Abstract

Social determinants of health (SDOH) have an important role in diagnosis, prevention, health outcomes, and quality of life. Currently, SDOH information in electronic health record (EHR) systems is often contained in unstructured text. The objective of this study is to examine an important subset of SDOH documentation for Residence, Living Situation and Living Conditions in an enterprise EHR informed by previous model representations. In addition to two publically available clinical note sources, notes created by Social Work, Physical Therapy, and Occupational Therapy, along with free text Social Documentation entries were reviewed. Sentences were classified, annotated, and evaluated once mapped to element entities and attributes. Overall, 2,491 total notes yielded 616, 813, and 30 sentences related to Residence, Living Situation, and Living Conditions. This study demonstrated the need for additional elements in the model representation, more representative values and content culminating in a more comprehensive model representation for these key SDOH.

Introduction and Background

Social and individual behavioral factors play an important role in diagnosis, prevention, health outcomes, and quality of life.1,2 As defined by the World Health Organization, “social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age”.3 Social determinants of health (SDOH) can cause illness, exacerbate or contribute to chronic illness, and conversely can also improve health.

Previous studies have demonstrated the deleterious effect of behaviors such as alcohol and tobacco use on health outcomes.4-7 Housing has also been relatively well studied, especially the impact of homelessness on various conditions.8-14 Other housing conditions have been correlated with health outcomes. Residential status, specifically housing instability, has been studied in relation to outcomes in certain disease or treatment groups, and found to be a risk for poor outcomes.8-10 It overall appears that there is a complex interconnectedness between poor housing and poor health.15 Costa-Font found that owning a home, or housing equity overrides the effect of income as a determinant of health and (absences) of disability in old age.12 In contrast, permanent supportive housing can addresses homelessness and health disparities.16 This is also some evidence that improving housing can contribute to improved health.17 For example, Jacobs et al. found evidence that specific housing interventions can improve certain health outcomes.18

However, other aspects of social determinants related to Residence, Living Situation, and Living Conditions have not been investigated as thoroughly. For example, the impact of housing type (Residence) such as single family home, assisted living, group living situations, has not been investigated. Studies have also shown that certain housing models can be beneficial to specific patient groups.14,19 In addition, significant exposures risks have been associated with indoor environments.20,21 For example, with multi-unit dwellings there is risk of exposure to hazards such as second-hand smoke as smoke can seep into neighboring units resulting in involuntary exposure.22 Knowledge of a patient’s physical living space, type of dwelling, stairs, safety mechanisms, etc. could be of benefit to the clinician or therapist in providing care to that patient and obtaining the proper support in further promoting their wellness.

With whom a patient lives (Living Situation) as well as the conditions (Living Conditions) under which they live also have heath implications. While living with others creates a support network for the patient, housing density increases exposure to communicable diseases, causes stress in adults and poor long-term health in both children and adults.23

The increase in the use of EHRs provides unprecedented opportunity to collect and analyze SDOH information in conjunction with clinical data in secondary use for research and process improvement. SDOH information can be used in a myriad of ways from health outcomes evaluations to predictive modeling for prevention. The National Academy of Medicine has completed a consensus study on social determinants in the EHR.24,25 The Committee on Recommended Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures for Electronic Health Records has identified domains and measures that capture the social determinants of health to inform the development of recommendations for Stage 3 meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs). The NAM final report recommended documentation of race and ethnicity, education, financial resource strain, stress, depression, physical activity, tobacco use and exposure, alcohol use, social connections and social isolation, exposure to violence (intimate partner violence), and neighborhood and community compositional characteristics. The final recommendations unfortunately did not include Residence, Living Situation, or Living Conditions.

Currently, comprehensive documentation standards for many SDOH do not exist.26 As a result, EHR systems and their associated user interfaces are not optimized for the consistent collection of discrete social history information leaving this important information often buried in free text notes or as unstructured text fields in the social history sections of the EHR. Natural language processing techniques are being developed that allow us to extract social history information from the notes and into discrete datasets but primarily only around substance use information which has more developed and robust information models providing a “target” for discrete representation.27,28

The overall goal of this study is to evaluate documentation of three SDOH topic areas (Residence, Living Situation, and Living Conditions) using publically available note sources and Enterprise EHR free text documentation. This work also builds from work of Chen et al. and Melton et al. to model social history from progress notes and public health surveys, including living situation, residence, social support, and occupation.29 Other previous work to harmonize interface terminologies, standards, specifications, coding terminologies, vocabularies, documentation guidelines, measures, and surveys provides a model representation of our three topic areas.26 This study also further refines the model representation of Residence, Living Situation, and Living Conditions informed by additional interdisciplinary EHR system content.

Methods

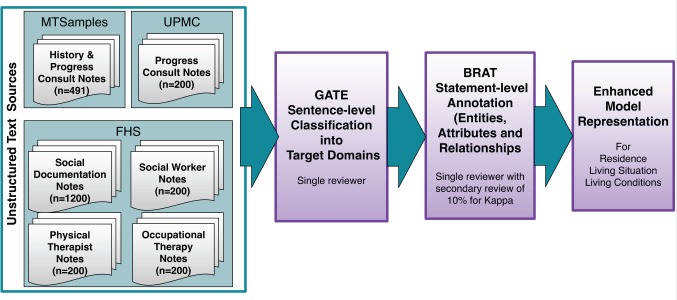

This study is focused on the three topic areas Residence, Living Situation, and Living Conditions. Clinical notes from three sources were evaluated. Individual sentences related to the topic areas were identified and were classified, into one or more of the target topic areas. Lastly, statement-level annotation was performed, with a 10% secondary review for Kappa, and elements were mapped to generate a model representation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of Methods.

Topic areas: Using definitions developed from previous work, Residence describes dwelling types, physical residence, and geographic location and includes safety considerations such as railings or number of floors and steps.26 Living Situation describes with whom the patient lives such as roommates, family members, multi-resident dwelling as well as how many others they live with. Lastly, Living Conditions describes environmental cleanliness and precautions against infection and disease and includes such things as animals, and presence of mold or an unclean living space

Data Sources: The data sources utilized for this work were: 1) MTSamples.com (MTS), a publicly accessible clinical note data source; 2) University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) NLP Repository with de-identified clinical notes (following execution of a data use agreement for research); and 3) multiple sources of data from the University of Minnesota-affiliated Fairview Health Services (FHS) electronic health record system.30 Overall, there were 491 history and physical and consult notes from MTS and 200 history and physical and consult notes from the UPMC included.30 The majority of clinical data for the study otherwise originated from the FHS EHR system through the University of Minnesota Academic Health Center Information Exchange (AHC-IE) data repository. We included only patients who had consented for their medical records to be used in research with inpatient encounters in 2013. For the purposes of this study to also obtain a broader understanding of documentation of this information by non-provider clinicians including several inter-disciplinary fields, we randomly selected 200 random progress notes authored by social workers, 200 progress notes authored by physical therapists, and 200 progress notes authored by occupational therapists, as well as 1,200 social documentation notes. Social Documentation is a portion of the Social History section in the EHR composed of a single free text field that can be documented on by any EHR clinical user.

Annotation Guidelines Development: Guidelines for sentence-level annotation were developed through literature review and included 28 classifications covering most social determinants of health. Related to this work, of those 28, 7 classifications were further analyzed for this study which included: Residence, Residence Exposure, Residence Other, Living Condition, Living Situation, Living Situation Exposure, and Living Situation Other.

Guidelines for statement-level annotations were developed through previous work reviewing existing standards and terminologies.26 Separate schemas were developed for each of the three topic areas (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Residence Annotation Guidelines Entities, Attributes and Relationships.

| Entities (27) | Attributes (16) |

|---|---|

|

|

Table 2.

Living Situation Annotation Guidelines Entities, Attributes and Relationships.

| Entities (21) | Attributes |

|---|---|

|

|

Table 3.

Living Condition Annotation Guidelines Entities, Attributes and Relationships.

| Entities (21) | Attributes (13) |

|---|---|

|

|

Sentence-level Annotation

All notes were initially reviewed and sentence-level annotation was performed by a single reviewer using General Architecture for Text Engineering (GATE) to identify and classify sentences related to the three topic areas of Residence, Living Situation, and Living Conditions.31 Sentences containing information related to more than one of the three topic areas were classified into each appropriate topic for statement-level annotation. For example, the sentence “He lives in <city name> with his mother and step-father” was classified as both Residence (“lives in <city name>) and Living Situation (“lives… with his mother and step-father). Table 4 shows example statements for each topic area.

Table 4.

Example sentences classified into each topic area.

| Topic Area | Example Sentences |

|---|---|

| Residence |

|

| Living Situation |

|

| Living Conditions |

|

Statement-level Annotations

Statement-level annotation was performed on the classified sentences using the brat rapid annotation tool (brat) to identify elements, attributes and relationships.32 The schema was modified iteratively to accommodate newly found elements and attributes for three sustentative iterations to include subject and temporal entities not previously encountered to ensure a stabilized schema. The original Residence annotation schema was amended to include “Subject”, “Time Point”, and “Time Frame”. The Living Situation schema was amended to include one new element “Current Age” that refers to the age of the persons with whom the patient lives. And the Living Conditions schema was amended to include the element “Living Conditions Detail Subtype” which refers to the subcategory of type.

The statement-level brat annotations was performed by a single reviewer and a subset of 10% of sentences were annotated by a second reviewer to ensure internal consistency and to assess inter-rater reliability. Values sets were compiled from the annotations for each entity found in the data sources as were schema amendments. The model representations from previous work26 were then amended with additional elements from this analysis to create and enhanced model representation of Residence, Living Situation, and Living Conditions (Tables 6A, B, C).

Table 6A,B,C.

Elements, counts, and example values/patterns Residence, Living Situation, and Living Conditions. For each source n= the total number of unique sentences that we eventually annotated for distinct elements. Percent of unique sentences that contained the element (Total number of instances of that element). Example values and patterns in bold are newly added to the existing model as a result of this work. Bolded Example Values represent items added to the existing model through this study.

| Table 6A. Residence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements | MTS (n=36) | UPMC (n=42) | FHS (n=504) | Total (n=581) | Example Values and Patterns |

| Status | 65.7%(30) | 76.2% (35) | 58.3% (351) | 60.1% (416) | lives in, resides in, homeless <ownership status> lives, live, living, moved, resides, residing, lived, staying, built, buying, came |

| Subject | 2.9% (1) | - | 0.8% (5) | 0.9% (6) | mother’s, in-laws, friends, daughter and son-in-law, <family member> |

| Negation | - | - | 0.2% (1) | 0.2% (1) | no <residence detail>, don’t |

| Certainty | 2.9% (1) | - | 0.4% (2) | 0.5% (3) | yes/present, no/absent, unknown, didn’t know, apparently |

| Quantity | - | - | 0.2% (1) | 0.2% (1) | <#> steps, <#> floors/levels <#> residence detail, several, <#> |

| Temporal | 14.3% (6) | 7.1% (3) | 6.9% (40) | 7.4% (49) | currently, prior to hosp, recently, now |

| Duration | 8.6% (3) | - | 1.6% (9) | 1.9% (12) | <#> years, <#> months, <#> days, few weeks/years |

| Duration Since Time Point | 2.9% (1) | - | 1.2% (6) | 1.2% (7) | Since <year>, end of <month>, after <medical incident> |

| End Date | - | - | 0.2% (1) | 0.2% (1) | <date> |

| Residence Age | - | - | 1.2% (7) | 1.0% (7) | New, newer, 10-25 years, built before 1950 |

| Residence Build Time Point | - | - | 0.6% (3) | 0.5% (3) | <date> |

| Start Age | - | - | 0.2% (1) | 0.2% (1) | <age> |

| Start Date | - | - | 1.2% (6) | 1.0% (6) | Summer, <year>, <MM/YYYY>, <DD/MM/YYYY> |

| Residence Type | 45.7% (17) | 76.2% (36) | 50.2% (306) | 51.8% (359) | house, apartment, nursing home, mobile home, <dwelling type>, home, assisted living, house. townhome, group home, condominium, senior housing |

| Residence Subtype | 5.7% (2) | 9.5% (4) | 4.2% (21) | 4.6% (27) | Multi-level, level, story, bedroom, floor, split-level |

| Residence Detail | 5.7% (2) | 2.4% (1) | 2.2% (12) | 2.4% (15) | own/rent safety devices, stairs, appliances, carpeted, independent, living, rear entry, basement |

| Residence Name | 11.4% (5) | 7.1% (4) | 4.0% (23) | 4.6% (32) | <facility name> |

| Geographic Location | 8.6% (3) | - | 2.6% (14) | 2.8% (17) | <general geographic location>, campus, locally, nearby, community, up here, there, here |

| Location Detail | 42.9% (18) | 14.3% (7) | 40.1% (277) | 38.4% (302) | Specific geographic <country> <state> <neighborhood> <zip> <street address> |

| Other | - | - | - | - | - |

| Table 6B. Living Situation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements | MTS (n=96) | UPMC (n=53) | FHS (n=665) | TOTAL (n=814) | Example Values and Patterns |

| Status | 90.6% (100) | 96.2% (53) | 86.9% (670) | 88.0% (823) | lives, lives with, live, living, resides, residing, visiting, lived, moving in, moved, stay, staying |

| Subject | 26.0% (27) | 22.6% (12) | 37.3% (293) | 35.0% (332) | spouse, parents, mother, father, child, roommate, family, <Family member> alone, child, <name>, boyfriend, significant other, roommate |

| Negation | 1.0% (1) | - | 0.5% (3) | 0.5% (4) | no <subject> <living situation detail>, do not, don’t, not, no |

| Certainty | 2.1% (2) | - | - | 0.2% (2) | yes/present, no/absent, unknown, apparently, either |

| Quantity | 6.3% (7) | 3.8% (3) | 3.9% (32) | 4.2% (42) | <#> subjects <#> in household |

| Temporal | - | - | 0.2% (1) | 0.1% (1) | Every other week |

| Duration | 1.0% (1) | - | 0.3% (2) | 0.4% (3) | Few weeks, <##> years |

| Duration Since Time Point | - | - | 0.3% (2) | 0.2% (2) | Approximately, past several years |

| End Date | - | - | 0.2% (1) | 0.1% (1) | <MM/YY> |

| Timeframe | 7.3% (8) | 5.7% (3) | 3.5% (28) | 4.1% (39) | Currently, previously, prior to hospitalization, recently |

| Time Point | 2.1% (2) | - | 1.1% (8) | 1.1% (10) | <MM/DD/YY>, <YYYY>, this week, now, |

| Living Situation Detail | 4.2% (4) | 5.7% (4) | 2.6% (20) | 2.9% (28) | inadequate, crowded, alone, privacy, together, independently, foster care |

| Family Member | 65.6% (104) | 75.5% (50) | 68.7% (817) | 68.8% (971) | Wife, brother, Child (ren), dad, daughter, father, husband, mom, mother |

| Side of Family | - | - | 0.2% (1) | 0.1% (1) | maternal |

| Current Age | 8.3% (13) | - | 3.0% (26) | 3.4% (39) | <##> year old, age <##> years, |

| Other | - | - | - | - | - |

| Table 6C. Living Conditions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | MTS (n=0) | UPMC (n=5) | FHS (n=33) | Total (n=38) | Example Values and Patterns |

| Status | - | 40.0% (2) | 12.1% (4) | 15.8% (6) | housing contains, lives, no, live, living |

| Subject | - | - | 24.2% (16) | 21.1% (16) | patient, <family member,> |

| Negation | - | 40.0% (2) | 24.2% (10) | 26.3% (12) | no <living condition detail>, without |

| Certainty | - | 20.0% (1) | 3.0% (2) | 5.3% (3) | yes/present, no/absent, unknown, apparently |

| Quantity | - | 20.0% (1) | 15.2% (8) | 15.8% (9) | Excessive animals <#> Living conditions type, good deal |

| Temporal | - | - | - | - | - |

| Living Conditions Detail | - | 20.0% (1) | 12.1% (6) | 13.2% (7) | water damage, home smelled of urine |

| Living Conditions Type | - | 40.0% (9) | 48.5% (30) | 47.4% (39) | mold, insects, rodents, animals, water, heat, well water, filtered water, city water, condemned, electricity, excrement, light, water fluorinated |

| Living Conditions Type Subtype | - | 20.0% (1) | 3.0% (1) | 5.3% (2) | Modifier of Living Conditions Type, unhygienic, presence of laundry facilities |

| Other | - | - | - | - | - |

Results

In total, 2,491 notes were reviewed by two reviewers, resulting in 1,459 sentences classified into the three topic areas of Residence, Living Situation, and Living Conditions. The initial classification analysis resulted in 616 sentences categorized as Residence, 813 sentences categorized as Living Situation, and 30 sentences categorized as Living Conditions (Table 5). MTSamples, FHS Physical Therapy, and FHS Occupational Therapy notes did not have any sentences that could be classified under the Living Conditions topic.

Table 5.

Number of notes reviewed and number of sentences classified. (*Total number of sentences are not mutually exclusive)

| Data Source | Total Notes | Sentences Classified | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | Living Situation | Living Conditions | Total Sentences* | |||

| MT Samples | 491 | 36 | 88 | 0 | 124 | |

| UPMC | 200 | 42 | 54 | 5 | 101 | |

| FHS | Social History Documentation Notes | 1200 | 296 | 453 | 24 | 773 |

| Social Worker Notes | 200 | 88 | 64 | 1 | 153 | |

| Physical Therapist Notes | 200 | 98 | 86 | 0 | 184 | |

| Occupational Therapist Notes | 200 | 56 | 68 | 0 | 124 | |

| Total sentences reviewed | 2491 | |||||

| Total number of sentences classified* | 616 | 813 | 30 | 1459 | ||

The statement-level annotation yielded an inter-rater reliability of K= 0.84% and proportion agreement of 0.98%. Overall the FHS set of notes were the most comprehensive and this had the highest contribution to this work. In totality, the 616 sentences or statements for Residence yielded significant contributions to the overall model. Of these sentences, Status was documented in 60.1% (416) of sentences, Residence Type 51.8% (359), and Geographic Location Detail (i.e., specific city, state country locations) in 38.4% (302) (Table 6A). Temporal elements were present but to a much lower degree.

For Living Situation, a total of 813 sentences were analyzed and, as with Residence, Status was highly prevalent being present 823 times and in total there were 1303 references to Subject other than patient or family member (Table 6B).

For Living Conditions in the 30 sentences were annotated, Living Condition Type was the most prevalent entity found with 39 instances with many sentences referencing more than one Living Condition Type per sentence, followed by subject being found 16 times (Table 6C).

Discussion

While social determinants of health (SDOH) play an important role in the provision of patient care, they also play an important role in secondary use of data for research and quality improvement. Unfortunately, SDOH information is not well documented as discrete data in the EHR. By leveraging a diverse collection of notes including general social history documentation notes and notes authored by different types of clinical authors our evaluation helps information about the three topic areas of Living Situation, Residence, and Living Conditions. By far, Living Situation was the most common topic found of the three topic areas followed by Residence with much less information around Living Conditions in our dataset. The prevalence of documentation related to Living Situation appears to be an effort by clinicians to indicate the relative amount of potential social support for patients.

Many sentences included elements that crossed topic areas. For example, “She lives in <CITY NAME> with her parents and 2 older sisters.”, which includes Residence and Living Situation. Another example: “Lives at home with mom and two pets.”, crosses all three topic areas. Not surprisingly, physical therapist and social worker authored notes had a higher proportion of sentences related to Residence. The Social Documentation notes, which could have been authored by any clinician type, had the highest number of sentences related to Living Situation and Living Conditions.

Further analysis and mapping of the Residence sentences to the element axes showed persistent use of status, residence type and geographic location. Temporal entities and attributes were less prevalent with most documentation describing current state with some references to past situations. For Living Situation there was again significant presence of status as we as subject specifically family member. Living conditions was much less represented in these data sources and most references were related to type of water available.

The enhanced model representations (Tables 6A, B, C), built upon the foundation of previous standards evaluation work, now represent the analysis of 27 data sources including existing standards, terminologies, guidelines, and measures and Surveys as well as the analysis of 2491 notes. The analysis of the notes added more elements. For Residence and Living Situation the temporality elements “Duration Since Time Point”, “Time Point”, and “Time Frame” were added as was the element “Residence Type Subtype’ and “Living Situation Detail Subtype”. For Living Conditions the temporal elements “Duration Since Time Point” and “Time Point” were added. Overall, the EHR unstructured text significantly contributed to enhance and strengthen the model representation. Value lists are much more complete for each of the elements.

Although we obtained an inter-rater reliability of K= 0.84 and proportion agreement of 0.98, we observed some inconsistency between reviewers regarding the difference between Geographic Location as opposed to Location Detail. This inconsistency was resolved and the annotation schema was amended accordingly. Another challenge area was around statements regarding safety concepts. In some cases safety items such as railings and stairs were annotated as Residence Detail and in other they were annotated as Living Conditions Detail. More work will be needed to sort out where these concepts logically fit the best. Lastly, while it is expected that not every sentence would have every element, in examination of these results it was noted that in the Residence annotations the number of sentences that had a “status” documented was lower than expected. After further manual review the issue was traced back to several of the question answer type “Living Arrangements” could be considered a section header and, in past work, section headers have been identified separately from text. For this work these sentences were left as is and will be considered in future work and iterations of the annotation schema.

In summary, this work has demonstrated that the SDOH topic areas of Residence, Living Situation, and Living Conditions are being documented in the EHR within unstructured text, specifically general progress notes, Social Documentation notes, and notes authored by Social Workers, Physical Therapists, and Occupational Therapists. This analysis contributes to overall representation models for these three topic areas. Next steps will include an evaluation of flow sheet documentation related to these three topic areas and further enhancement of the model representation that can be used to extract information from EHR text, to design discrete data collection tools for the EHR, and to contribute to the development of ontology for the social history topics of Residence, Living Situation, and Living Conditions.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health (R01LM011364) and University of Minnesota Clinical and Translational Science Award (8UL1TR000114-02). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Healthy People. Gov: U.S. Department of Health & Human services. 2012. [cited 2014 1/7/2014]. Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2Q2Q/about/DOHAbout.aspx-socialfactors.

- 2.Hernandez LM, Blazer DG, editors. Washington (DC): The National Institutes; 2006. Genes, Behavior, and the Social Environment: Moving Beyond the Nature/Nurture Debate. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Social Determinants of Health: World Health Organization. 2014. [cited 2014 1/7/2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/social determinants/sdh definition/en/index.html.

- 4.McGinnis JM. Health in America--the sum of its parts. JAMA. 2002;287(20):2711–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.20.2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babor TF, Sciamanna CN, Pronk NP. Assessing multiple risk behaviors in primary care. Screening issues and related concepts. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2 Suppl):42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jane-Llopis E, Matytsina I. Mental health and alcohol drugs and tobacco: a review of the comorbidity between mental disorders and the use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25(6):515–36. doi: 10.1080/09595230600944461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kipke MD, Weiss G, Wong CF. Residential status as a risk factor for drug use and HIV risk among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6 Suppl):56–69. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9204-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milloy MJ, Marshall BD, Montaner J, Wood E. Housing status and the health of people living with HIV/AIDS. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012;9(4):364–74. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0137-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suglia SF, Duarte CS, Sandel MT. Housing quality, housing instability, and maternal mental health. J Urban Health. 2011;88(6):1105–16. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9587-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinstein LC, Lanoue MD, Plumb JD, King H, Stein B, Tsemberis S. A primary care-public health partnership addressing homelessness, serious mental illness, and health disparities. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(3):279–87. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.03.120239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa-Font J. Housing assets and the socio-economic determinants of health and disability in old age. Health Place. 2008;14(3):478–91. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rollins C, Glass NE, Perrin NA, Billhardt KA, Clough A, Barnes J, et al. Housing instability is as strong a predictor of poor health outcomes as level of danger in an abusive relationship: findings from the SHARE Study. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(4):623–43. doi: 10.1177/0886260511423241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leff HS, Chow CM, Pepin R, Conley J, Allen IE, Seaman CA. Does one size fit all? What we can and can’t learn from a meta-analysis of housing models for persons with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):473–82. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw M. Housing and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:397–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henwood BF, Cabassa LJ, Craig CM, Padgett DK. Permanent supportive housing: addressing homelessness and health disparities? Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S188–92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomson H, Thomas S, Sellstrom E, Petticrew M. Housing improvements for health and associated socioeconomic outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD008657. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008657.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs DE, Brown MJ, Baeder A, Sucosky MS, Margolis S, Hershovitz J, et al. A systematic review of housing interventions and health: introduction, methods, and summary findings. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(5 Suppl):S5–10. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181e31d09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nath SB, Wong YL, Marcus SC, Solomon P. Predictors of health services utilization among persons with psychiatric disabilities engaged in supported independent housing. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2012;35(4):315–23. doi: 10.2975/35.4.2012.315.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adamkiewicz G, Zota AR, Fabian MP, Chahine T, Julien R, Spengler JD, et al. Moving environmental justice indoors: understanding structural influences on residential exposure patterns in low-income communities. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(Suppl 1):S238–45. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braubach M, Fairburn J. Social inequities in environmental risks associated with housing and residential location--a review of evidence. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(1):36–42. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson SL, Bonnie RJ. A systematic examination of smoke-free policies in multiunit dwellings in Virginia as reported by property managers: implications for prevention. Am J Health Promot. 2011;26(1):37–44. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.091005-QUAN-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Standish K, Nandi V, Ompad DC, Momper S, Galea S. Household density among undocumented Mexican immigrants in New York City. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(3):310–8. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Washington D.C: 2014. Capturing social and behavioral domains and measures in electronic health records: Phase 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2014. Capturing social and behavioral domains in electronic health records: Phase 1. Available from: http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2014/Capturing-Sodal-and-Behavioral-Domams-m-Electronic-Health-Records-Phase-l.aspx. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winden TJ, Chen ES, Melton GB. Representing Residence, Living Situation, and Living Conditions: An Evaluation of Terminologies, Standards, Guidelines, and Measures/Surveys. Proceedings American Medical Informatics Symposium; 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uzuner O, Goldstein I, Luo Y, Kohane I. Identifying patient smoking status from medical discharge records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(1):14–24. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Chen ES, Pakhomov S, Arsoniadis E, Carter EW, Lindemann E, et al. Automated Extration of Substance Use Information from Clinical Texts. AMIA Annual Symposium proceedings / AMIA Symposium AMIA Symposium; 2015. pp. 2121–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melton GB, Manaktala S, Sarkar IN, Chen ES. Social and behavioral history information in public health datasets; AMIA Annu Symp Proc; 2012. pp. 625–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.University of Pittsburgh NLP Repository Department of Biomedical Informatics, University of Pittsburgh [Internet] 2015. Available from: http://www.dbmi.pitt.edu/nlpfront.

- 31.General Architecture for Text Engineering (GATE) [cited 2014]. Available from: https://gate.ac.uk/

- 32.brat rapid annotation tool. [cited 2014]. Available from: http://brat.nlplab.org/