Abstract

In this study, poly(2,5-bis(3,4-ethylenedioxythienyl)pyridine)/graphitic carbon nitride composites (poly(BPE)/g-C3N4) were prepared by an in situ chemical polymerization method. Composites were characterized by using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), ultraviolet–visible absorption spectra (UV–vis), X-ray diffraction (XRD), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Furthermore, electrochemical sensors were applied for the electrochemical determination of Cd2+ and Pb2+ using the differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) method. The results indicated that 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified electrode exhibited linear detection ranging from 0.12 to 7.2 μM and 0.08 to 7.2 μM for Cd2+ and Pb2+, with detection limits (S/N = 3) of 0.018 μM and 0.00324 μM. Interference analysis suggested that the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4-modified electrode can be applied for the detection of the Cd2+ and Pb2+ in real samples.

Keywords: poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite, DPV, electrochemical sensor, simultaneous detection, heavy metals

1. Introduction

Industrial waste water usually contains heavy metal ion—such as Zn2+, Cd2+, Pb2+, Cu2+ and Hg2+, the accumulation of these heavy metal ions in the human body can cause many chronic diseases [1,2,3]. For example, an imbalance of Zn2+ can reduce the amount of vitamin C and iron in the body, and cause iron deficiency anemia. Cd2+ accumulation to a certain value in the human body will lead to renal failure. Both lead and mercury affect the brain and nervous system, and result in mental retardation and brain damage in children [4]. Therefore, developing a simple and sensitive analytical method to detect these heavy metal ions is essential [5].

Up to now, various techniques have been used for detection of heavy metals, including inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry [6], inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry [7], atomic fluorescence spectrometry [8], atomic absorption spectrometry [9], surface enhanced Raman spectrometry, and electrochemical analysis technology [5,10]. However, most of these methods require expensive equipment, complicated procedures, and specialized training. Due to its high sensitivity, low operating cost, and fast response, electrochemical analysis has been considered as an effective technique for the determination of heavy metal ions. Among the current developed electrochemical approaches, anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) has been widely accepted as one of the most simple and efficient techniques, since it can be operated easily and can analyze several heavy metal ions simultaneously. The ASV includes two steps: the preconcentration step and the stripping step. During the preconcentration step, a low potential is applied, causing the metal ions to become concentrated on the working electrode and then reduced to their reduction states. During the stripping step, potential is changed from low potential to high potential, causing the reduced metal ions to change to their oxidation states, and the reduced metals are stripped from the electrode surface into the solution in their ionic forms. From the stripping peak potential and current, the metal ions can be qualitatively and quantitatively determined.

The sensitivity of the electrochemical sensor mainly relies on its electrochemical properties and the adsorption ability of ions. To improve the sensitivity of the electrode, novel sensing materials must be developed [5]. The ineffectiveness of conventional electrodes can be improved by modifying them with electrochemically active materials, such as metals [11], metal oxides [12], carbon materials [13], and conducting polymers [14]. Among them, carbon materials and their composites have great applications in the field of sensors [15,16,17]. In recent years, graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) has drawn much attention for its simple preparation, good chemical stability, high catalytic activity, and green environmental protection material [18]. Besides that, g-C3N4 shows a two-dimensional structure constructed from tri-s-triazine units connected by planar amino groups, and it can be considered as containing nitrogen-substituted graphite hexatomic ring units [19]. Moreover, it has a structure similar to graphene, with layers connected to each other through weak van der Waals forces between the C–N covalent bonds. Because of its exceptional optical, thermal, electrical, mechanical, and chemically inert properties, applications of g-C3N4 are typically lithium-ion batteries [20], water splitting [21], fuel cells [22], photocatalysis [23], and electrochemiluminescence and fluorescent sensor fields [24,25].

Recently, more and more attention has been focused on the application of g-C3N4 in the field of electrochemical sensors [26,27,28]. It has been reported that metal ions can be absorbed on a g-C3N4 matrix through electrostatic bonding or coordination with several N-atoms in the tri-s-triazine ring [29]. However, the poor conductivity of g-C3N4 strongly effects its use in practical applications. Therefore, the application of g-C3N4 in electrochemical sensing is still challenging. Studies show that the conductivity of the g-C3N4 can be enhanced by using some electroactive materials, such as graphene, metal oxides, and conjugated polymers [17,30,31]. These composite materials can enhance the sensitivity and selectivity of the electrodes. Among these electroactive materials, conjugated polymers (such as polyaniline, polypyrrole, polythiophene) are widely used as electroactive materials with their unique π-conjugation system, high conductivity, and fast electron properties. In recent years, the donor–acceptor–donor (D–A–D) type of conjugated polymer has been considered an ideal substance because its donor and acceptor units regularly alternate connections in each structural unit. In addition, the D–A–D type of conjugated polymer contains O, S, and N atoms, which can donate two unpaired electrons. Thus, the polymer can coordinate readily to positively charged heavy metal ions. Therefore, the composite of a D–A–D type conjugated polymers and g-C3N4 can be used as an excellent electrode modification material for the efficient detection of heavy metal ions by electrochemical sensor.

In this work, poly(2,5-bis(3,4-ethylenedioxythienyl)pyridine)/graphitic carbon nitride composites (poly(BPE)/g-C3N4) were prepared by an in situ chemical polymerization method and applied to for the simultaneous detection of Cd2+ and Pb2+. The combination of poly(BPE) and g-C3N4 not only improved the conduction pathway on the electrode surface, but also produced a strong conjugating effect on them, thus enhancing the adsorption of metal ions. The metal ions could coordinate with the lone-pair electrons of nitrogen in the tri-s-triazine unit, and the nitrogen and sulfur atoms in poly(BPE) had similar effects. Overall, using this approach for the determination of Cd2+ and Pb2+ offers several advantages including low cost, simple preparation, high selectivity, good sensitivity, and reusability. This approach might be an alternative tool for heavy metal detection in environmental monitoring.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

EDOT (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene), n-butyl lithium, 3,6-dibromopyridazide, and ferric chloride were bought from Shanghai Chemical Reagents Company (Shanghai, China). All the other chemicals and solvents, including urea, zinc chloride, sodium acetate (NaAc), acetic acid (HAc), and chloroform were used as received without further purification. The 0.1 M acetate buffer solution (ABS) was obtain through mixing different volume ratio stock solutions of 0.1 M NaAc and HAc. Standard solutions of 1 × 10−3 M of Cd2+ and Pb2+ were prepared by dissolving lead acetate and cadmium acetate in ultrapure water, respectively.

2.2. Instruments and Characterizations

The structure and properties of the composites were investigated by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), ultraviolet–visible absorption spectra (UV–vis), X-ray diffraction (XRD), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The FT-IR spectra of the composites were recorded with a BRUKER-QEUINOX-55 FTIR spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) using KBr pellets. The UV–vis spectra of the samples were recorded with a UV–vis spectrophotometer (UV4802, Unico, Dayton, NJ, USA). XRD patterns were obtained by using a Bruker AXS D8 diffractometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA), scan range (2θ), which was 10–80° with monochromatic CuKα radiation source (λ = 0.15418 nm). The SEM images were carried out on a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi, Chiyoda-ku, Japan, S-4800, operating voltage, 5 kV), with powdered samples scattered on the conducting resin. Before SEM imaging, the samples were sputtered with thin layers of aurum under vacuum. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan, model 2100) was performed with an accelerating voltage of 100 kV. The elemental percentages of samples were measured using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, which was taken on a Leo1430VP microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Oberkochen, Germany) with operating voltage 5 kV.

