Abstract

Background:

The use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) has grown worldwide, and there are concerns about increased unsubstantiated long-term use. The aim of the study was to describe the real-world use of PPIs over the past decade in an entire national population.

Methods:

This was a nationwide population-based drug-utilization study. Patterns of outpatient PPI use among adults in Iceland between 2003 and 2015 were investigated, including annual incidence and prevalence, duration of use, and dose of tablet used (lower versus higher), as well as the proportion of PPI use attributable to gastroprotection.

Results:

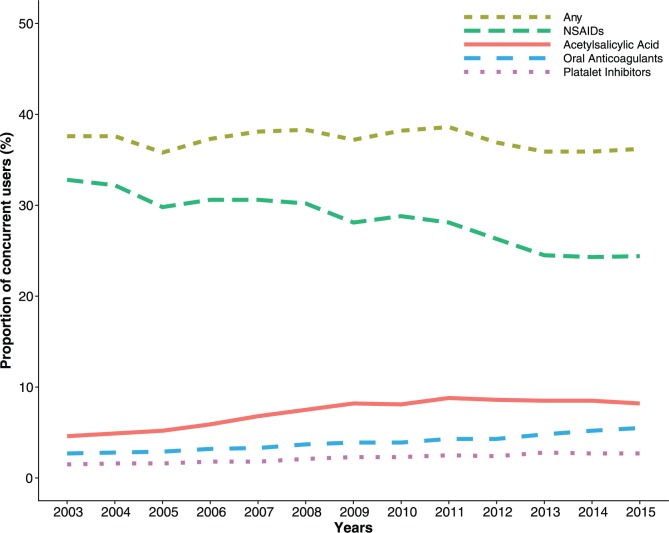

We observed 1,372,790 prescription fills over the entire study period, of which 95% were for higher-dose PPIs. Annual incidence remained stable across time (3.3–4.1 per 100 persons per year), while the annual prevalence increased from 8.5 per 100 persons to 15.5 per 100 persons. Prevalence increased with patient age and was higher among women than men. Duration of treatment increased with patients’ age (36% of users over 80 years remained on treatment after 1 year compared with 13% of users aged 19–39 years), and was longer among those initiating on a higher dose compared with a lower dose. The proportion of PPI users concurrently using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs decreased over the study period, while the proportion concurrently using acetylsalicylic acid, oral anticoagulants, or platelet inhibitors increased.

Conclusions:

In this nationwide study, a considerable increase in overall outpatient use of PPIs over a 13-year period was observed, particularly among older adults. Patients were increasingly treated for longer durations than recommended by clinical guidelines and mainly with higher doses.

Keywords: incidence, nationwide, pharmacoepidemiology, prevalence, proton-pump inhibitors, treatment duration

Introduction

Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) are commonly prescribed for several acid-related disorders,1 such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and peptic ulcer disease.2–5 These drugs are also effective in treating ulcers associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and as prophylactic treatment for patients on NSAIDs and low-dose aspirin.6–10 Recommended doses and duration of PPI treatment vary by indications. Clinical guidelines rarely recommend PPI treatment for more than 8–12 weeks.11,12 High-dose treatment is recommended when initiating therapy for GORD and peptic ulcer disease, while low-dose treatment is generally regarded as a maintenance therapy for recovering patients.12

PPIs are generally considered safe.13 However, their use has been associated with increased risks of adverse events, such as bone fractures,14 kidney disease,15 microscopic colitis,16 and hypomagnesemia.17 Use of PPIs has also been suggested to cause changes in the composition of the intestinal microbiota, increasing the risk of Clostridium difficile infection18 and chronic liver disease.19 Although PPIs have been shown to minimize NSAID-related adverse effects in the stomach, recent evidence suggests that PPIs might cause changes in the composition of the small intestinal microbiota, augmenting unwanted adverse effects of NSAIDs in the small intestines.20 Furthermore, discontinuation of PPI treatment has been linked to acid hypersecretion21 and the development of dyspeptic symptoms in healthy volunteers.22

PPIs have had undisputed effects on the treatment of symptoms related to excessive acid secretion, but concerns are growing about inappropriate indications and potential overuse, both within hospitals and in the primary-care setting.23–26 These concerns are compounded by observations of increased long-term use especially in elderly populations,27–29 where overprescribing has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality.30

In light of these concerns, we aimed to provide data on real-world use of PPIs, and changes thereof, across the past decade in an entire national population. Specifically, we aimed to determine patterns of use by patient and prescriber characteristics, including treatment duration contrasting between higher- and lower-dose PPIs. Furthermore, we described the proportion of PPI use attributable to gastroprotection.

