Abstract

Youth who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, and two-spirit (LGBTQ2S) are disproportionally represented in the foster care population and often face discrimination within the system. This article summarizes findings from focus groups with youth in care who are LGBTQ2S, foster caregivers, and child welfare workers to explore (a) the unique challenges and support-related needs of youth in care who are LGBTQ2S and their foster caregivers, and (b) strategies for building better relationships between these youth and caregivers. Findings can be used to improve youth placement stability.

There are more than 400,000 children in foster care in the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). While few empirical studies can offer precise data on the percentage of youth in care who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, and two-spirit (LGBTQ2S), experts agree that LGBTQ2S youth are disproportionately represented (Wilber, Ryan, & Marksamer, 2006; Wilson & Kastanis, 2015). Approximately 3–8% of youth in the United States identify as LGBTQ (Kann et al., 2016; Russell & Joyner, 2001; Savin-Williams, 2006). In contrast, studies of youth in care have found this percentage to be 15–19% (Courtney et al., 2005; Wilson & Kastanis, 2015). As part of a foster parenting program module development project, this article reports on some of the challenges and support-related needs of youth in foster care who are LGBTQ2S and their foster caregivers, and explores strategies for building better relationships between youth who are LGBTQ2S and their foster caregivers.

Challenges for LGBTQ2S Youth in Care

Youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S face a variety of challenges and unique vulnerabilities, both in care and beyond. Studies have found that youth who identify as LGBTQ2S are often placed in discriminatory or unprepared foster families and group homes, in the care of organizations intolerant of LGBTQ2S individuals, or in more highly restrictive placements than is necessary due to a lack of safe and affirming options. Moreover, youth who identify as LGBTQ2S are often served by social workers with no specialized training on how to effectively support these youth. Youth who identify as LGBTQ2S are sometimes forced into conversion therapy, and many, especially transgender teens, do not receive appropriate health care (Gilliam, 2004; Makadon et al., 2015; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015). Youth in foster care who identify as LGBTQ2S are at high risk for homelessness as the rejection and discrimination they often experienced in their biological homes (Ryan et al., 2009) is replicated in the child welfare system (Gilliam, 2004). In addition, research has found that youth in care who identify as LGBTQ receive fewer permanency options than foster youth who do not identify as LGBTQ, and are more likely to age out of care (Mallon, 2011).

Understanding the LGBTQ2S Youth–Caregiver Relationship

Many youth who identify as LGBTQ2S enter foster care for the same reason as non-LGBTQ2S youth: maltreatment. Although very little research has been conducted on two-spirit youth, research indicates that a high proportion of youth in out-of-home care who identify as LGBTQ end up there as a result of conflict around their sexual orientation or gender identity (Mallon, 2011; Wilber et al., 2006). Once in care, many youth who identify as LGBTQ2S continue to face the same hostility, rejection, and harassment that they experienced within their families of origin. For example, a 2001 survey of youth in out-of-home care in New York City who identified as LGBTQ found that 78% of these youth were removed or ran away from their foster care placements because of anti-LGBTQ violence or harassment (Woronoff et al., 2006). Even when placements are accepting of youth who identify as LGBTQ2S, they often lack the knowledge and training to provide adequate care and support. However, there is growing consensus about the importance of family acceptance and support in ensuring safety and well-being for youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S (Wilber et al., 2006; Woronoff et al., 2006).

The Connecting Program

Despite advancements in understanding the challenges and needs of youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S, there are no known evidence-based approaches to improving placement stability and social and emotional well-being of these young people. To begin addressing this, the authors developed a new program module focused on enhancing placement stability and well-being for youth identify as LGBTQ2S by building stronger relationships between these youth and their foster caregivers. This module was created as part of Connecting, a parenting program for foster caregivers. Connecting is a self-directed prevention program theoretically guided by the social development model (Hawkins et al., 2008). It is designed to promote healthy relationships between caregivers and foster teens (age 11–15) in their care, and prevent teen initiation of high-risk behaviors such as drug use, violence, and early sexual activity. Using the ADAPT-ITT framework (Wingood & DiClemente, 2008), Connecting was systematically tailored for child welfare using an evidence-based, universal parenting program called Staying Connected with Your Teen (Barkan et al., 2014). Using a combination of videos, guided discussion, and activities, the first two chapters focus on building and strengthening relationships between caregivers and teens in their care, while the next eight chapters cover a range of topics such as family communication, identifying and reducing risks, promoting teen involvement in family decision-making, and managing emotions. In addition, caregivers receive weekly support calls to encourage program completion, problem-solve, and celebrate progress. More detailed information on the Connecting program can be found in Barkan and colleagues (2014).

