditions. Noteworthy, limited c-Fos induction in V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN is also consistent with the rapid reentrainment of the SCN clock in mutant mice after 8-hr LD phase-advance.

Keywords: circadian rhythm, suprachiasmatic nucleus, c-Fos, jet lag, vasopressin receptor

I. Introduction

Most biological processes in the body have daily rhythms with a period of approximately 24-hr, and these rhythms are maintained even in the absence of external stimuli [6, 21]. The center of this biological clock system resides in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus [9, 25]. The internal oscillator composed of the clock genes in the SCN is entrained to the Earth’s 24-hr light/dark (LD) cycle by external timing cues, such as light and temperature. Thus, it is now considered that the internal biological clock system is supported to oscillate by the cyclic change of environmental timing cues.

However, the invention of modern conveniences now threatens our biological clock system. Artificial illumination widens our activity time and forces exposure to light that influences the clock. Moreover, a jet airplane enables us to cross multiple time zones within hours, dissociating biological rhythms from the environmental LD cycle (jet lag) and causing sleep disturbances and gastrointestinal distress [5, 17]. Equally as important, shift work and nighttime work could also lead to jet-lag-like experience. Repeated jet lag and rotating shift work both increase the risk of life-style related diseases, including cardiovascular complaints, metabolic insufficiency, and cancer [3, 11, 19]. Although jet lag has been widely recognized as a chronobiological health problem [7, 15, 28], its specific molecular and cellular mechanisms are poorly clarified.

Jet lag is caused by the dissociation of the internal circadian clock and the environmental time. After traveling across the multiple time zones, the internal clock cannot phase-shift instantaneously to the local time like a watch after the shift of the LD cycle, but continues to oscillate autonomously according to its original time at departure for several cycles. Indeed, 8-hr phase-advance of LD cycle evoked a gradual shift of the locomotor activity rhythm and took 10 days for complete reentrainment to the new LD schedule in C57Bl/6 mice, which are widely used as a model animal for jet lag study [7, 15].

Since the full phase-shift of circadian rhythms takes 10 days after 8-hr LD advance, the daily environmental LD cycle might have an effect on the reentrainment progress of the behavioral rhythms. However, little is known about the effect of daily light on the neuronal activities in the SCN during the reentrainment process. Thus, we firstly examined the time-dependent effects of LD phase-advance on SCN neurons by detecting the expression of c-Fos, a useful physiological marker of neural activation [18] which was successfully used in the SCN [20], and phosphorylated mitogen activated protein kinase (pErk1/2) [13] in WT SCN throughout the first day (day 1) after 8-hr LD phase-advance. Secondly, we examined daily changes in the light effects on c-Fos expression in the SCN from the onset to the complete reentrainment to the new LD cycle after 8-hr LD phase-advance.

In contrast to the slow resetting of the locomotor activity in WT mice, we recently found that mice genetically lacking AVP receptors V1a and V1b (V1a–/–V1b–/– mice) are resistant to jet lag; circadian rhythms of behavior, clock gene expression, and body temperature immediately reentrained in the mutant mice to new LD cycles after 8-hr phase-advance [27]. Since V1a–/–V1b–/– mouse is an interesting animal model showing no jet lag symptoms, although they have an intact biological clock, we examined the daily effects of light exposure after 8-hr LD phase-advance in V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN and compared them to those in WT SCN in the present study. As expected, we confirmed the limited expression of c-Fos after LD advance and it soon disappeared in V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN.