Methods

This was an observational drug-utilization study describing the use of PPIs among the adult Icelandic population (19 years or older) during the period 1 January 2003 through to 31 December 2015.

Data sources

The Icelandic Medicines Registry (IMR) contains individual information on all dispensed prescription drugs in outpatient care in Iceland since 1 January 2003. We received information from the IMR on PPI dispensing during the study period. As of 2010, the IMR also contained information on dispensed prescription drugs within nursing homes in Iceland.31,32 Completeness of the IMR ranged from 91% to 98% of all dispensed prescription drugs for the study years. Information on wholesale statistics of PPIs was provided by the Icelandic Medicines Agency.33

The Icelandic Population Register provided information about all citizens, Icelandic and foreign, residing in Iceland during the study period, including data on month and year of birth, sex, residency at 1 January 2003, migration status, and date of death (if appropriate).

Using personal identification numbers, unique to every individual residing in Iceland, we linked together the variables from these two registries.

Study drugs

The drugs of interest were classified according to the World Health Organization anatomical therapeutic chemical/defined daily doses (ATC/DDD) classification.34 During the study period, four PPI substances were prescribed in Iceland: omeprazole (A02BC01), lansoprazole (A02BC03), rabeprazole (A02BC04), and esomeprazole (A02BC05). We further categorized each PPI type by available tablet strengths in milligrams as higher or lower dose. In the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guidelines, PPI doses (in mg) are defined as standard/full dose, double dose, or low dose.12 In the current study, standard and double doses were defined as higher-dose PPIs and low doses as lower-dose PPIs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Proton-pump inhibitors and tablet strengths dispensed to adults in Iceland in 2003–2015.

| PPI | ATC | DDD (mg) | Lower dose (mg)* | Higher dose (mg)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omeprazole | A02BC01 | 20 | 10 | 20, 40 |

| Lansoprazole | A02BC03 | 30 | 15 | 30 |

| Rabeprazole | A02BC04 | 20 | 10 | 20 |

| Esomeprazole | A02BC05 | 30 | 10 | 20, 40 |

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence clinical guidelines define PPI doses as standard/full dose, double dose or low dose.12 Here we categorize low PPI doses as lower-dose PPIs while standard and double doses are categorized as higher-dose PPIs. ATC, anatomical therapeutic chemical; DDD, defined daily dose, PPI, proton-pump inhibitor.

On 1 February 2009, PPIs became available as over-the-counter (OTC) products in Iceland. However, the majority of PPIs during the study period were obtained by prescription rather than OTC, with OTC sales ranging from 1% in 2009 to 10% in 2015 of the total dispensed DDDs in these years (Supplementary Table S1).

Information on the indication for the prescription of PPIs was not available in the IMR. We explored potential reasons for PPI use by assessing the proportion of use attributable to gastroprotection, that is, concurrent use of PPIs with acetylsalicylic acid (ATC codes: B01AC06, N02BA01, B01AC30), NSAIDs (ATC codes: M01, excluding M01AX), oral anticoagulants (ATC codes: B01AA, B01AE, B01AF, B01AX06), and platelet inhibitors (B01AC04, B01AC07, B01AC22, B01AC24, B01AC30).

Analysis

We presented overall use of PPIs in Iceland as the total number of dispensed DDDs to the adult population stratified by calendar year, PPI substance, and specialty of the prescribing physician (primary care, gastroenterology, and other specialties).

Annual prevalence (per 100 persons) of PPI use was defined as the number of adult individuals who filled at least one prescription in the relevant calendar year (2003–2015) divided by the total adult population residing in Iceland on 1 July of that year. Further we reported the sex- and age-specific prevalence of PPI use in 2015, the last year of the study period (by 1-year age intervals between ages 19–39 years and 80+ years). As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the analysis of annual prevalence requiring at least two filled PPI prescriptions in the relevant calendar year to be classified as a prevalent user.

