Abstract

Aim:

The present study aimed to compare the remaining dentin thickness (RDT) and fracture resistance of conventional and conservative access and biomechanical preparation in molars using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT).

Methodology:

A total of 60 freshly extracted human molars were selected and were randomly divided into two groups of conventional and conservative access preparation group (n = 30). Samples were subjected to pre-CBCT scan at the pericervical region for the measurement of total dentin thickness. For the conventional group, samples were accessed and biomechanical preparation was done using K3 XF file. For conservative group, samples were accessed using CK microendodontic burs using a dental operating microscope and biomechanical preparation was done using self-adjusting file. After obturation and postobturation with nanohybrid composite restoration, samples of both groups were subjected to post-CBCT scan at pericervical region for the measurement of RDT. The samples were then loaded to fracture in the Instron Universal Testing Machine, and the data were analyzed using paired sample t-test and independent sample t-test.

Results:

The mean RDT was less in conventional group than conservative group. Pericervical dentin was preserved more in conservative group. The statistical difference among both the experimental group was highly significant (<0.001). The mean load at fracture was less in conventional group than conservative group (<0.001).

Conclusion:

Coronal dentin was conserved in molars when accessed through conservative than through conventional. The dentin conservation afforded an increased resistance to fracture in conservative group which is doubled the fracture resistance in conventional group.

Keywords: Cone-beam computed tomography, conservative access cavity, remaining dentin thickness, self-adjusting file

INTRODUCTION

Root canal treatment is aimed at removing harmful pathogens from the root canal and to create an environment, in which any remaining organism cannot endure. A successful result of an endodontic treatment depends on proper cleaning and shaping, proper irrigation and disinfection, and proper obturation with complete seal of the root canal. To fulfill all the above-mentioned objectives, correct access cavity preparation is mandatory. The successful endodontic treatment merely depends on precise, proper evaluation of this step.[1]

These principles of the cavity include “outline,” “convenience,” “retention,” and “resistance” form with “toilet of the cavity” and “elimination of residual caries” are additional principles. Hence, the traditional access preparation is done with the round carbide bur directed along the long axis of the tooth till it penetrated the roof of the pulp chamber, and then, the deroofing of the entire pulp chamber is done with tapered fissure bur along with the divergent wall toward occlusal surface. This preparation will provide straight-line access to the root canal. After the access, opening the biomechanical preparation of the root canal to be done with the files and irrigants.[2] With the introduction of nickel–titanium (Ni–Ti) rotary instrument, root canals are prepared by crown-down method which involves enlargement of coronal part of the root by Gates Glidden (GG) drills or orifice shapers. Many Ni–Ti file systems are available in the market such as K3 and Protaper universal. K3 XF Ni–Ti files are the modified version of the existing K3 file system. The file is prepared from the R-phase which provides more safety, canal centering ability, new level of flexibility, and resistance to cyclic fatigue. As it is one of the most commonly used rotary file systems, we have included in our study as one of the experimental group.[3,4,5]

Conventional access preparation will lead to more sacrifice of additional tooth structure which ultimately might lead to decrease fracture resistance of tooth.

To overcome the above-mentioned problems, a new concept of endodontic access cavity has been proposed on dentin preservation by David Clark and Khademi. It is mainly concentrated on preservation of most crucial pericervical dentin and some of the part of the pulp chamber roof (Soffit).[6] These preparations are done under the dental operating microscope (DOM).

Pericervical dentin is located 4 mm above the crestal bone and extending 4 mm apical to the crestal bone. It acts as the “neck” of the tooth. It is important for two reasons: for ferrule and to improve fracture resistance, whereas soffit is a small piece of roof around entire coronal portion of the pulp chamber. The soffit behaves like metal band surrounding barrel. It must be maintained to avoid the collateral damage that usually occurs, namely, the gouging of lateral walls.[1,2,6,7,8]

Conservative access cavity preparation is done by 1 mm of anatomic flattening than 45° angle of penetration until reaching the dentinal map with the help of more conservative CK microendodontic access preparation burs.[5] According to the concept of “minimal invasive endodontics (MIE),” excessive enlargement of radicular portion of the dentin is undesirable.[5]

