Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Abstract

Background:

It is unknown whether recent legislation known as the Physician Payments Sunshine Act has affected plastic surgeons’ views of conflicts of interest (COI). The purpose of this study was to evaluate plastic surgeons’ beliefs about COI and their comprehension of the government-mandated Sunshine Act.

Methods:

Plastic surgeon members of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons were invited to complete an electronic survey. The survey contained 27 questions that assessed respondents’ past and future receipt of financial gifts from industry, awareness of the Sunshine Act, and beliefs surrounding the influence of COI on surgical practice.

Results:

A total of 322 individuals completed the survey. A majority had previously accepted gifts from industry (n = 236; 75%) and would accept future gifts (n = 181; 58%). Most respondents believed that COI would affect their colleagues’ medical practice (n = 190; 61%) but not their own (n = 165; 51%). A majority was aware of the Sunshine Act (n = 272; 89%) and supported data collection on surgeon COI (n = 224; 73%). A larger proportion of young surgeons believed patients would benefit from knowing their surgeon’s COI (P = 0.0366). Surgeons who did not expect COI in the future believed financial COI could affect their own clinical practice (P = 0.0221).

Conclusions:

Most plastic surgeons have a history of accepting industry gifts but refute their influence on personal clinical practice. Surgeon age and anticipation of future COI affected beliefs about the benefits of COI disclosure to patients and the influence of COI on surgical practice.

INTRODUCTION

Patients and policymakers are becoming more aware of potential financial conflicts of interest (COI) between surgeons and the medical industry.1 Within plastic surgery, national organizations in the United States such as the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) have developed COI policies that require leaders in the organization to disclose potential COI.2 The Physician Payments Sunshine Act (PPSA) that became federal law in January 2012 under the 2010 Affordable Care Act was both a response to this increased awareness and a call for improved transparency of potential COI in health care.3 The Act requires pharmaceutical and biomedical manufacturers to report annually on direct payments and other “transfers of value” made to physicians and teaching hospitals to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. In September 2014, the information on amounts received by individual physicians was made available on a publicly accessible Open Payments Database web site.

Previous survey research conducted before the Sunshine Act has produced conflicting information on the views of physicians surrounding COI. Surveys among surgeons and internists reveal that a majority in both groups consider industry-sponsored research to be biased.4 In the same study, a minority of surgeons was found to believe that physicians presenting at Continuing Medical Education–accredited events should be required to disclose financial agreements with companies.4 Consistent with these findings, surveys have also shown that physicians consider interactions with pharmaceutical representatives as productive and informative. However, many also believe that financial relationships with biomedical companies may introduce biased research findings among their physician peer groups.5–8 Physician opinions about gifts from pharmaceutical companies remain conflicted: while gifts may increase awareness about new therapies9 and are generally considered acceptable,10 physicians may not desire to make these gifts known to the general public.11

Research within plastic surgery using the Sunshine Act Open Payments Database suggests that approximately half of all plastic surgeons receive payments from drug or device manufacturers.12,13 Investigation of COI is particularly timely due to the large increase in funding by biomedical and pharmaceutical companies in response to sequestration and other federal funding research funding cuts.14 This growth in industry spending, combined with the information now made publicly accessible by the Sunshine Act, necessitates a study to evaluate current views of plastic surgeons surrounding financial COI.

Currently, it is unknown how plastic surgeons perceive COI in the wake of the recent Sunshine Act legislation. The purpose of this study was to assess the views of plastic surgeons about financial COI and to evaluate their understanding of the Sunshine Act. We hypothesize that a majority of plastic surgeons will have a favorable perception of COI. Furthermore, we hypothesize that views on COI and the Sunshine Act will be dependent on surgeon demographic factors and awareness regarding the influence of financial COI. Therefore, the aims of this study were to (1) survey plastic surgeon members of the ASPS; (2) assess surgeons’ awareness of and views on COI; (3) assess plastic surgeon awareness and views regarding the Sunshine Act; (4) evaluate how age influences views on COI; and (5) evaluate whether previous interactions or anticipated future engagements with biomedical industry influence views on COI and the Sunshine Act.