Annual incidence (per 100 persons per year) of PPI use was defined as the number of adult individuals who, during the relevant calendar year (2005–2015), filled their first PPI prescription after a period of 24 months during which no PPI prescriptions were filled, divided by the total adult population residing in Iceland on 1 July of that year.

To describe the duration of PPI use we used the ‘proportion of patients covered’ method, which estimates the proportion of subjects that are alive and covered by treatment on a given day after the initiation of an incidence treatment episode. For each patient, we estimated duration of each filled prescription based on days’ supply, assuming one tablet as a daily dose. We allowed for a grace period of 108 days (2 × the median number of days between dispensing, that is, the number of days by which 50% of the population had received a subsequent dispensing), to account for irregular prescription fills and added to the duration of each prescription. If a patient did not fill a new prescription within this time we considered them to have discontinued their PPI treatment. They could then later re-enter the user population upon initiating a new treatment episode. We followed incident PPI users for 5 years, from the date of their first PPI prescription (day 0), and calculated the proportion of patients covered by dividing the number of users that were using the drug at day X (defined by 30-day intervals) by the number of people who were still alive and had not migrated at day X. Furthermore, to assess differences in treatment duration by patient age or by their prescribed PPI dose, we stratified the duration analysis by age (19–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80+ years), dose strength (higher versus lower), and sex. In addition, we explored the distribution in number of dispensed DDDs and tablets in the first 5 years after start of initial treatment episode (0–99, 100–199, 200–299, 300–399, 400–499, 500–599, 600–699, 700–799, 800–899, 900–999, ⩾ 1000).

To assess concurrent use of selected drugs (ATC codes: M01 [excluding M01AX], B01AC06, N02BA01, B01AC30, B01AA, B01AE, B01AF, B01AX06, B01AC04, B01AC07, B01AC22, B01AC24, and B01AC30), we calculated the proportion (%) of prevalent PPI users in each study year who also filled prescriptions for these drugs within 90 days leading up to a PPI prescription fill. To assess the pattern of concurrent use among different age groups we performed a stratified analysis by age (19–39, 40–64, 65+ years).

All analyses were performed using R version 3.4.235 and RStudio.36 The study was approved by the National Bioethics Committee in Iceland (study reference number: VSNb2015080004/03.03). As the study was based on national registry data, we did not obtain informed consent from individuals in the study population. All personal information was encrypted and de-identified prior to analysis.

Results

We observed 1,372,790 prescription fills for PPIs over the entire study period. The vast majority (95%) were higher-dose prescriptions. Among 313,296 individuals constituting our source population, a total of 101,909 (33%) filled at least one PPI prescription, including 56,252 women (55%) and 45,657 men (45%). The mean age at first prescription fill was 46 years (interquartile range 30–60). We observed a median of three PPI prescription fills per patient (interquartile range 1–15). The median number of days between prescription fills was 54.