II. Materials and Methods

Animals and jet lag experiment

V1a–/–V1b–/– mice [27] and C57Bl/6 mice (males, 2- to 5-month-old) were entrained to 12-hr light (~200 lux fluorescent light):12-hr dark (LD) cycle for at least two weeks with ad libitum access to food and water, and then the LD cycle was advanced by 8-hr lighting at ZT16 (Zeitgeber time 16). All experiments were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Kyoto University Animal Experimentation Committee.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry of c-Fos and phospho-Erk1/2, animals were anesthetized and circulationally perfused with cold fixative (4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PB). The isolated brains were post-fixed with the same fixative for 24 hr at 4°C and then transferred to 20% sucrose in 0.1 M PB for cryoprotection. Coronal brain cryosections (30 μm thick) were processed for free-floating immunohistochemistry with rabbit polyclonal antibody against c-Fos (abcam, ab7963) and rabbit polyclonal antibody against Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) (Cell Signaling, 9101). In brief, the free-floating sections, pretreated with hydrogen peroxide (1.5%, in 0.1 M PB, for 20 min at 4°C), were blocked with 5% horse serum in 0.1 M PB for 1 hr at room temperature. Then, the sections were incubated with the primary antibody [1:10,000 (c-Fos) and 1:500 dilution (phospho-Erk1/2), in 0.1 M PB containing 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBX)] for 72 hr at 4°C. After washing with PBX, the sections were incubated with a secondary antibody [biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, BA-1000), 1:1000 dilution in PBX] for 16 hr at 4°C. The immunoreactivities were visualized according to a standard avidin-biotin-immunoperoxidase procedure (Vectorstain Elite ABC kit, Vector Laboratories). The immunostained sections were washed with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and coverslipped with Entellan after dehydration.

Measurement of the number of c-Fos-positive cells

c-Fos expression offers cellular resolution, since immunohistochemical c-Fos staining is localized to the cell nucleus. Coronal SCN sections at the middle level of its rostro-caudal axis (three sections per animal) were used for the measurement of positive cell counts. The number of c-Fos-positive cells in the SCN were counted using ImageJ (NIH), as described previously [14, 24]. First, images were converted from grayscale to binary black and white images reflecting stained and unstained areas from the micrographs. The image threshold was determined using the triangle method within ImageJ and a set of cells from each sample was outlined as a Region of Interest (ROI). The number of cells were extracted using the “Analyze Particles” function. Selected cells were reconfirmed visually one by one and counted only when the cytoplasm was clearly labeled against the background. To minimize technical variation throughout the experiment, sections from different experimental conditions were collected into one group and c-Fos immunostaining was performed simultaneously. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine if significant differences were present (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, and *P < 0.05). All statistical analyses were performed using a Graphpad Prism 6.0 software. Sample sizes at each time point were as follows: at ZT1 (Pre-jet lag), WT SCN n = 6, V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN n = 4; ZT17 (Pre-jet lag), 10, 6; day 1, 6, 10; day 2, 8, 6; day 3, 12, 12; day 4, 10, 6; day 5, 10, 6; day 6, 6 (WT), and day 7, 6 (WT), respectively.

III. Results

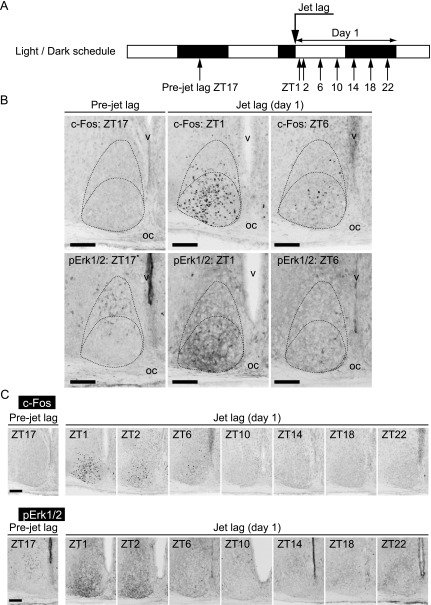

Time-course analyses of the light effect on SCN cells after LD phase-advance in WT mice

