Abstract

A novel method to obtain Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposites is presented. It consists of the co-precipitation step of boehmite (AlO(OH)) and ZrO2, followed by microwave hydrothermal treatment at 270 °C and 60 MPa, and by calcination at 600 °C. Using this method, we obtained two nanocomposites: Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 and Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2. Nanocomposites were characterized by Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, and transmission electron microscopy. Sintering behavior and thermal expansion coefficients were investigated during dilatometric tests. The sintering temperatures of the nanocomposites were 1209 °C and 1231 °C, respectively—approximately 100 °C lower than reported for such composites. We attribute the decrease of the sintering temperature to the specific nanostructure obtained using microwave hydrothermal treatment instead of conventional calcination. Microwave hydrothermal treatment resulted in a fine distribution of intermixed highly crystalline nanoparticles of boehmite and zirconia. Such intermixing prevented particle growth, which is a factor reducing sintering temperature. Further, due to reduced grain growth, stability of the θ-Al2O3 phase was extended up to 1200 °C, which enhances the sintering process as well. For the Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 composition, we observed stability of the zirconia tetragonal phase up to 1400 °C. We associate this stability with the mutual separation of zirconia nanoparticles in the alumina matrix.

Keywords: microwave hydrothermal synthesis, Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposites, shrinkage temperature, grain boundaries, isolation effect of t-ZrO2, phase composition

1. Introduction

Alumina-toughened zirconia (ATZ) and zirconia-toughened alumina (ZTA) are important materials for high-temperature structural [1,2,3] and medical [4,5,6,7] applications due to their excellent strength and toughness, high wear resistance and temperature stability, and the fact that they are both chemically inert. In order to obtain these properties, the tetragonal metastable phase of zirconia (t-ZrO2) needs to remain stable at room temperature; however, t-ZrO2 is normally only stable at temperatures above 1170 °C. One method for ensuring that t-ZrO2 remains stable at room temperature is to partially stabilize it with an yttria (Y2O3) dopant (YSZ) [4,5,6,8,9].

In general, there are two ways to stabilize t-ZrO2 particles: the first is by alloying them with other materials while the other is by ensuring that their particle size does not exceed 35 nm. Stabilization of the t-ZrO2 phase requires certain special synthesis techniques to be used, especially when one desires to have a uniform zirconia particle distribution in an alumina matrix [10,11]. Recent work has shown that synthesizing Al2O3 with ZrO2 nanopowders (up to ~40 wt % ZrO2) could lead to the partial stabilization of t-ZrO2 [12].

In ZTA composites, t-ZrO2 nanoparticles are stable at room temperature; however, under stress, these nanoparticles may undergo a transformation from the tetragonal to the monoclinic phase [8,13,14]. More specifically, if cracks were to propagate through such a ceramic, then any t-ZrO2 particles in the region of the crack could potentially undergo a martensitic transformation from the tetragonal (t-ZrO2) to the monoclinic phase (m-ZrO2); a volume expansion of about 3% would also occur. This would generate compressive stresses in the alumina matrix, preventing the crack from increasing in size and causing the fracture toughness of the ceramic to increase [15,16].

Various chemical methods have so far been used to synthesize Al2O3–ZrO2 and YSZ/Al2O3 ceramics, such as the sol-gel method [17], hydrothermal synthesis followed by calcination [18], and the co-precipitation method [19]. Another method, the microwave hydrothermal synthesis method (MHS), has been found to be particularly attractive due to its potential to produce highly crystalline nanoparticles with a narrow particle size distribution [20,21].

Microwave hydrothermal synthesis (MHS) is a method which possesses many advantages in comparison to standard heating methods [20,21,22]. Firstly, the MHS method is characterized by considerably shorter reaction time. In very short time, the reaction vessel is heated up rapidly and uniformly and the precipitate is heated directly through the energy of microwaves. As a result, heat is generated within the whole volume of the sample and not transported through the reaction vessel walls from an external heat source [22]. Secondly, thanks to uniform heating, the crystallization process in the sample is quick and uniform, resulting in a narrow and nanometric particle size distribution [21,22,23,24]. Another advantage is that reaction vessels used in MHS do not introduce contaminants by the contactless heating method. In addition, the low thermal conductivity (0.25 W/(m K)) of Teflon® causes a small temperature gradient between a sample and a vessel which contributes to the uniformity of the product [21]. The biggest advantage of microwave synthesis over other synthesis methods is that it delivers energy directly to the substance without thermal-conductivity-related constraints [22].

Microwave hydrothermal synthesis methods can be used to produce nanomaterials with a variety of morphologies and programmed sizes. Variations in these attributes can significantly affect the properties of final products [25]. Furthermore, using MHS for the production of ZrO2–Al2O3 nanopowders may lead to the isolation of t-ZrO2 in the alumina matrix in these materials, and thus to the reduction of aggregation.

ZrO2–Al2O3 nanocomposites are often obtained by the sintering of compactified powders [11,26,27,28,29]. The microstructure of a ceramic depends upon the structure of the initial materials used for its synthesis, the dopant distribution used, the heating rate, and the sintering mechanism used. For the manufacture of Al2O3–ZrO2 ceramics, it is crucial that a suitable sintering temperature is chosen. One study that illustrates this was conducted by Zhuravlev et al. [30], who showed that the maximum density of Al2O3 ceramics with partially stabilized ZrO2 (3YSZ) was achieved during sintering at 1400–1500 °C. The density of composite decreased and the open porosity of the ceramic materials grew with increasing amount of Al2O3. Several studies have manufactured dense ceramics while maintaining a small grain size; most of them used optimized sintering strategies or advanced sintering techniques [11,26,31]. Numerous analyses of the mechanical properties of Al2O3–ZrO2 composite systems have also been reported upon [32,33,34,35,36,37], and a wide range of results have been presented. These results were influenced by the fabrication routes used, the composition design, and the measurement technique used.

However, there is a lack of data in the literature about the sintering behavior of Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposites obtained by the method involving co-precipitation and subsequent MHS. Co-precipitation leads to the uniform distribution of components which is very difficult to achieve when mixing the two powders. MHS, meanwhile, leads to the creation of fully crystalline particles (which are not synthesized in the sol-gel process). The sintering of fully crystalline particles may lead to ceramic structures being created than could not be obtained by the sintering of sol-gel-precipitated particles.

The aim of the work was to develop a new method for the manufacturing of Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposites with stable t-ZrO2 and with reduced sintering temperature. The present work reports a series of experiments for finely grained Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposites with 20 and 40 wt % ZrO2. Nanocomposites were obtained by co-precipitation and MHS before being thermally treated. We discuss the roles that chemical composition, morphology, and phase composition had in reducing the sintering temperature used for the synthesis of nanocomposites to levels significantly below that found in the literature for Al2O3–3YSZ and Al2O3–ZrO2.

2. Materials and Methods

The procedure for synthesizing nanopowders containing boehmite (AlO(OH)) with 20 and 40 wt % ZrO2 is described in detail elsewhere [12]. The reagents used in the process were zirconyl chloride octahydrate (ZrOCl2·8H2O, Sigma-Aldrich (≥99.5%)), sodium hydroxide (CHEMPUR, analytically pure), and aluminium nitrate nonahydrate (Al(NO3)3·9H2O, CHEMPUR, analytically pure). Microwave reactions took place in a MAGNUM II ERTEC microwave reactor (2.45 GHz, 600 W). The synthesis of a homogenous mixture of Al2O3 and ZrO2 nanocomposites took place in four steps:

The first was the co-precipitation of the precursors;

The second was 20 min of MHS at t = 270 °C and p = 60 atm, in order to obtain a crystalline mixture of AlO(OH) and ZrO2;

The third was the drying of the precipitates at room temperature. The mixture of nanopowders obtained in step three will be called AlO(OH)–ZrO2 or as-synthesized;

The fourth step was calcination of nanopowder mixture at 600 °C for 2 h in order to obtain ZrO2 with γ-Al2O3 originated from AlO(OH).

Following the above-described four-step procedure, a homogenous mixture of Al2O3 and ZrO2 nanopowders was produced. For the characterization experiments carried out in this work, some of the calcinated powders were also conventionally sintered in air at 1200, 1400 and 1500 °C for 1 h.