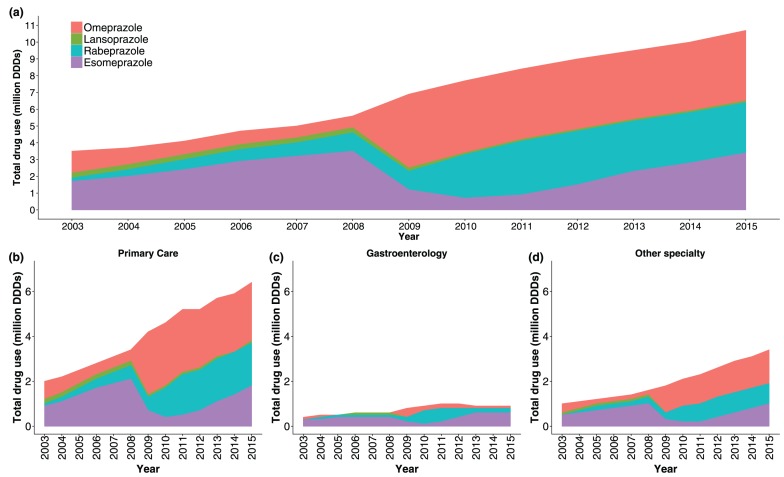

During the study period, there was an increase in total PPI use, measured as the number of dispensed DDDs, from 3.5 million DDDs dispensed in 2003 to 10.7 million DDDs dispensed in 2015 (Figure 1a). Primary-care physicians prescribed the majority (60%) of all dispensed DDDs during the study period, whereas gastroenterologists prescribed 11% and physicians of other specialties prescribed 29%. Prior to 2009, esomeprazole was the most commonly prescribed drug among all specialties. Although esomeprazole remained the PPI of choice among gastroenterologists, omeprazole became the most commonly prescribed PPI thereafter among nongastroenterologists (Figure 1b–d).

Figure 1.

Proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) use among adults in Iceland during 2003–2015, measured in million dispensed defined daily doses (DDDs). (a) Overall use by PPI type; (b–d) overall use by specialty of prescribing physician and PPI type.

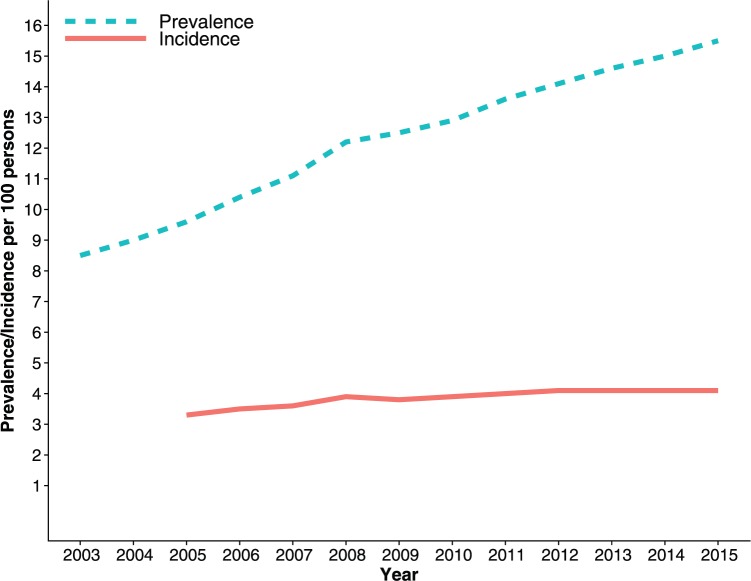

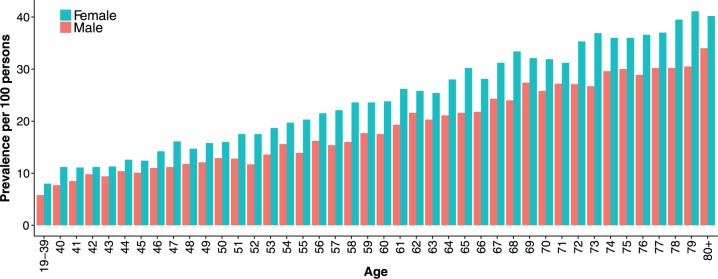

Figure 2 shows an increase in annual prevalence of PPI use with calendar time, from 8.5 per 100 persons in 2003 to 15.5 per 100 persons in 2015. Meanwhile, the incidence of PPI use ranged from 3.3 per 100 persons in 2005 to 4.1 per 100 persons in 2015. A more stringent measure of annual prevalence, requiring at least two prescription fills within a relevant year, yielded a prevalence of 5.4 per 100 persons in 2003 to 11.0 per 100 persons in 2015 (Supplementary Figure S1). Prevalence of PPI use was higher among women than men and increased with patient age (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Annual prevalence and incidence (per 100 persons) of proton-pump inhibitor use among adults in Iceland.

Figure 3.

Age- and sex-specific prevalence of proton-pump inhibitor use among adults in Iceland in 2015.