2.3. Preparation of g-C3N4 and Poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 Composites

2.3.1. Preparation of g-C3N4

The graphitic carbon nitride samples were prepared by a pyrolysis method using urea as precursor [32]. Typically, 10 g of urea was loaded into a 40 mL crucible with a cover. The crucible was placed in a muffle furnace under air condition and heated to 500 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min. Then, it was heated at 500 °C for 2 h and at 550 °C for another 2 h. Finally, the crucible was naturally cooled to room temperature, and a pale-yellow powder was obtained. The sample was washed with deionized water and absolute ethanol three times and dried at 60 °C for 24 h.

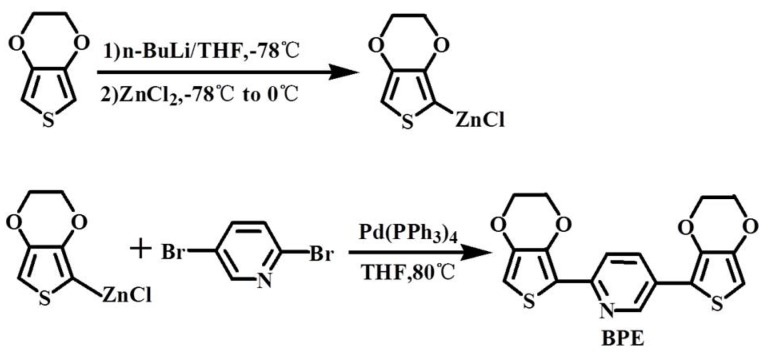

2.3.2. Preparation of Monomer BPE

The monomer of BPE was synthesized based on the previous report and reaction process as shown in Scheme 1 [33]. EDOT (5.0 g, 35.2 mmol) was added to 100 mL of anhydrous THF. Upon cooling to −78 °C, n-BuLi was added to the solution drop-wise (14.7 mL, 2.4 M) and stirred for 60 min, then ZnCl2 (4.8 g, 16.7 mmol) was added. The mixture solution was stirred at 0 °C for 60 min before Pd(PPh3)4 (1.0 g, 0.865 mmol) and 2,5-dibromopyridine (2.08 g, 8.78 mmol) in 25 mL THF was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C for another 72 h. Finally, the mixture was cooled to room temperature, and the THF was removed under reduced pressure. The product was extracted using chloroform, then further purified by recrystallization by methanol to obtain canary yellow solid. The structure of the monomer was characterized by 1H-NMR (in Figure 1). 1H-NMR: (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ [ppm] 4.30 (m, 8H), 6.33 (s, 1H), 6.43 (s, 1H), 7.91 (m, 2H), 8.91 (s, 1H).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis route for the monomer of BPE.

Figure 1.

1H-NMR spectra of bis(3,4-ethylenedioxythienyl)pyridine (BPE) in CDCl3, starred peak come from CDCl3.

2.3.3. Preparation of Poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 Composites

To prepare the poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composites, a certain weight of g-C3N4 was dispersed in 20 mL chloroform with ultrasonication for 30 min. Monomer BPE dissolved in 10 mL chloroform was added and ultrasonic dispersion applied for another 30 min. After that, FeCl3 was dispersed in 10 mL chloroform and added to the above solution drop by drop as oxidant. The reaction was stirred under magnetic stirring for 24 h. Finally, the sample was washed several times with chloroform, methanol, and distilled water, and then dried in an oven at 60 °C for 12 h.

Different weight percentages of poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite were obtained with a similar method. The pure poly(BPE) was prepared by a similar method without the addition of g-C3N4.

2.4. Preparation of Modified Electrodes

The bare glassy carbon electrode (GCE) was polished with 0.3 and 0.05 μm alumina slurries in sequence. The GCE was modified by a simple casting method. Five microliters of poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 dispersion (1 mg/mL) was spread onto the surface of the cleansed electrode and left to dry at 40 °C. The different weight percentages of poly(BPE)/g-C3N4, pure poly(BPE), and g-C3N4-modified GCE were prepared using the same procedure.

2.5. Electrochemical Measurements

All electrochemical measurements were carried out on CHI660C electrochemical workstation (ChenHua Instruments Co., Shanghai, China). In the three-electrode system, composite-modified electrode, platinum electrode, and saturated calomel electrode were used, respectively, as the working electrode, counter electrode, and reference electrode. Cyclic voltammograms (CV) were carried out in a mixing solution of 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− with 0.1 M KCl with a scanning rate of 50 mV·s−1. Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) was performed in 0.1 M ABS (pH = 4.5) with potential interval −1.4 to −0.2 V; deposition potential, −1.4 V; deposition time, 210 s; pulse width, 50 ms; pulse period, 100 ms; increment potential, 2 mV.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structure Characterization of Poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 Composites

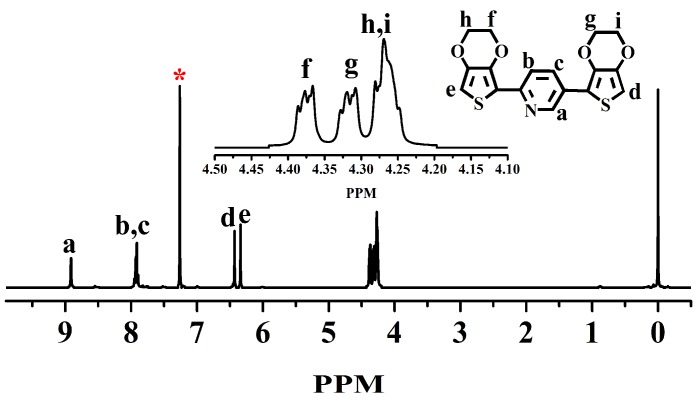

Figure 2A represents the FT-IR spectra of g-C3N4, poly(BPE), and poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composites. In the spectra of g-C3N4, the band at 812 cm−1 is attributed to the bending vibration of the triazine ring modes out of plane. The weak peak at 890 cm−1 is assigned to the cross-linked heptazine deformation mode [34]. The fingerprint regions at the range of 1230–1650 cm−1 correspond to the stretching vibrations of C–N and C=N in heterocycles [35]. A broad vibration band appears in the region of 3000–3500 cm−1, which can be assigned to the stretching vibrations of aromatic N–H bonds of the uncondensed amino group (–NH2) [36]. For the pure poly(BPE), the band at 2800–3100 cm−1 corresponds to the aromatic C–H stretching vibrations. The peaks at 1439, 1358, and 1300 cm−1 are due to the C=C asymmetric stretching vibration and C–C stretching vibration in the poly(BPE) ring. The bands at 1663 cm−1 and 1658 cm−1 are C=N stretching in the pyridine. There are only a few discrepancies between the spectra of g-C3N4 and poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite, and it is probably because the peaks of g-C3N4 and poly(BPE) at 1230–1650 cm−1 have been superimposed. The new weak band at 1081 cm−1 was observed after incorporating the polymer into the composite. This band is assigned to the presence of ν(C–O–C) in the ethylenedioxy group of EDOT, due to the strong interaction between poly(BPE) and g-C3N4 [37,38,39].

Figure 2.

