Abstract

Patient safety and quality of care are at risk if the informed consent process does not emphasize patient comprehension. In this paper, we describe how we designed, developed, and evaluated an mHealth tool for advancing the informed consent process. Our tool enables the informed consent process to be performed on tablets (e.g., iPads) utilizing virtual coaching with text-to-speech automated translation as well as an interactive multimedia elements (e.g., graphics, video clips, animations, presentations, etc.). We designed our tool to enhance patient comprehension and quality of care, while improving the efficiency of obtaining patient consent. We present the Used-Centered Design approach we adopted to develop the tool and the results of the different methods we used during the development of the tool. Also, we describe the results of the usability study which we conducted to evaluate the effectiveness, efficiency, and user satisfaction with our mHealth App to enhance the informed consent process. Using the UCD approach we were able to design, develop, and evaluate a highly interactive mHealth App to deliver the informed consent process.

Keywords: informed consent, mHealth, user-centered design

Introduction

Objective: Informed consent (IC) is essential for the ethical conduct of research and medical treatment. The overarching goal of the IC process is to guarantee that the patient acquires a sound understanding of the purpose, risks, and methodology of a clinical trial and/or medical procedure1,1 For patients to fully understand the content of the IC process, the informed consent document should clearly explain the purpose, process, risks, benefits and alternatives to medical procedures or clinical research, while stressing the patient’s rights and responsibilities3. If the IC process achieves patient comprehension, then healthcare costs and patient safety risk can likely be deterred4. In regards to the expert consensus on IC tools, the Joint Commission (2007) reported that, “among patients who sign an IC form, 44% do not understand the nature of the procedure to be performed, and 60-70% did not read or understand the information contained in the form.” Thus, the Joint Commission urges reform given the poor potential of the IC process in achieving patient understanding.

Background: Studies have shown that the lack of sufficient comprehension of information included in the IC document negatively impacts patient safety and quality of care1,2,5. Patients want to be involved in making decisions about their own care. Currently, the standard consent process (paper and/or electronic) does not always guarantee patient comprehension or improve the quality of care. The real challenge is that many patients lack the means to truly comprehend existing IC documents5. As a result, many patients are consenting without fully comprehending the content and purpose of the consent form.

To minimize costs and risks, many providers have used electronic IC, but these systems are usually digital versions of standard paper-based systems6. Traditional consent forms, both paper and electronic, contain limited and/or inadequate descriptions – this inaccessibility is exacerbated with a high-level scientific vocabulary and a lack of a patient-centered approach. Therefore, the paper/electronic IC forms often require the medical provider or researcher to provide a simplified verbal laymen translation. This may also pose strain for patients, given the provider may not be the most adept at explaining the IC form contents. Many patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR) studies have advocated for providing more efficient, informative, and useful patient-centered informed consent processes2,7.

Related works: Research findings suggest Health Information Technology (HIT) interventions are successful tools for improving patient safety and quality of care8–10. Virtual coaching, using mobile apps, shows great promise in encouraging general motivation to achieve healthy outcomes. Such interventions enabled through mobile health (mHealth) are completed by patients using apps on tablets (e.g., iPad), while maintaining the patient’s anonymity. mHealth architecture can be adopted as an IC medium in emphasizing patient-centered IC processes11. mHealth achieves the planned aspect in that it allows patients to collect and report their own exposure history in real time on an app, rather than having to recall it after time has passed. Furthermore, in advocating for open and shared mHealth architectures, patients will not have to needlessly switch between apps to check exposure history or medical records. With an open architecture, the coherence and integration of mHealth benefits are emphasized. In addition to consolidating data interface in the mHealth tool, multimedia may also assist patients’ understanding and satisfaction with a research clinical trial or medical treatment process. Multimedia can also be used to tailor the mHealth tool to be more patient-centered, which is the primary goal of undertaken by this study13–17.