One shortcoming of the original Connecting curriculum is that it did not specifically address the unique challenges faced by youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S and their caregivers, including how to build stronger relationships. Thus, as part of a study funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, we conducted research to inform development of a new program module for Connecting that offers specialized relationship-building supports for foster families caring for youth who identify as LGBTQ2S.

This article summarizes the findings from focus groups with youth with foster care experience who identify as LGBTQ2S, foster caregivers, and child welfare workers to inform development of a new parenting program module, and in particular to explore two research questions: (a) what are the unique challenges or support-related needs for youth in foster care who identify as LGBTQ2S and their foster caregivers, and (b) what strategies do they recommend to build better relationships between youth who identify as LGBTQ2S and their foster caregivers?

Method

Participants

Twenty-eight participants were recruited for three focus groups: one each for child welfare staff (n = 13), foster caregivers (n = 9), and young adults with foster care experience who identify as LGBTQ2S (n = 6). Child welfare staff eligibility included being currently employed by the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) Children’s Administration (CA), with professional experience working with teens who identify as LGBTQ2S and their caregivers. Eligible caregivers were foster or relative caregivers with experience caring for teens involved in the child welfare system. Young adults were age 18 to 24, identified as LGBTQ2S, and were in the child welfare system during their teenage years. All participants were from a major metropolitan area in the Pacific Northwest. Participant demographics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| CA Staff (n = 13) |

Foster caregivers (n = 9) |

Young adults (n = 6) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Length of service | 9.7 (10.6) | 7.6 (8.7) | n/a |

| Race | % | % | % |

| White | 69% | 67% | 50% |

| Black/African American | 8% | 11% | 33% |

| Asian | 8% | 11% | 0% |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0% | 0% | 17% |

| Other (“Mixed”, “Very blended”) | 15% | 11% | 0% |

| Declined to respond | 8% | 11% | 17% |

| Hispanic ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic, Latino, Spanish origin | 8% | 11% | 0% |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 77% | 78% | 33% |

| Male | 23% | 22% | 33% |

| Transgender male | 0% | 0% | 17% |

| Transgender female | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Two-Spirit | 0% | 0% | 17% |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| 100% heterosexual | 100% | 78% | 0% |

| Mostly heterosexual | 8% | 11% | 17% |

| Bisexual | 0% | 11% | 33% |

| Mostly homosexual | 0% | 0% | 17% |

| 100% homosexual | 0% | 0% | 33% |

Note. Percentages may not add up to 100%, as participants were allowed to choose any and all categories that applied. CA = Washington State Children’s Administration

To recruit child welfare staff, we reached out to several offices with which we have had previous working relationships. CA staff and supervisors were invited to participate by telephone calls and emails from research staff. Caregivers were recruited through CA staff and caregiver-serving community organizations. Young adults were recruited through CA staff as well as organizations that serve foster care alumni, youth experiencing homelessness, and youth/young adults who identify as LGBTQ2S. Caregivers and young adults received $50 for their participation, as well as a stipend for childcare and transportation if needed. All study procedures were approved by the Washington State DSHS IRB.

Data Collection and Analysis

Focus groups took place in fall 2016. Each group contained 6 to 13 participants, and lasted 1.5 to 2 hours. Focus groups were conducted using a semi-structured protocol developed by the research team. At the beginning of the focus groups, participants were given a brief overview of Connecting and the goal of developing a new LGBTQ2S youth-specific module. Participants were then asked about challenges and support-related needs of youth who identify as LGBTQ2S and their foster caregivers; any strategies they may suggest for helping youth and foster caregivers build better relationships with each other; tips for helping caregivers and youth discuss sensitive topics such as sex or other risky behaviors; and strategies for intentionally addressing discrimination, safety, and acceptance. Focus groups were digitally audio recorded. The recordings were transcribed by a professional transcription company.