We examined the acute effect of light on the neuronal activities in the SCN on the first day after the onset of jet lag. To address this issue, we first immunostained c-Fos expression in WT SCN throughout the first day (day 1) after 8-hr LD phase-advance (Fig. 1A). Before LD phase-advance (Pre-jet lag), c-Fos was rarely expressed in the SCN at ZT17 (ZT0 indicates lights-on and ZT12 lights-off) (Fig. 1B). However, on day 1 just after 8-hr LD phase-advance (jet lag), c-Fos was strongly induced in many cells in the ventrolateral to the central region of the SCN at ZT1 (one hour after the onset of advanced light-on) (Fig. 1B), which corresponded to ZT17 in LD cycle before LD phase-advance (Pre-jet lag). Thereafter, c-Fos induction decreased gradually (ZT2-ZT6) but remained in the ventral to the central parts of the SCN, and disappeared at ZT10 (Fig. 1B, C).

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemistry showing c-Fos and pErk1/2 expression in WT SCN on day 1 after LD phase-advance. (A) Sampling time course. White and black bars indicate light and dark phases, respectively. (B, C) Representative images of immunoreactivity to c-Fos and pErk1/2 in WT SCN before or after jet lag. Boundaries of the SCN and the ventrolateral and the central parts are shown in the dotted lines in panel (B). oc, optic chiasma; v, third ventricle. Bar = 100 μm.

We also examined the phosphorylation state of Erk1/2 [13] by an antibody against Phospho-p44/42 Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204, pErk1/2). In pre-jet lag state, faint staining of pErk1/2 was observed in the dorsal part of the SCN at ZT17 (Fig. 1B), as previously reported as a night time signal [4, 13]. In contrast, pErk1/2-positive cells and fibers appeared in the ventrolateral and the central parts of the SCN at one hour after the onset of jet lag (ZT1 in Fig. 1B, lower-middle panel). Then, pErk1/2 signal gradually decreased during ZT2-ZT6 and was almost absent at ZT10 or later in the ventrolateral and the central region of the SCN (Fig. 1B, C).

These immunohistochemical activities of c-Fos and pErk1/2 indicate that advanced light under jet lag induces an immediate alternation of the signal transduction in the cells of the ventrolateral to the central SCN, which peaks at ZT1 and diminishes within several hours.

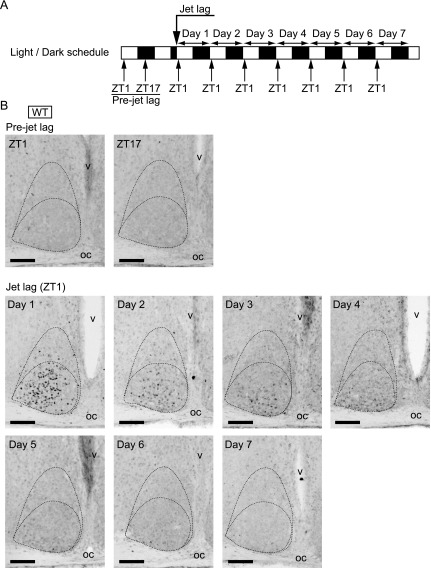

c-Fos immunoreactivity in the SCN of WT mice under jet lag conditions

Unlike pErk1/2, c-Fos expression offers cellular resolution, since immunohistochemical c-Fos staining is localized to the cell nucleus. Using this characterization of c-Fos immunostaining, we next examined the daily changes of c-Fos expression in WT SCN under jet lag conditions. We sacrificed WT mice at ZT1, when the effect of light was maximal, from day 1 to day 7 (Fig. 2A), and performed immunostaining using anti-c-Fos antibody (Fig. 2B). The positive c-Fos immunostained cells were observed in the ventrolateral to the central region of the SCN on day 1 after jet lag, and, to a lesser extent, on day 2. On day 3 and day 4, the stained cells were confined to the ventrolateral part of the SCN just above the optic chiasma. On day 6 and day 7, stained cells were not observed in the SCN.