MATERIALS/PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design/Subjects/Setting

This was a cross-sectional study of plastic surgeons, both in academic and private practice, who are active members of the ASPS. Under ASPS survey distribution policy, approximately half of the “active” ASPS members (2,479 of 5,800 total active members) were randomly selected to receive an electronic survey.15 An active member is defined by ASPS as a plastic surgeon who is board certified by the American Board of Plastic Surgery, has completed the ASPS Membership process, and pays annual dues. Not included in this cohort are residents and fellows, associate/affiliate members, life members, life inactive members, and international members. Between June 2016 and August 2016, subjects were e-mailed an invitation by ASPS to complete an electronic survey. The purpose identified in the invitation was to “assess the views of plastic surgeons toward financial COI within their field, in addition to evaluating the surgeon’s understanding of the PPSA, which became federal law in 2012.” Two reminder e-mails were sent to subjects after the initial survey invitation.

Survey Design

The survey instrument was informed by reviewing the literature on COI and the Sunshine Act.4,5,16,17 It was designed to solicit surgeons’ perspectives on financial COI and their awareness of the Sunshine Act. Input from colleagues with expertise in survey design and from the ASPS staff was also solicited in developing the survey. A draft survey instrument was subjected to multiple rounds of edits and modifications to ensure clarity. To avoid the negative connotation associated with the phrase “conflicts of interest,” the instrument instead used descriptive and less judgmental terms such as “gift/monetary compensation,” or “financial ties” (eg, “Do you think that accepting gifts/monetary compensation affects your colleagues’ choice of instruments, devices, supplies, or medications they use or recommend for a surgery …”). The final survey contained 27 questions (see survey, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which displays the survey to assess the views of plastic surgeons towards financial COI within their field, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/A723). Questions for surgeons focused on the following areas: practice demographics, current and future receipt of financial gifts from industry, knowledge of the Sunshine Act, and attitudes surrounding the influence of COI on clinical practice.

Data Collection

Surgeons were ensured confidentiality through an approved survey collection application that recorded results anonymously. This study was approved by our hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB00091046).

Data Analysis

Demographics are summarized using frequencies and proportions. To examine the associations between survey questions and patient demographics, a chi-square test of independence was used. To control for a potential inflated type I error rate, P were adjusted using a false discovery rate of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.3. Adjusted P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic Information