(A) FT-IR spectra; (B) UV–vis spectra; (C) XRD patterns; and (D) EDS of g-C3N4, using different weight percentages of poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composites and poly(BPE).

Figure 2B represents the UV–vis spectra of g-C3N4, poly(BPE), and poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composites. The UV–vis spectra of g-C3N4 shows characteristic absorption peaks from 270 to 430 nm, which are characteristic peaks of the carbon nitride. Furthermore, the absorption peaks of poly(BPE) appear at 348, 490, and 586 nm, which are assigned to the π–π* transition of the thiophene ring [39]. In the case of poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composites, aside from the characteristic peak of g-C3N4, the absorption peak appears at 490 nm for 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 and 15 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4. The results suggested that poly(BPE) was successfully incorporated into the g-C3N4 matrix.

Figure 2C exhibits the XRD patterns of poly(BPE), g-C3N4, and poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composites. The poly(BPE) shows broad characteristic peaks at about 2θ = 22.5°, which is assigned to the π–π* stacking within the molecule. Moreover, the sharp diffraction peaks at 2θ ≈ 33°, 35°, 41°, 49°, and 54° are associated with the FeCl4– doping agent [38,39]. Diffraction peaks of g-C3N4 are located at 27.1° and 13.2°, which can be indexed as (002) and (100) diffraction planes for graphitic materials (JCPDS 87-1526). The strongest diffraction peak of graphite appears at 2θ = 27.1°, which is attributed to the planes of graphitic structures. The minor peak at 13° corresponds to the hole-to-hole arrays of tri-s-triazine units. For the composites, no other peaks appeared, indicating the crystal structure was not changed. However, it can be seen that as the intensity of (100) planes of g-C3N4 decreases, the amount of poly (BPE) increases, suggesting that the original ordered intralayer structures of g-C3N4 probably suffered from damage in the presence of poly(BPE) [40,41].

Figure 2D depicts the EDS of g-C3N4 and poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composites and poly(BPE). As shown in Figure 2D, the EDS spectrum of the pure g-C3N4 samples reveal the existence of C and N elements [42]. In the spectrum of pure poly(BPE), the C, N, O, and S elements are the major chemical elements, and a small amount of Fe element was detected due to the addition of ferric chloride [38]. For the poly(BPE)/g-C3N4, except the C and N elements, the O and S elements were also detected, which provided powerful evidence for the existence of poly(BPE). In addition, as the percentage of poly(BPE) increases, the weight percentage of S element in the composite increases from 0.21% to 1.14%.

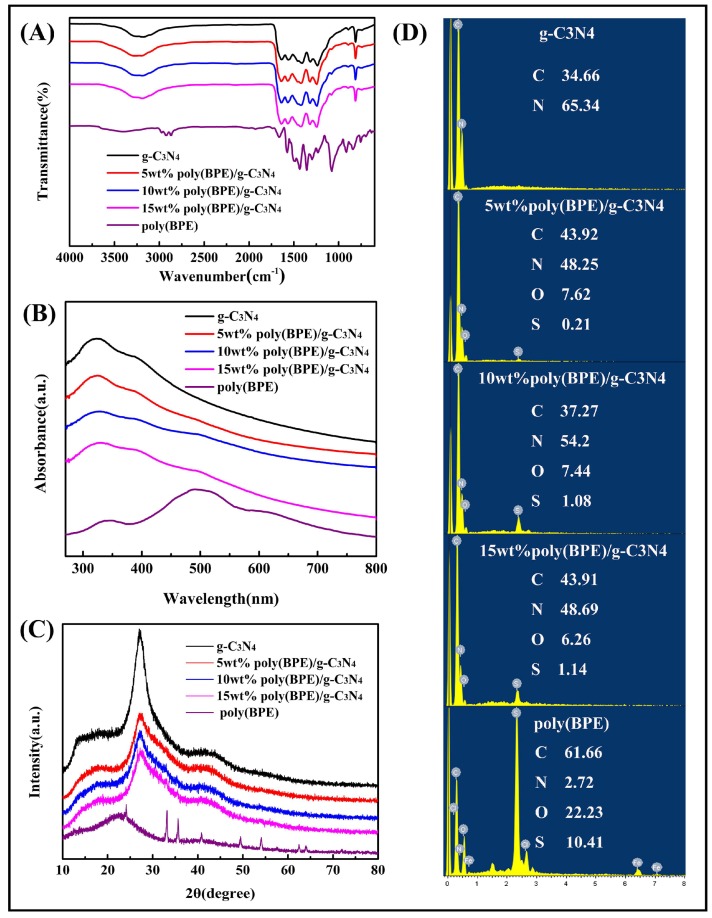

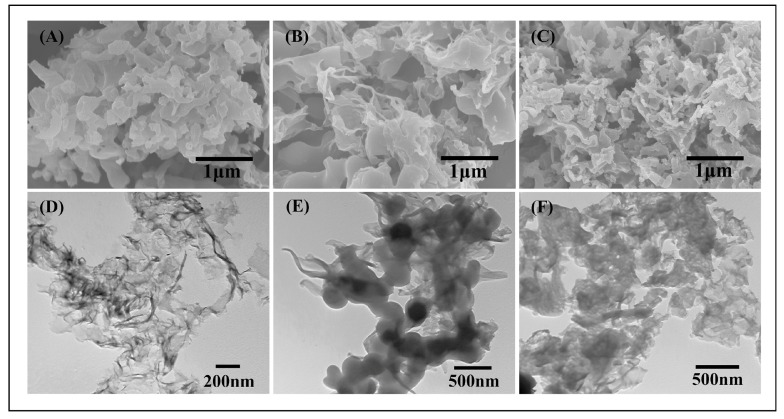

Figure 3 presents the SEM and TEM images of g-C3N4, poly(BPE), and 10 wt % poly(BEP)/g-C3N4 composite. As shown in Figure 3A,D, the sheet-like g-C3N4 was like the fold of the sheet structure and appears as ultrathin and well-spread sheets. As shown in Figure 3B,E, the pure poly(BPE) exhibits uneven thickness of the irregular lump material. As shown in Figure 3C,F, slightly less poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 (at 10 wt %) grows on the surface of g-C3N4 compared to pure g-C3N4 and poly(BPE), forming a net-like structure. Due to the richness of amino, g-C3N4 can be easily dispersion by the method of ultrasonication. The BPE monomer can be adsorbed on the surface of sheet-like g-C3N4 by the π–π aromatic interaction and electrostatic attraction. During the in situ chemical polymerization from the effect of ferric chloride, the monomer adsorbed on the surface of g-C3N4 grew on g-C3N4 to form poly(BPE) [43].

Figure 3.

SEM images of (A) g-C3N4; (B) poly(BPE); (C) 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite; and TEM images of (D) g-C3N4; (E) poly(BPE); and (F) 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite.