Fig. 2.

c-Fos expression in WT SCN before or after jet lag. (A) Sampling time course. White and black bars indicate light and dark phases, respectively. (B) Representative images of immunoreactivity to c-Fos in the SCN of WT mice before or after jet lag. Boundaries of the SCN and the ventrolateral and the central parts are shown in the dotted lines. oc, optic chiasma; v, third ventricle. Bar = 100 μm.

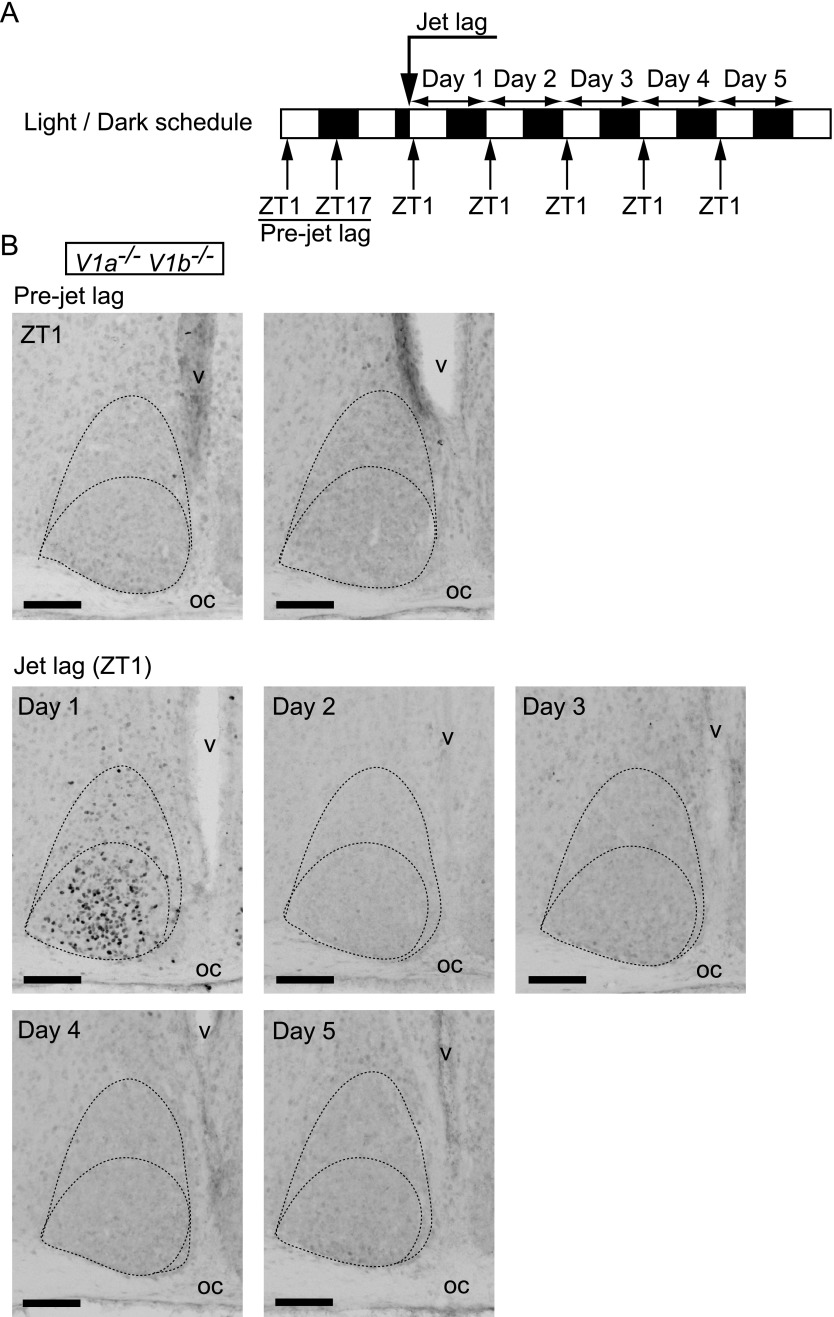

c-Fos immunoreactivity in the SCN of V1a–/–V1b–/– mice under jet lag conditions

It appears that c-Fos induction occurs in the SCN in relation to jet lag. To gain more insight into the correlation between jet lag process and c-Fos expression in the SCN, we performed the same jet lag experiment using V1a–/–V1b–/– mutant mice. Importantly, we previously demonstrated that these mutant mice differ from WT in showing immediate reentrainment to 8-hr phase-advance [27]. We examined c-Fos expression in the SCN at ZT1 until day 5 after 8-hr LD phase-advance of V1a–/–V1b–/– mice (Fig. 3). Similar to WT, c-Fos was not observed before the onset of jet lag and was strongly induced in the ventrolateral to the central parts of the SCN in V1a–/–V1b–/– mice on day 1 after jet lag. However, this induction was rapidly damped and c-Fos expression was no longer observed on day 2 or the following days in V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN, which was totally different from that of the c-Fos expression in WT SCN.

Fig. 3.

c-Fos expression in V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN before or after jet lag. (A) Sampling time course. White and black bars indicate light and dark phases, respectively. (B) Representative images of immunoreactivity to c-Fos in the SCN of V1a–/–V1b–/– mice before or after jet lag. Boundaries of the SCN and the ventrolateral and the central parts are shown in the dotted lines. oc, optic chiasma; v, third ventricle. Bar = 100 μm.

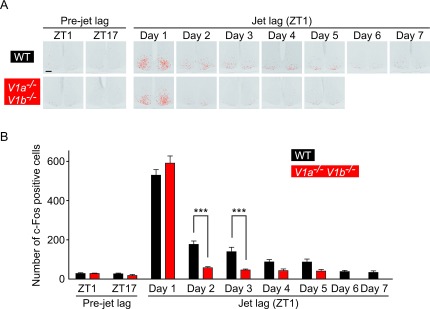

Quantitative changes in the number of c-Fos-positive neurons in the SCN of WT and V1a–/–V1b–/– mice under jet lag conditions