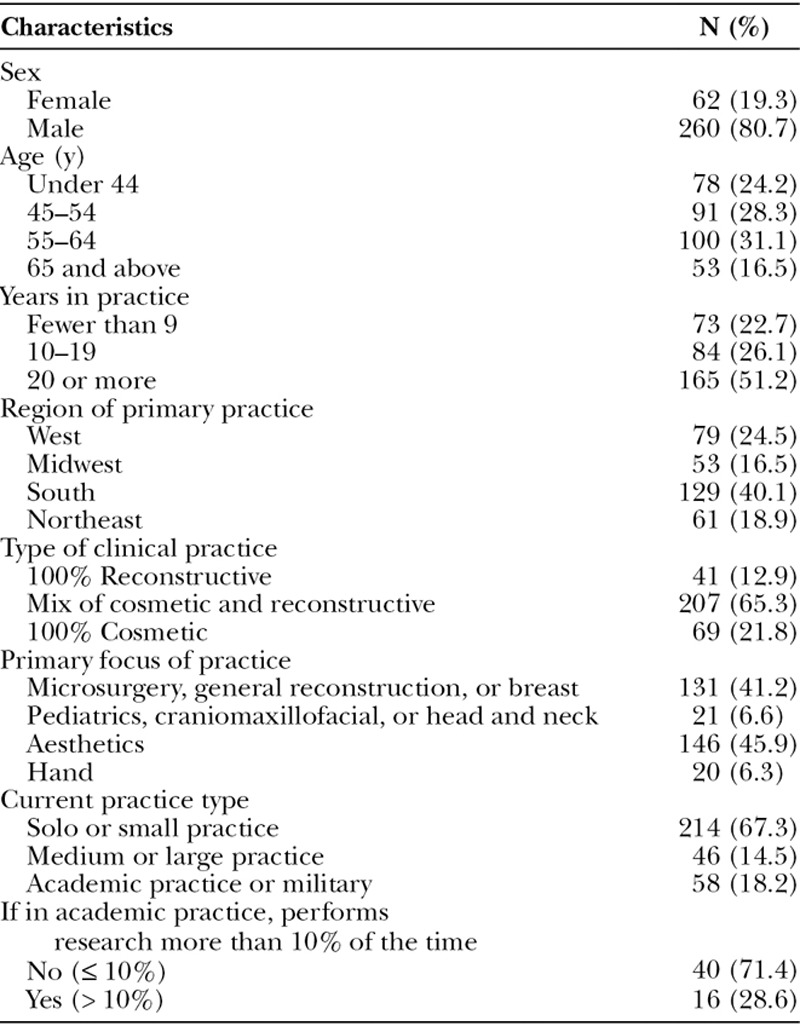

A total of 322 individuals completed the survey, resulting in a response rate of 13.0% (total n = 2,479). A majority of respondents were male (n = 260; 81%) and practicing in a mixed cosmetic and reconstructive clinical practice (n = 207; 65%; Table 1). Solo or small private practices were most common (n = 214; 67%) with a focus on microsurgery, general reconstruction, or breast surgery (n = 131; 41%) or aesthetics (n = 146; 46%).

Table 1.

Demographics

Surgeon Awareness of COI

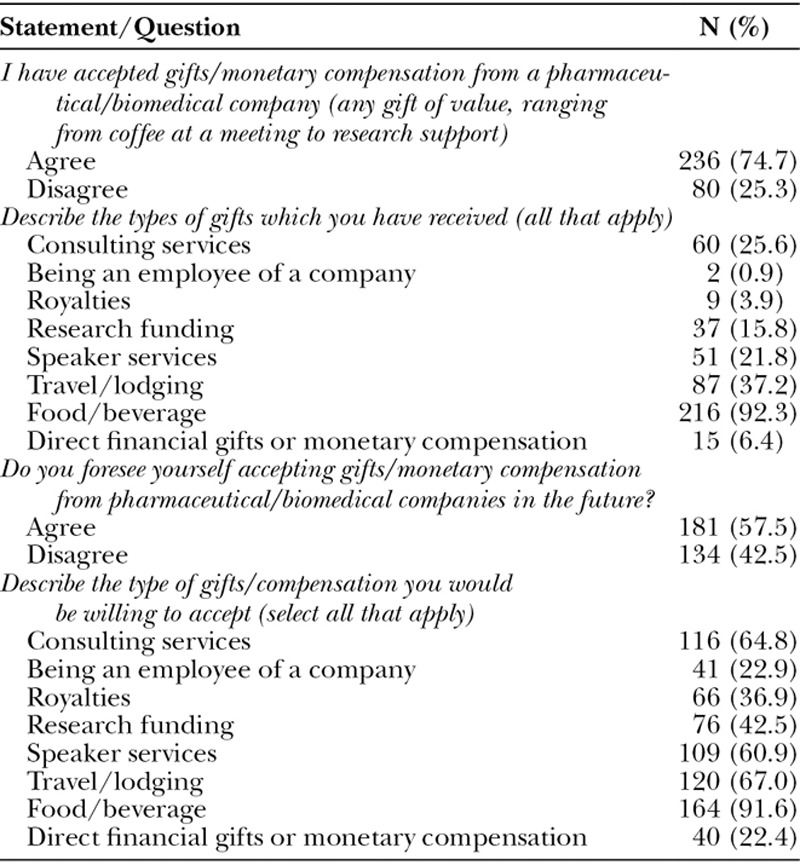

The majority of surgeons had a history of engaging with the biomedical industry (n = 236; 75%; Table 2). Most agreed that they would accept gifts in the future (n = 181; 58%). They reported being willing to receive almost all types of gifts, in particular food/beverages, travel/lodging, consulting fees, and speaker fees (n = 162, 92%; n = 120, 67%; n = 116, 65%; and n = 109, 61%, respectively).

Table 2.