Samples were prepared for inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, Perkin-Elmer, Optima 8300, Waltham, MA, USA) in a microwave mineralizer (AntonPaar, MW 3000, Graz, Austria) in a Teflon vial using a mixture of acids, namely, HF/HNO3 and H2SO4. The ICP-OES tests were conducted according to the standard procedure described in EN ISO 11885:2009 [38].

Before and after heating, samples were examined using a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Bruker Optics, Tensor 27, Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany) equipped with a diamond attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory. The diamond ATR crystal was soldered onto a ceramic plate; this resulted in the sampling area being chemically inert and mechanically rugged. All of the ATR-FTIR spectra were recorded at room temperature in the 4000–400 cm−1 range. The spectral resolution and accuracy of the measurements were ±4 cm−1 and ±1 cm−1, respectively.

A Raman scattering spectroscope (Horiba-Jobin-Yvon, LabRam, HR800, Kyoto, Japan) operated with a λ = 532 nm laser was used to investigate samples annealed at 600 and 1400 °C. In order to prevent the samples from degrading, a 10% filter was used. Additionally, an aperture size of 100 μm was used.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the nanopowders were collected on a diffractometer (X’Pert PRO, PANalytical, Almelo, Netherlands) equipped with a copper anode (Cu Kα1) and an ultra-fast PIXcel1D detector. The analysis was performed at room temperature in the 2θ range of 10–100° with a step size of 0.03°. All of the diffraction data was analyzed using advanced data processing methods, including Rietveld refinement [39], by the programs DBWS [40] and FullProf [41]; these were used for the structural and quantitative phase analyses, respectively. The peak shape function used in calculation was pseudo-voigt.

The surface morphology was evaluated using a scanning electron microscope (Zeiss, Ultra Plus, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), and the compositions of the nanopowders were estimated semiquantitatively using energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) (QUANTAX 400, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). For this evaluation, the synthesized materials were compacted to pellets and sintered at 1300 °C for 1 h. Measurements were done as per the ISO 22309:2011 standard [42].

The microstructures of the nanopowders and nanocomposites were investigated using conventional high-resolution (HR) transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning (STEM) techniques with a FEI TECNAI G2 F20 S-TWIN electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Helium density measurements were carried out using a helium pycnometer (AccuPyc II 1340, FoamPyc V1.06, Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA). The measurements were carried out in accordance with the ISO 12154:2014 standard [43] at temperatures of 25 ± 2 °C.

The specific surface area (SSA) of the nanopowders was determined in accordance with ISO 9277:2010 [44]; more specifically, a surface analyzer (Gemini 2360, V 2.01, Norcross, GA, USA) that used the nitrogen adsorption method was used, and this method was based on the linear form of the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) isotherm equation. The detailed experimental procedure and the determination of particle size using the BET method (SSABET) is described elsewhere [12].

In order to calculate the crystallite diameter and size distribution, equations dedicated to spherical crystallites in the Nanopowder XRD Processor Demo (Pielaszek Research) web application were used. The website provides an online tool in which diffraction files can be directly uploaded [45]; the files are then processed on a server and the particle size distribution for the XRD peaks is extracted.

The nanopowders calcinated at 600 °C were compacted at room temperature in a stainless steel mold under 250 bar. Dilatometric experiments were also carried out; for these, cylindrical specimens with 5 mm diameters and ca. 5 mm heights were prepared. The shrinkage behavior of bulk samples and their relative changes in length were examined using a Netzsch DIL 402 PC/4 dilatometer in an argon ambient atmosphere between 40 and 1500 °C at a constant heating and cooling rate of 2 °C min−1. The densification rate was obtained by differentiating the measured linear shrinkage data. The temperature at which a change in the slope of the dilatometric relative length curve occurred was taken as being the phase transition temperature.

3. Results

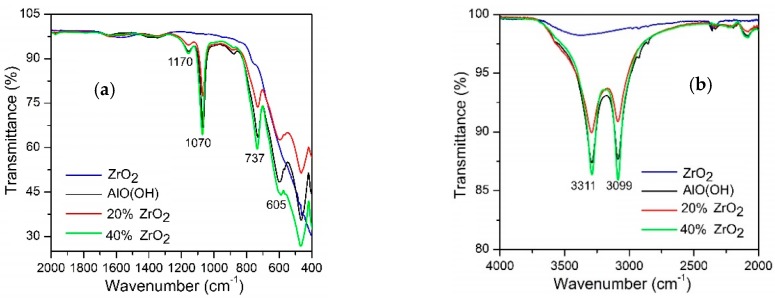

Figure 1 shows the FTIR spectra for (a), (b) as-synthesized AlO(OH)–ZrO2 nanopowders, (c) nanopowders after calcination at 600 °C, and (d) after annealing at 1400 °C. Pure ZrO2, boehmite (AlO(OH)), and Al2O3 were added as references. The bands observed for the as-synthesized samples were identified; they are listed in Table 1 [10,36,37,46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

Figure 1.

FTIR spectra for Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 in as-synthesized form (a,b), calcined at 600 °C (c), and after annealing at 1400 °C (d).

Table 1.

Characterization of FTIR-ATR bands in Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 samples.

| ZrO2 Bands in As-Synthesized Samples (cm−1) | Literature | AlO(OH) Bands in As-Synthesized Samples (cm−1) | Literature |

| 472, 605 | Bands between 780 and 500 cm−1 can be assigned to the vibration mode of AlO6 [36] | ||

| 737 | Al–O–Al framework [37] | ||

| 900 | Al–O band stretching vibration of boehmite [10] | ||

| 1070, 1170 | (HO)–Al=O asymmetric stretching and the O–H bending, respectively [46] | ||

| 1338 | Bending vibration of Zr–OH groups [37], and it might be t-ZrO2 [48] | 1170 | Al–O–H vibrations [48] |

| 1566 | t-ZrO2 [48] | 1668 | O–H bending mode [37] |

| 3357 | Stretching vibration of hydroxyl group and the interlayer water molecules [40] | 3099, 3311 | Asymmetric and symmetric O–H stretching vibrations from (O)Al–OH [37] |

| ZrO2 Bands in Annealed Samples (cm−1) | Literature | Al2O3 Bands in Annealed Samples (cm−1) | Literature |

| 440 | symmetric Zr–O–Zr stretching mode related with t-ZrO2 phase [46] It might me ν(Zr–O) band from t-ZrO2 [51] |

447 | Al–O stretching mode in α-Al2O3 [47] |

| 484 | t-ZrO2 [52], stretching vibrations of Zr–O in ZrO2 | 495 | α-Al2O3 [47] |

| 567 719 |

Zr–O stretching vibrations [50] | 595 | Al–O stretching mode in octahedral structure [50] |

| 642 | asymmetric Zr–O–Zr stretching mode from the m-ZrO2 phase [49] |

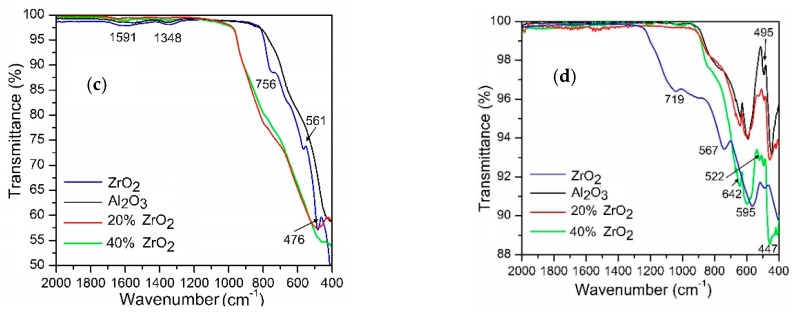

Figure 2 shows Raman spectra for Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposites calcinated at 600 °C and for pellets sintered at 1400 °C. The relevant peaks reported in the literature for t-ZrO2, m-ZrO2, and Al2O3 are listed in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Raman spectra for (a) Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 after annealing at 600 °C, (b) Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 after annealing at 1400 °C, and (c) Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 after annealing at 1400 °C.

Table 2.