3.2. Electrochemical Characterization of Poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 Composites

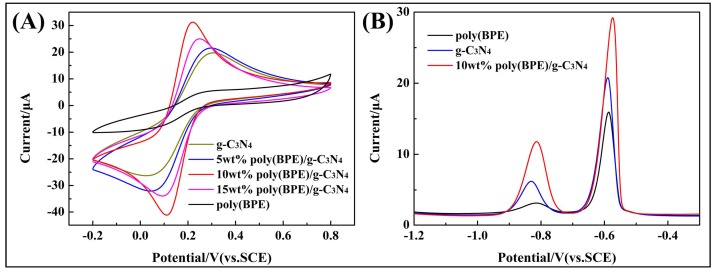

The electrochemical activity of differently modified GCEs was evaluated using CV in a redox probe solution containing 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− in 0.1 M KCl. As shown in Figure 4A, all the modified electrodes show well-defined redox peaks, which are related to the [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− redox processes. Compared to poly(BEP) and g-C3N4-modified GCE, the redox peak of the poly(BEP)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE is obviously enhanced. This indicates that more electrochemically active sites were present on the surface of poly(BEP)/g-C3N4. Also, it is probably due to the excellent electron transfer property of poly(BEP) [44]. The peak-to-peak potential (∆Ep = Eanodicpeak − Ecathodicpeak) at 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE is about 110 mV, while those at the g-C3N4, 5 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4, and 15 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE are 280, 247, and 155 mV, respectively (detailed data in Table 1). Meanwhile, the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE presents the largest background current and peak current compared to other modified GCEs, indicating that more electrochemical active sites present on the surface of 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE [45]. Under the Randles–Sevcik equation, Ip = 2.69 × 105 n3/2 ACD01/2 ν1/2, where Ip is the anodic peak current, n is the number of electrons transferred, A is electroactive surface area, C is concentration, ν is the potential scanning rate, and D0 is the diffusion coefficient [44,46,47]. The effective surface areas of the g-C3N4, 5 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4, 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 and 15 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE are estimated to be 0.0781 cm2, 0.0851 cm2, 0.1234 cm2, and 0.0989 cm2, respectively. The 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 has the largest effective surface area. Therefore, the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE could be used as an excellent sensor for electroactive species.

Figure 4.

(A) Cyclic voltammograms measured with g-C3N4, poly(BPE), poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified glassy carbon electrode (GCE) in a solution of 5 mM Fe(CN)63−/4− containing 0.1 M KCl. (B) Differential pulse voltammogram (DPV) of g-C3N4, poly(BPE), 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE in 0.1 M acetate buffer solution (ABS) (pH = 4.5) containing 2 μM of Cd2+ and Pb2+. Deposition potential: −1.4 V, deposition time: 210 s, pulse width: 50 ms; pulse period: 100 ms; increment potential: 2 mV.

Table 1.

The peak-to-peak potential (ΔEp) of differently modified GCEs.

| Modified GCE | Eanodicpeak (mV) | Ecathodicpeak (mV) | ∆Ep (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| g-C3N4 | 305 | 225 | 280 |

| 5 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 | 295 | 48 | 247 |

| 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 | 220 | 110 | 110 |

| 15 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 | 249 | 94 | 155 |

Figure 4B shows the DPV of the differently modified GCEs in 0.1 M ABS (pH = 4.5) containing 2.0 μM Cd2+ and Pb2+. As shown, the distance between the individual peaks is large enough, with individual peaks at approximately −0.834 V and −0.586 V for Cd2+ and Pb2+, respectively. The peak current of GCE modified by 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite increased significantly, the main reason being that poly(BPE) not only effectively improves the electron transfer rate of the electrode surface, but also strongly interacts with the conjugated structure of g-C3N4 by π–π stacking, which results from electrode materials having strong adsorption capacity [48].

3.3. Optimization of Experimental Conditions

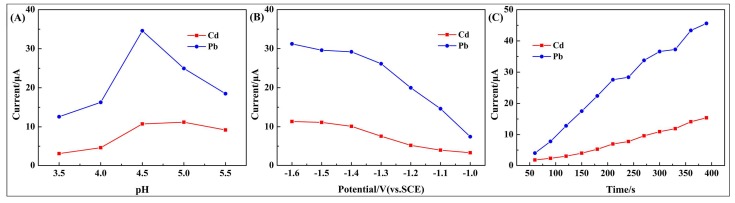

To optimize the experimental conditions, simultaneous determination of 2.0 μM Cd2+ and Pb2+ at the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE under different pH values were evaluated (deposition potential: −1.4 V, deposition time: 210 s, pulse width: 50 ms; pulse period: 100 ms, increment potential: 2 mV). As shown in Figure 5A, maximum current responses appeared at pH = 4.5. The lower pH values (3.5 and 4.0) could results in a reduction peak current, which is possibly due to the protonation of the hydrophilic groups reducing the absorption of metal ions. The peak current at the higher pH values (5.0 and 5.5) decreased, which is possibly due to the hydrolysis of Cd2+ and Pb2+. Thus, pH = 4.5 was chosen as the best condition for the electrochemical measurements.

Figure 5.

The effects of (A) pH values; (B) deposition potential; and (C) deposition time on the stripping peak currents of Cd2+ and Pb2+ at 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE in 0.1 M ABS containing 1 μM of Cd2+ and Pb2+.

The effect of the deposition potential on the performance of the modified electrode was investigated in the range from −1.0 to −1.6 V, and the results are shown in Figure 5B. The maximum current peak could be observed at −1.4 V. However, the peak currents decreased gradually with the potential moving to the negative direction. Thus, the deposition potential of −1.4 V was chosen as the optimum value for detection of two heavy metals.

Figure 5C exhibits the DPV current response of 2.0 μM Cd2+ and Pb2+ over the accumulation time of 60–390 s. As shown in Figure 5C, for the time of 60–210 s, the peak currents are almost linearly proportional to accumulation time, and this may be attributed to the fact that the amount of metal ions at the modified electrode surface greatly increases due to electrochemical deposition. When deposition time was above 210 s, the increase rate of the peak current of Pb2+ changed, and this is probably due to the working electrode surface saturation. Under the consideration of sensitivity, a determination time of 210 s was selected for the deposition of the ions.

3.4. Individual Determination of Cd2+ and Pb2+

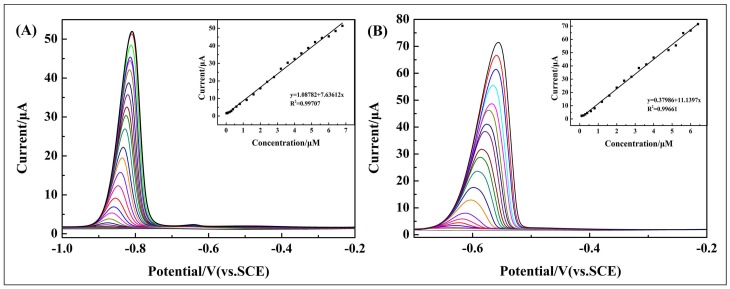

Under the optimized conditions, DPV was used as an analytical method for the electrochemical detection of Cd2+ and Pb2+ using various modified GCEs in 0.1 M ABS (pH = 4.5). Figure 6 exhibits the DPV responses of 10 wt % poly(BEP)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE toward Cd2+ and Pb2+. The figure also shows the linear relationship between peak currents and concentrations of the two ions, and the inset shows as well as their linear equations and correlation coefficient (Figure 6 inset). The linear range of Cd2+ is 0.1–6.8 μM with a detection limit of 0.0097 μM. The linear range of Pb2+ is 0.1–6.4 μM with a detection limit of 0.00327 μM. Detailed results are shown in Table 2.

Figure 6.

DPV response of the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE for the individual analysis of (A) Cd2+ over a concentration range of 0.1–6.8 μM; (B) Pb2+ over a concentration range of 0.1–6.4 μM. The inset shows their linear equations as well as correlation coefficient.