Surgeon Awareness of COI

Surgeon Views on COI

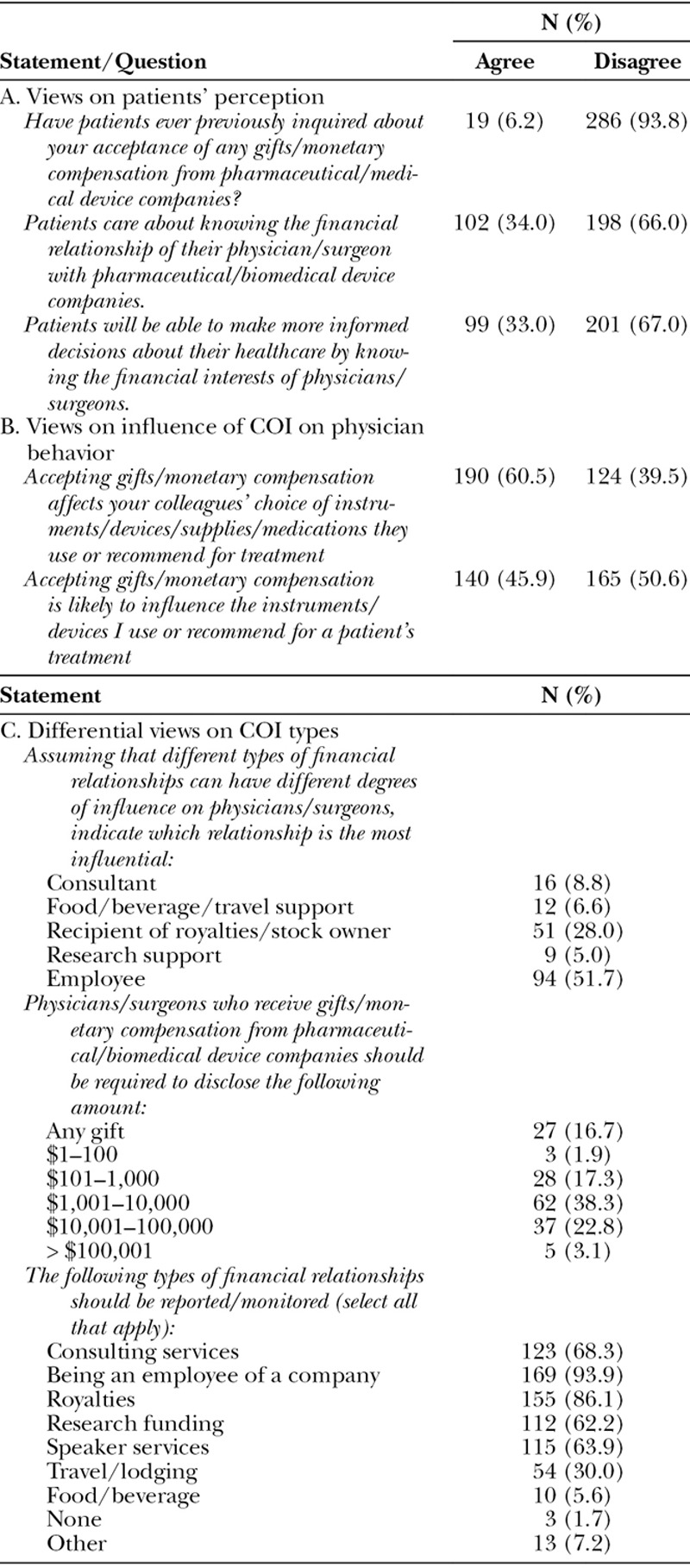

Most surgeons believed that patients were not interested in knowing about the financial relationship of their providers with biomedical companies (n = 198; 66%; Table 3). When asked whether financial COI would influence their own medical practice, approximately half of the respondents said no (n = 165; 51%). However, a majority of respondents agreed that financial COI would affect the medical practices of their colleagues (n = 190; 61%). Surgeons did not consider all types of COI to be equally influential on provider behavior. Being an employee of a company (n = 94; 52%) and receiving royalties or owning stock (n = 51; 28%) were seen as the most influential forms of financial relationships.

Table 3.

Surgeon Views on COI

Surgeon Views on the Sunshine Act

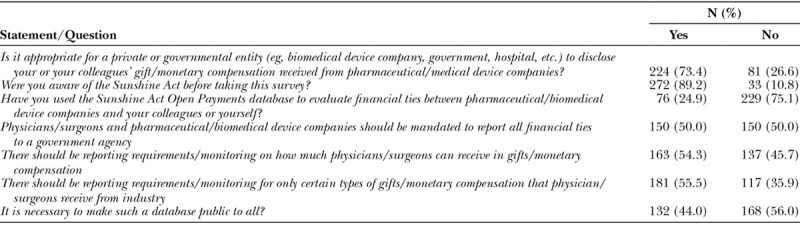

Most respondents agreed that it is appropriate for regulatory organizations to collect COI data on surgeons (n = 224; 73%; Table 4). However, there was disagreement as to whether these agreements should be reported to a government agency (n = 150 agreed; 50%) or whether the database should be made public (n = 132 agreed; 44%). Most respondents agreed that only certain types of COI (n = 181; 56%) or certain amounts (n = 163; 54%) should have reporting requirements.