Transcript data were analyzed using conventional thematic content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) conducted in Dedoose qualitative data analysis software. One team of three researchers analyzed data for one research question while a different team of three researchers analyzed data to answer the second question. Four of these six researchers have either lived experience or direct practice experience working with youth in foster care or youth who identify as LGBTQ2S, and three have MSWs. Those without an MSW included a PhD research scientist, an undergraduate Human Development student, and a master’s-level research coordinator.

For each research question, team members independently coded the first transcript. This involved identifying key concepts that provided answers to the research questions and labeling them with initial codes. Teams then convened to resolve initial coding discrepancies, resulting in consensus-based coding results. The initial code list emerging from this process was then used to guide coding for the remaining two transcripts, although new initial codes could be added if no existing codes captured the concepts. Once all initial coding was complete and all discrepancies had been resolved, coding teams then collaboratively grouped initial codes into subthemes based on similar content. These subthemes were then grouped into larger themes that represented similar challenges or strategies conveyed in the subthemes. Content did not have to be present in all three participant groups to become a theme; however, all themes (and most, but not all subthemes) were in fact represented in all three participant groups. Thematic network maps were then created to summarize the findings. To assess the trustworthiness of the findings, they were emailed to all focus group participants with a request for feedback if the findings did not accurately reflect their experiences in the groups. Participants were given two weeks to provide feedback, but none was provided.

Results

Research Question 1: Unique Challenges and Supports

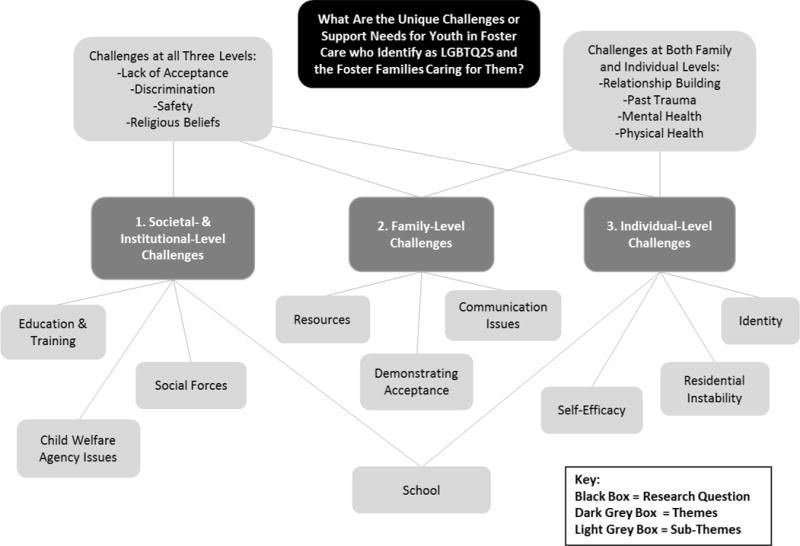

Participants were asked to identify challenges and supports that may be more unique to youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S and their caregivers compared to non-LGBTQ2S youth in care. Analyses revealed challenges and needs at three levels: the larger society, family, and individual. These three themes and their respective subthemes can be seen in the thematic network in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Thematic network for Research Question 1.

Societal and Institutional Challenges

Lack of LGBTQ2S acceptance from the larger society and the institutions that operate within it was a key identified challenge. One youth formerly in foster care said, “you have the entire outside world telling you that you should be converted out of your sexual orientation or your gender identity.” Youth who identify as LGBTQ2S may thus be reluctant to express their identities in a society that does not accept them. Stigma and discrimination are natural consequences of unaccepting attitudes and beliefs. A youth participant explained that, “[discrimination] could cause a lot of damage within the youth and fear within themselves and anger.” One child welfare worker pointed out that youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S “already are belonging to a system [foster care] that is sort of stigmatized in society,” so in effect are subject to discrimination based on both their sexual and/or gender identity as well as their foster care system involvement.

Safety concerns based on anti-LGBTQ2S discrimination was also a rich area of discussion. A former foster youth advised caregivers to, “think about the safety implications of having a kid that might get targeted for their identity.” Similarly, a child welfare worker explained the importance of “talking about safety. I mean bullying, other kinds of things that could come up where, you know, they need to know that you have their back and that just that safety [to] talk about places where they might not be safe.”