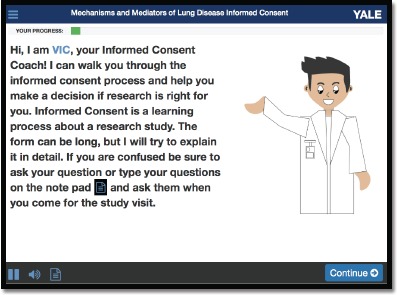

Study Development: Given that the standard consent process does not always guarantee patient comprehension or improve the quality of care, many patients are consenting without the necessary knowledge of IC form contents12. To improve the traditional IC process, we developed the Patient Centered Virtual Multimedia Interactive Informed Consent tool (VIC) (See Figure 1). Our approach uses virtual coaching to conduct a brief and virtual interview with patients using tablet computers (e.g., iPads) with a comprehensive multimedia library (e.g., video clips, animations, presentations, etc.) to explain the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the proposed treatment or clinical study, to enhance patient awareness11,13,14 Our tool presents the IC materials to patients with the option of additional review to increase information grasp. The VIC tool has an option to assess patient comprehension with automated quizzes, which can help patients assess their own comprehension of the information presented. VIC provides many features and functions including Internet access to the consent, a retrievable electronic record of IC, electronic signature, and potential for seamless integration with the electronic health record (EHR). Moreover, VIC includes extensive security strategies that will guarantee the confidentiality and privacy of the patient and the clinical information. It also provides access to the IC content via the Internet before, during and after the study or procedure, allowing patients to benefit from supplemental resources as well11,13–17.

Figure 1.

The Patient Centered Virtual Multimedia Interactive Informed Consent tool (VIC).

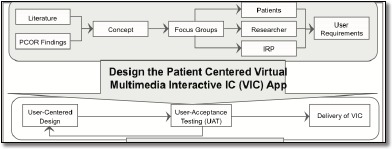

In this paper, we present how we developed the VIC mHealth App based on prior work and evidence in IC research to support the patient-centered IC as well as enhance patient comprehension. We describe in detail the state-of-the-art software standards and the User-Centered Design approach (UCD) that we used to design, develop, refine, and test the VIC mHealth App. Moreover, we present the usability evaluation approach that we took to ensure that VIC satisfies the highest standard for usability and acceptability along while maintaining effectiveness, efficiency and patient satisfaction. The following sections list key factors that influenced design and development of VIC (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The mHealth App Development Approach

Methods

We used several methods to design, build, and evaluate VIC. The Our methods were based on the User-Centered Design (UCD) approach including requirement gathering and analysis, conceptual design, focus groups, design and development of mockups screen and prototype, usability evaluation of the prototype, development of the VIC system, and usability evaluation of VIC App. In this section, we describe these methods with an emphasis on the patient oriented design. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Yale University reviewed and approved the study protocol.

User-Centered Design Methodology (UCD).

We adapted UCD to build VIC, that is, an iterative multi-stage design approach that involves the user’s input throughout the development process18,19. UCD gives extensive attention to the user’s needs, wants and limitations at each stage of the design process and allows User Experience (UX) evaluations to be incorporated into the design. We used the data collected throughout various design phases to enhance the overall design iteratively. Specifically, we incorporated UCD techniques and UX evaluations to produce usable and acceptable software that delivers a more satisfying user experience. The result was a VIC system that is built and optimized around how patients can, want, or need to use it20. The following subsections list key factors that influenced design and development of the VIC system.

Conceptual Design.

The VIC system initial concept was developed based on prior work, and literature findings in IC research, patient input, and subject matter expert interviews. Our theoretical framework is based on Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning and the principle that the use of multimedia in the presentation of the IC process will improve patient comprehension15,16,21,22. In a recent study on patient-centered IC, Braithwaite et al. concluded that the type of IC that would be most suitable for patient-centered care is the type that is clinically oriented (e.g. decision aids) rather than legally oriented23.

Our goal was to develop a conceptual model with the patient in mind for a more efficient, informative, and effective patient-centered IC processes. We wanted to develop a model where a virtual coach could substitute for a human for most parts of the IC. The virtual coach would explain the IC in a way similar to how the study coordinator or a provider would explain the IC process to a study participant or patient. Therefore, the IC content could be presented in a style that is patient-friendly and easy to understand. The IC content should be brief and designed to quantify participant understanding, offering the participant a customized level of information. In addition, the model should include features to assess patient comprehension. Moreover, it should enhance the workflow and provide better access to the IC materials. Finally, it should also maintain the confidentiality and privacy of the patient and the clinical information.