Table 4.

Surgeon Views on the Sunshine Act

Association between Age and Views on COI/Sunshine Act

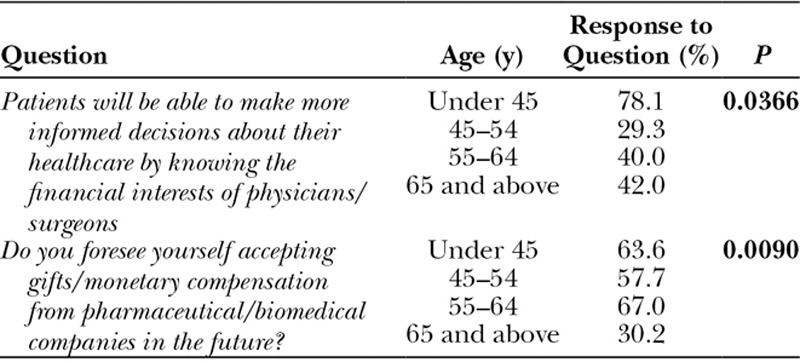

The age of respondents affected whether they agreed that patients will make more informed decisions if they know the COI of their surgeon (P = 0.0366; Table 5). Age also affected whether respondents saw themselves accepting compensation from companies in the future, with fewer older surgeons foreseeing future gifts (P = 0.0090).

Table 5.

Association between Age and Views on COI/Sunshine Act

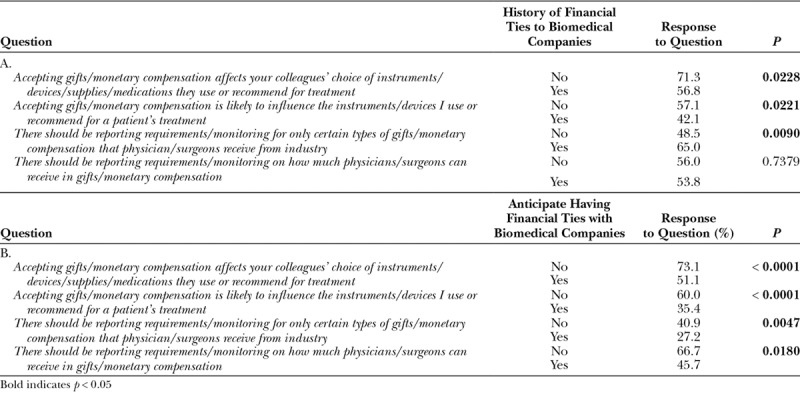

Association between Biomedical Financial Ties and COI

Surgeons with prior financial ties to biomedical companies believed that financial COI affect colleagues’ practice patterns (P = 0.0228) but had no influence on their own practices (P = 0.0221). However, the majority also believed that only certain types of compensation from industry need to be reported (P = 0.0090). Of those respondents who did not see themselves accepting compensation from companies in the future, 66% believed there should be requirements about or monitoring of the amount of gifts clinicians can receive. Surgeons who anticipated not having future engagements with industry also believed that colleagues’ (P < 0.0001) or their own (P < 0.0001) practices could be influenced by industry relationships (Table 6).

Table 6.

Association between History of Having or Willingness to Have Financial Ties with Biomedical Companies and Views on COI/Sunshine Act

DISCUSSION

Engagement between surgeons and industry is necessary. Prior research has demonstrated that industry plays a role in all aspects of medical research, such as sponsoring medical device and pharmaceutical clinical trials supervised by clinicians, providing reimbursement for physicians in consulting and speaking roles, and subsidizing medications for patients who would not ordinarily be able to afford treatment.18,19 Industry supports nearly 65% of all medical research in the United States.20 One study found that in a national sample of over 3,100 clinicians, 94% reported a relationship with industry.21 Another national survey reported that 92% of physicians had received free pharmaceutical samples in the past, and 61% received travel or food at no cost.22 Our analysis revealed that the majority of surgeons surveyed (> 70%) disclosed having prior financial ties to industry. This is an even higher number than that reported in a recent study by Chao and Gangopadhyay,13 which found that over 54% of all plastic surgeons in the United States had received payments from a biomedical company in 2014.