Table 2.

Performance of the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE for individual and simultaneous determination of Cd2+ and Pb2+.

| Types | Analytes | Linear Range (μM) | Linear Regression Equation | R2 | Detection Limit (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual determination | Cd2+ | 0.1–6.8 | I (μA) = 1.08782 + 7.63612c (μM) | 0.99707 | 0.00970 |

| Pb2+ | 0.1–6.4 | I (μA) = 0.37986 + 11.1397c (μM) | 0.99661 | 0.00327 | |

| Simultaneous determination | Cd2+ | 0.12–7.2 | I (μA) = 0.26776 + 4.11513c (μM) | 0.99740 | 0.0180 |

| Pb2+ | 0.08–7.2 | I (μA) = 0.73646 + 11.28023c (μM) | 0.99599 | 0.00324 |

From the above results, it is clear that the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified electrode showed a wide detection range and low detection limit, and the detection limits were lower than the those of WHO standards. It should be noticed that the electrochemical analysis of 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite for trace metal ions may be attributed to the lone-pair electrons of nitrogen in the g-C3N4. The report shows that the highly ordered tri-s-triazine units contain many ideal coordination sites and thus metal ions can intercalate into g-C3N4 through the lone-pair electrons of nitrogen [26,27,28,29]. The combination of poly(BPE) and g-C3N4 not only improved the conduction pathway on the electrode surface, but also produced a strong conjugate effect on them, enhancing the adsorption of metal ions.

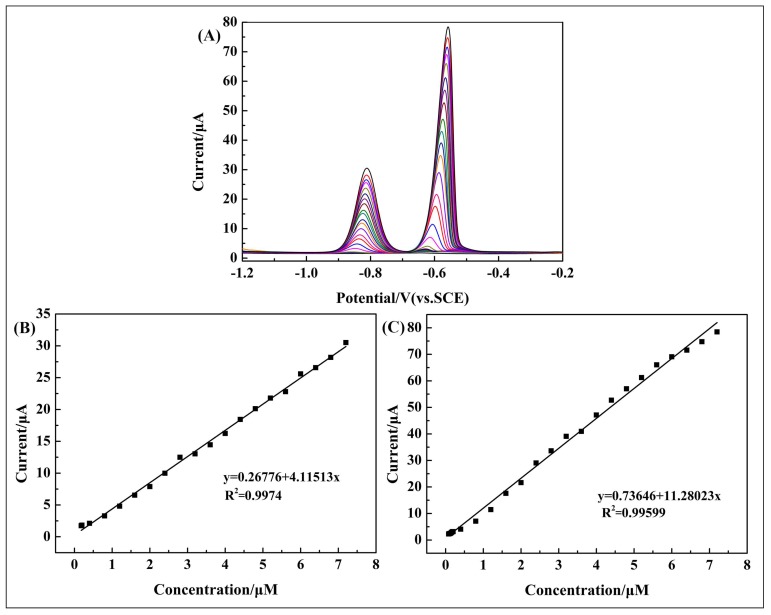

3.5. Simultaneous Determination of Cd2+ and Pb2+

The analytical performance of the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE was investigated by simultaneous determination of Cd2+ and Pb2+ in 0.1 M ABS (pH = 4.5). As shown in Figure 7A, the current response of Cd2+ and Pb2+ appeared at −0.82 V and −0.58 V, respectively. The distance between each individual peak is large enough to simultaneous detect these heavy metal ions using the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE. Figure 7B,C shows the linear relationship between peak current and concentration of the two heavy metal ions, as well as their linear equations and the correlation coefficient. The linear ranges of Cd2+ and Pb2+ are 0.12–7.2 μM and 0.08–7.2 μM, respectively. The detection limits of Cd2+ and Pb2+ are 0.018 μM and 0.00324 μM, respectively. Other detailed results are shown in Table 1.

Figure 7.

(A) DPV response of the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE for the simultaneous analysis of Cd2+ and Pb2+ over a concentration range of 0.1–7.2 μM; (B,C) the respective calibration curves of Cd2+ and Pb2+ corresponding to (A).

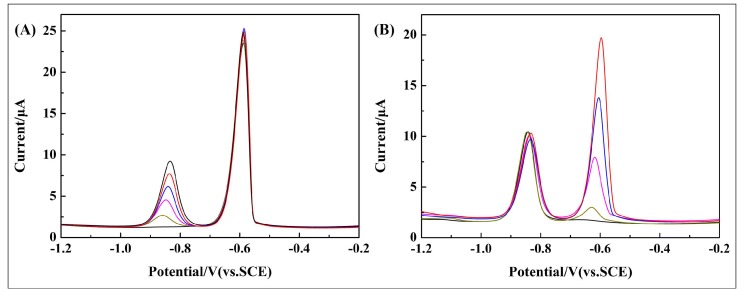

In the DPV technique, interfering molecules in the sample solution may be co-deposited on the active sites of the electrode surface, which result in changes in the stripping peak current. The interference may be the result of two main factors: (i) intermetallic compound formation and (ii) the competition between analytes and interferent ions for active sites on the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE surface. In order to understand whether there is interference between Cd2+ and Pb2+ in simultaneous detection, we performed the following experiment. The effect of a single species on the multispecies was performed by changing one species’ concentration while the other species was unchanged. As shown in Figure 8, the DPV response of Cd2+ and Pb2+ increased linearly with the increase of the target ion’s concentration, while the other ion was kept at a constant concentration of 2 μM. From Figure 8A, it can be seen that the peak current of Pb2+ is practically unaltered with increasing of Cd2+ concentration, and the peak current of Cd2+ is practically unaltered with the increasing of Pb2+ concentration (Figure 8B). These results indicate that the other coexisting ion did not interfere with the determination of Cd2+ or Pb2+. In addition, comparisons of the differently modified electrodes toward the simultaneous detection of Cd2+ and Pb2+ are shown in Table 3. From Table 3, it can be deduced that the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE could be an ideal sensor for simultaneous detection of Cd2+ and Pb2+.

Figure 8.

(A) DPV response of the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE at 0, 0.4, 0.8, 1.2, 1.6, and 2 μM Cd2+ in the presence of 2.0 μM Pb2+ in 0.1 M NaAc–HAc (pH = 4.5), showing the effect of the concentration of Cd2+ on the peak currents of 2.0 μM Pb2+. (B) DPV response of the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE at 0, 0.4, 0.8, 1.2, 1.6, and 2 μM Pb2+ in the presence of 2.0 μM Cd2+ in 0.1 M NaAc–HAc (pH = 4.5), showing the effect of the concentration of Pb2+ on the peak current of 2.0 μM Cd2+.

Table 3.