Self-adjusting file (SAF) is a thin-walled compressible hollow cylindrical file 1.5 mm in diameter, made up of a very thin Ni–Ti lattice. The file is made in such a way that it takes up the shape of the canal both longitudinally and cross-sectionally. It also applies constant soft pressure on the canal walls resulting in maximum preservation of radicular dentin. The SAF comprises inbuilt irrigating device (VATEA system) which helps to obtain total disinfection by continuous flow of irrigating solutions into the canal.[9,10]

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) is a diagnostic imaging modality that provides high-quality, accurate three-dimensional representations of the osseous elements of the maxillofacial skeleton able to provide small field of view images at low dose for endodontic diagnosis, treatment guidance, and pre- and posttreatment evaluation.[11]

The scarce literature is available on combination of conservative endodontic access preparation along with mechanical preparation of root canals with SAF with conventional methods of access and biomechanical preparation. Hence, the study is aimed to compare and evaluate the remaining dentin thickness (RDT) by CBCT and fracture resistance of conventional access preparation with conservative access cavity preparation with biomechanical preparation in the molar teeth.

The null hypothesis is there is no difference in the fracture resistance and RDT between the conventional access preparation and conservative access preparation with biomechanical preparation.

METHODOLOGY

The ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethical committee. A total of 60 extracted mandibular molars for periodontal purpose were used for the study. Teeth with extensive caries, fractures, internal or external resorption, and calcifications were excluded from this study. Teeth were disinfected with 0.5% chloramine T and stored in distilled water till further use. Then, teeth were divided randomly into two groups (n = 30) by flip coin method.

Group 1 Conventional endodontic cavity

Conventional access cavity preparation was done using Endo Access Bur and Endo-Z bur gaining straight-line access, and the working length was determined using 10 K-file subtracting 1 mm after the file was visible from the apex. Cleaning and shaping was done with K3XF rotary Ni–Ti file system at 350 rpm with coronal shaping 25.12 size and 25.04 apical size in conjugation with irrigation using 5.25% NaOCl and normal saline.

Group 2 Conservative endodontic cavity

Conservative access cavity preparation was done using DOM (×16) magnification with CK burs no. 2 and 5 preserving soffit and pericervical dentin with 1-mm anatomic flattening followed by entry at 45° penetration angle to reach the dentinal map. Working length was determined with 10 K-file similar to group 1. Cleaning and shaping was done SAF using manufacturing instruction after apical preparation by 20 K-file in conjugation with irrigation using 5.25% NaOCl and normal saline.

Canals were then dried using paper points and obturated using gutta-percha with AH Plus sealer using lateral condensation technique and were sealed coronally using nanohybrid composite.

Cone-beam computed tomography analysis

Pre- and postoperative CBCT scans (DENT-CAT) were taken to evaluate the RDT at the cementoenamal junction (CEJ).

Fracture resistance

Post-CBCT analysis of the specimens were thermocycled (500 cycles) and then stored in an incubator at 37°C for 24 h. Samples were then mounted in acrylic blocks unto 1.5 mm apical to the CEJ using light body polyvinyl siloxane material to cover the root surface. Fracture resistance was checked for both the groups by applying the force of 1 mm/min using “universal testing machine” until fracture and was calculated in Newtons (N).

Statistical analysis

The obtained values were statistically analyzed with paired sample t-test and independent sample t-test using SPSS Software (IBM SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

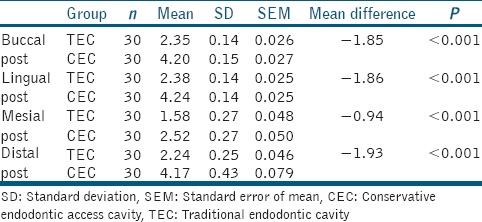

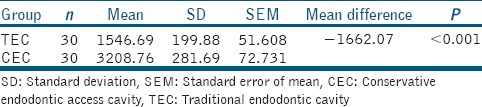

CBCT scans revealed a statistically significant reduction in RDT of all the roots of both experimental groups after access preparation and biomechanical preparation intergroup comparison showed statistically significant more RDT in the conservative group than conventional group mean difference being 1.60 mm (P < 0.001) [Table 1]. Fracture resistance also revealed a statistically significant difference between both the groups, with conservative group showing comparatively higher fracture resistance with a mean difference of 1662.07 N [Table 2].