Although the prevalence of financial relationships between biomedical companies and plastic surgeons is significant, no prior study has assessed how plastic surgeons perceive these relationships. Furthermore, with the passage of the Sunshine Act, it is unknown how physicians perceive this new regulatory legislation aimed at providing transparency to physician-industry financial transactions. In our study, the majority of respondents noted the potential influence that financial COI could have on medical practice and research. In fact, respondents with no prior history of COI were more likely to believe (> 70%) that accepting compensation from industry is likely to influence patient management. Moreover, the majority of respondents believed that it was “appropriate for a private or governmental organization” to collect financial COI information from physicians. These findings suggest that plastic surgeons believe that COI influence physician behavior and that COI need to be managed appropriately. Indeed, a multitude of previous studies has found that financial COI have widespread implications for the health care system. COI are associated with the publication of positive research findings,6,23,24 including among plastic surgery investigators.25 COI also potentially affect national specialty guidelines. A 2011 British Medical Journal article reported that a large percentage of guideline panelists have substantial financial relationships with industry.26 Finally, COI have been shown to influence prescribing practices27,28 and the use of new surgical equipment that lacks safety and efficacy data.29 Wazana30 demonstrated a positive association between attending a drug company-sponsored continuing medical education program and the rates of prescribing the company’s medication.

Our study demonstrated that most surgeons believe they are immune to bias. More specifically, our analysis revealed that surgeons who anticipate having financial ties with industry believe that monetary compensation from industry is less likely to influence their treatment of patients when compared to colleagues (35.4% versus 51%). This mindset, as it pertains to COI, has also been shown in other specialties. In a survey of community obstetricians-gynecologists, Morgan et al.31 reported that respondents believed their peers were more likely to be swayed by drug samples than they were themselves (38% versus 33%). Steinman et al.10 surveyed medicine housestaff and found that 61% of residents believed they were immune to the influences of COI, whereas only 16% believed their peers could similarly avoid alterations in their behavior. Keim et al.9 showed that only 49% of emergency room residents believed that their prescribing patterns could be influenced by drug marketing, whereas 75% of their attending physicians believed this advertising affected the residents’ behavior. Our results suggest that ideas about future behavior—namely, whether surgeons expected to interact with the biomedical industry—may influence how surgeons perceive gifts from industry.

Most surgeons we surveyed agreed that not all COI have equal weight. Most respondents believe that only certain types or amounts of financial relationships need to be disclosed (> 55%). This is consistent with previous findings from our group that showed that only certain types of COI in plastic surgery research are associated with a positive publication bias. In particular, authors in the plastic surgery literature disclosing COI related to research funding, consultant or employee positions, and royalties or stock options were 1.31, 6.62, and 8.72 times more likely, respectively, than authors without COI to report positive research results. Holding consultantship or employee positions had a statistically significant association with the publication of positive research findings (P < 0.001).25 These findings suggest that certain relationships with industry—in particular surgeons holding consultant or employee positions—may be most critical to report under the Sunshine Act. Moreover, it may suggest that journal editorial boards should focus their energy on defining and highlighting COI that are at higher risk for bias, and making these clear to the scientific readership. Such changes may improve the effectiveness and efficiency of COI disclosures in biomedical science.

There are limitations to our study. Our response rate was low at 13.0% of the randomly selected cohort of active ASPS members. Although this number may seem low, existing research using ASPS surveys have typically recorded a response rate of between 9.1% and 25%.32–35 Our study may also have had a selection bias; respondents who read the e-mail prompt before agreeing to participate may have been more likely to have polarized opinions on the topic of COI. However, our study benefited from collecting data from the largest plastic surgery specialty group in the United States.15 Furthermore, our sample was highly representative of a variety of geographic locations, practice types, and years of experience (as shown in Table 1), so we believe that the effects of a selection bias may not be substantial. The distribution of respondent age36 and practice location37 among respondents was similar to previous studies describing these characteristics among practicing plastic surgeons.