Comparison of different sensors for the determination of heavy metals.

| Electrode | Methods | Analytes | Linear Range (μM) | LOD (μM) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA/PPy/GO | DPV | Cd2+ | 0.045–1.335 | 0.019 | [43] |

| Pb2+ | 0.024–0.724 | 0.002 | |||

| l-cys/GR-CS/GCE | DPASV | Cd2+ | 0.005–0.6 | 0.0012 | [4] |

| Pb2+ | 0.005–0.3 | 0.0072 | |||

| GO/ex-Bi2Te3 modified GCEs | SWV | Cd2+ | 0.009–0.178 | 0.0018 | [49] |

| Pb2+ | 0.0024–0.0965 | 0.00048 | |||

| G/PANI/PS fiber/SPCE | SWASV | Cd2+ | 0.089–4.448 | 0.039 | [50] |

| Pb2+ | 0.048–2.413 | 0.016 | |||

| AuNPs/CNFs | SWASV | Cd2+ | 0.1–1.0 | 0.1 | [51] |

| Pb2+ | 0.1–1.0 | 0.1 | |||

| DCD-CPE | DPSV | Cd2+ | 0.25–25 | 0.04 | [52] |

| Pb2+ | 0.1–15 | 0.01 | |||

| Nafion-HAP | DPASV | Cd2+ | 0.1–10.0 | 0.035 | [53] |

| Pb2+ | 0.1–10.0 | 0.049 | |||

| BT-SBA-15/CPE | DPASV | Cd2+ | 2.0–10.0 | 0.4 | [54] |

| Pb2+ | 0.3–7.0 | 0.04 | |||

| Poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 | DPV | Cd2+ | 0.12–7.2 | 0.018 | This work |

| Pb2+ | 0.08–7.2 | 0.00324 |

PA/PPy/GO: phytic acid-functionalized polypyrrole/graphene oxide-modified electrode; l-cys/GR-CS/GCE: l-cysteine/graphene–chitosan-modified GCE; GO/ex-Bi2Te3-modified GCE: GO/exfoliated Bi2Te3-modified GCE; G/PANI/PS nanoporous fiber/SPCE: graphene/polyaniline/polystyrene nanoporous fiber-modified screen-printed carbon electrode; AuNPs/CNFs: a well-dispersed Au nanoparticle grown on carbon nanofibers; BT-SBA-15/CPE: 2-benzothiazolethiol functionalized SBA-15; DCD-CPE: diacetyldioxime-modified carbon paste electrode; HAP-Nafion: the nanocomposite of HAP and Nafion.

3.6. Interference Study

It is known that, in practical applications, interference ions might co-deposit on an electrode with Cd2+ and Pb2+. The interference study was performed by adding various potentially interfering metal cations including Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Al3+, Fe3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ in 50-fold excess with target metal ions into a standard solution containing 2 μM Cd2+ and Pb2+ under the optimized working conditions. As listed in Table 4, the change in the peak current of Cd2+ and Pb2+ was less than 10% after adding interfering ions. Thus, the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE displayed high selectivity for Cd2+ and Pb2+ in the heavy metal analysis.

Table 4.

Interferences of some metal ions (100 μM) on the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE during simultaneous determination of 2 μM Cd2+ and Pb2+. Electrolyte: 0.1 M ABS (pH = 4.5); deposition potential: −1.4 V; deposition time: 210 s.

| Interferences | Contribution (%) (Ip Cd2+ = 100%) |

Contribution (%) (Ip Pb2+ = 100%) |

|---|---|---|

| Na | +3.15% | +9.46% |

| K | −8.77% | +2.85% |

| Ca | −8.81% | +3.92% |

| Mg | +6.11% | −2.64% |

| Al | −8.36% | 1.31% |

| Fe | 5.32% | 0.5% |

| Co | −0.75% | −0.7% |

| Ni | 4.94% | 8.8% |

| Cu | −13.86% | −5.38% |

| Zn | −4.19% | 5.9% |

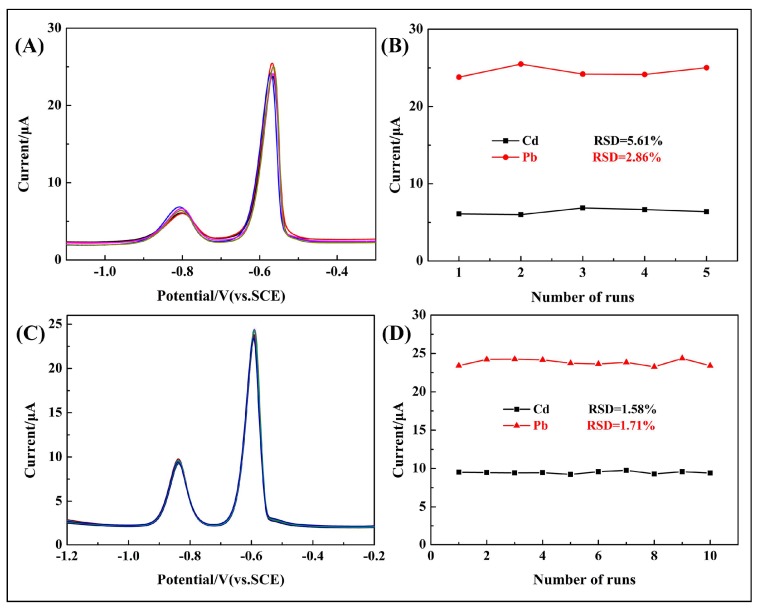

3.7. Reproducibility of Modified Electrode

To further evaluate the sensing performance, the repeatability of the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE was tested with 2 μM Cd2+ and Pb2+ under the optimized conditions. Electrolyte: 0.1 M ABS (pH = 4.5), deposition potential: −1.4 V, deposition time: 210 s. As shown in Figure 9, the reproducibility was estimated with five different 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCEs that were prepared independently by the same procedure. The values of relative standard deviation (RSD) were 5.61% for Cd2+ and 2.86% for Pb2+ in the presence of 2 μM of metal ions, which demonstrated the reliability of the fabrication procedure. Repeatability of the developed method was evaluated by detecting 2 μM Cd2+ and Pb2+ at the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE for 10 measurements. The values of RSD were 1.58% for Cd2+ and 1.71% for Pb2+. Hence, the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE shows ideal reproducibility and repeatability.

Figure 9.

(A) DPV response of 2.0 μM Cd2+ and Pb2+ on five 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCEs in 0.1 M ABS (pH = 4.5). (B) The data collected from every DPV response for a total of 10 times. RSD refers to the relative standard deviation. (C) DPV response of 2.0 μM Cd2+ and Pb2+ on the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE in 0.1 M ABS (pH = 4.5). (D) The data collected from every DPV response for a total of 10 times, RSD refers to the relative standard deviation.

3.8. Real Sample Analysis

The 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE for simultaneous determination of Cd2+ and Pb2+ showed high sensitivity and better reproducibility. Tap water samples were taken to carry out a further study. Firstly, certain amounts of tap water in 0.1 M ABS (pH = 4.5) were prepared. Subsequently, standard solutions of Cd2+ and Pb2+ with different concentration were added to the tap water samples. The results are illustrated in Table 5. The recoveries of the Cd2+ and Pb2+ are 98.64–106.74% and 99.81–113.15%, respectively. Results indicate that the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified GCE could be applied in the detection of Cd2+ and Pb2+ in tap water samples.

Table 5.

Determination of Cd2+ and Pb2+ in tap water.

| Original | Added (μM) | Found (μM) | Recovery (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (μM) | Cd2+ | Pb2+ | Cd2+ | Pb2+ | Cd2+ | Pb2+ |

| N.D | 1 | 1 | 1.0396 | 1.1315 | 103.96 | 113.15 |

| N.D | 2 | 2 | 2.1347 | 2.0334 | 106.74 | 101.67 |

| N.D | 3 | 3 | 3.0925 | 2.9944 | 103.08 | 99.81 |

| N.D | 4 | 4 | 3.9455 | 4.0102 | 98.64 | 100.26 |

N.D: not detected.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a novel poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite has been successfully synthesized via chemical oxidative polymerization and used for determination of Cd2+ and Pb2+. The highly ordered tri-s-triazine units contain many ideal coordination sites, and thus metal ions can intercalate into g-C3N4 through the lone-pair electrons of nitrogen. Besides that, the composite-modified electrode possesses a wide detection range and excellent sensitivity towards the simultaneous detection of Cd2+ and Pb2+.The results demonstrate that the 10 wt % poly(BPE)/g-C3N4 composite-modified electrode possesses high sensitively, wide linear range, and low detection limit for the determination of Cd2+ and Pb2+.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21764014, No. 21564014).