Raman spectral data for Al2O3–(40,20 wt %) ZrO2 after annealing at 600 °C and 1400 °C [45,52,53,54,55].

| Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 after Annealing at 600 °C | Wavenumbers (cm−1) | Literature | Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 after Annealing at 1400 °C | Wavenumbers (cm−1) | Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al2O3–(20 wt %) ZrO2 after annealing at 1400 °C | |||||

| t-ZrO2 | 148, 265, 312 | [49] | t-ZrO2 | 147, 270, 315, 459 | [49] |

| m-ZrO2 | 177, 188, 215, 355, 382, 477, 513, 559, 637 | [49] | m-ZrO2 | 179, 190, 381, 419, 578, 647 | [49] |

| γ-Al2O3 | 234, 404 | [52,53] | α-Al2O3 | 381, 419, 431,578,647, 751 | [52,53,54,55] |

| Al2O3–(40 wt %) ZrO2 after annealing at 1400 °C | |||||

| t-ZrO2 | 145,269, 314, 456 | [49] | |||

| m-ZrO2 | 179, 190, 336, 351, 380, 417, 477, 507, 598, 647 | [49] | |||

| α-Al2O3 | 380, 417, 647, 753 | [52,53,54,55] | |||

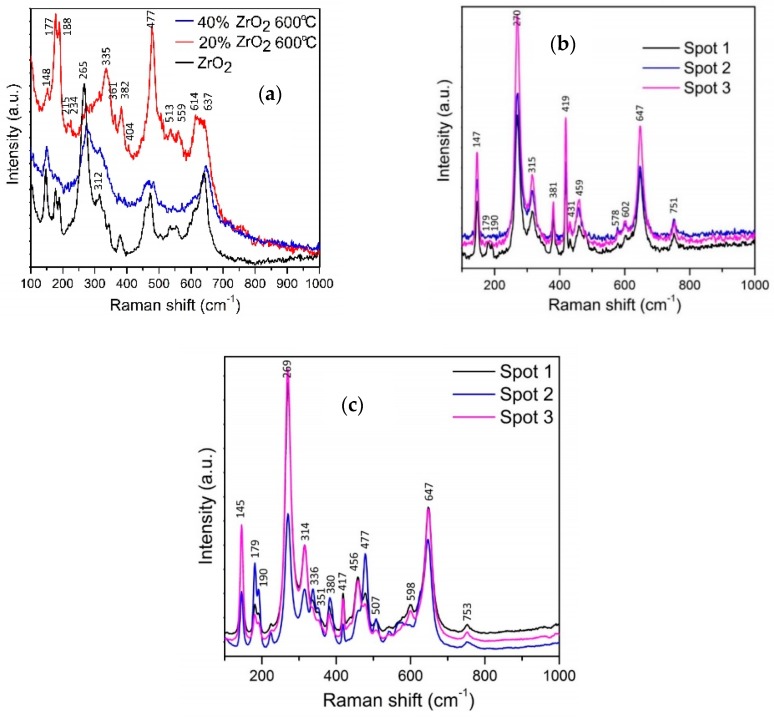

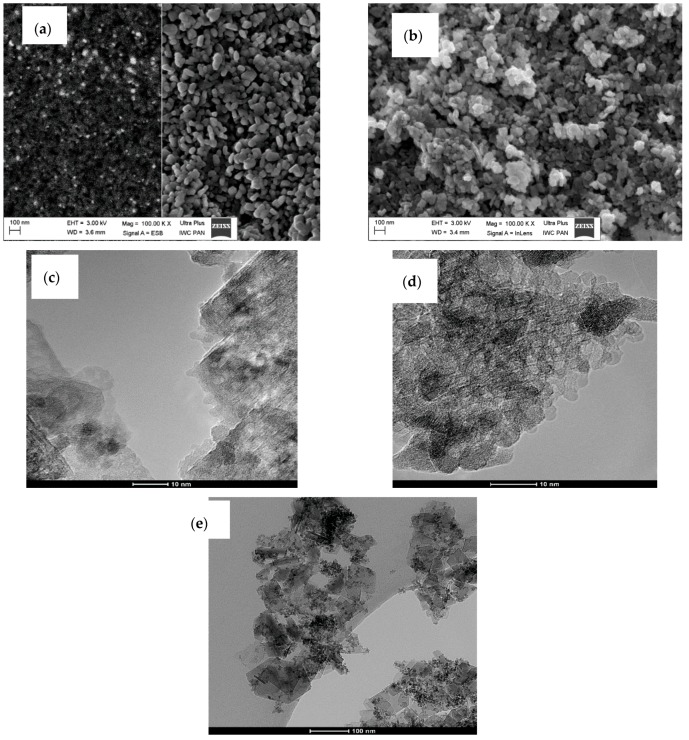

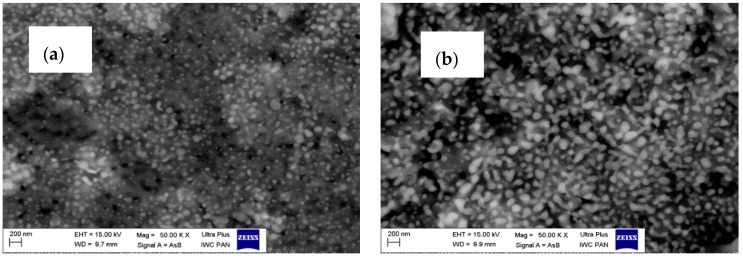

The morphology of as-synthesized AlO(OH)–ZrO2 nanopowders is presented in Figure 3. There is very little difference between samples in terms of shape and particle size. In addition, Figure 4 shows TEM and SEM images of morphology and structure for nanocomposites obtained after annealing at 1400 °C.

Figure 3.

SEM and TEM images for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 after synthesis (a,c), and Al2O3 with 40 wt % ZrO2 after synthesis (b,d,e).

Figure 4.

SEM and TEM images for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 after annealing at 1400 °C (a,c,e), and Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 after annealing at 1400 °C (b,d,f).

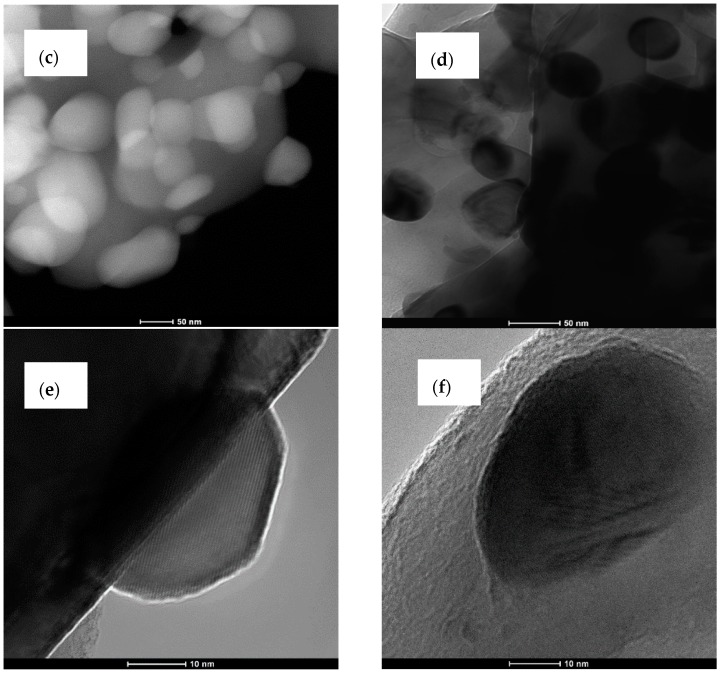

Particle size distributions for ZrO2 phases (both t-ZrO2 and m-ZrO2) are shown in Figure 5. Calculation was prepared based on XRD experiments.

Figure 5.

Particle size distribution for Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 nanocomposites after annealing at 1400 °C.

The results for SSABET and density of nanopowders after calcination at 600 °C and 1400 °C are shown in Table 3. For both compositions there is visible difference in SSABET values after annealing at 600 °C: 177.2 for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 and 95.9 m2/g for Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2. The density values are comparable (3.5 g/cm3 for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 and 3.8 g/cm3 for Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2).

Table 3.