Front-End Focus Group.

The goal of this focus group is to aid the initial design of VIC. We conducted a front-end focus group with patients and researchers from the Yale Center for Asthma and Airway Disease Mechanisms (YCAAD) clinic, and one IRB members from the Yale IRB office, as a part of the user requirements analysis. Patients were recruited by a research coordinator at the YCAAD clinic and were screened by the PI over the phone. Letters were then mailed containing directions and a reminder of the date and time of the focus group session. The focus group was held in a closed conference room at Yale University in July 2015 and lasted 80 minutes. All participants were told that their participation was voluntary and their information was confidential/anonymous. An introductory script was read to explain the purpose and guidelines of the focus group and followed a dialogue of open-ended questions along with follow-up questions (Table 1). A member of the research team moderated the focus group and two observers took notes of the sessions, which was also audio-recorded. Patients in the focus groups were compensated with an incentive payment of $45 for their participation. The two research participants were recruited by several members of the research team and were not compensated. The audio recording was later transcribed for purposes of analyzing themes and comments.

Table 1.

Semi-structured Focus Group Questions.

| Engagement Questions | When was the last time you had to go through the informed consent process? |

| Did something happen in the procedure that you did not expect or was not clearly discussed in the informed consent? | |

| Exploration Questions | Are you satisfied with how the informed consent process has functioned thus far? Why? |

| Why do you think the informed consent is in paper form? | |

| What do you think is missing from the current paper-based informed consent process? | |

| Do you believe a better-informed consent solution exists for protecting patients? | |

| In your opinion would video, audio, and graphical presentation help explain the informed consent process? Why? | |

| In your opinion, would using an iPad to complete the informed consent process help? [Prompt for discussion for comfort level for using the iPad to consent] | |

| What do you believe are other potential effects of iPad-based informed consent? [Prompt for discussion of both positive and negative effects, including the impact on patient decision] | |

| How do you see the role of the PI/Coordinator in conjunction with iPad-based informed consent? | |

| What are the issues/challenges you are interested in having the iPad-based informed consent address? | |

| How do you think the iPad-based informed consent would influence the safety and security of patients? | |

| How can we make iPad-based informed consent innovative but at the same time comply with IRB requirements? | |

| How much time should be spent on the informed consent process? | |

| Do you think we should keep both processes (paper and iPad-based informed consent)? | |

| Exit Question | Is there anything else you would like to say about the benefits or drawbacks of iPad-basedinformed consent? |

The focus group contained 5 participants: 2 patients, 2 researchers, and 1 IRB member. Because patient input is vital to understanding the IC and how it is perceived from a patient prospective, we have identified two patients from the community to work directly on the project as co-investigators. We engaged the co-investigators in all aspects of the project including design, development, implementation and evaluation. The information gathered from the Front-End Focus Group was used to formulate the Initial User Requirements. Then, the research team then held several design sessions to carefully define and list all accepted technical and functional requirements of VIC.

In general, all participants were open to the use of the iPad to present the informed consent. When asked about the level of comfort with the paper IC, participants expressed lack of comfort with the paper IC process. They felt that the IC was hard to read and understand, and full of many large words. They said that even though they read it, they did not really understand the content most of the time. Some said it is always the same thing and it is being repeated over and over. Participants stressed the importance of having the IC read out aloud to them. Some even said, “If no one reads it for me, I will just sign it and roll the dice”. Most participants felt the process was too long and should be made simpler. When asked about what is missing from the paper IC process, they said: “it should include a summary, some videos to let me know what to expect.” There were also comments regarding the need for patients to be informed. In summary, although participants were concerned about the safety and security of their private health information, they were very excited about the HIT approach to deliver the IC process.

We conducted a summative analysis of participant phrasing and word use. We used information gathered from this focus group to create user cases and personas.