To quantitatively compare the c-Fos expression in WT and V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN under jet lag conditions, we performed an imaging analysis and counted the number of c-Fos-positive cells (Fig. 4). Whereas quite a few cells were positive in both WT and V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN in the pre-jet lag state, the numbers of c-Fos-positive cells were dramatically increased on day 1 in the SCN of both genotypes. Moreover, the level of induction was quite similar in WT and V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN on day 1. However, there was a marked difference between genotypes in the later days: the greater number of cells was continuously counted until day 5 in WT SCN, whereas the number of c-Fos-positive cells on day 2 or later was decreased to the level before jet lag in V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests indicated that the number of c-Fos-positive cells in WT SCN were greater than that in V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN on days 2–3 after LD phase-advance.

Fig. 4.

The number of c-Fos positive cells in WT and V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN under jet lag conditions. (A) Representative images of c-Fos-positives signals are indicated by red dots in the SCN of WT (upper) and V1a–/–V1b–/– (lower) mice before or after jet lag. Bar = 100 μm. (B) Values (mean ± s.e.m.) indicate the number of c-Fos positive cells in WT (black) and V1a–/–V1b–/– (red) SCN. ***P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test.

IV. Discussion

We examined the effect of 8-hr phase-advance of LD cycle causing jet lag on the expression of the early genes in the SCN. We found that c-Fos was induced in many cells in the ventrolateral and the central parts of both WT and V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN on day 1, but the number of c-Fos-positive cells in V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN returned to the basal level on day 2, whereas that in WT SCN was still greater on days 2–3. These results demonstrated that the effect of daily exposure to light decreases day by day after jet lag in both genotypes. It is strongly suggested that the transition of the phase of the circadian clock due to jet lag affects the reactivity of the clock to light exposure. The absence of the light effect on SCN cells suggests that the light-induced phase-shift of SCN cells has been completed on the second day after jet lag in V1a–/–V1b–/– SCN. Together with the complete change in the circadian expression profiles of Per1 and Dbp of the SCN to the new environmental LD cycles on day 2 [27], the present c-Fos data strongly suggest that V1a–/–V1b–/– mice truly show no jet lag symptoms and promptly adapt to the new environmental LD schedule.