Comparison of specific surface area (SSABET), helium density, and particle size for Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 nanocomposites annealed at 600 °C and 1400 °C.

| Composition (wt %) | Thermal Treatment | Specific Surface Area SSABET (m2/g) | Helium Density (g/cm3) | Densification (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al2O3–20% ZrO2 | 600 °C | 177.2097 ± 0.6228 | 3.5442 ± 0.0062 | 84 |

| 1400 °C | 3.3659 ± 0.0085 | 4.2073 ± 0.0087 | ||

| Al2O3–40% ZrO2 | 600 °C | 95.9208 ± 0.4215 | 3.8257 ± 0.0455 | 90 |

| 1400 °C | 0.5900 ± 0.0042 | 4.2260 ± 0.0133 |

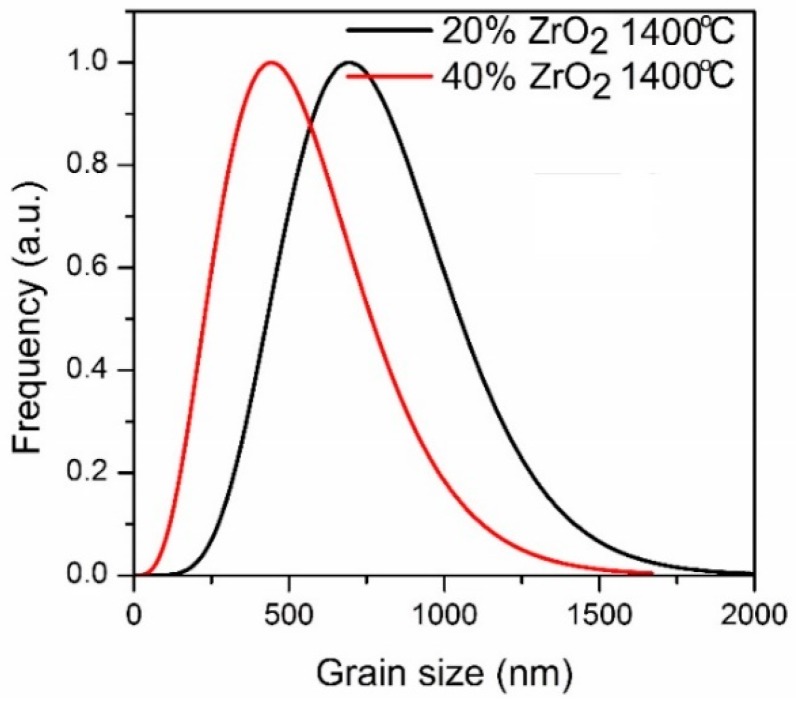

Figure 6 shows dilatometry curves for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 and Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 with three distinguished regions characteristic of the sintering process.

Figure 6.

Dilatometric curves for Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 nanocomposites (solid lines), where dotted lines represent first derivative.

In Table 4 we show results of chemical and phase composition of Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 nanocomposites annealed in the 600–1400 °C temperature range. These results were obtained from ICP-OES, EDS, and Rietveld refinement analysis.

Table 4.

Chemical and phase composition of Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 nanocomposites annealed in the 600–1400 °C temperature range.

| Composition (wt %) | EDS (wt % of ZrO2) | ICP-OES (wt % of ZrO2) | Phase Composition Obtained from Rietveld Refinement for Samples after Annealing at Different Temperatures (wt %) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 600 °C | 1200 °C | 1400 °C | |||

| Al2O3–20% ZrO2 | 20.14 ± 1.37 | 21 ± 1.09 | 83.3 ɣ −Al2O3 | 82.3 θ−Al2O3 | 80.5 α−Al2O3 |

| 12.9 t−ZrO2 | 14.5 t−ZrO2 | 12.6 t−ZrO2 | |||

| 3.8 m−ZrO2 | 3.2 m−ZrO2 | 6.8 m−ZrO2 | |||

| Al2O3–40% ZrO2 | 38.47 ± 2.61 | 40 ± 0.81 | 67.4 ɣ −Al2O3 | 61.3 θ −Al2O3 | 59.4 α−Al2O3 |

| 25.9 t−ZrO2 | 13.8 t−ZrO2 | 8.0 t−ZrO2 | |||

| 6.7 m−ZrO2 | 24.9 m−ZrO2 | 32.6 m−ZrO2 | |||

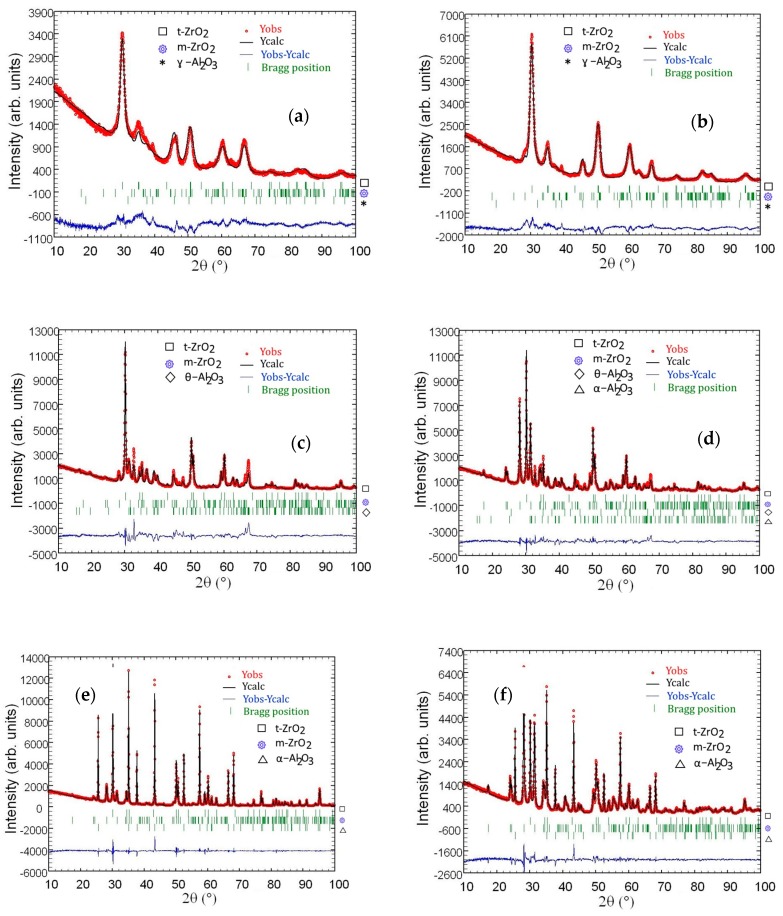

Rietveld refinements for Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 nanocomposites are presented in Figure 7. Refinement was performed for nanocomposites after annealing at 600 °C, 1200 °C and 1400 °C. Peak positions coming from analyzed phases are marked on the figures. Atom positions in analyzed phases as well as cell parameters are presented in Table 5 and Table 6.

Figure 7.

Rietveld refinement for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 after annealing at 600 °C for 2 h (a), 1200 °C (c), 1400 °C (e), and Al2O3–40 wt % of ZrO2 after annealing at 600 °C for 2 h (b), 1200 °C (d), 1400 °C (f).

Table 5.

Atom position in θ-Al2O3, α-Al2O3, m-ZrO2, and t-ZrO2 based on Rietveld refinement.

| Phase: θ-Al2O3, C 2/m | Phase: m-ZrO2, P 21/c | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atom Position | x | y | z | Atom Position | x | y | z |

| Al1:Al3+ | 0.10130 | 0.00000 | 0.79440 | Zr:Zr4+ | 0.27605 | 0.03987 | 0.20927 |

| Al2:Al3+ | 0.35230 | 0.00000 | 0.68740 | O1:O2− | 0.06633 | 0.33052 | 0.34468 |

| O1:O2− | 0.16270 | 0.00000 | 0.12280 | O2:O2− | 0.45232 | 0.75875 | 0.47537 |

| O2:O2− | 0.48950 | 0.00000 | 0.26130 | ||||

| O3:O2− | 0.82990 | 0.00000 | 0.43860 | ||||

| Phase: α-Al2O3, 167 | x | y | z | Phase: t-ZrO2, P 42/nmc | x | y | z |

| Al:Al3+ | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.35230 | Zr:Zr4+ | 0.75000 | 0.25000 | 0.75000 |

| O:O2− | 0.30640 | 0.00000 | 0.25000 | O:O2− | 0.25000 | 0.25000 | 0.55000 |

Table 6.