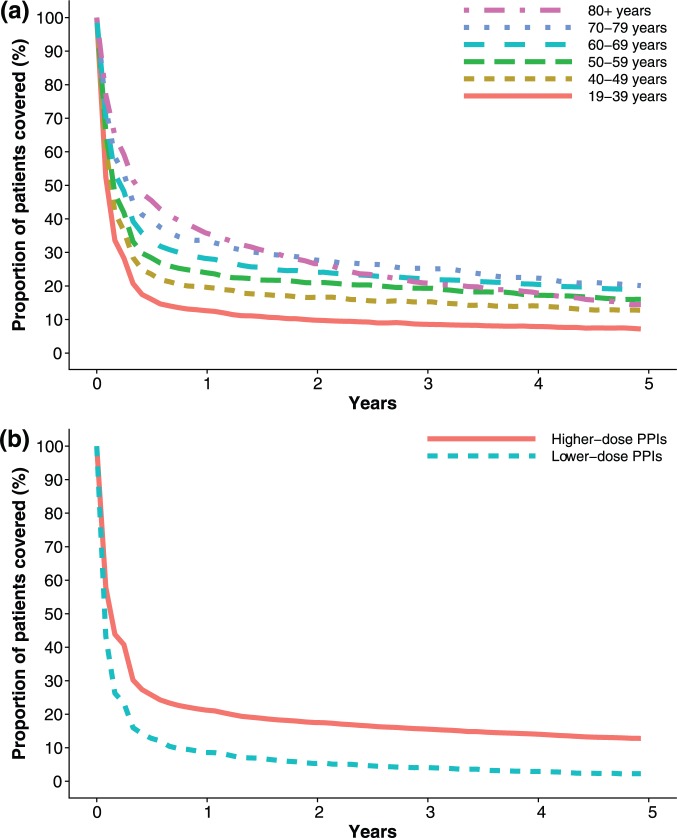

We identified 74,973 incident PPI users in our study population, which we then followed for 5 years to estimate the proportion of users still on treatment over time. Figure 4(a) shows the estimated treatment duration stratified by patient age. The proportion of patients still on PPI treatment after 1 year was highest among those over 80 years of age, (36%) and lowest in those aged 19–39 years (13%). After 5 years, the proportion was highest in those aged 70–79 years (20%) and lowest among the youngest, 19–39 years (7%). The majority of patients filled fewer than 200 DDDs/tablets during the first 5 years after starting PPI treatment (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 4.

Duration of PPI treatment among incident users: (a) by age; (b) by initial dose strength of the proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), measured as the proportion of patients covered.

Figure 4(b) shows PPI treatment duration among incident PPI users stratified by strength of PPI dose at treatment initiation. Of the 74,973 incident users, 70,720 (94%) initiated on higher-dose PPIs and 4240 (6%) on lower-dose PPIs. The proportion of patients still treated with the same dose after 1 year was greater among those prescribed higher- (21%) than lower-dose PPIs (9%). The proportion of patients still on the same dose was 13% versus 2% after 5 years, respectively on higher- versus lower-dose PPIs. Duration of treatment by PPI dose strength was nearly identical for both sexes (Supplementary Figure S3).

We observed a slight decrease in the proportion of PPI users concurrently using drugs that have been shown to be ulcerogenic or increase the risk of bleeding, from 38% in 2003 to 36% in 2015 (Figure 5). The proportion of PPI users concurrently using NSAIDs decreased from 33% in 2003 to 24% in 2015. We observed an increase in concurrent use of oral anticoagulants (3–6%), acetylsalicylic acid (5–8%), and other platelet inhibitors (2–3%). The proportion of PPI users concurrently treated with any of these four drugs was highest among those aged over 65 years (47% in 2003, 47% in 2015) and lowest among the youngest aged 19–39 years (21% in 2003, 17% in 2015) (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 5.

Concurrent use of proton-pump inhibitors with drugs that are ulcerogenic or increase the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Discussion

In this study, which covered all PPI dispensing in an entire national population over 13 years, we observed widespread and increasing use of PPIs, especially among the elderly. Primary-care physicians prescribed the vast majority of dispensed PPIs in our study data. While the number of new users remained relatively stable over time, the results suggested that patients were increasingly treated for longer durations than recommended by clinical guidelines and mainly with higher-dose PPIs.