User Requirements Collection and Analysis.

Because patient input is vital to understanding the IC and how it is perceived from a patient prospective, we have identified two patients from the community to work directly on the project as co-investigators. We engaged the coinvestigators in all aspects of the project including design, development, implementation and evaluation. The information gathered from the Front-End Focus Group was used to formulate the Initial User Requirements. Then, the research team then held several design sessions to carefully define and list all accepted technical and functional requirements of VIC.

Conceptual Model of the VIC mHealth App.

Based on the outcome of the Front-End Focus Group and the development of the conceptual model, our focus was mainly on developing VIC as a web-based App that would run on iPads to present IC content in a style that is patientfriendly and easy to understand. The initial model revolved around using a virtual coach or provider (see Figure 2), which guides the patient through the IC process. In VIC, the information and messages are displayed on the iPad screen and spoken through headphones for patient privacy. One of the innovative features of VIC is the ability to deliver health information through the use of multimedia and virtually guided interviews by a virtual provider (i.e. VIC), which explains the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the clinical procedure. Patients can view demos and presentations, and listen to comments and explanations. Animations and presentations will illustrate complicated content. The desired readability level for the text in VIC will be the 8th-grade level24. This will enable us to safeguard patients with limited literacy. VIC is modeled around the idea that the content IC session should be brief and designed to quantify participant understanding, offering the participant a customized level of information. Additionally, the model included automated quizzes to assess patient comprehension. It also required providing Internet access to the consent, a retrievable electronic record of IC, electronic signature, and integration with the electronic health record (EHR). Moreover, it required adopting comprehensive security strategies that would guarantee the confidentiality and privacy of the patient and the clinical information.

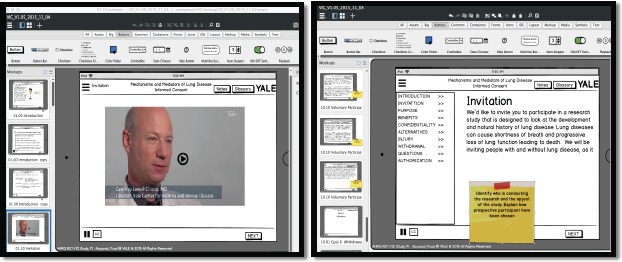

App Wireframe and Screens Prototypes.

We used Balsamiq Mockups to design the wireframe and screen mockups. Balsamiq Mockups is a drag-and drop mockup and a rapid wire framing tool that helped us work more efficiently. It reproduces the experience of sketching on a whiteboard, using a computer for the prototyping purposes25. The quick prototyping helped us simulate and test different versions of the tool’s User Interface. We continued to modify the mockups until we reached consensus on the final design. We used the content of the conceptual model and the system requirement to design the VIC mockups using the Balsamiq Mockups for the UI of the tablet (See Figure 4). Multiple sets and versions of VIC screens mockups were developed and tested and the modified and refined. During this process, we modified many features and properties of the end user interface. This included for example the process for testing user ability to use audio and the placement of navigation control and video control. The mockups provided us with means to test the flow of the screens and information and the amount of text that can be placed on single iPad screen. It also helped us decide on the most appropriate font size and color. We were able to evenly order and space the important sections and the main procedures. The Mockups expedited the development process and gave each research team member to visualize the software application and to be able to contribute to the design process in the joint design sessions. Using Balsamiq allowed us to produce a PDF prototype with full navigation capability comparable to the one of the final App.

Figure 4.

The VIC App Mockups Design

System Architecture.

In this subsection, we include detailed descriptions of the VIC system architecture, methods, technologies, tools, and the support services that were used in the implementation of the mobile App. We designed VIC to be a Web-based mobile application that runs using traditional Internet browser interface, or on Apple iPads and other mobile devices. We developed it using Microsoft C# .NET and it runs on Microsoft Windows Server, Microsoft Internet Information Server (IIS), and Microsoft SQL Server 2012. Figure 3 demonstrates VIC’s three-tiered architecture. In addition to tier separation and firewall protection, the separate tiers provide a model for creating secure, flexible, and reusable mobile application components.