Cell parameters of θ-Al2O3, α-Al2O3, m-ZrO2, and t-ZrO2 phases calculated in Rietveld refinement for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 and Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 nanocomposites annealed at 1200 °C and 1400 °C.

| Unit Cell Dimensions in Al2O3–20 wt %ZrO2 | |||||||

| T = 1200 °C | T = 1400 °C | ||||||

| Phase: | t-ZrO2 | Phase: | t-ZrO2 | ||||

| a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) | α,β,γ (o) | a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) | α, β, γ (o) |

| 3.597020 | 3.597020 | 5.191563 | α = β = γ 90.0000 |

3.598789 | 3.598789 | 5.200136 | α = β = γ 90.0000 |

| Phase: | m-ZrO2 | Phase: | m-ZrO2 | ||||

| 5.093851 | 5.141055 | 5.313514 | α = γ; β 90.0000; 100.5483 |

5.149243 | 5.186935 | 5.318353 | α = γ; β 90.0000; 99.0302 |

| Phase: | θ-Al2O3 | Phase: | α-Al2O3 | ||||

| 11.802021 | 2.911568 | 5.622274 | α = γ; β 90.0000; 104.0478 |

4.760565 | 4.760565 | 12.996780 | α = β; γ 90.0000; 120.0000 |

| Unit Cell Dimensions in Al2O3–40 wt %ZrO2 | |||||||

| T = 1200 °C | T = 1400 °C | ||||||

| Phase: | t-ZrO2 | Phase: | t-ZrO2 | ||||

| a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) | α,β,γ (o) | a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) | α,β,γ (o) |

| 3.597343 | 3.597343 | 5.194126 | α = β = γ 90.0000 |

3.599882 | 3.599882 | 5.200407 | α = β = γ 90.0000 |

| Phase: | m-ZrO2 | Phase: | m-ZrO2 | ||||

| 5.146611 | 5.188430 | 5.310700 | α = γ; β 90.0000; 98.9165 |

5.152256 | 5.190232 | 5.315270 | α = γ; β 90.0000; 99.0657 |

| Phase: | θ-Al2O3 | Phase: | α-Al2O3 | ||||

| 11.795719 | 2.911480 | 5.620936 | α = γ; β 90.0000; 104.0352 |

4.762267 | 4.762267 | 12.999507 | α = γ; β 90.0000; 120.0000 |

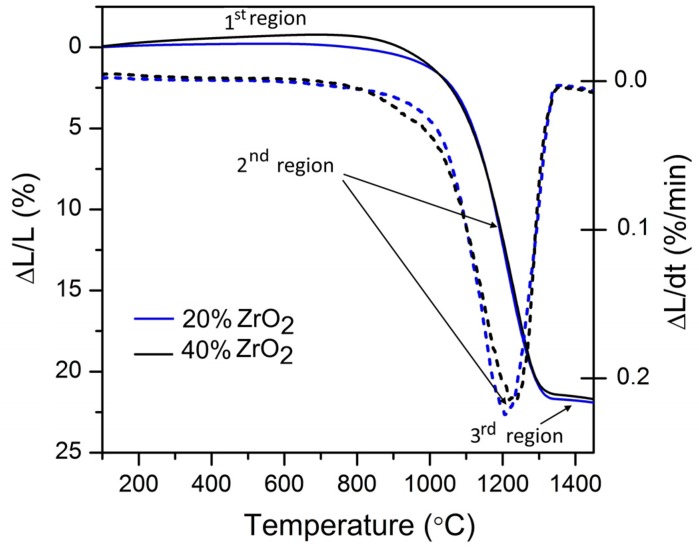

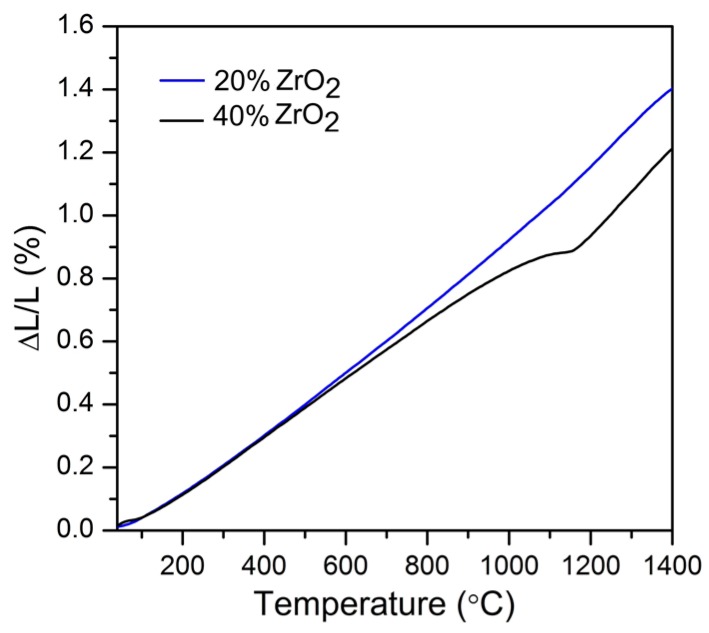

The thermal parameters obtained from dilatometric experiments (including sintering temperature calculated using maximum shrinkage rate) are shown in Table 7. The thermal expansion coefficients were obtained by fitting the relative elongation as a function of temperature with linear functions (Figure 8).

Table 7.

Thermal properties for Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 nanocomposites obtained from dilatometry experiments.

| Composition (wt %) | Sintering Temperature (°C) | Thermal Expansion Coefficient 1 (10−6 K−1)/Structure | Transition Temperature (°C) | |

| t-ZrO2 | m-ZrO2 | |||

| Al2O3–20% ZrO2 | 1209 | 10.29 | N/A | N/A |

| Al2O3–40% ZrO2 | 1231 | 8,99 | 13,84 | 1153 |

1 Thermal expansion coefficients with corresponding transition temperatures obtained for nanocomposites sintered at 1500 °C.

Figure 8.

Shrinkage behavior of Al2O3–(20,40 wt %) ZrO2 nanocomposites.

4. Discussion

FTIR spectra show that there were signals associated with Al–O–H; these bands are characterized by bands in the OH– and water regions at 3311 and 3309 cm−1, respectively, in Figure 1a as well as by bands originating from Al–O in Figure 1b. In the figure, it can be seen that for Al2O3–ZrO2 (20 and 40 wt %) which are calcinated at 600 °C (Figure 1b), the only well-resolved peak that can be associated with ZrO2 is that of a broad shoulder that has a maximum at 476 cm−1, which can be assigned to t-ZrO2. Following calcination at 600 °C, alumina exists in the form γ-Al2O3; this is due to a boehmite transformation. Following annealing conducted at 1400 °C, the materials can be characterized by bands originating from Al2O3.

Raman results indicate that all compositions calcinated at 600 °C contained both moclinic and tetragonal zirconia phases. The amount of m-ZrO2 is significantly lower for Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 compared to Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 samples (Figure 2a). Furthermore, the Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 composite contains a significantly higher amount of t-ZrO2 than a pure ZrO2 sample (e.g., without any addition of Al2O3). These observations are in agreement with XRD results described in further paragraphs.

Annealing at 1400 °C of the Al2O3–20 wt %ZrO2 composition demonstrates that the t-ZrO2 phase dominates over the monoclinic phase and that the sample is homogeneous (Figure 2c). On the other hand, the composition of Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 shows that ZrO2 particles are mostly in the monoclinic phase (Figure 2c). Further analysis of the sample at several locations revealed that the sample is not homogeneous with some parts containing a considerable amount of t-ZrO2. It is possible to draw a conclusion that a higher content of ZrO2 leads to greater presence of m-ZrO2. Two pronounced peaks at 177 and 188 cm−1 indicate that Al2O3 has a stabilizing effect on t-ZrO2 in the case of the Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 composition.

Composites present two types of morphologies: boehmite thin flakes (with particle size ~160 nm), and spherical zirconia particles (with particle size ~3 nm) (Figure 3). Boehmite flakes have rough dimpled surfaces, and the ZrO2 particles are attached to boehmite flakes. The mean particle size for the Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 sample is visibly smaller than that for the Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2. Both phases—ZrO2 and boehmite—are uniformly distributed on the SEM and TEM images. Annealing at 1400 °C leads to a visible increase in the ZrO2 particle size (Figure 4). In addition, ZrO2 particles (spherical, dark particles) for both composition are isolated in the Al2O3 matrix and they are prevented from further growing (Figure 4c,d).