The rising prevalence of PPI use across time observed in our study is in line with recently published reports in comparable populations.27,29,37 However, the prevalence in Iceland in 2015 was more than twice that observed among adults in Denmark in 2014 (15.5% versus 7.4%). GORD is the most common indication for PPIs with an estimated prevalence of 9–26% in European populations.38 Although our use estimates were within this range, we were unable to draw definitive conclusions on the appropriateness of PPI use in Iceland as we did not have information on the indications for which PPIs were prescribed nor data on the prevalence of GORD or other underlying conditions in the population.

Inappropriate use of PPIs in the outpatient setting, for example, in the form of inappropriate indications and automatic renewal of prescriptions without re-evaluation of patients’ symptoms, is a looming concern.25,39 Such concerns were reinforced by Reimer and Bytzer’s findings, which showed that only 27% of people receiving long-term treatment had a verified diagnosis justifying the need for long-term treatment.40 The NICE clinical guidelines recommend long-term PPI therapy for rare conditions like Zollinger–Ellison syndrome or Barrett’s esophagus as well as for patients with severe esophagitis, who have not responded to an initial high-dose 8-week treatment, and for patients who have experienced a dilation of an esophageal stricture.12 In general, the recommended duration of PPI treatment in clinical guidelines rarely exceeds 12 weeks. We found that 22% remained on treatment 1 year after treatment initiation. The proportion was highest among the oldest age group (36%) and lowest among the youngest (13%). Extended treatment durations among older adults are concerning in light of widespread polypharmacy and increased risk of adverse events with PPI use.41 In fact, we observed that nearly half of older adults in our data used PPIs concurrently with NSAIDs, acetylsalicylic acid, oral anticoagulants, or platelet inhibitors, reflecting the level of polypharmacy among older adults using PPIs. Given the recent evidence of PPIs potentially facilitating injurious effects of NSAIDs in the small intestines, especially in older people and other high-risk patients,20 this pattern of high concurrent drug use might be concerning. However, as we were unable to link prescription data with clinical information, we cannot rule out that these patients were appropriately prescribed PPIs as bleeding prophylaxis.

The vast majority of PPI users in our population initiated treatment with higher-dose PPIs and after 1 year 21% remained on that treatment, for example, had not switched to lower-dose PPIs or discontinued treatment. This might indicate that their underlying symptoms are more severe than among those initiating treatment on lower doses and reflect the level of difficulty some users experience when discontinuing treatment due to resurfacing symptoms.42

Recently, Helgadottir and colleagues demonstrated that among confirmed GORD patients on long-term PPI treatment, women were more likely than men to be able to lower their dose by half, while still achieving symptom relief.43 In our study we found no observable difference in treatment durations by patient sex, nor did women seem more likely to initiate or maintain treatment on lower-dose PPIs. Thus, it is conceivable that women might be able to tolerate lower PPI doses than is mostly used nowadays.

The present study has several limitations. First, as with all register-based drug studies, it is not certain that individuals who filled the PPI prescriptions actually consumed the drugs. To address this, we performed a sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Figure S1) requiring at least two PPI prescription fills within a year to count as a prevalent PPI user, which resulted in lowered prevalence estimates. Actual consumption might thus in reality lie between these two measures of prevalence. Second, the study data did not contain information on clinical characteristics such as indications underlying the PPI prescriptions and/or the severity of symptoms, which prevented us from drawing sound conclusions on the appropriateness of PPI prescribing in our population. Third, information on PPI use within nursing homes was not included in the IMR until 2010, which presumably resulted in an underestimation of the prevalence of PPI use among the elderly in the first half of the study period. Fourth, information on exact dosing for each prescription was not available in our data preventing us from accurately assessing prescribed doses. Our assessments of PPI doses were based on dispensed tablet strengths and therefore only an approximation of actual doses. Finally, PPIs became available OTC on 1 February 2009. However, the proportion of PPIs sold OTC was relatively low, ranging from 1% to 10% of the total number of DDDs sold annually from 2009 to 2015, and may therefore only have led to a slight underestimation of overall PPI use.