Figure 3.

The VIC mHealth App System Architecture

Tier 1 - Presentation Logic Tier (i-DMZl): The Presentation Logic Tier is the IIS Web Application Server, and it consists of standard ASPX files and HTML pages. The function of this tier is to gather the requests from the presentation graphical user interface (GUI) and then forward the requests to the Business Tier once a user makes a request from a web browser. The Presentation Logic Tier will support different end-user devices (e.g. iPad, desktop, laptop, etc.). In return, the Presentation Logic Tier receives the results/output from the Business Tier, and transforms the results into readable formats and forwards data back to the Presentation GUI.

Tier 2 - Business Tier (i-DMZ2): The Business Tier is the brain of the VIC system. It contains the business logic, business rules, user security, validation rules and processing rules of the functions provided by the application. For example, once information is received from the Presentation Logic Tier, the information is validated against the predefined business and validation rules and business logic. If the information meets all the criteria, the information is forwarded to the Data Tier. The Business Tier also generates confirmation codes and forwards it back to the Presentation Logic Tier. The Business Tier will reside on the Business Server.

Tier 3 - Data Tier (i-DMZ3 (SQL Server 2012): The Data Tier handles the storage and retrieval of the information in the database. It can save and retrieve information from the database. Microsoft SQL Server 2012 Enterprise Edition will be the Database Management System (DBMS) for the proposed application.

Text-to-Speech.

We wanted to create a patient-centered easy-to-use IC tool that is acceptable by all users. A tablet with text-to-speech interfaces addresses literacy issues and makes the IC process an option for inexperienced computer users. Text-to-speech translation is a key feature of VIC and is achieved by online and automated text-to-speech translation. One way to add the audio functionality to VIC is to record the audio associated with textual content of every screen in waveform and then play it back when the screen is displayed. However, this approach needed significant time and effort to record and edit the audio. In addition, we will require fresh recording every time the text on this screen is edited or changed. This would have slowed down the development and reduced the quality of the App. Our challenge was to find a low-cost, efficient solution to translate text in English into speech in high quality audio without compromising App performance. A more effective method was to use Text-To-Speech (TTS), a means of converting text to synthetic speech using a computer. In VIC, we used an online TTS solution (www.ispeech.org) to handle text to speech translation. For each text segment in the App that will be displayed on the screen, VIC requests (in realtime) an audio file translation associated with that text from ispeech.org through an API call. The API will then return the equivalent MP3 file VIC and VIC plays to the user.

VIC App Usability Evaluation.

After the VIC App was developed and tested, we wanted to ensure that the tool followed user interface standardscompliant coding practices for usability and acceptability. We performed a usability evaluation on VIC using a structured walk-through process with recognized usability principles. Usability refers to the ease in which the users can interact with tools. For the final design, we conducted the usability evaluation with nine representative asthma patients recruited from the YCAAD clinic. Patients were approached by the study coordinator and informed of this pilot study and offered the choice to participate voluntarily. If they chose to participate in the study, then they were scheduled for a study visit at a later convenient date and time in our Medical Simulation Center. Usability evaluation sessions were conducted in one-on-one settings to gather performance and satisfaction data. We evaluated the extent to which the application’s user interface is functioning according to the user requirements in the design specification to ensure that user needs are met. On the study visit, participants were reminded of the study protocol, study purpose, and patient’s role.

At the beginning of the session, a description of the study and the order of activities were read to participants. Each participant was asked to sign the consent form before participating in the study. In addition, they were asked to fill a demographic survey and a Computer Efficacy Scale (CES). Participants were told that the session will be audio and video recorded and the iPad must remain within the view of the above recording camera, for future analysis of potential on-screen inefficiencies. Participants were provided with a headphone in keeping with the intended future use of the VIC in the clinical setting. The participants were asked to review the VIC tool on the iPad in the presence of a researcher, while being videotaped, and share their perceptions of the application by speaking out loud. Participants were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire, CES, before they use VIC. For CES, participants were asked to rate their confidence about using the new technology on the scale of 1–10 (1= not at all confident and 10= completely confident) for each of the listed condition26. Additionally, they completed a system usability scale (SUS) and supplemental quantitative/qualitative data gathering, after using VIC. The SUS, created by John Brooke, is an industry standard, quick and reliable tool for measuring usability that can be used for small sample sizes27. The validated SUS is a ten item Likert Scale that measured user attitude, effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction with the application. A short post-use interview was conducted to allow for additional qualitative feedback from the participants. In this phase, participants were asked open-ended questions and probed for recommendations to enhance VIC usability. At the end, participants were rewarded with a gift card for $15 as appreciation for participation. Our study was reviewed and approved by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee (IRB).

Quantitative data was analyzed as numerical indicators and summarized using common descriptive statistics appropriate for discrete and continuous data. Non-numerical indicators were analyzed using qualitative methods. Key results were used to 1. Modify the VIC system to make it more usable and acceptable in terms of system’s design; and 2. Normalize VIC by reducing process and structural problems. We conducted data analysis by using audio and video recording, user screen capture, note-taking, and participant survey. Key usability measures included both qualitative and quantitative outcome measures. These include effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction.

Usability Evaluation Results.

In this section, we will list our main results of the usability evaluation based on using UCD approach for the development and evaluation of the VIC mHealth App. We found that the UCD approach was appropriate for VIC development. It provided hybrid techniques for requirement gathering and analysis and to create the initial and conceptual design of the VIC App with the patient in mind. Moreover, UCD approach was instrumental in guiding us through various stages of the development including conducting focus groups, design and development of mockup screens and prototypes, development of the VIC system, and usability evaluation of VIC App.

All 9 participants (4males and 5 females) completed the VIC usability study. All participants reported having at least a high school education (Table 3). All had access to both a desktop or laptop computer and reported having above 50% confidence in adapting to a new technology. Income brackets were largely similar with most sample participants identifying themselves as middle-class and most were Caucasian with only 1 African American and 1 Asian American.

Table 3.

Sample Demographic

| Factor | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 66.7% (6) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 11.1% (1) |

| Mexican American | 11.1% (1) |

| Other | 11.1% (1) |

| Age (years) | |

| 21-45 | 33.3% (3) |

| 45-64 | 33.3% (3) |

| 65-74 | 22.2% (2) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 44.4% (4) |

| Female | 55.6% (5) |

| Education | |

| High school graduate | 11.1% (1) |

| At least some college | 11.1% (1) |

| At least Bachelor’s degree | 77.8% (7) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 55.6% (5) |

| Separated or divorced | 33.3% (3) |

| Never married | 11.1% (1) |

| Household income | |

| $30,000-$49,000/year | 22.2% (2) |

| $50,000-$69,000/year | 22.2% (2) |

| $70,000-$89,000/year | 0.0% (0) |

| $90,000 or more/year | 55.6% (5) |

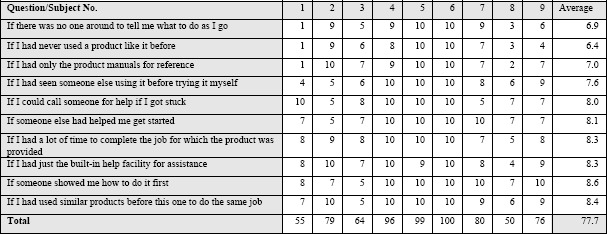

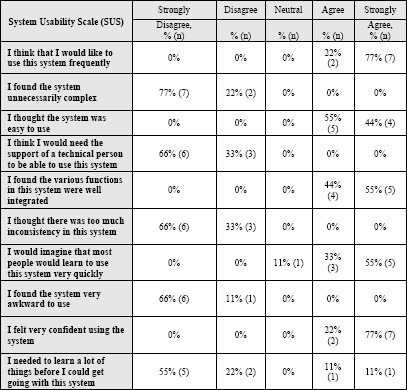

The average CAS normalized score was nearly 78, indicating that the sample was relatively not anxious about using computers and adequately self-sufficient when it came to technology use (Table 2) 26 The average SUS normalized score for all participants was 90th percentile, which is above the industry benchmark of 68th percentile (Table 4). All users reported that the user interface of the VIC mhealth tool was appropriate and easy to use, given that all subjects gave either a 4 or 5 when it came to ease of use and future implementation.

Table 2.

Computer Efficacy Scale (CES): confidence about using the new technology on the scale of 1 – 10 (1= Not at all confident and 10= Completely confident)

|

Table 4.

SUS: System Usability Scale

|

Overall, the users were successful in completing the tasks with a favorable impression of the VIC system. They had little difficulty understanding how to perform navigating the screens, playing and pausing videos and illustrations, showing and hiding the close caption text, playing or muting audio, answering the quiz questions, agreeing or disagreeing to participate, and signing the consent with their fingers on the iPad screen. However, they had some difficulty reading the text and suggested increasing the font size to make it more readable and to add audio to the quiz answer screen.

The most frequently suggested change to the mhealth tool was to change the Play button and make it indicate sound control. Also, to alter the interface such that hovering over the icon would show the icon’s meaning. All participants preferred the use of headphones with VIC, felt they had ample time to complete the program, and would strongly recommend its use in future clinical practice. Recommendations from the usability evaluation for improving the user experience included using larger font and control on-screen messaging to let users know how to proceed in the system; providing audio to the quiz screen and to read out load the quiz question and answer.

Conclusion

The use of mHealth can be successful in delivering health communications. More specifically, in developing a usable, acceptable, and efficient tool to deliver the IC process. Care must be taken to address the challenges that come with designing a new IC tool. One such challenge is ensuring that the new IC tool improves patient comprehension. This study focused on testing the feasibility of developing and evaluating such a tool.

Using the UCD approach we were able to design, develop, and evaluate a highly interactive mHealth App to deliver the IC process. The UCD approach facilitates working with multiple stakeholders and helped us plan and execute many tasks including requirement gathering and analysis, conceptual design, focus groups, design and development of mockups screen and prototype, usability evaluation of the prototype, development of the VIC system, rapid prototyping, and usability evaluation of VIC App.

Our Web-based mobile VIC App with virtual coaching and text-to-speech audio translation and iPad® interface offers some compelling ways to surmount existing implementation barriers. Our App architecture intentionally and readily addresses literacy issues and patients’ needs in the informed consent process. This has important implications for facilitating more meaningful and broader implementation of an IC tool, enhancing patient comprehension, and reducing provider burden engaging patients in an interactive IC process. Our user-focused development approach resulted in a product that is usable, acceptable, and efficient. Overall, the VIC mHealth tool had high usability as rated by the representative asthma patients. Successful research increasingly requires multi-disciplinary and interdisciplinary teams. Our team has unique and complementary backgrounds encompassing: HIT, human computer interaction, mHealth, UCD, UX evaluation, system design and architecture, human subjects protection, and clinical, and translational research. This study presents how our team is a success story of interdisciplinary collaboration between several entities.

Possible future directions include assessing the VIC tool capabilities for different chronic. Potential modifications include improving the reusable infrastructure of the VIC App by using a larger and more diverse sample size to create a more patient-centered mHealth tool. In the longer term, we are also interested in assessing whether the VIC predicts more positive health outcomes for patients.

Acknowledgements

Project described was made possible by grant from AHRQ R21 HS23987. We would like to acknowledge the two asthma patients who in the research team as co-researchers included Sheinea Doram (a finance associate with moderately severe asthma), and Judy Kaya (a former nurse with severe asthma). This publication was made possible by the Yale CTSA grant UL1TR000142 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sci. (NCATS), NIH.”