Table 1.

Mean difference of remaining dentin thickness at cemento-enamel junction between two experimental groups and its level of significance

Table 2.

Mean load at fracture of two experimental group and its level of significance

DISCUSSION

Root canal therapy is a sequence of treatment for the infected pulp of a tooth which results in the elimination of infection and the protection of the decontaminated tooth from future microbial invasion.[12] Access cavity preparation is one of the most important part and the main objective is to identify the root canal entrances for subsequent biomechanical preparation and obturation of the root canal system. Good access cavity design is therefore imperative for quality endodontic treatment.[13,14,15] Applying the concept of “extension for prevention” facilitates treatment procedures but removes valuable dentin at the cervical region, leaving tooth structure biomechanically compromised after endodontic treatment.[16]

MIE is a concept for preserving healthy coronal, cervical, and radicular tooth structure. Advances such as operating microscopes and Ni–Ti instruments have enabled this progress. The novel conservative endodontic cavity (CEC) involves preservation of the pulp chamber roof and pericervical dentin as described by Clark and Khademi.[2] To achieve these objectives, use of round burs and GG burs should be avoided as they are not self-centered, create gouging which leads to difficulties in negotiating the canals and are not minimal invasive as it cuts excessive pericervical dentin and soffit. To fulfill the goal EndoGuide burs also called as CK burs by Dr. Clark and Khademi are used. According to Lenchner NH et al.,[8] EndoGuide bur is ideal for magnification driven endodontics. In the present study, DOM was used visualize through minimal cavity preparation in magnification to prepare minimal invasive access cavity, locate the orifices of the root canal whose access is not in straight line, to locate any calcification and obliteration, to reduce the chances of any procedural errors such as gouging and strip perforation, and to preserve more pericervical dentin.

The introduction of rotary root canal instruments, significantly changed endodontics, with the benefits such as M-wire technology and increase in its taper size. According to study by Ya Shen et al.[17] M-wire contains all 3 crystalline phase including martensitic, R-phase, and austenite. The use of greater taper files (0.04, 0.06, 0.08, 0.10, and 0.12) allows more apical placement of the irrigant. In the present study, K3 XF file was used to prepare the canals in conventional endodontic access cavity group as it is one of the recommended rotary system in day-to-day practice and provides safety and self-centering, flexibility and resistance to cyclic fatigue, super elasticity, and shape memory.

In the present study, we used SAF as it adapts itself to the canal's original anatomy and shape longitudinally as well as cross-sectionally. The abrasive surface of SAF lattice works like sand paper, and it removes the dentin by scrubbing and scraping rather than cutting of dentin chips thus preserves more radicular dentin. CBCT was used to evaluate for the exact dentin thickness preoperative and postoperative to endodontic access cavity preparation. CBCT is a well-validated method for evaluating different aspects of root canal preparation, the most important features of CBCT are its nondestructive nature and its quantitative accuracy, of the specimens analysis of images three dimensionally.

Intact mandibular molars were selected as these teeth are under constant crushing load of mastication and bears maximum load.

Thermocycling of the samples was done as it simulates in vitro, thermal changes that occur in the oral cavity and it is widely accepted method in in vitro microleakage studies.

To simulate the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone, a layer of light body elastomeric impression material polyvinyl siloxane paste and polystyrene resin blocks were used to test the root fracture resistance in the study.[18]

The result of present study shows that there is statistical significant difference (P < 0.001) in the RDT before and after the access cavity preparation and biomechanical preparation at CEJ between conventional and conservative endodontic access group. Mean RDT was less in conventional endodontic access cavity group than conservative endodontic access cavity group.

The mean load at fracture was less in conventional endodontic access cavity group than conservative endodontic access cavity group. The samples under conservative endodontic access cavity group show mesiodistal fracture while the samples under conventional endodontic access cavity group shows cuspal chipping pattern.