On the other hand, the results of the particle size distributions for ZrO2 phases (both t-ZrO2 and m-ZrO2) presented in Figure 5 show differences between compositions. The mean alumina particle size after sintering at 1400 °C was 480 nm for Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2, and 750 nm for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2, while the average size of the t-ZrO2 grains based on TEM observations was 30 nm for both compositions. From TEM images it is also possible to infer that a and c lattice spacings are different in these grains, which confirms that their structure is tetragonal (Figure 4e).

As expected, the specific surface area (SSABET) and density of the samples were affected by annealing at 600 °C and 1400 °C. The specific surface area for both compositions after annealing at 1400 °C was strikingly different compared to the values obtained after only annealing at 600 °C.

The nanoparticles’ size, size distribution, and morphology influence phase transformations in the alumina and zirconia composites. Furthermore, the phase transformation of Al2O3 influences the densification process. In the following paragraph, we will therefore discuss the sintering behavior of Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposites in relation to the phase composition.

Dilatometry results for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 and Al2O3–40 wt% ZrO2 are presented in Figure 6. Other thermal properties of nanocomposites were previously reported in [56]. Three distinctive regions in dilatometry curves can be found:

The first (1) refers to the temperature range before the nanocomposite will shrink (before onset temperature—Ton). This is the rearrangement region [57] which is visible from RT up to 1100 °C for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2, and up to 1150 °C for Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2. Both of these values are approximately 100 °C lower than results published recently for a similar system by Scoton et al. [57].

The second (2) step belongs to the shrinkage process, where the maximum shrinkage rates are found at 1208 °C for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 and 1231 °C for Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2. Both of these temperatures are also from 100 to 200 °C lower compared to relevant literature [57,58].

The third (3) step distinguished on the dilatometry curves belongs to the end of the sintering process. The end of the sintering process for both compositions appears at approximately 1300 °C, and is associated with a 22% change of length.

It is important to analyze in detail the phase transformations for the ZrO2 nanoparticles in the temperature range from 1200 °C to 1400 °C, since nanoparticles sinter rapidly in this temperature region. The results of phase analysis for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 and Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 nanopowders as a function of annealing temperature are shown in Figure 7. The phase content of as-synthesized powders was described before [12] and it is composed of fully crystalline boehmite, t-ZrO2, and m-ZrO2. Annealing at 600 °C leads to an AlO(OH)→ɣ-Al2O3 transformation. Subsequent annealing of Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 and Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 at 1200, 1400 and 1500 °C causes the following alumina transformation: ɣ-Al2O3→θ-Al2O3→α-Al2O3.

It is known that the specific temperatures for alumina transitions depend on the dopant concentration and alumina mean particle size [59]. In particular, the additives that reduce alumina particle growth during sintering and reduce nucleation sites α-Al2O3 (for example, ZrO2) [59] strongly influence phase transition temperatures. The second step of alumina nanoparticle transformation (θ-Al2O3→α-Al2O3) in nanocomposites is critical to understanding the sintering. For this reason, it is important to determine the temperature regions of stability of the θ-Al2O3 (theta alumina) phase. Sintering of nanosized Al2O3 powders accompanied by grain growth is explained by polymorphic phase transformations [60].

The effects of phase transformation on various Al2O3–ZrO2 composites sintering was already discussed in the literature [10,30,59,60,61,62]. For example, Chen et al. [10] found that shrinkage of Al2O3–ZrO2 composites is related to the θ→α-Al2O3 phase transformation taking place in the second step of sintering. During this stage, the coalescence of crystallites and necking were developed, which retarded densification as well as shrinkage. According to the authors [10], the final densification temperature is affected by the microstructure after the θ→α-Al2O3 phase transformation. The authors [10] found that the phase composition of the composite at various annealing temperatures depends on the aging time of the precipitated mixture obtained in the sol-gel process prior to sintering. They reported [10] that the phase transformation of θ-Al2O3 into α-Al2O3 can be shifted to temperatures higher than 1300 °C due to aging. Such phase transformation appears to be thanks to the transformation of nano-sized Al2O3 powder, and is connected to nucleation and growth processes. It was found that the shorter the aging time, the stronger the interaction between ZrO2 and Al2O3 particles [10]. Additionally, precipitated ZrO2 particles can prevent Al2O3 particles from contact which suppresses coalescence and delays θ→α phase transformation.

Lamouri et al. [59], who discussed transition of alumina phases and their influence on densification process, found that densification of alumina takes place due to nucleation and grain growth mechanisms. This process is influenced by grain size, starting nanoparticle morphology, dynamics of θ→α phase transformation in Al2O3, and the heating rate of the sintering process. The slow heating rate of the sintering process reduces the temperature of α-Al2O3 formation which is characterized by high activation energy [59].

In our case, θ-Al2O3 was observed in both materials even after annealing at temperatures higher than 1200 °C. According to recent publications [60,61,62], any grain growth process would lead to transformation of theta to alpha phase (α-Al2O3). In fact, Lamouri et al. [59] found that θ→α-Al2O3 phase transformation can happen only after θ-Al2O3 coarsens to a critical size (~20 nm). Such coarsening is underpinned by the Ostvald ripening process. The Ostvald ripening rate is determined by the probability of contact between two θ-Al2O3 particles and the material diffusion process. The precipitated zirconia particles can prevent θ-Al2O3 particles from coming into contact, thus suppressing the coalescence of θ-Al2O3 particles which in turn delays the θ→α-Al2O3 phase transformation. Such suppression of coalescence can be readily achieved in samples made by co-precipitation and quick crystallization in a microwave synthesis reactor.

Thus, above 1000 °C as a result of grain growth, only α-Al2O3 should be observed. It might be assumed that this process has not taken place during the present study because the addition of ZrO2 nanoparticles slows down the alumina particle growth. Rietveld refinement analysis of particle size shows that both compositions after annealing at 1400 °C are characterized by 30–80 nm t-ZrO2 and 50–200 nm m-ZrO2, while alumina particles are approximately 200 nm in diameter in both cases. In addition, ZrO2 nanoparticles remain within the alumina matrix grains as well as at the grain boundaries. The smaller ZrO2 particles seem to be entrapped within the alumina grains and they prevent alumina particles from growing (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Equally, the nanoparticles’ morphology may also influence the transition temperatures between alumina phases. Levin et al. [60] studied phase transformation during annealing of boehmite and showed that the morphology of the starting materials has an influence on the θ→α-Al2O3 phase transformation. Lee et al. [61] showed that the platelet γ-Al2O3 did not transform to α-Al2O3, even after 1100 °C calcination. In our study, the calcination platelet morphology of boehmite was obtained, and no θ to α-Al2O3 transformation was observed up 1200 °C. Our results are in agreement with [61].

An analysis of results presented in Table 4 shows an agreement between nominal (predicted based on the composition of the precursors) and measured weight % of ZrO2 in all materials. The differences of ZrO2 wt % values measured by EDS and ICP-OES methods and by using Rietveld refinement are relatively minor. Our results show that the amount of t-ZrO2 phase in the case of Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 composite varies between 12.7 and 15.9 wt % in the whole temperature range. In the Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2, t-ZrO2 varies between 8 and 25 wt % (Table 4). For the Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 composite, it was observed that amount of the t-ZrO2 phase was constant (within the experimental error) for the whole temperature range investigated (from 600 °C to 1400 °C). The weight ratio of t-ZrO2 to m-ZrO2 was 3.3:1. Only at the 1400 °C temperature was a decrease of t-ZrO2/m-ZrO2 observed. It is interesting to note that the t-ZrO2/m-ZrO2 ratio after sintering up to 1200 °C was very close to the one observed for the composites of Al2O3–3 mol %YSZ presented in [30].

As far as the Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 material is concerned, a different behavior was observed in comparison to the Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2. The t-ZrO2 phase was dominant only after 600 °C annealing. Further annealing causes a systematic increase of the m-ZrO2 phase content. This confirms that Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 has lower thermal stability, and isolation of t-ZrO2 in the Al2O3 matrix is weaker.

It was found that thermal expansion coefficients for Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 vary due to phase transition. Contrary to the Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 composition, Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 is characterized by only one value of thermal expansion coefficient. The thermal expansion coefficient for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 is 10.29 × 10−6 K−1, while those for Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 are 8.99 and 13.84 × 10−6 K−1 (Table 7). This experiment confirms that Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 nanocomposite is not characterized by martensitic transformation (t↔m ZrO2), which is beneficial for mechanical properties. For Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 it was found that the t-ZrO2 phase was stable up to 1400 °C, which is also attributed to nanoparticle separation.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we showed a new method for the manufacturing of Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposites with reduced sintering temperature. The sintering temperatures were found to be 1209 °C for Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 and 1231 °C for Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 nanocomposites. These temperatures were approximately 100 °C lower than previously reported for similar compositions. In the above nanostructures, the θ-Al2O3 nanoparticles are surrounded by small zirconia nanoparticles, which prevent their growth and stabilize the θ-phase up to 1200 °C. The reason for the decrease of the sintering temperature is related to:

Uniform distribution of zirconia nanoparticles within the alumina matrix;

Maintaining up to relatively high temperature a grain size in the nano range. As it is known, the driving force for sintering nanomaterials is higher than that for microcrystals;

θ-Al2O3 stability was extended up to 1200 °C, with enhancement of that phase’s sintering.

For the Al2O3–20 wt % ZrO2 composition, we observed stability of the zirconia tetragonal phase up to 1400 °C. We associate such stability with the mutual separation of zirconia nanoparticles in the alumina matrix. A different behavior was observed for Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2. The t-ZrO2 phase was dominant only after 600 °C annealing. Further annealing causes a systematic increase of the m-ZrO2 phase content. This confirms that Al2O3–40 wt % ZrO2 has lower thermal stability, and isolation of t-ZrO2 in the Al2O3 matrix is weaker.

Acknowledgments

Authors are indebted to Jan Mizeracki for help in SEM analysis, and to Denis Koltsov, Witold Łojkowski, and Jacek Wojnarowicz for scientific discussion.

Author Contributions

I.K. conceived and designed experiments, wrote the paper, synthesized materials, and performed SEM and FTIR tests/analysis of results; J.S.-K. performed TEM imaging; M.P.-W. conducted dilatometry experiments; M.M. prepared pellets for sintering and ran annealing processes; G.K. carried out Rietveld refinement analysis; J.M. and A.G. performed Raman spectroscopy experiments and analysed the data, S.S. performed XRD/particle size distribution analysis. This publication is part of Iwona Koltsov’s habilitation thesis. All authors contributed to discussion and editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Polish National Science Centre grant number: UMO-2013/11/D/ST8/03429- “Sonata 6”. The research subject was partly carried out with the use of equipment funded by the project CePT, reference: POIG.02.02.00-14-024/08, financed by the European Regional Development Fund within the Operational Programme “Innovative Economy” for 2007–2013.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Chandradass J., Kim M.H., Bae D.S. Influence of citric acid to aluminium nitrate molar ratio on the combustion synthesis of alumina–zirconia nanopowders. J. Alloy. Compd. 2009;470:L9–L12. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.02.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei Z., Li H., Zhang X., Yan S., Lv Z., Chen Y., Gong M. Preparation and property investigation of CeO2–ZrO2–Al2O3 oxygen-storage compounds. J. Alloy. Compd. 2008;455:322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2007.01.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J., Taleff E.M., Kovar D. High-temperature deformation of Al2O3/Y-TZPparticulate composites. Acta Mater. 2003;51:3571–3583. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6454(03)00175-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin W., Meng B., Meng X., Tan X. Highly asymmetric YSZ hollow fibre membranes. J. Alloy. Compd. 2009;476:566–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.09.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benzaid R., Chevalier J., Saadaoui M. Fracture toughness, strength and slow crack growth in a ceria stabilized zirconia–alumina nanocomposite for medical applications. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3636–3641. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chevalier J., De-Aza A.H., Fantozzi G., Schehl M., Torrecillas R. Extending the life time of ceramic orthopaedic implants. Adv. Mater. 2000;12:1619–1621. doi: 10.1002/1521-4095(200011)12:21<1619::AID-ADMA1619>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naglieri V., Gutknecht D., Garnier V., Palmero P., Chevalier J., Montanaro L. Optimized Slurries for Spray Drying: Different Approaches to Obtain Homogeneous and Deformable Alumina-Zirconia Granules. Materials. 2013;6:5382–5397. doi: 10.3390/ma6115382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chevalier J., Gremillard L., Virkar A.V., Clarke D.R. The tetragonal-monoclinic transformation in zirconia: Lessons learned and future trends. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009;92:1901–1920. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2009.03278.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vernieuwe K., Lommens P., Martins J., Van Den Broeck F., Van Driessche I., De Buysser K. Aqueous ZrO2 and YSZ Colloidal Systems through Microwave Assisted Hydrothermal Synthesis. Materials. 2013;6:4082–4095. doi: 10.3390/ma6094082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C.-C., Hsiang H., Yen F.S. Effects of aging on the phase transformation and sintering properties of coprecipitated Al2O3-ZrO2 powders. J. Ceram. Proc. Res. 2008;9:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suffner J., Lattemann M., Hahn H., Giebeler L., Hess C., Cano I.G., Dosta S., Guilemany J.M., Musa JC., Locci A.M., et al. Microstructure Evolution During Spark Plasma Sintering of Metastable (ZrO2–3 mol % Y2O3)–20 wt% Al2O3 Composite Powders. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2010;93:2864–2870. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2010.03752.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malka I.E., Danelska A., Kimmel G. The Influence of Al2O3 Content on ZrO2-Al2O3 Nanocomposite Formation—The Comparison between Sol-Gel and Microwave Hydrothermal Methods. Mater. Today Proc. 2016;3:2713–2724. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2016.06.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hannink R.H.J., Kelly P.M., Muddle B.C. Transformation toughening inzirconia—Containing ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2000;83:461–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1151-2916.2000.tb01221.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naglieri V., Palmero P., Montanaro L., Chevalier J. Elaboration of Alumina-Zirconia Composites: Role of the Zirconia Content on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Materials. 2013;6:2090–2102. doi: 10.3390/ma6052090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beitollahi A., Hosseini-Bay Ć.H., Sarpoolaki Ć.H. Synthesis and characterization of Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposite powder by sucrose process. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2010;21:130–136. doi: 10.1007/s10854-009-9880-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Septawendar R., Setiati A., Sutardi S. Low-temperature calcination at 800 °C of alumina–zirconia nanocomposites using sugar as a gelling agent. Ceram. Int. 2011;37:3747–3754. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2011.05.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shukla S., Seal S., Vij R., Bandyopadhyay S. Effect of HPC and water concentration on the evolution of size, aggregation and crystallization of sol–gel nanozirconia. J. Nanopart. Res. 2002;4:553–559. doi: 10.1023/A:1022886518620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Begand S., Oberbach T., Glien W. Corrosion behaviour of ATZ and ZTA ceramic. Bioceramics. 2007;19:1227–1230. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chuang C.-C., Hsiang H.-I., Hwang J.S., Wang T.S. Synthesis and characterization of Al2O3-Ce0.5Zr0.5O2 powders prepared by chemical coprecipitation method. J. Alloy. Compd. 2009;470:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.02.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Opalinska A., Malka I., Dzwolak W., Chudoba T., Presz A., Lojkowski W. Size dependent density of zirconia nanoparticles. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2015;6:27–35. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.6.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lojkowski W., Leonelli C., Chudoba T., Wojnarowicz J., Majcher A., Mazurkiewicz A. High-Energy-Low-Temperature Technologies for the Synthesis of Nanoparticles: Microwaves and High Pressure. Inorganics. 2014;2:606–619. doi: 10.3390/inorganics2040606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wojnarowicz J., Chudoba T., Majcher A., Łojkowski W. Microwave Chemistry. 1st ed. De Gruyter; Berlin, Germany: Boston, MA, USA: 2017. Microwaves applied to hydrothermal synthesis of nanoparticles; pp. 205–224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wojnarowicz J., Opalinska A., Chudoba T., Gierlotka S., Mukhovskyi R., Pietrzykowska E., Sobczak K., Lojkowski W. Effect of water content in ethylene glycol solvent on the size of ZnO nanoparticles prepared using microwave solvothermal synthesis. J. Nanomater. 2016;2016:2789871. doi: 10.1155/2016/2789871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wojnarowicz J., Mukhovskyi R., Pietrzykowska E., Kusnieruk S., Mizeracki J., Lojkowski W. Microwave solvothermal synthesis and characterization of manganese-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2016;7:721–732. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.7.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demazeau G. Solvothermal Processes: Definition, Key Factors Governing the Involved Chemical Reactions and New Trends. Z. Naturforsch. 2010;65:999–1006. doi: 10.1515/znb-2010-0805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lóh N.J., Simão L., Jiusti J., De Noni A., Montedo O.R.K. Effect of temperature and holding time on the densification of alumina obtained by two-step sintering. Ceram. Int. 2017;43:8269–8275. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.03.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowen P., Carry C. From powders to sintered pieces: Forming, transformations and sintering of nanostructured ceramic oxides. Powder Technol. 2002;128:248–255. doi: 10.1016/S0032-5910(02)00183-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng F., Liu C., Zhang F., Tian Z., Huang W. Densification and mechanical properties of fine-grained Al2O3–ZrO2 composites consolidated by spark plasma sintering. J. Alloy. Compd. 2012;512:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.09.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kong Y.M., Kim H.E., Kim H.W. Production of aluminum–zirconium oxide hybridized nanopowder and its nanocomposite. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2007;90:298–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2006.01353.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhuravlev V.D., Komolikov Y.I., Ermakova L.V. Correlations among sintering temperature, shrinkage, and open porosityof 3.5YSZ/Al2O3 composites. Ceram. Int. 2016;42:8005–8009. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.01.204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benaventea R., Salvadora M.D., Penaranda-Foix F.L., Pallone E., Borrell A. Mechanical properties and microstructural evolution of alumina–zirconia nanocomposites by microwave sintering. Ceram. Int. 2014;40:11291–11297. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.03.153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lange F.F. Transformation toughening Part 4: Fabrication, fracture toughness and strength of Al2O3-ZrO2 composites. J. Mater. Sci. 1982;17:247–254. doi: 10.1007/BF00809060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutierrez-Mora F., Singh D., Chen N., Goretta K.C., Routbort J.L., Majumdar S.H., Dominguez Rodriguez A. Fracture of composite alumina/yttria-stabilized zirconia joints. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2006;26:961–965. doi: 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2004.12.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang F., Li L.F., Wang E.Z. Effect of micro-alumina content on mechanical properties of Al2O3/3Y-TZPcomposites. Ceram. Int. 2015;41:12417–12425. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2015.06.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang D., Lim H.B., Lee K.J., Lee C.H., Cho W.S. Evaluation of mechanical reliability of zirconia- oughened alumina composites for dental implants. Ceram. Int. 2012;38:2429–2436. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2011.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu G., Xie Z., Wu Y. Fabrication and mechanical properties of homogeneous zirconia toughened alumina ceramics via cyclic solution infiltration and in situ precipitation. Mater. Des. 2011;32:3440–3447. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2011.01.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang D., Lim H., Lee K., Ha S., Kim K., Cho M., Park K., Cho W. Mechanical properties and high speed machining characteristics of Al2O3-based ceramics for dental implants. J. Ceram. Process. Res. 2013;14:610–615. [Google Scholar]