In conclusion, over a 13-year follow-up period we observed a considerable increase of real-world PPI use in a nationwide population setting, particularly among older adults. We found that a number of patients stayed on PPI treatment for longer periods than is recommended by clinical guidelines, mainly on higher doses. In view of these results, further initiatives towards appropriate prescribing of PPIs, especially in terms of the adoption of de-prescribing strategies, are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material, supplementary_material for Proton-pump inhibitors among adults: a nationwide drug-utilization study by Óskar Ö. Hálfdánarson, Anton Pottegård, Einar S. Björnsson, Sigrún H. Lund, Margret H. Ogmundsdottir, Eiríkur Steingrímsson, Helga M. Ogmundsdottir and Helga Zoega in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology

Acknowledgments

We thank Guðrún Kristín Guðfinnsdóttir and Kristinn Jónsson at the Directorate of Health in Iceland for extracting the data for this study. HZ is the guarantor of the article. ÓÖH and HZ designed the study. ÓÖH, HZ, AP, and SHL contributed to the data analysis and all authors contributed to the interpretation of the data. ÓÖH drafted the manuscript and all authors participated in the interpretation of the data and revision of the content of the manuscript. The final version of the manuscript was revised and approved by all authors.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by the University of Iceland Research Fund, grant number HI16090004, and by the Icelandic Research Fund, grant number 152715-053.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

ORCID iD: Óskar Örn Hálfdánarson  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4564-6126

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4564-6126

Contributor Information

Óskar Ö. Hálfdánarson, Centre of Public Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Sturlugata 8, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland.

Anton Pottegård, Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacy, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

Einar S. Björnsson, Department of Internal Medicine, The National University Hospital of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland, and Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland

Sigrún H. Lund, Centre of Public Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland

Margret H. Ogmundsdottir, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland

Eiríkur Steingrímsson, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland.

Helga M. Ogmundsdottir, Cancer Research Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland

Helga Zoega, Centre of Public Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland, and Medicines Policy Research Unit, Centre for Big Data Research in Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

References

- 1. Raghunath AS, Hungin AP, Mason J, et al. Symptoms in patients on long-term proton pump inhibitors: prevalence and predictors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 29: 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, et al. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut 2005; 54: 710–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lundell L, Miettinen P, Myrvold HE, et al. Comparison of outcomes twelve years after antireflux surgery or omeprazole maintenance therapy for reflux esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 1292–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mahon D, Rhodes M, Decadt B, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication compared with proton-pump inhibitors for treatment of chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux. Br J Surg 2005; 92: 695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mehta S, Bennett J, Mahon D, et al. Prospective trial of laparoscopic nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitor therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease: seven-year follow-up. J Gastrointest Surg 2006; 10: 1312–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scheiman JM. The use of proton pump inhibitors in treating and preventing NSAID-induced mucosal damage. Arthritis Res Ther 2013; 15: S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS, et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on clinical expert consensus documents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52: 1502–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gómez-Outes A, Terleira-Fernández AI, Calvo-Rojas G, et al. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban versus warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of subgroups. Thrombosis 2013; 2013: 640723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hreinsson JP, Kalaitzakis E, Gudmundsson S, et al. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: incidence, etiology and outcomes in a population-based setting. Scand J Gastroenterol 2013; 48: 439–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hreinsson JP, Palsdóttir S, Bjornsson ES. The association of drugs with severity and specific causes of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a prospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016; 50: 408–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 308–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. NICE. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management, guidance and guidelines, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg184 (accessed 22 November 2017). [PubMed]