Jet lag-induced c-Fos immunoreactivity is observed in the neurons in the ventrolateral and the central parts of the SCN where retinal fibers terminate [10, 22]. Since a brief light exposure (30 to 60 min of 200 lux light) at subjective night increases c-Fos expression selectively in the ventrolateral part of the SCN [8, 16], light may be the causative to affect the SCN cells under jet lag conditions. Compared to c-fos expression in the SCN under jet lag conditions in rats [12, 23], we found c-Fos positive cells in wider parts of the SCN, including its central area (See Fig. 1, Fig. 2, and Fig. 3). This seems to correspond to the wider distribution of retinal terminals in mice [1] than that in rats [22].

There is a positive correlation between the amounts of a light pulse-induced c-Fos expression and the behavioral phase-shifts [2, 8]. Moreover, application of antisense oligonucleotides against c-fos inhibits the light pulse-induced phase-shifts [26]. Here, we revealed that c-Fos induction in WT SCN was detected not only on day 1 but also on days 2–3. Thus, our present jet lag observation suggests that light exposure in every morning after LD phase-advance has a substantial effect on the promotion of reentrainment of the locomotor activity rhythm under jet lag condition, even though the effect on day 1 has the most significant effect since the number of c-Fos-positive cells are much greater than that of the rest of the days. Hence, it might be helpful for us to reduce jet lag symptoms if we have exposure to sunlight each morning when we go abroad.

V. Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

VI. Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST), Japan Science and Technology Agency (to H.O.), scientific grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (15H01843, 24240058, and 18002016 [to H.O.], and Innovative Areas [Brain Environment, 26111710] and 15H05642 [to Y.Y.]); and grants from Kobayashi International Scholarship Foundation and SRF (to H.O.), The Cell Science Research Foundation, Japan Foundation for Neuroscience and Mental Health, and Takeda Science Foundation (to Y.Y.).

VII. References

- 1.Abrahamson E. E. and Moore R. Y. (2001) Suprachiasmatic nucleus in the mouse: retinal innervation, intrinsic organization and efferent projections. Brain Res. 916; 172–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaulé C. and Amir S. (1999) Photic entrainment and induction of immediate-early genes within the rat circadian system. Brain Res. 821; 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buxton O. M., Cain S. W., O’Connor S. P., Porter J. H., Duffy J. F., Wang W., Czeisler C. A. and Shea S. A. (2012) Adverse metabolic consequences in humans of prolonged sleep restriction combined with circadian disruption. Sci. Transl. Med. 4; 129ra143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao R., Anderson F. E., Jung Y. J., Dziema H. and Obrietan K. (2011) Circadian regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience 181; 79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comperatore C. A. and Krueger G. P. (1990) Circadian rhythm desynchronosis, jet lag, shift lag, and coping strategies. Occup. Med. 5; 323–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hastings M. H., Maywood E. S. and Reddy A. B. (2008) Two decades of circadian time. J. Neuroendocrinol. 20; 812–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiessling S., Eichele G. and Oster H. (2010) Adrenal glucocorticoids have a key role in circadian resynchronization in a mouse model of jet lag. J. Clin. Invest. 120; 2600–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kornhauser J. M., Nelson D. E., Mayo K. E. and Takahashi J. S. (1990) Photic and circadian regulation of c-fos gene expression in the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuron 5; 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohawk J. A., Green C. B. and Takahashi J. S. (2012) Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 35; 445–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore R. Y. and Lenn N. J. (1972) A retinohypothalamic projection in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 146; 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moser M., Schaumberger K., Schernhammer E. and Stevens R. G. (2006) Cancer and rhythm. Cancer Causes Control 17; 483–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagano M., Adachi A., Nakahama K., Nakamura T., Tamada M., Meyer-Bernstein E., Sehgal A. and Shigeyoshi Y. (2003) An abrupt shift in the day/night cycle causes desynchrony in the mammalian circadian center. J. Neurosci. 23; 6141–6151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obrietan K., Impey S. and Storm D. R. (1998) Light and circadian rhythmicity regulate MAP kinase activation in the suprachiasmatic nuclei. Nat. Neurosci. 1; 693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pacesova D., Volfova B., Cervena K., Hejnova L., Novotny J. and Bendova Z. (2015) Acute morphine affects the rat circadian clock via rhythms of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and GSK3beta kinases and Per1 expression in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 172; 3638–3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy A. B., Field M. D., Maywood E. S. and Hastings M. H. (2002) Differential resynchronisation of circadian clock gene expression within the suprachiasmatic nuclei of mice subjected to experimental jet lag. J. Neurosci. 22; 7326–7330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rusak B., Robertson H. A., Wisden W. and Hunt S. P. (1990) Light pulses that shift rhythms induce gene expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Science 248; 1237–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sack R. L. (2009) The pathophysiology of jet lag. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 7; 102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sagar S. M., Sharp F. R. and Curran T. (1988) Expression of c-fos protein in brain: metabolic mapping at the cellular level. Science 240; 1328–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheer F. A., Hilton M. F., Mantzoros C. S. and Shea S. A. (2009) Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106; 4453–4458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz W. J., Carpino A. Jr., de la Iglesia H. O., Baler R., Klein D. C., Nakabeppu Y. and Aronin N. (2000) Differential regulation of fos family genes in the ventrolateral and dorsomedial subdivisions of the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience 98; 535–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi J. S., Hong H. K., Ko C. H. and McDearmon E. L. (2008) The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9; 764–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka M., Ichitani Y., Okamura H., Tanaka Y. and Ibata Y. (1993) The direct retinal projection to VIP neuronal elements in the rat SCN. Brain Res. Bull. 31; 637–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ubaldo-Reyes L. M., Buijs R. M., Escobar C. and Angeles-Castellanos M. (2017) Scheduled meal accelerates entrainment to a 6-hr phase advance by shifting central and peripheral oscillations in rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 46; 1875–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vargis E., Peterson C. B., Morrell-Falvey J. L., Retterer S. T. and Collier C. P. (2014) The effect of retinal pigment epithelial cell patch size on growth factor expression. Biomaterials 35; 3999–4004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welsh D. K., Takahashi J. S. and Kay S. A. (2010) Suprachiasmatic nucleus: cell autonomy and network properties. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72; 551–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wollnik F., Brysch W., Uhlmann E., Gillardon F., Bravo R., Zimmermann M., Schlingensiepen K. H. and Herdegen T. (1995) Block of c-Fos and JunB expression by antisense oligonucleotides inhibits light-induced phase shifts of the mammalian circadian clock. Eur. J. Neurosci. 7; 388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamaguchi Y., Suzuki T., Mizoro Y., Kori H., Okada K., Chen Y., Fustin J. M., Yamazaki F., Mizuguchi N., Zhang J., Dong X., Tsujimoto G., Okuno Y., Doi M. and Okamura H. (2013) Mice genetically deficient in vasopressin V1a and V1b receptors are resistant to jet lag. Science 342; 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamazaki S., Numano R., Abe M., Hida A., Takahashi R., Ueda M., Block G. D., Sakaki Y., Menaker M. and Tei H. (2000) Resetting central and peripheral circadian oscillators in transgenic rats. Science 288; 682–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]