The result of the present study is in accordance with the previous study performed by Krishan R et al.[1] and Varghese et al.[19]

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of coronal dentin was conserved in molars and fracture resistance was higher when accessed through conservative endodontic access cavity (CEC) than conventional endodontic access cavity. The dentin conservation afforded an increased resistance to fracture in conservative endodontic access cavity group which is doubled the fracture resistance in conventional endodontic access cavity preparation group.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krishan R, Paqué F, Ossareh A, Kishen A, Dao T, Friedman S, et al. Impacts of conservative endodontic cavity on root canal instrumentation efficacy and resistance to fracture assessed in incisors, premolars, and molars. J Endod. 2014;40:1160–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark D, Khademi J. Modern molar endodontic access and directed dentin conservation. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54:249–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.da Frota MF, Espir CG, Berbert FL, Marques AA, Sponchiado-Junior EC, Tanomaru-Filho M, et al. Comparison of cyclic fatigue and torsional resistance in reciprocating single-file systems and continuous rotary instrumentation systems. J Oral Sci. 2014;56:269–75. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.56.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsujimoto M, Irifune Y, Tsujimoto Y, Yamada S, Watanabe I, Hayashi Y, et al. Comparison of conventional and new-generation nickel-titanium files in regard to their physical properties. J Endod. 2014;40:1824–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tyagi S, Choudhary E, Kabra P, Chauhan R. An in vitro comparative evaluation of fracture strength of roots instrumented with self-adjusting file and reciproc reciprocating file, with and without obturation. Int J Clin Dent Res. 2017;1:20–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark D, Khademi JA. Case studies in modern molar endodontic access and directed dentin conservation. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54:275–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark D, Khademi J, Herbranson E. The new science of strong endo teeth. Dent Today. 2013;32:112, 114, 116–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lenchner NH. Considering the “Ferrule effect”. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2001;13:102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hof R, Perevalov V, Eltanani M, Zary R, Metzger Z. The self-adjusting file (SAF). Part 2: Mechanical analysis. J Endod. 2010;36:691–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HC, Sung SY, Ha JH, Solomonov M, Lee JM, Lee CJ, et al. Stress generation during self-adjusting file movement: Minimally invasive instrumentation. J Endod. 2013;39:1572–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scarfe WC, Levin MD, Gane D, Farman AG. Use of cone beam computed tomography in endodontics. Int J Dent 2009. 2009:634567. doi: 10.1155/2009/634567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters OA, Peters CI, Basrani B. Cleaning and shaping the root canal system. In: Hargreaves K, Berman L, editors. Cohen's Pathways of the Pulp. 1st South Asia ed. New Delhi: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 209–79. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel S, Rhodes J. A practical guide to endodontic access cavity preparation in molar teeth. Br Dent J. 2007;203:133–40. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weine FS, editor. Endodontic Therapy. 5th ed. St. Louis, USA: Mosby; 1996. Access cavity preparation and initiating treatment; pp. 239–306. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford L, Rhodes JS, Ford HE. Root canal preparation. In: Dunitz M, editor. Endodontics Problem-Solving in Clinical Practice. 1st ed. London: Martin Dunitz Ltd; 2002. pp. 79–110. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murdoch-Kinch CA, McLean ME. Minimally invasive dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:87–95. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ya Shen, Hui-min Zhou, Yu-feng Zheng, Bin Peng, Markus Haapasalo. Current challenges and concepts of the thermomechanical treatment of nickel-titanium instruments. J Endod. 2013;39:163–72. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soares CJ, Pizi EC, Fonseca RB, Martins LR. Influence of root embedment material and periodontal ligament simulation on fracture resistance tests. Braz Oral Res. 2005;19:11–6. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242005000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varghese VS, George JV, Mathew S, Nagaraja S, Indiresha HN, Madhu KS, et al. Cone beam computed tomographic evaluation of two access cavity designs and instrumentation on the thickness of peri-cervical dentin in mandibular anterior teeth. J Conserv Dent. 2016;19:450–4. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.190018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]