- 13. McCarthy DM. Adverse effects of proton pump inhibitor drugs: clues and conclusions. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010; 26: 624–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhou B, Huang Y, Li H, et al. Proton-pump inhibitors and risk of fractures: an update meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2016; 27: 339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176: 238–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Law EH, Badowski M, Hung YT, et al. Association between proton pump inhibitors and microscopic colitis. Ann Pharmacother 2017; 51: 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Kittanamongkolchai W, et al. Proton pump inhibitors linked to hypomagnesemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ren Fail 2015; 37: 1237–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Naito Y, Kashiwagi K, Takagi T, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis secondary to proton-pump inhibitor use. Digestion 2018; 97: 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Llorente C, Jepsen P, Inamine T, et al. Gastric acid suppression promotes alcoholic liver disease by inducing overgrowth of intestinal Enterococcus. Nat Commun 2017; 8: 837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marlicz W, Łoniewski I, Grimes DS, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitors, and gastrointestinal injury: contrasting interactions in the stomach and small intestine. Mayo Clin Proc 2014; 89: 1699–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Waldum HL, Qvigstad G, Fossmark R, et al. Rebound acid hypersecretion from a physiological, pathophysiological and clinical viewpoint. Scand J Gastroenterol 2010; 45: 389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Niklasson A, Lindström L, Simrén M, et al. Dyspeptic symptom development after discontinuation of a proton pump inhibitor: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1531–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naunton M, Peterson GM, Bleasel MD. Overuse of proton pump inhibitors. J Clin Pharm Ther 2000; 25: 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grant K, Al-Adhami N, Tordoff J, et al. Continuation of proton pump inhibitors from hospital to community. Pharm World Sci 2006; 28: 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Batuwitage BT, Kingham JG, Morgan NE, et al. Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in primary care. Postgrad Med J 2007; 83: 66–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ladd AM, Panagopoulos G, Cohen J, et al. Potential costs of inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors. Am J Med Sci 2014; 347: 446–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wallerstedt SM, Fastbom J, Linke J, et al. Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors and prevalence of disease- and drug-related reasons for gastroprotection – a cross-sectional population-based study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2017; 26: 9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moriarty F, Bennett K, Cahir C, et al. Characterizing potentially inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in older people in primary care in Ireland from 1997 to 2012. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016; 64: e291–e296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pottegård A, Broe A, Hallas J, et al. Use of proton-pump inhibitors among adults: a Danish nationwide drug utilization study. Ther Adv Gastroenterol 2016; 9: 671–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cahir C, Fahey T, Teeling M, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and cost outcomes for older people: a national population study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010; 69: 543–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Furu K, Wettermark B, Andersen M, et al. The Nordic countries as a cohort for pharmacoepidemiological research. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2010; 106: 86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Embætti Landlæknis. Lyfjagagnagrunnur landlaeknis Hlutverk-og-rekstur, https://www.landlaeknir.is/servlet/file/store93/item27765/Lyfjagagnagrunnur_landlaeknis_Hlutverk-og-rekstur_loka_14.10.15.pdf (accessed 22 November 2017).

- 33. Lyfjastofnun. Icelandic Medicines Agency, https://www.ima.is (accessed 13 April 2018).

- 34. WHOCC. ATC/DDD Index, https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ (accessed 6 November 2017).

- 35. The R Foundation. The R project for statistical computing, https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed 6 November 2017).

- 36. RStudio. Open source and enterprise-ready professional software for R, https://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed 6 November 2017).

- 37. Ksiądzyna D, Szeląg A, Paradowski L. Overuse of proton pump inhibitors. Pol Arch Intern Med 2015; 125: 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, et al. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut 2014; 63: 871–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Heidelbaugh JJ, Kim AH, Chang R, et al. Overutilization of proton-pump inhibitors: what the clinician needs to know. Ther Adv Gastroenterol 2012; 5: 219–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reimer C, Bytzer P. Clinical trial: long-term use of proton pump inhibitors in primary care patients – a cross sectional analysis of 901 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 30: 725–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maes ML, Fixen DR, Linnebur SA. Adverse effects of proton-pump inhibitor use in older adults: a review of the evidence. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2017; 8: 273–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Björnsson E, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M, et al. Discontinuation of proton pump inhibitors in patients on long-term therapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 24: 945–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Helgadóttir H, Metz DC, Lund SH, et al. Study of gender differences in proton pump inhibitor dose requirements for GERD: a double-blind randomized trial. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017; 51: 486–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material, supplementary_material for Proton-pump inhibitors among adults: a nationwide drug-utilization study by Óskar Ö. Hálfdánarson, Anton Pottegård, Einar S. Björnsson, Sigrún H. Lund, Margret H. Ogmundsdottir, Eiríkur Steingrímsson, Helga M. Ogmundsdottir and Helga Zoega in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology