Abstract

Patient portal and personal health record adoption and usage rates have been suboptimal. A systematic review of the literature was performed to capture all published studies that specifically addressed barriers, facilitators, and solutions to optimal patient portal and personal health record enrollment and use. Consistent themes emerged from the review. Patient attitudes were critical as either barrier or facilitator. Institutional buy-in, information technology support, and aggressive tailored marketing were important facilitators. Interface redesign was a popular solution. Quantitative studies identified many barriers to optimal patient portal and personal health record enrollment and use, and qualitative and mixed methods research revealed thoughtful explanations for why they existed. Our study demonstrated the value of qualitative and mixed research methodologies in understanding the adoption of consumer health technologies. Results from the systematic review should be used to guide the design and implementation of future patient portals and personal health records, and ultimately, close the digital divide.

Introduction

The successful treatment of many chronic diseases, like diabetes mellitus, has long been facilitated by strong patient investiture in his or her own healthcare. Empowered and well-informed patients who have access to their personal health data—such as their HbA1c trend over time—may be persuaded to make sound behavioral modifications that correlate with their disease progression.1 Patient portals and personal health records (PHRs) typically provide patients with access to their own laboratory and imaging results, alternative modes of communication with their providers, and many other benefits.2–3

Despite the availability of patient portals and PHRs for nearly a decade, the adoption rate and use of both consumer health technologies among patients have been low. Researchers are becoming increasingly attentive to the barriers that prevent certain members of the population from using patient portals and PHRs. Factors related to socioeconomic status, race, age, or health condition should not influence the penetrance of patient portals and PHRs into society to the extent that they currently do. These technologies need to be embraced across the population to be optimally effective, otherwise disparities in the quality of and access to care will increase.4

Given the growing body of literature on the topics of patient portal and PHR adoption and use, in addition to regulatory pressures on healthcare organizations to increase patient enrollment, the need has arisen for a critical analysis of the current literature to best understand how to pursue subsequent research and policy endeavors in a meaningful way. In this study, we aim to systematically review the literature to identify publications that specifically address barriers, facilitators, and solutions to successful enrollment and use of patient portals and PHRs.

Methods

Overview & Scope

Patient portals are secure online tools that can stand alone or be tethered to a healthcare organization’s health record, through which patients can access their personal health information from anywhere with an internet connection.2 PHRs are online applications that are owned and managed by patients or their proxies and allow for patient input of information for greater control of patients’ own health information management.3 While the two consumer health technologies serve different functions for patients in terms of ownership, the factors that hinder or facilitate their enrollment and use are fairly equivalent. Moreover, patient portals and PHRs at times are used interchangeably in the literature. Therefore, we conducted our systematic review to address barriers and facilitators of adoption and use of both patient portals and PHRs, rather than try to determine whether authors meant one versus the other based on terminology and context. In this study, any reference to patient portals is meant to be synonymous with a reference to PHRs, unless explicitly indicated.

Our review included studies that identified barriers, facilitators, and/or solutions. The reason for delving into all three rather than focus on one was to gain an in-depth understanding of what exactly has been studied in the literature and what else remains to be studied. For the scope of this review, the following traditional definitions were used:

Barrier: a law, rule, problem, etc., that makes something difficult or impossible.5

Facilitator: one that helps to bring about an outcome by providing indirect or unobtrusive assistance, guidance, or supervision.6

Solution: an answer to a problem.7

For the purposes of this study, the term “solution” included proposed or implemented methods to address enrollment or usability barriers, even if further study was still required. As such, “solutions” should be distinguished from “facilitators,” which have been studied and proven via evidence to help bring about improvements in patient portal enrollment and use.

Selections for analysis were made from quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods studies published in scientific journals, peer-reviewed conference proceedings, and reputable sources identified by domain experts. Purely descriptive studies of patient portals or of individual characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race) were excluded from analysis.

Literature Search

The search strategy, including the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and keywords, was developed and performed under the guidance of a health science librarian (DS). The search was performed using MEDLINE® via Ovid as the database. This particular database was chosen for the level of granularity authors could employ in the search strategy compared to other databases. The search query used was [“Patient access to records” (MeSH) OR “patient participation” (MeSH) OR “health records, personal” (MeSH) OR “patient portal” (keyword) OR “web portal” (keyword) OR “patient health record” (keyword)] AND [“health services accessibility” (MeSH) OR “health knowledge, attitudes, practice” (MeSH) OR “‘patient acceptance of health care’” (MeSH) OR “user-computer interface” (MeSH) OR “implementation barrier” (keyword) OR “usability” (keyword) OR “human factors” (keyword) OR “barriers to access” (keyword) OR “facilitators to access” (keyword) OR “provider access” (keyword) OR “caregiver access” (keyword)]. All searches were limited to human studies and published in English between the years 2000 and 2017 with full text availability. Reference mining was performed on key articles and from content experts. Prior systematic reviews were used to identify original studies.

Screening & Data Extraction

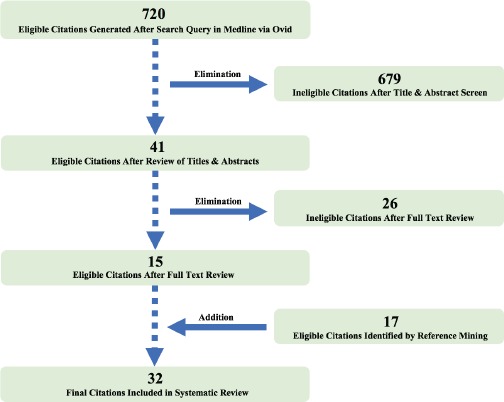

Three authors (JZ, EA, & BS) screened seven hundred twenty titles and abstracts for eligibility. Selected full-text articles were read in their entirety to determine final inclusion or exclusion (Figure 1). Initial screening and data extraction were performed together to facilitate inter-rater reliability. Subsequent screening and data extraction occurred independently. The workload was distributed evenly among authors at each screening iteration. Any discrepancies that occurred were discussed and resolved through consensus-building.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of article selection and elimination.

Analysis

At least two authors reviewed each article. Authors independently took notes on barriers, facilitators, and solutions mentioned in the selected full-text articles and recorded their findings in a shared data shell. Recurrent themes were identified and used to code the extracted data (Table 1).

Table 1.

Two examples of how similarities between extracted data about barriers, facilitators, and solutions (notes made by JZ, EA, BS) were codified by theme (rightmost column).

|

Results

Seven hundred-twenty citations from MEDLINE® via Ovid were identified by the literature search. Forty-one were identified as potentially eligible after screening through titles and abstracts. Fifteen articles met eligibility after full- text review. Seventeen additional articles that met eligibility criteria but were not found via the initial literature search were identified by reference mining. Thirty-two articles were ultimately included in the review (Table 2). Of the included articles, eight were quantitative, nineteen were qualitative, and five were mixed methods studies. Several of the captured themes were represented across studies (Figure 2).

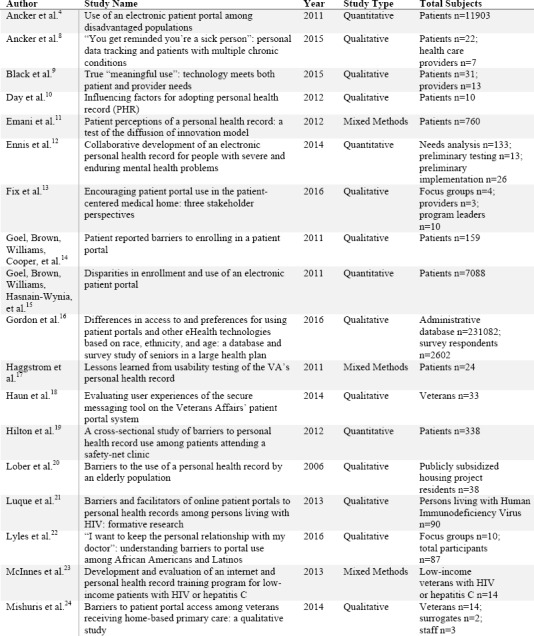

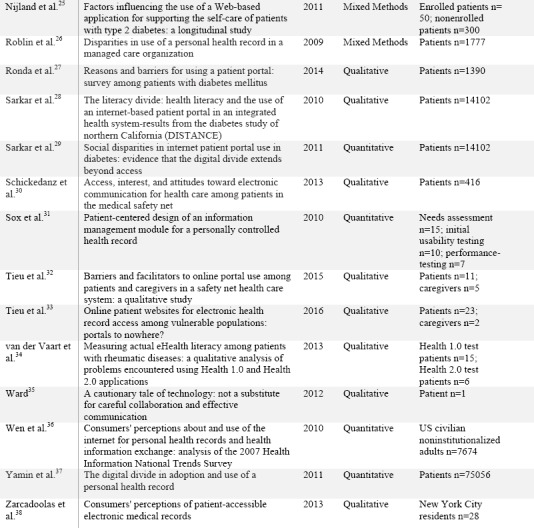

Table 2.

List of eligible studies included in systematic review.

|

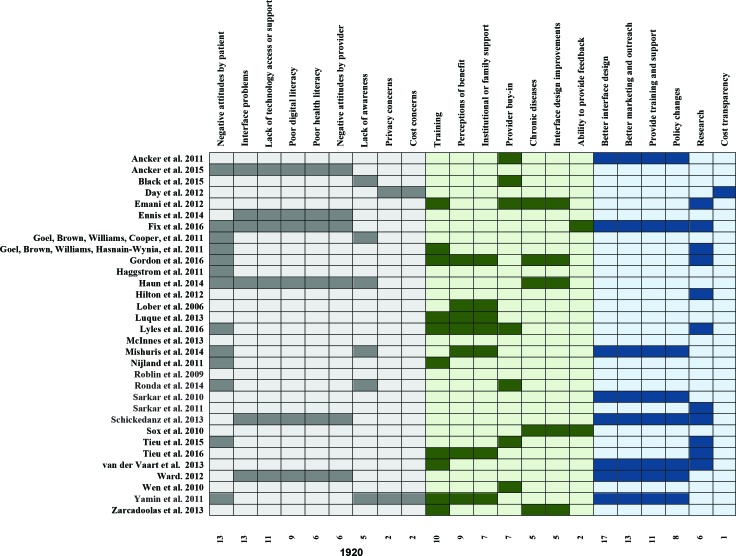

Figure 2.

Themes captured from reviewed articles. Light grey columns represent barriers. Light green columns represent facilitators. Light blue columns represent solutions. A shaded cell indicates that the barrier/facilitator/solution was present in a study. Theme counts are totaled at the bottom of each column.

Barriers

Thirteen studies identified attitude or culture as a barrier to effective enrollment and use of patient portals. 8,13–18,22,24–25,27,32,37 Patients either felt overtly negative toward the patient portal (e.g., self-tracking was explicitly perceived as extra work, distrust of the healthcare system as a whole was a cultural norm among certain populations and patient portals were viewed as unwelcome extensions of healthcare) or were satisfied with the status quo (e.g., concern that embracing patient portals would erode the personal patient-physician relationship).

Six articles acknowledged mixed or negative attitudes among providers as barriers. Providers felt conflicted over whose responsibility it was to promote the patient portal and saw the patient portal as extra work added to an already long list of burdensome clinical responsibilities.8,12,13,18,30,35

Thirteen studies mentioned interface challenges.9–13,16–17,25,31–32,34–35,38 Problems ranged from unintuitive design elements that created navigation difficulties to the use of text or language at a reading comprehension level too high for most users. In fact, most non-users had not completed high school, which exacerbated their ability to fully comprehend the complexities of their various comorbidities.11,16,19–20,23,26,28–29,31–34 Nine studies specifically made a point to underscore that no amount of patient portal training could help patients who were functionally illiterate at baseline. Many non-users also had poor digital literacy or lacked computer or internet access. Among these were patients who felt uncomfortable using public resources to access private health information online, e.g., at a public library.

In six of the studies, patients either had not been fully educated about the extent of functionalities offered by the patient portal and felt that the features they knew about were not worth the hassle of continued use, or had not even been informed about the patient portal’s existence prior to the study. Technical or logistical difficulties with the enrollment process (e.g., difficult navigation, lack of information technology support) prevented interested patients from completing registration in fifteen studies.8,10,12–15,17,20–24,26,31,36

Privacy concerns were captured as barriers in five studies.15,17–18,21,30 People did not have adequate assurance that their personal data were secure on the internet. Others desired extra security after logging into the patient portal or PHR to hide the display of sensitive information. This finding was notable among senior patients who often required the assistance of family or friends to help them navigate the patient portal or PHR or to use it on their behalf via proxy access.

Cost concerns were addressed in two of the studies.10,37 Certain users chose to not explore different patient portal features out of concern they might be charged. These same users expressed willingness to pay for extra features in the portal (e.g., after-hours secure messaging with their physician) so long as prices were made transparent.

Facilitators

Ten studies identified successful registration as a facilitator to continued patient portal use. Institutions with support staff—i.e., informational technology personnel, nurses, and even doctors—who dedicated time to walk patients through the patient portal and show them the various capabilities on one or more trial runs were successful at committing patients to enroll. Patients who had family members help them enroll were also successful. Twelve studies described the benefits of training. Many patients were interested but felt uncomfortable navigating the patient portal. Training engendered familiarity with the interface and enabled ongoing use of the patient portal.11,15–16,20–22,24–25,33–34,37–38

Patients and providers were likely to use the patient portal if they perceived the patient portal to be more beneficial than existing options (e.g., secure messaging versus calling). This was largely dependent on prior use of the patient portal as well as provider buy-in.’4,9–11,13,15–16,18,22,24–25,27,32,36,38 To convince patients to enroll, providers had to promote the patient portal in the legitimate context of a clinical visit and provide assurance that the patient portal would supplement, not replace, the existing patient-physician relationship. Providers were particularly effective advocates of the patient portal or personal health record among senior and minority patients. Five studies described how patients with chronic illnesses often relied on the patient portal to request prescription refills or to prepare for their next clinic visit.4,15,25–26,37

Six studies identified iterative feedback loops as critical facilitators. Patient portals that went through multiple rounds of usability testing and relied on user feedback prior to modifications often found greater success in patient adoption and use.11,13,16,18,31,38 Being able to make timely evidence-based improvements was also key to steadily increasing user enrollment and maintaining continued use by patients.

Solutions

Eight studies promoted policy changes at the public and institutional level to stimulate increased computer and internet access, and to emphasize the impact of the digital divide as a public health concern.4,13,24,28,30,34–35,37 Eleven studies proposed training and support for patients on digital basics and on the patient portal. In two studies, authors advocated for the continuation of traditional health information resources in print form.14,24

Authors from thirteen studies advocated for more aggressive tailored marketing strategies toward disadvantaged populations. The key was to indiscriminately highlight all advantages of the patient portal, and not solely emphasize its potential as a self-management tool. Self-management was often viewed more as burden than benefit among disadvantaged, chronically ill patients.4,13–16,18–19,24,26–29,32 Transparency about patient portal capabilities, security features, and costs of services was also encouraged.

Redesigns in patient portal interfaces were mentioned in seventeen studies.4,8–10,12,15–18,24–25,28,30,32,34–35,38 Authors advocated for standardization in the creation of future patient portals. Easy-to-use, easy-to-navigate interfaces and simpler language were all encouraged to attract patients across socioeconomic groups. Six studies indicated the need for more consumer health informatics research.10,12,26,29,33–34

Discussion

Patient portals and PHRs were conceived as revolutionary and transformative patient engagement tools, but the reality has been disappointing given low enrollment and usage equitably across populations. Efforts have been made in recent years by researchers to understand the factors that contribute to the success or failure of consumer health technology adoption. Our systematic review evaluated all publications since 2000 that specifically addressed barriers, facilitators, and solutions to optimal patient portal and PHR enrollment and use. Popular themes were identified.

Negative attitudes by patients posed one of the most common barriers. Negative attitudes ranged from outright refusal to engage with the technology, to apathy or ambivalence. Without the provision of a clinically relevant context to the data displayed, patient-accessible laboratory work or imaging results came across to patients as meaningless, confusing, and in the worst-case scenario, even detrimental. On the other hand, patients’ perception of the patient portals’ value increased after the patient portals’ capabilities were showcased and demonstrated, particularly when done so by their providers. For instance, patients who were older or had multiple comorbid conditions represented users who saw great value in having an online resource to keep track of their many medications and provider recommendations. Moving forward, healthcare organizations will need to make greater efforts to recruit providers in the promotion of consumer health technologies without these efforts being seen as yet another clinical documentation burden.

Toward that end, marketing and outreach need to occur indiscriminately, while being sensitive to the likelihood that users from different socioeconomic statuses and cultures may have different expectations of the patient portal. These solutions reflect the bare minimum requests by researchers to prevent the digital divide from widening. The onus falls on informatics societies, such as the American Medical Informatics Association, to not only raise the bar for consumer health technologies by establishing and promoting gold standard guidelines for the design and implementation of patient portals and PHRs, but to also hold vendors and healthcare organizations accountable.

Having a governing body oversee standardization of patient portals and PHRs is more important than ever, especially since our systematic review has revealed that the other most common barrier to patient portal and PHR registration and use is the lack of a user-friendly interface. While providing staffing and resources to help patients interact with the patient portal interface has proven beneficial, particularly in alleviating stress or anxiety associated with patient portal enrollment and navigation for “digital immigrants (individuals who do not or cannot access computers and the internet on a regular basis, e.g. the poor and the elderly16),” the reality remains unchanged that many interfaces are long overdue for a facelift.

Future Directions

Consumer health informatics is a growing discipline. Our review of the literature has provided patient portal and PHR vendors and the institutions that purchase them a succinct summary of all available evidence-based strategies to recruit and retain patient portal and PHR users. Ongoing research, particularly in the domain of human factors and usability testing, would be beneficial for the continued optimization of consumer health technology adoption.39–40

Conclusion

We conducted a systematic review and identified several themes in barriers and facilitators of patient portal and PHR adoption and use. Common barriers were negative attitudes by patients and interface problems. Frequently reported facilitators were perceptions of benefit and the provision of patient portal and PHR training. Interface redesign and improved marketing and outreach were popular solutions. More research is needed in human factors and usability testing to understand how to engage and motivate patients toward improved health outcomes. Sufficient penetration of patient portals and PHRs into patients’ routine healthcare practices will provide researchers and providers the opportunity to harness the intellect, energies, and care of patients to achieve mutual healthcare goals.

References

- 1.Funnell MM, Anderson RM, Arnold MS, Barr PA, Donnelly M, Johnson PD, Taylor-Moon D, White NH. Empowerment: an idea whose time has come in diabetes education. Diabetes Educ. 1991;17(1):37–41. doi: 10.1177/014572179101700108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.HealthlT. What is a patient portal? (Internet) [Cited 2017 February 20]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/faqs/what-patient-portal.

- 3.HealthlT. What is a personal health record? (Internet) [Cited 2017 February 20]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/faqs/what-personal-health-record.

- 4.Ancker JS, Barrón Y, Rockoff ML, Hauser D, Pichardo M, Szerencsy A, Calman N. Use of an electronic patient portal among disadvantaged populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(10):1117–23. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1749-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrier (Internet) Merrium-Webster An Encyclopedia Britannica Company; [Cited 2017 January 30]. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/barrier. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Facilitator (Internet) Merrium-Webster An Encyclopedia Britannica Company; [Cited 2017 January 30]. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/facilitator. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solution (Internet) Merrium-Webster An Encyclopedia Britannica Company; [Cited 2017 January 30]. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/solution. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ancker JS, Witteman HO, Hafeez B, Provencher T, Van de Graaf M, Wei E. “You get reminded you’re a sick person”: personal data tracking and patients with multiple chronic conditions. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(8):e202. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black H, Gonzalez R, Priolo C, Schapira MM, Sonnad SS, Hanson CW, 3r, Langlotz CP, Howell JT, Apter AJ. True “meaningful use”: technology meets both patient and provider needs. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(5):e329–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Day K, Gu Y. Influencing factors for adopting personal health record (PHR) Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;178:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emani S, Yamin CK, Peters E, Karson AS, Lipsitz SR, Wald JS, Williams DH, Bates DW. Patient perceptions of a personal health record: a test of the diffusion of innovation model. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(6):e150. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ennis L, Robotham D, Denis M, Pandit N, Newton D, Rose D, Wykes T. Collaborative development of an electronic personal health record for people with severe and enduring mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:305. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0305-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fix GM, Hogan TP, Amante DJ, McInnes DK, Nazi KM, Simon SR. Encouraging patient portal use in the patient-centered medical home: three stakeholder perspectives. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(11):e308. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goel MS, Brown TL, Williams A, Cooper AJ, Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW. Patient reported barriers to enrolling in a patient portal. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(Suppl 1):i8–12. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goel MS, Brown TL, Williams A, Hasnain-Wynia R, Thompson JA, Baker DW. Disparities in enrollment and use of an electronic patient portal. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(10):1112–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1728-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon NP, Hornbrook MC. Differences in access to and preferences for using patient portals and other eHealth technologies based on race, ethnicity, and age: a database and survey study of seniors in a large health plan. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(3):e50. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haggstrom DA, Saleem JJ, Russ AL, Jones J, Russell SA, Chumbler NR. Lessons learned from usability testing of the VA’s personal health record. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(Suppl 1):i13–7. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2010-000082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haun JN, Lind JD, Shimada SL, Martin TL, Gosline RM, Antinori N, Stewart M, Simon SR. Evaluating user experiences of the secure messaging tool on the Veterans Affairs’ patient portal system. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e75. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilton JF, Barkoff L, Chang O, Halperin L, Ratanawongsa N, Sarkar U, Leykin Y, Muñoz RF, Thom DH, Kahn JS. A cross-sectional study of barriers to personal health record use among patients attending a safety-net clinic. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lober WB, Zierler B, Herbaugh A, Shinstrom SE, Stolyar A, Kim EH, Kim Y. Barriers to the use of a personal health record by an elderly population. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006:514–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luque AE, van Keken A, Winters P, Keefer MC, Sanders M, Fiscella K. Barriers and facilitators of online patient portals to personal health records among persons living with HIV: formative research. JMIR Res Protoc. 2013;2(1):e8. doi: 10.2196/resprot.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyles CR, Allen JY, Poole D, Tieu L, Kanter MH, Garrido T. “I want to keep the personal relationship with my doctor”: understanding barriers to portal use among African Americans and Latinos. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(10):e263. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McInnes DK, Solomon JK, Shimada SL, Petrakis BA, Bokhour BG, Asch SM, Nazi KM, Houston TK, Gifford AL. Development and evaluation of an internet and personal health record training program for low-income patients with HIV or hepatitis C. Med Care. 2013;51(3) Suppl 1:S62–6. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827808bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishuris RG, Stewart M, Fix GM, Marcello T, McInnes DK, Hogan TP, Boardman JB, Simon SR. Barriers to patient portal access among veterans receiving home-based primary care: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):2296–305. doi: 10.1111/hex.12199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nijland N, van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Kelders SM, Brandenburg BJ, Seydel ER. Factors influencing the use of a Web-based application for supporting the self-care of patients with type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e71. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roblin DW, Houston TK II, Allison JJ, Joski PJ, Becker ER. Disparities in use of a personal health record in a managed care organization. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(5):683–9. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ronda MC, Dijkhorst-Oei LT, Rutten GE. Reasons and barriers for using a patient portal: survey among patients with diabetes mellitus. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(11):e263. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarkar U, Karter AJ, Liu JY, Adler NE, Nguyen R, Lopez A, Schillinger D. The literacy divide: health literacy and the use of an internet-based patient portal in an integrated health system-results from the diabetes study of northern California (DISTANCE) J Health Commun. 2010;15(Suppl 2):183–96. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarkar U, Karter AJ, Liu JY, Adler NE, Nguyen R, López A, Schillinger D. Social disparities in internet patient portal use in diabetes: evidence that the digital divide extends beyond access. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(3):318–21. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2010.006015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schickedanz A, Huang D, Lopez A, Cheung E, Lyles CR, Bodenheimer T, Sarkar U. Access, interest, and attitudes toward electronic communication for health care among patients in the medical safety net. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(7):914–20. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2329-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sox CM, Gribbons WM, Loring Ba, Mandi KD, Batista R, Porter SC. Patient-centered design of an information management module for a personally controlled health record. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(3):e36. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tieu L, Sarkar U, Schillinger D, Ralston JD, Ratanawongsa N, Pasick R, Lyles CR. Barriers and facilitators to online portal use among patients and caregivers in a safety net health care system: a qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(12):e275. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tieu L, Schillinger D, Sarkar U, Hoskote M, Hahn KJ, Ratanawongsa N, Ralston JD, Lyles CR. Online patient websites for electronic health record access among vulnerable populations: portals to nowhere? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;pii:ocw098. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Vaart R, Drossaert CH, de Heus M, Taal E, van de Laar MA. Measuring actual eHealth literacy among patients with rheumatic diseases: a qualitative analysis of problems encountered using Health 1.0 and Health 2.0 applications. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(2):e27. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ward ME. A cautionary tale of technology: not a substitute for careful collaboration and effective communication. JONAS Healthc Law Ethics Regul. 2012;14(3):77–80. doi: 10.1097/NHL.0b013e318263eb0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wen KY, Kreps G, Zhu F, Miller S. Consumers’ perceptions about and use of the internet for personal health records and health information exchange: analysis of the 2007 Health Information National Trends Survey. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(4):e73. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamin CK, Emani S, Williams DH, Lipsitz SR, Karson AS, Wald JS, Bates DW. The digital divide in adoption and use of a personal health record. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(6):568–74. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zarcadoolas C, Vaughon WL, Czaja SJ, Levy J, Rockoff ML. Consumers’ perceptions of patient-accessible electronic medical records. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e168. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beuscart-Zéphir MC, Aarts J, Elkin P. Human factors engineering for healthcare IT clinical applications. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79(4):223–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elkin PL. Human Factors Engineering in HI: So what? Who cares? and what’s in it for you? Healthc Inform Res. 2012;18(4):237–41. doi: 10.4258/hir.2012.18.4.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]