Child welfare agencies play a large role in ensuring the safety of youth in foster care who identify as LGBTQ2S. Although child welfare workers noted that caregivers are not allowed to discriminate against foster youth based on their LGBTQ2S identity, one worker explained how unaccepting religious beliefs among foster caregivers contribute to the challenges faced by youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S: “I have a certain percentage of my foster parents have always been faith-based and I think some of them will struggle mightily and maybe they just won’t take the youth that we’re talking about into their homes.” This may result in fewer safe and supportive placement options for youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S.

Family-Level Challenges

Youth who identify as LGBTQ2S face additional challenges at the family level. Rejection and fear of rejection are two such challenges. One caregiver stated, “I think that these youth may struggle with a lot of fear. They may not feel that they’re accepted in their own families, and therefore, they have a fear of expressing themselves as their own person.” For many youth, this fear has already become a reality as it contributed to their placement into care, and may continue to be distressing. A caregiver shared from her foster daughter’s experience, “Her dad would get upset with her over the phone. And she was kicked out of the house because of her gender. And so therefore, there was a lot of that—dealing with that—and not going home.” Some participants explained that youth who identify as LGBTQ2S who enter new foster homes may be afraid to connect with new caregivers due to fear of continued rejection. One youth shared, “Because, I guess, if the kid already feels like the world’s against them because, you know, their previous family rejected them because they were transgendered or they were gay. And they go to this house and they’re already expecting them to be like, ‘Oh, you’re gay? You need to leave…we don’t want you here.”

Communication challenges were also a salient subtheme. One youth formerly in foster care explained that foster parents may say unaccepting things like, “Well, you can be gay but not date anyone… Or you can be trans but not transition, just wait till you’re 18 and then do that.” All groups talked about communication breakdown and the challenges of talking about sensitive topics with youth or caregivers who may not be ready to discuss these issues. Caregivers also expressed concern about timing or when best to talk about issues of sexual identity and sexual behavior.

Individual-Level Challenges

Like many other elements of one’s identity, sexual orientation and gender identity are sometimes fluid during adolescence. Like youth not in care, youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S must navigate a personal journey of identity development and self-discovery, particularly in relation to their sexual and gender identity. As one caregiver explained, “…often times, somebody fits into one of these categories, because they’re on a progression of self-discovery, and they might start out identifying as bisexual, and then end up identifying as heterosexual, and then, potentially become trans.” Recognizing and adapting to uncertainty and changes in identity is a challenge for the teen as well as those around them. Another individual-level challenge involves the negative effects resulting from family and societal rejection. Participants connected this rejection to individual experiences of trauma and mental health issues, especially depression and anxiety. As an example, a child welfare worker explained, “…the child is at risk if they are constantly being mis-gendered and that’s exacerbating their depression.”

When asked specifically about youth who identify as transgender, individual challenges around receiving appropriate information and medical care were discussed. One youth formerly in foster care said, “For me it’s less of an identity than it is a health condition, like something I go to the doctor for.” Caregivers and child welfare staff emphasized the importance of finding the right doctor and making sure youth have complete and accurate information about their medical options.

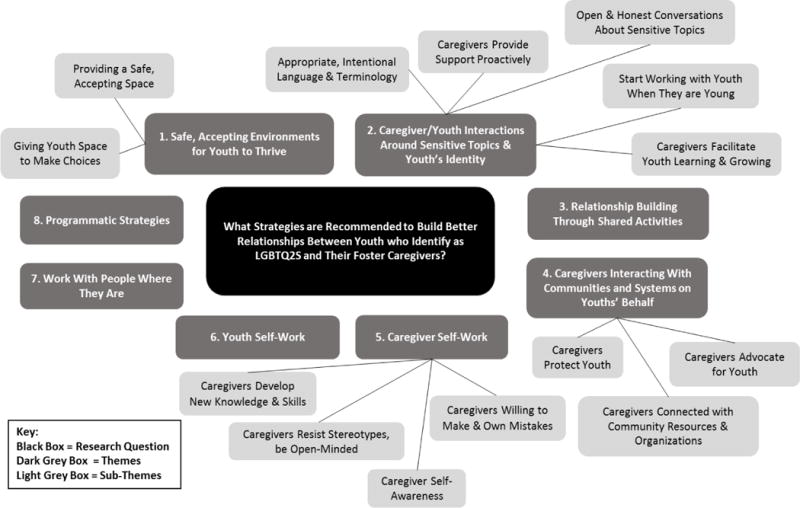

Research Question 2: Relationship-Building Strategies

Analyses for this research question resulted in eight themes, which are represented in Figure 2: (1) safe and accepting spaces, (2) caregiver/youth interactions, (3) shared activities, (4) caregivers acting on youths’ behalf, (5) caregiver self-work, (6) youth self-work, (7) working with people where they are, and (8) programmatic strategies.