Most plastic surgeons agree that financial COI are important determinants of physician behavior and should be regulated appropriately. Additionally, our report reveals that plastic surgeons view favorably the role of transparency in managing the physician-industry relationship. Although there may be disagreement regarding how regulation of COI should be structured and managed, plastic surgeons believe that transparency is important to ameliorate the deleterious effects of COI on physician behavior and research. Unfortunately, recent studies and findings suggest that current COI disclosures in journal articles and the PPSA database are inaccurate and potentially misleading.38,39 Therefore, our results highlight the importance of improving transparency in biomedical science and the need for our professional societies, journal editorial boards, and government entities to enact new mechanisms aimed at improving the effectiveness of COI disclosures throughout biomedical science. New regulatory tools such as author penalties for inaccurate disclosures (e.g., future publishing restrictions), independent auditing systems aimed at ensuring COI disclosure accuracy, or the tagging of scientific articles with new “Level of Conflict-of-Interest” labels to designate the types of COI reported (eg, dollar amount paid to authors) similar to the tagging of articles with Level of Evidence labels may be necessary.40 Of note, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has begun several educational initiatives that seek to improve physician awareness of the Sunshine Act, including continuing medical education modules, monthly industry forums, and a mobile phone application.16 These efforts may result in more widespread familiarity with the Open Payments program in the future and assist in improving its accuracy. Given plastic surgeons’ long-standing history of innovation and strong industry-surgeon partnerships, we believe that plastic surgery is uniquely poised to develop effective regulatory mechanisms aimed at improving COI transparency to our deserving patients, colleagues, and the general public.

CONCLUSIONS

A majority of surgeons surveyed have a history of accepting gifts from the biomedical industry and would accept such gifts in the future. A majority believed that financial COI would affect their colleagues’ choice of medical treatment but not their own medical practices. Most surgeons were aware of the Sunshine Act and agreed that regulatory bodies should compile data on surgeon COI. Young surgeons (< 45 years of age) believed that patients would benefit from knowing their surgeons’ financial COI. Surgeons who did not anticipate receiving gifts from industry in the future believed financial COI could influence their own or their peers’ surgical practice. These survey results suggest that plastic surgeons agree that more must be done to improve COI transparency in biomedical science.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the American Society of Plastic Surgeons for assistance with administration of the survey. No writing assistance was provided for this article.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online 4 April 2018.

Ms. Purvis and Dr. Lopez contributed equally to this work.

Institution to which work should be attributed: Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Johns Hopkins Hospital, 1780 E. Fayette St Bloomberg 7th Floor Rm 7314, Baltimore, MD 21231.

IRB Approval: This study was approved by our hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB00091046).

Disclosure: Dr. May, Jr, is a scientific consultant for Integra and Helios and an educational consultant for Johnson-Johnson–Mentor. Dr. Dorafshar receives research support and royalties from KLS Martin and research support from De Puy Synthes. For the remaining authors, none were declared. Funding from the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the Johns Hopkins Hospital was received for this article. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons assisted with administration of the survey. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the authors.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Clickable URL citations appear in the text.

REFERENCES

- 1.Camp M, Gross A, McKneally M. Patient views on financial relationships between surgeons and surgical device manufacturers: author response. Can J Surg. 2015;58:E8–E9.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Policy on conflicts of interest. Available at https://d2wirczt3b6wjm.cloudfront.net/Governance/conflict-of-interest-policy.pdf. Accessed November 6, 2017.