- 38.EN ISO 11885:2009-Water Quality. Determination of Selected Elements by Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) International Organisation for Standarization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rietveld H.M. A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1967;2:65–71. doi: 10.1107/S0021889869006558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young R.A., Sakthivel A., Moss T.S., Paiva-Santos C.O. DBWS-9411—An upgrade of the DBWS*.* programs for Rietveld refinement with PC and mainframe computers. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1995;28:366–367. doi: 10.1107/S0021889895002160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodrigez-Carvajal J. Fullprof, Program for Rietveld Refinement. Laboratories Leon Brillouin (CEA-CNRS); Saclay, France: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 42.ISO 22309:2011-Microbeam Analysis–Quantitative Analysis Using Energy-Dispersive Spectrometry (EDS) for Elements with An Atomic Number of 11 (Na) or Above. International Organisation for Standarization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.ISO 12154:2014-Determination of Density by Volumetric Displacement. Skeleton Density by Gas Pycnometry. International Organisation for Standarization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.ISO 9277:2010-Determination of the Specific Surface Area of Solids by Gas Adsorption—BET Method. International Organisation for Standarization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nanopowder XRD Processor Demo. [(accessed on 10 September 2017)]; Available online: http://science24.com/xrd/

- 46.Huang X., Chen Z., Gao T., Huang Q., Niu F., Qin L., Huang Y. Hydrogen Generation by Hydrolysis of an Al/Al2O3—Composite Powder After Heat Treatment. Energy Technol. 2013;1:751–756. doi: 10.1002/ente.201300129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang H., Li P., Cui W., Liu C., Wang S., Zhenga S., Zhanga Y. Synthesis of nanostructured γ-AlOOH and its accelerating behavior on the thermal decomposition of AP. RSC Adv. 2016;6:27235. doi: 10.1039/C5RA27838D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarkar D., Mohapatra D., Ray S., Bhattacharyya S., Adak S., Mitra N. Synthesis and characterization of sol–gel derived ZrO2. Ceram. Int. 2006;33:1275–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2006.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li M., Feng Z., Xiong G., Ying P., Xin Q., Li C. Phase transformation in the surface region of zirconia detected by UV Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. 2001;105:8107–8111. doi: 10.1021/jp010526l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Renuka L., Anantharaju K.S., Sharma S.C., Nagaswarupa H.P., Prashantha S.C., Nagabhushana H., Vidya Y.S. Hollow microspheres Mg-doped ZrO2 nanoparticles: Green assisted synthesis and applications in photocatalysis and photoluminescence. J. Alloy. Compd. 2016;672:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.02.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mao Y., Bai J., Zhang M., Zhao H., Sun G., Pan X., Zhang Z., Zhou J., Xie E. Interface/defect-tunable macro and micro photoluminescence behaviours of Trivalent europium ions in electrospun ZrO2/ZnO porous nanobelts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:9223–9231. doi: 10.1039/C7CP01101F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yobanny Reyes-López S., Saucedo Acuña R., López-Juárez R., Serrato Rodríguez J. Analysis of the phase transformation of aluminum formate Al(O2CH)3 to α-alumina by Raman and infrared spectroscopy. J. Ceram. Proc. Res. 2013;14:627–631. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Y., Cheng B., Wang K.-K., Ling G.-P., Cai J., Song C.-L., Han G.-R. Study of Raman spectra for γ-Al2O3 models by using first-principles method. Solid State Commun. 2014;178:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ssc.2013.09.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scheithauer M., Knozinger H., Vannicey M.A. Raman Spectra of La2O3 Dispersed on γ-Al2O3. J. Catal. 1998;178:701–705. doi: 10.1006/jcat.1998.2187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li P.G., Lei M., Tang W.H. Raman and photoluminescence properties of α-Al2O3 microcones with hierarchical and repetitive superstructure. Mater. Lett. 2010;64:161–163. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2009.10.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koltsov I., Przesniak-Welenc M., Wojnarowicz J., Rogowska R., Mizeracki J., Malysa M., Kimmel G. Thermal and physical properties of ZrO2–AlO(OH) nanopowders synthesised by microwave hydrothermal method. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017;131:2273–2284. doi: 10.1007/s10973-017-6780-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scoton A., Chinelatto A., Chinelatto A.L., Ojaimi C.L., Ferreira J.A., Jesus E.M., Pallone A. Effect of sintering curves on the microstructure of alumina–zirconia nanocomposites. Ceram. Int. 2014;40:14669–14676. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guimaraes F.A.T., Silva K.L., Trombini V., Pierri J.J., Rodrigues J.A., Tomasi R., Pallone E.M.J.A. Correlation between microstructure and mechanical properties of Al2O3/ZrO2 nanocomposites. Ceram. Int. 2009;35:741–745. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2008.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lamouri S., Hamidouche M., Bouaouadja N., Belhouchet H., Garnier V., Fantozzi G., Trelkat J.F. Controlof the γ-alumina to α-alumina phase transformation for an optimized alumina densification. Boletin Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 2017;48:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bsecv.2016.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Levin I., Brandon D. Metastable Alumina Polymorphs: Crystal Structures and Transition Sequences. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1998;81:1995–2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1151-2916.1998.tb02581.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee J., Jeon H., Oh D.G., Szanyi J., Kwak J.H. Morphology-dependent phase transformation of γ-Al2O3. Appl. Catal. A. 2015;500:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.apcata.2015.03.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou R.-S., Snyder R.L. Structures and Transformation Mechanisms of the η, γ and θ Transition Aluminas. Acta Cryst. 1991;47:617–630. doi: 10.1107/S0108768191002719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]