Figure 2.

Thematic network for Research Question 2.

Safe, Accepting Spaces

Many participants discussed the importance of caregivers creating a safe, accepting environment for youth in their care in their efforts to build trusting relationships. As one youth explained, “not everywhere outside that house is gonna be safe for them… So a lot of them just need that support and that knowledge that when they come home they are – they’re okay and they’re gonna be safe and accepted.” Participants shared several suggestions for and examples of creating this safe place; one caregiver participant said, “So, one of the things we found very early, is he really likes having rainbow flags, so we’ve got rainbows through parts of the house, and [he] wants to have them near the front door, so other people know we’re a safe place.” Another caregiver described how they created an accepting environment by learning about the youth’s hobbies and interests and getting involved. Additional recommendations for creating safe, accepting spaces focused on giving youth freedom to make their own choices; “…even simple things like letting the youth in their care choose how they dress and how they wear makeup or hair or whatever… it’s a simple way to say, ‘I’m accepting of your identity and we’re going to let you express that in this house and out in the community.’”

Caregiver/Youth Interactions

All participant groups agreed that the nature of caregiver-youth interactions has a critical impact on relationship building. A wide variety of strategies for improving the quality of these interactions were discussed, including caregivers being willing to have open and honest conversations about sensitive topics such as sex or the youth’s engagement in risk behaviors; starting these conversations at an early age; providing proactive support to youth; facilitating youth learning and growing; and using appropriate, intentional language and terminology. As one young adult described, “Don’t be afraid to just go up to them and be like, ‘Hey, what should I know?…’ Just show that… you’re willing to work with them and know about them.”

Participants recognized that conversations about sensitive topics can be difficult to have; however, many emphasized the importance of having them anyway. One worker explained, “I really talk to caregivers about needing to model that it’s okay to have difficult conversations and to acknowledge that [you] don’t always have the right words… but I want you to know that we can talk… We don’t need to have all the answers, but this is a safe place.” Participants recommended that caregivers be proactive about having these conversations with youth, and that these conversations happen early and often.

Participants offered a number of concrete strategies for improving caregiver/youth interactions. These included listening to youths’ stories, sharing personal experiences, and letting youth lead conversations. In addition, participants strongly emphasized the importance of using appropriate and intentional language and the correct terminology, including the pronouns youth use to describe their gender. One caregiver shared, “It was hard at first to switch [pronouns], and I saw how hurtful it was, and just really made a push. Instead of trying to remember ‘she,’ I would use her name—her first name—and then the ‘she’ came naturally, later.” These interaction strategies can help create a safe environment within which the youth-caregiver relationship may be more likely to succeed.

Relationship-Building through Shared Activities

Participating in activities together is one way participants from all three groups recommended caregivers and youth build healthy relationships, including activities that support youths’ LGBTQ2S identity as well as those that increase bonding in a more fundamental sense. Participants suggested activities such as attending LGBTQ2S parades or organization meetings, or watching documentaries together about LGBTQ2S-related topics. One child welfare worker shared, “Sometimes, [caregivers] need to be helped with building [a] relationship with their youth. So I feel like some activities that require them to really talk to each other or just like working on a puzzle, something really simple.” By engaging in activities that allow caregivers and youth to work together to build fundamental relationship skills, participants felt they would be better equipped to engage in more sensitive discussions.

Caregivers Interacting with Communities and Systems on Youths’ Behalf

Study participants also recommended ways for caregivers to act as a supportive interface between youth and the larger society as part of their relationship-building work with youth. One child welfare worker described how helpful it can be for caregivers to be knowledgeable of LGBTQ2S-focused community resources and get involved in local events: “There’s things going on all the time. So I think either going with the youth or maybe encouraging them to attend or just, you know, using those resources I think and educating the foster parents about what’s available out there.” Other participants discussed specific community resources they had found helpful in supporting teens, such as summer camps for youth who identify as LGBTQ2S, books written for teens, support groups, and transgender-knowledgeable healthcare services. Participants also discussed how caregivers connecting with adults in the community who identify as LGBTQ2S can be beneficial to both caregivers and teens.

The importance of caregivers being willing to advocate for youth was also frequently discussed. Participants described the need for caregivers to advocate for the youth in their care in a variety of ways, such as talking to the school to ensure their safety; working with the social worker to ensure the youth is receiving appropriate and competent physical and mental health care; and learning the legal processes involved with gender transitions such as name changes, among others. The importance of protecting youth from discrimination and harm often overlapped with the responsibilities of advocating and creating an accepting environment. One caregiver captured these complementary goals: “So, making sure they know that you’re there, no matter what. That you accept them, no matter what they decide, and that they don’t have to decide today what that is; but whatever they’re thinking that day is A-Okay. And that I will go to the school, and if anybody’s harassing them, I will deal with it. If their social worker is understanding, I’ll go there. I’ll talk to the counselor; I’ll talk to the attorney; whatever they need. So that they know that they’ve got somebody at their back.”

Caregiver Self-Work

Another theme was caregiver self-work, or ways that caregivers may need to improve their ability to effectively support and connect with youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S. Participants emphasized many types of knowledge and skills that would help caregivers, such as learning about the obstacles that these youth often face; gender and sexual identity; trauma and how it impacts health and behavior; the LGBTQ2S community; LGBTQ2S history; appropriate language (labels, pronouns); how to talk with school staff about their teen’s needs; and how to find LGBTQ2S-empowering community organizations and activities. One young adult gave this advice to caregivers: “…[don’t] be afraid to look up stuff about the community and stuff like that….don’t fly into it blind.”

Two subthemes emerged from the data within the caregiver self-work theme: caregiver resisting stereotypes/remaining open minded and building caregiver awareness. One caregiver, for example, mentioned that youth who identify as LGBTQ2S may still be developing and should not be defined by their gender: “I think it’s important…to be non-judgmental. And it’s really important also not to associate a gender with certain behaviors. That the emphasis on positive types of actions and behaviors, as a human being, is what is important for the youth to develop into…” Building caregiver self-awareness was a related subtheme; one child welfare worker’s recommendation suggested the importance of self-awareness as complementary to open mindedness: “And just keep an open mind, keep updating your language, and keep checking in and keep checking yourself.” Participants also emphasized the importance of caregivers being willing to make and to own their mistakes. This is where caregivers show their vulnerability and willingness to learn to the youth in their care, as expressed by one caregiver: “I think for her, me, showing that I didn’t have all the answers, but that I was willing to explore them with her, was helpful to her.”

Youth Self-Work

Participants expressed that the responsibility of building caregiver-youth connections was not solely on caregivers, but on youth as well. Some recommendations focused on the importance of youth being patient with caregivers and understanding that people sometimes make mistakes. One youth described, “I think intentions go a long way. I know I haven’t had my pronouns mixed up in a long time but when they were, it’s like as long as the person is coming from a good place and they’re not doing it meanly, it’s so much easier to just be like, ‘It’s okay, just get it right next time.’” Another youth participant noted that youth “…need to understand that their caregiver might have questions” due to a lack of knowledge. Other caregivers may not yet be ready to talk about LGBTQ2S-related topics; as on youth participant explained, “You have to kinda be cautious how you approach topics like those. And start with, I guess, opening up, expressing that you would like them to attend [the pride parade] with you…and I guess try to understand if they’re like, ‘No, I’m not ready to do that type of stuff with you.” Recommendations were also made regarding the importance of youth being respectful to their caregivers just as they expect their caregivers to be to them. So, ensuring that learning, respect, and understanding are shared values observed by youth and caregivers was important.