- 3.Kirschner NM, Sulmasy LS, Kesselheim AS. Health policy basics: the Physician Payment Sunshine Act and the Open Payments program. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:519–521.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Gara CJ, Rennick KC, Hanson J. Perceptions of conflict of interest: surgeons, internists, and learners compared. Am J Surg. 2013;205:541–545.; discussion 545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brett AS, Burr W, Moloo J. Are gifts from pharmaceutical companies ethically problematic? A survey of physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2213–2218.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman LS, Richter ED. Relationship between conflicts of interest and research results. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:51–56.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez J, Lopez S, Means J, et al. Financial conflicts of interest: an association between funding and findings in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136:690e–697e.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okike K, Kocher MS, Mehlman CT, et al. Conflict of interest in orthopaedic research. An association between findings and funding in scientific presentations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:608–613.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keim SM, Sanders AB, Witzke DB, et al. Beliefs and practices of emergency medicine faculty and residents regarding professional interactions with the biomedical industry. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1576–1581.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinman MA, Shlipak MG, McPhee SJ. Of principles and pens: attitudes and practices of medicine housestaff toward pharmaceutical industry promotions. Am J Med. 2001;110:551–557.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madhavan S, Amonkar MM, Elliott D, et al. The gift relationship between pharmaceutical companies and physicians: an exploratory survey of physicians. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1997;22:207–215.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed R, Lopez J, Bae S, et al. The dawn of transparency: insights from the Physician Payment Sunshine Act in Plastic Surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78:315–323.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chao AH, Gangopadhyay N. Industry financial relationships in plastic surgery: analysis of the Sunshine Act Open Payments Database. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:341e–348e.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwid SRG, Gross RA. Bias, not conflict of interest, is the enemy. Neurology. 2005;64:1830–1831.. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. About ASPS. Available at https://www.plasticsurgery.org/about-asps. Accessed November 6, 2017.

- 16.Agrawal S, Brown D. The Physician Payments Sunshine Act—two years of the Open Payments Program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:906–909.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenthal MB, Mello MM. Sunlight as disinfectant—new rules on disclosure of industry payments to physicians. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2052–2054.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia S, Brown D, Wall A, et al. Industry-sponsored clinical trials: the problem of conflicts of interest. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2013;98:32–35.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kjaergard LL, Als-Nielsen B. Association between competing interests and authors’ conclusions: epidemiological study of randomised clinical trials published in the BMJ. BMJ. 2002;325:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moses H, 3rd, Martin JB. Biomedical research and health advances. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:567–571.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell EG, Gruen RL, Mountford J, et al. A national survey of physician-industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2007;356: 1742–1750.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). National Survey of Physicians Part II: Doctors and Prescription Drugs. Menlo Park, Calif.: KFF; Available at https://www.kff.org/health-costs/national-survey-of-physicians-part-ii-doctors/. Accessed December 20, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289:454–465.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clifford TJ, Barrowman NJ, Moher D. Funding source, trial outcome and reporting quality: are they related? Results of a pilot study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2002;2:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez J, Juan I, Wu A, et al. The impact of financial conflicts of interest in plastic surgery: are they all created equal? Ann Plast Surg. 2016;77:226–230.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neuman J, Korenstein D, Ross JS, et al. Prevalence of financial conflicts of interest among panel members producing clinical practice guidelines in Canada and United States: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2011;343:d5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodwin MA. Introduction: institutional corruption and the pharmaceutical policy. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41:544–552.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wazana A. Gifts to physicians from the pharmaceutical industry. JAMA. 2000;283:2655–2658.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wall LL, Brown D. The perils of commercially driven surgical innovation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:30.e1–30.e4.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever just a gift? JAMA. 2000;283:373–380..10647801 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan MA, Dana J, Loewenstein G, et al. Interactions of doctors with the pharmaceutical industry. J Med Ethics. 2006;32:559–563.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choudry U, Kim N. Preoperative assessment preferences and reported reoperation rates for size change in primary breast augmentation: a survey of ASPS members. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:1352–1359.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hidalgo DA, Sinno S. Current trends and controversies in breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:1142–1150.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Losken A, Kapadia S, Egro FM, et al. Current opinion on the oncoplastic approach in the USA. Breast J. 2016;22:437–441.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melendez MM, Alizadeh K. Complications from international surgery tourism. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31:694–697.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker EP, Poley S, Ricketts T. The aging surgeon population: replacement rates vary by specialty and rural urban status. ACS HPR Institute. 2010;5:1–4.. Available at https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/advocacy/hpri/agingsurgpop.ashx. Accessed November 6, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heidekrueger PI, Juran S, Patel A, et al. Plastic surgery statistics in the US: evidence and implications. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016;40:293–300.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alhamoud HA, Dudum R, Young HA, et al. Author self-disclosure compared with pharmaceutical company reporting of physician payments. Am J Med. 2016;129:59–63.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okike K, Kocher MS, Wei EX, et al. Accuracy of conflict-of-interest disclosures reported by physicians. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1466–1474.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan D, Chung KC, Eaves FF, 3rd, et al. The level of evidence pyramid: indicating levels of evidence in plastic and reconstructive surgery articles. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:311–314.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]