References

- 1.Jefford M, Moore R. Improvement of informed consent and the quality of consent documents. The Lancet Oncology. 2008;9(5):485–93. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paterick TJ, Carson GV, Allen MC, Paterick TE. Medical Informed Consent: General Considerations for Physicians. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2008;83(3):313–9. doi: 10.4065/83.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raich PC, Plomer KD, Coyne CA. Literacy, comprehension, and informed consent in clinical research. Cancer investigation. 2001;19(4):437–45. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100103137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller FG, Emanuel EJ. Quality-Improvement Research and Informed Consent. Waltham, MA, ETATS-UNIS: Massachusetts Medical Society. 2008:3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0800136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartgerink B, McMullen P, McDonough J, McCarthy E. A guide to understanding informed consent1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedlander JA, Loeben GS, Finnegan PK, Puma AE, Zhang X, EF de Zoeten, et al. A novel method to enhance informed consent: a prospective and randomised trial of form-based versus electronic assisted informed consent in paediatric endoscopy. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2011;37(4):194. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.037622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baer AR, Good M, Schapira L. A New Look at Informed Consent for Cancer Clinical Trials. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2011;7(4):267–70. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. Jama. 2012;307(15):1583–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tate EB, Spruijt-Metz D, O’Reilly G, Jordan-Marsh M, Gotsis M, Pentz MA, et al. mHealth approaches to child obesity prevention: successes, unique challenges, and next directions. Translational behavioral medicine. 2013;3(4):406–15. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0222-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar S, Nilsen WJ, Abernethy A, Atienza A, Patrick K, Pavel M, et al. Mobile health technology evaluation: the mHealth evidence workshop. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(2):228–36. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sreenivasan G. Does informed consent to research require comprehension? Health Care Ethics in CA. 2011;335 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baum NH, Kelly T, editors. Automating Informed Consent-Are You Overlooking a Safety Opportunity? 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schenker Y. Interventions to improve patient comprehension in informed consent for medical and surgical procedures: a systematic review. Medical Decision Making. 2011;31(1):151. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10364247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Marder SR, Liberman RP, Mintz J. Informed consent: assessment of comprehension. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1508–11. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huber J, Ihrig A, Yass M, Bruckner T, Peters T, Huber CG, et al. Multimedia Support for Improving Preoperative Patient Education: A Randomized Controlled Trial Using the Example of Radical Prostatectomy. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2012:1–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2536-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornoiu A, Beischer AD, Donnan L, Graves S, R de Steiger. Multimedia patient education to assist the informed consent process for knee arthroscopy. ANZ journal of surgery. 2011;81(3):176–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jimison HB, Sher PP, Appleyard R, LeVernois Y. The use of multimedia in the informed consent process. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 1998;5(3):245–56. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1998.0050245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abras C, Maloney-Krichmar D, Preece J. User-centered design. Bainbridge, W Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction Thousand Oaks. Sage Publications. 2004;37(4):445–56. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witteman HO, Dansokho SC, Colquhoun H, Coulter A, Dugas M, Fagerlin A, et al. User-centered design and the development of patient decision aids: protocol for a systematic review. Systematic Reviews. 2015;4(1):11. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyng KM, Pedersen BS. Participatory design for computerization of clinical practice guidelines. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2011;44(5):909–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer RE. Cognitive Theory and the Design of Multimedia Instruction: An Example of the Two-Way Street Between Cognition and Instruction. New directions for teaching and learning. 2002;2002(89):55–71. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sobel RM, Paasche-Orlow MK, Waite KR, Rittner SS, Wilson EA, Wolf MS. Asthma 1-2-3: a low literacy multimedia tool to educate African American adults about asthma. Journal of community health. 2009;34(4):321–7. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braithwaite RS, Caplan A. Does patient-centered care mean that informed consent is necessary for clinical performance measures? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2014;29(4):558–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2645-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kincaid JP. Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel. 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris BN, John BE, Brezin J, editors. CHI’10 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM; 2010. Human performance modeling for all: importing UI prototypes into CogTool. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laver K, George S, Ratcliffe J, Crotty M. technology self efficacy: reliability and construct validity of a modified computer self efficacy scale in a clinical rehabilitation setting. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2012;34(3):220–7. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.593682. Rehabilitation. 2012;34(3):220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brooke J. SUS: a retrospective. J Usability Studies. 2013;8(2):29–40. [Google Scholar]