Working with People Where They Are

Another theme was the importance of accepting that not everyone may be ready or willing to actively accept and build skills around supporting youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S, and developing strategies to support growth and progress. While reviewing example curriculum elements, a child welfare worker described this challenge: “Where it says [in the curriculum], ‘I just want you to know that you’re good with me, that I’m here for you.’ Like they might not be ready to say that so like what kind of neutral language could they use to validate what the youth is saying while they are still trying to process how they are going to deal with it themselves.” Another recommendation involved acknowledging small steps toward a caregiver developing acceptance. One youth respondent shared a personal experience to illustrate this: “I remember my bio-mom would never say the word [gay]… And she drove me to a pink prom once and she wouldn’t ask what it was and she wouldn’t acknowledge that it was a gay thing or whatever but she dropped me off… And that was like the tipping point. And then I think a few years ago she went to the pride parade… But I think like a little tiny, even just like a baby step is like, that made my month probably, I don’t know. It’s like a little goes a long way.”

Programmatic Strategies

Finally, study participants made a variety of recommendations for how to structure a caregiver–youth support program. These included suggestions such as facilitating activities that involve both caregivers and youth as well as youth- and caregiver-only activities; using icebreaker activities to aid in relationship building; training caregivers on how to create accepting environments; offering interactive activities to train foster caregivers; and providing follow-up meetings and check-ins from program staff. One child welfare staff person explained the importance of check-ins with families: “I think [a program like this] may [be] difficult if they are not done in a facilitated way. Like just being done by the caregiver and the teen on their own, I think that they may struggle with really getting to the heart of what these activities are trying to get to.”

Discussion

This study’s findings include a wide variety of considerations for programs aiming to better support the relationships between youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S and their caregivers. This study supports previous research findings regarding many of the challenges that youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S face, such as continued discrimination, lack of safe spaces, and other circumstances that make placement difficult (e.g., Gilliam, 2004; Mallon, 2011). In addition, this study builds on and expands current knowledge by both identifying various systems (society/system/community, family, individual) with which to intervene, as well as a wide variety of specific relationship-building strategies that map onto these different systems.

One notable finding regarding relationship building strategies was that, while one theme (Working with People Where They Are) reflected the reality that some people may not be ready to engage in fully accepting, supportive behaviors, the remaining themes assume and/or hinge on acceptance or an openness to acceptance already being in place. While it makes sense that, to build stronger relationships, a foundation of acceptance must almost certainly be in place, this foundation may or may not be a reality for many caregivers in this situation. Strategies for supporting caregivers in developing acceptance are also needed. One intervention approach, the Family Acceptance Project, aims to do just that. It has been used in a wide variety of contexts, including child welfare, and works with families to move to a place of acceptance with their children who identify as LGBTQ2S (Ryan et al., 2010). Having a continuum of strategies that range from building a foundation for acceptance all the way to putting this acceptance to use to support meaningful relationship building can help improve a wide variety of placement situations for youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S.

Furthermore, the majority of caregiver and staff participants identified as heterosexual and/or cisgender. It is important to consider the ways in which participants’ identities impact their understanding of these youths’ identities. Limited knowledge and personal biases about youth in foster care who identify as LGBTQ2S may pose barriers to developing accepting relationships among staff, caregivers, and youth in their care. However, because it is not always possible to place youth who identify as LGBTQ2S with caregivers who identify similarly, the problem that must be addressed is building this acceptance and support of youth who identify as LGBTQ2S in all caregivers. Thus, it may be that some of the most powerful recommendations for improving acceptance and support for youth in care who are LGBTQ2S through relationship building may in fact come from caregivers and child welfare workers who have had to grapple with this due to their lack of lived experience.

Implications

This study uses the voices of practitioners, caregivers, and youth with foster care experience to support important elements of what we know is critical for youth in foster care who identify as LGBTQ2S, primarily acceptance, support, and ensuring safety (Wilber et al., 2006; Woronoff et al., 2006). We have used our findings to inform the development of a module to guide caregivers in how to care for and support teens in their identity development. Moreover, these voices support other scholarship and research and can be used to better support youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S and their caregivers, particularly through interventions aimed at improving placement stability, and potentially permanency, for these youth. Programs designed to strengthen accepting relationships between youth in care who identify as LGBTQ2S and their caregivers hold great promise because they better position caregivers to help these youth navigate the other complex systems and social situations they face. In addition, some of the key components needed for programs to better respond to the needs of youth who identify as LGBTQ2S and their caregivers delineated in this article may also provide critically important guidance for broader program development and systemic responses for this population. For example, several of the recommendations, particularly those captured in themes one through five, could be addressed through enhanced foster parent trainings. Working with stakeholders where they are at, however, may be a more appropriate training topic for child welfare workers. Finally, youth self-work could be addressed in a variety of ways, such as through youths’ interactions with their case workers, court appointed special advocates, independent living skills providers, or other support staff members.