Author Contributions

Shuai Ding, Ahmat Ali and Ruxangul Jamal conceived and designed the experiments; Shuai Ding performed the experiments; Ling Xiang and Ziping Zhong analyzed the data; Tursun Abdiryim contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; Shuai Ding and Tursun Abdiryim wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Shahbazi Y., Ahmadi F., Fakhari F. Voltammetric determination of Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu and Se in milk and dairy products collected from Iran: An emphasis on permissible limits and risk assessment of exposure to heavy metals. Food Chem. 2016;192:1060–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan I., Pandit U.J., Wankar S., Limaye S.N. Centrifugation assisted digestion for simultaneous voltammetric determination of ultra trace metal ions in water and milk samples. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2017;7:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.enmm.2017.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahesar S.A., Sherazi S.T., Niaz A., Bhanger M.I., Uddin S., Rauf A. Simultaneous assessment of Zinc, Cadmium, Lead and Copper in poultry feeds by differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetry. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010;48:2357–2360. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo Z., Li D.D., Luo X.K., Li Y.H., Zhao Q.N., Li M.M., Zhao Y.T., Sun T.S., Ma C. Simultaneous determination of trace Cd(II), Pb(II) and Cu(II) by differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetry using a reduced graphene oxide-chitosan/poly-l-lysine nanocomposite modified glassy carbon electrode. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;490:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu Y., Liang X., Niyungeko C., Zhou J., Tian G. A review of the identification and detection of heavy metal ions in the environment by voltammetry. Talanta. 2017;178:324–338. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koelmel J., Amarasiriwardena D. Imaging of metal bioaccumulation in hay-scented fern (Dennstaedtia punctilobula) rhizomes growing on contaminated soils by laser ablation ICP-MS. Environ. Pollut. 2012;168:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massadeh A.M., Alomary A.A., Mir S., Momani F.A., Haddad H.I., Hadad Y.A. Analysis of Zn, Cd, As, Cu, Pb, and Fe in snails as bioindicators and soil samples near traffic road by ICP-OES. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. 2016;23:13424–13431. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6499-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sánchezrodas D., Corns W.T., Chen B., Stockwell P.B. Atomic Fluorescence Spectrometry: A suitable detection technique in speciation studies for arsenic, selenium, antimony and mercury. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2010;25:933–946. doi: 10.1039/b917755h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siraj K., Kitte S.A. Analysis of Copper, Zinc and Lead using Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer in ground water of Jimma town of Southwestern Ethiopia. Int. J. Chem. Anal. Sci. 2013;4:201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcas.2013.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grasso G., D’Urso L., Messina E., Cataldo F. A mass spectrometry and surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy study of the interaction between linear carbon chains and noble metals. Carbon. 2009;47:2611–2619. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2009.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caschera D., Federici F., Zane D., Focanti F., Curulli A., Padeletti G. Gold nanoparticles modified GC electrodes: Electrochemical behaviour dependence of different neurotransmitters and molecules of biological interest on the particles size and shape. J. Nanopart. Res. 2008;11:1925–1936. doi: 10.1007/s11051-008-9547-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei Y., Yang R., Yu X.Y., Wang L., Liu J.H., Huang X.J. Stripping voltammetry study of ultra-trace toxic metal ions on highly selectively adsorptive porous magnesium oxide nanoflowers. Analyst. 2012;137:2183–2191. doi: 10.1039/c2an15939b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao D., Guo X., Wang T., Alvarez N., Shanov V.N., Heineman W.R. Simultaneous Detection of Heavy Metals by Anodic Stripping Voltammetry Using Carbon Nanotube Thread. Electroanalysis. 2014;26:488–496. doi: 10.1002/elan.201300511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gadgil B., Damlin P., Dmitrieva E., Ääritalo T., Kvarnström C. Exploring amide linkage in a polyviologen derivative towards simultaneous voltammetric determination of Pb(II), Cu(II) and Hg(II) ions. Electrochim. Acta. 2016;192:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie Y.L., Zhao S.Q., Ye H.L., Yuan J., Song P., Hu S.Q. Graphene/CeO2 hybrid materials for the simultaneous electrochemical detection of Cadmium(II), Lead(II), Copper(II), and Mercury(II) J. Electroanal. Chem. 2015;757:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2015.09.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruecha N., Rodthongkum N., Cate D.M., Volckens J., Chailapakul O., Henry C.S. Sensitive electrochemical sensor using a graphene–polyaniline nanocomposite for simultaneous detection of Zn(II), Cd(II), and Pb(II) Anal. Chim. Acta. 2015;874:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun C., Zhang M., Fei Q., Wang D., Sun Z., Geng Z., Xu W., Liu F. Graphite-like g-C3N4-F127-Au Nanosheets Used for Sensitive Monitoring of Heat Shock Protein 90. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017;256:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2017.10.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng Y., Zhang Z., Li C. A comparison of graphitic carbon nitrides synthesized from different precursors through pyrolysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 2017;332:32–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2016.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu L., Xia J., Wang L., Ji H., Qian J., Xu H., Wang K., Li H. Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanorods for Photoelectrochemical Sensing of Trace Copper(II) Ions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014;2014:3665–3673. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201402051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu M., Wang Q., Sun Q., Jena P. Functionalized Graphitic Carbon Nitride for Efficient Energy Storage. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013;117:6055–6059. doi: 10.1021/jp311972f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X., Maeda K., Thomas A., Takanabe K., Xin G., Carlsson J.M., Domen K., Antonietti M. A metal-free polymeric photocatalyst for hydrogen production from water under visible light. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:76–80. doi: 10.1038/nmat2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Q., Zhang J. Graphene Supported Co-g-C3N4 as a Novel Metal–Macrocyclic Electrocatalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Fuel Cells. Langmuir. 2013;29:3821–3828. doi: 10.1021/la400003h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shalom M., Inal S., Fettkenhauer C., Neher D., Antonietti M. Improving carbon nitride photocatalysis by supramolecular preorganization of monomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:7118–7121. doi: 10.1021/ja402521s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Q.M., Shen Y.Z., Li M.X., Zhang Z.L., Zhao W., Xu J.J., Chen H.Y. Dual-Wavelength Electrochemiluminescence Ratiometry Based on Resonance Energy Transfer between Au Nanoparticles Functionalized g-C3N4 Nanosheet and Ru(bpy)32+ for microRNA Detection. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:937–944. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tian J., Liu Q., Asiri A.M., Alyoubi A.O., Sun X. Ultrathin graphitic carbon nitride nanosheet: A highly efficient fluorosensor for rapid, ultrasensitive detection of Cu2+ Anal. Chem. 2013;85:5595–5599. doi: 10.1021/ac400924j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao W., Wang X., Li P., Wu Q., Wu S., Yu Y., Ding K. Highly sensitive and selective detection of cadmium with a graphite carbon nitride nanosheets/Nafion electrode. RSC Adv. 2016;6:113570–113575. doi: 10.1039/C6RA24638A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang D.P., Tang Y., Zhang W.D. A carbon nitride electrode for highly selective and sensitive determination of lead(II) Microchim. Acta. 2013;180:1303–1308. doi: 10.1007/s00604-013-1051-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amiri M., Salehniya H., Habibiyangjeh A. Graphitic Carbon Nitride/Chitosan Composite for Adsorption and Electrochemical Determination of Mercury in Real Samples. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016;55:8114–8122. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.6b01699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu X., Yang Y., Liu T. Synthesis, Al/Mg Intercalation and Structure Study of Graphite-like Carbon Nitride. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2011;27:245–251. doi: 10.1016/S1005-0302(11)60057-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun Y., Jiang J., Liu Y., Wu S., Zou J. A facile one-pot preparation of Co3O4/g-C3N4 heterojunctions with excellent electrocatalytic activity for the detection of environmental phenolic hormones. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;430:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.06.157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang H., Huang Q., Huang Y., Li F., Zhang W., Wei C., Chen J., Dai P., Huang L., Huang Z. Graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets doped graphene oxide for electrochemical simultaneous determination of ascorbic acid, dopamine and uric acid. Electrochim. Acta. 2014;142:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2014.07.094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chidhambaram N., Ravichandran K. Single step transformation of urea into metal-free g-C3N4 nanoflakes for visible light photocatalytic applications. Mater. Lett. 2017;207:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2017.07.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubois C.J., Reynolds J.R. 3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene–Pyridine-Based Polymers: Redox or n-Type Electronic Conductivity? Adv. Mater. 2010;14:1844–1846. doi: 10.1002/adma.200290016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boydis M.J., Müller J.O., Antonietti M., Arne T. Ionothermal synthesis of crystalline, condensed, graphitic carbon nitride. Chemistry. 2008;14:8177–8182. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martha S., Nashim A., Parida K.M. Facile synthesis of highly active g-C3N4 for efficient hydrogen production under visible light. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2013;1:7816–7824. doi: 10.1039/c3ta10851a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou X., Jin B., Li L., Peng F., Wang H., Yu H., Fang Y. A carbon nitride/TiO2 nanotube array heterojunction visible-light photocatalyst: Synthesis, characterization, and photoelectrochemical properties. J. Mater. Chem. 2012;22:17900–17905. doi: 10.1039/c2jm32686h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu F., Jamal R., Wang Y., Wang M., Yang L., Abdiryim T. Photodegradation of methylene blue by photocatalyst of D-A-D type polymer/functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes composite under visible-light irradiation. Chemosphere. 2016;168:1669–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.11.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y., Jamal R., Wang M., Yang L., Liu F., Abdiryim T. A donor–acceptor–donor-type conjugated polymer-modified TiO2 with enhanced photocatalytic activity under simulated sunlight and natural sunlight. J. Mater. Sci. 2017;52:4820–4832. doi: 10.1007/s10853-016-0717-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang L., Jamal R., Liu F., Wang Y., Abdiryim T. Structure and photocatalytic activity of a low band gap donor–acceptor–donor (D–A–D) type conjugated polymer: Poly(EDOT–pyridazine–EDOT) RSC Adv. 2017;7:1877–1886. doi: 10.1039/C6RA25252D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu J., Chen Y., Ma D., Shang J.K., Li Y.X. Simple preparation of MgO/g-C3N4 catalyst and its application for catalytic synthesis of dimethyl carbonate via transesterification. Catal. Commun. 2017;95:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.catcom.2017.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong Q., Chen Y., Wang L., Ai S., Ding H., Dong Q., Chen Y., Wang L., Ai S., Ding H. Cu-modified alkalinized g-C3N4 as photocatalytically assisted heterogeneous Fenton-like catalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;426:1133–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.07.254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang L., Ma C., Guo Z., Lv Y., Chen W., Chang Z., Yuan Q., Ming H., Wang J. In-situ growth of g-C3N4 layer on ZnO nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic performances under visible light irradiation. Mater. Lett. 2017;188:347–350. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2016.11.113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dai H., Wang N., Wang D., Ma H., Lin M. An electrochemical sensor based on phytic acid functionalized polypyrrole/graphene oxide nanocomposites for simultaneous determination of Cd(II) and Pb(II) Chem. Eng. J. 2016;299:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2016.04.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang C., Du J., Wang H., Zou C.E., Jiang F., Yang P., Du Y. A facile electrochemical sensor based on reduced graphene oxide and Au nanoplates modified glassy carbon electrode for simultaneous detection of ascorbic acid, dopamine and uric acid. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014;204:302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.07.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ali A., Jamal R., Abdiryim T., Huang X. Synthesis of monodispersed PEDOT/Au hollow nanospheres and its application for electrochemical determination of dopamine and uric acid. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017;787:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2017.01.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu F., Fan W., Yang D., Yong G., Li H. Electrochemical sensing platform for L-CySH based on nearly uniform Au nanoparticles decorated graphene nanosheets. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2014;38:292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang L., Yamauchi Y. Facile Synthesis of Three-Dimensional Dendritic Platinum Nanoelectrocatalyst. Chem. Mater. 2009;21:3562–3569. doi: 10.1021/cm901161g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao G., Yin Y., Wang H., Liu G., Wang Z. Sensitive stripping voltammetric determination of Cd(II) and Pb(II) by a Bi/multi-walled carbon nanotube-emeraldine base polyaniline-Nafion composite modified glassy carbon electrode. Electrochim. Acta. 2016;220:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.10.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tseliou F., Avgeropoulos A., Falaras P., Prodromidis M.I. Low dimensional Bi2Te3-graphene oxide hybrid film-modified electrodes for ultra-sensitive stripping voltammetric detection of Pb(II) and Cd(II) Electrochim. Acta. 2017;231:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2017.02.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Promphet N., Rattanarat P., Rangkupan R., Chailapakul O., Rodthongkum N. An electrochemical sensor based on graphene/polyaniline/polystyrene nanoporous fibers modified electrode for simultaneous determination of lead and cadmium. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015;207:526–534. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.10.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang B., Chen J.D., Zhu H., Yang T.T., Zou M.L., Zhang M., Du M.L. Facile and green fabrication of size-controlled AuNPs/CNFs hybrids for the highly sensitive simultaneous detection of heavy metal ions. Electrochim. Acta. 2016;196:422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.02.163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu C., Wu K., Dai X., Hu S. Simultaneous determination of lead(II) and cadmium(II) at a diacetyldioxime modified carbon paste electrode by differential pulse stripping voltammetry. Talanta. 2003;60:17–24. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(03)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao F., Gao N., Nishitani A., Tanaka H. Rod-like hydroxyapatite and Nafion nanocomposite as an electrochemical matrix for simultaneous and sensitive detection of Hg2+, Cu2+, Pb2+ and Cd2+ J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016;775:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2016.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cesarino I., Marino G., Matos J.R., Cavalheiro E.T. Evaluation of a carbon paste electrode modified with organofunctionalised SBA-15 nanostructured silica in the simultaneous determination of divalent lead, copper and mercury ions. Talanta. 2008;75:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2007.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]