Limitations

The primary study limitation is that participants were all from one Pacific Northwestern metropolitan area that tends to be more progressive than other cities regarding LGBTQ2S acceptance and advocacy. Different themes may have emerged with a more nationally representative sample, or from communities that tend toward lower acceptance. Furthermore, only one focus group was conducted with each of the three participant groups; additional groups and a large sample of study participants may have resulted in different findings. Furthermore, the small sample size meant that only a small number of those representing particular sexual orientation, gender identities, races, or ethnicities were included (for example, there was only one participant who identified as transgender). Finally, the roles of race and ethnicity and how these relate to the barriers and support recommendations for youth who identify as LGBTQ2S and their caregivers were not thoroughly discussed in the focus groups, so we were unable to explore key issues related to intersectionality.

Conclusion

The child welfare system serves to protect children from maltreatment and unsafe families and homes. This should be true for all youth in care. We found that acceptance, support, and ensuring safety are important elements to include in programming aiming to improve placement stability and well-being through relationship building. The discrimination and rejection that some youth who identify as LGBTQ2S face in their families of origin should not be replicated in the system meant to keep them safe. Instead, strategies for better building relationships between foster caregivers and youth in their care who identify as LGBTQ2S can help make the child welfare system work better for all children and youth.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant #3R01DA038095-02S1). The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency. The National Institute on Drug Abuse played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Contributor Information

Amy M. Salazar, Washington State University Vancouver

Kristin J. McCowan, University of Washington

Janice J. Cole, University of Washington

Martie L. Skinner, University of Washington

Bailey R. Noell, Washington State University Vancouver

Jessica M. Colito, University of Washington

Kevin P. Haggerty, University of Washington

Susan E. Barkan, University of Washington

References

- Barkan SE, Salazar AM, Estep K, Mattos LM, Eichenlaub C, Haggerty KP. Adapting an evidence based parenting program for child welfare involved teens and their caregivers. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;41:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Dworsky A, Cusick GR, Keller T, Havlicek J, Bost N. Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth: Outcomes at age 19. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam JW., Jr Toward providing a welcoming home for all: Enacting a new approach to address the longstanding problems lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth face in the foster care system. Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review. 2004;37:1037–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Arthur MW, Egan E, Brown EC, Abbott RD, Murray DM. Testing Communities That Care: The rationale, design and behavioral baseline equivalence of the Community Youth Development Study. Prevention Science. 2008;9:178–190. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0092-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, O’Malley Olsen E, McManus T, Harris W, Shanklin S, Zaza S. Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Related Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9-12 – United States and Selected Sites, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Surveillance Summaries. 2016;65(9):1–81. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makadon H, Mayer K, Potter J, Goldhammer H. The Fenway Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health. 2. Philadephia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mallon GP. Permanency for LGBTQ youth. Protecting Children, A Professional Publication of American Humane Association. 2011;26:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Joyner K. Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: Evidence from a national study. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1276–1281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, Sanchez J. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;23:205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams Who’s gay? Does it matter? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Ending Conversion Therapy: Supporting and Affirming LGBTQ Youth. Rockville, MD: Author; 2015. Retrieved from https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA15-4928/SMA15-4928.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. The AFCARS Report: Preliminary FY 2015 estimates as of July 2016 No 23. Washington, DC: Author; 2016. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport23.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wilber S, Ryan C, Marksamer J. CWLA best practice guidelines: Serving LGBT youth in out-of-home care. Washington, DC: Child Welfare League of America; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BDM, Kastanis AA. Sexual and gender minority disproportionality and disparities in child welfare: A population-based study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2015;58:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The ADAPT-ITT model: A novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;47(Suppl 1):S40–S46. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woronoff R, Estrada R, Sommer S. Out of the margins: A report on regional listening forums highlighting the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth in care. Washington, DC: Child Welfare League of America and Lambda Legal Defense & Education Fund; 2006. [Google Scholar]